Richelle Putnam holds a BS in Marketing Management and an MA in Creative Writing. She is a Mississippi Arts Commission (MAC) Teaching Artist, two-time MAC Literary Arts Fellow, and Mississippi Humanities Speaker. Her fiction, poetry, essays, and articles have been published in many print and online literary journals and magazines. Among her six published books are a 2014 Moonbeam Children’s Book Awards Silver Medalist and a 2017 Foreword Indies Book Awards Bronze Medal winner. Visit her website at www.richelleputnam.com.

Rebekah Speer has nearly twenty years in the music industry in Nashville, TN. She creates a unique “look” for every issue of The Bluegrass Standard, and enjoys learning about each artist. In addition to her creative work with The Bluegrass Standard, Rebekah also provides graphic design and technical support to a variety of clients. www.rebekahspeer.com

Susan traveled with a mixed ensemble at Trevecca Nazarene college as PR for the college. From there she moved on to working at Sony Music Nashville for 17 years in several compacities then transitioning on to the Nashville Songwritrers Association International (NSAI) where she was Sponsorship Director. The next step of her musical journey was to open her own business where she secured sponsorships for various events or companies in which the IBMA/World of Bluegrass was one of her clients.

Susan Marquez is a freelance writer based in Madison, Mississippi and a Mississippi Arts Commission Roster Artist. After a 20+ year career in advertising and marketing, she began a professional writing career in 2001. Since that time she has written over 2000 articles which have been published in magazines, newspapers, business journals, trade publications.

Singer/Songwriter/Blogger and SilverWolf recording artist, Mississippi Chris Sharp hails from remote Kemper County, near his hometown of Meridian. An original/founding cast member of the award-winning, long running radio show, The Sucarnochee Revue, as featured on Alabama and Mississippi Public Broadcasting, Chris performs with his daughter, Piper. Chris’s songs have been covered by The Del McCoury Band, The Henhouse Prowlers, and others. mississippichrissharp.blog

Brent Davis produced documentaries, interview shows, and many other projects during a 40 year career in public media. He’s also the author of the bluegrass novel Raising Kane. Davis lives in Columbus, Ohio.

Kara Martinez Bachman is a nonfiction author, book and magazine editor, and freelance writer. A former staff entertainment reporter, columnist and community news editor for the New Orleans Times-Picayune, her music and culture reporting has also appeared on a freelance basis in dozens of regional, national and international publications.

Candace Nelson is a marketing professional living in Charleston, West Virginia. She is the author of the book “The West Virginia Pepperoni Roll.” In her free time, Nelson travels and blogs about Appalachian food culture at CandaceLately.com. Find her on Twitter at @Candace07 or email CandaceRNelson@gmail.com.

A Philadelphia native and seasoned musician, has dedicated over forty years to music. Starting as a guitar prodigy at eight, he expanded his talents to audio engineering and mastering various instruments, including drums, piano, mandolin, banjo, dobro, and bass. Alongside his brother, he formed The Young Brothers band, and his career highlights include co-writing a song with Kid Rock for Rebel Soul.

Stephen Pitalo has written entertainment journalism for more than 35 years and is the world’s leading music video historian. He writes, edits and publishes Music Video Time Machine magazine, the only magazine that takes you behind the scenes of music videos during their heyday, known as the Golden Age of Music Video (1976-1994). He has interviewed talents ranging from Ray Davies to Joey Ramone to Billy Strings to Joan Jett to John Landis to Bill Plympton.

by Jason Young

“I’m as independent as they come.”

“It’s been an interesting year,” says singersongwriter Jack McKeon, who, just a few years back, hitched his Honda Civic to a five-by-eight U-Haul trailer and headed to Nashville in pursuit of getting his songs heard.

Armed with a talent for storytelling, he left behind his small hometown of Chatham, New York. Three years later, McKeon self-financed his debut album, Talking To Strangers, earning praise for its song lyrics, musical arrangements, and blend of bluegrass, country, and folk-rock.

To keep things afloat, he works as a carpenter while balancing his schedule with writing, touring, and, more recently, playing with other artists.

“I kind of stumbled into playing in other people’s bands,” says McKeon, who just finished a string of shows on the West Coast. “I was out there [California] for a week playing guitar and singing harmony for Fancy Hagood. It’s crazy because in the middle of the tour, I flew to South Carolina to do one of my shows.

“It’s tough playing in a bluegrass band,” shares the Nashville resident. “This is not a dis on Americana or country, but the bar is so high for instrumentalists in bluegrass. I kind of left that door closed,” says McKeon, who also plays mandolin.

McKeon is grateful for the invitations.

“I was like, ‘I’m gonna say yes and if I blow

it, then that’s that.’ I can learn how they run their band, how they book their shows and how they book their tours,” shares McKeon. “All these opportunities are coming from artists who I really respect and appreciate.”

Being independent has its ups and downs.

“I’m as independent as they come these days. I think it’s difficult to grow as an artist when you are juggling so many things. It’s a rite of passage for so many artists, though. Honestly, I’m not very good at it,” explains McKeon about being his own booking agent. “It’s one of the hardest things for an independent artist.”

McKeon says he benefits from house shows.

“Those shows are so important, especially when you are at a [lower] level. I was down in Kerrville, Texas, playing the Kerrville Folk Festival when I met a guy who hosted me at a house show in Austin.”

Going on, “There was a lady at the show who really loved it, and she ended up inviting me and another Austin songwriter to perform at her house show. It was only fifty people, but it was a great way to connect to a new audience.’”

The songwriter says he is always welcomed in Texas when traveling around the country.

“I’ve always done decent in Texas. They love songwriters, and I have always had a receptive audience there. I have done a lot of songwriter contests in Texas, like the Kerrville Folk Festival. Texas is just one of those states that cares about live music in general—especially anything country or country-leaning.”

McKeon’s storytelling lyrics and rural

North American accent combine to create his unique style; something he admits that he never worried about.

“I think it’s more intuitive to let the songs that you are writing lead you to your style. The first record, Talking to Strangers, has straight-ahead bluegrass moments, strippeddown singer-songwriter moments, and songs that probably could have had pedal steel and drums on them.

“I want my style to be defined as something that remains fluid,” shares the independent artist. “This batch of songs that I hope to have finished in the next month is a departure from my first album. It has a wider range of influences.”

McKeon cites John Hartford as a major influence on his music.

“My best friend’s parents were hosting a picking party, and there was a band there that played the John Hartford song, ‘Up on the Hill Where They Do the Boogie,’ and it blew my mind! The music was rooted in a history I knew nothing about. I would listen to John Hartford’s Aereo-Plain album and hear Norman Blake, then find out that Blake made a record with Tony Rice. It was amazing!”

The native New Yorker doesn’t regret moving to Nashville.

“If you expose yourself to other writers, you are going to get better by osmosis. I am so grateful and lucky to fall into the group of songwriters I met here in Nashville. I took the same crappy Honda Civic I’m driving now and moved my whole life down here. It’s just an amazing place!”

by Stephen Pitalo

Some bands begin with ambition. Ruby Joyful began with love.

Dan Rubinoff had played in small local bands most of his life, but he says, “I never wrote a good song until I was 50 years old. Joyce and I met eight and a half years ago. It opened up the creative pathways and all of a sudden I was writing good music.” That spark led to more than just a few songs. It led to a new life.

Ruby Joyful, the band Dan co-founded with partner and bassist Joice Moore, came together in Paonia, Colorado. Their relationship quickly evolved into a creative partnership. “We fell in love immediately. We are still in love, like crazy. Every day is like a honeymoon for us. It never changes.” Joice had never played music before, but Dan, a longtime musician, encouraged her. “We got her to play the bass, which is what all good boyfriends do,” he laughs.

Ruby Joyful played local gigs—what they affectionately called “wheelbarrow shows” at the neighborhood brewery, because they literally wheeled their equipment over. “We didn’t have a name ‘cause we kept switching people all the time,” Dan says. “This guy had just come back from hiking a mountain over in Crested Butte called Oh Be Joyful. He said, ‘You’re Rubin, ’ & she’s Joice, so let’s call you Ruby Joyful.’ It was just totally quick, and the name has stuck ever since.” But the hobby turned into something more when Dan invited longtime friend Drew Emmitt to sit in on a show for Colorado congressional candidate Adam Frisch. Emmitt agreed, and that evening changed their fate. “We had dinner with Drew after the show, and I told him about the recording experience. I was like, man, it’s fun, but it just doesn’t sound good. Nobody’s gonna think it sounds good. And I said, ‘Hey, would you

consider playing a couple of licks on it?’ And he looked up and said, ‘Sure, absolutely.’” Drew opened the floodgates. He helped connect Dan to Nashville engineer Mark Mirro, who had just taken over Snowmass Creek Studios, initially built by Glenn Frey. Before long, Dan and Joice were recording with some incredible talents. “Before we know it, little Joyce and I from little Paonia, Colorado, are in the studio with Drew Emmitt and Andy Thorn on banjo and Eli Emmitt, Drew’s son.”

From there, the project snowballed. Stewart Duncan joined the recording in Nashville. “I paid him to do two tracks. And while we were in the studio with the engineers, we all looked at each other, we’re like, we gotta keep him going. So he ended up doing six tracks.”

