1915-2015

1915-2015

100 years of the JAG building and its evolution of space and meaning

Editor:

Tracy Murinik

100 years of the JAG building and its evolution of space and meaning

Editor: Tracy Murinik

Published by the Johannesburg Art Gallery.

PO Box 30951, Braamfontein, 2017, Johannesburg, Republic of South Africa

T: +27 (0)11 725 3130 www.joburg.org.za

Sponsors: Friends of the Johannesburg Art Gallery.

With special thanks to Jack Ginsberg, Navin Mudaly, Marianne Fassler and Eben Keun. Sincere thanks also to Nigel Carman, and to David Krut Publishing.

Project director: Antoinette Murdoch

Editor: Tracy Murinik

Project team: Jacques Lange, Karuna Pillay

Contributing authors: David Andrew, Jo Burger, Jillian Carman, Julia Charlton, Reshma Chhiba, Natasha Christopher, Lorraine Deift, Bongi DhlomoMautloa, Nel Erasmus, John Fleetwood, Raimi Gbadamosi, Louis Grundlingh, Stephen Hobbs, Rochelle Keene, Clive Kellner, David Koloane, Dorothee Kreutzfeldt, Donna Kukama, Terry Kurgan, Same Mdluli, Antoinette Murdoch, Musha Neluheni, Nontobeko Ntombela, Jo Ractliffe,

Usha Seejarim, Christopher Till, Philippa van Straaten and Koulla Xinisteris.

