Decoding

Post-Modern Architecture: The Meaning of Deconstructivist Architecture in an Ambiguous Era

The architecture of the post-modern period reflects a scattered attempt to answer the profession’s ongoing query of its ambiguous identity within culture. The rejection of the strict modernist “purist fallacy” saw the revival of ornamental historical styles.1 Stagnancy and repetition in academia led to student activism groups and institutional reformation.2 Out-of-work architects with a desire for novelty engaged in deep theoretical concepts and formal experimentation.3 The profession was wrestling with how to best embody the ambivalent spirit of the times, and provide “the age of ambiguity” with an answer.4

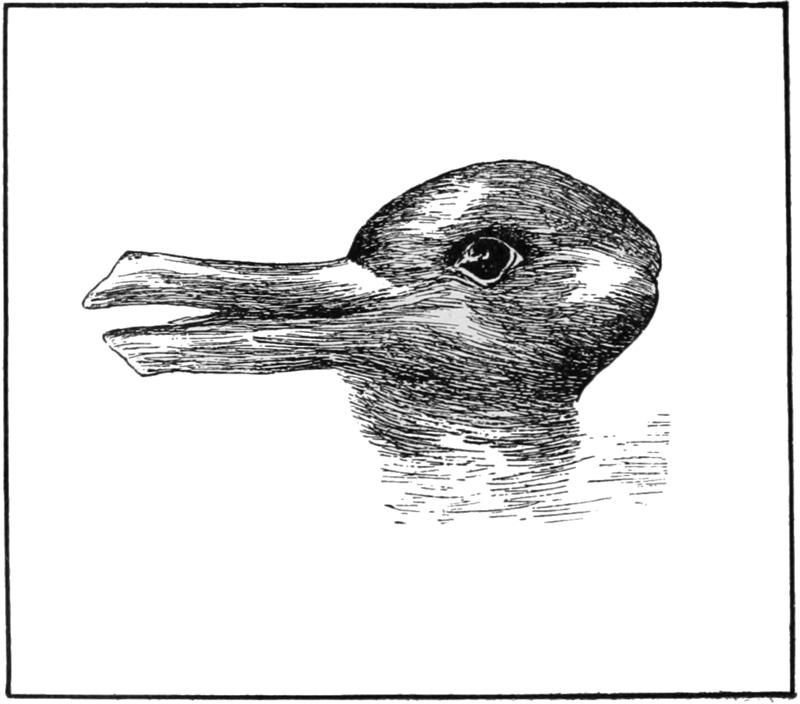

This professional and academic division is, in part, what leads to the ambiguity of meaning and symbolism so evident in the buildings of this era. In “The Language of Post-Modern Architecture”, Charles Jencks describes this phenomenon as “coding”.5 He believes that regardless of the architect’s intentions, a building’s meaning is defined by global, local, cultural, or individual experience.6 Jencks communicates this idea using the famous “duck-rabbit illusion” (see fig. 1), a cartoon first displayed in the German satire magazine “Fliegende Blätter”, later popularized by various psychological publications.7,8

In this essay, I will examine the notion of ‘coding’ as it relates to a series of perspectives most relevant to post-modern practice. The first section will seek to identify the metaphor and symbolism embedded within “Deconstructivist Architecture,” an exhibition held in 1988 by the Museum of Modern Art in New York that contentiously defines the style of many architects today.9,10 The exhibition curators, Phillip Johnson and Mark Wigley, proposed the curated work of seven architects bound by theoretical similarity. They had suggested the work had implemented formal strategies developed by ‘Russian Constructivists’ in locating “the inherent dilemmas within buildings”;11 the suggested architectural equivalent to a linguistic philosophy developed by Jacque Derrida known as ‘Deconstruction Theory’.12 This essay will first examine the “paradigm” of the exhibition;13 the Gehry Residence in Santa Monica by Frank Gehry, followed by the Rooftop Remodelling project in Vienna by Wolf Prix’s studio Coop Himmelb(l)au. Both will be discussed in relation to their Deconstructivist title and its Constructivist heritage.

“Coding” posits that a building’s metaphorical interpretation is more dependent on context than the architect’s intentions.14 I will explore how Gehry’s and Coop Himmelb(l)au’s individual influences have been ‘encoded’ into their work through the use of metaphor and symbolism. The theoretical foundation of Deconstructivist architecture is presented through a mirage of poetics and romanticized tropes, while the remaining post-modern icons represent a collection of historical revival styles, ‘ducks, and billboards’.15 I will examine how both Gehry and Coop Himmelb(l)au communicate their influences and respond to the variability in practice that still defines the post-modern period of architecture.

1. Denise Scott Brown, “On Architectural Formalism and Social Concern: A discourse for Social Planners and Radical Chic Architects,” Oppositions 5, no. 1 (1975): 105-107.

2. C. Ray Smith, Supermannerism: new attitudes in post-modern architecture (New York: E.P Dutton, 1977), 21.

3. Smith, Supermannerism, 28-29.

4. Smith, Supermannerism, 138.

5. Charles Jencks, The Language of PostModern Architecture (New York, NY: Rizzoli, 1977), 40.

6. ibid

7. “Kaninchen und Ente,” Fliegende Blätter, October 23, 1892, 147.

8. Joseph Jastrow, “Do you see a duck or a rabbit, or either?” Popular Science Monthly, no. 54 (1899): 312.

9. Lizzie Crook, “I always felt slightly repulsed’ by deconstructivist label says Daniel Libeskind,” Dezeen, May 6, 2022, https://www.dezeen.com/2022/05/06/ deconstructivism-interview-daniellibeskind/.

10. Tom Ravenscroft, “Deconstructivism ‘killed off postmodernism’ says Peter Eisenman,” Dezeen, May 10, 2022, https://www.dezeen.com/2022/05/10/ deconstructivism-killed-offpostmodernism-says-peter-eisenman/.

11. Phillip Johnson and Mark Wigley, Deconstructivist Architecture (New York, NY: New York Graphic Society Books, Little Brown & Co., 1988), 10-11.

12. Leonard Lawlor, “Jacque Derrida (Standford Encyclopedia of Philosophy),” Standford.edu, August 27, 2021, https:// plato.stanford.edu/entries/derrida/.

13. Tom Ravenscroft, “Deconstructivism exhibition aimed ‘to rock the boat’ says Mark Wigley,” Dezeen, June 1 2022, https://www.dezeen.com/2022/06/01/ deconstructivism-exhibition-moma-markwigley-interview/.

14. Jencks, The Language of Post-Modern Architecture, 40.

15. Jencks, The Language of Post-Modern Architecture, 45.

Figure 1. Joseph Jastrow, “ Do you see a duck or a rabbit, or either?” 1899, illustration, Popular Science Monthly, 54: 312.

