The legacy of Professor José Amor y Vázquez

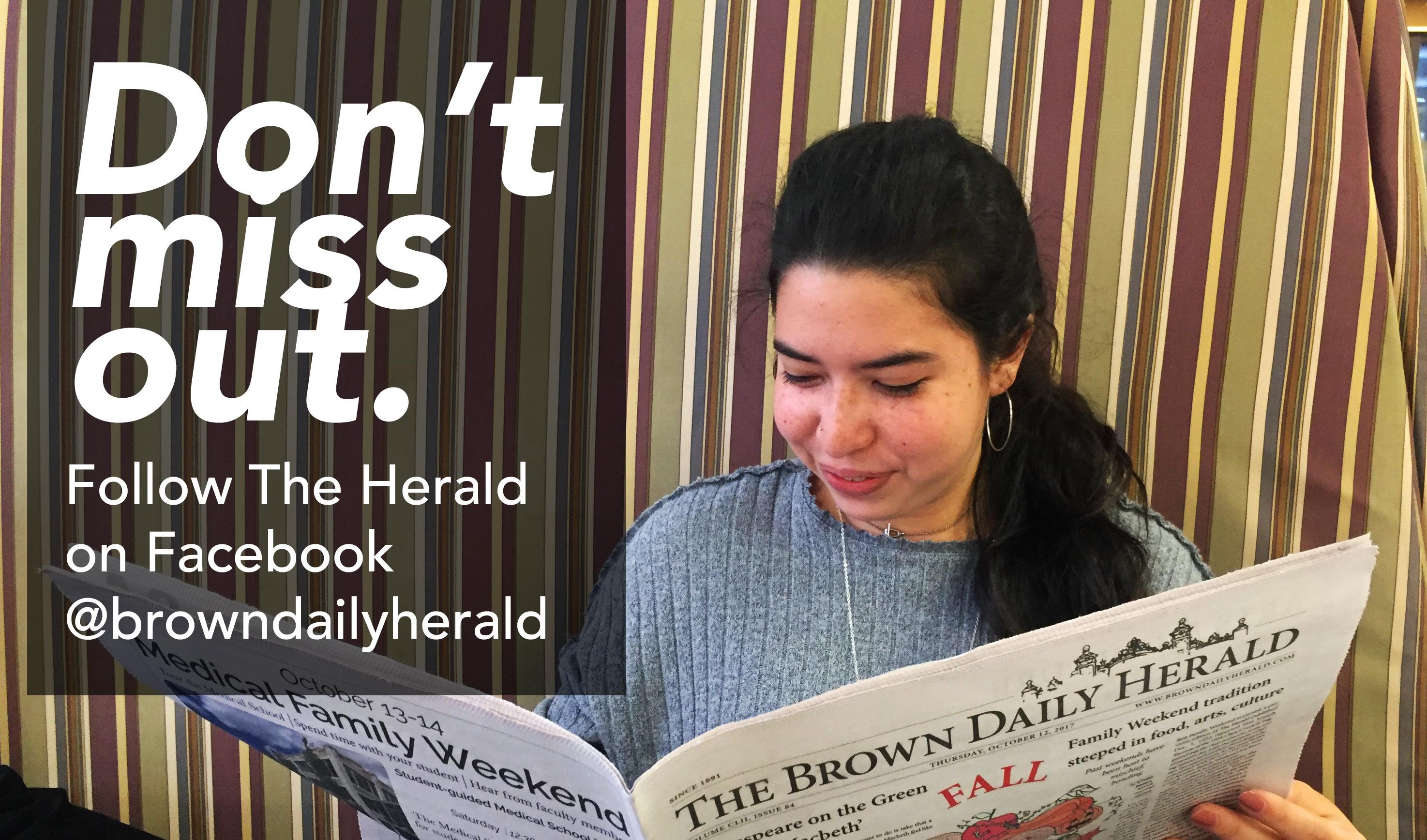

Amor y Vázquez supported John Carter Brown Library, Latin American studies

BY KAITLYN TORRES AND ALEX NADIRASHVILI UNIVERSITY NEWS EDITORS

Under the dim lighting of her office, Professor of Hispanic Studies Mercedes Vaquero sits in a cozy chair surrounded by walls of colorful posters. Located in Rochambeau House, home of the De partment of French and Francophone Studies, her office boasts a variety of knick-knacks, like a bronze medallion — engraved with Spanish artist Lorenzo Goni’s illustration of a flying witch — which sits atop her desk. Her bookshelf is brimming with the weathered spines of old books, including “El Tapaboca,” written by José Amor y Vázquez Ph.D’57.

“I inherited this office from Pepe,” Vaquero said, referring to Amor y Vázquez, late professor emeritus of Hispanic studies. Many of the trinkets around the office once belonged to Amor y Vázquez, including those on

METRO

Vaquero’s desk.

Amor y Vázquez arrived at Brown as a graduate student in 1951, spending the next six years on his Ph.D. In 1958, Amor y Vázquez became a faculty mem ber of the Department of Hispanic Stud ies — then known as the Department of Spanish and Italian — becoming the second Hispanic professor in its history.

Amor y Vázquez remained in the department until his retirement in 1991,

Protests in Iran advocate for women’s rights

championing women’s rights.

when he became a professor emeritus. During his tenure at the University, Amor y Vázquez was instrumental in establishing the Latin American Studies Program, which grew into the Center for Latin American and Caribbean Stud ies. He was also deeply supportive of the John Carter Brown Library, in 2004 establishing the José Amor y Vázquez

U. holds student listening session on provost search

ities related to admissions, financial aid, implementing policies, budgeting and “making sure things run smoothly,” Paxson explained. She also said the provost will have a significant role in working with deans and academic lead ers to create “diverse and inclusive en vironments with academic departments and schools.”

BY EMILY FAULHABER UNIVERSITY NEWS EDITOR

President Christina Paxson P’19 led a student listening session for the ongoing provost search in Petteruti Lounge Thursday. Students in atten dance shared questions, comments and suggestions with Paxson and search committee members Nicole Gonza lez Van Cleve, associate professor of sociology, and Jennifer Friedman ’92 MD’96. The event was open to under graduate, graduate and medical school students.

Provost Richard Locke P’18 an nounced in August that he would depart his role as provost at the end of 2022 to become vice president and dean of Apple University, The Herald previously reported.

The provost will have responsibil

Paxson and the provost will work “really close on taking the vision of where (the University) is going and actually executing it,” she said.

In September, Paxson announced that she would lead a search committee, The Herald previously reported.

The committee comprises ten fac ulty members from “all over the Uni versity,” Paxson said.

Gonzalez Van Cleve said that the committee is looking for a provost can didate with “exceptional judgment … (who) operates with integrity… (and) broad intellectual interest.”

While previous provost search committees have included students, Paxson said, the search committee for Locke’s successor does not. Rath

ARTS & CULTURE

Latin American literature over time

BY ALEX NADIRASHVILI UNIVERSITY NEWS EDITOR

Mahsa Amini was 22 years old when Tehran’s Guidance Patrol — a dedicated morality police established by the Islam ic Republic of Iran that enforces strict dress codes for women — apprehended her for improper dress and drove her to a detention center for re-education.

Mahsa Amini was 22 years old when just two hours after her arrest she fell into a coma and was transferred from the police station to a hospital. Two days later, she died from a heart attack, despite her family members’ claims that she did not have any pre-existing conditions. The Iranian government has since released edited footage of Amini at the police station, raising suspicion that she was abused by authorities be fore going to the hospital.

Mahsa Amini was 22 years old when her death sparked protests across Iran

“These protests have not only crossed lines in terms of provinces in areas of Iran, but class lines,” said Manijeh Nasrabadi, assistant profes sor of women’s, gender and sexuality studies at Barnard College, during an event entitled “Iran Protests: Gender, Body Politics and Authoritarianism” co-hosted by the Watson Institute for International and Public Affairs and the Center for Middle East Studies.

“They have brought out the re ligiously devout people as well as more secular people,” Nasrabadi said. “There’s this deep, embodied sense that the killing of Amini could happen to any woman, any day. And people are just not willing to continue to live like that under daily fear.”

Protests began Sept. 17 at Amini’s funeral in Iran’s Kurdistan Province and have since spread across the country and the globe. Led largely by women, these demonstrations have included women going out in public without hi jabs, burning their veils and publicly cutting their hair as symbols of defi ance against the government’s veiling mandate. Recent estimates suggest that

BY AALIA JAGWANI ARTS & CULTURE EDITOR

Throughout the history of Latin America, writers have challenged no tions of a white-dotminated literary canon by leaving an undeniable mark on literature in their home countries and across the world. Take Gabriel García Márquez, for example, who “deeply influenced” the British-In dian Salman Rushdie, or Jorge Luis Borges, who has been regarded as one of the most influential writers of the 20th century.

But beyond the household names of García Márquez and Borges, a deeper diversity and richness of Latin American literature remains widely underappreciated. Reflecting more earnestly on the role Latin American writers and creatives have played in shaping modern literature contrib utes greatly to conversations about world literature and sociocultural change across the region at large.

A Latin American literary tradition Literature has historically allowed Latin American nations to “imagine themselves as national communities,” while also providing “ways in which they resisted or reacted to nationaliz ing tools by the state,” said Associate Professor of Hispanic Studies Felipe Martínez-Pinzón. Different works of Latin American literature draw from written archives, oral histories and Indigenous and diasporic stories, he added, forming a more fluid form of history.

“There’s a long history in Latin America of literary and political cul ture being quite close in the sense that a lot of literary writers are also political

figures,” said Associate Professor of Comparative Literature and Hispanic Studies Esther Whitfield, citing the well-known Peruvian novelist and poli tician Mario Vargas Llosa as an example.

“Most Latin American countries became independent beginning in the early 1800s, and that’s the time when a literary culture started developing as well,” Whitfield added. “The sense of an independent literary culture really went hand in hand with the sense of an independent political culture too.”

