Nature must be protected but is also a powerful tool that can be used to improve water quality and control flooding, as we strive for sustainable solutions, writes Minister of State with responsibility for Nature, Heritage and Electoral Reform, Malcolm Noonan TD.

Maintaining good water quality is vital for the wellbeing of our society, economy, and environment. Our water bodies are not only essential parts of our natural environment, but they are also a national asset that provides our drinking water, nourishes the land and contributes to a sense of wellbeing, whether we are swimming, boating, fishing, or just walking alongside them. The protection and restoration of our waters is a national priority.

Globally, water quality is under threat and there is a considerable challenge ahead to ensure the sustainable use and management of our finite water resources. Even in Ireland, where our water quality is comparatively good and water is relatively abundant, our natural water systems are at substantial risk from increasing nutrient pollution, physical modifications, and urban pollution. This is all happening while our water systems are becoming more vulnerable due to changing weather patterns.

One of the key principles of the new Water Action Plan is to deliver integrated policy objectives for water, biodiversity and climate wherever possible. The plan, which will be officially launched on 5 September 2024, promotes the use of nature-based solutions, both in rural and urban settings.

Not only can nature-based solutions provide attractive features and focal points within the landscape, they can also provide significant ecological value. Designed to manage rainwater, they slow and store runoff and allow it to soak into the ground. Their benefits are wideranging, filtering out pollutants that would otherwise end up in our waters, reducing flooding and easing the burden on combined sewer systems.

These climate-adaptive solutions provide other benefits in terms of urban greening, which can help to mitigate higher urban temperatures. They also contribute towards a more pleasant urban environment that can prioritise

pedestrians, cyclists, and other sustainable travel modes.

In an urban setting, pressures on water quality primarily result from direct surface water discharges and storm water overflows from combined sewers. However, sewer leakage, misconnections to storm drainage along with runoff from paved and un-paved areas area also puts pressure on water quality. In turn, this negatively affects water quality in the natural environment, including bathing water quality.

As urban development continues, surface water runoff from impermeable surfaces increases. This is further exacerbated by climate change as the frequency of intense rainfall events also increases.

Recent research, based on an analysis of European flooding records from 1960 to 2010, suggests that increasing autumn and winter rainfall has already resulted in increasing floods in northwest Europe, including Ireland. We need to change our planning and design philosophy to ensure we consider making space for water by incorporating integrated catchment management principles and water-sensitive urban design.

Nature-based solutions are designed to address rainfall in urban or paved areas in a manner as close as possible to the

“We must seize every opportunity to harness the power of our natural environment as we seek sustainable pathways to improve our water quality.”

Minister of State with responsibility for Nature, Heritage and Electoral Reform, Malcolm Noonan TD

natural environment. This is achieved by replacing paved or impermeable areas with permeable nature-based surfaces, such as urban rain gardens, permeable paving in parking areas, swales and retention basins. These areas can provide volumetric storage within a catchment in existing or new green areas, which allows both infiltration to groundwater and attenuation of surface water runoff. Nature-based solutions should be located by determining where the surface water flows and then planning drainage routes and solutions along that path to capture overland flow and minimise flood damage.

There is also a benefit to integrating nature-based solutions in a rural setting. A recent ‘Farming for Water’ European Innovation Partnership project aims to support up to 15,000 farmers in implementing on-farm water protection measures. Led by the Local Authority Water Programme (LAWPRO), and in partnership with Teagasc and Dairy Industries Ireland, it focuses on reducing losses of nutrients, sediment, and pesticides to water bodies from agricultural lands. In turn it promotes the adoption of innovative best practice in nutrient management, the application of nature-based solutions and other suitable measures.

To encourage better understanding and adoption of new approaches Government departments have published several guidance documents relating to the application of naturebased solutions, including:

• Nature-based Solutions to the Management of Rainwater and Surface Water Runoff in Urban Areas, November 2021;

• Design Manual for Urban Roads and Streets: Advice Note 5, Road and Street Drainage using Nature-based Solutions, August 2023;

• Greening and Nature-based SuDS for Active Travel Schemes, September 2023;

• Nature Based Management of Urban

Rainwater and Urban Surface Water Discharges: A National Strategy, May 2024; and

• Rainwater Management Plans: Guidance for Local Authorities, May 2024.

In addition, pilot demonstrator projects have been funded by the Department of Housing, Local Government and Heritage in Cobh, County Cork and Dublin city, which will help to guide the wider use of nature-based solutions by demonstrating their efficacy in an Irish context.

In June 2024, President Michael D Higgins signed the Future Ireland and Infrastructure, Climate and Nature Fund Bill into law. The newly established Infrastructure, Climate and Nature Fund is expected to be a significant source of funding for projects looking to address specific climate, nature and water objectives, such as the use of naturebased solutions. Of the total of €14 billion, €3.15 billion is available for climate, nature, and water protection spending between 2026 and 2030.

I feel strongly that, as a country, we must seize every opportunity to harness the power of our natural environment as we seek sustainable pathways to improve our water quality. It is essential that we protect and restore our waters to preserve our natural heritage for future generations.

As CEO of Uisce Éireann, I welcome the opportunity to reflect on what has been a year of momentous change and growth for Ireland’s public water services as we seek to rise to the challenge of delivering transformative water services that enable communities to thrive, writes Niall Gleeson.

Just over a decade since Uisce Éireann (then Irish Water) was set up, we have made enormous progress in the transformation and delivery of safe, secure and sustainable water services in Ireland.

However, we are still dealing with the legacy of decades of under-investment in Ireland’s water services. Much of our asset base, comprising over 90,000 km of pipes network and over 1,700 water and wastewater treatment plants, is ageing and in need of upgrade. Public water services underpin all the basic needs of an open, thriving and globally

competitive society and there is much more for us to do. To modernise our water infrastructure it is essential that funding is provided on an ongoing and consistent basis to enable us to meet this challenge.

The current investment cycle (20202024) has seen €5.26 billion invested in these critical services, benefiting communities across Ireland by putting in place systems and structures to improve the delivery, monitoring and testing of drinking water and wastewater services, ensure compliance with Irish and European standards, and support

Ireland’s growth and development, including housing delivery.

In 2023, our connections team issued over 4,500 connection offers associated with 42,970 housing units. Works to eliminate raw sewage discharges were completed across 10 sites, bringing to 40 the number of locations around the country where new infrastructure is in place or under construction to end the discharge of raw sewage. And we continued to improve the quality of public drinking water supplies, achieving 99.7 per cent compliance with EPA standards.

In the past year, we have also assumed full responsibility for public water services from 31 local authorities, and we are working towards the transfer of all water services staff to Uisce Éireann. We want and need as many local authority staff as possible to join us, integrating their local knowledge, expertise and dedication to water services to support us building a truly national organisation.

Uisce Éireann has a critical role in meeting the State’s environmental, growth, and development needs. It is essential that key enabling infrastructure like water services are appropriately funded. Multiannual funding is crucial to providing certainty in the provision of water and wastewater infrastructure across Ireland. On average our projects can take between five to 10 years from design to completion. Greater certainty provides stability in the delivery of our strategies, plans and programmes. We require multiple cycles of funding to bring our water infrastructure to where we need it to be; and then continuous funding to ensure quality and capacity can keep pace with demand. Without the necessary public water and wastewater infrastructure, there can be no wider economic or housing growth.

Similar to other organisations and globally, Uisce Éireann has also been impacted by higher inflation which does necessitate an increase in funding to reflect increasing costs across the construction sector. In addition, additional water services activities, such as the increased drinking water and wastewater quality standards from new EU Water Framework Directives, will require further increases in funding.

This further highlights the need for sustained ongoing investment for many decades to offset legacy underinvestment in water services. In the absence of growing investment there will be real risks to service delivery and Ireland’s ability to meet its economic, social and environmental obligations.

