Future of gas report

Sponsored by

Minister Eamon Ryan TD: Green hydrogen, decarbonised gases, and the energy transition

The decarbonisation of Ireland’s energy system and economy is a key priority for the Government in tackling the climate crisis, writes Minister for the Environment, Climate and Communications, Eamon Ryan TD.

There is a pressing need to phase out fossil fuels, for a faster uptake of renewable alternatives and to reduce our emissions. Through our strengthened climate legislation, the 2020 Programme for Government, and our annually updated climate action plans, we have set ourselves the ambition of halving Ireland’s

greenhouse gas emissions by the end of the decade and becoming carbon neutral by 2050.

We are determined that Ireland will play its part in EU and global efforts to stop climate change and, in so doing, harness the opportunities and rewards that will come from moving quickly to a low-carbon society.

As we transition to a more integrated, low-carbon energy system, enhancing our energy efficiency and greater electrification of our heat and transport sectors will be the primary building blocks of a net zero energy system. However, they alone will not be enough. There is no silver bullet, no one solution. We need to look at a variety of

solutions that suit different needs and circumstances.

Within this, decarbonised gases, such as green hydrogen and biomethane, will play a vital role as they provide the flexibility and energy density needed for the so-called ‘harder to decarbonise’ sectors, such as high-temperature heating, heavy transport applications, and, in the longer term, the aviation and shipping sectors.

They will also play a key role in decarbonising our electricity sector. Firstly, as we move towards 80 per cent renewables by 2030, there will be an increasing need for flexibility. Producing hydrogen from electrolysis at times when we produce more renewable power than instantaneous demand can provide some of this flexibility. Decarbonised gases can also be stored in large volumes.

This long-duration store of energy will be key to ensuring our energy system’s security and resilience into the future as we move from fossil fuels to a predominantly renewable-based system. This stored energy can then be burned in gas turbines or fuel cell technologies to create zero carbon electricity at times when the wind is not blowing. Whilst it is envisioned that these may only operate for a small number of hours each year, they will nonetheless be crucial to the resilience of our energy system.

Biomethane will be critical to decarbonising our agricultural sector particularly, taking wastes and residues from food and farms and turning them into renewable energy. This can drive a more circular and sustainable approach to food production, with bio-digestate helping to create a shift from the use of chemical fertiliser application to organic alternatives. Ireland has set a target to deliver 5.7 TWh of biomethane by 2030 in recognition of this fact and plans to publish a biomethane strategy later this year to enable the implementation of this target.

Ireland’s location in the Atlantic means that its coast is one of the most energy productive in Europe. With a sea area approximately seven times the size of its landmass, Ireland’s wind resources are amongst the best in the world. If we are to utilise these, we could produce significantly more renewables than we would ever need.

Hydrogen is one of the best ways of capturing these excess resources and

this represents a major opportunity for Ireland. We already know countries such as Germany will have a future deficit and are actively looking to source clean hydrogen internationally. Ireland is one of a small number of countries that has the natural resources to supply this.

In recognition of this opportunity, we are working on a number of projects, including engaging with our neighbours to better understand their needs. Earlier this year, I signed a Declaration of Intent with the German government to enhance our cooperation in the field of green hydrogen. I am also actively engaging with other neighbouring countries in Northwest Europe to enhance cooperation, building on the foundations laid through the North Seas Energy Cooperation. The Department of Enterprise, Trade and Employment is also developing an industrial strategy for offshore wind, which will be published next year. This strategy will begin to look at the skills and workforce needed to deliver the opportunity presented by our enormous offshore potential, as well as how we can best ensure that these resources are developed in a way which ensures there is maximum benefits to Ireland.

In July 2023, my department published the National Hydrogen Strategy, our first major policy statement on renewable hydrogen in this country. The strategy sets out our strategic vision for the role that hydrogen will play in

Ireland’s energy system and as a key component of our zero-carbon economy. It considers the needs of the entire hydrogen value chain, including production, end uses, transportation and storage, safety, regulation, markets, innovation, and skills. It also sets out 21 actions that will enable the development of the hydrogen sector in Ireland over the coming years. These actions aim to remove barriers which could inhibit early hydrogen projects from progressing today. They also aim to enhance our knowledge through targeted research and innovation across the hydrogen value chain, laying the groundwork to deliver on our longterm strategic vision for hydrogen in Ireland.

The future looks bright for decarbonised gases in Ireland. They will perform an essential role in the long-term deep decarbonisation and security of our energy system. Whilst the publication of the hydrogen strategy and anticipated publication of the biomethane strategy mark an important first step in developing an indigenous decarbonised gases sector in Ireland, there is still a distance to travel. However, the Government is fully committed to the journey. Together we can and will pursue the best interests of people through responsible, transformative climate action.

Ireland’s gas network to play a crucial role in our green hydrogen evolution

Gas Networks Ireland operates and maintains Ireland’s €2.7 billion, 14,664km national gas network, which is considered one of the safest and most modern renewables-ready gas networks in the world and is perfectly positioned to become the nation's backbone for the green hydrogen economy.

National hydrogen strategy

In July 2023, the Department of the Environment, Climate and Communications (DECC) published the Government’s National Hydrogen Strategy which outlines the future role green hydrogen gas – harnessed from offshore wind – and the gas network will play in specific areas of Ireland’s energy system, particularly for hard to abate sectors such as transport, industrial heating, and power generation.

Gas Networks Ireland has strongly welcomed its publication as an important milestone in the decarbonisation of Ireland’s gas network, which is essential in the transition to a net-zero energy system in Ireland by 2050.

Green hydrogen: a zerocarbon substitute for fossil fuels

The National Hydrogen Strategy recognises that green hydrogen offers an

incredible opportunity to enable Ireland to transition to a climate neutral economy by being a zero-carbon substitute for fossil fuels. In doing so, green hydrogen will help Ireland meet its 2050 net-zero emissions targets, diversify, and strengthen its security of supply, provide a pathway to energy independence, and in the long term, potentially leading to the creation of a new energy export market.

The Strategy also highlights that green hydrogen is both safe and feasible to use in the existing gas distribution network to transport hydrogen blended with natural gas now, and with some modifications, transport 100 per cent hydrogen in the future. Gas Networks Ireland continues to undertake a programme of hydrogen testing on the gas transmission network.

Hydrogen testing centre

Working with University College Dublin’s Energy Institute (UCDEI), one of the first innovation projects undertaken at Gas Networks Ireland‘s Network Innovation Centre was Testing of Blends of Hydrogen and Natural Gas (HyTest). The team tested the operation and performance of gas appliances utilising a range of hydrogen concentrations from 2 per cent to 20 per cent hydrogen.

The research found that householders using natural gas blended with up to 20 per cent hydrogen will not need to make any change to their existing domestic appliances or notice any difference. There was also a substantial emissions reduction obtained by blending hydrogen with natural gas.

EU hydrogen project partners

Gas Networks Ireland is also participating in a major project to help the European Union meet its new accelerated goals and radically increase the use of hydrogen by 2030. The EU is predicting that circa 14 per cent of energy consumption across Europe will be from hydrogen by 2050, while it is expected to

Showcased in the Government’s National Hydrogen Strategy as a case study, Gas Networks Ireland established its Network Innovation Centre, located in Citywest, Dublin two years ago, to understand the full potential of hydrogen and ensure that the gas network is capable of safely transporting and storing both blended and up to 100 per cent hydrogen into the future.

of the European hydrogen backbone (EHB) initiative.

be 20-35 per cent in the Netherlands, and up to 50 per cent of the total energy demand in the UK.