Dan called up Rob Ickes to join a short tour. “I said, ‘I know you don’t know me or anything, but I’m playing a few shows in Colorado with Drew and Andy, would you consider it?’ And he said, Yes. And my heart just dropped.”

The record title, The Pie Chart of Love, is inspired by a piece of pop art Dan created that still hangs in their home. “I started doing big canvases that connected love with seventh-grade math principles. So, I did the pie chart of love, the Venn diagram of love, and the line graph of love…”

Every song is rooted in their love. “Everything about the album is basically about our love. It just is. It’s what it is. Every show we’ve done, every song, it’s what we do. And to play with her is a dream for me, honestly.” Despite its success—radio airplay, folk chart rankings, and a publicist campaign— Dan and Joice didn’t want to dive into the industry. “We’re not music business people.

We didn’t do the internet-savvy thing. I’m not interested in winning an internet popularity contest.”

Instead, they found a calling that felt more purposeful. “We literally get in the van and tour around the west, just playing at children’s hospitals,” Dan says. “It has completely won our hearts over from everything else.”

Their first experience in that realm of performance came in Greece in 2018, playing for children with terminal illnesses. It deepened after Dan played music for his mother, who had advanced Alzheimer’s. Later, at Denver Children’s Hospital, their experimental visit changed everything. “One hour with kids hooked up to infusion machines would blow the doors off of any sold-out performance we’d ever be doing.”

The songwriting never really stops. Even while biking in Alaska, Dan is writing for a

program called Song Story, where musicians compose from stories written by terminally ill children. “That’s my one assignment on this trip—to write a song… I’m actually supposed to record it before I get home.”

When asked about favorite tracks, Dan points to “All My Friends Got More Money Than Me.” “It was so sweet and so productionwise… I can’t even believe that’s my song,” he says. He also highlights ‘The Same Day,’ a tribute to their devotion. “We decided a long time ago that if we ever died, we’d have to die on the same day because neither of us could stand living one day without each other.”

As for the future of Ruby Joyful?

“We made it, we did it. It’s beautiful. And I think if it comes again, sure. But the stress of keeping a band together, paying everybody and keeping everybody working… eh. I think we’re enjoying life too much.”

by Susan Marquez

Dig Deep String Band is a unique and powerful force in the roots world with a hard-edged sound far beyond bluegrass. All the band members come from a punk music background, but band spokesman Alex Dalnodar says he got into bluegrass when he walked into a tavern and heard the 357 String Band. “Joseph Huber in 357 is an endless well of inspiration. We would not exist as a band if they had never existed.”

The Stevens Point, Wisconsin-based band formed in 2015. “Stevens Point has a vibrant music scene. We bonded over the shared inspiration of traditional bluegrass and the love of rock n’ roll,” says Alex. “We have combined decades of hard gigging in the punk/metal scene.” The members

of Dig Deep all left a cow punk band called The Ditchrunners. “We played a lot of country cover stuff. But we became a unit and started writing together.” The members re-formed, and the only change was the bass player. They adopted the name Dig Deep, and now they play regionally, in roadhouses, local bars, and festivals, but they have done a coastto-coast tour and have been talking about playing abroad. “We did a tour with Steve’n Seagulls, who did AC/ DC covers. We would really like to do more stuff like that.”

Attending a Dig Deep show is an energizing experience. Much more than a string band show, Dig Deep String Band is known for its boisterous performances. The

Milwaukee Record described them as “the bluegrass equivalent to a ‘dogs playing poker’ painting. It’s casual, but still professional and friendly, but also very metal,” and “footstomping rhythm, sing-along harmonies, and infectious mandolin and banjo picking.”

Members of the band include Alex (guitar/vocals), Oscar Noetzel (banjo), Aaron von Barron (bass), and Bob Weigandt (mandolin). The release of their album, Heavy Heart, coincided with the COVID pandemic, which trashed their plans for a tour. Other albums include Live in Denver (11.121.24), Lair of Hodag (2024), and Dig Deep (2015). The Lotta Morgan is an album released on vinyl in September 2017. The songs on the album chronicle the murder of a beloved film actress in Hurley, Wisconsin, during the great Northwoods mining boom. A description of the album on discogs.com says, “with characteristic vision, craft, and clout, the four-piece group firmly establishes their ground outside the realm of conventional Americana while exploring sonic and literary territory that plumbs the depths of power and weight.” Alex says, “It’s a noteworthy release.”

According to Alex, 75% of what they play are original tunes. They dropped two albums last year, so touring has been a priority this year. “We definitely have some songs brewing,” says Alex. “We may try to get into the studio this winter. The plan is to finish a new album in the spring and release it next summer.”

The band hosts a music festival in Stevens Point each February called Tip-Up Pike Jam. “My family does it, and yes, it is an outdoor festival in Wisconsin,” says Alex, “It has an ice fishing tournament, live music, and more, and a lot of people from the bluegrass community turn out. We raise money for a local non-profit called Jessie’s Wish.” The festival celebrated its seventh year this year. Check the Tip-Up Pike Jam Facebook Page for the 2026 festival dates.

To get a taste of Dig Deep String Band, click here for a video of their tune, “Heavy Heart,” the title song from their 2020 album.

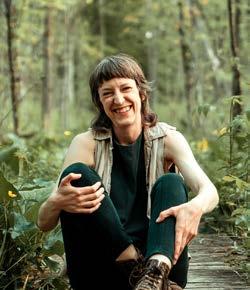

by Stephen Pitalo

Long Mama doesn’t ask for your attention the songs demand it. Stark and searching, cinematic and punk at heart, the music rides the tension between beauty and blunt force like it’s born from both. If you’ve ever had your heart cracked open by a stranger’s voice on the radio, there’s a good chance you already know what Long Mama sounds like. Or at least how it feels.

Behind the name both the band and the moniker is Kat Wodtke (pronounced “Woodkey”), a Riverwest-based songwriter, vocalist, and storyteller whose music glows with both candlelight and wildfire. Wodtke (they/them/she/her) is Long Mama and Long Mama is a vessel for the kind of truth-telling that doesn’t blink.

“It was always just me and whichever group of friends I could cobble together to play with me,” Wodtke says of the early days, playing solo in Milwaukee and Alaska bars and cafés. “Our name was always changing.”

But something shifted when the current band began to take shape with collaborators Nick Lang and Andrew Koenig.

“We started to feel like something special was going on in the room when we played together,” Wodtke remembers. “They are such good listeners and patient, open collaborators.”

So came the name unearthed, fittingly, from a night spent researching cactus varieties. “I spent a whole night looking at common names for different cacti and learned that a ‘long mama’ cactus prefers shade to sun and can survive cold weather. It felt right for an alt-country band from snow country,” they say. “The cactus itself also looks like a very prickly/angry piece of human anatomy, which resonated with me in particular. I am not a songwriter who is afraid to provoke or ruffle feathers. It is a musician’s job to make people think and stir the pot.”

That blend of toughness, dark humor, and survival threads through everything Wodtke writes. On Poor Pretender, Long Mama’s debut full-length album, songs crackle with stories that are as lived-in as they are literary. No wonder. Wodtke’s roots are steeped in books and storytelling as much as in music.

“I am such a nerd and proud of it!” they say, laughing. “I can’t thank my cool parents enough for instilling a love of reading in me and also a deep appreciation for the arts and the outdoors. They gave me a lot of freedom to run around in the woods as a kid and cultivate my imagination and curiosity.”

While Wodtke studied Theatre Arts in Minneapolis and grew up in a home spun with Carole King, Aretha Franklin, and Bach, they found a love for the unvarnished poetry of punk and country in high school.

“A bunch of my friends played in punk bands that would perform in basements or garages,” they say. “No one I knew played in a country band, but we started listening to the old (good) stuff and also discovered newer artists like Caitlin Rose, Rachel Ries, Bright Eyes, Mountain Man, and Jolie Holland.”

What drew them in wasn’t just the sound it was the shared ethos.

“I think I was excited to find folk and country music that sounded great and had the subversive ethos of punk,” Wodtke says.

Long Mama’s genre-bending songs gritty and graceful, punk-rock and twang-tinted come together not by planning, but by following instinct.

“It’s very organic. We experiment, play, and arrange until it feels right,” they say. “We try not to think about genre and let the song lead the way. My musical collaborators do an incredible job of underlining certain lyrics or capturing a setting or feeling with the way they play.”

The way Poor Pretender was recorded reflects that approach live, in the same room, in the middle of a snowy weekend, with just enough warmth and grit to feel like an attic session shared with friends.

“Our co-producer and engineer Erik Koskinen has a great studio for live recording,” Wodtke explains. “It also feels like a cozy, northwoods cabin inside, so we felt right at home there… I think the album captures what we sound like live, which is really cool and an increasingly rare way to record. It doesn’t sound overproduced. It sounds like us.”

You hear it in the breath between notes. The banjo that sneaks in late. The laugh that nearly breaks mid-verse. These are not pristine, polished songs; they’re lived-in wrinkled, bruised, tender exactly how Wodtke intends them to be.

“I find tenderness to be gritty and brokenness to be really beautiful,” they say. “Life is messy, and hard things can be equal parts excruciating and hilarious. So it’s not tension for me. I think these things co-exist in the human experience.”

