Within these pages lies bloom issue 3 May 2025 Theme: Woman as a Creative Entity. By the Feminist Equal Rights Alliance (FERA). Please handle with care

EDITOR-IN-CHIEF

Camila Lee

ASSOCIATE EDITORS

Deb Zhang

Hibbah Ayubi

Sarah Stanford

Tiana Wang

DESIGN

Camila Lee

Deb Zhang

Tiana Wang

CONTRIBUTING AUTHORS

Aditi Malhotra

Grace Goudie

Jessica Taylor

Katrina Sze Ching Soong

Rayn Lakhani

Bloom is the University of Toronto’s Feminist Equal Rights Alliance’s annual publication It centers around a chosen feminist theme and collects work from women and gender non-conforming people of all identities to share with our academic community as well as other likeminded individuals

The first issue of Bloom was published during the second spring of the coronavirus pandemic The name Bloom was chosen to symbolize birth and renewal, feelings that echoed the broader mood of revival and restoration at the time The second issue of Bloom took the name to mean even more: flowers, varying in color and type, came to represent everything from death to friendship to joy In doing so, the publication embraced its ever-changing nature Following the organic quality ascribed to its name, the third and current issue of Bloom draws on the metaphor once more. Much like flowers, admired for their aesthetic qualities while also carrying deep emotional weight, women and gender non-conforming people should be free to flourish creatively, beyond the boundaries so often imposed on their expression.

Dear Readers,

This year’s theme came to me slowly, unexpectedly, most notably after I read my first Annie Ernaux in the summer of ‘24 Her writing struck me as raw, naked, unlike anything I had read before How is she capable of such vulnerability? I could never dream of such an overt display of the self Thoughts I can barely admit to myself, that pain me to put on paper, Ernaux shares with the world, or perhaps first with herself, and the world simply happens to bear witness Lucky for us

In her article for The New York Times, Rachel Cusk another writer I deeply admire recounts the ambivalent, at times even hostile, public reaction to Ernaux’s Nobel Prize for Literature in 2022 That a woman who wrote solely about herself should be awarded so prestigious an award was a concept that stirred much discomfort Countless explanations followed: that a French readership considered the unfiltered depiction of female oppression “distasteful”; that her reflections on femininity were trivial, could not be regarded as serious literature; that the literary patriarchs turned green with envy at her success Yet Cusk dismisses these excuses, suggesting instead that the backlash was proof Ernaux had touched on a truth too hard to swallow “If it remains difficult for women to make art about themselves, it is because femininity still has no place in culture,” Cusk writes

With this conversation in mind, I introduce Bloom’s third issue: Woman as a Creative Entity. What are women allowed to write about? Why are conversations about sentimentality, aesthetic experience, and pleasure so often dismissed as superficial or lacking in value? The pieces featured in this issue center around gendered limitations manifested in the creative world, delving into how these constraints shape and confine feminine expression, both in terms of its production and reception. Ranging from poetry to academic essays to research papers, our contributors offer varied interpretations of the theme: intimate reflections on the boundaries of feminine expression, critical analyses of popular media, and histories of women transcending creative limits. Notably, our contributors also explore intersections with race and colonialism, highlighting how multifaceted identities influence women’s creative agency.

Finally, this letter would be incomplete without acknowledging the passion and sustained effort of our authors and editorial board, along with the invaluable support of the FERA exeutive team. To begin, thank you to our contributing authors, Aditi Malhotra, Grace Goudie, Jessica Taylor, Katrina Sze Ching Soong, and Rayn Lakhani, whose distinct voices have shaped this issue in meaningful ways. To our editorial board Deb Zhang, Hibbah Ayubi, Sarah Stanford, and Tiana Wang thank you for your care, precision, and unwavering dedication throughout the editing process. I am especially grateful to Deb and Tiana, whose help with graphic design and layout was indispensable. In addition, I am beyond thankful to our FERA Co-Directors, Simran Grewal and Yiming Ma, whose support and encouragement made this issue possible. Finally, thank you to Sarah Padwal, who helped me give a name to the theme when it was still an abstract concept and words flew out of my mouth before I had even begun to make sense of them.

