‘I Live, I See’: An Important Collection of Soviet Non-conformist Art from Italy

Paris | 11 - 18 September 2024

‘I Live, I See’: An Important Collection of Soviet Non-conformist Art from Italy

Paris | 11 - 18 September 2024

EXHIBITION

Bonhams Cornette de Saint Cyr 6 av Hoche, 75008 PARIS

11 - 18 september

VIEWING

Wednesday 11 September: 10am – 6pm

Thursday 12 September: 10am – 6pm

Friday 13 September: 10am – 6pm

Monday 16 September: 10am – 6pm

Tuesday 17 September: 10am – 6pm

Wednesday 18 September: 10am – 6pm

ENQUIRIES

Daria Khristova +44 (0) 20 7468 8338 daria.khristova@bonhams.com

ILLUSTRATIONS

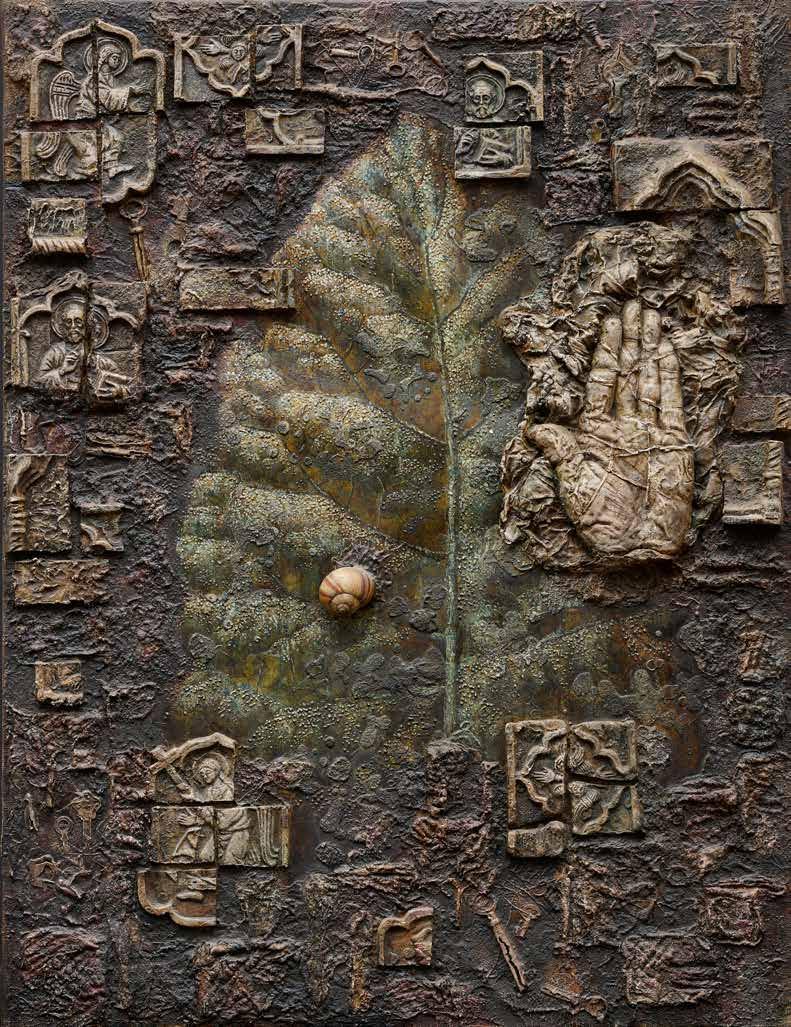

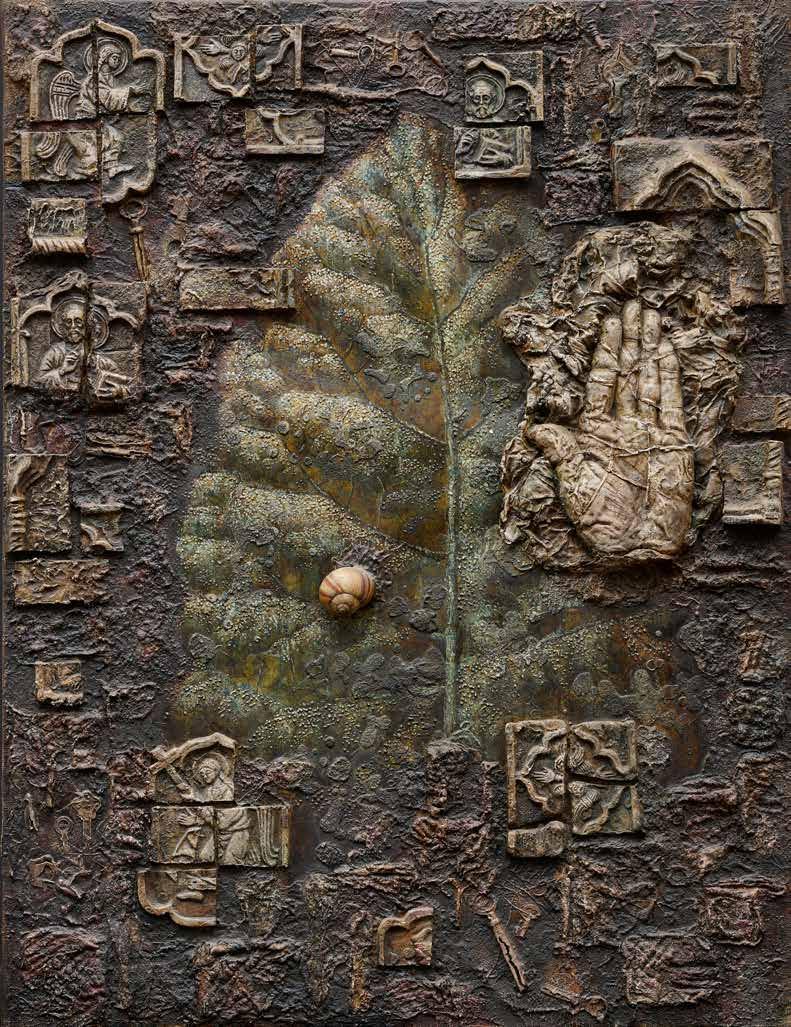

Front Cover:

DMITRY PLAVINSKY (1937-2012)

Landscape of the walls of an ancient church signed in Cyrillic, titled and dated ‘72’ (verso) collage on canvas

80 x 62 cm

Back Cover: YURI ZHARKIKH(BORN 1938) Consecration signed in Cyrillic, titled and dated ‘1974’ (verso) oil on canvas

95.6 x 78.6 cm

The phrase ‘I Live, I See’ is drawn from a collection of poems by Vsevolod Nekrasov, a pivotal figure in Soviet concrete poetry and conceptualism. Nekrasov, like many artists presented in this important collection, was a key player in the non-conformist, underground art scene that flourished despite state repression in the Soviet Union. While rooted in the Soviet experience, ‘I Live, I See’ transcends its original context. It speaks to the universal role of the artist as an observer and truth-teller, resonating with viewers regardless of their familiarity with Soviet history.

