THE PROMISED LAND

Intercultural Learning with Refugees and Migrants

This publication is distributed free of charge and follows the Creative Commons agreement Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives (CC BY-NC-ND). You are free to reuse and share this publication or parts of it as long as you mention the original source. Performance rights for DON’T LET THEM TELL YOU STORIES are reserved.

This publication should be mentioned as follows:

E. Efeoglu, M.Walling (eds), THE PROMISED LAND - INTERCULTURAL LEARNING WITH REFUGEES AND MIGRANTS.

Link: https://www.bordercrossings.org.uk/programme/promised-land For further information please contact info@bordercrossings.org.uk

The publishers have made every effort to secure permission to reproduce pictures protected by copyright. Any omission brought to their attention will be solved in future editions of this publications.

Published by Border Crossings 2019

ISBN 10 - 1-904718-11-6

ISBN 13 - 978-1-904718-11-6

EAN - 9781904718116

Cover image: Esodi (Exoduses) group, “L’Eredità di Babele” (The Legacy of Babel, Teatro dell’Argine)

(Photo

2

© Lucio Summa)

THE PROMISED LAND

Intercultural learning with Refugees and Migrants

Coordinating Organisation - BORDER CROSSINGS (UK) www.bordercrossings.org.uk

Partner Organisations - ADANA ALPARSLAN TÜRKEŞ BİLİM VE TEKNOLOJİ

ÜNİVERSİTESİ (Turkey) - www.atu.edu.tr

- i2u-Consulting (France)

- STADT OLDENBURG (Germany) - www.oldenburg.de

- TEATRO DELL’ARGINE (Italy) - www.teatrodellargine.org

Associate Partners: France: AFPA, Association AKWAMU, Médecins sans Frontières. Germany: Stadt Oldenburg, Ausländerbüro, Jugendkulturarbeit e.V., Landesmuseum für Kunst und Kulturgeschichte Oldenburg, IBIS e.V., Migrationszentrum Oldenburg, inlingua Sprachschule Oldenburg, pro:connect e.V.. Italy: GVC ONLUS, Comune di San Lazzaro di Savena, Cooperativa Camelot, Opera Padre Marella, Istituto Aldrovandi-Rubbiani, ITC Teatro di San Lazzaro, CPIA Centro per l’Istruzione degli Adulti, Cantieri Meticci / MET, MAMbo Museo d’Arte Moderna Bologna, Biblioteca Salaborsa, Centro Interculturale M. Zonarelli. Turkey: Association for Solidarity with Asylum Seekers and Migrants, Support to Life Association, Turkish Language Teaching Centre - Adana Alparslan Türkeş Science and Technology University UK: Borderlines, CARAS, Cavendish Primary School, Chickenshed Theatre, Clowns Without Borders, Migration Museum, Red Cross, Refugee Therapy Centre, Rich Mix Arts Centre, St Charles 6th Form College, Westway Trust.

E-book edited by Assoc. Prof. I. Efe Efeoglu Prof. Michael Walling

© All copyright remains with the authors.

This project is funded by the Erasmus+ Program of the European Union. However, European Commission and UK National Agency cannot be held responsible for any use which may be made of the information contained therein.

The European Commission support for the production of this publication does not constitute an endorsement of the contents which reflects the views only of the authors, and the Commission cannot be held responsible for any use which may be made of the information contained therein.

3

4

CONTENTS Foreword by Bushra Ali 9 Introduction The Promised Land and the Parliament of Dreams by Michael Walling 11 Chapter 1 – The Contexts 19 1.1 Together for a Common Future: Refugees and Migrants in Turkey by Ilke Şanlıer Yüksel 21 1.2 The Asylum System in the UK, and the Work of CARAS by Eleanor Brown 23 1.3 Overview of Refugees’ Presence in Italy by Angelo Pittaluga (UNHCR) 26 1.4 Asylum in Germany from the German 27 Federal Office for Migration and Refugees 1.5 The French Migration Context in 2019 by Corinne Torre (MSF) 34 1.6 The Situation of Opera Padre Marella by Chiara De Carlo 39 Chapter 2 - The Disciplines 41 2.1 Theatre, Migration and ‘Crisis’ by Marilena Zaroulia 42 2.2 From Commonplace Perceptions to a Place in Common the Parable of Theatre in the Migration Years by Nicola Bonazzi 54 2.3 Cultural Intelligence (CQ ) by Necmi Turgut 62 and its Importance in Refugee Studies & I. Efe Efeoglu 2.4 A Manifesto for Germany Museums in Post-Migrant Societies by Nicole Deufel 72 2.5 Business coaching in THE PROMISED LAND by Nicola Scicluna 77 Chapter 3 - The Tools 81 Editorial Introduction & Ethical Considerations 82 3.1. Intercultural competencies for work with refugees and migrants. Adana, Turkey 85 3.2 Cultural work in response to the refugee crisis. San Lazzaro & Bologna, Italy 90 3.3 Educational use of theatre with refugees and migrants. London, UK 97 3.4 Museums as meeting points for work with refugees and migrants. Oldenburg, Germany 110 3.5 Application of intercultural competencies and awareness of refugee and migrant issues 117 to business contexts. Toulouse, France Chapter 4 - The Responses 123 4.1 Interview with Kouamé - Toulouse 124 4.2 Interviews with Ndjebel Sylla and Sulayman Camara - Bologna 126 4.3 Poems by women at CARAS - London 128 4.4 Testimonials from the Stadtmuseum exhibition “Anerkennung” (Recognition) 130 by Saad and Emad - Oldenburg 4.5 Don’t Let Them Tell You Stories: extract from a play by Brian Woolland - London 131 Chapter 5 - Policy Recommendations 141 5.1 Underlying Structural Causes 142 5.2 The Immediate Situation 144 5.3 The Role of Culture 146 5.4 Monitoring and Evaluation 147 Afterword 149 Notes on Contributors 151 Photo Descriptions and Credits 153 5

<<On peut dire que la pensée postcoloniale est, à plusieurs égards, une pensée monde… Mais la critique postcoloniale est également une pensée du rêve: la rêve d’une nouvelle forme d’humanisme - un humanisme critique qui serait fondé avant tout sur le partage de ce qui nous différencie, en deçà des absolus. C’est le rêve d’une polis universelle parce que métisse.>>

(Achille Mbembe - Sortir de la grande nuit)

“It could be said that, in many respects, post-colonial thought is a conception of the world… But post-colonial thought is also a dream: the dream of a new form of humanism, a critical humanism founded above all on the divisions that, this side of the absolutes, differentiate us. It is the dream of a polis that is universal because ethnically diverse.”

(Achille Mbembe - Emerging from the Dark Night)

“Some natural tears they dropped, but wiped them soon; The world was all before them, where to choose Their place of rest, and Providence their guide: They, hand in hand, with wandering steps and slow, Through Eden took their solitary way.”

(John Milton - Paradise Lost)

6

FOREWORD AND INTRODUCTION

• Foreword by Bushra Ali

• Introduction: The Promised Land and the Parliament of Dreams

7

FOREWORD

by Bushra Ali

I still remember the war plane which flew over the horizon in my home town of Menbij in 1 July 2012, landing and throwing over the heads of the innocent, awakening everybody, marking the coming of the war. This war forced us to leave Menbij for the nearest safe place.

First my brother left Menbij for Europe (Norway), then my family - my father and mother and I - left for Turkey.

Turkey was our shelter and our refuge. It was very safe and its people were kindly: we felt we were not so far from our home. But as the months passed, life in Turkey was not so simple as we expected.

The first obstacle was Language. The smallest daily needs like how to buy our groceries, how to rent a house, how to continue our studies, how to find a job. My father had been a manager in many factories, but now he became an old man without the Turkish language. In Syria we had studied Arabic, English and French, but not Turkish.

In Syria I finished my first year in faculty of education in University, but now in Turkey I would have to start from scratch.

