PRIVA[SEE]N: URBANIZING THE DIGITAL GAZE

ABSTRACT 01 PRIVA[SEE]N

ABSTRACT

The city is a place of infinite encounters; infinite windows, passages, strangers, eyes, and gazes. We are caught up in a system of gazing while being gazed upon, an endless series of interactions where power and anxiety are in constant flux. Estrangement, alienation, and anxiety have long been linked to the aesthetics of space throughout the modern period, where there is no greater an unease-inducing setting than our densifying urban cores. Narrow streets, collections of repetitive openings, and the condition of being viewed from all angles; the city is an inescapable stage.

The position taken is that this universal anxiety is a result of the urban gaze itself, and the architectural frames we view and are viewed through. If this anxiety is brought on by the act of gazing and being gazed upon, then it can be inferred that this unease is in relation to our boundaries of privacy over one’s body. The work aims to uncover how bodies are currently viewed through architectural apertures, and to study our limits of privacy within the city.

In an era of unlimited digital access, we exist within a condition of social surveillance where lines of privacy have been negotiated further than the expectations for our physical environment. The project accepts this culture of shameless viewing, and

applies the notion of framing, editing, and curating the self-image to the built environment, amplifying our collective viewing pleasures.

What if the urban street façade was a staging of bodies in space, where apertures respond to the life beyond them, and our perceptions of privacy are questioned to create a display of activity. Can the phenomena of the anxious modern subject caught in the urban spatial system of a gaze beyond their control, be shifted to produce a streetscape of performance focused on the viewing of the body through architectural frames?

This collection of studies work to understand how apertures affect our sense of privacy, as well as to propose an objectification of the image of body as a response to urban anxiety. The gaze is used as a tool of analysis to study physical vantage points and understand the psychological framework of the human condition within the city.

The resulting design proposal will become a study of apertures and building skins, designed in response to the scale, movement, and relationship of bodies, where our limits of privacy are negotiated, and the purpose of urban apertures are questioned.

SETTING THE STAGE 02 B. BAYDOCK

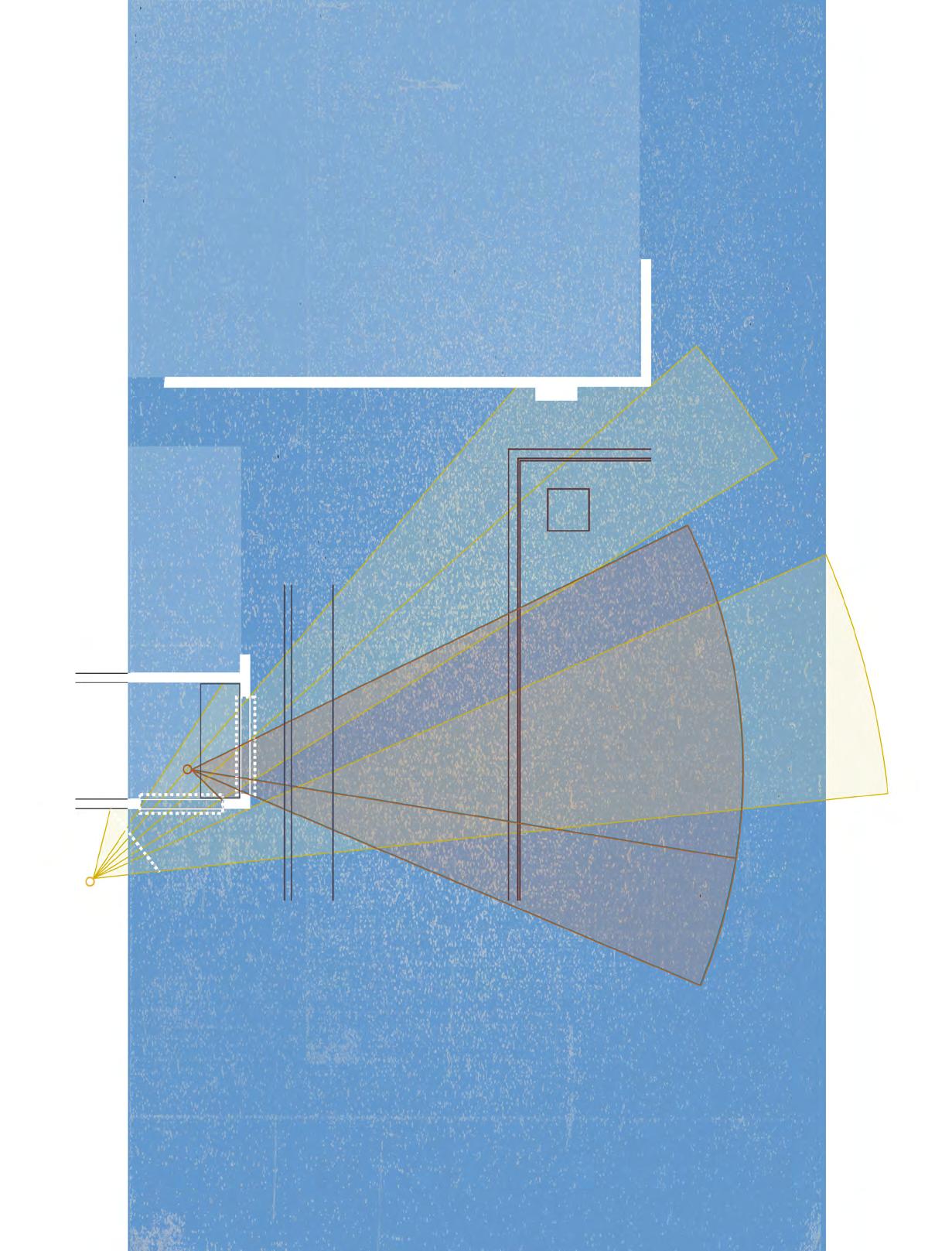

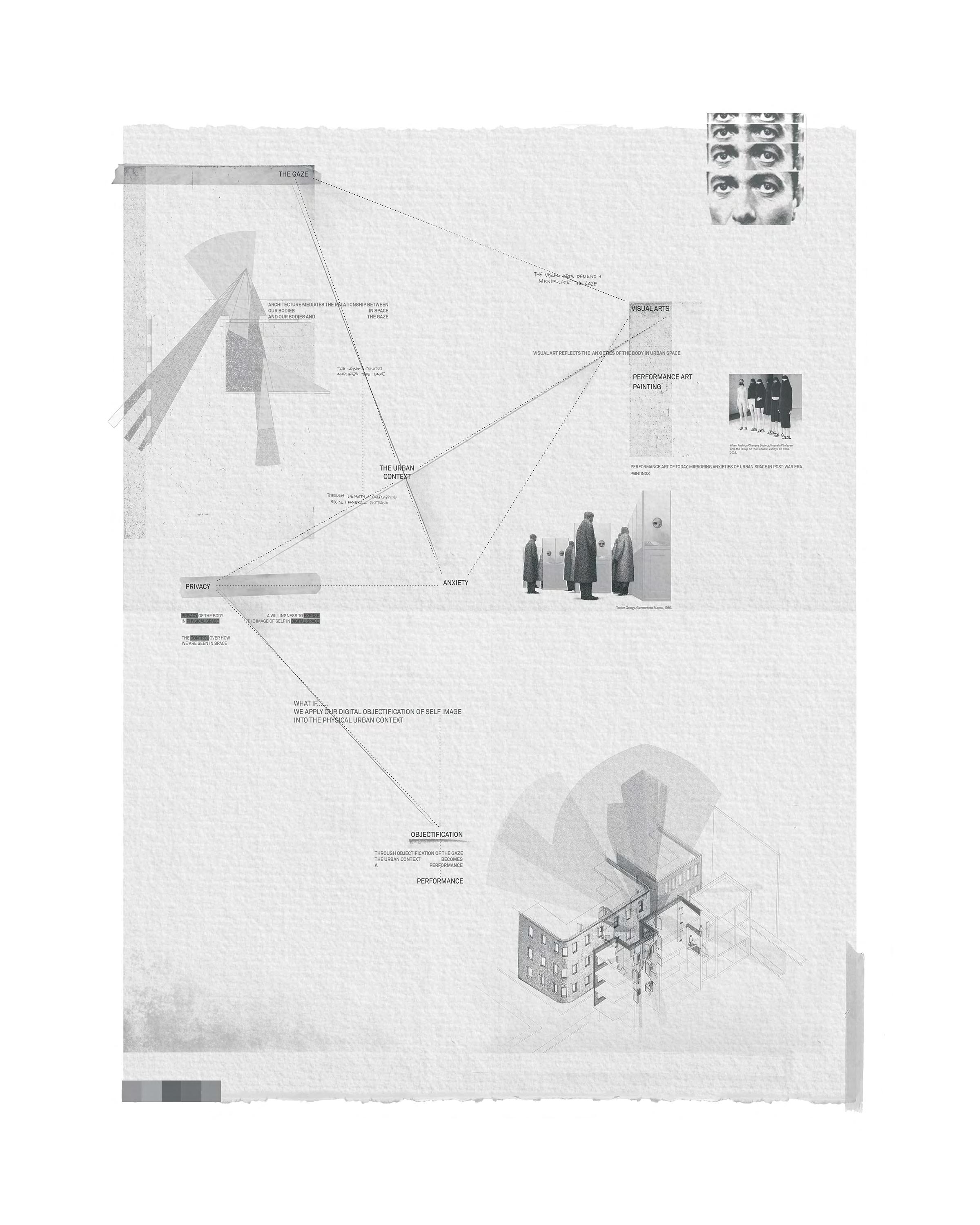

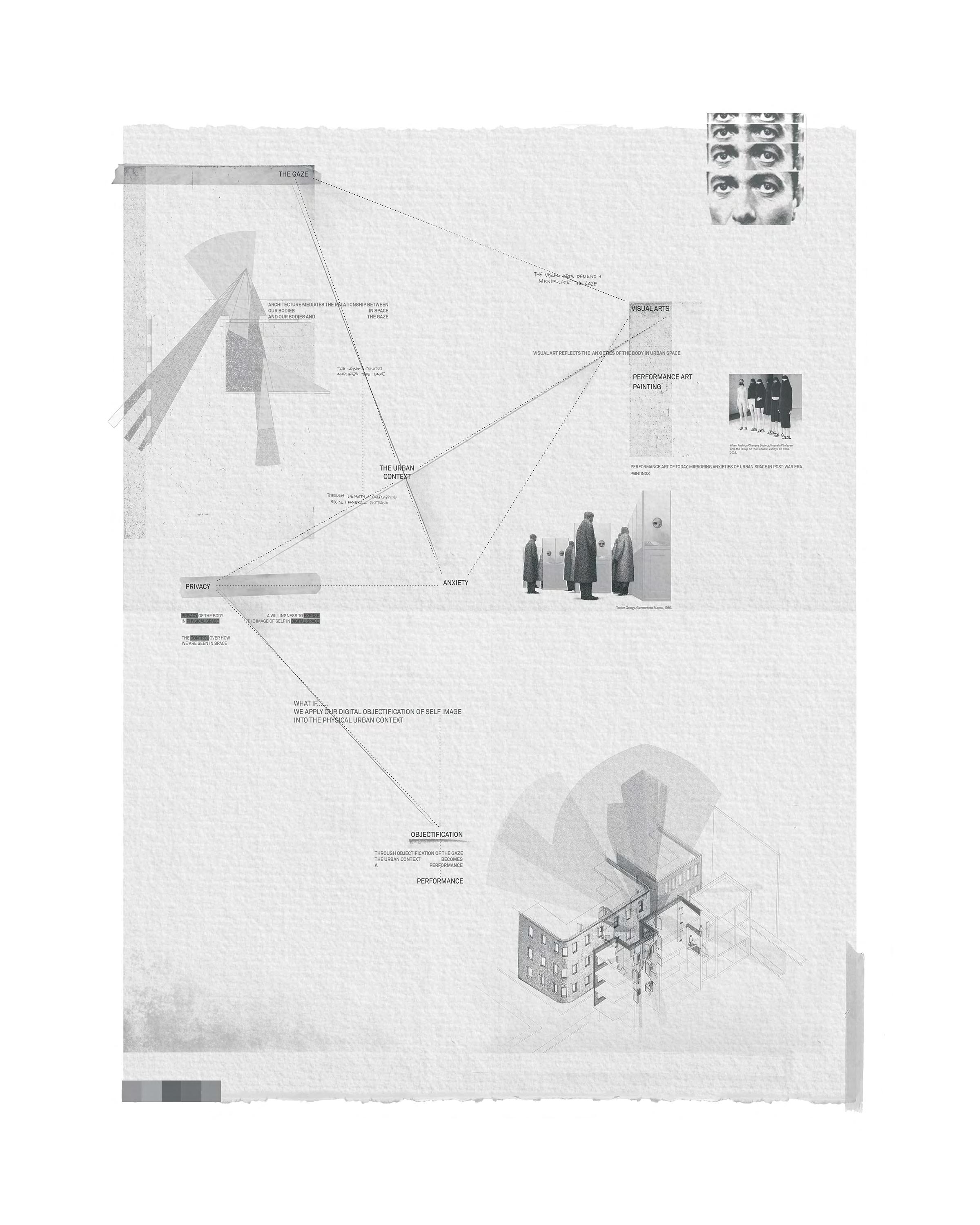

TheoryMap,Digital/Hand Drawing, 01/10

FRAMEWORK 03 PRIVA[SEE]N

FRAMEWORK

Keywords:

The Gaze, Privacy, Apertures, Urban Anxiety, Mediation, Image, Lens, Building Skin, Performance, Viewing Pleasure

As the initial trajectory of interest, the gaze acts as the grounding theme for the studies of investigation. While it began as the sole theoretical framework however, it has now transitioned into a vehicle of analysis to discuss the concepts of anxiety and thus privacy in the urban context. To further understand these concepts, visual, and performance art from the postwar era to the contemporary period, are used as precedent to unpack collective understandings on the act of viewing, as well as shared emotions such as alienation, isolation, and vulnerability, that are engrained in the western narrative of the individual.

