The Garden Of ideas

Dear Reader,

I

n this second edition of the second volume of The Garden of Ideas, we are pleased to publish three philosophical papers, as well as a short story and a collection of photographs. The pieces in this edition contain reflections on important questions in political philosophy and moral philosophy, as well as philosophical work of a not strictly academic variety. All of this work, however, engages in a reflective task of self-understanding, where we understand this task not to be constrained by any particular format or style, and to have as its object not just the individual person considered in isolation, but also the social, political, and historical situation in which one finds oneself. We are also proud to continue to engage in a series of rich conversations with contemporary philosophers about their work. This past quarter, I and a fellow editor, Nate Pedersen, interviewed Béatrice Longuenesse, about her work on Kant and the first-person pronoun I, Me, Mine: Back to Kant and Back Again. For both of us this was an immensely enriching experience; speaking to great philosophers is one way of enriching one’s own philosophical skills. The link to this interview is on our website, gardenofideasuw. com, and I hope many others will benefit from listening to Professor Longuenesse speak about her work, as we did. These interviews have been one way in which, I believe, the philosophical culture at the UW has been enriched by our work at the journal.

The last thing which I would like to mention is the admiration we all ought to feel for the

excellent work of our contributors to this edition of the journal. The Winter quarter at the UW is often difficult for reasons having variously to do with the weather, as well as the stressful pace of the quarter system, and so it is often the Winter quarter which poses the greatest challenge to the publication of our journal. But we have been fortunate to receive a wide selection of work this quarter, and we believe that the variety which is contained within the pages of this edition demonstrate the continuing spirit of widening our conception of how one can think philosophically, which is the guiding principle of our journal. In addition to acknowledging the work of our contributors, I would also like to thank the editors, whose careful deliberation and thoughtfulness guided the process of reviewing this quarter’s submissions, and all the other members of the journal, whose hard work made possible the publication of this edition. There is one person in particular to whom I wish to express my gratitude: our public relations officer Harrison Fitch, who is graduating this quarter. Harrison has been with the journal since its beginnings last Fall, and he has contributed an incalculable amount to its success and maintenance. There are many specific things which I could mention, but I will leave things at this: this journal simply would not have succeeded, or published at all, if not for Harrison’s work. For his contribution to this project, I am extremely grateful.

Braeden Giaconi Editor-in-ChiefThe ‘Holy Trinity’ and ‘Crimmigration’: A Two-Pronged Challenge to Closed Borders

Many people seem to have the normative presumption that states have the right to exclude potential immigrants and that they ought to exercise this right. The limitations of the right to exclude vary based on people’s moral dispositions, yet I find that most people allow and recommend for at least some exclusion. There are many philosophers who share this logic, including Michael Walzer, David Wellman, and Michael Blake, among others. Each of these logicians contends that states can exclude potential migrants to a certain extent. However, none of their theories, I argue, satisfy what I call Mendoza’s ‘holy trinity of exclusion.’ Also, even if we suppose that one of these theories can satisfy the ‘holy trinity,’ Mendoza details that such policies lead to an undesirable consequence: ‘crimmigration.’ In this paper, I will present a two-pronged, indirect argument for open borders. Primarily, I will argue that no theory that grants states the right to exclude migrants can satisfy the ‘holy trinity,’ so they are inadequate. In the second part of my paper, I assert that even if we waive the ‘holy trinity’ requirement, policies that exclude migrants foster ‘crimmigration,’ which imposes social and moral costs that are too hefty to bear. My conclusion is that due to the apparent failure of contemporary theories of exclusion to meet the ‘trinity’ threshold, and the repugnant consequences of exclusionary

theories, perhaps the normative presumption to exclude should be questioned and the openborders positions reevaluated as a viable theory.

Ι. The ‘Holy Trinity’ and its Elusive Nature

Mendoza’s ‘holy trinity of exclusion’ is nothing more than three criteria that must be met if it is to have just exclusionary policy. The first condition that we need is that a state be liberal. Liberalism is a feature of most Western democracies. Liberalism is a type of political doctrinethat undergirds a government’s policies and aims. Specifically, liberalism emphasizes the importance of individual liberty and equality, and the government’s role in protecting them. Liberalism has certain branches such as egalitarianism, utilitarianism, and libertarianism; however, it is distinct fromother governmental frameworks like communism and anarchy. Most governments and democracies today are committed to some form of liberalism. This means that a lot of countries satisfy the first condition, but also implies that countries cannot deviate from liberal standards and virtues. Although an argument could be made that some, like the US, are committed to liberalism only when convenient, I will postpone discussing such ‘quantum’ liberal states. It is not an ambitious assumption to say that states espousing liberal

doctrines ought to act in that way, even if they do not at times. The second condition is straightforward: states have the right to and can exclude migrants. While this might be thought of as glaringly obvious, a condition a just theory of exclusion must satisfy is that exclusion of migrants by states is permitted. The final condition that a theory of exclusion must meet before implementation is that it is not discriminatory. Essentially, any policy that excludes must not discriminate against a certain group without warrant – the cases where discrimination is warranted are extremely rare and non-existent for powerful states like the United States. Often in immigration policy, the ‘groups’ that are sanctioned or disadvantaged are along racial, ethnic, or country of origin lines. Thus, this last condition is a bulwark against racism. A policy cannot disadvantage a certain group due to arbitrary whims. It is possible to create a policy that ignores this third requirement, but I argue that racist ideology should not, in any shape or form, be associated with immigration policy. Discrimination inevitably leads to racism, so it must not be part of any policy that wishes to exclude migrants. While it is not difficult to individually satisfy the three conditions of the ‘trinity’ – liberalism, exclusion, and non-discrimination – satisfying all at the same time is, I argue, currently not possible.

I will begin detailing current exclusionary theories that do not meet the trinity conditions by discussing Michael Walzer’s communitarian theory. Walzer’s theory immediately fails to satisfy the liberalism condition as he leans towards a more communitarian stance, but his theory merits attention as it meets condition two and three. The key tenet of Walzer’s theory is that “what we do with regards to membership structures all our other distributive choices” (Walzer 31). In essence, how we distribute membership, the ‘primary good’ according to

Walzer, is paramount in determining what, and to whom, we distribute other goods to. Everyone that receives membership is part of the social contract and is entitled to its benefits, but what we owe to those residing outside the social contract is unclear for Walzer. This problem would not arise if everyone in the world was given a sort of ‘global citizenship’ at birth, but Walzer notes that this is not likely to occur soon. Walzer then postulates that we should consider immigrants as strangers in need whom the state does not have an obligation to protect, and ought to help only if it is needed and if there are few risks involved. He says immigration is a political decision that members can play a part in, but “they decide not for themselves but for the community generally” (Walzer 45). In this manner, Walzer gives priority to the needs and desires of the community as opposed to the rights and liberties of individuals. The best analogy for a country according to Walzer is a club, he says, “we might imagine states as perfect clubs, with sovereign power over their own selection processes” (Walzer 41). Most decisions to exclude under Walzer’s theory would not be discriminatory, they would simply protect the interests of the community, the club. Although some policies under this ideology could be racist and fail condition three, all I am attempting to show is that it is possible to use Walzer’s method to achieve the third condition. Quotas or skill selection policies serve as means to accomplish this. However, as I mentioned, Walzer fails to meet criteria one: liberalism. Unfortunately for Walzer, his theory is diametrically opposed to liberal tenets. Walzer’s case rests on the premise that a state’s immigration policy is enacted to further community aims or protect and shelter the community. This is counter to liberalism in that it prioritizes the needs of the community ahead of individual liberty and equality. To satisfy the three criteria, one must consider the state as ...

liberal since it more accurately reflects the political reality of states like the US. A communitarian approach to immigration would be dubious in the US for example, as the US is liberal and is very keen on advocating for individual liberty and equality. In conclusion, Walzer’s theory can exclude in a way that is non-discriminatory (conditions 2 & 3) but fails to satisfy the trinity since it is not liberal.

