Craftsmanship meets conservation with the limited-edition Bonefish & Tarpon Trust SDS and ROVE reels, featuring custom artwork by Derek DeYoung and Eric Estrada. Part of the Abel Artist Series, each laser engraved reel supports vital initiatives like Bahamas Mangrove Restoration and Bonefish Spawning Research.

Proudly designed, machined, and assembled in the USA.

Dr. Aaron Adams, Monte Burke, Bill Horn, Jim McDuffie, Carl Navarre, T. Edward Nickens, Kellie Ralston

Publication Team

Publishers: Carl Navarre, Jim McDuffie

Editor: Nick Roberts

Editorial Assistant: Isabel Lower

Layout and Design: Scott Morrison, Morrison Creative Company

Contributors

Dr. Aaron Adams

Monte Burke

Sue Cocking

Chico Fernandez

Chris Hunt

Alexandra Marvar

Kris Millgate

Chester Moore

T. Edward Nickens

Photography

Cover: Adrian Gray

Dr. Aaron Adams

Dr. Ben Binder

Tyler Bowman

Patrick Clayton

Riley Cummins

Marty Dashiell

Zaria Dean

Dan Diez

Greg Dini

Pat Ford

Dr. Stephen Kajiura

Benedict Kim

Joe Klementovich

Sarah Hamlyn

Justin Lewis

Brendan McCarthy

Mark Rehbein

Reagan Renfroe

Tommy Robinson

Robbie Roemer

Nick Roberts

Nick Shirghio

Zoe Szabo

Nate Weinbaum

Cover

A permit swims along a coral reef in Roatan, Honduras. Photo: Adrian Gray

Bonefish & Tarpon Journal 2937 SW 27th Avenue Suite 203 Miami, FL 33133 (786) 618-9479

Bonefish & Tarpon Journal is printed on a sappi paper that is SFI® ≥20% Certified Forest Content and 10% recycled fiber.

Carl Navarre, Chairman of the Board, Islamorada, Florida

Evan Carruthers, Vice Chairman of the Board, Maple Plain, Minnesota

Jim McDuffie, President and CEO, Miami, Florida

John Davidson, Treasurer, Atlanta, Georgia

John D. Johns, Secretary, Birmingham, Alabama

Tom Davidson, Founding Chairman Emeritus, Key Largo, Florida

Harold Brewer, Chairman Emeritus, Key Largo, Florida

Russ Fisher, Founding Vice Chairman Emeritus, Key Largo, Florida

Bill Horn, Vice Chairman Emeritus, Marathon, Florida

John Abplanalp

Stamford, Connecticut

Rich Andrews

Denver, Colorado

Stu Apte Tavernier, Florida

Rodney Barreto

Coral Gables, Florida

Adolphus A. Busch IV Ofallon, Missouri

Ali Gentry Flota

Richmond, Virginia

Dr. Tom Frazer

Tampa, Florida

Jeff Harkavy Coral Springs, Florida

Doug Kilpatrick Summerland, Florida

Jerry Klauer New York, New York

Dr. Michael Larkin St. Petersburg, Florida

Thorpe McKenzie Chattanooga, Tennessee

Ambrose Monell New York, New York

Sandy Moret Islamorada, Florida

Tim O’Brien Harlingen, Texas

Clarke Ohrstrom The Plains, Virginia

Advisory Council

Dan Berger, Key West, Florida

Bob Branham, Plantation, Florida

Paul Dixon, East Hampton, New York

Chris Dorsey, Littleton, Colorado

Chico Fernandez, Miami, Florida

Mike Fitzgerald, Wexford, Pennsylvania

Pat Ford, Miami, Florida

Christopher Jordan, McLean, Virginia

To

Dr. Jennifer Rehage Miami, Florida

Vaughn Roberts Nassau, Bahamas

Kris Rockwell Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania

Diana Rudolph Livingston, Montana

Rick Ruoff Willow Creek, Montana

Adelaide Skoglund Key Largo, Florida

Noah Valenstein Tallahassee, Florida

Bill Klyn, Jackson, Wyoming

Clint Packo, Littleton, Colorado

Mitch Menendez, Portland, Oregon

Jon Olch, Park City, Utah

Chris Peterson, Titusville, Florida

Steve Reynolds, Memphis, Tennessee

Bill Stroh, Miami, Florida

Krissy Hewes Wiborg, Miami,

Bonefish & Tarpon Trust reaches a 15-year milestone in The Bahamas, where it works to restore coastal habitats and conserve the flats fishery in collaboration with the government, local communities, fishing guides, and partners. T. Edward Nickens

18 The Enthusiast

Thorpe McKenzie will receive the Lefty Kreh Award for Lifetime Achievement in Conservation at Bonefish & Tarpon Trust’s 14th Annual NYC Dinner & Awards Ceremony. Monte Burke

Belize is protecting 5% more of its marine areas in the next five years. Bonefish & Tarpon Trust is helping to ensure these protections apply to some of the world’s richest bonefish, tarpon, and permit habitats.

Alexandra Marvar

Bonefish & Tarpon Trust will honor founding member Jeff Harkavy, artist Tim Borski, and Chris and Wendi Peterson, the owners of Hell’s Bay Boatworks, for their many contributions to fisheries conservation. Sue Cocking

Where science meets action!

The theme for the 8th International Science Symposium speaks volumes about BTT’s approach. Our mission success depends upon the effective translation of science into action, whether it’s the restoration and conservation of important coastal habitats, improvements to fisheries management, or advocacy and policy to ensure water quality.

As this issue of the Bonefish & Tarpon Journal goes to press, we’re pleased to share our latest science-driven accomplishments.

Acting on research provided by BTT, the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission (FWC) adopted a new rule in August to provide targeted, seasonal protection for a critically important bonefish pre-spawning aggregation (PSA) in Biscayne National Park. The measure prohibits all fishing at the site during peak bonefish spawning season, from March through May. During this time, bonefish school by the thousands at the PSA site before swimming offshore to spawn in deep water.

The size of the area covered by the new rule is just under two square miles—less than half of 1% of the bay’s 429 square miles— but its protection will provide out-sized benefits when it comes to sustaining recovery of the bonefish population across the Florida Keys. Tagging data reveal that bonefish spawning at the BNP site were from local waters and more distant flats, including two that had traveled more than 50 miles from their tagging location. In the same way, their spawn is cast across an Upper Keys region thanks to their broadcast method of spawning and nearshore currents that transport the bonefish larvae.

BTT scientists identified the Biscayne Bay PSA in the spring of 2023. The discovery east of Elliott Key was the first to be documented in Florida waters and likely the first to be observed by Keys fishing guides and anglers in many years, if not decades. It followed a long and exhaustive search by our Florida-based team led by Dr. Ross Boucek, BTT’s Director of the Florida Keys Initiative.

The significance of the discovery cannot be overstated. Yet, it was just the first step in a multi-pronged approach. Research without action is often just a tree falling in the forest that nobody hears. In this case, changes in resource management were needed.

Bonefish are very sensitive to disturbance in the prespawning aggregation stage, so protecting their spawning sites is essential to ensuring successful spawns and a stable population. Further underscoring the importance of such protections is the fact that bonefish typically return to established spawning sites over the years, with the resulting larvae benefiting the flats fishery locally and regionally. A new study by Dr. Claire Paris-Lumouzy, Professor of Ocean Sciences at the University of Miami, indicates that 35% of larvae spawned at the Biscayne site in April 2023 site likely remained in Biscayne Bay. Additional analysis will provide further understanding as to where the remaining larvae landed. Dr. Paris-Limouzy’s project was sponsored by BTT and will be featured in an upcoming issue of the Bonefish & Tarpon Journal. These are exciting developments and provide encouraging signs

Carl Navarre, Chairman

Jim McDuffie, President

for the continued recovery of Florida Keys bonefish. But our job isn’t done yet. As with the rule enacted at Western Dry Rocks to protect spawning permit in the Keys, BTT will continue to be involved in the monitoring of the Biscayne Bay PSA, as the recently approved rule changes include a five-year sunset provision. Our objectives will include determining the efficacy of the seasonal closure and based on that assessment, making further recommendations to FWC for future management at the site. At the same time, BTT is continuing its search for another bonefish pre-spawning aggregation off of Key West. Recent tracking data have narrowed the search area, providing new clues to help our researchers home in on the PSA during the 2025-26 spawning season.

