Climate Change

The Environment’s Role in Promoting Infectious Disease

Dear Reader,

Welcome, or welcome back, to our infectiously page-turning magazine! We are beyond proud to present the first release in our second volume of the Infectious Disease Society (IDS) Magazine. Started as a passion project to contribute to Brown’s scientific writing community with a publication centered entirely around communicable diseases and their corresponding societal structures, we are truly proud of our publication’s continued growth under the unwavering passion and academic curiosity of our team.

As we reflect on the impact we want our magazine to leave on the scientific community of Brown, we would like to hone in on the holistic dimensions of health and disease, drawing and analyzing often overlooked connections. That being said, we present to you “Climate Change: The Environment’s Role in Promoting Infectious Disease”, an issue dedicated to augmenting the ongoing dialogue of the dimensions of climate change and its effects on our society. We invite you on a journey as you immerse yourself in the pages of this magazine, asking yourself a plethora of questions to fully capture the magnitude of climate change and its tight grasp on broader global health outcomes.

With the presentation of our third issue overall, we would like to give thanks to everyone that has made this possible. As such, we want to begin by acknowledging the hard work of the IDS Magazine team–our writers, editors, design editors, and

communications team–who collectively worked together to make the production of this magazine feasible. This magazine would also not be possible without the help of the IDS Executive Board and larger IDS community. We would like to conclude with the hope that this magazine will serve to not only promote discussion, but build a community of individuals passionate about infectious diseases beyond its current and future pages.

With kind regards,

Sean Park and Alvaro Uribe Editors-in-Chief

Writer

Kiara Anderson Lead Design Editor

Jacqueline Larson Design Editor

Evan Li Design Editor

Natalie Tse Design Editor

Shrey Mehta Lead Communications Chair

Lilia Felipe Pozo Communications Chair

Annie Song Communications Chair

Not Pictured: Ruviha Homma (Editor) Kevin Pham (Editor)

16

Nelsa Tiemtoré

Integrating Climate Change Education Into Clinical Practice

12

Evan Li

20

Joanna Renedo 24

El Niño and the Rise of Infectious Diseases in Latin America

Telehealth: A Cure for Climate Change?

18

Esther Liu

Rishi Rai

Climate Change and Waterborne Diseases: The Global Impact on Health and Water Security

Climate Change and AMR

Nelsa Tiemtoré

Health Outcomes

Climate Change placement

22

Emily Mrakovcic

Climate Change and Coral Reefs: Increasing Incidence of Disease and Its Subsequent Effects

28

Ávaro

Shifting icies

Middle of

Outcomes of Change Dis-

Layers of Crisis: Climate Change, Health, National Security in Sudan

Esther Liu 38 Disasters and Disparities: How Natural Hazards Worsen Health Inequities

Julia Rodriguez 28

Ávaro Amir Uribe 36

Shifting Ground: Policies and Poetry for a Middle East in the Age Climate Change

Rishi Rai 42 More Than Just an Itch: Climate Change’s Role in Vector Borne Disease

An Active Syndemic: Climate Change, Environmental Injustice, and Structural Racism

Joanna Renedo 40 Climate Change’s Toll: Escalating Effects of Natural Disasters and Infectious Diseases in the Global South Emily Mrakovcic

“Learning about the connection between climate change and disease behavior can help guide diagnoses, treatment and prevention of infectious diseases.”

–George R. Thompson, UC Davis School of Medicine

“Perhaps this is not surprising – many human viruses also cycle seasonally and are associated with particular weather patterns. However, the observed correlations between weather and COVID-19 suggest that the virus might be more susceptible to weather and seasonality than other viruses.”

–Mark C. Urban, Director of the Center of Biological Risk, Professor of Ecology & Evolutionary Biology, University of Connecticut

Written By:

Nelsa Tiemtoré

Moretti (2021) poses an important question: “How can we respond to climate change as frontline providers, as health experts within our communities, if we are never trained in the topic?” With the health impacts of climate change increasing globally, many institutions of higher learning are expanding their curriculums to now include climate change education, in the hopes of better equipping healthcare professionals. In addition to higher education taking this leap of faith, many global health organizations such as the Global Health Security Agenda, the World Health Organization and the Global Consortium on Climate and Health Education are doing the same.

context of the coronavirus pandemic where air-pollution affected the disease’s mortality rates and disproportionately affected communities of color.

By having a deep rooted understanding of how environmental factors affect the human body, healthcare professionals can better identify root causes of illness, locate at-risk populations, and improve treatment options, resulting in improved patient care and greater prevention of disease. Educating healthcare professionals on climate education enables them to promote

of climate change education into the medical setting. Dr. Gaurab Basu, a primary care physician affiliated with the school and the current Director of Education and Policy at the Center for Climate, Health, and the Global Environment (C-CHANGE), reiterates why this is necessary by saying that,

“Learning about climate change in medical school shouldn’t be an afterthought; it’s fundamental to the practice of being a good doctor. If we make it standard to understand how diseases are changing because of climate change, we’ll be better prepared to diagnose our patients and provide appropriate treatment plans” (Salata Institute for Climate and Sustainability, 2024).

“By having a deep rooted understanding of how environmental factors affect the human body, healthcare professionals can better identify root causes of illness, locate at-risk populations, and improve treatment options, resulting in improved patient care and greater prevention of disease.”

Climate change education, though not traditionally integrated into healthcare settings, holds immense value. The effects of climate change alone have resulted in the increased prevalence of renal disease, cardiac disease, pulmonary disease, and poor birth outcomes (Moretti, 2021). These effects were especially notable in the

more sustainable behaviors for patients and increased patient awareness about the correlation between environmental factors and their health. Furthermore, understanding the environmental causes of health issues can significantly decrease healthcare costs due to earlier detection. These changes would also lead to an increase in the number of climate-resilient healthcare facilities built. Such facilities would be well equipped to support communities disproportionately affected by climate change and its health outcomes.

Harvard Medical School (HMS) sets the standard for the implementation

At HMS, climate change and planetary health are now optional concentrations that address the health outcomes of climate change within the 4 year curriculum. As the training and education of healthcare professionals continues to evolve , the inclusion of climate change education is poised to become an essential part of medical curricula. as its benefits become more widely recognized!

Edited By:

Kevin Pham

Moretti, K. (2021). “An education imperative: Integrating climate change into the emergency medicine curriculum”. “AEM Education and Training, 5”(3), e10546. https://doi.org/10.1002/aet2.10546

Salata Institute for Climate and Sustainability. (2024, May 29). “Bringing climate change into medical school”. Harvard University. https://salatainstitute. harvard.edu/bringing-climate-change-into-medical-school/

Source: Adobe Stock https://stock.adobe.com/search/images?filters%5Bcontent_type%3Aphoto%5D=1&filters%5Bcontent_type%3Aillustration%5D=0&filters%5Bcontent_type%3Azip_vector%5D=0&filters%5Bcontent_type%3Avideo%5D=0&filters%5Bcontent_type%3Atemplate%5D=0&filters%5Bcontent_ type%3A3d%5D=0&filters%5Bcontent_type%3Aaudio%5D=0&filters%5Bfetch_excluded_assets%5D=1&filters%5Binclude_stock_enterprise%5D=1&filters%5Bis_editorial%5D=0&filters%5Bcontent_type%3Aimage%5D=1&k=climate+change&order=relevance&limit=100&search_page=1&search_type=pagination&get_facets=0&asset_id=244938060

Written By:

Evan Li

First used by NASA to remotely track astronauts’ health during space missions, telehealth, the use of communication technology to deliver “general health services from a distance,” proved itself to be a vital tool for healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic (Hyder and Razzak 2020). By allowing doctors and nurses to remotely monitor a patient’s health condition at a safe distance, telehealth technology protected hospital personnel from COVID-19 exposures. Before the pandemic, telehealth had been a promising though rarely-used technology: its usefulness stymied by complex logistics and “inconsistent and often inadequate reimbursement for services” (Hyder and Razzak 2020). However, its necessity in responding to the pandemic spurred hospitals to integrate telehealth into their infrastructure, allowing for greater preparedness for future pandemics and more efficient patient processing in general.

healthcare system, the very safeguard of human wellbeing, contributes substantially to the issue - releasing 4% of global carbon emissions, which exceeds that of the aviation and shipping industry (Metzke 2022). Travel, both of patients and doctors, accounts for a significant portion (around 17%) of the healthcare industry’s pollution (Andrews et al. 2013). Telehealth presents a straight-forward solution.