More recently, since the late 19th century, Latin American literature has also carved out a place for itself “sep

THE BROWN DAILY HERALD BROWNDAILYHERALD.COM SINCE 1891 FRIDAY, OCTOBER 7, 2022VOLUME CLVII, ISSUE 50 Marielle Segarra ’10 starts hosting NPR podcast “Life Kit” Page 4 Gaber ’23: Attitudes on campus threaten Open Curriculum ethos Page 8 Yale professor Cécile Fromont discusses Italian images Page 12 U. News Commentary U. News 75 / 52 59 / 42 TODAY TOMORROW DESIGNED BY ANNA WANG ’26 DESIGNER TIFFANY TRAN ’26 DESIGNER JULIA GROSSMAN ’23 DESIGN EDITOR

UNIVERSITY NEWS

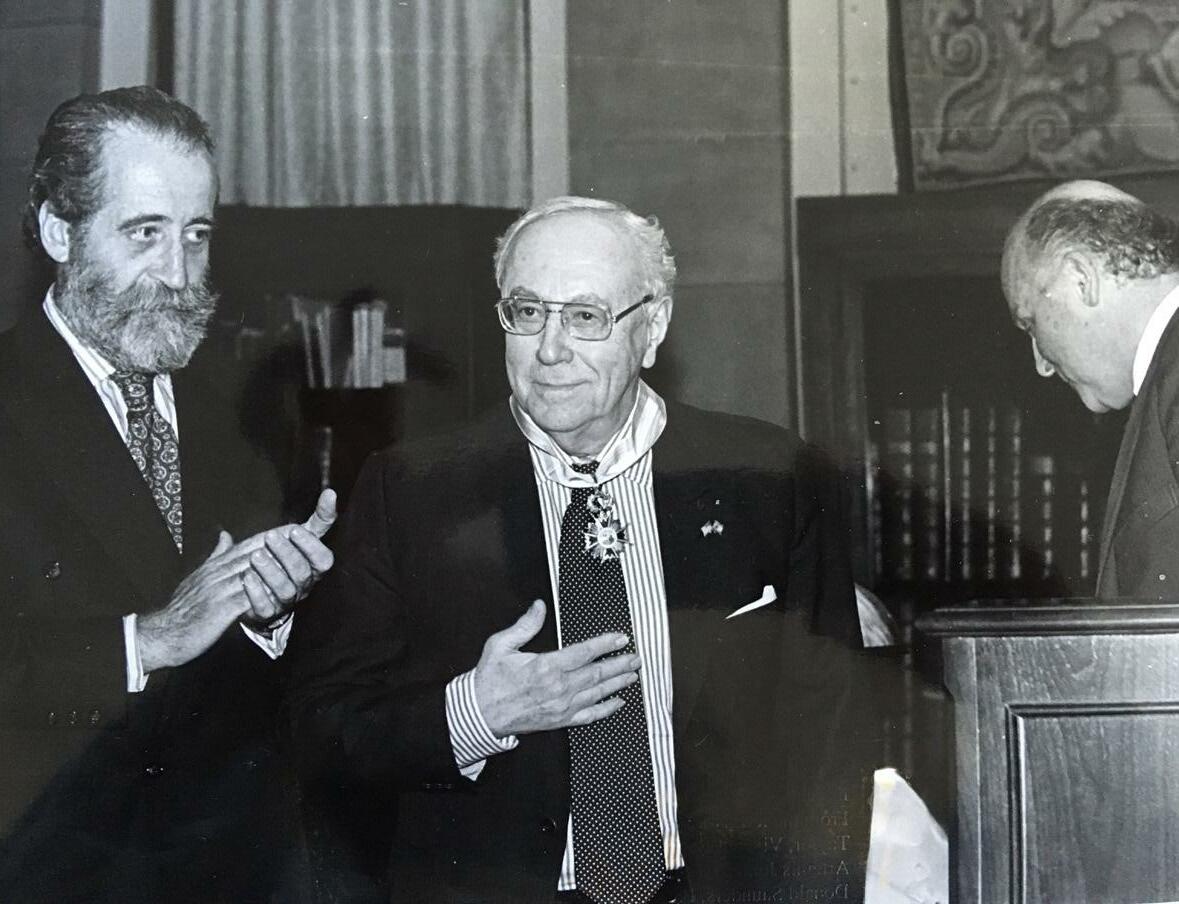

COURTESY OF DOMINGO LEDEZMA

Jose Amor y Vazquez Ph.D ’57 became the second Hispanic professor in the Hispanic Studies department in 1958.

UNIVERSITY NEWS

Student attendees share concerns, questions with Paxson, search committee members

SEE PROVOST PAGE 2SEE PROFESSOR PAGE 6

U. community members speak on protests, economic sanctions, hopes for future

Faculty offer insight into Latin American literary traditions, cultural influence

SIMONE STRAUS / HERALD

SEE PROTESTS PAGE 3 SEE LITERATURE PAGE 6

er than formally including students in the committee, input will be provided by leaders of the student governance groups who will meet with the “end stage finalists.”

Isaac Slevin ’25 asked if there would be a student town hall once the fi nal candidates are decided upon, and Paxson responded that a town hall would not be held due to confidenti ality concerns.

“Most of the people who put their hat in the ring for a search like this, their employers (and) colleagues do not know they’re applying,” Paxson said. “I don’t want to limit the search that way.”

Gonzalez Van Cleve brought up her concerns of “backlash” against can didates of color and added that the committee wants confidentiality to ensure the pool of applicants is “as diverse as possible.”

Sophie Lazar GS spoke about her experience in the School of Public Health’s Masters of Public Health program and its lack of STEM cer tification.

“For international students grad uating, it puts them at a very signif icant disadvantage in entering the job market,” Lazar said. To increase the “global competitiveness” of the MPH program, Lazar emphasized the

need to revamp the MPH program along with other graduate school programs.

Paxson explained that the Office of Global Engagement is under the direction of the provost’s office and that the new provost could work to ward making the graduate programs more competitive globally. Lazar and other attendees requested that the new provost focus on establishing more global health partnerships, such as allowing colleagues in oth er countries where Brown students conduct research to access University resources.

“I learned so much from my Kenyan colleagues,” Lazar said, referencing her time researching in Kenya.

Besides the University’s global impact, students voiced concerns about the importance of the future provost prioritizing sustainability efforts.

“Different candidates come from different backgrounds (and) have different opportunities to express a commitment to sustainability,” Pax son said. The committee took note of student concerns and indicated that they would ask about sustainability in the interview process.

Isabella Garo ’24 asked that the committee find a provost who would prioritize student accessibility to classes, such as through posting PDF

EMILY FAULHABER / HERALD

The provost has responsibilities related to admissions, financial aid, implementing policies, budgeting and “making sure things run smoothly,” according to President Christina Paxson P’19.

versions of readings or providing Zoom options for class.

Requiring textbooks or print ver sions of readings is a “huge block” for lower-income students, Garo said.

Paxson said that the future provost will work with faculty to understand how “the rules of engagement or poli cies within the classroom might impact students differently.”

At the session’s conclusion, Paxson encouraged students to submit memos or emails with further concerns and suggestions to Marguerite Joutz, Pax son’s chief of staff.

2 FRIDAY, OCTOBER 7, 2022THE BROWN DAILY HERALD | NEWS

PROVOST FROM PAGE 1

around 133 people have been killed as a result of government retaliation against these protests.

“The protests need to be under stood, not only in reaction to the death of a young woman, … but also in reac tion to the attempted cover-up by the government,” said Nadje Al-Ali, director of Middle East studies. “Instead of the government coming out and saying, ‘Oh, we don’t know what happened, we need to investigate,’ … (there was) total denial.”

These protests “are infused with the mood of younger generations who have no ideological attachment to the government,” Nasrabadi said. “There is an overwhelming rejection … (of) a system that is really not working. It’s not working economically, it’s not working socially (and) it’s not working politically.”

“A lot of parents and grandparents got to see what Iran was like at its peak, when it was actually (a) society worth living in,” said R., an Iranian-born un dergraduate student who requested an onymity due to safety concerns. Since the end of the Iranian Revolution in 1979, the country has been an Islamic republic.

The younger generation did not see that peak, R. added. “It lights a fire in them. … They want that chance at the kind of life that their grandparents had long before.”

While so far the protests have been brought together without set leader ship, Al-Ali believes the government is worried that the protests will become a more coherent and focused movement.

“The government is not just stand ing still,” she said. “They are reacting. They feel very threatened.”

One of the major ways that the gov ernment is stifling protests — especially to stop them from reaching global audi ences — is by blocking internet access due to the major role social media has played in organizing protests.

“I don’t know much about my fam ily (in Iran) because the internet has been cut off and we have basically no means of communication,” said Mateen

Markzar ’26, whose family is from Iran. The country is “like a black hole, and you don’t know what’s going on there.”

The government has also carried out deadly missile and drone strikes in northern Iraq, targeting the head quarters of three Iranian Kurdish op position parties who are supporting the ongoing protests. Most recently, Iranian security forces beat, shot and detained students of Tehran’s Shar if University, who began protesting against the Iranian regime by refusing to attend class.

While protests in Iran are nothing new — for example, the 2009 Green Movement — Nasrabadi believes that this is the first time where women’s issues are at the center of national demonstrations.

“The current uprising really does inherit the legacies of all the past mo bilizations, but it also moves in some really distinct new directions,” she said.

“People are protesting against the mandatory wearing of the veil, but also protesting against the so-called morality police controlling women’s dress codes and arresting and punishing women,” Al-Ali added. “This issue of women’s rights is not seen anymore to be a side issue, but is recognized (as being) at the heart of a wider critique of the Islamic Republic. … They’re actually challenging … the regime.”

Al-Ali pointed to the severe eco nomic sanctions placed on Iran by countries like the United States as motivating additional civilian unrest. But she also encouraged people to con sider how the sanctions themselves have worsened conditions for Iranian women and how lobbying for lifting sanctions could play a crucial role in providing them support.

In times of economic crisis, wom en suffer disproportionately from un employment and “a lack of access to resources, whether it’s healthcare or childcare,” she said. “Women are at the forefront of experiencing poverty.”