Figure 3

Figure 5 Figure 4

Figure 6

Figure 2

16. Cajsa Carlson, “Gehry House extension seems to ‘emerge from the inside of the house,’” Dezeen, Nov 1, 2023, https:// www.dezeen.com/2022/05/30/gehryhouse-extension-emerge-from-insidehouse/.

17. “Gehry Residence / Gehry Partners” Archdaily, accessed on Nov 1, 2023, https://www.archdaily.com/67321/gehryresidence-frank-gehry.

18. Mary Mcleod, “Architecture and Politics in the Reagan Era: From Postmodernism to Deconstructivism,” Assemblage, no. 8 (1989): 51, https://doi.org/10.2307/3171013.

19. Deconstructivism, Ravenscroft, Dezeen.

20. Johnson and Wigley, Deconstructivist Architecture, 22.

21. Johnson and Wigley, Deconstructivist Architecture, 7.

22. Briony Fer, “Metaphor and Modernity: Russian Constructivism,” Oxford Art Journal 12, no. 1 (1989): 16. http://www.jstor.org/ stable/1360263.

23. Kenneth Frampton “Constructivism: The Pursuit of an Elusive Sensibility,” Oppositions 6, no. 1 (1976): 33. 24. ibid

25. Christina Lodder, Russian Constructivism (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1983), 79.

26. Briony Fer, “Metaphor and Modernity,” 16.

27. Johnson and Wigley, Deconstructivist Architecture, 12-15.

28. Jencks, The Language of Post-Modern Architecture, 40.

29. Frampton, “Constructivism,” 33.

30. Diana Agrest, “Design Versus NonDesign,” Oppositions 6, no. 1 (1976), 50. 31. Ibid

Figure 2. Frank O. Gehry, Santa Monica: Frank Gehry House: Ext., 1978, photograph, ARTstor Slide Gallery, accesssed October 28, 2023, https://library-artstor-org.ezproxy. lib.uts.edu.au/#/asset/.

Figure 3. Lyubov Pupova, Painterly Architectonics, Study, 1916, gouache on paper, 18 x 12cm, private collection, Moscow, Artstor, accessed October 29, 2023, https://library-artstor-org.ezproxy.lib. uts.edu.au/#/asset/SCALA_.

Figure 4. Susan Narduli and Perry Blake, Detail of model, second stage; bird’s eye view, n.d, in Phillip Johnson and Mark Wigley, Deconstructivist Architecture (New York, NY: New York Graphic Society Books, Little Brown & Co., 1988), 27.