In a 2023 study of the Stanford Healthcare Center, researchers found that a higher use of telehealth-facilitated checkups in place of traditional in-person visits considerably reduced carbon emissions (Thiel et al. 2023). While the increased use of electricity released around 29,000 kg CO2e,

(Thiel et al. 2023).

“Though telehealth technology presents a novel way to reduce the healthcare system’s carbon footprint, its benefits are diminished by patient satisfaction and clashing regulations.”

The increasing frequency of pandemics though is only a symptom of a larger, more terrifying disease: climate change. Deforestation only increases the probability of the spread of a new zoonotic disease, and as pollutants metastasize to the air, water, and land, the rates and acuity of respiratory illness, cardiovascular disease, and cancer worsen (Metzke 2022). Ironically, the

when compared to the 136,800,000 km of travel it saved, telehealth technology diminished greenhouse gas emissions by 17,000 metric tons, “equivalent [to] over 2,100 homes energy use for a year or the CO2 sequestered by nearly 20,000 acres of US forest in one year” (Thiel et al. 2023). Considering how inextricably tied ecological health is to that of humans, telehealth protects not only the environment, but also “positively benefits chronic health outcomes that are affected by pollution, such as COPD [chronic obstructive pulmonary disease] and cardiovascular health”

However, often, the virtual-in-person tradeoff is not so clean. Patients dissatisfied with telehealth care or simply desiring the more thorough examination provided by in-person treatment may choose to switch over, diminishing its environmental benefits. Indeed a recent study found that 46% of orthopedic patients converted to in-patient appointments after initially being treated through telehealth means (Ahmad et al. 2023). Additionally, while a meta-study of 53 papers of patient satisfaction with telehealth treatment concluded that patients were by and large satisfied with their care, patient satisfaction is often lower than that of in-person treatments (Pogorzelska and Chlabicz 2022). Lower patient satisfaction can be largely explained away by telehealth’s relatively new emergence, nothing more than Luddite distrust that will be wiped away ast telehealth becomes normalized. However, telehealth’s universal inclusion into the healthcare system also proves difficult.

While state and federal regulations of telehealth were relaxed during the COVID-19 pandemic, they may stymie telehealth’s widespread and permanent integration. The fact that telehealth can provide care across state lines makes it difficult for “patients [to] [know] what services are covered, and for providers [to] [know] what regulations to abide by” (Weigel et al. 2020). While the government regulates the coverage of telehealth by Medicare and self-insured healthcare plans, Medicaid and employer-sponsored health-

care must abide by both federal and state regulations (Weigel et al. 2020). Thus patients must not only navigate the oft-contradicting policies between federal and state governments, but also the differing policies of different states. For example, if a doctor wishes to treat a patient in a different state through telehealth, some states require they receive a special-license (Holman 19) while other states participate in “compacts” where doctors in participating states can receive an expedited process to practice (Weigel et al. 2020).. Regulatory mismatch makes it difficult for both patients and providers to use telehealth care. Unable to contend with the differing regulations, especially when it comes to care across state lines, patients may simply choose in-person treatment, stymying telehealth’s environmental benefits.

Though telehealth technology presents a novel way to reduce the healthcare system’s carbon footprint, its benefits are diminished by patient satisfaction and clashing regulations. Even past those challenges, telehealth’s reliance on electricity would make it impossible to “achieve the zero-emissions status required to ameliorate the worst of climate change” (Thiel et al. 2023). Structural changes, like the decarbonization of the electric, are necessary for it to be truly effective (Thiel et al. 2023). Without such overhauls, telehealth is a multivitamin to climate change’s cancer. It may not help much, but one still ought to take it.

Edited By:

Lai

World Health Organization. (2011). Report on the burden of endemic health care-associated infection worldwide. https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/80135/9789241501507_eng.pdf?sequence=1

Haque, M., Sartelli, M., McKimm, J., & Abu Bakar, M. (2018). Health care-associated infections – an overview. Infection and Drug Resistance, 11, 2321–2333. https://doi.org/10.2147/IDR.S177247

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2021, November 10). Healthcare-associated infections. https:// www.cdc.gov/hai/index.html

Lukas, S., Hogan, U., Muhirwa, V., Davis, C., Nyiligira, J., Ogbuagu, O., & Wong, R. (2016). Establishment of a hospital-acquired infection surveillance system in a teaching hospital in Rwanda. International Journal of Infection Control, 12(3). https://doi.org/10.3396/ijic. v12i3.16200

Vilar-Compte, D., Camacho-Ortiz, A., & Ponce-deLeón, S. (2017). Infection control in limited resources countries: challenges and priorities. Current Infectious Disease Reports, 19. https://doi.org/10.1007/ s11908-017-0572-y

Maki, G., & Zervos, M. (2021). Health care–acquired infections in low- and middle-income countries and the role of infection prevention and control. Infectious Disease Clinics of North America, 35(3), 827–839. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.idc.2021.04.014

Rosenthal, V. D., Maki, D. G., Rodrigues, C., Álvarez-Moreno, C., Leblebicioglu, H., Sobreyra-Oropeza, M., Berba, R., Madani, N., Medeiros, E. A., Cuéllar, L. E., Mitrev, Z., Dueñas, L., Guanche-Garcell, H., Mapp, T., Kanj, S. S., & Fernández-Hidalgo, R. (2010). Impact of International Nosocomial Infection Control Consortium (INICC) strategy on central line–associated bloodstream infection rates in the intensive care units of 15 developing countries. Infection Control and Hospital Epidemiology, 31(12), 1264–1272. https://doi. org/10.1086/657140

Source: Adobe Stock https://stock.adobe.com/search/images?filters%5Bcontent_type%3Aphoto%5D=1&filters%5Bcontent_type%3Aillustration%5D=0&filters%5Bcontent_type%3Azip_vector%5D=0&filters%5Bcontent_type%3Avideo%5D=0&filters%5Bcontent_type%3Atemplate%5D=0&filters%5Bcontent_type%3A3d%5D=0&filters%5Bcontent_type%3Aaudio%5D=0&filters%5Bfetch_excluded_assets%5D=1&filters%5Binclude_stock_enterprise%5D=1&filters%5Bis_editorial%5D=0&filters%5Bcontent_type%3Aimage%5D=1&k=telehealth&order=relevance&limit=100&search_page=1&search_type=usertyped&acp=&aco=telehealth&get_facets=0&asset_id=335048440

Written By:

Joanna Renedo

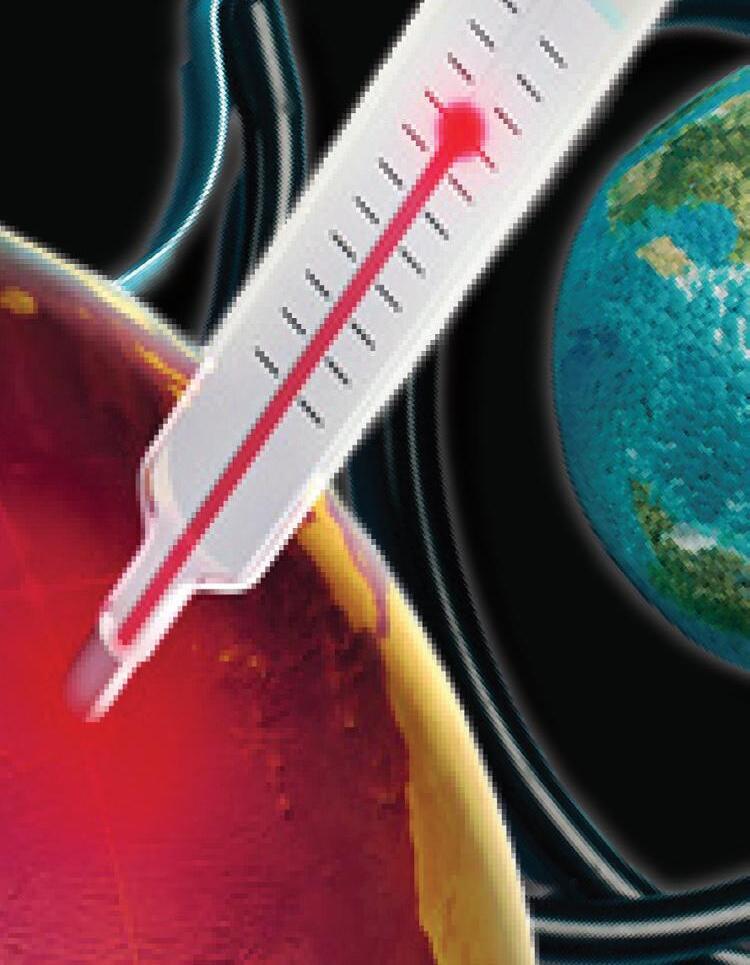

ver half of known human pathogenic diseases can be aggravated by climate change”, (Nature Climate Change, 2022). Climate change is an issue getting worse by the second and only recently has it been gaining attention for its health impact. There’s currently research uncovering the effects of climate change on our health showing increased respiratory illnesses and social determinants of health. On top of these, climate change has been shown to worsen infectious diseases such as those transmitted from mosquitoes. Diseases such as zika, dengue fever, and malaria have been a surging issue in Latin America due to climate change and have only worsened when weather events such as El Niño begin their cyclical journey.

