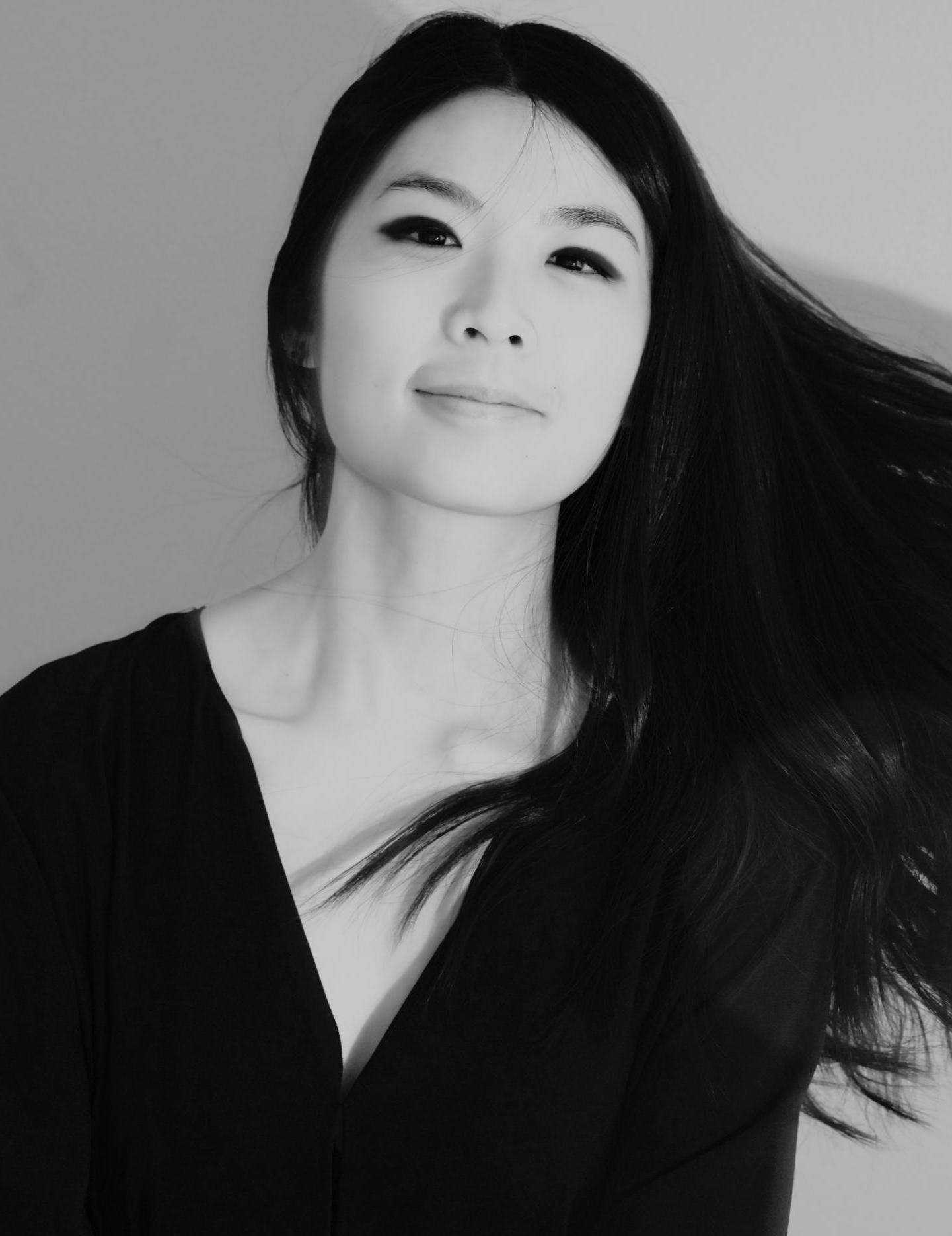

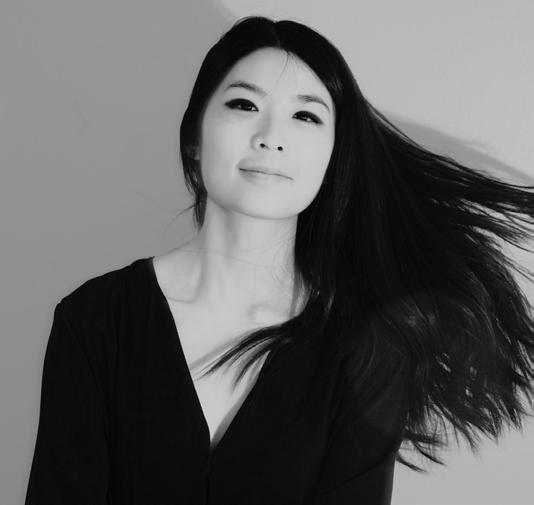

NOBUKO TODA ’03 AND KAZUMA JINNOUCHI ’02 ARE TOP SCORERS IN A BOOMING INDUSTRY

NOBUKO TODA ’03 AND KAZUMA JINNOUCHI ’02 ARE TOP SCORERS IN A BOOMING INDUSTRY

Metal Gear Solid and Halo composers

Nobuko Toda ’03 and Kazuma Jinnouchi ’02 talk about the paths to their careers and what it takes to level up in the video-game industry.

BY KIMBERLY ASHTON

The Mayan people of Mexico’s Yucatán Peninsula breathe new life into their ancient heritage, with help from a Berklee alum. BY

KIMBERLY ASHTON

Known for its rigor, Kuala Lumpur’s International College of Music has set up hundreds of students for success at Berklee over the past 25 years. BY REBECCA BEYER 32 KEY CHANGES

Its Rhythm

As evidence of music therapy’s benefits grows, the practice is increasingly showing up in hospitals, schools, and more. BY SUSAN GEDUTIS LINDSAY

Faculty Notes 43

INTERVALS Protecting Your Rights in the Digital Age 45 BY ALLEN BARGFREDE

‘Just Play’: The African-Infused Method Helps Students Learn Music Through Movement 47 BY KEVIN HARRIS

FACULTY PROFILE

George Howard 49 BY MICHAEL BLANDING

NEWS FROM OUR ALUMNI COMMUNITY

Alum Notes 54

ALUMNI PROFILES

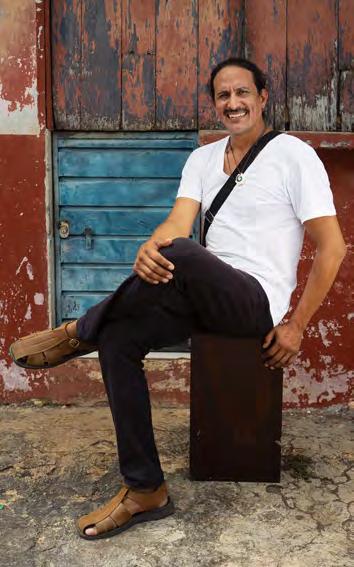

Dayramir González 55 BY NICK BALKIN

Dan Radin 57 BY JED GOTTLIEB

Kelly Buchanan 59 BY BRYAN PARYS

Final Cadence 62

Securing the Future of Music in Spanish BY JAVIER LIMÓN

On the cover: TK photographed by James Day. Opposite: Guido Tktktk photographed by Evangeline Gala

EDITORIAL DEPARTMENT

DIRECTOR

SENIOR COMMUNICATIONS MANAGER

COMMUNICATIONS MANAGER

PROOFING MANAGER

Berklee Today | Fall/Winter 2022 A PUBLICATION OF THE OFFICE OF EXTERNAL AFFAIRS

EDITORIAL DIRECTOR

CONTRIBUTING WRITERS

DESIGN

COPY EDITORS

CONTRIBUTING ARTISTS

Kimberly Ashton

Nick Balkin, Allen Bargfrede, Rebecca Beyer, Michael Blanding, Tori Donahue, Jed Gottlieb, Kevin Harris, Javier Limón, Susan Gedutis Lindsay, John Mirisola, Bryan Parys, Mark Small, Beverly Tryon

Patrick Mitchell, André Mora MODUSOP.NET

Diane Owens Lauren Horwitz

Kelly Davidson, James Day, Evangeline Gala, John Huet, Oriol Vidal, Mark Weaver

Nick Balkin

Bryan Parys

John Mirisola

Lesley O’Connell

OFFICE OF INSTITUTIONAL ADVANCEMENT

SENIOR VICE PRESIDENT OF INSTITUTIONAL ADVANCEMENT

INTERIM SENIOR DIRECTOR, BERKLEE ALUMNI AFFAIRS

ASSOCIATE DIRECTOR OF ALUMNI AFFAIRS/LOS ANGELES

ASSISTANT VICE PRESIDENT FOR INSTITUTIONAL ADVANCEMENT

SENIOR MANGING DIRECTOR, INSTITUTIONAL ADVANCEMENT SPECIAL PROJECTS

Erin Tunnicliffe

Joseph Dreeszen

Dana M. James B.M. ’09

Beverly Tryon ’82

Virginia Fordham B.M. ’80

As the alumni-oriented magazine of Berklee College of Music, Berklee Today is dedicated to informing, enriching, and serving the extended Berklee community. By sharing information about college matters, music industry issues and events, alumni activities and accomplishments, and musical topics of interest, Berklee Today serves as a valuable forum for our family throughout the world and a source of commentary on contemporary music. Berklee Today (ISSN 1052-3839) is published twice a year by Berklee College of Music’s Office of External Affairs. All contents © 2022 by Berklee College of Music.