This year, we achieved an important milestone with the Government approving in principle our plan to develop a new water supply for the entire Eastern and Midlands Region. By

There is currently no spare capacity in the Greater Dublin area, presenting a very real risk of water supply shortages in the coming years.

2044 we will need 34 per cent more water in the region than we have today. There is currently no spare capacity in the Greater Dublin area, presenting a very real risk of water supply shortages in the coming years. Ultimately if this deficit is not addressed, it will further constrain our ability to attract investment and meet the demand for housing.

By creating a new water supply ‘spine’ across the country with the capacity to support communities from Tipperary to Dublin and Carlow to Drogheda, the Water Supply Project, Eastern and Midlands Region will be critical to meeting that need, ultimately benefiting half the population of Ireland.

Ongoing support for this project and other key strategic infrastructure, such as the Greater Dublin Drainage Project, will be essential to ensure we can achieve the widest benefit for the greatest number of people and deliver the most environmentally, technically and economically beneficial solutions to meeting Ireland’s long-term water services needs.

Finally, I would like to take this opportunity to welcome the new Chairperson of the Uisce Éireann Board,

Jerry Grant, and new Board Director Paul Reid. They both bring a wealth of knowledge and experience across a range of sectors, including large infrastructure delivery, public health and strategic leadership. I would also like to extend my thanks to our departing Chairperson Tony Keohane and Board member Fred Barry for their enormous contribution.

I look forward to continuing our successful collaboration with all our stakeholders as we work towards achieving our vision of a sustainable Ireland where water is respected and protected, for the planet and all the lives it supports.

W: www.water.ie

The Water Action Plan (WAP) – a revamp of the River Basin Management Plan – is calling for a change in approaches to flood management with the aim of reducing pollution in rivers and lakes.

The nature of the proposed changes under the WAP come in the form of reform of the Arterial Drainage Act 1945, with proposed revisions designed to “change the approach to flood management” in line with the State’s legal obligations under the Water Framework Directive.

The Water Framework Directive mandates EU member states to establish river basin management plans. However, the WAP, while incorporating the Directive’s broad objective of reducing pollution in EU river bodies, represents a departure from the established approach.

While Ireland has previously published strategies and plans under the framework of a river basin management plan, the last River Basin Management Plan 2018-2021 resulted in a decline in water quality in 428 of the 726 water bodies for which improvement was an objective, according to the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA).

Following this broad decline in water quality, the WAP establishes a new objective of 300 of the State’s waterbodies to reach “good” status or better by 2027, and for an end to further deterioration of water quality in the State’s water bodies.

“It is a hard won Green measure and I am proud that [the] Government has supported its inclusion in the new water action plan.”

Minister of State at the Department of Housing, Local Government and Heritage for with responsibility for Nature, Heritage and Electoral Reform, Malcolm Noonan TD, on the reform of the Arterial Drainage Act 1945

The WAP objectives on flooding reform are that rivers should be able to flow in a natural cycle without artificial interference, with the objective of restoring natural ecosystems and enabling water infrastructure with increased investment, most notably wastewater treatment facilities. Funding is set to continue at current scales, with funding for Uisce Éireann coming to over €2.3 billion since 2020.

The new EU Nature Restoration Law allows for “the lateral flow of rivers” i.e. restoration of natural flood plains, as a key enabler of restoring climate resilience through restoration of natural ecosystems.

Ireland is experiencing a sustained decline in water quality, with half of the State’s rivers, one-third of lakes, and two-thirds of transitional waters classified as having ‘moderate’, ‘poor’, or ‘bad’ status.

The WAP includes removal of river-blocks preventing salmon and lamprey swimming upstream to spawn. These proposed changes are to be backed by new governance structures involving farmers, communities, NGOs, and industry.

The agricultural sustainability support and advice programme, known as ASSAP, and local authority-level water programme (LAWPRO) is

to be extended, and the EPA will publish an annual progress report on enhancing water status. Local authorities are to get more than 60 new enforcement staff to conduct 4,500 farm inspections annually.

On nitrates, it will include tighter controls on the timing and methods of fertiliser application and reduce amounts that can be spread on grassland. There will be a requirement to reduce “the maximum derogation stocking rate on farms where water quality is at risk” – ie curb livestock numbers.

Minister of State at the Department of Housing, Local Government and Heritage for with responsibility for Nature, Heritage and Electoral Reform Malcolm Noonan TD commented on the reform of the Arterial Drainage Act 1945: “We are serious about tackling flooding, restoring nature and improving water quality, that is why it is so important to review this out-of-date legislation and make it fit for the 21st century.

“It is a hard won Green measure and I am proud that [the] Government has supported its inclusion in the new water action plan.”

With water scarcity becoming an increasing problem on every continent, achieving Goal 6 of the UN sustainability development goals (SDGs) to ensure availability and sustainable management of water and sanitation for all is becoming increasingly critical, write Neil Delaney, Head of Strategic Water Programmes and Jillian Bolton, Regional Lead Water Ireland with Jacobs.

Public consumers expect that water will be available for their use while water utilities demonstrate improvements to our environment through sustainable abstractions combined with responsible treatment and release. To achieve SDG 6, the water sector must continue to meet these expectations while managing the increasing challenges and pressures on global water resources from population growth, economic development, and climate change.

The global water supply crisis is well documented, with media reporting shortages globally. Shortages in Cape Town, South Africa have been widely reported, however less widely reported shortages include southwestern USA where the Colorado River no longer discharges to the sea due to over abstraction and use.

Globally, water stress levels are predicted, up to 2050, by the World Resources Institute at a national level,

with ‘extremely high’ stress levels in areas of North and South Africa and parts of Asia, while Australia is tracking slightly more favourably with ‘high’ stress levels expected. Conversely, northern European countries predominantly track as having ‘low’ or ‘low to medium’ water stress levels in the same timeframe.

While the global view appears to demonstrate a positive national picture for countries such as Ireland and the United Kingdom, within each jurisdiction regional challenges are already arising driven by climate changes to weather patterns and increased population in focused areas. The 2018 drought in Ireland resulted in water supply restrictions in targeted locations due inpart to limitations on the connectivity of our water supplies.

Overreliance on a given water source can lead to challenges and ultimately limitations due to environmental impacts as the source is needed to supply a growing population or commercial use, be that industry or agriculture.

These factors all contribute to a growing sense of urgency to create more integrated, sustainable, and resilient water supplies even in those jurisdictions predicted to continue to have adequate water supply.

Achieving this will not be resolved through one factor alone and will require urgent measures to manage the supply demand balance, including leakage reduction, to ensure alignment with wider governmental climate action plans and goals, combined with the development of new supply options to mitigate against supply restrictions in the near future.

The challenges of achieving a sustainable economic level of leakage

(SELL) in countries like Ireland and the United Kingdom – with ageing infrastructure, growing urban populations, and dispersed rural settlements – are well documented. However, from a regulatory and moral imperative in the face of global water scarcity, the water sector needs to continue to progress and innovate towards this goal.

In addition, water consumption, whether at a personal or industry level, needs to become a priority for all, through national education, minimising our own personal use and the development and implementation – at sector and national levels – of reuse and recycling programmes in housing and high water usage industries. The Tuas Water Reclamation Plant based in Singapore shown in Figure 1, recycles water for further reuse.

For some industries, novel thinking will be required to ensure that the water required is fit for purpose; in some instances that may not be potable drinking water. For example, recycled effluent could be a suitable source for cooling waters.

Notwithstanding the achievement of longterm success in these areas, the delivery of new resilient supply options will continue to be necessary to meet the growing needs of our existing economies.

In England, a national review suggested that when considering population growth, environmental ambitions, and climate change, the southeast will be subject to water shortages by 2040. These projections included assumptions of a 50 per cent reduction in the current leakage levels and a reduction in the per capita consumption to 110 litres per person per day – the consumption target set by Ofwat (the Water Services Regulation Authority) for users across the country.

