REVEAL COURAGE

Welcome to the inaugural issue of the new Branson Magazine! We’ve reenvisioned our former magazine to create a brand-new publication that is truly for everyone. Each issue will center on a key theme drawn from the richness of our core values, mission, and community life. We’ll tell our stories showcasing the myriad talents of the people of Branson, including award-winning writers, photographers, and illustrators.

When we selected “Reveal Courage” as the theme for this first issue, we weren’t just thinking about the courage it took us to launch something new. And yes, as the first of Branson’s core values – courage, kindness, honor, purpose –courage was a logical starting point. But there’s much more to it than that.

Courage has many faces and comes in many forms – large and small, visible and invisible, ordinary and extraordinary. In this issue, we explore how it shows up at Branson and among our graduates.

Why does courage matter so much?

In an increasingly complex and polarized world, courage may well be the most important trait our students will need to lead and thrive in the future. And for both students and adults in our extended Branson family, I imagine that courage will play into every corner of our lives. We will all need to act courageously, as a matter of course, to create a more liveable planet and empathetic world.

We hope this magazine sparks your curiosity, provides inspiration, and brings you pride in being a member of this exceptional Branson community.

Chris Mazzola, Head of School

By Julia Flynn Siler ‘78

By Julia Flynn Siler ‘78

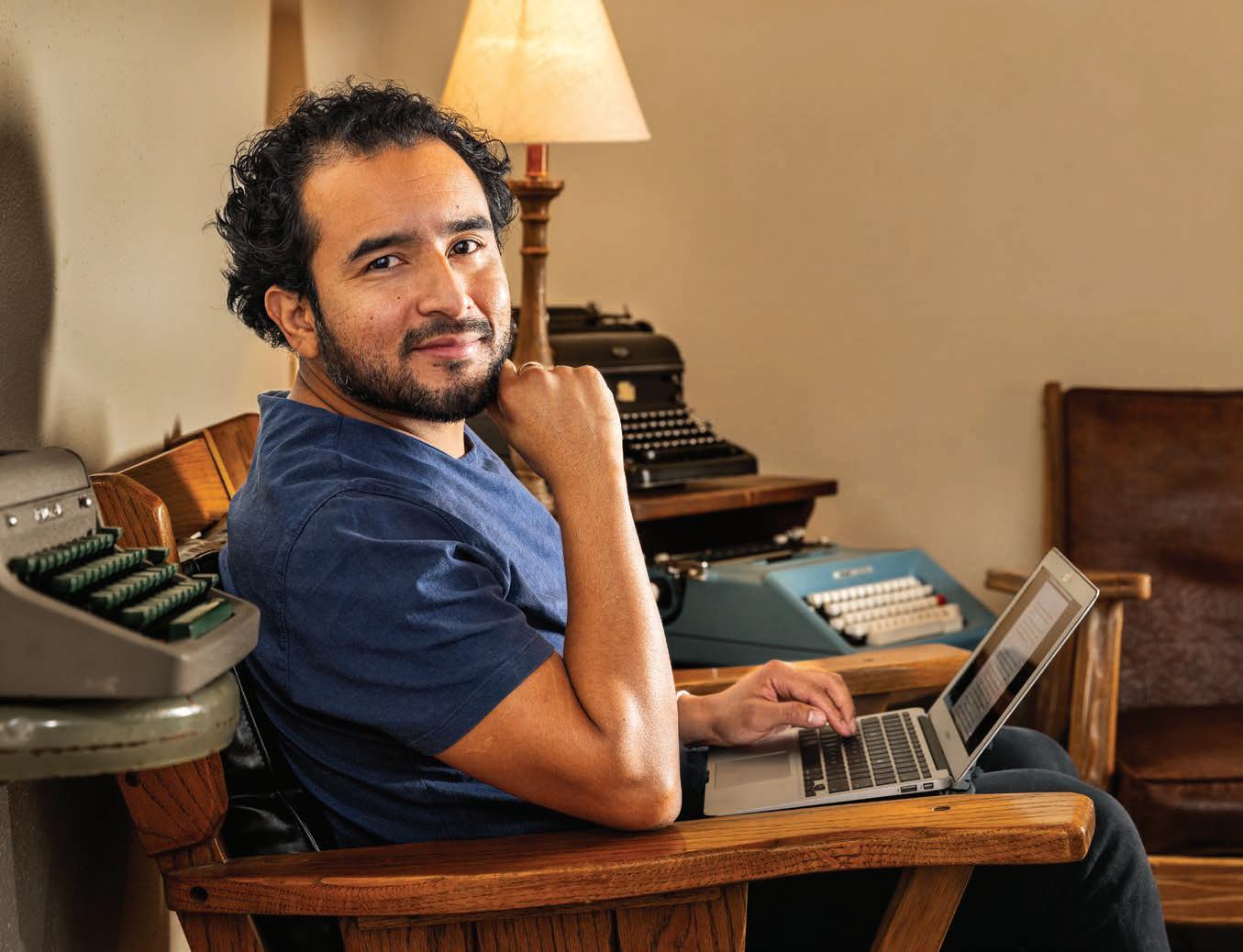

Javier Zamora ‘08 first stepped onto the Branson campus as a nine-year-old, wearing cleats and an oversized blue jersey, and speaking almost no English. His mother memorialized that moment in November of 1999 by snapping a photo of her only child, wearing a watchful expression.

Few at the scrimmage that day knew about the trauma that Javier had undergone less than five months earlier. In June of 1999, he had completed a harrowing journey from El Salvador through Guatemala and Mexico to join his parents in the U.S. Trekking through deserts and encountering uniformed men with machine guns, he relied on help from strangers along the way. He wrote about his experience more than two decades later in his searing bestselling memoir Solito –named one of the best books of the year in 2022 by The New York Times Book Review, NPR, and The Washington Post.

It took courage for Javier to travel the 3,000 miles from El Salvador to the U.S. on his own as a child. But, as a young teen five years later, it took a different kind of bravery for Javier to make the five-mile trek from San Rafael’s Canal district, where he lived with his parents, to a high school located in one of the wealthiest zip codes in the U.S. Then fourteen years old, Javier overcame his well-grounded fears of being different from his classmates to enroll as a 9th grader at Branson in 2004. “Looking back, it was the big break of my life,” he said.

Javier’s journey to the U.S. and to Branson was propelled by his parents, who valued education and had both been valedictorians at their school in El Salvador. That country’s civil war forced his father, and then his mother, to flee for safety to the U.S., leaving their only child behind with his grandparents. They hired a coyote, or human smuggler, to guide their son Javier across three national borders, by foot, truck, and boat.

But after that smuggler soon disappeared, Javier relied on strangers to help him make the perilous journey. He and his fellow migrants spent weeks in single, crowded motel rooms, waiting to trek across the

Sonoran Desert with little food or water. They had terrifying run-ins with corrupt border guards demanding payments. La Migra, he wrote from his perspective as a child, “has helicopters. They have trucks. They have binoculars that can see in the dark. I want our own helicopter to fight against La Migra. To shoot those bad gringos making us scared.”

After being caught crossing the U.S.-Mexico border, he and his small group were rounded up and crammed into a narrow space the size of a trailer with black metal bars: “We’re locked in. If we want freezing water, we drink from the metal sink on top of the metal toilet seat that reeks of piss.” He spent a sleepless night in the crowded cell and then was released, writing that “I’m outside our stinky room, that trailer, the cage.”

In June of 1999, after receiving a call that he’d finally crossed the border into the U.S., his parents flew to Tucson to pick him up at a two-story apartment building. He’d been separated from his mother for more than four years and from his father for eight. He was undernourished, smelly, and in shock. “I remember the three knocks, my heart beating so fast as the door opened, and running into Mom’s arms,” Javier wrote of his reunion with his family.

His parents took him to their apartment in San Rafael and instructed him to tell anyone who asked that he’d been born at Marin General Hospital, not in El Salvador, fearing deportation if his undocumented status became known. To help him meet other kids and keep him busy before school began, they enrolled him in a summer sports camp at nearby Pickleweed Park. Javier’s talents on the field became apparent, and his father Jose signed him up for the Canal’s U-10 team.