Send all address changes, press releases, letters to the editor, and advertising inquiries to Berklee Today, Berklee College of Music, 1140 Boylston St., Boston, MA 02215-3693, +1 617-747-2843, kashton@berklee.edu. Alumni are invited to send in details of activities suitable for coverage. Unsolicited submissions are accepted. Alum Notes may be submitted to berklee.edu/alumni/forms/alumni-updates. Visit us at berklee.edu/berklee-today.

in its latest Global Music Report, the trade group IFPI says that the international music industry grew more than 18 percent last year, bringing in almost $26 billion. The Motion Picture Association, the group representing the movies, says its industry grossed nearly $100 billion, about the same as it did before the pandemic.

As large as these figures may seem, they are dwarfed by what the video game industry raked in last year: $193 billion worldwide, according to the Gaming Industry Survey report by Ernst & Young Global Limited (EY).

“It’s breathtaking to witness the pace with which the video game industry is evolving, especially with all the new forms of extended reality,” says Esin Aydingoz, the assistant chair of Berklee’s Screen Scoring Department, formerly known as the Film Scoring Department.

In fact, the department created a new major—game and interactive media scoring—in response to this changing media landscape, says Sean McMahon, the department’s chair. “By all indications, video games are the future of media. The video game industry continues to expand rapidly, all over the world, and it’s having a huge influence on the movie and music industries.”

And the pace of growth is likely to pick up as virtual-reality technology advances. Game scorer Nobuko Toda ’03, featured on this issue’s cover along with her professional partner Kazuma Jinnouchi ’02, says that she is seeing the technology open up more and more audio possibilities for these 3D environments, and the industry is following (p. 12).

I caught up with the pair, over Zoom, while they were in Tokyo, just before leaving for London to score their next big project at Abbey Road Studios. In addition to talking about industry trends, we discussed their music backgrounds, how to score a franchise game, and advice they’d give to aspiring video game composers.

Also in these pages, I visit Guido Arcella M.M. ’15—who graduated from Berklee Valencia’s scoring for film, television, and video games program— to talk about the nonprofits he cofounded that help young Mayan people in Mexico’s Yucatán Peninsula hold on to their heritage through music.

This issue also examines the remarkable changes in the music therapy business over the past 10 years; pays tribute to Vice President for Academic Affairs/Vice Provost Jay Kennedy, who is retiring after 28 years at the college; takes a look at Berklee’s partner school in Malaysia; and more. I hope you enjoy these stories as I have.

STUDENT CHARLEY TIERNAN, WHO PERFORMS AS CHARLEY, SINGS AT THE INSTITUTE OF CONTEMPORARY ART ON AUGUST 25 AS PART OF BERKLEE’S SUMMER IN THE CITY CONCERT SERIES.

BY TORI DONAHUE AND KIMBERLY ASHTON

In the spring of 2012, Berklee launched its first global studies program in Valencia, Spain, at the vibrant City of Arts and Sciences. Now known as Berklee Study Abroad, this program opened the doors to Boston undergraduates seeking to expand their horizons by spending a semester away from the main campus, and it marked the inception of Berklee’s Valencia campus.

That fall, master’s degree students came to Valencia for the college’s first graduate programs: global entertainment and music business; contemporary studio performance (later named contemporary performance [production concentration]); and scoring for film, television, and

video games. In the fall of 2013, the music technology innovation program, known now as music, production, technology, and innovation, was added.

Following the merger of the college and Boston Conservatory, Berklee Valencia launched its first opera program, the Boston Conservatory Opera Intensive at Valencia, during the summer of 2017. And in the fall of that year, Berklee began a program that allowed firstyear students the opportunity to begin their experience in Valencia.

Now in its 10th year, Berklee Valencia has welcomed more than 4,000 students from 85 countries and has awarded over $10 million in scholarships.

The past decade was only the beginning. In 2020,

Berklee and the government of Valencia signed a renovation agreement that allows the campus to stay in the City of Arts and Sciences for an additional 40 years. “Knowing that we have a secure home in Valencia for the coming decades, in a space as incredible as the City of Arts and Sciences, lends stability to our campus and allows us to start building new programs and initiatives,” says Simone Pilon, Berklee Valencia’s dean of academic affairs.

The agreement includes a provision in which Valencian students who have been admitted to one of the master’s degree programs are eligible to receive a scholarship to attend Berklee Valencia.

It also allows Berklee to expand its footprint in the

City of Arts and Sciences by 25 percent. María Martínez Iturriaga, the executive director of Berklee Valencia, says the increase in space will allow for the addition of study and meeting rooms for students; a small stage for open mics; a 100-person event and performance room; a music production suite; two large classrooms; a larger DJ lab; and more. Berklee aims to start renovations this spring and plans to have them completed by spring 2025.

“Berklee Valencia has great potential in terms of leveraging its geographic presence in Europe and the Mediterranean,” Martínez Iturriaga says. “We aspire to serve as a bridge between these cultures and the rest of the world, as well as continuing being a catalyst for innovation and creativity.”

BY BEVERLY TRYON

On October 1, guests gathered at Boston’s Westin Copley Place for the 28th Berklee Encore Gala benefitting Berklee City Music.

Following a cocktail reception, they were treated to bluegrass, jazz, rock, and world music performances by student, faculty, and alumni musicians, who played both during the dinner and afterward in nightclub settings. Musical acts included the Berklee Indian Ensemble, Eguie Castrillo Salsa Orchestra, Radius, Studio Two, the Berklee City Music Ensemble, Nebulous, and Soil 4 Soul.

The event also featured special guest artists MOLLY TUTTLE and Golden Highway. Tuttle '14 is the first female artist to win the International Bluegrass Association’s Guitar Player of the Year award. The night ended on a high note with a dance party featuring

the Family Stone singing hits such as “Dance to the Music” and “Everyday People.”

As part of a live auction experience, guests bid on a private dinner package with Red Sox legend and recent Baseball Hall of Fame inductee David Ortiz, along with VIP tickets to see CHARLIE PUTH B.M. ’13 perform in Boston.

The event raised $1.4 million to provide critical scholarship assistance to deserving young students. For 29 years, City Music has enabled young musicians marginalized by socioeconomic barriers to fulfill their artistic, academic, and personal potential through the study of music. City Music reaches hundreds of thousands of young people through City Music Boston and 46 partner organizations in 40 cities across the U.S., Canada, and Latin America.

Special Thanks to Our Encore Gala Sponsors

Copresenting Sponsors

Abrams Capital

Bain Capital Community Partnership

Colead Sponsors

Aramark Education

Boston Celtics Shamrock Foundation

Bill and Kelly Kaiser

Martin and Tristin Mannion

Main Ballroom Sponsors

Sandhya S. and Craig S. Douglas

Lynch & Associates

Miky Lee

New Balance Foundation

PEPSICO

Gregory Annenberg Weingarten, GRoW@Annenberg

Andrew and Mariann Youniss

Event Cochairs

Sandhya S. and Craig S. Douglas

Bill and Kelly Kaiser

Performance

EVENT: 2022 Commencement Concert

DATE: Friday, May 6, 2022

LOCATION: Agganis Arena, Boston

DETAILS: Spoken-word artist Ljuliana Giselle Thomas, from Memphis, Tennessee, performs Stevie Wonder’s “Jesus Children.”

BY JOHN MIRISOLA

The road to the Berklee Indian Ensemble’s first album, Shuruaat (Hindi for “beginning”), might have seemed improbable. What began as a small academic ensemble over 10 years ago has evolved into a YouTube phenomenon with close to 300 million views and an international music distribution deal. But hearing how skillfully the ensemble flows through styles, balancing immense talent with serious fun, it’s no surprise that the group managed to arrive at this new achievement.

“The main thing that has always driven us are two questions: what if? and why not?” the ensemble’s leader, Berklee India Exchange Artistic Direc-

tor Annette Philip, says. “Just because it might be hard is not a good enough reason to not do this, or not even try.”

Featuring 98 musicians from 39 countries, and collaborations with legends including ZAKIR HUSSAIN ’19H, Shankar Mahadevan, Vijay Prakash, and Shreya Ghoshal, Shuruaat assembles 10 of the group’s most memorable performances into a cohesive musical journey. “It really is a full spectrum of what the ensemble has created as a team, as a family, over the last 10 years,” says Philip.

Out this summer, the album also marks a milestone in ethical music business practices. “We have set up Berklee’s first—and probably one of the

world’s first—equitable, just revenue-sharing systems,” Philip explains, adding that everyone who is part of the album receives a prorated revenue share for life. “We want our students and our alumni to know that they have rights, and they have to be treated correctly, no matter who their collaborator is.”