It is my sincere wish that readers find something in this issue that provokes reflection and strips writers of shame in the same way Ernaux’s work did for me. Although for now I am only borrowing an ounce of her candor, I hope readers find value in the attempt.

Sincerely,

Camila Lee Editor-in-Chief, 2024–2025

Colonial Question in Bridgerton

Within the Patriarchal Sublime

Katrina Sze Ching Soong

in response to sylvia plath's famous fig tree analogy

Grace Goudie

this is an act of voyeurism

Grace Goudie

i pass you this crown of roses

Rayn Lakhani

The Regency drama based on Julia Quinn’s works that took the world by storm, Bridgerton, has been a trailblazer in more ways than one since its initial release in December 2020 An escapist fantasy with emotionally rich characters, complicated plot lines, and intricate sets, the show is the first of its kind to make race a mere quality of its characters The show’s producer, Chris Van Dusen, claimed to follow a method of color-conscious casting in order to create a Regency era that reflects modern society (Nguyen) The highly anticipated second season, which starred Indian actresses Charithra Chandran and Simone Ashley in lead roles portraying Indian characters, came with a slew of antithetical reactions

by Aditi Malhotra

Along with delight over the overdue representation of Indians and the Brown community at large in mainstream media, came palpable disappointment over the clear lack of care that went into conceiving the show’s Indian characters, who played primary roles in the plotline While Bridgerton gives viewers an idealistic, romantic world that reconciles racial differences and offers representation to severely underrepresented groups attempting its utmost to show a historical world that places various racial communities on an equal platform it also entirely disregards the very real colonial histories of these communities and treats it superficially, a fact poorly received by its audience

Throughout the second season, the obtrusive inadequacy in addressing the complicated and oppressive political relationship that once existed between the British Empire and India casts a shadow over every viewer’s experience While the season’s representation of the Brown community was widely marketed and impatiently awaited, many viewers were left disappointed by the way the show simply painted over a very charged colonial past (Wynne) Although the show was pioneering with Brown representation, it also contributed to a deeprooted and harmful trend of colonial agnosia and the modern processes of collective omission of the actual, lived experiences of several communities and

people (Vimalassery, et al 1) It is imperative to recognize the fact that colonial ruins exist far beyond physical sites and corporeal traces, and the lack of criticism and acknowledgment that prevails throughout the show causes far more damage than one might initially perceive (Stoler 5)

The first season of the show, which centres on the love between Daphne a white, erudite, flawless debutante and Simon a Black, handsome, rakish duke still provides some vague explanation for its depiction of Black people as nobility, including a Black queen and several other interracial marriages, in a time when people belonging to different racial groups were considered anything but equal in the real world The second season, however, is grievously lacking in this aspect, and simply chooses to gloss over England’s colonial past when it comes to India The eight episodes ambiguously hint at race and class without ever truly addressing it, providing a refreshing new world that erases the real one for those who are not aware of the specific modalities and nuances of colonialism; a world that is alarmingly uncomfortable for those belonging to previously colonized communities

Not only is the colonial past of the native land of three of the season’s protagonists not addressed, but the actual cultural practices, geographical locations, and linguistic mannerisms are thoughtlessly employed with little to no research While Kate and Edwina Sharma, two of the Indian protagonists, have rich emotional backstories and complicated personalities, their Indian identity is sorely under-researched and carelessly put together The show provides a painfully homogenous rendition of what it means to be Indian, with multiple cultural inaccuracies, inconsistencies, and botched pronunciations of Hindi words (Wynne)