We appreciate the leadership and decisive steps taken by Florida FWC, the assistance of Florida Keys fishing guides who helped with the search and discovery of the Biscayne Bay PSA, and all who lent their voices to the call for a spawning season closure—guides, anglers, industry leaders, and you! Thanks to your commitment and support, BTT is able to translate science into action in so many ways that benefit the flats fishery. You can learn more about the Biscayne Bay PSA and other projects at BTT’s 8th international Science Symposium, which convenes on November 7-8, 2025, in Fort Lauderdale, Florida. Additional information and registration can be found at: BTT.org/symposium. In the meantime, we hope you will enjoy this issue of the Bonefish & Tarpon Journal. T. Edward Nickens takes a look at BTT’s accomplishments in The Bahamas over the past 15 years, which include research to protect vital bonefish habitat and restoration of mangroves and tidal creeks. Kris Millgate delves into BTT’s exciting new research into shark depredation. The project will help determine future deterrent strategies and inform fishery management decisions. Also in this issue, Alexandra Marvar reports on the Blue Bond in Belize and how BTT is working with partners to ensure that the most important flats fishing areas are included. And we salute our conservation heroes who will be inducted into BTT’s Circle of Honor this fall—Jeff Harkavy and Thorpe McKenzie, Chris and Wendi Peterson, and Tim Borski. Their leadership and many contributions to our mission have driven BTT’s success as the leader in flats conservation.

Together, we’re making a real difference for our shared flats fishery, as we hope you will see evidenced in the pages that follow. As always, we thank you for your commitment to conservation and advocacy on behalf of bonefish, tarpon, and permit, and the waters they inhabit.

Bonefish & Tarpon Trust held its inaugural Washington, D.C. fly-in, June 4-5, with BTT board members attending Capitol Hill Oceans Week and meeting with elected leaders and policymakers, including NOAA Fisheries Assistant Administrator Eugenio Piñeiro Soler, Senator Rick Scott, Representative John Rutherford, Representative Diaz-Balart’s office, and the Environmental Protection Agency. Conversations focused on the importance of habitat and water quality for the flats fishery, protections for Biscayne Bay, and shark depredation. BTT is grateful for the subsequent introduction of the SHARKED Act in the U.S.Senate by Senators Brian Schatz (D-HI) and Rick Scott (R-FL).

Bonefish & Tarpon Trust worked with Florida Governor Ron DeSantis and state legislators during Florida’s 2025 legislative session to build upon recent progress in the conservation of the state’s coastal and marine resources. BTT advocated for funding and programs that will improve water quality and fish habitat along the Florida’s coasts and estuaries. The Everglades are the lifeblood of South Florida’s world-class fisheries, and the restoration of this vital ecosystem is a critical component to the health of the state’s natural resources. BTT advocated in the 2025 legislative session for the sustained and robust funding for Everglades restoration and water quality projects that will benefit the Everglades as well as Florida’s coastal ecosystems, communities, and fisheries.

BTT attended the ribbon cutting on the C-43 Reservoir that will capture and store stormwater runoff from the C-43 basin and enable better control of water flow to the Caloosahatchee Estuary. In addition, the state of Florida has entered into a landmark agreement with the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers to accelerate construction on key components of multiple Everglades projects, including the Everglades Agricultural Area Reservoir.

BTT has welcomed Mitch Menendez, Nike’s GM of Global Product Licensing, and acclaimed author Jon Olch to the Advisory Council.

Born and raised in Southwest Florida, Menendez has worked in the sports industry for more than 40 years, with 35 spent with Nike. His career spans experiences in sales, operations, and product management. Menendez grew up a spin fisherman, but learned to fly-fish upon moving to his current home in Oregon. Saltwater fly-fishing in The Bahamas, Mexico, Belize, and Florida led him to support BTT.

“I’m honored to join BTT’s Advisory Council and be a part of such a science-based conservation organization,” said Menendez. “Having watched the destruction of mangrove habitat over these past few years in Southwest Florida and The Bahamas, it has piqued my interest in volunteering and participating in habitat recovery and preservation. I believe the work of BTT will continue to protect the habitats and promote the growth of the species and surrounding wildlife for generations to come.”

Olch is a longtime supporter of BTT’s permit research and the author of the celebrated book, A Passion for Permit. The two-volume set, encompassing more than 1,200 pages, covers the scientific attributes of permit and explores the conservation measures necessary for the species’ long-term protection. An innovative fly-tier, Olch became one of Umpqua Feather Merchants’ original contract fly-tiers in 1983, with his patterns appearing in numerous fly-tying books over the years. Olch has also moderated the Permit Panel at BTT’s International Science Symposium.

“I am honored and excited to be joining BTT’s Advisory Council!” said Olch. “As the author of A Passion For Permit, I am particularly interested in the ongoing BTT scientific research throughout the Caribbean into permit movement, population assessments, the ongoing exploration to identify major spawning locations, and the pursuit of protective measures for such a superb and iconic species.”

Bonefish & Tarpon Trust thanks all of the anglers and guides who took the Florida Keys Bonefish Survey! Your insights will help to quantify changes in the fishery—critical information that BTT will use to advocate for improvements needed to restore it.

The survey results show that bonefish numbers climbed steadily from the 1960s, peaking in the 1980s. However, this was followed by a sharp decline that lasted through 2010. Since then, there’s been a tentative bounce-back—encouraging, but not reaching the heyday of previous decades. The exact timing of this bounce-back and its strength also vary across regions. Scan the QR code to continue reading.

At the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission’s August meeting, FWC Commissioners voted to pass a targeted, three-month no-fishing closure (March 1 through May 31) of the bonefish pre-spawning aggregation (PSA) site discovered by BTT scientists in Biscayne Bay National Park (BNP). These protections must be renewed by the Commission after five years. The Biscayne Bay PSA site is the first to be scientifically documented in Florida waters and was identified after more than three years of BTT’s research, in collaboration with FWC and BNP researchers. Bonefish school by the thousands there before swimming offshore to spawn in deep water. Protecting the site during spawning season is critical for the continued recovery of Florida’s bonefish population.

BTT thanks the FWC Commissioners as well as the guides, anglers, and our conservation partners for their support of this science-based conservation measure. BTT and FWC will continue to monitor the site and measure the effectiveness of the closure over the next five years. The new regulations take effect next year and close a 1.74-square-mile area to all fishing during the seasonal closure. With the help of fishing guides, BTT is now researching a potential spawning site in the Lower Keys near Key West.

Bonefish & Tarpon Trust has launched a new permit tagging study in Belize and Mexico, which will identify important habitats and movement patterns of permit to inform better management in the region. The study, which builds on previous dart-tagging research, will also shed light on permit spawning migrations between the two nations. BTT is collaborating with fishing lodges and guides as well as resource managers and local universities.

BTT scientists are using small acoustic tags, which are surgically implanted and have a battery life of approximately one-and-a-half years. The tags send out supersonic pings that include a unique identification code. When a tagged permit swims within roughly 500 yards of one of the underwater receivers, which are placed strategically throughout the region, the receiver detects the tag and records the tag ID code, along with the date and time of the detection. At six-month intervals, scientists retrieve the receivers from the seafloor and download the stored data, which they use to track the movements and habitat use of each tagged permit. Learn more and support the study at: BTT.org/btt-permit

Bonefish & Tarpon Trust and partners, with invaluable support from the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission (FWC), have concluded a comprehensive research study into the causes of the “spinning fish” phenomenon in the Florida Keys. The report of the findings and recommendations has been provided to FWC. This phenomenon, which first emerged in fall 2023, impacted over 80 species, including the critically endangered smalltooth sawfish. While reports of spinning fish declined during the spring and summer of 2024, researchers observed abnormal behavior and sawfish mortalities re-emerging in smaller numbers starting in late 2024 and early 2025.

Recent research from BTT and our partners has shed new light on the potential cause and its effects. The main suspect is a microscopic algae named Gambierdiscus that is found on the seafloor. Elevated levels of Gambierdiscus have been detected in water and bottom samples from affected areas, and we know these algae produce potent neurotoxins. Researchers have now confirmed the presence of these very toxins in affected fish tissues and water samples—a major breakthrough.

What does this mean for the fish? Studies suggest that they are primarily exposed to these toxins through their gills, which then accumulate in organs like the liver, potentially damaging nerve cells. While Gambierdiscus levels were higher during the initial peak, current concentrations are sometimes at or only slightly above background levels, even as some fish continue to show symptoms. This complex situation suggests that other factors, residual effects, or specific environmental triggers like the heat wave of summer 2023, also play a role. Every piece of information that’s uncovered helps guide the ongoing investigation to protect our fisheries. Upon completion of this research project by BTT, FWC assumed the lead role as of July 1, 2025, for future monitoring and mitigation.