Al-Ali hopes that the protests, at the very least, force the Iranian gov ernment to lessen some of the extreme crackdowns on the mandatory nature of veiling and control of women’s dress. More substantially, she hopes these

protests open up political spaces to have less patriarchal, authoritarian regimes.

“Revolutions are not made from one day to the next,” she said. Still, “it’s clear that there is this large percentage of the population who are not happy with the way things are.”

Nasrabadi encouraged all those made aware of the conflict, especially students at the University, to sign sol idarity statements pressuring depart ments and administrators to condemn the violence in Iran. “We can really use our voices here to shine a light for the whole world to see what’s happening,”

she said.

“These women are literally put ting their lives on the line to fight for things that they believe in, and I wish there was more than I could do here,” Markzar said. Markzar is trying to “in crease awareness for what is going on” among his peers by posting to social media, hoping to supplement limited media coverage.

Al-Ali also warned people to avoid succumbing to Islamophobic “stereo types about ‘poor, oppressed women’” which reify the idea that the hijab is a problem.

R. believes that the Islamic Republic

of Iran itself is not a representation of true Islam.

“My grandma says the least Islamic thing she knows is the Islamic Republic of Iran,” R. said, explaining that Iranian women are just fighting for the option to choose whether or not they want to wear a hijab.

“I’m glad that people are taking notice (of the protests) – just remem ber that it’s nothing new,” R. added. “There’s so many women that we need to remember that died just like Amini did” and “were never noticed.”

“This is a fight for survival,” Markzar said. “It’s a fight for freedom.”

FRIDAY, OCTOBER 7, 2022 3THE BROWN DAILY HERALD | NEWS

COURTESY OF DARAFSH KAVIYANI / WIKIMEDIA COMMONS

Protests began at Mahsa Amini’s funeral on Saturday, Sept. 17. Led primarily by women, they have since spread across the country and internationally.

PROTESTS FROM PAGE 1

‘Her voice is worth listening to’: Marielle Segarra ’10 starts as NPR host

BY CALEB LAZAR UNIVERSITY NEWS EDITOR

When Marielle Segarra ’10 joined WBRU, the University’s radio station, at her RPL’s urging her sophomore year, a career in radio wasn’t on her radar. She wanted to be a journalist, but she thought she would end up working in print.

“I didn’t know what a career in radio would look like,” Segarra said. “I didn’t even really know what (Na tional Public Radio) was.”

But Segarra quickly fell in love with broadcasting. Segarra worked at The Herald during college — some times writing alumni profiles of her own — but she found her passion in radio.

Last month, Segarra started a new job as the host of NPR’s “Life Kit,” a podcast and radio show that provides advice on topics ranging from invest ing to making playlists.

Segarra compared the sounds she heard on the radio to those she heard in dance as a child.

“I loved tap because I loved the feeling of my tap shoes on the wood en floors. It was this sound thing that I really liked the resonance of,” Se garra said. “There’s something about that to radio as well, when you’re talking to a mic and you hear those voices in your headphones. It feels really resonant and tactile to me, working with sound.”

“I think that’s when I started feel ing that connection,” Segarra added. “We just have to kind of follow those breadcrumbs, right?”

Diana Geman-Wollach ’10 met Segarra during their second year at Brown through an English class and the two became fast friends. They worked together at WBRU.

“Marielle’s very easy to get along with,” Geman-Wollach said. “She’s always got a lot of banter, great comments, and we just clicked right away.”

That easy banter fueled Segarra and Geman-Wollach’s work together on WBRU, whether they were “tag ging each other on air” or “dancing in the newsroom.”

Segarra worked at WBRU during the school year as well as during two summers. Her entertainment news name was Daphne — inspired by “Scooby Doo,” she said.

“We had a couple cars that were pretty beat up, but we would drive them around Rhode Island and report on different things. It wasn’t just stuff on campus,” she said. “I felt like a reporter already.”

After graduating with a degree in English nonfiction in 2010, Segarra faced challenges in the job market.

“There were still a lot of scars from the recessions, and so there was a build up of people who want ed journalism jobs and not enough to go around,” Segarra said.

She worked in unpaid intern po sitions for 10 months, including at WBUR. During that time, Segarra lived with Sarah Rosengard ’11, whom she met while volunteering to teach ESL to recent immigrants in downtown

Providence. They lived in Providence during Rosengard’s senior year, then in Boston.

“We tried to establish what we (would) do as adults that year,” Rosen gard said. “We would have roommate nights where we cooked together, and we had a lot of parties for every sea son.”

“There was this time that I was away for five weeks on a research ship across the ocean, and Marielle said she sometimes slept in my bed because she missed me,” she added.

While in Boston, Segarra found a job writing for CFO, a financial maga zine, through a Brown alum. Financial reporting was “definitely not a thing that I was naturally interested in” or had “any experience with,” she said.

“The audience members were ex perts in this thing. It wasn’t the usual — for most audiences you are trying to really simplify things and (are) assum ing that they might not be experts on this particular thing,” she said. “But if you’re writing for experts and you’re not an expert, then you’re really turned around. You have to learn it for your self first, simplify it for yourself and then put it back into semi-technical language and not over explain.”

Segarra’s job paid for an accounting class at night, where she learned to write out financial statements.

“On one of our exams, we got a bunch of information about a company and we had to write, by hand on a blank

sheet of paper, the statement of cash flows and the balance sheet,” she said.

Beyond learning about finance, Segarra’s position at CFO challenged her to find her voice.

“I also was interviewing corporate executives at a very young age, and they were always like, “You, really?” she said. “But I learned confidence from that and to not be afraid to talk to powerful people and ask them ques tions.”

“She’s a small … woman. She’s short. And sometimes that means it’s hard to impose yourself in a board room, to say, ‘Hey, my voice is worth listening to,’” Geman-Wollach said.

Segarra still had her heart set on radio, and after three years, she “in vested in buying (her) own recording equipment and just started pitching stories,” she said. She moved to Phil adelphia after landing a reporting job at WHYY, an NPR charter member.

After two and a half years at WHYY, Segarra moved to New York to work as a reporter for Marketplace, a radio program that focuses on busi ness and the economy. Starting with general assignments and features, she branched out into podcasting over her six years at the publication. Focus ing on consumer psychology, Segarra found a way to bring a personal side to her financial reporting — including a long-form piece about an unlikely nude model.

“I liked that I got to branch out into

the more emotional side of money,” she said.

At Brown, Segarra stopped study ing economics after the introductory class, instead focusing her course load on her interests in Shakespeare and political science.

“It would’ve been helpful to take more econ classes, but at the same time, I just was not going to do that,” she said.

But since then, Segarra has devel oped an understanding of finance and economics through her work. After fo cusing on corporate finance at CFO and government finance at WHYY, Segarra felt that learning about macroeconom ics at Marketplace was “completing the circle.”

“Over the past decade plus, I’ve almost gotten a degree in finance and business and economics because I’ve covered it from all these different an gles,” she said. “I wouldn’t say that any of these things are my great love … I just happened to learn a lot about it.”

Now, Segarra draws on this knowl edge of finance at “Life Kit.”

“I have this foundation where I can do money stories for ‘Life Kit,’ where I can talk about it really simply and break things down for people and help make their lives a little easier,” she said.

Since graduation, Segarra has re mained close with her friends from college despite the physical distance. Segarra now lives in New York, Ge

Segarra and Geman-Wollach “send each other voice notes on WhatsApp, which is kind of funny for two radio people to do,” Geman-Wollach said. “We have our own little non-live pod cast going.”

Similarly, Segarra has maintained her friendship with Rosengard. They FaceTimed almost daily at the start of the COVID-19 pandemic. She was the first person to visit Rosengard, who was stuck in Canada when border closures ended.

“She’s always been there to solve my crises,” Rosengard said.

Segarra’s friends praised her open ness and compassion.

“She came to visit me in London recently, and I brought her to dinner at one of my friend’s houses. She didn’t know anyone, but she came in there and charmed everyone,” Geman-Wol lach said. “I love that you can have a meaningful conversation with Mari elle, whether she’s your best friend of 15 years or whether you just met her that night.”

Segarra strives to maintain this au thenticity and openness in her work: In her first episode at “Life Kit,” she cov ered the nerves of starting a new job.

Geman-Wollach said that she couldn’t be prouder of her friend.

“She’s done it. She’s on the radio, hosting her own show,” she said. “Her voice is worth listening to.”

4 FRIDAY, OCTOBER 7, 2022THE BROWN DAILY HERALD | NEWS

man-Wollach in London and Rosengard in Chicago.

UNIVERSITY NEWS

Segarra, friends reflect on Segarra’s time at Brown, career path in radio

COURTESY OF ANTHONY SEGARRA

Marielle Segarra ’10 joined WBRU in college, later deciding to pursue radio as a career. “She’s done it. She’s on the radio, hosting her own show,” said Diana Geman-Wollach ’10, a friend Segarra made during her second year of college at Brown.