The Sharma sisters seem to hail from Bombay, a city in West India that has an Anglicized name which solely exists as a

colonial artifact, having been renamed to Mumbai after India gained independence However, they call their mother and father ‘amma’ and ‘appa,’ respectively, names that originate from South India, and are seen using the endearment ‘bon’ a word that comes from Bengal, in East India This is particularly damaging as the show fails to take on a nuanced approach to the myriad cultures and languages that exist in India and condense them into a single dimension

As endearing as it is to see minorities represented in entertainment media as someone belonging to a cultural and racial minority myself, it is imperative to ask how relevant this representation is when the lived

“ULTIMATELY, IF POWER IS AT THE CENTER OF LOVE AND MARRIAGE ... THEN THE SHOW’S DREAM-LIKE WORLD IS BORN FROM A CONFUSING MIX OF HISTORY.”

experiences, traumas, and histories of entire communities are distorted There is a difference between simply showing minorities on screen and representing those same minorities There are also several ways to depict a fantastical, refreshing world while still acknowledging and respecting the histories experienced by countless people, experiences that continue to impact lives to this day.

Ultimately, if power is at the center of love and marriage, as is argued in the second season of Bridgerton, then the show’s dreamlike world is born from a confusing mix of history The qualities that make a refreshing and romantic alternate world also make it

difficult to understand who has the power

While the show leaves something to be desired not only in addressing the colonial past of a community it very proudly claimed would be well represented but also in coming to a proper compromise it does form characters and personas that counter multiple stereotypes that prevail in modern society and gives agency to characters that are otherwise portrayed to have no influence or power In this manner, Bridgerton creates a way of escapism but is still respectful of the realities that are associated with the groups of people they aim to include

Historically, it is true that most representation either speaks over subaltern women women belonging to marginalized and racialized communities or speaks contrary to what they are, Bridgerton, especially in its second season, manages to place otherwise routinely oppressed women in a position of power Characters like those of Kate, Edwina, and Lady Danbury fit Western points of view and operate to serve Western institutions in that they are constantly required to fit a particular mold of perfection in society as women, and are meant and raised to serve a defined role in their life However, they carry a lot of agency and have traits of boldness and strength that are not usually seen in characters such as theirs, disproving and belying Spivak’s belief that the subaltern cannot speak (Spivak 104)

Traditionally, throughout academia and general mainstream media, colonized groups are presented as covertly trapped in a Western perception (Georgis 60), reduced to an almost single dimension of personality and existence that usually serves to fuel the story from the sidelines. This is evident in the character of Genevieve Delacroixe, a woman of color who was intricately intertwined with many protagonists of the show throughout both seasons of the show, and yet barely ever played a role beyond the capacity of a revered and talented modiste

During French colonial rule in Algeria, the French authorities sought to assimilate the Algerian population by implementing Westernization policies, mainly targeting Islamic practices such as wearing the veil (Boussoualim, 2021, p. 1291). The veil, seen by the French as a symbol of patriarchy and "backwardness," became a focal point in their efforts to "liberate" Muslim women, with both French officials and feminist voices describing it as an oppressive tool of Islamic patriarchy (Preggo, 2015, p 350) Despite French attempts to suppress it, many Algerian women continued to wear the veil This raises a critical question: How

by Jessica Taylor

did French colonialism, alongside Western feminist narratives, shape the subjectification of Algerian women through the veil? Moreover, how did the veil become a site for negotiating power, identity, and autonomy under colonial rule?

Rather than portraying Algerian women simply as passive victims of colonial oppression or patriarchal control, this paper argues that the veil, despite its symbolic representation of repression, functions as a complex site of subjectification The veil became a tool that women, constrained by both colonial and Islamic frameworks, used

to navigate and reshape their own identities First, I will briefly discuss the historical context of the French colonization of Algeria, its propaganda tactics, and its effects on Algerian women I will then discuss the Western Feminist and French discourse at the time and how they contributed to the narrative already espoused by the French colonists Finally, I will explore the role of the veil in resistance during the Algerian War of Independence, using theoretical frameworks from Michel Foucault, Judith Butler, and Saba Mahmood to better understand how the veil functioned as both a symbol of oppression