Allowing for that, a national programme to implement Strategic Resource Options (SROs) is proposed at a cost of approximately £17 billion. These options will store, transfer, and recycle water to provide resilience across the country. The need for which has been proven through regional and utility water management plans, which have been

Figure 2: Collaborative, outcome-focused, proportionate, and timely approach to delivery of DCO

progressed through statutory and nonstatutory consultation processes.

The Regulators’ Alliance for Progressing Infrastructure Development (RAPID) was set up in 2019 to help accelerate the development of this new water infrastructure and design future regulatory frameworks for its operation. This regulatory body is made up of the three water regulators: Ofwat, the Environment Agency, and Drinking Water Inspectorate. They will provide a seamless regulatory interface, working with the water industry to promote the development of national water resources infrastructure that is in the best interests of water users and the environment. The goal is to ensure this infrastructure can be implemented in a timely manner to ensure resilient water supplies across the country.

These substantial projects will use the Development Consent Order process to achieve planning. This is similar to the

Strategic Infrastructure Development (SID) regulations in Ireland and elevates the planning decision to a national level. As with all planning processes, and key to the effective and timely delivery of critical public infrastructure, robust consultation is required to ensure that public input is incorporated into the ultimate decision making. In this regard, the process includes public consultations for each SRO submission and for the regulatory determinations for each project approval ‘gate’ as defined by RAPID. These consultation stages augment previous consultation on establishing the need for the projects, ensuring the public, statutory and nonstatutory consultees and interested parties are fully aware at all stages of the process, with their knowledge and inputs considered.

In addition, there is an acknowledgement that this infrastructure is larger in scale than anything undertaken in the UK water sector in the last 40 years. Therefore, a robust process must be undertaken given the scale of impact both to those who will be impacted by its

construction and operation and those who will be impacted if it is not provided. Figure 2 demonstrates the collaborative approach required to achieve success across major planning projects.

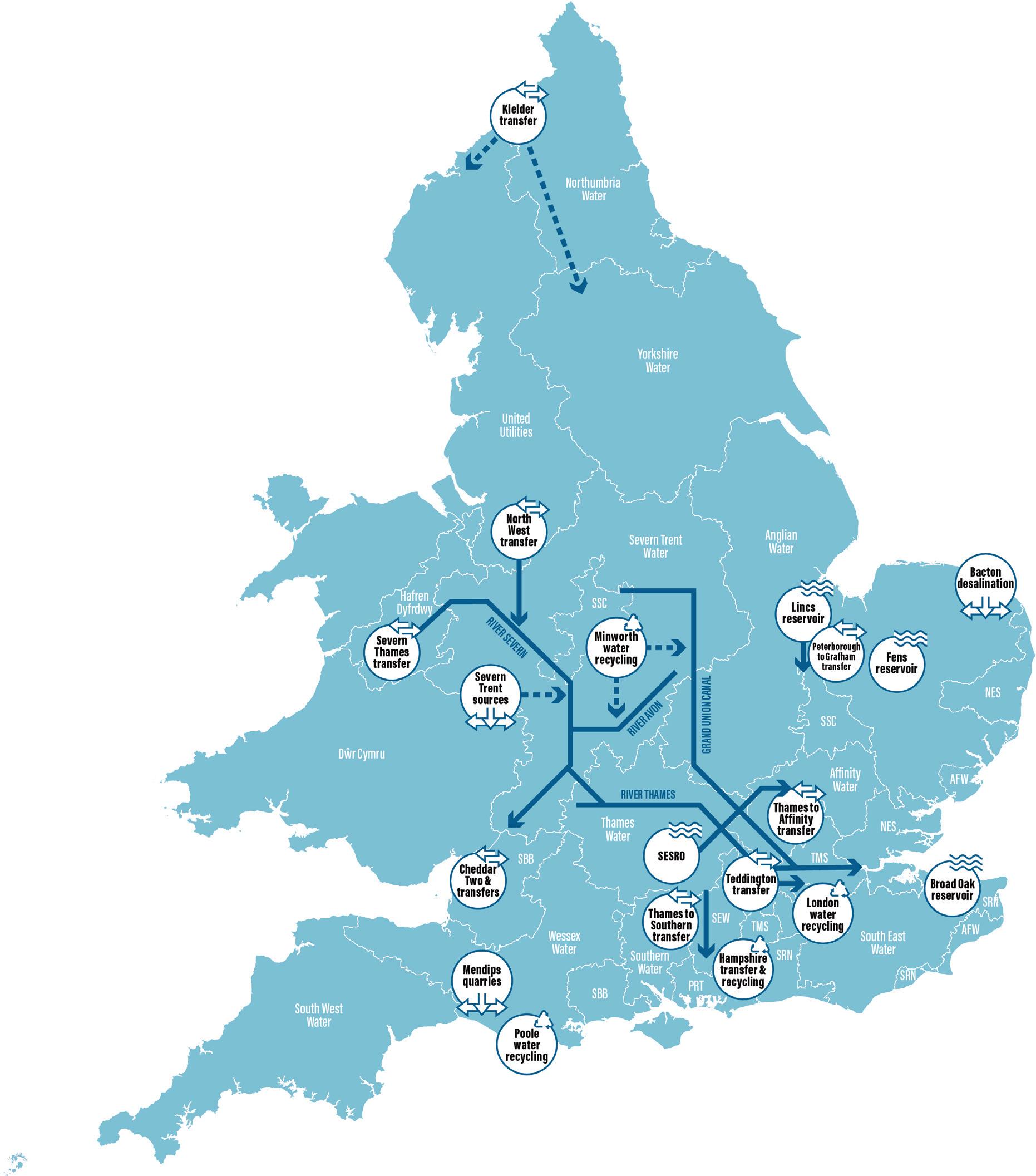

Figure 3 illustrates the scale of the UK Strategic Options (SRO) programme. Examples of these SROs in England include:

• the Southeast Strategic Reservoir Option, which will store 150Mm3 of water and cover a surface area of 6.5km2, at a cost of approximately £2.7 billion;

• the Severn to Thames Transfer, which will transfer water during times of drought from the River Severn (the largest river in the UK) 80km to the River Thames (the second largest River in the UK), with various water sources added to the Severn in times of low flow; and

• London Water Recycling, where effluent from existing wastewater treatment works would be treated through an advanced water recycling plant (AWRP) or a tertiary treatment plant (TTP) and discharged to the River Thames, where it can be abstracted as a raw water resource in times of low flow.

Figure 3: Representation of the UK Strategic Resource Options (SRO) Programme

Singapore’s Public Utilities Board (PUB) is an example of where the development of recycling has been effectively implemented alongside a national education programme to make this a valued asset, providing national water supply resilience, and avoiding overreliance on international trade to

import water. Recycling programmes demonstrate sustainable and efficient use of the available water supply within a given jurisdiction.

The reality is that all water is reused as there is truly no new water on the planet. Organisations such as PUB have safely treated used water to augment their water supplies for decades. The technology is there; however the real challenge is developing a thoughtful way

“Many countries are now predicting a significant upturn in investment in water infrastructure over the coming decade.”

to implement potable reuse programs to meet public expectations.

PUB has also developed NEWater, its own brand of ultraclean, high-grade reclaimed water. Singapore has five NEWater plants which further purify treated, used water to produce this NEWater, which has passed more than 150,000 scientific tests and meets and surpasses World Health Organization and US Environmental Protection Agency standards for drinking water.

With the country’s water demand expected to double by 2060, Singapore is looking to use NEWater to meet more than half of this future water demand. Thanks to an integrated water management strategy nationwide, Singapore is one of just a few cities in the world to harvest its stormwater and practice large-scale water reuse as part of its diversified water supply approach.