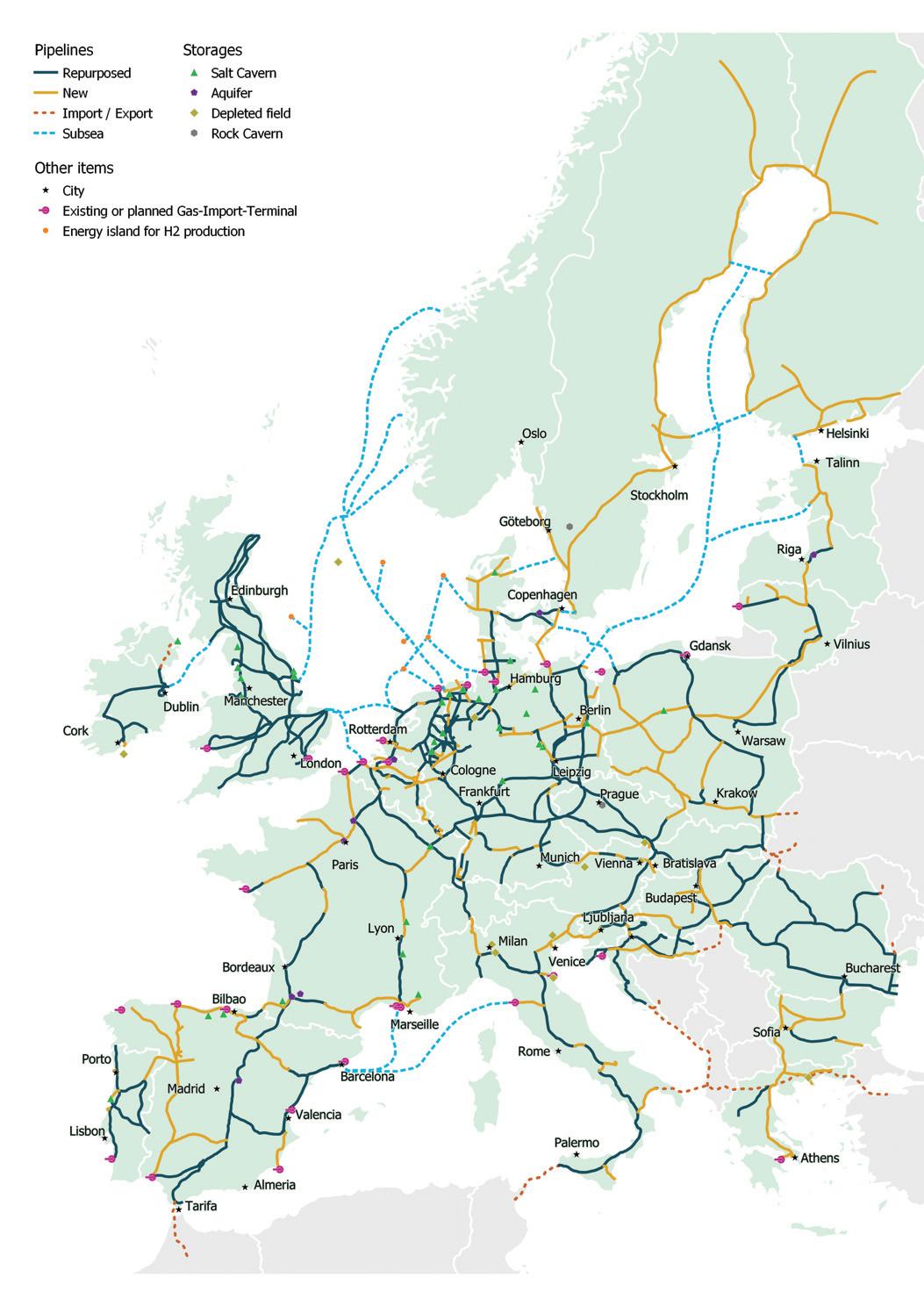

The European Hydrogen Backbone initiative is focussed on planning for the future development of a European hydrogen market through new pan-European hydrogen transport infrastructure. The planned hydrogen backbone network will largely be based on repurposing existing natural gas infrastructure. It is envisaged that by 2040, for example, Ireland could be connected to the new European hydrogen backbone via a repurposed subsea pipeline to the Moffat interconnector in Scotland.

Working with third level institutions and Science Foundation Ireland

Additionally, Gas Networks Ireland is working with academia. The utility is one of a number of industry players funding a €16 million strategic partnership with Irish third-level institutions that will examine how to holistically decarbonise the overall Irish energy sector. Led by UCDEI, NexSys (Next Generation Energy System) is also supported by Science Foundation Ireland.

Gas Networks Ireland has a number of other strategic hydrogen research partnerships, including one with Ulster University on hydrogen blend safety and with AMBER on materials compatibility with hydrogen.

Gas Networks Ireland W: www.gasnetworks.ie/hydrogen

The national gas network: Ireland’s hydrogen-ready infrastructure

Cathal Marley, CEO of Gas Networks Ireland.

Gas Networks Ireland is supporting Ireland’s journey to a cleaner energy future by working to replace natural gas with renewable gases, such as biomethane and green hydrogen.

Welcoming the Government’s strategy and its commitment to supporting the establishment of a green hydrogen industry in Ireland, Gas Networks Ireland’s CEO, Cathal Marley says:

“We believe it is important that the National Hydrogen Strategy recognises how Ireland’s modern gas network can be leveraged to accommodate hydrogen produced from wind energy, as well as acknowledging that during this transition, natural gas will continue to be needed to ensure continued security and resilience of Ireland’s energy system.

“The gas network is Ireland’s hydrogen-ready infrastructure and reliable energy backbone, which will substantially reduce the country’s carbon emissions and play a vital role in establishing our future hydrogen economies.”

Repurposing

the gas network for hydrogen

David Kelly, Director of Customer and Business Development at Gas Networks Ireland. The gas network is the cornerstone of Ireland’s energy system, securely supplying more than 30 per cent of Ireland’s total energy, including 40 per cent of all heating and almost 50 per cent of the country’s electricity generation.

The cost of repurposing the existing gas network to transport hydrogen is estimated to be a fraction (10 per cent to 35 per cent) of the cost of building new dedicated hydrogen pipelines.

Gas Networks Ireland’s Director of Customer and Business Development, David Kelly, says: “As the gas pipelines are already in the ground, it is the least disruptive option also.

“Replacing natural gas with renewable gases, such as hydrogen, will substantially reduce the country’s carbon emissions by supporting our large industrial customers on their net zero journeys while also complementing intermittent renewable electricity and ensuring a more diverse and secure energy supply.

“We have been working diligently for an extensive period of time on preparing the existing gas network to accept hydrogen and natural gas blends from the UK, as well as preparing for the injection of indigenously produced green hydrogen at appropriate locations into the gas network. Results from our studies indicate that our network will be ready. We are confident that we will be in a position to onboard hydrogen as and when our industry partners are ready to produce the renewable gas.”

The return of geopolitics: Consequences for energy policy

the University of Warwick and co-chair and co-founder of the European Consortium for Political Research (ECPR) Research Network on Energy Politics, Policy, and Governance, speaks to eolas Magazine about how energy policymakers have responded to the Russian invasion of Ukraine.

It is, Kuzemko says, “self-evident” that we are now interpreting the world as one where geographic borders “matter a bit more”, there is a “little bit more competition” and a “little bit less cooperation” between countries in the wake of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and the subsequent scramble to secure national energy futures. Not least, as outlined in the research paper, Russia's war on Ukraine, European energy policy responses and implications for sustainable transformations, published by Kuzemko and colleagues, as the EU’s REPowerEU strategy pledged to wean Europe off of its reliance on Russian fossil fuels.

“We think of energy policy as being set to meet multiple goals,” she says. “Historically, through the start of the last century when inanimate forms of energy became so important for modern living, security was obviously the goal. In the post-war period, the question of access and energy equity became increasingly important. In

the latter part of the last century and the beginning of this century, sustainability gained an increasing foothold on energy policy agendas and now is a firm goal of energy policy.

“I would suggest that the question of social justice has now added another dimension to energy policy. The question of who governs, whose voices are represented, and who is involved in the generation of energy have become important because renewables, given their distribution, change this up. It is in the balancing of these goals that we will be able to deliver lasting change, where citizens are bought in, engaged, and become part of the process will be key to keeping climate mitigation on political agendas.”

Energy security has returned to the fore as the main concern as EU member states have cut their supplies of Russian fossil fuels, an “immense task”. “I find it interesting as an academic that we are so used to historically

“We are so used to historically thinking about producer nations wielding the energy weapon, but we have seen the EU turn that on its head a bit and use demand reduction as a policy tool.”

Caroline Kuzemko, University of Warwick

thinking about producer nations wielding the energy weapon, but we have seen the EU turn that on its head a bit and use demand reduction as a policy tool,” Kuzemko says. “The focus on reducing fossil fuel imports from Russia has meant an increase in EU joint gas storage, an uptick in acting with solidarity – which has been a real issue because member states have wanted to hold onto national control of energy traditionally.”

The move away from Russian fossil fuels has led to a diversification of supplies, with new infrastructure being built in Europe to facilitate the importation and regasification of LNG from the US, for example. “Most interesting”, Kuzemko says, is the “rethinking of the place of renewables”.

“Those of us who have been thinking about climate change for a while now will be familiar with arguments that renewables are less reliable and resilient, but this re-emphasis on homegrown energy and energy independence means that renewables are now seen as a solution on both the sustainability and security sides,” she says.