The aperture, in its own right, is a messenger of substance, and in relation to the work, the physical embodiment and vessel by which the notions of viewing pleasure, boundaries of the body, and performance are materialized. Can apertures negotiate with our shared privacy boundaries to contribute to the collective performance of the city?

The term ‘city’ is used to encompass a larger understanding of a system of general urban conditions that exist within multiple locations. Though the project is site-less, it can be assumed that when discussing ‘our’ collective perceptions of physical privacy, the context in question is that of Western and North American social constructs. When referencing social viewing pleasure in relation to the digital gaze, however, this condition applies to the wider global environment, addressing a generational culture shift towards objectification of imagery.

The main themes of privacy and anxiety exist within a system governed by the gaze, which can then be viewed through the lens of a culture of objectified viewing, that is materialized through the design of architectural apertures.

The attitude towards bodies in urban space as well as our social relations as represented through the design proposals are intended to be viewed with a slight sense of dystopianism, while remaining idealistically enthusiastic towards cities of performance. Can our manipulation of the gaze contribute to a physical environment designed to accentuate the viewing pleasure of one another?

SETTING THE STAGE 04 B. BAYDOCK

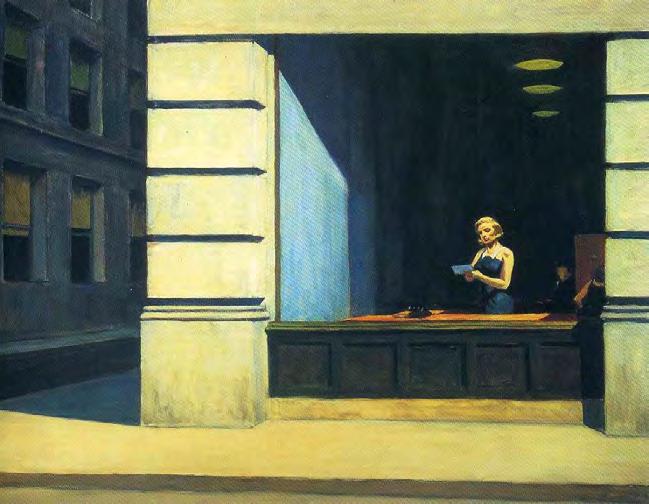

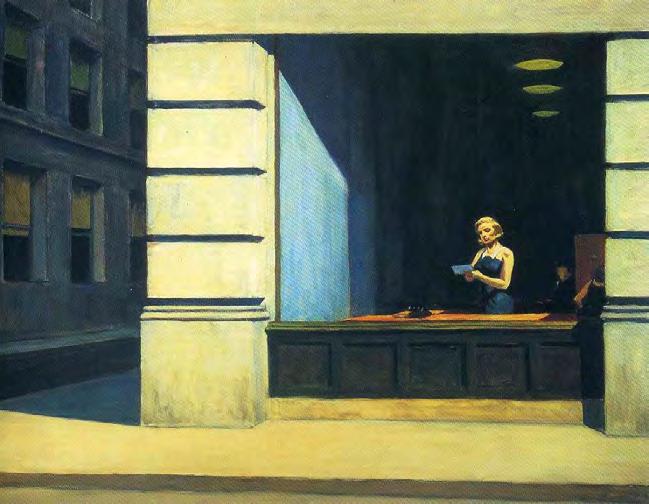

Hopper, Edward, NewYork Office, 1962.

Hopper, Edward, NewYork Office, 1962.

01 THE GAZE 05 PRIVA[SEE]N

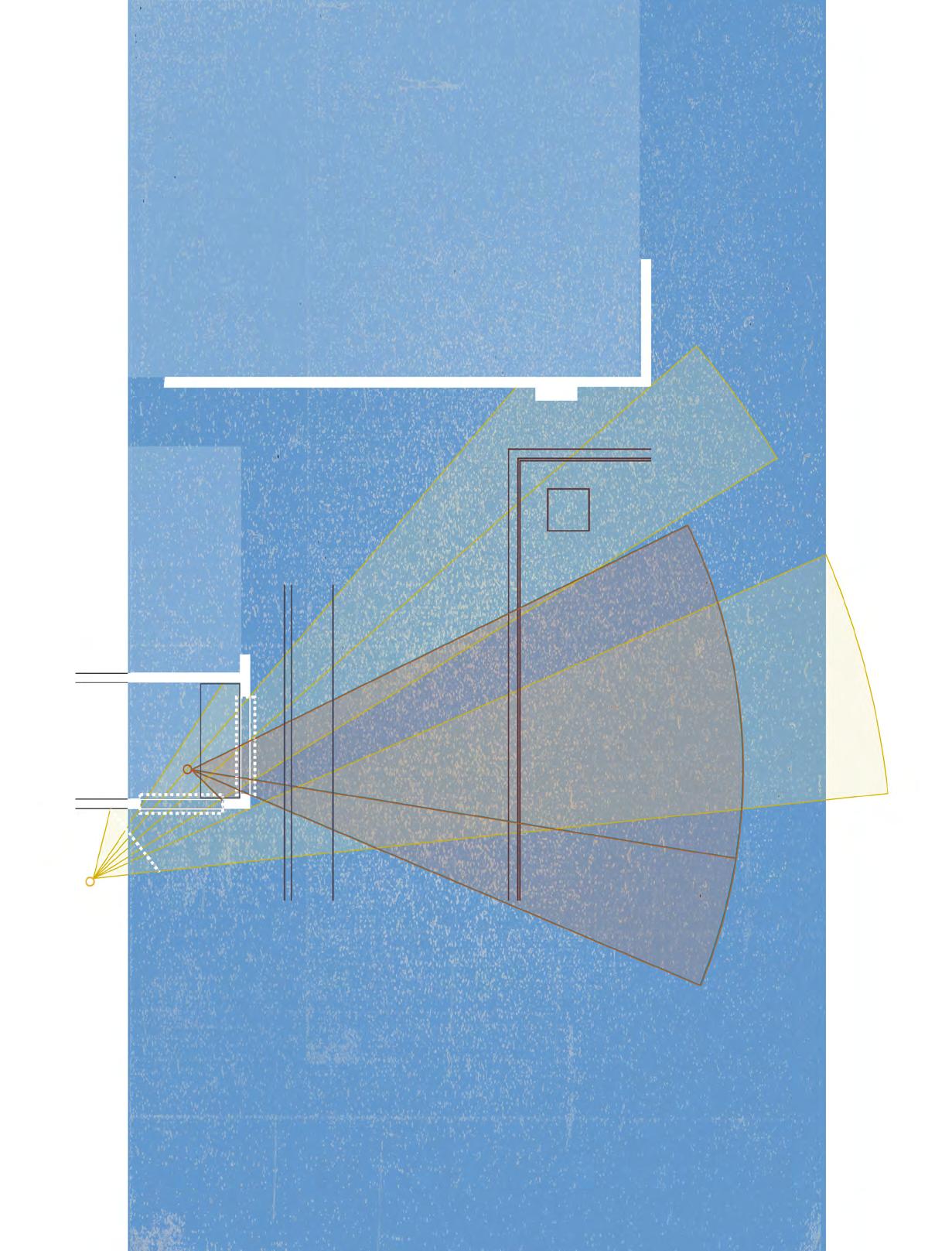

Decon/Reconstructing the Gazes of NewYork Office

THE GAZE

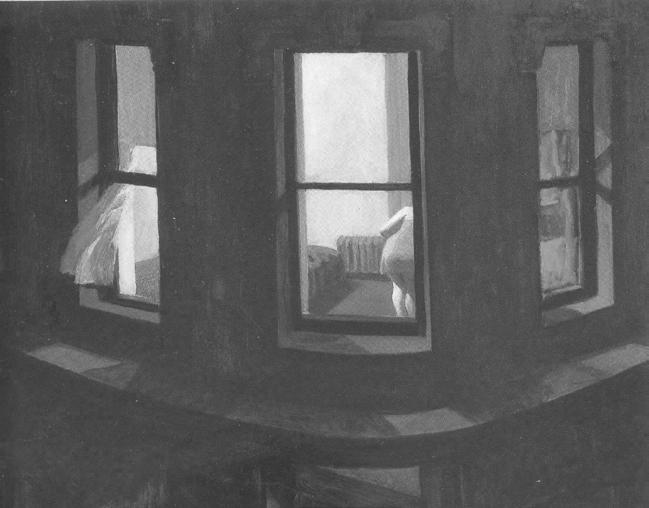

A woman stands slightly off-centre behind the window of her New York office. Her desk appears to protrude past the defined aperture of the building, blurring the division between interior and exterior. The towering frame of the opening and the weight of the stone façade seem to frame her delicate body as the sun caresses her skin. You realize you’re staring. Or are you gazing? Is she gazing back?

Edward Hopper’s, New York Office, illustrates the act of a prolonged urban gaze, captured in time. Perhaps the work even expresses a series of gazes within and beyond the defined frame. What differentiates the gaze however, from a look, view, or stare?

The gaze, as defined in sociology and psychoanalysis, is a bilateral term that emphasizes both the person gazing and the person being gazed upon. At its essence, it is a dynamic relationship that requires two persons, whether they are willingly engaged or not, thus creating an often-imbalanced power dynamic.

The term gaze was introduced into contemporary discourse via painting

theory and feminist film theory during the mid-20th century. Art theory was concerned with the viewer’s encounter and exchange with a painting, while film theory used the term to understand the woman as an object for viewing pleasure. Both theories allude to the objectification of the person on the receiving end of the gaze. Though objectified, both individuals maintain autonomy, as the term gaze as opposed to view or watch, identifies the ability of the object to gaze back. This exchange reveals the gaze as a messenger of power, manipulation, and desire.

Desire refers to the voyeuristic quality of the gaze, where we are drawn to others as a means of spectacle. As social creatures we are drawn to a display of other bodies in our surroundings, viewing them as an act of engagement as well as for pleasure.

Fundamentally, the gaze embodies our perception and awareness of others, notifying us of our own existence within space. Defined as a relationship,however, brings into question the feelings of both parties involved, specifically, how does it feel to be the object of the gaze?

THE GAZE 06 B. BAYDOCK

02

Hopper, Edward, OfficeinaSmallCity, 1953.