Some Turkish people seem to think the presence of Syrians in their country poses a threat to their jobs and study opportunities. This can make them quite aggressive towards us. To a degree they seem to forget why we came here in the first place.

Of course not all Turkish people are like that: many are really friendly, helpful and sympathetic.

Although the Turkish government requires schools and universities to integrate Syrian students, some teachers, professors and students don't accept it. They sometimes hurt the Syrian students' feelings with their glances which are enough to hurt their hearts. Even if we are refugees, we are still humans.

What we refugees need is for people to accept our temporary presence in their country, and to help us to overcome the difficulties that we face after we came here because of war.

I think the media can play a major role to reflect the Syrian misery and to explain to the Turkish people why we are here, and that we are ready to go back to Syria whenever the war ends.

I miss my town and its streets. I miss my house and my room. I pray to God to have peace in Syria so we can all go back to our home.

9

Menbij is a city in the northeast of Aleppo Governorate in northern Syria, 30 kilometers west of the Eu 1phrates. In the 2004 census by the Central Bureau of Statistics, Menbij had a population of nearly 100,000.

THE PROMISED LAND AND THE PARLIAMENT OF DREAMS

by Michael Walling (Artistic Director - Border Crossings)

There was a Biblical echo when we named the project. But we didn’t call it THE PROMISED LAND because we wanted to privilege the worldview of a Judaeo-Christian or Islamic mind. Rather, we wanted our project to be about Hope. The forlorn figure that begged to be released from Pandora’s Box, after all the evils had been unleashed upon the world, Hope is the human quality to which we turn when there is nothing else to sustain us. It is Hope that enables people to crowd into tiny boats and set out across the Mediterranean, with no idea of what may lie beyond, or whether they will even survive the voyage. It is Hope that compels them to cram into the backs of lorries, to scale barbed wire, to hang on the underside of trains. Hope appears when everything seems hopeless. It is the last reserve of the human spirit. Faced with another person’s Hope, it becomes our moral obligation to proffer THE PROMISED LAND.

THE PROMISED LAND had its origins in the EU’s Voices of Culture programme – a regular process of consultation with the cultural sector. In June 2016, a group of us gathered in Brussels to discuss the role of culture in response to the recent waves of migrations into Europe: the so-called “refugee crisis” of 2015. Micaela Casalboni, Nicole Deufel and I were all part of that group, and took an active role in preparing its report, which Rosanna Lewis of the British Council and I were subsequently asked to present to the OMC group, working on the same policy area. Our report and theirs converged in many ways, par 2 3ticularly around policy recommendations, but they also highlighted significant areas that required greater investigation and trans-national co-operation. Migration is clearly a European issue, and yet the response of most Member States has been inward- looking and self-serving in the most short-sighted way. Initiatives from Member States and at European level have tended to stress “integration” (or even “assimilation”), rather than the dynamic potential for cultural regeneration and revitalisation that new populations could and should represent. The onus has been laid on the migrants to adapt to host cultures, rather than on the opening of an equal dialogue; and this could be regarded as upholding and perpetuating neo-colonial relationships between cultures, rooted in histories of oppression and prejudice. At our meeting with the OMC group, the Dutch delegate Jan Jaap Knol highlighted their feeling that the real work of culture did not rest with the refugees and those working alongside them, but with recalcitrant host populations. For Micaela, Nicole and myself, the Voices of Culture consultation seemed to raise more questions than it solved. Our Strategic Partnership was set up in response. Micaela’s company, Teatro dell’Argine, parallels the work of Border Crossings in many respect s – not least in the way both organisations combine the intercultural outlook of their professional productions with direct grassroots work that places refugees and other cultural minorities in dialogue with host populations. Nicole’s work in the Civic Museums of Oldenburg is very different: here the cultural context is more established, so

https://www.bordercrossings.org.uk/sites/default/files/VoC_fullreportFINAL.pdf

https://publications.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/4943e7fc-316e-11e7-9412-01aa75ed71a1/ 3 language-en/format-PDF/source-30942640

INTRODUCTION

*

2

11

the process of institutional change required by the city’s rapidly shifting demographic is inevitably less nimble. For all the differences, the question of re-thinking our histories is at the heart of the project for all three organisations.

We realised that all three of us had quite similar standpoints, and that our voices came very specifically from the cultural sector. As we started to plan a funding bid for an Erasmus + Strategic Partnership, we began to consider the need for culture to resonate with and impact upon other sectors, the necessity of a networked approach not only to cultural, but to wider social and political initiatives. As a result, we approached Efe Efeoglu at Turkey’s Adana Science & Technology University, and Nicola Scicluna at i2u Consulting in France, both of whom could add new, broader perspectives to the work we were planning. Efe’s work is around Business Studies – and his institution sits in a city close to Turkey’s Syrian border, that has been transformed by the influx of new citizens since the civil war. Nicola, based in Toulouse, offers training approaches to teams in the workplace (for example at Airbus) as well as facilitating relevant policy conferences like the April 2019 Eurocities meeting. Our sense was that the addition of their organisations would give the Strategic Partnership a clear shape – starting from the educational and social initiatives which refugees and migrants may encounter on their first arrival in Europe, and proceeding through processes of cross-cultural encounter, dialogue and creativity towards a dynamic integration into a culturally open workspace. Such, at least, seemed to be our ideal model. This e-book charts the journey we have gone on together over the two years of the project, the learning that each partner has offered to the others, the approaches we have found to be most powerful and effective, and the policy recommendations we wish to offer in response.

The project developed through five “Training Weeks”, one hosted by each partner, starting in Turkey, and moving through Italy, the UK, Germany and finally France. In each country, we were able to explore the asylum system and its political context, the work of NGOs, educational and cultural institutions, and the processes through which migrants were able to enter the workforce (or not). We explored the processes and methodologies through which the different partners, operating in distinct but complementary sectors, were engaging in dialogues with new citizens – methodologies which are recorded and evaluated in this e-book. We attempted to frame the social, political and cultural changes we were witnessing within our established academic and vocational approaches – and constantly found them to be inadequate to the task. We found that the shifting populations of the new Europe demanded a total re-invention of our governing paradigms. It is perhaps this that is the real “crisis” with which we are faced.

This crisis of cultural adjustment was particularly manifest in two strands of our partnership’s work: pedagogy and cultural activism. Very early in the project, it became apparent that the accepted modalities of “training”, in which an existing knowledge, “owned” by a partner organisation or an expert individual, is imparted to others, was inadequate for the project’s needs. The cultural diversity within the participants themselves, and the cross-sectoral make-up of the partnership, meant that any methodology or theoretical framework required questioning, reflection and adaptation in order to be applied to the fluid and volatile current situation around migration. As a result, our training weeks, while continuing to offer examples of good practice and sharing our own approaches, increasingly became spaces of reflection and development, where the combined intelligence of participants was brought to bear on the cultural and educational practices placed before us. In preparing the week in London, I found myself deliberately

12

including one example of theatre around refugees that I actively disapproved of, with the clear intention of provoking debates around cultural and personal ownership of biographical materials. Nicole Deufel’s curation of the week in Oldenburg was similarly catalytic: she placed her own work in the context of a much wider global debate around the role of museums, and set it against a range of practices happening across the city in response to recent migrations. Those of us experiencing that week found ourselves having to imagine ways of bridging the apparent gaps between established museum practices and a rapidly shifting demographic. This was at once hugely challenging and highly empowering. Our developing reflective practice as a partnership has enabled new ideas to emerge for all the partner organisations, which would not have been possible without the dialogic processes the project has called out. We have been compelled to generate our own process of participatory and egalitarian pedagogy. This is paralleled by the most significant and inspiring practices we have encountered along the way – practices developed in our distinct sectors, but which I would group together under the label of cultural activism. Time and again through the two years of the project, we have caught glimpses of the dynamic and productive cultural exchanges that are possible when a “Third Space” is offered – a space in which hierarchies of power, 4 knowledge and culture are overturned in the pursuit of a genuinely participatory dialogue of equals. Teatro dell’Argine’s “Esodi” group is one clear example of this: a space where young people, migrants and non-migrants, work collaboratively to explore questions around identity, language and difference. The welcome we received from the Migrant Centre in Oldenburg, and from the refugee group IBIS, also demonstrated such processes in action: through dialogues, dances, planting flowers and eating together, these institutions enabled interactions on a basic human level that moved us beyond the labelling of otherness. In Turkey, Lucy Dunkerley and I were able to lead theatre workshops with groups of refugees at the NGO ASAM, and with students at the University –using drama as a way to open up the fiercely questioning intelligence of the young.