The so-called Soviet unofficial or non-conformist art was a striking social phenomenon of the second half of the twentieth century. It was the result of many circumstances that surrounded the complex political and socioeconomic situation of post-war Soviet Union. The birth of the non-conformist movement can be traced back to the death of Stalin and the beginning of Khruschev’s “Thaw” (1956 – 1966), when the Iron Curtain lifted. Interestingly, unofficial art was never a unified movement or group; artists were united by their rejection of a state-imposed art movement rather than any other defining characteristics and so were grouped together without forming a school. They were not bound by any manifesto and took multiple paths.

The resolution of the Central Committee of the All-Union Communist party ‘On the re-structuring of literary and artistic organisations’, made on 23 April 1932 signposted the end of the avant-garde experiments of the 1910s and 1920s. It abolished all artistic groupings in the country and indicated the beginning of the removal of all sorts of freedoms and possibilities for artistic experiments. Artistic groups were replaced with a powerful and monopolistic Union of Soviet Artists that became a strong instrument of ideological control.

The authorities intervened not only in themes and content, but also in the form and style of works of various mediums of art. The birth of Socialist Realism outlined a new framework and norms in Soviet art. The restrictions were especially harsh from 1930s to early 1950s with even Impressionism being declared “outlawed” for Soviet artists. Artists were expected to draw their inspiration from the art of past eras: from Antiquity to the realism of the 19th century, and especially the didactic art of Wanderers. The formula of the style was made in 1934 during the first Writer’s Congress, seeking ‘the truthful depiction of reality in its revolutionary development’. That meant that all political, religious, erotic and finally ‘formalistic’ art, which included abstraction, cubism, surrealism and any type of experimental art were no longer accepted. Inspired by Communist ideology, the doctrine of Social realism was restricted any sort of creative freedom, imagination and more importantly, individualism.

The aims of Social Realism and even some of its stylistic features, however, were not exclusive to the Soviet Union. Similar processes emerged in totalitarian states across the world, including Nazi Germany, Mussolini’s Italy and Communist China.

Despite the announcement of the official style, many artists worked behind closed doors. Some ignored the official order, and others refused to become members of the newly created Union; they chose to hide, to leave public artistic life. None of these artists, however, openly sought conflict with the political authorities. As a result, terms such as dissident or underground have been eschewed for this underground art, largely described more neutrally, as ‘unofficial’. These artists worked instead as art teachers in schools and children’s art clubs, as well as designing books. Behind closed doors, however created different art, which they wanted. Their works did not appear in public exhibitions and were known to a very small circle of close friends. Others, who became members of the Union of Soviet Artists formed an opposition within the Union. They began to be called ‘Left MOSKH’, trying as much as possible to remain faithful to their understanding of the arts. Some of the major masters, laureates of State and Stalin Prizes, led a double life -- they painted pompous canvases on the themes of the revolution for exhibitions, whilst in private, they created lyrical landscapes and still lives giving vent to the true direction of their creativity

In his book, Unofficial art from Soviet Union Igor Golomshtok cites: “the Italian journal Quaderni Milanesi that wrote in 1962 about artists working in a different totalitarian regime: ‘Fidelity to culture was intrinsically antiFascist/ The painting of still-lifes with bottles or the writing of hermetic verse were in themselves a protest’. This sentence defines precisely the chief internal impulse of these Soviet artist. The craving for culture, the urge to re-forge the broken links of time, to break the interdictions and to bridge the artists traditions of past and present - all this was a form of protest against the cultural vacuum of Social realism…” (Unofficial art from Soviet Union, London, 1977, p.87)

The turning point of the artistic thaw was the grandiose exhibition ‘30 Years of the Moscow Artists’ Union’, held at the Moscow Manege on December 1, 1962. The historic show exhibited modern artists, including Steinberg, Drevin, Falk, Neizvestny and Yankilevsky, who were not even members of the Union. Inspired by Khrushchev’s liberalisation, artists had high hopes, but it was also the year of the Novocherkassk Massacre and the Cuban Missile Crisis. The general secretary Nikita Khruschchev was dubious, and lacking understanding in art, he called the experiments of the young painters” charlatanism and pornography”. After viewing the exhibition, Khrushchev declared: “In art I am a Stalinist”. The thaw limit had been reached. As a result, by the end of sixties all liberal writers and artists were deprived of any opportunity to exhibit their work; their names were erased from the pages of newspapers. Artists now had little choice but to comply or resist the official movement.

Many of them continued to work, and their pictures, whilst considered undesirable by the state, didn’t lead to prosecution as long as their activity remained private. At the same time, many non-conformist artists showed their work to foreigners – journalists, diplomats, ambassadors, foreign students, all of whom became the principal viewers and buyers of unofficial art.

Non-conformist art is striking in its diversity, versatility and terminological elusiveness. Working in different styles and having different backgrounds as well as life circumstances, all artists had had one thing in commonthe art they created was individual, withstanding the pressure of power and society. The formal characteristics by which their art was separated from the official artists, varied, including religious content, abstraction and anti-Soviet themes. Although the former was quite common, the latter was not.

The first community of unofficial artists took shape in Lianozovo, a district of Moscow, as early as the mid-1950s. The group formed around Oscar Rabin and his teacher Evgeny Kropivnitsky. Another group was established in Moscow in the flat of I. Tsirlin and a few more in Leningrad.

The years from 1960 until the first half of the 1970s were a period of consolidation of unofficial artistic forces. The Bulldozer Exhibition in 1974, became a milestone for the unofficial movement. Oscar Rabin had the idea of an open exhibition as far back as 1969, when he realised how limited opportunities were in official institutions. Initially, few supported the idea, however, after years of rising tensions between artists and the government, it was decided that the exhibition should be held. The so-called ‘First Autumn Viewing of Paintings in the Open Air’ or Bulldozer Exhibition took place in Moscow on 15th September 1974. Fourteen unofficial artists exhibited roughly forty works. After the exhibition had been set up, authorities sent in the police force, including bulldozers and water cannons, causing unprecedented damage to the paintings and ultimately halting the exhibition. In an interview with The Guardian in 2010, Rabin recalled the event: “It was very frightening … The bulldozer was a symbol of an authoritarian regime just like the Soviet tanks in Prague”. Two of his own paintings - a landscape and a still life - were among those flattened by bulldozers or burned by the invading KGB. There were no political themes to the painters’ choice of subject, but they did not conform to the Soviet ideal of realism in art. “I chose those images consciously because I did not want to annoy the authorities more than necessary by showing work that was too provocative,” he said.

Despite its outcome, the exhibition attracted the attention of the foreign press, and many artists became famous overnight. This important event launched a series of exhibitions by non-conformist artists. Two weeks after the Bulldozer event, the authorities permitted a one-day exhibition in Izmaylovo Park, followed by another one organised by Oscar Rabin on the grounds of the Exhibition of Achievements of the National Economy (VDNKh). In the late 1970s, the art scene was dominated by flat exhibitions in both Leningrad and Moscow.

