Keith Barnacastle • Publisher

Richelle Putnam holds a BS in Marketing Management and an MA in Creative Writing. She is a Mississippi Arts Commission (MAC) Teaching Artist, two-time MAC Literary Arts Fellow, and Mississippi Humanities Speaker. Her fiction, poetry, essays, and articles have been published in many print and online literary journals and magazines. Among her six published books are a 2014 Moonbeam Children’s Book Awards Silver Medalist and a 2017 Foreword Indies Book Awards Bronze Medal winner. Visit her website at www.richelleputnam.com.

Rebekah Speer has nearly twenty years in the music industry in Nashville, TN. She creates a unique “look” for every issue of The Bluegrass Standard, and enjoys learning about each artist. In addition to her creative work with The Bluegrass Standard, Rebekah also provides graphic design and technical support to a variety of clients. www.rebekahspeer.com

Susan traveled with a mixed ensemble at Trevecca Nazarene college as PR for the college. From there she moved on to working at Sony Music Nashville for 17 years in several compacities then transitioning on to the Nashville Songwritrers Association International (NSAI) where she was Sponsorship Director. The next step of her musical journey was to open her own business where she secured sponsorships for various events or companies in which the IBMA/World of Bluegrass was one of her clients.

Susan Marquez is a freelance writer based in Madison, Mississippi and a Mississippi Arts Commission Roster Artist. After a 20+ year career in advertising and marketing, she began a professional writing career in 2001. Since that time she has written over 2000 articles which have been published in magazines, newspapers, business journals, trade publications.

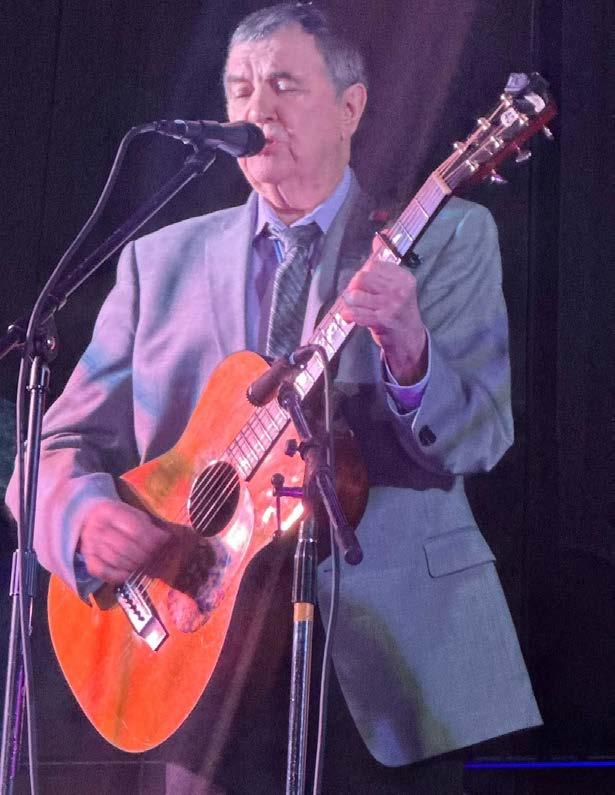

Singer/Songwriter/Blogger and SilverWolf recording artist, Mississippi Chris Sharp hails from remote Kemper County, near his hometown of Meridian. An original/founding cast member of the award-winning, long running radio show, The Sucarnochee Revue, as featured on Alabama and Mississippi Public Broadcasting, Chris performs with his daughter, Piper. Chris’s songs have been covered by The Del McCoury Band, The Henhouse Prowlers, and others. mississippichrissharp.blog

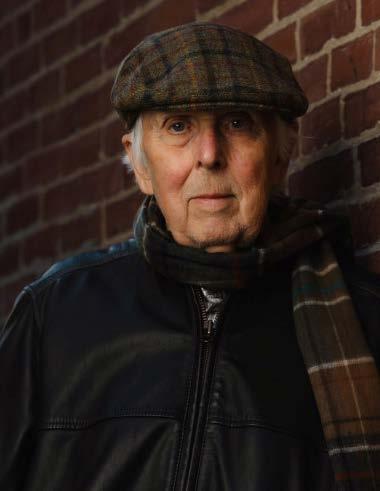

Brent Davis produced documentaries, interview shows, and many other projects during a 40 year career in public media. He’s also the author of the bluegrass novel Raising Kane. Davis lives in Columbus, Ohio.

Kara Martinez Bachman is a nonfiction author, book and magazine editor, and freelance writer. A former staff entertainment reporter, columnist and community news editor for the New Orleans Times-Picayune, her music and culture reporting has also appeared on a freelance basis in dozens of regional, national and international publications.

Candace Nelson is a marketing professional living in Charleston, West Virginia. She is the author of the book “The West Virginia Pepperoni Roll.” In her free time, Nelson travels and blogs about Appalachian food culture at CandaceLately.com. Find her on Twitter at @Candace07 or email CandaceRNelson@gmail.com.

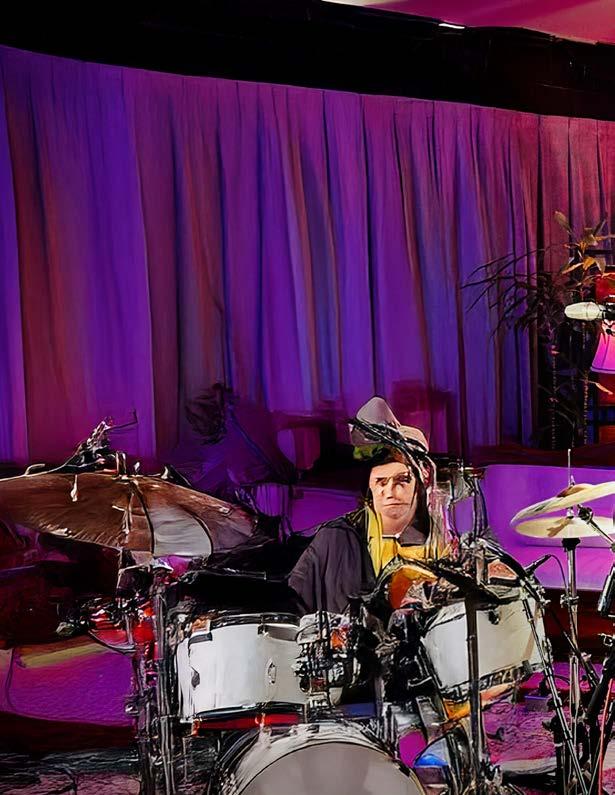

A Philadelphia native and seasoned musician, has dedicated over forty years to music. Starting as a guitar prodigy at eight, he expanded his talents to audio engineering and mastering various instruments, including drums, piano, mandolin, banjo, dobro, and bass. Alongside his brother, he formed The Young Brothers band, and his career highlights include co-writing a song with Kid Rock for Rebel Soul.

Stephen Pitalo has written entertainment journalism for more than 35 years and is the world’s leading music video historian. He writes, edits and publishes Music Video Time Machine magazine, the only magazine that takes you behind the scenes of music videos during their heyday, known as the Golden Age of Music Video (1976-1994). He has interviewed talents ranging from Ray Davies to Joey Ramone to Billy Strings to Joan Jett to John Landis to Bill Plympton.

by Brent Davis

A shed in the shadow of Black Mountain near Brevard, N.C., is not only the studio where an acclaimed banjoist creates albums, does session work, and scores shows such as the television series Poker Face. It’s also where an entrepreneurial educator devises innovative new online music instruction methods.

It’s not that two individuals are sharing this space. It’s just that Bennett Sullivan wears many hats.

“I’ve never looked at performing as my sole way of making an income,” says Sullivan. “I really enjoy the diversification of being a musician. That could include my banjo playing on The Greatest Showman or on Poker Face. I also want to find different ways to share my teaching message with a lot of people. And so that’s why I have gravitated towards technology and websites and subscriptions and YouTube.”

Sullivan grew up in Greensboro, N.C., under the influence of his guitar-playing father. He started on the guitar but gravitated to the banjo around age 12.

“I remember putting on this recording of Ron Block playing the Alison Krauss version of “Cluck Old Hen,” and I started picking out the notes. At that point, the light bulb went off, and I was like, Oh, I can do this myself. I can listen to recordings and figure it out.”

But Sullivan’s musical interests were—and continue to be—wide-ranging.

“I love John Coltrane, I love Dexter Gordon. Oscar Peterson. All those jazz guys. And now I’m obsessed with pedal steel. So, I’ve been learning a lot of pedal steel music. I’ve always liked a lot of different music, not just bluegrass.”

Though Sullivan studied music for a few semesters in college, he gained vital experience performing with cruise ship bands. While he was hired to play guitar in the shows, off the clock, he was woodshedding on the banjo.

“I would lock myself on the bandstand late at night and just work out solos and practice,” Sullivan recalls. “I give credit to playing and being immersed in music on a cruise ship and being around really good musicians. That’s kind of my education.”