Ultimately, these thoughtful business practices are of a piece with the overarching messages of positivity and unity at the core of Shuruaat. “The music we create is first and foremost to share joy,” says Philip. “We want to remind people...that there is so much good in the world and so many well-meaning people in the world.”

It’s Joni’s World, We’re Just Living In It

Berklee awarded Joni Mitchell an honorary doctorate on August 23 in recognition of her incalculable contribution to music. Known for her complex harmonies and soul-baring lyrics, Mitchell helped shape the sound of not just her own generation but of those to come.

“Well, luckily I’m too old to get a swelled head,” Mitchell said of receiving the honor. “It’s a beautiful event. Words can’t describe it. I’ve got my good friends here with me,” she added. WAYNE SHORTER ’99 and HERBIE HANCOCK ’86H sat next to her during the private ceremony in Los Angeles.

Throughout her six-decade career, Mitchell has turned out a long list of achievements. Last year, she was given a Kennedy Center Honor for her contribution to American culture; this year, the MusiCares Foundation named her its Person of the Year. She’s won four Juno Awards and nine Grammys (and has been nominated for seven others). In 2002, the Recording Academy gave her its Lifetime Achievement Award.

KIMBERLY ASHTON

BY KIMBERLY ASHTON

NOTE: THIS STORY CONTAINS SPOILERS.

After HBO’s blockbuster success Game of Thrones aired its final episode in 2019, the network looked into several spinoff ideas before landing on what would become the franchise’s follow-up, House of the Dragon. The show, a prequel, had to assert its own identity while also maintaining a continuity to the original series. Part of what kept the link strong between the two shows was the decision to have RAMIN DJAWADI B.M. ’98, who scored Game of Thrones (GOT) and composed its famous theme song, write the music for House of the Dragon (HotD). Below, Djawadi talks about how he created a musical world unique to HotD while staying true to the

broader GOT soundscape.

House of the Dragon kept the original Game of Thrones theme song for its opening sequence. Could you talk a bit about the decision to do this rather than to give House of the Dragon its own theme?

The original GOT theme was created as an overarching theme for the entire show, a theme that represents the journey of all the characters and plots of the vast story that George R.R. Martin has created. We wanted to connect HotD to the original series with the same main theme.

House of the Dragon is set 200 years before Game of Thrones. How did you reflect this in your music?

We wanted to connect the music to the original series by having familiar sounds and themes, but the majority of the material is new. The cello is still the primary instrument and there are familiar themes like the king’s theme or the dragon/Targaryen theme, but most of the themes are new. We needed to create new themes for all the different new houses and also have dedicated themes within the Targaryen family for Rhaenyra, Daemon, etc. There are some sonic differences in the HotD score that do not exist in the original GOT score. When woodwinds or solo vocals are used, it is with the intent that certain instruments can be heard in HotD, but are then less common [or] not used anymore 200 years later.

In Game of Thrones, you used certain instruments for various characters or storylines. Do you have any instruments you favor for House of the Dragon characters?

We certainly continued that approach. The Velaryons have bamboo flutes and percussion that distinguishes them as world travelers. The Targaryens have

the same sonic sound that we know from GOT, but new additional themes. The silent sisters have a choral texture, etc.

Are there any (other) specific allusions to GOT embedded in the music for House of the Dragon?

The main title theme gets hinted at quite a few times in more abstract ways when Viserys talks about his dream. [It’s] a nice opportunity to connect to GOT and foreshadow what’s to come with viewers that are familiar with the original show.

What’s been your favorite scene to write music for so far in House of the Dragon? What’s been the most challenging scene to score?

There are many beautiful scenes I could mention from each episode. The final scene in [the first episode], which made us decide to use piano right away. Daemon’s surrender in [the third episode]. Alicent’s entry during the wedding in [the fifth episode]. The funeral scenes are challenging; they are so emotional.

STORY BY Kimberly Ashton

METAL GEAR SOLID AND HALO COMPOSERS NOBUKO TODA ’03 AND KAZUMA JINNOUCHI ’02 TALK ABOUT THE PATHS TO THEIR CAREERS AND WHAT IT TAKES TO LEVEL UP IN THE VIDEO GAME INDUSTRY. it looked really cool…I made the request again: “Hey, if it’s flute can I go take lessons?” and then they said yes.

In 2006, NOBUKO TODA ’03 was working on the music for the fourth installment of the blockbuster video game franchise Metal Gear Solid when she called her former classmate Kazuma Jinnouchi to ask him to help her score the project.

KAZUMA JINNOUCHI ’02, who at the time was an arranger and indie pop-rock guitarist gigging around Tokyo, hadn’t done any professional work as a film scorer. Moreover, years prior, as a new student at Berklee, he had dropped any nascent idea he had harbored of pursuing film scoring after feeling overwhelmed by an introductory class. Sure he wasn’t up to the task, Jinnouchi declined Toda’s offer.

But Toda knew what Jinnouchi could bring to the project. As students, the two often found themselves in the same classes and would listen to each other’s music and give feedback. After graduation, they stayed in touch and would occasionally work together.

music programmer on Halo 4, and brought in Toda, who was a freelancer, as an orchestrator and score producer.

For the next release in the franchise, Halo 5: Guardians, Jinnouchi was the composer, and Toda was the game’s orchestrator and executive music producer. That game was the biggest Halo launch at the time, bringing in over $400 million in sales in its first week. (For comparison, the highest-grossing movie in history, 2009’s Avatar, had an opening week of $137 million.)

In addition to knowing the quality of Jinnouchi’s musical ideas, Toda knew that he was capable of working long hours in a demanding production environment, which is just what she needed in a collaborator on Metal Gear Solid 4: Guns of the Patriots.

“All the orchestral things I could just teach him afterward,” Toda said during a recent interview from Tokyo.

Swayed by his friend’s insistence, Jinnouchi went through the demo process at Konami Digital Entertainment, makers of Metal Gear Solid, and got the job. The only thing left to do was to learn how to score a game. “All these scoring things were so new to me, so Nobuko pretty much taught me how to write to the visual,” Jinnouchi said.

The game was a hit, and the two continued to work together for the next five years as in-house composers at Konami subsidiary Kojima Productions. In 2011, Jinnouchi left the company to join the team making the latest Halo game, one of the industry’s most famous franchises, at Microsoft’s 343 Industries. A member of the in-house audio team, Jinnouchi served as an additional composer, music editor, music director, and

Jinnouchi left Microsoft in 2018. Today, he and Toda work as freelancers, and have collaborated on Marvel’s Iron Man VR and many animated series, such as Ultraman, Ghost in the Shell SAC_2045, and Star Wars: Visions . They’re currently working on a Japanese animated film as well as a major superhero franchise video game, due out in 2024. During a busy August that found one or both of them in Tokyo, London, Prague, Kuala Lumpur, or Seattle, Toda and Jinnouchi dialed into a video call to talk about their music backgrounds, scoring a franchise game, trends in video game music, advice they’d give to aspiring video game composers, what they listen to when they drive, and more. Jinnouchi, who’s lived in Seattle for 11 years, provided some translation for Toda, who’s been primarily based in Tokyo. The interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Tell me about your early experiences with music. How old were you when you began playing instruments?

KAZUMA JINNOUCHI: This goes back to elementary school, but I originally wanted to start taking piano lessons just because I was fascinated by the instrument by watching my teacher play. I was really small at the time…so my parents didn’t know if I would continue to be interested in that kind of musical instrument, so that request got rejected. Later, when I was in the third grade, I was looking at this picture of the flute. I think it was in the newspaper. And I thought

NOBUKO TODA: I grew up in a very poor family. My father reduced his own allowance so that I could learn to play the piano and organ. When I started attending classes, my father picked up a small foot-pedal organ from somewhere and I played it every day. I had an electronic organ and the piano. I don’t exactly remember how I started playing those instruments, but my mother told me that when I was very young I pointed out a picture of an electric organ in the newspaper and said I wanted to play it. I started playing for fun. I also would read picture books and then write original music to the book. I really liked to make storybooks too. For quite a while I was self-taught on the instrument. The same for composition, for writing music. But when I wanted to enter a competition for electric organ performance, the requirement was also to perform my own music so I was writing for that every year.

How old were you then?

NT: From middle school to high school, so from around 11 or 12 to 16 or 17. My dream was to be a performer who toured abroad.

Kazuma, what was your involvement in music at that age?

KJ: I was continuing to take my flute lessons throughout the rest of my elementary school and middle school years, and then I started getting into coding, [into] programming things, because all my friends were playing video games on the Nintendo system and I had asked my dad if he would get me a Nintendo system for Christmas, and the answer was no.

But he was interested in computers and bought a computer, and showed me how to program things. He told me, “Hey, if you want to play a game, you can make your own.” I wasn’t very good at it but it was a lot of fun. At a certain point, I was comparing my program, which somewhat looked like a video game, to the Nintendo games… and one thing that came to my mind was, “Oh, my game doesn’t have any music in it. I need to start composing music.” So I

“NOBUKO AND I WERE BOTH FORTUNATE ENOUGH TO GO THROUGH BIG STUDIOS THAT RELEASE GAMES WORLDWIDE, AND [FOR WHICH] THERE HAS TO BE ACHIEVED A CERTAIN LEVEL OF SUCCESS. THERE’S AN EXPECTATION OF THE QUALITY THAT WE NEED TO HIT,” SAYS KAZUMA JINNOUCHI.