The first generation of unofficial art - the Lianozov group and, in general, the artists of the sixties - persistently returned to the heritage of the avant-garde and art of the 1920s - early 1930s, becoming a connecting bridge between eras. In the seventies, the second generation felt much more confident in tradition. Some artists continued to develop

pictorial elements, others turned towards conceptual art, while still more saw possibilities in an ironic play with Soviet realities. Artists like Dmitry Plavinsky and Vladimir Yankilevsky took a metaphysical path in their artistic development; Ilya Kabakov and Erik Bulatov adopted conceptual art. However, some artists like Anatoly Zverev and Vladimir Yakovlev could not fit into any movement due to their completely unique artistic styles.

Ultimately, unofficial Russian art was more familiar to Western viewers than Soviets. The first exhibition of non-conformist art abroad took place in the 1960s. In 1967, the Galleria Il Segno in Rome presented the exhibition ‘Pittori moscoviti’ with works from the Glezer Collection. The same year, another exhibition called ‘Anticonformists’ took place in France. More followed in Florence, Stuttgart, Frankfurt and Lugano. Unofficial artists were also included in the Biennale of Dissent which was held from 15 October to 17 November 1977 in Venice (1977 was a year between the main exhibitions), marking the 60th anniversary of the October Revolution.

The exhibition was curated by Italian curators Eniriko Crispolti and Gabriella Moekada, and the programme of the Biennale of Dissent was varied and consisted of three exhibitions. Events included a festival of Eastern European cinema, as well as conferences, a retrospective dedicated to Sergei Parajanov’s filmography, all centred around, the exhibition ‘New Soviet Art: An Unofficial Perspective’, held at the Sports Palace near the Arsenale (Arsenal). Soviet art included the work of artists from the Lianozovsky group to Sots Art, metaphysicians, and abstract artists. A total of 90 artists participated in the exhibition. The Dissidents’ Biennial was unusual not only due to of its political nature but also because of its curatorial programme. To show as much unofficial art as possible, curators presented the works themselves as well as photographs of works that remained in the USSR. The Biennial of Dissent was an important event that constituted one of the very few cases of cultural representation of dissidence at an international level, revealing the deep-rooted problems in contemporary politics.

The present collection began in the 1970s when the collector established contacts within the non-conformist art scene in Moscow. He became acquainted with and admired many artists. After visiting numerous ‘apartment’ exhibitions, which have now become legendary, the collector began acquiring works by non-conformist artists. Over the decades, the collection has grown to become an important representation of the non-conformist movement, showcasing a variety of mediums and styles. It provides a good overview of non-conformist developments in the USSR and includes renowned names, such as Oscar Rabin, Evgeny Rukhin, Alexander Kharitonov, Dmitry Plavinsky, Vladimir Weisberg and many others.

This collection stands as a testament to a unique period in history, preserving the legacy of artists who stood against oppression and telling a broader story of artistic resistance in the Soviet Union.

Russian stove

signed in Cyrillic and dated ‘1974’ (lower left); further titled, dated and numbered N566 (verso) oil on canvas

80 x 104cm

Oscar Rabin stands as one of the pillars of Soviet nonconformism, occupying a unique and pivotal position among the painters of the 1960s and 1970s and being the unofficial leader of the Lianozovo Group. His influence on the unofficial art scene of the Soviet Union cannot be overstated, as it was his workshop in Lianozovo that became the epicentre of a movement that would challenge the artistic and political status quo of the time. It was also Oscar Rabin who came up with the game changing idea of having an open-air exhibition, allowing the work of non-conformist artists to be shown to the public, even if it went against the policies of the Soviet Union.

The Lianozovo workshop, under Rabin’s leadership, became a hub for some of the artists. This collective included a remarkable array of artists and poets, each contributing their unique perspective to the movement. Among them were Lev Kropivnitsky, known for his adherence to avant-garde ideas; Lidia Masterkova, with her bold abstract compositions; Vladimir Nemukhin, famous for his card motifs; Nikolai Vechtomov, with his cosmic abstractions; and the poet Vsevolod Nekrasov, whose experimental verses complemented the visual arts. These figures, along with many others, formed the core of a movement that would challenge Social Realism.

What set Rabin apart, even within this group of innovators, was his creation of a unique pictorial language that found its expression in metaphysical landscapes. These paintings made a strong impression with their crude, vivid colours and their bold imagery. Instead of idealised images of Soviet prosperity or portraits of leaders, Rabin painted suburban slums, abandoned houses and desolate streets. He filled his urban vistas with an eclectic array of objects, transforming them into complex, layered representations of the artist’s inner world. Through this distinctive approach, Rabin managed to create works that were simultaneously deeply personal and universally resonant.

The objects populating Rabin’s canvases were not random; they were carefully chosen symbols, each contributing to the overall narrative of the piece. A loaf of bread, a bottle of vodka, a newspaper clipping - these everyday items took on new significance in Rabin’s hands, becoming powerful commentaries on Soviet life, human existence, and the artist’s own experiences. Rabin’s artistic language, with its fusion of urban landscapes and symbolic objects, allowed him to express complex ideas and emotions that might otherwise have been impossible to convey openly in the restrictive artistic climate of the Soviet Union.

What makes Rabin’s work particularly powerful is its grounded nature. His images are not exalted or idealized; they are “earthly”. This connection to the lived experiences of Soviet citizens, gave Rabin’s work an authenticity and resonance

that was lacking in the official art of Social realism. The texture of his paintings is complex and multifaceted, often achieved through unconventional methods. Rabin was known to mix sand into his paint or use wax or dry whites to create unique surface effects. This deliberate roughness in execution underscores the raw, unvarnished nature of his subject matter. A hallmark of Rabin’s style is his use of thick black lines to outline buildings and objects. This technique not only defines forms but also adds a sense of weight and solidity to his compositions. The overall effect is one of a certain “barrenness”a quality that remained consistent throughout his career, from his early days in the barracks of Lianozovo to his later period in Paris.

Oscar Rabin’s painting “Russian Stove” stands as a powerful example of Soviet non-conformist art. Created in 1974, the same year as the famous Bulldozer Exhibition, this work encapsulates the tension between unofficial artists and the state authority that defined the era.

From the outset, “Russian Stove” displays all the hallmarks of Rabin’s distinctive style, one which he developed early in his artistic career. The painting’s composition is dominated by the eponymous stove, rendered in depressive, gloomy, and distorted tones. This central element, a staple of traditional Russian homes, serves as a potent metaphor for Soviet society itself - twisted, oppressive, yet containing within it the potential for warmth and illumination.

Stylistically, “Russian Stove” exemplifies Rabin’s mastery of colour and texture. The palette is predominantly dark and nearly monochromatic, with brown tones dominating the canvas.

Rabin’s masterful use of contrast is evident in the juxtaposition between the sombre tones of the stove and the bright image of the fire within it. This stark contrast likely symbolizes the persistent flame of hope and resistance burning within the bleak reality of Soviet life. The fire not only provides visual contrast but also serves as a focal point for the painting’s deeper meanings.

The striking and symbolic detail of the work is a burning newspaper clipping visible in the flames, bearing the provocative headline “Who are the arsonists?”. This element resonates deeply with Rabin’s own experiences and the broader struggles of non-conformist artists. It poses a loaded question: Who truly are the instigators of change or destruction in society - the artists who challenge the status quo, or the authorities who suppress free expression?

