BOTANY

A project by Border Crossings’ ORIGINS Festival With the support of the National Lottery Heritage Fund

This publication is distributed free of charge and is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

You are free to:

Share — copy and redistribute the material in any medium or format. Adapt — remix, transform, and build upon the material for any purpose. Under the following terms:

Attribution — You must give appropriate credit, provide a link to the license, and indicate if changes were made. You may do so in any reasonable manner, but not in any way that suggests the licensor endorses you or your use. No additional restrictions — You may not apply legal terms or technological measures that legally restrict others from doing anything the license permits.

This publication should be mentioned as follows: A. Perdibon (ed), BOTANY BAY. London, Border Crossings 2022.

The publishers have made every effort to secure permission to reproduce pictures protected by copyright. Any omission brought to their attention will be solved in future editions of this publication.

ISBN-10: 1-904718-13-2

ISBN-13: 978-1-904718-13-0

EAN: 9781904718130

Border Crossings is a certified as a carbon neutral business by Carbon Neutral Britain. Registered Charity No. 1048836.

Foreword by Michael Walling

Introduction by Marine Begault

Chiswick House Plant Stories

Pineapple by Ruth Todd The Three Sisters by Rosemarie Clifton Tobacco: Protector. Healer. Killer. Saviour? by Tracey Fahy Dahlia by Aidan Pike Sydney Parkinson: Endeavour Artist by Victoria Timberlake

1. We Belong To The Earth, We Do Not Own The Earth Chiswick Secondary School, London Wiraqocha, the Source of Life, La origen the la vida: José Navarro

2. We Listen and Observe Hurst Drive School, Enfield Honeybee Tree: Jasmine Coe

3. We Work With Nature, Not Against Oswald Road School, Manchester Maori Artworks: Frederick Worrell

4. We Look Forward Seven Generations Cavendish Primary School, London The Tree of Life: Huitzomitl

5. We Respect And Show Gratitude Medlock School, Manchester Labyrinth “Heyv Ekvnv, This World”: Melinda Schwakhofer

Editor: Anna Perdibon

Designer: Joanna Wojcicka

Printed on recycled paper www.botanybay.org.uk

BAY I Heritage responds to Colonialism, Climate Change and Covid

The BOTANY BAY project was conceived in the thick of the COVID-19 pandemic. Locked down in their homes, people were longing for contact with the natural world. Young people and children in particular were desperate to be in green spaces, amongst trees and flowers. It seemed as if the world was telling them something, reminding them that humanity’s systematic destruction of natural habitats was the root cause of the pandemic, and that this destruction was continuing, even when schools, businesses and cultural events were completely closed down. It was as if Nature was calling the young to take action: the pandemic was only a warning of the much greater calamity that was to come, in the shape of Climate Change. We have to think and behave completely differently in relation to our environment. We have to understand that it is not there simply to serve human whims, but is a delicate and balanced system composed of many beings, only some of whom are human.

This way of seeing the world may feel very alien to Western, capitalist minds, but it is deeply embedded in the cultures of Indigenous people across the planet. These cultures, often dismissed as “primitive” or “undeveloped”, are profoundly sensitive to their place within the ecosystem, and the need for reciprocal relationships between humans, plants and animals in order to maintain an equilibrium. If we are to avoid further catastrophes, we need to learn from Indigenous people in the ways they cultivate, harvest and eat plants. We need to recognise that plants and people are mutually dependent.

For Europeans, that means addressing our responsibility for the ongoing colonisation of Indigenous lands: a process that began with the invasions of the “age of discovery”, continued through histories of empire, and is seen today in economic domination of global resources, exploiting land, plants and people. By studying the heritage of plant migrations, we can begin to understand how we got into this mess, and so perhaps begin to see how we might get out of it.

We have been deeply fortunate in receiving the support of many Indigenous knowedge keepers during the course of the BOTANY BAY project. This booklet contains some of their wisdom, and there is much more in the project’s video archive. Listening to these voices, the young people involved in BOTANY BAY have begun to practice a different approach to gardens, cultivation and food. They have surrounded their gardening and cooking practices with respect, ceremony and wonder. They have come out of their locked down homes into open green spaces, and begun to learn how best to live in them.

Enfield

October 2022

Pumpkin Photo: Eva Bronzini

Pumpkin Photo: Eva Bronzini

I was one of those people who that attempted to grow plants (semi-successfully) on their balcony during the Covid-19 pandemic. I joined this project with little experience in horticulture or food growing, but with a strong desire to connect with and learn from nature. And indeed, learning and sometimes ‘unlearning’ has been at the centre of my experience. Like the children, I have tried to listen and observe and challenge my ideas of what the gardens or the project should look like. I have a tendency to want to see things in a linear way. I like things that look tidy, plants in rows, herbs in one corner and flowers in another. In fact, in listening and observing, I’ve learned that the beauty of nature, and of working with children and young people, is that there is another logic. One that cannot be dictated by a project plan or my desire to control. This rhythm is in tune with something else; sometimes the changing seasons, sometimes the children’s moods, and sometimes the spirits of these beings living and growing in their gardens.

I’ve felt so much joy in working with these children and young people who want to believe in the magic and mysteries of nature and who so openly and readily believe and listen to these beings, seen and unseen.

Sunflower

Photo: Jennifer Moore

Sunflower

Photo: Jennifer Moore

WINTER – Preparing the ground. It is cold. We stay indoors and build the foundations for what is to come.

• The project is launched in the schools: Hurst Drive Primary, Cavendish Primary and Chiswick Secondary in London and Medlock Primary and Oswald Road Primary in Manchester.

• Each school selects a year group to lead on the project with the notion that their experiences and learning will trickle down and across the rest of the school.

• School staff and project volunteers attend training sessions focusing on the botanical and horticultural heritage of Britain, and in particular its relationship to the heritage of colonialism.

• Students are invited to bespoke learning sessions created with our heritage partners, The Garden Museum in London and The Manchester Museum. They learn about some of the migration stories of plants and their intimate ties to colonialism. They meet Indigenous people, experience their stories, music and ceremony and hear about the role that these play in their relationships with Mother Nature.

• Resources exploring Indigenous approaches to nature and gardening are created as the students start to think about what they would like to grow in their school gardens.

SPRING – An explosion of energy and vibrant colours. We are busy planting outside.

• A group of students in each school creates a gardening club to design and plant a garden inspired by the Indigenous people they meet and the stories they hear.

• The Three Sisters involving Corn (the eldest sister), Bean (the middle sister) and Squash (the youngest sister) is very popular and planted in all the gardens.

• Amazon Visions – a puppet show exploring the richness of animal life and connections between us all by Quechua theatre-maker José Navarro is brought into each school stimulating conversations around the diversity of plants and how the ways in which we live our lives here can affect the smallest creatures in places we may never visit.

• Children think about their aspirations for their garden: how do they want people to feel when they enter? Who will care for it? How can they ensure it is respected by all?

SUMMER – It is hot and dry. We reflect, take stock and share learning.

• The students nurture their garden. They observe as it changes daily. Poetry and story writing sessions take place in all of the schools.

• The children visit gardens that are local to them. What can we learn from these more established gardens? How do they connect to these spaces differently now that they are caring for their own?

• We check in with all of our partners and collaborating artists.

• We host volunteer training sessions with our partners in Manchester and London.

• We recruit volunteers to support the watering of our gardens (it is a hot summer!)

AUTUMN – Seed saving and legacy. The pumpkins are ripe; we harvest the food and give thanks.

• Indigenous artists are commissioned to create artworks for each school garden as a legacy for the project and to root the gardens in contemporary Indigenous cultures.

• Led by Indigenous practitioners, the students harvest and cook what has grown.

• Students cook the corn-based Mesoamerican dish Tamales. All parts of the corn are used to make this. The food is treated with the same respect as when it was growing. Stories and song are central to this relationship.

• The students celebrate and give thanks to their gardens! They bring what they have learned and experienced together in celebratory events with their families and communities. Poetry, storytelling, music, dance, ceremony and sharing food are central to showing their gratitude.

Dahlias

Photo: Karolina Grabowska

Dahlias

Photo: Karolina Grabowska

An integral part of BOTANY BAY is the collaboration with Chiswick House and Gardens, in West London. A heritage programme was launched for re-labelling plant stories in a way that would explore the entwined heritage of British colonialism and horticulture with Indigenous histories.