Central America that usually cause flooding. La Nina is the opposite of El Niño and brings cold water to the Americas causing heavy rainfall in Canada and the northern US but drought in Mexico, South and Central America and southern US (National Ocean Service, 2024).

El Niño is particularly disastrous when it comes to infectious diseases as it lengthens the window of rainfall and flooding that countries in Latin America experience. El Niño has been attributed to one of the factors of the dengue epidemic in Latin America which was previously eradicated. Between 1952 and 1965, 19 Latin American countries had eradicated the dengue virus but by in 2007 it had re-infested endemic areas (Tapia-Conyer et al., 2009). Apart from dengue, other infectious diseases have arisen

ground for mosquitoes and other disease-carrying vectors that cause outbreaks. With the heavy rainfall it produces, stagnant bodies of water form which help mosquitos reproduce as that is where they lay their eggs. Additionally, El Niño further exacerbates the effects of infectious diseases by impacting food sources and leading to food insecurity and malnutrition. (SciDev.Net, 2022) This makes the effects of infectious diseases greater as it weakens people’s immune systems, increasing mortality. In short, El Niño, though not directly the cause, has contributed to the growth in infectious diseases and the worsening of them in Latin America.

“ El Niño has been attributed to as one of the factors of the dengue epidemic in Latin America which was previously eradicated.”

The weather pattern in the Pacific ocean usually blows winds west along the equator from South America to Asia, bringing warm water with it. El Niño and La Nina break these weather patterns and this can occur every 2-7 years and last 9-12 months. El Niño happens when winds weaken and push the warm water back to South America, causing dryer and warmer weather in the US and Canada but wetter seasons in South and

such as malaria, leptospirosis, cholera, zika and a new one called Oropouche virus which has been tagged by the Pan American Health Organization (PAHO) as an epidemiologic alert. (PAHO, 2024) The rising cases of these infectious diseases demonstrate the urgency of a complex issue that tackles both the environment and health.

Another critical piece is that El Niño is able to aggravate infectious disease rates because it creates a breeding

Moreover, climate change has strengthened the effects of El Niño causing extremes in rainfall, flooding, and hotter temperatures. El Niño of 2023 was one of the five strongest on record (World Meteorological Organization, 2024). This coincides with raised temperatures and natural disasters. Additionally, sea surface temperatures have had greater variability within the last couple of decades. “The most recent 50-60 years, for example, appears to be more energetic, with larger swings up and down, than the previous 50-60 years” (ENSO Blog, 2024). Sea surface temperatures have reached new extremes meaning that oceans are absorbing more heat from the atmosphere as a result of increased greenhouse gasses and carbon emissions that heat up the earth. This in turn not only affects

Source: Adobe Stock https://stock.adobe.com/images/bushfires-in-tropical-forest-release-carbon-dioxide-co2emissions-and-other-greenhouse-gases-ghg-that-contribute-to-climate-change/894180712?prev_url=detail

marine life but can further heighten tropical storms.

Despite PAHO recognizing El Niño as a notable impact on health in 1998, climate change efforts mitigating health outcomes have only recently gained attention and require further policy and government intervention. As climate change worsens El Niño, infectious diseases will have a greater window of opportunity for proliferation and infection. These trends in public health and climate change further stress the importance of environmental initiatives to reduce carbon footprints, greenhouse gasses and fossil fuel use. Additional screenings for infectious diseases such as early detection and proper infrastructure of public health systems are also needed to protect and help at-risk populations of infection. The relationship between climate change and infectious diseases is layered and requires more research to procure novel strategies in mitigating both environmental and health concerns. This issue is growing and getting worse each

cycle, resulting in thousands of deaths, the faster we resolve this the closer we are in preventing the next pandemic.

Edited By:

Vanessa Vu

Claudia Mazzeo. (2022, August 12). Enfermedades infecciosas empeoran debido al cambio climático. SciDev.net. https://www.scidev.net/america-latina/ news/enfermedades-infecciosas-empeoran-debido-al-cambio-climatico/

El Niño weakens but impacts continue. (2024, March 4). World Meteorological Organization. https:// wmo.int/news/media-centre/el-nino-weakens-impacts-continue

McPhaden, M. (2023, July 27). Has climate change already affected ENSO? | NOAA Climate.gov. Www. climate.gov. https://www.climate.gov/news-features/ blogs/enso/has-climate-change-already-affected-enso

Mora, C., McKenzie, T., Gaw, I. M., Dean, J. M., von Hammerstein, H., Knudson, T. A., Setter, R. O., Smith, C. Z., Webster, K. M., Patz, J. A., & Franklin, E. C. (2022). Over half of known human pathogenic diseases can be aggravated by climate change. Nature Climate Change, 12(12). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-02201426-1

National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. (2024, June 16). What Are El Niño and La Niña? Noaa. gov. https://oceanservice.noaa.gov/facts/ninonina. html

Tapia-Conyer, R., Méndez-Galván, J. F., & Gallardo-Rincón, H. (2009). The growing burden of dengue in Latin America. Journal of Clinical Virology, 46, S3–S6. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1386-6532(09)70286-0

Written By:

Esther Liu

In the last decade, antimicrobial resistance (AMR) has emerged as a critical health concern, with more than 2.8 million AMR infections recorded annually (CDC). These outbreaks occur when bacteria, fungi, and viruses no longer respond to antibiotics, causing an increase in disease transmission and illness. This pressing issue is often linked to the overprescription of antibiotics for bacterial infections, a practice that has persisted since the discovery of penicillin in 1928. Since then, bacteria have evolved to resist antibiotics, leading to the creation of new medicines that bacteria will learn to overcome, thus resulting in a never-ending “arms race.”

hospital-acquired bacterial pathogens: E. coli, K. pneumoniae, and S. aureus. Data was obtained from clinical isolates in hospitals or laboratory facilities where bacterial species, antibiotic susceptibility, year, and location of acquisition were well documented. The mean temperature was then linked to the recorded infection time and location, found on the US National Climatic Data Center. It was concluded that an increase in minimum temperature

pathogens. There is a positive correlation between warmer climates and horizontal gene transfer (HGT), the exchange of genetic material between organisms without parent-offspring interaction. This exchange typically occurs in high-heat environments, when stress mechanisms are triggered, making cell membranes more permeable to foreign DNA. This introduces mutations at a much faster rate, increasing the chances of antibiotic resistance.

“Many times it is the underserved communities that experience the highest rate of AMR due to insufficient knowledge on how to respond to climate disasters and how to seek care after contracting infections.”

was associated with increasing antibiotic resistance across the 3 analyzed pathogens.

Though antibiotic usage is thought to be the leading factor of AMR, other factors such as temperature and rainfall increase the rate of evolution and transmission among pathogenic bacteria (Di Cesare).

Temperature is known to directly affect the growth of bacteria by increasing its enzymatic activity. Over the last century, Earth’s temperature has increased by 2° F, most of the growth occurring in recent years (Lindsey). 2023 marked the warmest year on record since 1850. A database study conducted by Harvard University detailed how local climate variables affected the growth of community and

Additionally, it was found that antimicrobial resistance also varied between different geographical locations. A higher incidence of antibiotic prescription was noted in southern states, where temperature is generally warmer than in other areas of the United States.

Temperature change has also affected human interaction. Microbiologist Soojin Jang has noted that high temperatures often encourage people to stay indoors, promoting the spread of resistant strains that come with close proximity contact.