The timing of the painting’s creation adds another layer of significance. 1974 marked the year of the Bulldozer Exhibition, a pivotal moment in the history of Soviet non-conformist art when authorities violently suppressed an outdoor exhibition of unofficial art. By embedding references to the fire and provocation, Rabin reminds the viewer of the ongoing confrontation between freedom and the control of the state.

Picnic on the moon signed in Cyrillic and dated ‘72’ (lower right); further titled, dated and numbered ‘512’ (verso) oil on canvas

80 x 100 cm

Safrontsevo village

signed in Cyrillic and dated ‘1974’ (lower left); further titled, dated and numbered N593 (verso) Oil on canvas

Untitled

signed in Cyrillic and dated ‘1970’ (lower right) oil on canvas

100 x 97 cm

Exhibited Venice, La nuova arte sovietica. Una prospettiva non ufficiale a cura di Enrico Crispolti e Gabriella Moncada (Il Dissenso culturale [the Dissident Biennial]), 15 October - 17 November 1977, N1 (according to label on verso)

Literature

Exhibition catalogue La Nuova Arte Sovietica, La Biennale di Venezia, 1977, p.221 listed

Evgeny Rukhin, despite his tragically short life, left an indelible mark on the landscape of Soviet non-conformist art. His unique artistic language seamlessly blended elements of ancient Russian art, particularly iconography, with the avantgarde movements of the early 20th century. This synthesis resulted in a body of work that was both deeply rooted in Russian cultural heritage and boldly innovative.

Rukhin’s lack of formal artistic education, far from being a hindrance, became a source of creative freedom. Unbound by conventional rules, he transformed traditional painting techniques into an original visual language characterized by a distinctive colour palette and an exceptional emphasis on the painted surface.

Taking inspiration from Frans Hals (1582 – 1666), Rukhin “purified” his palette, limiting himself to white, yellow, and red. This deliberate restriction, combined with his expressive painting style, imbued his works with a vibrant, pulsating quality that made his artistic language instantly recognizable and unique. Collage was a significant feature of Rukhin’s work. He often incorporated old objects into his compositions, giving them new life. This technique transformed his paintings into philosophical reflections on memory and the passage of time, making them eloquent witnesses to fleeting moments. Rukhin’s technical approach was as innovative as his artistic vision. He experimented with various materials and methods to achieve maximum expressive power. For instance, he used formoplast, a jellylike yellowish substance, to create relief surfaces on canvas. This technique allowed him to create flexible forms that could be altered to suit different compositions and gave his paintings the appearance of having a “history” or “past.”

The colour scheme in Rukhin’s works often embodies the idea of decay. Beige, burgundy, and dark brown tones emphasize a sense of abandonment and aging. Through his art, Rukhin seemed to attempt to halt the all-destroying effect of time while simultaneously reminding viewers of the inevitability of this process. His works became a bridge connecting Russia’s past with its present.

Lunar serpent

signed in Cyrillic, dated ‘1972’ and titled (verso) oil on canvas

50x100 cm

Exhibited

Venice, La nuova arte sovietica. Una prospettiva non ufficiale a cura di Enrico Crispolti e Gabriella Moncada (Il Dissenso culturale [the Dissident Biennial]), 15 October - 17 November 1977, N2 (according to label on verso)

As a core member of the Lianozovo group, Vechtomov participated in all major exhibitions of non-conformist artists, helping to shape the underground art scene in the face of official restrictions.

The trajectory of Vechtomov’s artistic journey is intrinsically linked to his experiences during World War II. The war’s profound impact on his psyche became the crucible from which his unique artistic voice emerged. In the aftermath of the conflict, Vechtomov began experimenting with abstract painting, creating spontaneous, emotive works on small cardboard sheets. However, it was in the 1960s that his signature style crystallized – a surrealistic, expressive manner that served as a visual reminiscence of his traumatic wartime experiences.

Vechtomov’s artistic language is immediately recognizable. His palette, dominated by stark contrasts of orange-black or red-black, evokes both the vibrancy of life and the shadows of mortality. The lacquered texture of his paintings and the velvety quality of his watercolours add a tactile dimension to his work, inviting viewers to engage not just visually but almost physically with his cosmic visions.

The cosmic theme became a defining feature of Vechtomov’s oeuvre. His paintings are intense, fantastical creations suffused with an inner luminescence and populated by isomorphic substances. These works reflect Vechtomov’s attempt, as an artist, to touch the mysteries of the universe. His goal

was to capture and express the fundamental patterns of existence through novel forms, thereby opening a window into a new, unknown world of cosmism. Vechtomov’s approach to surrealism diverges significantly from the psychological automatism and hallucinogenic visions of Magritte or Dali. Despite the apparent tragedy in his work, there’s an underlying current of anticipation – a sense of foretelling new forms of life and existence. At the same time, his colour choices and the biomorphic substances that populate his canvases serve as poignant reminders of the horrors of war that he knew all too well.

“Lunar serpent,” one of Vechtomov’s notable works, exemplifies his artistic philosophy. In this piece, a giant serpent is portrayed as a biomorphic substance. The tangible surface of the work draws the viewer in, creating an almost hypnotic effect. The gradual transition from dark tones to vibrant orange in the middle of the canvas evokes the “fire” of a sunset, reflecting Vechtomov’s fascination with twilight – a magical threshold between light and darkness that he saw as a moment of transformation and wonder.

Vechtomov’s worldview, as reflected in his art, embraces the vastness and diversity of the universe while simultaneously perceiving it as a unified whole. His work transcends the human-centric perspective, inviting viewers to contemplate existence on a cosmic scale. Through his unique visual language, Vechtomov not only processed his own traumatic experiences but also opened new vistas of imagination, cementing his place as a visionary in the pantheon of Soviet non-conformist artists.

Royal family

signed in Cyrillic and dated ‘1972’ (verso) oil on canvas

46 x 60 cm

Alexander Kharitonov gained recognition for his pursuit of spiritual motifs, earning him a place among the movement’s ‘religious mystics. His mature pieces from the 1970s and 1980s reveal a profound mysticism deeply rooted in Byzantine art, ancient Russian iconography, and Orthodox Christian painting traditions. Kharitonov’s artistic language, particularly evident in his small-format works, can be seen as a contemplative reinterpretation of Christian iconography. These intricate pieces, filled with miniature depictions of churches, angels, cherubim, and saints, became new “icons” of non-conformism in the Soviet era. Their delicate execution and spiritual content stood in stark contrast to the officially sanctioned art of the time.

It’s crucial to understand the context in which Kharitonov was working. Christian themes were heavily censored in the Soviet Union, unwelcome in official exhibitions, and strictly limited by the authorities. Despite these constraints, a group of artists, including Lev Kropivnitsky, Otari Kandaurov, and Boris Steinberg, worked in a modernist style with mystical inclinations. However, Kharitonov distinguished himself within this group through his unique artistic execution.

A prime example of Kharitonov’s distinctive style is his painting “The Royal Family.” This work, executed in the impasto technique, draws inspiration not from French pointillism, but rather from ancient Russian beadwork embroidery, including that found on icon covers. The fine, granular surface covering the canvas is reminiscent of intricate work with precious stones, creating a texture that is both visually and tactilely engaging.