A few months later, in November of 1999, Javier and his parents drove the five miles from the Canal Street area to make their way up Fernhill Avenue, passing gated mansions and lush landscaping that was a world away from their two-bedroom apartment, which they shared with another family along with two other men. It was the first time he or his parents had been to Ross, and they got lost trying to find the campus. “The game had to start later because a lot of us couldn’t find the field,” Javier recalled.

Javier’s team was made up entirely of Latino kids. The team they were playing, the U-12 Central Marin Bulldogs, practiced on the Branson field and was almost entirely white. “I took it as ‘the United States against immigrants,’” Javier said. Already a gifted athlete, he’d discovered he could cope with his feelings of anger and displacement

through physical activity. “On the soccer field you can do anything,” he said, recalling how much he liked to tackle his opponents. His team from the Canal lost by one goal. Later in the season, they played a rematch against the Bulldogs and lost again.

But Coach Tom Ryan, who was Branson’s Athletic Director and coach of the Bulldogs, took notice of the aggressive defender. The following year, Javier had progressed to the Central Marin U-12 class 3 team that again scrimmaged against the Bulldogs. This time, they won. Again, the defender caught his eye: “What I remember vividly about Jav was his competitive drive,” the coach recalled. He recruited four kids from that class 3 team to join the Bulldogs, including Javier.

He excelled on the soccer field and in the classroom. After work, his mother would drill him on English vocabulary with flashcards. His dad had introduced him as a fifth grader to Gabriel García Márquez’s novel, Chronicle of a Death Foretold, in both Spanish and English. Within months of starting school, Javier had jumped from a bilingual class to a fully English-speaking classroom. After hearing his father’s description of Javier’s academic talents, the Bulldogs coach encouraged the family to consider applying to Branson.

Javier had no interest in going. His friends were all headed to San Rafael High, where he believed he would make the varsity soccer team straight away. He didn’t want to take the SSAT. “My mom had to drag me to take a test.” His acceptance letter finally arrived in the mail. His mother opened the envelope and joyfully shared the news of an offer of a full scholarship to attend Branson with her son. Javier’s reaction was different: he begged her not to go to a school where he feared he would be the only person with brown skin.

“I forced him to go,” recalls Patricia. “He cried, he begged me, he said, ‘Mom, please, I don’t want to go there.’” But she struck a bargain with her angry adolescent: try it for three months, and if he still wasn’t happy there, she’d let him transfer to San Rafael High School and rejoin his friends.

Javier’s dad, a landscaper, also urged him to give Branson a try, reminding him of what his own mother had always told him. Sitting

together in the cab of their black Nissan Frontier truck after dark, Jose said: “If we are lucky, we get one chance that’s going to change our lives. We are very fortunate if we get one – and you never get two . . . Mi hijo, this is your opportunity. I know you don’t want to, but this is it. Take advantage of it.”

Stepping onto the Branson campus those first few weeks as an undocumented freshman in 2004 took grit. He soon realized that it wasn’t only his journey but also that of his parents. He recalled his mother’s discomfort at mingling with the affluent mothers she’d only interacted with as a nanny. “I didn’t fit in there,” recalled Patricia. His more-confident Dad, when he was in town, would park his truck – laden with soil, plants, and gardening equipment – next to the BMWs and Audis of his classmates’ parents. It was Jose, who spoke better English, who ended up attending most of Javier’s parent meetings.

By his freshman year, Javier’s father was spending more time in Atlanta, and his mother was largely raising him alone. His parents were divorcing. Javier – who by then was short-statured but muscular – embraced his Latino identity as a Branson student. He dressed for school in extra-large shirts, a gold chain around his neck, with baggy pants. He described himself as dressing “like a Cholo, like a gangster-wannabe.” But because he started on the varsity soccer team as a freshman, he gained status among his peers as an athlete.

Even so, Javier was living a life outside of school that very few of his teachers or fellow students could see or imagine. His mother was working three jobs his freshman year. Her and Javier’s day would start at 5:00 a.m. when they drove from their apartment to stop at the McDonald’s as soon as it opened to eat and then head to a landscaping client in San Anselmo, within walking distance of the Branson campus. The mother and son would start the landscaping work together at dawn, and then Patricia would depart for her next job, leaving Javier to finish up the yard work before school started.

Javier would race down the hill and change his clothes in the gym (“so I wouldn’t smell like yard work”) but would often be five or even thirty minutes late to his first class. His math teacher in first period would give him a hard time for being late but never ask him why. Once, the tired freshman angrily flipped over a piece of furniture in response to being reprimanded. Several of Javier’s teachers and his advisor sat him down with his mother, warning that they didn’t want to kick him out. The intervention worked: Javier, who had been sometimes disruptive in middle school and hid his intelligence, quickly realized that this would not work at Branson. He settled down. It also helped that his freshman history teacher had predicted to the class that Javier would end up at Harvard – a school he’d never heard of at the time.

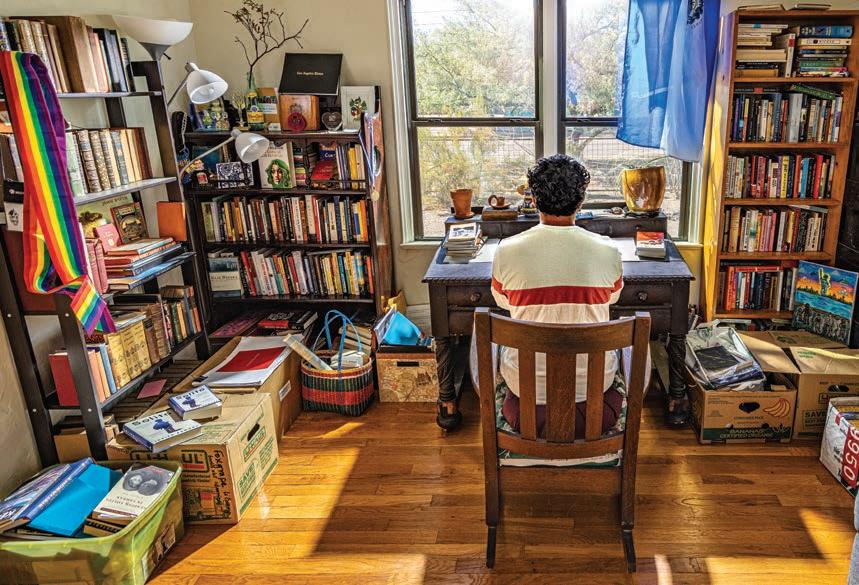

He had closely guarded the secret of his migration to the U.S., but his poetry allowed Javier to express his feelings.

It wasn’t until the end of his freshman year that he started feeling more comfortable socially at the school, in part because of his soccer teammates and his girlfriend, fellow freshman Finlay Pilcher, who he dated throughout his time at Branson. With that relationship he’d “found a really trustworthy white person that I could call my girlfriend who could support me in any room that I entered.”

Finlay’s mother was Rebecca Foust, a Marin poet who was the first-generation member of her family to attend college. She came to Branson to teach a poetry seminar on the Chilean poet Pablo Neruda the last semester of his junior year. After class, he asked if he could share some of the poems he’d written with her, including one titled Mi Tierra, about his homeland of El Salvador. Becky praised it and asked if he’d like to keep working on it with her. They began meeting to work on his poems: “I immediately knew they were different. They were unpolished, but they were extraordinary.”

He had closely guarded the secret of his migration to the U.S., but his poetry allowed Javier to express his feelings. Becky started to piece together his story through his writing. He worked diligently and with great focus on his poems. And he also began engaging more deeply with literature at the urging of such teachers as Malik Ali and Kate Moore. His teachers at Branson “taught me that I had potential and that I should tap into that potential,” Javier said.

But it was Rebecca who “made sure that I made it to college,” Javier recalled – hiring a college counselor for him and helping to raise tuition funds from Branson parents. His first poetry chapbook, published in his twenties, Nueve Años Inmigrantes/Nine Immigrant Years, was dedicated in part to Becky and her family. It was followed by a second book of poetry, Unaccompanied, published by Copper Canyon Press in 2017.

