MAGAZINE

Published twice yearly, Boston Art Review's print publication is the best way to dive deeper into Boston's art community. Explore the archives

ARE YOU SUBSCRIBED?

bostonartreview.com/issues

SPECIAL ISSUE: COLLECTIVE FUTURES FUND

DIGITAL EDITION 2022

Founder & Editor-in-Chief

Jameson Johnson

Creative Director Julianna Sy

Senior Editor

Jacqueline Houton

Editor-at-Large Leah Triplett Harrington

Managing Editor Kaitlyn Ovett Clark

Editor & Operations Karolina Hać

Editors Maya Rubio Jessica Shearer

Copy Editor Zoë Gadegbeku

Design Assistant Victoria Wong Communications Manager Gina Lindner

Finances Sarah Valente Phil Zminda

Board of Directors

President: Jameson Johnson*

Clerk: Karolina Hać*

Secretary: Sarah Valente* Nakia Hill

Jacqueline Houton* Beau Kenyon Cher Krause Knight Gloria Sutton Gabriel Sosa

Boston Art Review is an online and print publication committed to facilitating active discourse around contemporary art in Boston and beyond. BAR seeks to bridge the gap between criticism and coverage while elevating diverse perspectives.

Contributors

Stefanie Belnavis Eliza Browning Olivia Deng Michelle Falcón Fontánez Loi Huynh Gina Lindner

Claire Ogden Matthew Akira Okazaki Sophia Paffenroth Lian Parsons-Thomason slandie prinston Jonathan Rowe L Scully Jacquinn Sinclair Martina Tanga An Uong Madison Van Wylen Lex Weaver

Contact PO Box 390003 Cambridge, MA 02139 Bostonartreview.com @bostonartreview

ISSN 2577-4557

Submissions

Visit bostonartreview.com/submit for submission guidelines. All submissions should be sent to submit@bostonartreview.com.

Inquiries

For general inquiries, including donations, advertising, and open positions, please contact editorial@bostonartreview.com.

Copyright

All content and artwork © the writers, artists, and Boston Art Review (BAR)

* Ex Officio

Foreword by Abigail Satinsky and Camila Bohan Insaurralde

Letter from the Editor by Jameson Johnson

Sustaining Practice Awardees

New Works & Ongoing Platforms Awardees

PROFILES

14 18 28 30 42

BOSSCRITT Critique & Curatorial Club by Gina Lindner

How Eli Brown Is Finding Family Through the Ages by Lian Parsons-Thomason

AgX Film Collective Fosters Community for Filmmakers by Olivia Deng

Artists and Moms Become Architects of Joy by Jacquinn Sinclair

Reimagining a Rhinoceros Womxn by Lex Weaver

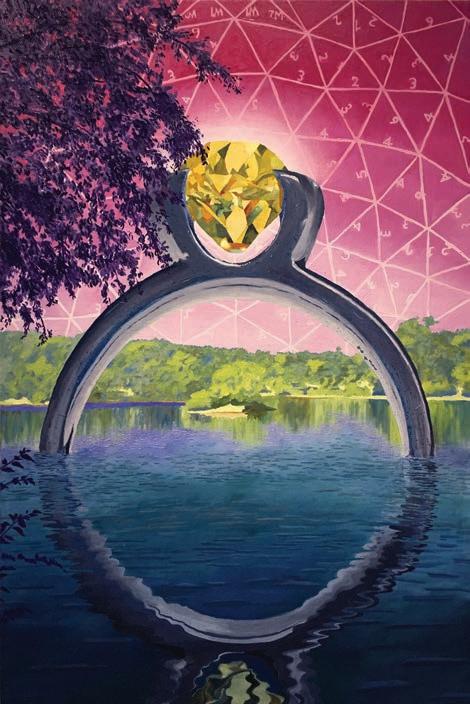

Thinking in Poems, Painting with Power: In the Studio with Marlon Forrester by L Scully

Moving a Community Forward One Dance Step at a Time by Sophia Paffenroth

Three’s Company & HOT Progress: The Rise of Boston’s Mutual Aid-Driven Queer Haus by Lex Weaver

Whitney Mashburn’s Online Archive Holds Space for Artists with Disabilities by Lian Parsons-Thomason

CONTE

50 54 56 58

42

77

4 5 6 8 2 DIGITAL EDITION 2022

PROFILES

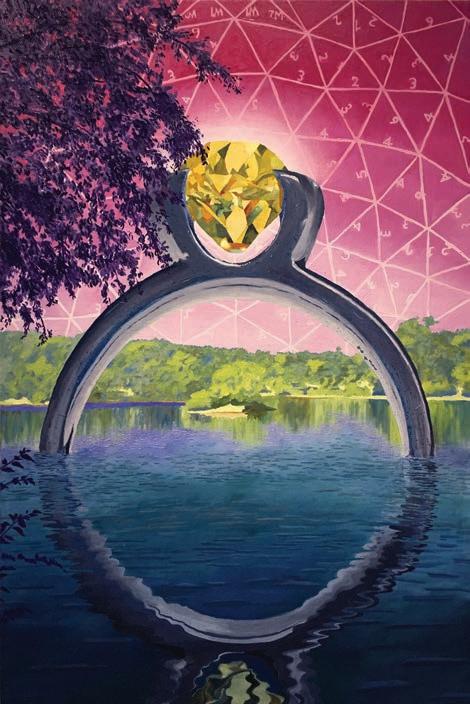

Love Meets Legal Jargon: Gabriel Sosa on Parenting, Pedagogy, and Subverting Public Space through Language by Claire Ogden

We Are Feminists. We Are Futurists. by L Scully

Visibility and Growth: How the Hidden Prompt Is Reconsidering the Archive by slandie prinston

The Streets Belong to Us All: A Photo Journal by Jaypix Belmer with L Scully

CONVERSATIONS

Drawing from the Past: A Conversation with Dave Ortega by Jonathan Rowe

See You in the Future: A Promise and Request to Change the Narrative Around Mass and Cass by Matthew Akira Okazaki

Inside Out: Museum Talk with Furen Dai by Martina Tanga

On Belonging: In Conversation with Ngoc-Tran Vu by An Uong

Diagnosing Museums, Healing Ourselves: In Conversation with Emily Curran and Josephine Devanbu by Eliza Browning

NTS

62

66 70 74

26 38

34 38 46 SPECIAL ISSUE: CFF 3

10 22

Dear Collective Futures Fund past, present, and future artists,

First of all, we would like to extend our gratitude to you for making the work you do here in this place. Thank you for bringing your work to us for support, for trusting us with your visions, for letting us participate in the futures you are building. And thank you in particular to our inaugural cohort of Collective Futures Fund 2021 grantees for participating in this Boston Art Review issue, for sharing your process, thinking, and making, in all its vulnerabil ity, success, and possible failures. It is not an easy time to be an artist. It is not an easy time for anyone these days at all. We see you out there supporting each other and your neighbors, extended relations, and communities in the most creative of ways.

The Collective Futures Fund started in the fall of 2020 with an invitation from the Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts to join their Regional Regranting program, which part ners with local arts organizations around the country to make grants to artists and collec tives for projects that chart new creative territory in their communities. Tufts University Art Galleries joined as the Boston partner when the program expanded to thirty-two cities. In our first round in 2020, we distributed $60,000 in emergency support during the coronavirus pandemic to visual artists in the region for basic needs such as food, housing, medical costs, connectivity, and child care. We were then joined by an anonymous donor, bringing our yearly total of granting to $80,000, and started funding projects at three different levels—research, new projects, and ongoing work—with grant amounts between $2,000 and $6,000.

Trust is foundational to our granting practice supporting artists whose work falls outside the scope of traditional presenting organizations and/or funding opportunities. Collaborations and experimental projects grow and stretch over the course of the process; sometimes $6,000 is critical support to realize and sustain a project, and sometimes it’s just the start. We fund artists to begin their work and lead independently, to engage publics while creat ing spaces of experimentation, joy, learning, and reflection. This can take the form of art ist spaces, exhibitions, publications, gatherings, online projects, and public research and learning—contributing to a vibrant and welcoming cultural ecosystem in Greater Boston while also critically reflecting on its challenges and struggles. We invite you to be part of our network. Please learn more about us and our next round of 2022 grantees and jurors and consider applying at our website, collectivefuturesfund.org.