Now, I move on to discussing David Miller’s theory of exclusion, its success in meeting conditions one and two, and its failure in satisfying condition three. Miller says it is “possible both to argue that every member of the political community … must be treated as a full citizen, enjoying equal status … and to argue that there are good grounds for upper bounds both to the rate and overall numbers of immigrants who are admitted” (Miller 193). In this sense, he is arguing that liberalism and exclusion of immigrants are compatible. Miller accomplishes this by arguing that the right to live wherever someone wants is not a ‘basic’ or ‘bare’ right. Basic/bare rights are those that must be protected and afforded to everyone under a liberal framework. Such rights can be sufficient access to food, water, and shelter; a state must take it upon itself to provide these to its members. However, non-basic rights do not require protection from the state. Non-basic rights can be the right to own a luxury item like an Aston Martin for example: while I could possibly attain such an item and I would have the right to own it, this does not mean the state must ensure that this right is fulfilled. Miller classifies migrating to a country of choice as a non-basic right. One reason why is that while the right to bodily autonomy and freedom of movement is a right, states already provide their members with sufficient space to move – unlimited freedom of movement is a non-

basic right. Having established that unlimited migration is a non-basic right and that states are not compelled to protect and enforce them, Miller gives us two potential reasons for exclusion: culture, and population control. So far, Miller has met the first two conditions as his account is liberal – grants everyone basic rights equally – and can exclude, but the reasons he provides for exclusion are the reason he fails the third condition. Focusing on the culture argument, Miller says that immigrants change the culture of the state and that the “public culture of their country is something that people have an interest in controlling” (Miller 200). Thus, since members have an interest in controlling culture, they can pick and select what immigrants, if any, to let in. This is a slippery slope that turns into discrimination in an instant. Given this premise, states will be compelled to let in individuals whom they deem will impact their culture the least which gives states an incredible power that they are apt to misuse. Often, such culture arguments will lead to racial discrimination. Culture serves as a guise that hides blatant discrimination. Even if people are genuinely concerned about protecting culture, exclusions based on this overlap too well with racist policies for it not to be considered discriminatory. The intent may be pure, but the results are clearly not. Thus, Miller provides a theory that satisfies the first two conditions of the trinity but fails to be nondiscriminatory.

Finally, Christopher Wellman, uses ‘freedom of association’ to prove states have the right to exclude anyone, but also fails to be non-discriminatory. Wellman begins by describing how crucial freedom of association is to liberalism and uses marriage – a recurring analogy in his work – to illustrate this. Wellman says, “each individual has a right to choose his

or her marital partner” (Wellman 110), meaning each of us has the right to associate with a partner if we want to. Concealed or implied in this right is also the right to disassociate. He points out that “one must also have the discretion to reject the proposal of any given suitor” (Wellman 110). This is how Wellman meets the liberalism condition: he relies on and stays true to freedom of (dis)association, a critical component of liberal theory in addition to other liberal commitments as well. Having established that individuals have a right to associate and disassociate, Wellman proceeds by endeavoring to show how individuals are like groups in this sense. His main idea is to tout the negative consequences of a state’s lack of freedom of association – one nation could annex another, since the latter did not have the right to disassociate. Wellman emphasizes that this freedom to associate is a ‘presumptive’ right, not a right that trumps everything. However, he sets the presumptive bar high, allowing states to exclude even refugees because he is “not convinced that the only way to help victims of political injustice is by sheltering them” (Wellman 128). Other ways to help refugees, such as exporting justice financially or intervening via the military, are why Wellman believes that states have the presumptive right to exclude even the most vulnerable of peoples: refugees. Thus, Wellman has given us a presumptive right to exclude – even people who are in dire need – that places the burden of proving entry on the immigrant by scaling the liberal value, ‘freedom of association’, from individuals to states as well.

However, Wellman faces the same roadblock in condition three that Miller failed: discrimination. Given racist immigration policies, Wellman says he is “not convinced that [potential immigrants] have a right not to be insulted this way” (Wellman 139), meaning that his account could allow such policies.

The defense against claims of racism and discrimination Wellman tries to establish is that racist immigration policies are wrong not because they insult the potential immigrant, but because they insult and degrade already existing members of a group. Wellman uses this to disparage the ‘White Australia Policy’, stating that “it is not difficult to see how Black Australians, for instance, might feel disrespected by an immigration policy banning nonwhite” (Wellman 140). In essence, Wellman’s policy leads to a conclusion that racist immigration policies are wrong solely due to the wrong they cause to members. This is a half-hearted attempt at stemming the bleeding in the theory caused by its capacity for racism. The easiest way to prove this is racist and discriminatory is if we consider a homogenous society like Japan; this society could exclude whomever it liked since they would not cause any harm to members given that all their members were Japanese. Japan would then be allowed to discriminate against whomever it wished to. However, despite Japan’s case, there is something off about an account that condemns racism for the wrong it causes to members and not for the wrong it causes to the people directly impacted by it. This would lead to scenarios where a football team would be permitted to use racial slurs targeting the opposing team and the reason why they would be reprimanded would be because it would actually insult their own team. This is ridiculous. Clearly, Wellman’s theory, much like Miller’s, fails to give an account of exclusion that does not discriminate.

I have thus far outlined three prominent theories of immigration that all permit exclusion, yet none of them have been able to satisfy the ‘holy trinity’. Walzer failed condition one, and Miller and Wellman fell prey to condition three. If a policy of excluding immigrants must satisfy the three conditions ...

imposed by the ‘holy trinity’, there is apparently none to turn to. While I have not covered every theory of exclusion, given the gravitas of the three described and their acceptance as leading theories in the field, we can safely conclude that a theory that satisfies the ‘trinity’ has either not been written yet, or suffers from deficiencies that are so great that it does not warrant discussion.

II. ‘Crimmigration’: The Price of Exclusion

Suppose a theory that satisfied the three conditions of the ‘holy trinity’ manifested itself. This would beg the question of whether we should adopt it. I argue that even with such a policy the price to pay for exclusion, namely ‘crimmigration’, is too heavy a burden to bear.