True to his freshman history teacher’s prediction, after graduating from U.C. Berkeley as an undergraduate, Javier earned his way to Harvard on a Radcliffe fellowship, as well as to Stanford. He co-founded Undocupoets, a group dedicated to advocating for the rights of non-citizen writers. He also recently played

a key role in convincing the administrators of the Pulitzer Prize in Literature to expand the eligibility for awards to noncitizens after writing an impassioned Op-Ed in The Los Angeles Times. In it, he argued that “your immigration status, just like your sexuality, gender, race and disability states, should not limit or define you.” He also helped craft a public petition that gained the signatures of 800 writers.

His memoir, Solito, was published to stellar reviews and quickly became a New York Times bestseller. His openness, tenderness, and vulnerability have won him many friends and champions in the literary world. “I just fell in love with the guy and his story,” recalls the Marin-based writer Isabel Allende, another displaced person who migrated from Chile to the U.S. many decades ago.

As much as Javier appreciates his years at Branson, he credits his family for getting him there and putting him on the path to becoming a writer. It was writing letters to his parents in San Rafael while he was still living in El Salvador, starting at the age of four, that helped him learn how to, as he puts it, “emote” on the page.

As his father predicted, Javier’s opportunity to attend Branson was the chance that would change his son’s life. He is now working on a new writing project that will examine the period from when he arrived in the U.S. as a nine-year-old to his journey through Branson. He’s no longer undocumented: he won an “Einstein” visa and is now a U.S. legal resident. He volunteers for organizations such as the Florence Immigrant & Refugee Rights Project in Phoenix and Salvavision in Tucson, AZ. He’s married to a fellow writer, Jo Blair Cipriano, and the couple lives in Tucson.

Javier’s book tour has taken him across the country, and he’s often been asked, “Do you believe in the American Dream and, if so, has it been worth it?”

His answer, reflecting on the decades of painful examination and therapy it took to excavate the trauma of his journey as a nineyear-old and transform it into Solito: “It wasn’t [a dream] until now.”

By Jeff Symonds P’22

By Jeff Symonds P’22

When we chose courage as one of Branson’s core values, I’ll admit that I was a little trepidacious. Courage is one of those terms that comes pre-laden with images and expectations. It conjures heroes on the backs of dragons, elven warriors facing a charging horde of goblins. We think of presidents gazing solemnly out of the curtains of the Oval Office, or a solitary figure standing toe-to-toe with a tank. It’s a big word for big actions.

To be sure, there are plenty of examples of Branson courageousness worthy of particular celebration every year – from athletic triumphs to extraordinary feats of scholarship to community engagement and activism to facing and overcoming moments of acute suffering. But if courage were to be a core value, something that we could see daily in our experience, then it couldn’t only refer to those kinds of overtly heroic moments. We have plenty of days without those opportunities – days defined by what T. S. Eliot would call the “many, tight, and small concerns.”

Courage, in fact, is a practice at Branson so habitual as to be occasionally invisible. We are surrounded by it here, and I am inspired to try and exhibit it every day. Here’s what courage at Branson looks like in those daily moments that compose our best days, even (perhaps especially) those days that appear unremarkable on the surface.

Let’s start with the courageous learning that Branson requires of its students. Put yourself in a student’s shoes, and head to Gayatri Ramesh’s math class. This is not a classroom where you can disappear until you think you’ve “got” it. Inside, you’ll find your peers at the board sharing their attempts to answer the previous night’s problem set. These will be problems that you haven’t seen before – problems that ask you to stretch and use your mathematical skills in new ways. You head to the whiteboard to offer your solution to problem #8, which has asked you to put your understanding of logarithmic functions to use. You walk the class through your thinking and solution. It seemed right last night at home, but in the fresh light of morning, your approach doesn’t make conceptual sense. So, still up at the board in front of everyone, you work with your classmates to figure out where you’ve gone astray, and to find the correct solution. You’ve had to reveal your thinking before it’s fully formed, make a mistake on the board in front of all of your peers, and capture new ideas and insights to prepare you for the problems you’ll receive that night.

You’ve been authentic and vulnerable to yourself, your teacher, and your peers – and it’s not even 10 a.m.

At assembly, you’ll make an announcement about a community engagement opportunity to 500 people looking down at you from layers of seats in the outdoor amphitheater – peers, teachers, staff, plus 50 visiting parents and eighth-grade prospective students. Your voice will fill the silence as you project to the back row. You’ll reveal something that matters to you, and invite people to join you in doing it.

Then it’s off to any number of humanities classes. You may be studying constitutional history with Malik Ali and learning how to discuss our political history with mutual respect and curiosity. You could be in Hilary Schmitt‘s ethics and justice class, where you design an individual project that leads you to community action – perhaps successfully petitioning the national mountain biking association to change the start times for races to be more equitable to top flight female riders, or designing a schoolwide assembly featuring a panel discussion by local experts on educational inequities in Marin County. Or maybe you’re in my English class talking about the ways in which Toni Morrison praises and criticizes the template for black morality that Malcolm X presents in his autobiography. You’ll raise your hand and offer an idea, listen to three others, change your point of view and share your honed thinking, and help a classmate find the words they’re searching for. You lose yourself in the search for meaning, for growth, for insight.

After lunch you head to music class, where Jaimeo Brown is coaxing you to improvise on an instrument that you’ve only recently become comfortable holding, let alone playing. You’re no longer just following notes dutifully on a page – you’re creating new music on the fly. There are two- and three-second passages where you shock yourself with your tone and fluidity, and just as many when you play yourself into a corner and lose the thread. And there’s no time to think because the phrase is coming around and restarting and it’s time to take a breath and go for it again. When it’s someone else’s turn, you notice that you’re sweating a little and your heart is beating faster.

To close out the day, maybe you’ll discuss ideas and great literature in a language you’re still learning, or work with four friends to try and build a model that reveals the presence of gravity as a force. Then you can top it off with a run around Phoenix Lake for cross country practice where you keep up with the older runners for the first time.

And remember– this is an ordinary day: no playoff game, no performance, no special assembly. It’s the kind of day that, when you get home, you’ll describe to your parents as “fine.”

A great education changes you; change is real and therefore scary. On an average day, you might come home from Branson a slightly different version of yourself. The courage it took to be open to it all, to squeeze as much from it as you can, is so much a part of your sense of self that it’s become second nature, ingrained. That’s a core value.

And while the school is unthinkable without its population of these remarkable students, they would never reach the same heights without the courageous teachers that meet them at the intersection of their ambition and ability. Courageous teaching is also sometimes

equally subtle and not immediately identifiable, but it’s one of the bedrock characteristics of our approach.

Branson teachers innovate and iterate already successful lessons looking for more. Can I center the student learning a little more? Is there a better question I can ask? Sometimes that thinking results in a new project or assessment that the teacher designs. Just as often, it’s coming into class and letting go: letting the students tell you where to start with their questions or enthusiasm. Some of the greatest classes that we teach are mysteries to us until they’re over, because we genuinely don’t know where they’re going until students take us there. And being able to guide that pathless journey to insight –whether it’s Gayatri asking just the right question when students are hashing out a problem at the board, or Malik offering the counterpoint in a debate so students can see all sides of a principle, or Hilary’s inquiry about your project that helps you see the next three steps, or Jaimeo’s shouted encouragement over your improvisation – that’s expert teaching, and it demands the courage to let go and let the potential learning be the focus.

I would argue that this courageous synergy between teachers and students is the greatest daily manifestation of courage on Branson’s campus. It’s that magical moment when a teacher puts something –an idea, a text, a formula – in the middle of the table and rotates it with just the right questions at just the right time. Branson teachers draw from their expertise not just in the subject, but in their ability to

We all strive to come to school every day open to possibility, to epiphany; this is our daily act of perpetual, essential courage.

bring that subject to life. Curious, students meet their teachers with the skill and willingness to help interrogate that material and find meaning in it.

