BONEFISH TARPON

A publication of JOURNAL

CONSERVATION THROUGH SCIENCE • FALL 2023 BONEFISH BREAKTHROUGH FLORIDA’S WATER QUALITY JACK NICKLAUS

&

JOURNAL

Editorial Board

Dr. Aaron Adams, Monte Burke, Bill Horn, Jim McDuffie, Carl Navarre, T. Edward Nickens, Kellie Ralston

Publication Team

Publishers: Carl Navarre, Jim McDuffie

Editor: Nick Roberts

Layout and Design: Scott Morrison, Morrison Creative Company

Contributors

Michael Adno

Monte Burke

Dr. Duane De Freese

Chris Hunt

Alexandra Marvar

T. Edward Nickens

Ashleigh Sean Rolle

Chris Santella

Photography

Cover: Ian Wilson

Dr. Aaron Adams

Jenni Bennett

Dr. Ben Binder

Tyler Bowman

Gina Clementi

Parker Denton

Dan Diez

Greg Dini

Bill Foley

Pat Ford

Dom Furore

Dr. Kirk Gastrich

Justin Lewis

Cameron Luck

David Mangum

Micah Ness

Kellie Ralston

Nick Roberts

Paul Schlegel

Nick Shirghio

Natasha Viadero Cover

The recently discovered bonefish pre-spawning aggregation in the Florida Keys. Photo: Ian Wilson

Bonefish & Tarpon Journal

2937 SW 27th Avenue Suite 203 Miami, FL 33133

(786) 618-9479

Board of Directors Officers

Carl Navarre, Chairman of the Board, Islamorada, Florida

Dan Berger, Vice Chairman of the Board, Alexandria, Virginia

Jim McDuffie, President and CEO, Miami, Florida

Evan Carruthers, Treasurer, Maple Plain, Minnesota

John D. Johns, Secretary, Birmingham, Alabama

Tom Davidson, Founding Chairman Emeritus, Key Largo, Florida

Harold Brewer, Chairman Emeritus, Key Largo, Florida

Russ Fisher, Founding Vice Chairman Emeritus, Key Largo, Florida

Bill Horn, Vice Chairman Emeritus, Marathon, Florida

Jeff Harkavy, Founding Member and Circle of Honor Chair, Coral Springs, Florida

John Abplanalp

Stamford, Connecticut

Rich Andrews

Denver, Colorado

Stu Apte

Tavernier, Florida

Rodney Barreto

Coral Gables, Florida

Adolphus A. Busch IV

Ofallon, Missouri

John Davidson

Atlanta, Georgia

Ali Gentry Flota

Richmond, Virginia

Dr. Tom Frazer

Tampa, Florida

Doug Kilpatrick

Summerland, Florida

Jerry Klauer

New York, New York

Dr. Michael Larkin

St. Petersburg, Florida

Thorpe McKenzie

Chattanooga, Tennessee

Wayne Meland

Naples, Florida

Ambrose Monell

New York, New York

Sandy Moret

Islamorada, Florida

John Newman

Covington, Louisiana

Al Perkinson

New Smyrna Beach, Florida

Dr. Jennifer Rehage

Miami, Florida

Vaughn Roberts

Nassau, Bahamas

Jay Robertson

Islamorada, Florida

Diana Rudolph

Livingston, Montana

Rick Ruoff

Willow Creek, Montana

Adelaide Skoglund

Key Largo, Florida

Noah Valenstein

Tallahassee, Florida

BTT’s Mission

To conserve and restore bonefish, tarpon and permit fisheries and habitats through research, stewardship, education and advocacy.

Advisory Council

Randolph Bias, Austin, Texas

Charles Causey, Islamorada, Florida

Don Causey, Miami, Florida

Paul Dixon, East Hampton, New York

Chris Dorsey, Littleton, Colorado

Chico Fernandez, Miami, Florida

Mike Fitzgerald, Wexford, Pennsylvania

Pat Ford, Miami, Florida

Upcoming Events

12th Annual NYC Dinner & Awards Ceremony October 10, 2023

The University Club New York, NY

Christopher Jordan, McLean, Virginia

Bill Klyn, Jackson, Wyoming

Tim O’Brien, Harlingen, Texas

Clint Packo, Littleton, Colorado

Jack Payne, Gainesville, Florida

Chris Peterson, Titusville, Florida

Steve Reynolds, Memphis, Tennessee

Ken Wright, Winter Park, Florida

11th Annual Keys Dinner & Circle of Honor Inductions

May 2, 2024

Cheeca Lodge & Spa

Islamorada, FL

B O N E F I S H & T A R P O N J O U R N A L FALL 2023 1

A publication of

BONEFISH& TARPON

Bonefish & Tarpon Journal is printed on a sappi paper that is SFI® ≥20% Certified Forest Content and 10% recycled fiber.

Features

12 Bonefish Breakthrough

The discovery of a bonefish pre-spawning aggregation site in the Florida Keys is another hopeful sign of recovery. T. Edward Nickens

18 Sea Change

Four experts weigh in on water quality in Florida Bay and the Keys. Alexandra Marvar

of

30 The Sea Bear

Legendary golfer Jack Nicklaus is also a well-traveled and accomplished angler. Monte Burke

40 Unraveling the Mystery of the Florida Keys Permit Decline

Bonefish & Tarpon Trust is collaborating with the guide community to conserve the iconic permit fishery. Michael Adno

Anglers explore the flats

southern Belize. Photo: Under Armour

Anglers explore the flats

southern Belize. Photo: Under Armour

Updates & Reports Setting the Hook ......................................................................... 4 Welcome Aboard ......................................................................... 6 Tippets ........................................................................................ 8 Conservation Captain Q & A ...................................................... 24 Bahamas Mangrove Restoration Project ................................... 26 Tarpon Isotope Study ................................................................ 36 Modeling Bonefish Larval Drift in Abaco ................................... 46 2024 Artist of the Year: Roger Fowler ........................................ 52 10th Annual Keys Dinner & Circle of Honor Inductions .............. 56 Last Cast ................................................................................... 64

Setting the Hook

From the Chairman and the President

The process of change never happens in a straight line. That’s also true in the work of conservation and the applied science that guides it.

Every win we’ve recorded in the flats fishery has resulted from hard work, some of it spanning years and salted with frustration and challenge. Rarely does anything truly consequential ever come about without being first tempered through a process of trial and error.

This issue of Bonefish & Tarpon Journal features several projects moving along just such a trajectory of iteration, from the years-long search for bonefish pre-spawning aggregations (PSAs) in the Florida Keys to the continuing efforts under Project Permit to understand new aspects of a slow decline in the permit population.

Last April, BTT scientists succeeded in locating, tracking, and documenting a bonefish PSA in the Florida Keys—a first in the region and further evidence that the local population has recovered to the point that it can support large spawning events. News of the discovery, which was carried far and wide, stoked new hope for the fishery. But what these news accounts didn’t share was the backstory of iteration and perseverance. In the end, this story of discovery reads like a Hollywood script.

After searching for years, BTT’s team was drawing ever closer to their goal in the 2022-23 season. Yet, at times, the project felt a lot like a day on the flats with shots but no eats. Promising activity in December fizzled. The fish didn’t spawn in January or February. A promising series of events in March led scientists to an inshore aggregation that was tracked for three days along an offshore reef. Just when there were signs around midnight that these fish could be moving off to spawn, a large center console boat sheared telemetry equipment from BTT’s Pathfinder—and nearly sheared the researchers with it. That ended the month’s search and left the team with one last shot in April.

You can read the rest of this terrific story—and why this discovery is so important—in the excellent article penned in these pages by T. Edward Nickens.

In a similar way, our ongoing research under Project Permit illustrates the iteration of research from one question and one data point to another. Collectively, Project Permit has produced more conservation outcomes over the past decade than any other study in BTT history, from refinements to Florida’s Special Permit Zone to the seasonal no-fishing closure at Western Dry Rocks, a vital spawning site for Keys permit.

New questions arose last spring when the world’s best permit anglers and guides landed only one fish after three days in the annual March Merkin Permit Tournament. While there are many factors that can affect fishing over a three-day period, all agreed this was concerning and called for new research into possible changes in the Lower Keys permit population.

Michael Adno tells the story of how BTT scientists rolled up their sleeves along with Keys guides and framed a series of specific studies that would be conducted collaboratively and expeditiously. Sampling is underway now with the aim to process and analyze data by year’s end. The results should help us understand any changes between flats and reef populations and possibly detect

Carl Navarre, Chairman

Jim McDuffie, President

Jim McDuffie, President

changes in the food web sustaining them.