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change has stated that global emissions must peak by 2025 and reduce by 43 per cent by 2030 if current climate goals are to be met, a “tall and urgent order” that Kuzemko says has had interesting implications for energy policy and sustainability.

“Clean energy and energy saving are two of the pillars underpinning REPowerEU and there have been some great success stories there and some quite huge revisions of North Sea wind targets that are very interesting. I particularly noted in terms of encouraging more investment in renewables the temporary relaxation of state aid rules in the EU and on the planning side, the notion of renewables as being in the overriding public interest,” she says.

“On the demand side, the decision to put in a mandatory target to reduce electricity demand at peak times was very innovative. Obviously, this was temporary, and it ended in March 2023, but it will be interesting to see if it the kind of thing that happens again in winter 2023/2024 and further out, because a smaller electricity system is a cheaper one.”

While there have been positives in boosting the production of clean energy, Kuzemko states that the complications have come in the phasing out of fossil fuels and the knock-on effects of Europe’s increasing consumption of LNG.

“A completely unintended knock-on consequence of the EU entering into global LNG markets in a much larger sense has meant that there has been less LNG available for developing economies, some of which have been priced out of the market,” she states.

“In some developing economies like Pakistan and Sri Lanka, where the move towards gas to replace coal was being made, there has now been a move back towards coal. In China’s 2023 strategy, for the first time in a long time, there was real emphasis on coal on security grounds. This clearly poses questions about emissions.

“To get the world to net zero or the 1.5oC target, everybody must be involved, and by that, I mean all countries in the world. In terms of energy equity, there are implications tied up in keeping the lights on in Europe. There is also the question of equity in terms of the allocation of unburnable carbon; it has been agreed at UN COPs that certain parts of the world, mainly the global north, are more responsible for emissions and have more capability to bring those emissions down. Research around the equitable allocation of unburnable carbon suggests that it should favour the global south, but what we have been seeing is the UK and Norway increasing output and using what is going on at the moment to announce new extraction plans for oil and gas.”

Concluding, Kuzmemko reflects on how “social justice has been part of what the EU has been doing in energy policy” and how measures such as the 2019 Clean Energy Package included provisions for more public engagement and more bottom-up cultivation of sustainable energy such as solar panels. “I find it very interesting that, at the Commission and member state level, there is clear commitment – and this may be a continuation of the Covid crisis – for governments to step in and deliver social goals and also now to deliver on sustainable energy,” she says.

Bord Gáis Energy welcomes National Hydrogen Strategy

Bord Gáis Energy has welcomed the publication of the Government’s recently published National Hydrogen Strategy as a keystone to Ireland becoming a green-energy powerhouse.

The National Hydrogen Strategy sets out the Government’s vision for how hydrogen will be produced and used in Ireland and outlines how green hydrogen can help Ireland become a zerocarbon, secure energy system and an energy exporter. A key objective of the strategy was to provide certainty to investors and industry as to how hydrogen will be deployed in the Irish energy system. Bord Gáis Energy welcomed the signals to industry in the report.

Bord Gáis Energy, which was purchased by Centrica in 2014, strongly believes that green hydrogen is a keystone to Ireland becoming a clean, green-energy powerhouse, and is investing €300 million in the construction of two hydrogen-capable power generation plants, which will be ready to support the grid at the end of 2024.

Emma Burrows, Legal, Regulation and Corporate Affairs Director at Bord Gáis Energy said: “We welcome the Government’s significant efforts to embrace green hydrogen as a safe and secure energy solution. Ensuring that industry is provided with the necessary certainty to inform future investment strategies is vital if Ireland is to unlock the potential that green hydrogen presents.

“At Bord Gáis Energy we plan to deploy our significant expertise in engineering, innovation, and energy to support these plans. Centrica’s UK trials in the hydrogen sector bring significant learning opportunities and have enabled our teams to identify the areas where this technology can be effectively implemented in Ireland.

“We are working with other like-minded investors

The Minister for the Environment, Climate and Communications, Eamon Ryan TD, joined by Meadhbh Connolly, Future Opportunities Manager, ESB Generation and Trading; and Gillian Kinsella, Senior Policy Manager, Bord Gáis Energy and Co-Chair, Policy and Advocacy Working Group, Hydrogen Ireland at the launch of the National Hydrogen Strategy.

“Bord Gáis Energy is currently investing €300 million over 24 months in hydrogen-capable infrastructure.”

Hydrogen facts and figures

• Ireland has potential for up to 90TWh of hydrogen production according to the Sustainable Energy Authority of Ireland. For context, the current gas network provides 74TWh of gas supply on the island of Ireland to 720,000 customers.

• Ireland’s demand for hydrogen is estimated to be in the region between five and 39TWh for domestic demand and between 20 and 75TWh for total demand by 2050.

• The Irish Government has set a target of 2GWs of offshore wind to use for hydrogen production and to deliver between one and three TWh of renewable gas (including hydrogen) by 2030.

• Ireland needs approximately 20TWh of dispatchable generation by 2050. Green hydrogen can provide a route to decarbonise this dispatchable generation that is needed in periods of low wind/solar.

• Gas Networks Ireland is currently assessing the potential for hydrogen to be blended in the gas grid, initial results are promising, and the hope is that the gas grid can accommodate blends of up to 20 per cent hydrogen volume without the need for significant adjustments.

seeking to deliver Ireland’s net zero ambitions to create an indigenous cluster that will use Ireland’s natural resources off the southwest coast to provide an abundant, flexible, and secure zero carbon energy source that can be used across Irish society and beyond. Indeed, Government’s recent Joint Declaration of Intent on cooperation in the field of green hydrogen with Germany demonstrates that green hydrogen has the potential to meet not just Ireland’s but Europe’s growing green-energy needs.”

Gillian Kinsella, Senior Policy Manager, Bord Gáis Energy and Co-Chair, Policy and Advocacy Working Group, Hydrogen Ireland said: “The publication

of the Government’s National Hydrogen Strategy outlines the strategic pathway for hydrogen’s role in decarbonising our economy, enhancing our energy security, and creating industrial and export market opportunities. It will enable investment, increase skills, support regionally balanced economic growth and system resource efficiencies, thus providing a crucial pathway for delivering a future that will benefit the Irish people for generations to come.”

For further information visit bordgaisenergy.ie

Decarbonising Ireland’s heat demand

Barry Quinlan, Assistant Secretary, Energy – built environment, retrofit and heat policy at the Department of the Environment, Climate and Communications, speaks to eolas Magazine about government priorities in the decarbonisation of heat demand.

Setting the context for his responsibilities and the immediate pressure under which he operates, Quinlan states that when threatened, for example by the war in Ukraine, “security of supply and affordability, trump everything else”, pointing to his work on 2022’s electricity credit, ensuring that the country had requisite diesel levels, and making market adjustments to ensure access to fossil fuels. “It is about making sure people can heat their houses,” he says.

However, Quinlan outlines that the decarbonisation of the heating of houses will be a major part of the State’s push towards net zero by 2050, with the overall policy context dictated by the Climate Action Plan. “Chapter 14, Built Environment, is how we are going to decarbonise our

buildings,” he says. “We have done a lot of work on new buildings and the standards. In my old department [the Department of Housing, Local Government and Heritage], they are very, very strong. People buying houses now are buying Arated houses with heat pumps primarily, but it is a completely different story for older homes which are on oil and gas. That is the big thing we have to change.”

District heating

This change will be governed by the currently progressing National Heat Policy, which is “working through the system at the moment”, and its emphasis on electrification and district heating. In the case of district heating, Quinlan acknowledges that “we do not do [that] at any scale here yet, but we know it

works well in Europe”. “The great thing about district heating is that when you have one source of heat for multiple buildings, as is the rationale for changing our heating source, you can do that,” he elaborates.

The National Heat Study highlighted progress in the area of heat pumps but said that district heating still requires significant work. “District heating needs to be focused on a district or a part of a large town or city,” Quinlan says. “We have brought together good people from the system: planners, regulators, finance, and local authorities which have already done district heating here, looking at the delivery model at scale.

“We are going to need major district heating projects in all of our cities as a start. At the moment, the primary delivery model is a co-operative model based on local authorities, which certainly has its merits, but to do it at scale, we can see from countries which have done this that it requires a mix of public and private.”

Heat and Built Environment Taskforce

A number of taskforces have been set up by Minister for the Environment, Climate and Communications Eamon Ryan TD, with Quinlan chairing the Heat and Built Environment Taskforce, whose members include nine government departments, Enterprise Ireland, the HSE, the local authority City and County Managers’ Association, IDA Ireland, the Office of Public Works, SEAI, and Teagasc.