HOPPER DECONSTRUCTED 07 PRIVA[SEE]N

Decon/Reconstructing the Gazes of OfficeinaSmallCity

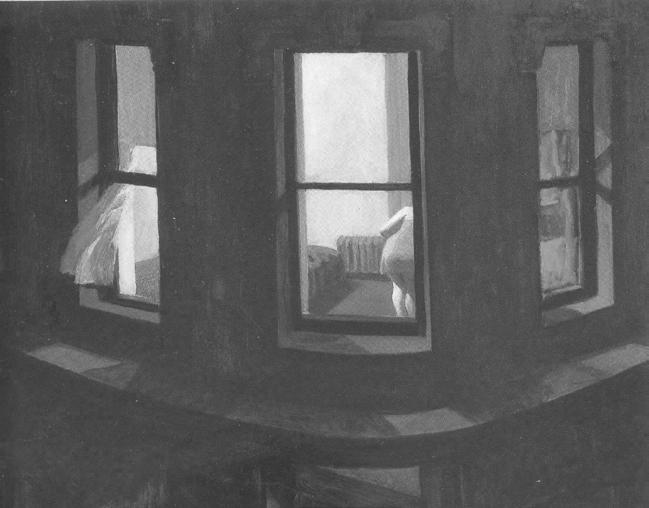

Decon/Reconstructing the Gazes of NightWindows

03

Hopper, Edward, NightWindows, 1928.

THE GAZE 08 B. BAYDOCK

05 06 04 ANXIETY 09 PRIVA[SEE]N

ANXIETY

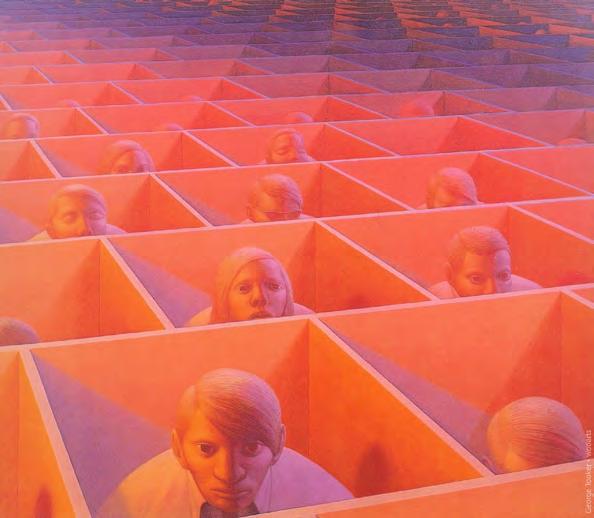

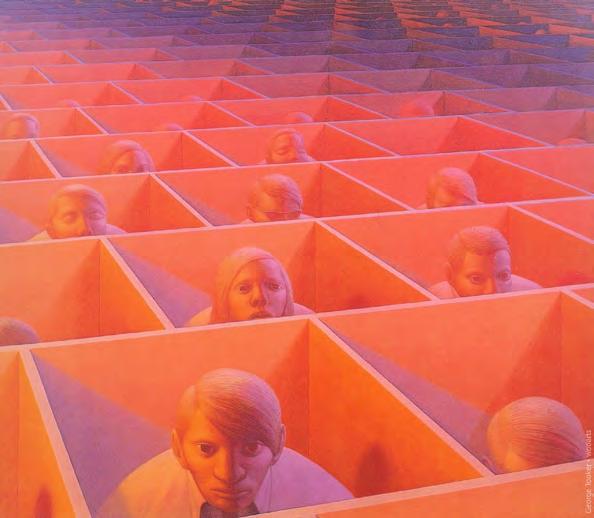

George Tooker’s mid-20th century paintings illustrate the emotions of everyday urban life. The abstracted forms depict the city-like qualities of street grids, mass versus void, and the repetition of squared units. The expressions and body language of his muses also emphasizes the emotional impact of life under urban conditions controlled by the gaze.

Anxiety has long been studied as a resulting factor of the gaze, as it triggers a sense of surveillance and unease. This anxiety was first contextualized during the post-war era with the introduction of large spans of glass combined with electric light within the domestic home. A loss of control was experienced, where the visual and psychological boundaries limiting the visibility of the body became blurred.

This anxiety is a direct result of seeing the gaze itself, a realization that we ourselves are the object within the gaze of the other. The resulting unease affects self-perceptions and behaviour in physical space, and is accentuated in the dense urban environment, a playground of eyes.

In Warped Space: Art, Architecture and Anxiety in Modern Culture, Anthony Vidler describes space as “a product of subjective projection and introjection, as opposed to a stable container of objects and bodies.” Viewing this statement through an urban lens, we can understand how the subconscious response of projection onto form and bodies in space can increase anxieties; this anxiety is being projected back on us through the gaze of another.

The gaze and its unnerving quality of imbalance is unavoidable under urban conditions. It is the consequence of the human condition combined with a layering of people, space, and activity. To be in urban space is to be both the beholder of the gaze and the subject of it. The infinite set of conditions for the gaze to occur in this context creates a system of endless anxieties that depends on the interaction of people and space.

Aside from the increased opportunity for a promiscuous, leering, or intentional gaze, does the city possess formal attributes that further amplify this anxiety of being viewed?