Figure 1, shown previously, represents an animation of the Tuas Water Reclamation Plant (WRC) in Singapore, a key component of the Deep Tunnel Sewerage System (DTSS) Phase 2, which collects used water for further reclamation in NEWater

The provision of a resilient water supply is considered equal to a resilient power supply and strong transportation infrastructure and is therefore a key consideration for foreign direct investment when locating into a given country or region. In several countries, the funding for power and transportation has been strong over the past few decades, however, water and sanitation has not attracted the same level of investment. Globally, water investment has been insufficient and, as demands from users and regulators grow, there is a significant expenditure required to meet expectations. This will be a challenge to the water sector.

Many countries are now predicting a significant upturn in investment in water infrastructure over the coming decade, placing a strain on the sectoral supply chain to ensure that these aspirations are met. New procurement

models, new partnerships, and new thinking in how we implement water infrastructure will be required, alongside a change in our relationship with the water that we use on a daily basis. The latter will require national public campaigns to highlight water use ratings for various activities and products.

Financing and procurement are two of the most critical challenges within major projects globally. These two factors play an integral role in defining project success, especially long-term cost and risk. Funding and delivery models can help create the right cost structures and improve procurement results through competitive tenders or bids. For water utilities to develop resilient, sustainable major water infrastructure projects between 2025 and 2030, in addition to major standalone schemes, the industry requires effective procurement and delivery mechanisms. Delivery partners must build effective, multidisciplinary teams that use cross sector insights and global teams to drive productivity. The Direct Procurement for Customers (DPC) model in the United Kingdom, which is similar to Design Build Operate and Finance, offers a tailored solution and multiple client benefits, especially within the fast-growing water sector.

From a sustainability perspective, addressing our water consumption behaviours while continuing to drive down and maintain leakage rates require priority to minimise waste, costs and carbon generation. This approach, combined with the successful and timely delivery of national water storage, recycling, and transfer projects and programmes, will ensure countries with manageable water stress levels, like Ireland and the United Kingdom, can continue to meet the needs of their population, through the provision of safe, sustainable water supply nationally, meeting the requirements of SDG 6 while enabling long-term economic growth.

For more information:

T: +353 1 202 7718

E: Jillian.Bolton@Jacobs.com

W: www.jacobs.com

A payment scheme rewarding farmers for high water quality outcomes within their catchments should be established, researchers at the Economic and Social Research Institute (ESRI) have recommended.

The research paper, published by the ESRI in July 2024, outlines a proposal for future agrienvironment schemes to achieve good water quality status.

Authored by Wellington Osawe, John Curtis, and Cathal O’Donoghue of the ESRI, the research envisages payments to farmers within a catchment proportional to water quality outcomes within said catchment.

To facilitate this, environmental monitoring would be expanded to produce assessment reports for each catchment on an annual basis so that scheme payments reflect the most recent performance and facilitate flexibility in farming practices.

With a scheme that focuses on whole-of-catchment and payments based on catchment water quality, all agricultural land within a catchment would be covered by the scheme. As such, all farmers within

a catchment would share the results-based payment.

Rather than national limits, the ESRI recommends that all catchments should have bespoke nitrate and phosphate limits based on catchment assimilative capacity, i.e., catchment nitrates quotas. Trading quotas between farmers within catchments would facilitate the development of the most efficient or intensive farms without impinging on water quality.

The proposed scheme ultimately envisages payments to farmers within a catchment, proportional to water quality outcomes. As there would be a time lag before improvements in water quality are observable, payment could comprise three elements in a transition phase.

One element of the payment would be for water quality outcomes, a second element would cover costs related to modifying farming practices to transition to a lower nitrates operation, and a final element would encompass the more traditional input-based payment such as, for example, tree planting and field margins.

The researchers outline a framework comprising five key attributes that should be inherent to future agri-environment schemes. They are:

1. Results-based incentives: Payments for agri-environment services delivered by farmers should be results-based. Such an approach would align farmers’ incentives with scheme objectives. Historically, many schemes have compensated farmers for the provision of inputs such as tree planting rather than for environmental improvements such as water quality.

2. Area-based payments: Good environmental outcomes need to be delivered at scale, which means that good agricultural practice needs to occur across farms and catchments to enable a step-change in environmental outcomes. Consequentially, financial incentives would be implemented on a per-hectare basis where applicable to encourage participation.

3. Catchment-based: Environmental outcomes within water catchments depend on all activities occurring within the catchment, not just single farms. Therefore, agrienvironment scheme outcomes would be assessed at the catchment level in the case of water quality and not on a farm-by-farm basis. This approach ensures that environmental monitoring, outcomes, and agri-environment schemes align.

4. Simplicity: Rule books for agri-environment schemes are long and complex. A results-based scheme would facilitate a simpler rule book and less administration. If payment is ultimately based on environmental outcomes, how the outcomes are achieved is not pertinent, assuming no other adverse environmental externalities.

5. Flexibility: Historically, rule books for agri-environmental schemes were fixed and did not allow much flexibility. The ESRI believes that such schemes should be as adaptable as possible to changing conditions and knowledge such that they continue to incentivise participants to achieve the best environmental outcomes.

In the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) Water Quality in Ireland 2023 report, published in June 2024, the EPA asserts that increased concentrations of nutrients, such as phosphorus and nitrogen, are impacting water quality and the biological health of water bodies.

“Human activities, such as agriculture, wastewater (domestic and urban), and forestry, are the primary cause of nutrient loss to our waters,” the EPA states.

The water quality report shows that longstanding water quality challenges persist, with 42 per cent of river sites nationally demonstrating unsatisfactory nitrate concentrations (above 8mg/l NO3). These elevations of nitrate levels primarily derive from agriculture through chemical and organic (manures and urine from livestock) fertilisers or from direct discharges from waste water.

In its conclusion, the EPA states that, as the main source of nitrogen in waterways is agriculture and the main source of phosphorus is agriculture and wastewater, these sectors must do more to reduce nutrient losses to water.

Concluding, the ESRI researchers assert that, in some respects, the framework for agrienvironment schemes proposed here is an “incremental evolution of previous schemes”. However, they also state that, in other respects, the proposals represent a “radical departure from current practice,” moving away from a largely inputs-focused farm-holding level scheme to one with a focus on catchment-level outcomes.

Today’s world demands that we achieve more with less; less space, less materials, and less waste, writes Anne-Marie Conibear, Egis’ Country Lead for Energy and Water.

This is certainly the case when it comes to water and energy. In responding to the urgent need to upgrade our infrastructure, we must aim to tread lightly – achieving more with less and making as much use as possible of existing structures with new technologies. It is critical that we deliver the infrastructure needed to meet the demands of our growing population, but we must also reduce infrastructure emissions at all stages from green procurement, lean design, and ecoconstruction, to operation and end-of-life disposal.

At Egis, we refer to this requirement as the paradox of the 21st century and for us the solution lies in innovation. This is why we have enshrined creativity as one of our core values; fostering a spirit of innovation in our areas of technical expertise, our methods, and our development of new services and business models.

In our experience, innovation involves the development of both creative solutions which break the status quo, in addition to improving what already exists. It is an approach that can, and has, yielded extraordinary results.

Ringsend Wastewater Treatment Plant is the largest facility of its kind in Ireland with a capacity that equates to that of the next nine largest plants combined. Working as part of the 3JV consortium, with TJ O’Connor & Associates and Royal Haskoning DHV, we are providing civil, structural, process, mechanical and electrical and project architect design services for an ongoing upgrade of the plant.

The Works will increase the plant’s treatment capacity from a 1.64 million population equivalent (PE) to 2.4 million by 2026 and are required to reduce nutrients in the treated effluent before discharge to an area that is designated as sensitive under the Urban Wastewater Treatment Directive.

The project’s setting presents constraints as it is located on a confined site that is bordered by sea and by a nature reserve. The plant must also remain operational throughout the construction period.

While a conventional approach would involve increasing the site envelope to

accommodate the required standalone secondary treatment WWTP structure, our engineering team explored multiple solutions to provide the capacity upgrade.