Quinlan states that the membership of the HSE is especially important, given that the executive owns 4,500 of the circa 11,500 public buildings in the State. The membership of the Department of Agriculture, Food and the Marine allows for “a lot of work” to be done on biomethane, and the area of residential retrofit – where Quinlan acknowledges “a huge job” – is also being covered.

“The taskforce is bringing all sorts of people together from different departments,” Quinlan says. “We also have subgroups covering industry. Industry has a big job to do in terms of heat, processes, and also buildings. We have the public sector, and the public sector has to be a leader. We have to formulate a policy there which works over time, particularly to retrofit our buildings.”

“We have brought together good people from the system: planners, regulators, finance, and local authorities which have already done district heating here, looking at the delivery model at scale. We are going to need major district heating projects in all of our cities as a start.”

Barry Quinlan, Assistant Secretary, Energy – built environment, retrofit and heat policy at the Department of the Environment, Climate and Communications

Renewable heat

Another major focus for Quinlan is the Renewable Heat Obligation, and the taskforce is playing a role in this regard by participating in the formulation of a biomethane strategy. “A key part of it is building that whole business model to make those projects work,” he says. “We are looking at biomethane and anaerobic digestion with not only a link to agriculture, but the key parts are around feedstock and how you feed this over time. The other bit is being able to offload the energy efficiently at the end. That is the whole piece around the Renewable Heat Obligation, and we will be going out to consultation.”

Some “incredible schemes” are being run through SEAI’s Industry programmes in this regard, Quinlan says, pointing to a recent trip to a large industry network in a “major facility” in Tipperary as an example. “It was incredible; a big solar farm, working towards a massive heat pump, going to use the excess energy that will deliver from offshore wind,” he says.

“They are all moving in this direction; it is coming from their own boardrooms. They are looking for the Irish regulatory regime and how we support them. We do not have to ask them to go on this journey, those decisions have been made and the decarbonisation is just as high a KPI as profit at boardroom level.”

Quinlan also makes note of “improvements” made to the “very generous” Renewable Heat Incentive Scheme and reaffirms the Government’s commitment to it, despite admitting that the process has been “difficult”. This contrasts with the National Retrofit Plan, where “huge progress” is being made according to Quinlan, much like the rollout of heat pumps. “Huge amounts of people have to make those decisions,” he says. “It is a big intervention, and it is not a well understood technology for people that are in existing homes. New homeowners are very familiar with it now.”

Concluding on a positive note, Quinlan focuses on the success of the retrofit scheme as evidence of the progress being made towards weaning Irish domestic heat off oil and gas: “We doubled the amount of money spent. 27,200 upgrades is 80 per cent up on the year before; that tells its own story.

“Heat is one of the last big challenges that Ireland needs to get on top of. We are preaching to the converted when it comes to industry. We are going to have to bring homeowners and others with us and make sure that the transition is just.”

Paving the way for a just transition: The role of renewable gas in Ireland’s future

In the pursuit of a sustainable future, Ireland stands at a crossroads, facing the challenges of combating climate change while ensuring an equitable transition for everyone, writes Duncan Osborne, Chief Executive Officer of Calor Ireland.

As the world collectively strives to achieve netzero carbon emissions, it is imperative that the transition be just and fair, leaving no one behind.

Renewable gas emerges as a crucial player in this journey, offering a unique avenue to address both environmental concerns and social equality, particularly for rural off-grid gas customers. We know that the current ‘one size fits all’ approach to retrofitting homes is not working – the figures tell us so.

The uptake of grants available for deep retrofitting and heat pump installation through the National Home Energy Upgrade Scheme, is lower than anticipated, particularly in rural areas. For the Irish Government to hit its target, 62,500 houses need to be retrofitted annually.

The future vision: navigating Ireland's transition

Ireland's commitment to a net-zero future by 2050, as outlined in the Climate Action Plan, underscores the nation's dedication to

combatting climate change. To achieve this ambitious target, Ireland must optimise its energy mix and ensure a mixed technology approach with wider choice of viable options for homes and businesses off the natural gas grid.

According to recent figures for the SEAI’s Better Energy, Warmer Homes Scheme, 603 homes were provided with a heating system upgrade in the first half of 2023. The Scheme provides free energy efficiency upgrades for eligible homes, and the aim of the Scheme is to make eligible homes warmer, healthier, and cheaper to run.

Of those 603 homes that underwent energy efficiency upgrades, only 20 installed a heat pump, while 348 were refitted with gas boilers. Retrofitting and installing a heat pump is a costly process, requires additional insulation actions, and requires many homeowners to vacate their premises when certain works are required. For many, this just is not feasible.

For these homeowners, switching to a renewable ready gas boiler that caters for lower

carbon LPG, BioLPG or a blend of both, would have an immediate and lasting impact on reducing carbon emissions.

It is clear from these figures that it is vital that homeowners have a suite of energy efficiency upgrade solutions available to choose from, or they may choose inaction.

A just transition

One of the defining principles of Ireland's approach to the transition is the commitment to a just transition, ensuring that vulnerable communities and individuals are not disproportionately burdened by the changes necessitated by climate action.

We know from a recent report by Liquid Gas Ireland (LGI), the association representing companies operating in the LPG and BioLPG industry in Ireland, of which Calor Ireland is a member, that 65 per cent of properties located off the gas grid rely on oil as the energy source of choice for home heating while others rely on high carbon traditional fuels such as coal and turf.

Integrating LPG, BioLPG, and rDME (renewable dimethyl ether) into the energy solution means ensuring that those living in rural dwellings have the same options to decarbonise as those in urban settings.

Calor Ireland has been at the forefront of this journey by introducing BioLPG, a certified renewable gas, in 2018. Alongside our parent company SHV Energy, Calor is making strides in developing, investing in, and growing Futuria, our sustainable fuels portfolio.

Innovation and collaboration

The journey towards net zero and a just transition requires innovation and collaboration at every level. The government, private sector, academia, and local communities must work in tandem to drive technological advancements and enhance the efficiency of renewable gas production and distribution.

As a leading global distributor of LPG and LNG, SHV Energy – Calor Ireland’s parent company –invests in research and development to find novel ways to produce sustainable fuels such as BioLPG, BioLNG, rDME, hydrogen, and other sustainable ‘future’ fuels. Innovation is considered essential to realise these goals.

Developing and investing in a range of fuel sources will ensure that measures are being applied across all sectors in society. Transport, for example, is one of Ireland’s major causes of pollution, and sustainable fuels such as BioLPG are being used in our forklift truck cylinders to support the decarbonising of the logistics sector, as well as contributing to the Government’s Biofuels Obligation Scheme targets.

Calor will continue to invest in developing sustainable energy solutions to enable consumers to make lower carbon choices. We are fully committed to bringing a full range of solutions to market, but our consumers need to be supported to decarbonise, if the just transition is to genuinely mean what it says.

Calor urges the Government to develop a regulatory environment which supports the use and availability of renewable liquid gases to meet the energy needs of rural Ireland. Integrating LPG, BioLPG, and rDME into current and future Government policy will help to ensure a mixed technology approach and wider choice of viable options for homes and businesses off the natural gas grid.

T: 1850 812 450 W: www.calorgas.ie

Published in July 2023, the National Hydrogen Strategy is the Government’s first major policy statement on renewable hydrogen and is aimed at increasing certainty and reducing commercial risk to drive private sector investment.

The strategy explores the opportunity for Ireland, hydrogen production, enduses, transportation, storage, and infrastructure, alongside safety and regulation, research, cooperation, and scaling. In addition, it determines Ireland’s strategic hydrogen development timeline, seeking to “provide clarity on the sequencing of future actions needed and guide our [the Government’s] work over the coming months and years”.

Outlining the rationale for developing an indigenous hydrogen sector in Ireland, the National Hydrogen Strategy identifies three primary policy drivers:

1. Decarbonising the economy

Ireland requires a radical transformation of its entire economy if it is to achieve net zero emissions no later than 2050. Indigenously produced renewable or green hydrogen can play a significant role in this transformation, with its potential to be a zero-carbon alternative to fossil fuels in hard to abate sectors of the economy. This includes those in which electrification is unfeasible or inefficient.

National Hydrogen Strategy published

Long awaited by many in the energy sector, the National Hydrogen Strategy was launched by Minister for the Environment, Climate and Communications and Minister for Transport, Eamon Ryan TD, aboard a hydrogen-fuel-cellelectric double-deck bus.