Image researcher: Tara Weber

Research assistant: Karin Tan

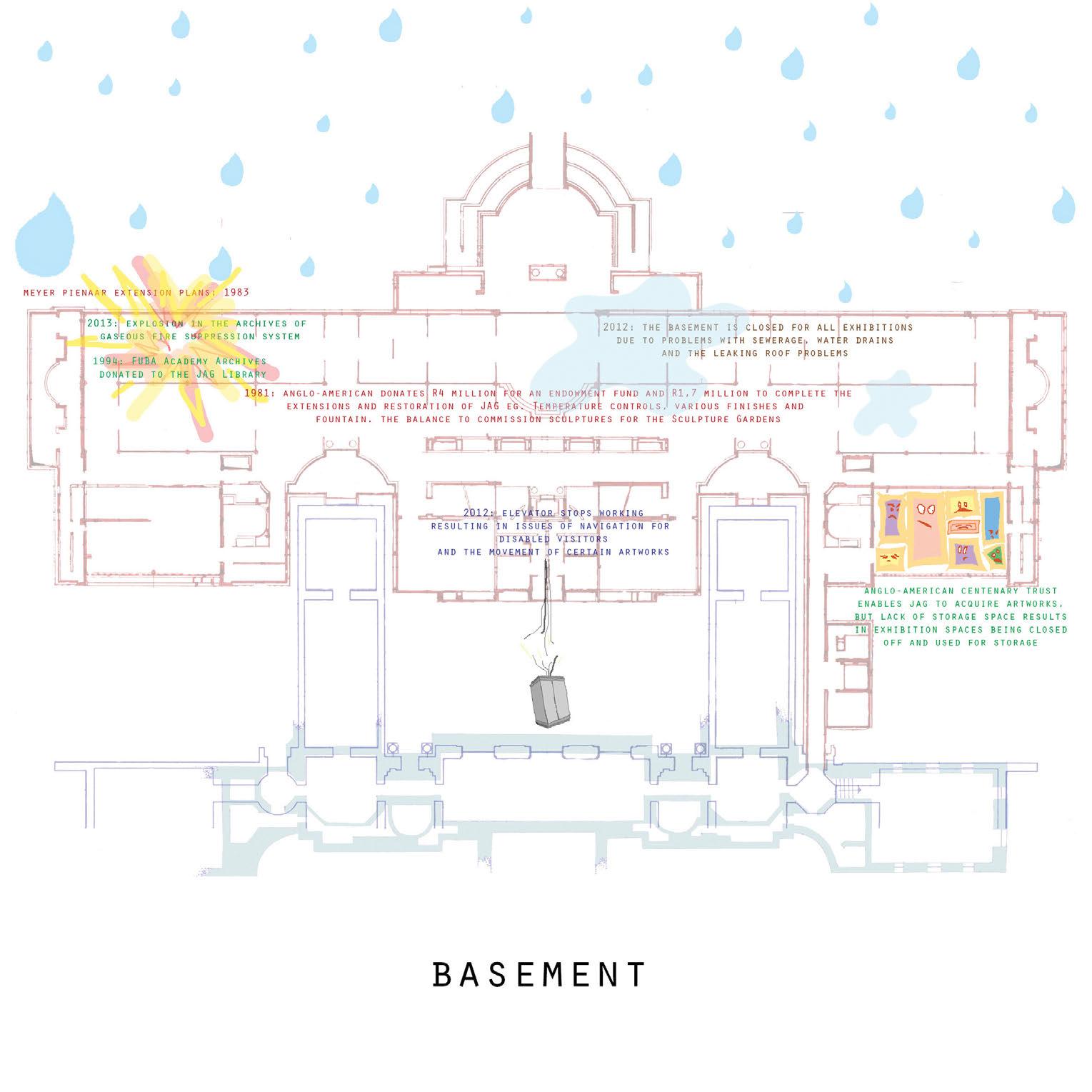

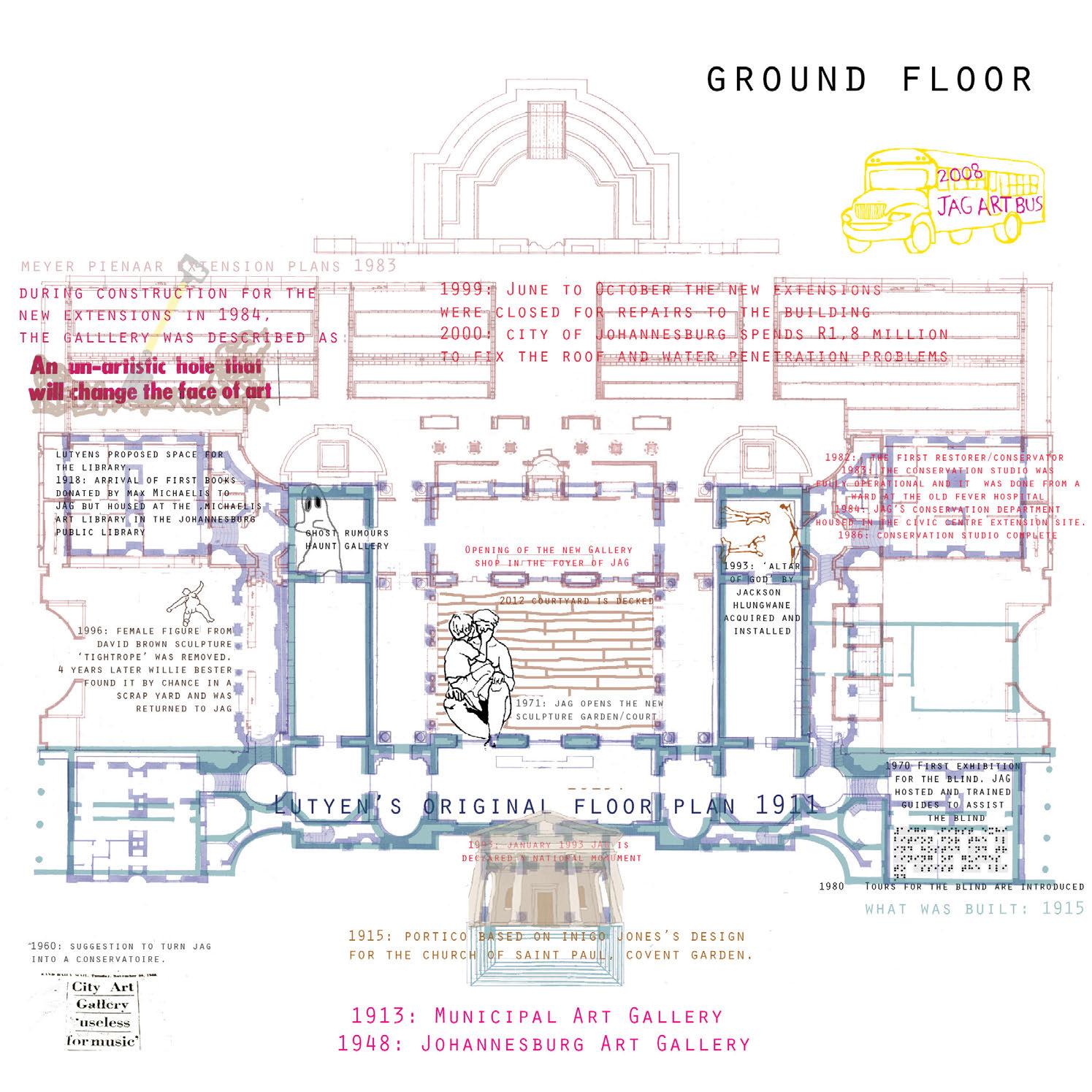

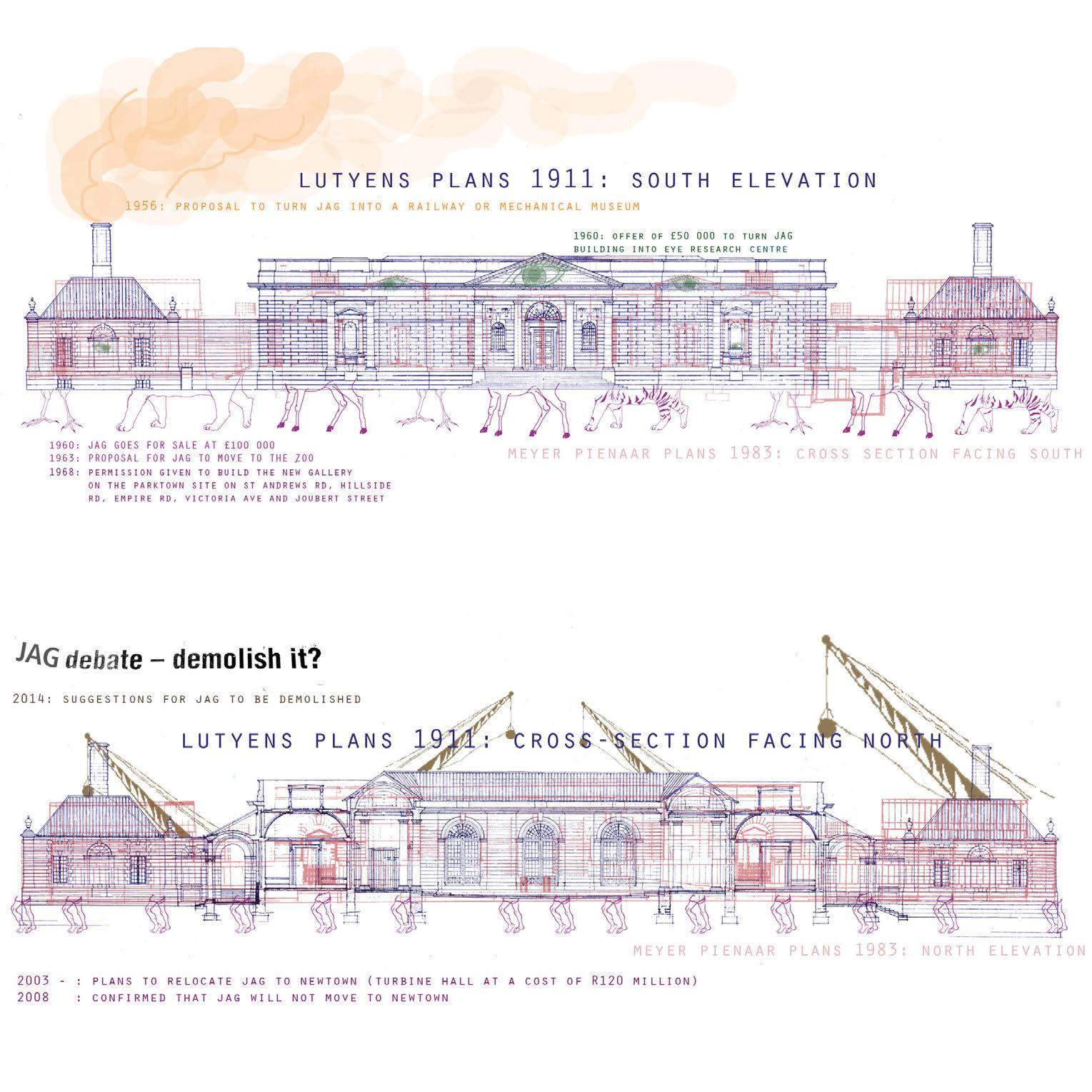

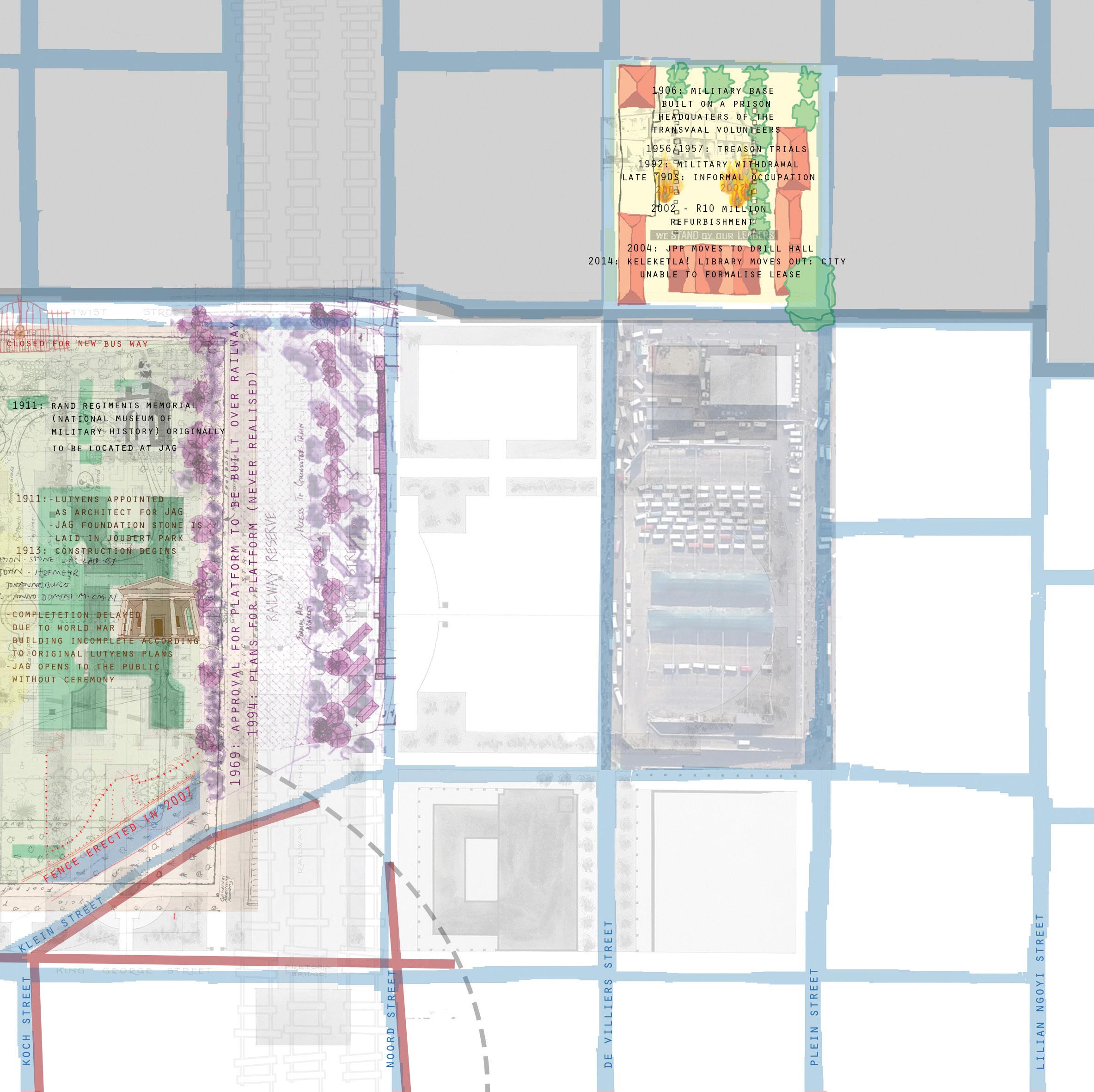

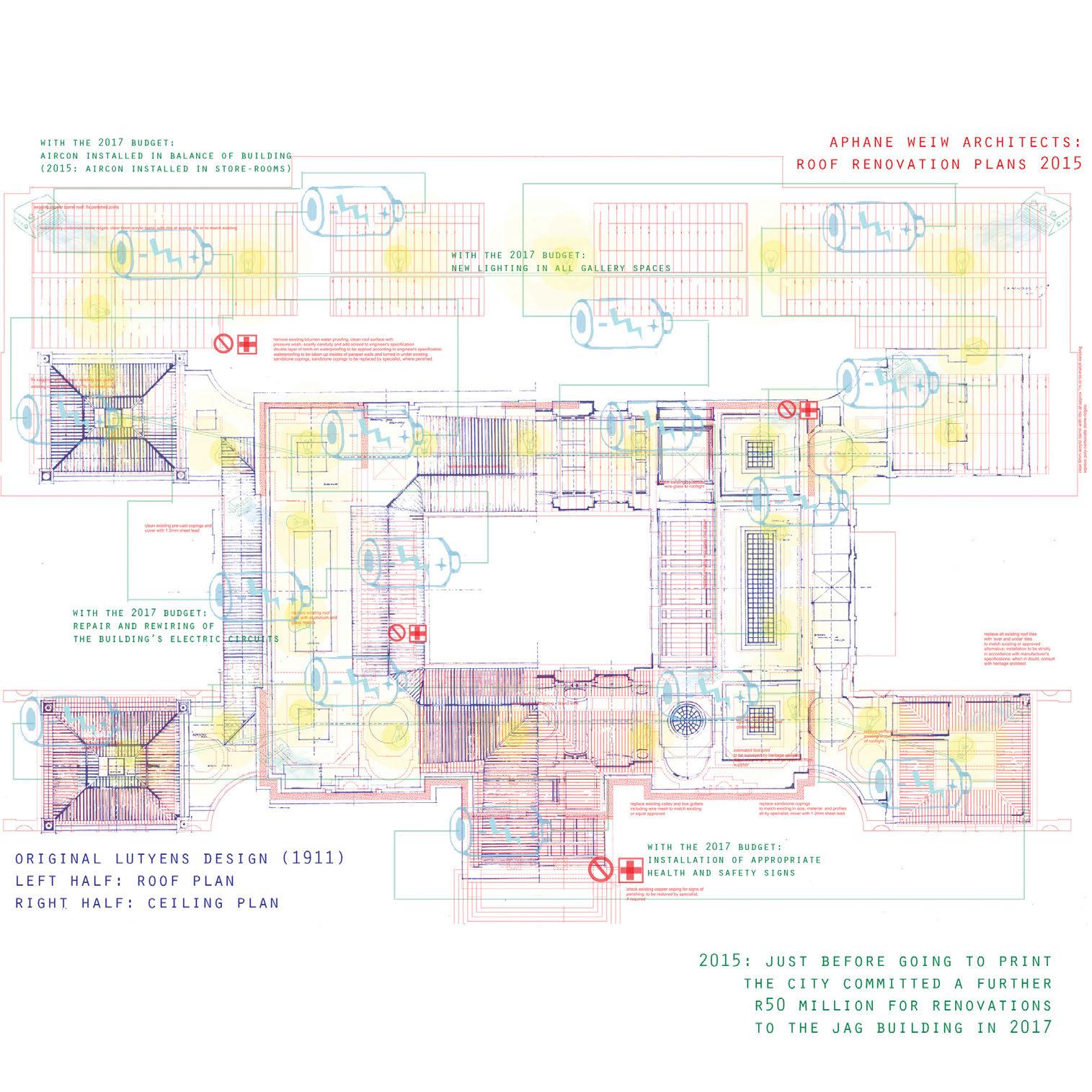

Interpretive graphic maps: Karin Tan

Photography: David Ceruti, with additional images by John Hodgkiss, and archival material.

John Hodgkiss (1966-2012) is fondly remembered and acknowledged on this occasion for his valuable contribution towards the documentation of the Gallery, its collections and exhibitions, which he so beautifully photographed over many years.

Sincere thanks to Wits Historical Papers and MuseumAfrica for use of additional archival images, resources and scanning.

Design: Bluprint Design

First published in 2015 on the occasion of the celebration of the centenary of the Johannesburg Art Gallery Lutyens building.

Copyright © 2015 Johannesburg Art Gallery

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording or any other information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing by the publisher and copyright owners.

Works of art reproduced in this publication have either been shown at, or are from the collection of the Johannesburg Art Gallery. All efforts were made to gain permission from the artists or copyright owners.