In the last example, the young people seemed genuinely shocked by the power of what they had created. Participatory theatre, based around the presence of the body in a shared space, had enabled them to see their society a little differently. The “other”, the “migrant”, the “refugee”, the potential “terrorist”, now became the neighbour in their midst. There was a clear and palpable human connection being made.

This seems to me to be the most powerful and significant finding of the project as a whole – the need for evolving third spaces in arts and culture, museums, education, the workplace and the polity: spaces where new citizens and established communities can and do meet on an egalitarian basis to work together on the challenge of jointly inhabiting a rapidly changing Europe. This is a huge challenge politically: but if we begin from education and culture, which is where all real progress begins, then we have a genuine opportunity for profound, necessary and lasting change. Not overnight, and not in the time of an electoral cycle: but in the longer term, as a vision of what Europe can and must become. We need to collaborate in articulating and building that vision jointly across our diverse communities, accepting and revelling in the complexities of cultural

This idea, first developed by Homi Bhaba, was introduced to the partnership by Simona Bodo in a talk she 4 gave to the partners in Bologna. It posits the need for a space for cultural exchange which is not owned by either the host or migrant community, but which allows for the possibility of real cultural shift and development, rather than the stultifying potential for entrenched positions of exclusivity and ghettoisation that could result from the perpetuation of first and second spaces.

13

diversity and the fierce, tender contradictions of democratic interaction. We need to eschew hierarchy and promote true equality, even at the cost of our own privilege. We need to meet the human in the other, to embrace them as our fellow travellers on the road to justice. A democratic culture of participation – a Parliament of Dreams.

It is deeply disturbing that, as we explored these real ways forward for our societies through participatory governance, much of Europe was heading in exactly the opposite direction. During our week in Germany, we spent an afternoon with an organisation running trans-European youth exchanges, and participated in some drama games with young people from Poland and Ukraine. Andrea Paolucci (from Teatro dell’Argine) was very disturbed when he played a word association game with them. The idea of “democracy” was associated with “corruption”, “self-interest” and “illusion”. The very idea of a participatory polity seemed alien to these young people. A few weeks later, Ukraine elected a comedian to be its next President.

At the same time, in Andrea’s home country of Italy, Matteo Salvini has been stoking the fires of racial hatred, strengthening his power base by “othering” migrants and ethnic minorities as convenient scapegoats on whom to blame the nation’s problems. Even in Germany, which in many ways is the most morally adjusted and politically astute of the countries we visited with regard to migration, there is a real threat from a resurgent right-wing populism, the Alternative für Deutschland. At IBIS, we heard about refugees having to be trained in strategies of resistance to right-wing extremism.

In my own country, the UK, the period of THE PROMISED LAND project was dominated by the farcical spectacle of Brexit. Aside from the absurd threat this posed to us even being able to complete the project , the political tensions in the UK threw into sharp relief the 5 very issues we were grappling with. The Voices of Culture process began in Brussels just ahead of the 2016 referendum, but already the warning signs were there. In their construction of an imperious European Union that would somehow foist millions of migrants onto a resistant, pure and superior English populace, the Brexiteers were deliberately and calculatedly employing the established strategies of the radical European right.

Nigel Farage’s poster, showing a column of refugees on the move and labelled ”Breaking Point”, was directly modelled on a similar depiction of Jewish people, which emanated from the propaganda ministry of Josef Goebbels . Farage unveiled the poster on the 6 very day that Jo Cox, a young MP who had done much to promote the acceptance of refugees in the UK, was murdered in the public street by a right-wing extremist. The fact that this rhetoric was able to prevail, and, three years later, continued to hold sway in spite of the appalling damage that Brexit would undoubtedly cause to both the UK and the EU, is a terrifying reminder of what happens when the public discourse is reduced to binary choices and to a process of “othering”. While the referendum may have had the appearance of a democratic exercise, it was nothing of the kind. True democracy depends on a deep engagement with the complexities of our place and time. That is why the participatory models we have found most beneficial to THE PROMISED LAND, both in

As an Erasmus + KA2 project with a UK co-ordinator, it appeared for a time in late 2018 and early 2019 that

THE PROMISED LAND could have ceased to be funded, had the UK left the EU with no deal.

See, for example, https://www.theguardian.com/politics/2016/jun/16/nigel-farage-defends-ukip-breaking- 6 point-poster-queue-of-migrants

*

5

15

pedagogy and in cultural activism, are models that require deep and prolonged engagement from the participants. Democratic choices need to be reached through a genuine process of exchange between people who have been thoroughly informed and who know that their opinion is valued – that is why education and culture are so essential in preparing the way. The referendum’s reduction of a hugely complex subject to a binary Yes or No was a complete negation of democracy, not its realisation. The same is true of the populist exploitation of new media (often, as in the referendum, conducted illegally): you cannot reduce the generation of complex policy to 140 characters with hashtags.

The ease with which a populace that is under-educated, disengaged, disempowered and culturally deprived can be manipulated has the potential to turn apparently democratic states into neo-fascist tyrannies. Our week in Oldenburg saw much discussion of what is termed “memory culture” – the German awareness of how the Weimar Republic gave way to Nazism, and the horrific results. It is that memory culture, that ability to learn from history and to engage the majority of the population in a culture of openness, that has made Germany the most welcoming European state for refugees and migrants, and the one with the strongest policies to facilitate integration. Crime in Germany has actually dropped to a 30-year low, in spite of the AfD’s warnings of disorder in the face of Angela Merkel’s 2015 admission of the migrants. This presents a stark contrast with the reductive appeals to “the people” being made by political figures in other parts of the continent. Theresa May’s outrageous speech of March 20th 2019, in which she told “the people” that she was on their side against elected Members of Parliament, was matched only by the incendiary rhetoric of the Daily Mail, when on 4th November 2016 it pro 7claimed the judges who had asserted the rule of law and the right of a sovereign Parliament to ratify any treaty between the government and the EU “Enemies of the People” –a phrase first heard during the Reign of Terror in the French Revolution. May’s outrageous attempt at populism – galvanised by the deeply undemocratic instrument of the referendum – was akin to populist appeals made by many other political figures who seek to legitimise their actions in relation to an apparently wide constituency, so circumventing the due processes of democratic debate and the rule of law. It is no coincidence that such figures tend to silence artists, academics and journalists through censorship or persecution: Salvini, Orbán and Erdoğan have all been guilty of this.

If the EU wishes to avoid seeing Member States and partner countries spiralling into a populist chaos, echoing the horrors of the 1930s with the migrant populations as the principle victims, then it must make every effort to generate a wide-reaching culture of engaged and educated participatory governance, fuelled by a thriving and active cultural sector. As a first step, it has to become far more transparent in its own operations, being seen to encourage the positive interactions that it clearly values (as exemplified by the Voices of Culture consultation, and indeed the present project). The EU-Turkey deal, which is discussed in these pages and particularly in our Policy Recommendations, was not a deal done by the EU at all. It was made by Mark Rutte (because the Netherlands held the Presidency) and Angela Merkel (because nothing happens without the most powerful Member State), in a closed room with Turkish Prime Minister Ahmet Davutoğlu. Even the President of the European Council, Donald Tusk, was not permitted to take part. Such an approach compounds the very image of a distant and uncaring elite, running

https://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-3903436/Enemies-people-Fury-touch-judges-defied-17-4m-Brexit- 7 voters-trigger-constitutional-crisis.html

16

policy for their own ends, that fuels a dangerous populism. The EU has to be bold enough to follow the values on which it was established, and to shift its workings from a perceived leaders’ club towards a Europe of engaged, politically participating citizens. This is partly a matter of empowering the European Parliament, at the expense of the Council. It is also a matter of rolling out a stronger, more embedded Culture and Education Policy to encourage mass participation in cultural and political processes and governance across the continent. As Jean Monet famously said, if he was creating the EU again, he would not start with the economy, but with culture.