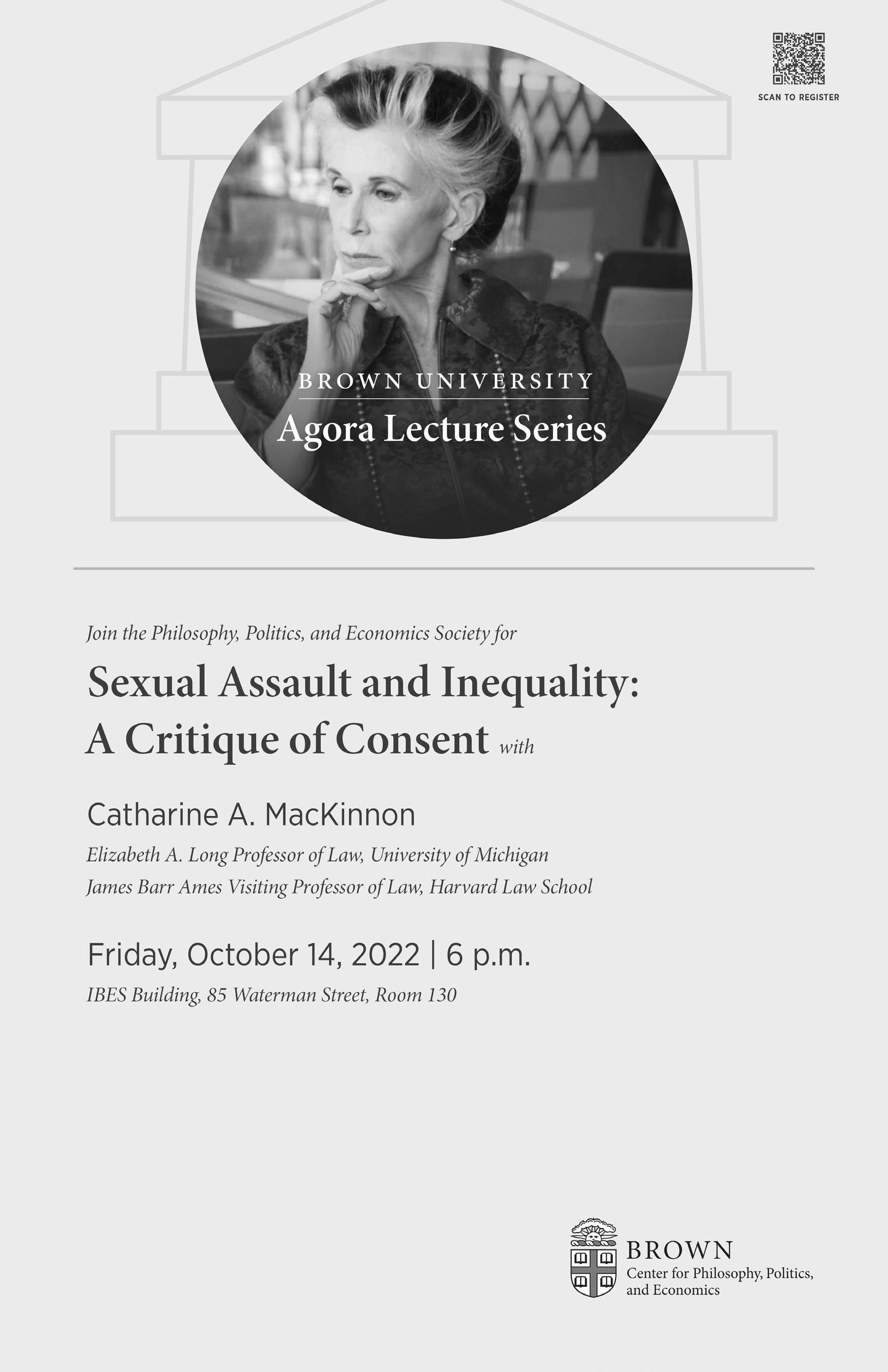

‘Democracy Now!’ host Amy Goodman speaks at Pembroke

BY EMMA GARDNER METRO EDITOR

BY EMMA GARDNER METRO EDITOR

“Climate and democracy are under enormous threat,” said Amy Goodman, host and executive producer of the progressive news program “Democracy Now!” at a Thursday evening event hosted by the Cogut Institute for the Humanities in Pembroke Hall. “Our ability to weather this storm depends on concerted action by the global ma jority who care — but against increas ingly difficult odds.”

These words are as good a summary as any for the themes presented in Goodman’s talk, entitled “Democracy in Crisis.” Despite the title, the event covered a broad range of topics includ ing environmental concerns, threats to democracy, the power of activism and the importance of independent news media. Despite the severity and daunt ing nature of modern crises, Goodman expressed confidence in the ability of average people to work together to ensure a democratic future.

Goodman began the talk with how “Democracy Now!” came to be, which she described as illustrative of the ways independent media threat en harmful power structures. The program began as a group of radio stations operated by Pacifica Radio, which was founded to produce news that was “not run by corporations that profit from war, but (by) journalists and artists,” Goodman said. She em phasized that “Democracy Now!” is also inspired by the same corpora tion-independent ethos.

In the 1970s, one of Pacifica’s sta tions in Houston was repeatedly blown up by a member of the Ku Klux Klan, Goodman said. These attacks and the far-right opposition that motivated them are emblematic of the power that independent media has to facilitate peace and understanding between people, Goodman said. The Klan “un derstood how dangerous independent media is, precisely because it allows people to speak for themselves,” she explained.

“When you hear someone speaking

from their own experiences, it chal lenges the stereotypes and the carica tures you have,” Goodman said. “You hear a Palestinian child, you hear an Israeli grandmother, you hear an uncle in Ukraine and in Moscow. … It makes it much less likely that you’ll want to destroy them, because you under stand where they’re coming from, and that understanding is the beginning of peace.”

Goodman’s talk also underscored her belief in the capacity of popular protest to change the world. She point ed to her coverage of protests against the brutal Indonesian occupation of East Timor, which lasted from 1975 to 1999. Goodman described the cruelty and terror of the occupation, including a harrowing massacre she reported on in Dili, the country’s capital.

Even the presence of American

journalists, which usually deters re gimes from acts of mass public vi olence, failed to stop the massacre, Goodman said. The coverage her team provided helped to spark a movement in America to stop the crisis, she added.

In the United States, Goodman said that the Brown community played a prominent role in the protests, advo cating for a ban on U.S. arms sales to Indonesia. Students at the University worked with then-Associate Dean of the College David Targan ’79, who now teaches physics, to convince former Republican Congressman Ron Macht ley (RI-1) to sponsor a successful bill to end the sales.

“Brown students called (congress people) as it passed from committee to committee,” Goodman said. For mer West Virginia Senator Robert Byrd “complained that he thinks he heard

from every student at Brown Univer sity,” she recalled.

Goodman also pointed to the 2016 Standing Rock protests of the Dakota Access Pipeline — which she also cov ered — as another example of the ways independent media can interface with protest movements to create change.

Although the pipeline was eventu ally built, Goodman said “Democracy Now!” and other news outlets were cru cial in spreading information about the protests. Goodman said that video she captured of one confrontation, which featured protesters blocking bulldoz ers in the face of violent repression from private security officers, helped to communicate the severity of the situation to the rest of the nation, in cluding then-President Barack Obama.

The video, she said, attracted main stream news attention, which was cru

cial to protecting protesters on the ground. Goodman, in addition to many Indigenous protesters, had warrants out for their arrest, but the ensuing spotlight prevented local authorities from cracking down on them.

Although Goodman acknowledged that grassroots activism and indepen dent media are not always a surefire fix to social injustices, she emphasized that they remain crucial in the fight for democracy and a healthy planet. Winning these fights “is painful to do,” she said, “but I think we can do it.”

“We are simply talking about the fate of the planet, which is why we have to join together and have a media that’s not afraid to provide a platform for people to speak for themselves, and to discuss and debate the most critical issues of the day,” Goodman said.

FRIDAY, OCTOBER 7, 2022 5THE BROWN DAILY HERALD | NEWS

UNIVERSITY NEWS Progressive media figure highlights importance of activism, independent news

ROCKY MATTOS-CANEDO / HERALD Host and executive producer of “Democracy Now!” Amy Goodman highlighted how Brown students played a role in enacting a bill to end U.S. arms sales to Indonesia during the East Timor occupation.

Endowment Fund to support “pro grams and projects at the JCB related to Spanish and Spanish American sub jects,” according to the JCB website.

Amor y Vázquez helped open the University to more Hispanic com munity members and provided “a privileged space for Latin American studies,” Vaquero said. “He was ahead of his time.”

A global upbringing

After his passing in 2018, Amor y Vázquez’s cousin Felisa VázquezAbad gave a presentation about his life during a memorial at the JCB. The presentation was shared with The Herald by Domingo Ledezma Ph.D. ’03, a mentee of Amor y Vázquez and contributor to the memorial.

Amor y Vázquez was born in 1921 in Galicia, Spain to María Do lores Vázquez Gayoso and José Amor Rodríguez. Rodríguez fought in the Spanish-American War in Cuba and was a “great admirer of the Rough Rid ers and Teddy Roosevelt,” according to the presentation. His father’s ad miration for the United States would influence Amor y Vázquez throughout his life.

Amor y Vázquez spent his child hood moving between Cuba, Venezu ela and Spain before finally settling in Havana during the Spanish Civil War in 1939. He pursued an under graduate degree at the Universidad de la Habana and graduated in 1944 with degrees in private and public law.

“He was a very interesting person and scholar,” Vaquero said. Amor y Vázquez “felt very close to the depart ment” because of his “admiration and dedication” to the University.

Bringing Latin American studies to Brown

According to Vaquero, Amor y Vázquez was experienced in Hispan ic studies due to his trans-Atlantic upbringing. “He was the first trans-At lantic” scholar at the University, she added. “Even though he studied the Iberian peninsula, he also studied Venezuelan and Cuban writers.”

Typically, Hispanic studies is di vided between the Iberian Peninsula and Latin America, explained Chair of Hispanic Studies Laura Bass — but Amor y Vázquez bridged that gap, en couraging students to study both re gions and place them in conversation.

Amor y Vázquez’s students “liked the idea of (him) giving the same im

portance to Latin American studies as peninsular studies,” Vaquero said.

Amor y Vázquez was a “champion of Latin American studies” and served as the first director of the University’s Latin American Studies Program in 1983, Hunt explained.

The program’s creation led the University to host the Eighth Con gress of the Associación Internacional de Hispanistas — an international, non-profit organization that promotes the study of Hispanic languages and literatures.

LASP later joined academic net works such as the Latin American Studies Association, the New England Council on Latin American Studies and the Consortium of Latin Amer ican Studies Programs, according to Katherine Goldman, center manager at CLACS. A year after Amor y Vázquez became director of LASP, he expanded the program into CLACS in 1984.

He “realized that there was an empty space (at) Brown for Latin American studies,” Vaquero said. “He felt that there should be a place that put people together in all different departments.”

‘Long-term supporter’ of John Car ter Brown Library

Amor y Vázquez was also known for his work with JCB, which is one of the most important libraries for Latin American colonial documents in the country, according to Vaquero.