BY CHESTER MOORE

Bonefish, tarpon, and permit are more than just bucket-list targets for anglers. These elusive and powerful fish are inhabitants of some of the most visually stunning yet environmentally fragile ecosystems on the planet. From the seagrass meadows of Florida to the mangrove-laced shores of Belize, these fisheries rely on healthy habitats, clean water, and informed stewardship.

That’s why Bonefish & Tarpon Trust’s 8th International Science Symposium, scheduled for November 7–8, 2025, in Fort Lauderdale, Florida, aims to bring together science, fishing experience, and conservation in one collaborative space.

“This is a rare integration of the fishery, science, and resource management all in one,” said Dr. Aaron Adams, BTT’s Director of Science and Conservation. “There are other events where scientists, anglers, or policymakers gather separately, but bringing everyone together in one place? That’s where real solutions happen.”

One of the clearest examples of this type of collaboration turning into conservation success is the closure of Western Dry Rocks in the Florida Keys during permit spawning season. BTTfunded science, which was a collaboration of researchers, guides, and anglers, identified its critical role as a spawning site. Guides, anglers, NGOs, and scientists united to advocate for protection while policymakers in Florida acted on that evidence.

“We had the science, we had community support, and we had momentum,” Adams said.

This two-day event is a shared setting for marine biologists,

guides, policymakers, and passionate anglers to translate cutting-edge science into actionable conservation, like the big win for spawning permit at Western Dry Rocks. And while rooted in Florida’s flats, the BTT Symposium is international in both scope and spirit. This year’s event welcomes participants from Belize, Mexico, Cuba, Costa Rica, Brazil, and beyond, underscoring the global nature of flats fisheries.

Dr. Adams, who has been part of every BTT symposium since its inception, sees this gathering as the embodiment of BTT’s mission.

“We’ve always insisted that scientists can’t solve problems alone,” he said. “Nor can policymakers or anglers. But together, when each group shares its unique knowledge, we can tackle the root issues threatening these fisheries.”

The structure of the event reflects that ethos. Instead of presenting their work strictly academically, researchers will explain how it directly applies to management and conservation.

“It’s not just about methods or results. It’s about making a difference,” Adams said.

Kellie Ralston, BTT’s Vice President for Conservation and Public Policy, is equally enthusiastic.

“This is where science meets policy,” she said. “Sometimes policy informs what science needs to look into. Other times, new

research pushes for urgent policy changes. It’s a two-way street— and the symposium is the intersection.”

Ralston sees the 2025 event as the most dynamic yet, featuring international guide exchanges and meaningful dialogue about habitat protection and restoration at the landscape scale.

“Whether your concern is pharmaceuticals in the water, mangrove die-off, or spawning site closures, it’s all connected,” she said. “The symposium helps people see the big picture.”

One of Ralston’s most anticipated themes is enforcement.

“Regulations are meaningless without proper enforcement. We’re working to strengthen relationships between enforcement agencies in Florida, Belize, and The Bahamas,” she said.

This includes supporting the Bahamas Wildlife Enforcement Network and exploring shared enforcement practices across borders.”

JoEllen Wilson, BTT’s Juvenile Tarpon Habitat Program Manager, leads one of the symposium’s most popular sessions—on tarpon. But this year, the focus goes deeper.

“We’re not just talking about juvenile tarpon. We’re highlighting region-specific threats and the management solutions that work and can be adapted elsewhere,” Wilson said.

For instance, researchers from Cuba, Costa Rica, and Texas will

present on issues ranging from catch-and-release mortality to habitat degradation.

“It’s about gathering data that leads to action. Everything we do is aimed at enhancing the fishery, not just studying it,” Wilson said.

She also emphasized how the symposium demystifies science for everyday anglers.

“We take complex data and translate it into actionable steps. It’s empowering for the community to realize how much science is working behind the scenes to protect what they love.”

Jessica McCawley, Director of the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission’s Division of Marine Fisheries Management, praised the event’s inclusivity.

“We’re just one piece of the puzzle. The beauty of the symposium is how it brings everyone—scientists, policymakers, guides—into the same room to discuss solutions holistically,” she said.

Seagrass conservation is a prime example.

“Seagrasses are essential for fish like snook and redfish, but they’re also critical for bonefish and permit. We use habitat health as a management tool, and BTT’s science has been pivotal in shaping our policies,” she said.

McCawley highlighted the Biscayne National Park bonefish

A school of bonefish in the Florida Keys. Photo: Tyler Bowman

pre-spawning aggregation discovery, which is a project driven by BTT’s research. At the August 2025 FWC commission meeting, FWC commissioners voted to protect this important PSA site in Biscayne Bay. The new rule closes the small (1.74 square mile) area to all fishing from March through May during bonefish spawning season.

“Without BTT’s data, we wouldn’t be where we are today,” she said.

Dr. Andy Danylchuk, BTT Research Fellow and member of the BTT Circle of Honor, has participated in nearly every symposium.

“This isn’t just another academic conference. It’s a celebration of conservation wins, a prioritization of future research, and a call to action,” he said.

Danylchuk believes the event’s strength lies in its accessibility.

“You don’t have to be a scientist to understand what’s being shared here. It’s science in plain language, shaped by guides and anglers who are out on the water hundreds of days a year.”

He added that some of his lab’s research ideas stem from conversations at the symposium.

“Stakeholder questions often guide our work more than academic theory,” he explained. “This event helps us close the gap between knowledge and action.”

The 8th International Science Symposium isn’t just for professionals. It’s for anyone who loves flats fishing and wants to be part of the solution.

“This is where education becomes advocacy,” Adams said. “You’ll walk away with the tools to make better decisions, influence others, and help protect these iconic species.”

From seagrass decline and juvenile tarpon habitat restoration to increasing shark depredation and critical enforcement gaps, the symposium tackles it all with honesty, urgency, and collaboration.

“Our biggest issues aren’t going to be solved by one group alone. But in this room, with this mix of people, we have a real shot,” Ralston said.

So whether you’re a scientist, a seasoned guide, a policymaker, or an angler who just caught their first bonefish on the fly, there is a place for you at the symposium. We’ve all stood at the edge of the flats, scanning the shimmering water and wondering what’s out there. A tailing permit, a cruising tarpon, a school of bonefish? The BTT Symposium carries that same sense of awe but, with it, a shared resolve to ensure these fish and their habitats are still there for generations to come.

To learn more or register for BTT’s 8th International Science Symposium, visit: BTT.org/symposium.

Chester Moore is an award-winning wildlife journalist and conservationist. He is host of the Higher Calling Wildlife® podcast and an outreach program by the same name that mentors teens with critical illness and traumatic loss on how to become wildlife conservationists. Learn more at highercalling.net.

Please

BTT reaches a 15-year milestone in The Bahamas, where it works to restore coastal habitats and conserve the flats fishery in collaboration with the government, local communities, fishing

guides, and partners.

BY T. EDWARD NICKENS

Fifteen years ago, no one knew what happened on full moon nights off the Bahamian reefs—that bonefish gathered by the thousands for an epic journey to deepwater spawning grounds. Fifteen years ago, few could have imagined the ecological benefits that would come from restoring natural flows to mangrove-lined tidal creeks choked by decades-old causeways and logging roads. And no one could have foreseen that a monstrous Category 5 hurricane named Dorian would roar across the Caribbean in September of 2019, and reshape the nation’s coastline, communities, and relationship to conservation.

Fifteen years ago, Bonefish & Tarpon Trust was an organization with its hands full in the Florida Keys, but its eyes on the horizon and a constellation of islands as close as 50 miles from Florida’s eastern shores. The Bahamas was home to a world-class flats fishery and provided a unique opportunity to research a healthy bonefish population untouched by the decline observed in the Florida Keys. BTT knew the answers that awaited in Bahamian waters held special promise to guide future restoration and conservation efforts in Florida and across the Caribbean.

Over time, BTT’s research went beyond filling knowledge gaps. It became “actionable science” that the Bahamian Government could use to conserve its flats fishery resources. Tracking data that identified bonefish home ranges, spawning areas, and the migratory pathways connecting them were used to advocate for greater habitat protection and effective management. Meanwhile, The Bahamas became the home for some of BTT’s earliest restoration projects targeting mangroves and creek systems. Today, the success of science-based conservation, and the growth in the support of fisheries management and habitat restoration anchored in hard data, have nourished a deepening relationship between BTT and The Bahamas. BTT today has three full-time staff members in The Bahamas, and its programs reach every stratum of Bahamian life, from education initiatives to policy development. Landmark discoveries from the location of pre-spawning aggregations of bonefish to new techniques for restoring mangrove habitats have enabled the organization to help Bahamians themselves reshape their national policies and their future.

And turn attention to other regions critical to the future of flats fisheries. What success stories await in the Mexican Yucatán, the Belizean coast, and even the waters of the Gulf and Southeastern coasts?

