6 minute read

Got Neon?

Our nation’s darkest times have sparked a renaissance, with New England’s last remaining neon artisan making iconic beacons for everything from movie sets to local businesses

WRITTEN BY Alice Giordano

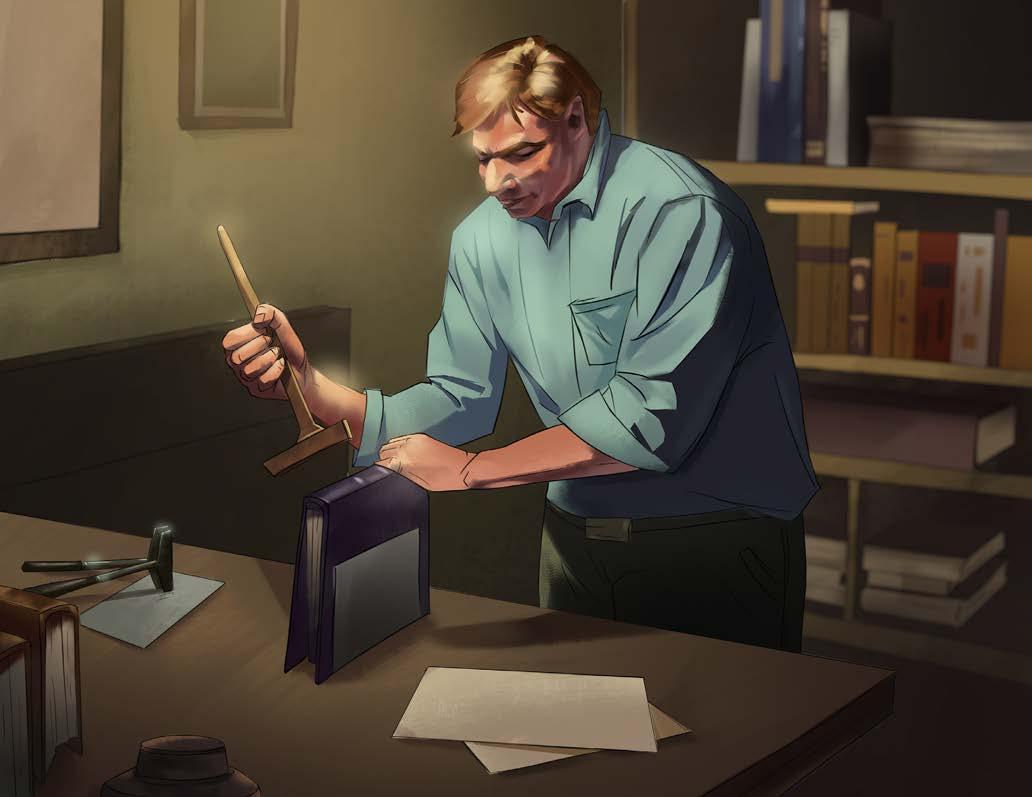

left Among Neon Williams’s clients is a retired airline pilot who wanted to restore a vintage American Airlines sign.

—DAVE WALLER

left Neon Williams has been making neon signs by hand for 87 years.

Watch the movie “Free Guy,” and you’ll see how Neon Williams helped garner glowing reviews for the big screen action flick.

“Yeah, we made about 13 signs for the movie,” said Neon Williams co-owner Dave Waller, proudly.

The company’s glass-bending works of art are carefully scattered throughout the Boston-based movie, including a penguin holding an ice cream, a fish, and Waller’s favorite—an eerie, flickering, 16-foot fictional Pleasure Hotel sign. The latter was made for a scene filmed in a gritty Chinatown alleyway.

“It seemed to be a place where all the restaurants dump all their grease,” Waller playfully bemoaned. His company is already working on more signage for another major Hollywood movie in production.

In 2019, Dave and his wife Lynn bought Neon Williams, a company that has been making neon signs for some 87 years. It’s located in an ungentrified industrial area of Somerville, Massachusetts—an ironic setting for the revival of a celebrated craft dimmed at the turn of the millennium.

Neon lights, the long-celebrated iconic beacons of classic roadside diners and aged hole-in-the-wall bars, were replaced by the allure of cheaper, modern lighting. So went the 5 miles of gas-filled tubes that once lit up Boston’s fabled Citgo sign, which today is illuminated by 240,000 LED lights as it still stands over Fenway Park.