The miniature format in which the figures of the stylite and angels are rendered, as well as the abundance of details, are clearly influenced by ancient Russian Orthodox miniatures. This attention to minute detail invites close inspection and contemplation, drawing the viewer into the spiritual world Kharitonov creates.

One of the most striking features of “The Royal Family” is its treatment of the background. The beaded sky shimmers with pearlescent hues, creating a serene, atmospheric colour background. This technique imbues the painting with a sense of deep light and inner resonance, as if the entire work is suffused with spiritual energy.

In Kharitonov’s composition, the landscape takes precedence, setting the mood through which the images of churches, angels, and the royal family emerge. This approach aligns Kharitonov with the Symbolists of the early 20th century, as the entire composition is subordinated to creating a sense of mystery and spiritual depth.

Alexander Kharitonov’s contribution to Soviet nonconformist art lies not only in his technical skill and aesthetic innovations but also in his courage to explore spiritual themes in a hostile ideological environment. His work stands as a testament to the enduring power of art to express profound spiritual truths, even in the face of political and cultural opposition.

Disposition from the Cross signed, titled in Cyrillic and dated ’63-71’ (verso) oil on canvas

121 x 86 cm

Exhibited Venice, La nuova arte sovietica. Una prospettiva non ufficiale a cura di Enrico Crispolti e Gabriella Moncada (Il Dissenso culturale [the Dissident Biennial]), 15 October - 17 November 1977 (according to label on verso)

Literature

Exhibition catalogue La Nuova Arte Sovietica, La Biennale di Venezia, 1977, p.231 listed

Otari Kandaurov belongs to the circle of unofficial artists who successfully worked in magazine and book graphics. His oeuvre includes visual interpretations of works by renowned Russian authors such as Saltykov-Shchedrin, Tsvetaeva, and Akhmatova. Unlike many of his contemporaries who were drawn to conceptualism, Kandaurov charted his own course, focusing on religious motifs in his art. He considers himself a mystic and esotericist, drawing inspiration from early 20thcentury Russian cultural traditions that emphasized spiritual and mystical themes.

Rather than aligning himself with avant-garde artists who explored metaphysical and mystical concepts, Kandaurov sees his work as a continuation of Silver Age artistry, following in the footsteps of Nicholas Roerich and Mikhail Nesterov. His artistic journey towards the concept of “Holy Russia” began in the late 1960s and early 1970s, coinciding with a broader societal shift in the late Soviet era that saw increased interest in national history and, by extension, religious themes through a historical lens.

While some artists of this period focused on depicting churchdotted landscapes or scenes from ancient Russian cities, Kandaurov took a different approach. Along with artists like Ilya Glazunov, he delved into meta-historical visions inspired by Daniil Andreyev’s underground literary sensation, “Rose of the World”. This approach set him apart from those who chose more conventional representations of Russia’s religious heritage.

In Kandaurov’s “The Deposition from the Cross” traditional subject is rendered with elongated and disproportionate figures, reminiscent of medieval art. The artist follows the iconography and composition of the Deposition from the Cross quite accurately but introduces details and stylization that leave no doubt about the contemporary nature of the image. This primarily relates to the female faces, which have a modern resonance. Also, the traditional red colour for these compositions is absent; the women’s chitons are brown, which enhances the tragic nature of the composition.

Kandaurov’s art represents a fascinating synthesis of traditional religious iconography and modern artistic sensibilities. His work reflects a deep engagement with Russian spiritual traditions while simultaneously speaking to contemporary audiences.

Untitled, 1978 oil on board

80 x 120 cm

OTARI KANDAUROV (BORN 1937)

Dante

signed with monogram (lower right) inscribed ‘e quindi uscimmo a riveder le stelle’; further signed, titled in Cyrillic and dated ’68-71’ (verso) oil on canvas

60 x 100 cm

Exhibited

Venice, La nuova arte sovietica. Una prospettiva non ufficiale a cura di Enrico Crispolti e Gabriella Moncada (Il Dissenso culturale [the Dissident Biennial]), 15 October17 November 1977 (according to label on verso)

Literature

Exhibition catalogue La Nuova Arte Sovietica, La Biennale di Venezia, 1977 , p.231 listed

Fiery Ascension

signed in Cyrillic and titled (lower right) oil on canvas

49 x 65 cm

Exhibited

Venice, La nuova arte sovietica. Una prospettiva non ufficiale a cura di Enrico Crispolti e Gabriella Moncada (Il Dissenso culturale [the Dissident Biennial]), 15 October - 17 November 1977, N2 (according to label on verso)

Literature

Exhibition catalogue La Nuova Arte Sovietica, La Biennale di Venezia, 1977, p.216 listed

Among the diverse voices of Soviet non-conformist art, Vyacheslav Kalinin’s phantasmagorical and distinctive style stands out as one of the most recognizable. While his artistic approach was undoubtedly unique, Kalinin’s work embodied the core principles of non-conformist artists - a deliberate attempt to transcend the ordinary by reimagining reality through the prism of painting. Unlike some of his contemporaries in the unofficial art scene, such as Nemukhin, who engaged in an “endless dialogue” with Malevich, or Weisberg, whose creative principles were shaped by Giorgio Morandi’s metaphysics, Kalinin was less influenced by the avant-garde movements of the early 20th century. Instead, his artistic language drew from a whirlwind of elements, blending aspects of cubism with Filonovesque phantasmagoria. His work was also deeply inspired by Old Masters, particularly Bruegel the Younger and Hieronymus Bosch, creating a unique synthesis of historical and contemporary influences.

Kalinin himself described his artistic direction thus: “I wanted to capture the transience and theatricality of our life. I didn’t concern myself with style or fashionable trends in painting. Everything arose spontaneously; what I had once seen was refracted through imagination.” (V.Kalinin, (1991). MoscowZamoskvorechye. Retrospective. 1962-1990, Moscow. p. 19.) This statement reveals Kalinin’s commitment to spontaneity and his desire to reflect life’s ephemeral and theatrical nature in his art.

The theatrical quality, sarcasm, and grotesque elements in Kalinin’s style can be aptly described as “carnivalism.” The leitmotif of any carnival is abundance and utopianism, characteristics that permeate many of the artist’s paintings. Through this carnivalesque approach, Kalinin rejected conventional norms and asserted new perspectives on society. In his canvases, reality is refracted through a lens of mysticism,

becoming a mosaic of diverse images. Among these, one can often discern the artist himself or his friends, adding a personal dimension to his phantasmagorical scenes.

Kalinin’s work stands as a testament to the power of imagination in challenging societal norms. By creating a world where the boundaries between reality and fantasy blur, he invited viewers to question their perceptions and reconsider the nature of existence. His carnivalesque style, with its abundance of imagery and utopian undertones, served not just as an artistic expression but as a form of social commentary.

In the context of Soviet non-conformist art, Kalinin’s approach was particularly potent. While the official art world promoted socialist realism, Kalinin’s phantasmagorical scenes offered a stark contrast, presenting a world where the impossible became possible, and the ordinary transformed into the extraordinary. His work thus became a form of resistance, not through overt political statements, but through the sheer power of unbridled creativity.