Back on land, Sullivan followed the woman he would marry to New York, where he studied jazz guitar for a semester at the New School. “I tried to switch over to banjo. They weren’t really into that, and I ended up dropping out and working a retail job.”

But an acquaintanceship with banjo player Noam Pikelny led to an introduction to Steve Martin—yes, THAT Steve Martin—who was developing the musical Bright Star along with Edie Brickell. After a tryout Sullivan was hired as the banjo player for the show which was built around bluegrass and roots music.

“It was not a Broadway thing at the beginning,” Sullivan says. “We workshopped it in San Diego first, and then, we eventually took it to the Kennedy Center and then to Broadway.”

The original five-piece bluegrass band grew into a larger orchestra. Sullivan’s experiences and musical chops, which he developed playing on cruises, proved invaluable.

“In a musical, you have to take into account all of the other things that are going on, like what’s the next song? How fast do I have to be ready to play the next song? And what key is the next song in? Am I moving around the stage? Do I have to switch instruments? Because I was playing two banjos and one guitar. It is nerve-wracking because it’s not just getting up on stage and playing a bluegrass gig. You’re waiting for cues. You’ve got to be focused.”

Bright Star played for four months, and after doing eight shows a week during the run, Sullivan was ready for a change. Brevard, N.C., would be the new home for Sullivan, his wife, and his young son. (The family has since grown to include a daughter.) In addition to the music he creates in the studio he built, Sullivan plays with prominent groups including Zoe & Cloyd, Woody Platt and Shannon Whitworth, and Woodbox Heroes, with whom he recently played the Grand Ole Opry. He’s also a prolific online instructor whose projects range from the Pocket Lick phone app to banjolicks.com, his website that uses short licks as the basic building block for banjo knowledge.

“I just like the simplicity of a small two-bar or four-bar phrase,” he explains. “You don’t have to put the pressure on yourself to learn an entire piece of music by ear. I’m all about practicing slowly to really dial in the timing. So, the licks are super slow on the examples. You can play along and dial it in at a really slow pace and then start to speed it up on your own with a metronome or a backing track.”

In the early months of 2026, Sullivan wants to create more of his own music, following up on his eclectic and introspective Eager to Break album. In March, he’ll present his second annual online Lick Fest to subscribers, where he’ll work with 16 artists over a couple of days to develop basic licks into useful variations and themes.

“My primary goal with the Banjo Licks site is to help people become better foundational players with better timing, better ears, and increased creativity. It’s going to be a good year for Banjo Licks, but also for me as an artist. I’m pumped about it.”

by Susan Marquez

High River has always been comprised of a group of friends who get together to play bluegrass music. The band got its beginning in 2022 when the Campbellton Bluegrass Festival in New Brunswick, southeastern Canada, needed a band to fill a last-minute spot. “I made a few calls to some jamming buddies, and just like that High River was born,” says Jason Guimond, who plays banjo and vocals for the band. The ad hoc band sounded great, and they were well received by the audience. “We had so much fun that weekend, we decided to keep it going.”

The band is made up of Jason, along with Thomas Leblanc on guitar and vocals, Marcel Allain on bass and vocals, Marc Landry on dobro, guitar, and vocals, and

Lawrence Martin on mandolin and vocals. The playing part came easily to the band members. The next step was to brand themselves with a name for the band. “The name High River just felt right for our sound and where we come from. It’s got that natural, rolling feel to it kind of like our music. There’s no one story behind it, but it’s grown to represent the flow and drive we bring to bluegrass.”

While the band members all have day jobs, bluegrass is a huge part of their lives. “We spend a lot of our free time rehearsing, recording, or out on the road playing festivals,” says Jason. “It’s definitely more than just a hobby for us.”

Perhaps it’s because of the location near the northern foothills of the Appalachian Mountains. Whatever the reason, the bluegrass scene is very active in New Brunswick. “You’ll rarely see a weekend where there isn’t a jam going on in someone’s house,” Jason says. “It’s a close-knit scene full of people who just love the music. We split our time pretty evenly between festivals and a certain lounge we’d like to plug Le Paysan in Saint-Antoine, New Brunswick. It’s become a great spot for live bluegrass and good company.”

High River has been described as “embodying the spirit of bluegrass while pushing boundaries and exploring new musical territories,” with a nod to traditional bluegrass music with a modern twist. “That’s a nice way to put it,” says Jason. “We all love traditional, harddriving bluegrass bands like Lonesome River Band, Blue Highway, and Dan Tyminski are big influences and we’ve also been shaped by where we come from. We all grew up around kitchen parties where the music never really stopped, and we’ve been inspired by local musicians who’ve kept the music alive here in the Maritimes. We like songs that tell honest stories, whether they’re originals or covers, but we don’t mind putting our own spin on things.”

Most of the songs High River plays are covers. “They are the songs we love and enjoy putting our own touch on,” states Jason. “That said, we have another recording project coming up in the near future, and we plan on releasing a couple of originals of our own.”

Their first record, a self-titled LP, dropped on September 5. “We’re really proud of it. It’s a mix of original songs and some of our favorite covers, recorded with that traditional bluegrass drive we love. We wanted it to capture the energy of our live shows. We hope people feel something real when they hear our songs. Whether it’s joy, heartache, or just the urge to tap their foot as long as it connects with them, that’s what matters.”

Since that unplanned beginning back in 2022, the band has grown tighter musically and closer as friends. “The more we play together, the more natural it feels. Everyone’s found their spot in the band, and our sound has really come into its own.”

Jason says for now they plan to keep the momentum going playing more shows, writing new songs, and hopefully getting back in the studio before long. “We’ve had a great response to the album, and we’re excited to see where the road takes us next.”

by Amanda G. Maphies

The monumental Hillberry Bluegrass festival recently reached a milestone decade year, offering a five-day bluegrass festival at The Farm, just a few miles outside of historic Eureka Springs, Arkansas. Each year’s atmosphere creates a unique persona of welcome, relaxation, and the indulgent appreciation of a grassroots movement that has been entertaining audiences for years. ‘Happy Hillberry’ was uttered on multiple occasions. It was almost as if this five-day bluegrass festival, with loyal concertgoers, campers, craft distributors, vendors, and newcomers, had morphed into a nationally recognized holiday.

Jon Walker, Deadhead Productions Manager and The Farm Campground Events owner, said this of Hillberry Harvest Moon Festival 2025: “We have produced 33 music festivals over the past 14 years. This year, I feel like we finally accomplished what we set out to do. The community came together and supported us on our 10-year anniversary of the Hillberry Music Festival. It was the highest attendance to date, yet the smoothest run event we have ever produced. We had some of the nicest people on the planet who traveled long distances to be here. We work hard to provide great production and great staff, but the people are truly what make our event special. The energy, gratitude, and love expressed by our attendees are what continue to push us forward. We are proud that we built this organically and that our intentions are driven by our love of music. We are beyond grateful to our community for their years of support in helping us build something so special that is the Hillberry Music Festival.”

The Farm is a large plot of rolling hills and autumn-changing trees that serves as a host for many local and far-reaching roots musicians, not to mention the hundreds of fans who show up, year after year, to enjoy their favorite bands and taste new and rising future bluegrass artists.

Hillberry 2025: The Harvest Moon Festival is a family-friendly event catering to all ages, from the youngest to the oldest, offering something special for everyone at this fall outdoor music lover’s paradise in the heart of the Ozarks. While evening is when the heavy-hitting bands and solo artists put on their grand shows, daytime at Hillberry is full of a wide array of entertainment all its own. From human wheelbarrow races in the circus-striped media tent to multiple afternoon parades led by children of all ages, there is never a dull moment at this bluegrass oasis in the hills.

Jon Walker of Deadhead Productions and owner of The Farm Campground and Events at 1 Blue Heron Lane in Eureka Springs, Arkansas, invited his soon-to-be 85-year-old mother to the Hillberry Harvest Moon Festival this year. “This was her first music festival. I have always tried to explain what I do, but I felt that she needed to see it with her own eyes, because it’s hard to describe to someone what a festival is all about. She loved it!” shared Walker.

On the other end of the age spectrum, proving that Hillberry has something to offer for every age, Adams Collins, Arkansauce banjo player, gave a touching shout-out to his fourmonth-old daughter, who also experienced her first Hillberry. You gotta start ‘em young! (Something tells me, with her dad’s mad string pickin’ and vocal skills, this will not be his daughter’s last Hillberry. She may even take center stage in the next few years, giving her ole man a run for his money).

Tom Anderson, the stand-up bass player for Arkansauce, wished his wife, Holly, a Happy 10th anniversary while performing live in front of hundreds. Arkansauce is familiar with Hillberry, having performed at the festival since its inception. A local band from Fayetteville, Arkansas, these four bandmates, now with a complete brass and percussion section, have really put the state of Arkansas on the map as a bluegrass hot spot. The band is scheduled to record a new album in Nashville, Tennessee, in the near future.