The closely related and all-encompassing topic of water quality is the focus of Alexandra Marvar’s insightful article, “Sea Change,” which sheds light on the present-day conditions in the Keys and Florida Bay. Four experts weigh in on the region’s water quality and how updated wastewater infrastructure and ongoing restoration efforts have and will continue to benefit South Florida’s natural resources, including its fisheries. BTT is also taking a leading role in habitat restoration in The Bahamas, where we have planted 55,000 mangroves with our partners and local volunteers, including bonefish guides, students, and government officials. In his article, “Taking Root,” Chris Hunt recaps the project’s recent progress as well as the launch of the Bahamas Mangrove Alliance, through which BTT and partners will scale up mangrove restoration to the national level.

In these stories of iteration, which are occasionally punctuated with episodes of frustration and challenge, one thing remains constant—your support for our mission! This issue is a testament to our remarkable progress over the year, which would not have been possible without your commitment to the cause. Together, we’re ensuring that the flats fishery is healthy and sustainable for generations to come.

BTT scientists Natasha Viadero, Parker Denton, and Dr. Ross Boucek use an underwater hydrophone to listen for tagged bonefish at the pre-spawning aggregation site. Photo: Ian Wilson

Dan Berger Elected Vice Chairman

Dan Berger has been elected Vice Chairman of the Bonefish & Tarpon Trust Board of Directors. Berger has served on the BTT board since 2017 and chairs the Policy and Government Affairs Committee.

“Dan has contributed significantly to BTT’s exponential growth and development over recent years,” said BTT President and CEO Jim McDuffie. “His impact has been felt across our organization, from successful conservation policy initiatives to matters of organizational governance. We are grateful for his leadership at the board table and across the flats fishing community.”

Berger has more than 30 years of executive management and government affairs experience. He currently serves as the President and CEO of the National Association of Federally-Insured Credit Unions (NAFCU). Berger also served as Chief of Staff in the U.S. House of Representatives and has been an effective

Make their future your Legacy.

advocate and political strategist for trade groups and corporations.

“Bonefish & Tarpon Trust is a leading conservation organization that puts a much-needed focus not only on environmental protection, but also on research and advocacy,” said Berger. “It has been a pleasure to serve as a board member for the past six years, and I’m looking forward to elevating the meaningful efforts of BTT in my new capacity and continuing our efforts in ‘Bringing Science to the Fight’.”

A well-known figure with political and financial press, Berger has been listed as one of the most influential lobbyists in Washington by The Hill newspaper every year since 2002. He is a contributor on CNBC, Fox Business, Bloomberg TV and CNN. He is also regularly quoted in national and financial news outlets such as Forbes, The Wall Street Journal, and The Washington Post

Berger earned a master’s degree in public

administration from Harvard University and a B.S. in economics from Florida State University. He is a member of The Economic Club of Washington, D.C., the U.S. Chamber of Commerce Committee of 100, and was an adjunct professor at The George Washington University in the communications department. Berger enjoys traveling the world to fish with his daughter Shelby, a BTT Youth Ambassador.

To learn more, go to BTTLegacy.org or contact BTT Planned Giving Specialist Gordon Nelson at 435-213-9986 or legacy@bonefishtarpontrust.org

Welcome Aboard

Dan Berger

Planned giving techniques can help you save taxes, benefit your family, and help ensure a healthy future for bonefish, tarpon, permit, and their habitat.

BTT Welcomes Three New Board Members

Ali Gentry Flota, Vaughn Roberts, and Diana Rudolph have joined Bonefish & Tarpon Trust’s Board of Directors.

“We are honored to welcome Ali, Vaughn, and Diana to the board,” said Jim McDuffie, BTT President and CEO. “Their knowledge, experience and commitment to the cause will advance our mission to conserve species and habitats that support the flats fishery.”

Flota is President and CEO of El Pescador Lodge on Ambergris Caye in Belize, which she has owned for more than 25 years. She has been active in local conservation efforts, including working closely with Green Reef, an NGO on Ambergris Caye, and with BTT on bonefish and tarpon tagging, educational programs, and policy outreach to improve fisheries management. Flota was an integral part of the team that worked with the government of Belize to enact the catch-and-release legislation that made Belize the first country in the world to protect bonefish, tarpon and permit. Under her leadership, El Pescador was also the first hotel in Belize to institute a carbon emissions program to offset guests’ flight footprint.

“I am honored to work alongside BTT as we pursue our mission to conserve and restore flats fisheries,” said Flota.

As Senior Vice President for Government Affairs & Special Projects at Atlantis

Paradise Island, Roberts joins the BTT board with more than 25 years of corporate leadership experience in the areas of government affairs, finance, and management of multi-faceted projects.

“Atlantis and flats fishing are two cornerstones of the Bahamian tourism product and we are excited to be allies in efforts to preserve and protect our natural wonders,” said Roberts. “I am honored to join the Bonefish & Tarpon Trust board and to support the organization’s important mission to conserve marine habitats here in The Bahamas and throughout the Caribbean. The importance of BTT’s work to identify, research and conserve shallow water habitats essential to our fisheries and economy cannot be overstated. Atlantis is proud to support the current mangrove restoration project as well as the remarkable past research that focused on bonefish spawning.”

Prior to Atlantis, Roberts served as Senior Vice President of Finance, Administration and Capital Projects at the Ocean Reef Club in North Key Largo, Florida. Earlier in his career, he held financial management, investment banking, consulting, and accounting positions with More Development Company, Baha Mar Resort, KPMG, Lehman Brothers, Bank One and Dresdner Kleinwort.

Roberts serves as chairman of the board of Friends of the Arts in The Bahamas, Inc. and on the boards of the National Art Gallery of The Bahamas, the Bahamas Hotel Industry Management Pension Fund, the Charitable Arts Foundation, and the Downtown Nassau Partnership.

Rudolph is an accomplished angler who dominated the women’s fly-fishing tournaments in the Florida Keys for many years, winning four Women’s World Invitational Tarpon Fly Tournaments between 2003 and 2009 and becoming the first woman to win the annual Don Hawley Invitational Tarpon Tournament, notching her victory against an all-male field in 2004. During this time, she virtually rewrote the Women’s IGFA world record book on bonefish, permit and tarpon.

“Having a marine biology background and a passion for fly-fishing, I am thrilled to be working with such a conservationfocused organization,” said Rudolph.

In 2007, Rudolph was featured in the American Museum of Fly Fishing’s awardwinning short film, “Why Fly Fishing,” and was selected in 2009 to co-host the Sportsman Channel’s series, Breaking the Surface. She is on the advisory staff for Sage rods and Rio Products and previously served on the Board of Directors for the Federation of Fly Fishers.

B O N E F I S H & T A R P O N J O U R N A L FALL 2023 7

Ali Gentry Flota Vaughn Roberts

Diana Rudolph

Tippets Short Takes on Important Topics

BTT SUCCESSFULLY ADVOCATES FOR INNOVATIVE WASTEWATER TECHNOLOGY GRANT PROGRAM

Recent BTT studies of bonefish in the Florida Keys and of redfish across Florida estuaries found high numbers and concentrations of pharmaceutical contaminants in these species to the point that they can impact fish behavior. Pharmaceutical contaminants are a world-wide problem, with the majority of these chemicals believed to enter the natural system through septic leaching and wastewater effluent. While there are currently no regulatory water quality standards for these types of chemicals, treatment options are available to remove them from wastewater systems. Earlier this year, BTT advocated for the creation of an innovative wastewater technology grant program within the Florida Department of Environmental Protection to begin addressing this issue. The Florida Legislature and Governor DeSantis responded with $2.5 million in the state’s budget to establish the program and put Florida on the cutting edge of water quality advancement.

BTT PARTNERS WITH COPAL TREE LODGE ON EDUCATIONAL OUTREACH IN BELIZE

With the support of Copal Tree Lodge in Punta Gorda, Belize, BTT has created education materials to highlight the conservation needs for a sustainable flats fishery in Belize. The materials focus on the importance of habitats, the cultural and economic value of the flats fishery to Belize and its coastal communities, the need for public and government support for habitat conservation, and best handling practices for guides and anglers. The materials are currently being distributed in Southern Belize schools, with other regions of Belize to follow. The educational outreach will also be featured on Belizean radio and TV programs. This is the first step of many to increase knowledge of the importance of the flats fishery and habitat conservation to the future of Belize. To download the education materials, visit: BTT.org/belize-education.