and a site of resistance

Historical Overview of French Colonization in Algeria

Algeria's history is a rich tapestry of Islamic tradition, foreign invasion, and colonization Islam was introduced to Algeria between 8 CE and 11 CE The Muslim Turks (Ottoman Empire) invaded Algeria during the 16th century (Meredith, 2016, p 213) In the 19th century, expanding European powers colonized most of Africa Algeria, a North African country, was under French colonial rule from 1830 to 1962. During this period, the French government implemented policies aimed at Westernizing the local population, which was predominantly Muslim This included efforts to suppress Islamic practices that the French perceived as 'backward '

The French government assigned Algerian Muslims and other non-French Algerians inferior status Muslims were treated "as French subjects, with limited rights and bound by different sets of laws, rules, and regulations" (Meredith, 2016, p 213) Moreover, to gain fundamental rights, Muslims had to accept the French legal code, "including laws affecting marriage and inheritance," and reject the validity of Muslim religious courts (Meredith, 2016, p 213) In effect, Muslims had to reject fundamental aspects of Islam to gain basic rights Organizations such as Algeria's National Liberation Front (FLN) fought the French throughout the 20th century, and Algeria finally achieved independence in 1962

The Western Feminist and French discourse Through their "emancipation" effort and propaganda, the French colonists used two strategies to change how Muslim women and consequently the French were perceived by the world The first involved crafting portrayals of Muslim women by staging events, fabricating images, and producing texts that created a false reality (Perego, 2015, p 357) These manipulated representations were then disseminated

through French and international media channels The second tactic was to change Muslim women's physical appearance by convincing them to give up traditional clothing, especially the veil (Perego, 2015, p 357) Military photographers captured images of unveiled women or those presented as adopting French cultural norms, creating another form of constructed reality this time through subtle coercion rather than outright fabrication (Perego, 2015, p 357) French propagandists portrayed Algerian Muslim women as victims of their own culture, imprisoned in

“FRENCH PROPAGANDISTS PORTRAYED ALGERIAN MUSLIM WOMEN AS VICTIMS OF THEIR OWN CULTURE, IMPRISONED IN THEIR HOUSES ... AND TRAPPED BEHIND VEILS”

their houses, which were compared to jails, and trapped behind veils (Perego, 2015, p 357) This narrative suggested these constraints were brutally enforced by Algerian men, which served to further the notion that women were oppressed and in need of freedom This representation upheld France's cultural supremacy and defended French colonial endeavours as a moral quest to "free" these women (Perego, 2015, p 357) These tactics were designed to demonstrate to outsiders that French culture was liberating Muslim women and demonstrating France's accomplishment of its "modernizing mission "

These narratives by the French colonists were also propagated by French feminists, including Simone de Beauvoir and Juliette Minces The difficulties Algerian women experienced, including poverty, illiteracy, and legal inequality, were framed by French feminists as the result of the colonial government's reluctance to adequately execute French law, oftentimes echoing colonial rhetoric (Kimble, 2006, p 110) Influenced by imperialist ideologies, these feminists advocated for the continuation of colonial rule, believing it to be the most effective way to extend individual rights to Algerians They promoted "modernization" along French lines, emphasizing reforms in areas like citizenship, education, secularism, and gender equality as solutions to these issues (Kimble, 2006, p 110) These feminists reacted strongly to the issue of veiling and the status of women in Algeria, but their responses neither clarified the lived realities of Algerian women nor resolved the biases Instead, their exaggerated claims of victimization obscured the complexities of women's actual experiences, both in the past and present (Boussoualim, 2021, p 1301) Feminists such as Simone de Beauvoir and Juliette Minces linked the veil to religious oppression, with de Beauvoir famously describing the veiled Muslim woman as a form of "slave" (Boussoualim, 2021, p 1295) Minces, in turn, equated veiling with female genital operations, calling them both "symbols of women's oppression" (Boussoualim, 2021, p 1295)