ISBN 978-0-620-68116-2

Curatorial as Education: A Few Notes on the Role of Education within the Context of a Museum

Nontobeko Ntombela

Timeline of JAG Directors and Chief Curators Over the Past Century

Lady Phillips and Lutyens' Mistress

Dorothee

Usha

Musha

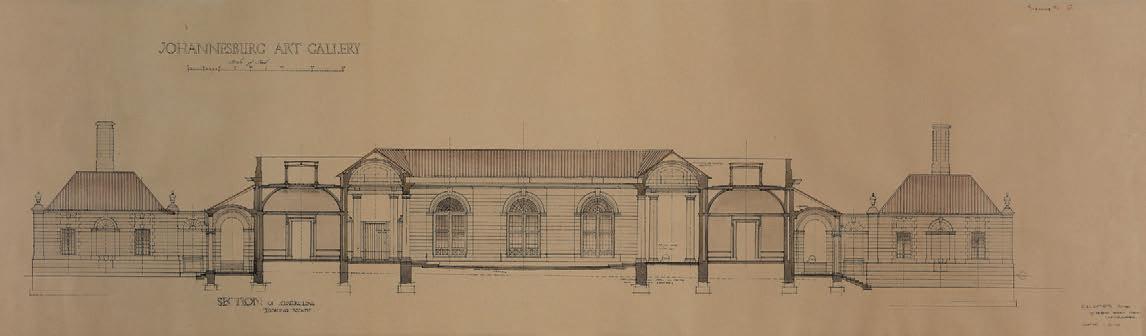

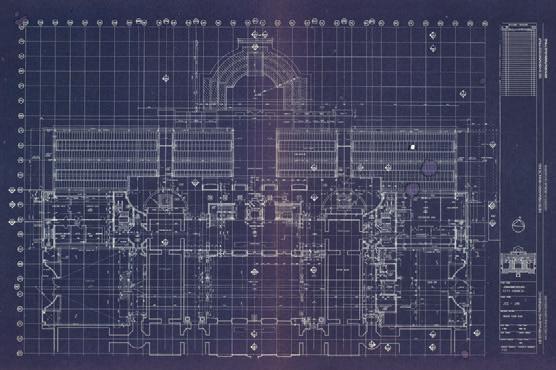

LEFT: Portrait of Sir Edwin Lutyens by Lawrence Josset (1935). TOP RIGHT: Lutyens’ Drawing No. 3, showing the south elevation of JAG, 1911. SECOND ROW RIGHT: Lutyens’ Drawing No. 6, showing the south elevation, 1911. ABOVE: The Lutyens building was declared a national monument in 1993. ©David Ceruti. THIRD ROW LEFT: Lutyens’ Drawing No. 1, showing the ground plan of JAG, 1911. THIRD ROW RIGHT: Lutyens’ proposed layout of Joubert Park and Union Ground spanning over the railway cutting. BOTTOM ROW LEFT AND RIGHT: Meyer Pienaar and Partners’ plans for the 1980s extensions, May 1983.

TOP ROW LEFT: Plaque in honour of Lady Phillips, unveiled in 1931. ©David Ceruti. TOP RIGHT: JAG façade floodlit for the celebration of Johannesburg’s Golden Jubilee, 1936. SECOND ROW LEFT: JAG building prior to 1939. SECOND ROW CENTRE: JAG building after 1939. SECOND ROW RIGHT: Construction view of the Meyer Pienaar extensions. THIRD ROW LEFT: Flower clock to the north side of JAG. THIRD ROW CENTRE: Meyer Pienaar architectural model. BOTTOM LEFT: ©David Ceruti’s panoramic façade matched proportionately to Lutyens’ original 1911 plans (2015).

TOP ROW LEFT: School group visiting the Gallery, 1971.

TOP ROW CENTRE: Van Riebeeck Festival Exhibition, 1952.

TOP ROW RIGHT: Holiday theatre workshop at the Gallery, 1978. SECOND ROW LEFT: School group in front of Anton van Wouw sculpture, date unknown. SECOND ROW CENTRE: Theatre workshop, 1978. Children posing as the painting Cuckoo! by John Everett Millais. SECOND ROW RIGHT: Holiday children’s workshop at the Gallery, with children imitating statues in the sculpture garden. THIRD ROW LEFT: Delton fashion campaign, ‘The art of dressing’ with models posing in front of Picasso’s Tête d’Arlequin. BOTTOM ROW LEFT: Walter Battiss in front of a Henry Moore sculpture. BOTTOM ROW CENTRE: Bongi Dhlomo-Mautloa, member of the Art Gallery Committee.

During the last six-and-a-half years I have had the opportunity to manage not one, but two centenary celebrations at the Johannesburg Art Gallery. The first was the centenary of the Gallery’s Foundation Collection, celebrated on 29 November 2010. In what was perhaps an indication of the City’s (and the country’s) priorities of the time – namely South Africa’s staging of the FIFA World Cup – Joubert Park happened then to be clean, neat and green, with working fountains and some of its former glory restored. At JAG itself, an influx of international visitors could be gauged through entries in our visitors’ books, and all was swathed in excitement and optimism. The book we released to coincide with the celebrations documented the event and collection handsomely.

This year marks the second centenary in my time at JAG, that of the magnificent Lutyens building, on 20 November 2015. This edifice was built especially to house the Foundation Collection, put together by Sir Hugh Lane. The events that have been organised around this auspicious occasion include a total of six exhibitions, a variety of ancillary programmes, and this commemorative investigation of the history and role of JAG over the last hundred years.

The six exhibitions cover a wide range of historical periods, through various media, and showcase the incredible work contained in the Gallery’s holdings. A feature of this powerful and impressive programme is the breadth of artists it represents, as well as the historical and aesthetic importance

of their works on show as acquired by the many astute JAG curators over the years.

A celebration of this nature must also acknowledge some of the people who have been influential for me in a personal and professional capacity.

I would like to thank Jo Burger, my JAG mother, and one of the country’s most brilliant librarians. She is my friend and my support. I have been able to cry on her shoulder and share ideas for the last six-and-a-half years; but she has also helped many more people – artists, researchers, writers – for a lot longer than that, in her capacity as custodian of the JAG Archives.

During the compilation of information for this book, Jo has been suffering from a severe hip problem. Yet, it is typical of her qualities as a person that she stayed on her feet and went out of her way to help all the researchers.

To the rest of my staff, especially Musha Neluheni, Tara Weber and Philippa van Straaten, who all have their hearts in it, with a great passion for JAG and their work here, I would like to thank them for going the extra mile. Tara’s contribution in sourcing images and captions for the book has been invaluable.

Stephen Hobbs deserves a special mention, despite not being officially attached to JAG. While also being a sympathetic ally for me, he designed and staged an exhibition, JAG/SNAG, which drew the attention of the Section 79 Committee to some of the staff vacancies at the Gallery that urgently needed to be filled.

Thanks are also due to Alba Letts, then Deputy Director of Arts and Culture, for her institutional support, which is detailed in my Vision Statement (pp 178-9).

There are other groups and people in the wider JAG family who have made important contributions over the years. These include the JAG Art Gallery Committee, as well as the restructured Friends of JAG organisation, often spearheaded by the wonderful Marianne Fassler, for their wonderful work done to raise money and awareness for the Gallery. In recent times Eben Keun has added marketing and social media expertise to our efforts to keep the Old Lady afloat.

A vital part of the Centenary celebrations for the Gallery is this book itself. Constructure was, from the beginning, meant as both an historical overview of the Lutyens building and the development of the extended Gallery space, as well as a critical and theoretical investigation of the institution of the Gallery, its rationale for existing and its curatorial approaches over the years. The book engages freely with all of the very current debates around institutional memorials

and monuments in South Africa, and engages also with the idea of a colonial history, which I have certainly attempted, in my time at JAG, to engage with critically, and to call into question through staging oppositional art and discourses within the institution itself. There are thus sections in the book that deal with an historical overview of the institution, a section on critically engaging with the physical context of the Gallery’s surroundings and the changing social nature of the space; an overview of key exhibitions; and a closing section looking to the future and the ongoing space that JAG will continue to fill in the city’s identity. I‘d like to thank Tracy Murinik for her efforts in pulling together the book as editor, to Jacques Lange for his thoughtful and beautiful design, and all the contributors for their thinking and engagement.

Lastly, on a personal note, being head of JAG is onerous, not least because it is a key space for contestation about the nature of cultural history and identity in Johannesburg and, symbolically, in South Africa too. I could not have made it, or even lived and breathed, were it not for my two daughters, Zoey and Mia.

Antoinette Murdoch is the Chief Curator and Head of the Johannesburg Art Gallery (since 2009), and an artist. She hold a Masters in Fine Art degree from the University of the Witwatersrand. Formerly the CEO of the Joburg Art Bank, she also serves on the South African Museums Association (SAMA) North Committee. In December 2013, she was named one of the top 50 Movers & Shakers of the South African Art World by Art Times magazine.

Tracy Murinik, Editor

Before a building exists as a structure, it exists as a series of ideas – a confluence of needs, desires, imaginings, beliefs and intentions expressed by those who commission the project, combined with those of the architect/s and contractors that develop the project into something that physically exists. Embedded in these expressions, from both sides – and through the evolution of concept to material form –are distinguishing traces of who all those individuals are – the ethos of their time period, their identities and identifications – aesthetic, ideological. As much as buildings are physical demarcations of space, defining their edges, again aesthetically, conceptually, often socio-politically; they are also containers and passages – for those (and those objects) who live, work, or exist there; and for those (and those objects) that visit or make their way through them. Each of these moments – of everything that ever happens in and around a building; of anyone that ever enters or exits it – becomes part of that building’s history, and of its accumulated meaning.

So setting out to tell the story of a building that has stood for a hundred years is a complex undertaking, as ultimately that narrative does not exist in the singular. There are many stories, and not all of them may be told here. This book sets out to tell some of those stories – selectively, of course, as is inevitable; since the act of conceptualising, compiling, editing and designing to bring about a publication is similarly invested with the intentions and expressions of those who work on it, and the choices they make. In this instance, there has been a very considered process that has been followed to reach these final selections, from an initial directive and brief, to a process of interpretation, consultation and an accumulation of ideas and positions that seek to represent a complex range of narratives that in their own particular moments represent aspects of the myriad narratives that exist; and that together, and in relation to one another, provide a broad and complex context both of Johannesburg, and of the Johannesburg Art Gallery’s century-long existence. As selected moments, they nevertheless provide eloquent voice to a number of positions that are part of the narratives that represent a long history of investment in what the Gallery is, means, and sets out to be and do.

The neologism: ‘constructure’, presented itself as a means to stress this complexity; to draw attention to the often

misconstrued perception of a built space being a simply benign vessel for whatever happens to take place inside it; to acknowledge that every aspect of a built space is a multidimensional construct, and where the construction of that space may be read beyond the fact of the building and its legacy to include a history of its surrounding context, its patrons and its audiences. A space is always in the process of being made meaningful, through whoever inhabits it and directs its functions or informs its meanings at a particular time.

The early history of, and just predating, JAG is fascinatingly described in the first section of this volume by Louis Grundlingh (pp 34-43), who explores the context of Johannesburg at that point in time, and specifically of how Joubert Park became a key leisure site in the young city and was a “significant spatial marker” of changes to Johannesburg’s developing sense of identity, especially after the South African War when governance shifted from the ZAR to a British governmental system. Grundlingh traces the aesthetic and aspirational impact that this had on the City Council, and the steps they took to “create and give material form to Victorian and Edwardian concepts of identity, class and ‘respectability’”, decisions that ultimately shaped the “civic and cultural life of [the already] class- and racially divided city”.