While it’s true that courage at Branson rarely requires swordplay or magic amulets, it always requires the vulnerability necessary for the moments of transformative growth that are at the heart of our program at its best. It’s the perpetual search for those moments that has inspired me into my fourth decade of going into one of our classrooms hoping to find the meaning of it all, seeing eager faces in front of me who are already starting to talk about the text, leaving my notes in my bag, and asking, “So, where do you want to start?”

By Sarah Muench

By Sarah Muench

Anne Bennett ’78 was driving home from work one evening, when she pulled over to the side of the road and turned up the radio. Her team was reporting on Jewel Taylor’s plea for forgiveness for the war crimes her husband, former Liberian president Charles Taylor, committed in Sierra Leone.

As the country representative for Fondation Hirondelle, a nonprofit that advances the right to information through journalism, Bennett had to pause and take it in: Taylor’s groundbreaking apology would be heard across the nation.

Bennett, who led the teams that created Sierra Leone’s first independent, national news service, worked to ensure the post-conflict country had access to news and information to make informed decisions and contribute to a peaceful future.

“It’s not about you,” Bennett said. “But you can’t help but be inspired by it to live your life in a way so that you do have agency and the courage to make decisions and even make the wrong decisions and deal with it.”

From her days at Branson to living in Africa, Bennett has fought for what she believes in because “it was the right thing to do,” she said.

• • •

Later in her career, she said, courage came from her staff and the stories of people on whom they reported.

Bennett’s teams in Africa and Southeast Asia responsible for implementing avenues of information access such as radio stations and public-service media networks provided an outlet to tackle some of the countries’ most difficult issues, such as early marriage, intimate partner violence, and violent extremism. Some issues, like female genital mutilation (FGM), were too taboo to discuss on the radio. But many of the women with whom Bennett worked, including radio reporters, had been harmed by FGM. When they were younger, no one would talk about it.

The radio provided an avenue to discuss it, but how could they approach such a forbidden topic?

“Journalists realized there was a real danger or fear of covering FGM, but if it was going to change, there has to be a dialogue,” said Bennett, a mother of two daughters.

The reporters interviewed public health experts and religious leaders to dispel myths and opened a dialogue on the airwaves so listeners could relate, gain knowledge, and begin to work through trauma.

“They could have said it was too dangerous. But when they started covering it, they heard someone call in and got such a positive reaction,” Bennett said. “Women who had traumatic experiences and could talk about it and

acknowledge how harmful it is for themselves; they were doing the right thing in covering it.”

• • •

Bennett always was clear about wanting to do something purposeful in life, according to Kim Belshe ‘78, Bennett’s Branson classmate, friend and previous Secretary of Health and Human Services for former Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger.

“We are driven by wanting to make a contribution, and she executed it on a scale of international development,” Belshe said. “She chose to pursue that life of purpose at a scale that is really, really impressive, and I’m terrifically proud of her as a friend and classmate.”

Taking a job on the ground and moving to a new, post-conflict country involves stepping into the unknown and having confidence in yourself, Bennett said.

“Sometimes I feel you have to run toward your fear you will see it’s not so bad, going toward the scary thing and having confidence,” Bennett said. “It’s the small courage, not with the capital ‘C’.”

But Edward Kargbo, who worked with Bennett at Cotton Tree News (CTN) in Sierra Leone and in Sudan at Radio Miraya, said it still took “an incredible amount of courage to start up a project of CTN’s nature and scale in a country that was barely coming out of a long civil war, a broken bureaucracy and systems, and many other difficulties. Anne was always very calm.”

Bennett used her courage, values, and experience when she stepped into her current work with think-do tank DCAF - Geneva Centre for Security Sector Governance, which builds and strengthens accountability at state and community levels. As the head of the Sub-Saharan Africa Division, Bennett is responsible for initiatives supporting democratic governance, rule of law, and respect for human rights.

“This gave me a chance to really be involved in many more aspects of what makes up a just society and to see if I could support work that could have an impact on a larger scale,” Bennett said.

Belshe said Bennett’s story is about experiential learning.

“It’s through experience that you learn so much about yourself,” Belshe said. “I have always been impressed by Anne’s commitment and passion to make a difference and her ability to face uncertainty undaunted. Courage is about facing uncertainty undaunted.”

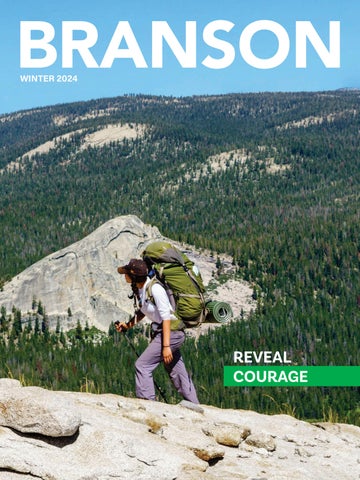

Thirteen backpackers trudge steadily up a trail beneath weathergrizzled conifers and flanked by walls of steeply sloping granite. As the sun creeps higher in the sky, the student leaders signal the group to stop – a water break, a few bites of an energy bar, a quick redistribution of gear to lighten someone’s pack – and then they continue their unrelenting ascent. As they walk, the dry air smells of pine and juniper, and a slight breeze offers welcome relief from the mid-August heat. It’s already been a long day’s journey, and it’s only 11 a.m.

Overhead a scrub jay squawks and, as if on cue, the trees open up to reveal a wide-open vista of rock, low bushes, and sky. Below is revealed the sparkling blue reservoir where their hike started earlier that morning – and it’s a long way down. The sweaty hikers drop their heavy packs, feeling suddenly lighter as they pause to admire the view. High-fives, excited chatter...they are on top of the world.

This is how sophomore year at Branson begins. Since 2021, Branson has partnered with Outward Bound California on 5-day backpacking trips in the High Sierras that are now the required orientation for all 10th graders. It’s a program “designed to challenge students with transformative experiences that lead to personal growth and a more unified and inclusive community.”

For the majority of our students, this experience is all new. Some have hiked, but few have lugged a 40-lb. backpack or cooked dinner for 12 on a portable stove or slept outside with only a tarp between them and the stars (or the rain) above. Untethered from electronic devices, immersed together in the tranquility and unpredictability of nature, it’s a different world.

What is the impact of this journey? Students shared their take-aways:

“I learned that I can make it to the top of the peak if I persist.”

“I saw how important it is to meet new people I might not normally interact with. I learned that I should get to know more people in my community and continue to branch out even if I feel satisfied with the friends I have.”

“ This taught me to persevere through challenges much better, and it’s changed how I approach difficult things in life.”

Peter Zdrojewski, Branson’s Director of Global & Outdoor Education, reflects: “Our goal is not that students fall in love with the back country and want to do this for the rest of their lives. But if we can create a space where kids are pushed out of their comfort zones in a variety of ways that help them find their true potential – and where they’re broadening their idea of community – then I think we have something of immense value.”

“Every student showed courage in different ways. A lot of them weren’t too stoked to be on the trip in the first place – and four days later they were in lightning and pouring rain, with everyone carrying extra gear to help a fellow student push through. Watching the whole group come together in a very challenging situation – while still having fun – epitomized why we are doing this.”

Doubt shadows the corners of the student’s eyes as he hands over the headphones. “I don’t know. See what you think, I guess.” The 15-year-old ruffles a hand through dirty-blonde bangs that hang down over his smooth, creamy forehead, nearly masking his eyes. An unconscious habit.

The young man in the seat next to him mid-twenties and slender with a coffee complexion, soft features, and a wispy goatee dons the headphones and listens to the music the student has created, watchful eyes focused straight ahead, head bobbing gently to the beat,

fully absorbed. Then he pulls off the headphones and smiles. “Man, that’s dope! Those transitions, you aced it.” The student beams like he’s just won a Grammy. Whatever guardrails he had up before are now flat on the pavement.

As the two range from there deep into an animated conversation about chromatic scales, root notes, and how to resolve a melody, it would be easy to miss the reality underlying this interaction: an arduous journey spanning a decade or more, one that at times seemed not just improbable, but impossible.

Riding north on Highway 101 on a fall evening, when you crest the ridge just past the Tiburon exit you encounter a panorama of light, from the Corte Madera flatlands on the left ahead to Greenbrae, over to Larkspur Landing and beyond. But the brightest lights decorating this vista emanate from a source that locals often forget is even there: San Quentin State Prison.