INSET, OPPOSITE: TODA AND JINNOUCHI AT WORK AT ANGEL STUDIOS IN LONDON.

got the sound module, like one of the early hardware midi modules in the mid-’90s. I installed the sequencer on my pc and then started playing notes. But I couldn’t play keyboard at the time, so I was playing flute and then coming up with a melody and just entering notes one by one.

I started thinking, “Oh, I need to learn how to write harmony.” I was already 16 years old, and I knew it was pretty late to start playing piano…but a lot of friends were starting to play guitar. I thought, “Oh, if they’re starting to play an instrument now maybe I can catch up.” So I got my acoustic guitar, and the way I composed was playing a flute and coming up with a melody, and then playing guitar on top of it to come up with a chord, and I was just sequencing those one note at a time.

Did you want to major in film scoring when you entered Berklee?

KJ: So initially I wanted to go for a film scoring major because when I was in high school [during a year abroad] in the U.S., one of the classes I took was a music tech class. My teacher gave me a Three Stooges [clip]. We had to write music for it. It was a lot of fun doing it.

But when I first took the intro to film scoring class [at Berklee], I sort of realized that the major was built for someone who can already write music, and I was still struggling to write a proper harmony. I thought that was way too advanced for me.

My father told me, before going to Berklee, that I can go to whatever school [I want] but that should be the only school [I go to] because [my parents] won’t support me financially beyond that. So I was thinking in a very practical manner: “Okay, if I go out in the professional world I probably want to be in a studio environment and do the writing. And I need to be able to write in lots of different instrumentation”…so I decided that the contemporary writing and production [major] matched my requirements pretty well.

[Also,] after the first day at Berklee, going through auditions and getting shocked by all these talented students, my mind when I chose the major was, “Okay, if I can make a living in this world, I’m okay with really anything.”

Nobuko, what was your plan when you entered Berklee?

NT: I had applied for a scholarship at Berklee and was asked to go through an interview. I came to Boston for that, and at the hotel where I was staying there was a group of Japanese people who came to see a JOHN WILLIAMS ’80H concert. I got to know this Japanese group and went to the John Williams concert all three days that John Williams was in Boston. I was very moved by that concert and wanted to say thank you to John Williams, so I went back to the hotel and wrote a composition on a piece of paper. The piece was called “For John Williams.” I put some wrapping ribbon on the score sheet and wanted to hand the music [to Williams] in person, but he happened to not come out the back door that day, so I handed it to the security guard.

I went back to the hotel and was getting ready for the interview at Berklee when the phone rang in my room. I wouldn’t know anybody in Boston, so I didn’t pick up. But the phone rang again and then I picked it up, and on the other end of the line was John Williams.

I got really excited so I don’t remember much of what I said, but I remember that John Williams gave me a compliment on my composition and invited me to his Tanglewood concert and told me where he is staying. I wrote a letter and brought it [his] hotel. Since then we’ve been exchanging mail.

Until I met him, I had only hoped to enter the Film Scoring Department and write one piece of music that could be played in an orchestra, but from that day on I became more eager to learn film music in earnest.

Wow, not everybody is nudged to go into film scoring by John Williams. So when did the interest in video game scoring develop?

NT: After graduation the plan was to go back to Japan, and in order for me to be able to start living in Japan I had to find a job. One of the job postings I saw was from the video game company Konami for an in-house composer’s position at the former studio called Kojima Productions.

I met the director in the interview, Hideo

“I was getting ready for the interview at Berklee when the phone rang in my room. I wouldn’t know anybody in Boston, so I didn’t pick up. But the phone rang again and then I picked it up, and on the other end of the line was John Williams.”

NOBUKO TODA ’03

Kojima, the famous game director, and he told me that the game they’re working on [Metal Gear Solid] is very cinematic and they were looking for a film-scoring capable composer who can contribute to close to eight hours of cinematic music. He asked me, “Do you usually play games?” I said, ”I don’t.” [Then he asked,] “Do you know Metal Gear Solid?” I said, “No.” Kojima and I talked about our favorite movies for about 30 minutes. Then he got up and said, “I’ll be waiting for you” and walked away. I was surprised that I was hired.

And then you brought in Kazuma. Tell me, how do you typically work together?

KJ: Well, it really depends on the kind of projects because our writing style is very different. So, for example, the recent project that we did, which was Disney+ Star Wars: Visions…Nobuko would do more of emotional character themes and then I would do more action-oriented cues. And then on other occasions where we will be doing electronic-heavy scores, Nobuko will be more functioning as a music director, producer, music editor, and production coordinator, and I will be doing a lot of synthesis work. So it really depends on the requirements of the project. It’s really never the same.

NT: We’re very different writers. I’m more orchestral and then Kazuma is more on the electronic [side].

KJ: I mean, we’re both orchestral and electronic, but I lean more towards electronic and the production side of things, and her strength is more on the direction and producing and based on the impression she gets from the project.

Can you tell me a little bit about your process for starting a new project? How do you typically approach it?

NT: Usually we are given opportunities to hear from the director about the vision of the project, which can be a pretty lengthy conversation, but we get to know the project, its basic concept, or the general feel or concept of what the story is about. And then we go back and discuss how we can approach it musically. Sometimes that involves

some demoing between the two of us. And then we iterate on a musical concept until we have something thematic. Sometimes we come up with one, and sometimes it’s 20. And then we present.

KJ: So, in a project like Halo, how the music was approached was that video game story details are developed simultaneously. When you jump into the project pretty early on, sometimes all you get is a one-pager document of “Hey, Chapter One, this happens; Chapter Two, things go sideways,” and things like that. It’s a very vague description of what happens. In those kinds of situations, we work on what we call the suite. It’s a collection of long musical pieces that have lots of different musical elements that represent either the whole story or each chapter. And then that sort of becomes the concept of each scene…and then we present that to the art department or narrative department in the hopes that they get inspired by us.

Does the game ever change based on the music that you write?

KJ: I’d like to think that that happened before. I think there are a few conversations where [someone said], “Oh hey, I like your music and I added a little detail based on what you wrote.” It’s a very collaborative process. Sometimes a few people came back to me and with lots of enthusiasm and [said], “Hey, I listened to your piece, and we were thinking about this,” and “Hey, can you add this kind of musical element to this?” That kind of going back and forth really unifies the tone.

And then, with Halo you’re also inheriting a franchise, so how do you keep the same DNA of the music that its former composer, Marty O’Donnell, wrote and bring that into your iteration of the game?

KJ: Well, in the case of the Halo projects, that’s where the Berklee harmony study really came in handy. Marty was incorporating a very unique harmony approach and some [unique] phrasing as well. But it’s really not the specific sequence of notes that you need to hit; it’s really the feel that you need to get right. So even if you’re writing your own

chord progression, it still needs to feel like it’s part of the Halo franchise. So I would go back and analyze his piece, and…all the harmonic technique was analyzed and incorporated and sometimes altered. And, of course, the melodic content needs to be present as well, and it needs to be present in the right context. If you mess up what’s happening in the background of the melody, it feels wrong, so you kind of need to understand the musical language that Marty was using and then make your own.

That’s an interesting way to think about it. It’s as though you’re using the same language but you’re saying something different with that language.

KJ: My view is that I had to learn his language first and then be able to [tell] my own [story] in that language, because the story is evolving. We’re not repeating the story so we can’t be just repeating, “Hey, I copied Marty’s piece; doesn’t it sound like Halo?” In order for the new content to make sense, storywise, we have to come up with our own voice. So I’d say 60 to 70 percent of the musical dna comes from the previous game, but the remaining 40 percent or 30 percent, that’s an opportunity for your own voice. And music placement is also really important. It needs to be placed in the right moment in order for the game to sound like Halo.

Berklee is expanding its video game scoring offerings and the Screen Scoring Department is introducing a new major, so I wanted to talk a little bit about the video game industry. What excites you about scoring games today, and what do you see happening in the video game scoring world that wasn’t happening 10 years ago?

KJ: Compared to when we started, I think there’s a lot more creative freedom because of the advancement of the toolset. Back when we started at Konami, it was all command-line tools that we had to be familiar with to get the music playing in the game, and now it’s almost like daws like Ableton Live. You can visually program music, and that’s really exciting.

NT: At the same time, with the ability of making music interactive, some of the beauty we had back in the old days—just the linear music playing over and over, which became very memorable—doesn’t really happen anymore.

KJ: The implementation of the music used to be a lot more simple back in the old days. You would have a single wav file just looping over and over, whereas today you have all these individual chunks of music where you can let the program decide what to play so it really matches your gameplay, but musically it’s sometimes more difficult to make it memorable.

And what are some trends in the industry that you see growing over the next several years?