During his professorship, Amor y Vázquez served on the JCB Board of Governors and was chair of the academic advisory committee, wrote Maureen O’Donnell, former secre tary at the library, in an email to The Herald.

In this role, Amor y Vázquez often encouraged his students to turn to the JCB for resources. Many, includ ing Ledezma, ended up writing their dissertations on books found at the library.

In 2003, Amor y Vázquez received a medal from the library for his ser vice as “an advisor, author, editor,

translator and long-term supporter of the library,” Hunt wrote. A year later, he established the José Amor y Vázquez Endowment Fund at the JCB, which allowed more Hispanic studies graduate students to gain access to grants through the JCB, Vaquero said.

According to Ledezma, Amor y Vázquez cared for the library long after his retirement. Any time Ledez ma would come to the University’s campus, Amor y Vázquez would re mind him “to look after the library.”

‘A treasure of a person’ Amor y Vázquez’s impact extends well beyond College Hill. He was “a real mover and shaker” in Hispanic studies across the globe, Vaquero said.

Amor y Vázquez was a correspon dent of the Royal Spanish Language Academy, served on the board of the Associación Internacional de His panistas, was an honorary member of the North American Academy of

the Spanish Language and received an honor from the Spanish king, ac cording to Bass.

“He is recognized as one of the most important Hispanicsts of our time,” Vázquez-Abad said in her pre sentation. Beyond his professional work, Amor y Vázquez is best remem bered by those close to him for his “sharp” wit and humor, Vaquero said.

“I miss him and when I see Do mingo that’s what we talk about — how we miss Pepe,” she added. “He was very dear; … somebody within the institution that protected you.”

“Pepe was a treasure owf a per son — warm, kind, brilliant, very funny and deeply compassionate,” O’Donnell wrote. “He had a kind of soul magic — a nearly visible sparkle — that he shared with everyone he came into contact with. He encour aged and enlivened others but was also always realistic and grounded in his guidance. He was a gift to all who knew him.”

arate from official circuits of politics,” said Associate Professor of Comparative Literature and Hispanic Studies Michelle Clayton, who focuses primarily on the literature from this period.

Conversations around the world

In writing, Borges was often con cerned with how Argentine writers relate to the world, Clayton said. In his lecture “The Argentine Writer and Tradition,” Borges famously dismissed the idea that Argentine literature should be confined to “Argentine traits and Argentine local color,” instead believing that “the writer is in conversation with all times and with all spaces,” Clayton explained.

More contemporary Latin Ameri can writers have similar considerations about “what writing could do to process the history of their country, the histo ry of the continent, the region more broadly, and the history of a relationship to Europe and to the world,” Clayton said.

Latin America is a broad region, and conversations about Latin America as a singular entity can overlook regional diversity in literary tradition. Columbi an literature is informed by its unique geographic position in the continent — for example, it has connections to the Caribbean, the Andes and the Pa cific Coast as well as the Amazon, said Martínez-Pinzón, whose work research focuses on Columbia.

It would be similarly reductive to separate Latin America from global liter ary influences, Clayton said. “Sometimes the relationship with the world was a kind of insistence on the freedom to imi tate or engage in conversation with writ ing that was coming from elsewhere.”

The 1950s and 60s saw the Latin American Boom, “where writers were experimenting with new forms to tell the histories of their country, to explore political issues, concerns, crises that are taking place within their national boundaries,” Clayton said, “but often involving a broader world and showing the entanglement of their local spaces

with the planetary, with the global.”

Latin American literature is often associated with magical realism, and magical realism is primarily associated with Latin America. But although the narrative tradition was widely popular ized by García Márquez, in some ways it roots from a critique of European surrealism, Clayton explained. One of the earliest writers of magic realism is the Cuban author Alejo Carpentier, who said that “in Europe the surrealist view which tries to defamiliarize and re-en chant the world is artificially produced, whereas in Latin America it’s natural,” she added.

Beyond western reality

Magical realism is a narrative tradi tion that “blurs the boundaries between the real and the not so real, and less in a fantastic way than in a very sort of seamless, naturalized way,” Whitfield said.

“It becomes a way of thinking about Latin American perception that is less driven by European rationalism than

it is by something different on its own terms,” she added. It also took on dif ferent variations in other parts of the world that were in a “similar, post-co lonial position,” she said.

The tradition has been widely con tested and “seen as a way to not take Latin American history seriously,” Martínez-Pinzón said.

But magical realism has also been adapted into ways in which the na tion-state can define itself, he add ed. Magical realist writers like García Márquez call into question what reality is, Martínez-Pinzón said, and where it is defined from. The Latin American reality that García Márquez depicts in his novels is no less real than a western reality, but it needs to be “analyzed” from Latin America, not from Europe, he added.

García Márquez famously asserted this himself: “it always amuses me that the biggest praise for my work comes for the imagination, while the truth is that there’s not a single line in all my work that does not have a basis in reality,” he wrote.

Broadening the canon

Latin American literature continues to grow and evolve as a body of work, and in recent years, this has been facilitated by a “much greater openness in trans lation,” Clayton said, “much more Latin American literature is getting translated now, much more quickly.” Translators and publishing houses like Coffee House Press are dedicating themselves to the question of translation and are making space for Latin American literature with in that, she added.

“The translations are not just excel lent but very often accompanied by a re flection by the translator on the way that translation can bring works to a different audience,” she said. Clayton also cited an increase in student interest in ethical questions surrounding translation.

Reading literature helps us under stand humanity at a different level, Whitfield said, and bringing that per spective into Hispanic Heritage month offers another way of thinking about these experiences.

FRIDAY, OCTOBER 7, 2022THE BROWN DAILY HERALD | NEWS6

PROFESSOR FROM PAGE 1

COURTESY OF DOMINGO LEDEZMA

José Amor y Vazquez established an endowment fund in 2004, which helped more Hispanic graduate studies gain access to grants.

COURTESY OF DOMINGO LEDEZMA

While Amor y Vazquez had an academic impact at Brown and beyond, his colleagues best remember him for his “sharp” wit and humor.

LITERATURE FROM PAGE 1

How Rhode Islanders are celebrating Hispanic Heritage Month

Organizations, businesses celebrate diversity of RI Latinx community

BY JULIA VAZ SENIOR STAFF WRITER

From Sept. 15 to Oct. 15, the Unit ed States commemorates Hispanic Heritage Month. In Rhode Island, the Latinx community is rapidly growing, having increased 40% in the last decade, per the US Census Bureau’s 2021 census. To celebrate a vibrant and diverse community, local governments, businesses and organizations have come up with different ways to uplift traditions and cultures.

In Pawtucket, the city govern ment has established the first Latino Art Exhibition. The “Latino Roots Art Exhibit” is on view from Sept. 12 until Nov. 30, featuring the works of local artists such as Evans Molina–Fernandez and Carlos Ochoa.

According to Diana Figueroa, se nior planner for the Pawtucket Plan ning & Redevelopment Department, the initiative seeks to promote and foster relationships with artists from different Latinx backgrounds. “It is important that we have this gallery

here and through the art, support the cultural exchange between visitors and artists,” she said.

The city of Pawtucket has also partnered with the Rhode Island His panic Chamber of Commerce to orga nize support tours of Latino-owned businesses. The program, Figueroa said, “is designed to provide Paw tucket’s small businesses with the resources that they need and cele brate entrepreneurship.” The next tour will take place at 10 a.m. on Oct. 12 on Main Street downtown.

Progreso Latino, a non-profit or ganization serving the Rhode Island Latino community since 1977, is cel ebrating its 45th anniversary on Oct. 21 with a gala. According to Claudia Cordon, co-director of education, the event will highlight their educational work, especially their adult learning initiatives.

Progreso Latino will award stu dents and teachers for their hard work in transitioning to virtual learning during the COVID-19 pan demic. The event will also feature Michael Grey, the governor’s work force board chairman, as a keynote speaker.

The organization is also high lighting its “services for a lifetime” approach, according to Cordon. From providing early childhood education to senior mentorship, Progreso Lati no covers all the stages of life. On

Oct. 14, the seniors in the organi zation will host an open house that will begin at 10 a.m. and is open to the public. The space will feature dedicated sections for different Latin American countries, and people are encouraged to add items that rep resent their cultures, Cordon said.

According to Cordon, Progreso Latino’s mission is to help the com munity “achieve greater self-suf ficiency and social-economical progress,” she said. Currently, the organization has focused on facing a “post-COVID world,” said Cordon.

For her, the pandemic exacerbated the immediacy of issues that have long faced the community. “A lot of it has to do with connecting (people) to well paying jobs, sustainable jobs … and that we acknowledge the exper tise of foreign trained professionals,” Cordon said.

Ediz Monzon hopes to celebrate Hispanic Heritage Month as his fam ily’s coffee truck Cafe Modesto — “Humble Coffee” — completes its two year anniversary. Monzon recount ed the months spent in Guatemala learning about coffee. “We fell in love with coffee and then when we came back, during the pandemic,” he said. “My wife and I built the truck together,” he said.

The business provides imported Guatemalan coffee to the Rhode Is land community. “We know exactly

In Rhode Island, the Latinx community is rapidly growing, having increased 40% in the last decade.

where our coffee is coming from,” said Monzon. Modesto is capable of supporting “the social and econom ic development of the women and small communities of Guatemala” by responsibly choosing the beans and grounders, according to the busi ness’s Facebook page.

According to Monzon, the expe rience of drinking authentic Lati no coffee builds relationships and fosters a “home away from home.” He said that their idea “is to bring people together and create a little community. We get to know more people, no matter where they come

from.” He added that Brown students are often regulars at his truck, which is often parked near the pedestrian bridge. “The international students really like it,” Monzon said.

In Rhode Island, Hispanic Her itage Month can be celebrated as diversely as the identities within the Latinx community. The month is “a celebration of our common her itage, but also acknowledging our diversity because there are twenty Spanish-speaking countries in Lat in America,” Cordon said. “We are uniting … but we each have our own identity.”