In March 2019, the European Commission proclaimed the “Refugee Crisis” to be over. It was, at the best, a convenient untruth; at the worst a manipulative lie. The refugee crisis is anything but over: it has barely begun. There are currently close to 4 million Syrian 8 refugees in Turkey, where their status is uncertain and their lives are both unstable and unsustainable. The EU may believe that the deal in the darkened room that led to the closing of the border between Turkey and Europe was somehow a solution to the problem – but it did not give the refugees the home they need and it did not give Turkey the means to provide this. It was not only funding that Rutte and Merkel offered to Davutoğlu in that closed meeting: there were undertakings around visa-free travel for Turkish citizens in Europe, and accession talks as well. Seven weeks later, Davutoğlu was no longer Prime Minister, President Erdoğan had announced new powers for himself in the wake of the apparent attempted coup, and such aspects of the deal were called off. But if the EU could unilaterally renege on the deal, so can Turkey. There is no reason to suppose that Turkey will act indefinitely as a holding space for migrants and refugees.

If the EU-Turkey deal presents ethical and practical concerns, then the arrangements made by Brussels and Rome with Libya’s precarious and volatile Government of National Accord are even worse. These approaches to containment are merely expedient, and lack any political vision or moral probity. They are at best short-term solutions, which in fact perpetuate the crisis mentality, as it is in the interest of the Libyan militias to keep the situation unstable, so as to ensure themselves continued funding from Europe.

Europe cannot be so naïve as to imagine it can, or even should, simply stop migration. While the Middle East remains unstable, there will be wars and refugees will have to flee them. While the economic and developmental inequalities in the world remain so extreme (a situation for which European countries are largely responsible), there will be Africans who are desperate to cross the Mediterranean so that they can provide for their families and themselves. When climate change really kicks in – and that will be very soon – then huge swathes of the global south will become uninhabitable. We will see entire populations on the move. Europe has to prepare for migration that is not perceived as a one-off, containable “crisis”, but that is an ongoing, normal state of affairs. We have to be ready for a completely new demography, and that means coming to a new understanding of what it means to be European. That is something we can only achieve through culture.

*

In April 2019. 8 17

CHAPTER 1 - THE CONTEXTS

1.1 Together for a Common Future: Refugees and Migrants in Turkey

1.2 The Asylum System in the UK, and the Work of CARAS

1.3 Overview of Refugees’ Presence in Italy

1.4 Asylum in Germany

1.5 The French Migration Context in 2019

1.6 The Situation of Opera Padre Marella

19

CHAPTER 1 - THE CONTEXTS

TOGETHER FOR A COMMON FUTURE: REFUGEES AND MIGRANTS IN TURKEY

by İlke Şanlıer Yüksel, PhD (Director of Migration and Development Research CentreÇukurova University)

Turkey, besides its historical emigrant and more recent transit characteristic, is home to more than 5 million migrants; with a significant percentage coming from Syria, and given temporary protection status. In addition to a number of Afghan, Iranian or Iraqi asylum seekers, there are low skilled labour migrants coming from the Philippines, Uzbekistan and many other post-Soviet countries. Moreover, high skilled labour migrants and lifestyle migrants from various European countries settle mostly in metropolitan or coastal areas of Turkey. A relatively smaller number of tertiary level students is another migrant category in Turkey.

Turkey has for several decades been a major country of asylum, beginning with the 1979 regime change in Iran that led to an influx of asylum seekers. Additionally, the 1990-1991 Gulf War, as well as the US Invasion in Iraq and the subsequent chaos, has significantly contributed to the influx of refugees into Turkey. It is noteworthy that though Turkey is a signatory of the 1951 Geneva Convention and the 1967 Additional Protocol on the status of refugees, which obligates member countries to offer asylum to asylum seekers, with geographical limitation, it only provides refugee status for those who are coming from Europe. Consequently, up until September 2018, the non-Europeans’ asylum applications to Turkey were processed by UNHCR for the purpose of resettling them in a safe third country. Since then, this process has been executed by the Directorate General of Migration Management, which is an institute created in 2014 to register and process international protection applications. The Turkish migration regime has also not developed frameworks to offer full protection to non-European asylum seekers except granting them “conditional refugee” status.

From the late 1990s to the early 2000s, Turkey has seen an influx of refugees, ranging from 5000-6000 individual asylum applications per year. From 2007, these inflows of asylum seekers have increased significantly every year, with the years from 2011 to 2017 witnessing a remarkable rise from 18,000- 112,000. Worsened by the Arab Spring in Northern Africa that saw thousands of people moving to Southern Europe, as well as the political upheavals and civil wars in Syria; Turkey (and also other neighbouring countries like Lebanon and Jordan) was faced with a serious refugee influx that forced the country’s leadership to declare an ‘open door’ policy in 2011, and hosted thousands of Syrian refugees in various refugee camps in the regions bordering Syria.

Due to the high prolonged inflows of refugees from Syria, the camps were soon stretched to their limits forcing refugees to disperse across the country, especially in the cities near the Syrian border, which eventually spread to the larger urban settings including Izmir and Istanbul, where the refugees sought jobs in order to make a living. Initially, the government of Turkey called these refugees ‘guests’ because of the lack of legal frameworks defining them besides the expectation that these refugees would temporarily stay in Turkey. However, their protracted stay led to advocacy for the admittance of their fundamental human rights such as compulsory access to basic needs. The

21

challenges of providing assistance (such as access to health and housing) to the refugees were further made difficult by the sudden increase in the Syrian population in Turkey, compounded by the political uncertainty in Syria and the politicisation of the migration issue in Turkey. As a result, the refugees’ status was turned to ‘temporary protection’ in October 2014.

Although the existence of both the temporary and conditional protection statuses in Turkey partially helped safeguard the asylum seekers and refugees’ ‘non-refoulement’ rights, this was limited in the sense that it cannot afford the refugees or asylum seekers permanent residency rights, which forced them to seek asylum outside the borders of Turkey. Consequently, by the summer of 2015, there was en masse movement of refugees and asylum seekers from Turkey to Europe due to Turkey’s inflated number of refugees, transit migrants and asylum seekers engendered by lack of legal frameworks to provide them with the permanent provision of protecting rights as well as the poor living conditions. This led to an agreement signed between the EU and Turkey on 18 March 2016 to address the irregular passing of migrants as well as the overwhelming flow of smuggled asylum seekers and migrants travelling from Turkey (across the Aegean Sea) to the Greek Islands. It was agreed that Greece be allowed to return to Turkey all the new irregular immigrants who arrive. However, this agreement has brought more harm than good for the refugees and asylum seekers who are left more deprived and vulnerable. Due to the foregone proof, it is clear that Turkey today has become an immigrant and transit country for the refugees and asylum seekers, demonstrated by higher number (3.61 million) of Syrian refugees in June 2019 , as well as the over 600, 9 000 irregular migrants (who are not Syrians) seeking residence in Turkey.

Eight years after they first began to arrive in Turkey, Syrian refugees live in severe conditions characterised by instability, precarity and lack of access to rights due to temporary nature of their status. Consequently, these conditions, and the protracted flow of migrants to Turkey as well as from Turkey to Europe, leave all humanitarian migrants vulnerable to human rights violations and increasing social tension as they become targets of discrimination and “other”isation. All of these issues need to be addressed in a range of aspects, including socio-cultural dimensions along with politico-legal and socioeconomic scopes.