Occupying an isolated peninsula on the far reaches of European settlement when it opened in 1854, today San Quentin stands at the foot of the Richmond-San Rafael Bridge. Eighty thousand cars a day pass within a quarter mile of the prison’s main gate without most of their occupants ever sparing a thought for the lives held captive inside its walls.

“I committed my crime at the age of 17. I was a junior in high school.”

Eric Abercrombie is 28 now, four years free after spending seven in one of the nation’s most notorious prisons for an offense committed when he was too young to vote, drink or register for the draft. Slender and wiry-strong, his expressive eyes offer a window into the mind of an artist attuned to every vibration in the room and eager to engage.

Eric, known to friends by his musical moniker Maserati-E, nods to his friend Antwan in the next chair. “He committed his crime at 18, right after high school.” Antwan Williams, a.k.a. Banks, is six years older, tall with chiseled features, close-cropped hair and beard, deep brown eyes and a personal magnetism that seems effortless and organic. E continues: “So we quite literally are examples of the school-to-prison pipeline.”

Both men were born into circumstances that put them in the at-risk category before they could walk, Eric in Oakland, Antwan in South Central Los Angeles. Each experienced a fractured family life scarred by poverty and absent parents mixed up with drugs.

Both gravitated toward music and the arts, but each made a bad decision at a critical moment in their young lives.

Owning those decisions was a first step toward healing and growing. In prison, Banks and E met through mutual friends and became “cellies” cellmates, sharing a fourby-ten-foot space for hours every day. They connected initially over music and art, but the friendship quickly deepened based on their shared desire to become not just better people, but catalysts for positive change.

“There’s always been a level of love and respect and compassion,” says Banks. “When we didn’t have anything, we had each other and we had to find a way to grow out of that nothingness. And we was pouring into each other.”

E replies in kind, calling Banks “like a big brother to me. Somebody that I look up to, that I seek when I need advice. A mentor. A role model.”

Both are talented and mostly self-taught musicians and audio engineers, skills that led another friend to ask Banks to “help out with the music” for a program called Shakespeare in San Quentin. Volunteers from Marin Shakespeare would come in to work with the incarcerated men every week as they learned and performed Shakespeare plays. From handling music, Banks soon found himself playing roles.

In time, Banks drafted his cellie into the group. The experience was eye-opening for E. “I had never imagined being able to put myself in somebody else’s shoes.”

And then a new face appeared in the audience.

“I had never been inside a prison,” says Branson’s Head of School Chris Mazzola.

Energetic and unpretentious to her core, the blonde Mazzola comes across like that mom the neighborhood kids all flocked to growing up,

“We talked about how we made the choices that we made,” says E. “And one of the solutions that came up was, we need to start going to high schools, where people are stepping into these vital years of quite literally becoming who they will be.”

because she gave her whole heart and attention to every one.

In 2017, a Branson parent invited Mazzola to attend a theater performance with her inside San Quentin. The experience was lifealtering. “It was one of those moments where something shifts. How have I missed this?

I’m a 50-year-old woman leading a life of privilege, and I haven’t been paying attention to this huge social justice issue. I was a little ashamed of myself, but I also thought, I can’t let the same thing happen to these students. Branson is six miles from San Quentin!”

Mazzola began volunteering with the Shakespeare program, entering the prison weekly to work with the incarcerated men. Asked what drew her into this unfamiliar environment, Mazzola gives an answer that American culture has conditioned us to find surprising, given the identities of all involved.

“When I went in there, the men made me feel safe.”

She continues. “I would go in there, away from all the pressures of my job, and it was like a sanctuary. It sounds so strange. But they were kind, and they were authentic, and they were trying so hard to be good people, to make themselves better.”

From vulnerability, Mazzola flashes to the steel that is also part of her character: “People shouldn’t be defined for their whole lives by their worst mistake.”

In the Shakespeare group, she spent hours with Banks and E each week. “My trust in them as human beings just grew and grew.”

In their own conversations, Banks and E dug deep into the personal goals they were defining for the future. “We talked about how we made the choices that we made,” says E. “And one of the solutions that came up was, we need to start going to high schools, where people are stepping into these vital years of quite literally becoming who they will be.”

Once they had shared this idea with Mazzola, she began reaching out to colleagues at peer schools, laying the groundwork for what the men were calling the Shifting Perspectives tour.

In 2019, after seven years in San Quentin, Eric “Maserati-E” Abercrombie walked out the main gate to breathe the first air of his adult life as a free man. His friend Antwan “Banks” Williams followed soon after.

On the morning of November 12, 2019, the buzz on the Branson campus had a different feel from the normal background hum of teenaged chatter and energy. An all-school assembly had been announced, with special guests, but no one knew who they were.

Students entered the gym to find a scene that was both disorienting and thrilling. On a campus that has grown more diverse over time, but still carries all the rather staid hallmarks of an elite college prep school, two young African-American men wearing Branson hoodies were rapping to a thunderous beat, throwing down hard, dropping knowledge with every line of their penetrating lyrics.

Once the students had settled into their seats, the music ended and the real talk began. Banks and E shared their stories, their truths, and their songs, using every tool they had to earn the students’ attention, and then using that leverage to power home their ultimate message: Every person has value. You matter. And the choices you make can change not just your future, but the world.

“When I realized that I can play a role in how people’s lives pan out,” says Banks, “that came with a super amount of responsibility, and also vulnerability. We stand on who we are and all of our mistakes and being accountable for that. We talk about the roads we took, but then we say, you don’t have to do that. Just like your fingerprints and your thumbprints, you are divinely created and worthy of being seen, loved, and validated and upheld.”

Arts Department Chair Eric Oldmixon, a 20-year veteran at Branson, was among the faculty present that day. “It was such a moving and authentic presentation. They’re both super talented and the way they engaged the audience was so thoughtful.”

When the assembly was over, students lined up to talk with E and Banks, shake their

hands, hug them. Some cried. No one in the room was unaffected.

Banks describes that first assembly as “a visceral experience, because we’d been dreaming about it for so long. Everybody dreams about that big game, and then when you actually get there and perform, it’s like, ‘Oh, I wasn’t just prepped for this I was made for this. This is where I am supposed to be, with the right people at the right time in the right space. This is what destiny feels like.”

Every single performance of the Shifting Perspectives tour ended with a standing ovation.

And then the pandemic arrived, the world shut down, and everything stopped.

• • •

Classes moved online. Everyone, everywhere, went into survival mode. And Mazzola plotted Branson’s next move.

“The E. E. Ford Foundation provides grants to independent schools,” she explains. “Speaking with students in the Ethics & Justice class, we said, let’s write a grant to see if we can find a way not only to teach our students about social justice, but also to help these men as they reorient to society, by bringing them to campus and having them work with our students. The students were fired up; they wrote the grant themselves, and made it happen.”

The grant was approved, but the pandemic wasn’t over and it was another frustrating year of complications before vision could finally become reality.

Asked what made her persist, Mazzola is resolute. “It goes back to our mission and values. Our students are going to leave here and enter a world that becomes more complicated by the day, and we’ve created a society that’s so stratified that you can grow to adulthood and never be around anyone who’s different from you.

“They are truly masters of their crafts, and the way they inspire the students, inspires me,” says Brown. “We often learn the most about life through hardships and challenges. Some of the greatest light comes from some of the darkest places.”

It’s our mission to prepare these students to solve the problems of their time and I believe that a very specialized, privileged education like we provide at Branson comes with a moral imperative to do more than just serve yourself.”

• • •

Music teacher Jaimeo Brown’s courses in music theory, composition, and performance are enhanced by the regular presence of guest artists E and Banks. “With art being a kind of a language, it was really very natural for us, forming a relationship and being able to create an atmosphere for the students to be intrigued by things that we’re intrigued by music production, visual arts, all these beautiful things that they have brought in. We have amazing conversations all the time.”

Oldmixon describes a similar dynamic. “I think it’s been the best professional development I’ve had in years, just being able to exchange ideas and explore different points of view with two incredible human beings, talented artists, who’ve had a very different view of life than I have.”

