History | Founding Fathers

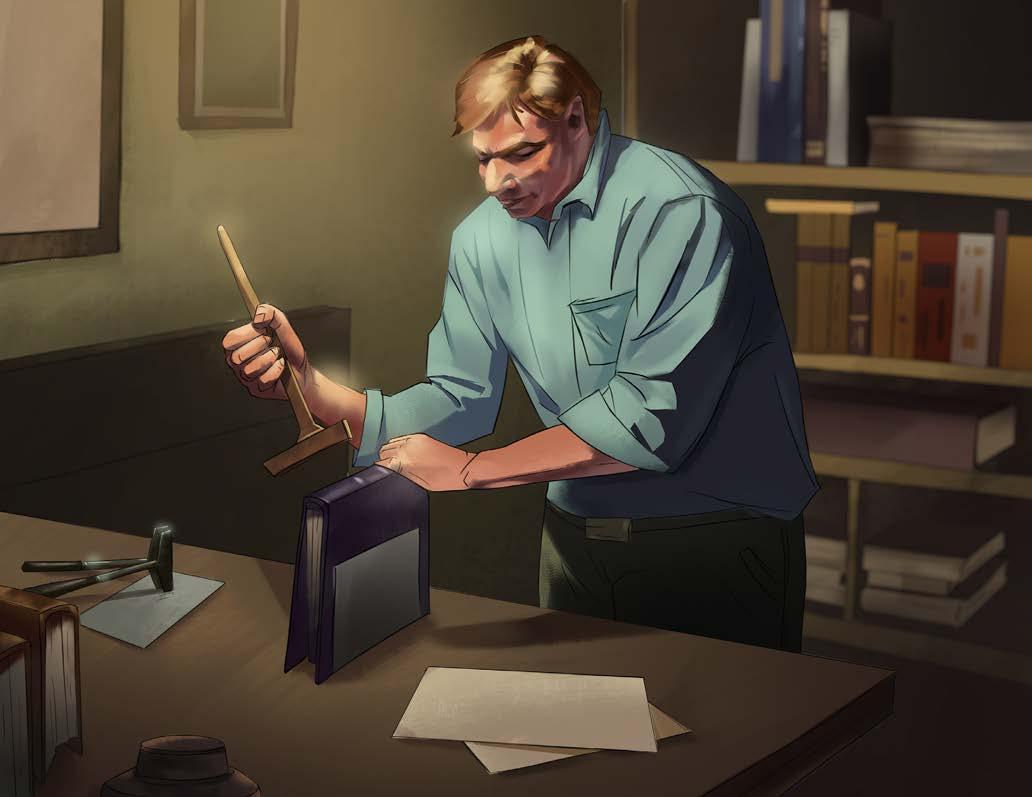

The Productive Persistence of John Adams The Thirteen Colonies were verging on bankruptcy as the Revolutionary War dragged on, and John Adams— cantankerous and quick tempered as he was—tried and tried again to secure much needed financial ties in Europe WRITTEN BY

David W. Swafford

K

nown to be blunt, impatient, and cantankerous, John Adams, second president of the United States, is not generally thought of as having a diplomat’s character. He had a quick temper and, at times, could be explosive. In spite of those flaws, he nevertheless scored major success as a diplomat in Europe at a very crucial time for America. Credit that to his bedrock principle of putting the public good first, and to his unwavering belief (with all of his heart, soul, mind, and strength) in the founding ideals of this country. In September 1780, Congress designated Adams as minister plenipotentiary to the United Provinces of the Netherlands (The Dutch Republic) to negotiate a sizeable loan and a commercial trade treaty. At that crucial stage, the Thirteen Colonies were, for the most part, bankrupt. The Revolutionary War had been dragging on for years, but 72

America had no public money to fund the war. In addition to a quick loan, the Colonies desperately needed a foreign source of trade and commerce. The war had totally curtailed the traditional trade with Britain, and economies throughout the Colonies contracted sharply from 1776 onward. So why was Holland targeted? Back then, Amsterdam was the internationally recognized money center of all Europe as well as Northern Europe’s trade emporium. As William Henry Trescot mentions in his “Diplomacy of the Revolution: An Historical Study” (1852), “The large commerce, vast capital, and banking character of Holland, rendered an alliance with the Netherlands more important to the United States than any European connexion after that with France.” Immovable Objects Upon Adams’ arrival there, he decided to locate in Amsterdam, where he

could meet and speak with bankers. Nevertheless, it did not take him long to run into difficulties. He had in his possession letters of introduction from the President of Congress, Samuel Huntington, intended for the StatesGeneral (the representative body) and the Stadtholder (the chief magistrate). The letters were not accepted because the United States did not have diplomatic recognition from the Dutch Republic. America was still universally regarded technically as a group of disgruntled English colonies. In order to get a loan from the Dutch, much less a commercial treaty, the upstart nation first had to receive diplomatic recognition as an independent country. The chances of obtaining that were quite slim. First of all, the Stadtholder, William V, was a staunch Anglophile and a direct cousin of George III, king of England. Second, the States-General insisted upon neutrality in the ongoing war between AMERI CAN ESSE NCE