2. Enhancing energy security

Ireland imports around three-quarters of its energy supply annually. However, by harnessing one of the world’s best offshore renewable energy resources and using the surplus to produce renewable hydrogen, Ireland has an opportunity to reduce reliance and potentially achieve energy independence. While fossil fuels are utilised as a backup to renewable energy sources, renewable hydrogen could become a zero-carbon replacement. As per the National Energy Security Framework, hydrogen is highly energy dense and, therefore, suited to the development of seasonal storage solutions at scale, helping to mitigate variability and seasonal demand.

3. Creating industrial and export market opportunities

In the long term, Ireland has the potential to produce excess renewable energy, including hydrogen. At the same time, many European countries have identified a long-term demand for renewable carbon imports to meet decarbonisation ambitions. As such, the establishment of an export market could be beneficial to the domestic development of renewable hydrogen.

In the short term, the National Hydrogen Strategy establishes a series of actions aimed at enabling the development of Ireland’s hydrogen strategy. The

strategy aims to removal obstacles which could inhibit hydrogen projects while enhancing knowledge through targeted research and innovation.

Established in 2020, the Interdepartmental Hydrogen Working Group is tasked with monitoring the delivery of these actions, while identifying further actions to support progress as the sector evolves.

Combining long-term ambitions with 21 short-term actions, the National Hydrogen Strategy aims to:

• kickstart and scale up renewable hydrogen production;

• identify end use sectors, supply chains, and required quantities;

• determine what infrastructure is needed;

• ensure the implementation of rules around safety, sustainability, and markets; and

• establish conditions which foster continued technological advancement and innovation.

Minister

In his foreword to the National Hydrogen Strategy, Minister Ryan asserts that alongside other decarbonised gases, renewable or green hydrogen will have a key role to play in Ireland’s energy transition. Describing hydrogen as a “major opportunity for Ireland”, he contends: “It provides the potential for long-duration energy storage,

Hydrogen Strategy

Actions to be delivered through the implementation of the National Hydrogen Strategy

Number: Action:

1 Develop and publish data sets showing the likely locations, volumes, and load profile of surplus renewables on the electricity grid up to 2030.

2 Establish an initial hydrogen innovation fund to provide co-funding supports for demonstration projects across the hydrogen value chain.

3 Adopt EU standards for renewable and low carbon hydrogen and develop a national certification scheme to provide end users with clarity as to the origin and sustainability of hydrogen.

4 Develop the commercial business models to support the scaling and development of renewable hydrogen, via surplus renewable electricity until 2030 and an initial 2GW of offshore wind from 2030.

5 Develop a roadmap to bring net zero dispatchable power solutions to market by 2030, supporting the establishment of a near net zero energy system by 2035.

6 Assess the role that integrated energy parks could play in the future energy system, including potential benefits and barriers.

7 Publish the draft National Policy Framework on Alternative Fuels Infrastructure and support the roll-out of hydrogen fuelled heavy vehicles and refuelling infrastructure as per the recast Renewable Energy Directive and Alternative Fuel Infrastructure Regulation.

8 Assess the feasible potential for end uses such as eFuels, decarbonised manufacturing, and export via the development of a National Industrial Strategy for Offshore Wind.

9 Determine the quantities and profile of zero carbon long duration energy storage required up to 2050 and develop a roadmap for its delivery.

10 Review the existing licensing and regulatory regimes relevant to the geological storage of hydrogen, progress the necessary legislative changes, and develop regulatory regimes to facilitate future prospecting and development of underground hydrogen storage solutions.

11 Continue to prove the technical capabilities of the gas network to transport hydrogen while working closely with network operators in neighbouring jurisdictions in respect to interoperability between the networks.

12 Develop a plan for transitioning the gas network to hydrogen, duly considering plans to develop a biomethane sector in Ireland; the prioritisation of end uses set out in the National Hydrogen Strategy and their likely locations where known; the need to maintain energy security through the transition; how existing end users can transition from natural gas to hydrogen or alternative energy solutions such as electric heating; and the potential use of hydrogen blends during a transition phase, associated costs, and how the transition from blending can occur.

The plan should look to identify where the network can be repurposed, or where new pipelines may be required, providing detailed costings and a programme of works.

13 Identify and support the development of strategic hydrogen clusters.

14 Review current approaches to energy systems planning and make recommendations to support a more integrated long-term approach across the network operators.

15 Establish a working group comprising relevant regulators, government, and industry representatives to develop a roadmap for delivering the necessary safety frameworks and regulatory regimes across the entire hydrogen value chain.

16 Adopt the hydrogen and decarbonised gases market package into legislation once approved by the EU.

17 Review the entire hydrogen value chain to identify any gaps within the spatial planning, environmental permitting, and licensing regimes.

18 Engage with Ireland’s research sector to ensure sufficient focus is given to renewable hydrogen development and commission relevant research to help close the knowledge gaps identified throughout the National Hydrogen Strategy.

19 Continue engagement in EU hydrogen related initiatives and develop cooperation in renewable hydrogen development with neighbouring jurisdictions and international partners.

20 Continue to assess, and support the future skill needs of the offshore wind and renewable hydrogen sectors via the expert advisory group on skills established under the Offshore Wind Delivery Task force.

21 Review and update the terms of reference of the Interdepartmental Hydrogen Working Group in recognition of its role in oversight and implementation of the National Hydrogen Strategy.

2024-2027

2024-2026

2023-ongoing

2023-2024

dispatchable renewable electricity, the decarbonisation of some parts of hightemperature processing, as well as a potential export market opportunity.”

However, the Minister makes clear that the deployment of hydrogen technologies must be optimised to deliver the most efficient or advantageous solution.

“Hydrogen provides us with an incredible opportunity in Ireland, but its use must be targeted to the uses where it will deliver the greatest benefits. We must not become distracted by the possibility to deploying hydrogen technologies where direct electrification would deliver a better outcome,” he writes.

End-uses

Renewable hydrogen deployment, the new strategy asserts, will centre on hard to abate sectors where direct electrification and energy efficiency measures are unfeasible or cost ineffective. Meanwhile, heavy transport applications bound by EU targets for 2030 are expected to be the first end-use sectors to emerge, quickly followed by industry and flexible generation.

While identified as significant highpriority end-users, the aviation and maritime sectors will take longer to develop. Indeed, given the uncertainties which exist in demand projections, it is thought that domestic hydrogen demand could range between 4.6 TWh and 39 TWh by 2050, increasing to 19.8 TWh and 74.6 TWh when including non-domestic energy needs such as international aviation and shipping. Consequently, more research is required to determine a better understanding of the potential demand of end-use sectors, as well as the role that renewable hydrogen will play in an integrated net zero energy system.

In order of priority, the strategy lists 11 envisioned hydrogen end-uses:

1. Existing hydrogen end-users: Renewable hydrogen will replace niche grey hydrogen uses with a likely market entry timeframe of 2025-2030.

2. Flexible power generation and long duration energy storage: Net zero flexible backup generation and long duration energy storage with a likely market entry timeframe of 2030-2035.

3. Integrated energy parks for large energy users: As a backup to renewable electricity to meet reliability needs with a likely market entry timeframe of 2025-2030.

4. Industrial heat and processing: For high temperature heating and processing needs with a likely market entry timeframe of 20302035.

5. Aviation: As a zero-carbon synthetic fuel alternative to jet fuel with a likely market entry timeframe of 2035-2040.

6. Maritime: As a zero-carbon fuel (e.g. ammonia) with a likely market entry timeframe of 2035-2040.

7. Road and rail transport: For longrange road transport requiring long duty cycles and rail where electrification is unfeasible with a likely market entry timeframe of 2025-2030.

8. New non-energy uses: Such as fertiliser production and other chemical processes not currently undertaken in Ireland.

9. Export: Renewable hydrogen production exceeding domestic demand with a likely market entry timeframe of 2035-2040.

10. Blending: As a mitigation solution for end use variability and excess production with a likely market entry timeframe of 2023-2030.

11. Commercial and residential heating: In niche areas where electrification is unfeasible with a

Hydrogen explainer

likely market entry timeframe of 2035-2040.

Blending

Acknowledging a Gas Networks Ireland technical and safety feasibility study that determined transporting blends of hydrogen and natural gas via the gas network was both safe and feasible, the strategy recognises that “blending may offer an initial demand sink in the short term”. Notably, however, it concludes: “Overall, blending is not seen as a high priority end-use for renewable hydrogen.”

Commercial and residential heating

Similarly, the strategy indicates: “Hydrogen is not expected to play a role in commercial and residential space heating.” Rather, a combination of energy efficiency measures, direct electrification via heat pumps, and district heating are identified as “more efficient and cost-effective solutions” for the commercial and residential heat sector. Overall, the strategy contends that hydrogen will play a role in a small number of niche end use cases in commercial and residential heating which will “likely be required to work in parallel with energy efficiency measures such as hybrid heating systems where possible”.