ANXIETY 10 B. BAYDOCK

SETS OF ANXIETIES 11 PRIVA[SEE]N

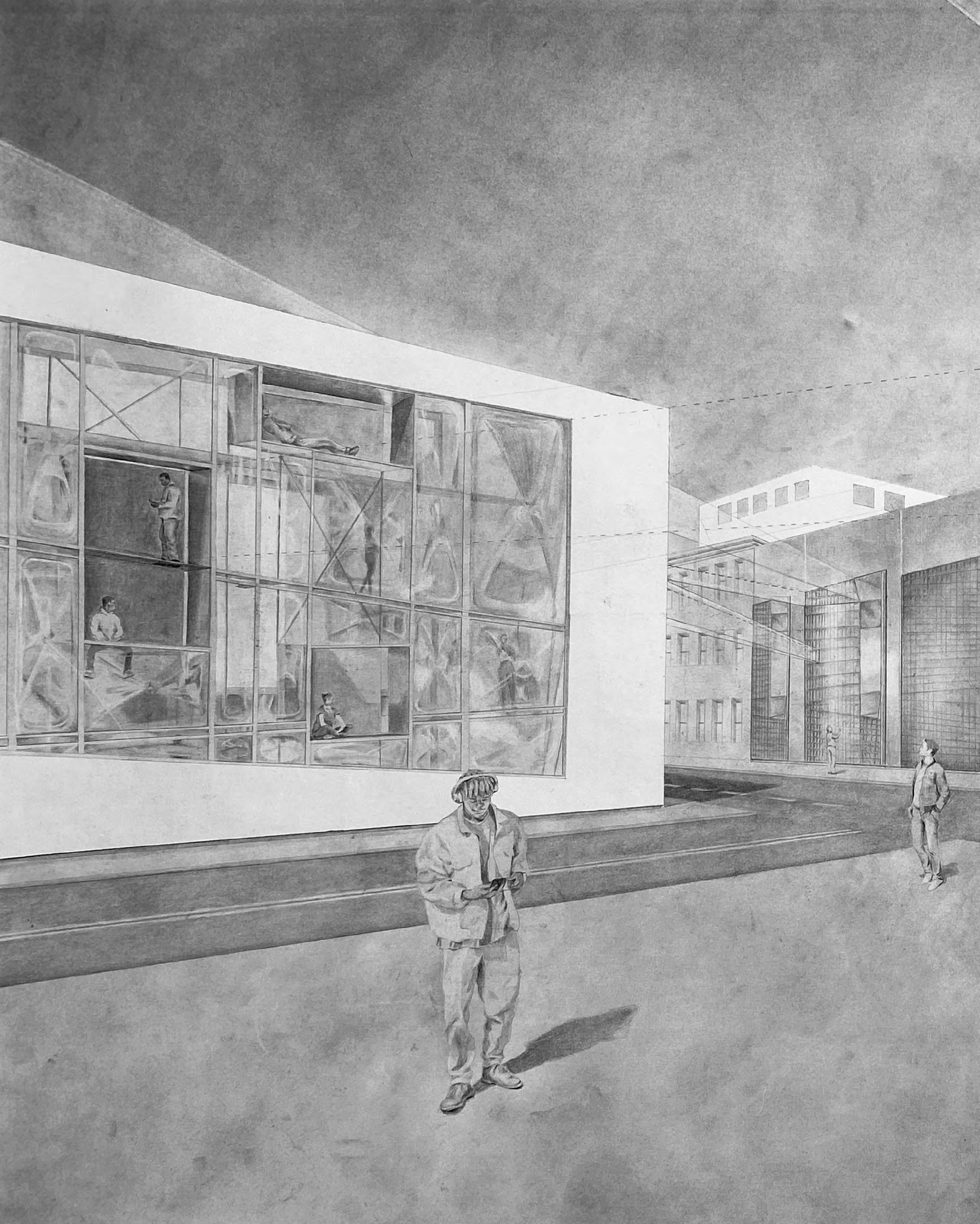

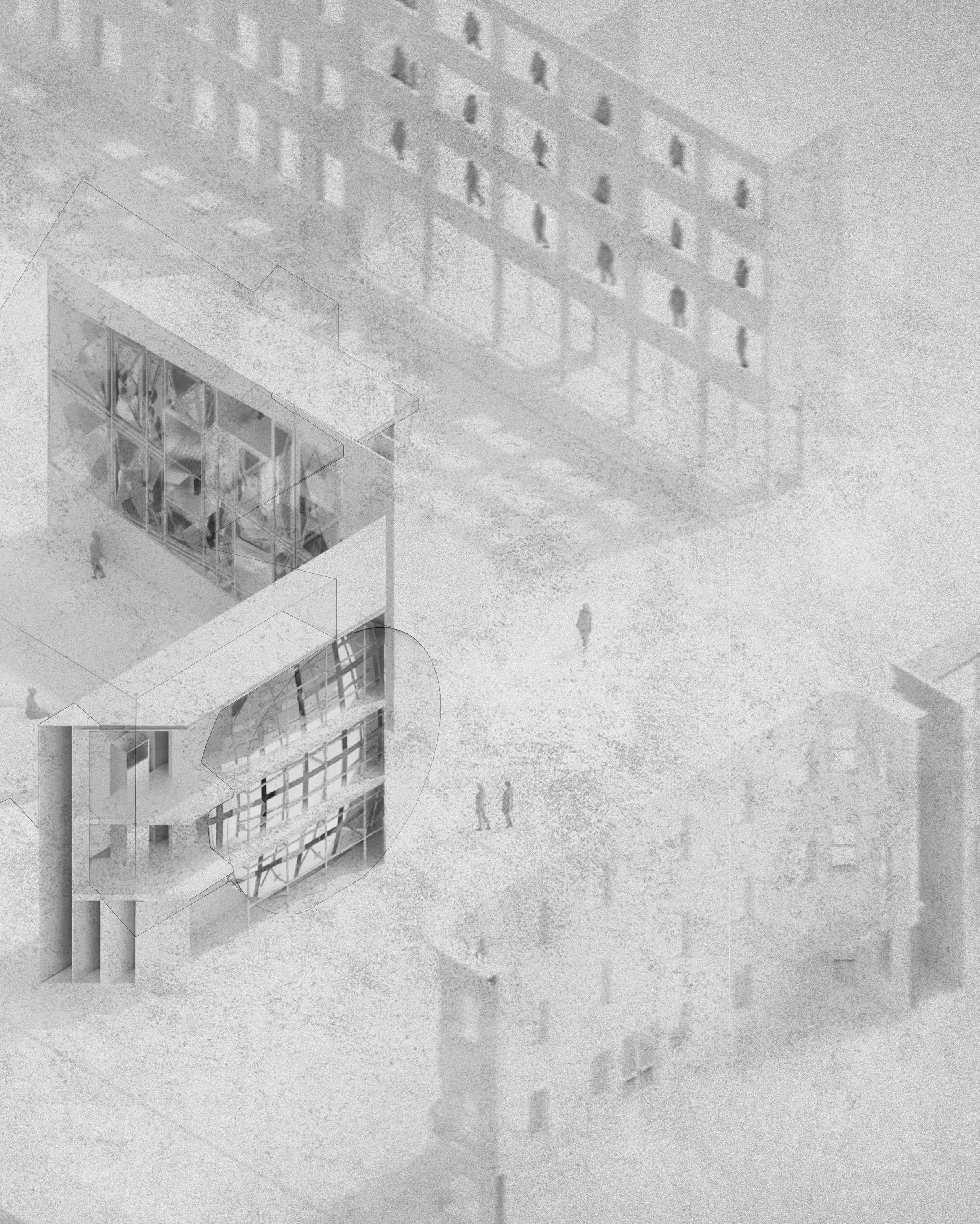

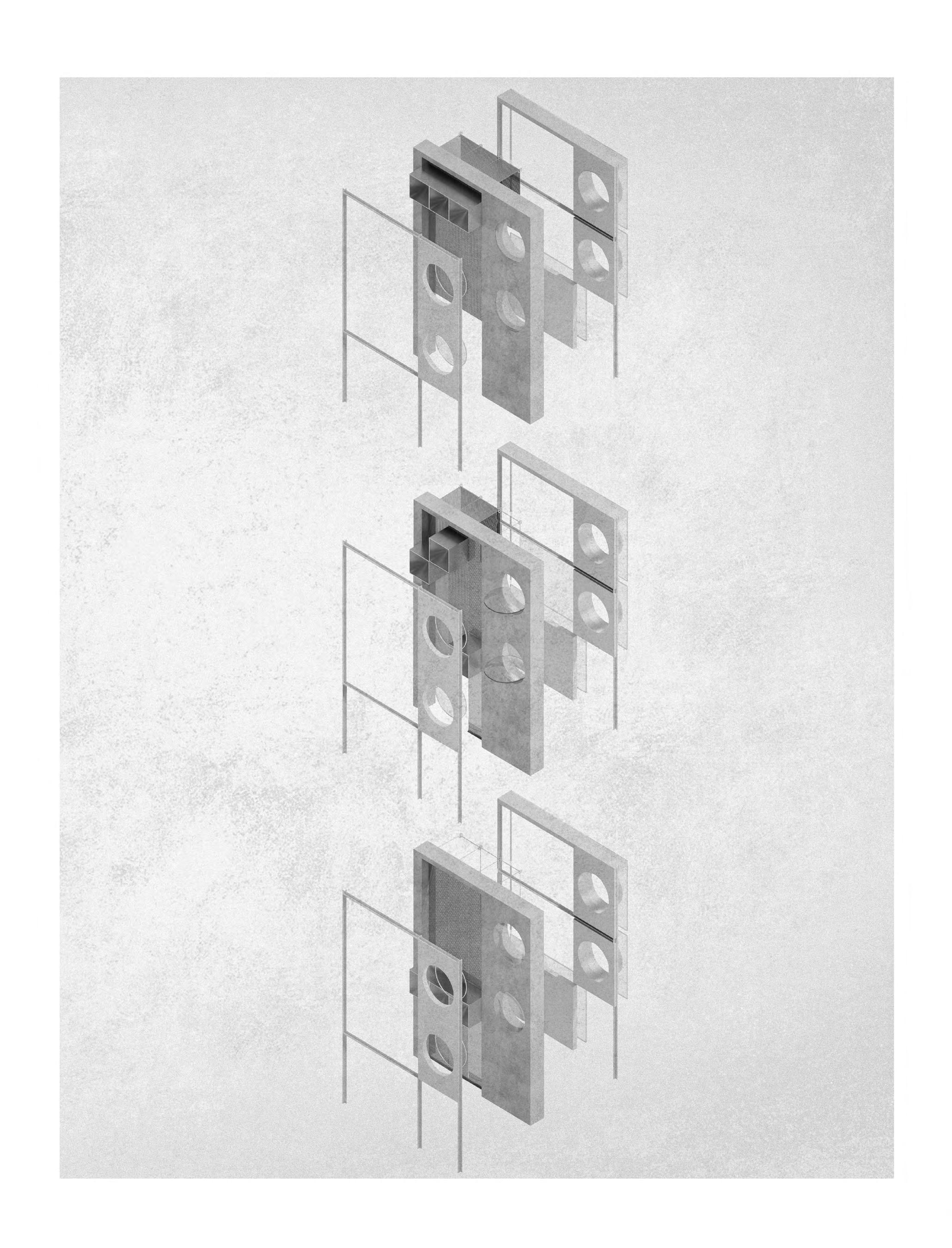

Sets of Anxieties, Physical Model, B.Baydock

What does the urban core feel like? What environmental qualities allow, create, and amplify these feelings? It is dense; it feels claustrophobic, it is vertical; it feels towering, it is repetitive; it feel isolating. The city can be broken down into parts, stage sets, or conditions that apply to many urban cores. These sets contain anxiety-inducing form or scenarios that are inherent to the current structure of urban living. The density creates an overlap of program that exists within an

intimate viewing range of one another. The vulnerability of a bedroom so intimately addressing the commercial business, sets up the opportunity for a leering gaze. The repetition in sterile, squared office apertures, alienates the viewer in an isolating gaze. Above all, the innate density and verticality of the city allows us to be viewed from all angles, increasing the sensation of surveillance. Within the city exists an underlying state of induced anxiety.

ANXIETY 12 B. BAYDOCK

THE URBAN GAZE 13 PRIVA[SEE]N

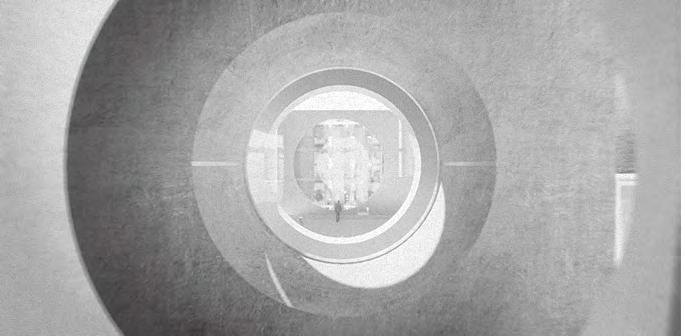

SequenceofGazes, Film, B.Baydock

THE URBAN GAZE

The city is a complex environment of omnipresent gazes. This condition allows for the urban gaze to be defined as a separate term. It is the existence within uncertain boundaries, receiving the gaze from varying angles via bodies as proxies of its anxious power. The urban gaze acknowledges a system of projections that are created by the field-of-view being forced through the mass and void of our built environment, partially or completely enveloping our bodies within its boundaries. In essence, it amplifies sensations of surveillance.

As social creatures we embrace the viewing pleasure of others, yet resist being the one in focus. For the system of the urban gaze to exist, we cannot remove ourselves as the subject of it.

‘Thegazecutsbothways’

Slavoj Zizek

ANXIETY 14 B. BAYDOCK

PRIVACY 17 PRIVA[SEE]N

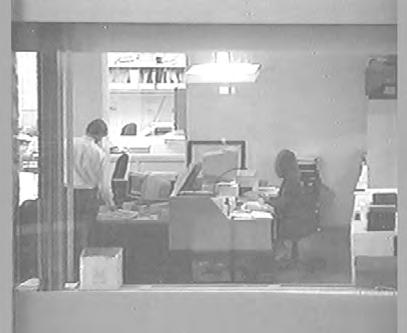

Diller Scofidio + Renfro, Overexposed, 1994

PRIVACY

The contemporary concern of urban privacy begins with the introduction of the mid-century floor-to-ceiling window that was intended to be an instrument of truth, a material capable of linking interior and exterior, public and private space. The ideal of living with unlimited vision quickly deteriorated, permitting observation from without and unveiling a dystopian picture of surveillance by the turn of the century.

Dillr and Scofidio’s 1995 Overexposed, deals with this tension between the modernist visuality and the gaze of the observer. The short film captures the screen-like apertures of the signature 20th century curtain wall façade of Los Angeles’ Pepsi Cola building, slowly panning from one office to the next. An earie narration describes the actions of the subjects beyond the glass, combining observation and speculation.

Not only does this speculative piece question the ethics of viewing and the definition of truly private space, but it highlights the observer’s attraction to stimuli that hyper-sightedness allows. We are socially conditioned to view the happenings of others, and the

architectural lens’ that exist within the built environment dicate the boundaries of this relationship.

Today, within the North American urban context, physical privacy standards remain rather defined. Divisions between exterior and interiorities leave little room for variations in privacy levels. The window is open or closed, structure or void. These openings are fixed, impersonal, the level of agency over viewing is predetermined.

Dillr and Scofido refer to glass today as ‘neither the euphoric material that promises to seamlessly connect private and public space, nor the menacing surface defining controller and controlled. The pathologies have inverted: the fear of being watched has transformed into the fear that no one may be watching.’

As we move forward into an era of dense cohabitation, can we expand the levels of privacy we choose to live within? Is there benefit in capitalizing on an inherent viewing culture, identifying spaces of varying qualities of visual experience and therefore privacy.