Not only is high temperature influencing the multiplication of microbes growing in an environment, but it also promotes mutation among virulent

High temperature is not the only climate-related aspect that promotes the spread of AMR. Excessive rainfall has indirectly introduced prime environments for bacteria to thrive in. Rainwater flows through different sites such as sewage and waste, where bacteria and other pathogens are present. It acts as a vehicle to then flow through areas, such as agricultural soil, where antibiotics are actively used for crop growth. After the bacteria become resistant to the newly exposed antibiotic, they continue to be carried to other areas and multiply with the assistance of rainwater.

This becomes a pressing issue during intense hurricane-caused floods, as we have seen recently with Hurricane Helene and Milton. Many people continue to consume tap water during the storm when the water supply is often contaminated with antibiotic-resistant bacteria. Its entrance into the host body causes detrimental health effects.

Although AMR occurs through natural evolutionary events, the main facilitators of the increased prevalence are human anthropogenic efforts.

From overprescribing antibiotics to overuse in plants and animals, antimicrobials are present everywhere in our community. Proposed solutions to

Source: Adobe Stock neirfy, https://stock. adobe.com/images/white-pills-in-orange-bottle-on-blue-background-close-up-with-copyspace/226352071?prev_url=detail

it is the underserved communities that experience the highest rate of AMR due to insufficient knowledge on how to respond to climate disasters and how

“Not only is high temperature influencing the multiplication of microbes growing in an environment, it is also promoting mutation among virulent pathogens.”

climate-caused AMR include improving the surveillance of sharp climate events, such as high temperature and rainfall, and AMR genes in wastewater to predict areas of potential outbreaks. For example, water samples would be collected during weather forecasting of intense rainfall to track the amount of resistant genes prevalent in the community. This data could then be analyzed to predict which communities would be most affected by an outbreak. Although this proves to be a starting effort, it is difficult to implement solutions across all areas. Many times

to seek care after contracting infections. However, these communities– where health resources should be most prevalent– are, in reality, extremely lacking due to inequities in the United States healthcare system.

Edited By:

Anna Smith

A. Di Cesare, E.M. Eckert, M. Rogora, G. Corno Rainfall increases the abundance of antibiotic resistance genes within a riverine microbial community Environ. Pollut., 226 (Suppl. C) (2017), pp. 473-478, 10.1016/j.envpol.2017.04.036

CDC. COVID-19: U.S. Impact on Antimicrobial Resistance, Special Report 2022. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, CDC; 2022.

Dahlman, Rebecca Lindsey AND LuAnn. “Climate Change: Global Temperature.” NOAA Climate.Gov, 18 Jan. 2024, www.climate.gov/news-features/ understanding-climate/climate-change-global-temperature#:~:text=Earth%27s%20temperature%20 has%20risen%20by,2%C2%B0%20F%20in%20total.

MacFadden, D.R., McGough, S.F., Fisman, D. et al. Antibiotic resistance increases with local temperature. Nature Clim Change 8, 510–514 (2018). https:// doi.org/10.1038/s41558-018-0161-6

Written By: Risha Rai

In 2021, over 2 billion people lived in water-stressed countries, and in 2022, at least 1.7 billion people only had feces-contaminated water sources available to them (World Health Organization, 2023). As an essential resource for all life, water isn’t just used for drinking; in fact, it facilitates disease prevention through good hygiene, which effectively prevents diarrheal diseases, respiratory infections, and many other tropical diseases. Contaminated drinking water contains harmful microbes that transmit diseases, the most prevalent of which are cholera, dysentery, E. coli, typhoid, and polio. These diseas-

es have been estimated to cause around 505,000 deaths per year worldwide (World Health Organization, 2023) due to symptoms ranging from diarrhea and fever to neurological disorders and liver damage (Levy et al., 2018). Diarrheal diseases, or infections that travel through feces, in particular have been found to have a profound impact on population health, with small changes leading to large-scale effects (Levy et al., 2018). Climate change on a global level has caused rising temperatures, increasing sea levels, droughts, floods, and a host of other issues; all of which have affected waterborne disease distribution, transmission, and severity.

Although bacteria can survive in a range of temperatures depending on the bacterial strain and environmental conditions, most generally thrive in warm temperatures and require water for reproduction (Qiu et al.,

2022). With rising temperatures due to climate change, freshwater sources have become a prime breeding ground for bacteria. Climate-change sensitive waterborne diseases have been observed to follow a seasonal pattern, with warm summer months corresponding to higher incidences of diarrheal infections like salmonella and campylobacteriosis; while viral infections are less common in increasing temperatures (Semenza & Ko, 2023). Water treatment plants are one of the most important ways contaminants are removed from the water supply, but rising temperatures can make this process more difficult and less effective through decreasing chlorination and increasing organic matter solubility; therefore increasing water turbidity.

NASA has identified that climate change has caused a 20-24% increase in the proportion of the population

Source: Adobe Stock Dr_Microbe https://stock.adobe.com/images/vibrio-mimicus-bacteria/548543278?prev_url=detail

exposed to floods, which is 10 times higher than estimates previously determined. By 2030, this number will further increase, putting more people in danger (Tellman et al., 2021). Floods cause sediments with fecal pathogens, and then, these pathogens on the urban landscape traverse large distances and contaminate freshwater sources like rivers and lakes. Areas with underdeveloped infrastructure are espe-

risk in children who were exposed to a 6-month severe drought (Wang et al., 2022). Handwashing is an important prevention tool, but its frequency also decreases during water scarcity as more is saved for drinking (Emont et al., 2017).

The World Health Organization (WHO) is attempting to reduce the spread of waterborne diseases through

“High demand for water combined with increased evaporation due to soaring temperatures, which concentrates pathogens, makes disease transmission easier than ever.”

cially at risk due to the lack of sewers and wastewater management systems. Even locations with sewers are at risk of overpowering the water treatment plants, leading to ineffective contaminant reduction and waterborne disease transmission (Semenza & Ko, 2023).

In addition to floods in coastal areas, droughts are another hallmark of climate change. High demand for water combined with increased evaporation due to soaring temperatures, facilitates disease transmission even more because it concentrates pathogens. Although wastewater treatment plants are currently 50-90% effective at removing pathogens (Okoh et al., 2010), this number decreases as pathogen concentration increases. At the same time, lower water pressures can lead to cross-contamination from parallel sewer lines, increasing the risk of exposure to waterborne pathogens (Semenza et al., 1998; Semenza & Ko, 2023). In fact, a study conducted in 51 low and middle income countries found that there was an 8% increase in diarrhea

establishing water quality guidelines and regularly testing water treatment products. To help underdeveloped countries, they have also created a report describing steps that countries can take to improve water quality and promote better hygiene (Geneva: World Health Organization & United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF), 2023). Although the best way to reduce waterborne disease transmission is by slowing down climate change, countries should invest in updated water treatment facilities to handle the demands of a world with climate change. Water quality monitoring programs and early warning systems are paramount to preventing cholera, typhoid, and other waterborne disease outbreaks. Relief programs can also greatly assist drought-affected nations by providing clean water and promoting preventative measures such as handwashing.

Edited By:

Marymar Vacio

Written By:

Emily Mrakovcic

410 million years ago, Scleactinian stony corals emerged during the Cambrian period and constituted the earliest reefs (Oliver, 2017). Since then, coral reefs have functioned as vital and biodiverse ecosystems to many species including fish, seahorses, sea turtles, and more. They also serve as vital resources for coastal communities, generating revenue through tourism while providing protection from coastal erosion. Many studies also show that coral has potential as biomedical and biotechnological substances (Richardson, 1999). Unfortunately, while coral reefs offer many benefits, infectious diseases exacerbated by climate change threaten to destabilize reef communities around the world.

2023). Additionally, the ocean serves as a carbon sink, absorbing excess carbon dioxide, which leads to ocean acidification and harms coral (Doney et al., 2009). At the current rate, it is estimated that we have entered a sixth mass extinction event (Wake et al., 2008). Unless human pressures on the environment are scaled back soon, a UN climate report predicts that 99% of coral reefs will be dead by 2100 (Charo, 2022). Unsustainable land-based human activities, including deforestation, poorly regulated agriculture, and urban development contribute to this dilemma (Rice et al., 2019), as they release excessive amounts of sediments into the water, land, and air.

A secondary study by Burke et al. in

2100.

Studies have shown that both incidence and severity of coral diseases are worsened by global warming (Thirukanthan et al., 2023). Considered one of the biggest threats to coral ecosystems, coral infectious diseases have skyrocketed in variety and number (Harvell et al., 2004) since their first documentation in 1965. Common coral diseases include black band disease, brown band disease, red band disease, and white plague. Tools used to characterize coral diseases, such as oxygen and sulfide-sensitive microelectrodes, microscopy, molecular genetics, metabolic and physiological methods, and remote sensing fields, have all helped characterize these diseases (Richardson, 1999).