NT: The 3D audio, the immersive audio experience, that’s becoming more and more capable. In vr we are already working in more than stereo even though we only have a stereo environment, but we are heavily looking into immersive three-dimensional audio space. We are assuming that the kind of tech aspect of change will be happening more and, in fact, in the production we are in right now, we are exploring that [3D audio]. The tools are always advancing.

But that’s definitely the area we can explore. Because of the interactivity, there is no reason that we shouldn’t be placing music content in the speakers other than stereo. And so it really needs to be worked together with the game design and level design.

KJ: I would like to think it’s going to be less hectic to get music into the game, and less process to achieve better results, but you never know. That’s kind of my hope.

NT: Also, I see more potential in the mobile environment because of how handy the device is. One of the biggest companies in Japan is mobile-based. Their fan base is 100 percent mobile, and so having seen that I see more potential in those platforms.

How does scoring for VR differ from scoring something like Metal Gear Solid?

KJ: Well, it’s really the point of view. I do find

vr to be somewhat similar to a first-person shooter game, because you kind of have the same viewpoint. What you’re seeing is the character’s viewpoint.

This is just my way of approaching music for this kind of video game, but where possible I tend to back off musically, or not use music at all…not overload it with musical content, because you really need to experience the environment so when you come to the climax, that’s when you have really big, strong themes. That kind of contrast is really effective in the game. But if you’re working on games like Metal Gear Solid, you are watching the character and you’re an observer, so you sort of experience whatever the action is from a very different point of view. From my experience, you have a bit more room for musical expression if you’re observing the character.

Another thing to consider in the first-person experience is that the sound effects are pretty loud, so you need to watch out for it and you don’t want to fight with the other sounds. I mean, this really applies to anything with sound effects. This is something Nobuko taught me over the years: You see an explosion and you know there will be tons of sounds, so why do you need to have tons of instruments here? You can just back off a little bit and make room for it.

How do you see music evolving in the video game world? Are you starting to see new musical influences in video games?

KJ: I think the door will be more open to many different genres. Whatever fits the game. There’s no “Hey, [there are] lots of orchestral soundtracks, we should do this as well.” I feel that studios and audiences are really open to any kind of musical style.

A lot of Seattle-based composer friends of mine are very diverse, and the people that I do know personally are very musically diverse; some people work on electropop game scores then some people just work on orchestral things, and some people are doing jazz scores.

NT: One of the trends I’m sensing happening in Japan is that a lot of audiences are going away from traditional orchestral sounds and [toward] more heavily produced electronic

“I think the door will be more open to many different genres. Whatever fits the game.... Studios and audiences are really open to any kind of musical style.”

KAZUMA JINNOUCHI ’02

elements. Some people don’t even really like organic elements. I mean, probably from a u.s. point of view that might be a very niche thing, but that’s definitely one area of musical interest. Also, music that doesn’t really incorporate melody in a traditional sense is already happening in a lot of different mediums as well.

Geographically, where do you see the industry growing most?

KJ: I don’t really know the answer to your question, but just speaking of the West Coast there are a lot more indie studios than 10 years ago. For example, a lot of my ex-colleagues at Microsoft left big corporate and started their own [studios]. And there’s multiple of those in Seattle. I see more small studios doing interesting things.

NT: I have experience working with Singapore-based studios that have huge fan bases as well. And there are a few companies in Tokyo, relatively new companies, that managed to get very big fan bases.

What advice do you have for someone who wants to get into this industry, or what do you think a video game scorer today needs to have to succeed in the industry?

KJ: I can talk a bit more on the technical side of things, but this also applies to working on film. The content is built on the technology so understanding the workflow, terminology, and language that’s used in the production would be definitely helpful. Again, that continues to change because of just the nature of the industry; it just continues to evolve, so I think that being able to adapt to new technology and ways of composing music [is important]. And then, of course, being able to write good music is important. But, yeah, just understanding the medium, and then, especially for video games, if you really understand it, it really helps you write more functional and more effective scores.

And then getting to know who works on what games [is important]. Luckily for video games, there are lots of conferences and

people usually like to talk to people. And so getting to know the developer and understanding what their requirements are, and letting people know what you’re up to and what you want to do, is really important.

NT: [My advice is] to be an in-house composer.

KJ: Yes.

NT: When you work on a video game, from the director and designer side, you are part of the development team. Of course, you’re the composer and you’re part of the music, but before that you are part of the development team, so just really understanding where you stand compared to other people who make the game is really important.

KJ: We both learned that way of working by being in-house for many years, and so we know what it’s like to be in crunch time in the studio and trying to finish a game in a shippable quality. It may be hard to get a sense of what that’s like from the outside, but being part of the development team really means that you understand the process.

I forgot who gave me this advice, but someone early in my career said, “If you get to become an in-house composer, make sure you go through more than two companies; that way you learn different cultures and how different companies ship the game,” and that was very true.

Nobuko and I were both fortunate enough to go through big studios that release games worldwide, and [for which] there has to be achieved a certain level of success. There’s an expectation of the quality that we need to hit. At the same time, in a pinch, [we need to know] what needs to be a priority during the development and what needs to be cut off.

Does working in film and TV help you with your vidzeo game scores?

KJ: I think so. There are elements that don’t really apply in film that you learn in games and vice versa, but I think creatively it really helps. And more than just going between different mediums is working with different directors. They all have different methods of conveying the message, so knowing differ-

ent approaches and then being able to have those options creatively as a writer and producer is really helpful.

NT: I, on the contrary, feel that my experience in game music composition [helps] when composing music for film and television. Because the story is consistent, it is easier to psychologically manipulate the music, to place musical features…. Above all, we don’t have to create music that has 10 branches in one story. [laughs]

What do you like to listen to when you’re not working?

NT: I don’t want to listen to anything. I like silence. Whatever musical ideas I have in my head, I don’t want to be distracted [from them] by listening to some other music.

Do you ever listen to music?

NT: Only when I drive my car. The music provides me with a certain level of distraction so that I don’t get very tense.

What about you, Kazuma? What kind of music do you like to listen to in your free time?

KJ: I recently went back to listening to Vince Mendoza. He’s a really amazing arranger. I first bought his cd when I was at Berklee and was blown away with his writing. I listened to his album again recently and I keep going back to it; it’s just so inspiring. A couple months ago I was listening to a Japanese big band writer named Miho Hazama. She’s an amazing writer. I was listening to her album and it’s really great.

I listen to music on my own sometimes in the studio just to distract me from whatever I’m writing so that I can listen to my music with a fresh ear. I don’t really listen to music when I drive because it becomes a little distracting and dangerous for me. I start following the harmony, and I tend to miss a few things when I drive if I do that, so I thought that was a little dangerous.

NT: When I listen to orchestra when I drive, the same thing happens. It just gets [to be] too much—I would go the wrong way. [Laughs.]

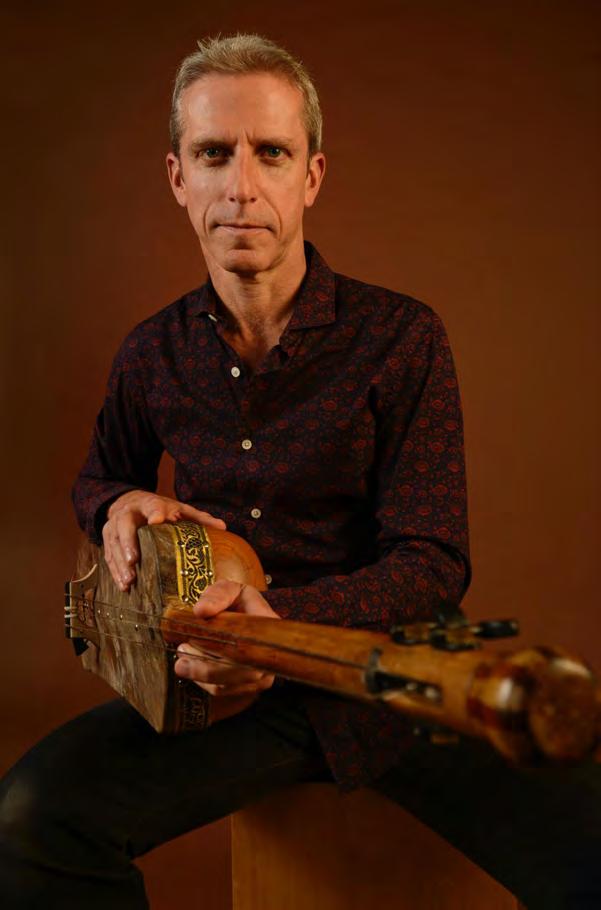

“BARRIO MAYA AND MÚUL PAAX ARE TRYING TO SPREAD THE MESSAGE THAT, ‘HEY IF WE DON’T DO SOMETHING, A HUGE PART OF OUR CULTURE IS GOING TO BE LOST: OUR LANGUAGE,’” SAYS COFOUNDER AND MANAGING DIRECTOR GUIDO ARCELLA M.M. ’15.

The Mayan people of Mexico’s Yucatán Peninsula breathe new life into their ancient heritage, with help from a Berklee alum.