The Kitchen Garden volunteers took on research into plants that are common in our daily lives and into the accounts of British botanists, cultivators, collectors and illustrators. They explored the origins and relationships of pineapple, corn, pumpkin, squash, bean, tobacco and dahlia with Indigenous peoples and their ancestral lands, while tracing their colonial journeys. Particular emphasis is laid on how, when and where these plants arrived and were planted in England, and to their socio-historical meanings. This research has led to new labelling approaches across the gardens.

“How can we translate the way Indigenous Americans look at the land? Native people look at the land and everything on the land, especially plants, as relatives. They are directly related to us, just like our human relatives… This is a kin-centric relationship. Everything is focused on family. We are related to each other.

This relationship is built on sharing breath. We exhale carbon dioxide that plants especially like to inhale. And they play a direct role in providing nutrients, oxygen, food for us. So it is a really unique and powerful relationship that many other people recognise. Ecologists realise that this is exactly what happens everywhere on the planet. We are in constant direct connection with plants. They are our relatives. And in some way, we are those plants. Those plants are us. Because we share this kincentric relationship through breath, through energy. Iwìgara means exactly this: sharing breath.”

This tropical fruit is grown commercially and exported by many different countries, although it originated from South America. The pineapple has a very long and interesting history and is remarkable in botanical terms. Somewhat surprisingly it has several links with Chiswick House and Gardens around what is now called the Walled Kitchen Gardens. A member of the Bromeliacae family, pineapple has managed to retain the name given to it by Indigenous people in South America both in the Linnean classification of plants and in other countries where it is grown. It is a perennial shrub of between 1-1.5 metres in height. It stores water in its waxy leaves so is able to endure periods of drought. To thrive it needs high temperatures. Its juices contain an enzyme that digests protein and whilst it is delicious, it is inadvisable to eat it in large quantities. It is used as a natural anti-inflammatory remedy to help relieve gastrointestinal and respiratory issues, and has high levels of Vitamins A, B and C.

The Tupi-Guarani were the first people to encounter the pineapple in the Amazon Forest. They called it ‘anana’, which means ‘excellent fruit’, to which in the Linnean classification ‘comosus’, ‘leafy’, was added. The plant originally came from Brazil and Paraguay, although the exact location remains under debate. The Tupi-Guarani domesticated the wild pineapple over the centuries since 2000 BCE. Rotten pineapple was used to poison the tips of the arrows. Wine was made from the fruit and the leaves were used as fibre for rope and bow strings. Lately, pineapple cultivation spread to other parts of South America and the Caribbean. The Portuguese encountered the Tupi-Guarani on their expeditions to the New World.

The pineapple, started its journey overseas when Christopher Columbus landed on an island he named Guadeloupe during his second voyage in 1493. Setting sail in April 1496 Columbus took some pineapples with him: all but one had rotted by the time he reached Spain. However, King Ferdinand was impressed by its qualities. The Portuguese, followed by the Spanish and the English, introduced the pineapple to east and west Africa, to India and China. The pineapple was probably introduced into England during the Protectorate, with one being sent to Cromwell. Because he thought it had Catholic and regal overtones, pineapple was not favoured. Such impressions changed with the accession of Charles II, to whom pineapple was presented on the 9th August 1661 –as reported by the diarist and horticulturalist John Evelyn. The first pineapple believed to have been grown locally was by a Dutch gardener, Henry Telende, in Richmond around 1714. It was the advancement of glasshouse technology –use of a spirited thermometer, tanners bark and horticultural experience– that enabled the pineapple to eventually be grown at great cost in this country. An expensive luxury and a frenzied fashion for 150 years, the pineapple became a symbol of wealth and the Empire, and a metaphor for industrial growth.

The walled garden at Chiswick was originally part of the garden of Sir Stephen Fox (1627-1716), courtier to Charles II and financier. Detailed research by Sally Jeffery into Fox’s garden demonstrates that there was an area called the Barbados ground. Meanwhile next door at Chiswick House itself Lord Burlington employed a gardener, Henry Scott, who later became a nurseryman specialising in growing pineapples in Weybridge.

Burlington’s great grandson, the 6th Duke of Devonshire (1790-1858), bought what had been Sir Stephen Fox’s garden in 1811. He built the large conservatory with which we are all familiar in 1813 and had pineries at each end of it. He employed Joseph Paxton (1803-65) as his head gardener at Chatsworth. Paxton became an expert at growing pineapples and building glass houses.

Companion planting is the technique of growing plants closely together for mutual benefit. Perhaps the most famous example is the Three Sisters: maize (corn), beans and squash. This intercropping method has been studied and described by scholars in anthropology, history, agriculture and food studies.

Planted in rows of mounds, the Three Sisters protect and nourish each other in different ways as they grow and provide a solid diet for their cultivators. Maize provides a stalk for climbing beans. Beans, by housing the rhizobium bacteria, help replenish valuable nitrogen in the soil. Squash grows along the ground with its large leaves: blocking the sun, it reduces water loss in the soil and prevents weed growth. There are layers upon layers of reciprocity in this type of garden: between the bean, the corn, the squash and the people. This technique spread from Mesoamerica northward over many generations eventually becoming widespread throughout North America. Indigenous farmers saved the best seeds for the following season resulting in a wide variety of cultivars suited for the environments in which they were grown. Much of this diversity was lost as Indigenous nations were forced out of their ancestral lands by early European settlers and later mainstream agricultural practices.

The Haudenosaunee (Iroquois), with their matrilineal democratic society, considered the Three Sisters to be divine gifts and the physical and spiritual sustainers of life. Some versions of their legends involve the crops personified as three women who find out that they are stronger together.

In rural Mexico maize is soaked and cooked in an alkaline solution and usually lime washed and hulled. As a result, it is more easily ground and its nutritional value is increased with flavour. The crops provide a complete nutritional diet. Maize is relatively high in calories but low in protein. Squash provides important vitamins and minerals and its seeds are high in protein and fatty oils. Beans supply protein and necessary amino acids missing from maize and squash.

All pumpkins are squash but not all squash are pumpkins. Squash is believed to be the oldest cultivated food in North America, with cultivated pumpkin seeds having been discovered by archaeologists in the highlands of Oaxaca, Mexico, dating back 7,500 years. Squash was eaten by the Pueblo tribes and became one of the Three Sisters of Milpa (field) cultivation, a self-sustaining farming system developed by the Mayan Civilization and still used in parts of Mexico. Squash was dried and stored and then rejuvenated in winter. Seeds were removed, dried, roasted, spiced and added to nuts and fruit. Blossoms were also a popular food, fresh, fried and dried. Hard shells were used to store water.

Millions of tons of squash are grown worldwide and many varieties have been grown in the Chiswick Kitchen Garden. Almost all can be eaten or used. Trailing near the ground or twining upwards with curling tendrils, squash is a blanket term applied to dozens of varieties of vegetable, including pumpkins, acorn squash, butternut squash, gourds and zucchini. They are vine grown and ripen from late summer through the autumn.

Today, Indigenous people in the USA are working to reclaim indigenous varieties, to share traditional knowledge about agriculture and to pass it on to younger generations in collaboration with academic institutions. By acknowledging that monocropping industrial agricultural systems harm the environment, rural communities and human health alike, universities are assisting the communities in carrying out research projects on the intercropping benefits for the plants and the soil. The U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Research Service launched the United States Three Sisters Project as a new educational outreach initiative to mobilise ideas, foster careers in agricultural science and educate the youth about farming practices.

Tobacco is a very misunderstood plant in Western culture. Many people associate it with addiction and death, which is not surprising considering it’s one of the top killers in some countries. But for thousands of years, Indigenous cultures in the Americas have worked with tobacco as a medicine and consider it a great healing plant. While there is some danger associated with it, in most cases tobacco is a revered, powerful medicine that has been an essential element in the ceremonies of many native communities and taken on many sacred roles throughout those cultures. It is understood that if used in a positive way it has the power to heal and protect, but if abused, it can harm and hurt. A gift of traditional tobacco is a sign of respect and may be offered when asking for help, guidance and protection or if you take something from the earth, like a plant.

‘Helper’ and ‘protector’ are interesting concepts, particularly in relation to tobacco’s changing reputation from ‘killer’ to ‘saviour’. Tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum) is a crop used to produce cigarettes. We now have ample scientific evidence that smoking is harmful and some major cigarette companies are committed to ending smoking while looking at new possible uses for tobacco.