The Wallers—Massachusetts natives who cringe at the controversial conversion of the giant Citgo sign—bought the neon company mostly for nostalgic reasons. After all, who could let the lights go out on a company responsible for Boston’s cherished signs, such as the neon-lit Paramount Theatre marquee and other legendary illuminations? The company also had its place on the big screen long before “Free Guy.” Its neon handiwork can be found throughout the 1978 movie, “The Brink’s Job.”

Of course, the Wallers also wanted to make a profit with their new venture. But soon, the light at the end of that tunnel got, well, a little, unexpectedly fuzzy.

Not long after buying the business, the pandemic hit, causing an untold number of American businesses to go dark, including many around the Boston area, leaving Neon Williams wondering if it would be next. But as Dave Waller put it, the pandemic was, surprisingly enough, like lightning in a bottle for the company.

“COVID gave people the time to put together a to-do list, and on that to-do list was to fix that old vintage sign out in the barn or up in the attic,” said Waller. “Once we got it lit up, people went absolutely berserk to see it running again.”

A retired airline pilot hired Neon Wiliams to restore a vintage American Airlines sign featuring the company’s signature blue eagle and red “AA” initials.

Cheapo Records in Central Square also hired Neon Williams to get its iconic neon, record-shaped sign back agleam, after years of being lightless. Colleen’s, a popular ice cream shop in Medford Square, had the company create an old-timey, pink neon sign to draw in patrons.

The company, which has amassed and restored a myriad of vintage neon signs, also has found a niche in the rental market for neon signs, with weddings topping its rental clientele.

The rebirth of retro signage also inspired a contemporary evolution, with new-age companies drawn to its marketable, magical beauty.

Neon Williams was also called upon to make from scratch a vibrant blue sign in the shape of a Ludwig Vistalite drum set, along with flashing hi-hats. The sign dons the window of a music school, Senchant’s Art of Teaching, in Canton, Massachusetts.

“It’s interesting: neon can be vintage, but it can also be very modern,” said Waller. “It has such nice lines and so much more style potential than a plastic sign. You can put a lot of art deco lines in it to make it look like something from the 1940s, or you can put something metallic in it and make it look like something from 2021.”

No matter how old neon signs become, the way they are made will always be a classic, unchangeable form of patient artistry.

As they always have, glass benders,

above Inside Neon Williams’s factory in Somerville, Mass.

as neon craftsmen are called, spend days in workshops where daily temperatures average 100 degrees: heating, bending, and cooling each curve, in no bigger than 8-inch sections at a time. Then comes the mastery of creating neon colors.

Neon, a noble gas, glows red when lit. Neon is mixed with other gases like helium and argon to produce various colors. Neon Williams, for example, combined neon with a Voltarc Turquoise tube to create the unique rose-like color of the sign they made for seafood and raw bar Ivory Pearl in Brookline, Massachusetts.

The comeback of neon brings an even bigger twist of fate during trying economic times, with escalating inflation on the horizon. The cost of a neon sign far out-ranks the cost of a plastic business sign, with repairs also being pricey compared to just replacing a lightbulb.

But there’s just something about neon.In New York, residents led a charge to save the neon sign belonging to the Palomba Academy of Music in the Bronx. The 64-year-old fabled music school with an array of famous graduates, including Grammy Awardwinning drummer Will Calhoun of the band Living Colour, was forced out of business by the pandemic shutdown in 2020.

Nostalgic New Yorkers prevailed in their campaign, and the Palomba sign is now on display at the American Sign Museum in Cincinnati.

The Neon Museum in Nevada is still fundraising to pay for the $350,000 repair costs to fix the local Hard Rock Cafe’s fabled 82-foot-tall neon guitar.

Waller said that what it comes down to is, people recognize that neon’s worth far outweighs its cost and that it has a timeless appeal that outshines so-called progress.

“Neon signs say the name of the business without saying the name of the business,” reflected Waller. “A barber pole is an example—it doesn’t say barbershop, but when you look at it, you say, ‘That’s a barbershop.’ … It resonates immediately, making neon almost like a universal language.” •

This pink-tinted sign adorns the front of a seafood restaurant in Brookline, Mass.