As long as refugees lose their lives making an attempt to achieve a secure place and a decent standard of living, we must work collectively to raise a society that works together for the well-being of all its members, strives to reduce inequalities and avoids marginalisation. As members of the academic community and civil society, we will continue to build pathways to create a sense of belonging, participation, recognition and legitimacy for all, along with protecting the human rights of refugees inside and outside Turkey, working with partner countries and organisations. There are many areas in social life such as civil solidarity, commitment to neighbourhood life, cultural and communication practices where we can build the coherence between individuals and groups with different histories, cultures and identities. We can only benefit from the potential of social differences by respecting diversity. This can only be achieved by building long-term partnerships in cooperation with local authorities, local institutions and most importantly with those who had to leave their homeland to search for new homes.

Our work must continue.

https://www.goc.gov.tr/icerik6/gecici-koruma_363_378_4713_icerik

retrieved on 20 June 2019. 9 22

THE ASYLUM SYSTEM IN THE UK,

AND THE WORK OF CARAS

by Eleanor Brown (Managing Director - CARAS)

Refugees arrive in London from a diverse range of countries and with a whole host of experiences of forced migration behind them. Many have made exceptionally long and difficult journeys overland, forced into hiding and travelling by night, and at the mercy of traffickers and agents who control the routes.

Only a few come in via planned routes on resettlement schemes or for family reunion. The vast majority who we see at CARAS are young, alone and at the end of a long and traumatic journey which has seen them cross continents, conflict zones and dangerous seas, surviving to reach safety and begin the slow and often painful task of rebuilding a life. At CARAS, we support refugees and asylum seekers from conflicts in South Sudan, Syria, Kashmir and Palestine; people fleeing political and religious persecution in Eritrea or Iran; and children fleeing forced recruitment into militia including the Taliban in Afghanistan, forced marriage, or FGM.

On arrival in England, support is patchy and difficult to access. The type and level of support vary according to the age of the individual: adults receive very little support, currently limited to a weekly stipend, ‘no choice’ accommodation that could be anywhere in the country, and legal aid that covers 5 hours with a solicitor to make an asylum claim. Children arriving and making a claim alone have different provisions made for them. They are looked after under children’s law, rather than being viewed primarily as an asylum seeker. They will be allocated a social worker, and, depending on age, may be housed with a foster carer.

Support is very patchy: in London and the south east, and in the big cities, there are a patchwork of small community groups and charities who fill in the gaps in support. Whilst statutory support ensures that people have access to a bare minimum, there are still people who fall through the gaps. Homelessness and destitution are a common outcome for newly recognised refugees who are not given support to find employment or stable housing; English language lessons are not provided for asylum seekers; and, somewhat predictably, mental health care is not offered as part of a standard package of support. In a context of long-term austerity and the decimation of the public sector, coupled with long-running xenophobic narratives, the outcomes for asylum seekers could be desperate. The voluntary sector links together to counter this as best we can, offering things that help people feel fully human again. We aim to run holistic provision which supports people in their social opportunities, health and wellbeing, language and learning, and with support to understand and progress through the current challenges they face. We want to help build a thriving, outward looking, fully inclusive community which is able to welcome refugees and to see potential in everyone.

We aim to be a lively centre, full of warmth, welcome and an offer of belonging. We constantly learn from each other, and continue to develop positive responses that stand in contrast to the traumatic experiences of people in their countries of origin, on their journeys, and in the dehumanising and drawn out asylum process in the UK. We would like to have no need to exist, but whilst there are refugees facing isolation, exclusion and marginalisation in our local area we will be here.

23

CARAS seeks to show people who have sought refuge in the UK that they have value, and indeed enormous potential. We do not believe in acting on behalf of someone capable of independent action. To this end, all of our activities aim to support people’s ability to exercise assertiveness in individual and collective decision making, increase positive self-image and overcome stigma. This starts within CARAS: beneficiaries are involved in designing and improving projects and in our governance. CARAS is recognised by our partners for its best-practice model and inclusive approach to decision-making.

However, playing an active role within CARAS’ work will not achieve an integrated, healthy and harmonious society. We have to look outside into our community and across London to start to achieve this.

In a context of disempowerment and exclusion, the value of cultural initiatives is enormous. How can you be included in a society if you do not have access to the arts, to the sharing of cultures, to the development of enjoyment and learning? How do you be fully human if you cannot create, or be surprised, delighted and challenged by someone else’s creations? If you are an asylum seeker in London, your material needs are just about met, but there is no straightforward access to anything that goes beyond surviving, and no expectation that people need this.

We have been part of a wide range of cultural initiatives, sometimes working hard to secure access to places of high culture, and just often eagerly saying yes to thoughtful offers that come our way. CARAS has had the good fortune to be a contributing partner to an exhibition at the Museum of London, sharing our work on diversity and inclusion with thousands of people. In many ways more valuable though, are the smaller, more personal interactions and changes experienced by our beneficiaries when they are able to take part. We have had groups of women visit the V&A Museum as part of their English classes; young people interact with artefacts at the British Museum; and had aspirations projected onto the façade of the Royal Festival Hall as part of a giant art and poetry celebration. These have achieved more than we could within our own four walls: they have given outlets to people’s individual creativity, humanised them to the wider public, and given them access to experiences that any and every Londoner can (and should) have. We have also been part of much smaller scale projects, most recently working together with a youth arts organisation who have been bringing in a whole range of taster sessions related to the arts. One Monday morning saw staff return to an office where the windowsills were covered in small clay figurines made in a weekend youth group, showing beautiful representations of camels and humped cattle, bringing in a memory of home to our little corner of south west London, sparking conversation and serving as a bridge between people, places, and time.

All of these things, from the very small act of picking up a paintbrush, writing a few words, or making a clay model, all the way through to having work showcased at a national cultural institution change both how refugees see themselves and how they are seen. Dialogue and equal participation are fundamental to processes of integration. Partnership with Border Crossings has been one of our longest standing and most fruitful relationships. We have written multilingual plays that being in ideas from children, volunteers and parents; looked at identity and representation in photography; taken part in celebrations of indigenous arts; and explored intercultural, multi-disciplinary approaches to refugee inclusion across Europe. THE PROMISED LAND has given us the chance to step back from being immersed in refugee work and look carefully and

24

critically at expertise from other sectors, leaning on each other and challenging each other to think differently. It is rare that people who work in the voluntary sector have an opportunity to freely interact with such a range of other disciplines and over such a long timescale- two years of thoughtful challenge from academics, business people, public sector workers and artists.

AN OVERVIEW OF REFUGEE PRESENCE IN ITALY

by Angelo Pittaluga, Integration expert for UNHCR

In 2018, human rights violations, persecution, conflict, and violence continued to displace many, with some subsequently seeking international protection in Europe. Although arrivals were markedly down compared to the large numbers who reached Italy each year between 2014-2017, the journeys were as dangerous as ever. An estimated 2,275 people perished in the Mediterranean in 2018 – an average of six deaths every day. Furthermore, the Libyan Coast Guard stepped up its operations with the result that 85% of those rescued or intercepted in the newly established Libyan Search and Rescue Region (SRR) were disembarked in Libya, where they faced detention in appalling conditions (including limited access to food and outbreaks of disease at some facilities, along with several deaths).

Italy is at a complex juncture being a country of transit, a country of asylum and integration of refugees. By the end of 2018, UNHCR estimates that there were over 85,000 recognised refugees and beneficiaries of subsidiary protection permanently living in Italy. At the end of the year, the arrival of some new 25,000 persons by sea and an additional 15,000 by land/air was registered. Integration prospects for beneficiaries of international protection in Italy continue to be seriously limited, as a consequence also of the economic crisis of the last few years and the cuts to the welfare system, and constitute therefore one of the most problematic areas of the Italian asylum system. As the research published by the Bank of Italy in 2017 shows, refugees have much more difficulties in finding a job than both Italians and migrants with a residence permit. One of the most evident and negative consequences is the rising number of beneficiaries of international protection, including persons with specific needs such as families with children, who live in destitute conditions in spontaneous settlements or occupied buildings. At the end of 2018, the adoption of a new Law on Immigration and Asylum (L. 132/2018) introduced significant changes in the national asylum system, with a reform of the reception system and restrictive measures with particular regard to administrative detention of asylum seekers, cancellation and termination of international protection, abrogation of the humanitarian protection and limitation in the residence registration for asylum seekers.