Modern science frequently discovers how to use plants to treat illness, yet this knowledge is often already held in Indigenous tradition and has been used for thousands of years. Big Tobacco is now exploring New Plant Breeding Techniques to make high value substances from tobacco plants for medical, pharmaceutical and cosmetic purposes. Scientists are using technologies to produce vaccines, antibodies and other health-promoting substances.

Using tobacco to make vaccines could revolutionise how vaccines are made and distributed.

The COVID-19 pandemic exposed glaring gaps in the world’s current vaccine producing capabilities. Big Pharma continues to sell the vaccine to wealthy countries to make the highest possible profit, pushing developing countries to the back of the queue. Only a handful of countries have the technology, resources and funds to make vaccines. The solution, some scientists think, is using plants to manufacture vaccines that can be produced in bulk, rapidly, in the field, which would be cheaper and more widely accessible to rural, hard-to-reach communities and in countries with limited infrastructure. So far, tobacco plants have been used in experimental treatments for Ebola, but currently there are no plant-based vaccines available for human use.

While I completely endorse getting vaccines to as many as possible, I worry that people in these poorer countries will become guinea pigs for testing these new plant-based vaccines.

Furthermore, when crops are grown to yield profit, the outcomes are often negative, both for the health and sustainability of the environment and for local populations. As demand increases, the grip of these corporations could erode local crop growing systems, which have been mostly healthy, sustainable and fair for millennia. So, if we combine Big Ag with Big Tobacco, will that be a better and fairer system than Big Pharma for producing and distributing vaccines to poorer countries? If these industries’ historical reputations are anything to go by, it’s doubtful.

• There are more than 70 different species of tobacco, belonging to the Solanacae family (related to the potato and tomato).

• The first arrival of tobacco in England is believed to be 27th July, 1586 when Walter Raleigh brought it from Virginia.

• John Rolfe (b.1585), an early English settler of North America, is credited with the first successful cultivation of tobacco as an export crop in the Colony of Virginia, in 1611. Growing tobacco required hard work and labour and many people were needed to work the fields. Servants met the manpower needs at first but later slavery became entrenched in Virginia, where the tobacco was grown, for the labour force it provided the colonists and turning tobacco into a profitable crop for the colony. Rolfe married Pocahontas, daughter of Wahunsenacah, paramount chief of the Powhatan in Tidewater, in 1614.

It is likely that Rolfe acquired the knowledge to become a successful tobacco grower because of his family connections to the Powhatan. In 1616, he brought his wife and son to Brentford, where they stayed in the grounds of Syon House.

• In the 17th century, tobacco was used instead of money, as it was so highly valued.

The origins of the dahlia are to be found in Mesoamerica, where it thrived in mountainous areas at an elevation spanning between 1,500 and 3,700 meters. The Aztec and Toltec civilizations cultivated this flower for millennia. Its name is “Chichipatl” in the Toltec language, and “Acocotle” or “Cocoxochitl” in Aztec. According to the various translations of Spanish colonisers –such as “water cane”, “water pipe”, “water pipe flower”, “hollow stem flower” and “cane flower”– these indigenous names refer to the hollowness of the plant’s stem.

In their original indigenous contexts, dahlias were grown as a food crop, but this use progressively died out after the Spanish conquest. The edible parts of dahlias are tubers and petals. Edible dahlia tubers are still a somewhat common food in parts of Mexico, but it is debated how much of a role they have played in the human diet in the past. They have probably been used irregularly as an emergency food following the introduction of corn.

the Pima people of Arizona and Sonora included Dahlia coccinea in their traditional diet, at least as a famine food. In traditional Aztec medicine, dahlias were considered as a treatment for epilepsy, but this therapeutic use is still disputed. The hollow stems were used as a tool for carrying water.

Declared the national flower of Mexico in 1963, the dahlia is undergoing an ongoing revitalization among the local Indigenous communities. Several cultivars in Mexico are grown for and used for recovering and promoting traditional cooking.

The tubers can be treated like a sweet potato, with their flavour and sweetness improved when stored in the soil or in cold, high humidity environments –though the skin is particularly unpleasant and should be peeled. The tubers contain a high amount of inulin which can break down into fructose. Before the discovery and introduction of insulin, it was inulin that was used as a diabetic treatment. However, inulin is not easily digested, and may cause unpleasant gases if eaten in high quantity. Roasted tubers were used in the 20th century to make Tuber Dacopa, a paste that can be dried, ground and used as a coffee substitute or for preparing a sweet syrup.

Dahlia

Photo: Iago Joseph

Dahlia

Photo: Iago Joseph

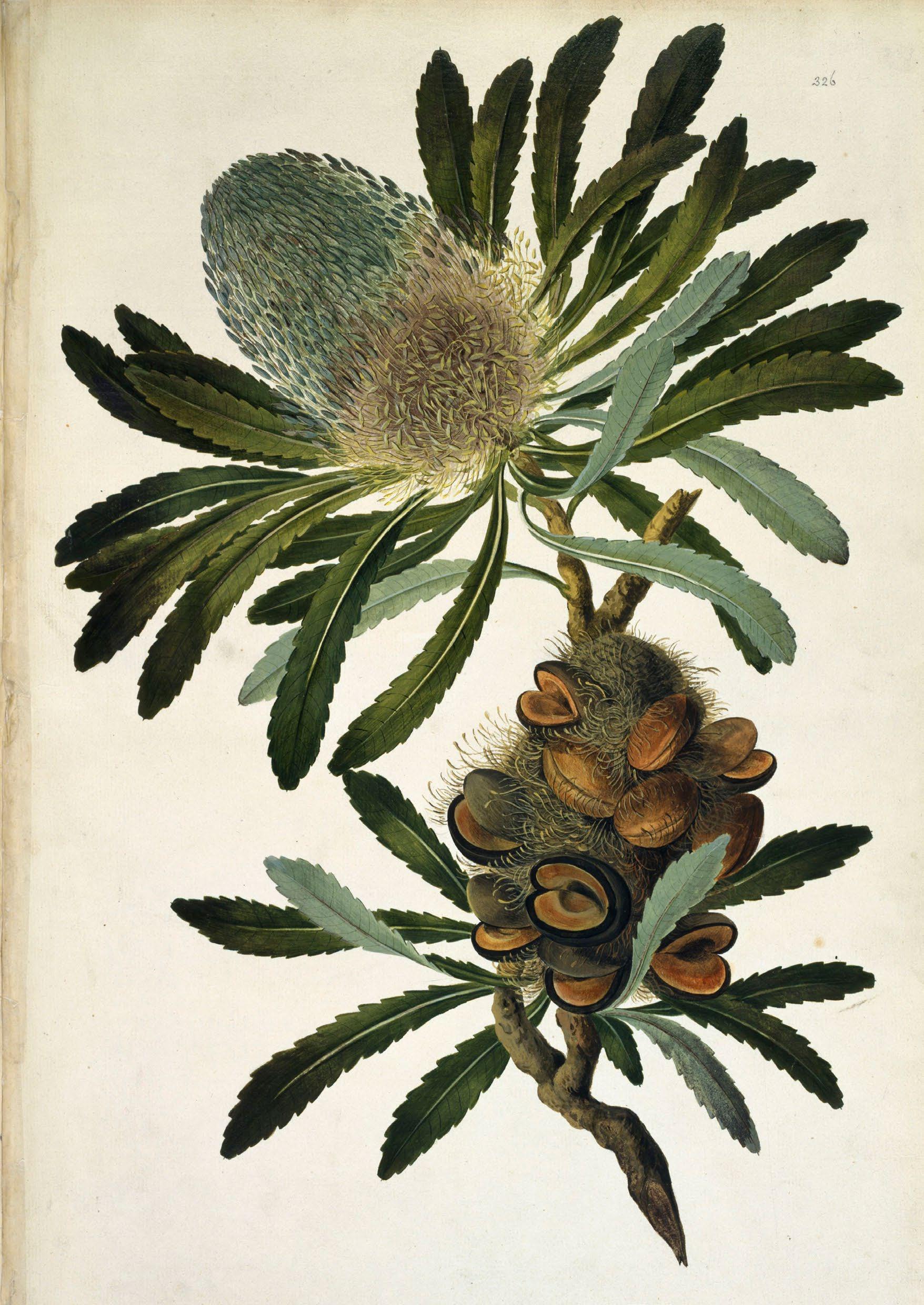

J.F. Miller. Banksia Serrata, Finished drawing after Parkinson original sketch, Library and Archives, Natural History Museum, London.