A very special thank you to the Boston Art Review team for your passion and dedication to our Greater Boston arts community and for partnering on this issue. Your unflagging commit ment to documenting, archiving, and publishing artists’ work is a vital resource from which we can make our futures. And finally, thank you to the Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts and our anonymous donors for their visionary support to make this program possible.

Satinsky, Program Director Camila Bohan Insaurralde, Program Coordinator

4 SPECIAL ISSUE: CFF

Warmly, Abigail

FOREWORD

Dear friends,

I’m pleased to share with you a special issue of Boston Art Review celebrating the inaugural cohort of the Collective Futures Fund.

When our friends at Tufts University Art Galleries announced they would be overseeing the distribution of funds from a regional regranting program by the Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts in 2020, we got excited. Ask an artist what they need to be successful in Boston and I guarantee they’ll answer one of three ways: space to make their work, space to show their work, and financial support for their work. The Collective Futures Fund thus fills a crucial funding gap in our regional arts ecosystem, particularly focusing on the work of art ists who have been historically underrepresented in institutional spaces. The grant has a very low barrier to entry and very few strings attached, and—perhaps most crucially—artists are trusted to allocate the funds wherever they are most needed.

We believe in the mission of this grant, and more importantly, we believe in the work that these artists, collectives, and organizers are doing to serve communities in Greater Boston. We want to celebrate what we hope will be a collective of artists united by this grant for years to come.

To honor the radical and experimental nature of this grant, we sought to use this issue as a site for our own experimentation. In turn, this project welcomed several firsts: It’s our first digitally accessible issue, our first free issue, and our first issue centered on a specific group of artists rather than a theme.

Unlike most of the stories we publish, many of the projects highlighted in this issue are ongoing or works-in-progress, are led by large groups, or have no permanent site. This unconventional assignment invited us to consider how arts writing, documentation, and storytelling can be responsive and additive to the experimental spirit inherent to these projects.

Naturally, collaboration was central to every step of this process. I’m so grateful to all of the writers who eagerly took on assignments to cover projects that were still largely in-progress, the photographers we sent out to locations across the region, and the artists who lent their voices every step of the way. Each and every person who contributed to this issue brought a tremendous amount of patience, tenacity, and care to this work.

With gratitude,

Jameson Johnson Founder & Editor-in-Chief

Jameson Johnson Founder & Editor-in-Chief

5 LETTER FROM THE EDITOR

EDITOR'S LETTER

SUSTAINING PRACTICE AWARDEES

Eli Brown

Eli Brown is a Boston-based interdisciplinary artist working in sculpture, drawing, and community orga nizing. Brown explores gender through time and intergen erational dynamics. His practice revolves around learning transness as a lineage—an evolutionary phenomenon that is not always human. Both experiential and rooted in queer ecologies, Brown’s research bridges queer theory and environmental science and challenges the problem atic foundations of evolutionary biology and speciesism that continue to inform our bodily experiences.

Emily Curran and Josephine Devanbu Emily Curran is an educator and artist with decades of experience in collaboratively building communitycentered museums, cultural organizations, and creative initiatives. She is based in Boston.

Josephine Devanbu is an Indian-American artist eager to widen her view and field of play. She’s drawn to both art making and critique as fertile grounds for collective self-discovery. After running Look at Art. Get Paid. with Maia Chao for several years, she has recently downsized to carving soap.

Furen Dai Furen Dai received her BA in Russian language and literature from Beijing Foreign Studies University and her MFA from the School of the Museum of Fine Arts (SMFA) at Tufts University. She has presented her work at the New England Triennial 2022; the National Art Center, Tokyo; and the Shelley and Donald Rubin Foundation, amongst others. Dai has participated in residencies, including the International Studio and Curatorial Program, Art Omi, and MacDowell. She received public art commissions from The Art Newspaper (2019) and the Rose Kennedy Greenway (2020). She is the recipient of the Milton and Sally Avery Arts Foundation Fellowship (2017), the ZK/U Berlin Fellowship (2021), and the SMFA Traveling Fellowship (2022).

FeministFuturists

Freedom Baird is a multidisciplinary artist exploring the interconnection between humans and nature. Her work addresses systems and society and often includes performance and viewer participation. She holds master’s degrees from the Media Lab at MIT and the Massachusetts College of Art and Design and has exhibited recently at the Center for Maine Contemporary Art and the Fuller Craft Museum.

Christina Balch (she/her) is a multidisciplinary artist, producer, and technologist. Her work explores percep tions of self through digital technology and data.

6 SPECIAL ISSUE: CFF

Nancy Hayes was a ceramic sculptor before becoming a painter who develops forms and visual landscapes built from her imagination. Hayes creates elaborate compositions using color, line, pattern, and shape, building characters with their own texture and biology. She lives and works in South Dartmouth, Massachusetts.

Marjorie Kaye is a visual artist currently based in North Adams in the Berkshires. Although primarily a painter working with gouache, she has explored her wild, unruly yet precise compositions in wood as well. She is the director of Galatea Fine Art in Boston’s SoWA Art and Design District in addition to her art practice, has had extensive exhibitions, and has been awarded grants from the Provincetown Art Association and Museum and the Massachusetts Cultural Council.

Anna Katharina (AK) Liesenfeld is a fashion designer and virtual reality (VR) concept artist. She has worked with Boston Fashion Week, the Peabody Essex Museum, and the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston, creating garments and accessories that explore identity in fashion. Liesenfeld will be showing a salon made entirely using VR. With this piece, she hopes to inspire the audience to join her in the conversation around the legacy of pioneering female educator Helen Temple Cooke.

Karen Meninno is a mixed-media sculptor, digital artist, and fashion designer whose work spans many realms of futuristic visions. Currently, Meninno investigates the peculiarities of the digital (machine-based) and the analog (human or organic) in the digital spaces we inhabit and the effects of interactions between them.

Carolyn Wirth, a Boston-area sculptor and occasional installation artist, uses the figure to describe people and landscapes that have been historically underrepresented due to gender bias. Her practice inhabits the experiences of feminist-defined representation; she has been artistin-residence at several regional museums and exhibits in numerous New England galleries.

Erica Imoisi and Perla Mabel

Erica Imoisi is a Nigerian-American creative born in New York City and raised in Boston. She earned her BA in studio art at the University of Massachusetts Boston.

Perla Mabel is an Afro-Caribbean multidisciplinary artist and educator. They were born in Boston and grew up there and in the Dominican Republic. They deeply identify with their Dominican heritage, channeling themes of survival and recalling historical events and figures from their culture.

Whitney Mashburn

Whitney Mashburn (she/they) is a Boston-based independent curator and writer working at the intersection of contemporary art and disability. She holds an MA in critical and curatorial studies, an MA in disability studies, and a BA in history of art and studio art. Their work aims for lasting changes in accessibility through socially engaged art projects.

Dave Ortega

Dave Ortega is a comic book writer, graphic novelist, and educator. Born in El Paso and currently residing in Somerville, Ortega has had his work published in several periodicals, anthologies, and publications, including Tales from la Vida: A Latinx Comics Anthology, New Frontiers: The Many Worlds of George Takei, Irene Book 5, Beautiful/Decay Book 6, and the Illustrated PEN section of the PEN America website. His new graphic novel Días de Consuelo, about his grandmother’s childhood during the Mexican Revolution, is available from Radiator Comics.

Gabriel Sosa

Gabriel Sosa is a Cuban-American artist, linguist, educator, and curator. Raised in Miami and now based in Salem, Gabriel teaches at Massachusetts College of Art and Design and is deputy director of Essex Art Center in Lawrence.

Ngoc-Tran Vu

Ngoc-Tran Vu (she/her) is a one-and-a-half-generation Vietnamese-American multimedia artist and organizer whose socially engaged practice draws from her experience as a cultural connector, educator, and lightworker. Tran threads her social practice through photography, painting, sculpture, and audio so that her art can resonate and engage audiences with intentionality. Her work evokes discourse of familial ties, memories, and rituals amongst themes of social justice and intersectionality. Born in Vietnam, Tran came to the United States with her family as a political refugee and grew up in Boston’s Dorchester and South Boston working-class neighborhoods. She works across borders and is based in Dorchester.

7 ARTIST BIOS

NEW WORKS & ONGOING

AgX Film Collective

Stefan Grabowski is a Boston-based artist and filmmaker, film programmer, and founding member of the AgX Film Collective.