Data taken from the last UNHCR report “Desperate Journeys”, downloadable here:

https://data2.unhcr.org/en/documents/download/ 67712#_ga=2.231035286.801729727.1551108428-1379606552.1551108428 and from UNHCR web operational portal

https://data2.unhcr.org/en/situations/mediterranean/location/5205

26

ASYLUM IN GERMANY

from the German Federal Office for Migration and Refugees

Who is a “refugee”?

The term “refugee” is often used in everyday language as a general synonym for people who have been displaced, but the law on asylum only understands it as covering recognised refugees in accordance with the Geneva Refugee Convention, that is individuals who are given refugee protection once their asylum proceedings have been completed. There are however three more forms of protection where a right to asylum can be granted, if they are applicable. As the authority responsible for implementing the law on asylum, the Federal Office distinguishes more precisely, that is between the following groups of individuals:

Asylum-seekers: individuals who intend to file an asylum application but have not yet been registered by the Federal Office as asylum applicants.

Asylum applicants: asylum applicants whose asylum proceedings are pending and whose case has not yet been decided on.

Persons entitled to protection and persons entitled to remain: individuals who receive an entitlement to asylum, refugee protection or subsidiary protection, or who may remain in Germany on the basis of a ban on deportation.

Asylum is a right that is protected by the Constitution in Germany. People who are displaced from other parts of the world, fleeing from violence, war and terror, are to find protection in our country.

When they arrive in Germany, displaced persons reach safe ground, frequently after been in danger for years. Having said that, they only have certainty as to whether they and their families may remain here permanently and work when their asylum application has been finally decided on.

The examination of asylum applications is one of the most important tasks performed by the Federal Office for Migration and Refugees. This is a responsible, demanding task, given that decisions are taken on people, in complex procedures, taking diverse competences and stringent legal frameworks into account.

In each individual case, highly-trained decision-makers from the Federal Office with considerable skills and experience decide whether an asylum application is justified, and whether one of the four grounds for protection enabling a person to remain in Germany applies.

This overview will provide you with the most important aspects of the asylum procedure, such as applicants’ personal interview, the steps taken in the decision-making process, recent activities to optimise procedures, as well as the place which the activities take up within a European context.

27

1: From arrival to the asylum procedure

All asylum-seekers arriving in Germany must report to a state organisation directly on arrival or immediately thereafter. They can do this as soon as they reach the border or later within the country. Anyone already reporting as seeking asylum on entry approaches the border authority. This authority then sends asylum-seekers on to the closest initial reception centre. Anyone who does not make a request for asylum until they are in Germany can report to a security authority (such as the police), an immigration authority, a reception facility or directly to an arrival centre or AnkER facility. Only then can the asylum procedure begin.

1.1: Arrival and registration

All individuals reporting as seeking asylum in the Federal Republic of Germany are registered. Personal data are recorded at this point. All applicants are photographed; the fingerprints are also taken of people aged over 14.

The recorded data are stored centrally in the “Central Register of Foreigners”. All public agencies which subsequently need them for their respective tasks have access to these data to the extent that they need them for their respective remits.

In a first step, the new data are compared with those already available in the Central Register of Foreigners, as well as with those of the Federal Criminal Police Office. It is examined amongst other things whether an initial application, a follow-up application or possibly a multiple application has been made. It is also investigated using a Europewide system (Eurodac) whether another European state might be responsible for carrying out the asylum procedure.

Asylum-seekers receive a proof of arrival (Ankunftsnachweis) at the reception facility or arrival centre which is responsible for them to prove that they have registered. As the first official document, the proof of arrival serves to document the entitlement to reside in Germany. And what is equally important is that it constitutes an entitlement to draw state benefits, such as accommodation, medical treatment and food.

1.2: Initial distribution and accommodation

First, all asylum-seekers are received in nearby reception facilities of the Federal Land in question. Such a facility may be responsible for temporary as well as longer-term accommodation.

Allocation to a specific reception facility is decided according to the specific branch office of the Federal Office processing the asylum-seeker’s respective country of origin: Asylum-seekers can be accommodated in reception facilities for up to six months, or until their application is decided on. They can however also be allocated to another facility during this period under certain circumstances, for instance for family reunification.

1.3 The competent reception facility

The competent reception facility is responsible for providing food and board for asylumseekers. They receive benefits in kind at subsistence level during their stay and a month -

28

ly amount of money to cover their everyday personal needs. The nature and amount of the benefits are regulated by the Asylum-Seekers’ Benefits Act (Asylbewerberleistungsgesetz). These include basic benefits for food, housing, heating, clothing, healthcare and personal hygiene, as well as household durables and consumables, benefits to cover personal daily requirements, benefits in case of sickness, pregnancy and birth, as well as individual benefits which depend on the particular case.

Benefits for asylum applicants are also provided in the follow-up accommodation (such as in collective accommodation or even a private apartment). More information is available from the responsible immigration authority.

1.4: Personal asylum applications

A personal application is filed with a branch office of the Federal Office (an arrival centre or an AnkER facility). An interpreter is available for this appointment. Applicants are informed of their rights and duties within the asylum procedure. They furthermore receive all the important information in writing in their native language.

The personal data are recorded during the application procedure, if this has not already taken place. Applicants are obliged to prove their identity if they are able to do so. Documents accepted include a national passport, as well as other personal documents such as birth certificates and driving licences. The Federal Office uses physical and technical document examination to assess the original documents.

The application is made in person as a rule. A written asylum application may only be filed in special cases, for instance if the individual in question is in a hospital or has not yet reached the age of maturity.

1.5: Residence obligation (Residenzpflicht)

Once their asylum application has been filed, applicants receive a certificate of their permission to reside (Aufenthaltsgestattung). This certificate serves as documentation vis-à-vis state agencies that they are asylum applicants, and proves that they are in Germany lawfully. Permission to reside is territorially restricted to the district (residence obligation) in which the responsible reception facility is located.

Persons with poor prospects to remain are obliged to live in the reception facilities until the decision is taken. If their asylum application is turned down as “manifestly unfounded” or “inadmissible”, this obligation for people to reside in a particular place then applies until they leave the country. They are not permitted to work during this period, and they may only temporarily leave the area designated in their permission to reside if they have permission from the Federal Office.

Persons with good prospects to remain may initially also only remain in the area designated in their permission to reside. They too need permission if they would like to temporarily leave this area. The residence obligation ceases to apply to them after three months. The residence area is then expanded to cover the entire country.

30

1.6: The personal interview

The personal interview is the applicant’s most important appointment within his/her asylum procedure. Organisations providing aid or charitable associations therefore offer advice when it comes to preparing for the interview. The Federal Office has also been implementing group information and individual counselling sessions on the asylum procedure at the AnkER facilities since August 2018.

It is the “decision-makers” at the Federal Office who are responsible for holding the interviews. They invite applicants to attend this appointment, where an interpreter will also be on hand.

Applicants absolutely must attend this appointment, or they must state in good time why they are unable to attend. If they do not do so, their asylum application can be turned down or the proceedings discontinued.

The interviews are not public, but they may be attended by an attorney or by a representative of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), and by a guardian in the case of unaccompanied minors. It is fundamentally possible for another person enjoying the applicant’s trust to attend as an advisor. This individual must be able to identify himself or herself, and may not personally be in the asylum procedure.