Presented by Railroad Earth and Deadhead Productions, the intent behind this five-day annual festival is to provide a warm and welcoming environment for bluegrass music lovers to ‘get away from it all’ and experience tried and true favorites, as well as newly discovered talent. This year’s lineup included such artists as Railroad Earth, Greensky Bluegrass, The Infamous Stringdusters, Yonder Mountain String Band, Arkansauce, Crescent City Combo, The Steppers, Taylor Smith, and many more. (See full lineup here: https://hillberryfestival. com/#lineup).

If roughing it for five days isn’t your thing, there are many other ways to experience Hillberry. From basic tent camping to the glamping experience of an RV, a mini home on wheels, some festival goers pick a day or two and choose to stay in historic and romantic Eureka Springs. Coming and going to the festival at their leisure, based on the year’s lineup of performances.

Each year, there are the fan-favorite familiar vendors, with a sprinkling of new artisans proudly selling their wares, making the festival a prime locale for those who love handmade jewelry, vintage clothing, and everything from leather accessories to custom-made pottery. The festival offers breakfast, lunch, and dinner, with an extensive array of food and beverage trucks to suit every fanciful palate. Many choose to bring their own food and tailgate with friends and family while enjoying the atmospheric backdrop of popular pickin’ and grinnin’ in the distance.

The merchandise tents are always available with each band, artist, or general Hillberry attire. This year’s showcase was a large knit throw with the Hillberry insignia and lineup printed on the front. A true work of art, and a valuable keepsake for those cool fall evenings when the music knows no time limit. In addition to shopping, Hillberry offers daily craft

workshops, refreshing showers, and a wide array of breakout sessions to cater to the diverse interests of its bluegrass-loving crowd.

Deadhead Productions, named after the iconic rock band, The Grateful Dead, shared that the current state of affairs in our society feels heavy. They aim to create a relaxing and entertaining space that fosters solitude and freedom of expression. A place where guests can truly escape the hustle, bustle, and everyday stress of life to enjoy a beautiful natural backdrop accompanied by the soothing sounds of music, along with the fast-paced, melodic, toe-tapping and full-on dancing to the beat of each individual drum.

Plans for a festival of this magnitude are made months in advance. The promoters and management team are already looking forward to the 11th annual Hillberry in October 2026. You can find the lineup and ticket information here: https://hillberryfestival.com/.

Fully describing this yearly fall music festival in the heart of the Ozarks is a monumental task. You must personally experience it to truly appreciate the chill vibe, friendly atmosphere, and enjoyable music performed each year.

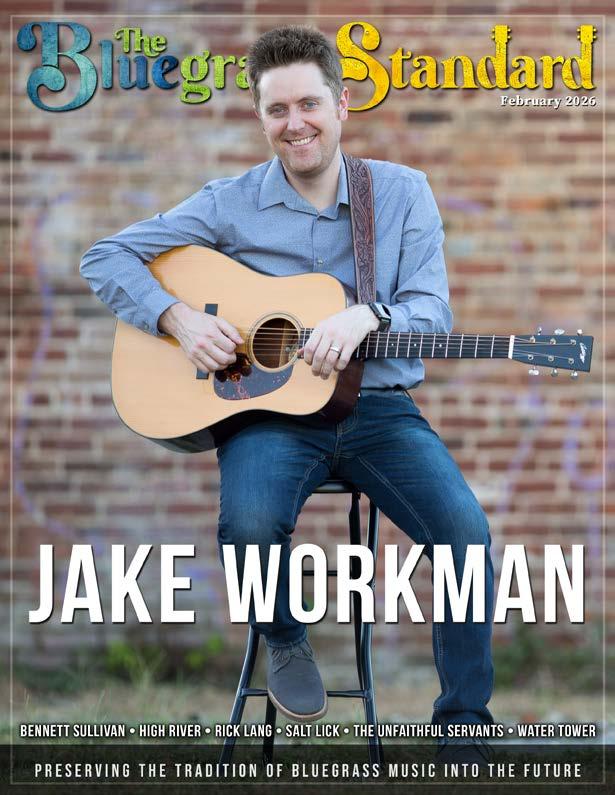

by Stephen Pitalo

It’s late in Oak City, Utah, and Jake Workman’s house is quiet. His kids are asleep. The room hums faintly from the last ring of an open-G chord. Guitars lean against the wall, their finish dulled by fingerprints and years of work. Workman is still at it six, sometimes eight hours a day chasing sound, chasing feel, chasing that invisible thing that makes one note matter more than another.

“Oh, thank you,” he says when told his playing “Rawhide” with Ricky Skaggs in a YouTube video is jaw-dropping. He’s humble, matter-of-fact. But when he starts to talk about the journey that brought him here, it’s clear there’s nothing casual about Jake Workman.

“I started on the guitar when I was 13,” Workman said. “But at the time, I didn’t even know what bluegrass music was. That would have been 2001, and at the time, I was into classic rock. Like my dad loved the Beatles, so I listen to the Beatles. And then I got into Boston and eventually Led Zeppelin, AC/DC, some of the harder eighties bands. And then a year and a half after I started playing guitar.”

“My parents got me a banjo and I thought it was a joke – what am I gonna do with this?” he laughed. “I don’t play bluegrass; I have no connection to bluegrass. I didn’t grow up picking with my grandpa, like a lot of people do, or whatever, and I didn’t have that. My family was a bunch of note-bound piano players, and they’re great, but classical music and whatnot, and everything they do is reading sheet music. I have no problem with that, but I was the odd one for sure. I also grew up out west, where I wasn’t really around bluegrass, so it was weird that I got a banjo, but my parents thought, ‘You took off on the guitar, what the heck?’ And then that was the gateway drug to bluegrass music.”

That gateway drug changed everything.

“I still play the banjo. I still teach it and would do more gigs on it if they ever came to me, but I’m not known for my banjo playing. I don’t play it and practice it as hard as I did at one time.”

What keeps him coming back to the banjo is the raw, physical joy of it. “I love the power that I have at that point. Like, the sheer volume, and the ability to have picks on separate three fingers versus one piece of plastic [for guitar]. That’s nice for speed and just being able to hang with a tune. The speed and the sheer volume and power, you don’t have to play as hard to still be heard. I love that…but if I’m playing by myself, I’d much rather be on a guitar.”

“The cool thing about bluegrass music is it’s so physically demanding and teaches you so much about how to attack an acoustic instrument, but also how to play against chord changes and whatnot. And I use everything that I’ve learned in bluegrass, in all these other genres, and it only helps. It only helps.”

From that discipline came the kind of clarity that would make him stand out in any lineup. In 2015, Ricky Skaggs called. Jake joined Kentucky Thunder, where every night was a master class.

“I was aware of things like rhythm that Ricky either did like about what I was doing – he always let me know when he’s enjoying the groove – but also, and especially in the beginning, he would let me know a few things that I was doing that he wouldn’t prefer to be going on. And of course, he’s the boss, and I’m happy to also just study from his experience. My groove and my rhythm, just my rhythm awareness. … I became a better listener. And yeah, I became better by being around great musicians, and hearing the ‘isms’ of each instrument at the very top level. You pick up things.”

He learned to honor what he calls “the Kentucky Thunder code.”

“For the Jake era of Kentucky Thunder, I wish we had a record to prove it. We got plenty of YouTube, but we never cut a record. I wish we did, but this is the Jake era. I don’t wanna sound like Brian [Sutton]. I don’t wanna sound like Cody [Kilby]. I love them to death, but I wanna sound like me.”

His time with Skaggs deepened not just his chops but his ear. “He always plays songs, not major, not minor, they’re in that modal in between Mountain minor kind of sounds where you have a major one chord, but you don’t always play the three, you don’t always make it obvious. And then the five chord is often minor, like a minor five chord, which you get in a mix of the Lydian world. And he’s not thinking deep like that. He’s just trusting his heart and his ears.”

That trust intellect and instinct shaking hands defines Workman’s philosophy. “Know your theory, but play from the gut,” he says later. It could be his credo.

“I don’t like to plan a record and say, I need tunes, so I’m gonna hurry and write ’ em. That’s just a recipe for cutting corners and not getting your best stuff out there. … If you allow that slow simmer, like from the writing to even the album artwork, don’t rush any piece of it so that it’s truly great and then you can release something epic that you’re proud of.”

That’s how Landmark came to be, and that’s how the next record still uncut, but written will arrive. “If you liked Landmark, you’ll like this one. I think my writing is even better.”

“The writing is deeper. I do think that my ears hear new things. I feel like the core progressions are a little cooler. I’ve got some cool arrangement ideas that aren’t just ‘oh, I’ll play A B B, and we’ll just trade solos the whole song. So far, the 10 tunes or so that I’ve got are all, I’m covering a wide range of keys, and I’m not using a capo on a single one of them.”