Genevieve Carmel is a filmmaker and film programmer from Cambridge who spends much of her time thinking about how we might reimagine and reshape artist support structures locally, nationally, and across borders.

JayPix Belmer

Jaypix Belmer is a Boston photographer and selfdescribed “visual communicator.” As a Black and Indigenous nonbinary creative, Belmer champions the importance of being seen and emphasizes gaining trust in the communities that the artist photographs.

BOSSCRITT Critique and Curatorial Club

Alfred Dudley III is an artist and educator who received a BFA from the Cooper Union in 2018 and received the college’s Vincent J. Mielcarek Jr. Award for Photography and the Irma Giustino Weiss Prize as well as the Service to the School Award. They’re currently an MFA candidate at Rutgers University’s Mason Gross School of Art.

Juan Carlos Escobedo is an artist who explores his iden tity as a Brown, Mexican-American queer male, raised in a low-socioeconomic community along the US/Mexico border. His work addresses residual class and race shame that comes from living in a predominantly white-struc tured United States, which favors light-skinned individ uals and middle-class and above socioeconomic classes.

Demetri Espinosa is an artist based in Boston. Through the language of abstraction, he examines his lived experi ence growing up as a third-culture kid and the challenges inherent therein. His work deals with notions of identity, belonging, nostalgia, and otherness.

Janet Loren Hill is a New York City-based artist whose paintings, textile, and video work plays with the mallea bility of our perception and asks what’s at risk should we forget our peripheral vision, ignore the gaps, or hold too tightly to the romantic stories we tell ourselves. Her work was recently exhibited at SPRING/BREAK Art Show 2022.

Diana Jean Puglisi is an artist based in the New York metropolitan area whose work explores themes of femi nism, superstition, protection, sexuality, and intimacy. Through sculpture, textiles, and drawing, she transforms and recontextualizes objects associated with women’s work to try to understand it thoroughly and in a context different from its original.

Courtney Stock is an artist based in Boston. Throughout her work, Stock explores material juxtapositions as a way of discussing duality, identity, and shared humanity. Stock draws her materials from traditional realms of painting, sculpture, textile, and craft, though approaches them intuitively and divergently, resulting in the creation of hybrid objects.

Creative Action

Callie Chapman is a graphic designer, projection designer, arts marketer, and choreographer from Boston. As a choreographer of Zoe Dance Company, Chapman incorporates projection design into her work. In addition to implementing video projection internally to the company, she has worked with Odyssey Opera, Prometheus Dance, and Tabula Rasa on projection designs in live performance settings. Chapman holds a BFA from the Boston Conservatory.

Marissa Molinar is a contemporary dancer and director of Midday Movement Series, a grassroots initiative cultivating a new generation of dance leaders. She holds a bachelor’s in environmental science from Brown University with a focus in urban conservation and environmental justice, and she holds a certificate in contemporary dance from the Professional Training Program at Gibney Dance in New York City.

Caitlin Canty makes dances for the stage and screen. She uses elements of theater, circus, and film to explore themes of intimacy, desire, fear, and the absurd. Her dances mine a private human emotional experience in an attempt to break down an illusion of loneliness and posit imaginative possibilities that make noise and glitter. Canty has had work presented by Cambridge Community Television, the Dance Complex, the School for Contemporary Dance and Thought, Third Life Studio, and the Yard. She teaches for Midday Movement Series in Cambridge and at the West Concord Dance Academy in Concord, Massachusetts.

Un-ADULT-erated Black Joy Alison Croney Moses is an artist, craftsperson, educator, art administrator, mother, and Black woman. She cultivates spaces of learning, making, and sharing of art, craft, and design that are welcoming and nurturing of the diverse identities that these spaces are built from. Her professional work weaves together her values and passions. She focuses on empowering youth and adults to use their knowledge, skills, and experiences to make positive change in the world around them.

Tanya Nixon-Silberg is a Black mother, educator, artist, and radical dreamer. Her work is informed by the

8 SPECIAL ISSUE: CFF

intersection of all these identities. Called a “translator,” Nixon-Silberg has the ability to distill concepts of racial justice to young children in ways that help them imagine and take back a world where, with community, they have agency and can take action for change. She has been doing this work for over seven years. Nixon-Silberg’s life’s goal is to make sure that Black and Brown children recognize that racism is systemic, that educators not shy away from confronting systemic racism in the classroom, and that engaging in this work collectively helps us to heal.

Zahirah Nur Truth is a multifaceted artist with an art practice that includes paintings, murals, jewelry, and performance. Through her work, Truth strives to create art that invokes joy, representation, empowerment, and thought. Known as a facilitator, innovator, and motivator, Truth found her true love of the arts in 2005 after taking on the artful journey of motherhood.

Marlon Forrester and Casey Curry

Marlon Forrester, born in Guyana, is an artist and educator raised in Boston. Forrester received a BA from the School of the Museum of Fine Arts in 2008 and an MFA from the Yale School of Art in 2010. He has shown both internationally and nationally. Concerned with the corporate use of the black body, or the body as logo, Forrester’s paintings, drawings, sculptures, and multimedia works reflect meditations on the exploitation implicit through the game of basketball.

Casey Curry (Casey Can, LLC) is a writer and curator guided by the belief that the transformation our world so desperately needs can only come from deep cultural shifts sparked by visionary artists who make fundamental change irresistible. Her research is rooted in thinking creatively about arts administration to uncover what is possible when visionary artists are not just supported by administrative allies, but truly understood and valued by co-creators with complementary skills that level bureaucratic barriers to societal impact through art.

See You in the Future

Sabrina Dorsainvil is a public artist, civic designer, and illustrator. As the City of Boston’s first director of civic design, Dorsainvil has led, supported, and initiated projects and relationships aimed at improving everyday life for Boston residents. The focal point of her efforts has been recovery, public health, civic participation, care infrastructure, and the built environment. Dorsainvil’s artwork focuses on storytelling, unpacking complex ideas, and finding simple yet vibrant ways of celebrating people and their humanity.

George Halfkenny is a Boston native who works to repair the harms of incarceration and addiction in individual lives and the community. As a certified peer specialist, he serves as the director of outreach at Kiva Centers, where

he advocates for access to housing, employment, and other support systems for formerly incarcerated people. Halfkenny is the co-founder of THRIVE Communities in Lowell, has led Restorative Justice circles and workshops, and is working on a memoir.

Melissa Q. Teng is an interdisciplinary artist and writer, often working in community to explore activism, systems, and histories through stories. She is currently the participatory action research artist-in-residence with the Mayor’s Office of Arts and Culture and a graduate student of urban planning at MIT.

Stephen Walter helps support the research, design, and project management of “See You in the Future.” He has worked at many intersections over the years, including Mass / Cass, where he was part of the original City of Boston team that helped design, program, and evaluate the Engagement Center day shelter.

Haus of Threes

Po Couto is a Boston-based queer artist and hair nerd who has specialized in and pioneered gender-affirming aesthetic work within the queer community. Couto is an artist and community organizer focused on grassroots organizing and mutual aid for queer, disabled, and BIPOC communities. They are the founder of Haus of Threes, a queer-collaborative currently based in Charlestown. Couto’s art is facilitating a social movement that creates interactive spaces designed to aid and bring focus, attention, and money to queer communities while uplifting unity and social change.

The Hidden Prompt

Adaeze Dikko is a Nigerian-American New York Citybased creative and storyteller.

Heresa Laforce is a Middlesex County native with a passion for creating and narrative building.

Powerful Pathways and Mattapan Open Streets/Open

Studios

Allentza Michel is an urban planner, artist, policy advocate, and researcher with a background in community organizing. Her seventeen years of diverse experience across community economic development, education, food security, public health, and transportation inform her current work in civic design, community and organizational development, and social equity. She is the founder and managing principal of Powerful Pathways, a public interest consultancy rooted in social practice that blends policy development, urban planning, and social impact design principles.