Thanks to the past 15 years in the Bahamas, that’s no longer hard to imagine.

Like most scientists, Dr. Aaron Adams, Director of Science and Conservation for Bonefish & Tarpon Trust, is loath to point to a eureka moment that suddenly crystallizes thinking on a complex matter or answers a Big Question like a laboratory slam dunk. The scientific process is just that—a layered system of query in which progress is often incremental and conclusions are more a matter of accretion than a lightning bolt from the sky.

But as Adams held on to the grab rail of a 22-foot hardbottom inflatable in the early morning of November 12, 2019, off the southern shore of Abaco, he couldn’t help but feel a growing sense of un-scientific thrill. On a small computer screen, a tiny

blinking green light showed the position of a 20.7-inch-long female Bahamas bonefish, caught four days earlier and surgically implanted with an acoustic tag. The fish was 65 meters deep, part of a large prespawning aggregation of bonefish. Then the glowing blips suddenly dove towards the bottom of the screen. He’d never seen that before.

Adams and a trio of other scientists—Dr. Steven Lombardo and Dr. Matthew Ajemian of Florida Atlantic University, and JoEllen Wilson, BTT’s Juvenile Tarpon Habitat Program Manager—had been on the water for nearly 24 hours following the PSA with a hydrophone dropped over the side of the boat and a detection computer. One by one, pings from the six tagged bonefish began to disappear, the fish likely eaten by sharks. With a full moon overhead and the eastern sky beginning to lighten, only one tagged bonefish remained.

At just after 6 a.m., that bonefish ascended from nearly 450 feet deep, held at about the 245-foot mark, oscillated for a minute while rising another 26 feet, and then the pings from the acoustic tag began to fall at a constant rate. Aaron and his

BTT is working with resource managers in Belize to conserve essential habitat for bonefish, tarpon, and permit. Photo: Jess

colleagues were bone-tired and bleary-eyed, but elated. The bonefish had ejected the tag with her payload of eggs. It was “the first detailed documentation of such deep spawning for a shallow-water coastal fish species,” according to the scientific paper announcing the finding. And it was the first time in history to document a spawning bonefish. Adams knew in his gut: This is groundbreaking. This changes things.

That full-moon night off Abaco six years ago was a pivotal moment for BTT. For starters, it underscored the importance of long-term studies and steadfast effort in building understanding about the biology of flats fishes. Fifteen years ago, very little was known about the biology of one of the most passionately sought gamefish on the planet. “There was a black hole of understanding about bonefish,” Adams says. And because so little was known about how bonefish made a living, management of the species and the habitats the fish require was next to impossible. “It would be similar to managing salmon,” he explains, “without knowing that they go out to sea for three years and then come back to spawn in the same areas where they were born. You wouldn’t know how to start.”

BTT focused its research efforts in The Bahamas as bonefish populations in the Florida Keys were struggling, and the Caribbean archipelago proved a rich field of inquiry. In 2011, BTT provided funding to the Cape Eleuthera Institute for acoustic tagging of bonefish in a study that revealed that bonefish tend to spawn at night during the full and new moons between October and May. “That was the first evidence we had that bonefish spawned offshore,” Adams says. “That was foundational.”

Two years later, BTT research began to home in on potential spawning sites through an approach that married hard science with the emerging field now known as Traditional Ecological Knowledge, or TEK. Extensive interviews with Bahamas fishing guides helped BTT identify potential pre-spawning and spawning locations, and narrow down the timing of bonefish migrations. A herculean effort commenced to dart-tag some 10,000 bonefish in The Bahamas, including on Abaco. Those tagging studies suggested that bonefish have a fairly small home range of about

a square mile, and they also revealed their spawning migrations. That work ultimately led BTT to identify 11 PSA sites in The Bahamas, and strengthened the organization’s relationships with collaborators such as the Bahamas National Trust, Friends of the Environment, The Nature Conservancy, and local fishing guides and lodges.

The big payoff came in September of 2015, when The Bahamas declared new parks or expanded existing parks on Grand Bahama and Abaco islands. On Grand Bahama, protections went into place at The Gap National Park and East Grand Bahama National Park. And on Abaco, bonefish habitats were protected at The Marls of Abaco National Park, Cross Harbour National Park, and East Abaco Creeks National Park. These new park declarations were part of The Bahamas’ larger commitment to protect 20 percent of the nation’s nearshore marine environment by the year 2020. They were followed soon after by the protection of additional bonefish habitats on Cat, Eleuthera, Inagua, Long Island, and in The Berry Islands. These extended the much earlier protection of the West Side National Park on Andros, which was created in 2002. Research by BTT scientists in 2006 and 2017 showed that the west side was important home range habitat to

bonefish, and that west side bonefish migrated to PSA sites on the east side, which provided important data supporting the Park designation.

“Our initial focus was on multiple and diverse aspects of the species and its habitats,” says McDuffie. “But there came a point during our research when we realized that the treasure trove of data being compiled from the tagging and tracking thousands of bonefish pointed to immediate conservation application.”

Today, those scientific endeavors are bearing a variety of fruits. BTT’s efforts in the archipelago nation are evolving increasingly towards habitat restoration and conservation. The success of The Bahamas program has fueled BTT’s burgeoning international efforts in Belize and Mexico’s Yucatán Peninsula. BTT has now been at work in The Bahamas for nearly 15 years, and the lessons learned there—in addition to the solid scientific findings—are only opening more doors for conservation.

On a sun-drenched day on the East End of Grand Bahama, I took a break to wipe sweat from my hands and look around. Dead mangroves cloaked the mud banks in a 360-degree view. It was a nearly apocalyptic scene, but the startling surroundings were lightened by peals of laughter and good-natured hollering ringing back and forth. Scattered through the dead brown stems of mangroves were groups of two and three and four young men and women, part of a high school biology class from Freeport’s Bishop Michael Eldon School. Half had dibbles in their hands—shovel-like implements used in tree-planting projects—while the others carried buckets and boxes of mangrove seedlings. In a single day, those

students and a team from BTT, Bahamas National Trust, Abaco’s Friends of the Environment, and the West Palm Beach apparel company MANG would plant 4,608 mangrove seedlings in the storm-ravaged flats along the East End.

To be sure, there was nothing good about the devastation wrought by Hurricane Dorian’s 185 miles-per-hour winds. BTT’s already robust presence in The Bahamas, however, and its nascent education program with local communities and schools, would prove to be a strong foundation for recovery. The storm, says Rashema Ingraham, BTT’s Caribbean Program Director, provided a crucible for Bahamians to forge a new relationship with the island’s ecology. “It allowed us to give a value to mangroves, and allow others to see that mangroves impact so many other aspects of our society,” she explains. “There’s now a deeper understanding that losing mangroves removes our culture and many of the socioeconomic benefits that we’ve relied on for many decades but had not recognized.”

BTT launched the Bahamas Mangrove Restoration Project in the wake of Hurricane Dorian, building upon BTT’s already extensive community engagement. Last December, the project reached the milestone of planting 100,000 mangroves along those shorelines of Grand Bahama and Abaco most affected by the storm.

Resting on laurels looks like this: With the project coming to a close, BTT and its partners in the Bahamas Mangrove Alliance (BMA) have committed to plant 1,000,000 more mangroves.

In other words, don’t put down those dibbles quite yet.

“Science gathers knowledge faster than society gathers wisdom,” wrote Isaac Asimov, and ensuring that its research is directed towards solutions and impacts has always been a core tenet of BTT. Building a foundation of quantitative data might have taken a solid decade, but while the organization’s efforts were focused and intentional, they were not single-minded. “That decade of scientific study allowed us to work with Bahamian communities and build a strong network of support,” figures Ingraham. Fishing guides and lodges, in particular, she says, have become “ambassadors for the protection of bonefish and mangrove habitats. They’ve become policy advocates in their own communities, because they now have the information and an understanding of scientific terminology to speak to administrators and local politicians. It’s very exciting to see.”

And such a growing chorus is critical to emerging BTT initiatives. With a quiver full of hard science and hard-won restoration successes, BTT and its collaborators are strengthening support for an audacious but reachable goal: A culture and effective working policy of no net loss of mangroves in The Bahamas.

The Bahamas has had a stated policy of “no loss of significant wetland habitat and no net loss for wetlands functions” on the books since 2007, but enforcement is spotty, and how well the policy works in practice is unclear. Over the last year and a half, BTT has been working on mangrove policy tools that will help identify where the country’s no-net-loss policy has been effective and where it has not. Such initiatives are only as effective as their enforcement and on-the-ground monitoring. “Our goal is to strengthen what’s already on the books,” explains Ingraham, “and make a stronger petition to the Bahamian government to pay attention to enforcement.” Over the next months, Ingraham and other BTT staff and supporters will be meeting with national and local Bahamas agencies and administrators to map out strategies for codifying mangrove and flats protection strategies.