Jillian Carman, in detailing the architectural history and development of JAG’s original Lutyens building in Joubert Park (pp 16-33), which opened in November 1915, similarly provides clues of the underlying desires and ‘internationalist’ aspirations that enabled Florence Phillips, her Randlord husband, Lionel Phillips, Anglo-Irish curator, Hugh Lane, together with other Johannesburg Randlords, and the City’s mayor, to drive the construction of the art gallery, and to make the selection of Edwin Lutyens as its architect, despite huge local opposition to his appointment. Carman importantly describes Lutyens’ personal motivations for finally taking on the project, which included his eagerness to intervene in such a young city (Johannesburg then not yet 30 years in the making), not only in terms of designing a museum, but with a view to substantially envisioning plans for its surrounding areas as well – thereby extending his reach into the city’s spatial planning – including Joubert Park, and then traversing the railway line further south into the city. Carman mentions the concept of the ‘City Beautiful’ – an international movement of that time – which Lutyens keenly followed, and which shaped his visions for the development of that part of the city, again through looking to emulate classical features of Europe into this developing “New Country”. The implications of these desires and aspirations inform the beginnings of JAG’s story, contextualising its establishment as a part of a colonial project and vision, as well as fulfilling the desires and personal motivations of the various people involved. These positions also inform the starting point of the city’s inhabitants’ engagement with this building. These histories remain relevant to the reading of JAG as an institution, still.

The second section of Constructure provides a vast overview of all of the exhibitions ever hosted at JAG over a hundred years – an intriguing narrative in its own right of the shifting focus, representation and activities of JAG over a century. This section also features more detailed texts and information on selected seminal exhibitions, especially over the past 30 years, that critically consider and demonstrate shifts in JAG’s exhibitions and collecting policies over these years, and additionally speak to shifts in concepts of curatorial roles over this period, towards exhibition-making as a self-consciously authorial act – of exhibition ‘as text’, as Kellner describes in his essay (pp 96-100); or entering into areas of political redress and revision, such as Same Mdluli (pp 90-93) explores in her essay on TheNeglectedTradition: TowardsaNewHistoryofSouthAfricanArt(1930-1988), where she argues the significance of that groundbreaking exhibition as being not only about “reparation of an imbalanced historical account”, but critically “as ‘a catalyst’ for further investigation on some of the artists it featured”.

The third section, ‘New Engagements’, takes its cue from observations such as Mdluli’s, in that it looks to JAG’s contemporary strategies and responsibilities of making itself relevant – both in terms of its collections and exhibitions policies, and critically in terms of engaging its physical position in the inner city – in relation to Joubert Park, the area’s daily residents, its audiences (existing, once-existing, and still desired) and its self-definition as a museum and cultural educational institution in post-apartheid South Africa. ‘New Engagements’ considers several key projects over the past fifteen or so years that, both from within JAG, as well as externally through members of the arts community, have worked to consider ways of shifting the awkward and in

many ways unrealised potential of the relationship between JAG and Joubert Park and its surrounds. Also critically considered here is the question of JAG’s role as a space of education, which Nontobeko Ntombela (pp 130-143) incisively poses. Ntombela considers the need for education to be “an active tool towards addressing issues of past imbalances through the museum’s collecting and display strategies”, and for education to be a central facet of curatorial production within the museum context. Pointing out that an institution like JAG “remains a paradox in a place that is fast rejecting its relevance and reasons for existing (whether politically, financially or ideologically”, she asks the question, “how can art collections help us pose questions of new histories and new modalities of display towards better serving its increasingly complex society?” and proposes that “given the shift in artistic and curatorial practices, the role of education within art collections has equally needed to change in order to challenge complexities, contradictions and burdens of cultural, political and social histories carried by these institutions”.

Constructure’s last section speaks to the changing institutional vision for JAG over the years. To begin with, it includes commentaries by five of the six JAG directors/chief curators who have steered JAG since the 1960s, as well as texts by current and previous members of the Johannesburg Art Gallery Committee. It then continues into an edited transcript of a frank conversation (pp 186-193) held amongst several members of the Johannesburg arts community who are, or have been, somehow involved with or invested in the practices of JAG over the years. The conversation was held in acknowledgement of the fact that JAG in many ways is, and always has been a contradictory space – built and

having evolved in an ideologically contradictory and violent city and country, to mean contradictory things to various inhabitants of the city over the past century – despite many engaged and successful moments in the Gallery, especially over the past two to three decades, that have purposefully challenged those contradictions. The conversation was intended to propose solutions to JAG’s challenges, and revolved around developing a type of collective vision going forward for the Gallery; and of how to consider possibilities that transform this space into something that finds meaning with a greater constituency of the city on a sustained basis; to rethink what the model of a museum might be in South Africa – that is structurally and functionally relevant, as Donna Kukama offered in this discussion. Also acknowledged in this session was that in spite of standing for a hundred years, JAG’s sustained existence has never, in fact, been a given (since its very early years there have been repeated plans to sell, move or close the Gallery), and nor is it now. As has been the case recently of questioning the implications of some historical (especially colonial) structures, and their sustained ideologically imprinted connotations, through calls and activist movements such as #rhodesmustfall, there have been similar intimations around the possible fate of institutions like JAG. To date, however, JAG is a space that, although contested, has not been allowed to die for a hundred years.

Included in the front of this book are wonderful interpretive architectural plan overlays by Karin Tan, who visually and graphically plots the structural and contextual shifts historically to the JAG building and its surrounding areas. On pages vi-vii is a seemingly light and quirky interpretive intervention onto one of the earliest surviving plan drawings

of Joubert Park, onto which the Gallery and other surrounding locations are marked, but which include quite searing moments of context, such as JAG’s proximity to the Drill Hall, for example, where the Treason Trial took place just up the road in 1956, while JAG continued to function as it always had; and the inclusion of the prettily plotted reference to Artists Under the Sun on the Park lawns – that David Koloane refers to in his essay (pp 182-184) – which was an ingenious play of activism and professional ingenuity by some black artists, beginning in the 1960s, who showed and sold their work in the Park, directly in front of the municipal gallery that mostly ignored their existence.

Amongst the interpretive maps at the front of this book are also two whimsical takes (see pg v) on JAG’s existential irony that reference several of the suggestions over the years for JAG to move elsewhere – one has the Lutyens building develop an assortment of animal legs, as it begins to make its way towards the zoo; while the other, haunted by lurking giant construction cranes overhead, appears to get the message and starts to makes its way on human legs towards Newtown, where the Turbine Hall was once a potential relocation site for the Gallery.

The rather bizarre joke of this solid historical monument never, in fact, being particularly secure – structurally, geographically, financially, or ideologically – is ironically, I feel, perhaps one of its most promising features as we look beyond this centenary. For, if JAG is able to commit to ongoing flexibility, at all levels, then with every positive thing that it already has going for it – its extraordinary art collections, beautiful spaces, and the desire by so many arts interested citizens still for it to continue its transformation

into a space that is open, self-sustained, and of value to continue learning from and experiencing, with relevance to broad-ranging audiences – then JAG will have every reason and relevance to continue its life in this city, with a wealth of potential to teach us our history, to creatively engage our present, and – as one of those who believes in what such creative realms can offer – to transform our city’s future, or at least some of the ways in which it is able to reflect back upon itself and the world it exists in.

Tracy Murinik is an independent art writer, curator, editor and occasional filmmaker based in Johannesburg. She has written, published and edited extensively on contemporary art from South Africa and the continent.

Construction of the Art Gallery, 1913.

“Middle class refinement at the turn of the century included admiration for music, nature, art, a library, a museum and facilities for horticultural displays. Citizenship and respectability were, after all, intimately entwined with cultural beliefs … Joubert Park … was meant to be more than a ‘beautiful garden’ ... The Park shared – in an integrated way – its landscape with the bandstand, conservatory, and the Art Gallery, and even included plans for a memorial site and an amphitheatre. The city fathers believed that these structures would become the showcase for the city, more or less similar to what the Smithsonian Institute is for Washington DC, as the USA’s capital.”

Louis Grundlingh (p 38)

“The founding of the Johannesburg Art Gallery can be linked to the ambitions … to assert the superiority of British culture, to consolidate the cultural infrastructure of an emerging civil society and to demonstrate the commitment of the typical British tradition of philanthropy.”

Louis Grundlingh (p 39)

Jillian Carman

When Edwin Lutyens received a telegram from Hugh Lane 12 October 1910 (NL 5073) asking him to come to Johannesburg to design an art gallery, he declined, although it “gave me a most exciting turn”. Undeterred, Lane sent a second telegram a couple of weeks later to Rome, where Lutyens was planning the British Pavilion for Rome’s International Exhibition of 1911. This time Lord Curzon and the British Ambassador, Sir Rennell Rodd, persuaded him to accept. He immediately booked a cabin on the Saxon, departing 19 November, “& here I am [back in London] tearing about & working all night to get clear & away” (2 November 1910, NL 5073).

This seizing of opportunity and impulsive decision-making is typical of how the Johannesburg Art Gallery (JAG) came about, both in the creation of its collection (1909-10) and of the building which came to house it (1915). Florence Phillips,1 wife of Randlord Lionel Phillips, was the principal driver of the project. Hugh Lane, an Anglo-Irish art dealer, became her willing conspirator. Chance encounters and quick, possibly rash, but ultimately brilliant decisions happened in a unique space in time that was unencumbered by obligations to committees, wider consultation and due process. These obligatory restraints may have emerged pretty quickly, especially with regard to the collection’s building and the official appointment of Lutyens, but in the meantime Lane, enabled by Florence, and using funds from mineowners, operated as a fairly free agent-curator, whose decision to approach Lutyens as architect was endorsed by

his close circle of acquaintances and was unchallenged at the time. The result was an extraordinary collection within a unique building, Lutyens’ only museum in a long and illustrious career. But it nearly didn’t happen. In a cliff-hanger way typical of JAG’s founding, the publicly unpopular choice of Lutyens as architect would not have been approved at a “lively” council meeting of 26 April 1911 were it not for the mayor’s casting vote (RandDailyMail, 27 April 1911). Dublin, whose gallery of modern art had also been founded by Lane (1908), was less fortunate. Lane’s choice of Lutyens as architect was refused by the Dublin Corporation in April 1913 (Dawson 1993:24-27).

The decision to found a gallery of modern art in Johannesburg was made spontaneously by Florence and Lane when they met in April 1909 and bought the first three paintings for the collection. Florence, in fact, was in England to source items for an arts and crafts exhibition proposed by the Johannesburg branch of the South African National Union (SANU). A permanent collection of educational items was a hoped-for outcome, not a gallery of modern art, which was certainly not part of the SANU project. The background story is given in Gutsche (1966), Carman (2006) and One HundredYearsofCollecting (2010), JAG’s book to celebrate the opening of the collection in temporary premises on 29 November 1910. Constructure celebrates the centenary of the opening of JAG’s permanent Lutyens home in Joubert Park in November 1915. Though the building is the focus, collections, exhibitions, activities, civic life, historic contexts

and more are inextricably bound with it, and are explored in other parts of the book. In this chapter, I focus on the Lutyens building and the stages of its construction, with a brief mention of the Meyer Pienaar and Partners 1986 extensions.