This process involved the application of eco-design principles; reducing the ecological and physical footprint required to treat the increased load while increasing the energy efficiency of the upgraded plant. The team’s preferred solution was to utilise the Royal HaskoningDHV patented Nereda® Aerobic Granular Sludge (AGS) technology for the plant upgrades. This allowed for increased biological treatment capacity within the same footprint as a conventional activated sludge treatment plant.

The construction of a new standalone 400,000 PE treatment plant and retrofitting some of the existing Sequencing Batch Reactors (SBRs) with AGS technology has resulted in an increase in capacity without the need to construct significant additional tankage or a 9km long sea outfall. This has delivered a major reduction in the embodied carbon for the entire project.

The 400,000 PE construction contract received a Civil Engineering Excellence Award by the Association of Consulting Engineers of Ireland.

Further upgrades have included the installation of a p-fixation facility, the first of its kind in Ireland. This innovative technology created a circular economy where phosphorus – a dwindling valuable resource – can be extracted from sludge as struvite and used as agricultural fertiliser.

The application of Ephyra®, an innovative sludge digestion technology from Royal Haskoning DHV, means the upgraded plant can optimise anaerobic digester performance within the sludge line, effectively managing an increased load resulting from the plant upgrade and expansion.

Existing digester tanks are being retrofitted to increase their capacity in a process that will also allow production of sustainable energy in the form of biogas. The upgrade has eliminated the need to construct new tanks and the biogas is used to generate electricity and heat required on site – further reducing the plant’s carbon footprint.

In innovation, the solution sometimes lies in reframing the question. Working in close partnership with clients, we support as consultants by refining our brief. By surveying the landscape, exploring solutions, and engaging with colleagues and suppliers internationally, we have discovered better solutions that begin with clarifying the client’s needs and aspirations.

We also innovate by adapting technology in a ‘trickle down’ effect, optimising and applying solutions primed in larger projects for use on smaller-scale ones. For example, the Nereda® technology mentioned earlier has been used to allow energy recovery through biogas capture in smaller wastewater treatment facilities for Uisce Éireann all around Ireland. At a Regional Sludge Hub in Ireland we further maximised the yield from biogas using a thermal hydrolysis process –

high temperature and pressure – to create an energy-neutral site.

Our ability to innovate locally is guided by global experience. Our innovation hub nurtures start-up technologies creating use cases for deployment by our engineers globally.

In Qatar, for example, we have created seasonal storage lagoons for recycled water. In France and the Carribbean, we have used nature-based solutions in the form of 3D printed structures inspired by the living world to create a habitat for biodiversity along the coastline. Vigie Risk is a new real-time flood risk hypervisor designed to strengthen infrastructure resilience, and SustainEcho is a platform that uses AI to calculate the carbon footprint of our projects from the raw bills of quantities.

Innovation is in our DNA and we use it daily to respond with passion and determination to the major challenges of our time; climate change, biodiversity degradation, demographic growth, and rapid urbanisation – all of which demand creativity, innovation, and vigour.

W: www.egis-group.com

A new nature-based strategy aiming to prevent flooding emanating from rainwater in urban areas has been introduced by the Department of Housing, Local Government and Heritage (DHLGH).

Published in May 2024, Nature Based Management of Urban Rainwater and Urban Surface Water Discharges: A National Strategy, rationalises how nature-based rainwater solutions can be implemented in urban areas.

The strategy states that the best approach is to seek to replicate the capacity of greenfield areas to absorb, store, and treat rainwater, insofar as possible, drawing on numerous examples of use that has been adopted across the world. This is an approach whereby urban areas that would, traditionally, have been dominated by paved areas incorporate specially designed landscaped areas into which urban rainwater runoff is directed.

Various terms are used to describe this approach, including water sensitive urban design, ‘sponge city’, nature-based sustainable urban drainage, or urban nature-based solutions.

These landscaped areas are primarily designed to take in, store, and treat urban runoff and to then discharge the treated runoff at a slower rate back into the existing urban drainage network. While the design will allow excess flows to bypass the landscaped areas and flow directly into the existing drainage network, the landscaped areas will have removed most of the pollutants which are contained within the “first flush” of runoff from the paved landscape.

Reducing the percentage of impermeable surfacing and increasing the area of urban landscaping result in multiple benefits in addition to the reduction in rainfall induced flood risk and runoff pollution. These benefits include reduced “heat island” effect and urban noise, a more pleasant urban

environment that supports active and sustainable transport modes and increased biodiversity.

Ideally the integration of nature-based rainwater management will form part of the broader approach to urban development across the settlement.

Traditionally, urban areas have been designed so that rainwater is directed from buildings and impermeable surfaces into collections points (gullies) and from there into an underground network of pipes, ultimately discharging into local rivers and streams.

Analysis of European flooding records between 1960 and 2010 suggests that there has been increased flooding in the autumn and winter periods from rainfall throughout the northwest of Europe, including Ireland.

The strategy outlines how in urban areas, a large proportion of the surface area is made up of hard surfaces which are impermeable, meaning that all rainwater falling on that area remains on the surface and must be managed by an urban drainage or rainwater management system.

With the resulting polluted rainwater, which comprises flooding –water which cannot be contained by existing drain infrastructure –leads to increased pollution in two ways:

1. rainwater falling on many urban surfaces such as roads, streets, and roofs will become contaminated by a wide range of pollutants before entering the drainage system and being discharged into receiving waters; and

2. in many older urban areas, the drainage system is combined and, therefore, rainwater runoff is mixed with sewage and wastewater. As rainfall increases beyond the sewer capacity, these systems overflow into local waterbodies, with resultant pollution.

Although existing infrastructure is arguably incapable of meeting demand, the strategy concludes that it is “neither practical nor sustainable” to simply replace all existing urban drainage networks with larger pipes. Simultaneously, it is not possible to stop rainwater falling onto urban areas; indeed increasing intensities are likely.

At the same time, there are two established trends that, taken together, mean that the traditional approach to urban design is not sustainable. These are:

1. the continuing growth in urban population; and

2. the changes in climate that have already happened and will continue to happen, with predicted increases in rainfall intensity and longer periods of summer drought with high temperatures.

As such, nature-based solutions, the DHLGH asserts, offer a sustainable alternative. Writing for eolas Magazine, Minister of State at the Department of Housing, Local Government and Heritage with responsibility for Nature, Heritage and Electoral Reform, Malcolm Noonan TD, observes: “Not only can naturebased solutions provide attractive features and focal points within the landscape, they can also provide significant ecological value.

“Designed to manage rainwater, they slow and store runoff and allow it to soak into the ground. Their benefits are wide-ranging, filtering out pollutants that would otherwise end up in our waters, reducing flooding and easing the burden on combined sewer systems.”

A national survey commissioned by The Water Forum (An Fóram Uisce) finds the public are not knowledgeable about water resources.

The Water Forum provides a platform for stakeholder engagement on water policies and the management of Ireland’s waters. Members of the Forum represent 16 different sectors bringing diverse opinions, perspectives, and interests to water management issues. Sectors include agricultural organisations, angling, business, community and voluntary groups, domestic water consumers, education, environmental NGOs, fisheries, forestry, recreation, rivers trusts, rural water, social housing, tourism, trade unions and youth.

In February 2024, 14 new members were appointed to the Forum, to join 13 existing members who have been reappointed for a second term. All members of the Forum are nominated by their representative organisations and appointed by the Minister for

Housing, Local Government and Heritage, Minister Darragh O’Brien TD. This wide range of representation provides an opportunity to input different values and outlooks to policy development for water management and the implementation of the Water Framework Directive. The Forum’s statutory role is to provide advice to the Minister of Housing, Local Government and Heritage, Uisce Éireann, the Commission for Regulation of Utilities (CRU), and the Water Policy Advisory Committee.