“Fiery Ascension,” inspired by the iconography of ancient Russian icons depicting the ascension of Elijah to heaven, is a prime example of Kalinin’s approach to religious themes. According to the biblical text, a chariot of fire drawn by horses of fire appeared for Elijah. In Kalinin’s painting, the central focus is a single pair on the chariot, ascending to the sky.

The painting exudes extraordinary tension. The gloomy background consists of dark blue, deformed, and chaotically arranged architectural elements. Against this chaotic gloom, a vibrant scarlet orb blazes forth, creating a stark and arresting contrast. Despite the numerous details in the painting, they are not disjointed but rather come together like notes in a symphony. This harmony within chaos speaks to Kalinin’s skill in composition and his ability to imbue even tumultuous scenes with a sense of unity and purpose.

Kalinin’s “Fiery Ascension” represents a significant example of how religious themes persisted in Soviet art despite official disapproval. By drawing on traditional iconography and infusing it with modern artistic techniques and sensibilities, Kalinin created a work that bridges past and present, sacred and profane.

Abadonna, 1973

signed with monogram (lower right); titled ‘Abadonna’ (verso) oil on canvas

90 x 75 cm

Exhibited

Venice, La nuova arte sovietica. Una prospettiva non ufficiale a cura di Enrico Crispolti e Gabriella Moncada (Il Dissenso culturale [the Dissident Biennial]), 15 October - 17 November 1977, N2 (according to label on verso)

Literature

Exhibition catalogue La Nuova Arte Sovietica, La Biennale di Venezia, 1977, p.216 listed as Sogno.

Boris Sveshnikov, a master of subtle and virtuosic artistry, created a unique visual language that blended elements of Surrealism, Conceptualism, and Realism. His work, while chronologically belonging to the nonconformist era, spiritually aligns more closely with the Symbolist artists of the Silver Age. Sveshnikov’s art, perpetually suffused with a tinge of tragedy and anguish, was profoundly influenced by his harrowing eight-year ordeal in the Gulag.

Among Sveshnikov’s most notable works is his 1976 painting “Abadonna,” a piece that exemplifies the artist’s ability to meld personal experience with mythical and literary symbolism. This painting serves as a powerful intersection between Sveshnikov’s unique artistic vision and the complex, multifaceted figure of Abadonna from religious and literary traditions.

Abadonna, originally a biblical figure representing destruction and the abyss, evolved through literary interpretations to become a more nuanced character. In Mikhail Bulgakov’s “The Master and Margarita,” Abadonna appears as a demon of war and destruction, yet with a sense of detachment

and melancholy. This literary depiction likely influenced Sveshnikov’s interpretation, providing a rich symbolic backdrop for the artist to explore themes of destruction, suffering, and the human condition.

In Sveshnikov’s “Abadonna,” a ghostly figure hovers over a surrealistic, barren landscape. It embodies the ethereal and elusive nature of Abadonna. The desolate landscape below with a cemetery reflects the demon’s association with destruction and the void.

The painting’s colour palette, typical of Sveshnikov’s style, is dominated by muted blues, pale blues, and greys. This choice of colours enhances the atmosphere of melancholy and uncertainty that permeates the work. The light in the painting plays a crucial role, appearing to emanate from within the figure of Abadonna, emphasizing its otherworldly nature.

Sveshnikov’s interpretation of Abadonna goes beyond a mere illustration of a literary or mythical figure. Instead, it becomes a deeply personal expression of the artist’s own experiences and inner turmoil. The isolation and desolation depicted in the painting can be seen as reflections of Sveshnikov’s time in the Gulag, while the ethereal, hard-to-grasp nature of Abadonna might symbolize the elusive nature of freedom or redemption.

The painting is a great example of Sveshnikov’s masterful technique, his ability to create complex, multilayered images that invite deep contemplation. “Abadonna” is powerful fusion of personal trauma, literary allusion, and mythical symbolism. It encapsulates the artist’s ability to transform his harrowing experiences and inner turbulence into visually striking and emotionally resonant art.

Still life

signed with initial and dated ‘73’ (upper left) oil on masonite

42 x 33 cm

Dmitry Krasnopevtsev was one of the representatives of metaphysical painting in the Soviet Union. His artistic vision resonates with the ideas of Italian artists who pioneered this movement, notably Giorgio Morandi and Giorgio de Chirico. Like Morandi, Krasnopevtsev employed still life as the primary instrument for his philosophical reflections.

Throughout his numerous works, Krasnopevtsev consistently sought to explore the essence of ontological categories, particularly the problems of time, the transient nature of existence, the inherent essence of objects, and human memory. His approach to still life painting was unique and deeply philosophical.

Krasnopevtsev’s still lives were composed of diverse objects, often those that had lost their original purpose or “usefulness”: shards, scrolls, keys, shells, damaged books, and similar items. By placing these objects in an unnatural environment, the artist elevated them beyond their mundane forms. This approach affirmed his belief that every object possesses its own beauty, and that the “usefulness” of an item is primarily determined by our affection for it.

The artist’s distinctive use of colour played a crucial role in unifying these disparate objects. Krasnopevtsev employed what he termed “antique colour,” a combination of greyish and ochre tones. In his view, this “colour of past time” created a microcosm within

each still life. By eschewing vibrant colours, chiaroscuro, textural details, and surrounding space, Krasnopevtsev created timeless still lives, each serving as a metaphysical microcosm of the artist’s world.

Present still life, painted in 1973, represents Krasnopevtsev at the height of his artistic powers. This period marked the full maturation of his style, characterized by its unique depth and individuality. The composition brings together seemingly incongruous objects - a bottle, a twig, and a folded piece of paper. However, these items are not randomly chosen; they represent fragments of human memory and symbols of the world’s transience. In Krasnopevtsev’s work, objects from a once-tangible reality are transported into a world of irrationality and metaphysics.The colour palette of this still life is muted, almost monochromatic, with a smooth surface texture. The composition is set in an empty space, devoid of any indication of time or place. Dynamism and emotion are entirely absent, creating a sense of emptiness and frozen time.

This approach to still life painting sets Krasnopevtsev apart in the context of Soviet art. While official art often emphasized dynamic scenes of Soviet life and progress, Krasnopevtsev turned inward, exploring philosophical questions through seemingly simple arrangements of objects. His work represents a form of quiet resistance against the prescribed norms of Socialist Realism.

Runes of the God Odin signed in Cyrillic, titled and dated ‘73’, variously inscribed in Cyrillic (verso) oil and collage on canvas

100 x 97 cm

Landscape of the walls of an ancient church

signed in Cyrillic, titled and dated ‘72’ (verso) collage on canvas

80 x 62 cm

Exhibited

Venice, La nuova arte sovietica. Una prospettiva non ufficiale a cura di Enrico Crispolti e Gabriella Moncada (Il Dissenso culturale [the Dissident Biennial]), 15 October - 17 November 1977, N2 (according to label on verso)

Literature

Exhibition catalogue La Nuova Arte Sovietica, La Biennale di Venezia, 1977, listed as ‘Relique’ p.220

Dmitry Plavinsky, Rizzoli International Publications, Inc., New York, 2000, illustrated p. 30.