J.F. Miller. Banksia Serrata, Finished drawing after Parkinson original sketch, Library and Archives, Natural History Museum, London.

Botany Bay, Australia is half a globe away from Chiswick House, but, surprisingly, the story of the ship Endeavour’s round-the-world voyage began, in part, 2.5 miles down the road in Hammersmith, where the Olympia Exhibition Hall now stands. It was here, at the internationally famous Kennedy and Lee Vineyard Nurseries, that Joseph Banks, botanist and patron of the Endeavour voyage, discussed with Lee appointing a botanical illustrator for the voyage. Banks and Lee were fellow plant experts and collectors. New plant discoveries were exciting and important. Wealthy people wanted to show off their fortune and good taste with the latest beautiful and unusual plants. Botanical explorers searched for a special ‘discovery’ which could make a fortune - like the tulip, nutmeg, or tobacco - or establish a scientific reputation. Since no plants collected could survive the three-year voyage, it was necessary to illustrate them before they wilted or faded and then to preserve the specimens for identification and the seeds for later propagation.

James Lee suggested twenty-three year old Sydney Parkinson (1745- 1771), a Scottish Quaker like himself, who had proved his skill and hard work during his three-years employment. For this expedition, however, Banks also required that an artist be able to withstand the hardship of several years at sea, to work fast and on a moving sailing ship. Parkinson rose to the challenge and, in the course of the expedition (1768-1771), exceeded all Banks’ expectations, producing 952 pencil drawings and complete watercolours of plants and hundreds of other natural history illustrations.

Parkinson, who one botanist referred to as ‘Shy boots’, was popular among the crew, keeping his good humour even when a wave hit the ship, upsetting him and his colours, or when the flies ate his fish specimens and the wet paint on his illustrations. Among the illustrations was the legendary breadfruit of Tahiti, which Parkinson called ‘the staff of life to these islanders’ and which Banks reckoned would make a cheap food source for the slave plantations in the West Indies.

On the homeward voyage from Australia, the Endeavour struck the Great Barrier Reef, yet managed to make it to Java for repairs and further plant collecting. Unfortunately, Java’s canals were polluted and many previously healthy crew members died of dysentery, including twenty-six year old Sydney Parkinson, who was buried at sea. Back in London, the seeds from the voyage went to Lee and others for propagation - including the newly ‘discovered’ Banksia - and eventually the specimens, together with Parkinson’s drawings, went to the Natural History Museum London. Banks commissioned engravings of these illustrations for his masterwork, “Banks’ Florilegium”. Although never printed in his lifetime, these pristine plates of 743 illustrations were discovered in a cabinet in the Museum’s Botany Archives 160 years after Banks had donated them! From 1980 – 1990, a limited edition of 100 sets of the plates were finally printed and offered for sale.

Five Gardening Principles were developed by the BOTANY BAY team in accordance to the dialogues and teachings of Indigenous people involved in the project. They were used as a framework to guide students, teachers and volunteers in their garden designs and planting decisions.

Within each Principle you will find an overview of meanings, understandings and behaviours toward plants and nature in Indigenous worldviews. These emerged from interviews and conversations with Indigenous American, Australian and Maori ethnobotanists, gardeners, storytellers, anthropologists, curators, art historians, actors, artists, educators and activists who engaged with BOTANY BAY, both on the ground in school gardens and online. Each section is further illuminated by citations from the interviews, that can be also found in the online video archive of the BOTANY BAY project.

Five Gardening Principles, five schools, five artworks in the gardens. A description of each school garden with details about the plants cultivated, gardening and creative activities, and engagement and feedback of the students is embedded in each Principle. Together with the stories of the school gardens, the artworks created by Indigenous artists living in the UK are presented. The artworks in the gardens form a complementary and nourishing way to nurture and celebrate the reciprocal relationships of care with plants along with gardening.

“Through just sitting among the plants and watching them you learn so much. And this is part of modern culture, modern society that really needs to shift. We are so inundated constantly through social media, television, movies, with one idea after the other that we don’t have time to stop. We don’t have time to sit with a chilli plant, or with a tomato plant or underneath an elm tree or a pine. Or just being with the tree or the plant. Or breathing and just being. We should approach to plants in that way.”

Enrique Salmon, Raramuri ethnobotanist Pineapple

Photo: Jose Grjalva

Pineapple

Photo: Jose Grjalva

When Europeans landed on the shores of the Americas, Australia and New Zealand, they encountered communities following a radically different worldview: humans do not own the Earth, but rather belong to the Earth. Despite their many different visions, nations and ecologies, Indigenous people across the planet share such an understanding of the world and of our role in it. We are all part of nature, jointly with the land, water, air, and with the animal and plant people of a place. We are all interconnected, sharing the same breath. So, instead of seeing us, humans, with our culture, as separated from the rest of the world, Indigenous people understand us as part of nature, living in relationship with other beings. In this way humans are intimately bound to a local landscape, and have to learn how to nurture the relationship with the land and its non-human inhabitants. This intimate relationship with the Earth is celebrated in stories, myths and ceremonies.

Every culture has a Creation Story. The Omaha Creation Story starts with the birth of humans in the water and traces their interdependence with the rest of the world. The first humans are naked and do not know anything of their environment. They slowly engage with plants, trees, animals, and water, learning how to cover themselves, to cook, to shelter, to hunt, to forage and to grow food. It is a story of profound and intimate interrelationship with the living land, and of an embodied life within a local ecology. In the Maori tradition, the origin of the world occurred when the seventy children of the ancestral mother and father decided to separate their parents from their loving embrace.

This tight embrace had generated darkness, while the children wanted to be in the light. So, Tane Mahuta, the god of the Forest, forced them apart and made space for light to manifest. Father became the Sky Father and the mother became the Earth Mother. Telling these stories and celebrating this kinship is a way constantly to re-generate and re-connect with the world and our role within it.

In most stories and ceremonies, as much as in daily life, plants are celebrated and engaged with as relatives and friends, as plant-persons. In many Indigenous stories, plants are addressed as ancestors, as the elders of the family, whose young children are human beings, offspring of plants –such as corn in Maya culture.

In this way, we are not only reminded that we are part of the natural world, but that we are very similar to plants. Other stories tell us that plants are our friends and teachers, powerful non-human persons, with whom we should learn how to interrelate. If a plant is family or friend, how can we help? What is our role? In some cases, we should just leave a plant or forest alone. At other times, a plant needs to be tended and known. In this way, we can be known as an active part of the landscape, as stewards of the land.

1.

This vision is broadly shared by Indigenous cultures worldwide. In this light, the concept of owning land and of dominating Nature comes to appear very odd! In this way, we are not only reminded that we are part of the natural world, but that we are very similar to plants. Other stories tell us that plants are our friends and teachers, powerful non-human persons, with whom we should learn how to interrelate.

In most Indigenous cultures, the concept of individual land ownership does not exist. A whole community would own, or rather tend and care for, the land.

As we are all inter-connected and life is generated by nurturing a multitude of relationships with all the other inhabitants of the cosmos, humans have the duty to learn how to engage respectfully with the land and its non-human inhabitants. What should we humans do to keep a place, a land, alive? Tending plants in a community garden and learning their stories is one of the ways to reconnect with a place and make it thrive.

“According to the Anishinaabe Creation story, the trees and plants were created before the human beings, in the second wave of creation. In particular, two are the trees that reflect the microcosm of Anishinaabe culture: Grandmother Cedar and Grandfather Birch. My mother, Mary Geniusz, was often asked to give talks on Anishinaabe ethnobotany, and she would always start with my Grandmother Cedar. Nokomis is grandmother, a title given to women elders and to the white cedar. She always wanted to start with that tree. It is the tree that is at the centre of the universe for us.”