Much of Poor Pretender was shaped in the wake of loss a dear friend’s passing that shifted Wodtke’s songwriting from cautious to candid.

“I think I became more willing to be open and vulnerable about mental health in my writing,” they share. “My friend who died was battling depression, and I found myself struggling with that a lot in the wake of losing her… I think a commitment to music became more deeply rooted in me. Not necessarily as a career path but as something I will always need to experience and make.”

Grief and joy don’t exist separately in Wodtke’s writing they collide. And in that mess, Long Mama finds its voice.

“Grief and joy are so interconnected. Each deepens the other,” they say. “I just try to be honest and plain-spoken about it in my songwriting. No human is just one thing, and no song needs to be just one thing. We can be many beautiful, broken, tender, gritty things at once.”

That philosophy pulses through every Long Mama track, whether it’s the ballad of a busted romance or the imagined voice of a ghost wandering a prairie. Wodtke builds characters and sketches scenes like a playwright with a steel-string guitar, unafraid to drift from the autobiographical to the fantastical if it means hitting something true.

“With my songs, I like to experiment with inhabiting characters in the first person (see ‘The Narrows’) or making a semi-true story larger than life (see ‘Badlands Honeymoon’),” they say. “I also like taking something really mundane and mining it for beauty or meaning.” In the hands of a lesser songwriter, it might all fall apart. But Wodtke makes it stick not by smoothing the edges, but by sharpening them.

“I just love taking in any kind of art it cracks open my brain in the best way possible, and I feel like I can’t not riff in my own work on whatever it made me feel or think about.” In Riverwest, not far from the Milwaukee River where they grew up, Wodtke writes in the drafty attic they’ve made their creative home. They rake through notebooks, seeking not perfection but presence songs that feel like showing up, again and again, even when it hurts. Especially when it hurts.

Long Mama’s music isn’t background. It’s the kind of sound that sits with you when the fire goes out, the friends leave, the whiskey hits, the silence closes in. It knows what you’ve lost, and what you still have to give. And maybe that’s why it sticks.

by Stephen Pitalo

Elephant Revival has always carried a certain mystique. Their music—often called “transcendental folk”—is a blend of Celtic reels, Americana grit, bluegrass tradition, and ethereal tones that drift into indie rock territory. This audience connection stems from the band members’ intention to create not just a set of songs, but an experience. As for the band name, the story begins not with a stage but with elephants in a zoo.

“Our bassist, Dango Rose, was busking at the Lincoln Park Zoo in Chicago in front of the elephant cage,” said Bonnie Paine, the band’s voice and main soul. “He told me about two elephants that had lived together for 16 years. One of them was bought by the Salt Lake City Zoo, and sadly, it died during transport for unexplained reasons. The other elephant also died shortly after, and Dango’s theory was that it was from heartbreak.

They’re tribal creatures, not meant to be kept in cages, and especially not separated once they bond.”

That story was followed by a simple text about an “elephant revival concept” with dates and venues. “I thought, that’s an interesting name, and we’ll just put it in as a temporary name for those shows. And then we never changed it.”

The official first show came at the Gold Hill Inn in Colorado in 2006, where everything clicked into place. “It was beautiful, exciting, and so different from anything I had ever played. I had just started singing more and really felt my place in the music with my voice. It felt fearless, which was such a change for someone who had always been pretty shy.”

Bonnie’s influences reached back to her family home. “I grew up playing music with my sisters. We used to back up this old fiddle wizard—people called him the Jimi Hendrix of the fiddle—Randy Crouch. He definitely influenced me. My dad also had this phenomenal record collection with Nina Simone, Billie Holiday, Muddy Waters, Joni Mitchell—anything I wanted to listen to. That was really inspiring.”

Those sounds mixed into the musical bouillabaisse, along with Radiohead, African drum troupes, and the Celtic tradition brought in by fiddler Bridget Law. “I love percussion instruments—it’s fun to sing with them. And the musical saw adds its own little effect on the music, of course.”

Elephant Revival’s concerts are famous for their atmosphere, which is a quality Bonnie

likens to ritual. “We want to create an enveloping experience. I’ve played music at a few births and a few deaths, and it’s a similar feeling of setting a tone, having a little ceremony together, and letting music be the conduit. I try to stay open to how the music wants to move through the room. There’s this reciprocated energy between the audience and the band that can grow and grow throughout the evening, almost becoming tangible by the end of the night.”

That sense of fragility came into sharp focus after a near tragedy in 2016, when the band’s bus caught fire before a show. “I kept having this recurring dream on the bus while we were driving. So, then we’re driving along, and I hear this hissing sound from my bunk, and I realize it was fire at my feet in the bunk below me. It was an electrical fire. I woke up and we all ran off the bus. Most of our instruments burned because our driver wouldn’t let anyone go back on board.”

With the bus still smoking outside the Hickory, North Carolina venue, the band borrowed instruments from fans and even an antique store. “I found an old washboard in a shop since mine had burned, and somehow my musical saw survived. With that, we were able to play the show that night. We were a little shell-shocked, but we did it.”

The band’s last album, Petals (2016), carried a deep vulnerability. “That album was a very different kind of opening up for me. It was the first time I performed on cello in front of anyone. Until then, I had only ever played it alone, and it felt almost impossible to imagine playing it in public. It was my first melodic instrument in the band, instead of percussion, and it gave me a new way to convey songs.”

Those songs, she says, were part of a much larger cycle she has been crafting since childhood. “I’ve been writing a story-song cycle since I was a little girl, and there are now 28 songs in it. Three of them ended up on Petals. The main character is Raven, and part of the story is about a selkie—a water spirit—who falls in love with a human. It’s a long saga that begins there.”

Perhaps no show sums up Elephant Revival’s magic better than Red Rocks in 2017, played in a downpour. “It was so beautiful. One thing I love about the rain is that everything suddenly feels more connected, almost like an electrical current that runs through it all. There’s a palpable awareness of being in it together, and at Red Rocks, with water on the stones and that many people sharing the moment, it was just gorgeous.”

After a hiatus in 2018, the group reunited in 2022 with guitarist Daniel Sproul replacing Daniel Rodriguez. “The other bandmates’ enthusiasm for the music was so strong and

sweet. When we got together, it just fit beautifully, and we remembered the love we had for playing together.”

The band has been back in the studio with producer Tucker Martine, a dream collaboration years in the making. “Recording with Tucker was seamless, playful, and very beautiful. We’d wanted to work with him for a long time, and it was such an honor.”

For Bonnie, the future feels wide open. “The most amazing things that have happened in my life weren’t things I could have dreamed of exactly as they turned out. You just never know. The new songs we started recording are going to be beautiful, and I’d love to expand on our collaborations with the Colorado Symphony. We played with them recently, and the sound was incredible—I’d love to have orchestrated recordings of that someday.”

Elephant Revival remains a band that turns stages into ceremonies, melodies into lifelines, and hardship into song. As Bonnie puts it, “I feel this effortless connection when we play live. It amplifies the music in a whole other way. The reciprocation between us and the audience is really beautiful.”