AWARDEES

PLATFORMS

9 ARTIST BIOS

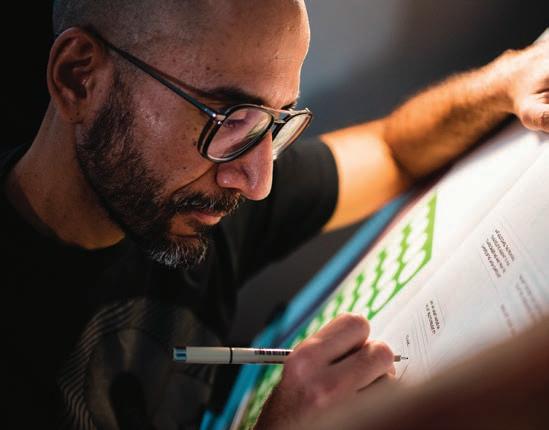

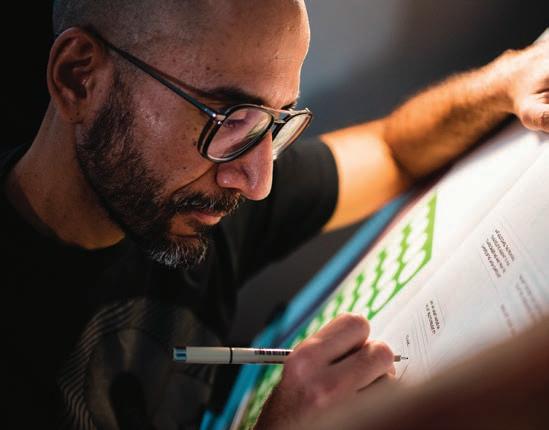

Words by Jonathan Rowe

Drawing from the Past: A Conversation with Dave Ortega

Dave Ortega’s work merges the personal and the historical. A native of El Paso, Texas, and current resident of Somerville, Massachusetts, Ortega is a cartoonist and graphic novelist whose work, including the comic book Battle of Juarez and zine School of the Americas, interrogates and raises awareness about the legacy of European and American colonialism in North and South America.

In his comic series Días de Consuelo, Ortega depicts his grandmother Consuelo’s upbringing in Zacatecas, Mexico, during the Mexican Revolution. In the short comic River, he explores her early adult years in the United States along the Rio Grande. In both of these projects, Ortega’s intimate approach to storytelling exemplifies French historian Lucien Febvre's appeal to document and portray “history seen from below and not from above.” By looking at the past through the lives of everyday working people, Ortega shifts our understanding of history from the hands of the powerful to those on the margins who navigate the tumults of the times they live in with perseverance and love.

As books like Art Spiegelman's graphic novel Maus are increasingly challenged or banned in libraries and schools across the United States over their depictions of history, race, gender, and sexuality, stories that contend with our understanding of the past are more necessary than ever.

10 CONVERSATION

Ortega’s current graphic novel-in-progress, Potosí, which received funding from the Collective Futures Fund, is an important example of history shown from “below.” It focuses on the Spanish Empire’s presence in Bolivia between the 1500s and the 1800s as told by Indigenous peoples whose lives were upended by Spain’s pursuit of political and economic power. Writing in the tradition of speculative fiction and magical realist authors such as Gabriel García Márquez, Isabel Allende, N.K. Jemisin, and others, Ortega illuminates a world forced to confront and survive the brutal imposition of war, occupation, enslavement, and death.

I spoke with Ortega over Zoom about the current state and trajectory of Potosí, what he has discovered about himself while working on it, and what his aspirations for the project are. This interview has been edited for space and clarity.

Jonathan Rowe: I want to start by asking how you got into cartooning and who your influences or inspirations are?

Dave Ortega: I became more attuned to cartooning after art school. When you get in, there’s this pressure to paint, draw, do formal things, and find your place within art history and the art world. That can occupy time until you find something that really speaks to you. Cartooning did that, but it took a bit for me to figure that out. Around 2000, when I graduated from art school, people started to take graphic novels a little more seriously. I read a few, and thankfully some friends pointed me in good direc tions about what to read. After a while I was like, “Maybe I want to do this.”

It definitely wasn’t an option offered in art school, which focused on drawing and painting. To be fair to them, it’s really the only way that they knew how to funnel people. Thankfully, there are more options now for people who want to be creative.

JR: Are there any graphic novelists who have influenced your work or people you use as a reference?

DO: My graphic novel, which came out earlier this year, titled Días de Consuelo, is a memoir about my grand mother’s early life in Mexico. I looked at autobiographical comics, biographical comics, and memoirs that were in the vein of Maus by Art Spiegelman. I also looked at other biographical works like Louis Riel by Chester Brown—he did something graphically and stylistically with that work that I really appreciated at the time. Jaime Hernandez is another huge inspiration for me. He’s somebody who has been working in comics a long time and has been able to lay out this giant cast of characters who have aged with him. Every time I’m stumped by a composition or short story question, I find myself looking at his work.

JR: Let’s move to your current project, which received a grant from the Collective Futures Fund. Could you talk about what this work is about and what stage you are at in its completion?

DO: The work I got a grant for is called Potosí and is named after a town in modern-day Bolivia that was the

center of the silver trade from the sixteenth to eighteenth centuries. The story is from a child’s point of view: a Quichua young man, whose father is deathly ill, is forced into mining, and there is a bit of magic thrown in. The story tries to bring more attention to the greed that fueled the Spanish Empire’s conquest to extract silver from the New World to finance its wars and pay off its debt and how those actions set off the period of globalization we are still living in today.

The work is currently in limbo, and I need to rework it before it’s in any sort of final state. When two administra tors from the Collective Futures Fund visited my studio, they enjoyed learning that I was making a living doing cartoons and were excited after reading my work up to now and by the direction of this project.

JR: What led you to write about Potosí?

DO: As a self-publisher and zine-maker, I’ve always been interested in the Spanish conquest. One of my zines is about Bartholomew de las Casas, a Franciscan friar who traveled with the Conquistadors and criticized their

(all images) Dave Ortega in his studio.

11

Photo by Michelle Falcón Fontánez for Boston Art Review

.

DAVE ORTEGA

treatment of the Native peoples. Another is about the School of the Americas in Fort Benning, Georgia, where the US trained [Augusto] Pinochet’s generals and other South American military and political leaders in kidnap ping, counter-insurgency, and torture. Thematically, it’s in tune with my other work, which raises awareness about what happens when a superpower invades a world they aren’t quite prepared for and the chain of events that it sets off.

When I first read about Potosí, I instantly knew I wanted to learn more about it. I’ve done a fair amount of research on Potosí as a place and how the Spanish used miners as fuel for its silver trade. [The Spanish] worked people until they were exhausted and drained this mountain called the Cerro Rico, which translates as “Rich Hill.” There was a time in the sixteenth or seventeenth century when the population of Potosí was greater than London or Paris and then all the silver was extracted and the glory days were over.

The goal of the book is to tell a story about that world and I feel like there’s a lot of potential with world-building to tell stories that are rooted in a horrific event. A lot of great speculative and science fiction writers are able to do that. I just finished a book by N.K. Jemisin and thematically I want to create a book in tune with that. She’s creating all of these fantastical worlds but also basing them on reallife events and traumas. Even George R. R. Martin’s series A Song of Fire and Ice does the same thing—he’s looking to history to provide examples of horrible human behavior.

JR: This makes me think about Octavia Butler as another example of a speculative writer who takes events from the present or from history and builds them into this imagi nary but not quite imaginary world.

DO: Yeah, that’s true. I feel like a decade ago, and certainly two decades ago when I finished art school, you were made to feel ashamed if these were your sources of inspiration. I think that there’s this pluralism happening now where all influences are on the table and you won’t be shunned for saying science fiction and comics are sources of inspiration for your work.

JR: You mentioned earlier that your novel is in a limbo state and still in the same form it was pitched in. Even though the novel is not yet complete, what has the process of writing it been like? Has there been anything challenging or exciting about this process?

DO: The whole process has definitely been challenging and exciting. I’m writing out a full script, which I typically didn’t do. Usually sketchbooks are my hub for any project. I would sit and lay out scenes and if a certain visual strikes me, then I knew that I would need to capture that within a scene. I’d then write a scene around that visual and see

where it fit within the main story. Setting up an outline and writing out a script was a good first step for me.

I currently have three giant sketchbooks filled with the entire book from start to finish. That’s the project I pitched to various people. Now it’s a matter of taking the feedback I've received and honing it into something better. But I have to say, the process has been good and informative; it informs the rest of my work and can only make for better writing.

JR: What have you discovered about yourself as an artist as you’ve worked on this novel so far?

DO: What I discovered is that for the longest time I didn’t trust my voice. I think you get in these modes where you feel like you can only have a certain kind of success. Part of that has to do with the work that everyone has to do for money, particularly in a city as expensive as Boston.