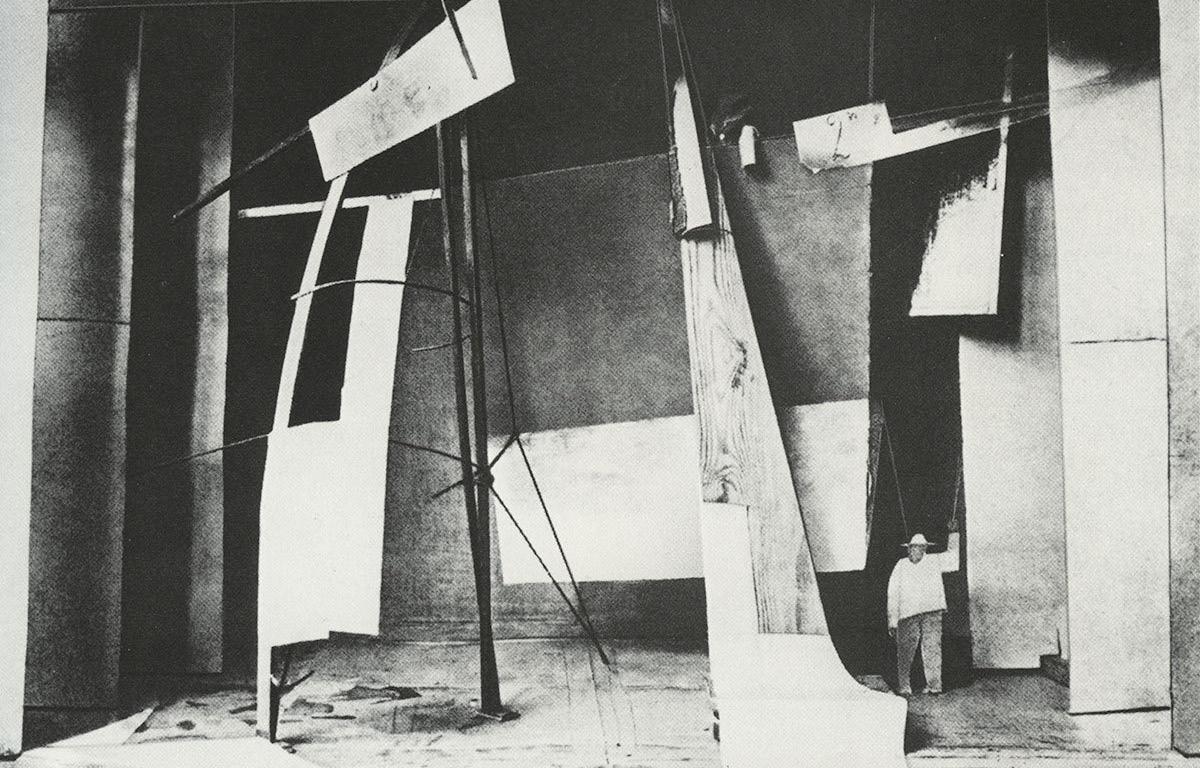

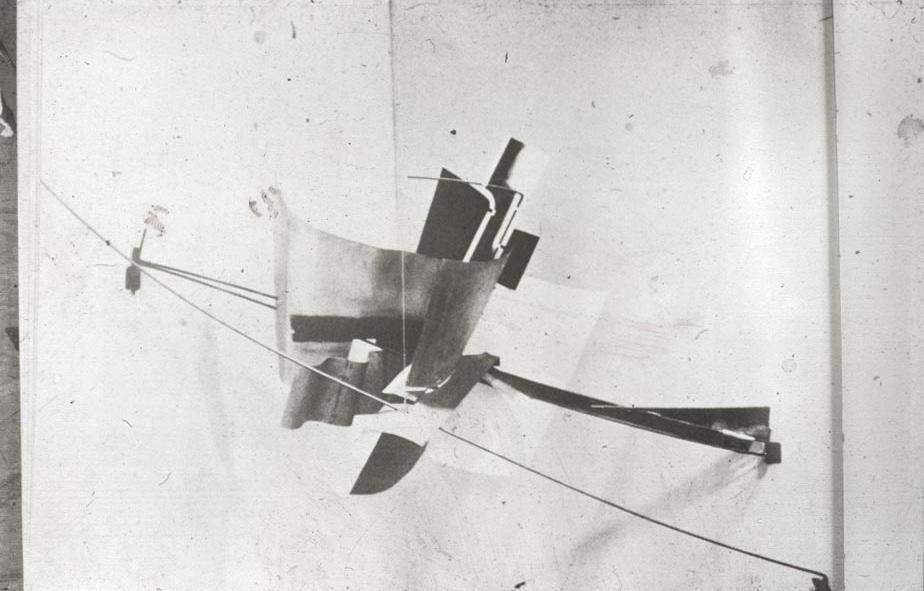

Figure 5. Vladimir Tatlin, Maquette for stage set of Velimir Klebnikov’s verse drama Zangezi, 1923, photograph, in Phillip Johnson and Mark Wigley, Deconstructivist Architecture (New York, NY: New York Graphic Society Books, Little Brown & Co., 1988), 15.

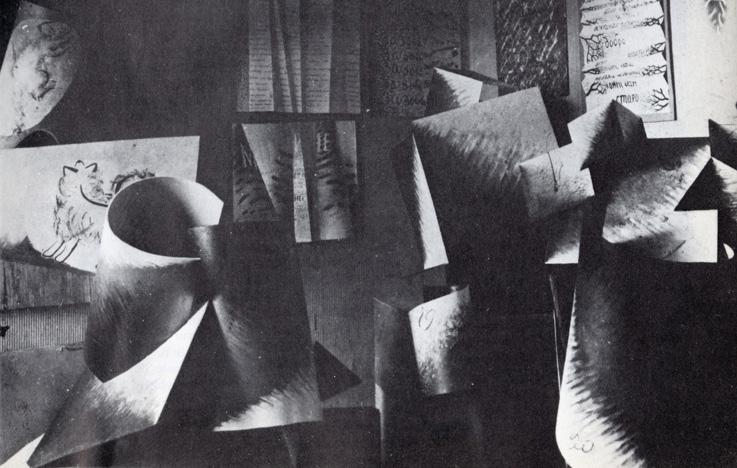

Figure 6. Petr Miturich, View of Petr Miturich’s studio, 1921, photograph, Form and Surface, accessed on October 30, 2023, https://formandsurface.blogspot. com/2013/02/spatial-constructions.html.

Deconstructivist Achitecture and Constructivism in Post-Modern Practice

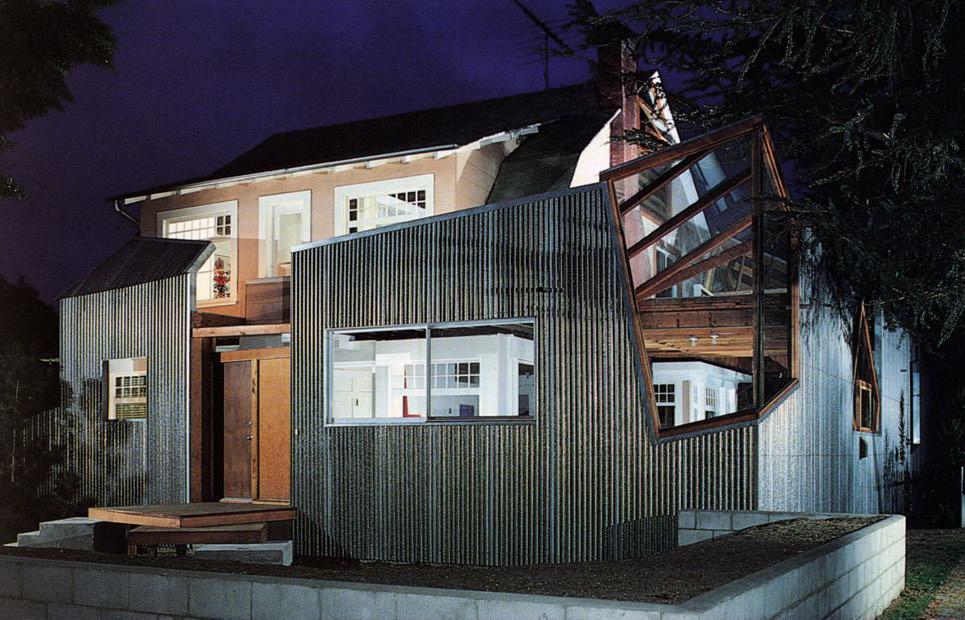

Gehry Residence, Santa Monica, 1978, by Frank Gehry

The Gehry Residence (see fig. 2, fig. 4) is culturally regarded as one of the most seminal works of late 20th-century architecture.16,17 It stands as the poster child of Deconstructivist ‘style’, signifying a drastic formal departure from the post-modern profession’s affinity for historical motifs.18,19 This departure is described by Johnson and Wigley, most poetically of course, as “an extended essay on the convoluted relationship between the conflict within forms and the conflict between forms.”20 Given that ‘Deconstructivist Architecture’ proclaimed its foundation in Constructivism, such a metaphorical description is evidently derived from the formal language belonging to the Russians.21

The “Painterly Architectonics” of Lyubov Pupova share a similar superimposed tension with the facade of the Gehry Residence (see fig 2, fig 3). The material palette and formal angularity seen in the work of Tatlin and Miturich (see fig. 4, fig. 5, fig. 6) may also be recognized in elements of Gehry’s work. While visual comparisons reveal a clear similarity, the techniques developed by the Russians are deeply imbued with a symbolic value contrary to the motives and intentions of Frank Gehry.

The three tenets of Russian Constructivism as written in the ‘First Programme of the Working Group of Constructivists,’ 1921,22 were ‘tektonika’ or technique, ‘faktura’ or material, and construction.23 The tenets were to effectively “exploit industrial matter in accordance with socialist principles”, choose materials deliberately so as to not limit ‘tektonika’, and order the formal process in such a way that allows for transformation.24 While these rules were developed after much of the Russian work debated in ‘Deconstructivist Architecture’, they developed in recognition of “the positive achievement of contemporary artistic activity during the last ten years”.25 Essentially, embedded in every Constructivist ‘composition’, ‘construction’, or ‘spatial configuration’, lies a formal metaphor for “the communistic expression of material structures”.26

Johnson and Wigley confirm that many of the architects included in the Deconstructivist exhibition had little to no direct influence from Constructivism; that the connection was in giving structure to the work the Russians could not.27 Additionally, Jencks’ theory of coding explains that the creator’s intent is not often conveyed in their work.28 However, if the Russians developed such compositional strategies purely in service to their socialist agenda, and if their forms were to be “defined in the process of creation by utilitarian aim of the object”,29 then hypothetically, the formal strategies developed by the Russians, publicized by MOMA, Johnson and Wigley, and employed by Frank Gehry, must encode or symbolize the socio-political energy of the Russian Avant-Garde.