Dmitry Plavinsky, a singular artist among the Moscow nonconformists, perpetually gravitated towards “cosmic themes” - history and nature, creation and destruction, humanity and chaos. Plavinsky himself coined the direction his art took as “structural symbolism,” considering its cardinal trait the Russian worldview. He believed that a work of art springs from the overlaying, collision, and dislodging of symbols, configuring itself as a system of ciphers and hieroglyphs, veiling the artist’s ego and not always readily deciphered. Alexander Yakimovich, in his essay ‘Dmitry Plavinsky’s Myths on Culture and Nature,’ described the artist’s oeuvre most accurately: “Plavinsky immersed himself in Old Slavonic, Oriental, and Medieval Christian symbols, inscriptions, tools, and other relics of extinct civilizations, incorporating them into “archaeological” fantasies. He built up an imaginary museum of the cultural genealogy of East and West” (Dmitry Plavinsky, Rizzoli International Publications, Inc., New York, 2000, p.9).

Over time, Plavinsky’s opus grew ever more elaborate with the inclusion of an abundance of technically complex textures embedded within painterly bodies: sundry articles, from foliage and dried blossoms to fish bones and crucifixes to antique decorative fittings (which remains uncertain whether they are genuine or moulded from plaster and tempera media). His pieces developed thematically too, with the inclusion of the timeless questions of life and death, generating a synthesis of past glory and beauty. As the artist himself expressed, “Art is a fragile, sick bloom sprouting from the vestiges of titanic human cultures long vanished. I can

relay the lethally mesmeric draw this flower exacts, discern it amidst a sea of kin, yet penetrating its essence lies beyond my power. It is a sacrosanct arcanum - to touch it brings calamity upon the creator.”

The present painting presents a rare and peerless example of Plavinsky’s early phase. The artist’s masterful combination of oil, tempera, and gypsum masses allows him to overcome the limitations of a two-dimensional canvas, venturing into the realm of three-dimensional relief. This technical complexity is mirrored in the piece’s rich symbolic structure, inviting viewers to explore multiple layers of meaning and interpretation. Plavinsky’s “dark” painting technique imbues the work with a sense of antiquity, as if the piece itself has aged over centuries. This effect is further enhanced by the gypsummoulded icons that peek through the impasto surface, creating a fascinating interplay between different textures and depths. These elements not only add visual interest but also evoke the passage of time and the endurance of spiritual artifacts.

Symbolism plays a crucial role in this composition. The hand, likely representing the hand of God, serves as a powerful reminder of divine presence and intervention. In a striking juxtaposition, Plavinsky has affixed a snail to the surface of the work. This small creature, seemingly out of place in a religious context, symbolizes the intricate connection between nature and human-made objects, bridging the gap between the earthly and the divine.

Its impasto surface is vibrantly tangible, while textural minutiae like the circular perforations and earthen tonality remain archetypal of the Plavinsky oeuvre. At its core, the subject is metaphorical. By fusing manmade artifacts like icons with lifeless nature, he partakes in the Western vanitas. Plavinsky’s “narrative” dwells in perpetuity; moods of arrested time and melancholy reign, the symbolic import assuming primacy. For him, any design or form wrought by Nature or human hands constitutes but shards of a unitary symbol, essential instruments to sound the cosmos. In this light, the painting aligns with Plavinsky’s overarching philosophy, operating itself as an emblem-symbol. Plavinsky used viscous oil paints, laying his pigments in stratified films. His complex, weighty palette favoured ochres and umbers, limning the gilded jewellery in contrasting cold silvers and whites.

Non-ironed sheet

signed in Cyrillic and dated ‘61’ (upper right); further signed, titled and dated ‘1960’ (verso) oil on canvas

71 x 115 cm

Exhibited

Venice, La nuova arte sovietica. Una prospettiva non ufficiale a cura di Enrico Crispolti e Gabriella Moncada (Il Dissenso culturale [the Dissident Biennial]), 15 October - 17 November 1977, N2 (according to label on verso)

Literature

Exhibition catalogue La Nuova Arte Sovietica, La Biennale di Venezia, 1977

Vladimir Weisberg was a prominent Russian artist known for his metaphysical works, particularly his white still lives and, to a lesser extent, his portraits. His unique artistic style became synonymous with multi-layered painting techniques and his distinctive “White on White” system, a concept he devoted over two decades to developing and perfecting.

Weisberg’s artistic journey took a significant turn in the early 1960s. This period marked the formal articulation of his artistic theory, which was unveiled through his seminal report titled “Classification of the Main Types of Coloristic Perception.” This theoretical framework was further exemplified in his painting “Dedication to Cézanne” (1962), which served as a visual manifesto of his evolving artistic philosophy.

The year 1958 heralded a new era in Weisberg’s artistic career. During this transformative period, he began to gradually move away from vibrant colours and intricate compositions. This shift represented more than just a change in style; it signified a fundamental reimagining of his artistic worldview. Weisberg started to pursue different artistic goals, focusing on the subtle interplay of light, form, and space.

By the late 1970s, Weisberg had firmly established himself in the still life genre. His compositions during this period were characterized by their consistency and simplicity. Typically, they

featured a carefully curated selection of objects - plaster heads, geometric shapes, and reproductions of ancient sculptures - arranged on a pedestal. According to the artist himself, the essence of these works lay in exploring the life of objects in space, their interactions with one another, and the interplay between depth and what he termed “spatial structures.”

The painting “Non-ironed Sheet” from 1961 is particularly noteworthy as it belongs to Weisberg’s transitional period, making it an exceptionally rare piece. In this work, he demonstrates his mastery of planar relationships. The composition juxtaposes the white expanse of the sheet against the black rectangle of the table, reminiscent of Suprematist compositions. The objects in the painting form a rhythmic group that seems to vibrate within the empty space, creating a sense of dynamic tension.

Weisberg’s technique in this painting is particularly noteworthy. He employed mixtures of chromatic colours with white, allowing him to achieve incredibly subtle gradations of colour. This meticulous approach to colour creates an effect where the viewer’s eye struggles to identify familiar colour. The thin application of paint results in a watercolour-like quality, with delicate tonal transitions that blur the line between realism and abstraction.

Weisberg’s work from the 1960s is characterized by its balance between abstraction and reality. Through his arrangements of simple, everyday objects in his still lives, Weisberg invites viewers to witness a kind of artistic alchemy. Forms seem to dissolve before one’s eyes, and the viewer finds themselves transported to the very heart of the artist’s unique creative universe.

Untitled

signed with Cyrillic initials and dated ‘69’ (lower right) oil on canvas

80x100 cm

Abstract art, alongside religious themes, was one of the most striking manifestations of artistic independence among unofficial artists in the Soviet Union. Abstraction had been banished from Soviet art in the 1930s and was prohibited from public display for several decades. The authorities saw it as the most concentrated expression of an ideology alien to Soviet society.