It’s through a series of really fortunate events that I was able to quit my full-time job, work part time at Lesley [University], and take on freelance jobs. I finally see, now that I’m in my mid-forties, that this is why people do this—it makes your work better. That’s not to say anything against people who do have day jobs. Días de Consuelo was made when I had a full-time job and worked nights and weekends on it. The hustle really helped to shape that book, and I have tremendous respect for anybody’s hustle and whatever they need to make it all happen because there’s not a lot of monetary support out there like other countries that provide for artists.

It’s sad that there’s not more support on a federal level for artists. I think Massachusetts as a state has been really helpful but could do more. They’re limited by the money they get federally. If our lawmakers see how important artists are culturally to this country, then that’ll be a good day, but it’s tough out there for working artists. Not just in the city of Boston, but in every major city. It’s just tough. So what I learned is the true value of my work. I don't take a minute for granted during the day to work on this.

JR: Who have been the main partners or supporters in this project?

DO: The main supporter of all my work is my partner Ken. He’s a food stylist and gets where I’m coming from. We’re both art school rejects, and I say that to refer to what I said earlier in that we never received much encour agement while in art school. We’re that support network for each other now and actively seeking all sorts of new inspirations, whether it be a film at the Brattle [Theatre] or visiting a museum if we happen to be in a city.

Other support networks I have are friends who are cartoonists in the area and just people that you get to

12 CONVERSATION

know, like comic book shop owners, small business owners, or people who run nonprofits. It’s about being in a community; you can’t do this alone. I could sit at my desk all day, but you need to make some actual face-toface time with people so that they think of you first when there’s some project they need help with. So even though Union Square in Somerville is ground zero for develop ment and gentrification, it’s a nice community and I hope it stays that way for as long as I'm here.

JR: Looking into the future, what do you hope the novel you are creating will accomplish?

DO: I hope that it will be a young adult novel and get the right publisher who’s able to see the potential in the story and how it might appeal to young people. The great thing about writing comics for young people is that they get it— you don’t need to sell them comics. That’s exciting and makes the narrative potential a little more open in some ways. In other ways, because you have the gatekeepers of the publishing industry and their entire framework, my experience is that they do tend to want you to work within a certain formula, and that’s where I am with this book. I’ll do all the tweaking I need to in order to make it happen. I don’t say that like I’m compromising my vision. It’s like, I get where they’re coming from. I understand all of it and I hope that it’s something that will lead to better work, an ideal version of the book I hope to see some time soon. //

Jonathan Rowe is a writer and MLIS student at Simmons University raised between Boston, Massachusetts, and Johannesburg, South Africa. His work is published or forthcoming in Callaloo Journal, Boston Art Review, Good Cop/Bad Cop: An Anthology by FlowerSong Press, Harvard Divinity Bulletin, and elsewhere.

13

“What I discovered is that for the longest time I didn’t trust my voice. I think you get in these modes where you feel like you can only have a certain kind of success

. ”

DAVE ORETGA

&

BOSSCRITT CRITIQUE CURATORIAL CLUB

“How long have YOU been looking to experience a positive and uplifting critique?” This was the question we posed to the community of artists who make up the critique and curatorial club BOSSCRITT. For this feature, artists submitted their responses with the detail images of their in-progress artwork. Their words echo the ongoing frustration and fatigue of many art students and artists: Why are we so strapped to find a productive, nonviolent, and inspiring critique? How can we demand more out of our crit experiences for both ourselves and for our peers?

Words by Gina Lindner

Artwork by BOSSCRITT artists. From left to right, Row 1: Alfred Dudley III, Kelly Knight, Leslie Fandrich, Juan Carlos Escobedo, Anna Fubini, Damon Campagna, Janet Loren Hill, and Suzi Grossman. Row 2: Claudine Metrick, Elizabeth Thach, Will Suglia, Claire WeaverZeman, Rachel Morrissey, Claire Weaver-Zeman, Demetri Espinosa, and Arden Klemmer. Row 3: Aja Johnson, Jessica Tawczynski, Juan Carlos Escobedo, Courtney Stock, M E Klesse, Diana Jean Puglisi, Alfred Dudley III, and Barbara Ishikura. Images courtesy of the artists.

14

After the already vulnerable practice of gestating an artwork and presenting it to your peers, there’s nothing worse than feeling torn apart, misunderstood, invisible, and lost by the end of it. Often, the artist is expected to translate offhand, empty comments into something of substance; to explain and defend their identity; or devote their crit time to educating others on the histories or tensions motivating the work. Often, there’s reluctance or fear to engage deeply with issues of race, colonialism, gender, sexuality, accessibility, and other power and social hierarchies, creating critique spaces that are frequently unwelcoming, unsafe, and othering for BIPOC artists, queer artists, and artists with disabil ities. BOSSCRITT is asking: How can we disrupt the Euro-American-centric, white supremacist, elitist, and formalist frameworks that dominate critique and approach the process instead from inclusive, decolonial, feminist, queer, and antiracist perspectives? Despite its defectiveness, critique is crucial to any artist’s develop ment and confidence. Just like a bad crit experience can cut deep and haunt you long afterward, so can a really good crit: leaving you feeling challenged, supported, encouraged, and inspired to run back to the studio.

Craving the peer-to-peer engagement and dialogue she had experienced as an MFA student, BOSSCRITT founder and co-director Courtney Stock began inviting artist friends to her Hyde Park studio in 2019 for playful, exper imental sessions of looking at and talking about each other’s work. More and more artists joined the party, expressing the same frustrations with academic-style critiques and seeking a community of learning and support. As the club grew in size and ambition, longtime BOSSCRITTers Diana Jean Puglisi, Janet Loren Hill, and Demetri Espinosa stepped up as co-directors in 2020–2021, and for the Collective Futures Fund grant invited Alfred Dudley III and Juan Carlos Escobedo as collabora tors and advisors. Since 2019, the group has led forty-five critiques, curated three virtual exhibitions, and cultivated an artistic community not only in Boston but across New England, New York, New Jersey, Texas, and beyond.

With BOSSCRITT, community doesn’t come at a price: No fee or commitment is required to join, only an invest ment in critique and the process. Since the pandemic, the group has been meeting via Zoom multiple times a month, critiquing two to three artists’ work per sixtyto-ninety-minute session. There’s always a mix of new faces and longtime attendees joining, able to offer fresh takes and more nuanced perspectives that come from growing alongside another artist and seeing their practice develop over time. “The fact that we’ve had relationships with each other for a while and we keep showing up for critique is part of that intimacy and privileged insight we have into each other’s work. In this way, I think critique becomes a more powerful, relational, and interpersonal

“I’d like to think BOSSCRITT has made me a better critic. Listening to how a single sentiment can be expressed in a myriad of ways has definitely made me more attentive to my own observations. Now I take a breath and slow down so I can really think about the most constructive way to express an idea.”

—Damon Campagna

15 BOSSCRIT

“BOSSCRITT has been a great source of community support, and I appreciate that there’s a focus on growing together and uplifting other artists in the community through explorative modes of critical thinking.”

—Jessica Tawczynski

“Before BOSSCRITT I did not feel safe entering a critique. I was scarred from school and nervous to get my work out there. BOSSCRITT is a wonderful, inclusive, and energizing space where artists can really connect and learn from one another. We build each other up. BOSSCRITT gave me the courage and confidence I needed to put my work out into the world again… and even participate in critiques that I originally deemed as scary.”

—Rachel Morrissey

“The BOSSCRITT community is by far the most supportive, encouraging, and fun critique space I have ever been in. Yes, fun. The discussions are both serious and playful, and I am always left feeling inspired and excited. It is a special group of artists who are thinking deeply about how to do this right.”

—Leslie Fandrich

dynamic between artists that’s only possible over time and by revisiting,” says Stock. Immediately upon entering the Zoom room, you are struck by the group’s warm, welcoming vibe, opening a safe space to be vulnerable, lean into tough conversations, fail, learn, heal, and have fun, all in good company.