Added to the mix will be ideas on how carbon offsets and wetlands mitigation tools can help ensure a greener infrastructure for The Bahamas.

“We can only have those kinds of conversations about the future because of our track record of connecting people to the environment,” Ingraham says. “The long process has ended up working beautifully.”

In fact, an expanded footprint—both geographically and in terms of on-the-ground impact—will mark BTT’s work across the Caribbean in the next decade. In that island nation, BTT is using its hard-won database of scientific studies to identify areas prime for restoration. “When BTT arrived in The Bahamas 15 years ago, our priority was on research to restore a fishery in Florida and to conserve one that spanned shallow-water environments across the region,” McDuffie explains. “The first application of our science was to support the protection of bonefish habitats in The Bahamas under declarations as national parks. We thought this would be the focus of our work for many years to come, but soon we began to understand the scale and impacts of blocked creek systems. We quickly tracked to a new set of restoration opportunities.”

With its growing network of relationships with NGOs, communities, and Bahamians built through mangrove restoration projects, and a clarity of evaluating habitat based on BTT’s entire suite of bonefish studies, identifying bonefish habitats ripe for restoration is a natural step. In the coming months, BTT will work with The Bahamas Ministry of Works to build upon a previous creek restoration project by removing two causeways on the East End of Grand Bahama that have stymied bonefish movements to flats for decades. One project will remove an old logging road that impedes water and fish movement at The Gap, and the second project will expand the previous logging road opening at August Creek. “This is our version of dam removal,” says McDuffie. “It improves water quality,

increases flow, and provides greater access to upstream habitat for multiple species. It’s a great example of how science-driven conservation can affect real change.”

In fact, the intersection of the biological and social sciences is now the launching point for much of BTT’s future efforts on a global scale. The habitat restoration, community education, and policy success in The Bahamas is informing BTT’s strategy across the Caribbean. In Mexico, BTT and Ducks Unlimited have recently begun working together on the northwest Yucatán Peninsula, while BTT is collaborating with two sister lodges, Casa Blanca and Casa Playa, to support studies of the flats fishery and habitats in the waters of the 1.3-million-acre Sian Ka’an International Biosphere Reserve. In Belize, BTT has launched a new permit acoustic tagging project whose protocols were pioneered in The Bahamas.

No matter the nation—Mexico, Belize, or in its own natal waters of the Florida Keys and along the Gulf Coast—BTT’s work is being built on symbiotic relationships. Just as The Bahamas has been the testing ground for much of what is now known about bonefish ecology, it has served as a proving ground for innovative ways to transform emerging scientific understanding into a significant foundation for conservation action.

None of this was written in the stars on that full moon night, long ago off Abaco’s Long Bay. Just as aha moments are a rare species in the landscape of scientific study, meaningful policy change and landscape conservation rarely occur without long-term effort. Perhaps that’s among the most important lessons learned across BTT’s 15 years of work in The Bahamas: Stay the course.

An award-winning author and journalist, T. Edward Nickens is editor-at-large of Field & Stream, a contributing editor for Garden & Gun, and the editor-in-chief of Tail Fly Fishing Magazine

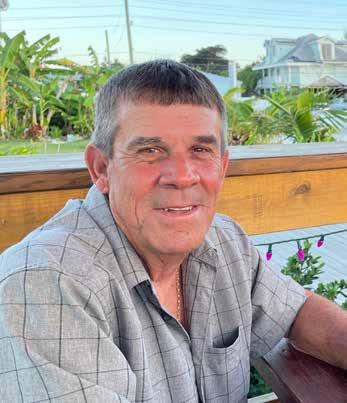

Bonefish & Tarpon Trust will honor Thorpe McKenzie with the Lefty Kreh Award for Lifetime Achievement in Conservation.

BY MONTE BURKE

According to his old friend, Carl Navarre, if one is to attempt to understand the life and times of Thorpe McKenzie, one must know this: “It all comes back to one thing: Thorpe is a serial enthusiast.”

A partial list of McKenzie’s enthusiasms over his seventy-seven years includes investing, Atlantic salmon angling, quail hunting, and music.

In more recent years, though, there is one enthusiasm that has reigned supreme above all others: fishing the shallow-water flats off the coast of Florida for tarpon and permit. In fact, as we shall see, McKenzie is surely among the most dedicated pursuers of those species on the globe. And along with that pursuit has come

a deep dedication to the conservation of those species and the environments they inhabit, a dedication that will be honored in October, when McKenzie will receive the Lefty Kreh Award for Lifetime Achievement in Conservation at Bonefish & Tarpon Trust’s 14th annual New York City dinner.

But it took McKenzie a few enthusiasms to get to this point. Herewith, a rundown:

McKenzie was born and raised in Lookout Mountain, Tennessee, outside of Chattanooga. His grandfather was an educator who started a college for women who otherwise didn’t

have the opportunity for that level of education. His father was the general manager of the Chattanooga Times. After his father died at a young age, McKenzie’s mother took a job in real estate.

After attending the Baylor School in Chattanooga, McKenzie went to the University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill and, later, the Wharton School of Business at the University of Pennsylvania. With an M.B.A in hand, McKenzie moved to New York and entered the training program at the brokerage firm, Kidder Peabody. While walking in the hallway one day he met Julian Robertson, a broker at the firm. The two men shared southern roots and accents, and undergraduate degrees from the University of North Carolina. “We hit it off,” says McKenzie. Shortly thereafter, McKenzie became Robertson’s assistant and then worked with him at Kidder Peabody for the remainder of the decade.

In the spring of 1980, Robertson approached McKenzie with an idea: why don’t we leave Kidder Peabody and start something on our own?

And with a reported $8 million—including $1.5 million that accounted for much of Robertson’s and all of McKenzie’s assets at the time—the duo founded Tiger Management, one of the world’s earliest hedge funds and one that would become, in short order, legendarily successful.

In 1982, McKenzie left Tiger, but stayed in the Northeast, managing his own money. In 1990, he left New York and returned to Chattanooga, founding Pointer Management, a fund of hedge funds.

During the majority of the beginning and middle eras of his working career, McKenzie was wholly consumed with investing— so much so, that he commandeered the dining room table in his Park Avenue apartment as a storage place for his booklets of investment studies. “They covered the entire table for ten,” says Navarre. “Two feet thick.”

At the time, McKenzie pined to fish and hunt—he had haunted the woods and waters near Lookout Mountain as a kid and told his friends that he wanted to someday fish and hunt two hundred days a year. But he could rarely find the time to do so. “I didn’t really take vacations back then,” McKenzie says.

And even when he did get out of the office, he didn’t really leave it behind. In 1976, McKenzie went to Islamorada to Cheeca Lodge. There, his old friend, Navarre—then working as a guide— took him out bonefishing one day up by Key Largo, McKenzie’s first time on the flats. “We got up on a flat and I started to pole and then Thorpe said, ‘Carl, I need to use a phone,’” says Navarre. “So, we ran ten minutes to some restaurant, and he went in and placed a trade on the phone.” They went back to fishing. But an hour later, McKenzie needed a phone again. “We didn’t really fish, but we did do a lot of running to find phones,” says Navarre.

ENTHUSIASM #2

Nearly a decade later, and with some time—finally—to take at least a little vacation, McKenzie traveled to Argentina with Navarre. There they fished for trout in that country’s great rivers— the Malleo, Collón Curá, Aluminé—and McKenzie “fell in love with it,” says Navarre. So much so that the next year, McKenzie went there for two months. In the years following, McKenzie studied Spanish, bought an Argentine ranch and invested in some local lodges. During this period of his life, he also fished for trout in the western United States, primarily in Montana.

ENTHUSIASM #3

In 1992, Navarre and McKenzie traveled to Russia to fish the Ponoi River for Atlantic salmon. (Navarre, if it isn’t clear yet, was an “enthusiasm enabler” for McKenzie.) The fishing

was phenomenal and, two years later, McKenzie put together a syndicate and purchased the Ponoi River Company—which essentially owned the river’s fishing rights—from Gary Loomis. McKenzie also became a part-owner of a camp on the upper Moisie River in Quebec and secured rods on Norway’s Alta and Scotland’s Tweed. “I also fished Iceland a bunch of times,” he says. In 1993, McKenzie caught a forty-eight-pound, fifteen-ounce Atlantic salmon on the Alta, which remains the IGFA world record for the fly-fishing twenty-pound tippet class (he was unaware it was the record until his assistant told him).