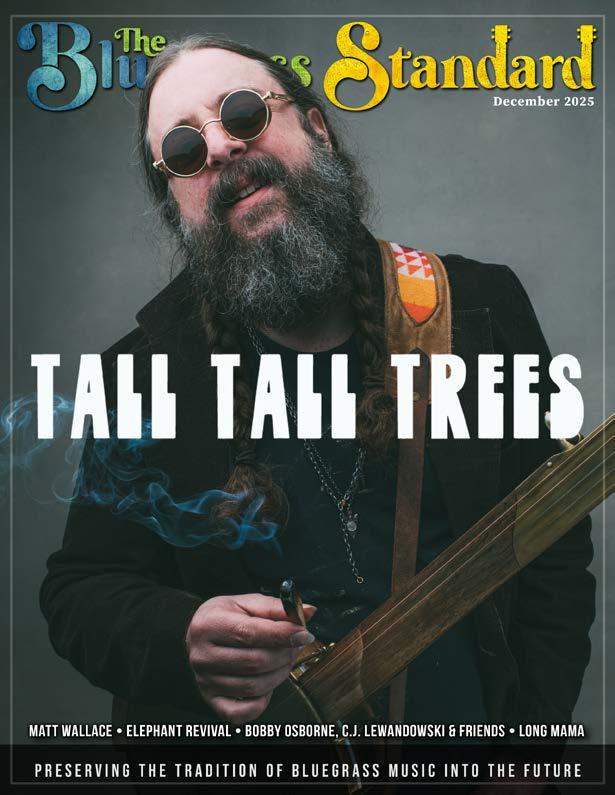

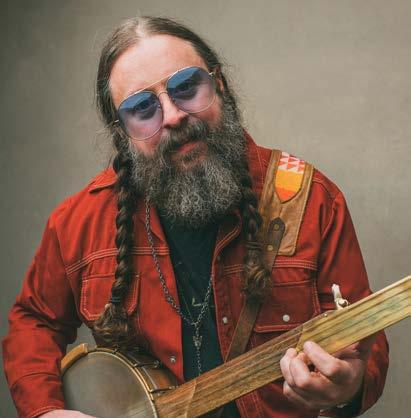

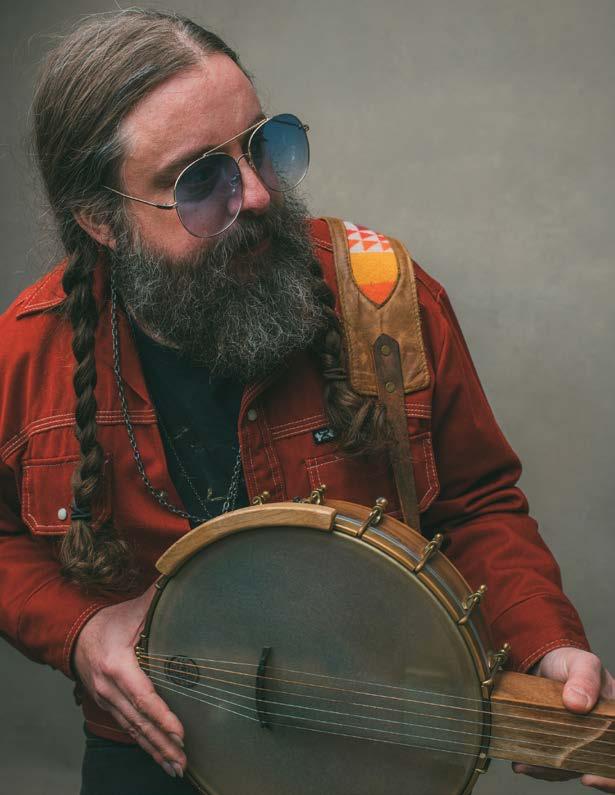

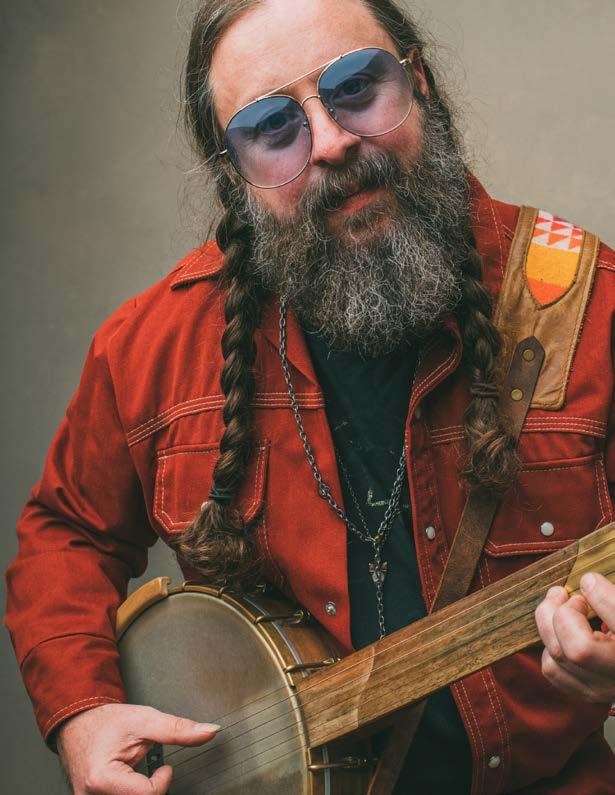

by Stephen Pitalo

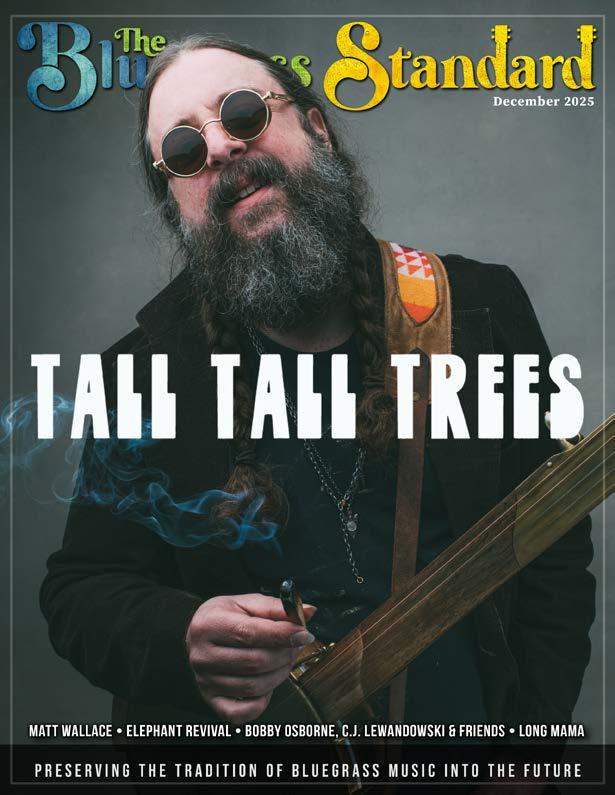

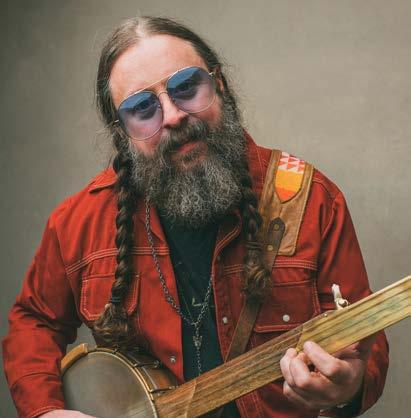

Don’t try to put Mike Savino in a box. He performs as Tall Tall Trees, a name spurred by a tune written by Roger Miller and George Jones. Inspired by the pioneers of experimental banjo music (Rhiannan Giddens, Bela Fleck), Savino is a one-man psychedelic indie-folk orchestra. That box had not been invented until Savino’s experimental nature created it. He plays his music on his “Banjotron 5000,” and has been described as “a new age Cat Stevens with dreamy harmonies.” In other words, while it may be complex, Savino’s music is easy to listen to.

“Not fitting in a box has been both a blessing and a curse,” he says. “I’ve always been a bit of a musical explorer, and that tends to make my music unclassifiable. I’m the weird one at the bluegrass festival.”

A native of Long Island, New York, Savino lived in New York City for twenty years before moving to Asheville, North Carolina, a decade ago. “I didn’t grow up in a musical family,” he says. “I grew up in a New York Italian family – I discovered music in school. I played the saxophone in elementary school and progressed to playing in the jazz band. The director saw a spark in me and gave me a baritone sax.” Savino says an older kid played the bass guitar, and he really liked it. “I got my first bass guitar when I was 12 years old. That musical training has carried me through life.”

After graduating high school, Savino attended a music conservatory in New York, where he played jazz on a double bass. Someone gave him a banjo while he was in college, and he tinkered around on that, playing songs. After college, he traveled and went deep into Brazilian music. “I had an electric bass with me. In the evenings, locals would jam in the town center. It was all acoustic instruments, and I was bummed that I couldn’t play with them, so I bought a cavaco – a four-stringed street banjo.”

Finding himself in a “jazz coma,” Savino began writing songs on the banjo for fun. “I ended up playing the songs out of left field in 2004 or 2005, and I began experimenting and pushing sounds, manipulating the banjo to see what I could get out of the instrument.” He began playing with a band called Tall Tall Trees. “I began using loop technology to write music, and we would play happy hour shows for two hours straight. We did that every Monday for a few months and began to draw a regular crowd.”

When he lost his drummer, Savino says he used a mallet to lightly beat on his banjo. “I realized I could really wail on it. I could play chords and drums at the same time.” When the artist Kishi Bashi hired Savino as his backup band, it allowed him to tour solo. “It was more affordable, so I hit the road as an ambassador for Tall Tall Trees.” Kishi Bashi did a one-man loop show with violin, and now, 15 to 20 years later, Savino says he is still inspired.

Savino’s music has a strong psychedelic tone, and his music videos reflect that. “I have had some cool conspirators,” he states. “I’m a pro-psychedelic person, and I attribute my musical curiosity to bands like The Grateful Dead and Phish. They were my gateway drug to jazz music.”

Savino says he is also into metaphysics and the spiritual world. “I believe there is a deeper layer to what’s happening around us.”

His musical progression was influenced by Bela Fleck and the Flecktones in the 1990s. “I always had strange records and tapes,” he laughs. “I listened to a lot of the Flying

Burrito banjo time Trees

One is admittedly like it’s Savino with something

https://talltalltrees.com herehttps://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CIWIOZQBFwY

Burrito Brothers, Flatt and Scruggs, and the Eagles – “Early Bird” has some amazing banjo playing. I love how Rhiannan Giddens plays clawhammer banjo and brings old time to the forefront, and Bela Fleck is still pushing boundaries.” The name Tall Tall Trees is his homage to Roger Miller. “I was obsessed with him early on as a songwriter. One song could break your heart, and the next made you laugh.” While “Tall Tall Trees” admittedly not Savino’s favorite song, he likes the name. “I like the alliteration, and I like that TTT looks like a stand of trees. And it’s kind of funny – it’s a plural name, but it’s just me on stage.”