Crimmigration is a term philosophers use to describe three problems that arise due to the link between immigration and law enforcement. According to Mendoza, the three problems crimmigration encompasses are “when criminal convictions come to have immigration consequences … when immigration law violations come to have criminal-style punishments … [and] when the tactics sanctioned for criminal law enforcement are commandeered for the purposes of performing immigration enforcement or vice versa” (Mendoza 50). These three problems inevitably occur if immigration is barred or limited. In the US, for example, Immigrations and Customs Enforcement (ICE) regularly interacts with local law enforcement to discover and potentially deport irregular migrants. Given that these problems regularly manifest, Mendoza describes why each of them are morally repugnant and ought to be remedied.

First, Mendoza addresses why criminal convictions leading to immigration

consequences are unjust. Two compelling reasons Mendoza cites for this are that such a course of action punishes someone twice for the same offense, and that deportation –specifically for long-term residents – is too cruel and unusual a punishment. While there are certain occasions where double jeopardy is permitted – a drunk driver gets fined and loses their license – “this second punishment is just … not only because of the causal connection … but also because it is narrowly tailored to a specific purpose” (Mendoza 57). In essence, if there is a direct link between the crime and the secondary punishment, or if the secondary punishment is narrowly tailored to a specific purpose, it is permitted. However, tacking deportation onto a criminal punishment does not appear to fit into either category, so it is unjust. Punishing someone twice for the same offense is unjust and not permitted in the Constitution. There is no compelling reason why immigrants should not also be afforded this protection. In addition to this, the Constitution protects against cruel and unusual punishment. Deportation added onto a criminal conviction certainly appears to be cruel and unusual since it leads to what Mendoza calls “a fundamental reordering of one’s life” (Mendoza 58). There is a reason contemporary society does not exile or banish people. Again, there is no valid reason as to why immigrants should not be granted this Constitutional protection either. Thus, Mendoza successfully establishes that criminal convictions that have immigration consequences are unjust and morally unsound.

Next, Mendoza details why immigration charges that have criminal-style punishments are also unjust. The federal government, Department of Justice (DOJ) specifically, has plenary or virtually unlimited power over immigration. This means the DOJ can act very

freely, without much judicial supervision. Mendoza argues that the federal government must regard immigration as a civil penalty since criminal defendants are entitled to due process rights and protections while civil infractions are not afforded this protection. The DOJ does not provide due process, as rulings are made by a federal judge without input from a jury of peers. Essentially, since the DOJ does not provide due process, it cannot levy criminal penalties like incarceration as those types of penalties require due process. According to Mendoza, this leads to a tradeoff where “in the areas where the federal government can exercise coercion … that individual is entitled to a robust set of protections … However, in cases where the federal government is not technically coercing individuals … these individuals are not entitled to typical constitutional protections” (Mendoza 61). The coercion Mendoza refers to can be instances when the federal government attempts to take one’s life, liberty or property, while the protections he speaks of are the due process rights that I mention above. Thus, when the federal government levies coercive, criminal punishments, those individuals have due process protections. On the other hand, if a government is non-coercive and only levies civil penalties, then individuals are afforded less protection. This is all to say that since criminal punishments tend to be coercive, the federal government has no right to issue them to immigrants unless they are granted more protection. In conclusion, the issuance of criminal punishments by the federal governments for immigration offenses is extremely problematic and unjust.

Finally, Mendoza details why mixing immigration and law enforcement tactics is morally problematic. A reason that the marriage of immigration and law enforcement is problematic is due to the tight link between immigration and local police authorities. This

collaboration fosters and cultivates injustice. Such a partnership sows mistrust among police and immigrants. Mistrust is not a problem in and of itself, but Mendoza suggests that “immigrants are less likely to call on them (police) when they are victims of crime or come forward as witnesses to help solve crimes” (Mendoza 63). Injustice and crime will thrive if the police cannot effectively do their job or are not aware of a significant number of crimes. Since immigrants are less likely to report crime, this makes them a perfect target to exploit. Instances of rape and murder never come to light due to the mistrust between immigrants and police. In essence, mixing immigration and law enforcement tactics is conducive to an environment where injustice can thrive unbridled.

In summary, crimmigration poses three problems that all have significant immoral and unjust results. Whether its criminal convictions invoking immigration penalties, infractions of immigration law resulting in criminal-type punishments, or mixing immigration and law enforcement tactics and strategies, all these aspects of crimmigration are very troublesome and pose a threat to justice. Crimmigration is rampant in the US and while it is not a direct result of exclusionary policies, it is evident that exclusionary policies are at least conducive to it. For example, there would be no double jeopardy of receiving an immigration-related punishment for a criminal offense if immigration was simply legal in all instances. I am not saying that no crimmigration would occur under an open borders policy or that there is no exclusionary policy that does not succumb to the problems of crimmigration. Rather, I want to question the normative presumption that states have the right to exclude migrants and suggest that perhaps the open borders position is practically not as ludicrous as it sounds in theory. ...

III. Conclusion

In this brief essay, I have, in essence, advocated for an indirect open borders position. I sought to achieve this in two ways. Primarily, I established the ‘holy trinity of exclusion’ as the standard a satisfactory theory of excluding immigrants must satisfy. Having found no prominent theory that met this standard, I implied that perhaps the open borders position could be scrutinized a bit more. Subsequently, I discussed a problem that arises even if a policy justly excludes and satisfies the ‘trinity’: crimmigration. I detailed crimmigration and the injustice that it perpetuates and implied that perhaps these injustices would not occur under the open borders framework. In conclusion, due to the failures and deficiencies of current exclusionary accounts, I am convinced that the open borders position advocated for by philosophers such as Joseph Carens merits special attention, if not outright acceptance.

Citations:

Walzer, M. (2010). Spheres of justice: A defense of pluralism and Equality. Basic Books.

Cohen, A. I., Wellman, C. H., & Miller, D. (2005). Immigration: The Case for Limits. In Contemporary debates in Applied Ethics (pp. 193–206). essay, Blackwell Pub.

Wellman, C. H. (2008). Immigration and Freedom of Association. Ethics, 119(1), 109–141. https://doi.org/10.1086/592311

Mendoza, J. J. (2020). Crimmigration and the Ethics of Migration. Social Philosophy Today, 36, 49-68.