That challenge keeps him alive as a player. “Every key kind of gives me a vibe, so to speak. Open D can be really pretty, or it can be very bluesy. It depends, but I’ve written a couple in D one of them’s more of the bluesy thing, one’s more of the pretty thing.” Jazz, for him, sharpened the edges without forgetting the heart. “I had a lot of self-driven desire to understand music theory. So I showed up to school knowing a lot of things. I don’t care for ‘math music’ personally, but I think in general, jazz has a similar mindset as bluegrass, where you’re not wanting to be tethered to paper. You don’t wanna be tethered

to sheet music or tab or anything. You want it to be in here and in the heart.”

And the groove, he says, is sacred. “We’re also trying to find this balance of tension and release. That’s the tension in jazz might be more extreme, and the release might still be a semi-colorful note in jazz. … In bluegrass, it’s the same concept of tension release.”

When talk turns to the modern jam-band scene, his response is honest and unfiltered. “I’m not into it, I don’t care for the Grateful Dead personally. I’ve never dug them. … I personally like traditional bluegrass. I don’t mind if guys are up there in suits around one mic. And singing from the Heart Vocal, three-part harmonies. Like I just, I love the Bluegrass, the true bluegrass thing.”

He pauses, then softens. “Billy Strings, for example, is a good friend and a great player, great musician, and I love what he’s doing. ’Cause I think he’s being true to himself. … If you can see that and feel that it’s good.”

Still, he warns, “I think there’s a lot of fakeness out there and a lot of seeking cheap thrills. … A light show and fog machine if the music isn’t good first, I don’t care.”

These days, Jake is home more often, teaching from his studio in Utah. “Teaching, I love the interaction with people. I find a lot of joy in seeing people get excited about learning something. … Me teaching this stuff just makes me a better player. But I also think it’s just joyful, and I get to do it from right here.”

He’s found freedom in stability. “I can sit here and hold instruments that I would be holding anyway. Talk and think about stuff I would want to talk and think about anyway. It’s just a good gig.”

And like his name suggests, he works.

“Yeah. I get after it, and if I get too much downtime, it stresses me out. [laughs] I’ve been practicing hard for so many years that fire lit when I was really young, and then it never went out. I’ll hold a guitar for six to eight hours a day, even to this day, if you let me and I have the time to do it.”

He laughs when told he’s got the perfect name for a blue-collar picker, like a character straight out of a Roger Miller song.

“Yeah,” he says, “it’s a good name for the spot that I’ve landed in.”

So, in a quiet Utah town, Jake Workman still put in the work a scholar of sound, a craftsman of groove, a stickler for authenticity, and a man who never quite puts the guitar down. But then, I mean, why would he?

1. Modal / Mode

A “mode” is a kind of musical scale that gives a tune its unique emotional flavor bright, dark, or somewhere in between. When Jake says something is “modal,” he means it doesn’t sound completely major (happy) or minor (sad). It lives in that oldworld, Appalachian in-between that makes bluegrass sound both ancient and alive.

2. Mixolydian

A mode often used in bluegrass, country, and rock. It sounds mostly major but has one lowered note the flat seventh which gives it that earthy, mountain tone. When Jake mentions “the Mixolydian world,” he’s talking about that raw, rootsy sound you hear in songs like “Old Joe Clark” or “Salt Creek.”

A mode where one note (the fourth) is raised higher than in a standard major scale. It creates an open, floating, almost “glowing” sound. When Jake says “a mix of the Lydian world,” he means he hears hints of that airy, lifted feeling in some bluegrass melodies particularly in Ricky Skaggs’ mountainstyle tunes.

These describe notes that are slightly lower than in the major scale:

Flat third = gives a bluesy or melancholy tone.

Flat fifth = creates tension or grit. Flat seventh = adds a folk or mountain feel. When Jake lists these, he’s showing how bluegrass players create emotion through subtle dissonance coloring the music rather than keeping it polished.

The back-and-forth motion that gives music life. Tension occurs when the notes sound as if they need to resolve; release occurs when they finally do. Jake compares this to breathing both bluegrass and jazz build emotion by moving between pressure and relief.

These describe where a musician plays in time.

Front of the beat = slightly ahead, creating that driven, urgent bluegrass energy. Lying back = slightly behind, giving a more relaxed or jazzy feel. Jake switches between these depending on the song’s personality.

When the guitar’s strings, played without fretting, form a chord by themselves like G or D. Open tunings let the guitar ring out more fully, giving specific keys a distinct mood. Jake experiments with open keys to find fresh sounds and ideas.

8. Flatpicking

A bluegrass guitar technique using a single pick to play fast, melodic lines. It’s precise and percussive, blending rhythm and melody at once. Jake is one of today’s leading flatpickers a direct descendant of players like Tony Rice and Doc Watson.

A traditional Appalachian sound where melodies fall somewhere between major and minor. It gives songs a haunting, lonesome feel part folk, part Celtic, entirely bluegrass. Jake calls it that “in-between mountain minor sound” that’s neither happy nor sad, just human.

12. Modal Run

A quick musical phrase that uses one of those alternate scales (modes) instead of the standard major scale. It adds spice and movement to a solo, like taking a familiar road with a few scenic turns.

13. Modal Keys (Open A, D, E, etc.)

When Jake says he’s writing tunes in open A, open D, or open E, he means he’s using the natural tuning of those keys no capo so each has its own color and ring. To him, every key has a “vibe” and a mood, just like a room has its own light.

by Stephen Pitalo

There’s something deeply satisfying about a life that turns craft into a calling. For songwriter Rick Lang, that’s precisely how faith found its shape—through wood, words, and work. Fulfilling a 52-year career in the hardwood lumber business, Lang has spent decades refining two trades that require equal measures of patience and reverence. Whether he’s carefully planning Curly Hard Maple or shaping melody, the goal is the same: make something solid, true, and lasting.

Lang didn’t come up through the Sunday service or the Nashville circuit. His road to gospel music began far from both, in Exeter, New Hampshire, where he grew up in the late 1950s and early 1960s. He was just a kid who loved the radio, a fan before he was ever a believer.

I remember the first music that resonated with me was listening to the Everly Brothers on the radio,” Lang said. “I think my first 45 I picked up was the Everly Brothers’ ‘Wake Up Little Susie.’ Then over time I fell in love with Motown music and soul, and later with the folk scene—Tom Rush, Gordon Lightfoot, Simon & Garfunkel, and Bob Dylan. But when the late sixties came along, the music changed, and I just wasn’t feeling it anymore.”

For a while, Lang drifted away from music. Then one night in the mid-1980s, he stumbled upon a bluegrass show near home—and his life snapped into focus.

“Bluegrass music was something I didn’t know much about or had never heard much about,” he said. “I was just blown away by what I heard. The instrumentation and the singing and the harmonies – I’d never heard anything like it, so I started following bluegrass, buying records, learning how to play bluegrass rhythm. The more I listened, the more I loved it.”

Soon, he was running a regional bluegrass band, but he found himself drawn to taking pen to paper rather than stepping up to the mic.

“I realized I wasn’t really meant to be a singer in a bluegrass band,” Lang said. “I was more captivated by the songs. I started studying them, figuring out who wrote them, and discovered writers like Pete Goble and Randall Hylton. I just got the bug. I said, Man, I would love to write songs like this.”

He kept at it, writing on his own, with no roadmap and no mentor. Then in 1990, he sent one of his songs—a gospel number called “Listen to the Word of God”—to the Lonesome River Band. He didn’t expect to hear back. What he got instead was validation from the

highest level.

“Much to my surprise, Lonesome River Band recorded ‘Listen to the Word of God.’ It was released on their award-winning album Carrying the Tradition, and that was the catalyst. I thought, gosh, if I work hard, maybe I can become a songwriter.

That single cut was the spark, but the true fire of faith came years later. Lang found himself at a personal low point in 2008, and what saved him wasn’t a hit or a handout—it was prayer.

“I was struggling at many levels,” Lang admitted. “I got in this deep hole I couldn’t get out of, and I started praying. I said, Dear Lord, if you can pull me out of this hole I’m in, and help bring me back to the good place I was before, I’ll commit the rest of my life to serving you and writing songs of praise.”

From that promise came Look to the Light, Lang’s first all-original gospel project. It served as a personal journal in song form, filled with redemption and gratitude. Thus began his long collaboration with producer and songwriter Jerry Salley, who helped turn Lang’s quietly powerful writing into recordings that found an audience for his heartfelt compositions.

“That was my redemption,” Lang said. “That changed my whole life—writing gospel songs and living a life of gratitude. That was it right there.”

The success of Look to the Light led to another project with Salley, Gonna Sing, Gonna Shout, which became an award-winning release on Billy Blue Records. Featuring a who ‘s-who of bluegrass voices—Claire Lynch, The Whites, Marty Raybon, and Bradley Walker among them—the album hit #1 twice, won an IBMA Award, and earned Lang his first Grammy nomination. But it also gave him a new phrase for what he was creating.