“They are truly masters of their crafts, and the way they inspire the students, inspires me,” says Brown. “We often learn the most about life through hardships and challenges. Some of the greatest light comes from some of the darkest places.”

• • •

For all the goodwill surrounding it, the men’s transition from prison to the classroom was never going to be a simple process.

“I definitely was fearful,” says E, “of not being received, or understood, or making the impact that we wanted to make. But we still came, knowing that we’re going to look different, be different. I think proximity creates openness. Without it, all we have to rely on is our imagination, and a lot of mythological stuff.”

Reflecting back on their experiences with Shakespeare in San Quentin, Banks considers how it laid the groundwork for their roles at Branson today.

With Shakespeare in San Quentin, he says, “We were working on creating a brave space not necessarily a safe space, but a brave space where we are all stepping out of our comfort zone.” Working with students at Branson, it’s a similar concept applied

in a different context. “I want to help them navigate this idea of a brave space. Take this curriculum and apply it to what you want to do in the world. But at the same time, how can you use this to live out the best aspects of your humanity and your dignity? What’s so powerful about my role here is that I could figure out how to do both.”

“I give the Board of Trustees great credit for allowing me to do this,” says Mazzola. “For saying, ‘This is the kind of thing we want our students to be learning about.’ That’s huge. We didn’t do this because it was going to be great for admissions or marketing. We didn’t do it for any reason other than it was a good thing to do. Not all boards would do that. It’s the courage to do the right thing when the right thing is hard.”

Over lunch, E is catching Banks up on that morning’s Digital Music class. He lights up at the memory. “Oh, they had some fire pieces today! I’m like, this is full-fledged production, this is dope! And then ” the boy with his bangs nearly covering his eyes—“he

surprised me, because he’s usually in the back, kind of quiet, but working the keys. And he got it I had very minimal advice and critiques for him.”

The conversation turns to the journey that has led to the roles the men now inhabit at Branson. “I feel like I’m a stakeholder in this community,” says Banks, “because of how I have been received and the position that I’ve been entrusted with. Whether it’s the students talking about their work or the staff that have embraced me because of that, I will defend and uphold the sanctity of this space like I will my own home and my own community.”

E’s vision of the future is equally hopeful. “Privilege has a lot of negative connotations, I believe, because a lot of the time people in privilege don’t use it to further empower others outside of their own community. And I strongly feel the students here will use their privilege and their power in those ways. If we inspire a person who inspires the world, then we made our contribution to that as well. That’s very exciting and encouraging.”

Guy Raz sat down with Maura Vaughn –Branson’s theater director since 1996 and parent of two Branson alumnae – to reflect on her career in theater, courageous risktaking, and “pie-eyed optimism.”

Q: You’ve been teaching theater at Branson for a long time. I read that your classroom mantra is, “in acting, one must be willing to leave their dignity at the door and take chances.” To me, that speaks to the very core of the idea of cultivating courage, right?

A: Yes, and it also builds a habit. There are teachers who feel that the theater is a very safe space in every sense of the word – not just keeping one another safe, but also protecting their actors from unexpected interruptions like people coming in to change a light bulb. I’ve never been that way. There’s that balance of knowing the real world still exists and that someone could barge in in the middle of a challenging scene and say, “Hey, this light doesn’t work.” And that’s okay. I just say to the actors, “Take a deep breath and adjust. And if you can’t, stop and go back.” But because they’re in control, it’s okay. I think that’s why I start with improv.

Q: Right, your acting program is improvbased for the first two years. Why is that?

A: I want to level the playing field and for us all to have the same language. It doesn’t matter how brilliant you are; if you’ve left your partner in the dust, we can’t see the conversation between the two of you. We come to the theater to see that struggle. You have to be able to connect and work off of and trust each other. And I think the best way to find that is to have a common understanding of how you make each other look good and give one another space. And

know that no matter what happens, it’s going to be brilliant. You want to start there, right?

Q: I know that you started in New York as a stage actor. Can you paint a picture?

A: I was one of those lucky people. Within six months out of college, I had all three union cards. And I thought, well, here we go! I had a show off Broadway. There were periods of time in my career where that’s how it went. And then there were other periods where I would literally say to people, “Yeah, no matter what I do, I can’t even get arrested.”

Q: Tell us about Maura the actor?

A: My strength as an actor is that I empathize with the plight of a character easily and absorb their underbelly. But I also have good comic timing. And so I’m deep, but I’m funny. Every role allows you to expand, to open up different parts of your psyche.

Q: Actors begin to develop the ability to withstand the pressure of being on stage. But I think even great actors – I’ve interviewed Audra McDonald and Nathan Lane and others – still get nervous, or at least look to get out of their comfort zones. Making the transition from the stage to the classroom is a different kind of acting and a different kind of skill. When you started as an educator, was that scary for you?

A: No, I never get nervous. But at first I did think, “I don’t know anything about theater education.” And then I thought, “That’s ridiculous: I was in New York when all the great acting teachers were still alive. I studied all kinds of techniques with them.” So, I became fascinated about how one teaches acting, especially to young people. And so, when Branson said, “We need

an acting teacher; are you interested in throwing your hat in the ring?” – this is one of the advantages of being an actor – you always say yes.

Q: What’s the relationship between courage and failure in the theater?

A: We were doing The Grapes of Wrath and a student said, ”Do you ever look up and think, this might not work?” And I smiled and said, “Okay, what would that look like? Would somebody fall off the stage?” And they said, “Well, what if they do a bad job?” I told them the point isn’t whether they do a brilliant job or not. The point is that they have a journey – not just the character’s journey, but a personal journey – and they feel that they have grown and challenged themselves. So as long as nobody backs off and says, “I can’t do this” or as long as no student has ever quit a show and said, “Oh wow, this is just too hard or too scary or you didn’t support me enough,” then it’s all brilliant.

Q: I know one of the mandates you’ve been given as an educator at Branson is to “help grow good humans.” How do you think about your role in that charge?

A: One of the ways you grow good humans is you have absolute faith in them. Absolute, right? Even when a kid makes a horrendous mistake, right? I’m not here to tell them that they are good, bad, or indifferent. I adore them all. I’m just here because this is what I love and my joy is here with these students. And [by listening to them and not judging] they are going to show me the map [when they need help]. They’re going to show me the road. And so that’s how I’m trying to develop good humans because, of course, I’m doing it with them.

Q: What is something that you can recall doing recently that was scary, or that required you to harness all of your courage?

A: Sometimes, especially in my Class Dean role, you know a student is not ready to make a better choice.

You don’t have proof, you can’t intervene, but you can feel it. And it’s a real balance about how much you push and how much you just have to say, “I am here” and let it happen. And there are moments that I go home and say, “Well it would be really nice if this did not end up blowing up in this person’s face.” That moment before you have to clean up the mess is always the hardest, right? When you can see the other car coming at you, and you say, “Oh, this is not going to be good.”

Those are the hardest moments, especially as an adult, to say, “this is not mine to control.”

Q: Back to your acting career for a moment –what about the part that got away?

A: I came very close once to playing Blanche DuBois, but I did not get cast. And it was one of the few times I haven’t gotten cast that I thought, “Oh, thank God.” Because how could I live in Blanche Dubois’ head with the same depth as I could in other characters?

Q: Which historical figures would you want to join you at the dinner table?

A: I would be really interested in talking to Queen Elizabeth I, not as a queen, but as a child, in that moment where her mother’s beheaded and she has this father. But she seems to have the emotional intelligence to have a real landscape of where she’s going.

I feel the same way about Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., that there was a part of him that understood the moment in a way the rest of us really didn’t, and he could easily have said to us, “I’m not getting to old age.” But what was it that he saw? What was that pattern that he saw that the rest of us completely missed?

Q: Who is a living person that you most admire?

A: Meryl Streep.

Q: Which talent would you most like to have if you could have another talent?

A: I want so many of them. I want to learn another language in a way that I can think in it. I want to play the piano. I want to skydive at some point. I’m that song: I want somebody to walk out as I walk in.

Q: What is your greatest fear?