Transportation, storage, and infrastructure

Ahead of hydrogen pipelines becoming the dominant mode of transportation, early hydrogen applications are anticipated to employ compressed

Hydrogen is most commonly chemically bonded to other elements, especially water (H2O) and hydrocarbons (CxHx). Hydrogen production relies on the chemical bonds between elements such as water to be broken, and the hydrogen separated and stored. This process requires an energy input, usually electricity or heat, the source of which, allied to the resulting byproducts, determines the carbon intensity of the production process.

Globally, most hydrogen is currently produced using hydrocarbons and in the absence of emissions abatement of the carbon byproduct. Grey hydrogen production is carbon intensive and unsustainable.

Electrolysis of water utilises electricity to split the molecule into hydrogen with oxygen as the byproduct. If the electricity used is generated via a renewable source, such as offshore wind, the resulting high purity hydrogen has no associated emissions and is therefore renewable or ‘green’ hydrogen.

tankering solutions. Initial infrastructure is expected to be concentrated in regional clusters with co-located production, high priority demand, and large-scale storage. Subsequently, as the hydrogen market matures, these clusters will be linked in a national hydrogen network, repurposing existing natural gas pipeline infrastructure where feasible.

To date, the gas network has proven technical capability to transport hydrogen blends of up to 100 per cent. However, the strategy suggests that more work must be undertaken to better understand “the costs, phasing of transition, and potential impacts for existing network users”.

Meanwhile, long duration storage via geological solutions will be essential to ensure the cost effectiveness and price resilience of hydrogen supply.

Simultaneously, allied with network infrastructure, storage will be crucial in ensuring security of supply. Commercial ports, interconnection, and import/export routes will be vital to the establishment of a hydrogen economy in Ireland, and the longterm planning must identify the infrastructure requirements of an integrated net zero energy system.

Long-term vision

Recognising, that renewable hydrogen is a nascent technology with much uncertainty around costs, end-uses, infrastructure, skills, and supply chains, the National Hydrogen Strategy seeks to provide a long-term vision for hydrogen in the Irish economy.

Ultimately, the strategy outlines, the proportion of onshore and offshore renewable energy dedicated to the production of renewable hydrogen “will eventually be determined by the market”. Though the delivery of sufficient renewable energy to both meet indigenous demand and enable export opportunities hinges on optimising the offshore renewable energy potential.

Commentary

Broadly welcomed by academia and industry alike, eolas Magazine spoke with several of Ireland’s hydrogen experts to gauge their reactions to the National Hydrogen Strategy.

Rory Monaghan, lecturer of mechanical engineering, College of Engineering and Informatics, University of Galway:

“Overall, the published hydrogen strategy is a great start. It delivered much more than I thought it would. The drafters really took the results of the public consultation seriously and have produced a very impressive document.

“Of particular note are the identification of end-use sectors and realistic timelines for hydrogen deployment in them. I am very happy to see heavy duty transport and public transport feature.

“The key next step for the sector is for the demo project fund to get established as quickly as possible so it can start dispersing support for projects. The commercial and research communities are ready to go.”

James Carton, assistant professor in sustainable energy, Dublin City University:

“Speaking with colleagues, we are quite impressed by the strategy. It is a nice piece of work. Both nationally and internationally, it has been well received. I have received positive feedback from my colleagues in academic, the public sector, and the private sector across Europe, the UK, and Ireland.

“It is a good document that sets out what Ireland is doing well, and that the interest mainly lies in hydrogen production and integrating it with renewable energy. It allows casts a light on some gaps which exist. One of the big gaps that it has identified is in end-use.

“There is a list of 21 actions, and each is very good; they all need to be actioned by the relevant bodies. Meanwhile, the Government has explicitly said that it is going to undertake pilots to learn, upskill, cultivate the knowledge and experience in the industry before building more larger scale projects.

“Government must quickly action the early points made in the action list of the National Hydrogen Strategy, while in parallel get going on ticking off these pilot projects so that we can enhance our experience and knowledge.”

Gillian Kinsella, co-chair of the policy and advocacy working group, Hydrogen Ireland:

“Hydrogen Ireland welcomes [the] release of the Government’s Hydrogen Strategy. The strategy marks a key milestone in the development of a green hydrogen sector in Ireland, one which can enable investment, increase skills and support regionally balanced economic growth. We look forward to supporting the implementation of the strategy in future to aid Ireland’s transition to a secure, net zero economy.”

Emissions reductions for industry: Lessons from Germany

Paul Münnich, Project Manager for Agora Industry, outlines the scale of the challenge in decarbonising the industrial sector in Germany.

Münnich contextualises that the German energy sector is currently in a state of relative flux, with the use of coal-powered energy having seen a short-term uptick in the aftermath of the Russian invasion of Ukraine and reducing the German supply of natural gas. Prior to the invasion, Germany had a significant reliance on the use of natural gas imported from the Russian Federation, amidst the German phase out of nuclear power.

Therefore, Germany has had to adapt to an energy market with a much-reduced supply of natural gas and has utilised carbon-heavy sources as a medium-term solution. With the increased use of coal, Germany, in spite of having one of the highest rates of renewable energy sources in Europe, has a higher carbon intensity than European countries such as the UK, France, and Spain.

Münnich and his organisation, Agora Industry, have carried out the Power-2-heat study, which examines how best to maximise efficiency in German industrial heating systems.

Killing two birds with one stone

Münnich explains that “after the energy sector, industry is the second largest emitter of greenhouse gas emissions”.

“In Europe, industry accounts for 24 per cent of all greenhouse gas emissions. Of this 24 per cent, roughly two-thirds can be attributed to the supply of power and heat, but the boundary conditions for the industrial transition are already set by the very ambitious ETS framework that the EU set in place.

“With the latest reform of the EU ETS, industry needs to be climate neutral by 2040. That gives us 16 years for the transformation, which is really not a lot for the big task we have ahead of us.”

Münnich adds: “In Germany, process heat accounts for 22 per cent of final energy demand and one-fifth of that process heat demand is still being met with coal, whilst the majority (41 per cent) comes from natural gas.

“The supply of power and heat in industry, accounted for 24 per cent of natural gas consumption in Germany, which is a lot, and much of the natural gas we used to use for industry in Germany came from Russia. Therefore, with the study we tried to find a good balance and an opportunity to kill two birds with one stone: reduce emissions and also reduce natural gas consumption.”

“To quickly reduce emissions and dependence on natural gas in this decade, electrification is a key lever.”

Paul Münnich

Three levers

“The biggest lever for reaching climate neutrality,” Münnich states, “is the deployment of renewables”. “Of course, we still have to get faster, however, we have already achieved quite a lot, for example, in 2022, 83 per cent of all new power generators globally were renewable which, I would say, is quite impressive.

“The second and third levers touch upon the issue of heat; we have to switch from fossil to renewable heat sources and increase energy efficiency. In residential heating, we already see quite a lot of improvement. For example, in Europe sales of heat pumps have increased by roughly 100 per cent since 2019.

“I think this is the right way to go and the upward trend is continuing. The industrial heat transition has not reached that speed; it needs more momentum and it needs more political priority if we want to reach our targets.”

Hydrogen and heat pumps

“In the end, we will have to use a lot of renewable electricity for climate-neutral heat in industry. Often, hydrogen is at the centre of the debate, despite its high energy intensity and cost,” Münnich states. “Hydrogen is very versatile energy carrier and can be used in many different applications like producing steel and chemicals, however, producing renewable hydrogen is very energy intensive. Providing one kWh of heat using renewable hydrogen requires over 1.5 kWh of renewable electricity to produce the hydrogen. So, wherever we can find a

better solution which requires less electricity, we should try to opt for that.”

As more efficient alternatives to the use of hydrogen, Münnich notes “electric boilers and large-scale industrial heat pumps are some of the many technology solutions for electrifying heat”. “Our analysis shows that hydrogen uses a lot of electricity whilst heat pumps can provide the same amount of energy with just a fraction of the electricity and the use of low temperature industrial waste heat or environmental heat, so this should really be the focus.”

However, Münnich also believes that “we will need more flexible demand”. “The electrification of industrial heat means that we cannot meet our heat demand in a base load pattern, but we should use renewable electricity when there is a lot of renewable electricity in the grid. When there is little power production by solar and wind we should try to reduce our load as much as possible, for instance by using heat storage technologies.”

Action to be taken

Münnich concludes that there is a need to phase out all fossil fuel usage for heat below 500oC before 2035 to help achieve climate goals.