PRIVACY 18 B. BAYDOCK

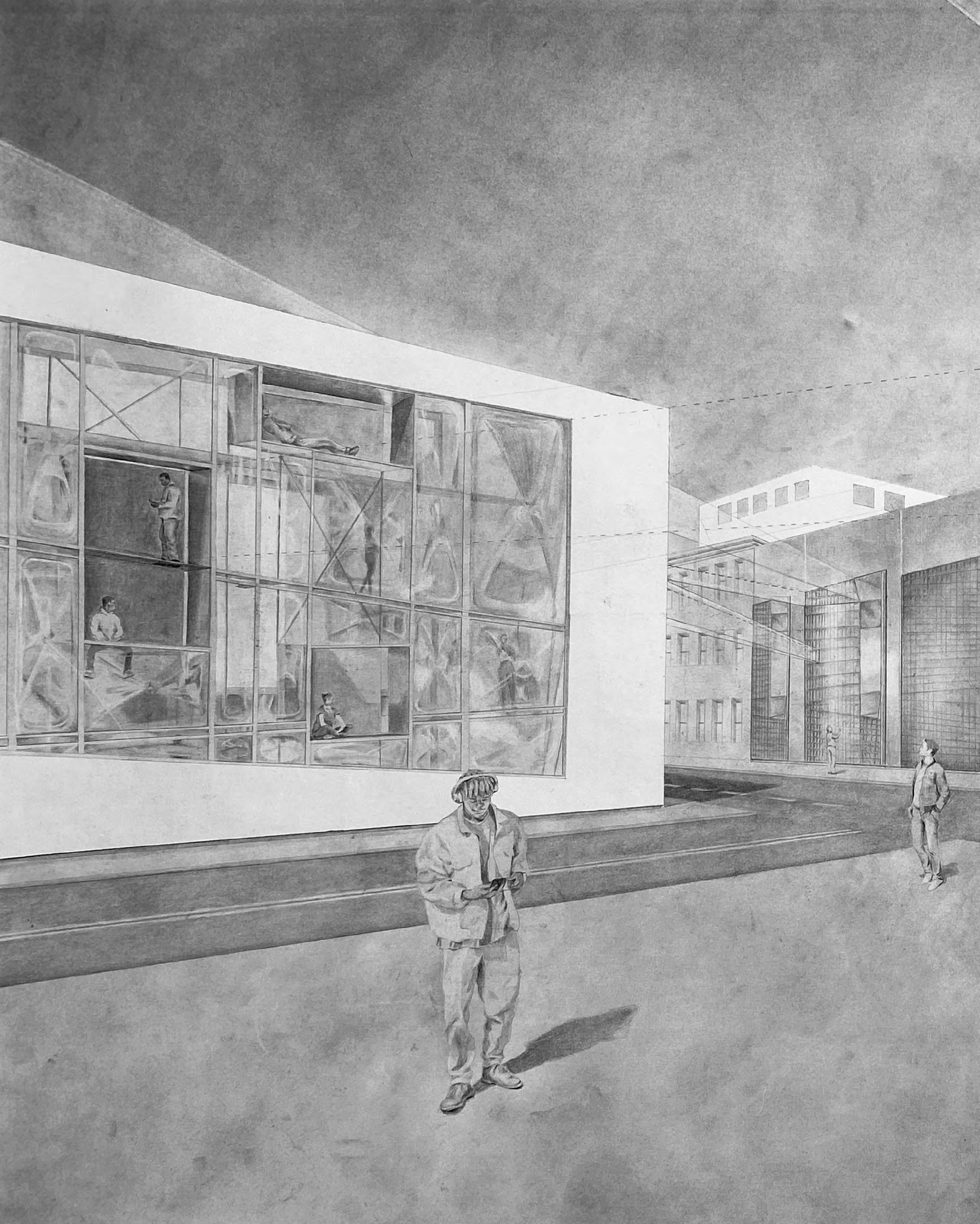

A SEQUENCE OF GAZES 19 PRIVA[SEE]N

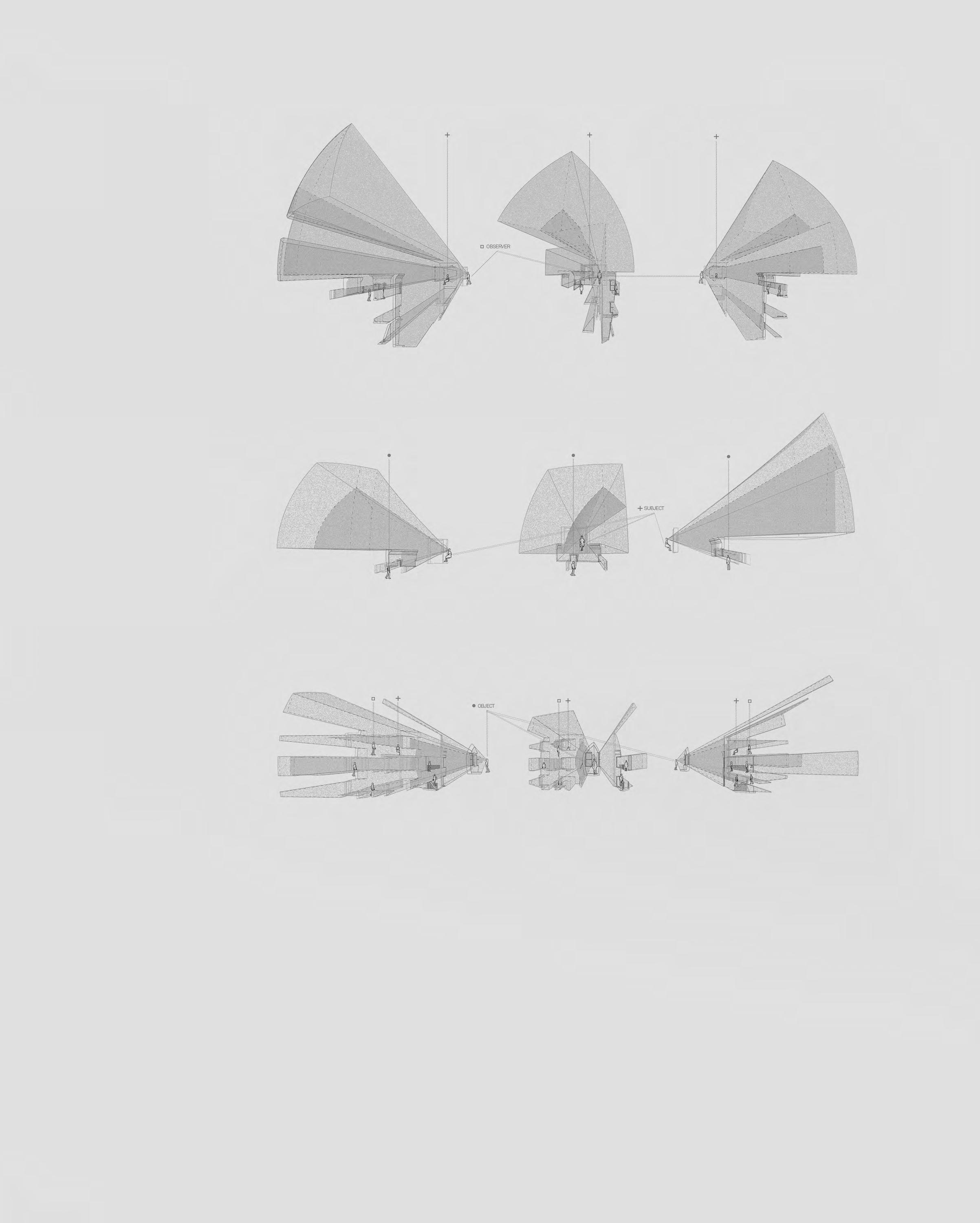

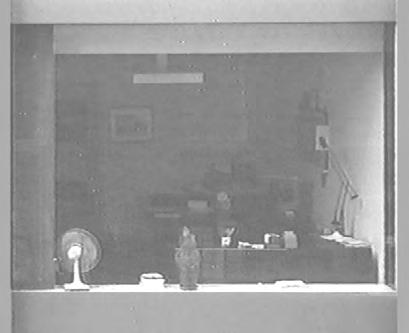

The creation of a typical city block based on the reconstruction of three New York-set Hopper paintings, acts as a set to understand a series of visual interactions that endlessly take place. A sequence of gazes formalizes the gaze of the observer, the gaze of their subject, and the gaze of the object who stares back. The projection of the visual field, combined with its reaction to the openings and mass it passes through and halts against, constructs a

unidirectional gaze. When in series, an invisible system arises, a temporary structure that reveals places of decreased privacy, spaces of varying degrees of vulnerability. This system expands, linking windows, stretching across streets, encompassing a city. A series of gazes highlights the invisible connections that exist within the urban context and confirms the anxious notion that we are more often than not, the object of the gaze.

PRIVACY 20 B. BAYDOCK

FRAME THRESHOLD PORTAL

PASSAGE

CLEFT CHASM VALVE VOID APERTURE 21 PRIVA[SEE]N Aperture , Hand Drawing, 02/10

OCULUS

APERTURE

Symbolically an aperture can be described as a frame, a threshold, a portal, a passage, an oculus, a cleft, a chasm, a valve, or a void.

An aperture controls our understanding of internal and external space through its defined borders. Louis Kahn describes the conception of architectural design as beginning “when the walls parted, and the columns became,” alluding to the birth of the aperture. Essentially, an aperture is an opening between spaces, a threshold that defines the passage of light, air, or bodies, and has the power to frame the world around us, and the people within it.

Baumgartner & Uriu at SCI-Arc define an aperture as an “object within a larger building object that differs from its host in terms of morphology and performance.”

The power of an aperture’s ability to frame lies within its inherent quality of opposing mass. As a break in a wall, surface, or skin, the aperture demands attention as a feature of focus, regardless of the presence of a view or object to frame past its boarders. The

presence of this object however, gives the aperture its poetic duty beyond technical performance, to feature a view past its boundaries.

While the aperture emits light, allows passage, and mediates space, its most intimate feature is its ability to frame in relation to the body. The aperture is the physical means by which we give and receive the gaze in the urban context, as well as the medium which shapes our understanding of public and private space.

The projection of the gaze through apertures dictates how the body on either side of it is viewed. The treatment of its boarders, materiality of the skin, and the scale to which it responds, mediates, and can manipulate how we are perceived. This perception either enhances or diminishes our sense of privacy in relation to the external gaze.

Can apertures negotiate varied lines of privacy through form and detailing? How can apertures further respond to both interior and exterior bodies in space, creating a visual conversation between urban life?

APERTURE 22 B. BAYDOCK

ToBetheSubject, Hand Drawing, 03/10

PRIVA[SEE]N

B. BAYDOCK

APERTURES AS MESSENGERS 25 PRIVA[SEE]N

AGlimpse

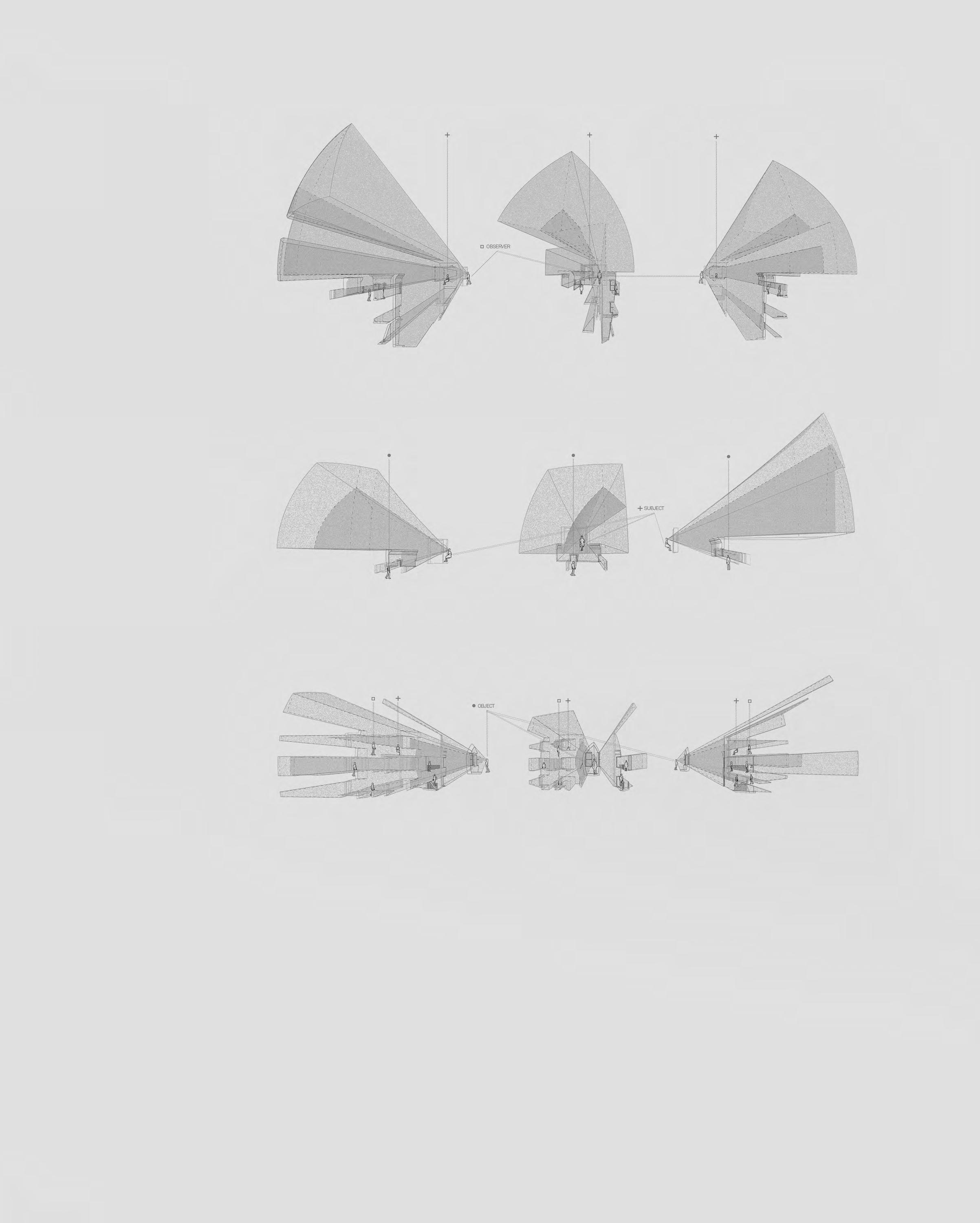

Apertures dictate how an occupant views outwardly and, conversely, if and how that occupant is viewed publicly. Using the vocabulary of the gaze, prompts were used to design apertures that respond to varying qualities of viewing.

What does a glimpse look like? To glimpse is defined as the act of momentarily acquiring a partial view of a stagnant or moving subject. A fleeting moment. A series of fragmented surfaces are

layered and punctured to provide a depth in space that allow for only select curated moments of unobstructed viewing. Both the interior inhabitant and the exterior observer are only able to visually transcend the aperture from two selected positions. Otherwise, the object appears as an impenetrable barrier, only allowing for the passage of light. In the off chance both participants move past the aperture at the same time, both bodies are framed in a fleeting moment.