Itzincab, a village of little more than four blocks nestled in Mexico’s Yucatán jungle, is named after an insect that has played a central role in the local Mayan culture for centuries. In the Maya language, itzincab means “little brother of the bee,” in honor of the honey-maker that has traditionally provided food and medicine to the Maya. But, as with the indigenous stingless bee, the Maya language itself is in danger of vanishing.

Though many of Itzincab’s elders speak Maya, the younger generations mostly do not. The push to eradicate the language began with the Spanish conquistadors, but the threat to it today is from within Mayan communities, where it is sometimes viewed as a lower-status language relative to Spanish. Not only do Mayan children often not speak it at home, but those who use it in public are sometimes teased by their peers for doing so.

This stigma is one that GUIDO ARCELLA M.M. ’15 and his colleagues at Barrio Maya and Múul Paax are working to change. Arcella, who also runs a film scoring business and a recording studio, is the cofounder and managing director of both projects, which are trying to stem the loss of Maya and to support indigenous music. Barrio Maya is doing this by supporting both the continuation of Maya through rap and the musical aspirations of rappers on the peninsula, while Múul Paax creates and performs pre-Hispanic instruments.

“Barrio Maya and Múul Paax are trying to spread the message that, ‘Hey if we don’t do something, a huge part of our culture is going to be lost: our language,’” Arcella says.

Part of that “something” the groups are

doing is using music to help the Mayan community restore pride in its culture and see its heritage as something worth preserving.

“You don’t appreciate what you don’t know,” says Nadia Zupo Herrera, the stagecrafting director for Múul Paax. “If you make it a daily practice to be exposed to Maya it becomes normalized and appreciated.”

The idea for the projects came to Arcella after he graduated from Berklee Valencia with a master’s degree in scoring for film, television, and video games. Arcella, a 32-year-old from Argentina, returned in 2015 to the Yucatán Peninsula, where he had lived for a time as a child in a Mayan village because of his father’s job in the area’s hospitality industry. Fresh out of the graduate program, he started a series of Mayan music labs at Hacienda Ochil, which was once a cattle ranch and henequen farm but now serves as a venue for private events and art projects.

Inspired by the success of these labs, Arcella wanted to figure out how to tap into the musical opportunities they presented. He reached out to Berklee Valencia’s International Career Center for ideas and was advised to contact fellow alumnus GAEL HEDDING B.M. ’05.

Hedding happened to be home, in Cancún, when Arcella got in touch with him in January 2017. “Having grown up in the region, I have an understanding of the challenges and opportunities that exist among Mayan communities,” says Hedding, who is now the director of the Berklee Abu Dhabi Center but remains an active advisor to Múul Paax and Barrio Maya.

The pair collaborated on a couple of events in which Hedding did live sound and production support. “Guido’s enthusiasm and dedication was infectious,” says Hedding. Together, they began brainstorming the best way to leverage the Mayan community’s talent and potential. “We noticed that Mayan rap and pre-Hispanic instrument fabrication were both worth supporting, and that such support needed to happen through the form of education,” Hedding says, explaining how he and Arcella came up with the idea to start Barrio Maya and Múul Paax, which were, and continue to be, incubated by Fundación Haciendas del Mundo Maya (fhmm), a nonprofit Arcella’s mother directs that focuses on promoting cultural activities, nutrition, infrastructure, and economic and social enterprises in Mayan communities.

As Arcella and Hedding were considering where to take these projects, Arcella started two other endeavors that he still runs today: Arcella Sound, his film and video game scoring business, and Casona Indie Music Studio, his recording studio staffed with an engineer. It was at Berklee Valencia, he says, that he really learned how to run a studio, how to make his music sound professional, and how to use production tools to make that music shine.

Arcella manages to balance his leadership of these two projects with his own artistic work. This summer, Arcella was working on scores for two movies and two video games, in addition to numerous other engagements, including giving a master class in Mérida on soundtrack design in film; auditioning child musicians to be part

of a group that would play at Festival Paax on the Mayan Riviera; and giving film and game composition workshops at the Musicians for the World event in Peru. Within the last year, he’s also done an artistic residency at Southern Methodist University in Dallas, where he had received his undergraduate degree in music composition and violin performance.

One of the ways Arcella and Hedding launched their initiative, in 2018, was by offering weekend classes in Ochil, and later Temozón, to children aged 5 to 18 as part of a project they called Múul Paax, which means “music among us” in Maya. Divided into three groups by age, the kids would rotate among instructors who would teach them stagecraft and choreography, instrument construction, and music theory. Some children would also learn how to play instruments. During the week, the 50 or so participants would disperse back to their communities and rehearse in their villages’ cultural centers.

But, as with nearly every other group activity in the world, these classes ended in the spring of 2020. As the pandemic progressed, Arcella and his team looked for new ways to keep the children involved. For the youngest students, Múul Paax provided education through Zoom video calls, which culminated in recorded video projects in each of the participants’ communities. In these videos, the students dressed

in costume to personify the animals and food found in a Mayan milpa, or cornfield and garden.

One girl who participated in the program, Sinahi, said it made her happy because she got to meet children from neighboring towns and learned many new things, such as how to play the flute. As is common for children in the area, Sinahi, now 11 years old, had never had any music education.

To complement the Zoom instruction, Arcella’s studio made a series of audiobooks explaining Mayan cosmology through a child’s eyes. The series, called Llamada del Caracol (“Call of the Shell”), aired on national radio.

Meanwhile, the oldest group of Múul Paax students, who lived mostly in the Campeche town of Bolonchén de Rejón, gathered in the local park to pick up the on-and-off WiFi signal on their cell phones and connect to lessons over WhatsApp. It was this group that acquired its own space, also in Bolonchén, where they could get together twice a week to work on building their instruments and practice playing them, which they continue to do today.

‘We Are Them’

During one of these semiweekly sessions, in mid-June, 17-year-old Angel Nah Abnal stood behind a table that held an array of whistles, flutes, rattles, and conches, and went through the function and purpose of each one.

He first picked up a vase-shaped ves-

sel no larger than his hand, cupped it, and blew into the neck. As he slowly removed his palm, the instrument released a whooshing sound that mimics the roar of a jaguar, an animal native to these parts. Another pocket-sized object, which had an inscrutable little face carved on it, is called a silvato de la muerte (“whistle of death”); it produced a shriller sound. This is the instrument the Maya would play to scare off their enemies during battle, Nah Abnal explained.

In a way, Nah Abnal is also using the whistle of death to defend his people. “I think it’s important to raise this Mayan culture because the new generations are ashamed to belong to the Mayan culture, and that is a big mistake because we should feel proud of our culture and what we are,” he says in a video about Rap & Raíz (“Rap and Roots”), a collaboration between Múul Paax and Barrio Maya in which the two groups offer joint concerts.

Nah Abnal’s sentiment is widely shared in Múul Paax. His bandmate and brother, José Nah Abnal, says that Múul Paax aims to rescue Mayan music through the instruments. “Because we come from the Maya, more than anything, we need to respect this type of music,” he says. “It’s our origin.” José Nah Abnal plays turtle shell as well as tunkul, a carved-wood percussion instrument that produces two tones, one to symbolize the day and the other the night. It represents, he says, the duality of nature.

Standing next to the brothers was 18-yearold Angel Poot Tec, who plays the zacatán, a drum made out of a tree trunk and deer skin. He says he too is concerned about people

abandoning the culture.

It’s this feeling of loss of culture that inspired the group’s leader, Roman Dzul, a local music instructor, to put together the group Yum Paax (“God of Music”) seven years ago to teach children Mayan ritual music. Several members from this group joined the Múul Paax project. This group then turned into what is now Múul Paax. For Dzul, it’s important to pass this musical tradition to the young to keep it alive.

One way to ensure this legacy, says Pedro Salvador Hernández, the group’s instrument construction consultant, is to give Mayan performers the ability and know-how to build their own tunkuls, zacatáns, ocarinas, rainsticks, and the like.

Though they can’t be sure that the instruments they build are exactly what their forebears used, they know from ancient paintings and evidence from archaeological digs the type of instruments the Maya of pre-Hispanic Mexico likely played.

However, it would be a mistake to speak of this civilization as one that existed only in the past. “They say the Maya are not around anymore, but that’s a mistake. They still exist; we are them,” Dzul, the teacher, says.

This year, Múul Paax has had four or five big concerts around the Yucatán Peninsula, and has performed at various Mayan ceremonies, such as those to bring rain. These concerts include the group’s Rap & Raíz collaborations with Barrio Maya, which provides a logistical and educational platform for the development of Yucatán rappers who incorporate Maya into their rhymes.

One rapper who’s benefited from Barrio Maya’s programming is a 21-year-old from Espita who calls himself la2c. He began rapping at age 11 and soon had ambitions to record. But living in a small town that’s a two-hour drive from either Mérida or Cancún, he had little access to studios. That is, until a local gang offered him the opportunity to use the recording facilities belonging to one of its members.

“I was part of the gang but not because I wanted to be but because they were giving me the possibility to record,” la2c said.