“We have strategies for hydrogen and the circular economy but not yet for electrification. To quickly reduce emissions and dependence on natural gas in this decade, electrification is a key lever. That is why we also need an electrification strategy.”

Gas needed as transition fuel

Ireland’s lack of energy security is topical, and selfsufficiency is an area of particular weakness. While a government decision to end the issuing of new licences for gas exploration was clearly founded in the policy of transitioning to renewable energy, the reality is that gas is required as a transition fuel, writes William Holland, CEO of Europa Oil & Gas.

Currently, Ireland relies heavily on the UK for its gas supply and will do for the foreseeable future unless the government can create an environment where foreign direct investment (FDI) feels welcomed to invest in Ireland and fund the further development of its plentiful domestic gas resources. Although existing exploration licences are permitted to continue, the policy to end the issuing of new licences has sent the opposite signal from a country where FDI is a cornerstone of its economic development.

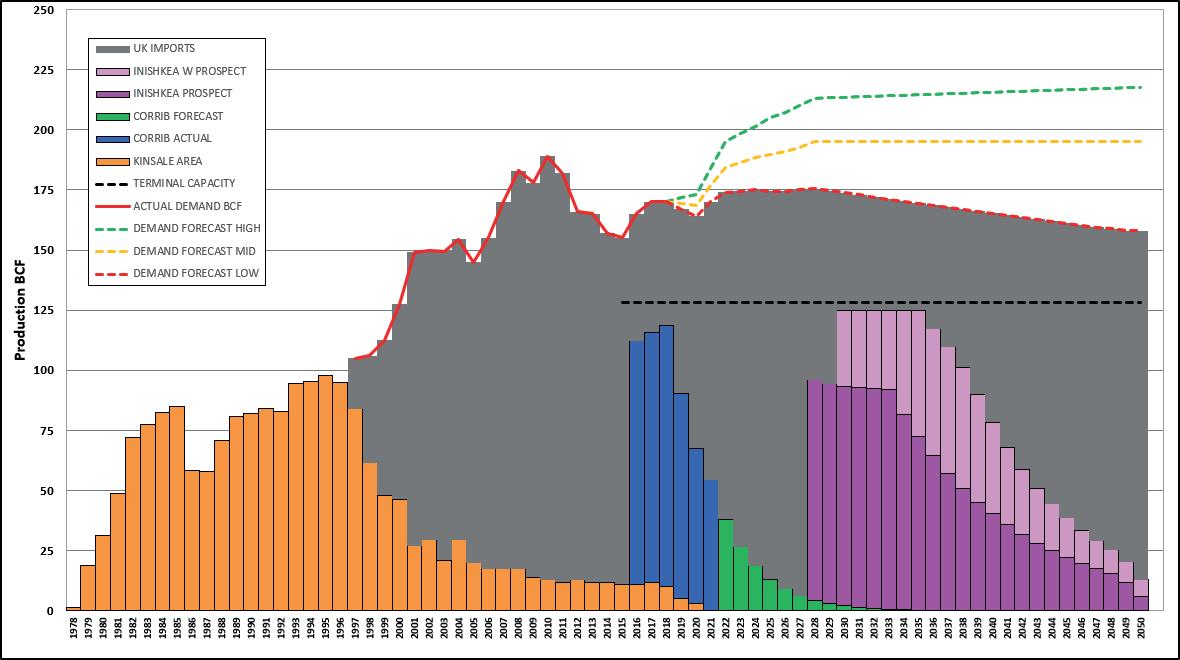

The sole source of domestic gas supply in Ireland comes from the Corrib field, located in the Atlantic Ocean roughly 85km offshore of County Mayo. Figure 2 shows the location of Corrib and the associated infrastructure that supplies Ireland with gas. Corrib supplies roughly 20 per cent of Ireland’s annual demand, with the remaining 80 per cent coming from the UK via the Moffat gas interconnector. The gas supplied from the UK comes from various sources including liquified natural gas (LNG), which has very high associated emissions intensity due to the cooling

process to liquefy the gas before it is transported via sea tankers.

Adjacent to Corrib is the FEL 4/19 exploration licence, which contains two sizable gas prospects, and is owned and operated by Europa Oil and Gas. The first is about the same size as Corrib and the second is roughly twice the size of Corrib. Because these two prospects are geologically very similar to the Corrib gas field the risks associated with the development of these fields are well understood and the chance of success is high for an exploration project, roughly one in three for each of them. FEL 4/19 borders the Corrib field and as such the discovered gas within the FEL 4/19 licence could be quickly connected to the existing infrastructure and brought online to displace high emission imported gas from the UK/USA.

An independent emissions report by Sustainable, (www.esgable.com), calculated that the average emissions resulting from the development of domestic gas produced at FEL 4/19 would be 2.8kg CO2e/boe (kilograms of

carbon dioxide equivalent per barrel of oil equivalent) compared to imported gas from UK which has an average emissions intensity of 36kg CO2e/boe, 13 times higher. The UK imports on average between 15 and 20 per cent of its gas supply from LNG, including LNG from the USA which, being fracked gas, which is gas extracted by hydraulically fracturing the shale/reservoir to release the trapped gas, has an emissions intensity 145kg CO2e/boe, 50 times more than the gas which could be produced from FEL 4/19.

The Corrib field is in decline and without the development of an adjacent gas field it will produce less gas each year before eventually being shut down, potentially within the next 10 years. This will result in 180 well paid jobs being lost at the Bellanaboy Gas Terminal and will have a material economic impact on County Mayo. Any discovery at FEL 4/19 would extend the life of the Bellanaboy Gas Terminal and has the potential to provide Ireland with circa 75 per cent of its forecast gas demand until 2035. Figure 1 shows the historical supply and demand for gas in Ireland as well as the forecast demand until 2050. It is clear from this that natural gas will continue to play a major role in Ireland’s energy mix well into the future and, without new sources of domestic gas, Ireland will be completely reliant on high emission imported gas as soon as Corrib is shut down.

Exploration and development of an offshore gas field is a complex and costly business and to realise the potential of FEL 4/19 an international energy company would need to drill and

Kinsale and Satellite Fields

Actual

Demand Forecast

connect these fields to the existing Corrib infrastructure. Although expensive, these activities would come at no cost to the Irish taxpayer. In fact, the development and production of domestic gas generates material income to the State through taxes and job creation. The development of FEL 4/19 is forecast to generate over €10 billion in taxes from just the licence itself, in addition to this there would be taxes from the jobs created at Bellanaboy and the associated economic activity that stems from this employment.

Bellanaboy Terminal Capacity

E: mail@europaoil.com W: www.europaoil.com Demand

IMPORT OF HIGH CARBON GAS FROM THE UK

INISHKEA WEST

The risk-reward value proposition provided by FEL 4/19 to a major upstream energy company is not just highly compelling, it is world class. Yet since 2018 major energy companies, such as ENI, Total, Equinor and Woodside, have all exited Ireland. This is because Ireland is perceived to be an inhospitable jurisdiction by the upstream sector, a situation that was highlighted at the recent Energy Summit hosted by the Taoiseach. The fact is Ireland has the necessary legislation to explore and develop existing licences, such as FEL 4/19, but this is not recognised by the

upstream industry as a whole. Perception is reality and in order to change the current perception of Ireland, the Government needs to vocally emphasise its commitment to the status quo, i.e., that the existing licences remain valid, any major upstream energy company that invested in Ireland would be welcomed, and that these exploration licences could be progressed through their natural phases of development and production. By doing so, the Government could secure a reliable and plentiful supply of domestic gas out to 2035 and beyond. Not only would this provide Ireland with security of gas supply but importantly the produced gas would be the lowest emissions gas that Ireland can obtain, which would reduce emissions and help Ireland achieve its net zero 2050 goals.

William Holland is CEO of Europa Oil & Gas (Holdings) plc, which owns 100 per cent of the FEL 4/19 licence.

INISHKEA

Corrib

Corrib Forecast

Figure 1: Historic and forecast Irish gas supply and demand. (Source: Petroleum Affairs Division, DECC)

Fit for 55: Hydrogen and decarbonised gas position agreed

European Council’s position on the proposed hydrogen and decarbonised gas market package, with a market shift targeted whereby renewable and low-carbon gases would account for two-thirds of gas usage by 2050.

The agreement was reached as the EU progresses towards its Fit for 55 goals, with the cutting of EU greenhouse gas emissions by 55 per cent the ultimate goal. Following the European Commission’s proposal of a review of EU gas market design as part of these reforms, the hydrogen and gas market package was devised to revise the gas regulation and directive of 2009 and the security of gas supply regulation of 2017.