Minces's portrayal of veiling practices was flawed, particularly in Algeria, where she inaccurately described the veil worn in certain eastern regions as a black cloak covering the entire body except for one eye (Boussoualim, 2021, p 1295) This misunderstanding stemmed from her inability to recognize the diversity of veiling styles across regions, each adapted to local climates, cultural practices, and historical contexts Minces's bias led her to simplify Algerian women's experiences, presenting them as passive victims rather than

acknowledging their varied cultural expressions and autonomy Overall, for these feminists, the veil served as a tool of religious oppression against women and proof of the inferiority of Muslim culture

Clothing, Identity, and the Public-Private Divide

Clothing is a form of self-expression, and the line between public and private spaces is reinforced through veiling practices The idea of freedom in clothing is not universal clothing practices are shaped by societal norms tied to class, gender, ethnicity, race, and religion, influencing how women are perceived and defined within their communities and by external forces, such as colonial authorities. In Islamic contexts, veiling practices both reflect and reinforce these private and public divisions, inscribing gender spatial norms onto women's bodies (Fathzadeh 2021, p 156) By covering specific body parts while exposing others, the veil demarcates public and private spheres, creating a visual representation of Islamic values in public spaces while regulating women's behaviour in private settings (Fathzadeh, 2021, p 156) However, Muslim women have adapted the veil as a tool for self-formation and creative expression, destabilizing binaries such as secular/oppressed For instance, during the French colonial rule in Algeria, women wearing the veil were simultaneously resisting French attempts at cultural assimilation and adhering to Islamic values that defined their public and private roles While the French authorities sought to frame the veil as a symbol of oppression, many Algerian women adopted it as a means of cultural resistance and defiance against colonial domination Yet the politicized nature of the veil continues to subject women both those who wear it and those who do not to cultural expectations tied to their perceived religiosity and "good Muslim" identity (Fathzadeh, 2021, p 157) Thus, the veil functions as a site of negotiation, where women navigate competing frameworks of cultural, religious,

and political authority, embodying both subversion and conformity within colonial discourses.

The Politicization of the Veil: Negotiating Identity and Resistance

The politicization of clothing practices, particularly the veil, underscores how women's bodies became sites of cultural negotiation As discussed earlier, French colonial authorities sought to liberate Algerian women by framing the veil as oppressive, while French feminists reiterated similar discourses. This led to Algerian women reclaiming it as a symbol of defiance However, these binary interpretations simplify the complex realities of veiling practices in colonial Algeria. Rather than solely oppressive or liberatory, the veil functioned as a site of subject formation, and women actively engaged with competing discourses Using the writings of Foucault, Butler, and Mahmood, it is vital to go beyond binary thinking and investigate how women's subjectivities were shaped by the interaction of power, culture, and religion to comprehend these dynamics

Theoretical frameworks

Foucault's concept of ethics and freedom illuminates how Algerian women navigated colonial and patriarchal restrictions during French rule According to Foucault, ethics and freedom are active processes, as ethics involves the ongoing physical practices, desires, and actions individuals engage in to care for themselves, and freedom is achieved by acting ethically toward others and the world (Fathzadeh, 2021, p 160) In this view, freedom is not a final state where all restrictions are removed but is instead expressed through continuous acts of selfcreation and self-formation shaped by specific historical contexts (Fathzadeh, 2021, p 160) In the case of Algerian women, the veil became a site of such practices, where they engaged in self-formation within the constraints imposed by colonial and patriarchal structures Freedom for these women was not about escaping oppression,

but resisting forces that sought to erase their identities and religion, asserting their agency through continuous negotiation. Even under extreme societal restrictions, they found creative ways to express their desires, challenging the notion that liberation is only about removing external barriers Their resistance particularly during the War of Independence was a persistent struggle against power structures that were not simply imposed but deeply ingrained in daily practices of self-discipline, cultural norms, and social expectations Therefore, resistance to societal norms is not about liberating the 'free' subject from external forces, but is instead an ongoing struggle to preserve one's freedom against power structures that are not only imposed externally but also manifest in everyday practices of self-discipline and selfsubjugation (Fathzadeh, 2021, p 160)