Buying into nirvana

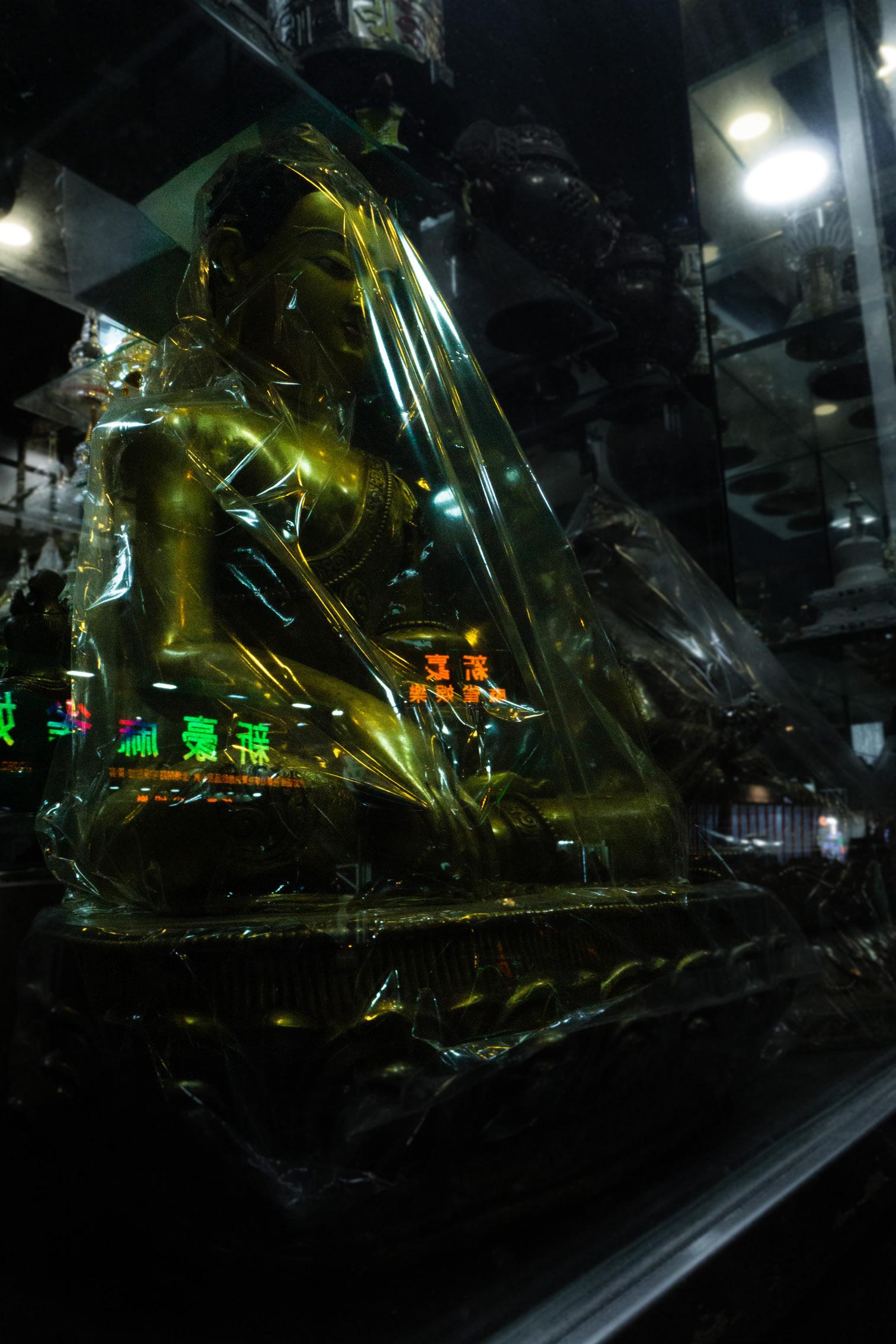

It is the Second Noble truth of Buddhism that desire is the root of all evil. However within today’s consumer culture, our lives are shaped by the forces of supply and demand. To survive in such an environment, Buddhism has been commercialised, its principles bundled up in goods of desire.

This photo series explores the commodification of Buddhism in Hong Kong, a city known for its extremely free market economy but also a large portion of the population being Buddhist or engaging in Buddhist practices under a wider umbrella of Chinese folk religion which takes elements from Buddhism and Taoism.

Photos and Words by Justin Wong

On Bell’s Interest Convergence

The way law is implemented in society oftentimes does not reflect the way it is duly promulgated on paper or in court. For instance, although murdering someone was illegal, human rights violations such as lynching were regularly practiced for decades in the United States. Even officials that held positions in the criminal justice system engaged in atrocious practices of lynching—none of whom faced punishment. This is but one egregious example that depicts the way society can perpetuate injustice, (Rushdy, 153). The United States was founded on the slavery of black people and the genocide of native peoples. The U.S. upheld state-sanctioned segregation through black codes, as well as restrictive covenants and redlining. This is evidence that racism is embedded in the status quo of the United States. For this reason, calling for racial justice in the form of cases like Brown v. Board of Education is fundamentally challenging the status quo. Changing the status quo is

thus inherently required for achieving racial justice. The question then becomes, how can a society change the status quo through law? In this essay I argue that Bell’s Interest Convergence theory offers a way to achieve change through law if implemented on both a de jure and de facto level.

Bell argues that social reform will never happen unless it is desired by those on whom the status quo is contingent. Bell asserts that if individuals benefit from a system, they will not easily agree to have their extra privileges taken even if it is for the purpose of furthering just ends. Instead, Bell claims that there needs to be a convergence of interest for those who uphold the status quo to surrender their privileges. Bell explains that Interest Convergence Theory “provides: The interest of blacks in achieving racial equality will be accommodated only when it converges with the interests of whites… However, the fourteenth amendment, standing alone, will not authorize a judicial

remedy providing effective racial equality for blacks where the remedy sought threatens the superior societal status of middle and upper class whites,” (523). In this quote, Bell refers to the Brown v. Board of Education case to show how interest convergence theory functions. He asserts that white people who benefit from the oppression of black people feel threatened by integration because a segregated society maintains white superiority over black people. Therefore, to achieve true equality and integration, society needs more than the racially neutral fourteenth amendment, which has been historically unable to tangibly change the conditions of racial inequality in society. Put differently, Bell argues that in order to achieve change through law, society needs white people’s interests to align with the goal of furthering racial justice.

Bell demonstrates that cases like Brown prove that change through law is difficult to achieve because these sorts of cases often prematurely create

Convergence Theory

a perception of justice having been achieved on a de jure level, which disincentivizes those who uphold the status quo to actively engage in working towards change on a de facto level. Bell asserts that Brown v. Board was pushed forward based on the convergence of white people’s interests drawing from three main surface level arguments—all of which were not necessarily intended to achieve true racial justice. First, white policy makers and people in power thought that abolishing segregation would provide the U.S with economic and political benefit on an internationaldomestic level. Furthermore, they thought that segregation made the U.S. look bad both at home and abroad. This would help the U.S. “win over the hearts and minds” of other countries as they fought communist countries. Secondly, white people feared that black veterans who risked their lives in World War 2, who came home might decide to become communists because a segregated society

backed by capitalism was demeaning. Lastly, Bell highlights that white people realized that “the south could make the transition from a rural, plantation society to the sunbelt with all it’s potential and profit only when it ended its struggle to remain divided by state-sponsored segregation.” Conclusively, Bell argues that Brown was only made possible because white people who uphold the status quo ultimately saw benefits of de jure integration that was rooted in incentives rather than justice or morality.

When it came to implementing Brown’s holding of racial integration into society, a divergence of interest occurred among white people on a de facto level which stifled the ability for change through law to be fully carried out. Bell explains that, “further progress to fulfill the mandate of Brown is possible to the extent that the divergence of racial interests can be avoided or minimized.” (528) In other words, implementing the Brown holding into society is contingent on the extent to

which white people seek to implement this change. The divergence takes the form of white flight, discrimination towards black students in classrooms, and the incredibly slow integration efforts— all which were examples of how white people’s interests diverged on a de facto level. Thus, when those who uphold the status quo are not incentivized to change on both a de facto and de jure level, change is bound to fail, because those who uphold the status quo will defer to protecting the benefits that they are afforded by the current system.