Savino is working on a new acoustic banjo record. “It’s a cross between old-time banjo with psychedelic flourishes, with a lot of round-peak clawhammer style playing. It’s something totally different for me.” The album is due out early 2026.

https://talltalltrees.com To see Tall Tall Trees play at The Kennedy Center, click herehttps://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CIWIOZQBFwY.

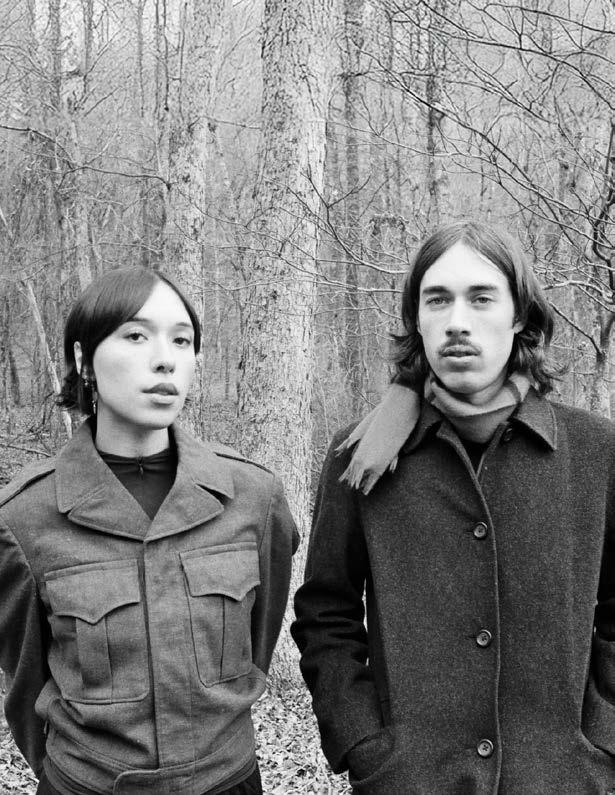

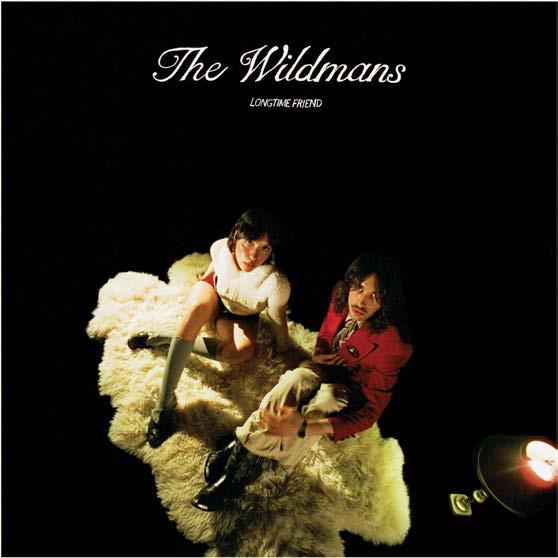

by Brent Davis

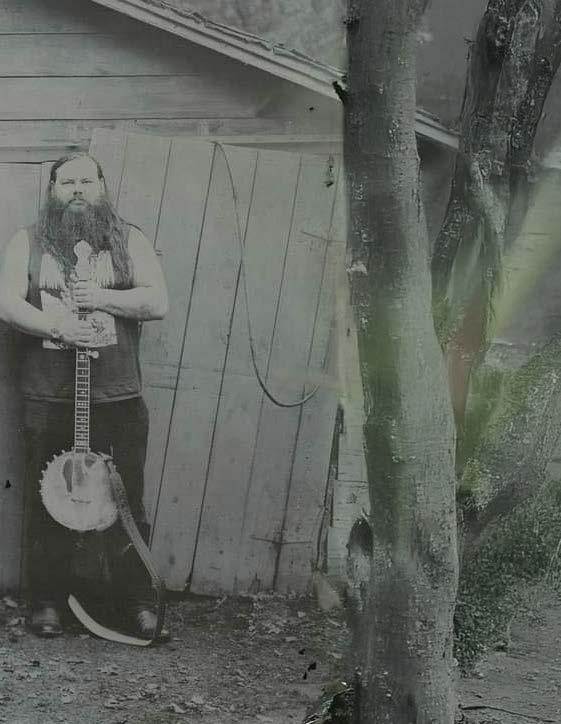

Just a few years out of Berklee College of Music, brother and sister Elisha and Aila Wildman, performing as The Wildmans, seem like fresh new faces on the roots music scene. But owing to the vibrant, legendary old-time music scene around Floyd, Va., where they grew up, fiddling, singing, and strumming have always been part of their DNA.

“We grew up kind of going to the Floyd Country store every Friday night for a really long time,” says Aila. “They do the Friday night jamboree where all the old timer musicians kind of come out and play. That was definitely what got us into playing music.”

“The other aspect of the old-time music scene in Floyd is all these fiddle conventions that are unique to this region,” Eli explains. “I remember going to the Galax Fiddlers Convention--Aila must have been five years old and I was seven--and that was the first time we saw a mandolin in person. And we continued going to other conventions like Fries, Elk Creek, Mount Airy, and Clifftop. And that was hugely inspiring to us. So it’s a kind of community that we got to know, and also gave us something to work towards, to learn a song and be able to play it in front of a bunch of people on stage.”

Rather than preserving the traditional sounds of their native region on their new album, Longtime Friend, The Wildmans instead imaginatively combine their acoustic roots and their Berklee College experiences to create music that defies limits and labels. Aila’s vibrant, authentic fiddling combines electric guitar, evocative percussion, and the siblings’ blood harmonies on compelling original songs, old fiddle tunes, and striking covers, including two Graham Parsons numbers. It’s a different sound from their

first album, which more closely reflected their traditional music upbringing.

“This one feels like a huge growth and representation of ourselves musically coming from all our time at Berklee and just kind of growing,” says Eli. “And channeling out more of our inspirations from our early years as well as now.”

The variety of material on the album is striking. “Autumn 1941” is a chilling account, based on a true story, of an Appalachian mother protecting her daughter from outsiders. “Luxury Liner” is a rollicking rendition of Graham Parsons’s classic that showcases Aila’s singing. “Old Cumberland” and “The Route” are fiddle tunes that soar in unique arrangements with electric guitar and drums.

“I think that’s something that just happened naturally from playing with (producer and percussionist) Nick Falk,” says Eli. “And then Sam Leslie learned the tunes on electric guitar. We kind of just put him on this little tiny amp far away in this huge room we were playing in, so we could all hear the guitar at the volume of our acoustic instruments. It’s almost referencing the banjo, and it almost sounds like it has an African influence to me.”

Eli’s guitar and mandolin playing and Aila’s fiddling are products of their old-time roots. But they are accomplished vocalists as well. Aila’s lead singing allows the duo to take on practically any song that intrigues them.

“I can remember singing for as long as I can remember,” Aila says. “I just always wanted to sing.”

“Our parents were always playing us Bonnie Raitt and Canned Heat and Stevie Ray

Vaughn--all these incredible vocalists,” Eli adds. “A lot of blues, a lot of that 60s, 70s music, and a lot of folk revival music. So we always had that influence of the vocal aspect. And for me, I think Doc Watson was one of my early singing influences. And we loved Nickel Creek growing up. They were a huge influence.”

Aila, who finished at Berklee a year and a half ago, has returned to Floyd, which, for now, The Wildmans call home when they are not touring.

“Right now, it makes sense when we’re thinking about saving money,” Eli explains. “But we have a lot of friends on the New York City scene. One of our best audiences is when we go to play in New York City, and we have an audience full of twenty-

something-year-olds, which is pretty cool to see. We’ve had people tell us, ‘I don’t know what that fiddle’s doing, but it makes me want to dance!’ And that’s awesome. But right now, Floyd’s working out well, so we’re really fortunate to have a beautiful place to be where our parents live and where we grew up.

“The goal is to be self-sufficient and play music on the road. Sell some tickets, record some records, and have the time to write songs. We’ve both been juggling jobs outside of music to be able to do our music when we can, and just keep up with living expenses and all that. So I think we’re both really looking forward to not having to work when we’re not on the road.”

by Susan Marquez

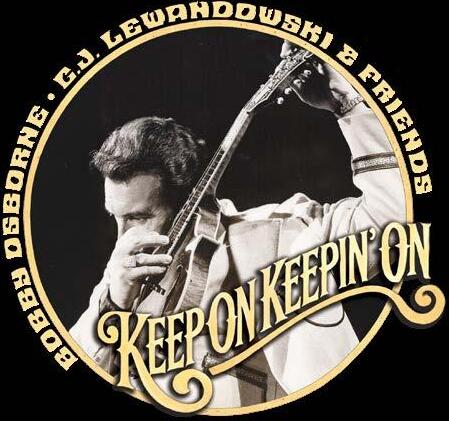

When C.J. Lewandowski was a teenager, he met one of his music idols, veteran bluegrass artist Bobby Osborne. “I got to pick with him, and I was forever hooked,” C.J. says.

C.J. worked hard to master the mandolin and was already playing gigs when he enrolled in the Kentucky School of Bluegrass and Traditional Music. “I went because Bobby was teaching there,” he says. “After a few months, Bobby asked me why I was there. I told him it was because he taught there and that I wanted to hang out with him. He told me that I didn’t need to enroll in college to do that, and that the best thing I could do was to get out on the road and play.”