The foregoing is not to suggest that the Gehry Residence is symbolic of Communism, but rather to provide an example of the complex history between linguistic devices and architectural form. The manner in which ‘Deconstructivist Architecture’ relates its selected projects to Constructivism may be understood as a kind of “ideological filtering,”30 where the theoretical underpinnings of ‘Deconstructivist Architecture’ have been derived through continuous processing and recycling of symbols and metaphors.31

Reading Influence and Social Context

Gehry Residence, Santa Monica, 1978, by Frank Gehry

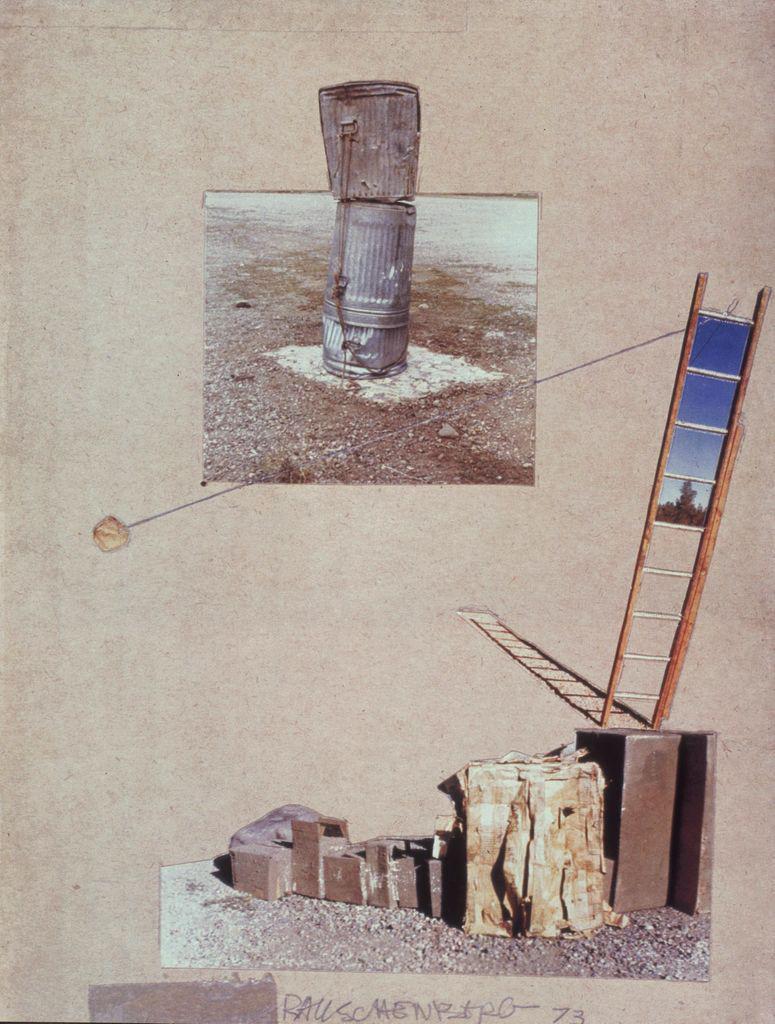

In “Gehry Draws”, Gehry describes camper vans, boats, wheelless vehicles on concrete blocks, and an array of fence types in the surrounding neighborhood of the Santa Monica residence.32 As an immediate contextual response; corrugated metal, chain link fence, and cheap timber are playfully “collaged” (see fig. 9) against the existing Dutch Gambrel.33 The license to do something so unusual, however, was given to him by the artists of the California Funk art movement, particularly Robert Rauschenberg. 34

Rauschenberg’s work (see fig. 7, fig. 8), more specifically his 19541964 ‘Combines’ allowed Gehry to view the scrap material so familiar to Los Angeles in a new light.35 Conceptually, Rauschenberg wished for the combines to operate within the gap between art and life; an amalgamation of found materials, paint, print, etc.36 The process was neither politically intentional, nor of any significant theoretical rigor, but rather pure artistic expression. Rauschenberg argues that “painting is always strongest when in spite of composition;”37 that art is more meaningful when it is found through play.

While Rauschenberg may not have been politically motivated, many of his artistic predecessors were. His seemingly comical use of materials, including, but not limited to, a chicken (see fig. 7), is reminiscent of ‘Dadaism’ (see fig. 10). ‘Dada’ acted in protest to the horrors of the war and high art bourgeois, using humour as a method of interrogating the role of art, or “anti-art”,38 in the Modern age.39 While the motivations differ, the formal similarity of the Rauschenberg combines may be symbolically associated with some of the more satirical examples of Dadaism (see fig. 7, fig. 8, fig. 9).

In an essay discussing formalism and its social relevance, Denise Scott Brown claims that “inspirational sources for a new socially-based formalism might include the pop artists and the city around us.”40 While the motific identity of post-modernism is generally symbolic of a selfreferent closed loop of historical references,41 Gehry drew meaning from his immediate context and artistic community. The openness of the arts permitted Gehry to curiously engage with the junkyard materials so common to his surroundings, affording him an artistic freedom that, at the time, was not seen in architecture.42

32. Frank O. Gehry et al., Gehry Draws (Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press in association with Violette Editions, 2004) 68.

33. “Frank Gehry on his Creative Influences”, n.d, Youtube Video, 4:54, posted by “Getty Research Institute”, April 2013, https://www.youtube. com/watch?v=zQ-Kf3sJfok&ab_ channel=GettyResearchInstitute.

34. Ibid

35. “Combine (1954-1964),” Robert Rauschenberg Foundation, accessed on October 23, 2023, https://www. rauschenbergfoundation.org/art/galleries/ series/combine-1954-64.

36. Catherine Craft, “In Need of Repair: The Early Exhibition History of Robert Rauschenberg’s Combines” The Burlington Magazine 154, no. 1308 (2012): 191, https:// www-jstor-org.ezproxy.lib.uts.edu.au/ stable/23232482?sid=primo.

37. Ibid

38. Dafydd Jones, Dada 1916 in Theory : Practices of Critical Resistance (Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, 2014), 1-3.

39. Jones, Dada 1916 in Theory, 9

40. Scott Brown, “On Architectural Formalism and Social Concern,” 112.

41. Daniel Libeskind, “‘Deus ex Machina’/’Machina ex Deo’ Aldo Rossi’s Theater of the World,” Oppositions 21, no. 1 (1980): 3.