A goal of the Water Forum’s Strategic Plan is to promote awareness and education on the value of and threats to water. To inform this action, the Forum commissioned a national survey of water consumers (Uisce Éireann customers, Group Water Scheme customers and private well owners) to

determine their:

1. knowledge of water supply, quality and security;

2. satisfaction with supplier communications; and

3. water conservation awareness. The survey was hosted online by Interactions Research Ltd. The national sample consisted of 1,518 adults, recruited as a demographically representative sample of the population in terms of gender, age, region, and social background and the survey was completed in August 2023. Of those surveyed, 81 per cent were connected to a public water supply provided by Uisce Éireann, 12 per cent were connected to Group Water Schemes and 4 per cent sourced their water supply from private wells.

54 per cent of public water consumers lack knowledge of where their water comes from or how it is treated and 26 per cent do not know who to call if there is a problem. Those connected to private Group Water Schemes showed markedly higher knowledge on local water sources, indicative of a better connection to local water supplies. People surveyed also showed significant confusion over potential future water quality and security challenges.

Just over half of Uisce Éireann consumers were satisfied with drinking water quality, despite the EPA consistently reporting very high standards in public water supplies. 10 per cent of people in Ireland get water from private wells, yet only one-quarter of private well owners test their wells annually as recommended by the EPA. This leaves them at risk of water quality issues in their water supply.

Water conservation is considered important by consumers with 74 per cent of those surveyed agreeing that we need to improve water conservation. However, they do not know how much water they use or how to conserve water in their homes and stated that more information would be helpful.

To address the knowledge gap and develop a water smart society that truly values Ireland’s water resources we need:

• a public information campaign to build knowledge of water treatment and supply processes, how wastewater is treated, and the potential threats to drinking water security and supply;

• strengthened Uisce Éireann customer engagement and communications to improve public trust in drinking water supplies, to make sure people know who to contact if there is an issue and ideally to let people know how much water they are using;

• a significant intervention to inform private well owners about well maintenance, and the need to regularly test their water quality to prevent risk to supplies; and

• enhanced awareness around how to increase water efficiency in the home, to take advantage of the strong support for water conservation.

The Water Forum has presented the findings to Uisce Éireann and shared the reports with Uisce Éireann and the Department of Housing Local Government and Heritage. We have commissioned further research on private wells to find out what further action can be taken to reduce risk to private water consumers. We have commissioned a cost-benefit analysis of water efficiency measures in the home. This work is all ongoing.

The Water Forum commissioned Maigue Rivers Trust and Mary Immaculate College to develop education materials on: (1) Water habitats and biodiversity; (2) Water quality and pollution; (3) Exploring rivers using digital maps; and (4) Impacts of our water use. While

targeted at schools the resources are suitable for all ages. Teaching materials and student workbooks are available for download from the Water Forum website.

To share information on encourage dialogue, the Water Forum is hosting a conference to discuss the impacts of climate change on water quality and quantity. Agencies will be invited to discuss the challenges and opportunities of taking a catchment-based approach to addressing climate adaptation for floods and droughts. Academics, agencies, and stakeholders will contribute to panel discussions and deliberations. The Conference will be held in the Tullamore Court Hotel, County Offaly on 20 November 2024.

For more information: E: info@nationalwaterforum.ie W: www.thewaterforum.ie

Bathing water quality for 2023 remains high, with 97 per cent of assessed bathing waters having met or exceeded the minimum required standard. However, the number of pollution incidents and water bodies with of a ‘poor’ standard both increased in 2023.

In 2023, of the 148 identified bathing waters assessed, 143 (97 per cent) met or exceeded the minimum required standard of sufficient. 114 bathing waters (77 per cent) were of excellent quality, a decrease from 117 (79 per cent) in 2022.

The majority of bathing waters have excellent or good quality:

• 97 per cent of the 148 identified bathing waters met or exceeded the minimum required standard.

• 114 bathing waters (77 per cent) were excellent quality, a slight decrease from 117 for 2022.

• Five bathing waters were poor (up two from 2022) and the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) has confirmed these will have a swimming restriction for the 2024 season. These were Lady’s Bay, Buncrana; Trá na mBan, An Spidéal, Balbriggan (Front Strand Beach); Loughshinny Beach; and Sandymount Strand.

• One bathing water – Aillebrack/Silverhill Beach, County Galway – was classified for the first time with excellent quality.

Urban wastewater was most frequently reported as the likely cause of incidents in 2023. Other reported causes included agricultural runoff, and pollution entering the surface water collection system through misconnections or runoff from urban areas.

Heavy rainfall can result in wastewater overflows and in runoff from agricultural lands and urban areas, which can cause short-term deterioration in water quality. Record rainfall levels in July and storms in August led to more bathing water warnings in 2023 than previous years.

In 2023, the EPA was notified of 45 pollution incidents which resulted in the closure of bathing waters, up from 34 in 2022. The majority were due to the presence of pollution in sample results (29 incidents). Bathing waters were also closed as a precaution after overflows in the sewer network (12 incidents) and due to algal blooms (four incidents).

Urban wastewater

Misconnections/runoff from urban areas

Proliferation of cyanobacteria/macroalgae Diffuse pollution from agriculture

Contamination from animals/birds Septic tanks

Maria O’Dwyer, Uisce Éireann’s Infrastructure Delivery Director.

With over 25 years of industry experience, Maria O’Dwyer is taking on the role as Uisce Éireann’s Infrastructure Delivery Director with a steadfast focus on delivering transformative water services that enable communities to thrive.

Looking back on almost a decade with Uisce Éireann, Maria O’Dwyer reflects on the critical infrastructure delivered to date, including the 180 water and wastewater treatment plants which have been built and upgraded across Ireland.

Whilst proud of the achievements to date, O’Dwyer knows that this is a multigenerational project built on the legacy of the asset base Uisce Éireann inherited. Now, as she takes on her new role as Uisce Éireann’s Infrastructure Delivery Director, it is her job to “continue to deliver an effective and efficient capital investment programme in a safe way.”

But the task is much broader than that.

“We are always seeking out new solutions to transform how we deliver that programme, leveraging innovation and sustainability, working in collaboration with all stakeholders, challenging ourselves, our team, and our delivery partners so we can do more for the communities we serve,” she says.

Every day there are challenges across the country but the commitment and dedication of the Uisce Éireann team

keeps everyone focused on the task ahead.

“It is going to take time to overcome all these challenges, but it is reassuring to see large projects like the Arklow Wastewater Treatment Plant, which is close to completion, come to fruition. It is brilliant to be able to bring that type of investment, €139 million, to a large town like Arklow so it can thrive and develop in ways it could never before due to the absence of functioning wastewater services.”

With a €5.35 billion investment from 2020 to 2024, Uisce Éireann is driving improvements in water services infrastructure. A significant increase in spending for 2025 to 2029 will be needed to continue meeting the levels of demand for water services from both customers and regulators.

“Progress is happening albeit it is not possible to do so at the same pace in every town and village across Ireland,”

O’Dwyer says, adding: “We are prioritising bringing water and wastewater infrastructure up to standard, with the

safe delivery of our capital investment plan central to everything. Our greatest challenge lies in securing the sustained multiannual funding we need to continue upgrading infrastructure where it is needed most and ensuring that we can achieve our objectives now and into the future ensuring communities can thrive”.

Seeking out innovative sustainable solutions to long-term challenges is also a key focus.

“Much of our capital investment results in carbon and construction delivery can impact on the natural environment and biodiversity. Delivering our capital investment plan in a sustainable way, utilising energy efficient design and nature-based solutions where possible can result in more sustainable long-term solutions such as in Boherbue, County Cork.”

Water Supply Project (WSP): “It is critical to securing Ireland’s economic growth and housing needs for the future”

Growing up in Cashel, the Tipperary native is well placed to outline the benefits of one of the largest infrastructure projects in the history of the State. It will create a water spine across the country and ensure an urban level of service to towns and villages from her native county through the midlands, the counties of Offaly and Westmeath before reinforcing existing supplies in counties Kildare, Dublin, Wicklow, and Louth.