“Considered one of the biggest threats to coral ecosystems, coral infectious diseases have skyrocketed in variety and number (Harvell et al., 2004) since their first documentation in 1965.”

Five major coral extinctions have occurred since the emergence of Scleractinia, all caused by rising temperatures and levels of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere (Dishon et al., 2020). Coral bleaching and its widespread damage to reef ecosystems has become increasingly common due to thermal stress from rising ocean temperatures (Thirukanthan et al.,

2023 examined 108 studies on global coral disease changes over time in relation to temperature. They followed two variables: summer sea surface temperature (SST) and cumulative heat stress as weekly sea surface temperature anomalies (WSSTAs). They found that both SST and WSSTA were associated with global increases in mean and variability of coral disease prevalence. Assuming moderate SST and WSSTAs, their model predicted that 76.8% of corals will be diseased globally by

Black band disease was discovered in 1973 and identified by its distinctive black band that moves across coral colonies while destroying coral tissue. The band’s lethality stems from the toxic microenvironment it creates in its path. Similarly, white band disease, discovered in 1977, utilizes a line of tissue destruction to target reef-building, branching corals in shallow reef crests. White band disease is known to be one of the most destructive coral diseases. Unlike black and white band diseases, the white plague lacks a migrating microbial population with a tissue-destroying line and instead can be identified by a sharp demarcation between freshly exposed

Source: Adobe Stock stephan kerkhofs, https://stock.adobe.com/images/fish-coral-and-ocean/27112628?prev_url=detail

coral skeleton and healthy coral tissue. Another notable coral disease is aspergillosis, a lesion-producing infection caused by a species of terrestrial fungus. Lastly, rhodotorulosis, also known as rapid wasting syndrome, is associated with the intercellular growth of a pathogenic fungus resulting in the rapid breakdown of coral tissue and skeleton (Richardson, 1999). In addition to the integral role coral reefs play in marine ecosystems, coral also offers beneficial medical capacities that make them even more important to preserve: anti-inflammation, anticancer, bone repair, dental deformity restoration, and neuroprotective properties (Cooper et al., 2014).

To ensure the longevity of coral reefs, there are many steps you can take, whether you live on the coast or not. Recycling and disposing of

trash properly, minimizing fertilizer use, using environmentally friendly modes of transportation, and reducing stormwater runoff all help reduce the burden of humans on Earth’s climate (U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, n.d.). On a larger scale, pressuring large corporations to reforest degraded lands, build and manage marine-protected areas, and reduce single-use plastics are also integral components of greenhouse gas reduction (Charo 2022). By jointly taking responsibility for our own actions while also holding companies accountable, we can reduce the negative impacts of climate change on a species that is a cornerstone of the life and health of humans and animals alike.

Edited By:

Dylan Lai

Written By:

Nelsa Tiemtoré

As climate change rapidly increases, the need to assess the health impacts of climate-related migration is becoming more prevalent. While more research needs to be conducted on this specific topic, there are sources from the recent years that may provide some insight.

Firstly, to provide a scope of the magnitude of climate change based displacement, it is necessary to examine a recent report from the World Bank, estimating the forceful movement of more than 143 million people due to climate change in 2050 alone, primarily in Latin America, Southeast Asia, and Sub-Saharan Africa (Guthman, 2023). Additionally, in 2019, the Global Peace Index Report pointed out that 61.5% of displacements were caused by climate-related disasters. Even in the United States, the impact is evident: about 900,00 Americans were displaced due to climate disasters in that same year.

impacts include altered fresh water availability, lower food security, and changing disease ecologies (Schwerdtle, Bowen, & McMichael, 2018).

One cansee these pictured in the cases of Somalia, South Sudan and Pakistan. Somalia, a nation heavily dependent on agriculture, has seen a significant decrease in the amount of rainfall per year, which has led to severe drought and now food insecurity. Additionally, the Somali economy has been affected due to the loss of agriculture, illustrating that “climate change acts as a threat multiplier, exacerbating existing sociopolitical and economic vulnerabilities” (Schwerdtle, Bowen, & McMichael, 2018). One can expect

gee crisis as it relates to climate change.

“As these climate change refugees migrate looking for resources, they are subjected to physical heat and humidity without access to basic needs. Oftentimes, the consequences are heat stroke, post traumatic stress disorder and anxiety.”

Currently, researchers have identified the main direct health impacts of climate change as being heat-related morbidity and mortality, disaster-related injury, while the indirect health

to see world economies and relations drastically change in response to the effects of climate change. While many nations have already banded together to take action through collaborations within the United Nations Climate Change Conference (better known as COP), much more needs to be done at a more rapid pace to counter the speed at which these natural disasters are occurring. With COP29 starting on November 11th, it will be interesting to see how nations will address the refu-

Similar to Somalia, the implications of rising temperatures in South Sudan have been crop failure, malnutrition, water shortages, and forced displacement as people need to migrate in search of resources. In the case of Pakistan, lack of rainwater is not the issue as in Somalia and South Sudan. Instead, as of 2022, a third of the country is now underwater, resulting in the displacement of 8 million people and a significant loss of crops. As land is lost, the issue of relocating people arises, as well as the inevitable possibility that the two-thirds of the land remaining may not hold enough resources to accommodate the current population as well as the people displaced, resulting in further proliferation of climate change refugees. As these climate change refugees migrate looking for resources, they are subjected to physical heat and humidity without access to basic needs. Oftentimes, the consequences are heat stroke, post traumatic stress disorder and anxiety (Schwerdtle, Bowen, & McMichael, 2018).

In Papua New Guinea, an island nation that is also dealing with rising sea levels, planned relocation has been used as a method of disaster risk reduction (Schwerdtle, Bowen, & McMichael, 2018). By creating incentives such as opportunities for livelihoods, and access to food and healthcare, the government of Papua New Guinea attempted to move people from one locality to another, in order to avoid the

exacerbation of resources (which would result in food insecurity) in the locality that was increasingly underwater and continued to lose crops. However, few civilians desired relocation from their homes.

While relocation may be seen as a possible solution to the climate change crisis, not all populations have the privilege of relocating. For example:

“Immobile Iñupiat community members face climate-related population health impacts, including increasing prevalence of climate-sensitive infectious disease, such as pneumonia, and skin infections secondary to deteriorating sanitation caused by climate change-related damage to water and sanitation infrastructure. Further, health is adversely impacted by climate-related food insecurity and weather-related injury…Permafrost thawing beneath the lakes that provide

drinking water threatens water security and affects agriculture, thus increasing the likelihood of new infectious disease being introduced through harvested and imported foods as well as by vectors migrating northward due to vegetation changes, e.g. beavers harbouring giardiasis” (Schwerdtle, Bowen, & McMichael, 2018).

On top of these health risks, these Iñupiat community members often struggle with mental health due the ways in which environmental changes lead to change in their sociocultural lives.

Indigenous populations in Australia are also battling declining mental health due to the rupture of social ties as more indigenous people transition to urban and western lifestyles in an attempt to avoid the cyclones, storm surges, flash floods, heat waves, coastal erosion, bushfires and drought dispro-

Guthman, P. (2023, March 6). Because of the climate crisis displaced populations face dangerous health impacts. “Outrider”. https://outrider.org/climate-change/ articles/because-climate-crisis-displaced-populations-face-dangerous-health-impacts

Schwerdtle, P., Bowen, K., & McMichael, C. (2018). The health impacts of climate-related migration. “BMC Medicine, 16”(1), 1-7. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916017-0981-7

portionately affecting their communities (Schwerdtle, Bowen, & McMichael, 2018). Of note, in addition to a decline in mental health, the transition of indigenous people in Australia to sedentary, urban and western lifestyles have resulted in an increase of noncommunicable diseases, including but not limited to type 2 diabetes, obesity, and cardiovascular disease.

Considering the drastic ways in which climate change is impacting health globally, both directly and directly, more needs to be done to address these new health implications. While no solution is clear, there is hope that nations will take the initiative to find ways to mitigate the situation as it is in their best interests to do so.

Edited By:

“The same policies that reduce carbon emissions can save millions of lives by improving air quality and preventing disease.”

– Ban Ki-moon, former UN Secretary-General “Our health systems must become as resilient as the planet we hope to protect from climate change.”