“MUSLIM WOMEN HAVE ADAPTED THE VEIL AS A TOOL FOR SELFFORMATION AND CREATIVE EXPRESSION, DESTABILIZING BINARIES SUCH AS SECULAR/ OPPRESSED”

For Michel Foucault, power is not localized within a government, a group, or an individual Nor is it something that is taken away or withheld from others, such as colonized peoples Power, he explains, "is not an institution and not a structure, neither is it a certain strength we are endowed with; it is the name one attributes to a complex strategic situation in a particular society" (Foucault, 1990, p 93)

Accordingly, simply presenting French efforts to prohibit Muslim women from wearing the veil as an institution taking power from another group is denying the relational nature of power, a process more sophisticated than simply denying or repressing Foucault's (1990) insight is valuable as it provides a new way to see that power is not just about repression or law but about "a certain form of knowledge" manifested through the various "mechanisms, tactics, and devices" that power employs (p 93) He describes this form of knowledge as "epistemes," general fields of knowledge that provide discursive parameters Epistemes are "what ultimately determines what can be said and what cannot be said" in a particular historical context (Kearney, 1994, p 286)

What Foucault refers to as 'dividing practices,' which separate subjects from others, are essential to these discourses In his various works, he points to discourses that divide subjects as sane or insane, normal or deviant In the context of French Algeria, Muslim women, for example, were "repressed" as distinguished from "free," and Islamic beliefs and practices were "backward" as opposed to "liberal," "enlightened," or "modernized " We should not approach these discourses regarding Muslim women and the veil as located and originating from entities such as governments, groups, or individuals, such as French feminists Simone de Beauvoir or Juliette Minces These epistemes do not arise from autonomous subjects but pre-exist and form these subjects In other words, subjects such as French government officials or feminists like de Beauvoir are not expressing ideas that originate from themselves Instead, they manifest discourses from epistemes that predate and form their subjectivities As a result, the focus should be narrowed to explore epistemic discourses surrounding Muslim women Muslim women were not simply compliant receptacles whose subjectivities were formed by Western liberal discourses or French feminists, nor were they autonomous

subjects who rationally rejected French oppression For Foucault, resistance is more sophisticated and complex. Describing resistance as a conscious and logical response to an oppressive institution contradicts "the strictly relational character of power relationships" (Foucault, 1990, p 95) As he explains, no one is "outside power," so resistance is never outside the relations of power (Foucault, 1990, p 95) Muslim women did not step outside the power relationship by continuing to wear the veil

The Veil as a Site of Subject Formation: Foucault, Butler, and Mahmood in Colonial Algeria

Like French officials and feminist speakers, understanding Muslim women during French colonial rule requires situating their subject formation within the specific socialhistorical context Foucault's concept of epistemes offers a helpful framework for examining these parameters The intersection of colonial domination, Islamic traditions, and local cultural norms shaped Muslim women's subjectivities In contrast, Simone de Beauvoir's ideas emerged within the intellectual currents of Western existentialism These differing contexts demonstrate how subject formation is historically and culturally specific Importantly, these parameters are not static but limit individuals' potential actions within their historical moment As Mahmood (2004) discusses, Butler's foreclosure concept emphasizes the exclusions integral to subject formation Butler identifies a "constitutive outside" everything unspeakable or unintelligible to the subject yet essential for its self-formation (p 19) These exclusions create boundaries within which subjects define themselves For Muslim women in French Algeria, the veil became a focal point of these boundaries Positioned at the intersection of power and resistance, it symbolized the colonial project of Westernization and a site of cultural defiance While French authorities framed the veil as oppressive, many Muslim women transformed it into a tool of resistance,

asserting their identities within the constraints of colonial and Islamic frameworks. This dynamic reflects Butler's insight that foreclosures are not permanent; norms are constantly reproduced through reenactment, leaving them open to transformation (Mahmood, 2004, p 19) Algerian women's practices around the veil exemplify this, as they redefined its meanings, challenging both colonial and patriarchal narratives Thus, the veil became a medium through which women actively reshaped their subjectivities, as seen in the Algerian War of Independence.