ENTHUSIASM #4

Then came quail hunting. McKenzie began hunting quail around Chattanooga as a teen. It wasn’t great there, but it was enough to light a passion that would eventually fully engulf him. Later on, as an adult, McKenzie began to hunt in Kansas and raise his own hunting dogs. He then hunted in Georgia and enjoyed it so much that he bought a plantation there and later added another one in Florida. He installed a sporting clays course at his home in Lookout Mountain and ardently worked on his shooting and eventually became, in Navarre’s words, “a terrific quail shot.” McKenzie also collected English shotguns and developed his own line of field trial dogs.

ENTHUSIASM #5

McKenzie grew up a fan of country music, Bluegrass, and the Blues. In his early teens, he learned how to play guitar

and banjo and became a member of a Bluegrass band. He continued to play into adulthood. In the living room of his Park Avenue apartment—amongst the antiques and tasteful English furniture—he had a complete band set-up, including guitars, a drum set, and amplifiers.

In the late 1990s, McKenzie put out a solo album under his own name and then formed the WTM Blues Band, for which he was the lead vocalist and guitarist. The band won a contest in its first public show.

McKenzie also owns what is considered to be one of the world’s finest collections of guitars, including ones once owned by Jimi Hendrix, Chuck Berry, and Roy Orbison.

“When Thorpe is passionate about something, there is no limit,” says Navarre.

But many of these enthusiasms have waned in recent years. McKenzie doesn’t fish for Atlantic salmon or trout much anymore, nor does he hunt as much as he used to. The reason for this waning, though, is abundantly clear. They have all made way for something else, an activity that is his most abiding and enduring enthusiasm—the fishing for, and conservation of, the species of the southern flats.

After that first trip to Islamorada with Navarre—and despite those frequent phone calls—McKenzie fell for the flats. In the years that followed, he spent the majority of his precious oneweek vacations in the Keys and fished primarily with the guides Mike Collins and Eddie Wightman. (He also had days with Cecil Keith, Hank Brown, Jimmie Albright, and Jack Brothers.) But work and his other pursuits limited him to just those few days a year.

That began to change in 1998, though. That year, McKenzie sent a scout down to the Big Bend area of Florida to look for tarpon-fishing opportunities. The scout found plenty of redfish but couldn’t get a bead on the tarpon. But he mentioned to McKenzie that there were two brothers who were guides not too far away from that area who seemed to have something going

on with tarpon. Those brothers: Tommy and Chris Robinson. So, McKenzie called and booked the Robinsons for three days of fishing near Apalachicola.

***

The Robinson brothers grew up for a time in Key West, and Tommy began his guiding career there. Then, for a while, Tommy became part of an outfit that flew anglers on floatplanes from Exuma to different bonefish spots in The Bahamas. When that job ended in 1995, he moved to Apalachicola where he and Chris— twelve years younger—began guiding. And the brothers soon discovered that the Panhandle area might have an untapped gold mine of a fishery. “We were just starting to understand that we had something going on with tarpon there,” Tommy says.

McKenzie came down to Apalachicola in March 1998 with some business associates. “I could tell it was a test, that he was feeling me out,” says Tommy. He and Chris took the anglers to Saint Joseph Bay. And while they caught many redfish, McKenzie kept asking about the tarpon fishery. “I told him to come back down in June,” says Tommy.

So, McKenzie did, this time accompanied by his then twelveyear-old daughter, Robin. On their first day on the water, they were greeted by a storm. “We were in St. Joe Bay hiding out,” says Tommy. “And when it finally cleared midday, I told them, ‘We need to make an hour drive to Lanark and fish the outside. There may be some tarpon there.’ We were taking a risk, but I thought it could be worth it.”

On their way east, they stopped in Apalachicola. There,

BTT honoree Thorpe McKenzie. Photo courtesy of Thorpe McKenzie.

Robin spotted an historic house in town that she had seen—and liked—the day before. The trio then continued on and launched near Lanark, motoring out to the Gulf of Mexico. “And there we ran into the biggest push you could imagine,” says Tommy. McKenzie hooked fifteen tarpon, landing five of them. “Thorpe would hook one and then hand the rod to Robin,” says Tommy. “It was fantastic.”

On the way back home through Apalachicola, Robin again mentioned the historic house to her father. Thorpe, still on a high from the day on the water, called the broker for the home and made what he believed to be a perfunctory lowball offer for it.

“Thorpe called me the next day and said, ‘I have a problem. The guy took my offer on the house and my wife has never seen the place,’” says Tommy. And that’s how McKenzie ended up with the Apalachicola home of a nineteenth-century timber baron and deepened his ties to the area.

McKenzie fished with Tommy and Chris for the next four years, gradually increasing his days on the water, from three, to five, to ten. In 2002, after selling the Ponoi River Company, McKenzie says he “began to get very serious” about tarpon fishing. “I was very lucky to get to Apalachicola right when Tommy and Chris were figuring it all out,” he says. “They were inventive and doing their own thing, and we had some fabulous summers down there.”

By 2007, McKenzie was fishing for nearly thirty days a season with the Robinsons. That year, Tommy suggested they go to Key West, his old home water, and try for permit. McKenzie was game, and on his first trip, on a flat west of town, he landed his

first permit and unlocked a new enthusiasm. “They are just so intriguing because it’s so hard to get them to eat,” says McKenzie. “There’s no room for error. You have to do everything right and drop it right in front of their face. A Mexican guide once told me that with permit, you don’t give the fish time to wonder about it.”

McKenzie’s fishing ramped up even more after he retired in 2015. In recent years, he has booked close to 230 days with the Robinsons. (McKenzie fishes about thirty days with Chris and the rest with Tommy.) “Not all of those days are on the water. We have travel days and weathered out ones,” he’s quick to add. “But I really am the luckiest guy in the world when it comes to fishing.”

“Thorpe would never talk about it, but he has caught an incredible number of tarpon and permit,” says one of McKenzie’s fishing partners, Dr. Ed Hall.

McKenzie has certainly had some epic days on the water. In 2008, he landed a nearly thirty-five-inch permit with Tommy. “It had the frame of a forty-pounder, but was a declining fish,” says Tommy. McKenzie once caught three permit off of one flat within an hour with Chris. That duo also a landed a twelve-pound mutton snapper that tried to escape by running into two different abandoned lobster traps. “That mutton was about as big as you can possibly land on a fly in shallow water,” says Chris.

One day McKenzie was fishing with Hall when Hall—then on the bow—asked McKenzie to hold the rod as he moved to the stern to relieve himself. McKenzie did, and spotted a permit, cast to it, and landed it. Robinson took a photo of the two men with the fish and posted it on Instagram, complete with an explanation for why Hall’s zipper was down.

McKenzie often brings his children along on a day of fishing. (He owns a forty-five-foot offshore boat so that more members of the family can come to try for dolphin, grouper, and sailfish.)

McKenzie took two of his sons on their first flats trips when they were eleven and seven years old. “The younger one was too small to cast over the cage on the casting platform,” says Robinson. “They are now in their twenties, and it’s sick how good they are.”

Tommy says McKenzie is generous (he once paid for a subsistence fisherman’s trailer after it was submerged at the dock) and down-to-earth (for years, McKenzie asked for bologna and cheese sandwiches for lunch—until his doctor told him he had to quit eating them). “Thorpe is very serious about fishing but he’s also out there to enjoy himself and have fun,” says Tommy. “He never complains about the weather or the fishing. He always has a smile on his face. We have a great time.”

Says brother Chris: “We’re all like family.”

And McKenzie still can’t get enough of it. “The scenario that keeps me coming back to the flats is the long, quiet wait in the grandest of natural settings followed by the absolute panic as you, or more often your guide, spot a tailing twenty-five-pound permit digging up the flat ahead,” he says. “The attraction for me of fly-fishing for tarpon, bonefish and permit on the flats is mainly that it’s hard. The heart-pounding, knee-knocking excitement in the presence of these game fish is quite a pleasurable addiction.”

Which is one of the reasons why, he says, he decided to fight for the well-being of those species and their habitat.

McKenzie’s philanthropy has been guided by his enthusiasms and heritage. Like his grandfather, McKenzie became interested in the education of those without access to it. So, in 2004, he founded the McKenzie Foundation to help provide those opportunities. Three years later, he started the Songbirds

Foundation, which supplies guitars and playing lessons to underprivileged children.