Legal philosophers Delgado and Stefancic would argue that convergence theory would not be able to achieve this radical change. That being said, they would agree that achieving change through law is incredibly difficult. However, they assert that “everything must change at once” to achieve real change. To support this, Delgado and Stefancic would refer to the reconstructive paradox. The reconstructive paradox is ...

ultimately defined by the resistance that is created in reform through the social gravitational field. They argue that this social gravitational field is created by the beliefs, narratives, meanings, and social practices. Based on this social gravitational field, Delgado and Stefancic argue that the Reconstructive paradox posits that, “The greater a social evil (for example black subordination) the more it is apt to be entrenched in our national life….The harm of an entrenched evil will be invisible to many because it is embedded and ordinary.,” (559). Put another way, social evils like racism are deeply embedded in U.S. history. These social evils are rendered essentially invisible by the social gravitational field. Furthermore, they state that, “Narratives are the simple, script-like interpretive structures…that we use in ordering our understanding of the world.” (556-557) In other words they argue that people who support the status quo do this not because they are consciously racist and want to protect their privilege, but rather because they operate off narratives derived and perpetuated by the social gravitational force which are used to form their

understandings about the world. Stefancic and Delgado would argue that the social gravitational force is very difficult to change, thus it is unlikely that a convergence of interests, which builds upon social gravity, will occur if it disrupts the natural social order of the status quo. Delgado and Stefancic further add that interest convergence theory will always be based on surface-level justice, which renders it even more susceptible to failure when faced with the reconstructive paradox. The Reconstructive paradox proves that the deep entrenchment of social evils in society requires a process of achieving change that both recognizes the issues for what they are and addresses them with a solution that is proportional to the magnitude of the social evil. It posits that, “the greater the reform effort, the more unprincipled and unjust the effort will seem, and the greater the resistance it will call up.”(568) To put this differently, Delgado and Stefancic explain that large scale social issues require large scale resolutions. However, the irony of the Reconstructive Paradox is that resolutions or changes that intend to solve these social issues will be perceived as disrupting

the social gravitational force. This disruption and perception of threat will grow larger as the resolution and necessary changes to solve it grows larger. Since the reconstructive paradox already weakens efforts of reform for simply being a reform measure, it becomes even more imperative that a resolution clearly identifies the social evil for what it is and directly addresses it. Delgado and Stefancic would assert that interest-convergence theory is unable to do this, and instead functions only when the interest of those who uphold the status quo just so happen to overlap with justice. Thus, because it fails to name and directly address social evils it is unable to withstand resistance from the reconstructive paradox, and it will ultimately fail to achieve progress on anything more than a surface level.

Since the reconstructive paradox explains that reform will be met with push back if it challenges the status quo, then interest convergence is exactly what is needed to create change because it leverages people’s interest, and for this reason it is less likely to be perceived as unjust or an attack on the status quo. Furthermore, even interest convergence on a de

facto level is possible, despite it being slim. In the context of Brown, Bell accepts the fact that white people are against integration on a de facto level. Bell does not hide that he too is skeptical as to how much meaningful change can be achieved through law using interest convergence theory. In response to this fact, he advocates for the black community to rethink how they are going to use their resources to their advantage to achieve the goals that Brown v. Board is failing to deliver on—namely, a quality education for black students. He states, “successful magnet schools may provide a lesson that effective schools for blacks must be a primary goal rather than a secondary result of integration,” (532533). Here, Bell is advocating for “model black schools” as a way to obtain quality education for black students. Thus, Delgado and Stefancic are correct in thinking that convergence theory will not radically change everything. In fact, he recognizes that interest convergence theory can create superficial justice because it does not directly address deeply entrenched societal evils, rather, it uses interests that overlap with justice. However, the option remedy that they offer which is creating a completely new legal regime—is, again, probably not a viable option, especially

if those who uphold the status quo are not supportive of this. Given the reality of the reconstructive paradox, which argues that the larger a societal reform is, the larger push back it will receive, interest convergence theory is the most realistic way to mitigate push back and therefore achieve change.

As seen in Brown v. Board, society does not meaningfully change if change is not implemented on both a de jure and de facto level. Bell’s argument better addresses this distinction compared to Delgado and Stefancic because interest convergence theory offers an explanation as to why society is confronted with cases like Brown on a de jure level, as well as why they fail on a de facto level. The importance of de jure law is best described by Catherine Mackinnon. In her essay “Toward Feminist Jurisprudence,” she states, “In liberal regimes, law is a particularly potent source and badge of legitimacy, and site and cloak of force…The force underpins the legitimacy as the legitimacy conceals the force.” MacKinnon further depicts that society and all of its injustices are latent in law itself, and thus, the law is transformed into a perceived neutral force that upholds injustices in a legitimized manner. In this sense, Mackinnon importantly highlights de jure law being a

legitimizing force that weighs on society by virtue of simply being law. Subsequently, a de facto convergence without the legitimacy and protection of de jure law is less solidified, despite its effects being undoubtedly apparent. Both of these processes feed into each other. Integration efforts without a law legitimizing it is weaker because it lacks the backing to require individuals to actually follow through. Likewise, a law banning segregation without being carried out in practice ultimately is rendered as nothing more than a weighted obligation for society to change. Because we live in a society where change is contingent on those who uphold the status quo, interest-convergence theory offers a way to leverage the interests of those who uphold the status quo to change. Therefore, interestconvergence theory offers a way to leverage resources— namely, the interest of those who uphold the status quo— to accomplish actual change. Change is thus only possible if interests converge on both de facto and de jure levels.

Works Cited: Rushdy, A. H. A. (2012). American lynching. Yale University Press.

The Sick day

By Henry RileyIn keeping with tradition, I would begin with rage, but I must have misplaced it somewhere. I remember being an angry child — where did that go? And anyway, to render such violence correctly would require perfect calm, and I haven’t the heart to worry about the ironies compelled by authenticity. And any effort at it would be useless if it didn’t reside in you already.

The air out here is heavier than it should be too, so aesthetic integrity is right out. And beneath the standard industrial funk the smell of savory baked goods — probably German, not that I’d know — is just combed beneath the breeze. And that thin, belabored air long ago succumbed to the modern hum and tides of traffic. Its defiance, if it can be called that, is in its incompetency, so that sounds run together, even into the smell of the air. But the birds are like crystal, though I know it’s been said too much. I imagine I could hear them even without a medium to carry the sound. Sometimes, lying in bed, her breathing seems to disappear and I hear as if all around me the songs of all kinds of birds, the lovely inflection points around which the tune turns and which signals another to begin. I have to concentrate quite hard to discover if the sound is in my head or the world; I’ve found they don’t really start till 4 am.