“It was during that experience I realized we had created something a bit different, our own unique spin on Gospel music,” Lang said. “We deemed it ‘Blue Collar Gospel.’ It represents a particular style of gospel songs about ordinary people and their faith—about everyday hard-working folks, their struggles, failures, triumphs, and relationship with God.”

Lang saw that his writing could reach beyond the church walls—songs that hid their sermons in real life, that preached through empathy more than instruction. His lyrics felt like conversations with neighbors, not proclamations from pulpits.

When the pandemic hit and the world shut down, Lang refused to stop creating. Instead, he turned to technology and faith.

“I had never done any remote writing by FaceTime, Skype, or Zoom, but I decided to give it a shot,” he said. “Before I knew it, I was writing every day of the week. By the time the pandemic was over, I had built a catalog of dozens of brand new gospel songs that would become the foundation for our Blue Collar Gospel project.”

Released in 2024, the Blue Collar Gospel album celebrates everyday believers, sung by a diverse lineup that includes more female voices than his previous releases. Finding grace in the small details of life seems to be a recurring theme in this collection, whether in work, family, or quiet moments of faith.

As for Lang’s songwriting process, it begins before sunrise. Each morning, he and his wife Wendy take a long walk, and that’s where most of his songs are born.

“When I’m out walking, I pray and I ask God to send these song ideas,” he said, “and every time, I come home with a new song idea or two. They appear out of nowhere. I keep my mind open, and I just feel like I’m an empty vessel with all the ideas of the universe just flowing through me. It controls me, and I don’t control it.”

That surrender—trusting that inspiration is a divine gift—is what guides him now. Lang doesn’t see himself as a performer or even a writer in the traditional sense. He sees himself as a messenger, a conduit for something higher.

“I truly believe that writing gospel music is my calling, the Good Lord’s plan for me,” he said. “I’ve been told that spreading God’s Holy Word through my songwriting and music is a form of ministry. I believe that to be true. It is my hope that each song touches the heart, stirs the soul, and brings others closer to their faith.”

Through Blue Collar Gospel, Lang found the sweet spot where faith meets real life—a sound that’s humble, human, and full of light. “There are people who have faith in their lives, but they don’t formalize it by going to church,” he explains. “Even people who don’t go to church, when they need God’s help, they pray and reach out. I wanted to write songs not only for true believers but for people who could use faith in their lives—songs about everyday experiences where faith interweaves with people’s lives.”

Those stories—of fishermen, factory men, and quiet redemption—remind listeners that spirituality doesn’t have to sound solemn. Sometimes it sounds like a laugh in the middle of hard work, or like music on the radio just when you need it most.

After releasing Blue Collar Gospel on Billy Blue Records, Lang continues to write every day, often collaborating remotely with Nashville’s top songwriters. He’s now working on his first non-gospel studio album for Billy Blue, once again produced by GRAMMY Award-winning producer Jerry Salley.

“I’m not doing any of this for me,” Lang said. “Everything I’m doing is to serve God and to serve others.”

And as dawn breaks over the treetops, Rick Lang will take his daily walk, open his heart, and wait for the next song to arrive.

“If you want to be a real good Christian and follower, live your faith. Don’t just talk about it. Live it. Live your faith every day.”

His songs do exactly that— living, breathing proof of a life rebuilt through grace and work. Each lyric feels hand-carved, worn smooth by prayer and perseverance. And just like his lumberyard days, the quality is in the grain: strong, honest, and built to last.

For many new artists, making music is the easy part. They have grown up mastering their instrument, perhaps honing their craft at a well-regarded bluegrass or roots music program at a college or university. The hard part is getting noticed and navigating the complicated and ever-changing entertainment landscape. How does one turn musical talent and ability into a successful career?

Salt Lick Incubator may be the answer. It’s a non-profit artist development organization that supports artists in the early stages of their careers.

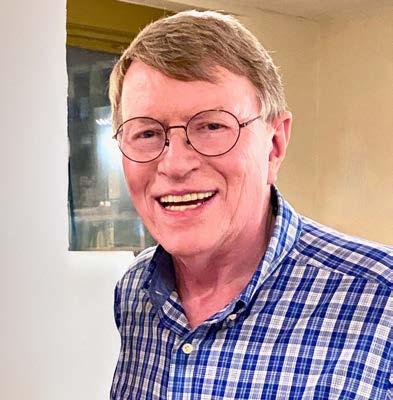

“I think our idea was, ‘How do we help launch emerging artists?’” says Roger Brown, the founder and chair of Salt Lick Incubator. After retiring as president of Berklee College of Music several years ago, Brown realized there was a need for an organization that could help artists starting their careers. “We were trying to think what is the right idea for it, and I tested ‘incubator’ with a bunch of the artists we were talking to, and they loved it. It’s a term not used in music so much, but our name, Salt Lick, harkens back to farms and early incubators that were on farms, so we went with it.”

“Salt Lick is a safe space to continue to develop your craft and continue to learn marketing tactics and identify your audience,” says Liza Levy, the incubator’s president. “And it’s a community of other artists as well that you can lean on, whether it’s for songwriting or production help or recommendations on where to make your merchandise or if you need places to crash on tour. We’ve got 42 artists in the incubator right now that all support each other.”

Salt Lick works with artists in many genres,

and bluegrass is well represented.

“We don’t want to try to work with a pop artist or a hiphop artist or a pop country artist because those are such well lubricated commercial spaces,” Brown explains. “We’re trying to work with artists who can have more of an organic career. People who can play their music, people who write great songs. So bluegrass is right in our sweet spot. We’ve had Sierra Hull, Old Crow Medicine Show, the Ruta Beggars, AJ Lee, Arkansauce, Molly Tuttle, Bloody Beggars, Twisted Pines, Sister Sadie, Farayi Malek, and The Arcadian Wild, Brown says. “We love the Americana roots bluegrass space.”

Support from the Salt Lick Incubator takes many forms, extending beyond networking among the artists. The musicians are featured on Salt Lick Sessions, a YouTube channel that has garnered nearly 17 million views.

“And, programmatically, it’s grants of up to $15,000 to do an EP or a tour or whatever,” Brown explains. “It’s songwriting camps and retreats. It’s the YouTube channel, as well as Instagram and TikTok, that utilize some of the same content to promote artists. It’s a weekly radio show that we do here in Boston that promotes emerging artists. And ultimately, the goal is to help very talented, aspiring artists have sustainable careers.”

Now in its third year, donors fund Salt Lick. There are two full-time employees assisted by six or seven interns from various colleges. The advisory board includes T Bone Burnett, Jon Batiste, Alison Brown, and Susan Tedeschi.

“They all have empathy for what it’s like when you’re in those early days,” Brown says of the board members. “And I think most of them are people who believe in the

kind of artistry we want to support. That’s less the latest TikTok sensation and more a real deep artist with something to say. They’ve all been incredibly enthusiastic, and some have offered mentoring to some of our specific artists.”

Levy explains that the grant process has been streamlined, and any artist can apply as long as they are not actively signed to a record label.

“Basically, everything an artist fills out on the application is things that they would need to know about themselves if they were looking to book themselves for a gig or looking to pitch themselves to a manager or an agent,” she explains. “It’s all about your unique artistic identity and voice and quality of songwriting and sort of fire in the belly. Are you really trying to make a career out of this? Then a selection committee, including the artist advisory board, makes the final selections.”

Before joining Salt Lick, Levy worked as a tour manager, did marketing for Rounder Records, worked for Universal Music Group in Los Angeles, and served as talent relations liaison at Berklee College of Music. Although she collaborates with a wide range of musicians at the incubator, she says bluegrass artists can particularly benefit from their unique environment.

“I think the power in bluegrass is the artist-to-artist community. I think the way that they all raise each other up. You can see it in so many careers. You know, Sierra Hull on stage with Alison Krauss when she was like nine years old. You even see it in the hallways at the International Bluegrass Music Association conference. There are artists of a certain stature jamming with kiddos. And I think that the most important thing you can do is have open ears, open hearts, and ingratiate yourself with that community and be a part of it. Be in the scene, embrace that scene, because they will embrace you.”

Salt Lick Incubator: Helping Emerging Artists Thrive

g to pitch themselves to a manager or an agent,” she explains. “It’s all about your unique artistic identity and voice and quality of songwriting and sort of fire in the belly. Are you really trying to make a career out of this? Then a selection committee, including the artist advisory board, makes the final selections.”

Before joining Salt Lick, Levy worked as a tour manager, did marketing for Rounder Records, worked for Universal Music Group in Los Angeles, and served as talent relations liaison at Berklee College of Music. Though she collaborates with all sorts of musicians at the incubator, she says bluegrass artists can benefit from their unique environment.