In addition to critique sessions, at the core of BOSSCRITT’s work are two open-source, multi-use, and freely accessible resources to help artists find and personalize their own paths to critique. Both are guided by the core values of safety, compassion, and expansiveness. First, the Critique Menu offers a platter of pre-crit, in-crit, and post-crit questions and practices that “center the artist as the person who’s guiding the conversation, rather than being this passive entity like in the old-school way of receiving feedback,” as Escobedo describes. Instead of feeding you a premade, overcooked meal, the Menu empowers artists to craft their own recipe and experiment with alternate possibilities. For example, instead of verbal feedback, maybe you ask reviewers to sit with their thoughts through writing, or share feelings the work evokes for them through a bodily or auditory response. By leading with questions like “How do YOU want to introduce your work?” and “How do YOU want to receive feedback?” the Menu champions techniques that claim space for ourselves, our safety, and our needs as artists. “We’re definitely privileging the artist’s intention over whatever pedagogical or institutional experiences that they’ve had prior to the moment,” says Dudley. “Not everybody knows what they need from critique, and a lot of people are still figuring that out, given that they’ve mostly been learning all the ways they don’t like it. Instead of experiencing it from the negative, they’re experiencing the opportunity and support to find that newness, to find that intention.”

“There aren’t enough resources out there to help artists lead productive discussions about their work,” says Espinosa. “It’s not something that’s really taught as part of a formal art education.” In many educators’ and artists’ search for a shared language towards better critique prac tices, BOSSCRITT’s Questionnaire is asking the good, hard questions. From “What are the tools you feel you or others lack that are needed to have an expansive critique with substance?” to “In what ways can critique spaces be more accessible for people who have different learning styles?” the questions defy method and rigidity in favor of fluidity, inclusivity, and open-mindedness. As part of their research process, BOSSCRITT has invited artists, educators, and others from the field to contribute their answers, insights, and questions to the Questionnaire and compensates everyone for their labor. “We hope that this will be a model for how institutions could pay the people who are already doing this work unpaid/underpaid,” says Hill. “Not only are we paying people for their contribu tions, but we’re also giving them a support system so they

PROFILE 16

know that—even if they’re alone at their institution— there is a whole interwoven web of us doing this work at other places that they can lean on.”

As artists who can feel siloed in our studios or at our institutions, stuck ever so often—and especially coming out of the isolation of the pandemic—communities like BOSSCRITT are absolutely essential. “What we're doing is more than just critique to me,” says Puglisi. “We’re also talking about the love we have for each other’s work. It's about the care involved in seeing someone’s work move forward. The more you know someone, the farther you can reach into who they are, their practice, and so on.”

By being in community—by being part of a vision larger than itself—BOSSCRITT is making a lasting, evolving impact on the local and broader arts ecosystems. Hopefully, these living, breathing resources will be part of a ripple effect in shifting the way people are thinking about critique: not just good or bad, not confronta tional or violent, but as a place of community, growth, and encouragement. //

To access the BOSSCRITT Critique Menu and Questionnaire responses, or to get involved, please visit www.bosscritt.com/collective-futures-fund

Gina Lindner is a writer, arts administrator, and inter disciplinary artist based between Boston and New York. Her writing has been featured in Boston Art Review, Art New England, Boston Hassle, and various projects by independent artists.

“Leaving grad school was a shock—much of the community there dropped away, and there was no place to go for information on the art scene, crits, and advice when lost in an artistic funk.

BOSSCRITT has been a lifeline and introduced me to many wonderful working artists, been a model for learning how to support other artists, and has just been fun and rewarding.”

—Cynthia Zeman

“Having a supportive community that cares about exploring ideas and art is a wonderful resource for an artist. This group is doing great work to be a support system for its members and share and create opportunities while being understanding of the time and energy that goes into fostering a creative life.”

—Will Suglia

17 BOSSCRITT

How Eli Brown Is

Finding Family Through the Ages

Words by Lian Parsons-Thomason

18

Photo courtesy of the artist.

PROFILE

Eli Brown was looking for community—but not just any community. The thirty-six-year-old artist was in search of intergenerational connections between fellow trans, nonbinary, and gender nonconforming people.

He reached out to two Boston-based nonprofits, BAGLY (the Boston Alliance of Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual, and Transgender Youth) and the LBGTQIA+ Aging Project, focused on programming for LGBTQ youth and elders, respectively. Out of this collaboration, Trans Family Archives was born.

Originally funded by a grant through the Boston Foundation, Trans Family Archives hosted a series of free dinners over the course of a year in 2018. The dinners offered a space for trans and gender nonconforming people of all ages to share stories and build relationships with one another.

“This project began because I didn’t have those people in my life and I really wanted to find older people who were trans that I could spend time with,” said Brown.

During the dinners, participants were offered prompts and icebreakers for getting to know their fellow diners. These prompts included topics such as the language each individual used to talk about themselves and their gender, how that language has changed over time, what friendship looks and feels like, and brainstorming ideas for how to create sustainable connections with those from different age groups.

In one particularly memorable icebreaker activity, diners lined up in order of biological age, then rearranged themselves to reflect their “age” (length of time) since coming out; some had been out for decades, while others were at the beginning of their journey.

“The purpose was to encourage people to think about age as a concept that’s fluid,” said Brown. “To consider an internal age that’s separate from how we appear to others.”

Trans Family Archives is on hiatus while Brown takes time to reflect on what comes next and to focus on their own art

A Trans Family Archives event at Flux Factory in Queens, NY in summer of 2021.

Photo by Sarah Dahlinger.

practice. The artist recently completed a Now + There Public Art Accelerator project, which resulted in the creation of a large UFO-like object called Beam Me Down. Installed in LoPresti Park in East Boston and on view until January 2023, it challenges visitors to consider how queer ecologies could be acts of resistance and resilience against climate change.

Ultimately, it was the pandemic that threw a wrench in the plans for Trans Family Archives; while the online format allowed for greater accessibility, meeting over Zoom didn’t have the same energy as meeting in person.

Brown is looking for collaborators who can help them generate new and diverse ideas, keep up momentum, and ensure that the project is sustainable. Ideally, the team would be intergenerational to reflect the overall goal of Trans Family Archives.

“I need to really get clear on paper, ‘What is this project?’” said Brown. “It’s something I want to commit to, but it’s a lot for one person.”

Improvements going forward could include making the dinners potluck-style affairs rather than catered ones, developing a core group of participants who continue to show up each time, and setting up clear ground rules for engagement so everyone feels heard and respected.

“Dinner as the focal point creates this sort of one-off situation,” said Brown. “Even though the dinners felt like they were going really, really well, we didn’t have a ton of

ELI BROWN

overlap in who was coming. I think the relationships I was trying to build would require more commitment on the part of other folks.”

Brown said they want everyone in the room to feel that they have agency during the event. They also want to include more strategizing and pathways toward addressing generational stigmas.

“There’s still the same isolation and the same violence, all the telltale signs that I experienced when I was coming up,” they said. “I relearn that all that pain is still present for the young people. Even though they might have more of each other and get to see each other in a virtual space, I don’t know how much has shifted or changed for them.”

Brown invited Cat Graffam, a fellow artist and—at the time—exhibitions director at Gallery 263 in Cambridge, to one of the dinners. At first, she was anxious about attending. But when she arrived, she realized that she’d never been in a room with so many other trans people at once.

“You maybe get to see a trans person out in the wild or if you’re in a social situation as part of a larger group, but you don’t get the opportunity to exist with many other trans people in a shared space,” she said. “That’s very comforting because you feel less judged—there’s a barrier removed via the commonality between you and other people.”

An intentionally intergenerational space offers the opportunity to honor one another’s experiences and share what’s changed over time, what hasn’t, and what’s possible.

“One of the benefits for me in talking to older trans people is getting to see that you can have a future,” said Graffam. “Before I turned eighteen, I just really didn’t think I would make it. I never thought I’d make it to thirty. Seeing somebody who is in their fifties and sixties and is trans is a reminder that life doesn’t end when you’re young. Getting to see that as a mirror for your future self is really impactful.”

Brown gathered Graffam, Jessica Mink, and theater artist Mal Malme for conversations about different facets of trans experiences at their respective ages. The intergen erational dialogue was recorded and turned into a sound installation for Brown’s installation Greenhouse and shaped Trans Family Archives going forward.

Though Malme didn’t attend one of the formal dinners, their perspective was formative to the project both through their own personal experiences and because of their educational initiative The Pineapple Project, which performs short plays at schools, libraries, and children’s museums to teach young children about the impor tance of acceptance and being themselves. The value of initiatives like The Pineapple Project and Trans Family Archives is storytelling, said Malme.

Cecilia Gentili, who facilitated the Fall 2020 event at Parallel Project Space in Brooklyn, NY. Image courtesy of the artist.