– Margaret Chan, former WHO Director-General

Written By: Álvaro Amir Uribe

An a world struck by the devastating impacts of climate change, the need to shift ground and act on a policy level grows increasingly imperative. Though not entirely unjustified, much of modern international and domestic policy has centered the fight against the refugee crisis on factors such as religion, socio-political turmoil, war, race, etc. (Freedman, 2023). But what room does this leave for adequately responding to the health burden of climate change displacement, such as that outlined in the Global Health section article by Nelsa Tiemtoré?

To better understand the aforementioned burden of displacement in the context of climate change, the Center for Strategic & International Studies (CSIS) provides an estimate that over the past decade, an average of 21.5 million individuals per year have been displaced due to floods, wildfires, droughts, and other weather events (Yayboke et al., 2020). For perspective, this projection is nearly nine times more than displacement due to asylum sought for fear of persecution and three times more than displacement due to conflicts (Figure 1; Yayboke et al, 2020). Evidently,

climate change poses grave implications for global displacement patterns. This blurb aims to emphasize how such refugee displacement disproportionately impacts the mountainous and desert regions of the Middle East.

It is beneficial to first delve into how mountainous regions at large are disproportionately impacted by climate change and subsequently, refugee displacement. In a 2024 policy brief by the International Organization for Migration, mountainous regions are identified as a critical impact area, considering that climate change poses repercussions in health through various

“Numerous policy shortcomings are encountered, rendering the projected 3 million Middle Eastern climate refugees vulnerable to the ongoing burden of adverse climate outcomes”

mechanisms (IOM, 2024). Not only does climate change impact physical safety through adverse weather such as landslides, floods, etc., but health is also impacted through impacted water accessibility (IOM, 2024). Unsafe water accessibility in such mountainous areas thus poses an entry point for devastating water and vector borne infectious diseases to ravage various indigenous mountain-residing populations (IOM, 2024).

One such region with a high proportion of mountain, desert, and remote

indigenous populations includes the Middle East / North Africa (MENA) region, thus making the MENA region one of critical focus among climate displacement discussions. The Middle East Institute highlights that in 2021 alone, 3 million individuals were forced to leave the MENA region due to causes related to extreme droughts, mountain landslides, sandstorms, and high temperatures (Freedman, 2023). Recent news emphasizing the violence of war in countries such as Palestine, Yemen, Syria, and Lebanon exacerbates the cycles of refugee displacement in these nations (Freedman, 2023). Climate change and war-associated displacement work hand in hand, shooting projections to an estimated 1.2 billion displaced refugees displaced across the MENA region (Freedman, 2023). One critical issue, however, remains on a policy level: climate refugees remain unprotected, without asylum provisions in various nations (Freedman, 2023).

The United States, for instance, has current immigration law that excludes climate refugees from eligibility requirements for refugee resettlement (Yayboke et al., 2020). As such, there is no formal domestic policy that resettles climate migrants, even if formal status is obtained (Yayboke et al., 2020). This is the unfortunate reality across various nations in countries neighboring the MENA region, such as Turkey and much of Europe (Freedman, 2023).

Source: (Yayboke et al., 2020)

The aforementioned CSIS and IOM attribute these policy restrictions to issues related to terminology and defining climate migration (Yayboke et al., 2020). By having such narrow definitions for national provisions of refugee asylum status, numerous policy shortcomings are encountered, rendering the projected billions of climate refugees vulnerable to the ongoing burden of adverse climate change outcomes. It is absolutely imperative for upcoming policy to firstly provide more funding to efforts that underlie climate displacement research, secondly incorporate climate change research into policy legislation, and thirdly maintain a focus on expanding the terminology used for defining refugee protections.

Edited By: Dylan Lai

Freedman, B. (2023, April 26). Getting ahead of the Middle East’s climate refugee conundrum. Middle East Institute. https://www.mei.edu/publications/ getting-ahead-middle-easts-climate-refugee-conundrum#:~:text=In%20the%20MENA%20region%2C%20 during,people%20are%20essentially%20climate%20 refugees.

International Organization for Migration. (2024, Summer). Human mobility in mountain areas in a changing climate. IOM. https://environmentalmigration.iom. int/sites/g/files/tmzbdl1411/files/documents/2024-11/ human-mobility-in-mountain-areas-in-a-changing-climate.pdf

Yayboke, E., Staguhn, J., Houser, T., & Salma, T. (2020, October 23). A new framework for U.S. leadership on climate migration. CSIS. https://www.csis.org/analysis/new-framework-us-leadership-climate-migration

Middle East Institute. https://www.mei.edu/publications/getting-ahead-middle-easts-climate-refugee-conundrum#:~:text=In%20the%20MENA%20region%2C%20during,people%20are%20essentially%20 climate%20refugees.

Source: Adobe Stock https://stock.adobe.com/search?k=middle+east+flood&search_type=usertyped&asset_id=479086127

Source: Adobe Stock https://stock.adobe.com/images/traditional-berber-village-in-the-desert-high-atlas-mountains-morocco/326606249?prev_url=detail

Achild of immigrants’ first time visiting the motherland: a special experience, often one of unsettling homesickness for a land they’ve never gotten to experience living in. In the poetry that follows, I write about this exact feeling that lingers in my heart after my first time visiting Morocco on a solo backpacking trip in June of 2023. This feeling of homesickness was exponentially amplified after a series of 6.8-magnitude earthquakes struck the High Atlas Mountains of Morocco, leading to the deaths of 2,960, profound injuries for 5,674, and the displacement of at least 500,000 Moroccans (Center for Disaster Philanthropy, 2023).

Earthquakes remain a far under discussed element of climate change. According to NASA, increased prevalences in droughts, glacial earthquakes, and human uses of water result in tectonic stress and thus, a higher prevalence in earthquakes (Buis, 2019). As touched upon in the article portion of my submission, adverse climate events–earthquakes,

droughts, landslides, disrupted ecosystems–have a particularly disproportionate impact on mountainous regions, many of which can be found in various regions of the MENA (Middle Eastern / North African) world.

Equipped with this knowledge, my processing of the 2023 Morocco earthquakes is and has continued to be extremely complex. My mind still attempts to wrap itself around robust systems of immigration and xenophobia: the role of high income countries and corporations in climate change, and resultant forced climate migration among low-middle income countries.

In the poetry that follows, I attempt to touch on this complex lived experience. I center my story around a little boy named Omar, my almost-name, whom I had befriended in the High Atlas village of Imlil. I write about my perspectives of him: a projection of myself, the almost life I could have lived, and the pain that comes with not knowing if he’s displaced or even alive. I write about his enthusiasm and awe upon hearing that I’m from America

juxtaposed with the unfortunate reality for Arabs in America. In the poetry that follows, I hope to paint a vivid picture of how climate change intersects with the systemic dimensions of discrimination, social factors, and politics.

Buis, A. (2024, October 22). Can climate affect earthquakes, or are the connections shaky? - NASA science. NASA. https://science.nasa.gov/earth/ climate-change/can-climate-affect-earthquakes-orare-the-connections-shaky/#h-human-uses-of-waterand-induced-seismicity

Center for Disaster Philanthropy. (2023, October 25). 2023 Morocco Earthquake. Center for Disaster Philanthropy. https://disasterphilanthropy.org/disasters/2023-morocco-earthquake/

Hiraeth: homesickness for a place that may never have existed, or that you cannot return to

What may never have existed

Imlil: a haze of stained glass, hues of red and blue

Omar: A projection of myself, a boy I once knew Sparkly eyes and open ears Omar gleamed, Illuminated by the elusive American Dream.

A place I cannot return to Shrouded by the mystery of Omar’s fate, Mirages, my mind can only create. Of his people, but not of his land, Grief of mystery–what remains beyond ash and sand? Regretful complacency–climate change is in our hands.

A ruthless gamble between displacement and death, My mind curses life’s ferocity under every breath. For my healing heart, your laugh was the remedy; Giggles of a young boy, not a 9-year old climate refugee. And if your giggles still dance in the heavens so free, May their echoes one day find their way back to me.

Written By:

Esther Liu

When it comes to climate change, we are all vulnerable– yet, not equally so. There exists great health disparities and varying degrees of climate impacts between local populations and countries. Sudan, located in North Africa, lies as one of the world’s top ten most climate-vulnerable countries. Since 2019, the country has experienced frequent flooding, causing large portions of agricultural land to be underwater. Amidst this climate crisis, civil war between two rival factions also broke out in Sudan’s capital, Khartoum, on April 15, 2023, causing further instability in this nation.