As a reluctant member of the gang, la2c says he found himself in many conflicts. These culminated in an incident that changed his life. At 14, he was part of a fight that left him badly beaten and unconscious. When he came to, he realized that he had been deposited a block from his home, saved by an adult he didn’t know and hadn’t seen in town before. It felt, he says, like divine intervention. He considered it a second chance and realized that day that he wanted to dedicate his life to doing good. He left the gang and renewed his focus on his music.

Today, he works with a Mayan rapper and producer who goes by the name Masewal, which is Maya for “indigenous guy,” and la2c ’s lyrics, a mix of Spanish and Maya, are about spreading positivity. On a day this June in Masewal’s studio, moments after la2c describes his story, he performs his song “Bienvenidos a Yucatán.”

He starts, in Spanish: Welcome to my state, welcome to my land

You are all invited. If you come here, you stay

Because you will truly fall in love with its festivities, traditions, its stories

And embroidery of my mestizo people

Of the Maya people, my culture is first

About halfway through the tune, he switches to Maya and tells a story about a day in the life of an indigenous man who gets up, goes to the milpa, cuts some wood, and spends time with his family.

As he’s rapping this, he’s steps away from the milpa belonging to Masewal’s family. Though loosely translated in English as “cornfield,” a milpa is a system that traditionally provides the Maya with all their needs for a comfortable life, including corn and other crops, medicinal honey, and material to build houses, says José Arellano, fhmm’s biodiversity senior advisor.

These days, some young Mayan men are also seeking different ways to find a comfortable life. la2c, like many others in the peninsula’s interior, makes his living by working in construction in the booming Mayan Riviera, where luxury resorts have sprung up from Cancún to Playa del Carmen to Tulum. This influence is also showing up in la2c ’s rhymes. In “Bienvenidos a Yucatán,” he raps:

We are truly fortunate to have what we have

That we earned with effort

My culture is universal

It is always recognized all over the world

Everyday they visit it and admire it

Its gastronomy, cenotes, and its beautiful beaches

la2c ’s rhymes flow easily over the tune’s catchy beat. “Barrio Maya helped me to professionalize the music of my songs,” he says in the Rap & Raíz video. “They trained me in approximately 10 weeks, starting with music theory; they taught me to compose, to make the basis of a track. And then I learned to structure a lyric with coherence.”

Barrio Maya delivered this instruction through video content. The prerecorded lessons, offered annually through a free 10week series called Make Rap Music from Your Cell Phone, cover music technology to help rappers make their own beats in a software app; lyric writing, including in Maya; stagecraft and choreography; and general master classes by another rapper.

la2c started rapping in Maya about five years ago, shortly after he met Masewal, who himself had started rapping in Spanish before switching to Maya. The two rappers speak Maya at home, but Masewal says he noticed that people are forgetting how to speak it. As with the members of Múul Paax, Masewal says it’s important for him to rescue this part of his identity and to let people know about his culture and music.

Another rapper at Masewal’s studio that day in June, a 26-year-old who goes by the name Verso Maya, emphasized that there is no contradiction between embracing rap— and the style that often goes along with it— and being Mayan. Even though they might dress differently from what some might expect of people from his culture, they are

still Mayan, he said.

“Rap, Barrio Maya, Múul Paax and other projects are looking for the people to be proud of their culture, and their music, and their food,” says Fernando Santandreu, the groups’ education coordinator.

Though both groups are currently incubated by the nonprofit fhmm, they help support themselves through concerts, such as Rap & Raíz, instrument sales, and some fundraising. In addition, Arcella ran an online film scoring competition called Rec Change from 2019 to 2021 to help raise funds for Barrio Maya. Still, he says, a major goal of his is to make the groups self-sustainable by gaining the long-term financial support of more organizations.

Barrio Maya and Múul Paax continue to collaborate in ways beyond the Rap & Raíz concerts. One might think that acoustic pre-Hispanic-inspired music might not mesh well with rap but, says Santandreu, the combination is actually a new and surprising way to make music.

Back in Itzincab, the town named after the bee, children gather in the town’s cultural center to describe their experience with Pat Boy, a well-known Mayan rapper who worked with them a year before their workshops with Múul Paax.

Pat Boy, who is from the neighboring state of Quintana Roo, had received a federal grant in 2019 to hold a cultural workshop and contacted Arcella for ideas on what to do.

What resulted was a workshop in Itzincab for children aged 8 to 14 in which the rapper worked with the kids over the course of three months, teaching them to put together a rhyme in Maya, build a song, and record the final product.

The children, now in their early teens, said it was a lot of work: They had to study Maya, learn a bit about various rap genres, practice how to move during a performance, and familiarize themselves with the basics of recording and production, such as how to use a microphone.

It was an opportunity, Pat Boy said in a video about the workshop, for the children to learn that Mayan rap exists and to see what can be done in the Maya language. “Many people apparently do not speak Maya. But with this workshop many have already become interested in learning phrases, saying things in Maya,” he said.

The children describe the process as a happy and emotional one. Everyone in town was very proud when the song, in which a little iguana is invited to town to enjoy some food, was posted on YouTube. In school, teachers played the recording for the children to enjoy and dance to.

And despite some bullying from kids in a neighboring town who derided the novice rappers for using Maya, the children smile when they describe their time with Pat Boy and remember the song and video.

“Everyone has a goal. Maybe it’s to become a writer, a poet, a teacher—whatever it might be,” Pat Boy said. “But now they see the great importance of what the Mayan language is, [and] what can be done as an artist.”

GLOBAL PARTNER SPOTLIGHT

THE INTERNATIONAL COLLEGE OF MUSIC

Known for its rigor, Kuala Lumpur’s International College of Music has set up hundreds of students for success at Berklee over the past 25 years.

STORY BY Rebecca Beyer

JULIAN CHAN B.M. ’01 was a 16-year-old trumpet player in Malaysia’s Sarawak State Symphony Orchestra when he first fell in love with the idea of being a sound engineer. The orchestra had traveled to Monash University in Australia for a week of classes and performances, and Chan had noticed all the people working behind the stage during concerts.

“Brass players tend to have a lot of rest,” he says, laughing. “My mind would start to wonder, and I was really drawn to what the tech guys were doing.”

On a visit to the university’s music technology department, Chan asked someone how he could break into the field. The man had one tip: Berklee College of Music. When Chan returned home, he persuaded his parents to let him pursue his dreams. Then, just as he was ready for college, the Malaysian economy took a dive, making the cost of Berklee prohibitively expensive in Malaysian ringgits.

“We were thinking, ‘This isn’t good. This might not happen,’” Chan remembers.

Fortunately for him, the principal of his music school recommended he look into a new contemporary music college in Kuala Lumpur. The International College of Music, or icom, had just launched a formal partnership with Berklee.

“ icom became the lifeline,” explains Chan, who began there as a student in 1998.

For aspiring musicians in Malaysia, icom is still a lifeline. Since 1997, nearly 200 of

its students have transferred to Berklee through its official status as a Berklee Global Academic Partner school.

Formerly part of the Berklee International Network (bin), Global Academic Partner schools have credit-transfer agreements with Berklee, allowing students to complete core music courses (known as the Berklee track) at the partner school. A major benefit of such partnerships is the cost savings.

bin first launched in 1995, with three schools: Philippos Nakas Conservatory in Greece, Rimon School of Music in Israel, and l’aula de Música Moderna i Jazz del Conservatori del Liceu in Spain. Gary Burton and Larry Monroe, under the leadership of then-President Lee Eliot Berk, spearheaded the program.

“It came from seeing the need to diversify our enrollment, to create more pathways for people from outside the United States to get access to the Berklee education,” explains Jason Camelio, assistant vice president of Berklee Global Initiatives. “The avenue they saw to do this was to work with institutions that were like Berklee—typically those are places where Berklee graduates have gone and set them up, taken a germ of the Berklee genes, and planted it in that community and culture.”

Today, Berklee has 25 Global Academic Partners, including three in the United States. The schools are “like a bridge” to Berklee in Boston, Camelio says. “Students get this core music experience, and then they tend to get accepted on a higher level, to get scholarships, to do incredibly well academically, and to graduate at a higher level.”

Since 2015, only two other Global Academic Partner schools—sja Music Institute in South Korea and Rimon School of Music—have sent more students to Berklee than icom has. Eighty-two percent of students who transfer from icom graduate from Berklee, compared to 70 percent who come from other partner schools. (Across Berklee, the graduation rate in 2022 was 67 percent.)

icom’s success is due in part to IRENE SAVAREE B.M. ’88 , the school’s founder, president, and chief executive officer. In the mid-1990s, after a successful singing career in Malaysia as a solo act, and with her sister, HELEN SAVARI-RENOLD B.M. ’88, Savaree was approached by investors to start a music school in her home country.

“They had one caveat,” she explains. “They said, ‘You need to have some kind of an institutional tie-up with Berklee.’”

In 1997, when icom formally became part of bin, the Malaysian prime minister and the heads of many of the country’s music labels attended the formal signing ceremony.