Latin American students yearn for bigger on-campus community

Students say needblind admissions would expand Latin American campus community

BY ALEX NADIRASHVILI UNIVERSITY NEWS EDITOR

When Nicaraguan Independence Day rolled around on Sept. 15, Anasta sio Ortiz ’25 was at a loss over how to celebrate the holiday that had meant so much to him back home in Nicaragua. Though he did not know any fellow Nicaraguans on campus, he wanted to do something in com memoration. So Ortiz invited his friends to his room to listen to some traditional Nicaraguan music, and the night became an opportunity for him to share his culture with his peers.

“It’s the little things like this that allow me to celebrate my country and … share my culture,” Ortiz said. “Brown is a very inclusive place. … People understand cultural differ ences and are very excited to hear about other experiences.”

About 14% of the class of 2026 are international citizens, Dean of Admissions Logan Powell wrote in an email to The Herald, with more than a dozen Latin American countries represented. In honor of Hispanic Heritage Month, The Herald spoke with three Hispanic students at Brown about the communities they have found at Brown and the obsta cles they believe stand in the way of a greater Latin American presence on campus.

Anahis Luna ’25, who is from San Miguel de Allende, a tourist town in

central Mexico, feels there is a great sense of pride among the Hispanic and Hispanic American community on campus, with students always willing to “share in each other’s cus toms.” Just last week, Luna attended an event hosted by the Latinx Stu dent Union that brought together several on-campus organizations for a night of “food, dancing and mingling.”

At the same time, Luna — who said she cannot name more than 10 Latin American international stu dents on campus — feels a sense of disconnect between her experienc es and those of second-generation Hispanic students on campus, she explained.

“I definitely wish that there were a lot more internationals from Lat in America,” she said. “It’s really hard to discuss certain things be cause growing up in Mexico is just so different from the United States — there’s always that very small barrier.”

Ana Pereyra Caba ’24, originally from the Dominican Republic, felt similarly. “I have a lot of Hispanic friends — I even know a bunch of Dominicans — but none of them are internationals,” Pereyra Caba said.

“I’m grateful for these friends, but it’s not quite the same. I was born and raised in the Dominican Repub lic, and there are a lot of experiences that come with growing up in devel

oping countries that I wish I could relate (to) with someone.”

For Ortiz, the Global Brown Cen ter proved to be a useful resource in connecting him with new interna tional students, but very few have been from Latin America. “It’s very hard to create a community when you don’t hear about (the) number” of Latin Americans on campus, Or tiz said.

Ortiz added that he believes the University’s current need-aware international admission policy is a major barrier for Latin American international students to apply to Brown. He decided not to apply for financial aid as a way to prioritize his chances of getting accepted.

“We internationals are only go ing to apply where we have the best chance of getting in and being able to go, and only certain schools are need-blind,” Ortiz said. “If Brown isn’t one of them, international stu dents are not going to look (because they) know they’re at a disadvan tage.”

Luna said she took a risk during her application process by applying for financial aid, which in itself is a more “stressful” and “compli cated” addition to the process. “If I wasn’t accepted, I would have known that financial aid probably played a huge factor,” she said. “That’s kind of something you go in knowing.”

Need-aware admissions also create a discrepancy in the types of international students that are accepted to the University and the countries they come from, Luna said. Many of the international students from Latin American coun tries at Brown tend to be wealthier,

which does not account for the po tential applicants who come from “more unfortunate circumstances,” she said. “There’s a lot missing from Brown.”

“Wealthier countries can more directly feed into the United States” education system, Luna said. “Brown needs to be more cogni zant of … the different barriers that can keep students from applying to schools like this … and build more specific connections within different countries in Latin Amer ica itself.”

The University recently an nounced its plans to become fully need-blind for international stu dents beginning with the class of 2029, The Herald previously re ported. Powell hopes that, as a re sult, the University will see a sharp increase in international students from “a broader range of socioeco nomic backgrounds” in the coming years, he wrote.

“It is hard to overstate the im portance of this shift as a means of better reflecting the socioeconom ic diversity of our Latin American students and of our students from around the world,” he wrote.

Pereyra Caba remembers crying when she learned the news of Brown going need-blind in the coming years, and she hopes this is just the first step in the University more actively recruiting applicants from Latin American countries.

This initiative “opens up the opportunity for a lot of applicants from many different backgrounds,” Luna said. “Being need-blind … lev els the playing field (so) that you feel like you actually have a chance at college.”

FRIDAY, OCTOBER 7, 2022 7THE BROWN DAILY HERALD | NEWS

METRO

COURTESY OF CLAUDIA CORDON

UNIVERSITY NEWS

RHEA RASQUINHA / HERALD

Gaber ’23: Academic gatekeeping is not the answer

When I was beginning to make my college application list just over four years ago, I had never considered the possibility of go ing to an Ivy League school. Though my ac ademics and extracurriculars certainly qual ified me to apply to highly selective col leges, I lacked the confidence to pursue ad mission to one of America’s oldest and most prestigious schools. However, my cousin — a Brown alum — pitched the University as a great school for me, especially because it was a non-competitive environment. With her encouraging attitude and my highstrung determination, I decided to try my luck despite my hesitation. Four years later, I am thankful for that turn of events. I am very grateful to have attended Brown. It has been all that my cousin described, partic ularly with respect to the non-competitive attitude of Brown’s student body.

However, attitudes present in Brown’s faculty and administration — such as that put forth in Professor Roberto Serrano’s Sept. 14 op-ed — aim to reconstruct the ethos of the institution that I have come to know and love. Serrano claims that “Brown’s grading system and advising cul ture are suppressing student achievement.” This outlook is problematic and harmful to Brown’s student body. It is rooted in the commodification of student achievement, the encouragement of cut-throat competi tion and the facilitation of academic gate keeping.

The point that first struck me in Serra no’s op-ed was his erroneous claim that stu dents abuse the no credit grading system, sometimes with the help and encourage ment of advisors, by purposefully failing a course instead of receiving a C. Speculation about students’ abuse of the Brown grad ing system contradicts the philosophy upon which the system is based. In 1969, students protested for and won the ability to exert more agency over their education by im plementing an Open Curriculum and S/NC grading system. They organized around the idea that, as the Open Curriculum’s prin ciples state, “the student, ultimately re sponsible for his or her own development … must be an active participant in framing his or her own education.”

Therefore, from 1969 onward, a Brown education has centered on the belief that students can be trusted to shepherd their own education to best suit their intellectual and personal growth. With all due respect to Serrano, I find the insinuation that Brown students are conniving enough to put in the effort to intentionally fail a class in order to improve their GPAs to be a deeply insulting

versity or department norms.” To his point, I ask a very simple question: Why? In the wake of the pandemic, students are facing increasing mental health challenges, which manifest disproportionately in women and ethnic minorities. Selectively handing out As and encouraging student competition for good grades only adds to this stress and ex acerbates inequality. Furthermore, the need

plored before. Barring students from enter ing difficult fields because they lack expe rience in them is a privileged stance that discourages students from less resourced academic backgrounds from pursuing their interests. This practice of gatekeeping is also prominent in STEM fields, which wom en have historically struggled to enter. Ser rano asserts that more advisors need to steer students away from areas where they may not necessarily excel, but this is ex actly what my first-year advisor did to me. I told her that I wanted to pursue a math class in addition to my humanities-heavy course load, and she advised against it. To this day, it is one of the great regrets of my college career that I listened to her and did not pursue my interest in mathematics at Brown despite not having a particularly im pressive STEM background.

one. The notion that advisors would actual ly encourage students to take this approach is equally absurd.

Serrano also argues that the fact that failing grades do not appear on Brown stu dent transcripts is “misleading” to future employers and graduate programs. I can understand the point of view that a grad uate program would want to know if a stu dent has been able to keep pace with their coursework. Ultimately, however, does it matter more whether a student succeeded on their first attempt at a new subject, or that they eventually mastered the material and completed the required coursework for their future career or education? Especially in the case of employers, the specific class es a student took at Brown is often a lesser consideration than skill qualifications and past job experience.

Additionally, Serrano brings in a wider discussion on the negatively-connoted phe nomenon of grade inflation. Serrano argues in favor of leveling out grading curves to combat what he describes as areas in which a “disproportionate percentage of students are graded with As when compared with the Uni

to crack down on a high number of As relies on the assumption that most Brown students aren’t hardworking. If you go here, you’re probably academically motivated beyond the need to compete with your peers for a covet ed spot at the far right of a bell curve. I find the assertion that “student performances in some key concentration classes deflate” with grade inflation to be shockingly out of touch with the broader context of the Brown stu dent body.

Along with all these concerns, what I found most troubling about Serrano’s op-ed was his belief that “advisors should encour age students to choose a concentration not only about which they are passionate, but also in which they can excel.” In my opin ion, this is blatant academic gatekeeping. We shouldn’t be discouraging students from entering fields that are new and perhaps difficult for them. After all, that is the ex act opposite of the Open Curriculum’s mis sion. Furthermore, since Brown students come from a variety of academic back grounds with different resources, it is unfair to quickly judge our aptitudes for academic fields that some of us may never have ex

In my time at Brown, I have been able to grow into myself and out of my imposter syndrome in spite of attitudes such as those put forth in Serrano’s op-ed. In my expe rience, Brown has lived up to the picture painted by my cousin of an academically rigorous yet non-competitive environment. Furthermore, everyone that I have met on this campus is deeply concerned not only with their futures and academic goals, but also with their personal enrichment and fulfillment. After all, the Open Curriculum’s principles begin as follows: “At Brown Uni versity, the purpose of education for the undergraduate is to foster the intellectual and personal growth of the individual stu dent.” I only hope that this continues to be the purpose of education at Brown, and that this institution does not lose sight of its most profound legacy: a unique and ef fective emphasis on the process of learning itself.

Yasmeen Gaber ’23 can be reached at yas meen_gaber@brown.edu. Please send re sponses to this opinion to letters@brown dailyherald.com and other op-eds to opin ions@browndailyherald.com.