APERTURE 26

B. BAYDOCK

PerformanceofStreetApertures,Physical Model, B.Baydock

A STAGE FOR VIEWING 31 PRIVA[SEE]N

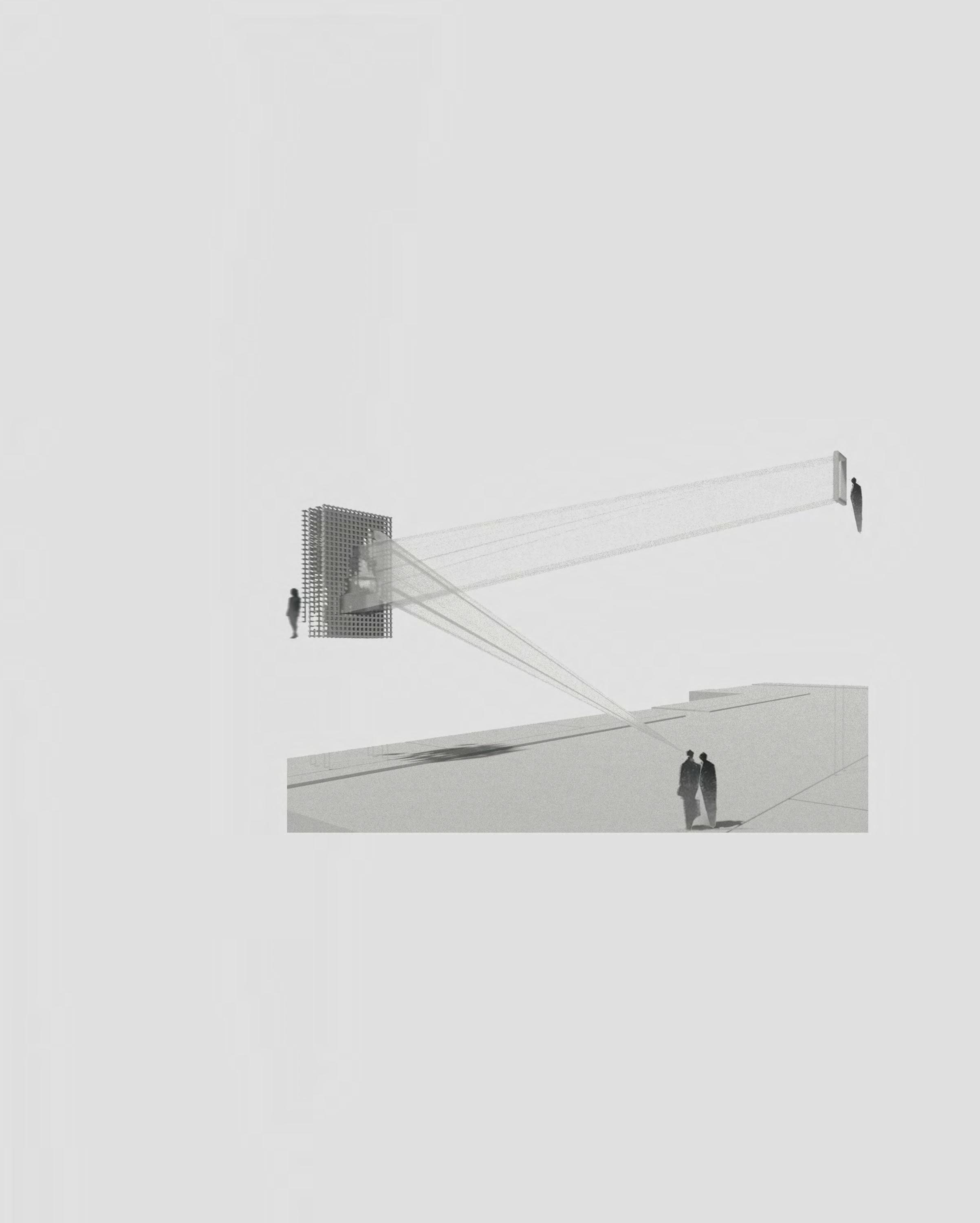

As the set of apertures are arranged within a street-like urban grid, a matrix of viewing pleasure emerges.

The intent behind this organization is to simulate the potential dynamics of moving through a public space where the street-wall becomes undefined, and a captivating stage for performance. If the urban gaze is determined by the apertures, can their function be shifted to frame an exterior view, as well as the

the occupant behind? Is there a playfulness that can be accomplished?

The design exercise opposes how we currently see bodies within private space from a public position, and speculates on how this interaction could be manipulated or designed to enhance pleasure while in some cases adding to a spectrum of privacy levels for the inhabitant.

APERTURE 32 B. BAYDOCK

AN ACCEPTED CULTURE OF MEDIATED VIEWING

THE DIGITAL GAZE 33 PRIVA[SEE]N

THE DIGITAL GAZE

As the gaze in physical space is analyzed, the current social context of the digital gaze forms a direct parallel in terms of a collective viewing culture. How do we view differently in physical and digital space?

In terms of imagery, a shift in social visualities can be attributed to three key points in history, the invention of the printing press, which allowed for reproduction, the emergence of photography, capturing the reality of a moment in time, and finally the creation of the internet, spurring the beginning of an era defined by a mass circulation of digital imagery. As capabilities and demand have increased, a social culture has emerged of mediated viewing that we have accepted on a mass scale.

Whether it is the marketing of a brand, advertisement, or the digital representation of the lives of others, we communicate through images and are either directly or indirectly subjected to this gaze on a daily basis.

The difference in digital viewing as opposed to physical viewing however, lies in the ability to manipulate perception

through the mediation device of a screen. This mediation allows for the distortion of an image’s reality, filtered, and framed to skew our perception of the object, subject, or person on the other side. The imagery we consume is also curated by the creator, who maintains agency over what we are viewing and how we do so.

The digital gaze possesses an insidious underpinning, however, allowing for unequal power dynamics and the ability to view without being viewed. This tension leads to the question over digital privacy, as the culture has trended towards one of a life on display. This is what Scribano and Lisdero refer to as hypervisuality, the condition of existing within a system of excessive, obsessive, and accepted viewing.

If we as a society have accepted this generational shift towards mediated viewing in the digital realm, how could this approach to spectatorship be applied to the physical urban environment?

How would the interface of the public domain shift to possess the qualities of digital viewing?

THE DIGITAL GAZE 34 B. BAYDOCK

SKINS AS A RESPONSE 39 PRIVA[SEE]N

SKINS AS A RESPONSE

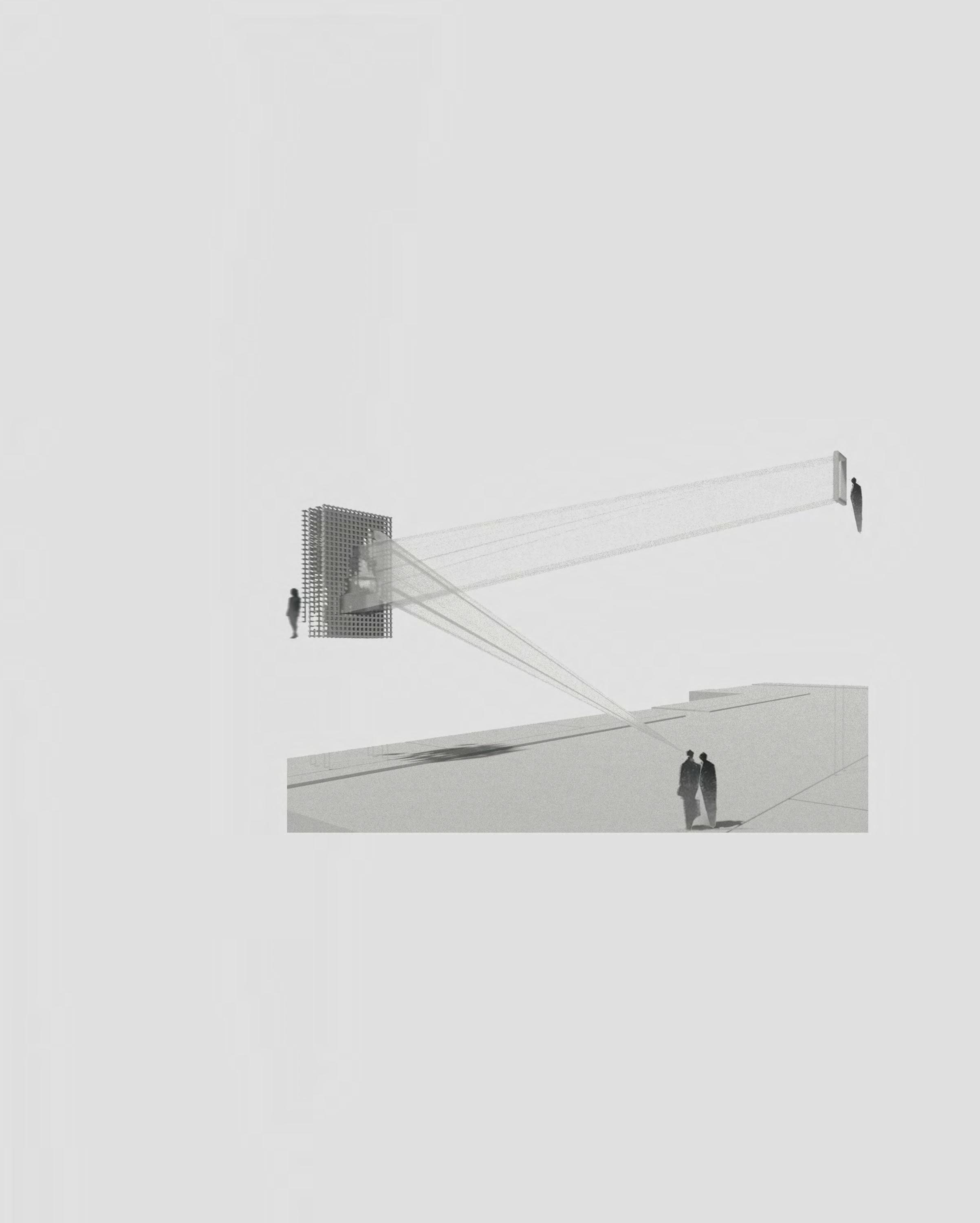

If the intent is to apply the qualities of digital viewing to the built environment, and the mechanism between private and public is the aperture, then the design response is the building skin.

As the physical mediation device of the city, the building façade determines our perceptions of interior and exterior persons, and therefore can be manipulated to produce heightened gratification of voyeurism for both occupants and observers.

As discussed, the digital gaze produces a shift in our patterns of viewing, and these dynamics can be used as a framework for speculative façade design.

Can a façade be adapted so that the user can see and not be seen? What does the materialization of living on display look like, how can this inform spatial qualities?

Can the ability of the digital gaze to distort an image be translated into the apertures of a façade? Does this distortion affect perceptions of privacy? Can the agency over digital viewing

be reflected in the function of façade apertures, and how does this flux in view affect users and observers? What sensation does viewing through a series of manipulated facades produce?

There is a sinister underpinning to the notion of viewing in today’s context, whether it’s the silent stalking of digital imagery, or the viewing of an intimate moment in the apartment across the street, the gaze possesses unequal power dynamics and induces anxieties.

However, there is an undeniable pleasure in viewing, that can perhaps be dramatized, exaggerated, or manipulated to create a performance of activity that shifts this voyeuristic perception and produces a more engaging and dynamic environment.

Using digital viewing as a framework, the design intent is to create a speculative street-scape consiting of altered facades, where viewing pleasure is the main design-driver.

Can façade design expand to create sensorial viewing experiences for both users and viewers?