Students in icom’s Berklee track, also known as the Foundation in Music program, take courses in music theory, contemporary harmony, ensembles, music technology, ear training, and traditional harmony, among other subjects. The program is open to anyone, not just those planning to go to Berklee. (The school also offers diplomas in sound production and in music.) After a full year in the Foundation in Music program, students are able to transfer as many as 54 credits to Berklee, where they can focus on their specific majors.

“If I didn’t have this pathway to Berklee, I might

“I think the role that icom has been playing and is still trying to play is to instill that foundation in students to be able to excel not only at Berklee but also to thrive in a professional environment,” says ALI AIMAN B.M. ’10 , who heads icom’s Berklee track. “It’s quite a rigorous program.”

The rigor pays off. Berklee student Will Tiong, a vocalist who hopes to work on the business side of the industry, says he “butchered” his audition to icom because he had no previous experience in ear training or sight-reading. After a year at icom, however, he nailed his Berklee audition and even received a scholarship.

For Tiong, who enrolled at icom specifically for its Berklee transfer program after initially studying finance at another institution, icom had several advantages, including its cost savings and the opportunity to study music formally without a four-year commitment.

“I was making a big switch at the time,” he explains. “The low commitment level appealed to me. It was a good test to see if I really did want to go into music, and it turns out that really was what I wanted.” This summer, Tiong interned with a record label and with a music marketing guru who tapped him to run Barbra Streisand’s TikTok account.

The icom community is small and closeknit: About 120 students are currently enrolled and about 15 faculty, including several Berklee and icom alumni, teach on campus.

Students and faculty regularly gather just outside the school’s doors where a vendor sells coffee, tea, soda, boiled eggs, and local cakes.

“Lecturers go out there, students go out there, and we’d talk about our experiences,” Chan remembers. “This is what I think was special during my time.”

Although students are generally academically prepared for Berklee, they still often experience culture shock when they arrive in Boston.

“The biggest shock is just how big it is and how diverse,” Chan explains, adding that his transition was eased by the fact that everyone seemed to be in the same boat. “It helped that everyone you were meeting was in some way or another not from [Boston].”

NISA ADDINA B.M. ’18 , a violinist who first learned about Berklee from her mentor,

SHAFIEE OBE B.M. ’87 , says being able to go to Berklee with friends and classmates from icom helped her transition.

“I wasn’t feeling so alone,” Addina says, adding that the Malaysian students at Berklee got together often.

Since ic icom om is a hub for music students from across Asia, its transfer students at Berklee also include people from China, India, Indonesia, Japan, the Philippines, Singapore, and South Korea, among other countries.

Several members of Savaree’s own family have gone to Berklee. In addition to her and her sister, four of her nieces and nephews have attended, including two who transferred from icom.

“It’s been a wonderful relationship,” Savaree says. “Besides the Berklee brand, which opens doors, what I personally find very valuable in the Berklee-icom relationship is the sense of community.”

SHEREEN CHEONG B.M. ’17 echoes that sentiment. When she served as music director for one of Victory Boyd’s shows in Los Angeles, Cheong called everybody she knew from her time in Boston and was able to fill out the horns section and a string quartet.

“It was a mini-Berklee reunion,” she says, laughing. “It was very warm.”

icom’s Berklee track has paid off for others as well.

“If I didn’t have this pathway to Berklee, I might not be doing what I’m doing now,” says Chan, who has done sound mixing for video games including Guitar Hero and Rock Band, and now works for the Eagles’ Don Felder as an engineer.

SOYA SOO B.M. ’15 agrees. As a teenager in Malaysia, he noticed Hans Zimmer’s name popping up in the credits of his favorite films and video games; today, he works as a studio engineer for Zimmer’s Remote Control Productions in Santa Monica, California. In his career so far, Soo has collaborated with the film composer John Powell on Solo: A Star Wars Story and FERDINAND , and has worked with Zimmer on Dune, The Lion King, and Dark Phoenix, among other projects.

not be doing what I’m doing now.” JULIAN CHAN

“Without icom, I couldn’t go to Berklee, and, without Berklee, I couldn’t learn all the technology or know anyone in the industry,” Soo says. “I wouldn’t be where I am.” CAPTIONS HERE

A SPECIAL SERIES TRACKING EVOLUTIONS IN THE MUSIC

As evidence of music therapy ’s benefits grows, the practice is increasingly showing up in hospitals, schools, and more.

STORY BY Susan Gedutis Lindsay

“There were hardly any music therapy departments in hospital settings. It was even more rare to see a music therapist who had an administrative role over a department.”

It was only 15 years ago that music therapy was still considered to be at the periphery of medical practice. At the time, Rich Abante Moats was at Berklee, studying to enter the field.

“There were hardly any music therapy departments in hospital settings,” she says. “It was even more rare to see a music therapist who had an administrative role over a department.” But today, as director of Integrative and Creative Arts Therapies at AdventHealth in central Florida, MOATS B.M. ’07 M.A. ’19 oversees a team of 12 music therapists who work with adults and children in a variety of inpatient and outpatient hospital settings: icus, surgery, oncology, neurology, covid, and neonatal units.

AdventHealth, Moats says, now recognizes that music therapy benefits not only the patients, but also the business side of hospital care: “People are able to leave the hospital sooner if they receive music therapy. Patients that receive music therapy score their experience higher than others.”

AdventHealth is one of many health care institutions around the country that have embraced music therapy in recent years. In Boston alone, there are now eight music therapists at Children’s Hospital, and six at Massachusetts General Hospital; both programs made this expansion in the last 10 years. In 2017, the National Institutes of Health collaborated with the John F. Kenne-

dy Center for the Performing Arts and the National Endowment for the Arts to form the SoundHealth initiative to provide $20 million for music therapy research.

Thanks to years of studies supporting music therapy’s benefits, demand for music therapy is growing in a variety of clinical and community settings. A half-century of effort by board-certified professionals is finally codifying the practice and demonstrating its impact on concrete health outcomes.

The field now abounds with well-paid clinical positions, and a handful of states are licensing music therapists beyond the expected board certification. “The music therapy field is flourishing,” says Joy Allen, chair of Berklee’s Music Therapy Department.

According to a September 2022 report by consulting firm SkyQuest Technology, the American Music Therapy Association estimates that the demand for music therapy in the U.S. has doubled in the last five years. The report also notes that U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics numbers indicate there was a 17 percent increase in job openings for music therapists during roughly the same period.

Music therapy effects positive changes in patients’ well-being by involving them in live music-making. The music, often im-

“The music therapy field is flourishing.”

provised, is made using a wide variety of instruments—including guitars, ukuleles, percussion instruments, keyboard, and the voice. It draws on a range of genres and styles, as patients are encouraged to use their own natural musicality to express themselves and to connect with others. Through this music, therapists teach relaxation, techniques to cope with pain, and tools for managing stress and chronic illness. The therapy can be particularly helpful in getting patients to process emotions that they are unable to express in words. The work can be done individually or in groups, depending on need.

“Music affects areas of the brain well beyond cognitive areas, including parts that affect mood, feeling, and emotion,” says Suzanne Hanser, chair emerita of Berklee’s Music Therapy Department. “Music therapists can focus on these areas to develop new pathways in the brain.”

The field is also benefiting from a cultural shift in medicine: a growing awareness of the value of a patient’s quality of life. “As science has advanced in terms of ‘curing’ and mitigating some of the losses from illness, it mandates more opportunities for behavioral health and rehabilitation sciences,” Allen says. “This shifts the emphasis to discovering what is meaningful for an individual and finding therapeutic means to help them meet health challenges they need to learn to live with.”

Researchers and educators like Hanser are playing a critical role in continuing to establish the practice. She wrote a seminal music therapy textbook, The Music Therapist’s Handbook, in 1988, founded Berklee’s Music Therapy Department in 1995, and chaired it from 1996 to 2015.

“These last 10 years, the biggest change was that we went from the Western medical disease model—the whole idea of the disabilities, the disease of [people] who had so many abilities,” Hanser says. “Now we’re moving far away from diagnostic categories and disabilities and looking at the whole person.”

As research began to show positive health outcomes associated with practices such as meditation, yoga, acupuncture, and traditional Chinese medicine, the science of mind-body medicine has grown, and music therapy is part of it, Hanser says.

The practice is also finding stronger footing in public schools. NOA FERGUSON B.M. ’09 is in her eleventh year of providing music therapy to schoolchildren as cofounder of Spectrum Creative Arts in Rochester, New York. Her team of five music therapists serves 50 schools in 12 districts.

“In the past 10 years that I’ve been a clinician, music therapy has become a licensed profession at the state level in a handful of states across the U.S.,” Ferguson says. (All U.S. music therapists share a board-certification credential.) “Here in Roches-

“Music affects areas of the brain well beyond cognitive areas, including parts that affect mood, feeling, and emotion.”

“Here in Rochester, music therapy has started to become a household term that caregivers know to advocate for within their school districts and education systems.”

“Therapists were adapting and changing interventions we once thought were rigid to help clients achieve things in music they never thought possible before.”

Noa Ferguson

ter, music therapy has started to become a household term that caregivers know to advocate for within their school districts and education systems.”