PROGRESS MADE IN EVERGLADES RESTORATION

Everglades restoration continues to move forward with unprecedented momentum and funding of projects to increase the southerly flow of clean, fresh water. Bonefish & Tarpon Trust is actively engaged in that process, from advocating for specific projects and state and federal funding to vocalizing the importance of Everglades restoration to our flats fisheries. BTT has made many visits to Washington, D.C., participated in project groundbreakings and ribbon cuttings, and attended South Florida Ecosystem Restoration Task Force meetings to ensure restoration continues to move forward. With Florida committing almost $600 million in the state’s 2023-2024 budget and the current Federal commitment at over $450 million, the future currently looks bright for achieving the fisheries and other ecological benefits we need from Everglades restoration.

TTBRide in style with the BTT Florida license plate.

NEW BTT LICENSE PLATE NOW AVAILABLE

Show your support for Bonefish & Tarpon Trust on the road with the new BTT Florida license plate, featuring the art of Derek DeYoung. If you hold a valid Florida Driver’s License or Official Florida Identification Card, you are now eligible to purchase BTT plates for your car, truck, trailer and RV! $25 from every plate sold will benefit BTT’s mission to conserve bonefish, tarpon, and permit, and the habitats that support the flats fishery. Visit your local tag agency to order yours today.

8 B O N E F I S H & T A R P O N J O U R N A L FALL 2023

FWC Executive Director Roger Young, BTT Vice President Kellie Ralston, DEP Secretary Shawn Hamilton, and Biscayne Bay Chief Irela Bague at the Taylor Slough ribbon cutting.

BTT Belize-Mexico Program Manager Dr. Addiel Perez, Florence Ramclam, Principal of Punta Gorda Methodist School, fishing guide Dennis Garbutt, and Lysandra Chan, BTT Belize-Mexico Program Technical Assistant.

BAHAMAS MANGROVE ALLIANCE EXPANDS

BTT, Perry Institute for Marine Science (PIMS) and Waterkeepers Bahamas (WKB), known collectively as the Bahamas Mangrove Alliance (BMA), signed an MOU with other organizations on World Mangrove Day (July 26) to facilitate the scaling up of efforts to restore a mangrove ecosystem hard-hit by Hurricane Dorian. The agreement was memorialized in a signing ceremony hosted by the University of The Bahamas and included BTT, PIMS, WKB, Bahamas Agriculture and Marine Science Institute, Bahamas National Trust, Blue Action Lab, Friends of the Environment, and The Nature Conservancy, among others. Read more about the work of the Bahamas Mangrove Alliance on page 26.

Respondents shared that they perceived water quality and habitat availability as the greatest threat to tarpon, and that restoration efforts should be a top conservation priority. Respondents also supported regulations that prohibit harvest (such as catch-andrelease only), increased science efforts to understand Atlantic tarpon ecology for conservation solutions, and spatial management, such as pole-troll zones (where high-speed motorboat travel is prohibited).

Another concerning trend revealed by the survey is the increasing number of shark encounters that result in lost tarpon. On average, guides lost two to seven tarpon per year to sharks over the last five years. Specifically, encounter rates with sharks that resulted in lost tarpon were most likely in passes, where tarpon aggregate seasonally. This highlights the need for engagement with anglers regarding fishing ethics, as well as additional data collection needs surrounding angler-predator interactions and research on solutions to reduce the loss of tarpon to sharks. The information provided by this survey is vital in helping us better understand the threats facing tarpon and prioritize conservation efforts to safeguard the future of the tarpon fishery.

Tarpon are classified as a “Vulnerable” species by the International Union for Conservation of Nature. Photo: Pat Ford

TARPON SURVEY REVEALS TRENDS AND THREATS

A recent survey of nearly 1,000 tarpon anglers and guides conducted by BTT collaborating scientists at the University of Massachusetts Amherst revealed that the quality of the fishery has declined considerably since the 1970s. Given that Atlantic tarpon are not part of any formal stock assessment, such information is invaluable to leverage support for the development of more effective conservation and management plans for this valuable and beloved species.

BTT ADVOCATES FOR PASSAGE OF SHARKED ACT

Conservation measures taken over the past 20 years have resulted in some of the healthiest shark populations seen in several decades. A consequence of this recovery has been the rapidly increasing loss of flats fish and other species from shark depredation. Over the past decade, BTT has been at the forefront of this issue. BTT research at Boca Grande Pass helped lead to state prohibitions on break away jigs, and depredation studies at Western Dry Rocks led to a seasonal no-fishing closure that is critical to the protection of spawning permit. A new project now underway in the Florida Keys will study shark interactions by location, season and fishing method. The results will help inform future management decisions, including ways to reduce shark and angler interactions, and limit impacts to our valuable fishery.

BTT is simultaneously advocating for passage of the SHARKED Act, which was introduced in the US House of Representatives in June to establish a task force of fisheries managers and shark experts responsible for addressing increased shark depredation. The SHARKED Act would be the first step in building our knowledge to improve management and mitigate depredation nationally. To learn more about the SHARKED Act and read BTT’s letter of support, visit: BTT.org/sharked-act.

B O N E F I S H & T A R P O N J O U R N A L FALL 2023 9

The Bahamas Mangrove Alliance Founding Partners signed an MOU on World Mangrove Day. L-R: Dr. Craig Dahlgren, Perry Institute for Marine Science, Jim McDuffie, Bonefish & Tarpon Trust; Geoffrey Andrews, Bahamas National Trust; Rashema Ingraham, Waterkeepers Bahamas; Marcia Musgrove, The Nature Conservancy.

A hammerhead shark predates on a tarpon. Photo: Jenni Bennett

BONEFISH BREAKTHROUGH

BY T. EDWARD NICKENS

For hours, the researchers refused to take a drink of water or a bathroom break. On Bonefish & Tarpon Trust’s 23-foot Pathfinder, idling in the weak light of dawn above the offshore reef tract that parallels the Upper Florida Keys, BTT’s Florida Keys Initiative Manager Dr. Ross Boucek, BTT Research Biologist Natasha Viadero, and intern Parker Denton were glued to a sonar screen. The scan showed a glowing red blob under the boat—a school of bonefish that measured 20 feet from top to bottom. “We barely allowed ourselves to breathe,” says Boucek, recalling the intensity of the moment. The team had been following the massive school of pre-spawning bonefish for nearly 12 hours— from sunset the previous day to the yawning dawn of April 15, 2023—and exhaustion was gaining a stranglehold on the excitement of the moment. And summer was coming. This was very likely the last chance the scientists would have for at least

six months to try to solve one of the most bewitching mysteries in marine fisheries: Where do the famed bonefish of the Florida Keys spawn?

In an era in which scientists have plumbed nearly every corner of the globe, it seems oddly curious that the reproductive ecology of a fish worth millions of dollars to the economy of South Florida can seem as little-known as the dark side of the moon. Scientists do know that bonefish gather in giant pre-spawning aggregations (PSAs) as they migrate to spawning grounds. BTT researchers have recently identified seven such critical sites in the Bahamas, and one in Belize. But where the Florida Keys fish spawned was an unknown—and a critical piece of data for the conservation of the species.

Now the giant aggregation of bonefish, a species far better known for its habit of feeding in inches-deep water than

12 B O N E F I S H & T A R P O N J O U R N A L FALL 2023

meandering the ocean depths, headed for deep water yet again. Boucek winced. He’d been on this hunt for nearly two years, and now he was as close as he’d ever been to witnessing Florida bonefish spawning in the wild. He leaned on the boat throttle, and once again, followed the fish.

ON THE HUNT

In September of 2021, BTT kicked off a search that had long been a Holy Grail for flats fisheries advocates: The discovery and documentation of a spawning location of Florida Keys bonefish. In the Bahamas, three of seven PSA sites identified by BTT scientists have been protected as Bahamian national parks. But in the Florida Keys, the specific locations used by PSAs—if they exist at all—has remained a mystery.

The three-year research project—which is still ongoing—

involved extensive interviews with fishing guides, and intensive monitoring of tagged bonefish over the last two years. The work had honed in on a short list of possible PSA sites in the Keys, and the subsequent plan to intercept them looked like something that had been war-gamed at the Pentagon.