The story of a home for the collection is long, complicated and without a neat ending. The first home was temporary: the South African School of Mines and Technology, where the collection opened on 29 November 1910. (Fig 1) It remained here until it was moved into “the portion of the [Lutyens] building that has been erected” (council minutes, 21 Sept 1915), opening without ceremony in November 1915 (McTeague 1984:143). The building was incomplete and remained so, even when two Lutyens-designed wings, extending to the east and west along the southern railway side, opened in 1940. It was still unfinished until 1986 when the Meyer Pienaar extensions opened, a metaphorical completion of Lutyens’ original intentions in the way their design closed the inner courtyard with a north wing, and balanced the 1940 extensions with wings to the west and east along the northern park side. Unfortunately, after nearly 30 years, the Meyer Pienaar extensions have developed into a troubled and incomplete space. But despite the grave structural problems, this can be considered an advantage, lending possibilities for experimentation, which a finite building would have curtailed. Exciting projects associated with the space are discussed elsewhere in this book.

The Randlords were initially reluctant to commit funds to a museum which did not yet have a home. The mine-owner Otto Beit, for example, a major early supporter of the project, emphasised the importance of prior accommodation. Lane, lamenting the lack of forthcoming funds, wrote to Florence in November 1909: “Mr Beit I think is determined not to spend anything till the conditions he made are complied with” (JAG, Hunt Collection). But this did not stop the two from disingenuously announcing in The African World, 9 October 1909, and elsewhere, that Jan Smuts (Transvaal minister of education and colonial secretary) and Louis Botha (Transvaal premier) had agreed to find accommodation for the collection during their visit to England, July to August 1909 (Carman 2006:147-150). This seems to have been no more than a ploy to get reluctant Randlords, specifically Otto Beit, to commit funds to the proposed gallery.

Finding accommodation, or at least the promise of a municipally funded building in a public space, was crucial, and Lionel took the lead on his return to Johannesburg from England in late 1909. He had his own agenda in desperately wanting the JAG project to succeed. He was so far the only Randlord who had committed money to what probably seemed a dodgy plan, and he could not afford to carry it alone. He was far less wealthy than his mining colleagues, and was considered by management to be over-lavish and careless with his personal finances, not helped by his impulsive wife (who admitted she had no idea about money), nor by her collaboration with an art dealer who was probably on the make.

Lionel proposed a bizarre solution to a seemingly intractable problem: combining two projects with which he was engaged, JAG and the Rand Regiments Memorial (RRM). The latter, coordinated by the RRM Committee, aimed to build a memorial to the Anglo-regiments on the Rand who had

died in the South African War of 1899-1902. Like the JAG project, the RRM Committee was seeking a site. Unlike JAG, it had start-up funds for a building. Lionel and the chair of the RRM Committee, proposed at a council meeting, 30 December 1909, that the already-advanced project for the RRM, and the more recent project of an art gallery, should be combined and that the memorial, while retaining its commemorative nature outside, should accommodate an art gallery inside. Fortunately this did not come to fruition, and negotiations for accommodation continued. Finally, a commitment was made. At a council meeting of 1 June 1910, temporary accommodation at the South African School of Mines and Technology was offered, and

council agreed to match a donation from the government for the purpose of building an art gallery. Shortly afterwards a management committee in charge of the gallery project was put in place, comprising Florence, Howard Pim, Harry Hofmeyr (as representative of the Johannesburg town council) and FV Englenburg (asked by Smuts to represent the government).2 Unfortunately, no records of their deliberations have survived.

After voting money towards a building, the council thereafter showed an almost paralytic indifference, apart from agreeing to a site on the southern side of Joubert Park and deciding not to pursue a plan to cover the railway cutting

to the south (council minutes, 15 August 1910). If there was a public debate about the appointment of an architect at this time, or the holding of an architectural competition (as some authors have claimed), there is no official record.

The Association of Transvaal Architects apparently sent a letter in August 1910 to the council with reference to the proposed erection of an art gallery. This was referred to the Art Gallery Management Committee and there is no further information about it. When the draft deed of trust was tabled at council on 25 October 1910, the minutes noted that council was “about to erect and provide a building to be used and employed as an Art Gallery and Museum of Industrial Art ... and for other purposes” and that the temporary accommodation was due to be vacated in early 1911. There are no further details.

At a meeting in November, by which time Lutyens was already aboard the Saxon en route to South Africa, with the lure of the art gallery and a number of other commissions, the town engineer suggested that his department draw up plans for the art gallery building for submission to Lane. This was not agreed to. The motion that designs for the art gallery should be invited from architects other than Lutyens was defeated at a council meeting of 12 December 1910, attended by Lane and Florence, but not by Lutyens, by now in Johannesburg, who wrote to his wife “there seems to be a good deal of opposition on the Municipal Council to anything being done by anybody but a Johannesburg Architect” (12 Dec 1910, RIBA, Lutyens papers). It was resolved at this meeting that a sub-committee be appointed to confer with Lutyens around the design for the art gallery building and layout, with power to act.

Lutyens seems to have irritated a number of people during his three weeks in Johannesburg with his irreverent, often

puerile humour, and his insensitive pontifications on local architecture (Ridley 2003:199). He asked Howard Pim, a supporter of the gallery project, if he had any ‘Pimples’, and must have infuriated local architects with an interview in which he gave his “impressions of our work, his advice about the directions of its development, and his criticisms of our aims and aspirations”, implying that South Africa is doing rather well, but could do far better, and “should give birth to a school of architects in the future to equal any that has been built in the past” (RandDailyMail, 21 December 1910). Trouble was already brewing, and came to a head in early 1911. The municipal council’s general inactivity in response to the Association of Transvaal Architects’ complaints hardly helped. A protest meeting in February 1911, acrimonious exchanges of letters in the press, council meetings – all attest to the opposition to the appointment of a foreign architect, the fact that there was no competition, and the deception of the donors who now claimed that a condition of their gift was the appointment of an architect of their choice (Carman 2006:243-252). As mentioned at the beginning, Lutyens was officially appointed only because the mayor used his casting vote to support the decision – and because it had been agreed that a local architect, Robert Howden, would supervise the building plans, with Herbert Baker as honorary advisor (McTeague 1984:143).

Lutyens had in effect already got the job in December 1910 from his circle of supporters when he was in Johannesburg. While there, he worked on preliminary designs for JAG and the RRM, sharing his ideas with Herbert Baker. His proposals were adopted by both the Gallery and Memorial Committees (Hussey 1989:208-210). He probably worked further on his designs during the nearly three weeks voyage back to England. Intriguingly, Hugh Lane returned to England on the same ship, which departed from Cape Town on 28 December 1910, but there is no surviving evidence that they

discussed the Gallery plans, although they are most likely to have done so (Gutsche 1966:164).

In Johannesburg, Lutyens closely examined the sites for the two buildings: Joubert Park for JAG, and “a piece of ground north of the Zoo as a site for the Rand Regiments Memorial” (council minutes, 5 March 1912, referring to an earlier resolution of 25 October 1910). In his daily diary-like letters to his wife during December, Lutyens frequently mentions going to Joubert Park, the RRM Eckstein Park site “where the Duke of “Cannot” [Connaught] laid a foundation stone [30 November 1910] in an impossible place”, discussions with an archdeacon about a church and its “new site [which is] far better & works in with my picture gallery etc. so as to make a bit a [of?] town planning on a big scale”. He describes having a chance at a dinner party “of giving my real views on town planning & the real opportunity ... here with a 26 yr. old city” and comments “I must get the designs made [?] before I go for the following its extensions, the laying out of Joubert Park & a wide bridge across the Railway & connect the ... ground with it” (12-18 December 1910, RIBA Lutyens letters). His interest in town planning is evident, as noted in an interview in the Rand Daily Mail, 21 December 1910, headlined “Making a city – How to beautify Johannesburg ...”, where there is brief mention of his town planning work in England, such as at Hampstead Garden Suburb.

Lutyens attended to the plans for the RRM more promptly than he did JAG’s plans, and the memorial was completed towards the end of 1913. Its position on a raised promontory complemented Lutyens’ design of five long vistas radiating out from the RRM, a dramatic feature which has been preserved until today (Keene 1986:84). Despite the different purpose of the memorial, and that it was not an enclosed space (once the idea of housing an art gallery

inside it had been discarded), there are some structural similarities between it and JAG. (Fig 2) For example, the smaller side arches on the RRM are remarkably similar to the arches on the square sides of the JAG portico, with a keystone at the apex and an architrave connecting the base of the arches on either side of the square piers. But a key similarity is the lay-out – the town planning – of which the buildings are a part. Unfortunately, apart from the RRM vistas, Lutyens’ plan for the RRM of balustrades, plinths with sculpture, and steps leading to the main archways, was discarded in the final realisation. JAG was also to have a defined context with the building as the focal point of a large and elaborate park, extending over the railway cutting and into the old Union Grounds to the south (see pgs vi-vii). But the design was not implemented, the plan to bridge over the railway cutting was never realised, and the cutting remains uncovered to this day. The surviving design, however, is of great importance in that it documents a growing movement of which Lutyens was a participant – the concept of the ‘City Beautiful’. Mervyn Miller (2002) describes the Joubert Park design in terms of the City Beautiful international movement of that time. He cites as a landmark in British civic design the Royal Institute of British Architects’ International Town Planning Conference of 10-15 October 1910, which Lutyens attended and where Baker displayed his Union Buildings plan. He believes the City Beautiful displays, particularly Daniel Burnham’s plans for Washington and Chicago, “opened Lutyens’s eyes to the power of the Grand Plan” and that this surely created, in Lutyens’ mind at least, “a broad agenda for his forthcoming work in Johannesburg.” (Miller 2002:164).

Lutyens had been working in this idiom for some time, though mainly on a domestic scale in collaboration with the garden designer Gertrude Jekyll, with the house being integral with its garden surrounds (Miller 2006:117-119). In

1906 he became involved in one of the leading garden city projects of the time, Hampstead Garden Suburb, for which he produced plans for the central square and designed St Jude’s Church and the Free Church, shortly before and during his involvement with JAG (Miller 2006:117-137) .