A: That’s a really hard one right now, because as my mother used to say, “Maury, you’re a pie-eyed optimist.” And I have this horrible fear right now that my mother might be right, that my optimism might have been a little on the pie-eyed side about people and the world and where we’re going. So, that one’s hard.

Q: What is your most marked characteristic?

A: How much I care.

Q: What drives you every day when you walk into your classroom?

A: One of the things that fascinates me about the art form of theater is that constant: you’re waiting for that little nugget of truth, and then you nurture that nugget. And that was addictive for me. For my students, all I want to do is help them find their own personal aesthetic, their own personal nugget of truth, and then nurture that. And it’s not just that I nurture it; I teach them to nurture it. They own it. It’s theirs.

Oliver Goldman ‘24 navigated his bike up the hazardous trail in the High Sierras with determination and with a heavy pack and rappelling gear on his back. Just a few hours earlier, a 4:00 a.m. page had summoned him and his team to an urgent search for a missing mountain biker. But this wasn’t entirely unfamiliar Oliver, then a junior at Branson, had been here before.

A volunteer with Marin Search and Rescue (SAR), he had considerable experience. SAR teams are often the first line of defense, as finding people takes an immense amount of manpower. Their work involves missing person searches, often for children or for adults with dementia, as well as evidence searches. With SAR, Oliver had engaged in over 30 searches across California, logging more than 1,000 hours in training and rescue operations. Marin SAR, renowned as one of the best in the country, is also one of a small handful of SARs among hundreds in the U.S. that includes younger members, some as young as 9th grade. But those young members get no special treatment: Oliver’s required rigorous training included a Type 1 fitness test, rope rescue, rappel and cliff rescue, medical certification, and high altitude training.

The Sierra search was long and intense, as the trail traversed a steep mountain many miles away from Downieville, the nearest town. They had been searching for most of the day when they caught a glimpse of silver in the underbrush near the trail’s edge: it was the missing man’s bike.

Oliver’s bike team which also included his Branson classmate Max Mohan ‘24 sent out word to other search and rope rescue teams, who rappelled more than 300 feet into the steep canyon. As the sun was setting, they found the man, who had not survived the fall. Oliver and his team worked methodically, using a satellite phone to call for additional resources. A Special Forces Black Hawk helicopter was dispatched from Moffett Field to navigate the canyon’s narrow walls and near total darkness to recover the body.

Following a four-hour bike ride back to Downieville and a few hours sleep, Oliver and his team held a debrief and reflected on the gravity of the previous day’s events. Despite the tragedy of the biker’s death, his family had closure and was grateful for the incredible effort that went into the search. It was then that it really hit Oliver – that the work he and his team does truly impacts people’s lives.

Oliver was elected by his peers as Youth President of Marin SAR, and was also awarded the Marin County Youth Volunteer of the Year Award. But for Oliver, it’s not about recognition. It’s about making a difference.

“Search and Rescue is not an individual pursuit; it takes a dedicated and courageous team,” says Oliver. “After becoming heavily involved in Marin SAR, I can say with confidence that I have never found a more devoted and selfless group of people.”

Helen Dewar needed a workaround. Congressional leaders had just banned reporters from standing outside the Senate doors. It was the 1980s, and Capitol Hill reporters trying to snag a quote would buttonhole lawmakers as they came and went. So Dewar ‘53, the U.S. Senate correspondent for The Washington Post, no longer stood. She ambled.

“She would just walk very slowly so the cops couldn’t tell her to move along,” recalled David Espo, a retired congressional correspondent for The Associated Press. “She had it down to a science.”

What became known on the Hill as “the Dewar walk” epitomized the determined journalist, colleagues said. Covering the Senate from 1979 to 2004, Dewar became the unofficial dean of the Capitol Hill press corps, reporting on budget battles, U.S. Supreme Court confirmations, and President Bill Clinton’s impeachment trial.

Competitors said they admired Dewar’s deep knowledge and unassuming demeanor, even as they feared her next scoop. She excelled by outworking the competition. While other reporters chatted outside closed-door meetings, she soaked up the latest Congressional Quarterly. floor debates droned on past 1 a.m., Dewar remained in the press gallery, scrutinizing every word.

What became known on the Hill as “the Dewar walk” epitomized the determined journalist, colleagues said.

“She scared the life out of me because she was so good,” said Candy Crowley, CNN’s former chief political correspondent. “Helen was always working. She was so intense.”

Dewar traced her interest in journalism to Branson, which she attended for her junior and senior years, from 1951 to 1953. As a journalist, she didn’t presume “to think I know everything about everything,” she reflected in The Branson Magazine in 1994. It was a lesson she had “learned with chilling impact” when she arrived at Branson “without knowing who Chaucer was.” In addition, because Branson teachers had “made it clear that my writing skills left a lot to be desired,” she recalled, she joined the staff of Stanford University’s newspaper when she got to college.

Early in her career, Dewar reported for a small paper in the Washington suburbs, according to her obituary. She joined The Post in 1961 to cover Northern Virginia and later Virginia politics — this at a time when many female reporters remained relegated to food, fashion, and other “women’s” news.

Dan Balz, The Post’s chief correspondent, recalls a piece of newsroom lore about Dewar and Ben Bradlee, the paper’s executive editor of Watergate fame. On a tense election night, Bradlee headed to Dewar’s desk. A key Virginia race was too close to call, and the editors needed a headline.

“Helen, how are we going to call it?” Bradlee reportedly asked, then quipped, “You’re either going to be right, or you’re going to be famous.” Bradlee would have known, Balz said, that Dewar would get it right. “She was the gold standard,” Balz said. “She knew more about those races than anyone in the newsroom.”

Eric Pianin, a former Post Capitol Hill reporter, said Dewar took that expertise to national politics when she began covering the U.S. Senate. She was “extraordinarily helpful” to new Hill colleagues,

he said, and had senators “well-trained” to return her calls. She had little patience for editors with “bone-headed suggestions” or Senate staffers who tried to spin the news to favor their bosses.

Dewar’s tough but balanced stories garnered such respect that, when she became ill, lawmakers from both sides of the aisle called to check in.

After she died of breast cancer in 2006, at age 70, Branson officials were surprised to learn of her $2.5 million bequest, the school’s largest-ever gift at that time. The scholarship fund in her name has since doubled in size and has provided financial assistance to dozens of students.

Today, Dewar’s colleagues remember her as a legend. Among her many accolades, the Washington Press Club Foundation honored her with a Lifetime Achievement Award in 2006, lauding her reporting for its “verve” and “insight.”

In 1984, she became the first woman to win the prestigious Everett McKinley Dirksen Award for Distinguished Reporting of Congress. Still, colleagues said she didn’t acknowledge being a trailblazer.

Maurine Beasley, a Post colleague from 1963 to 1973, said Dewar wasn’t vocal in The Post’s own gender battles, as female staffers agitated for equal pay and higher-profile assignments.

“She definitely knew she was discriminated against, but she didn’t wallow in it,” said Beasley, a professor emerita of journalism at the University of Maryland and author of a history of women reporters in Washington.

However, Beasley never forgot how Dewar once told her women could succeed in the news business: They just needed to be “twice as good as a man and work twice as hard.”

As a sophomore playing for Branson’s Varsity Tennis team, Tara Sridharan noticed something. “The girls on the other team, from a local public school, were competing in jeans and sweatshirts with broken racquets. I thought to myself: What is happening here? I knew I wanted to do something about it.” That summer, Tara teamed up with PlayMarin, a nonprofit dedicated to increasing access to extracurricular opportunities for Marin City youth. Together they created a summer tennis camp for players ages 7-13 at the Martin Luther King, Jr. courts in Sausalito. “My campers were reluctant at first,” said Tara. “Many had never set foot on a tennis court before. Now, almost two years later, they play on their own, and even come to my Branson matches to cheer us on.” After a successful first year, Tara was awarded a Branson Junior Fellowship and a United States Tennis Association grant, which helped the camp expand the following summer. Though she is their coach, she insists she’s the one who’s learned the most: “I learned the importance of doing something new even though it’s uncomfortable. Every day, our players picked up those racquets and tried their best. I hope to do that in whatever’s next for me in my life.” What’s next for the camp? Tara has big plans: in 2024, she hopes to add a spring clinic, and down the road, she aspires to create an official youth tennis association in Marin City.