If acoustic monitoring arrays could alert researchers to the formation of an inshore bonefish aggregation, and if the scientists could catch a bonefish out of the school, and if they could surgically implant it with a continuous pinging tag, and then get to the offshore reef in time, and intercept the school with its tagged fish, and follow the bones day and night using drones and telemetry, they just might be able to identify for the first time one of the spawning locations of Florida Keys bonefish. The “ifs” piled up like seashells on a high-tide line.

Approaching December of 2022, all the assets were in place.

B O N E F I S H & T A R P O N J O U R N A L FALL 2023 13

The newly discovered bonefish pre-spawning aggregation in the Florida Keys. Photo: Ian Wilson

Based on earlier findings, the team had shifted acoustic tracking receivers from as far away as Tavernier and Key Biscayne to a 25-square-mile sweet spot off the Upper Keys. BTT’s Pathfinder was outfitted with tracking equipment, fishing rods, and an array of surveillance tags: In addition to standard 13mm bonefish tags, BTT had procured larger 16mm tags powered by a 5-year battery, Acoustic Data Storage Tags capable of recording and transmitting depth-of-dive data, and continuous pinger tags that would allow researchers to follow tagged fish offshore. Under the advice of BTT chair Carl Navarre, BTT invested in a specialized sea buoy outfitted with instrumentation that would text BTT scientists whenever a tagged bonefish passed the buoy. If the Bonefish Buoy pinged, Boucek and his team might have as little as 24 hours to be on site.

Calendars were cleared from January through April of 2023, as the researchers monitored bonefish movements, watching for bonefish to move towards suspected spawning sites. There was activity in late December, but it fizzled out. During January and February, the fish simply didn’t spawn. On March 1, the Bonefish Buoy pinged, and the team launched to intercept an inshore aggregation. Viadero and Denton caught six fish, and deployed a pinger tag in one of the bones. The team followed the fish for three days as it meandered along an offshore reef. Unfortunately, an after-midnight near-miss with a large center console boat sheared the telemetry equipment’s mount off the Pathfinder, which promptly ended that search.

The next potential spawning period in mid-March was weathered out. April loomed, typically considered the end of the bonefish spawning season.

“Thinking back about all of this, it might sound like we were running around like chickens with our heads cut off,” says Boucek. “But every time we went out, we got a little closer, and a little closer.”

In early April, the last month of the spawn, a forecast suggested slick seas and clear skies for a few days. Boucek had a good feeling. He called photographer Ian Wilson and invited him to join the chase as soon as the Bonefish Buoy sounded off. “I knew that could be a mistake,” Boucek laughs, thinking about that decision. “As soon as you line up a photographer, you can bet nothing will happen.”

But overnight on April 2nd, the Bonefish Buoy sent out a text alert. Fish were on the move. Boucek, Viadero, Parker, and Wilson shoved off at sunrise, and raced to intercept the aggregation. Within 45 minutes they had found a massive group of fish. On the

bow, Wilson remarked that they just ran over some bonefish, but when Boucek glanced overboard, the fish he saw were too large to be bones. “They must be barracuda,” he replied. He looked again. Fifty feet from the boat was a swirling wall of bonefish.

Wilson slipped over the side of the boat, and was enveloped in the school of bonefish. What had been a “pipe dream,” says Boucek, at the beginning of the year now swirled under the boat.

The team followed the PSA for most of the day. When four bonefish porpoised on the surface, Boucek grabbed a fishing rod. He instantly hooked a bonefish five miles from shore. Where there weren’t supposed to be bonefish.

But still, the actual bonefish spawn eluded the team. In midApril, a minor tropical storm parked over Miami for several days. As soon as the weather broke, the Bonefish Buoy transmitter pinged: Fish were again on the move. It was very likely the season’s last chance.

STALKING THE GHOST

In the wake of Florida’s bonefish population crash in the 1990s, many scientists believed that so many fish were lost that there was no base population left to effectively spawn. Species that synchronously reproduce in large numbers do so in part because of an evolutionary strategy called “predator swamping.” When so many individuals gather at the same place and time, it dampens the effects predators can have on an overall population. It’s a theory tied closely to why sharp-tailed grouse in the West, for example, gather in massive roosting leks. It’s why passenger pigeons nested in communal flocks that numbered in the millions.

And it’s why passenger pigeons are extinct. The flip side of

14 B O N E F I S H & T A R P O N J O U R N A L FALL 2023

Parker Denton listens for tagged bonefish with an underwater hydrophone.

Photo: Ian Wilson

Scientists sample eggs from bonefish in PSAs to determine their spawning readiness. Photo: Natasha Viadero

synchronous reproduction is that a population simply won’t attempt to breed if a population falls below a certain threshold. The last wild passenger pigeon was likely not shot. It’s just that the last passenger pigeons likely would never have bred. Twenty bonefish likely don’t go offshore to spawn. Without a large aggregation and its visual impact and swirling, raucous energy, these species simply sit out the dating game.

Which is why Boucek was so stunned by his in-your-face look at the bonefish aggregation uncovered with Wilson. When he and Wilson were overboard, free-diving with the bonefish PSA, Boucek was surrounded by more bonefish that he ever imagined was possible to see at one time. Wilson looked like a rock in a river of bonefish, rushing by a foot from his camera lens. “And the number of 8-pounders and even larger was incredible,” Boucek says. “I’m certain I’ll never see larger bonefish in my life.”

And the size of the aggregation was larger than he expected. It’s difficult to estimate how many fish a sonogram might capture. Comparing the sonagram captures of the Keys PSA to those in the Bahamas, “this one was twice as long and twice as high,” Boucek says. He estimates the school had between 2,000 to 5,000 fish. “To be honest,” he says, “just seeing that massive PSA was mission accomplished for me.”

But there was more to do, more to ask, more to learn. As midApril approached and the weather cleared, he was back on the hunt for bonefish.

When Boucek woke up on the morning of April 13, he had a text message waiting on him from the Bonefish Buoy. He rallied the team, and Boucek, Viadero, and Denton were on the water at noon. By now they had the process dialed in: Find the nearshore fish. Catch and tag. Intercept the school as it moved offshore. They followed fish for the entire afternoon and evening as the school meandered along the offshore reef tract. Boucek was stunned by its size—likely twice the size of the aggregation of a few days earlier. They were so close, but the window for the spawning season was closing quickly. The hours ticked by. “We

ran out of energy drinks at 9 p.m.,” Boucek laughs, “so then things really got terrible.”

At 1 a.m., the school rose from 100 feet down back to the surface, and bonefish porpoised in the green and red glow of the boat’s navigation lights. Then the fish dove again, and swam at full speed another two miles and stopped in 200 feet of water. They slowly drifted along the bottom as sonar signatures from large predators circled the school.

By 5:30 a.m., the team had been on high alert for nearly 18 hours, and stars on the eastern horizon began to wink out with the brightening sky. Suddenly the bonefish hit the gas pedal again. At such a depth, tracking with acoustic telemetry becomes difficult. The signals faded and rebounded, time and again. “We all just prayed that we don’t lose them,” Boucek recalls.

The fish stopped again, this time at the 400-foot drop off. On the small manual tracking screen linked to the pinging tags, the school sank deeper and deeper. Two-hundred fifty feet. Three

B O N E F I S H & T A R P O N J O U R N A L FALL 2023 15

BTT’s Dr. Ross Boucek releases a Florida Keys bonefish after surgically implanting an acoustic transmitter.

Photo: Ian Wllson

Dr. Boucek measures a tagged bonefish before releasing it. Photo: Ian Wilson

hundred. Fish known for feeding in mere inches of water were now as deep as a football field is long. The school stopped and hovered at about 350 feet deep, rose 100 feet, then went down yet again. Denton hadn’t had as much as a sip of water in hours, and was feeling the shakes. Boucek had “almost peed in my pants four times because I didn’t want to get off the boat’s steering wheel. It came down to this one moment.”

Under the boat, a school of bonefish thousands strong hovered between 350 and 400 feet deep. On the sonar, the glowing orb rose 100 feet, then dove. It rose another 100 feet. And then came an acoustic anomaly. The continuous pinging tags are inserted into the body of a female fish, next to the ovary. On the ocean surface, with the sun hugging the horizon, Boucek and his colleagues watched as a pinging tag sank below the school, and kept on sinking. It settled to the bottom of the sea at 700 feet deep. The bonefish had spawned the tag out—literally ejecting it from its body with its eggs.