Miller (2002:165-66) analyses in detail Lutyens’ designs for Joubert Park and the Union Ground beyond the bridge over the cutting. Lutyens planned the resiting and redesigning of St Mary’s Cathedral as part of the Union Grounds, hence the many meetings with the archdeacon described in his letters to his wife. Despite intense lobbying, he did not get the commission. For years the sketches for the church (Miller 2002:Fig 7) were not identified with Lutyens’ Johannesburg park designs, until Miller made the discovery some years back.3

After he was officially appointed, Lutyens’ designs for JAG seem to have languished, to the concern of those back in Johannesburg. He finally supplied foundation plans (see pg 5) just in time for the laying of the foundation stone on 11 October 1911 by the mayor, HJ Hofmeyr. Today the stone is at the north entrance of JAG, moved here during the Meyer Pienaar extensions of 1986. Its weathered sandstone inscription and vandalism have rendered it virtually illegible. (Figs 3, 4)

The working drawings, which Joseph [JM] Solomon evidently helped to complete when he joined Lutyens’s office, only arrived two months later. During 1912 the drawings were adjusted with a view to tendering for certain sections that could be completed sequentially. Council, at its meeting of 17 July 1912, approved proceeding with the erection of only a portion of the Gallery, and asked for tenders. At

its meeting of 18 February 1913, council approved the tender of A Gill for erecting the building in in Elands River stone, and a contract was finally signed on 20 February 1913 to build part of Lutyens’s original plan: the large south gallery, with wings extending northwards on the east and west sides (Carman 2006:251). (Fig 5-7)

After various delays the collaborating architect, Robert Howden, reported to council on 21 September 1915 that the contractor had completed “the portion of the building that has been erected” at a total cost of £48,682.13s. The artworks were moved from the South African School of Mines and Technology to the new building during October 1915, and shortly thereafter opened to the public. Florence declined the mayor’s invitation of 13 October 1915 to open the collection, setting out her reasons in a letter that she forwarded to the press for publication. The council, she alleged, had not fulfilled its obligations, despite repeated requests from the Art Gallery Committee. It had refused to

upgrade the post of curator from a temporary part-time one, to a permanent one with adequate salary and a suitable man in the position. It had refused to delay the opening until a large number of items, at present stored at the Tate in London, had arrived. The Museum of Industrial Art had not been realised. The art school had survived thus far through private generosity. And, against the architect’s wishes, the new building had been constructed in expensive stone instead of plaster and cement, with the result that there were no funds to finish it and “many of the objects for which it was designed will not be fulfilled” (Carman 2006:251).

Lutyens’ South African venture is often seen as a light interlude, almost an amusement, during a major career that spanned New Delhi, Britain, Europe and Washington. The two Johannesburg projects were small-scaled compared to Lutyens’ other magnificent public buildings and memorials, and the impulsive South African visit suggests an air of levity. But both structures are seminal in Lutyens’ career. The RRM

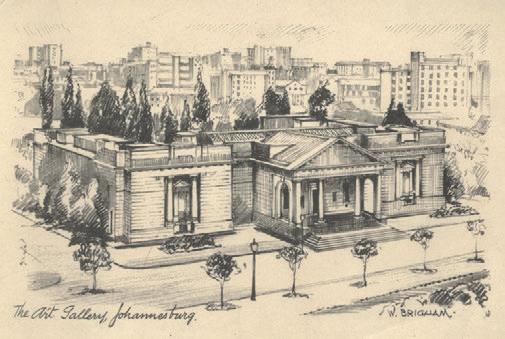

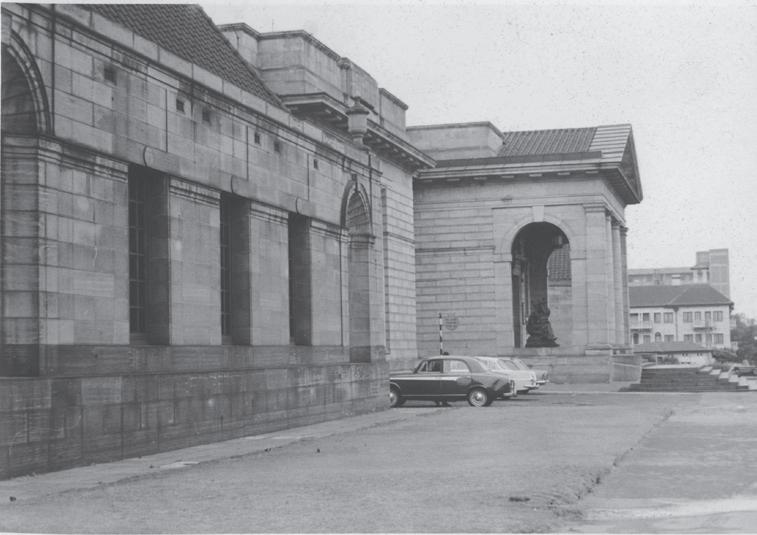

FIG 5 (TOP LEFT): Construction site, 1913. FIG 6 (TOP CENTRE): Completed south façade, 1915. FIG 7 (TOP RIGHT): Drawing by W Brigham of south façade and north extending wings.

©Collection MuseumAfrica, Johannesburg. FIG 8 (BOTTOM LEFT): St Paul’s Church, Covent Garden (1631-8) by Inigo Jones.

©Steve Cadman, Wikimedia Commons. FIG 9 (BOTTOM CENTRE): South façade entrance, 2015. ©David Ceruti. FIG 10 (BOTTOM RIGHT): Portal roof showing parapet termination at left.

arch is a prototype for the later war memorials in New Delhi and northern France (Hopkins & Stamp 2002). And JAG,

apart from being the only museum Lutyens ever built, was intricately bound to Lutyens’ first major institutional project: the British School in Rome. JAG was bracketed between the two stages of the British School development: the temporary British Pavilion for the 1911 International Exhibition in Rome, and the subsequent permanent building on the pavilion site, which was donated by the Syndic of Rome. The person who motivated for the permanent building in April 1911 was the British Ambassador Sir Rennell Rodd, who had persuaded

Lutyens in early November 1910 to go to South Africa (Hopkins 2002:69-70).4 Amongst the preliminary sketches (1910) for the pavilion are smaller-scale drawings, which show remarkable similarities to the JAG design, suggesting a close association in Lutyens’ mind of the two projects. He was convinced that pure classical architecture was essential for a New Country which did not, as yet, have examples to emulate (Hussey 1989:208-209). Linking the JAG project with one based in the heart of ancient Rome would not have been surprising.

Lutyens was apparently instructed by the Board of Trade, which was responsible for organising the temporary British Pavilion at the Rome International Exhibition, to use Christopher Wren’s (1632-1723) St Paul’s Cathedral as the template (which, he told Herbert Baker, he adapted into something more original, without the Board even noticing) (Hussey 1989:208-209). The portico at the British School gives a nod to the upper floor of St Paul’s grand double-floor entrance, in a more simple way. It too has six paired Corinthian columns and a triangular pediment with mutules (small flat blocks) on the underside of the pediment slopes and the cornice, which extends back from the pediment and along the side walls. The pediment at the British school, however, is empty of Wren’s elaborate decorations. JAG’s portal is deeper in proportion to the rest of its façade, much more simple and on a smaller-scale. Like the British School it has an empty pediment and a cornice with mutules, which recedes back to and along the flanking walls, turning the corners for a short space. The mutule cornice is resumed shortly before the north ends of the two 1915 east and west wings, as can be seen in this photograph of excavations for the 1986 extensions. The principle difference between the British School portico and JAG’s is the use at JAG of two columns with simple Ionic capitals and bases, situated between two square corner piers, a type known as distyle in antis. The piers each have large arches on the side. A similar

portico was used by Inigo Jones (1573-1652), England’s first classical architect, at St Paul’s church in Covent Garden, London. (Fig 8) Lutyens knew Jones’ church and it is likely that he references it in JAG’s portico.

JAG’s unusually deep portico dominates the south façade, with a huge projecting rusticated base, elaborate side niches, and architrave lines emanating from the niches, balancing the weight of the portico (Butler 1989:45). (Fig 9) The large flight of stairs adds to the grandeur of the entrance. Two curious triangular abutments appear halfway back on the portico, the termination of the parapet that extends across the façade on either side of the portal. They are not easily visible from ground level, so do not intrude on the classical entrance with its columns and piers. (Figs 7, 10) Butler (1989:45) draws attention to “the perfect taper and the entasis5 given to the two columns and the square corner piers”, giving the rather austere portico a vital look. The treatment of the inside of the portico, however, is far from austere. The curved and coffered (recessed square panels) ceiling may be restrained (Fig 11), but the door and flanking windows have florid Wren-like swags above them, the side windows also having a triangular feature with a cherub’s head as the keystone of each window. (Figs 12, 13) The square openings beneath the windows were not part of the original plan, but were probably made for security reasons, so that people in the interior offices could easily see outside.6 The decorative features, which incorporate proteas, were likely to have been made in the workshop of Anton Van Wouw, who worked closely with Herbert Baker and his colleagues at this time. Van Wouw apparently made the clay models, which were then carved by stonemasons.7 The consoles that support the cornice below the decorative swag were probably a standard part of a stonemasons’ repertoire. (Fig 14)

The elaborate niches on either side of JAG’s portico and on the north ends of the wings are particularly fine adaptations of a more austere classical style. (Figs 9, 15) The jutting cornice with mutules at the bottom of the main portal’s pediment, extends along the flanking walls, with a parapet above. The niches punctuating each side of the portico repeat this feature on a much smaller scale. (see pg i south elevation plan) There are other details in these south niches of great subtlety and beauty, consisting of a series of recessive portal-like structures within an outer rectangular recess. From two large Ionic columns, barely attached to the wall, each is topped by a flat abacus (the small slab between the capital of the column and the architrave) to two square pilasters with an architrave and pediment above, to an empty niche with subtly recessed sides, and a rounded top with a radiating stonework feature. Subtle masonry lines connect some features across the entire façade. (see pg i south elevation plan and Fig 6) These elaborate recessive niches and the interplay of dark

and light shadows make them strong, impactful features, which balance the dominance of the portico.

The adaptations on the north ends of the wings are less elaborate and more highly set on the façade, integrated with the cornice and mutules above. (Figs 16, 17) A large plain arch surrounds the inner pedimented feature. Its keystone connects with the thin base under the cornice and mutules, centred between two of them, with angular radiating stonework linking the hemispherical top of the arch with the horizontal cornice and stonework courses below. As with the south façade, a distinct narrow projection extends from the abacus beneath the architrave and pediment along the adjacent walls. But unlike the south feature, the pediment rests on fully rounded Ionic columns (and not square pilasters) with a suggestion of square pilasters behind them. The columns rest on a stepped base that echoes that of the south façade, with the vent replaced by a square indentation. These northern ends of the wings can be viewed today

FIG 14 (TOP LEFT): Console, central door. FIG 15 (CENTRE): Niche to east side of the portal. FIG 16 (BOTTOM): Niche at north end of east wing, view from Meyer Pienaar extensions.

FIG 16 (BOTTOM): Niche at north end of west wing, view from Meyer Pienaar extensions. All images by ©David Ceruti.

from below through large glass bay windows in the Meyer Pienaar and Partners 1986 extensions, an inspired link between the old and the new.