Politicians and journalists often attribute the cause of suffering in Sudan to climate change, reinforcing the narrative of environmental determinism. This belief—that environmental factors, like the climate, dictate human culture and societal development– is deep rooted in Western colonialism (Verhoeven). Historically, environmental determinism justified European imperialism, labeling countries in hotter regions near the equator as underdeveloped and in need of Western intervention. Today, calling Sudan’s instability a “climate war” allows political figures and journalists to blame the climate for

contaminated water, land degradation, and rural poverty, while downplaying the effects of war and political instability. This rhetoric echoes the same problematic framework that governed Sudan just a century ago.

Prior to the war, Sudan was already grappling with intense floods that destroyed agriculture and increased livestock death, causing famine in rural communities. However, the government intervened minimally, and the civil war has only aggravated these challenges. Both factions fighting in the war depend on Sudan’s natural resources—mainly oil—to fund their military operations. According to a recent episode in the BBC documentary series

evident, the long term effects of oil pollution threatens future generations as well. “When floods came to our area, water mixed with chemical waste, we started seeing babies born with no eyes,” said Chief of Rak, a settlement north of Bentu at the heart of oil fields. Doctors expressed the need for genetic testing to determine causes of congenital abnormalities but limited resources put restrictions on these hopes (Life at 50°C). This lack of direct evidence to prove the impact of pollution on human health has only granted more oil extractions without necessary preventative measures.

“It needs to be recognized that government instability and mismanagement makes Sudan particularly vulnerable to the devastating effects of climate change.”

Life at 50°C, 9 million pounds of crude oil is extracted daily in Sudan, causing frequent oil spills that contaminate nearby communities. Flooding caused by climate change only worsens the pollution by carrying this oil to community water sources– a contamination described as a “silent killer” by Bojo Leju, a former Sudanese oil engineer. Civilians express concerns about their only available water source: “We know it’s bad water but we don’t have anywhere else, we’re dying of thirst”.

While the immediate discomforts are

Floods have not only led to environmental pollution, but have also encouraged infectious disease outbreaks in the already-vulnerable communities experiencing famine. From January to September 2024, a total of 20,062 cholera cases and 622 deaths were recorded in Sudan (World Health Organization). Additionally, dengue fever, malaria, and measles also plague the area with an estimated 3.4 million children under five at high risk of contracting these diseases (UNICEF).

The civil war is only worsening this issue. Land damages due to airstrikes and heavy artillery cause mass displacement, facilitating the spread of disease (Atit). Contaminated water and minimal food, makes individuals migrating to temporary shelters even more vulnerable to infectious diseases. The war has affected healthcare sys-

Source: Adobe Stock https://stock.adobe.com/search?k=sudan+climate+change&search_type=usertyped&asset_id=413741140

tems, including access to vaccinations. UNICEF reports that Sudan’s national vaccination has decreased from 85% to 50% since the war started with an average of 30% in active war zones.

Although climate change has contributed to immense suffering for many in Sudan, the situation proves to be more complex. For instance, frequent floods were already a threat to health, but oil-polluted waters only exacerbate the problem. Framing the situation as climate-induced completely redirects the blame away from policymakers, who propelled the oil business for individual profits and inadvertently caused the oil pollution. Similarly, linking infectious disease outbreaks solely to climate change disregards the role of war in causing mass displacements and increasing the spread of water and vector-borne diseases.

While we are all vulnerable to climate change some countries experience more pronounced effects than others simply due to geographical factors. However, this cannot be the sole determinant of increased suffering in Sudan. It needs to be recognized that government instability and mismanagement makes Sudan particularly vulnerable to the devastating effects of climate change. Health, politics, and the climate interconnect to shape the wellbeing of individuals. This intersection demands a more comprehensive approach to humanitarian aid and relief in times of conflict.

Edited By: Ruviha Homma

UNICEF for every child. “UNICEF Airlifts More Lifesaving Vaccines to Sudan to Fight Concurrent Outbreaks.” UNICEF, 5 Oct. 2024, www.unicef.org/press-releases/unicef-airlifts-more-lifesaving-vaccines-sudan-fight-concurrent-outbreaks.

Verhoeven, Harry. “In Sudan, ‘Climate Wars’ Are Useful Scapegoats for Bad Leaders.” Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, 18 Apr. 2024, thebulletin.org/2024/03/ in-sudan-climate-wars-are-useful-scapegoats-forbad-leaders/#:~:text=The%20concurrence%20of%20 environmental%20degradation,how%20climate%20 change%20is%20already.

Atit, Michael. “Climate Change Exacerbating Sudan’s Instability, Experts Say.” Voice of America, Voice of America (VOA News), 28 Sept. 2023, www.voanews. com/a/climate-change-exacerbating-sudan-s-instability-experts-say/7288798.htm

“Life at 50°C - The Impact of Climate Change in South Sudan.” YouTube, uploaded by BBC, 12 July 2023, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2dg-0ik1NKM.

World Health Organization. “Multi-Country Outbreak of Cholera.” External Situation Report n. 19, 18 Oct. 2024, www.who.int/docs/default-source/coronaviruse/ situation-reports/20241008_multi-country_outbreak-of-cholera_sitrep_-19.pdf?sfvrsn=be9f29ce_3.

“Health disparities and climate change intersect to create hotspots where infectious diseases thrive, demanding urgent and equitable action.”

–Margaret Chan, former WHO DirectorGeneral

“Infectious diseases know no borders, but climate change ensures they disproportionately impact those least able to respond.”

–Peter Piot, microbiologist and public health leader.

Written By:

Joanna Renedo

In Rhode Island, between 2018 to 2022, 71% of emergency room visits for asthma were for children with RIte Care/Medicaid. (Rhode Island KIDS COUNT Factbook, 2024) It’s no coincidence these children also come from communities stricken with a history of redlining and structural racism. On top of these challenges, low-income communities of color are dealing with excess heat, toxic chemicals, poor air quality, and environmental disasters as a result of climate change. As climate change worsens, so do the conditions of low-income communities of color.

The populations most at risk to climate change are low-income communities of color whose conditions are exacerbated by environmental disasters and adverse effects. Increased asthma rates among the children of these communities are only one side effect of this syndemic. Recent studies have shown that older family members of these children are also suffering from increased cumulative stress, increased cancer rates, and increased disease risk. (Breakey et al., 2024) These communities already have a history of discrimination, lack of resources, and health disparities which lessen their survival rates. As such, further harm from climate

change is only making it more difficult for people to receive the care they need.

A syndemic occurs when “two or more diseases or health conditions cluster and interact within a population because of social and structural factors and inequities, leading to an excess burden of disease and continuing health disparities.” (Minority HIV/ AIDS Fund, 2024) The National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine identified climate change, environmental injustice, and structural racism as the three components of this active syndemic. Syndemics are harmful because they exacerbate existing health inequalities and compound

continue to make it nearly impossible to mitigate her disease. We closely monitor the vital signs that are important for patient care, but I had never considered a patient’s address to be one of them.” (Salas, 2024)

Dr. Salas struggled identifying a cure for her patient and felt powerless in the face of climate change and systemic racism. It’s an ongoing “missed diagnosis”, which Dr. Salas uses to pin-point environmentally-caused conditions that clinicians face when treating patients for exacerbated conditions such as asthma.

“‘We closely monitor the vital signs that are important for patient care, but I had never considered a patient’s address to be one of them’ (Salas, 2024)”

issues into greater health burdens.

Many children in low-income areas already suffer with challenges in accessing resources and the lived experiences of racism or discrimination, added on are the consequences of climate change. Dr. Salas, an emergency medicine doctor, details her experience treating a patient who has suffered from environmental racism:

“Suddenly, the albuterol and corticosteroid treatments feel like band-aids on a bullet wound. No matter what her mother or clinicians did, my young patient’s physical environment would

Though these issues touch on systemic problems hard to address, there are solutions. For example, Dr. Salas has proposed healthcare professionals to look into the environments their patient’s live in, as “patients’ detailed environmental exposure profiles, based on their home address, could be integrated into the electronic medical record to inform treatment plans.” This would alert the health care provider about toxic exposures and allow them to create a plan of care. A similar suggestion was made by researchers at the MGH Institute of Health Professions who suggested using the Environmental Protection Agency’s Environmental Justice Mapping Tool. This tool provides “location-specific data related to environmental and climate hazards as well as social determinants of health and health disparities” to healthcare providers. (Breakey et al., 2024) This option would provide more insight into the environmental

Source: Adobe Stock https://stock.adobe.com/search?k=slum&search_type=usertyped&asset_ id=389390442

complexities communities face for the healthcare provider to address as it also provides conditions many in the community are struggling with. Though these efforts would help mitigate the issue for now, policy change is needed

funding for research to design safer alternatives to chemicals in consumer products and develop programs to address adverse health and environmental effects in low-income communities of color. By recognizing and acting on

“It’s an ongoing ‘missed diagnosis’, [the] environmentally-caused conditions that clinicians face when treating patients for exacerbated conditions such as asthma.”

to address environmental injustices.