“I think the power in bluegrass is the artist-to-artist community. I think the way that they all raise each other up. You can see it in so many careers. You know, Sierra Hull on stage with Alison Krauss when she was like nine years old. You even see it in the hallways at the International Bluegrass Music Association conference. There are artists of a certain stature jamming with kiddos. And I think that the most important thing you can do is have open ears, open hearts, and ingratiate yourself with that community and be a part of it. Be in the scene, embrace that scene, because they will embrace you.”

by Susan Marquez

When Steve and Kay Ellis built a barn on their land outside Columbus, Mississippi, they had no idea how to produce and promote concerts. Yet today, The Barn is one of the most popular music venues in the area. “We’ve learned a lot over the past few years,” says Steve. “It’s not just about the music. We are committed to creating a great experience and making lasting memories.”

Steve and Kay bought their home 25 years ago. Next to the house was a pole barn that they turned into a playhouse for their kids. They later had a Mennonite family build two barns connected by a large, covered pavilion that they used for family reunions, class parties, and weddings. But Steve and Kay saw a way they could use it for more.

Music has always been a part of Steve’s life. A retired broadcaster, he built and ran the radio station at Mississippi State University – WMSV. “I had a vision for The Barn years ago,” he says.

Taking his love of music and combining it with community and a passion for giving back, what started as a simple pavilion on the side yard of the Ellis’s home has become a place where locals and visitors gather under the stars to enjoy good food, music, and fellowship.

The first show at The Bard was held on October 4, 2019. “It was 96 degrees that day, and Paul Thorne was scheduled to play. We sold 140 tickets, because that’s how many could fit under the roof of the pavilion,” recalls Steve. Despite the unseasonably hot temperatures, the show went on, and the folks attending loved it. “They all wanted to know when the next show was scheduled.”

But just as the venue was getting up and running, COVID squashed their concert plans. After a months-long hiatus, concerts started again in the Barn, and being isolated for so long, folks were thrilled to get out of their homes and back into the world. Now, many more people attend, and they bring lawn chairs. On concert nights, the field in front of the pavilion is full. Folks arrive early to claim their spot and visit with other regulars, while also meeting newcomers to the concert series. A $30 ticket covers a show with two artists and a meal.

At first, Kay cooked for the crowd, but when a local restaurant offered to provide the food, the Ellises took them up on it. Now, various restaurants in the area rotate, providing meals for the masses, along with cold beer and soft drinks.

The Barn’s concert series runs with a few shows scheduled each spring and a few more in the fall. Not just a venue, it’s been called a “sanctuary for music lovers” and a “chapel to songwriters.” Andrew Doohan was the first to use that phrase when he played at The Barn.

Steve transformed the pavilion into a place where artists entertain an appreciative crowd. He hangs the photos of all the artists who have played at The Barn on the pavilion’s back wall. It has become an inviting place for musicians, providing a unique experience for fans who love to listen to their music. The Barn has hosted an impressive lineup of musicians over the years, including singer/songwriter Mac McAnally.

Steve and Kay discover many of the acts at the annual Americana Festival. “If it’s someone we want to play, I’ll call their agent and see if they’ll be anywhere in our area. We just go from there.” Steve says they also attended the Folk Alliance International conference in New Orleans in January. “And YouTube is one of my favorite places online. I find a lot of talent by watching videos on YouTube.” But the real test is watching a band play live. “It’s always good when I can see how an audience reacts to a band.”

Acts have included Americana, blues, and bluegrass. There have been big names and emerging artists who appreciate the platform provided at The Barn.

One of the biggest joys for Steve and Kay is the connection the concert series at The Barn has with their community. Money collected at each show goes to a different charity. “We have donation buckets that make the rounds, and folks donate what they can.” They have raised money for several local charities, including Habitat for Humanity, as well as a neighbor whose home burned just hours before a show.

There is a limited number of season tickets, with sales opening in November. Individual tickets go on sale each January.

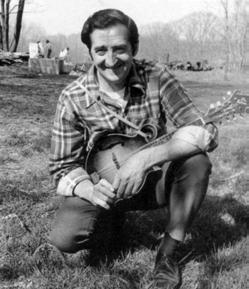

Kim Williams . . . “It’s what you leave behind you when you go”

My windshield wipers were barely keeping up with the swirling snow on the interstate when my phone began buzzing. It was 10 years ago—February 11, 2016—the night I learned Hall of Fame Songwriter Kim Williams had died.

I took the next exit in southwest Virginia and scribbled notes to help with an obituary for my friend and co-writer . . . one of the most remarkable people I’ve ever known.

But Kim already had written a fitting epitaph in the lyrics of what may be his most enduring song—a Country and Gospel hit for Randy Travis and Bluegrass No. 1 for Eddie Sanders.

“Three Wooden Crosses,” the multiple “Song of the Year” award winner that Kim wrote with songwriter/producer Doug Johnson, ends each chorus with these lines: “I guess it’s not what you take when you leave this world behind you . . . It’s what you leave behind you when you go.”

Kim Williams packed a lot of life into his 68 years and left a legacy that goes beyond his No. 1 hits and songs that still appear on Country, Bluegrass, and Gospel charts a decade later.

Pat Alger, who chaired the Nashville Songwriters Hall of Fame, said Kim “overcame more adversity than anyone I know to become one of the best and most colorful songwriters to ever come out of this town . . . and was always there to remind us that we can rise above it all to make sweet music.” From Adversity to a New Career

In 1947, Kim Williams was born into a music-loving family in the Poor Valley farming community of northeast Tennessee. He began learning guitar at age six, wrote

his first song five years later, and played in touring bands as a teenager.

After studying at Walters State Community College and the University of Tennessee, Kim became an electronics technician. A near-fatal industrial accident in1974 left him severely burned, requiring more than 200 reconstructive surgeries.

In liner notes to his 2010 Bluegrass album, “The Reason That I Sing,” Kim said the love and support of his wife Phyllis inspired his survival. “She was the only familiar face when the one in the mirror was a stranger,” he wrote. “She was there for me when my world had turned into ashes and pain. If I am anything, I am what she has given me the chance to be.”

While undergoing medical treatment, Kim took a songwriting class and began a new career. “I tell people that I got burned out on my last job and decided to become a songwriter,” he said in an interview with the Country Music Association’s Close-Up News Service.

Kim continued to learn as a member of the Knoxville Songwriters Association. Daughter Amanda Colleen Williams, an accomplished singer-songwriter and music educator in her own right, said he was developing “the determination driving him along to pursue his writing and really loving the camaraderie he found there.”

When Kim moved to Nashville, he became one of the most productive writers on Music Row. He routinely scheduled four writing appointments each day and made the rounds of writers’ nights to meet co-writers and demo singers. Through a copublishing arrangement with Sony/ATV, he later headed Kim Williams Music and helped his staff writers grow into hit writers. Combining creativity and hard work, he succeeded in getting more than 500 commercial recordings of songs in his catalog, helping to drive sales of more than154 million albums, tapes, and videos Friend and frequent co-writer Garth Brooks inducted Kim into the Nashville Songwriters Hall of Fame in 2012, calling him “the definition of what a songwriter should be.” In 2023, the State of Tennessee honored Kim’s accomplishments with a Music Pathways marker in his hometown of Rogersville. Kim’s “Real Songs” of Bluegrass

songs recorded. By that I mean songs about topics like death, life, religion, murder, abuse, inspiration—topics that sometimes (usually?) are too scary or controversial for mainstream music.”

Just listen to “The Last Suit You Wear,” written by Kim, his brother Larry Williams, and Larry Shell and recorded by Larry Sparks. The title track of Sparks’ album topped the Bluegrass charts and was nominated for IBMA Song of the Year in 2007.

That song opens with the story of a greedy banker, whose plane crashes on a farm he’d foreclosed on. The chorus reminds us that “The last suit you wear won’t need no pockets. You can’t take it with you when you go.”

February 2026 “Writer’s Room” column by David Haley Lauver— 3The Grasscals’ recording of “Don’t Tell Mama I Was Drinking” (written by Kim, Buddy Brock, and Jerry Laseter) is a cautionary tale with more impact than any public service announcement. The singer witnesses a truck wreck and finds the badly injured driver “with an empty whiskey bottle by his side.”

The young man’s last words are “Don’t tell Mama I was drinking, cause Lord knows that her soul would never rest . . . I can’t leave this world with my Mama thinking I met the Lord with whiskey on my breath.”

Another friend, Tim Stafford of Blue Highway, told Bluegrass Today that “in his later years, Kim decided he wanted to write more bluegrass because he considered it one of the last places you could get ‘real’

Blue Highway’s recording of “Seven Sundays in a Row” was a finalist for IBMA Song of the Year in 2004. Kim, Larry Shell, and Wayne Taylor wrote the story of Billy

Sparks, “a fightin’, drinkin’ man” whose life is changed by the love and prayers of a good woman.

Surprising the whole town, she even gets him to go to church! We’re told, “There’s a battle raging in his troubled soul. But God’s won seven Sundays in a row.”