The Veil as a Symbol of Resistance and Subject Formation During the Algerian War of Independence

During the French colonial presence in Algeria, particularly the Algerian War of Independence, the meanings of the veil and the subject formation of Muslim women underwent significant modifications Different cultures inscribe different sets of norms and regulations on dress, which are produced through power relations (Fathzadeh, 2021, p 156) There were disparities between French and Algerian Muslim interpretations of the veil. These "norms and regulations on dress" were modified through these power relations, particularly at various resistance points As will be discussed, the veil's prohibition was actively resisted in diverse ways, shaping both its meaning and the subject formation of the Muslim women who continued to wear it

The armed battle by Algerian women during the war of 1954-62 is a significant period because it marks the beginning of women making their presence felt, showcasing how Algerian women deviated from the narratives forced upon them. By the end of the revolution, 10,949 women had participated in various capacities, including 3 1% in active combat (Amrane-Minne, 1999, p 62) Among them were the fida'iyat, 2,388 women who were crucial in smuggling weapons, money, messages, and assisting the revolutionaries, particularly in urban centres

(Salhi, 2009, p 115) Under their veils, they concealed explosives, identity cards, and weapons, infiltrating European quarters to plant bombs during the Battle of Algiers

This strategic use of the veil reveals how women actively subverted colonial norms and expectations, positioning the veil not as a symbol of passive submission but as a form of camouflage and resistance Far from being compliant victims of patriarchy or colonialism, these women were central figures in reshaping their identities and navigating both colonial and patriarchal power structures.

The veil, long associated with confinement and oppression, became a tool of subversion in the hands of revolutionary women. As Frantz Fanon observes, an unveiled Algerian woman, armed and infiltrating European spaces, could pass unnoticed by French military patrols, who complimented her appearance while ignoring the weapons concealed under her briefcase (Salhi, 2009, p 115). This highlights how the revolution empowered women to challenge colonial authority and traditional gender norms, boosting their confidence and allowing them to perform new roles in the public sphere. Women's participation in the war, particularly in urban areas, thus challenged the colonial image of Algerian women as obedient and restricted to the private sphere

The shift from the private to the public sphere was not only a response to colonial occupation but also to the restrictive gender roles within Algerian society Joining the revolution allowed women to reject the domestic roles prescribed by patriarchy, enabling them to become active agents in the national struggle (Salhi, 2010, p 115) This was a profound rebellion against colonialism and the societal norms that confined women to the home as caretakers and nurturers As the FLN recognized, women's participation in the revolution was essential to their struggle for national liberation Their active roles in carrying weapons, smuggling explosives, and providing medical care to wounded fighters marked a transformative

moment, not just for women but for the national movement as a whole

However, the role of women in the revolution was met with ambivalence by conservative factions within Algerian society While their contributions to the war effort were acknowledged, there was a persistent belief that women’s ultimate place was in the home once the war ended, reinforcing the tension between their revolutionary roles and the expectation to return to traditional feminine identities as mothers, daughters, and wives (Salhi, 2010, p 117) Slowly, women's positions shifted from active participants to compliant silent victims (Salhi, 2010, p 117) This tension underscores the complexity of women's subjectification during the revolution On the one hand, they were celebrated as national heroes Yet, on the other hand, their roles were often framed by conservative factions and post-war societal narratives as temporary and linked to the exigencies of war.