SKINS 40 B. BAYDOCK

RecluseOpposingElevations, Hand Drawing, 05/10

RECLUSE 43 PRIVA[SEE]N

RECLUSE

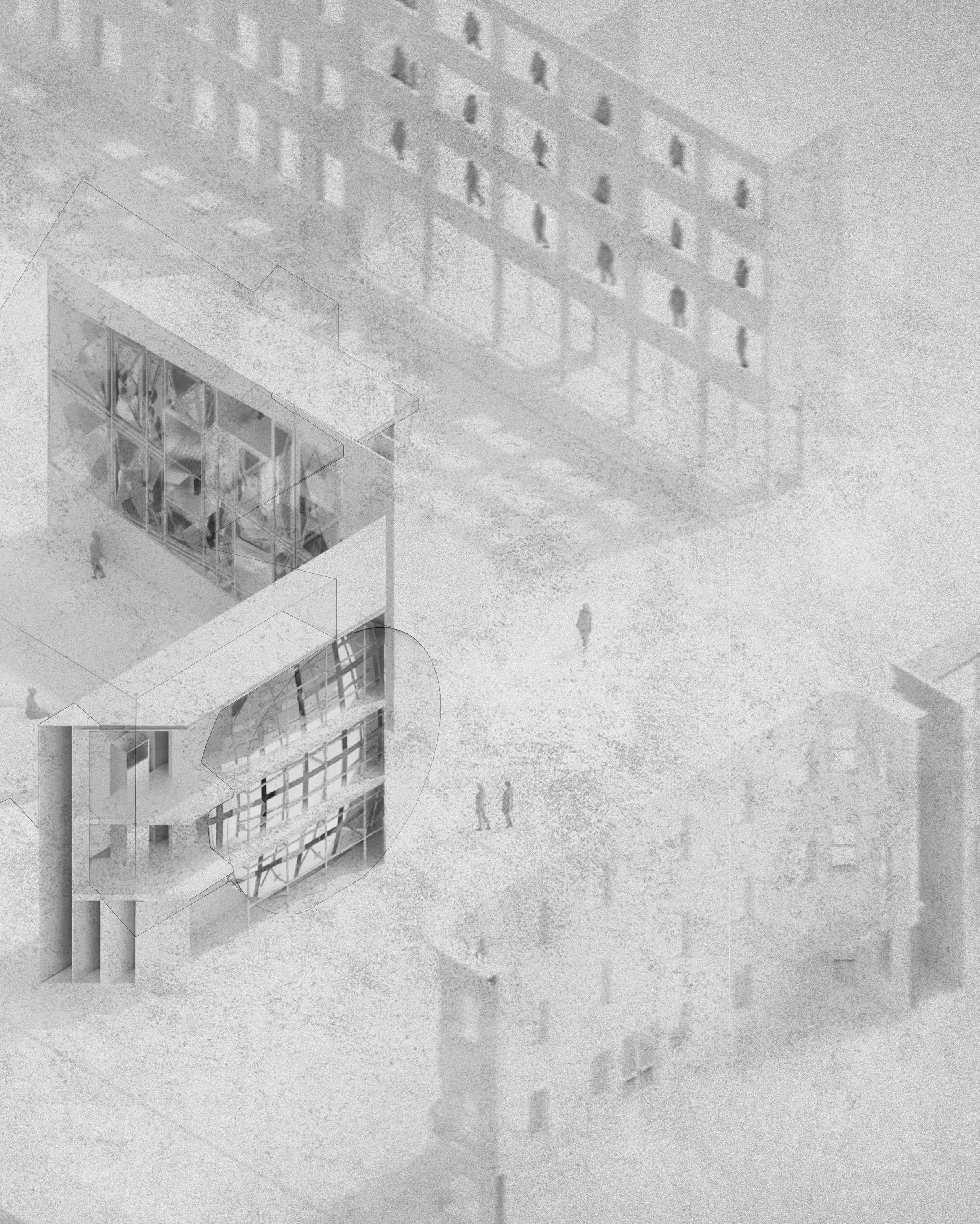

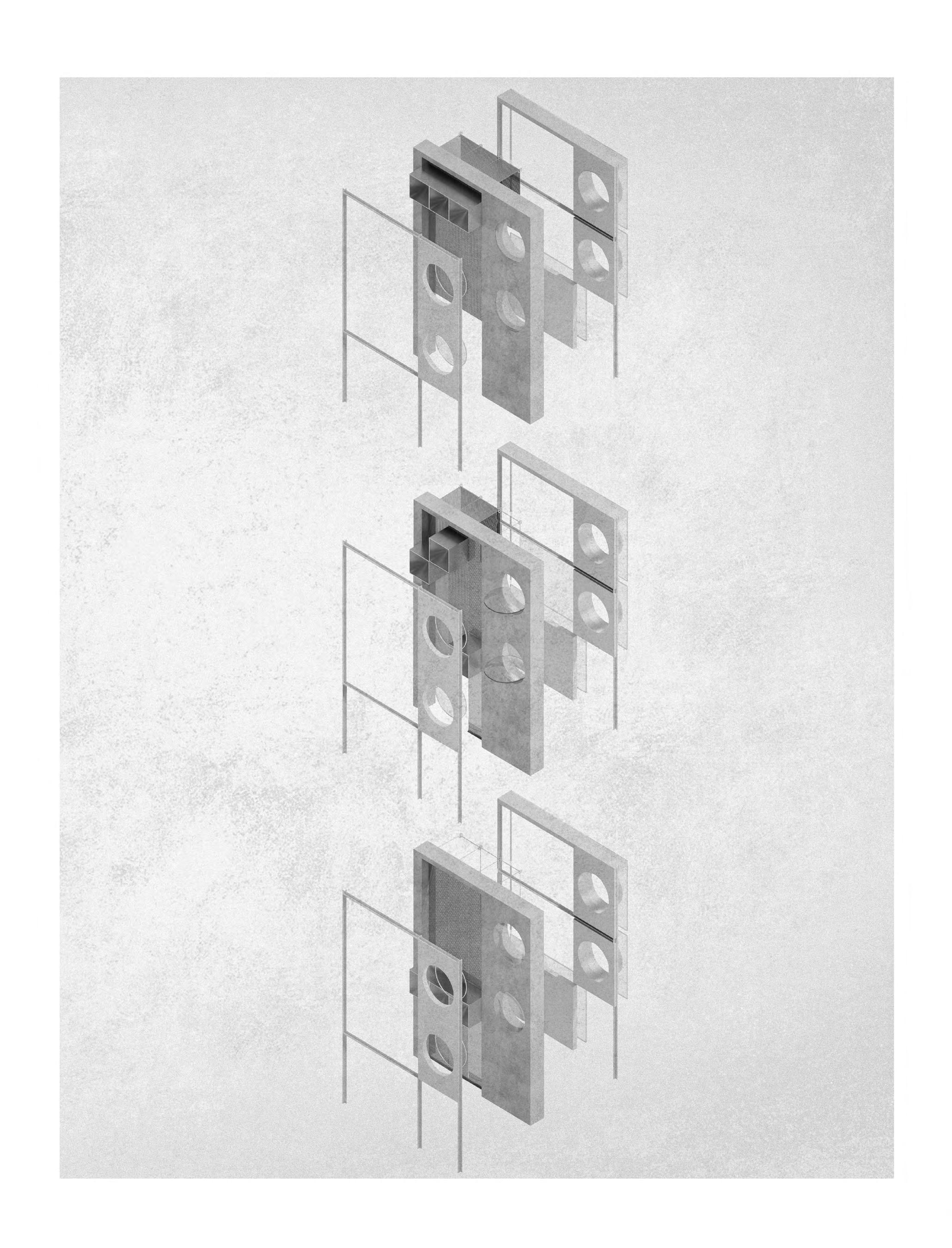

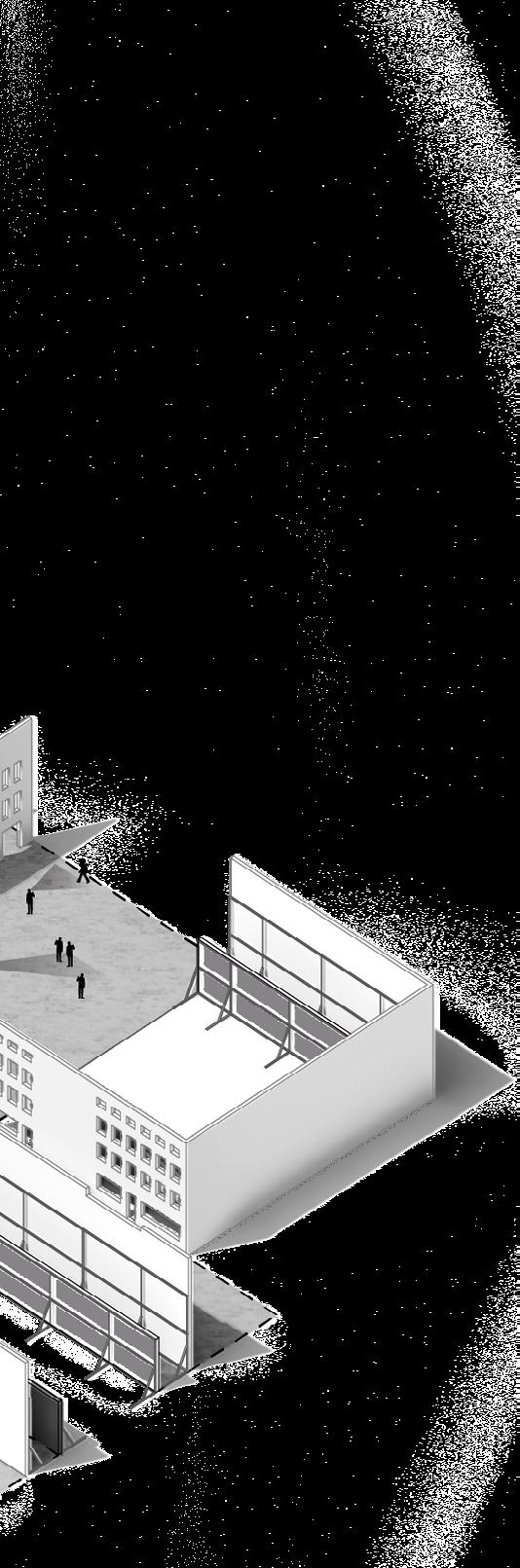

The digital gaze, in comparison to its physical counterpart, allows for its viewer to see without being seen themselves. To look at their muse through the veil of a screen, where the power balance is shifted in their favour. Can the skin of a building, dividing private from public space be seen as a similar mediation device, disguising the gaze of the interior participant? The layered façade physically materializes the projection of one’s field of view, forming

cone-like elements that collectively form a structural screen. The apertures protrude through the most interior layer, forming coin sized openings for the occupant to view through, while the projection of the form simultaneously shields them from the opposing gaze of the exterior spectator. Voids between interior panels of the façade allow for inhabitable spaces for users to linger in, however doing so allows for a greater risk of exposure to the outward gaze.

SKINS AS A RESPONSE 44 B. BAYDOCK

RECLUSE 45 PRIVA[SEE]N

Recluse Section, Hand Drawing, 06/10

SKINS AS A RESPONSE 46 B. BAYDOCK

DisplayElevations, Hand Drawing, 07/10

DISPLAY 49 PRIVA[SEE]N

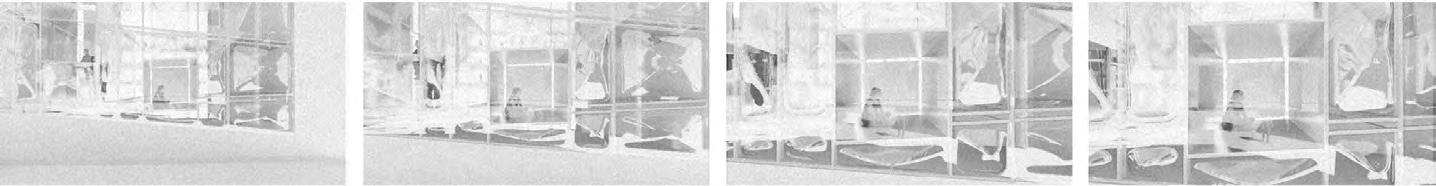

Conversely to the dynamic of seeing without being seen, the digital gaze simultaneously allows for the notion of living as theater. The idea that there is an audience silently viewing our carefully prescribed content. What would a façade that exaggerates the concept of livingon display look like? The structural framing of Display is dictated by the opposing views of Recluse, where the composition in its innate construction is at the mercy of the gaze of the other. These slightly

shifted apertures are the only habitable spaces with a clear view outwards for the user, forcing them to be seen in order to see out. The remaining panels of the layered skin employ pillowed glass to distort and modify both the gaze of the interior and exterior spectator. The façade forces the user to engage in the theater of the city by manipulating the positioning of unobstructed views, thus baiting the occupant into becoming the subject of display.