42. “Frank Gehry on his Creative Influences”, Getty Research Institute.

Figure 7. Robert Rauschenberg, Odalisque, 1955-1958, freestanding combine-painting, Artstor, accessed on October 30 2023, https://libraryartstor-org.ezproxy.lib.uts.edu.au/#/asset/ ARTSTOR_103_41822001527181.

Figure 8. Robert Rauschenberg, untitled, 1973, collage, Artstor, accessed on October 30 2023, https://library-artstororg.ezproxy.lib.uts.edu.au/#/asset/ ARTSTOR_103_41822001605565.

Figure 9. Grant Mumford, Gehry Residence, Santa Monica, California, 1978, gelatin silver prints, 16 x 20”, Archdaily, accessed on October 30, 2023, https://www.archdaily. com/351021/the-indicator-architectures-1979/5152f642b3fc4b5fe500009c-theindicator-architecture-s-1979-image?next_ project=no.

Figure 10. Marcel Duchamp, Bicycle Wheel, 1951 (third version, after lost original of 1913), Metal wheel mounted on painted wood stool, 51 x 25 x 16 1/2”, Artstor, accessed on Nov 2, 2023, https:// jstor.org/stable/community.14555071.

Figure 8

Figure 10

Figure 9

Figure 7

Figure 15

Figure 16

Figure 11

Figure 12

Figure 13 Figure 14

43. Johnson, Phillip & Wigley, Mark, Deconstructivist Architecture, 80.

44. Johnson, Phillip & Wigley, Mark, Deconstructivist Architecture, 17.

44. Johnson, Phillip & Wigley, Mark, Deconstructivist Architecture, 18.

45. Herbert Muschamp, “Postcards From the Old World Gone Global” New York Times, (2001): 1, https://www.nytimes. com/2001/08/12/arts/art-architecturepostcards-from-the-old-world-gone-global. html.

46. Ibid

47. Ibid

48. Noever et al., Coop HIimmelb(l)au, Beyond the Blue (Wein, Vienna: MAK, 2007), 6.

49. Anthony Vidler, Editor’s note, in Kenneth Frampton “Constructivism: The Pursuit of an Elusive Sensibility,” Oppositions 6, no. 1 (1976): 25.

50. Ibid

51. Noever et al., Beyond the Blue, 6.

Figure 11. Coop Himmelb(l)au, Axonometrie axonometry, Ansicht view, 1988, in Noever et al., Coop HIimmelb(l) au, Beyond the Blue (Wein, Vienna: MAK, 2007) 87.

Figure 12. Georgii and Vladimir Sternberg, Spatial Construction, 1921-1922, Beaudouin Architects, Accessed on October 30 2023, http://www.beaudouin-architectes. fr/2015/10/obmoku/.

Figure 13. Coop Himmelb(l)au, Collage, 1983, in Noever et al., Coop HIimmelb(l) au, Beyond the Blue (Wein, Vienna: MAK, 2007) 86.

Figure 14. Vladimir Tatlin, Corner Relief, 1914, photograph, Academic Museum, accessed October 29, 2023, https:// academicmuseum.lafayette.edu/art234/ Images/10-09-01.jpg.

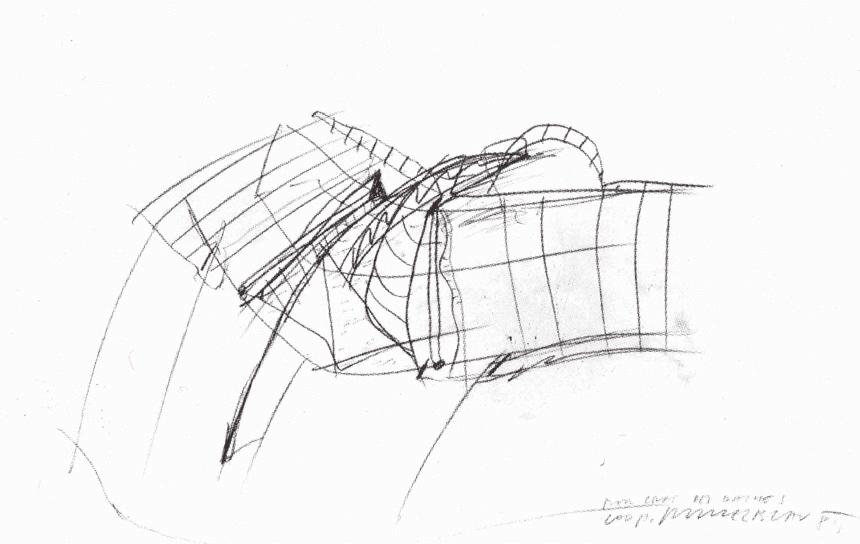

Figure 15. Coop Himmelb(l)au, Entwurfsskizze design sketch, 1983, in Noever et al., Coop HIimmelb(l)au, Beyond the Blue (Wein, Vienna: MAK, 2007) 86.