From the exterior we now move to the interior. The main door under the portico leads into a small lobby with offices on either side. The scrolls on the flanking doors in the lobby and its curved coffered ceiling suggest the grandeur of the great gallery into which it leads, known since 1986 as the Phillips Gallery. (Fig 18) Along the south wall of the entrance into the Gallery are two recesses flanking the door (probably meant for display cabinets), all three with superimposed arches, facing three large windows on the north wall, the equivalent in height of the opposite arched door and recesses.8 (Figs 19, 20) The delicately decorated barrelvaulted ceiling interacts with the three features on either side. (Figs 21, 22) A circle at the middle intersects a curving recessed panel, which springs from the tops of the window and door-arch on opposite sides. Two elongated panels between the door and the two recesses curve across the ceiling to the spaces between the central and outer windows, terminating with a recessed circle and a floral swag that includes proteas. (Figs 23) Both ends of the long barrel vault ceiling terminate with two recessed panels springing from a recess-arch and a window-arch. The east and west ends of the grand gallery’s ceiling are terminated with a flat arch. All the doors, both here and in the other galleries, feature consoles (more simple than those at the portico) supporting cornices, which form a continuous band around each room. (Fig 24) The four elaborate swags in the Phillips Gallery, and the consoles throughout, would have been cast in plaster from a model, a technique described in detail by Jack Rich (1947).9 Another feature throughout JAG is that all the woodwork is teak.

A small sculpture lobby, or apse, leads out from both ends of the Phillips Gallery. (Figs 25, 26) A curved wall with

delicate receding cornices faces an opposite door, which leads into what is now the central courtyard. A patterned skylight corresponds to a charming hexagonal glass structure on the roof, like a small summer-house. (Fig 27) The next room is the first of the top-lit picture galleries, a square shape with the two south corners truncated (Fig 28), echoing the curve of the apse, while directing the visitor to the opposite entrance into a long picture gallery with top lighting. (Fig 29) At the end of this gallery is another squareshaped room with top-lighting. A side door opened from this room into the gallery gardens and the park, visible on the far right of the Meyer Pienaar excavation site. (Fig 30) The raised glass structures on the roof correspond in square and rectangular shapes to the rooms below. (Fig 31) Like the hexagonal structure, they are hidden from view by the south façade’s parapet, although they could be seen from the park side until the Meyer Pienaar extensions concealed this view.

This flat u-shape of rooms is what constituted the Gallery until the south pavilions to the east and west were constructed (1938-1940) .

After the unfinished building opened, JAG was generally neglected by the council until about 1930. John Maud, who was commissioned by the council in 1935 to write a history of the local government of Johannesburg, comments on the lack of interest shown to JAG and the meagre municipal revenue allocation.10 But things started looking up when council voted £200 pounds for Lutyens to do preliminary sketches showing proposed extensions to JAG, with particular reference to the method of lighting (meeting of 25 February 1930). The cost of extensions was agreed at a meeting of 3 April 1936, Lutyens and Howden were appointed at a meeting of 23 June 1936, and the plan for the extensions was approved at a meeting of 23 February 1937. It was reported on 27 July 1937 that working drawings (Fig 32)

and specifications had now been received from Sir Edwin Lutyens, and tenders were called for. Although the costs exceeded the estimates – the revised new pavilions, for example, were 25% larger than those in the original plan – a loan was sanctioned and work began in 1938. The building was overseen by the first professional director of JAG, Anton Hendricks (later Hendriks), whose appointment was recommended on 27 April 1937 by the Art Gallery Committee.

In the meantime, the Art Gallery Committee’s request to turn the basement into an exhibition space had been granted (26 March 1935) and part of the Howard Pim 1934 bequest of over 500 original prints was exhibited here in late 1936. About 40 years later, a similar basement space was excavated and enlarged to display contemporary South African art.

The two new pavilions, after delays during 1940 due to wet weather and a change from Elands River Stone to Flatpan, amongst other reasons, appear to have opened without ceremony in mid-1941. (A Lutyens déjà vu.) Council reported on 27 May 1941 that the architects’ final statement showed a saving on the contract, and proposed to use this for alterations in the basement, the south wall of the east pavilion, show cases, benches and seats etc, and sundries. This was one of the few times when JAG was flush with money.

The four pavilions in the original 1911 plan appear almost homely (see pg i south elevation plan), each with a chimney and rooms for different purposes: administration, a library, a re-creation of a Cape Dutch home, and a temporary exhibitions space (McTeague 1984:146). The two new pavilions present something more simple and modern, with two top-lit long galleries. (Figs 10, 33) They are described and illustrated in detail by Butler (1989:45-46, plates XC-XCII, Figs 219-228), who evidently worked closely with the development of Lutyens’ plans. For example, he

FIG 28 (TOP LEFT): Square gallery with truncated corners.

FIG 29 (TOP RIGHT): Long picture gallery with top lighting.

FIG 30 (CENTRE LEFT): Side door from north square gallery, visible to right of construction site. FIG 31 (ABOVE LEFT):

Rectangular skylight structure on the roof. FIG 32 (ABOVE RIGHT): Lutyens’ proposal for the art gallery extensions, 1937.

FIG 33 (BOTTOM LEFT): East and west pavilions built 1937-1941.

states that Lutyens’ original intention for the south walls of the pavilions was to have them quite plain between the two niches, which are far simpler than the complex niches flanking the portico. The walls were not meant to have windows, but these were required, as the rooms were to be used for administrative purposes. The loggias at each end are also new compared to the earlier plan, their inclusion perhaps being a small compensation for the many loggias in both the old and new plans, which never materialised.

A more likely reason, however, is that they extend the length of each pavilion and offer accommodation for the outer arched niche beyond the fenestrated gallery which, logically, one would think should be behind it. The inner niche, similarly, has no connection to the gallery behind it. (see plan, Fig 32) In fact it backs onto a staff toilet, a detail which Lutyens could well have done intentionally, displaying his almost playful subterfuges of placing features in areas unrelated to what one would expect from the outside. In creating a longer façade to the south east and south west galleries, Lutyens had more space to punctuate the walls with deceptively simple oblong windows, and to create an intricate, almost humorous, interplay of classical elements. He deeply recesses the windows, so the effect is of a façade with four squared piers on a linked base, each with an identical abacus. The windows each have a subtle disc above, and the air vents further above are idiosyncratically arranged. The niches with their shell-like concave tops seem to close the ends of each pavilion with a flourish, accentuated by the decorative jars atop the corners.

The pavilions are connected to the central building by a curved wall, which joins at the level of the continuous thin architrave that runs across the central façade. (Fig 34) They are at a lower level than the main building, and their curved connecting wall projects them dramatically forward, balancing the projecting central portico. Within the main building, the central access runs through the Phillips Gallery

and the galleries on either side of it, then down through the north room (Fig 35) of the pavilions, presenting dramatic perspectives. (Figs 36, 37) The sky-lighting for the two pavilion exhibition areas is completely hidden from view, except in aerial photographs, such as that of the combined Lutyens and Meyer Pienaar building, where an oblong indentation is visible in the centre of each pavilion roof. (Fig 38) Butler (1989:Fig 224) illustrates this extraordinary feature: a central space with perpendicular windows that filter light into the galleries on either side. Access to this roof feature is via a narrow corridor that separates the two galleries. This is not the only intriguing feature of these new extensions.

There is an extraordinary series of interlinked spaces which, for me, epitomise the genius and humour of Lutyens. I shall explore the feature in the east wing. This begins with a stone lobby leading off the south east square gallery with truncated corners. (Fig 39) (The two areas are on the same level: the view given in this reproduction is taken from above.)

The exquisitely crafted teak door, surmounted by a pediment, leads to a mundane toilet, which in turn looks out onto a hidden clear space open to the elements, and a wall on the outside of which is one of the pavilion niches. One then descends the adjacent stairs into the pavilion exhibition galleries, the steps starting with a slight curve and ending with a straight step at the bottom. (Fig 40) Just before entering the pavilion galleries, one notices a teak door to the right, which is usually closed to the public. Hidden behind this is a small circular vestibule with finely crafted features, one of the most beautiful rooms in the Gallery. It leads down to the metal-rung access to the roof. The first steps are bordered by a block with chamfered corners. (Fig 41) The stairs then turn right, beginning with a straight step and angling as the wall turns until one reaches another teak door. (Fig 42) Around the wall are architectural features which serve no purpose other than being

FIG 41 (TOP): Block with chamfered corners in vestibule. FIG 42 (CENTRE): Steps in vestibule. FIG 43 (BOTTOM): Architectural feature in vestibule. All images by ©David Ceruti.

FIG 44 (TOP LEFT): Hexagonal skylight in vestibule. ©David Ceruti. FIG 45 (TOP CENTRE): Spiral staircase to the roof.

©David Ceruti. FIG 46 (TOP RIGHT): Early view of JAG from Joubert Park. FIG 47 (ABOVE): Early view of Joubert Park from JAG. FIG 48 (BOTTOM LEFT): Early view of Joubert Park from JAG. FIG 49 (CENTRE): Establishing the sculpture garden. FIG 50 (BOTTOM CENTRE): Opening of the sculpture garden, 26 May 1971.

beautifully decorative. (Fig 43) And above is a perfect dome with a hexagonal skylight (Fig 44), exactly like the small hexagonal glass house on the roof above (Fig 27), which one can reach via the spiral metal staircase on the other side of the teak door. (Fig 45) I confess to being completely puzzled trying to match the two skylights, then realised I was experiencing one of Lutyens’ architectural conceits. This little room is meant to puzzle and please, occupying a ‘left-over’ space, which is irrelevant to the edifice or rooms outside.

The Lutyens building remained incomplete for the next 45 years. It had a period of prosperity under Anton Hendriks in the 1950s, but became increasingly inadequate space-wise and increasingly ignored as a national asset. In the 1960s there were plans to move the collection to new and larger premises in Parktown,11 and the Lutyens building was put up for sale in late 1960. Various proposals for the re-use of the building were discussed in the press of the time: a railway museum, a bus terminus, a crèche, a music school and an eye research institute. “The Johannesburg Art Gallery is static, it lacks vitality, it is nothing but a richly embellished mausoleum” announced TheStar, 30 April 1965, saying that its press files were full of criticisms of the art gallery.12 The Gallery had completely inadequate space to fulfil the role it should have been able to play.

JAG continued to struggle and increasingly became cut off from Joubert Park, with which it had been closely connected (Figs 46-48), and a security fence was required to protect the open north side. In 1971 this area was turned into a sculpture garden, an appropriate setting for items that were difficult to display within the premises. (Figs 49-51) In the early 1970s a basement area was excavated to create a space dedicated to contemporary South African art. To enlarge the available space, the city council constructed a library and storeroom attached to the Gallery in 1974, “an

odious brick extension, totally in conflict with Lutyens’ design and in fact disfiguring it.”13 The battle for extensions continued until finally the city council provided a budget in the 1984/85 financial estimates, and building operations began in October 1983. The extensions opened in October 1986, to coincide with the centenary of Johannesburg.