SKINS AS A RESPONSE 50 B. BAYDOCK

DISPLAY

AperturetoAperture, Film, B.Baydock

DisplayIsometric, Hand Drawing, 08/10

DISPLAY 51 PRIVA[SEE]N

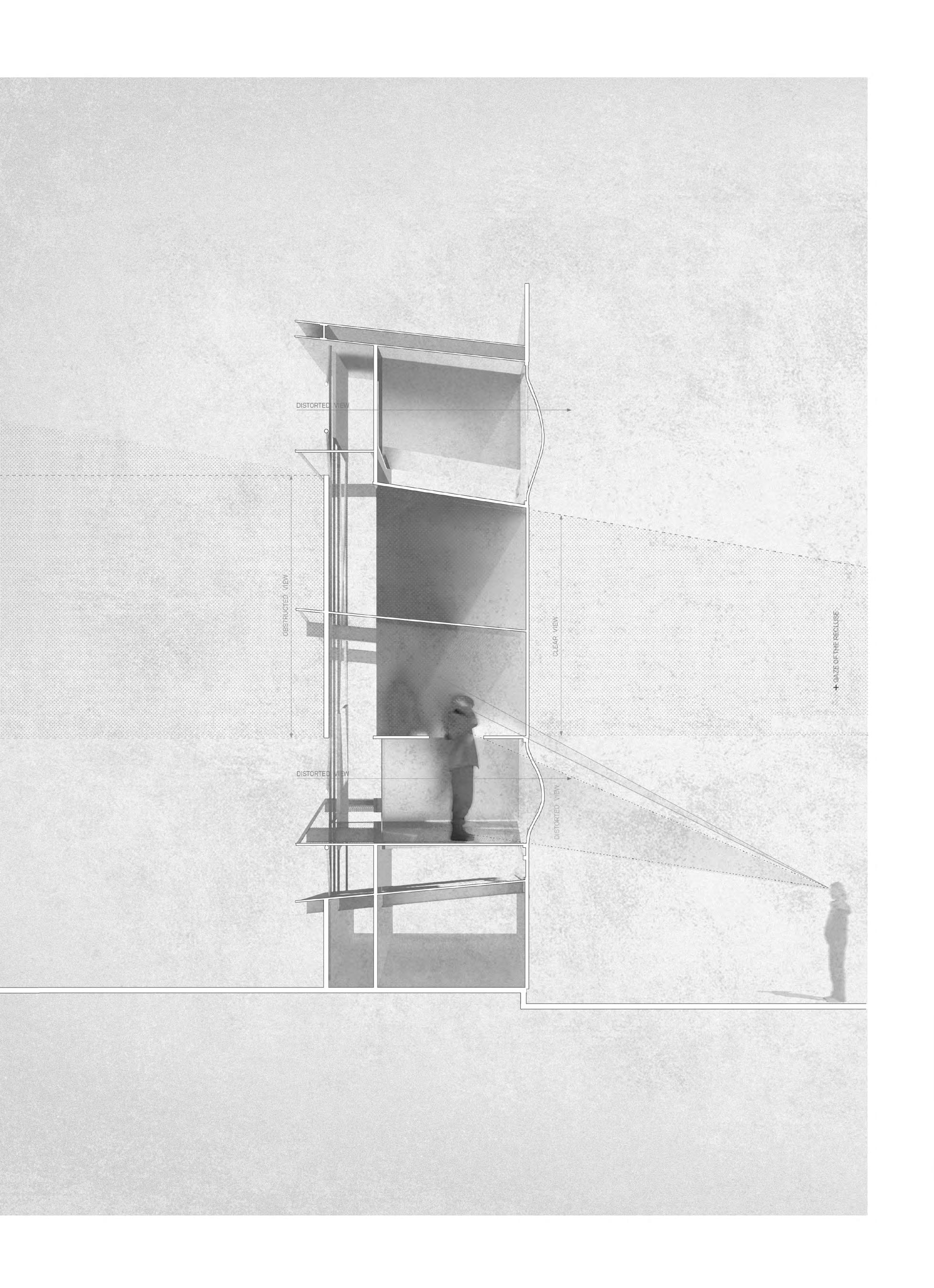

DisplaySection, Hand Drawing + Digital Edit

SKINS AS A RESPONSE 52 B. BAYDOCK

DISPLAY 53 PRIVA[SEE]N ViewingSquareSection-ReclusetoDisplay

SKINS AS A RESPONSE 54 B. BAYDOCK

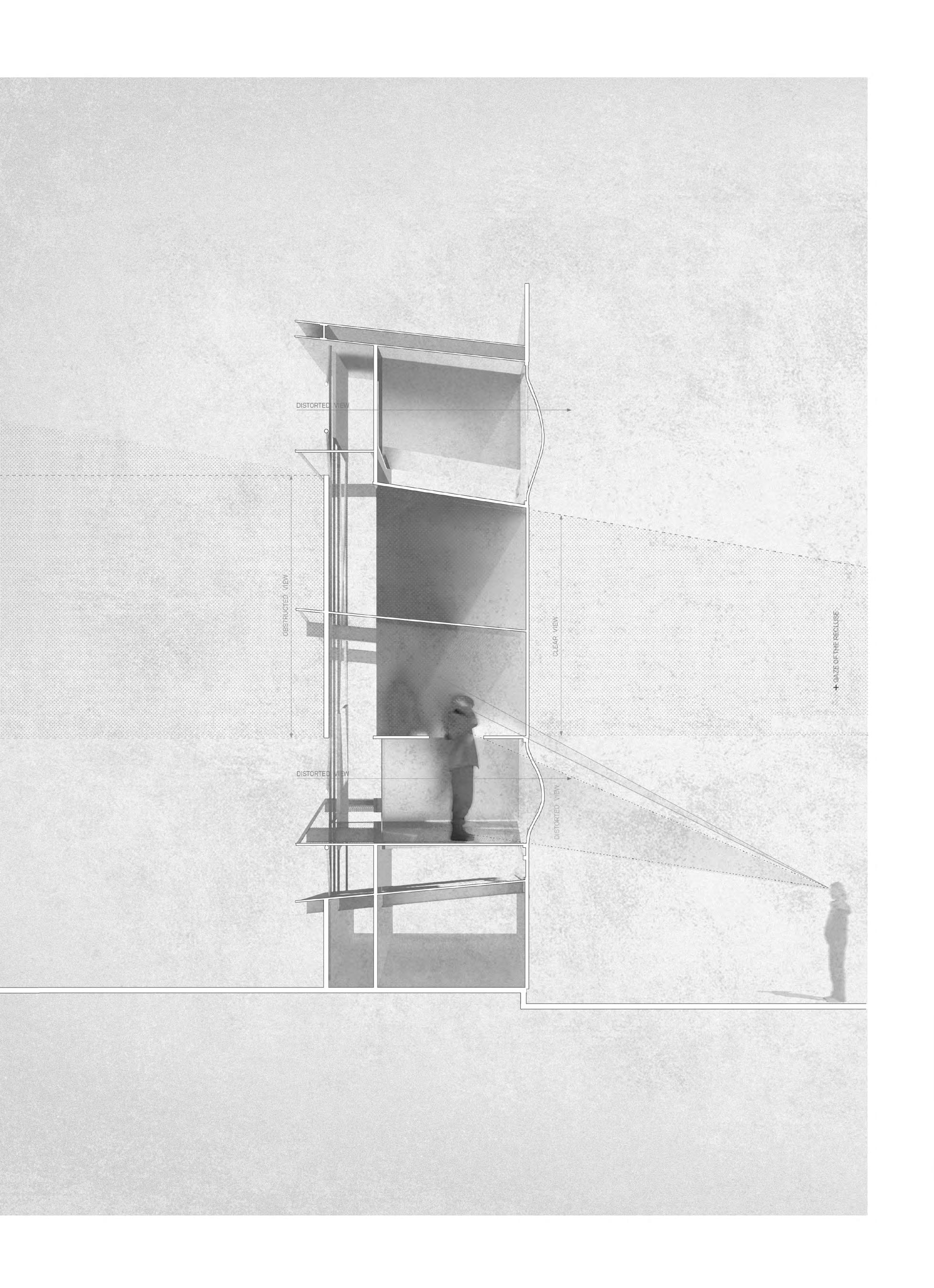

Distort Section, Hand Drawing, 09/10

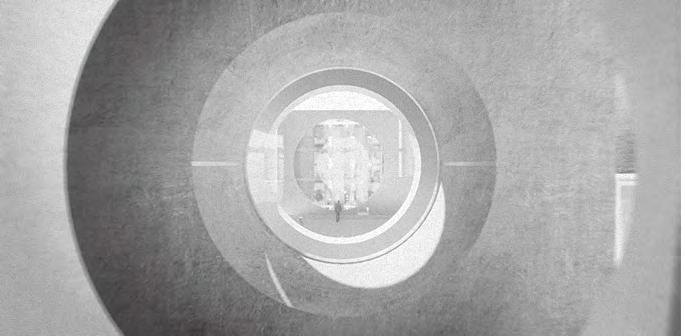

DISTORT 55 PRIVA[SEE]N

The digital gaze at its core perhaps, is a mechanism of manipulation. A framed and filtered version of a perceived view. Can a physical façade assembly alter our gaze to shift our understanding of relative positioning and thus, reality? The layers of the Distort façade work to manipulate ones understanding of space on a vertical and horizontal axis. The user exists within the cavity between a curvilinear mirrored structure and undulating glazed panels. The sensation

created questions our understanding on interior and exterior space, and where exactly we exist between them. On a vertical axis, enclosed apertures within the cavity extend from ground level upwards, with opening at both ends. Inserted reflective panels within the apertures reflect the view within the shaft. A street level observer witness activity above them, while the interior user sees a below knee-level frame, thus distorting their perception of position.

SKINS AS A RESPONSE 56 B. BAYDOCK

DISTORT

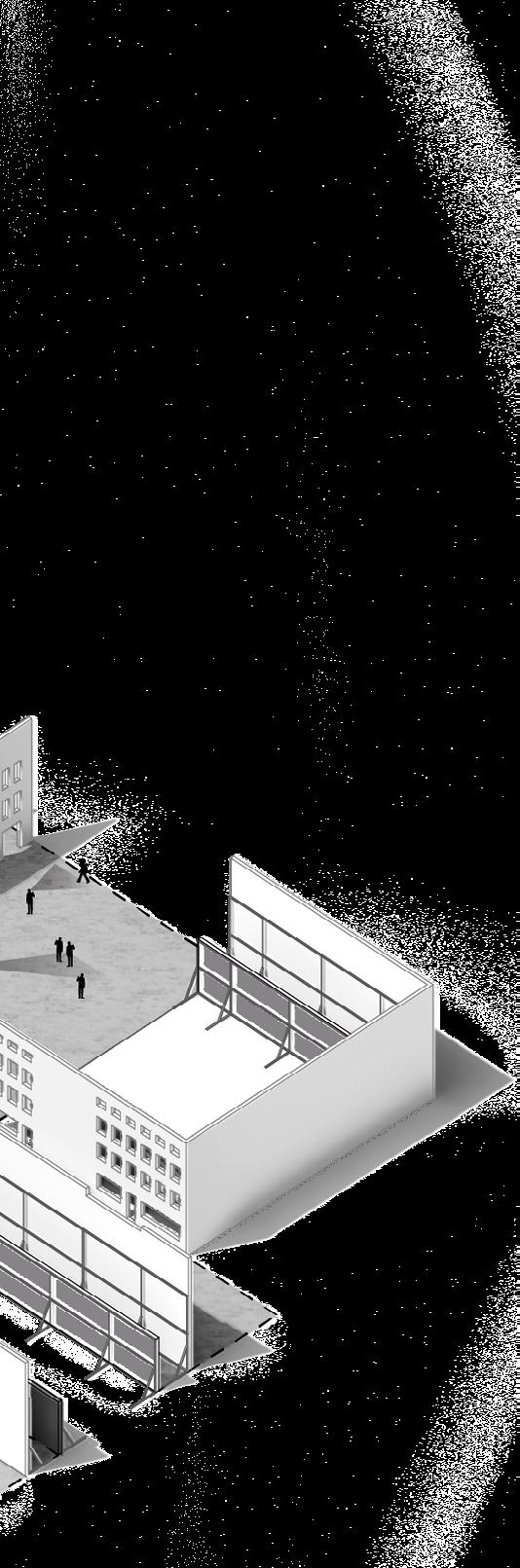

CONTROL 57 PRIVA[SEE]N Control Isometric

The digital gaze, however, also allows for agency over the lens one is viewed through. Can this notion be applied to the apertures of facades to not only shift the power dynamic of control from the observer to the object of the gaze, but create engaging city street facades through movement. The façade of Control uses layered apertures that employ motion to create, define, and manipulate space, and how we are viewed through it. A series of apertures suspended within

a pulley system, weighted by chain curtains are activated by the interior user, and move vertically past multiple floor plates to shift what part of the body is framed. Simultaneously, the chain veil creates or defines space as a result of the moving apertures. The façade also layers light-wells and materials of varied thicknesses to create habitable spaces to be viewed through. Pivoting apertures re rotated by the user to determine if their image is defined or screened.

SKINS AS A RESPONSE 58 B. BAYDOCK

CONTROL

Facades and apertures are fundamentally mechanisms of performance, mediating environmental conditions. This definition, however, can be expanded to include the performance of human interaction.

The skins of our environment, dividing private from public, have the ability to manipulate our perception of those around us, shedding light on our shared commonalities. Our streetscapes have the ability to become dynamic spaces for performance, inviting the gaze from both sides.

CityofGazes, Hand Drawing, 10/10

The fear of being watched has transformedintothefearthatnoonemaybewatching

- Diller Scofidio + Renfro, Overexposed

Hopper, Edward, NewYork Office, 1962.

Hopper, Edward, NewYork Office, 1962.