More research needs to be done investigating the inequalities marginalized communities experience to help support bills and proposals sent for legislature. Bills such as the Environmental Justice For All Act, establish environmental justice requirements such as community impact reports and also create advisory bodies for strategies. In addition, this bill would create grant

these injustices, environmental health solutions can be made to lessen climate change’s impact on vulnerable communities. As Dr. Salas has said, it feels like putting “band-aids on a bullet wound,” emphasizing the need for policy and long-lasting health and equity resolutions.

Edited By:

Breakey, S., Hovey, D., Sipe, M., & Nicholas, P. K. (2024). Health Effects at the Intersection of Climate Change and Structural Racism in the United States: A Scoping Review. The Journal of Climate Change and Health, 100339–100339. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joclim.2024.100339

Duckworth, T. (2021, March 18). S.872 - 117th Congress (2021-2022): Environmental Justice For All Act. Www.congress.gov. https://www.congress.gov/ bill/117th-congress/senate-bill/872

Gutschow, B., Gray, B., Ragavan, M. I., Sheffield, P. E., Philipsborn, R. P., & Jee, S. H. (2021). The intersection of pediatrics, climate change, and structural racism: Ensuring health equity through climate justice. Current Problems in Pediatric and Adolescent Health Care, 51(6), 101028. https://doi. org/10.1016/j.cppeds.2021.101028

Minority HIV/AIDS Fund. (2024, April 29). Defining the Term “Syndemic.” HIV.gov. https://www.hiv.gov/blog/ defining-the-term-syndemic

National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine . (2022). Communities, Climate Change, and Health Equity. In National Academies Press eBooks. National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine . https://doi.org/10.17226/26435

Rhode Island KIDS COUNT Factbook. (2024). Children with Asthma. https://rikidscount.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/children-with-asthma_fb2024.pdf

Salas, R. N. (2021). Environmental Racism and Climate Change — Missed Diagnoses. New England Journal of Medicine, 385(11), 967–969. https://doi.org/10.1056/ nejmp2109160

Written By:

Rishi Rai

Natural disasters, including earthquakes, storms, floods, and droughts, kill between 40,000 and 50,000 people per year (Ritchie & Rosado, 2022). While this number is a small percentage of the global population, underserved areas are significantly affected, and disasters in specific areas can lead to displacement, waterborne diseases, overcrowded shelters, strained healthcare services, and higher chances of contracting an infection in the future. Although deaths from natural disasters have decreased over the past century due to technological improvements in calculating disaster risk and setting up early warning systems, climate change has led to more frequent natural disasters, with some sources reporting that “the number of climate-related disasters has tripled in the last 30 years” (5 Natural Disasters That Beg for Climate Action, 2022). Natural disasters also pose an increasingly high financial burden, with economic damages having doubled over the last seven decades after accounting

for inflation (Ritchie & Rosado, 2022).

Natural disasters displace large numbers of people, forcing them to seek refuge in crowded, unsanitary shelters with frequent disease outbreaks. The conditions in these shelters combined with waterborne diseases spread by flooding, hurricanes, and earthquakes have led to the spread of cholera, typhoid, and hepatitis A. The 2005 earthquake in Pakistan led to a 42% surge in diarrheal diseases in refugee camps, and similarly, 85% of survivors

Source: https://www.usnews.com/news/health-news/articles/2022-06-22/disaster-disparities-natural-hazards-climate-change-threaten-underserved-communities

living in Calang shelters were diagnosed with diarrheal diseases after the 2004 Indonesia tsunami (Nashwan et al., 2023). While high-income countries can combat the spread of such diseases by providing safe drinking water, better sanitation, more disease surveillance, and higher-quality nutrition, low and middle-income countries do not have the resources to adequately support

thousands of refugees (Nashwan et al., 2023). While disparities between low-income and high-income countries have been observed, natural disasters have also caused divisions between individuals with different socioeconomic statuses within high-income countries. A study conducted by MetroHealth researchers found that natural disasters disproportionately affect adults from underrepresented backgrounds, with people of color, LGBTQ+ minorities, people with disabilities, and low-income individuals being more likely to experience food and water shortages, electricity outages, and infectious diseases (Aung & Sehgal, 2024). The US Federal Emergency Management Agency created a National Risk Index to quantify the dangers citizens around the country face from extreme weather events caused by climate change. An analysis conducted by the U.S. News & World Report found that some minority groups, namely Alaska natives, American Indians, Native Hawaiians, and Hispanics, were at the highest risk of being affected by tornadoes and hurricanes, while majority groups faced much lower chances due to their ability to purchase more expensive homes in safer locations (Johnson, 2022).

Having limited access to health and medical services, underserved populations are especially disadvantaged

during natural disasters. Low-income countries have inadequate healthcare budgets, contributing to medicine scarcity, overwhelmed healthcare facilities, and fewer healthcare workers willing to work for low wages. The World Health Organization found a defi-

threats worldwide through partnering with other organizations and increasing the healthcare workforce in developing countries to meet the nationally mandated Sustainable Development Goals (Department of Health and Human Services, 2016). The World Health Or-

“The 2005 earthquake in Pakistan led to a 42% surge in diarrheal diseases in refugee camps, and similarly, 85% of survivors living in Calang shelters were diagnosed with diarrheal diseases after the 2004 Indonesia tsunami”

cit of 4.3 million healthcare workers globally, with a majority of the deficit coming from low-income countries in South Asia and Africa (Nashwan et al., 2023). Natural disasters only worsen these statistics as studies have found that over 50% of hospital staff are unable to work after a flood (Yusoff et al., 2017). The flooding in Pakistan led to a healthcare access shutdown for 650,000 pregnant women in the hospital. In addition to causing a 0.5% dip in female fertility post-disaster, many expecting mothers were at a high risk of contracting infectious diseases during this vulnerable time, leading to a sustained hospital admission rate of around 12% for pregnancy-related concerns (Nashwan et al., 2023).

Although health disparities caused by natural disasters continue to affect people globally, society can take key steps in the right direction toward closing the gap. Health systems funded by high-income countries, such as the US Department of Health and Human Services, continue to assist disadvantaged countries through their global strategy to detect and respond to health

ganization is also working toward reducing health inequality by reforming taxes on the wealthy and multinational corporations and providing debt-relief to low-income countries facing natural disasters through the processes outlined in their “Health for All” report (World Health Organization, 2023). These initiatives combined with the extensive research and data in the healthcare sphere illuminate a promising path toward reducing global health disparities.

Edited By:

Lisa Miyazaki

5 natural disasters that beg for climate action. (2022, May 25). Oxfam International. https://www.oxfam.org/ en/5-natural-disasters-beg-climate-action

Aung, T. W., & Sehgal, A. R. (2024). Prevalence, Correlates, and Impacts of Displacement Because of Natural Disasters in the United States From 2022 to 2023. American Journal of Public Health, e1–e11. https://doi. org/10.2105/AJPH.2024.307854

Department of Health and Human Services. (2016). The Global Strategy of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (p. 62).

Johnson, S. R. (2022, June 22). The Demographics of Disaster. US News & World Report. //www.usnews.com/ news/health-news/articles/2022-06-22/disaster-disparities-natural-hazards-climate-change-threaten-underserved-communities

Nashwan, A. J., Ahmed, S. H., Shaikh, T. G., & Waseem, S. (2023). Impact of natural disasters on health disparities in low- to middle-income countries. Discover Health Systems, 2(1), 23. https://doi. org/10.1007/s44250-023-00038-6

Ritchie, H., & Rosado, P. (2022). Natural Disasters. Our World in Data.

World Health Organization. (2023). Health for All –transforming economies to deliver what matters. World Health Organization.

Yusoff, N. A., Shafii, H., & Omar, R. (2017). The impact of floods in hospital and mitigation measures: A literature review. IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering, 271(1), 012026. https://doi. org/10.1088/1757-899X/271/1/012026

Written By:

Emily Mrakovcic