Boucek and company had discovered the first spawning aggregation of bonefish ever documented in the Florida Keys. They were exultant and exhausted, high-fiving on the boat, when a mahi-mahi free jumped, clearing deep dark blue water 30 feet from the boat. “And that’s when it really set in,” Boucek says. “These Florida Keys bonefish spawn in the open ocean.”

NEXT STEPS

The discovery of an Upper Keys bonefish PSA has conservationists and future-minded anglers buzzing. “The fact that these fish went to 400 feet was astonishing to me,” says Captain Rick Ruoff, a BTT board member and guide who has fished the Florida Keys for more than 50 years. “That was a miraculous discovery. It was a spectacular effort by Ross Boucek.”

Jim McDuffie, BTT President and CEO, agrees. “This is a major discovery for the Florida Keys fishery—and one made possible by our incredible staff who spent countless hours, day and night, on the water chasing it,” he says. “It’s further evidence that the local bonefish population has recovered to a place where it can support large spawning aggregations again. And beyond the discovery and its location on a map, our research at the site will help us understand more about where and how Keys bonefish spawn.”

Now, everyone involved knows that the hard work lies ahead: Protecting the area that is so vital to future of bonefish in Florida.

The precise location of the spawning area remains a secret, and may for some time. While it is surprising that the site has remained hidden in plain sight this long, it is located in a region that’s a bit too far for most snorkeling trips, and not in an area frequently

targeted by anglers. There is traffic, but even when numbered by the hundreds, bonefish can be tough to spot. While following one school, Boucek watched a skiff run right over part of a PSA in the area. The boat’s occupants never saw the well-camouflaged fish.

Yet the danger remains. It wouldn’t take much to wipe out a significant chunk of the region’s spawning population of bonefish. A gillnetter could sweep up a thousand bonefish by accident. Unscrupulous anglers could flock to the area to target susceptible fish. It’s likely a matter of when, not if, a charter boat figures out the location. The temptation will be strong to turn such a critical aggregation into a targeted fishery.

Thankfully, there are possible templates for conservation action. The discovery and subsequent seasonal closure of the Western Dry Rocks spawning grounds fishery for permit could serve as an example of how to protect critical habitat in a way that actually enhances a fishery. But there is not yet enough known about how tied bonefish may or may not be to this particular region of the Upper Keys offshore reef tract. More study is critical. “Nothing is going to get better on its own,” Ruoff warns. “The more we know about this behavior, the better we can manage and adjust our efforts towards making a better fishery out of what we have left.”

At a time when there seems to be a flood tide of ill news for bonefish—the presence of pharmaceuticals in bonefish populations, increasing habitat loss, the ever-present question of the effects of climate change—the discovery of a primary spawning grounds is a jolt of positivity and possibility. It underscores the resilience of bonefish, and the impacts of conservation work in the past. And it bolsters an argument for continued conservation action.

“The future looks bright for Florida Keys bonefish,” says Boucek. “We have a population of bonefish that is recovering from a drastic decline that began in the 1990s. The number of 18- and 19-inch young bonefish we are seeing in places is incredible. But we have just a few years to make some big moves to keep good things happening. And first up is the need to keep this reservoir of bonefish safe and happy for a very long time.”

An award-winning author and journalist, T. Edward Nickens is editor-at-large of Field & Stream and a contributing editor for Garden & Gun and Audubon magazine.

16 B O N E F I S H & T A R P O N J O U R N A L FALL 2023

Bonefish porpoising to gulp air in preparation for spawning.

Photo: Parker Denton

Natasha Viadero prepares an acoustic receiver before deploying it to track bonefish. Photo: Ian Wilson

Expert Handling for Fish (and Travel) Call us today. 1-800-245-1950 | www.frontierstravel.com Ready to have your next trip designed by the experts? As the leader in destination fishing for over 50 years, and the only full-service agency in the industry, no one is better equipped to handle your trip from start to finish. Careful handling is about now and the future. Travel Enhanced

B O N E F I S H & T A R P O N J O U R N A L FALL 2023

Anglers fish for bonefish in the Florida Keys. Photo: Ian Wilson

SEA CHANGE: UNDERSTANDING WATER QUALITY IN FLORIDA BAY AND THE KEYS

BY ALEXANDRA MARVAR

BY ALEXANDRA MARVAR

Hundreds of years ago, the low-lying porous limestone peninsula in the southeastern-most corner of what is now the United States of America was a tropical wilderness of wetlands, rivers and lakes. Fresh water flowed from the headwaters of the Kissimmee River to the coral reefs of the Florida Keys, hydrating biodiverse marshes and mangrove forests along the way. Even before Florida became a state in 1845, visitors had already begun speculating as to how to make this region less swampy, and thus more habitable for European colonists. These conversations became plans, and these plans formed the foundation of a more-than-century-long effort to drain the Everglades.

By the 1950s, Florida’s population was growing fast, the Everglades were being developed, and flood control was imperative to progress. The state launched its Central and Southern Florida project: canals, levees, water storage infrastructure, and pumps designed to replumb the southern portion of the state. What Floridians didn’t realize then was that this reworking of water patterns was throwing a delicately balanced system into chaos, creating massive ecological and water quality problems that have taken decades, and billions

of dollars, to address. The rescue operation is still a work in progress—one stakeholders say is the single largest ecosystem restoration project on the planet.

Restoration won’t just affect Everglades National Park, according to the National Park Service’s Dr. Erik Stabenau, the Chief of Restoration Sciences at the South Florida Natural Resources Center. Restoring some of the natural balance to this system will also influence the marine environments on which some of the state’s most profitable and unique fisheries rely: Florida Bay and the Atlantic waters east of the Keys.

The project is designed to boost water quality in the Everglades and Florida Bay, Stabenau said, largely by controlling salinity. The right balance of salt and fresh water sets up the ecological conditions that allow good things—like seagrass, and mangroves, and from there, all the species that depend upon them—to grow.

“Fresh water in the dry seasons is what protects the low salinity and the mangrove fringe inside Florida Bay,” he said. “Anything we can do in the restoration program that eventually delivers water consistently through the dry season as it did historically—that will have benefits to the bay. We’re certain of

We asked four experts for an update on the region’s water quality.

B O N E F I S H & T A R P O N J O U R N A L FALL 2023

this, because when nature does its part and helps us, we see the response in the bay already.”

Two examples of this, he said, were the large freshwater pulses in the past six years brought about by hurricanes Irma and Ida—both of these events, he said, led to jumps in South Florida’s fish populations. “When you push more fresh water into the system, Florida Bay behaves better,” he said. “The number of fish goes up. You put in more fresh water, the fish grow larger, faster, earlier in their [lifecycle].”

But when it comes to water quality in Florida Bay, salinity is just the tip of the iceberg.

WHAT IS WATER QUALITY?

When we think of water quality, we might think more about pollution, rather than salt water versus fresh water, but it isn’t so cut and dry. To understand water quality, scientists need data on a few separate aspects of the water’s physical, biological, and chemical conditions.

Physical water quality encompasses factors like salinity, temperature, dissolved oxygen, turbidity and pH. In Florida, these factors are measured across a wide-ranging network of hydrologic monitoring stations run by entities including the United States Geological Survey, the National Park Service, the Audubon Society, and Florida International University, among others. Biological quality is measured by the presence, condition, and numbers of species of plants, fish, algae, viruses, and other organisms living in the water.

Then, there is the chemical side of water quality, which concerns nutrients, such as nitrogen, phosphorus, and carbon

sulfides. These are harder to measure, according to Dr. Henry Briceño, who heads the Water Quality Monitoring Network research group at Florida International University.

Briceño has been monitoring nutrient levels in Florida’s waters over the past 30 years. Looking at the data, Briceño said that generally: the nutrient concentrations in Florida Bay and off the Keys are rising (which means that the water quality is declining).

“There are some fluctuations, but we see a general increase” in nutrient concentrations, he said, “likely because of anthropogenic inputs.” In other words: Where there are more people, there is more pollution.

Human-made chemicals, like fertilizers and pesticides, affect the chemical quality of the water by altering its nutrient levels, which might make it more or less hospitable for certain species. A March 2022 state-by-state water quality report published by the Environmental Integrity Project noted that Florida’s toxic algae blooms, exacerbated by residential lawn care and agricultural chemicals, have become “an almost annual event.” Meanwhile, Florida ranks in the country’s top states for factors like “acres of lakes deemed too polluted for swimming and aquatic life” and “most square miles of polluted estuaries,” according to the report.