The objective of the interviews is to learn of the individual reasons for flight, to obtain more information and to resolve any contradictions. To this end, the decision-makers are familiar with the circumstances prevailing in the applicants’ countries of origin.

Applicants are afforded sufficient time during the interview to present their respective reasons for taking flight. They describe their biographies and situations, tell of their travel route and of the persecution which they have personally suffered. They also assess what would await them were they to return to their country of origin. They are obliged to state the truth at all times and to provide any evidence which they have been able to obtain. These may be photographs, documents from the police or other authorities, and possibly also medical reports.

The descriptions are interpreted and minutes are taken, and are then translated back for the applicants after the interview. This enables them to add to what they have said, or to make corrections. They are then presented with the minutes for them to approve them by signing them.

The Federal Office decides on the asylum application on the basis of the personal interview and of a detailed examination of documents and items of evidence.

The fate of the individual applicant is decisive. The decision is reasoned in writing, and is served on the applicant or the legal representative, as well as on the competent immigration authorities.

Safe third countries

Recognition of entitlement to asylum is ruled out if an individual enters via a safe third country. The German Asylum Act (Asylgesetz) defines the Member States of the European Union, as well as Norway and Switzerland, as safe third countries.

31

The right of asylum

In accordance with Article 16a of the Basic Law (Grundgesetz – GG) of the Federal Republic of Germany, persons persecuted on political grounds have the right of asylum. The right of asylum has constitutional status as a fundamental right in Germany. At its core, it serves to protect human dignity, but it also protects life, physical integrity, freedom and other fundamental human rights. It is the only fundamental right to which only foreigners are entitled.

Refugee protection

Refugee protection is more extensive than entitlement to asylum, and also applies to persecution by non-state players. On the basis of the Geneva Refugee Convention, people are regarded as refugees who, because of a well-founded fear of being persecuted by state or non-state players for reasons of race, religion, nationality, political opinion or membership of a particular social group, are outside their country of origin and nationality, or as stateless individuals are outside of their country of habitual residence. These criteria also apply if they are unable or, because of a well-founded fear, are unwilling to avail themselves of the protection of their country of origin.

Subsidiary protection

People are entitled to subsidiary protection who put forward substantial grounds for the presumption that they are at risk of serious harm in their country of origin and that they cannot take up the protection of their country of origin or do not wish to take it up because of that threat. Serious harm can originate from both governmental and non-governmental players.

The following are regarded as constituting serious harm: the imposition or enforcement of the death penalty, torture, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment, a serious individual threat to the life or integrity of a civilian as a result of arbitrary force within an international or domestic armed conflict.

Reasons for not qualifying for protection

The three forms of protection mentioned above cannot be considered if reasons for not qualifying apply. These include: If an individual has committed a war crime or a serious non-political criminal offence outside Germany, has breached the goals and principles of the United Nations, is to be regarded as a risk to the security of the Federal Republic of Germany, or constitutes a danger to the public because he/she has been finally sentenced to imprisonment for a felony (Verbrechen) or a particularly serious misdemeanour (Vergehen).

National ban on deportation

A person who is seeking protection may not be returned if return to the destination country constitutes a breach of the European Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms (ECHR), or a considerable concrete danger to life, limb or liberty exists in that country.

32

A considerable concrete danger can be considered to exist for health reasons if a return would cause life-threatening or serious diseases to become much worse. This is not contingent on the healthcare provided in the destination state being equivalent to that available in the Federal Republic of Germany. Adequate medical treatment is also deemed to be provided as a rule if this is only guaranteed in a part of the destination country.

If a national ban on deportation is issued, a person may not be returned to the country to which this ban on deportation applies. Those concerned are issued with a residence permit by the immigration authority.

A ban on deportation can however not be considered if the person concerned could depart for another country, and it is reasonable for them to be called on to do so, or if they have not complied with their obligations to cooperate.

Quoted from: The Stages of the German asylum procedure. An overview of the individual procedural steps and the legal basis

Valid as of: 2/2019; 2nd updated version

Published by the Federal Office for Migration and Refugees, D-90461 Nürnberg

Reference source: Publications office of the Federal Office for Migration and Refugees www.bamf.de/publikationen

The most actual information can be accessed at: http://www.bamf.de/DE/Fluechtlingsschutz/fluechtlingsschutz-node.html www.bamf.de

33

THE

FRENCH MIGRATION CONTEXT IN 2019

by Corinne Torre (Chef de Mission France, Médecins sans Frontières)

translated by Anne Kerisel

The first quarter of 2019 mirrors the migration policy of 2018 and furthers the actions already taken by the French Government: an increase in the number of police at the French borders, more controls across the country, a deterioration in the situation of homeless migrants, the dismantling of unofficial camps in order to prevent settlement, increased pressure on citizens trying to help, criminalisation of humanitarian organisations, and the implementation of a biometric file for unaccompanied minors.

These policies, based on deterrence and the externalisation of borders, have a direct impact on people's health (both migrants and carers), which is deteriorating as a result of the precarious living conditions and psychological pressures that they endure.

Despite the policy of deterrence, “123,625 asylum applications were received at OFPRA during the year 2018 (including first-time asylum applications, requests for file reviews and re-openings, and accompanying minors applications): an increase of 22.7% on the previous year. The rate of increase is rising compared to 2016 (+7.1%) and 2017 (+17.5%).” 10

The region Ile-de-France, where asylum applications are registered, saw a rise from 36% in 2017 to 46% in 2018. The increase in the number of applications partly explains the problems in the reception of migrants in Paris, and the continued existence of unofficial camps. However, lack of will from the Prefecture to anticipate these arrivals and to open reception structures leads to great instability and a feeling of "being invaded". Of 123,625 applicants, only 41,400 were granted asylum seeker status in 2018.11

Unaccompanied minors

In 2018, 742 unaccompanied minors applied for asylum (33% of them Afghans): an increase of 24.2% on 2017 (591) and of 100% on 2013 (367). If we compare these figures with the number of requests for protection made to ASE (the National Child Welfare Department) the numbers are extremely low. 40,000 minors arrived in France in 2018, and only 17,022 of them were granted protection by ASE. As of 15 March 2019, 5,692 minors were under the care of ASE.

In March 2019, several associations, including MSF, brought an action against the use of biometric file. It should be emphasised that its main aim is to stop the movement of minors to other Départements where they may not be recognised as minors, without calling into question the assessments. Any minor arriving in a Département must now first file fingerprints at the Prefecture before being evaluated. This is contrary to the law on protection of minors.

During that period of time, we (national associations) have set up an observation system in the evaluation centres and prefectures of all the French Départments, in order to gather testimonies on the use of biometric files and its consequences. This system requires the help of volunteers and the development of relationships between local associations. Only Paris and Seine Saint Denis have so far refused to use the biometric file.

34

(OFPRA Report 2018) 10 (Eurostat report 2018) 11

Internal borders of the EU

On 19 March 2019, the European Court of Justice delivered an important judgment on the French authorities' practices at internal borders. The ECJ had received a request for a preliminary ruling in the case of a Moroccan national arrested at the Franco-Spanish border in June 2016 and taken into police custody.

The judgment had two important stipulations:

- It is not possible to consider an internal border as an external border, even if temporary controls are restored, as has been the case in France since 2015.

- The Return Directive is applicable at internal borders and people who are stopped at internal borders must therefore benefit from the guarantees ensured by this directive.

This judgment is extremely interesting for the case of France, which in 2015 re-established temporary controls (actually no longer temporary) leading to tens of thousands of refusals of entry, all illegal according to the ECJ. The Cimade report “Inside, outside, a Europe that is closing in” points to an increasingly impaired access to rights. Activists in the field, particularly on the Franco-Italian and Franco-Spanish borders, are closely monitoring the situation to see whether this judgment leads to changes in practices.