The writers all were talented, and I don’t know who held the pen that wrote that song’s last verse. But it sure sounds like the way Kim Williams created a mirror of real life, reflecting lessons bigger than a single song:

“Sometimes we all stumble and we fall. There’s a little Billy Sparks inside us all. But as long as we believe, there’s always hope . . . for more than seven Sundays in a row.”

If you’re like most folks, you probably don’t think about the northeastern United States when it comes to bluegrass music.

But think again. If the name of the late Massachusetts-born mandolinist Joe Val doesn’t ring a bell, then you’re missing out on a bluegrass legend.

Born Joseph Valiante in 1926, Joe Val, a former typewriter repairman turned fulltime musician, was instrumental, along with the Confederate Mountaineers, in bringing bluegrass to Boston. He was dubbed “the voice of New England bluegrass” by Grammy-winning singer-songwriter Peter Rowan. Val’s legacy continues to inspire the Boston bluegrass community.

On that note, there is cause for celebration for New England’s bluegrass music scene, because this month, the Boston Bluegrass Union (BBU) will see the return of the Joe Val Bluegrass Festival.

Marking the 40th anniversary of the inaugural Joe Val memorial, the four-day indoor festival, which takes place over the weekend of February 12-15, will celebrate both the BBU’s 50th anniversary and the 100th anniversary of the birth of the late, great Joe Val himself.

Seeing it through: Tony Watt, the former BBU education director and newly-elected president. Watt, along with thirteen volunteer board members in charge of organizing events and workshops, has operated tirelessly to bring the festival back to the community.

We caught up with Tony Watt a couple months before the festival. As an International Bluegrass Music Association (IBMA) and Society for the Preservation of Bluegrass Music of America (SPBGMA) award–winning flatpicking guitarist, as well as an

Associate Professor at Berklee College of Music in Boston, Watt said he and other representatives of the BBU were very excited about the festival’s return. He views the event as an important way to bring people together.

“Our last festival was in February of 2020,” he recalled. “It was just about four weeks before the COVID shutdown. We were really lucky to have that last event!”

The BBU experienced further setbacks that year. “During the pandemic, we heard that the Sheraton Hotel, where we hold our festival, was going to become smaller,” remembered Watt, who added that the Framingham, MA hotel was already a tight squeeze for the event. “We had already outgrown the space. We started looking for a new home. That process was really challenging. They don’t build hotels the size we need to hold a festival like Joe Val anymore.”

Happily, their search ended with good news. “We found out that the Sheraton Hotel wasn’t becoming smaller; instead, they were dividing the hotel up into three separate hotels,” said Watt.

Although the renovations were another setback, the BBU managed to work around them. “The construction kept dragging on,” Watt recalled. “By 2024, we were back, but due to the massive renovations, we couldn’t have a main stage. We just did jams and workshops.” Organizers decided, temporarily and humorously, to call the festival “Jam Val.”

Watt was delighted to tell us that the full Joe Val Bluegrass Festival would return on February 12-15 of this year, with acts like the Del McCoury Band, Special Consensus, Danny Paisley and the Southern Grass, and the Gibson Brothers.

After serving as BBU vice-president for seven years, Tony Watt attributed his October 2025 election as president to his dedication to the storied bluegrass society. “I have been around the organization for so long that I have knowledge of its history,” he explained. “My dad (Steve Watt) was a founding member. When I was a kid, he was in charge of running sound for a lot of their shows.”

Watt’s first official involvement with the society was as an instructor at the Joe Val Bluegrass Festival each year. “They eventually invited me to be a board member,” he recalled. “I was in charge of education, which included workshops, classes, and things like that!”

As president, Watt hopes to bring back other programs affected by the pandemic. “We would do monthly kids’ jams for most of the year,” he said. “For now, our main youth

outreach is the Joe Val Kids’ Academy, which we will be reviving for the first time in six years. It’s a great opportunity for young people to gather together and get some bluegrass instruction. At the end, they get up on the main stage at the festival and have a big performance that everyone loves.”

This long-lived, one-time grassroots organization continues to enrich the community. “One of our ways of educating people about bluegrass is by bringing bands into the region that folks might not get to see some they might not have heard of before,” Watt commented.

He knows he has big shoes to fill, as he’s replacing president and founding member Stan Zdonik. “He was the president for most of the last fifty years! It is impossible to think of the BBU being successful without his tireless efforts,” Watt said of his predecessor. “Now that I’m president, I can appreciate how much work he did, and I am so grateful. He brought a high level of professionalism to the BBU, and value to the community.”

But the new president is certain he’s up to the challenge. “I am very dedicated to the organization and its continued long-term success,” Watt said with passion and quiet confidence. “I care about it, and I don’t want to let anyone down.”

The 2026 Joe Val Bluegrass Festival is happening this month from February 12-15 at the Sheraton Hotel in Framingham, MA. Visit the Boston Bluegrass Union at https:// bbu.org.

The Unfaithful Servants display superb craftsmanship and “a new light” in their sophomore album.

After a six-year hiatus, The Unfaithful Servants has released Fallen Angels, the sophomore album from the Americana band. Their new record is lovingly crafted by a quartet consisting of Jesse Cobb (mandolin), Singer-songwriter Dylan Stone, Quin Etheridge-Pedden (fiddle) and bassist Mark Johnson.

Hailing from Vancouver Island in British Columbia, the band was described as “Canada’s most exciting Newgrass band” after their performance at California’s Seaside Music Festival and has been nominated for a Canadian Folk Music Award. When asked what sets The Unfaithful Servants apart from other bands in Canada, Jesse Cobb is happy to explain what makes his band unique, stressing the members’ combined

instrumental prowess, love of tight threepart harmonies from the bluegrass genre, and the shared commitment to making each song “as epic and memorable as possible.”

Jesse said that the band grew out of “a chance meeting at a local jam.” Soon after moving to Victoria, British Columbia, Jesse met Dylan Stone, who complimented his mandolin playing. As the two men began to play together in small local venues, Miriam Sonstenes and Dennis Siemens joined them. It was Stone who christened the band The Unfaithful Servants, after a song by the late Canadian musician Robbie Robertson.

Influences on the band’s sound include Robertson’s own group, The Band, as well as modern instrumental music,

newgrass revival, and old-school country. “The old-time way of folks just sitting down and coming up with music as a pastime has been the driving factor of the old-time influence,” Jesse explained. “When someone brings a song, much like learning old-time tunes, we may sit and play the song for hours, getting to know the melody and catching the right feel.”

As one learns more about The Unfaithful Servants and their dedication to storytelling and emotional substance, the fact of the six-year gap between the two albums is no longer a surprise. Both the careful curation of their material and their thoughtful craftsmanship have ensured that Fallen Angel is more than worth the long wait.

Grammy recipient Steve Smith produced the band’s first album in 2019. Despite the catastrophic hard freeze and the COVID-19 pandemic imposed on the music world, The Unfaithful Servants survived both the fluctuations of the post-pandemic concert scene and changes in band membership. The six years it took to rebuild the band “after the Covid times” and the additions of Mark Johnson and Quin Etheridge-Pedden brought revitalizing “capabilities, tools, and ideas,” Jesse said. Their songwriting has grown in depth and honesty.

“I believe the songs on Fallen Angel have come from pushing to record material that can be engaging instrumentally, while surrounding and supporting lyrics that are personal and raw,” Jesse said, further adding that the rhythmic ideas and lead lines from Johnson and Etheridge-Pedden have moved the band into exciting new territory.

Last September, when the band announced their first single, “Fallen Angel,” they expressed their excitement in an Instagram post about journeying into the world of bluegrass music. They described their sophomore album as carrying “the sound of the old world into a new light.” It is an unusual but apt description of all that The Unfaithful Servants offers in their new album. Their lyrical musings on mortality and the best and worst of human interactions today, the mournfulness in some songs serves to make the buoyant joy of their music all the brighter for the contrast.

Leading up to the album’s release in October, the band’s social media followers were treated to waterfront views of Canada’s many lakes and islands, evocative promotional photographs taken with a tintype camera, and more casual photos of band members with their dogs and a fierce-looking rooster.

The band is eagerly awaiting their upcoming tour stops, where they will play alongside Canadian folk singer Shari Ulrich, whom Jesse describes as “an icon.” It is a long way from Vancouver Island, in the westernmost province of Canada, to the most popular American music destinations, such as Nashville. The band’s enthusiasm appears to override any nervousness about their future and the very long journeys ahead. “We are excited to begin some touring in the US in the coming years,” Jesse said. “As a Canadian acoustic band, we are in a smaller niche community that exists in a more consistent, larger way in the States.”

“Negativity” is one of the last tracks on Fallen Angel, and one of the most deceptively simple. Without using clinical words such as depression or rumination, the lyrics accurately describe the destructive cycle of self-doubt. “All this negativity has defeated you and me for

the last time,” Stone’s plaintive voice rings out: “I hope before you die you realize you’ve been on the wrong track.” By the time the listener finishes the album and has basked in the “new light” of its memorable songs, they have heard enough to know that The Unfaithful Servants is without question on the right track.