That said, some water quality projects in South Florida have had a positive impact. “We generally saw some slight improvements—declines in those fecal contamination markers— that we could possibly attribute to the transfer from septic tanks to a central sewer system in the Florida Keys,” Briceño said. “That’s a good sign that the removal of our septic tanks—that was a positive thing. So, we’re continuing that work. But the inputs of nutrients from other sources are still occurring.”

The well-known fishing area of Snake Bight within Florida Bay. Photo: Pat Ford

IS WATER QUALITY IN FLORIDA BAY AND THE KEYS GOOD OR BAD?

So, is South Florida’s coastal and marine water quality “good” or “bad”? Karen Bohnsack at the Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary, says that while data can show us long-term and short-term trends, there’s no black-and-white answer to the water quality question.

“Unfortunately, there is not a consistent pattern of water quality throughout South Florida,” she said. “It varies based on how the water is flowing, where the rain’s falling, how far along we are with some of the restoration projects that have been put into place.”

Bohnsack is the Associate Director of Water Quality and Ecosystem Restoration at the Sanctuary. Her specific focus is on water quality within the Sanctuary’s boundaries, but her team knows the Florida Keys are influenced by waters from the Gulf

of Mexico, the Caribbean, the Southwest Florida shelf, even the water in the Mississippi River, which drains 40 percent of the United States, not to mention the many inputs within Florida. All of this, Bohnsack says, eventually makes its way to the Keys. That means a lot of factors are well out of her control.

This is where the South Florida Ecosystem Restoration Task Force comes in. An umbrella group of 14 local, state and federal agencies and tribal groups, the Task Force has since 1996 helped coordinate Everglades restoration. With every passing year, Bohnsack says, there is greater interconnectivity, partnership, and awareness that water management, infrastructure, and restoration decisions made upstream affect the system all the way to its farthest southern reaches.

“We are 20-plus years into Everglades restoration at this time, and it’s a really exciting time, because we are finally reaching the point where some of these projects are being put online, and enough of them are in place that we can actually start to anticipate and see benefits associated with them,” Bohnsack said. “Just understanding that we need to make sure that we’re thinking all the way downstream when these decisions are being made at a project level is a sea change in how people are thinking about these natural resources across the state—and collaborating to protect them.”

HOW INFLUENTIAL IS WATER QUALITY ON SOUTH FLORIDA’S FISHERIES?

According to biologist Peter Frezza, who previously ran a hydrologic monitoring network in a coastal mangrove zone of Florida Bay, water quality is an important factor in the health of Florida’s fisheries, but he isn’t so sure that a degradation of water quality is the reason some of Florida’s most prized fish populations are in decline.

“That’s just one of the issues,” he said of water quality. Other human factors, from habitat loss, fishing pressure, and other management issues, he says, are worth a hard look. “Direct

Juvenile tarpon depend upon healthy mangrove habitats and clean water.

Photo: Pat Ford

Permit follow a ray in the Florida Keys. Without clean water, scenarios like this won’t happen. Photo: Tyler Bowman

Juvenile tarpon depend upon healthy mangrove habitats and clean water.

Photo: Pat Ford

Permit follow a ray in the Florida Keys. Without clean water, scenarios like this won’t happen. Photo: Tyler Bowman

pressure has way more of an effect [on Florida’s fish populations] than people realize,” he said, “even in a catch-and-release fishery.”

Today, Frezza is the Environmental Resources Manager in the village of Islamorada in the Keys.

“In the very early ‘90s, if you read some of those accounts, they really did think that that was the end of the fishing in Florida Bay. And if you talk to a lot of long-time anglers in Florida Bay, we’ve had two episodes where people just thought, ‘Oh, it’s the end, this is it, it’s over’” with regard to water quality, he said, referencing major algal blooms and seagrass die-offs in recent years. “But you know what? The grass came back, and it came back really quick, and it’s never looked prettier than it does right now. It’s beautiful. There are a few areas out in western Florida Bay where the grass hasn’t fully come back to the extent it was prior to the last die-off, but it’s getting there,” he said.

This ability to rebound is called resilience, and he is “fully confident” Florida’s fisheries are resilient enough to adapt and survive under current conditions. It’s especially helpful, though, he says, when these ecosystems get an occasional break from human pressures—like a “dry January” of abstinence from human interference.

“We’ve had a couple of really good examples of a release of pressure in our environment, with the last one being during the pandemic,” he noted. Two hurricane events, in 2005 and 2017, led to restricted access and even closures of parts of Everglades National Park. Following those closures, the rebound of game fish populations was “nothing short of remarkable,” Frezza recalled. “What happens during those events, when there’s a release of pressure—it’s amazing,” he said. “You’ll hear that over and over from people.”

As of now, however, those releases only result from acts of God. “We’ve just got to give it a chance [to recuperate once in a while]. And there are ways to give it a chance,” he said. “We could certainly manage better.”

Mangroves help to hold our coasts intact and filter the water.

Photo: Ian Wilson Everglades restoration will benefit fish and other wildlife. Photo: Pat Ford

MANAGING FOR RESILIENCE

Stabenau at Everglades National Park says these vividly positive environmental responses to releases in human pressures are “an important indicator of how resilient the system actually is.”

“It’s not unusual to talk to somebody out in the park and have them say, ‘Hey, you know, I was so excited to come down here. I used to fish for this with my grandfather as a child, at this location, with this bait, at this time of year,’ and they want exactly that experience that their grandfather gave them as a child,” he said. “They’re thinking back to five years old, and they’re standing there at 70, and they’re expecting that it’s all exactly the same. Not being the same is being interpreted as a failure of management [on the part of] the Parks.”

That’s isn’t quite right, Stabenau said: Waterways shift; water levels change; ecosystems evolve. Stabenau says his mission is to get people thinking in a more dynamic sense about the park, helping visitors, and colleagues, both see not what they remember, but what’s new, in the dynamic, resilient system that is the Everglades.

It’s a relatively new perspective on parks management, he says, even a cultural shift, and it will take time for people to adopt it. But with the inevitability of increasing human habitation and human pressures in South Florida’s coastal ecosystems, combined with climate change, and with Everglades restoration projects coming online to restore the freshwater balance to the extent humanly—and naturally—possible, there is no denying: This is a system in constant flux.

Some areas struggle with pollution, runoff and wastewater issues. Some areas are seeing positive trends in response to new water quality initiatives, or upgraded water treatment infrastructure. Sometimes water quality is “good,” sometimes it’s “bad.” But the experts paying the closest attention to the largest collections of data aren’t willing to be so black and white about it.

“Come here every year. See what’s new,” Stabenau said. “Experience your park, your way, with your family—but teach

your children that they should be coming back again and again, to see how the place is changing, to see what it becomes, to see the system dynamically over decades, and share in that changing system.”

Alexandra Marvar is a freelance journalist based in Savannah, Georgia. Her writing can be found in The New York Times, National Geographic, Smithsonian Magazine and elsewhere.

Clean water means healthy seagrass, which is home to abundant tarpon prey. Photo: Pat Ford

An angler fights a fish in Florida Bay. Photo: Pat Ford

Through the Guides Conservation Captain Q&A

Captain Scott Collins

Marathon, Florida

How long have you guided in the Florida Keys?

I got my Captain’s License 33 years ago, but only fished part-time for many years. I’ve been making my living as a full-time guide now for almost 19 years.

Who taught you how to flats fish?

I started out flats fishing as a kid with my father, who had also moved into guiding when I was young. As his knowledge base grew, so did mine. I had loved it from the start, and to say I bugged him constantly with questions would be an understatement! So, that gave me a huge foundation. As I got older and went out on my own, I feel like I continued to learned from so many great resources. I am a believer that there’s no greater teacher than time spent on the water. That’s where you really learn it.

Tell us about what it was like to be a part of the worm fly “discovery”?

I won’t lie, it was pretty incredible. I’m so fortunate to have been a small part of it. “Worm flies” had already been around for decades, but really, more than anything, the techniques of how it was being fished is what really changed the game. Although, one particular worm pattern early on made the notoriously stubborn oceanside tarpon react in a way we had never seen or expected.

Seeing how tarpon respond to the worm fly now compared to when you first discovered it, what does it tell you about the fish, and how they adapt to us fishing for them?