Uisce Éireann predicts that by 2044, 34

per cent more water will be needed in the Eastern and Midlands region than is available today.

“The WSP is fundamental to the State to ensure sustainable resilient water supplies for half of the population up to 2050 and beyond. We must remember that we are a small country and if we want to thrive as a nation, we need that 50 per cent to have sustainable and resilient water services.

“A significant portion of the country (1.75 million people) is dependent on a single river source (the River Liffey is only the 19th largest river in Ireland); for the resilience of the water supply and the ecology of the River Liffey, we need a new diverse supply coming into the East.

“Some critics have questioned why Dublin should benefit in terms of investment but as a national utility, we are investing in every part of the country. In fact, most of that investment to date has been outside the Greater Dublin Area with the WSP to benefit areas along the route of the new pipeline,” Infrastructure Delivery Director asserts.

Growing up in her family’s shop in Cashel, O’Dwyer has known the importance of communication and customer service; this has been honed across her many years of industry experience working in national regulated utilities (O’Dwyer worked with Gas Networks Ireland for 11 years before joining Uisce Éireann).

In August 2024, Uisce Éireann launched a new text message system to keep householders, businesses and key

stakeholders informed about planned and unplanned outages and boil water notices in their area with timely updates on status.

“Carrying out essential maintenance and transformation of our infrastructure can impact on service availability. This outbound notification service will be key to keeping our customers informed and building trust and confidence in the organisation,” she notes.

Knowledge is key: “We must continue to invest in our people and our collective knowledge.”

It is important for Uisce Éireann to develop the required knowledge and capability within the organisation but also within its delivery partners.

“Funding is our first constraint and capacity our next and by that, I mean capability within the supply chain. It is vital that water services as a sector continues to attract people with the correct skills and expertise.

“Treated drinking water is like a food product – its availability was not fully appreciated in the past but now with climate change and system constraints, along with much higher standards and regulations, increased investment is needed to be able to provide the service our customers deserve.

“It is critical that we work to find more innovative and sustainable solutions to deliver this critical service. Ultimately that will be the key to transforming water services long term,” O’Dwyer outlines.

Safety first: “Our priority focus is to keep each other safe.”

While delivering projects across the country is key, safety comes first for the Infrastructure Delivery Director. As recently as August 2024, she launched a new website for employees and contractors as part of the organisation’s Am I Safe? campaign.

“In Infrastructure Delivery, we want to ensure the contractors who work at our construction sites and operational plants work safely and go home safely each day. The Am I Safe? campaign is one of several initiatives that support this goal.”

In her new role O’Dwyer is looking forward to the opportunities ahead as the organisation assumes full responsibility for public water services from all 31 local authorities. “Working in Uisce Éireann is a privilege and our diverse team has a clear purpose. Water services are critical, and we get to contribute to delivering transformative water services that enable communities to thrive,” she concludes.

W: www.water.ie

On an annual basis, the Climate Change Advisory Council (CCAC) publishes a sectoral Adaptation Scorecard. Among the priority policy sectors included are flood risk management, under the remit of the OPW, and water quality and water services infrastructure, under the remit of Department of Housing, Local Government and Heritage (DHLGH). In 2023, the former achieved an overall progress rating of ‘good’ while the later was rated ‘moderate’.

Sectoral Adaptation Plans or SAPs are mandated under sections 6 and 7 of the Climate Act and were developed as a core action under National Adaptation Framework (NAF) 2018. In an effort to provide a structured approach to sectoral climate change adaptation, under NAF 2018, 12 priority policy sectors were grouped into nine SAPs and clustered under four themes.

Three of the priority sectors – flood risk management; water quality; and water services infrastructure – were grouped under the water resource and flood risk management theme.

Assessing the progress of SAPs – and local adaptation strategies – and monitoring implementation of the NAF, the CCAC publishes an annual sectoral Adaptation Scorecard. Alongside local government and DECC, priority sectors are assessed against three key adaptation themes (via a questionnaire developed by the CCAC):

1. risk, prioritisation, and adaptative capacity;

2. resourcing and mainstreaming; and

3. governance, coordination, and cross cutting issues.

Given the shared challenge of inadequate financial resourcing and staffing capacity, the second theme –resourcing and mainstreaming –continues to be a pervasive challenge across sectors.

According to a summary of observed and projected climate changes and impacts for Ireland contained within NAF 2024, in Ireland, observed annual precipitation has increased by 6 per cent from 1989 to 2018 when compared with 1961 to 1990, with evidence indicating a tend toward increased winter rainfall and decreased summer rainfall.

Further projections suggest that there could be a substantial decrease (of between 0 to 17 per cent) in precipitation in summer months. By mid-century, it is predicted that Ireland’s precipitation climate will become more variable, with significant increases in the frequency

and intensity of both dry periods and extreme precipitation events.

As a consequence of decreased summer precipitation, drought could increase in frequency, resulting in water stress for soil and livestock, while more extreme precipitation events could then lead to more frequent and intensive pluvial (overland flow) and fluvial (flow from rivers and streams) flooding.

In the water quality and water services sector, there are two main potential impacts of climate change:

1. projected increases in average temperatures and an increase in invasive species could undermine habitats and reduced water quality; and

2. the projected increase in droughts allied to higher evapotranspiration rates could reduce river flow, groundwater recharge, and reservoir refill capacity, ultimately contributing to water supply shortages. At the

same time, increased precipitation could increase pollutant concentrations (especially nutrients) in water bodies, leading to eutrophication and algal bloom.

Meanwhile, in flood risk management, there are several potential impacts of climate change, including:

1. projected increased storm intensity, extreme precipitation events, and rising sea levels could result in a higher frequency of extensive flooding;

2. many existing flood relief schemes requiring reappraisal in the absence of climate adaptation provisions;

3. saturated agricultural lands impacting drainage schemes;

4. rising sea levels and extreme precipitation damaging embankments in estuarine areas, increasing exposure to coastal flooding; and

5. inhibiting access to hydrometric stations.

In its July 2023 Third Climate Change Adaptation Scorecard Final Report, the Climate Change Advisory Council published sectoral adaptation scorecard results for both flood risk management (under the remit of the OPW) and water quality and water services infrastructure (under the remit of DHLGH). The scorecard is a summary of progress on national climate adaptation in 2022.

Overall, the adaptation plan for the water quality and water services infrastructure sectors is to assess significant future climate risk and outline the available adaptative measure to establish a climate resilient water sector. These measures, developed by stakeholders engaged in future adaptation planning, include:

• adopting an ‘integrated catchment management’ approach;

• enhancing water services infrastructure via treatment capacity and network functions;

• water resource planning and conservation (in both supply and demand); and

• incorporating climate actions into monitoring programmes and research.

In the CCAC’s assessment, the water

quality and water services infrastructure sectors have made progress in establishing climate resilience through collaborative measures, including a nature-based solutions pilot project incorporating DHLGH, Cork City Council, and Dublin City Council to manage urban run-off challenges.

However, from a CCAC perspective, the sector must improve its systematic coordination with the SAP to ensure that solutions are implemented at catchment scale, thereby unlocking mutual benefit for water quality, biodiversity, and climate resilience. This, it suggests, could be delivered by the project delivery office being formed under the new River Basin Management Plan.

Meanwhile, key challenges include a failure to make significant progress towards understanding climate change impacts and developing the necessary solutions across the sector. Allied to this is an absence of detailed monitoring of SAP implementation, specific information on the effectiveness of coordination structures for this implementation, and evidence of adaptation being mainstreamed across government departments, local authorities, and relevant agencies.

Two plans – either developed or under development – which contain climate resilience aspects across the water quality and water services infrastructure sectors are:

1. the Fifth Nitrates Action Programme (2022-2025) which is intended to prevent pollution with agriculture origins and improve water quality; and

2. the National Water Resources Plan (developed by Uisce Éireann) which will outline Ireland’s move towards “a safe, secure, reliable and sustainable water supply” over the next 25 years, including via smarter supply and demand reduction.