Member states agreed the Council’s position for negotiations with the European Parliament in March 2023. With renewable and low-carbon gases currently making up 5 per cent of European gas storage, the agreed proposals aim to increase that proportion to 66 per cent by 2050. These renewable gases will come from either organic sources such as biogas or biomethane, or non-biological (using electricity) renewable sources such as hydrogen and synthetic methane. The low-carbon gases produced will not come from renewable sources but will

produce “at least 70 per cent less” greenhouse gas emissions than fossil natural gas across their full lifecycle.

These new rules are aimed at enabling four major EU policy goals under the Fit for 55 principles:

1. Creating a market for hydrogen. The EU aims to have 40 gigawatts of renewable hydrogen electrolyser capacity and the ability to produce 10 million tonnes of renewable hydrogen by 2030.

2. Integrating renewable and lowcarbon gases into the gas grid. 2049 will be set as the maximum end date for long-term fossil gas contracts as the EU looks to facilitate access to the existing has grid for more renewable options through measures such as the removal of cross-border tariffs.

3. Engaging and protecting consumers through measures such as providing simpler ways to change energy provider, more

transparent billing information, and access to smart meters.

4. Increasing security of supply and cooperation through integrated planning for electricity, gas, and hydrogen networks, certification of storage system operators, and strengthened solidarity arrangements between EU countries, to deal with “crisis situations”.

Also agreed in July 2023 was the revised Energy Efficiency Directive, which sets a legally binding target of an 11.7 per cent reduction in final energy consumption by 2030 when compared with 2020 levels. EU member states will be legally required under the new directive to prioritise energy efficiency in policymaking, planning, and “major investments”, a requirement that will give the energy efficiency first principle “substantial legal standing for the first time”.

Outlook on European gas market

Studies says that while the European gas market is in much better position than a year ago, tightness in the market means there is little room for complacency in the time ahead.

European gas (and energy) prices have been on a roller-coaster since 2021. They climbed from very low levels in 2020 to record highs in 2021 and 2022, before declining again from December 2022. In May 2023, they reached their lowest point in almost two years at about €30/MWh (TTF Front-Month on 19 May). Despite this relative lull, the supply and demand balance remains very tight.

For the next 12 to 18 months, indigenous production and pipeline imports are unlikely to be higher than at present. Russian gas flows via Belarus, the Baltics and Finland, and Nord Stream stopped in 2022; and the only flows left are via Ukraine and TurkStream. Other sources of pipeline gas (Norway, north Africa, Azerbaijan) have been relatively stable, but there is limited additional gas to be expected.

LNG imports ramped up rapidly in 2022 to make up for the loss of Russian

TTF Front-Month gas prices from January 2017 to April 2023 (midpoint, Euro/MWh)

Source: data from d’Argus, chart by

Anouk Honoré (OIES)

pipeline gas. It is now the single largest source of supply to the region, with some upside potential thanks to new regasification capacity (over 40 bcm expected in Northern Europe by end 2023 plus additional capacities around the region in the coming years). The downside is that Europe is now far more exposed to global LNG trends than ever before, although for now, the return of freeport liquefaction capacity (USA) and relatively low Asian demand mean that cargoes are arriving in Europe, in time to help with storage replenishment.

Europe finished the winter with relatively high storage levels, and stocks were already at 63 bcm by the end of April 2023. This was over 28 bcm higher year-on-year. As a result, Europe is unlikely to need to repeat the large net injection made in the calendar year 2022. Meeting the target of 90 per cent of the stocks filled by November should not be problematic despite the region receiving far less Russian pipeline gas in Q2 2023 than in Q2 2022, although the speed of stock build remains uncertain. There could be some potential nervousness (and therefore likely higher prices) around September if storage levels are still low by then.

The biggest uncertainty might be on the demand side. Gas consumption in Europe (EU27 + UK) collapsed in 2022 (-13 per cent) on the back of mild temperatures, high gas prices, and changes in consumer behaviour. Trends in 2023 remain subdued (-14 per cent in the first four months) helped by unseasonably mild weather across most of Europe and higher availability of renewables (hydro, wind, and solar) in power generation, but the fundamentals in the three main sectors seem to point toward a potential recovery of gas demand in the coming months.

Many industrial sectors were able to reduce their gas demand without reducing their production over the past 18 months, by switching to alternative fuels (especially oil products) and improving operational efficiency (although the chemical sector, the pulp and paper sector and the iron and steel sector were clear exceptions). Since the beginning of 2023, there seems to be a slow recovery of gas demand in most sectors, and a continuation of relative

Monthly gas demand in the EU27 + UK, bcm

Source: charts by Anouk Honoré (OIES) with data from IEA, Eurostat, Entsog, Entsoe, GRTgaz, Terega, NCG, Gaspool, THE, SNAM, Enagas, NationalGrid, Gridwatch, Honoré’s assumptions and calculations.

“Europe is in a much better position than a year ago, but it still cannot be complacent.”

low gas prices in 2023 (and continued governmental support), as well as a limited economic downturn, could contribute to higher industrial gas use in the coming months compared to 2022.

In the residential and commercial sectors, mild weather limited the use of gas for heating in 2022 and early 2023. Coupled with high gas prices, warm temperatures also seem to have facilitated an important demand response from small consumers, a usually rather inelastic sector.

Continued participation of consumers in demand saving measures will be essential in the coming months, though consumers’ willingness to reduce their energy for heating may erode if cold temperatures hit Europe at the end of 2023.

The biggest unknown is in the electricity generation sector. Lower

electricity demand, strong renewables, and the progressive return of French nuclear fleet limited the need for gas at the end of 2022, but gas demand could remain high this year due to uncertainties regarding the level of French nuclear generation in 2023 (stress corrosion tests, new cracks, drought in the summer), coal to gas switching, low hydro availability in the summer and a possible electricity demand recovery.

The European gas market is a complex puzzle with many moving pieces, and despite lower gas prices since the beginning of 2023, the market is still tight. Even small changes on the supply or on the demand side could trigger a sharp increase in gas prices. Europe is in a much better position than a year ago, but it still cannot be complacent.

Internal markets rules positions determined

EU member states and the European Council agreed their negotiating positions on proposals to set common internal markets rules for renewable and natural gases and hydrogen in March 2023, with different tariff discounts for renewable and low-carbon gases agreed.

Among the most notable of the positions agreed by the European Council is that of the tariffs and tariff discounts offered to hydrogen and renewable gases seeking access to the gas grid. Tariff discounts for renewable gasses have been set at 100 per cent, with tariff discounts for low-carbon gases set at 75 per cent. Also notable

is that the agreed position allows for the blending of hydrogen into the natural gas system of up to 2 per cent by volume rather than 5 per cent “in order to ensure a harmonised quality of gas”.

In terms of the certification of storage system operators, key to these market developments, the general approach

enshrines the provisions of the gas storage regulation of June 2022 into text and introduces a 100 per cent discount to capacity-based transmission and distribution tariffs to underground gas storage and LNG facilities.

Full ownership unbundling has been retained by the member states as the default model regarding the unbundling of future hydrogen networks. However, the agreement will still allow for the independent transmissions system operator model – meaning energy supply companies can still own and operate networks through the use of a subsidiary – under “certain circumstances”.

The Council also stated that it had “made various changes to the consumer-related provisions” put forward by the European Commission as part of the second batch of the Fit for 55 proposals. These changes were said to regard “provision of information, facility of switching suppliers and termination in case of bundled offers”. Member states will have more flexibility regarding the deployment of smart metering systems, according to the Council.

The agreement also contains the extension of the transition phase for implementing detailed rules for hydrogen for member states until 2035. A mechanism allowing for public intervention in price setting in case of an emergency situation has also been added, “mirroring provisions in the proposal for the electricity market design review currently under discussion”. This mechanism “would be adapted according to the outcome of negotiations on the electricity market design”. Limited derogations to some provisions for some member states in “specific circumstances” have also been added.

The Council will now enter into negotiations with the European Parliament as Brussels seeks to finalise its package and discuss proposals for renewable gas and hydrogen regulation and a European directive on the matter.

Energy Markets and Security Conference 2023

Wednesday 4 October 2023 • The Gibson Hotel, Dublin

Electricity market design has come into sharp focus since the Russian invasion of Ukraine that disrupted gas supply to Europe causing both gas and electricity prices to rise sharply. In addition, the increase in renewable electricity sources has led to the need to rethink how the existing electricity market mechanism works. In March 2023, the European Commission published a proposal to reform the EU electricity market to address these issues and make the EU electricity market design fit for 2050.