That’s a great question, as I often think about the changes in fish behavior over the years. There’s no question they don’t eat the worm fly as well as they did 17 years ago. Most assume that the fish “learn” not to eat a certain pattern as time goes on, especially after it stings them multiple times. But a great worm imitation is just that, an imitation of a real worm they eat over and over, year after year. They aren’t shy when it comes to eating the real thing, and our flies are pretty darn good imitations, thus they still fall for it.

It’s interesting that the original worm fly, that was so incredibly deadly in the beginning of the worm revolution, is a fly I rarely fish anymore. Most times they just aren’t interested in it. It is very realistic looking, but a darker shade than what we use today, and they just don’t jump on it like they used to. Yet what we use today we’ve been using for many years now, and they continue to fall for it. Not as well as in the early days I mentioned, but it works plenty well enough. So, I always wonder if it was just some environmental factors, unknown

to us, that allowed that original fly to work during that period. Kinda like we got lucky and found out “what they were biting on” for a number of years. Something changed, thus we had to change our flies. Did they actually learn not to eat it? Or does it just not match what they want now? I feel that way about all flies, I guess. So, I always question what they’ve “learned” versus what factors change and thus change their willingness to bite. Take their migration habits for example. There’s no question that the oceanside tarpon get run over, spooked, cast at, hooked, etc. over and over, year after year.

You’d think they’d “learn” to swim out offshore a little further and avoid a lot of headaches! Thankfully, I don’t believe they can change their habits ingrained in them from thousands of years ago. I really think we don’t know as much as we think we do.

Do you think someone will crack the code on a new hypereffective tarpon fly again?

Yes, I do. Like I was saying before, I believe there’s so many variables in the marine environment and they are always changing. Someone will try some seemingly bizarre fly, and the fish will come out of their scales to eat it because it triggers them to eat it based on some factors that are present. My question will be, how long will the fish stay dialed into it? Often some fly works great for a little bit then it quickly goes ice-cold. You’re always looking/hoping for that fly that works most of the time, but also for years on end. I also don’t believe there is a single silver bullet for all the places we fish for tarpon. Even the “great worm fly” has never worked in all months and in all areas.

What changes have you seen in the fishery since you started guiding?

Things are so different than when I started guiding full time, almost 20 years ago. Really almost everything has changed, but a couple major differences stand out. Hard to believe it’s been 15 years since

Capt. Collins lands a tarpon in the Florida Keys.

24

Captain Scott Collins

the Keys bonefishery fell off a cliff. That was the first major change I ever witnessed. It was a very frustrating time, and honestly, because I got to live what the fishery once was, it’s still very frustrating and depressing to me. It’s horrific we lost such a world-class fishery, seemingly overnight. Other major change I’ve seen is the increase in the general traffic on the water. There are more skiffs today fishing fewer fish than ever before, but also the general boat traffic, jet skis, rental boats, sandbar-soakers, kiteboards, etc. that blanket the Keys inshore waters are terrifying to watch on many days.

What do you see as the biggest threat to the fishery, and what can be done about it?

I think the two largest threats are water quality and pressure/traffic as I mentioned above. There are a lot of great organizations, like BTT, making huge strides to help our waters, but the overuse of our resources is becoming a runaway train. The Keys are already jammed much of the year, on and off the water, yet the build-out and the world-wide advertising plows forward. Where does it end?

If you had the power to immediately change one thing about the Keys that you think would improve the fishery, what would it be? It would be to somehow eliminate the general overuse and abuse that goes on across all of the shallows throughout the Keys. The inshore fish need breaks from fishing pressure, boat motors, jet skis, swimmers, etc. Too many users over using too many sensitive areas, even some areas that are already designated “protected,” but just not enforced.

Why is it important for anglers to support research and conservation?

If it weren’t for the hunters and fisherman across this country, we wouldn’t have a fraction of the habitat and animals/fish to enjoy that we do. Just like how BTT was started by the fishermen out of need, so much other research and conservation has been developed because of the movements to save and improve what we have. There are so

many factors working against the outdoor world that we all love and enjoy that no one should take it for granted. Get involved!

Tell us about one of your most memorable days on the water. Wow, so many memorable days on the water with so many special people, it’s hard to pick just one. From incredible catches, to exciting tournament wins, to being a kid and experiencing parts of this fishery for the first time, to even the days things went bad out on the water where still today I feel blessed to have made it home. I’ve been blessed to have lived out my fishing/guiding dreams on so many levels that I have the peace of mind to know that my most memorable day on the water is one that I try to repeat as often as I can. That day is having my wife and two daughters out on the water whenever possible, and having them learn and experience even a fraction of what I’ve been lucky enough to. So, any day that they have a great day on the water with me, is a special day for me.

Can you share three tips for catching tarpon on fly in the Keys? When it comes to Tarpon, presentation is everything, even way more important than the fly!

1) Wait Wait Wait...don’t get anxious and cast too early or try and go too far. Let the fish get in your most effective range, and make your shot count. Better to go short rather than too long as you often have time to cast again and dial it in even better.

2) No Slack! Always stay tight to your fly. Once you cast it out there, you’re not fishin’ yet until you get the slack out of your line and you are in control of your fly.

3) Always point your rod directly at the fly. Out of all the amazing things tarpon do, the bite is my favorite part. Seeing the bite can be quite overwhelming, but try to maintain composure, quickly strip tight, and tighten up on the fish. You don’t want any part of the rod in the hook-setting equation, so having it pointed right at the fly when you strip tight will give you a firm strip set. Game on!

TAKING ROOT

BTT joins forces with Bahamian partners and local communities to restore and conserve the mangroves of The Bahamas.

BY CHRIS HUNT AND STAFF REPORTS

BY CHRIS HUNT AND STAFF REPORTS

26 B O N E F I S H & T A R P O N J O U R N A L FALL 2023

A volunteers plants a mangrove in East Grand Bahama. Photo: Nick Roberts

An alliance of conservation groups in The Bahamas is working to restore a mangrove ecosystem that was wiped out by Hurricane Dorian, a massive Category 5 storm and the largest to ever make landfall in the Atlantic.

The human toll from Dorian was heartbreaking—74 Bahamians were confirmed dead and almost 250 people remain missing and are presumed dead—and the long-term ecological damage to the region and its surrounding islands and cays is striking. The storm boasted sustained winds of 185 miles per hour and its slow path across the region denuded and killed mangroves across nearly 70 square miles. Today, islands that were once lush and green thanks to mangrove forests are still mostly barren. Skeletal trunks and limbs poke up from the sand, the reminders of what once was.

Scientists agree that, in time, mangroves will eventually find their way back to these sandy islands, though the timeline for regeneration will be longer than in the aftermath of any previous storm. The important difference is the scale at which mature, propagule-producing trees and their seed banks were lost. And the consensus is that the best response is a science-based effort to give nature a helping hand to not only accelerate recovery but also reduce threats to the system in the intervening years arising from coastal erosion and other degradation to the environment.

BTT was among the first organizations on the seascape to provide that help when it launched the Bahamas Mangrove Restoration Project soon after Dorian’s winds had subsided. Thus far, with the help of Bahamas National Trust (BNT), Friends of the Environment, corporate partner MANG, local fishing guides and lodges, students, community volunteers and other stakeholders, the project has planted 55,000 seedlings.

Early planting efforts have focused on areas where mangroves are most likely to provide the intended “kick-start.” These areas, which once supported tall forests of “fringing” red mangroves prior to Dorian, have the soil nutrients to support

larger trees, and these larger mangroves produce more propagules (seeds) that will help repopulate surrounding areas that lost their mangroves to the storm four years ago.

“Mangroves are so critical to the health of marine ecosystems across The Bahamas,” said BTT President and CEO Jim McDuffie. “They are an essential part of the shallow water environment that makes The Bahamas a premiere destination globally for flats fishing, while also serving as nursery and spawning habitats for a majority of the country’s valuable commercial fisheries. They also provide many other benefits to The Bahamas, not least of which is the promise of protecting coastal communities during a time when our climate is changing so dramatically.”

Ultimately, success in the project will depend on achieving restoration at the right scale. One way to get there is through strategic plantings of seedlings in the right locations and with the right densities to accelerate recovery in specific locations. Another way is to plant even larger numbers of mangrove propagules through large-scale distribution down creek systems and by aerial drops. BTT and its partners are embracing both methods as necessary prescriptions in The Bahamas. Success will also require organizational collaboration at scale.