Despite similarities and sometimes direct references to abstract compositions, Eduard Steinberg was not a blind imitator of the avant-garde. His art, in his own words, is a “decoding of another perspective of Kazimir Malevich”. The geometry in his works doesn’t call for “destruction”, provocation, or absolute freedom so characteristic of 1920s art. Rather, it’s a kind of reflection, a discovery of the spiritual through creativity. His paintings are always symbolic, serving as a unique philosophical diary of the master. The foundation of his work is the contemplation of both external and internal beauty.

In his artistic development, Steinberg went through several stages: from realistic depiction to organic forms, culminating in the triumph of geometric shapes. The main “characters” in Steinberg’s abstract compositions are circles, quadrilaterals, and triangles. He often depicts geometric figures partially, which enhances the spatial depth of the composition.

In the present work, Steinberg’s abstraction is airy, and mood driven. He divided the composition into two parts chromatically and filled it with objects, some recognizable – like a seashell and a needle – while others appear as simple geometric forms. Although the artist divides the work into two areas, he uses various shades of the same colour. The palette is delicate –subtle transitions of luminous beige, white, and grey tones create a gentle atmosphere.

Evgeny Shiffers wrote about Steinberg’s special interaction with the canvas: “Even in the analysis of a single canvas, with calm and sufficiently long... rather than fleeting observation, the canvas recedes, and light emerges with symbols floating in it: ‘sphere’, ‘cube’, ‘pyramid’, ‘horizontal’, ‘bird’, ‘cross’, ‘vertical’.” (Barabanov E. Sky and Earth of One Painting. Astonished Space. Reflections on the Work of Eduard Steinberg: Collection of Articles and Essays. Compiled by G. Manevich, Moscow, 2019, p. 126.)

Steinberg’s pure canvas, divested of superfluity, bears the hallmark of eternity - here, the iconographic image, spiritual revelation, and the philosophy of the cosmos coalesce into a singular vision.

Untitled

signed in Cyrillic and dated ‘62’ (lower left); further signed and dated (verso) pastel on board

29.8 x 41.5 cm

A group of three works coloured pencils on paper, variously signed and dated

Ilya Kabakov’s art brought a new analytical component to art history, which became the foundation of his creative method. By examining the life of Soviet society, its habits and environment, including the myths surrounding it, Kabakov constructed a new aesthetic of conceptual art that exposed all the problems of Soviet society. At the same time, his works are also an expression of the artist’s personal experience, a kind of confession about his feelings and fears. “The creation of a painting, in the precise sense, becomes a ‘therapy’ for inner biological and psychological life, synchronizes with it and ‘aligns’ it, becoming the author’s very life...”¹ As one of the founders of Soviet conceptualism, Kabakov, with his albums and total installations of the 1980s, significantly influenced a whole constellation of Russian artists.

In the 1970s, Ilya Kabakov opened a new chapter in his work, associated with the creation of artistic albums narrating the life of a lone hero living in the Soviet Union: “Primakov Sitting in the Closet,” “Komarov Who Flew Away,” and “Malygin the Decorator.” His art became narrative and illustrative. Sacrificing painterly refinements, his execution became extremely simple. Using only ink, coloured pencils, and sometimes watercolour, he concentrated on the hero’s journey, which the viewer and the artist traverse together.

Artist’s unique approach to storytelling through visual art allowed him to create immersive experiences that went beyond traditional painting or sculpture. His “total installations” of the 1980s and 1990s transformed entire rooms into complex narratives, inviting viewers to step into the lives and minds of his fictional characters. These installations often incorporated found objects, text, and sound to create a multi-sensory experience that blurred the lines between art and reality.

The artist’s work also serves as a powerful commentary on the human condition, particularly in the context of Soviet life. Through his characters and their stories, Kabakov explores themes of hope, despair, isolation, and the search for meaning in a restrictive society. His art resonates not only with those who lived through the Soviet era but also with a global audience, as it touches on universal human experiences and emotions.

Kabakov’s influence extends far beyond the borders of Russia. His innovative approach to conceptual art and installation has inspired artists worldwide, cementing his place as a pivotal figure in the development of contemporary art in the late 20th and early 21st centuries. Today, his works continue to be exhibited in major museums and galleries around the world, testament to their enduring relevance and power to provoke thought and emotion.

The tragic life of Ülo Sooster, Estonian by origin, had a significant impact on the formation of his unique artistic language; a language filled with “symbols,” surrealistic forms, and deep philosophical undertones. As Kabakov’s teacher, Sooster was one of the most educated and intellectual artists of his generation, well-acquainted with European artistic pursuits of the 20th century. Becoming one of the first adherents of metaphysical painting, he strongly influenced the unofficial art of Moscow in the 1960s. In his work, ordinary forms such as eggs, fish and juniper, items often reoccurring in his pieces, transformed into symbolic objects, balancing on the edge of fantasy and reality. The basis of his subjects were ideas about the creation of the world, life and death, as well as religious quests. Sooster’s personal style can be defined as metaphysical, incorporating features of European surrealists and abstract expressionists. His painting was subordinated to the search for the mystery of the universe, manifested through familiar objects.

Ülo had just received his diploma and dreamed of going to Paris – the Mecca of art – but in 1949 he was arrested and sentenced to 25 years without the right of correspondence. However, Sooster managed to leave the camp after 7 years. Being released in 1956 when the rehabilitation process began after the 20th Congress of the CPSU, at which N.S. Khrushchev made his historic report “On the Cult of Personality of Stalin.” The paradox of that time was that some of the most educated people of the Soviet Union were serving time in the camps, most of whom were innocent. In Karlag (Karaganda Corrective Labor Camp), Ülo continued to draw, depicting

portraits of prisoners and the prison environment on scraps of paper, for which he was often sent to solitary confinement. Nevertheless, the artist said that he preferred to sit in a solitary cell because “no one made noise there, no one interfered with thinking about art.”

The collection of drawings made in the Gulag conveys the tragedy of the situation: fear, despair, and pain. The burned edges of some works remind us that, “Any manifestation of free creativity in the camp was forbidden, and if drawings were found during a search, they were mercilessly destroyed. Several times Ülo managed to save his drawings by snatching them directly from the fire. They were saved by being tied in tight bundles. That’s how they were preserved, with burned edges” (Lidia Sooster, “My Sooster”).

The experience of imprisonment deeply influenced Sooster’s work, giving his pieces a special depth and emotional intensity. After his release, the artist continued to develop his unique style, combining elements of surrealism with deep symbolism and philosophical reflections. His works became a kind of bridge between Western European modernism and Soviet unofficial art, opening new horizons for a whole generation of artists.

Sooster’s influence on the development of unofficial art in the USSR is difficult to estimate. His creative approach, intellectual depth, and technical mastery inspired many young artists, including Ilya Kabakov, to search for new forms of artistic expression. Sooster became a key figure in the formation of Moscow conceptualism, and his ideas and images continue to resonate in the works of contemporary artists.

VLADIMIR YAKOVLEV (1934-1998)

White flower on yellow

signed in Cyrillic and dated ‘1973’ (lower right)

gouache on paper

(1934-1998)

White flower on brown

signed in Cyrillic and dated ‘1973’ (lower right)