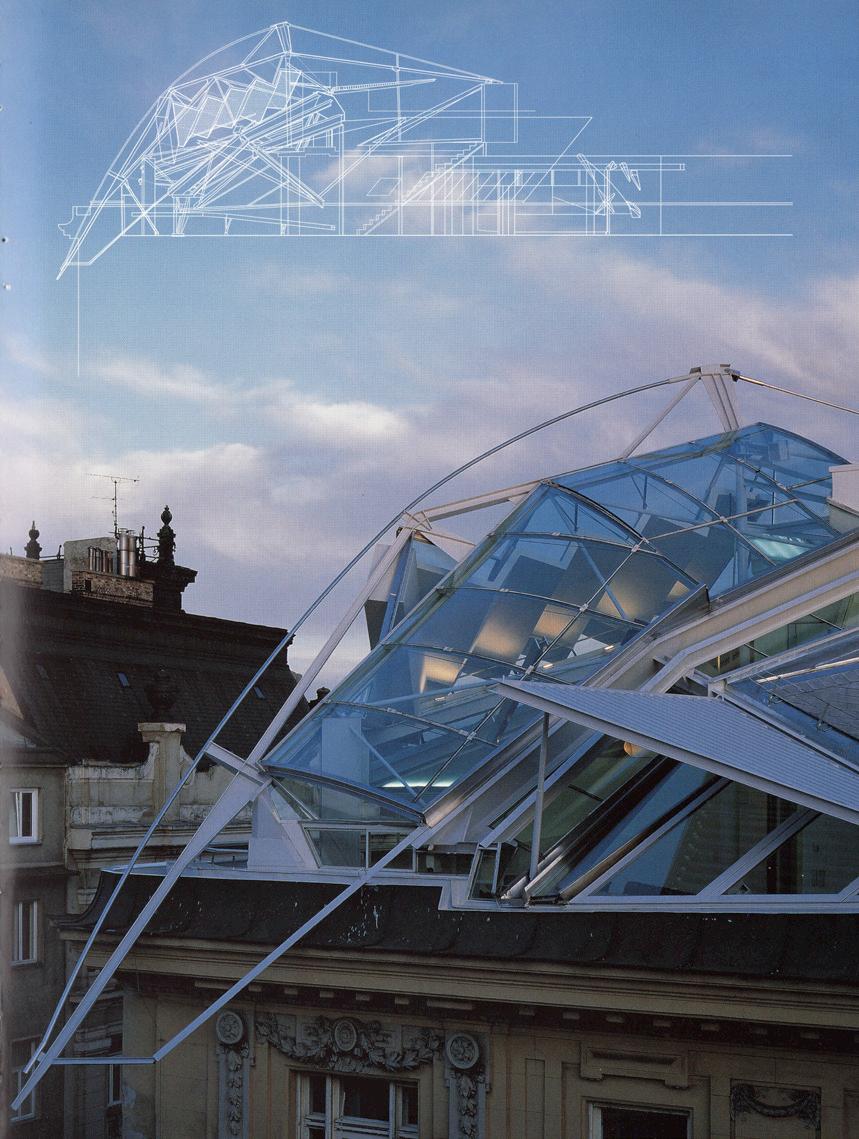

Figure 16. Coop Himmelb(l)au, Rooftop Remodelling, 1988, photograph by Rory Hyde, 2003, Flickr, accessed on Nov 1, 2023, https://www.flickr.com/photos/ roryrory/2447734023.

Deconstructivist Achitecture and Constructivism in Post-Modern Practice

Rooftop Remodelling, Vienna, 1988, by Coop Himmelb(l)au

While the artistic milieu of Los Angeles resonates loudly within the walls of Gehry Residence, its theoretical Deconstructivist identity is not as apparent. In the Rooftop Remodelling project by Coop Himmelb(l) au, however, the symbolism reads much clearer. Its immediate formal and material similarity to the work of Constructivists Valdimir Tatlin, Georgii, and Vladimir Sternberg is striking to say the least (see fig. 11, fig. 12, fig. 13, fig. 14, fig. 15). The exhibition catalogue describes the Rooftop Remodelling in Vienna (see fig. 11) as a “stable form that has been infected by an unstable bimorphic structure.”43 Johnson and Wigley use this parasitic/alien metaphor in describing the collective work of the exhibition as well, but its application to this particular project is strong.44

Intentionally encoded into the Rooftop Remodelling project is a more politically charged spirit than previously seen in the artistically playful construction of the Gehry Residence. As stated in “Deconstructivist Architecture”, the work is to “exploit the weakness in tradition in order to disturb rather than overthrow it.”45 A politically loaded statement in its own right, but particularly in reference to the way in which Coop Himmelb(l) au responds to the Viennese context. Herbert Muschamp argues that since the Viennese fabric was an identity constructed by the Hapsburg Empire, the appearance of the city was largely synthetic and symbolic of the monarchy’s intention to communicate unity.45 Therefore, deconstructing it was a task for artists and intellectuals, interested in revealing its lost social complexity (see fig. 16).46

The political drive, as well as the clear formal similarities, is where the Rooftop Remodelling project and Constructivism share an identity; an impetus for a greater cause by way of formal experimentation. Coop Himmelba(l)au used the project to react to a context they wished to “deconstruct.”47, 48 In a similar vein, the Russians sought to extract sociopolitical meaning from industrial material by way of formal experimentation. Both parties acted out of impulse for cause, allowing Johnson and Wigley to apply an ideological filter in their comparison, and then categorize the Rooftop Remodelling project as Deconstructivist, or symbolic of Russian Constructivism. In summary, both parties spontaneously experimented “in attempt to gain hegemony for art”;49 the Russians over the techniques of the industrial revolution,50 Coop Himmelb(l)au through a subconscious influence in the name of artistic freedom.51

Reading Influence and Social Context

Rooftop Remodelling, Vienna, 1988, by Coop Himmelb(l)au

In describing Coop Himmelb(l)au’s architecture, Jeffery Kipnis notes that because of the studio’s refusal to pledge allegiance to predetermined trend or precedent, those who experience a Coop Himmelb(l)au building must rely on analogy to understand it.52 “It looks like an insect! a wing! an act of violence! a hurricane! All of these are evocative, even true. They capture [well, for example,] the work’s avoidance of familiar architectural signs and symbols (see fig. 17, fig. 19).”53 Coop Himmelb(l)au seems to avoid such convention, in part, by frequently engaging in the use linguistic devices; drawing analogies from the fetus and the embryo,54 blazing fire,55 and of course, the sky.56 “Architecture that bleeds, that exhausts, that whirls and even breaks.”57 Evidently, language plays an important role as a tool, not only in communicating the work and influences of Coop Himmelb(l)au, but in contributing to their perception. This tool that did not go unnoticed by other architects of the era.

Poetically behaving in a similar vein to Coop Himmelb(l) au, Lebbeus Woods used analogy and metaphor in an attempt to communicate the urgency of matters, such as natural disaster or post-war reconstruction (see fig. 21).58 With a sense of agency born from a rather difficult upbringing,59 Woods was primarily interested in the philosophical potential of architecture, using language more as a means of provocation and ‘world-building’, as he might say.60 Among other architects and students, he felt that an impending corporate climate would potentially interfere with the conceptual clarity of built work;61 a salient argument in support of the era’s formal and symbolic experimentation (see fig.18, fig. 19).62, 63, 64

While the influence of the existing Viennese urban landscape essentially offered the Rooftop Remodelling project a context in which to parody,65 Prix states that his primary sources of inspiration come from outside the realm of Architecture.66 He believes that by “only thinking in architectural terms, only architecture will come out”.67 He expresses admiration for René Descartes’ writing of analysis, construction, skepticism, and recursion.68 Another identifiable philosophical alignment held by Prix is that of Jacque Derrida, who emphasizes the daily role of the subconscious, not unline native Viennese psychoanalysts Sigmund Freud and Otto Rank.69 “That’s my philosophy, as well,” Prix notes.70 Interrogating architectural behaviour through a metaphorical interpretation of the subconscious is what makes Coop Himmelb(l)au fluent in the language of coding.71

52. Noever et al., Coop HIimmelb(l)au, Beyond the Blue, 43.

53. Ibid

54. Wolf Prix et al., Out of the Clouds: Wolf dPrix: Sketches 1967-2020, (Basel, Switzerland: Birkhauser, 2022), 7.

55. “Architecture Must Blaze, 1980” Coop Himmelb(l)au, accessed on Nov 1, 2023, https://coop-himmelblau.at/projects/theblazing-wing/.