Hauts de France (Calais, Grande Synthe, Boulogne)

On 28th February the European Court of Human Rights (ECHR) condemned France for inflicting “degrading treatment" on an unaccompanied minor from Afghanistan when he was in the country between 2015 and 2016. This child, who was eleven years old at the time, had not been taken into care by the authorities. He had lived for about six months in the slums of Calais, before moving to England, where he is now living. Too bad that the judgement came three years too late!

Refugees seeking to go to England live in very small camps in Calais (there are between 500 and 600 people, mainly from Afghanistan, Eritrea and Sudan). There are also refugees in Grande Synthe, where they live in an undersized gymnasium and in camps (between 500 and 600 people, mainly Iraqi and Kurds, and a larger number of minors). The figures can vary significantly.

Relationships with local government vary a great deal according to location:

- In Calais: while there is strong opposition and no dialogue with the City Council, there are regular contacts with the Prefecture (even if there are disagreements). After legal battles, the Prefecture is now providing water, access to toilets and showers, day centres and cold weather protection. The emergency in Calais is ongoing. Despite constant changes in the volunteer presence, there are advocacy and litigation actions supported by an cross-NGO collective (PSM).

- In Grande Synthe: there is ongoing contact with Mayor Damien Carême, but no contact with the State, which simply lets the welcoming (but financially limited) City Hall do its work. The good relationship with the mayor prevents the use of more confrontation litigation (as undertaken in Calais against an openly hostile City Council). There are active NGOs involved in advocacy and litigation.

In all the coastal areas, there is a huge police presence, violence and expulsions: between 2 to 5 expulsions per site per week. The watchword is “no settlement".

Menton- Ventimiglia

According to figures made public by the Prefect of Alpes-Maritimes, the number of arrests in this French department has fallen by 40% over the past year. In 2018, 244 smugglers were brought to justice and 29,600 migrants were arrested at the French border. At the same time, 1,960 unaccompanied minors were taken into care by the reception services of the Département Council, after being arrested at the French border.

36

There are many different nationalities, and many people who have lived in Italy but who want to leave for various reasons: the expiry of their residence permit, the lack of employment, fear of new policies leading to tensions in Italy, etc. There are also many people arriving from the Balkan route (Pakistani, Iraqi, Afghan) but also people from the Maghreb and Eritrea who entered Europe after going through Egypt.

Young people who have just turned 18 in Italy go to Ventimiglia, as well as a large number of families (many of them Nigerian nationals, checked at the association offices in Nice) who can no longer renew their residence permit in Italy and/or are expelled from the SPRAR (System for Protection of Asylum seekers and Refugees) as consequences of Salvini’s new legislation.

Every day, migrants continue to be turned back at the French border , and there are 12 many violations of asylum rights, and the right to be protected as children. Some people are detained without taking into account any legal framework. Since February 2019, people have been able to keep a copy of any refusal of entry, and we can see that on many of these the statement that the holder “is considered a danger to public order, internal security, public health or the international relations of one or more Member States of the European Union" has been ticked by the French police as an expedient.

The observations organised by CAFI (Amnesty, Cimade, MDM, MSF, Secours Catholique) alongside voluntary networks continue, and allow legal proceedings to be initiated against the practices of the Prefecture. This process is developing at several levels: the monitoring and transmission of information, the organisation of collective actions for the purpose of litigation, communication and advocacy, support for local activists, and the implementation of shared analysis at national level, enabling the public to intervene more powerfully in favour of migrants at the Franco-Italian border. We would like to develop closer links with activists facing the same problems at other borders: links with the PSM association on the Franco-British coast, and on the Franco-Spanish border.

Briançon

Today, the people who arrive are mainly adults, while 40% of arrivals in 2018 were unaccompanied minors. Nationalities and profiles are changing due to the situation in Italy where migrants fear deportation. They arrive in France with the aim of settling, and stay several weeks in Briançon. This leads to housing problems and challenges for the local council.

The Franco-Spanish Border

From the summer of 2018 until December, there could be 40 to 100 arrivals per day in Bayonne (up to sometimes 140 daily arrivals during summer), while at the beginning of this year, it was closer to 100 arrivals per week. The permanent control point is the train station in Hendaye, where everyone without the right papers is sent directly back to Spain.

Police are also numerous at the entrance to Behobia (in France, the neighbouring town of Hendaye), a busy road crossing point when arriving from Irun. However, car checks are very light or non-existent, and the most popular migrant route is by car, from Irun Bilbao, or San Sebastian.

Regarding the practices of the border police, activists report discriminative checks, swift deportations, including of unaccompanied minors, sometimes with a refusal of entry. Migrants report verbal abuse by police officers, but no physical abuse.

12 37

These observations were made by the Kesha Niya association.

On the French side, the situation is slightly different. First of all, there is the question of the reception in Bayonne where people arrive every day. As in 2018, migrants leave the city by bus after a few days, but police officers check the buses on their arrival in cities like Bordeaux, Toulouse, Pau, etc. and sometimes expel them back to Spain (or take them to CRA, the French administrative retention centres).

Paris Ile de France

At the beginning of January 2019, more than 2,200 migrants were living in camps in the north of Paris and in the city of Saint-Denis (on Boulevard Wilson). People are pushed back to the Portes on the Paris ring road: Porte de la Chapelle, Porte de la Villette, Porte d'Aubervilliers and Porte de Clignancourt. This policy, based on keeping migrants invisible, works perfectly on the outskirts of the city.

The Paris City Hall and the Prefecture continue to place the responsibility for the provision of shelter on others, despite being called by NGOs to intervene urgently in order to respect the dignity of the migrants. There are no showers, no sanitary facilities, no access to healthcare and food distribution is problematic.

In the first quarter of 2019, there were 18 evacuations, involving 2224 people, 240 of whom (10.8%) were identified as vulnerable (e.g. women, children, people with critical health conditions). As in 2017, the city of Paris organised a night of solidarity: 3,622 people were counted living on the streets, an increase of 600 from the previous year, despite the evacuations and the places of shelter “created" as a consequence.

March 31st marks the end of the winter truce: there is a risk of increased numbers of people living on the streets. According to the Federation of the Actors for Solidarity (FAS) about 8,000 homeless people and 1,500 migrants were at risk of being put back on the streets. Of the 14,000 places opened under the winter plan, the French State announced that 6,000 would be offered over the long term.

Advocacy organisations

• CAFFI (Amnesty, Cimade, MDM, MSF, Secours Catholique) Organisation and preparation of a mobile team day at the Franco-Italian border, along with Tous Migrants + CAFFIM special day event on the situation at the border (15 and 16th March.) Joint press article drafting to denounce the criminalisation, unlike elsewhere in France, of the mobile teams at the FFI, https://www.lejdd.fr/Societe/tribune-sauverdes-vies-nest-pas-un-delit-dans-les-montagnes-comme-ailleurs-3870746

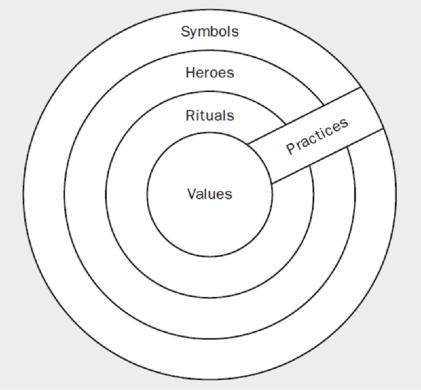

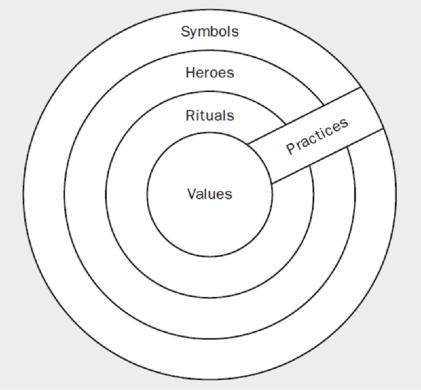

• MNA (Unicef, Secours Catholique, LDH, SAF, MDM, Gisti, la Cimade and MSF)