During his Atlantic salmon-fishing phase, McKenzie was an active board member of the Atlantic Salmon Federation (ASF) and did conservation work on the Ponoi that was particularly impactful. Soon after he purchased the rights to the river, McKenzie negotiated with the Russians to remove the commercial nets. And a few years later, McKenzie brought together the ASF, the National Fish and Wildlife Foundation, and Frontiers to do a comprehensive study on catch-and-release fishing. (The Ponoi, with its huge and healthy runs of Atlantic salmon, was the perfect river for such a thing.) Under the leadership of Fred Whoriskey, then head of science at the ASF, the group conducted a years-long tagging study on thousands of fish. “At that point, the Norwegians, Icelanders, and even some Canadians argued that catch-and-release didn’t work, that the fish died or couldn’t spawn,” says McKenzie. “That was their justification for killing them all.”

But the study proved the opposite: close to one hundred percent of the fish lived after release and had no trouble spawning. That study, for all intents and purposes, gave the push needed to make catch-and-release the prominent mode of angling for Atlantic salmon, a drastic change in that sport. “It was an incredibly important study, not only for the Ponoi’s salmon but Atlantic salmon populations everywhere,” says Bill Taylor, the former president of ASF. “And Thorpe wasn’t just part of it. He was the driving force behind it.”

“The husbandry of the Ponoi is the thing I’m most proud of in terms of conservation,” says McKenzie.

During his quail-hunting phase, McKenzie was an early supporter of Tall Timbers Conservation Easement Program, which protected private land for native bobwhite quail. He remains the program’s largest single donor of conservation easement acres.

And, of course, there is his support for the species of the southern saltwater flats. McKenzie started with the fishing guides. In the early 1980s, McKenzie fished the Don Hawley tarpon tournament in Islamorada, and then became a director of the Don Hawley Foundation, which raised money to help out guides who had fallen on hard times. While a director of the foundation, McKenzie supported critical research—done by Dr. Roy Crabtree— on the spawning habits of tarpon.

In 2017, Navarre—who had just joined the board of BTT and now serves as its chairman—needed help funding a bonefish research project. He reached out to his old friend. “Thorpe was extremely generous and helped to have the project entirely funded within two weeks,” says Navarre. Shortly thereafter, McKenzie joined Navarre on the board of BTT, a position he maintains to this day.

BTT has been a good investment, McKenzie says, which, in some way, has brought his life of enthusiasms back full circle. “BTT was attractive because of the science,” he says. “The things we’ve done, like finding bonefish spawning sites, is attractive to me and vitally important. The efforts we’ve put in for these three species benefit everything, from other species on the flats to cleaner water and more mangroves. It’s all additive to the environment.”

And thanks to the work of BTT, McKenzie says, he sees a bright future for bonefish, tarpon, and permit. “I’m as optimistic about these species as I’ve ever been.”

Monte Burke is The New York Times bestselling author of Lords of the Fly, Saban, 4th And Goal and Sowbelly. His latest book, Rivers Always Reach the Sea, is available now. He is a contributing editor at Forbes and Garden & Gun.

From The New York Times bestselling author of Saban and Lords of the Fly comes an exquisite collection of angling stories that span the twenty-first century.

“Monte Burke’s extraordinarily detailed portraits and nice, clean prose turn his stories into literature. I’m a big fan.”

THOMAS McGUANE, author of The Longest Silence

“I cannot recommend this book enough—the writing is breathtaking. Monte Burke has written a masterpiece.”

WRIGHT THOMPSON, ESPN senior writer and author of Pappyland and The Barn, on Lords of the Fly

Available wherever books and ebooks are sold

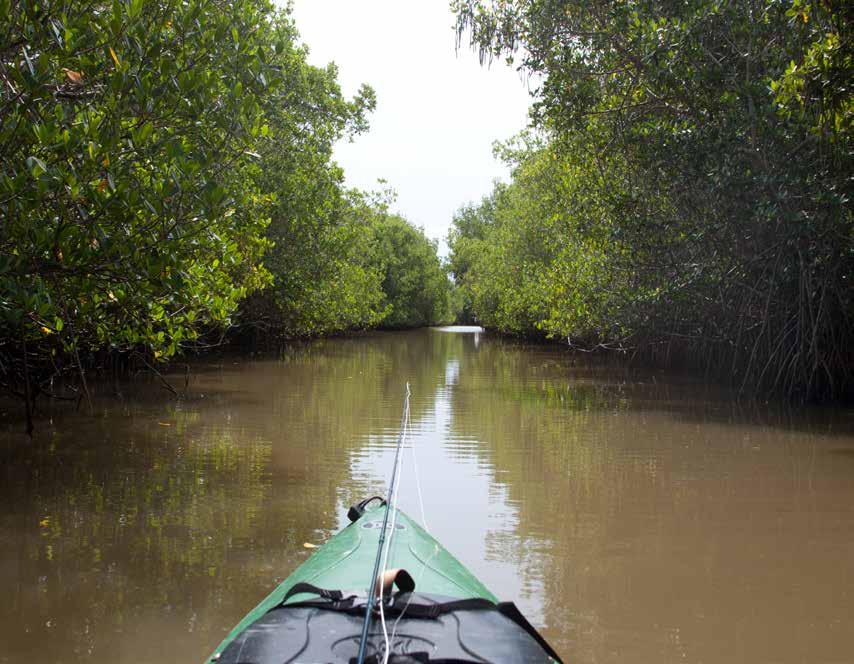

Belize is protecting 5% more of its marine areas in the next five years. Here’s how BTT is helping to ensure these protections apply to some of the world’s richest bonefish, tarpon, and permit habitats.

BY ALEXANDRA MARVAR

On a hot spring day in 2024, 13 miles out at sea, a group of some 70 men, women, and children stood in a circle at Belize’s legendary Will Bauer Flats off the coast of Placencia, Belize. Ankle-deep in the cerulean water, with a haphazard fleet of cabin cruisers and flat-bottom skiffs moored and bobbing around them, they planted Belize’s flag in the sand, and they sang the national anthem.

Placencia’s fly-fishing community had been fighting for more than a year to stop a developer from digging up this seabed around Angelfish Caye to build a massive resort, complete with overwater villas. At the start of May, the community got word that a ban on dredging had been lifted. Guides rely on these flats, as their families have for generations. One younger guide Damion Nasario, who got his start guiding under Lincoln Westby, lamented its possible demise in a news broadcast: “This is the first flat—and only flat—where I’ve seen permit and bonefish still in together.” The group’s patriotic display of strength was a message to developers, and to the government—and Eworth Garbutt, head of the Belize Flats Fishery Association (BFFA), put it

into words before the crowd: They had no plans to back down.

“A developer would look at a flat—literally a permit flat—and see a building over water. A guide will look at the flat and see his future,” says Eworth’s brother Dennis Garbutt, a member of the BFFA and the owner of Garbutt’s Fishing Lodge down in Punta Gorda. “And the authority will look at it and decide who gets a permit [...] to develop or not to develop. But it should be clear cut: If it’s a sensitive area, it should be put aside for the purpose of protection.”

This Central American country, which is partially located on the Yucatán Peninsula, is approximately the size of Massachusetts, with a population about the size of Tulsa, Oklahoma. Travelers know it by its puddle-jumper planes buzzing along the coastline, its vast rainforests scattered with Mayan ruins and roving jaguars, and its labyrinthine waterways through mangrove forests that offer the chance for a grand slam, or even a super slam: hooking a bonefish, tarpon, permit, and snook all in one day. Along its coast lies the largest barrier reef in the Western Hemisphere: the 1,000-kilometerlong, UNESCO-protected Mesoamerican Reef, a natural buffer

against storm surges that shores up magnificent amounts of “blue carbon” in its mangrove, seagrass bed, and coastal wetland ecosystems. But mounting pressures—coastal development, increased tourism, climate change—threaten to throw its delicate system off balance. And that means battle after battle for people whose livelihoods—and lives—are tied to the water.

In the case of Will Bauer Flats, the fly-fishing community emerged victorious. In October of last year, the government acquired Angelfish Caye from the owner and put it into conservation. “It was about to be dredged, and we stopped it,” Dennis Garbutt says. “We came in and we made a hell of a show.”

But, he says, there’s a lot more work to be done.

Guides in San Pedro, on Ambergris Caye, are embroiled in another fierce debate: There, a different developer is pushing to build another sprawling resort on an island called Cayo Rosario, and again, the plans include dozens of overwater villas that would decimate a protected marine area and flats fishing destination. Anglers have been fighting the proposal for nearly a decade, but it keeps inching forward.

“There’s ongoing issues at Cayo Rosario, as to whether construction activities are actually operating as they were permitted or operating outside of their permitting process,” says BTT VP for Conservation and Public Policy Kellie Ralston. “There’s real concerns with dredging activities that are ongoing, and lack of enforcement and oversight throughout that process.”