PROFILE 20

“It’s about sharing stories that I didn’t hear when I was a kid and generating those stories with each other,” they said. “It’s the simplest and most profound form of community and art. I think people hear themselves when someone shares their story, and that brings us closer together.”

As with any community, there have been sticking points and challenges along the way, including those involving language, which can be difficult to navigate in an inter generational space, as vocabulary has shifted over time.

“When I first started figuring out my gender identity, we didn’t even have the words ‘gender identity,’” said Malme. The fifty-six-year-old said they have encountered older LGBTQ people who struggle with understanding nonbinary identities, primarily because there was very limited knowledge around the topic when they came of age.

“Finding space for folks to talk about that is important. Language is going to keep evolving, so we have to find what words fit for the time being. And there might be better words down the road,” said Malme.

They added that listening to others’ stories and finding the connective tissue between one another is a way to be supportive within the community, regardless of the various terms individuals may use.

Graffam, who is twenty-nine years old, said she felt “a little old” among some of the younger attendees, many of whom were between the ages of sixteen and twenty-five. Talking to younger trans people helped to highlight the resources and representation that are more accessible now than when she was growing up.

“It’s frustrating sometimes that [they seem to] get things so much easier than even ten years ago when I came out, but I’m glad they have resources and education and representation,” she said.

Although she is grateful for the positive changes in culture, the emotions are sometimes bittersweet.

“I think it’s a sense of grief—grief for your younger self,” she said. “How would my life have been different if I was fifteen and knew what being trans was? How would my life have played out?”

Brown has found fulfillment in mentoring younger trans and nonbinary people, providing guidance and support.

“That’s such a pleasure for me because I get to hold space for them and ask them about themselves,” they said. “That’s something I just did not have in my life when I was a teenager and in my twenties.”

Graffam said what Brown has accomplished through Trans Family Archives has set an example for the younger generation, showing that it’s possible to be multifaceted and live a full life.

“The conversation around being trans is often so focused around our pain and hurt and being harmed that getting to share trans joy and positivity is refreshing,” said Graffam. “You don’t get to do that often, which I think is one of Eli’s goals with it, too.”

Brown added that they didn’t have close relationships with their grandparents and feel like they missed out on those connections. Projects like Trans Family Archives have helped them facilitate building new relationships with elders in the community.

“I really value my conversations with these elders. It’s special to have a conversation with an older trans person,” said Brown. “It’s heartwarming learning how full people’s lives are and how much energy they have. Being able to live the way they want to live is pretty powerful for me—I never thought I would live this.”

Similarly, Graffam emphasized the importance of honoring those who paved the way for others, such as the generation who lived through the AIDS epidemic from the 1980s through the mid–90s.

“I think really understanding their perspective and acknowledging the extreme hardships that they went through, listening to their experiences about how they were treated and where and how they found community, is so valuable,” she said. “Even if there’s a difference in opinion and respectability politics, it’s important to push that aside to honor the older trans people who have been around the block and know how to survive.”

Thriving as a trans, nonbinary, or gender nonconforming person can be an uphill battle for personal, societal, and political reasons, but projects like Trans Family Archives show that there is nothing more powerful than community.

“Being in a room with people who get it—who understand, who have figured out ways that they’re resilient, every day entering the world that doesn’t see you as you see you—being in community with that is very grounding,” said Malme. “If there’s struggle there, there’s going to be someone who’s going to hold you up.” //

Lian Parsons-Thomason is a Boston-based writer and journalist. Her bylines can be found at iPondr, the Harvard Gazette, and Experience Magazine

21

BROWN

ELI

See You in the Future:

A Promise and Request to Change the Narrative Around Mass and Cass

Words by Matthew Akira Okazaki

Words by Matthew Akira Okazaki

22 CONVERSATION

Group portrait of artists: (left to right) George Halfkenny, Melissa Q. Teng, Sabrina Dorsainvil, and Stephen Walter. Image by Loi Huynh.

Most Bostonians are familiar with the area known as “Mass and Cass.” The area is still pejoratively referred to as “Methadone Mile” by some media reporters, as well as “Recovery Road” or “Miracle Mile.” The territory now gets its name from the major intersection of Massachusetts Avenue and Melnea Cass Boulevard. Yet no matter its name, the dominant narrative around this area today remains one of crisis, trauma, anger, and hopelessness. What would it be if it were told by its own community members of survivors, visitors, and caretakers? Artists Sabrina Dorsainvil, George Halfkenny, Melissa Q. Teng, and Stephen Walter are exploring these questions through a storytelling and public art project called “See You in the Future.”

Their work highlights how the public imagination has entangled Mass and Cass with over fifty years of racialized anti-drug and anti-poverty campaigns. Together, they are collecting honest stories of care, resilience, and hope in the communities of Mass and Cass that don’t make the news, but speak to a more humane world that already exists. This year, they have received several grants to fund their work, which include support from the Collective Futures Fund, the New England Foundation for the Arts, and the Sasaki Foundation Design Grant.

On a hot and humid Sunday, with no clouds or shade in sight, surrounded by speeding cars and endless pavement, Teng and I spent a few hours walking in and around the area designated as Mass and Cass to talk more about this place and the work she and her team are conducting here. Feeling the need to be present on our walk, we chose to keep the conversation to ourselves and with those we met along the way. The following is a condensed version of a conversation that took place a few days later, where we reflected on our afternoon walk.

Matthew Okazaki: Thank you for bringing me out and taking me on that walk last week. It was such a good idea, and a powerful experience. It was a lot to take in. But I think it was important to be there to truly see it. To see how hot it was, the lack of shade, the overwhelming noise, the speeding cars, the tiny sidewalks, the relent less asphalt.

Melissa Teng: It’s a lot different than driving through it. My teammates introduced me to Mass and Cass by walking through it as well.

MO: You mentioned that the original idea for this project, “See You in the Future,” was to run a series of identity, wellness, and photography workshops at the Engagement Center (a low-barrier safe space that provides medical care, snacks, drinks, and access to recovery services), but it’s changed since, right?

MT: Yeah, there were just a whole bunch of assumptions that were made in our initial proposal. Some were things we knew would change after talking with more people living and working here, like the medium of photog raphy or our workshop curriculum. We knew that sched uling would be hard because folks don’t necessarily have a predictable schedule. They may not have phones to

call or text, or money for transportation if something falls through.

The reason why we wanted to work with the Engagement Center was because this was one of the spots where people gather. It was a community anchor point for people to just go get water or use the Wi-Fi, computers, bath rooms. It was also a place where people would just show up, because that’s where their friends would show up. At one point, there were folks giving haircuts and massages.

But then, and we did not expect it, although it’s not all that surprising, the Engagement Center was shut down in the spring and then only allowed to operate on a limited basis.

MO: What happened?

MT: Unfortunately, this follows a pattern of overcorrection as a response to “Mass and Cass.” The Boston Globe reported some knife-related incidents there. Some people were arguing that the Engagement Center was a place where people could go to make drug deals, or where people would be preyed on or attacked, but it’s more nuanced than that. People are fighting for their lives and conflicts are bound to happen, especially

23 SEE YOU IN THE FUTURE

24 CONVERSATION

On the left, a collage depicting Southampton St., showing the men’s shelter across from the fenced-off Fire Dept. Headquarters. The images on the right depict the intersection of Atkinson St. and Southampton St., where people who lived in the Mass and Cass area have been herded after tents were forcefully taken down in January 2022. These images have been compiled by the See You in the Future Collective.

ABOUT THIS PROCESS:

We lined up photos taken by our teammate Stephen Walter in September 2022 with photos taken by Google’s Street View cars, which are archived on Google Maps (adding more blur to faces). Unhoused and recovery communities are often blamed for causing “dirty,” “unsafe,” and “crowded” streets. These photos tell a different story of disinvestment in public space.

Bus stations are removed (first the bus shelter seat goes, then the station itself), street banners are replaced by cameras, and green spaces are neglected and disappear. When elements of public infrastructure (e.g., street lights, trash cans, trees, and signs) are damaged, they are removed, not mended, leading to more barren landscapes. We see an increase in fences, surveillance tech, and police vehicles, pointing to a public realm designed for control. To break the stigma, we need to understand: What really leads to unsafe, dirty, and crowded streets?

25

THE

SEE YOU IN

FUTURE

now that everyone’s been pushed onto one block [after tents were cleared and over 150 unhoused people were offered spaces in shelters in January of 2022]. But there’s this tension of actual violence that harms community members and reported crimes. And it’s important to make that distinction, that some of this is fear-response-based reporting from outsiders versus what is truly dangerous for people who are living there. And this ultimately leads to an overcorrection.