The CCAC assesses that the OPW has strong internal structures to cohesively plan, implement, and monitor the flood risk management sector SAP, as well as wider adaptation actions. It also reports that effective cross-sectoral working relationships and leadership buy-in have been established.

However, with the OPW seeking to mainstream adaptation into policy –including integrating future flood risk in economic appraisal guidance and

embedding climate change consideration and adaptation requirements in the design of existing and new flood relief schemes – staffing remains a challenge.

As such, while training is being undertaken, given existing and forthcoming strategies and programmes, the CCAC has recommended that dedicated adaptation staffing be expanded with the OPW.

The CCAC also recommends the provision of a “greater demonstration” of the impacts of flood relief work undertaken by the OPW, suggesting that those most vulnerable to flooding are consulted.

As such, overcoming barriers to adaptation in water-related sectors remains a challenge. These barriers include insufficient resourcing and inadequate understanding of vulnerability to the risks and impacts of climate change.

Concluding, the CCAC’s Adaptation Scorecard identifies the pursuit of “string internal governance structures and leadership buy-in” as being key enablers for the sectors. It also suggests that the establishment of steering groups and coordination structures to be “crucial” for the implementation and monitoring of the SAPs. Finally, it advocates for enhanced community, NGO, and private sector participation in adaptation planning and implementation.

Under NAF 2024, which establishes Ireland’s updated climate adaptation policy and was approved and published by government in June 2024, 13 priority sectors (under the remit of seven lead government departments) are required to develop new SAPs in response to the potentially negative impacts and positive impacts of climate change. These SAPs must be completed and submitted for government approval by 30 September 2025.

Furthermore in NAF 2024, the ‘water quality and water services infrastructure’ policy sector for adaptation has been rebranded as the ‘water management’ sector.

The asset base within water utilities is vast and ageing, with most of the infrastructure being underground, whilst also being challenged by external factors such as climate change and population growth. John Carty, Account Director (Utilities) with OutForm Consulting, writes.

Simultaneously, water utilities face funding challenges, increasing customer and stakeholder expectations, and the fundamental requirement of meeting regulatory compliance. The need to effectively manage their asset base in order to deliver value in achieving the organisation’s objectives has never been more keenly felt.

The scale of these challenges mean that water utilities have to ensure that their

assets are resilient, and they are planning to meet short-, medium- and long-term needs. Asset management means managing the infrastructure, reducing cost of ownership, whilst also delivering the levels of service that are being demanded by customers and stakeholders alike.

A key objective for water utilities like Uisce Éireann is ensuring service and environmental performance is enhanced, while also meeting the stresses placed on its infrastructure through extreme weather, demand for water, and population growth. It is vital that any

historic under-investment is addressed, but in doing so the cost of maintaining and improving assets is being fairly split between current and future generations, without undue risks being undertaken that could impact resilience and sustainability.

Asset management is about managing activities across a water utility to deliver value from the assets it owns. This means adopting a systematic approach to planning, operating, maintaining, and renewing infrastructure across key capability groups, such as asset inventory and analytical insights, strategy and planning, condition and performance assessment, risk management, investment planning, and objective decision-making across the end-to-end asset lifecycle.

As highlighted, the challenges faced by water utilities have evolved from centring

around cost reduction, which may traditionally have been seen as one of the key benefits of asset management. The reality is that although there are operating and capital efficiencies to be gained, there are also many other benefits which have grown in importance in the way that a modern water utility operates today, four key areas highlighted below.

1. Standardisation: Asset management is helping water utilities apply consistent standards and specifications, simplifying water and wastewater processes, equipment and materials, reducing reliance on spares and supplies, and standardising operations and maintenance practices.

2. Sustainability and net zero carbon: This is becoming increasingly important in the water sector and can be seen through building sustainability into asset management decisions. This drives increasingly sustainable outcomes in asset strategies, asset design, product standardisation, construction materials, and operational practices, reducing both operational and capital delivery carbon impacts.

3. Health and safety: Understanding asset health and risks, and prioritising what is essential will help remove process and employee safety risks, reducing the probability of H&S incidents.

4. Objectivity in decision-making: In all water utilities there is never enough capital or operating expenditure to do everything required. Effective asset management and quantitative investment planning and prioritisation based on a robust understanding of asset health and risk moves the investment decision away from ‘who shouts loudest’ to an increasingly objective and informed decision that provides overall best value for the organisation.

A fundamental element of asset management is ensuring it is not seen as being solely the domain of the asset management directorate, rather it is a philosophy about the ‘management of assets’ that must be pervasive in the organisation.

Considering the entire asset lifecycle from operating and maintaining the asset, monitoring the assets and understanding

the whole life costs, identifying asset performance and risks to service, prioritising needs in the context of the asset strategy, planning solutions, design and construction of an asset intervention, and back into operations, is essential in optimising asset management strategies.

Making asset management more pervasive facilitates a better understanding and collection of data around asset risk, performance, and the value of interventions. This creates a risk and value framework that can be used to compare the relative benefits to provide choices when it comes to making decisions on investment priorities.

Driving this approach creates a consistent, fair, and transparent application and management of investment decision-making, helping improve communication across teams involved in the asset lifecycle in understanding which investments have been taken forward and why.

In summary there are three key outcomes that effective asset management brings to a water utility.

1. Organisational collaboration across operations, asset management and infrastructure delivery: Connecting the strategic intent and outcomes of the organisation with the day-to-day management, operation, and investment decisions.

2. Making risk-based decisions: To balance competing demands for maintaining and improving performance and compliance, increasing efficiency, and mitigating risk is aimed at managing the organisation’s risk profile for improved sustainability and resiliency.

3. Value from the asset base: Value can be derived from applying asset strategies to balance cost, risk, and performance to extend asset life and maintain service. Asset management provides a priority framework to target resources for activities like condition and risk assessment, preventative maintenance and whole life costing. This helps define criticality and risk to target or defer investment and produce the best outcomes from the resources available.

Given the significant current and future pressing challenges water utilities face then the application of effective asset management provides a risk-based organisation wide approach, shifting mindsets towards objectivity and organisational outcomes through the entire management of the asset lifecycle.

For more information:

T: +44 (0)78 8140 9424

E: john.carty@outformconsulting.com W: www.outformconsulting.com

Amid legal challenges at EU level, as well as the publication of the third River Basin Management Plan (the Water Action Plan), significant changes are taking place in how Ireland implements the Water Framework Directive.

In place since 2000, the Water Framework Directive requires all EU water bodies to meet ‘good’ standard by 2027 via a process whereby EU member states establish river basin management plans.

Since passage, the European Commission has referred a number of EU member states, including Ireland, to EU courts, over alleged failures to meet these standards. For example, the Commission was referred to the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU) in January 2023 for allegedly failing to ensure that trihalomethanes (THMs) in drinking water did not exceed minimum failure levels outlined in the Directive.

In January 2024, the CJEU found that, by failing to ensure that the necessary remedial action was taken as soon as

possible to restore the quality of the water, Ireland had failed to give priority to its enforcement action.

EU member states were required to transpose the Water Framework Directive into national law by 22 December 2003. Ireland initially adopted legislation, but the European Commission found this legislation to be insufficient.

Progress had been made on implementation and legislation in the intervening years, but by June 2022, over 20 years after the entry into force of the Directive, the Government had still not fully addressed all of the shortfalls.

The Government has since announced the formation of a committee in Seanad Éireann which will examine the

implementation of EU directives, with the objective of avoiding future fines by the European Union for failure to implement, although there has been minimal engagement on European water legislation since this committee was established.

However, the Water Services Policy Statement 2024-2030, published in February 2024, underlines the Government’s commitment to ensure:

• compliance with water-related European Union legislation;

• delivery of UN Sustainable Development Goal 6 on clean water and sanitation; and

• implementation of the OECD Council Recommendation on Water.