While Will Bauer Flats and Cayo Rosario are just tiny specks in the big, wide ocean, BTT’s Director of Science and Conservation Dr. Aaron Adams says science underscores just how much these places matter, on a regional and international scale.

“When bonefish, permit, and tarpon spawn, they do what’s called broadcast spawning, off the reef or in deep water,” Adams says. “The larvae are carried around by the ocean currents. Some of those larvae can get carried from points south, including Belize, to the Florida Keys.”

BTT’s multi-year Bonefish Genetics Study—which involved

guides and partners across Belize and eight other countries working together to collect upwards of 13,000 samples—proved just that. The study laid out the evidence for how populations across the Caribbean are all connected.

“And, we know that bonefish migrate from Mexico into Belize to a spawning location,” Adams adds. “We suspect that some permit do the same, so that’s another international connection.”

In fact, in 2023, a permit measuring nearly 27 inches was harvested by spearfishers in Mahahual, Mexico. Just weeks earlier, a coalition of partners in Belize, including BTT Belize–Mexico Program Director of Science Dr. Addiel Perez, had tagged that very fish…right near Cayo Rosario.

Perez joined BTT in 2019 to conduct flats fisheries science in Belize and neighboring Mexico. He, along with program coordinator Lysandra Chan, is providing the research results that inform the organization’s conservation action and policy recommendations.

“I grew up in a small fishing community in northern Belize. I used to go fishing with my dad since I was maybe eight or nine, during summertime. There, I learned the hardships of fishing,” Perez says. He decided even back then: “When I grow up, I want to do something for these fishers—for these communities—and contribute to something. So, that’s why I’m here now, contributing to science, protection of ecosystems, and supporting livelihoods that depend on these ecosystems.”

Perez and Chan are also building networks, working with partners, including local associations, lodges, and other business owners, on outreach and education efforts. “It’s very important for stakeholders in these two countries to identify someone that understands them, someone who speaks their language—not just

English or Spanish, but their dialects or cultures. With that, they feel more comfortable communicating, participating in, supporting BTT. I think that has helped me a lot,” he says.

Dr. Michael Steinberg at the University of Alabama is a geographer who specializes in spatial mapping. He’s worked with BTT to map habitats, from the high boat-traffic areas in the Everglades to post-Hurricane Dorian mangroves in The Bahamas. But throughout his career, Belize has been a constant.

“It’s a small country, but it’s got all these protected areas,” Steinberg points out. “It struggles like any developing country in terms of implementing sustainable conservation policies, but they’ve done a better job than most countries, and they have more territory included in some form of management protection than most countries.”

A quarter-century ago, the government entered into a landmark conservation deal to protect 23,000 acres of rainforest in the Maya Mountain Marine Corridor. About a decade later, it was among the first countries in the region to enact a law making bonefish, tarpon, and permit catch-and-release. Then, in 2021, Belize made global headlines with a groundbreaking deal: In a partnership with the Nature Conservancy, Belize entered into the world’s largest debt-for-nature “Blue Bond” deal, restructuring $364 million in national debt in exchange for a pledge to expand protections to encompass 30 percent of its ocean territory by 2030 and to make an $180 million-investment in marine conservation. As of now, Belize’s Coastal Zone Management Authority & Institute (CZMAI) says the nation has some 25 percent of marine areas in protection and just five percent to go to hit their 2030 benchmark—but it’s complicated. And conservationists say some of those protection parameters leave much to be desired.

According to Adams, scientists and conservationists are concerned that, despite the high-profile Blue Bond deal, Belize’s conservation efforts are backsliding, with increased coastal development and increased dredging, and diminishing enforcement, including on catch-and-release protections for fragile flats fisheries. The COVID pandemic was a difficult time everywhere, but in Belize, it also brought severe enforcement gaps, and research indicates that along Belize’s stretch of the reef, fish biomass plummeted.

Steinberg has spent decades talking to guides and visiting Belize for habitat mapping work, and he’s seen a lot of changes, especially in Ambergris Caye, which he says is virtually “unrecognizable” as compared to his first visit there some 30 years ago.

“They’ve done a lot of really good things in terms of national conservation, but again, like any country”—particularly a less-resourced country, Steinberg says—“they struggle with enforcement and all these other things.”

Now, Steinberg is working with BTT on a massive, detailed spatial mapping effort of all Belize’s flats fish habitats. He hopes this information will help the government of Belize understand where new marine protection areas should be established—and where more resources could be put into enforcing existing protections.

In October 2023, BTT and partners within the government of Belize took their collaboration to the next level with a Memorandum of Understanding between BTT and Belize’s Coastal Zone Management Authority & Institute. In this memorandum, the parties formalized their partnership and outlined plans for

collaboration on research, continued fish tagging, water quality monitoring, and public outreach, including a best-practices guide for sportfishers. BTT is also helping to strengthen CZMAI’s capacity in areas like habitat health, fish genetics, and marine spatial planning.

CZMAI’s Sport Fishing Coordinator Victor Sho explains just how pivotal this partnership is: “The biggest thing, especially for a country like Belize, is there’s not a lot of funding to do in-depth research,” says Sho, whose office oversees all Belize’s fisheries, from pelagic and reef species to the flats. “There’s not a lot of existing literature on where the species spawn, where they aggregate in Belize, the migratory corridors that they use....”

Particularly as Belize works toward its 2030 Blue Bond commitment, reliable data and a deep understanding of marine habitats is invaluable. Sho says the CZMAI is working with partners including BTT, the Environmental Defense Fund, and NOAA to help fill this research void.

In 2016, Sho’s role was created and a more fine-tuned plan began to come into play for how pre-existing regulations would be managed and enforced. “The original regulations that were passed in 2010 weren’t as effective as the stakeholders or decision-makers wanted them to be,” he says. “So, right now we’re working on revising those regulations. November of this year is when we should have new sportfishing regulations for

the country, to fill a lot of the gaps [...] but also to make the regulations more practical and forward-thinking.”

This regulatory overhaul is one place where reliable habitat mapping is critically needed—and now, Sho has results from Steinberg’s recent spatial habitat mapping work on hand. “The information that Bonefish & Tarpon Trust is helping us get— identifying these nursery habitats and these pre-spawning sites— those are prime candidates to first consider extending protection to,” Sho says.

Putting new marine areas into conservation serves multiple goals, Sho says. “It protects the environment, allows Belize to live up to its agreement with the Nature Conservancy, and it protects the livelihood of these communities,” he says, “so there is a lot to gain and very little to lose by protecting these locations—granted we get the right information at the right time so that we can make the best possible choices.”

From community-driven wins to new partnerships, there’s momentum in Belize—and for Dennis Garbutt, that’s exactly why the work needs to keep evolving.

“I am happy to see the NGOs around the fisheries department doing their part in terms of protecting and enforcing and educating people about these marine reserves,” Garbutt says. “I say all that because I believe that that helped. Without the marine reserves, we wouldn’t have our vibrant fly-fishing industry”—an industry that brings approximately $120 million USD annually to the Belizean economy. “Seasonal protections, the ban on gill nets, these marine reserves, and the different no-take areas—it has helped a lot in terms of protecting the permit, tarpon, snook, bonefish…. At the same time, this is a dynamic world, and we’ve got to grow with the times, too.”

In addition to the forthcoming November sportfishing regulations update, Sho at CZMAI is working to tackle today’s concerns from multiple angles: In partnership with UK organization the Ocean Country Partnership Programme, the agency recently rolled out standardized data collection protocols across the marine reserve network, helping to plug spatial data gaps and inform Blue Bond commitments. Belize is also visibly ramping up enforcement, trialing the use of drones for monitoring in reserves including Glover’s Reef and Turneffe Atoll—and this is starting to yield results. In the first quarter of this year, Turneffe rangers reported 10 infractions, including illegal development, undersized catches, and unlicensed fishing in restricted zones.

Meanwhile, Perez and Chan are seeing tangible evidence of their impact on the ground. Beyond playing a role in massive victories like the win at Will Bauer Flats, Perez is increasingly fielding calls from local teachers, requesting he present to students in the classroom about the flats fishery ecosystem, or from fisheries departments, for help investigating reports of invasive species. “They’re seeing us, and they’re reaching out to us—those are indicators that we’re getting” that the work is resonating.

Up in San Pedro, the fight for Rosario Caye goes on. One timely project out of the Belize-Mexico Program office: Perez conducted an independent environmental impact assessment (EIA) of Cayo Rosario—and came away with very different findings than the government-contracted assessor had. “The government has actually really good processes in place” for EIAs, Ralston notes, “but there are a lot of loopholes.”

She adds, “We’re continuing to work with a coalition of folks in Belize to raise awareness of the issue and hopefully have some government intervention in the future.”