On Earth Day 2023, BTT, Waterkeepers Bahamas (WKB), and the Perry Institute for Marine Science (PIMS) announced the formation of the Bahamas Mangrove Alliance (BMA), with generous seed funding from the Moore Bahamas Foundation and Louis Bacon Foundation. The announcement followed several months of planning and underscored a commitment that each had made to protect and restore mangroves on Grand Bahama, Abaco, and across The Bahamas.

National media carried the news of how “three influential conservation organizations” had established a new multi-sector coalition to focus on mangrove protection and restoration, research, community outreach, advocacy, and raising awareness

B O N E F I S H & T A R P O N J O U R N A L FALL 2023 27

Representatives from Waterkeepers Bahamas and the Perry Institute for Marine Science joined BTT President and CEO Jim McDuffie (third from right) at the 2023 Earth Day planting event to announce the formation of the Bahamas Mangrove Alliance (BMA). Photo: Micah Ness / Silverline Films

through education.

“After Dorian, our three organizations were first on the ground to assess damage, the first to strike restoration plans, and the first to begin planting,” said BTT President and CEO Jim McDuffie. “It was obvious to all of us how immense this job was going to be, and that we could be more successful and deliver greater conservation outcomes by working together. The emerging BMA gives us the best means of coordination and the best platform to do just that.”

McDuffie said the BMA would help coordinate this effort—the largest mangrove restoration project in Bahamas history—and other mangrove advocacy and conservation efforts under a single umbrella, including nonprofits organizations, national park and fisheries managers, island communities, higher education institutions, and sustainable businesses. And where possible, the BMA will also engage with The Bahamas Government on national and international priorities tied to mangrove health.

Waterkeepers Bahamas, a member of the global Waterkeeper Alliance, has been on the front lines of advocacy and action benefitting the environment of the Clifton and Western Bays, Grand Bahama and Bimini. WKB Executive Director Rashema Ingraham, a native of Freeport who has an impressive pedigree to legendary fishing guides in the region, played an important role in framing the BMA’s charter and mission.

“The BMA recognizes the importance of mangroves to the ‘Blue Economy’ of The Bahamas,” said Ingraham. “Mangroves contribute to the sustainability of fisheries, which are vital for the local fishing economy. Additionally, mangrove habitats attract tourists interested in activities like flats fishing. By protecting and restoring mangroves, the BMA supports economic opportunities tied to the coastal and marine environment.”

Ingraham explained that WKB was excited to be partnering with regionally recognized organizations like PIMS and BTT, saying that together the groups would be able to broaden the

reach and scope of their individual efforts, thereby ensuring the conservation of mangrove forests.

WKB has conducted several mangrove workshops and activities targeting schools and students over recent years. An important aspect of amplifying reach and scope will be to expand engagement by community members in restoration activities and, later, in outreach to protect and conserve mangroves all over the country. The successful joint planting event on Earth Day demonstrated the power of the approach as more than 100 volunteers participated, including fishing guides and lodge staff, school students, representatives from the University of The Bahamas, community volunteers, corporate partners, and government officials. Together the volunteers planted 3,200 mangroves along Rocky Creek in East Grand Bahama.

The BMA and its member organizations are using the best science available to direct restoration work, with scientists from BTT and the Perry Institute for Marine Science joining forces.

PIMS Director Dr. Craig Dahlgren said his organization has worked on mangrove restoration efforts since the mid-1990s, and it will serve in a leadership role in conducting research and monitoring necessary to both measure success in the current project and frame new protocols for mangrove restoration.

Using PIMS’ science and mapping capability, Dahlgren said the alliance can monitor the progress of the restoration efforts to see if the mangroves are returning and if the new plantings can function as fish nurseries.

“We’re using drones and remote sensing to create some very detailed maps that show where the restoration is most needed,” Dahlgren said. And, predictably, the immediate need is most pronounced on Grand Bahama and Abaco, where Dorian wiped out the vast majority of the region’s mangroves.

There are many other places in The Bahamas where mangrove restoration is needed, and not just in the paths of devastating hurricanes. Once the work on Grand Bahama and Abaco is at a point where it can move forward without constant monitoring, the BMA plans to start tackling some of these other areas. They include sites where mangroves have been impacted by everything from half-a-century-old logging roads to abandoned salt-pen operations to more pronounced coastal development issues that are a constant challenge. At the same time, the BMA intends to also engage deeply with Government on new policy measures to prevent loss and conserve mangroves at a country-wide scale.

“Mangroves on Grand Bahama and Abaco need to be restored,” McDuffie said. “And wetlands and mangrove systems throughout The Bahamas need to be protected. BTT and our BMA partners share a commitment and fierce determination to get it done.”

Chris Hunt is an award-winning freelance journalist and author and an avid fly fisher based in Idaho and Florida. He writes frequently about conservation, fly fishing and travel. His most recent book, The Little Black Book of Fly Fishing, is available online and at finer bookstores.

28 B O N E F I S H & T A R P O N J O U R N A L FALL 2023

Volunteers prepare to transport mangroves seedlings to nearby planting sites in East Grand Bahama.

Photo: Micah Ness / Silverline Films

B O N E F I S H & T A R P O N J O U R N A L FALL 2023 29

Students, volunteers, government officials, and fishing guides plant mangroves with BTT staff and partners along Rocky Creek in East Grand Bahama.

Photo: Micah Ness / Silverline Films

Participants in BTT’s Earth Day event planted 3,200 mangroves in East Grand Bahama. Photo: Micah Ness / Silverline Films

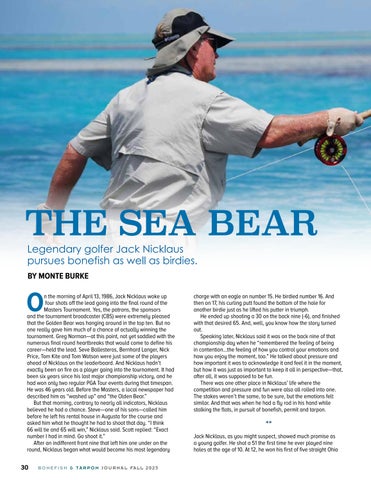

THE SEA BEAR

BY MONTE BURKE

On the morning of April 13, 1986, Jack Nicklaus woke up four shots off the lead going into the final round of the Masters Tournament. Yes, the patrons, the sponsors and the tournament broadcaster (CBS) were extremely pleased that the Golden Bear was hanging around in the top ten. But no one really gave him much of a chance of actually winning the tournament. Greg Norman—at this point, not yet saddled with the numerous final round heartbreaks that would come to define his career—held the lead. Seve Ballesteros, Bernhard Langer, Nick Price, Tom Kite and Tom Watson were just some of the players ahead of Nicklaus on the leaderboard. And Nicklaus hadn’t exactly been on fire as a player going into the tournament. It had been six years since his last major championship victory, and he had won only two regular PGA Tour events during that timespan. He was 46 years old. Before the Masters, a local newspaper had described him as “washed up” and “the Olden Bear.”

But that morning, contrary to nearly all indicators, Nicklaus believed he had a chance. Steve—one of his sons—called him before he left his rental house in Augusta for the course and asked him what he thought he had to shoot that day. “I think 66 will tie and 65 will win,” Nicklaus said. Scott replied: “Exact number I had in mind. Go shoot it.”

After an indifferent front nine that left him one under on the round, Nicklaus began what would become his most legendary

charge with an eagle on number 15. He birdied number 16. And then on 17, his curling putt found the bottom of the hole for another birdie just as he lifted his putter in triumph.

He ended up shooting a 30 on the back nine (-6), and finished with that desired 65. And, well, you know how the story turned out.

Speaking later, Nicklaus said it was on the back nine of that championship day when he “remembered the feeling of being in contention…the feeling of how you control your emotions and how you enjoy the moment, too.” He talked about pressure and how important it was to acknowledge it and feel it in the moment, but how it was just as important to keep it all in perspective—that, after all, it was supposed to be fun.

There was one other place in Nicklaus’ life where the competition and pressure and fun were also all rolled into one. The stakes weren’t the same, to be sure, but the emotions felt similar. And that was when he had a fly rod in his hand while stalking the flats, in pursuit of bonefish, permit and tarpon.

Jack Nicklaus, as you might suspect, showed much promise as a young golfer. He shot a 51 the first time he ever played nine holes at the age of 10. At 12, he won his first of five straight Ohio

30 B O N E F I S H & T A R P O N J O U R N A L FALL 2023

**

Legendary golfer Jack Nicklaus pursues bonefish as well as birdies.