Wendy Makoons Geniusz - Anishinaabe scholar and ethnobotanist Maize Photo: Mumine Durmaz“In the Mayan culture, there are stories that go back to the beginning of time, where a special connection is established between humans and maize. There is an ancestral story where maize is used in the creation of the first human…. The first ancestors, the first deities gathered to decide what material should make the first humans. A first idea was clay. And the creation failed. They opted for wood. And it failed again. It was only when they decided to use maize that humans were finally created. As capable of knowledge, ethical behaviour, and able to recognise their creator. So, we are the children of maize! And this relationship is constantly remembered and reproduces in different ceremonies, daily practices and political mobilizations.”

Genner Llanes-Ortiz - Mayan anthropologist

More than twenty students became the key BOTANY BAY gardeners in a small plot of land at Chiswick Secondary School. Deepening their hands into the soil, they started seeding a new life to a barren piece of land from scratch. The project was developed in different phases and activities, with a much higher number of students engaged, as a way to have more classes take part in BOTANY BAY. Planting seeds and tending the young plants were just two of the interconnected actions for keeping the sprouting garden alive and learning about the plants’ stories through Indigenous histories and perspectives.

Indigenous herbs and vegetables were planted in the spring, along with the seeds of flowers, that attract and welcome butterflies and other insects, for example marigolds. Tasty tomatoes were harvested at the beginning of the autumn term, and were used by the kitchen staff in preparing meals. The students expressed strong feeling of anticipation in waiting for the plants to grow, and of wonder in seeing the blossoms, flowers and vegetables take shape and body through the seasons. An all-embracing sense of being together with others while learning a lot about growing plants and food was revealed by the young gardeners. On this fertile soil, the school is developing a long-term project of seed gathering and replanting the edible school garden. Also, thanks to the proximity of Chiswick House, old trees have been replanted in the school grounds as another manifestation of BOTANY BAY.

Besides the actual tending of plants, different forms of art thrived in the garden: painting, singing, dancing.… Wooden butterflies and flowers were painted by the students, together with some benches.

The garden is a triumph of colours that, welcomes humans and non-humans alike. The wooden materials used for these creations were re-cycled: a second life for discarded pieces of woods. Other activities involved visiting museums and the visits of Indigenous musicians and other performers.

Year 8 pupil Esther really loved the trip to the Garden Museum, where she could learn about plant stories, bridging their Indigenous heritage with the history of horticulture and colonialism in greater depth. Music and puppet theatre are part of the performance aspect of the project: gateways to make the garden alive, as the Wiraqocha whispers with his multicoloured presence. The students were involved in creating dances and songs inspired by Indigenous ways of gardening and the stories of plants in Indigenous cultures. These performances are intended to celebrate our connection with plants and Nature, as we do not own the Earth, but we belong to the Earth.

Created by Quechua artist José Navarro, Wiraqocha is the artwork installed on the wall of the BOTANY BAY garden at the Chiswick Secondary School, in West London. An actor and puppeteer, José had never previously created a piece for public outdoor display, rather than performance, so creating a piece in a garden was a challenge in itself!

BAY I Heritage responds to Colonialism, Climate Change and Covid

The artwork is made of foam to withstand outdoor conditions, and is highly dynamic. Wiraqocha is the creator of the world in Quechua mythology. Present in Andean iconography since the beginning of the Inca civilisation, he is the Sun god of Andean spirituality, deeply bound to the agricultural society of Peru. The name is made up by the Quechua words “wira”, meaning “fat, full of life”, and “qocha”, meaning “lake, water”. It refers to the generative and life-bringing power of water, and to the power of the Sun in nurturing life. In his personality, sun and water are deeply intertwined, as the sources of life, together with the Earth. In other South and Meso-American regions, the Sun god is called Pachakama, where “pacha” refers to the universe, but also to soil and time.

José slightly changed the traditional iconography of Wiraqocha, adapting it to the plant world of BOTANY BAY. Along with animal and star motifs, this Wiraqocha is a floral and vegetal being holding tools of power, that create life. These also recall some of the tools used to tend the garden and work the land.

In a garden, the elements of water and sunlight are fundamental for new plant beings to be(come) alive! Life thrives with water and light, while being rooted in earth and nurtured by the soil. Wiraqocha’s female counterpart is Pachamama: Mother Earth. These two Andean deities remind us of the interdependence and dynamism between opposites, and that everything in interconnected in an ever-transforming cycle, a dance between elements, finding harmony in conciliating oppositions.

Living in a time when people are often disconnected from nature as much as from older traditions, the artist and his Wiraqocha call us to a more direct experience of nature: on the ground, sinking our hands into the soil. At the same time, the artwork reminds us of the practical difficulties of growing something dependent on climate and the elements. When you grow plants, you are fully dependent on soil, sun, water, wind, other plants and beings. We are reminded that growing and tending plants requires care and presence throughout the seasons, and that we humans are connected to the world, just like the plants.

AP

“Everything is life. Life is everything. We are the breath of our ancestors. We are part of this cosmos. We need to respect life as much as our ancestors and our descendants. Respect, support and let each other grow.”

Hivshu - Inuk hunter and storyteller

BOTANY BAY I Heritage responds to Colonialism, Climate Change and CovidOver many centuries, Indigenous people have established deep and intimate relationships with their lands, the local ecology. By listening to and observing the land and its non-human inhabitants, they have developed a rich and embodied knowledge of nature. All the senses are involved in this relationship of knowing and being with the land: its waters, soils, weathers, plants, animals. Such profound knowledge and relationship to land has enhanced Indigenous people’s capacity to observe and listen to the landscape and its changes. This happens in such a way that any change in the other beings inhabiting the land, including the water, the soil and the sun, is immediately perceived through an embodied form of non-verbal communication between humans and nature.

In pre-colonial times, daily and sophisticated processes of knowing and interacting with plants – including observation through plants’ life cycles, stories, ceremonies and dreams – enabled Indigenous communities to establish deep, embodied relationships with plants. People observed and worked with plants for food and medicine, creating a wealth of traditional knowledge and practice. However, these acute and sophisticated knowledges were slandered as primitive thinking or witchcraft by European settlers. By the end of the 20th century most Indigenous traditional knowledge had (almost) disappeared. In recent decades, the revitalisation of such knowledges has gathered momentum, as Indigenous people assert their rights and the importance of their cultures. This endeavour sees a synergetic collaboration and dialogue between Indigenous and non-Indigenous

science, art, agriculture and horticulture, and activism. This regenerative wave seeks to recover and inspire different, intuitive and embodied ways to engage with plants, where old and new knowledges and perspectives can reconcile. How can we observe plants and listen to their stories?

A group of 12 pupils met every Tuesday in the BOTANY BAY Gardening Club at the Hurst Drive School, Enfield. This weekly gathering was named by the young students “Magical Tuesday”. With the assistance of Nisha Dassyne, they planted and tended a great variety of plants in the soil of North London, with its dramatically changing climate. The Three Sisters –different varieties of pumpkin, squash, beans and corn – were planted along with sunflower seeds. They were abundantly watered and cared for over 2022’s scorching summer months by Nisha. At the beginning of the autumn term, one type of corn survived, while most pumpkins were good but small due to drought. Most squashes had been successful, while the Lima bean managed to swing upward on one corn stalk. Cherokee smokey purple tomatoes ripened while kids were on holidays and got eaten by squirrels, birds and foxes. Purple potatoes were harvested in July. The joy and surprise in the children’s faces while peeling the potatoes was overwhelming: all that ‘purpleness’ generated quite a reaction!

“If a plant shows up a lot in your life, you must pay attention! That plant has a knowledge to share with you.”LeAndra Nephin - Omaha

While trying to grow originally Indigenous plants in different soils and climates, the children learnt the stories of those plants in dialogue with people of Indigenous heritage, and through visits to museums and gardens. Every two weeks they filled their journals with their impressions about the experience. What emerged was a genuine curiosity about growing plants as in their original lands by Indigenous people, as much as an intense desire to connect with those places and traditions. While putting their hands into the soil, a student exclaimed “We are digging to Australia!”.

The stories of plants captured their curiosity and inspired individual ways of storytelling and relating to specific plants. One student, Annabel, enjoys telling the Three Sisters story in her own way, stressing the fact that each plant has its specific and unique personality, but that only by cooperating and supporting one another can they truly thrive.

Others express their joy at being in the garden because they don’t have any outdoor space at home, and manifest their wish to grow more things and bring flowers and vegetables to their families. They all seem concerned about the wellbeing of plants, and love watering them: “The plants look thirsty: can we water them?” is one recurrent question heard in the garden.