I only just noticed the smell of the dirt, even this close to it. It was cold this morning, so for a while that copper smell that gets laid over everything probably prevented it from coming through. It hasn’t rained in a few days. For myself, I could try to apprehend a little pathos, but it's terribly undignified to oppose the end of things, to want more or more deeply than another. “Have some decorum, son!” Yes, indeed. Excuse me.

Well, I’ve crawled a long way into the mouldering earth. It’s actually quite pleasant here. I think we’ve always best understood the burrowing kind of animals. Or even if we haven’t it’s a fun thing to think anyway. By the “mouldering earth” I really mean I’ve been lying on the ground. This is transcribed exactly from what I memorized there — or at least, I hope(d) so. By “crawled into” I don’t suppose I meant anything. A reversion to childhood, maybe.

So yes, that line was constructed in past tense to denote the time of transcription, but yes I’m lying “here” on the ground as I try for words. And I (will) have resisted the urge to editorialize myself — you’ll have to take my word for it, as I will. I’ve been thinking everything twice so as to get it down accurately.

Well, I’ll try my best.

“Here,” the ground, is a nice flat bit of dry slightly spongy earth beneath the shade of a plum tree. It’s raised a little by the roots near the tree, so I’ve got a little pillow. The song of the birds is (or was, at time of transcription), I think, like the twirling of glass rods, arranged in a dusty attic, the wood rotting about it to let in the sun. Then.

There is a little moss below the heel of my left boot.

Very cushy.

But it is likely not so fond of me if it has the capacity for fondness and things as that, indeed it would likely hate me if it could. And as rage is the function of impotence and defiance, the self-insisting function, it would perhaps be better to think of it as vengeful. Yes, if it is anything it must be angry. I’d like it to be fond of me. But if it could experience such things it couldn’t be fond of me. I’m attached to it now, really. It’s easy to see how more animistic ideas take hold, I caught myself talking to it before I set out to make a record of today. A whole awkward conversation: “you know, you’ve been in my yard all this time and I’ve never really noticed you…”

And it: “...”

And myself: “Ha! Yes, I suppose. Still, lovely day.” And I meant it, for all the silliness of the thing. But really I meant “loveliest.”

The neighbors would find it very strange if they saw me. Or, I should say: they will find it very strange when they see me. Of course at the time of transcription I will be (am?) in a position to be more clear, but to do so would go against the spirit of things. So I won’t be.

But why should they find it the least bit strange — for me to lie in the shade of a beautiful tree? Granted it’s actually rather stunted, sad, and isolated from any other tree, but it’s beautiful in its way and it shouldn’t be

strange to lie here. Even the way it’s pressed right up against the fence and the wall due to the tiny nature of the yard is beautiful in its way. They ought to try lying here too. Of course, it is my tree so it would actually be a little odd for them to do so, but not for me, and if they asked to, why — I’d let them and commend them for being so bold. It isn’t my fault if they find it strange. They will though.

Admittedly that was more a rant than anything. I’d find it strange too, and I’d feel a need to call “the authorities” — the vague kind, I feel there ought to be someone to call — if they asked to lie beneath my tree. The birds never sing exactly the same. The pattern is distinguishable, but I’ve actually found it harder to pin down the features of each than I thought it would be.

It began in the way these things so often do. It’s very clear now, lying here beneath this tree, quite simple and understandable; I have to laugh at how easily I got worked up over such a little thing. To put it neatly: I took a sick day, and it has been the finest day I’ve had in years. And I didn’t tell her, but if I had I would have had to explain myself and then she might have felt hurt. So I haven’t managed to feel guilty yet.

I only wanted to extend the day by documenting it like this. The birds sing so beautifully. Memorization lends itself to a certain seriousness, a flattening and move to subtlety which betrays the moment, because in memorizing we are at all times an opportunity to editorialize. Can I trust myself not to? I don’t really know. I’d like to. And when I write this (as I must “now” have done), I suppose I’ll know.

I planned the deed with the same slick, feverish excitement that another would plan a trip to France, or a murder, or a murder followed by an escape to France. The tricky part was to do without justification, but ...

once the thought’s allowed to work towards obsession that’s well taken care of. In fact, I was in such a state all last night and this morning that I really might have made myself sick and it’s a perfectly “true” sick day all the same.

I have weekends of course — Sunday and Monday — but on a weekend one’s already been scheduled out — has certain obligations — or if not then there’s the upkeep of of domestic felicity. We’ve planned our lives around each other, so we always have time together.

Ah, there we are. Prying eyes from a window — I’ll shift an arm so she knows I’m alive. Well, I shouldn’t be so harsh, neighbors ought to look in on each other, it’s in the name of public safety and community and such.

I should have been jealous, of course. Actually, I was jealous, really, I was! I could have played the part with aplomb. But there was a shallowness to the experience, in fact I only recall it in that it hadn’t nearly the effect it should have. I more observed that I was jealous, and that was all there was to the matter.

Would she have been better pleased if I was jealous? Possibly, quite likely. I don’t deny the beauty in the lines of her hands, the easy comfort of her eyes. But this has been such a pleasant day.

One needs excuses, these days, for the substance of life. As a child, one has an excuse without knowing it. Children may often do anything without being asked to explain it. They are being children, this is enough. Plum-stained sunlight.

I’d like to explain the delicacy of the way it traces the hidden veins of the leaves, the light purple-near brown of the surrounding leaf, the way the light which falls has a dolorous

way of being, rather than the unadulterated joy of light through green leaves. The way the sky is composed of blue beyond red leaves and is bisected by a thin black telephone line, slightly curved. This is the idyll summer day of youth, or at least a part of it. I wonder if I had any like these as a child or if my memory of it is just a composite. If I told her all this she would feel betrayed, concerned, estranged — and by that which I would tell her only for the sake of true intimacy.

I’ve counted five types of bird by their song, though I’ve only seen two. It really is as if they were all playing together — one will follow another, allowing brief silences, little rests made of the last note’s memory, looping into dissolution like sugar dissolving on the tongue. I can’t always tell when they’ve truly fallen silent. And the wretched static of traffic seems to fall away when I listen to them. My hair surely has some dirt in it; I will have to shower when I go in. I do not want to go in. But the moment must end while it is yet itself; It’s terribly undignified to oppose the end of things. And I can stay with these thoughts at least till I’ve finished the transcription. The kettle is boiling.

Supererogationism and Anti-Realism

By Ryan GarwoodAbstract

Supererogatory acts are said to be ethically good but optional. One intuitive objection is that, if an act is truly good, then it should be obligatory. Contemporary defenders of supererogatory acts argue that this is not so, as morality would become too demanding. Additionally, the more common strategy is to argue there are non-moral reasons that may override moral reasons. In this paper, I will sketch some worries with these strategies. I will argue that, since supererogationists deny that moral reasons are overriding, their position is open to anti-realism. Thus, if one wishes to be a moral realist, one ought to believe that morality is overriding and that there are no supererogatory acts.