56. “Studio” Coop Himmelb(l)au, accessed on Nov 1, 2023, https://coop-himmelblau. at/studio/.

57. Coop Himmelb(l)au, “Architecture Must Blaze, 1980.”

58. Lebbeus Woods, War and Architecture = Rat i Arhitektura (New York, NY: Princeton Architectural Press, 1993), 14.

59. Joseph Becker, “The fault is ours: Joseph Becker on Lebbeus Woods”, Bulletin, no. 213 (2023), https://christchurchartgallery. org.nz/bulletin/174/the-fault-is-ours-josephbecker-on-lebbeus-woods.

60. Woods, War and Architecture, 1. 61. Becker, “The fault is ours.”

62. Amy Thomas, “The Political Economy of Flexibility: Deregulation and the trasnforamion of Corporate Space in the Postwar City of London,” in Neoliberalism on the Ground: Architecture and Transformations from 1960 to the Present, ed. Kenny Cupers, Helena Mattsson, and Catharina Gabrielsson, (Pitssburgh, PA: University of Pittsburgh Press, 2020, 141. 63. Scott Brown, “On Architectural Formalism and Social Concern,” 105-112.

64. C. Ray Smith, Supermannerism, 21-25. 65. Leon Whiteson, “Smashing Design Architecture: Jumbled walls, zigzag roofs? L.A.’s first taste of Deconstructivism is soon to be seen on Melrose Avenue”, Los Angeles Times, no. 1 (1990): accessed Nov 1, 2023, https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm1990-09-04-vw-659-story.html.

66. “Coop Himmelb(l)au, Wolf Prix: What is architecture?” n.d, Youtube Video, 6:42, posted by “WIA - What is architecture?“, March 2017, https://www. youtube.com/watch?v=uHcHdXxzSRE&ab_ channel=WIA-Whatisarchitecture%3F.

67. Ibid

68. Wolf Prix et al., Out of the Clouds, 21. 69. Wolf Prix et al., Out of the Clouds, 14. 70. Ibid

71. Jencks, The Language of PostModernism, 40.

Figure 17. Coop Himmelb(l)au, The Blazing Wing, 1980, Coop Himmelb(l)au, accessed on Nov 1, 2023, https://coop-himmelblau. at/projects/the-blazing-wing/.

Figure 18. Coop Himmelb(l)au, Restless Sphere Basel Contact, 1971, accessed on Nov 1, 2023, https://coop-himmelblau.at/ first-ten-years/.

Figure 19. Coop Himmelb(l)au, Office in Falkestrasse, n.d, accessed on Nov 1, 2023, https://ducciomalagamba.com/en/ architects/coop-himmelblau/562-officefalkestrasse-vienna-2/.

Figure 20. Haus-Rucker Co., Giant Billboard, New York, 1970, Archdaily, accessed on Nov 1, 2023, https://www. archdaily.com/582842/haus-rucker-coarchitectural-utopia-reloaded/54a2c2a9e58 ece22f6000008-haus-rucker-co-gian.

Figure 21. Lebbeus Woods, SHARD House, from the series San Francisco Project: Inhabiting the Quake, 1995, Graphite and pastel on paper, Collection SFMOMA, accessed on Nov 1, 2023, https:// christchurchartgallery.org.nz/bulletin/174/ the-fault-is-ours-joseph-becker-on-lebbeuswoods.

Figure 21

Figure 20

Figure 17

Figure 18

Figure 19

Figure 22

Figure 23

22. Frank O. Gehry, “Gehry House”, 1979, Photograph, ARTstor Slide Gallergy, accessed October 23, 2023, https://libraryartstor-org.ezproxy.lib.uts.edu.au/#/asset/ AWSS35953_35953_29394891.

Figure 23. Coop Himmelb(l)au, “Rooftop Remodelling Falkestrasse”, Photograph, Archello, accessed Nov 1, 2023, https:// archello.com/project/rooftop-remodelingfalkestrasse.

Conclusion

In the complex tapestry of post-modern architecture, the projects by Frank Gehry and Coop Himmelb(l)au stand as defining benchmarks. The Deconstructivist Architecture exhibition of 1988 sought to connect them to the formal strategies of the Russians. Gehry approaches the design of the Santa Monica residence almost as if an uninhibited child playing with his toys, inspired by his immediate surroundings. Coop Himmelb(l) au poetically endowed the Rooftop Remodelling project in Vienna with beauty, anger, fire, and ice, through an intuitive expression of the subconscious.

Gehry and Prix thoughtfully used these projects to address an era of artistic uncertainty by symbolising what was interesting to them. Cultural and political energy, cross-disciplinary engagement, and a compulsion to express the need for change are encoded into the conception and communication of the projects. Both generally exhibit an avoidance of convention, subverting public perception of architectural familiarity to metaphor and analogy.72 Over time, their metaphorical identity will continue to change with the emergence of new technologies, cultural shifts, and artistic innovation, furthering the depth of the code, and enriching the complexity of architectural meaning.

Figure

72. Charles Jencks, The Language of PostModernism, 40.

Bibliography

Agrest, Diana. “Design versus Non-Design.” Oppositions 6, no. 1 (1976): 50.

Becker, Joseph. “The fault is ours: Joseph Becker on Lebbeus Woods,” Bulletin, no. 213 (2023). https:// christchurchartgallery.org.nz/bulletin/174/the-fault-is-ours-joseph-becker-on-lebbeus-woods.

Carlson, Cajsa. “Gehry House extension seems to ‘emerge from the inside of the house.’” Dezeen, Nov 1, 2023. https:// www.dezeen.com/2022/05/30/gehry-house-extension-emerge-from-inside-house/.

Coop Himmelb(l)au. “Architecture Must Blaze, 1980.” Accessed on Nov 1, 2023. https://coop-himmelblau.at/projects/the- blazing-wing/.

Coop Himmelb(l)au. Axonometrie axonometry, Ansicht view. 1988. Noever, P., J. Kipnis, S. Lanvin, and Coop Himmelb(lau. Coop Himmelb(l)au. Beyond the Blue. Wein, Vienna: MAK, 2007, 87.

Coop Himmelb(l)au. Collage. 1983. Noever, P., J. Kipnis, S. Lanvin, and Coop Himmelb(l)au. Coop Himmelb(l)au. Beyond the Blue. Wein, Vienna: MAK, 2007, 86.