Hayley Yoslov wasn’t sure she’d made the right choice when she joined the Branson Mountain Biking team as a sophomore. “Honestly, it was kind of terrifying at first. I was really bad at it and solidly in the back of every ride,” she said. “But I told myself, ‘you just have to stick with it for two weeks before you can think about leaving.’” Before long, she was hooked, and she quickly established herself as a fierce competitor and a mentor on the team. As a senior, brainstorming ideas for her final project in her Ethics & Social Justice class, Hayley couldn’t stop thinking about the Sea Otter Classic mountain bike race in Monterey – and her frustration at being forced to start behind and push through the field of slower male racers. Teacher Hilary Schmitt urged her to channel that frustration into action. Arguing that “the current start format greatly disadvantages riders in the female category by starting them after all riders in the male categories,” Hayley presented a data-rich proposal for change to the race commissioner. Though the initial response was tepid, she was undeterred. She created a change.org petition that ultimately garnered over 2,000 signatures, and when professional female cyclists (including Olympian Kate Courtney ‘13) rallied to support her cause, the groundswell of social media finally got the race organizers’ attention. The race rules were changed, and Hayley had her win. Today, she attends UCLA where she trains with USA Cycling National Development Team, a feeder to Team USA.

Courage takes many forms at Branson, as our students and alumni live our core values every day. Here are a few of their stories.

As a nine-year-old, Max Gutierrez was creating stop-motion videos with Legos and a GoPro he’d saved up to buy. In middle school, a digital media class (taught by Branson alum AJ Cheung ‘03) piqued his interest in camera technology and editing software. At Branson, Max continued to hone his craft by creating athletics highlight reels, documenting student events, and more – all for fun. “It was nervewracking sharing my videos. I didn’t know if others would like them,” he admits. But students loved them. His talent was unmistakable, students sought him out for new projects, and the school administration engaged him to do their official videography. His company, @MGVisuals, began as an Instagram handle, but through cold-calling, Max seized new opportunities and quickly evolved it from a side hustle into a business. Whether filming rapper 50 Cent at an Oakland club, documenting Apple’s Worldwide Developers Conference in Cupertino or traveling to the Philippines to film the Filipino American basketball team “Fil-Am Nation,” Max is usually the youngest professional in the room. “For me, storytelling is the driving factor with a combination of camera and editing effects that make my vision come true,” he shares. Now at DePaul University’s School of Cinematic Arts, Max continues to make his mark, working with clients including the NBA G League’s Windy City Bulls.

Alexander LaMonica knows firsthand the fear, uncertainty, and isolation that teenagers with cancer can feel. “Finding someone to talk with who ‘gets it’ is imperative to our sense of happiness and belonging,” he shares. His mission is to create a forum where teen cancer patients and survivors can find, connect with, and support each other. Inspired by Alexander’s journey, his friend Sabine Fuchs, an advocate for mental health at Branson, eagerly joined his cause. In early 2023, Alexander and Sabine won the inaugural Branson Impact App Challenge, giving them the technical support to build a new app and the platform for advocacy within the medical community to make their dream a reality. A pivotal moment was attending the Pacific Pediatric Neuro-Oncology Consortium conference, where they networked with physicians, researchers, and patient families from all over the world. “We were the only teens there,” said Sabine. “We stuck out like a sore thumb, but that was really helpful because people were curious and approached us to learn more.” As a team, the pair complement each other well, “Sabine is incredibly empathetic, she understands the mission, and she is definitely a people-person, which is helpful,” Alexander notes. “I bring the ‘why’ and I also have an interest in app engineering.” Now in the final stages of development, their app, Nectar Connect, is set to launch in the App Store soon. And the name? Alexander explains: “Nectar was the legendary, ancient Greek drink of youth and health. It’s restorative.”

Each year, the CIF North Coast Section evaluates its roster of 177 public, parochial, and independent schools of all sizes from across Northern California. They consider each school’s athletic success, assess its academic performance, and evaluate its student-athletes’ behavior and sportsmanship. From this, just one school is selected to win the Elmer C. Brown Award of Excellence, their highest honor.

Four out of the last five years that the award has been given, they’ve chosen Branson.

“When we say that ‘Branson is a small school that plays in the big leagues – and wins,’ we’re not kidding,” says Athletic Director Frances Dillon. “We’re so much smaller than nearly all of our competitors. And yet – with 14 State Championships, 79 NorCal Regional Championships, 98 North Coast Section Championships, and 189 Marin County Athletic League Championships – our student-athletes’ dedication speaks for itself.”

What does it mean to win the Elmer Brown Award four times?

“This is a huge award – the biggest award we give out to any school,” stated CIF North Coast Section Commissioner Pat Cruickshank. “It speaks volumes to the well-rounded studentathletes that you have [at Branson]. You put a lot of importance on athletics, academics, good behavior, the arts. It’s more than just what happens on the court.”

Christina Mazzola Head of School

James Zimmerman Chief Advancement Officer

Jennifer Owen-Blackmon Director of Communications

Olivia Flemming Assistant Director of Communications

Mission Minded

Julia Flynn Siler ‘78 is a New York Times best-selling author and journalist. Her most recent book, The White Devil’s Daughters: The Women Who Fought Slavery in San Francisco’s Chinatown, was a New York Times Editors’ Choice and a nonfiction finalist for the California Book Award.

Pages 6-11

Elisabeth Leamy ‘85 is a journalist, author, and speaker best known for her work as the Consumer Correspondent for ABC’s Good Morning America and her Washington Post consumer column. She never met Helen Dewar, whom she profiled, but feels grateful to her for paving the way.

Pages 32-33

Sarah Muench is an Emmy Awardwinning video producer and writer whose passions include international development, humanitarian aid, and presenting information to mass audiences on behalf of mission-driven organizations.

Pages 16-17

Guy Raz P’27 is the host and creator of several of the most well-known podcasts including How I Built This, Wow in the World, TED Radio Hour, The Great Creators, and others. Earlier in his career, he spent 15 years as a TV and radio reporter for CNN and NPR where he covered war, peace, and everything in between from more than 45 countries. He is the parent of a current Branson 9th grader.

Pages 28-29

Jeff Symonds P’22 is the Director of Studies at Branson, where he has been trying to summon and inspire courage since 1991. In his spare time, he’s a rock musician, podcaster, and parent/partner.

Pages 12-15

Jason Warburg ’80 is a writer and communications consultant and the author of four books, both fiction and non-fiction. He spent nearly three decades in senior communications positions for nonprofits and elected officials.

Pages 24–27

Kody Chamberlain is an award-winning artist who has written and illustrated comics and graphic novels for Marvel Comics and DC Comics, and whose work has been optioned for feature film development by Universal and 20th Century FOX.

Pages 32-33

Olympia de Maismont, photo and video reporter, has been based in Burkina Faso since 2013. She has covered major events, from coups to elections, as well as the rise of jihadist insurrection in the country for international media.

Pages 16-17

Steven Meckler is a commercial photographer living in Tucson, Arizona. His love of photography is grounded in the medium’s unique storytelling ability.

Pages 6-11

Karl Schmidt has taught physics at Branson since 2013. He has a background in outdoor education and his courses emphasize experiential learning. He is an avid trail runner and outdoor adventurer who enjoys the artistic pursuit of travel photography.

Front/Back Cover, Pages 2-3, 18-23

Ashley Thompson and Ana Homonnay are a San Francisco based photography duo who share a natural aesthetic and a passion for visual storytelling. They have been recognized by the International Photography Awards and were named Best of California by PDN.

Pages 24-29, 34-35

Brian Wedge is a Marin and Hawaii-based award-winning photojournalist, creative director, and visual storyteller who collaborates with editorial, commercial, and education clients around the globe. His work has appeared in print and online with Patagonia, Lululemon, National Geographic, The New York Times, Stanford, and Yale, among others.

Pages 4-5, 12-15, 30-31, 36-39