Introduction

Following J. O. Urmson, many philosophers have felt it necessary to posit supererogatory actions—actions that are ethically good but optional. Supererogatory acts align with paradigm cases in which an individual seemingly goes “beyond the call of duty.” However, it may be objected that there are no such cases—if an act is good, then it is obligatory. The most common rebuttal among defenders of supererogation is to suggest that

moral reasons are not overriding, which allows some good acts to be optional. In this paper, I argue against the existence of supererogatory acts. It is my contention that, by allowing for the possibility of moral reasons to be overridden by non-moral reasons, supererogationists are straying too close to anti-realism.

This paper will be split into halves. In the first half, I will summarize the supererogation debate. Besides giving a more detailed description of supererogatory acts, I will provide the background knowledge needed to understand what motivates supererogationists to suggest that moral reasons are not overriding. In the second half, I will briefly distinguish moral realism from moral anti-realism before arguing that the strategy supererogationists have opted for may only be true under an antirealism framework. Finally, I will argue that this is unacceptable, as supererogationists are ultimately arguing about the nature of moral obligations—something they cannot truly do if there are no moral obligations.

Supererogation

One day, Sally decided to donate one of her kidneys. It was not donated to a family member or a close friend, but to a stranger. In fact, Sally never met the individual who received her ...

kidney, nor did she witness the stranger’s joyful reaction to being told that they may continue living. In judging Sally’s act, it seems that she has done something morally good. Indeed, Sally saved a life—something very good. However, if asked whether Sally was morally obligated to donate her kidney to a stranger, common intuitions seem to say ‘no.’ For if Sally was obligated to donate her kidney, then it is probable that I am obligated to donate my kidney, but that’s clearly an unreasonable demand, or so the thought goes. Thus, Sally’s act was supererogatory: good but optional.

It appears clear that Sally’s act was good, but it must be asked what, exactly, made her act optional. Due to examples like the above, it is tempting to suggest that it is an act’s incredible degree of goodness that makes it optional. Examples of supererogatory acts commonly include flashy episodes of heroism or saintliness, such as a soldier throwing herself on a live grenade to save her squad. However, it seems that most supererogatory acts are quite unexciting. For example, Elizabeth Harman offers an example of a college professor who may or may not review a student’s final essay the night before it is due. If the student fails, he will lose his scholarship and be forced to drop out of school. Harman claims that the professor is “not morally obligated” to give the student comments, yet it would be good to do so, making this act supererogatory. Additionally, Julia Driver asks us to imagine an individual who, in having first choice of train seats, decides to forfeit his spot so that a young couple may sit together. Her contention is that this individual would be “acting within his rights” if he remains in his seat, yet it would, once again, be good if he instead opted to sit elsewhere.

The notion that good acts may be optional has led to the “Paradox of Supererogation.” In essence, if an act is truly good, shouldn’t it be obligatory? As Daniel Muñoz writes, “If being the hero is really better, why isn’t it just obligatory?” It is important to stress the word

‘better,’ as it could be said that there are many good acts that are not obligatory in virtue of there being better acts that are obligatory. That is, if the better acts were not available to the individual, then the next best act would be obligatory, and so on. However, this is not what supererogation describes, as examples have been given of a lesser act being more obligatory than a better act (unless the better act is chosen). Thus, the Paradox of Supererogation assumes that better acts are more obligated, resulting in an obligation to always do our best.

Following this thought, Joe Horton’s “All or Nothing Problem” asks you to imagine that two children are in danger of being crushed by a crumbling building. You have three options: save one child and allow your arms to be crushed, save both children and allow your arms to be crushed, or do nothing. Supererogationists would suggest that saving both children at the expense of your arms is good but optional, while doing nothing is less good but permissible. However, if you let one child die, then you have seemingly chosen a less valuable outcome at no additional cost to your arms, which is forbidden. For supererogationists, this results in the odd conclusion that it would be preferable to let both children die than to save only one—all or nothing.

Of course, one could avoid the above issues by rejecting supererogationism and claiming that we are always obligated to do what’s best. However, as previously mentioned, this would seemingly imply that, given the chance, I would be obligated to donate my kidney, throw myself on a grenade, or allow my arms to be crushed. Surely, this would allow morality to be far too demanding. Thus, a good action may become optional if it is demanding enough, or so the thought goes.

There are two responses to the thought that morality could be too demanding; the latter of which will be saved for the second section’s discussion of moral realism. As for the former, a brief example will help. Take classical

utilitarianism, which I understand as the position that global happiness ought to be maximized. One could object to this view, as Robert Nozick did, by arguing that it fails to account for a just distribution of utility. Alternatively, Bernard Williams argues that classical utilitarianism is indifferent to matters of integrity, as it would require a peaceful chemist to take a position at a biological warfare laboratory with the thought that he may slow research progress. Thus, from the objections of Nozick and Williams, it may be incorrectly concluded that we are not, in fact, obligated to maximize the good.

I say ‘incorrectly,’ as the objections from Nozick and Williams imply no such thing. It is important to distinguish a moral theory’s structure from its content. A theory’s content makes claims about what sort of things are good (such as justice or happiness), but whether the good ought to be, say, maximized is a question of structure. Thus, while Nozick’s “Utility Monster” may highlight an inadequacy with classical utilitarianism, it merely shows that the good is more complex, not that it shouldn’t be maximized.

Supererogationists may argue that incredibly good acts, such as donating a kidney or saving two children can nevertheless be optional, as they involve threats to personal wellbeing (or some other good). But this response merely alters the content. One theory states that the good is high levels of global wellbeing, while the other states that the good is the preservation of personal rights. My concern is not with the content of ethics, but with the observation that changing the content does not change the fact that more of the good is better, whatever the good turns out to be. Additionally, when I say that more of the good is better, I am also assuming that what is better is also more obligatory. To say that I am morally obligated to donate my kidney is (roughly) to say that I have overriding moral reasons to do so. Thus, under my view, I always have moral reasons to do what is best.

In recent years, a common response to the above is to grant that we do have moral reasons to do what is morally best; although, moral reasons are not the only sort of reasons in play. James Dreier argues that, on the whole, we always have reasons to do what is most rational, but we do not always have reasons to do what is most moral: “The explanation for why it seems permissible for me to skip what is above and beyond the call of duty is that, although I do have some reason to rise to a saintly level, I have better (albeit nonmoral) reasons to do something else.” Authors have varying terms for moral and non-moral reasons. Horgan and Timmons, as well as Portmore, make a distinction between “requiring” and “justifying” reasons. In addition, Muñoz distinguishes moral reasons from “prerogatives” in a similar manner as Raz’s nonmoral “permissions.”

Regardless of what we choose to name them, the idea is that there are distinctly non-moral reasons that may override moral reasons. That is, if one has moral reasons to X, it is possible that one has non-moral reasons to not-X, where the non-moral reasons outweigh the moral reasons. Overall, this strategy does a few things. Firstly, it allows for the possibility that we are morally obligated to do our best. Secondly, it allows for that possibility while maintaining that our best can be non-morally optional. Thirdly, it accepts a form of reasons-pluralism. Finally, and most importantly, it denies that morality is overriding—non-moral reasons can defeat moral obligations.