All the pupils are very keen on hearing stories of personal relationships with plants from Indigenous people from around the world. In July, a ritual for Pachamama was performed by Rafael Montero with the children. A Lilly Pilly (acmena syzygium) was planted and all the participants offered a pebble with their wishes and thanks to Mother Earth. The pupils danced around the bush while humming together with Rafael’s chanting. Now a Eucalyptus Bough is planted in the garden: a branch that reminds us to listen to the living land.

“Together with corn, beans and squash, there is a fourth sister: the sunflower.These Four Sisters do more than providing a harvest to the community - they actually thrive together. Each of those serves an important individualised role. Sunflower protects the corn, beans and squash from the Nebraska winds and diverts birds from the corn. And the corn acts as taking nitrogen out of the ground, while beans return the nitrogen back to the soil. Squash is used to fend off racoons and other animals. There’s an intelligence there, in the way these plants are planted together in a spiral.”

LeAndra Nephin, Omaha Tribe

LeAndra Nephin, Omaha Tribe

Wiradjuri-British artist Jasmine Coe created a colourful bough with a eucalyptus branch and honey bees. Native to the Australian continent, ‘eucalyptus’ is a name that encompasses more than 900 species of the genera Eucalyptus, Corymbia and Angophora. Eucalypts evolved from rainforest ancestors, adapting to dry and nutrient-poor soils where fires were increasingly common. Sacred to Indigenous Australian peoples, eucalyptus has been a constant and familiar presence in traditional ceremonies for thousands of years.

Trees are connectors of the world, a world we too often forget to look at, listen to and look after. On the eucalyptus branch Jasmine painted honey bees flying upwards, as a reminder of the importance of balance in the natural world. With their voices and sweet presence in our gardens and pastures, bees can bring us back to listening carefully and deeply to the stories of the other-than-human beings that live all around us. This branch comes from a eucalyptus tree grown in the UK, as a way to build bridges and connections between lands and plant species. The eucalyptus tree was felled before Jasmine started looking for a locally grown specimen.

Some curious synchronicity took place: she was already looking for a eucalyptus tree and, shortly after she found it, she was asked to create an artwork for the garden. “When things happen this way, they are meant to happen”, she says: “Things just unfold when we are attuned to Nature.” When we observe, pay attention and listen, to ourselves and the rest of the community of life.

Visiting Hurst Drive School, Jasmine was greatly impressed by the pupils in the gardening club. The young gardeners manifested a deep knowledge of plants and their Indigenous stories, as much as of the vital presence of honey bees in the garden and beyond. Her Honeybee Tree is now planted in the garden, its totemic guardian.

As bees dance and talk through sound, trees and plants communicate between themselves and with other beings –such as insects or fungi– and the living land. They have their own peculiar relationship with their local environment, developed through millennia of rooted existence. We need to learn their language, listen to their songs and understand that we are not the only persons on the planet. Trees are living beings and teachers from which we can learn how to resonate with the beat of the Earth, and whom we should all celebrate and nurture.

AP

“Being observant, be mindful. Foster the connection to the land. Which starts with gardening. That first time that you reach into the soil, you feel the moisture, and how that feeling enhances the growth of something. Test and experiment with ways of fostering plants. Grow them like babies. You are observing and partaking to life’s growth. Take time to be observant of the land, the water and the cosmos. Being aware of which plants are edible around you. Learn the science and technology for taking care of those things. Maybe even come up with your own ceremony to honour or create a reciprocal relationship with plants. You can use apps that identify plants or take a picture of the plant. Start thinking outside the conventional ways to engage with plants. And on how we can incorporate wild flowers and weeds, and on being aware and researching on the plants that grow around you! Talk to your grandparents and listen to their stories.”

“When I became a hunter, I was hunting in the fjords where the ice was think. So we had to be aware of the ice and of the underneath currents in the sea. When it was cold, it was safe to cross the ice. We still hunt the same way our ancestors used to.… In 1986 I noticed the changes were coming. The undercurrent of the sea has changed. What used to be a thick ice was thinner with no snow. Then in 1992, when I was visiting the family, the sound of the ice revealed that it was changing as well. We cannot cross the fjord any more now.… Those changes have deeply impacted my people and the ways they are hunting. They are trying to adapt to new ways of hunting, fishing and living.… We are out in nature. We even notice that the sun has changed: it is sticky.”

Hivshu - Inuk hunter and storyteller

Hivshu - Inuk hunter and storyteller

We are living in times when a resurgence of food sovereignty and revitalisation of traditional agricultural methods is spreading across Indigenous communities and organisations. Part of this movement calls into question the way we engage with plants in modern, mainstream thinking and behaviour. How can we truly work together with plants? How do we approach and grow them with the respect they deserve?

For too long, the stereotype of an Indigenous person has been that of a savage, a hunter and warrior, who would roam restlessly from place to place. In contrast to this shallow colonial image, Indigenous people worldwide have long possessed a profound and embodied knowledge of their land, attuned to animal and vegetal life cycles. Traditionally, plants were both foraged in the forests, deserts and pastures, and grown in family or community gardens. Tending a forest and an orchard were parts of the same system, belonging to the same field of relationships with nature, and not in opposition to it.

Certain cultures developed highly sophisticated methods for growing vegetables.

For instance, Maori were excellent gardeners in pre-colonial Aotearoa/New Zealand. They practised a mutually beneficial way of cultivating plants that would enhance the health of the soil, plants, fungi, animals and humans.

Across the Americas, a model of growing has developed throughout the centuries, called the Three (or Four, or Seven) Sisters Garden. The many variants of the Three Sisters story tell us that corn, bean and squash, when grown together, are not only able to provide the human community with all that it needs, but they also thrive together. Along with the Three Sisters and their rich varieties of ancient seeds, other plants –such as sunflowers and other flowers, tomatoes, and medicinal plants–were and are grown in a truly synergic polyculture. This Indigenous system is based on a profound knowledge of how plants collaborate among each other and with the land. It stresses how an approach to cultivation based on inter-species cooperation and reciprocity, with humans included, can inspire alternative ways of living, being and eating in accordance with the cyclical rhythms of nature.

“The Maori were not warriors. Once were gardeners, once were poets, once were singers. Perhaps even they were lovers.”

Moana Jackson - Maori elder“When you approach a relationship with a plant with the understanding that a plant is your relative and you are sharing the breath with each being, you will be more inclined to treat them in a respectful and sustainable way. For example, this morning I went to pick some strawberries I am growing in my garden. Every time I pick some, I touch one of the leaves of the plant and thank the plant for its gift. I thank the earth where the plant is growing for the gifts that it gives us. I do this all the time also when I am outside in the woods here. When I meet one of my favourite plants, I touch them and thank them for their energy, for their gifts. But also I touch the plant as a way to share energy with them. As a way to connect with plants and establish a communication.”

Salmon, Raramuri ethnobotanist“In our garden today, we grow kumara, sweet potato, in the traditional Maori way. In the past there were 40 or 50 varieties of kumaras, as Maori dwelled in Aotearoa/New Zealand for about a thousand years. To a certain extent, we garden in that way. Most of the plants we grow, we grow in a soil where we observe permaculture. We do not use any artificial fertilizers or any chemical sprays. That might sound unusual in today’s agriculture, but if we go back a hundred years or so, we have never used any of those things. I shudder for what is happening to the Earth as a result of using those chemicals. Going back to the principle that the Earth is our Mother, it was very important to us to revere our mother. We would never poison that soil. We would certainly treat it with the highest respect. And above all what we wanted to do is to create that energy in the soil, that spirit that we call mauri.”

Small, Maori gardener and ethnobotanist Rob

Rob Small, Maori gardener and ethnobotanist

Rob

Rob Small, Maori gardener and ethnobotanist

BOTANY BAY pupils at the Oswald Road School enjoyed the presence of and activities with Maori artist Frederick Worrell. Being involved in the actual making of his mirror paintings, children felt part of the creative process, having fun with glass colouring as much as with choosing and imagining the birds to draw. While learning about Indigenous plants and their histories, the young students appeared more interested in “indigenous” British crops and animals rather than species from former colonial spaces. This desire for a local Indigeneity is reflected in the Maori mirrors, where, along tropical and exotic imagined birds, the local robins are depicted!