The architects appointed for the project were Meyer Pienaar and Partners Inc, who said from the outset that they wished to honour the Lutyens building by creating something in the footsteps of Lutyens, a completion in a modern idiom of his original plan.14 A granite plaque at the new north entrance of JAG proclaims the intertwining of the parts of the building. (Fig 52) In all the building works, the integrity of the original Lutyens building was respected, with later alien accretions, like the outside library and storeroom, being demolished. The central courtyard is perhaps the most beautiful of this meeting between the old and the new, with the large windows in the Meyer Pienaar extension reflecting the Lutyens windows opposite, and the doors leading into the courtyard on either side of the two walkways complementing each other. (Figs 53-55) The rough brick walls on parts of the original 1915 wings in the courtyard are now clad in stone, slightly distinct from the original Lutyens stonework in a step design. (Fig 56) There are also smaller details which emulate Lutyens in a modern idiom, such as the tall wooden doors leading out of the north-east and north-west exhibition areas to the education and conservation quarters on one side, and the administrative and library quarters on the other. The circular lobby outside the staff quarters is a particularly Lutyens-like gem with a window in the apex of the dome. The wing that closes the courtyard at the north is largely glazed on the south side, providing a sense of space and light. (Fig 57) There has already been mention of the successful way in which the visitor can see the ends of the two Lutyens wings through large curved glass windows.

The main entrance to JAG was turned around in the Meyer Pienaar design so that it faced out towards the park, a conscious decision to engage neighbouring communities. (Figs 58-60) The new entrance façade emulates the three large Lutyens windows and looks out over the copper barrel vaults that reflect light into the vast new exhibition spaces underground, accessed via steps and ramps from the main hall. (Figs 61-63) An attractive feature downstairs is the amphitheatre facing through glass doors onto a semi-circular water feature. (Fig 64) A corresponding lecture theatre was created in the basement under the Lutyens building that used to house the contemporary South African collection.

The Meyer Pienaar extensions have unfortunately suffered from structural defects since it opened. This, and the changing nature of Joubert Park, which has been fenced off from

FIG 53 (TOP): Central courtyard, Lutyens façade to the left, Meyer Pienaar façade to the right. FIG 54 (BOTTOM LEFT): Entrance to Lutyens building from courtyard. FIG 55 (BOTTOM CENTRE): Entrance to Meyer Pienaar building from courtyard. FIG 56 (BOTTOM RIGHT): East wall of courtyard with stepped stonework. All images by ©David Ceruti.

JAG for some time, have unfortunately impacted on the new extensions. But despite the grave conservation state of the Meyer Pienaar extensions, the shifting nature of the structure has led to exciting interventions from contemporary artists and new opportunities.

It is ironic that the building that turns 100 this year is in better shape than the newer one attached to it. But it has taken a long time for the full worth of Lutyens’ contribution to local and international architecture to be appreciated. It was declared a national monument in January 1993, a badge of honour that ensures its place in the future of this city and country.

1 For the sake of clarity, Florence Phillips and Lionel Phillips are referred to as Florence and Lionel in subsequent mentions. Also, honorifics are not used, as knighthoods for most of the main characters had not yet been bestowed when the Gallery project started.

2 The members of the board are listed in a letter from Engelenburg to Middelberg, 25 July 1910, JAG archives.

3 Personal communication. Hussey, for example, discussed these sketches “without realizing their full significance” (Miller 2002:226 note 21).

4 International trade exhibitions were a frequent occurrence in Europe and North America at this time. Magnificent pavilions, representing different countries, were constructed from temporary material designed to be dismantled at the close of the exhibition. Sketches for the pavilion and subsequent British School feature in various chapters in Hopkins & Stamp (2002).

5 The entasis is a slight swelling along the outline of a column designed to counteract the optical illusion of curving inwards.

6 McTeague (1984) draws attention to this feature.

7 I am grateful to Jonathan Stone and Alexander Duffey for their insights on these details.

8 The north wall with three large windows is reminiscent of Lutyens’ orangerie at Hestercombe, Somerset, 1904 (Miller 2002:162).

9 I am grateful to Jonathan Stone for drawing my attention to this book and the techniques of plaster casting.

10 Maud (1938:147, Appendix I). Maud was appointed to write the book at a council meeting of 26 March 1935.

11 A site in the Pieter Roos Park, Parktown, was designated, although sites near the War Museum in Saxonwold and the proposed civic centre in Braamfontein were also considered. Rand Daily Mail, 28, 29 November, 1, 2, 7, 8, 12, 22, 24 December, 1960; The Star, 27 January 1962.

12 For this background see Carman (2003).

13 Thelma Gutsche, letter to The Star, 11 July 1974.

14 Information on the Meyer Pienaar Inc extensions comes from material in the JAG archive such as press releases, media packs, annual reports, news cuttings, articles, pamphlets.

Archives

Council meetings: minutes books, Local Government Library, Johannesburg.

JAG: archives of the Johannesburg Art Gallery.

JAG Hunt Collection: photocopies at JAG of a private collection in the UK.

NL: Manuscripts Department, National Library of Ireland, Dublin.

RIBA, Lutyens letters: British Architectural Library, Royal Institute of British Architects, London. Lutyens family papers, Edwin Lutyens and Herbert Baker correspondence.

Publications

Butler, ASG. 1989. The Lutyens Memorial.The Architecture of Sir Edwin Lutyens. Volume 2. With the collaboration of George Stewart & Christopher Hussey. Reprint of 1950 Country Life Edition. Woodbridge: Antique Collectors’ Club.

Carman, J. 2003. Johannesburg Art Gallery and the Urban Future, in Tomlinson, R, Beauregard, R, Bremner, L and Mangcu, X (eds). Emerging Johannesburg. Perspectives on the Postapartheid City. New York: Routledge.

Carman, J. 2006. Uplifting the Colonial Philistine: Florence Phillips and the MakingoftheJohannesburgArtGallery. Johannesburg: Wits University Press.

Carman, J (ed). 2010. OneHundredYearsofCollecting:TheJohannesburg Art Gallery. Johannesburg: Johannesburg Art Gallery.

Dawson, B. 1993. Hugh Lane and the Origins of the Collection, in Images and Insights. Dublin: Hugh Lane Municipal Gallery of Modern Art.

Gutsche, T. 1966. NoOrdinaryWoman.TheLifeandTimesofFlorencePhillips Cape Town: Howard Timmins.

Hopkins, A. 2002. Lutyens’s Plans for the British School at Rome, in Hopkins & Stamp 2002.

Hopkins, A & Stamp, G. (eds). 2002. LutyensAbroad:TheWork of Sir Edwin Lutyens Outside the British Isles. London: The British School at Rome.

Hussey, C. 1989. The Life of Sir Edwin Lutyens. Reprint of 1950 Country Life Edition. Woodbridge: Antique Collectors’ Club.

Keene, JL. 1986. The Rand Regiments Memorial. Museum Review, 1 (3): 78-89.

Maud, JPR. 1938. City Government:The Johannesburg Experiment. Oxford at the Clarendon Press.

McTeague, M. 1984. The Johannesburg Art Gallery: Lutyens, Lane and Lady Phillips. The International Journal of Museum Management and Curatorship, 3 (2): 139-152.

Miller, M. 2002. City Beautiful on the Rand: Lutyens and the Planning of Johannesburg, in Hopkins & Stamp 2002.

Miller, M. 2006. Hampstead Garden Suburb: Arts and Crafts Utopia? Chichester: Phillimore.

Rich, JC. 1947. The Materials and Methods of Sculpture. New York: Oxford University Press.

Ridley, J. 2003. Edwin Lutyens:His Life,HisWife,HisWork. London: Pimlico.

Dr Jillian Carman is a Visiting Research Associate in the Wits School of Arts, University of the Witwatersrand and was a curator at the Johannesburg Art Gallery for a number of years. She is the author of Uplifting the Colonial Philistine: FlorencePhillipsandtheMakingoftheJohannesburgArt Gallery(2006), and editor of OneHundredYearsofCollecting: the Johannesburg Art Gallery (2010). She serves on the Johannesburg Art Gallery Committee and the Wits Art Museum Board, and is a trustee of the Rand Regiments Memorial and honorary patron of the Michaelis Collection, Cape Town.

FIG 61 (FAR LEFT): Entrance to downstairs exhibition space. FIG 62 (SECOND LEFT): Exhibition space, late 1980s. FIG 63 (ABOVE LEFT): Exhibition space, 2015. ©David Ceruti. FIG 64 (ABOVE RIGHT): The amphitheatre looking towards the water feature, 2015. ©David Ceruti.

Louis Grundlingh

The early growth of Johannesburg presents the context and the opportunity to explore the nature, purpose, function, characteristics, meaning and design of Johannesburg’s erstwhile premier municipal public park, Joubert Park, and its adjoining structures, including the Johannesburg Art Gallery.

Joubert Park became an important leisure site for the citizens of Johannesburg since its founding in 1892 and turned out to be a significant spatial marker of crucial changes occurring in a fast-growing Johannesburg. Perhaps the most important of these transitions was from Johannesburg being under the governance of the Zuid-Afrikaanse Republic (ZAR) (1886-1902) to a British governmental system after the South African War. The latter significantly influenced its layout, design and features. Areas for promenading, a bandstand, conservatory and art gallery combined to create and give material form to Victorian and Edwardian concepts of identity, class and ‘respectability’ as interpreted and reflected by Johannesburg’s town fathers. By the 1900s the Park was an integral part of the civic and cultural life of a class- and racially divided city, in many ways an exemplar of a British park.

The Transvaal Government, overseeing the spatial development of Johannesburg, was determined that the grid-line plan should be implemented in the layout of the town. Thus the vision of Johannesburg’s first land surveyor, Josias E de Villiers, to plan large property blocks and generous open spaces, was foiled. In terms of open spaces, the result was that Johannesburg was left with only a large market square (Neame undated:102), two more squares and a cemetery (Shorten 1970:645-46). So by May 1887 there were only a modest number of public spaces scattered throughout the town.1

However, when the rest of the farm Randjieslaagte was surveyed, an open area remained – far from the centre of the town. In 1888, the Diggers’ Committee was successful in persuading the ZAR government to set aside two portions of this land to be developed as parks – Kruger Park2 and Joubert Park. Prior to the development of Joubert Park, the site was well frequented for picnics along the spruit, which bisected the park.

By the second half of the nineteenth century, civic leadership and park promoters in Britain regarded parks as something essential for the wellbeing of an urban community.

They could become places of betterment for the ‘lower levels’ of society and symbols of civic pride, providing open spaces to enjoy their leisure time.

Whilst these functions were supported, to establish a park needed the financial backing from civil society. Fortunately the height of the parks movement in Britain coincided with a fashion for generous philanthropic gestures. The gift of a park from a wealthy citizen became common. The enthusiastic Mining Commissioner, Jan Eloff, was a fine example of where the gift of philanthropic entrepreneurs blended with an eye for profits from rising land values.

Shortly after the proclamation of the diggings, he almost immediately decided that the inhabitants of the fast growing mine camp should enjoy a “public park or garden to be planted with trees” (Bruwer 2006:102). For this purpose, and while frankly admitting ulterior motives, namely that he intended to build his house on adjoining ground, he recommended to the ZAR government a site for a park to the north of the present railway lines. Joubert Park was thus laid out as an upmarket recreation area.3 The Minister of Mines, CJ Joubert, supported the proposal. On 15 November 1887, the ZAR government granted Johannesburg

sixteen acres (6,5 hectares) of marshy ground (Shorten 1970:647 and Van Rensburg c1987:177).4 However, not much happened with the grounds for the next four years.