The Herald does not publish anonymous submissions. If you feel your circumstances prevent you from submitting an op-ed or letter with your name, please email herald@ browndailyherald.com to explain your situation.

You can submit op-eds to opinions@browndailyherald.com and letters to letters@browndailyherald. com. When you email your submission, please include (1) your full name, (2) an evening or mobile phone number in case your submission is chosen for publication and

any

with Brown University or any institution or

your

the

8 FRIDAY, OCTOBER 7, 2022THE BROWN DAILY HERALD | COMMENTARY The Brown Daily Herald, Inc. is a financially independent, nonprofit media organization bringing you The Brown Daily Herald and Post- Magazine. The Brown Daily Herald has served the Brown University community daily since 1891. It is published Monday through Friday during the academic year, excluding vacations, once during Commencement and once during Orientation by The Brown Daily Herald, Inc. Single copy free for each member of the community. Subscription prices: $200 one year daily, $100 one semester daily. Copyright 2022 by The Brown Daily Herald, Inc. All rights reserved. Submissions: The Brown Daily Herald publishes submissions in the form of op-eds and letters to the editor. Op-eds are typically between 750 and 1000 words, though we will consider submissions between 500 and 1200 words. Letters to the editor should be around 250 words. While letters to the editor respond to an article or column that has appeared in The Herald, op-eds usually prompt new discussions on campus or frame new arguments about current discourse. All submissions to The Herald cannot have been previously published elsewhere (in print or online — including personal blogs and social media), and they must be exclusive to The Herald. Submissions must include no more than two individual authors. If there are more than two original authors, The Herald can acknowledge the authors in a statement at the end of the letter or oped, but the byline can only include up to two names. The Herald will not publish submissions authored by groups.

(3)

affiliation

organization relevant to

content of

submission. Please send in submissions at least 24 hours in advance of your desired publication date. The Herald only publishes submissions while it is in print. The Herald reserves the right to edit all submissions. If your piece is considered for publication, an editor will contact you to discuss potential changes to your submission. Commentary: The editorial is the majority opinion of the editorial page board of The Brown Daily Herald. The editorial viewpoint does not necessarily reflect the views of The Brown Daily Herald, Inc. Columns, letters and comics reflect the opinions of their authors only. Corrections: The Brown Daily Herald is committed to providing the Brown University community with the most accurate information possible. Corrections may be submitted up to seven calendar days after publication. Periodicals postage paid at Providence, R.I. Postmaster: Please send corrections to P.O. Box 2538, Providence, RI 02906. Advertising: The Brown Daily Herald, Inc. reserves the right to accept or decline any advertisement at its discretion. 88 Benevolent, Providence, RI (401) 351-3372 www.browndailyherald.com Editorial: herald@browndailyherald.com Advertising: advertising@browndailyherald.com THE BROWN DAILY HERALD SINCE 1891 @the_herald facebook.com/browndailyherald @browndailyherald @browndailyherald 132nd Editorial Board Editor-in-Chief Ben Glickman Managing Editors Benjamin Pollard Caelyn Pender Senior Editors Katie Chen Gaya Gupta Jack Walker post-magazine Editor-in-Chief Kyoko Leaman News Metro Editors Emma Gardner Ashley Guo Oliver Kneen Katy Pickens Sameer Sinha Science & Research Editors Kathleen Meininger Gabriella Vulakh Arts & Culture Editors Rebecca Carcieri Laura David Aalia Jagwani Sports Editor Peter Swope University News Editors Emily Faulhaber Will Kubzansky Caleb Lazar Alex Nadirashvili Stella Olken-Hunt Shilpa Sajja Kaitlyn Torres Digital News Director of Technology Jed Fox Opinions Editorial Page Board Editor Johnny Ren Head Opinions Editor Augustus Bayard Opinions Editor Anika Bahl Bliss Han Melissa Liu Jackson McGough Alissa Simon Multimedia Illustration Chief Ashley Choi Photo Chiefs Danielle Emerson Julia Grossman Photo Editors Elsa Choi-Hausman Roslyn Coriz Rocky Mattos-Canedo Dana Richie Social Media Chief Alejandro Ingkavet Social Media Editor Sahil Balani Production Copy Desk Chief Lily Lustig Assistant Copy Desk Chief Brendan McMahon Design Chief Raphael Li Design Editors Sirine Benali Julia Grossman Gray Martens Neil Mehta Business General Managers Alexandra Cerda Sophie Silverman Sales Directors Joe Belfield Amit Levi Finance Director Andrew Willwerth

“I only hope that … this institution does not lose sight of its most profound legacy: a unique and effective emphasis on the process of learning itself.”

As I reflect on my first year at Brown as senior associate dean and senior director of residential life, including the changes I have been able to enact, I am comfort ed by the community I have been able to create — for myself, for my family, for my team and for students at Brown. In September 2021, My acceptance of this of fer was deeply rooted in Campus Life’s commitment to the student experience by providing resources to increase our staffing model, re design the student leadership role and encourage the development of new residential facilities. I joined a newly-restructured team at the Office of Residential Life, bursting with an energy similar to first-day-of-school jitters. I’ve had the honor of serving in a va riety of roles at colleges and uni versities across the country, but my excitement was heightened as I stepped into my office in Gradu ate Center E for the first time. As I turned the key, I knew I was at the start of an experience like no oth er. I was offered this role to make a significant and lasting change in the lives of the students at Brown, reshaping their residential experience. This mission sounds daunting — and felt that way for a while — but this year has proven to be one of the most rewarding I’ve had as a student affairs prac titioner.

Whenever you begin a new job, you should be prepared for a few challenges, as my experience has demonstrated. In one year, I have experienced events of bibli cal proportions — feast (success fully filling critical staff vacan cies), flood (students displaced by water in Andrews Hall and Ar chibald-Bronson) and famine (a challenging spring housing selec tion). I was afforded the opportu nity to support Brown’s commit ment to creating a home (away from home) for our Afghan schol

ars. I believe that my best learning happens when I am met with chal lenges, ones that test my patience, stretch my skill set and force me to sit with a problem until I find a solution. This past year has been a humbling one. I wanted to come in and change Brown, but now re alize that Brown has changed me — for the better.

I am more patient, commu nicative, pensive and collabora tive — and I remain genuinely committed to enhancing the res idential student experience at Brown. Most folx may experience a life-changing event only once in a given year, or not at all. Last year, I moved my family from west to east, started a new job and cel ebrated my 50th birthday — which comes with its own set of quiet, reflective moments. This year has taught me to be gentler with my self and to remember that Rome was not built in a day. I came here with lots of ideas to reshape and reimagine the work we do in ResLife. My quiet and humbling reflections since have resulted in exciting initiatives and opportu nities that I truly believe will im prove the overall student experi ence at Brown.

My vision is simple — create a residential experience for stu dents that is welcoming, support ive, and engaging. I want stu dents to make Brown their home away from home. With my team in ResLife, I want to create op portunities for students to feel connected to this campus in ways that invoke a deeper sense of be longing in a community that feels comforting and familiar, like a family. It’s the dawn of the Ice Age. Are you ready?

Dean Brenda Ice Senior Associate Dean and Senior Director of Residential Life

EDITORIAL

Let them stay

According to its website, the Brown Universi ty Graduate School “is committed to fostering a welcoming and inclusive academic community.” But this fall, as three graduate students — Jere miah Zablon GS, Clew GS, and Karina Santam aria GS — faced removal from their programs, that commitment to inclusion was nowhere to be seen.

Instead, the stories of these three students re veal a Graduate School callous to the struggles of its students.

Due to economic hardship in his home country Kenya, Zablon could no longer afford the tuition for his master’s program. According to a Go FundMe page Zablon created for tuition assis tance, all of his loan applications, including one to the University itself, were denied. Fortunately, Zablon was able to scrape together the necessary funds to enroll in classes and avoid losing his student visa.

The fact that Zablon was forced to turn to Go FundMe at all is concerning. Crowdfunding is no replacement for institutional support. Zablon told The Herald, “It took me five years to save what I used (for tuition) in the past semester.” He clearly values a Brown education — but does the institution value him back? When he needed help, the University’s support systems were in sufficient.

Clew and Santamaria continue to face removal from their programs.

Earlier this year, Clew found out that their sis ter was diagnosed with cancer and applied for family leave to care for her. But their application was denied. University administrators cited the Graduate School’s family leave policy, which al lows students to take leave to care for a “spouse, domestic partner, child or parent” — but not a sibling. This policy is clearly flawed, arbitrarily designating certain relationships as worthy of care but not others. The University should up date its leave policy, and in the meantime, grant Clew the leave they require. Clew should not be forced to give up their education for their family, or give up their family for their education.

Battling an array of personal stressors in 2019, Santamaria missed a deadline for her disserta tion revisions by three days. She was terminated from her program, and though she was reinstat ed after an appeal, the Graduate School never gave her a real second chance. Santamaria lost funding for her research, impeding crucial data collection. After her program abruptly revoked a teaching assistant position it had offered her, she was forced to find outside work as a ride share driver and grant writer in order to support her research and living costs. The University set her up for failure.

True inclusion requires flexibility and empathy. As Santamaria herself stated, “I came here as a low-income, first-generation, 45-year-old stu dent. … There’s a lot of recruitment of diversity, … but there’s not enough of a plan to deal with what comes with that diversity. The answer can not just be, ‘Get out.’”

The Graduate School’s treatment of Zablon, Clew and Santamaria is a troubling indication of the University’s broader lack of support for graduate students. Over the years, graduate student com plaints — ranging from funding to housing to childcare — have been varied and far-reaching, and are in many ways, still unanswered.

The University has not released a statement ex plaining each student’s case, in accordance with federal law prohibiting disclosures about stu dents’ academic or financial circumstances.

We are not asking for comment; we are asking for action. We are asking the University to let Clew and Santamaria stay. We are asking the University to improve support for graduate stu dents. They deserve better.

Editorials are written by The Herald’s Editori al Page Board. This editorial was written by its editor Johnny Ren ’23 and members Irene Chou ’23, Caroline Nash ’22.5, Augustus Bayard ’24, Devan Paul ’24 and Kate Waisel ’24.