Coop Himmelb(l)au. Entwurfsskizze design sketch. 1983. Noever, P., J. Kipnis, S. Lanvin, and Coop Himmelb(l)au. Coop Himmelb(l)au. Beyond the Blue. Wein, Vienna: MAK, 2007, 86.

Coop Himmelb(l)au. “Studio.” Accessed on Nov 1, 2023. https://coop-himmelblau.at/studio/.

“Coop Himmelb(l)au, Wolf Prix: What is architecture?” n.d. Youtube Video, 6:42. Posted by “WIA - What is architecture?“, March 2017. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uHcHdXxzSRE&ab_channel=WIA-Whatisarchitecture%3F.

Craft, Catherine. “In Need of Repair: The Early Exhibition History of Robert Rauschenberg’s Combines.” The Burlington Magazine 154, no. 1308 (2012): 191. Access October 23, 2023. https://www-jstor-org.ezproxy.lib.uts.edu.au/ stable/23232482?sid=primo.

Crook, Lizzie. “‘I always felt slightly repulsed’ by deconstructivist label says Daniel Libeskind.” Dezeen, May 6, 2022. https://www.dezeen.com/2022/05/06/deconstructivism-interview-daniel-libeskind/.

Fer, Briony. “Metaphor and Modernity: Russian Constructivism.” Oxford Art Journal 12, no. 1 (1989): 14–30. http://www. jstor.org/stable/1360263.

Frampton, Kenneth. “Constructivism: The Pursuit of an Elusive Sensibility” Oppositions 6, no. 1 (1976): 25 - 33.

“Frank Gehry on his Creative Influences”. n.d. Youtube Video, 4:54. Posted by “Getty Research Institute,” April 2013. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zQ-Kf3sJfok&ab_channel=GettyResearchInstitute.

Gehry, O., H. Bredekamp, R. Violette, and M. Rappolt. Gehry Draws. Cambridge, Mass: MIT Press in association with Violette Editions, 2004.

“Gehry Residence / Gehry Partners.” Archdaily. Accessed on Nov 1, 2023. https://www.archdaily.com/67321/gehryresidence-frank-gehry.

Jencks, Charles. The Language of Post-Modern Architecture. New York, NY: Rizzoli, 1977.

Jones, Dafydd. Dada 1916 in Theory : Practices of Critical Resistance. Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, 2014. Access October 30, 2023. ProQuest Ebook Central.

Bibliography

Johnson, Phillip and Wigley, Mark. Deconstructivist Architecture. New York, NY: New York Graphic Society Books, Little Brown & Co., Boston, 1988.

Jastrow, Josheph. “Do you see a duck or a rabbit, or either?” Illustration. Popular Science Monthly, no. 54 (1899): 312.

Jastrow, Josheph. “Do you see a duck or a rabbit, or either?” Popular Science Monthly, no. 54 (1899): 312.

Kaninchen und Ente. Fliegende Blätter, October 23, 1892.

Lawlor, Leonard. “Jacques Derrida (Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy).” Stanford.edu. August 27, 2021. https://plato. stanford.edu/entries/derrida/.

Libeskind, Daniel. “’Deus ex Machina’/’Machina ex Deo’ Aldo Rossi’s Theater of the World” Oppositions 21, no. 1 (1980): 3.

Lodder, Christina. Russian Constructivism. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1983.

McLeod, Mary. “Architecture and Politics in the Reagan Era: From Postmodernism to Deconstructivism.” Assemblage, no. 8 (1989): 23–59. https://doi.org/10.2307/3171013.

Muschamp, Herbert. “Postcards From the Old World Gone Global” New York Times (2001): Access Oct 31, 2023. https:// www.nytimes.com/2001/08/12/arts/art-architecture-postcards-from-the-old-world-gone-global.html

Narduli, Susan, and Blake, Perry. Detail of model, second stage: bird’s eye view. Johnson, Phillip, and Wigley, Mark, Deconstructivist Architecture. New York, NY: New York Graphic Society Books, Little Brown & Co., Boston, 1988.

Noever, P., J. Kipnis, S. Lanvin, and Coop Himmelb(l)au. Coop HIimmelb(l)au, Beyond the Blue. Wein, Vienna: MAK, 2007. Prix, W., K. Feireiss, G. Feuerstein, T. Mayne, and Coop Himmelb(l)au. Out of the Clouds: Wolf dPrix: Sketches 1967–2020 Basel, Switzerland: Birkhäuser, 2022.

Ravenscroft, Tom. “Deconstructivism exhibition aimed “to rock the boat” says Mark Wigley” Dezeen. June 1 2022. https:// www.dezeen.com/2022/06/01/deconstructivism-exhibition-moma-mark-wigley-interview/.

Ravenscroft, Tom. “Deconstructivism ‘killed off postmodernism’ says Peter Eisenman.” Dezeen. May 10, 2022. https://www. dezeen.com/2022/05/10/deconstructivism-killed-off-postmodernism-says-peter-eisenman/.

Robert Rauschenberg. “Combine (1954-1964)”. Accessed October 23, 2023. https://www.rauschenbergfoundation.org/art/ galleries/series/combine-1954-64.

Scott Brown, Denise. “On Architectural Formalism and Social Concern: A discourse for Social Planners and Radical Chic Architects.” Oppositions 5, no. 1 (1975): 99 - 119.

Smith, C. Ray. Supermannerism : new attitudes in post-modern architecture. New York, NY: E.P Dutton, 1977.

Tatlin, Vladimir. Maquette for stage set of Velimir Klebnikov’s verse drama Zangezi. 1923. Johnson, Phillip, and Wigley, Mark, Deconstructivist Architecture. New York, NY: New York Graphic Society Books, Little Brown & Co., Boston, 1988,15.

Bibliography

Thomas, Amy. “The Political Economy of Flexibility: Deregulation and the transformation of Corporate Space in the Postwar City of London.” In Neoliberalism on the Ground: Architecture and Transformations from 1960 to the Present. Edited by Kenny Cupers, Helena Mattsson, and Catharina Gabrielsson, 127-150. Pittsburgh, PA: University of Pittsburgh Press, 2020.

Whiteson, Leon. “Smashing Design Architecture: Jumbled walls, zigzag roofs? L.A.’s first taste of Deconstructivism is soon to be seen on Melrose Avenue.” Los Angeles Times, no. 1 (1990): Access Nov 1, 2023. https://www.latimes.com/ archives/la-xpm-1990-09-04-vw-659-story.html

Woods, Lebbeus. War and Architecture = Rat i Arhitektura. New York, NY: Princeton Architectural Press, 1993.