MO: I see the work that you and your team are pursuing. It’s that you’re really trying to tip the scales or start to balance against that kind of mainstream representation.

MT: Yeah. But part of what we were dealing with going in was this question of like, is this even helpful? And is this work even art? We don’t want to go in and be like, yeah art makes everything better, or okay everyone, let’s make a mural. Really that’s all great. And there’s definitely a place for that, and a need for beautiful spaces here. But it feels self-serving if there are all these structural things and compounding injustices that aren’t being addressed or understood.

The conversations really need to happen first, and the art will come. First, we just want to be there.

MO: These conversations, this rethinking of what the actual “project” is, the just being there and sitting with it, I think you were talking about it as this kind of “pre-work” for the work.

MT: It reminds me of the conversation around humancentered design. This is a popular methodology that centers people’s needs as opposed to designing prod ucts. But there’s an inherent problem with a frame work like that, because it forgets that so many people in our communities have already been dehumanized. For example, anyone with a criminal record is immedi ately treated as less-than. They have rights, needs, and privileges stripped away.

There’s actually a lot of pre-work needed before we even think about “centering” design around a certain human experience. It makes this pretty linear and methodical framework a lot more reflective.

MO: I imagine it’s met with some resistance though. How does that work when you get grants or receive funding for this? These kinds of groups and organizations tend to want something in return, a measurable outcome, a report, a mural, a sculpture; don’t they expect “something”?

MT: Yeah. Honestly, tangible outcomes are good for my mental health too [laughs]. But I’ve honestly been surprised by how much our funders get that this presence

and research is also part of it, even if it’s not easily measurable. It’s amazing to meet funders who are inter ested in reframing the question, which for us is, what really is Mass and Cass?

It’s not a formal neighborhood. The shape and size of Mass and Cass changes based on who you ask. It’s one community, but it’s multiple communities. This isn’t a group easily defined by a language, race, language, class, or even housing and recovery status.

MO: The boundaries of the community, they’re fuzzy.

MT: And this one feels especially fuzzy. We wonder what the effects are on this “community” when the social and geographic boundaries of Mass and Cass are being drawn and enforced externally. For us, we’re asking, how would folks who are part of the stable and intermittent commu nities on the streets define their own community?

We think we can get at these questions through conver sations and sharing stories. This storytelling component, that’s what’s really needed, and something we can do as artists.

MO: Again, to tip the scales, or alter the narrative—the alter-narrative.

MT: Right.

MO: So where are your thoughts on this identity or story telling piece? Any idea of where that might take you?

MT: One of our teammates, George Halfkenny, has years of experience facilitating restorative justice circles. We’re planning a few and thinking about workshops focused on other acts of collaboration.

We’re also looking at doing things with audio. Maybe a radio station? There’s such an intense soundscape around Mass and Cass; it’s so jarring and loud. What’s it like to be surrounded by that level of stereo, all day and night? We’re recording audio conversations starting with folks George has known over the years. And in those, we’ll be dealing with that soundscape, capturing people’s voices with the sounds of all those cars and the traffic. We’re looking for archival audio to see if we can bring in some of Boston’s rich social-movement history. My team mate Steve [Stephen Walter] has been building a fasci nating archive of photos and videos from different media sources over time.

There’s a certain level of privacy that audio provides, more than shooting video or photography. It lends itself better when dealing with Mass and Cass because the image and spectacle of it has been so often used in a negative light.

26 CONVERSATION

Finally, we’re thinking about pamphlets and printed material that offer certain messages, which is kind of like doubling down on the billboard idea.

MO: Yes! Let’s talk about the billboard idea.

MT: We’re not sure if we can afford it, but it’s been exciting to look into. We’re thinking about renting out a billboard to display an undeter mined message that will specifically target these two different constituents: the people in and around Mass and Cass, and others who are driving through it. It’s cool to think about a message for these two groups who are entering and moving through the area at such different speeds.

MO: So what’s going on the billboard? Is it a message, a story, a phrase?

MT: There are common phrases that people in recovery communities say to each other. Other people might hear them and think it’s just a nice saying, but it means something different to those in recovery. There’s something nice about this double reading, and double meaning, all in plain sight. I like the idea of having something that can create a feeling of belonging, and for folks in recovery to say, “Oh, that’s for me!”

In many ways, our project is really about creating and supporting a public campaign. But it’s important to point out that the narratives we’re trying to amplify are not our own; they are stories that people who work every day on the streets, or who belong to this community have been saying for years, even decades. As artists, our hope and task is to support these narratives and help them reach who they need to reach.

MO: And when is this new chapter of your project—this campaign of sorts—starting up?

MT: We’re working on it now, but you can follow our progress on our website at seeyouinthefuture. org. It’s currently a little quiet, but we are excited to share news soon. //

Matthew Akira Okazaki is an assistant teaching professor at Northeastern University’s School of Architecture, a practicing artist, and founder of the design practice Field Office LLC. He is currently based in Boston.

Group portrait of artists: (left to right) Stephen Walter, Melissa Q. Teng, George Halfkenny, and Sabrina Dorsainvil. Image by Loi Huynh.

“

27 SEE YOU IN THE FUTURE

The shape and size of Mass and Cass changes based on who you ask. It’s one community, but it’s multiple communities. This isn’t a group easily defined by a language, race, language, class, or even housing and recovery status.”

AgX Film Collective Fosters Community for Filmmakers

Words by Olivia Deng

Stepping into AgX Film Collective in Waltham feels like being transported to a different era—discontinued Bolex cameras, flatbed editors, manuals from the 1970s, a dark room for developing film and a screening area to show films, occupy the space. Established in January 2015 with about thirty members, AgX is equipped with everything you need for photochemical filmmaking. “There are so many schools in the city that teach film, but I found when you graduate, you lose access to those resources, you lose access to the community, and things feel very fractured,” said Stefan Grabowski, founding member of AgX. To fill the void in the Boston filmmaking community, Grabowski hosted a meeting of local filmmakers to discuss formal izing a film collective where members could pool their knowledge and resources.

Today, AgX hosts skillshares and screenings all while keeping their expansive, workshop-like space open for members to work on their projects. While the COVID-19 pandemic initially put a halt on their public screenings and the events that supplement their income, AgX is now in a position to ramp up programming, thanks in large part to the Collective Futures Fund grant they received. Grabowski said that the studio at 144 Moody Street in Waltham is crucial to AgX’s success, and the grant helped them keep the space and fund other operating expenses. While Grabowski said that the collective could potentially

exist without a physical space, it would come at a great loss to the AgX and filmmaking community.

“We could exist without a physical space in a much looser way, but we would lose a lot to not have that space, because it allows for the community to come together, and it allows for us to have a greater number of phys ical resources,” Grabowski said. “We were able to put [the Collective Futures Fund grant] toward these kinds of operating expenses. Space is so essential for the commu nity to come together and for us to house the physical resources that we have, which are open to our members and the public when we do workshops.”

Being a filmmaker comes with unique challenges, according to Grabowski. “Not everyone has the projector to play it, so sharing a film print isn’t feasible in the way that a fine artist might be able to sell a painting. It’s a very nonprofitable medium in the financial sense,” he said. “Filmmakers, especially those making personal artistic work, are making their art at a financial loss for themselves. Success is reliant on people coming out to an organized event to actually see the work.”

In this sense, AgX’s screening area is just as pertinent as the equipment. “People can come watch things that are more marginal or fringe that you definitely would never

(both) Inside the AgX Film Collective space in Waltham where gear and equipment are available for members to use.

Photo by Olivia Deng.

(both) Inside the AgX Film Collective space in Waltham where gear and equipment are available for members to use.

Photo by Olivia Deng.

PROFILE 28

see at a multiplex, and you’re less likely to see at the smaller arthouse type venues. We can open up our space for the public to come watch things for free or donation.”

For example, the collective recently hosted Los Angelesbased Sri Lankan filmmaker Rajee Samarasinghe at their space for a screening. “I’ve been starting to program some screenings of friends of mine who are filmmakers as they’re coming through,” said filmmaker and AgX member Kyle J. Petty. “Especially after we’ve had two years of all watching films on a laptop screen, or, you know, isolated in our houses, we can bring people in here and show stuff on film.”