When C.J. purchased his 1927 F-5 Fern mandolin, he contacted Bobby. “We compared mine to his 1925 model, and we took photos. That’s what spawned our friendship.”

C.J. began going to Bobby’s house once or twice a month, and the two developed a deep friendship. “Then COVID happened,” says C.J. “I didn’t want to risk bringing outside germs into his home.” During that time, Bobby went into a funk, depressed that he couldn’t play at the Grand Ole Opry or other shows. “He did some mandolin video lessons on YouTube,

Saturday, Feb. 7 Saturday, Feb. 7

1 - 7 p.m. | Ocala, FL 1 - 7 p.m. | Ocala, FL

To learn more and purchase tickets, scan the QR code or visit: ocalafl.gov/brickcitybluegrass

but it wasn’t the same as having a live audience. He missed the Opry so much.”

When COVID finally passed, C.J. was able to see Bobby again. “I talked to his son, Bobby Jr., at the 2022 IBMA awards, who agreed that I could book Bobby for a few shows.”

A trip to Palm Springs to visit Keith Barnacastle, founder of Turnberry Records, was the spark that ignited an idea C.J. had. “I told Keith I thought it would be cool to get Bobby into the studio. Keith asked if I thought he would do it. I had to get up the nerve to mention it to Bobby.” Bobby was intrigued when he heard a fellow from California was interested in recording him. “We let Bobby pick the studio and the songs.”

In January 2022, recording began at Ben’s Place, a studio in Nashville owned by Bill Surratt. “He engineered the project.” C.J. assembled a band for the project that included himself, Lincoln Hensley, and Bobby Osborne Jr. “It was important to surround Bobby with people he was comfortable with, and people who loved and admired him.” C.J. laughs, saying it wasn’t like ordinary Nashville sessions. “Bobby had the set list, and some days we would record three or four songs, then other days we didn’t do any, because Bobby just wanted to talk. We let him set the pace.”

One day, Bobby came in and said he wanted to do Rocky Top over again – he wasn’t pleased with his vocals. “None of us realized that would be his last time in the studio.” Bobby Osborne passed away on June 27, 2023. “I went to see him in the hospital before he died, and Bobby was talking about the artwork for the album cover. After we told each other, ‘I love you,’ I told Bobby on my way out to ‘keep on keeping on.’ He gave me a thumbs up and said, ‘YOU keep on keeping on.’ Those were his last words to me.”

After Bobby’s death, C.J. could barely manage to listen to recordings of Bobby’s voice. His passing hit C.J. hard. “I spoke at his funeral, and I was a pallbearer. When I got home, I called Keith and said I didn’t know what to do.” At the time, they had eight tracks with Bobby’s vocals and one instrumental Bobby played on.

C.J. says that since Bobby’s passing, he has had an intense way of showing up. “I was sitting on my porch, and in my mind, I heard him say, ‘I gave you something, now do what you want with it.’ I figured that the album wasn’t supposed to be with Bobby, but for him.” At the 2024 IBMA awards show, C.J. was asked to be a part of a tribute to Bobby Osborne. After his performance, he went backstage where Del McCoury, Ronnie McCoury, and the Boys were playing “She’s No Angel.” C.J. spoke with Bobby Jr., who suggested that Del be added as another voice on the album. “My idea had been to finish the album like it was, as an album of Bobby’s last recordings, but that opened up a whole new realm of possibility.”

C.J. called Billy Strings about adding vocals to the album. “Billy said he knew about the project and thought he had missed the boat on it.” Billy sang along with Bobby’s recording of “Cora is Gone.”

Bobby showed up again for C.J. in December. “I make an annual trip to Florida the first week of December, and at that time, I was seriously considering hanging up bluegrass and becoming a realtor. I was listening to Del’s Hand-Picked show on Sirius XM’s Bluegrass Junction. “It was a re-run, recorded before Bobby died, and Del talked a lot about Bobby.” Then came Chris Jones’ show, and he announced he would be celebrating Bobby Osborne on the show because it was Bobby’s birthday.

When C.J. returned home, a box awaited him from the Country Music Hall of Fame. Inside, there was a letter asking if he would like to be included in their upcoming “Unbroken Circle” exhibit, which features stars with their mentors. “They did an exhibit of me and Bobby. We had so many things planned, but this wasn’t one of them.”

Vince Gill was at the opening and asked if he could do “Lonesome Feeling” on the album. Other stars jumped on board, including Sam Bush, Mollie Tuttle, Wyatt Ellis, Jaylee Roberts, The Osborne Boys, and the Po’ Ramblin’ Boys. “Everything about this album happened naturally. It was not by design. And it took two years to make, but I had to get it done,” says C.J. “We had people who pre-ordered the album who were waiting for it to be released, and I had to do it for Bobby.” The album, Keep on Keepin’ On, was released on August 22.

“I’m blessed to have all his sons on the album. Getting to know the Osborne family and being close with them has been a great experience for me.”

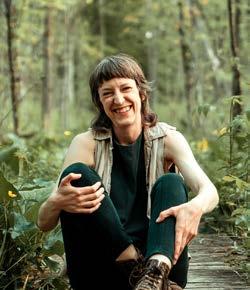

a Creative Fall

Fulfilling her lifelong ambition, Twin Cities singer-songwriter Clare Doyle enjoys the road alongside her friend and fellow Minneapolis music artist, Michael Gay.

“I’ve been focusing on touring,” shares the native Saint Paul, Minnesota songwriter. “We’re [playing] New Orleans, Birmingham, Nashville, St Louis, Kansas City and a couple of stops in Nebraska.”

Doyle was delighted to be among the star-studded performers at The Blue Ox Music Festival. “It’s just a really beautiful experience, and it was a lot of fun.” Sharing the stage with legends Sam Bush and Peter Rowan along with modern acts Molly Tuttle and Golden Highway was a performance highlight. “I was honored to be a part of the lineup.”

Launching her career in 2022, she was named one of First Avenue’s Best New Bands of 2023 and Emerging Artist of 2024 by Music in Minnesota.

Doyle, who has an EP and a handful of singles, says many people are unfamiliar with her

music. “It takes a lot of footwork to build a crowd. There are a few audiences now that know certain songs, but for the most part, we are playing to crowds who are hearing the songs for the first time,” explains Doyle, who is actively building her following.

Most of her fan base is in her hometown. “In Minneapolis, where I started, there is more name recognition,” adding, “Anywhere someone is based is going to be their biggest draw.” The Saint Paul native says she wants to revisit areas. “We are working on coming through the same towns a couple of times a year.”

“You just have to play where you can, “ Doyle explains when asked about different audiences. “We play in a lot of different types of rooms. We’ll be in a barbecue joint one night, a listening room the next, and a honkey tonk after that. You have to read the room and go with it.”

Doyle reveals that motels are not the only place to stay on the road.

“If we have friends who live in the [towns] we’re playing, we will crash at their house,” shares the singer.

As a former event coordinator, Doyle is familiar with the traveling lifestyle. “I wasn’t playing out until a few years ago, but prior to that, I was working on the road a lot with event productions.

Doyle admits that she needs more time to write songs. “I try to do a little bit of writing consistently. It’s been a busy summer, so I haven’t done as much as I’d like to. I’m going to slow down in the fall and focus more on writing.

“It’s tough spending so much time in the business side of [music] and have to flip your brain over and be creative.”

Doyle says new songs have to fit.

“As soon as I finish a song, I will try it out with the band, and if it’s a good fit, we will throw it into the set,” shares Doyle. “Half the set are… songs we haven’t recorded yet. It’s exciting to bring a new song to the band and hear it come to life!”

Although she released her EP Stranger in 2024, Doyle is not ready to record an album.

“We currently don’t have anything else recorded. It takes a [long time] to get a record together. I am looking at being able to do it at some point. My goal for the next record is to be really intentional about it. I want it to be cohesive.”

Doyle, whose struggle with self-doubt caused her to quit music in the past, feels that playing has been a huge help.

“It was definitely a stronger presence when I first started playing again,” Doyle recalls about her low self-esteem. “Playing music has been very healing. I had to confront that head-on. Playing has given me a reason to dismantle those beliefs.”

The Minneapolis native shares that the years spent away from music had an effect. “I felt like once I did start playing I had to make up for lost time.

“I want to take the next couple of months and slow down with shows. I’m hoping to focus more on writing and being creative as opposed to running a business.

“I hope what comes out of it is a deepening relationship with my songwriting—maybe even some good ideas for a record.”

“Christmas Time’s A-Comin’” says the granddaddy of Bluegrass holiday songs. And it seems to be a-comin’ sooner each year.

As I write this, the first carol hasn’t fa-lala-ed on the radio. But stores already have hauled out the holly, trimmed the trees, and tempted us with seasonal samples of fruitcake and candy.

That’s put me in the mood to track down stories behind a few of my favorite Bluegrass Christmas songs. I once thought some of the more familiar tunes could be traced back to frontier days, but many were created in the mid-20th century.