The artwork here expresses the immense potential of reconnecting to the local landscape while creating bridges with other cultures. Art becomes a privileged place for the co-creation of new stories that tell of different, respectful relationships between generations, cultures, worldviews and plants. In this way, children are inspired not only to learn about Indigenous plants and the history of colonisation, but also to discover and connect with their surrounding landscape and its non-human inhabitants. To learn, as Potawatomi botanist Robin Wall Kimmerer writes in “Braiding Sweetgrass’, how to become indigenous to a place and “enter into the deep reciprocity that renews the world”.

The garden is the physical space for learning how to connect art and plants, and how to work together with nature. One of the outcomes of such (re)connection and collaboration is the poem “Growing Our Garden Again”, written during the visits of storyteller Gordon McLellan:

Nolocustswarm,noelephantherd, noflockofhungrygeese Could match the feet of our school, No blindfolded mole could see less Thanthepeoplewhodidn’tnotice, Thebedswehaddug, Theseedsastheygrew, Theplantswehadplanted, Thehopethatflowered Andwastrampledintotheearth. Butthepotatoesgrew, Rootsdiggingdeepandleavesliftinghigh, With small blue flowers tucked into potatoshadows, Ourpotatoesareheroes! Championchip-makers! Crisp-growers,mash-givers! Weareproudofourpotatoes. Wewilltryagain. Wewilltryagain! Wewillgrowatasteofnature And remember the chilis and sweetcorn andsquashthathavegone. But next time there will be strawberries, And fruit trees, Appletreesmaybe, Andtherewillbeafencetoguard ourplants, Andnewplants, And a nature area, For us and for animals. Wewantagarden,where Birds can come to feeders, Where butterflies visit Wherebumblebeesarehappy, Whereinsectsknowtheyarewelcome. There will be art here, And flowers, And excitement, Andhope, Andaquietcorner.

“We started gardening as an act of resistance and food sovereignty”LeAndra Nephin - Omaha

And all our hard work We’reproudthatwecandealwithour problems. Wewanttostarteatingthefoodthatwe grow, Andwewanttogrowtohelpeachother, Tohelpourschool,tohelptheanimalsthat visit us.

We tried once, and Wewilltryagain. Wewillsticktogether. Wewon’tgiveup. Wewillpersevere.

“A long time ago, before contact, and then into the early 20th century, gardening was a very big part of Anishinaabe life. Everyone in the Great Lakes region has an orchard. There are stereotypes of Indigenous people roaming around looking for food. But this is a stereotype. We had large farms and plots of land where to grow food in South and North America. Today there is a resurgence of gardening, which is part of the food sovereignty movement….. Started few decades ago, the concept of food sovereignty is that to be truly a sovereign nation, independent from the governments, we need to have our own food resources.”

Wendy Makoons Geniusz - Anishinaabe scholar and ethnobotanist Frederick Worrel, Rere Pai

Frederick Worrel, Rere Pai

A deeply generative and collaborative artwork is displayed at Oswald Road School in Manchester. The three paintings on mirrors were made by the Maori artist Frederick Worrell, who engaged in a process of co-creation with the pupils. Because of his previous work about birds native to New Zealand, he wondered how to include plants, while learning about plant migration and the history of gardening thanks to BOTANY BAY. On his first visit to the gardening club, he asked the children which were the native birds of Manchester and how they interact with them and the trees in the garden. So he ended up with the idea of three different but connected paintings on mirrors that seek to bridge British birds and plants with New Zealand ones, and Maori art. The central piece is a traditional Maori self-portrait, representing the Garden Guardian sided by branches inhabited by local birds. The left one, Art Birds, depicts native British birds moving into a vegetal canopy, while the right one, Fly True, portrays tropical invented birds in very bright colours. This tropical scene aims at stressing the climate transition we are living in and the warming up of the Earth.

At the same time, Frederick wanted to offer his art to empower the children. He gave his drawings to the children to paint with a limited palette. The pupils had the opportunity to engage with a precise colour scheme. But also it was entirely up to them how to respond to the black lines and white voids. At the end, “What they gave me back, I made!”

The second step was the painting on mirrors –a unique process he is implementing. When exposed to natural light, the painted mirrors shimmer only at a specific time and place. And it is in that brief moment that you can experience the magic, and fully perceive the spirit and agency of the artworks. According to Freddy, it is actually that impermanence that bring us back to time and place, to live the moment fully. And that’s magic. Also, as the painting reflects the viewer, you become part of the artwork itself.

For the artist, the whole process taught him a lot about collaboration, and enhanced his personal efforts to create a dialogue between British and Indigenous cultures. Freddy himself has mixed ancestry: British and Maori. He grew up in Whakatane on a dairy farm, away from Maori culture, but he still recalls the systemic racism around him when growing up. Only after moving to the UK has Frederick become engaged with the revival of Maori language, art and culture. According to him, “Indigenous art has been becoming popular, because of expressing different worldviews but also because they are oppressed cultures.” As part of the differences in worldviews, we are reminded that in traditional Maori art, the ancestors’ portraits include mountains, rivers, waters, trees –the living beings that live on and with the land and whom we are all called to protect.

AP

“Specifically on gardening, the Maori were extremely observant. As they have been in their original islands in the civilization in the Pacific they developed an understanding of their environment by two things. One is that they had to have a creation story explaining how the world came to be. And then they had to understand and observe their environment very astutely. I would say that the Maori developed a science. A sophisticated knowledge of the stars, soils and plants.”

Rob Small, Maori gardenerIndigenous cultures have been moving forward while looking backward for centuries: the present and the future dialogue with the past in a dynamic interplay. It is crucial constantly to look ahead for seven generations when thinking and acting in the world. At the same time, we must remember the teachings of our ancestors, another seven generations on our shoulders. But what does “looking forward seven generations” mean in practice?

It means respecting other living beings and, when we talk about plants, practising the Honourable Harvest. When we are about to gather a plant or part of a plant, we should make an offering and show our gratitude, taking only what we need for ourselves and our community. In this way we promise that we will make sure that plant being will continue living in the future.

One way to fulfil this promise is by perpetuating the cycle of seeds. The vital cycle of seeds is granted by gathering, planting, collecting and sharing heritage seeds. There is a global movement around heritage seeds, which is connected to food sovereignty and environmental justice. Indigenous ecological and agricultural knowledges are (finally) becoming recognised as key for the survival of biodiversity, thanks to their multiple strategies of adaptation in different climatic contexts. Our role as humans is to preserve biodiversity, including in agriculture. Walking along this path means to be(come) stewards of the land, to protect and perpetuate local species and their variants.

In walking this path, Indigenous and non-Indigenous/Western sciences and knowledges should collaborate. We might share a complex and painful past of conflict and colonialism, but we do also share the same challenging present and future.

As Genner Llanes-Ortiz reminds us: “If we are all made of maize, and maize comes in different colours, then we are all equal as humans no matter the colour of our skin”. It is time for reconciliation between the others and ourselves, for working together on a common sustainable vision for the present and future. And that is why we need to nurture an inclusive polyculture of knowledges and stories. It is time to “become Indigenous”, rooted in our places. To be the seeds of change.

“Heritage seeds are different versions of plants that our ancestors created to grow in different climatic and soil contexts. All that exists. It is just a matter of trying to propagate them again. There is a process of seed gathering around the world. If you start gardening maybe you start with planting heritage seeds! And then you grow the cool little being, and then you learn how to save seeds and plant them again. Every time you plant, you save the seeds. And you share them with people! The fear is that we are going to have one kind of corn, and one kind of potato. When something happens to one kind –and something will happen because there are too many beings of the same kind in one place they eventually get sick– then we won’t have that being anymore. This isn’t just Indigenous people talking about this: it is quite represented by scientists, environmentalists around the world.”

Wendy Makoons Geniusz - Anishinaabe scholar and ethnobotanistAt Cavendish Primary School children of different ages gather each Thursday during the lunch break. They enjoy watering the plants, sitting watching different plants growing, chatting and listening to the plants’ stories. Dwarf sunflowers, strawberries, turnips, tomatoes, squashes and potatoes have particularly captured their attention. Teachers report that these students recognise BOTANY BAY as a place for leaning the many ways of using plants.