In terms of the paradigm cases, non-moral reasons offer a compelling defense of options. While it may be agreed that donating one’s kidney would be morally better than not doing so, one could offer non-moral reasons, such as prudential reasons, to rationalize not undergoing the operation. Although, it is unclear to me how one type of reason could be demarcated from another. However, for the sake of this paper, ...

I will grant that there is a plurality of reasons. It is also unclear to me whether non-moral reasons would grant an option or simply another requirement. That is, if non-moral reasons dictate that one should not donate their kidney, wouldn’t this simply create another requirement, albeit of a different type? If so, no matter whether a kidney is donated, either a moral or non-moral obligation is broken. Regardless, my primary concern is with the claim that morality is not overriding, which I will turn to next.

Moral Anti-Realism

Before objecting to the supererogationist’s “non-moral reasons” strategy, it will be beneficial to contrast moral realism and anti-realism. At its most fundamental, I take moral realism to be the theory that there are some cognitive, true, and objective moral propositions. For a moral proposition to be cognitive, it must be either true or false. Oppositely, a non-cognitivist, such as Ayer, would claim that moral propositions lack truth values. Additionally, moral realism requires more than the mere possibility of truth values—some moral propositions must actually be true. If not, then error-theorists, such as Mackie, may claim that moral propositions are uniformly false. Finally, when I say that a moral proposition is objective, I mean that its truth or falsity is independent of beliefs, desires, evidence, theories, etc.

Earlier, I described the worry that, without supererogation, moral obligations would be far too demanding—I would be required to donate my kidney. My first response was that, while we still ought to do our best, it is unclear whether our best includes donating our kidneys. That is, the content of the good is independent of its structure. However, with the criteria of moral realism in mind, I can offer a stronger objection: even if the best act is incredibly demanding, it is still obligatory. For what makes an act demanding but my desire to not commit it? If moral realism is true, and moral facts are desire-independent, then I may not evade my obligations simply

because I feel as though they will be burdensome. As Elizabeth Pybus says, “We should not ask whether the action of throwing oneself on a grenade is beyond the call of duty, but whether actions of a certain sort, viz., very brave ones, are beyond the call of duty. And they are not. Clearly, we cannot slide out of doing our duty by saying that we are not brave enough.”

While the demandingness of morality does not solve the Paradox of Supererogation, supererogationists may still rely on non-moral reasons overriding moral reasons. This strategy is not in conflict with moral propositions being cognitive, true, and objective. One may argue that, if desires give us non-moral reasons that may override moral reasons, then moral reasons are not desire-independent and, thus, not objective. However, this misunderstands the supererogationist’s argument. It may be a desireindependent fact that morality demands that I donate my kidney. Nevertheless, morality’s demands may be beaten by non-moral reasons such that I, holistically, have more (or better) reasons to not donate my kidney. It is not, then, that moral obligations can be morally optional, but that moral obligations can be optional in the grand scheme of things.

My issue, then, is directly with the notion that moral reasons can be overridden—they cannot. Regarding moral reasons, a distinction is often made between reasons-internalism and reasonsexternalism. To summarize, the former suggests that our reasons for acting morally are found within the moral facts themselves, whereas the latter finds said reasons in some external source. My point is not in favor of one of these views in particular. I am not currently concerned with where moral reasons originate. More simply, I am claiming that no matter their origin, moral reasons create unsurpassable obligations.

Admittedly, I am unsure how one could object to the overridingness of morality. It would need to be shown that a pluralistic account of reasons is correct. This is entirely possible; however, it would also need to be shown how one type of

reason may override another. In particular, it would need to be shown how reasons for some non-moral end may override moral reasons. But this is the issue, as my conception of a moral obligation is categorical—it is that which I ought to do, period. If my conception is true, then it follows that morality cannot be overridden and the supererogationist’s strategy fails. After all, moral obligations cannot be optional if there are no moral obligations to begin with.

For those who disagree and argue that it makes conceptual sense to say that there can be better reasons to do what is practical than what is morally right, I can only think to say that we must be using the term ‘morality’ differently. Of course, my view of morality should not be taken for granted. If morality can be overridden, then supererogationism could be correct; although, I am worried that this view may fail to capture just how important and binding moral obligations are. Thus, I agree with the supererogationist that we are obligated to do what we have the most reason to do; however, I contend that we never have more reasons to do less than what is most moral.

In conclusion, I began by summarizing some foundational tensions within the concept of supererogation. I argued that, by separating the content of an ethical theory from its structure, it may not be the case that morality without supererogation is as demanding as one may think. Additionally, I argued that if one is a moral realist and believes that there are desire-independent moral facts, then it is not unreasonable for morality to be demanding. Finally, I argued that the supererogationist’s appeal to nonmoral reasons may commit them to a form of anti-realism in which moral obligations are not overriding and are, thus, far less important than might be thought. If supererogationism does, in fact, lead to anti-realism, then supererogationists have eliminated the very moral facts that they say are optional.

Bibliography

Ayer, A. J. Language, Truth, and Logic. New York: Dover Publications, 1952.

Dreier, James. “Why Ethical Satisficing Makes Sense and Rational Satisficing Doesn’t.” In Satisficing and Maximizing, edited by Michael Byron, 131-154. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004.

Driver, Julia. “The Suberogatory.” Australasian Journal of Philosophy 70, no. 3 (1992): 286-295.

Harman, Elizabeth. “Morally Permissible Moral Mistakes.” Ethics 126, no. 2 (2016): 366-393.

Horgan, Terry and Timmons, John. “Untying a Knot from the Inside Out: Reflections on the “Paradox” of Supererogation.” Social Philosophy and Policy 27, no. 2 (2010): 29-63.

Horton, Joe. “The All or Nothing Problem.” Journal of Philosophy 114, no. 2 (2017): 94-104.

Kagan, Shelly. “Defending Options.” Ethics 104, no. 2 (1994): 333-351.

Kamm, Frances M. “Supererogation and Obligation.” The Journal of Philosophy 82, no. 3 (1985): 118-138.

Liberto, Hallie Rose. “Denying the Suberogatory.” Philosophia 40, (2012): 395-402.

Mackie, J. L. Ethics: Inventing Right and Wrong. Harmondsworth: Penguin Books, 1977.

Muñoz, Daniel. “Three Paradoxes of Supererogation.” Nous 55, no. 3 (2021): 699-716.

Nozick, Robert. Anarchy, State, and Utopia. Oxford: Blackwell Publishers Ltd, 1974.

Portmore, Douglas. “Are Moral Reasons Morally Overriding?” Ethical Theory and Moral Practice 11, no. 4 (2008): 368-388.

Pybus, Elizabeth M. “Saints and Heroes.” Philosophy 57, no. 220 (1982): 193-199.

Raz, Joseph. “Permissions and Supererogation.” American Philosophical Quarterly 12, no. 2 (1975): 161-168.

Urmson, J. O., “Saints and Heroes.” In Essays in Moral Philosophy, edited by A. I. Melden, 198-216. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1958.

Williams, Bernard. “A Critique of Utilitarianism.” In Utilitarianism: For and Against, 77-150. New York: Cambridge University Press, 1973.

Need more to read? Here’s what our staff has been enjoying!