“Christmas Time’s A-Comin,’” originally recorded by Bill Monroe in 1951, was written by Benjamin “Tex” Logan, a Texas fiddler with a side gig at Bell Labs. That’s “Doctor Logan,” who earned his Ph.D. in electrical engineering from Columbia University and did research in digital audio. I’m relieved that his level of “day job” achievement isn’t a requirement to be a Yuletide tunesmith.

Another favorite Christmas song is “Beautiful Star of Bethlehem.” Surely the Wise Men were humming that one on their way to the manger! Nope, again it’s a 20th century creation—with a barn rather than a stable in its backstory.

Robert Fisher Boyce, a Middle Tennessee dairy farmer, was also a songwriter and shape-note singer. A house full of children wasn’t the best place to concentrate, so he headed to his barn to write “Beautiful Star” in 1938. The Stanley Brothers were the first to record what’s still one of the most popular Bluegrass carols.

The holiday season is a time for memories of home and family. Bluegrass Hall of Fame writer Paul Williams put a lot of those images into “Old Fashioned Christmas.” He told me that he’d just gotten out of the service in 1957 when Jimmy Martin invited him to spend Christmas with the Martin family in Sneedville, Tennessee.

After the holidays, on a snowy car ride to Detroit, Paul wrote what became his first song as a member of Jimmy Martin and the Sunny Mountain Boys. Joe Mullens and the Radio Ramblers released their own version in 2022, featuring Paul Williams doing the recitation.

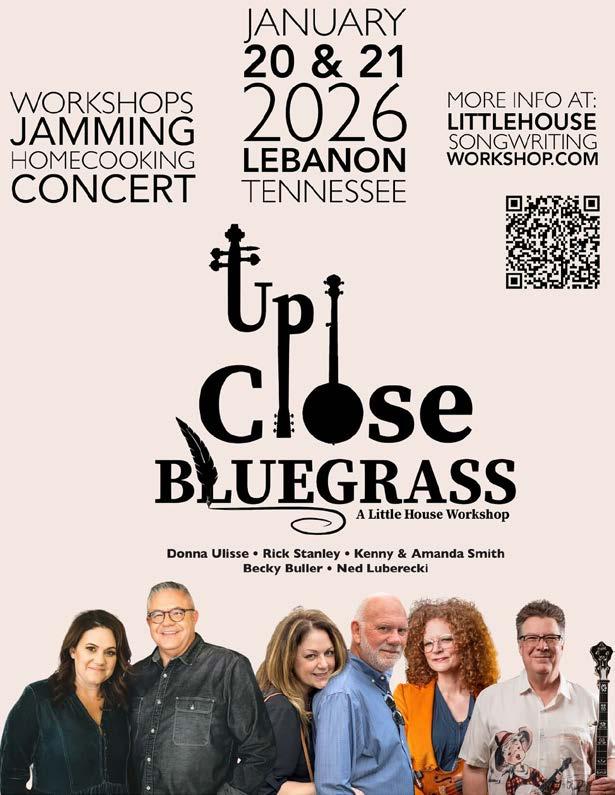

The Nativity naturally inspires memorable songs of the season. Donna Ulisse released “All The Way To Bethlehem” in 2012, a concept album that’s led to annual live performances across the country. She and husband Rick Stanley and other co-writers created each song from the viewpoint of a different character in the Christmas story. Donna says her favorite is probably the title cut, a conversation between Mary and Joseph that Donna wrote with Kerry and Lynn Chater. During the nine days of a brutal trip on the back of a donkey, Donna says, Mary’s faith never wavered that they’d make it “All The Way to Bethlehem.”What’s going on in songwriters’ lives can put a personal stamp on even the most familiar story. In a writing session with Sue C. Smith and Lee Black, Jerry Salley mentioned to his co-writers that his daughter was expecting her first child. The writers then focused on other parents who were preparing to welcome a newborn more than 2000 years ago. The song “Getting Ready for a Baby” was recorded by the Oak Ridge Boys in 2012 and by Bluegrass group Volume Five as well as Jerry Salley.

Some of the most moving Christmas tunes contrast happy holiday memories with wartime loneliness and hardship. That explains why “I’ll Be Home For Christmas,” recorded in 1943 by Bing Crosby, was the most requested song at USO shows in World War II. It remains a standard that’s been covered by many Bluegrass artists.

Bluegrass writers also have tapped into the theme of conflict in what’s meant to be the season of peace on earth. In Tony Trischka’s “Christmas Cheer (This Weary Year”), Civil War soldiers try to keep the spirit alive during a break in the fighting. There are games, better rations, and even a stocking gift for the drummer boy.

But soon, “a battle looms, the war resumes.” It’s a reminder that “Christmas cheer this weary year’s not like the last, you know. But hopefully by next we’ll be united with our families back home.”

Paula Breedlove and Mark “Brink” Brinkman look at the same war through civilian eyes in “Christmas in Savannah,” recorded by Dale Ann Bradley. At the end of Sherman’s March to the Sea in 1864, the Union General tells President Lincoln that he’s “presenting as a Christmas gift the City of Savannah.”

Understandably, starving local citizens weren’t in a festive mood. The siege had cut off supplies to the war-torn town until “Yankee Santas” from Michigan “came round with food and fresh provisions on wagons that were pulled . . . by little Christmas reindeer that looked a lot like mules.”At an IBMA song circle, I heard Dawn Kenney and David Morris sing their “Bells of Home,” which was recorded by the group Circa Blue. This new-to-me song is set “somewhere in Belgium” during World War II.On a snowy Christmas Eve during the Battle of the Bulge, a soldier dreams of holidays spent with family. Though he believes “some things are worth fighting for . . . like every soldier in this foxhole tonight, I miss the Bells of Home.”That song connects with me because it could have been the story of my father-in-law, Bill Scarbrough, who fought in that battle. Not long after, he was badly wounded and triaged with the dead. Then a passing medic noticed some slight movement and saved his life. I’d like to think that Tennessee farm boy soldier was called back by the Bells of Home.

by Stephen Pitalo

If you ask Matt Wallace why he made his new album Close The Door Lightly, his answer comes from years of making music on stages, in studios, and in the quiet moments between gigs—years that have shaped the Knoxville-born bassist into the kind of artist who knows exactly what he wants to play, and who he wants to play it with.

The album—out now on Huckleberry Records—isn’t a showcase of original material, and that’s by design. Wallace calls it more of a “jukebox record,” a collection of songs he loves, reimagined with some of his favorite players. “It’s less like you’re making a record and more like you’re filling a jukebox full of stuff that you want to hear,” he says. Those choices run the gamut from Osborne Brothers classics to Jimmy Martin staples, filtered through Wallace’s warm, grounded musical sensibility.

He brought in musicians he’s worked with over the past decade—Don Rigsby, Ronnie Stewart, Jeff Partin—and one newcomer to his circle, guitarist Brian Stephens, whose feel reminded Wallace of the late Tony Rice. “Brian is the closest feel to… anyone… to Tony that’s playing right now,” Wallace says. “We locked in within ten minutes.” The rhythm tracks were cut live with Stephens and Alex Hibbitts, and then Wallace sent songs out for the others to add their parts remotely. The result is an album polished but relaxed, steeped in East Tennessee bluegrass and tinged with country steel and drums in unexpected places.

The title track, “Close The Door Lightly When You Go,” first caught Wallace’s ear on a Dillards record. He loved Darrell

Webb’s version but wanted his own to sound different—with pedal steel, drums, and a more country feel. That mindset shaped the whole project: honor the source but make it yours. When it came to “Once More,” Wallace immediately wanted Rigsby’s Ralph Stanley-inspired tenor on it. “I cut it because I wanted to hear Don Rigsby sing ‘Once More,’” Wallace says.

That straightforward approach doesn’t mean the work was easy. Wallace still grins, recalling the moment Stewart started sending him banjo tracks while he was at his son’s high school baseball game. “I told him, ‘I want you to play everything mean as shit,’” Wallace laughs. “And he nailed it. I was sitting there, headphones in, grinning like an idiot.”

Wallace’s path to this album stretches back to 2005, when a college baseball injury left him searching for something to fill the time. His grandfather had been a local musician, and bluegrass pulled him in fast. His first professional gig was with Paul Williams, although Wallace admits he had no idea who Williams was when he cold-called him out of the phone book. From there, he logged years on the road with Williams, Audie Blaylock, and others, often while holding down a fulltime job.

Wallace plays far fewer shows these days, choosing to be home for his three sons’ travel baseball schedules. “I would much rather… be remembered as a good daddy who was always there than a bass player or a bluegrass musician,” he says. That shift in priorities shows in Close The Door Lightly. It’s not a young man’s calling card; it’s the

work of a musician making the record he wants, with the people he wants, at a moment when the music feels like it should.

While Wallace jokes that there’s “not a lot of art” to it, the album’s breezy confidence suggests otherwise. It’s the kind of work that comes from knowing your strengths, your limits, and your reasons for making music in the first place.

“Just listen to it,” he says. “I hope you enjoy it.”

by Candace Nelson

The Appalachian Mountains come alive each year with festivals that reflect the region’s deep cultural traditions and creative spirit. From music and storytelling to agriculture and harvest, these gatherings highlight what makes Appalachia one of the most distinctive cultural landscapes in the country. Here’s a guide to uniquely Appalachian festivals worth planning a trip around in 2026.