In the school garden, a bed for each year group has been established as a way to have the whole school involved. Despite the challenges of access to water and the scorching summer heat, most plants have survived and ripened. A colourful harvest of tomatoes, squashes and potatoes was picked in early October. The harvest was brought to the school kitchen, where potatoes were used to make salad. Such an experience of being present through the whole process –watching plants grow and transform, from seed to food– mesmerised the children. The firsthand experience and sustained empirical learning has made a deep impact on children and their personal growth, their social and environmental interactions.

The children have also engaged with the garden and the plants through the arts. Visits by Gordon McLellan captivated the pupils, as much as the puppet performance by Quechua artist José Navarro enthralled them. Another Peruvian artist, Bella Lane, stepped in the gardening club in July. She brought cucumbers, watermelons, melons, tomatoes in pots for being replanted. On that occasion, pupils drew some of the plants in their journals. During a storytelling session, Bella told the students sitting around her that “Plants are like children. They are my babies. I talk to plants. I take care of them, especially when they are small. And the Amazon is my garden.”

The school has started planning other areas for gardening, as a long-term project that will further develop from the BOTANY BAY initiative. Around a pergola, they planted new seeds and ongoing conversations are taking place on how to garden other areas according to the Indigenous principles. The educational importance of continuing this project is manifold: it is a great opportunity for children to develop responsibility towards places and other living beings, to nurture a different consciousness about nature, and to foster ecological living. Ideally, children that have been involved with BOTANY BAY will take the lead and teach others, not on the basis of age but of embodied knowledge. Indeed, this gardening club has involved different pupils aged from 6 to 10, with classes working together, sharing knowledge and stories, and having fun. Such a growing path is well reflected by the sculpture of the Tree of Life, the connector of worlds that holds past and present together.

A Tree of Life is displayed at Cavendish Primary School, London. This Tree of Life, or rather, Willow of Life, was created by Huitzomitl, an Otomi and Chichimec tattooist from Mexico, living in London.

The two and half metre tall tree sculpture is made of intertwined fresh black willow branches. On its branches tiles painted by the pupils are hung: these depict symbols connected to the plant world and the Indigenous worldviews that students have studied. The willow was braided together directly in the school garden, in the presence of the observing and curious children.

The willow branches refer to the temazcal ceremonies, where the willow comes back to life. A temazcal ceremony is a traditional Indigenous sweat lodge ceremony dating back to pre-Columbian times and still practised in Mexico and other Mesoamerican countries. Such a ceremony is traditionally performed for cleansing, regenerating and reconnecting to oneself and the broader network of life. During the procession, branches of local trees are carried by the participants: the branches stand for the embodiment of Mother Earth: they are her bones and veins. In fact, the same structure of the sweat lodge can be built by weaving the tree’s branches.

As the tree is the being that connects us to the roots of the Earth, the interwoven branches embody the interconnection and interdependence among human and non-human beings, space, time, land and other dimensions of life. According to Huitzomitl, the tree is the connector between worlds, realities and times. This idea of the tree of life or world tree is found in many cultures. With different nuances and species according to the local environment, trees have been understood and engaged with as connectors, sacred and healing beings. As willows do not grow in Huitzomitl’s ancestral land, the arid Mexican desert, but are a familiar presence in Britain, black willow was chosen by the artist. In this way, the willow becomes a reconciliatory bridge between Indigenous ceremonies and cosmovisions, and the native plant world of England. It brings us to the importance of rediscovering and recovering traditional European plant knowledges. In ancient British mythology, spirituality and traditional healing practices, willow had a significant role. Growing in water, the willow is a flexible tree utilised for weaving baskets and for treating wounds and fever. Curiously, Huitzomitl prepares and uses a black willow’s bark cream for preventing skin infections in his job as tattooist.

The Tree of Life, that holds the world together, stands in the garden to teach us with its gentle and constant presence. It reminds us that everything is connected, including the past, present and future, and that we should all walk forward by looking backward. If we want to look forward seven generations, we should learn the lessons of reciprocity and thanksgiving. The Willow of Life will then be able to renew itself time and time again.

“In former times, when you were about to gather any living being, including plants and stones, people used to make a prayer, because each being has its own guardian that takes care of him. Moss, grass, valley, river, water: they all have guardians so you need to ask for permission. And you shouldn’t use more than what you need.”

“Biodiversity has protected different people and communities over the centuries, both allowing them levels of autonomy and self-determination on what they grow and eat and how they eat, access to supply of food. Nowadays this is even more crucial when we are facing drought, climate change, floodings, wild fires all over the world. Then Indigenous agricultural practices have started being identified as key for the survival of the species. All this biodiversity means that we have a wide range of solutions for different climatic conditions.”

“You make an offering and you promise that being that you are only going to take as much as you need and that that being will still exist in the future…. Because you have to know how that plant is going to propagate, and how you can fulfil that promise. Once you know that, you can make sure you don’t kill it in that spot. And if you need to take too much, you have to make sure how to grow the plant back.”

Makoons Geniusz - Anishinaabe scholar and ethnobotanist“With the word ‘Indigenuity’ we refer to those solutions to the current situation, like climate change, that are informed by Indigenous knowledge to create future solutions. We avoid thinking of them as historic, but actually as knowledges and practices that were working with care and in gratitude with the land.”

Wendy

Alexandra P. Alberda - Pueblo Curator of Indigenous Perspectives, Manchester Museum

Wendy

Alexandra P. Alberda - Pueblo Curator of Indigenous Perspectives, Manchester Museum

Culture and language are deeply intertwined with the ways in which we relate to and explain our environments. After centuries of silencing Indigenous cultures and their rich languages, we are now seeing intense efforts for revitalisation. These efforts are intended as acts of respect and reconciliation with culture and the land; pathways to re-learn and put into practice traditional relationships with plants and the other beings inhabiting the planet.

In this healing path, the role of stories, songs and ceremonies is vital. Stories are “the fabric of our humanity” (Enrique Salmon) and give voice to non-humans. Being stories turned into sound, songs touch fleshy cords and are able to heal through the vibration that spreads in the land and within our bodies. Ceremonies, be they sacred events or intentional approaches in daily gestures, attempt to restore our relationships with the living Earth and to bring us back into connection. Storytelling, singing songs and performing ceremonies (re)generate reciprocity and respect with the land: they are a powerful human way to present gratitude to plants, trees and other beings.

Also, stories and performances are powerful ways to transmit and share knowledge, and can inspire changes in the ways we think and act within the world.

The ways we grow, harvest, prepare and share food are crucial in showing gratitude and performing respect to those we eat, to the wide community that sustains us. The performative nature of preparing and sharing food is manifested in its repetitions and daily gestures, and generates proximity and warmth between humans and non-humans.

In this light, art meets gardening, horticulture and the stories of plants. When art allies with learning about plants and their tending, an embodied plant activism takes place. Gardening becomes an art, while the arts nurture the gardens. The garden grows into an open place bridging and putting into dialogue stories of migration and colonialism with Indigenous knowledges and voices, the local with the global, children with elders, humans with plants. New soil is generated for inspiring ways to engage with plants in urban contexts, moving towards an ecological education with plants, their stories and Indigenous teachings.

“There are many efforts in culture and language revitalisation upon the horrible history of actual and cultural genocide. What I’ve been part of in my own life has been trying to learn and re-learn the names of plants and trees that are central to our culture and important for making medicine. I started doing that because, as a child, I was taught that when you want to gather or harvest any plant and tree, any botanical material, we have to talk to that being and explain what we intend to do, introduce ourselves. Just the same way we would do to another human being. Because to us plants are considered our older brothers and sisters, and sometimes grandfathers and grandmothers, depending on the plant and tree. In that, I was told that talking to that being in our Ojibwe language is really important. Those beings want to hear our language, the same way we like to listen to our language. Addressing those beings in the language and knowing their names became crucial for establishing a close relationship with them. So I started learning them.”

Wendy Makoons Geniusz - Anishinaabe scholar and ethnobotanistAt Medlock School “a crack team of waterers” meets once a week with Zoe, the coordinating teacher. Working closely with her 5th grade class, she stresses how much the children benefit from a close working relationship with her in the garden and within the classroom. Outdoor learning and gardening, as much as the role of stories, greatly benefit their education about plants and their engagement with the surrounding natural world. Especially after the Covid-19 pandemic, when they were kept indoors and reduced to online learning, the children were not used to walking in long grass, to insects, to getting dirty with the soil, to the weathers and the seasons.