They began gathering under a water tower in Portland, Oregon, high school kids who were into punk. Twenty years later, after busking bluegrass at freeway off-ramps, overcoming addiction, and navigating Los Angeles’ vibrant music scene, the band Water Tower is connecting with audiences of all ages through electrifying performances.

Last summer, the band played the Telluride Bluegrass Festival. It became the first bluegrass band to play the Vans Warped Tour, one of the largest events in the punk music world.

“We did Telluride and we did the Vans Warped Tour in the same week, so it was a career highlight,” says co-founder, fiddler, guitarist, and singer Kenny Feinstein. “There’s no higher you can go in the punk scene, and the same with bluegrass. They’re both at the very top. It’s pretty crazy for some punk rock bluegrassers from the freeway off-ramp.”

Though the band has punk roots, bluegrass is in its blood, from the traditional songs included in the setlist to the dark suits and bolo ties they wear on stage. One of their earliest influences was an acoustic string band that they instantly related to.

“The thing that turned us over was seeing Foghorn Stringband at a square dance, and they had this kind of punk rock energy in their fiddle tune playing. We just really dug that,” Feinstein explains.

every day and connect with fans, and also polish the fiddle tunes and polish the music. It’s a great way to test out 30-second clips on people, and just learn how to perform and be humble and really live in gratitude.”

The freeway busking also helped Water Tower learn to connect with people of all ages and backgrounds. Whether they’re covering a song by Blink-182 or playing a traditional breakdown, there’s something for everyone.

“A lot of people say we’ve got the tradition of bluegrass, the attitude of punk rock, and the culture of hip-hop,” says Feinstein.

He also says there was a fundamental benefit to the busking.

“Playing at the freeway off-ramps helped us kind of find our sobriety again, so sobriety is a big part of what we write about in our music.”

Water Tower’s focus is larger than addiction and sobriety and goes beyond the members of the band. Foremost, they say, is the welfare of the community that follows them. They’re called “owls.”

The band literally took to the streets to learn bluegrass after moving to Los Angeles and busking at freeway off-ramps.

“That’s how we paid the rent for the last ten to fifteen years,” says Feinstein. “It was a way that we could rehearse and have shows

“The owls are atop the water tower to make sure that no adulterants get added to the water supply,” says Feinstein. “Owls are wise, and they watch over the group and make sure everybody is safe, and that’s what our fans are. It’s a community where we look after each other. It’s not a fan base. It’s an actual friendship group and a place to keep people safe. We want to contribute to the lessening of suffering, and we want everyone to be included in our music. Water Tower is for the people.”

The band usually performs with five core members, but old friends, former members, and audience members are often called up to the stage during energetic, improvised sets. One of Water Tower’s unique characteristics is the use of two banjos in the band, which Feinstein says is kind of a punk rock thing.

“I always hear people saying that two banjos might be too many for the jam or whatever. Well, two of my best friends are the best banjo players I know, and I want them to play banjo in the band because their talents are so amazing. They have such different styles that they complement each other. Jessie Blue Eads is kind of a crazy prodigy. And Tommy Drinkard is more of a classic chainsaw Earl Scruggs player. Mixing them together is beautiful. Of course, it offends people when they see it, but once they hear the different styles, people fall in love with it.”

Two banjos might be the least of the surprises at a Water Tower show.

“Our genre is punk rock bluegrass--not bluegrass punk rock. We do bluegrass traditionally with a punk rock attitude, so the order is important,” says Feinstein, who also runs a marketing agency. “I’ll do a Snoop Dogg rap, and we will do punk rock songs, and so moving from Bill Monroe to Tupac is a jarring change for certain people. Plus, we dance, and the show is never very planned out, so crazy stuff could happen.”

In early 2026, Water Tower will continue to introduce bluegrass to new audiences when it opens for Nick Hexum, the lead vocalist for the multi-platinum alternative rock band 311. But Feinstein says the band will still work the off-ramps.

“We used to go out seven days a week, sometimes four to seven hours a day, just to make ends meet. But now we’re lucky if we’ll get out there a couple of times a month. People are receptive. They’re grateful that we’re bringing music to them in traffic. They’re super stoked on it, generally.”

by Candace Nelson

Appalachia isn’t just a landscape of rolling mountains and deep traditions it’s also home to a small but vibrant network of creameries and dairies producing highquality, locally made cheeses. While largescale dairying dominates much of the country, these artisan operations keep alive a tradition of farmstead cheesemaking tied to their land, animals, and communities. From goat milk yogurt to aged cow’s milk cheeses, the region’s creameries demonstrate a commitment to craft, care and flavor.

Located in the western mountains of Maryland, FireFly Farms produces awardwinning goat cheeses at its creamery in Accident. The farm handcrafts both goat and cow milk cheeses using only a few simple ingredients, without any additives or preservatives. Their production facility incorporates solar energy, reflecting a sustainable approach to cheesemaking. Visitors can explore the Deep Creek Market, where they can sample cheeses, browse local products, and enjoy wine-and-cheese pairings. FireFly’s cheeses are known for their rich, tangy flavors and creamy textures, with options ranging from fresh chèvre to aged rounds, each crafted to showcase the natural taste of the milk.

Tucked into the lush Sequatchie Valley on the Cumberland Plateau, Sequatchie Cove Creamery makes rustic, Savoie-inspired cheeses using raw milk from their own herd. Their signature Cumberland cheese is a Tomme-style wheel with a natural rind, intended to reflect the character of the Tennessee landscape. The founders, Nathan and Padgett Arnold, focus on regenerative farming, maintaining a close connection between their herd, the pasture and the cheesemaking process. Their offerings include a variety of semi-soft and hard cheeses, each developed to highlight subtle earthy and nutty notes while remaining approachable for all palates.

English Farmstead Cheese is a multigenerational dairy based in the mountains of North Carolina. The family raises Holstein cows and produces smallbatch cheeses including gouda, jack-style cheeses, cheddars and spreadables. Their products were sold in farm stores and local markets, emphasizing freshness and the flavor of milk sourced directly from the farm. Although the creamery retired as of 2025, English Farmstead Cheese played a notable role in sustaining small-scale, family-run dairies in the region, offering artisanal cheeses that balanced traditional techniques with a contemporary approach to taste and texture.

Set on 28 acres in Black Mountain, Round Mountain Creamery is North Carolina’s first Grade-A goat dairy. The farm raises Alpine and LaMancha goats, whose milk is pasteurized on-site and transformed into a variety of soft goat cheeses with distinct flavor profiles, from sweet to savory and even slightly spicy. The farm offers tours and tastings, allowing visitors to see the process from milking to cheese aging. Round Mountain’s cheeses are noted for their fresh, tangy flavors and smooth, creamy textures, which reflect the careful attention given to the herd and the artisanal methods used on the farm.

Whey Creamery

Shepherd’s Whey Creamery is a goat dairy located in the Eastern Panhandle of West Virginia. The creamery produces goat cheeses, “Goatgurt” yogurt, and other cultured goat milk products. Some of their cheeses are aged in a cave-like environment, allowing the flavors to develop complexity

while preserving the character of the goat milk. Their products range from soft and spreadable varieties to more aged offerings with firmer textures and tangier profiles. Shepherd’s Whey emphasizes quality, care and sustainability in every step of the cheesemaking process, maintaining a smallscale approach that highlights the unique qualities of their milk.

Meadow Creek Dairy is a farmstead cheesemaker located in the foothills of the Blue Ridge Mountains. They produce raw-milk cheeses from a Jersey-style herd, focusing on the nuanced flavors of milk derived from pasture-raised cows. Their cheeses are aged to bring out a rich, nutty and earthy profile, with textures ranging from semi-soft to firm. Meadow Creek’s cheesemaking combines traditional methods with attention to the seasonal variations in milk, resulting in cheeses that reflect the rhythms of the farm and the character of the mountain pastures.

From Maryland to Tennessee, North Carolina, West Virginia, and Virginia, these

creameries illustrate the diversity and craftsmanship of Appalachian cheesemaking. Each farm is rooted in its landscape, drawing flavor and character from the animals and the pastures they graze. Whether producing fresh chèvre, creamy yogurts, or aged tommes, the region’s artisanal dairies provide a taste of Appalachia that is both traditional and distinctly local. By maintaining small-scale, farm-focused operations, these creameries continue to keep the craft of cheesemaking alive while offering products that are fresh, flavorful and deeply connected to the land.

Across rolling hills and quiet valleys, the dedication of these farmers and cheesemakers ensures that high-quality, handmade cheeses remain an enduring part of Appalachian culinary heritage. Visitors and cheese lovers alike can experience the textures, aromas, and flavors that come from careful attention to milk, time-honored techniques, and a deep respect for the farm. These six creameries are just a glimpse of the broader landscape of artisanal dairy in the region, showing that Appalachia’s connection to agriculture is as rich and layered as the cheeses themselves.