TODAY’S EVENTS

of 2023 Honors Visual Art

Probability Seminar

A Call for Human-Centered AI

p.m.

Center for Information Technology, Room

SoBear Tote Bag Decorating!

p.m.

TOMORROW’S EVENTS

Men’s Water Polo vs.

Zines and

Field Hockey vs Columbia

Family Field

Harry Potter Trivia Night!

and Holley,

FRIDAY, OCTOBER 7, 2022 9THE BROWN DAILY HERALD | COMMENTARY CALENDAR

Class

Concentrators Exhibition 8 a.m. to 8 p.m. List Art Building

12

Watson

368

Presents Van Vu 11:30 a.m. 182 George Street, Room 110

7

The Underground

Harvard 10 a.m. Coleman Aquatics Center

1 p.m. Goldberger

DIY

Brunch! 1 p.m. Sarah Doyle Center

8 p.m. Barus

Room 155 OCTOBER SFThWTuMS 9 87 10 4 5 6 16 1514 17 12 1311 23 2221 24 19 2018 2725 26 2 3 1 28 29 28 29 Reflections on one year leading ResLife LETTER TO THE EDITOR To the Editor:

post-

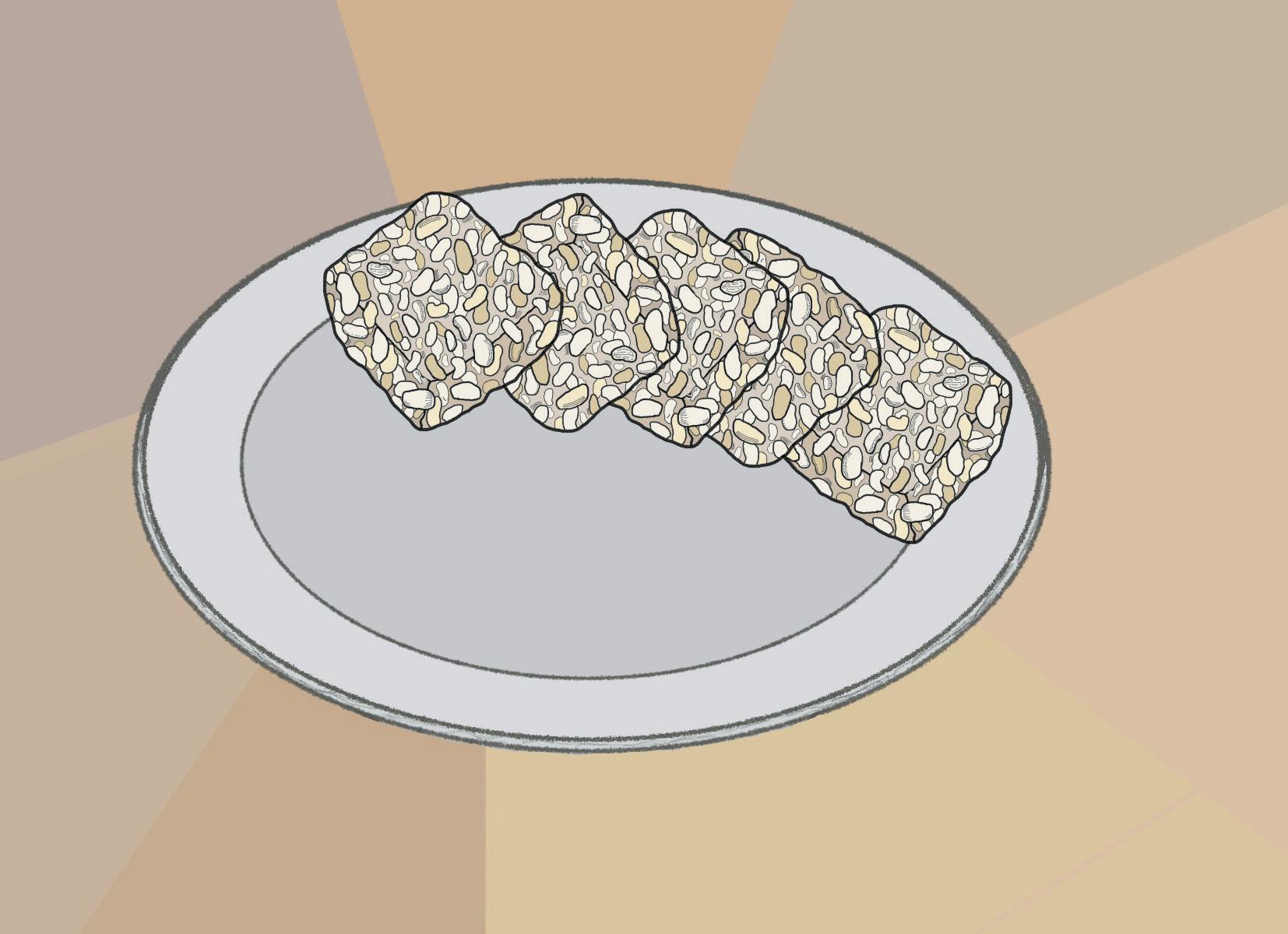

in defense of tempeh

an indonesian’s attempt to quell the slander

by Audrey Wijono insta: @audreybellie illustrated by Emily Saxl

Ratty tempeh is a mortal sin, an unspeakable around these parts; its reputation precedes it. To partake in its horrors is to renounce the very core of one’s humanity, to shirk one’s honor and pride— and God forbid you claim to enjoy it. Brain-like in texture and appearance, the soy-based product is the bane of every trypophobe’s existence. Despite the Ratty’s many attempts to dress it up and rebrand its soiled image, tempeh dishes inevitably fall flat. An undignified, formless mush, tempeh in every form remains an afterthought in the face of the Ratty’s many culinary triumphs: Fried plantains. Vodka pasta. Pork schnitzel. Barbeque brisket.

I’d heard the horror stories even before I’d reached Brown, somewhere in that anxiety-riddled summer preceding the start of college. From my little bedroom in Jakarta, Indonesia, I’d watched as my peers took to social media to bombard the upperclassmen with questions. Any advice for first-years? someone would inevitably ask. The replies were generally the same cookie-cutter answers given to every incoming freshman. Take CS15 before Andy leaves. No 9 a.m. class is worth it. Wear your shower shoes. One reply, though, was a constant, crucial word of caution:

Don’t touch the Ratty tempeh!

Of the many pieces of advice we’d been given, the tempeh comment stuck out the most. Maybe it was the sheer absurdity of it: no other dish at Brown had garnered so much as a mention, let alone a warning. Hell, I’d barely even learned the name of the dining halls by that point. Yet this thought about a familiar Indonesian staple settled in the back of my mind, determined to make its mark.

After a long pre-orientation with nothing but the V-Dub to tide us over, the Ratty opened on the first day of classes. Entering that venerated hall for the first time was momentous. Surrounded by my brand-new clique of pre-orientation friends, I marched in with the confidence of a fresh high school graduate, taking in the sights. The salad bar! The drink machines! Coffee milk! An overwhelming level of choice lay before our very eyes. Amidst our obnoxious chatter and rather misplaced enthusiasm, we grabbed our take-out boxes and shuffled, one by one, toward the food. Most of the dishes that day were, unsurprisingly, nothing to write home about. But there was one that stood out among the rest, one that stopped me in my tracks and left me gawking ...

Your first therapist is for a speech delay. She feeds you sentences and you regurgitate them back to her. She makes you drop pennies into a mason jar. She teaches you animal sounds, fills the house with oink and moo. After a few months, she leaves, and your voice stays.

But once you learn to name things, you will also learn to fear the unnamed things. Only when you learn the word horizon did it become unreachable. Only when you learn the word love does it begin to tighten like a noose. You watch the sun sink into the sea—the sky becomes a bloody cut—and you hate knowing how small you are. Your house in the mouth of the volcano, long extinct.

From here, you can see everything: the sand dunes rising from the skin of the earth like vertebrae, the crescent of foam where the water meets the land, the calm breaths of the ocean. Your fingers are wrinkled, rubbed raw from climbing the rocks ...

ice cream wisdom

a scooper’s study

by Olivia Cohen

I came into work for my typical Thursday evening shift at High Point Creamery to find my coworker, Ashley, in tears. I didn't know her very well—only that she was in her late twenties, assistant manager of the shop, and that she was married to another one of my other coworkers, Sam. They lived together in Ashley's mother's condo: it's tough to pay rent in Denver on two ice cream scooper salaries, that's for sure. I stood awkwardly by the cash register, unsure what to do as I watched Ashley stack sugar cones into a pointed tower, tears rolling into her mask. As much as I wanted to grant her some discretion, I could no longer pretend I hadn't noticed. "Is everything okay?"

To my relief, Ashley seemed grateful for an opportunity to share her story. Apparently, she and her wife had brought their pitbull to live in Ashley's mother's condo while they looked for an apartment of their own. Having pitbulls is against the city of Denver's pet ownership laws, but "Cece is different,” Ashley explained. “She's a sweetheart. The media has turned the public against pitbulls, but they've really just been historically misunderstood…"

Ashley's mother, however, already had two cats. “You know how dogs and cats fight, it's just the way they are," Ashley said tearfully, explaining how her pitbull had eaten her mom's cat earlier that morning.

The demise of Ashley's mother's cat marked the beginning of my Collection of Ice Cream Wisdom, a repertoire of observations ...

See Full Issue: ISSUU.COM/POSTMAGAZINEBDH

OCT 7 VOL 30 ISSUE 3

FEATURE

NARRATIVE

from here, you can see everything unlearning language and feeling without filter

by Emily Tom

“Memoirs are not fiction’s trick-or-treaters because their truths don’t need to dress up in anything to be monstrous.”

—Siena Capone, “How I Read Your Mother”

“Perhaps it is my penchant for tradition, but after I graduate I want to spend the summer revisiting the characters I now carry with me as friends.”

—Nicole Fegan “A Last Ripple of the Wave”

09.27.2019

in search of dogs