Spring: Big Ears Festival — Knoxville, Tennessee (March 26–29, 2026)

Spring in Appalachia begins with a celebration that has earned an international reputation while staying true to its mountain roots. The Big Ears Festival transforms downtown Knoxville into a citywide stage, filling historic theaters, churches and intimate clubs with sounds that range from traditional mountain ballads to avant-garde jazz and experimental compositions. What makes Big Ears uniquely Appalachian is the way it embraces innovation while honoring tradition, echoing the creativity that has long flourished in the mountains. For four days, Knoxville becomes a cultural crossroads, welcoming visitors from around the world while shining a spotlight on the region’s spirit of artistic exploration.

Summer: Nelsonville Music Festival — Nelsonville, Ohio (June 18–20, 2026)

As the Appalachian foothills turn lush and green, music lovers gather in Nelsonville, Ohio, for a festival that blends nationally known acts with the sounds of the mountains. The Nelsonville Music Festival, held at the Snow Fork Event Center, offers four stages surrounded by forests and open fields. Festivalgoers can camp under the stars, wander through artisan markets, and savor food from local vendors while discovering both established headliners and emerging Appalachian voices. With its balance of national reach and local authenticity, Nelsonville has become a summer tradition that captures the community spirit of Appalachia.

Late Summer: Appalachian Fair — Gray, Tennessee (August 24–29, 2026)

The Appalachian Fair in Gray has marked the end of summer for generations, offering a weeklong celebration of agriculture, music and heritage. Now more than a century old, the fair combines carnival rides and midway games with a strong emphasis on the traditions that define mountain life. Livestock competitions, agricultural exhibits and craft demonstrations connect visitors to the skills and practices that have shaped Appalachian communities. Each evening, music takes center stage, often featuring

bluegrass, gospel, and country performers whose songs echo the region’s stories. The Appalachian Fair is a reminder that these roots remain vital to life in the mountains today.

Fall: National Storytelling Festival — Jonesborough, Tennessee (October 2–4, 2026)

As the leaves turn and a chill enters the air, Appalachia turns its attention to the art of storytelling, a tradition deeply embedded in the culture of the mountains. The National Storytelling Festival in Jonesborough, Tennessee, is the pinnacle of this celebration. Since its founding in 1973, the festival has drawn thousands to Tennessee’s oldest town to gather under tents and listen to tales that range from folktales and ghost stories to personal narratives. Though the festival now attracts tellers from around the world, its Appalachian heart remains strong, honoring the voices and cadences that have echoed through the mountains for generations.

Fall: West Virginia Pumpkin Festival — Milton, West Virginia (October 2026)

Autumn in Appalachia would not be complete without a harvest festival, and the West Virginia Pumpkin Festival delivers with community pride and seasonal charm. Held in Milton, this event showcases giant pumpkins, vibrant displays, and contests, but what makes it distinctly Appalachian is its focus on local artisans, traditional crafts and bluegrass music. Families flock to the festival to enjoy homemade foods, watch craft demonstrations and celebrate the bounty of the season. For many, it has become an annual tradition that captures the warmth and beauty of fall in the Mountain State.

From the first notes of a fiddle in the foothills of Ohio to the towering pumpkins of West

Virginia, Appalachian festivals in 2026 offer more than entertainment. They provide a window into a culture that has been shaped by mountains, rivers and generations of artisans, musicians and storytellers. Each event captures a different facet of the region’s identity, whether it’s the experimental sounds and international artistry of Knoxville’s Big Ears Festival, the harmonious blend of local and national music at the Nelsonville Music Festival, the enduring agricultural traditions and bluegrass tunes of the Appalachian Fair, or the timeless art of oral storytelling in

Jonesborough. The West Virginia Pumpkin Festival adds yet another layer, celebrating harvest, craft and community spirit with a distinctly Appalachian flair.

Together, these gatherings offer travelers

and locals alike a chance to experience the heart of the mountains firsthand, to immerse themselves in traditions that continue to thrive and to connect with communities that welcome visitors with warmth and pride. Planning ahead ensures you can attend the events that resonate most, from the small-town charm of a pumpkin festival to the city-wide spectacle of Big Ears. In 2026, Appalachia is ready to share its music, stories, and heritage — each festival a living reminder of why this region’s culture remains vibrant, authentic and unforgettable.

by Jay Smith

When an artist releases eight all-original bluegrass albums in as many years, it’s fair to wonder if there’s anything left to say. Then along comes Hillbilly Irish, and Marty Falle answers that question with thunder. Released on September 15, 2025, the album didn’t just hit the ground running—it flew like “Old Crow” down the track. Within twenty-four hours, it climbed to #1 on the APD Global Top 50 Albums (All Genres), claiming its place as a modern bluegrass landmark.

From the very first notes of the title track, featuring Carly Greer, Hillbilly Irish stakes out its own musical territory— where the Celtic whistle meets the Kentucky banjo and a farmer’s sweat mingles with the salt of the Irish Sea. Falle’s lyrics spin a tale of love and lineage, “To Eastern Kentucky from the Irish Sea / Where the banjo and fiddle play and the crooked river winds.” It’s the story of two hearts—Shamus and Molly—but also of a people, a migration, a music that never forgot where it came from.

Critics across the bluegrass world have been quick to praise. Sandy Shortridge of Radio Bristol called it “a project that makes me want to pat my foot, dance a jig, reflect, and even shed a tear.” Jeff Lipchik from The Bluegrass Jamboree dubbed the duet “bluegrass at its finest—raw, real, and ready for the airwaves.”

Faith, and Fellowship

There’s a thread running through Falle’s work that ties farm life to faith and hardship to hope. Nowhere is that more apparent than in “Love Raised the Roof,” the album’s gospeltinged anthem to community resilience. When tragedy strikes and a family’s home burns to the ground, neighbors gather with hammers, saws, and grace—because, as Falle writes, “A house built with love will forever stand strong.”

The record’s emotional core deepens with “Miss West Virginia,” a haunting tribute to Mel Ann Pennington, a pageant queen lost too soon. Greer’s harmonies hover like a prayer, and Falle sings with the quiet reverence of a man who’s seen both beauty and heartbreak in the same breath.

Then comes the firebrand—“Eminent Blood,” a righteous protest song born of reallife injustice. Falle, whose own Kentucky farm was scarred by a power company’s eminent-domain intrusion, channels that fury into verses that could hang beside Woody Guthrie’s protest banners. “They bought my blood in the name of eminent domain,” he cries—a line as much prophecy as protest.

Still, Hillbilly Irish isn’t all solemn testimony. Falle’s “Kitchen Jamboree” swings like a lantern-lit gospel barn dance—fiddles on fire, spoons clattering, and Mamaw shouting hallelujah between verses. “The Lord don’t mind if you stomp off-key,” he sings, celebrating the kitchen as the cathedral of Appalachian joy.

• “Hobo” captures the wistful ghost of the American drifter.

• “Old Crow” gallops through Kentucky’s racing past with thunderous energy.

• “I Broke Bread with the Devil” and “The Beatitudes of Bubba Ray” dive into the darker corners of rural life, where sin and scripture often share the same pew.

Together they paint a living portrait of Appalachia—part myth, part memoir, all music.

The stats tell the story. Within weeks of release, Hillbilly Irish impacted radio charts:

• #1 APD Global Top Bluegrass/Folk Albums for September 2025.

• #2 APD Global All Genres album overall.

• #3 Roots Global Top Bluegrass Albums by early November, with 12 songs in the Top 40.

• The single “Hillbilly Irish” hit #2 on I-Heart Radio’s Rick Dollar Show, while “Love Raised the Roof” and “Hobo” both broke into the Roots Top 10 Songs.

Across North America and Europe, interviews and features have followed— from Ontario’s Sunday Grass with Debbie Howson to France’s WRCF Radio’s November spotlight. The momentum hasn’t slowed.

Other highlights prove just how wide Falle’s storytelling range can stretch:

Recorded in Nashville’s County Q Studios with producer Jonathan Yudkin, Falle’s band is a who’s who of modern bluegrass mastery: Carl Miner (guitar), Mike Bub (bass), Matt Menefee (banjo), Josh Metheny and Rob Ickes (dobro), Jim Hoke (harmonica, pennywhistle, accordion, flute), and background singers Carly Greer, Ashley Lewis, and Kim Parent. The production is crisp yet human—each note breathes, each harmony feels like it was sung with eyes closed and hearts open.

Even the cover art tells a story. Created by Disney artist Tom Matousek from a photo by Amber Falle, it ties the record’s Irish-Appalachian theme into a single visual heartbeat— one part myth, one part memory.

As Walter and Willa Volz of Bluegrass Breakdown put it, “No covers or remakes, just great story songs with a twist of Irish. Also, no filler.” They’re right. Hillbilly Irish isn’t just another collection of tunes—it’s a fully realized statement from an artist at the height of his storytelling power.

Marty Falle’s music continues to do what true bluegrass should: honor the past, embrace the present, and carve a path toward something eternal. With Hillbilly Irish, he’s bridged the Atlantic and the Appalachians, proving that faith, family, and fiddle can still raise the roof—one barn, one song, one story at a time.