The veil, in the context of the Algerian War of Independence, symbolizes a duality: it is both a marker of women's oppression and a tool of their resistance Algerian women actively engaged with and reshaped the meaning of the veil, using it to navigate colonial surveillance, subvert patriarchal norms and assert their roles as active participants in the national liberation struggle Their contributions not only altered the gendered power dynamics of both colonial and Algerian society but also transformed the veil from a symbol of subjugation to a marker of resistance and agency

The veil in French colonial Algeria became more than a symbol of oppression or conformity to Islamic patriarchy: it evolved into a complex site of negotiation and resistance While French authorities and Western feminists sought to portray the veil as a tool of subjugation, Algerian women subverted these narratives by using the veil

to assert their autonomy and resist both colonial and patriarchal control Drawing on the works of Foucault, Butler, and Mahmood, this paper highlights how the veil, rather than being a mere passive symbol, functioned as a medium through which women navigated the intersection of power, culture, and religion During the Algerian War of Independence, the veil became a key instrument in the resistance, allowing women to challenge colonial authority while redefining their subjectivities Ultimately, the veil in this context exemplifies how subjectification and resistance are not simply about defying oppression but about reworking the meanings and uses of power within specific historical and cultural contexts.

Amrane-Minne, D D , & Abu-Haidar, F (1999). Women and Politics in Algeria from the War of Independence to Our Day Research in African Literatures, 30(3), 62–77

http://www jstor org/stable/3821017

Boussoualim, M (2021, February 17) Veiling between denigration and glorification in Algeria - sexuality & culture Sexuality and Culture

https://link springer com/article/10 1007/s121 19-021-09825-w

Fathzadeh, F (2021) The veil: an embodied ethical practice in Iran Journal of Gender Studies, 30(2), 150–164 https://doi org/10 1080/09589236 2020 18631 94

Foucault, Michel The History of Sexuality, Volume 1: An Introduction New York: Vintage Books, 1990

It is without a doubt that the sublime plays a huge role in Ann Radcliffe’s novel The Mysteries of Udolpho The sublime was an important aesthetic concept closely linked to the Romantic period and was thought, by Edmund Burke, to be a quality in nature which inspires high emotions such as awe, reverence, terror and overwhelm Elements of the sublime can be found as early as the first page of the novel when the narrator describes the view of Gascony as “bounded by the majestic Pyrenees” and “exhibiting “awful forms” (Radcliffe 1) However, while Edmund Burke largely attributes the sublime to nature, the terrifying quality of the sublime found in nature in The Mysteries of Udolpho is often mediated by elements of the pastoral. Instead, in The Mysteries of

by Katrina Sze Ching Soong

Udolpho, the terrifying and overwhelming qualities of the sublime in nature are most commonly associated with patriarchal power

The Mysteries of Udolpho is a gothic novel from the Romantic period that follows Emily’s misadventures, such as the death of her parents and being trapped in the supernatural gloomy castle of Udolpho under the control of her new patriarchal guardian, Signor Montoni Emily experiences most of her sublime experiences in the castle of Udolpho The castle, being a patriarchal object, fills the women in it with terror and deprives them of their reason, paralleling Burke’s description of the sublime: “The mind is so entirely filled with

its object, that it cannot entertain any other, nor by consequence reason on that object which employs it” (366) As such, by placing Emily within the patriarchal sublime, Radcliffe shows how the patriarchy intrudes upon women’s creative, imaginative space that they attempt to create for themselves.

The castle of Udolpho is undoubtedly, since the moment it is introduced, a patriarchal object. This is most evident by the fact that the castle is closely associated with Montoni who, even before entering Udolpho, is already a figure of patriarchal oppression As a patriarchal object, the castle of Udolpho physically manifests the oppression Montoni inflicts on Emily and Madame Montoni. Montoni’s deceptiveness, for

instance, is manifested in the labyrinthine interior of Udolpho When in Udolpho, Emily repeatedly expresses fears that “she might lose herself in the intricacies of the castle” and is constantly “perplexed by [its] numerous turnings” (258) As such, the physical appearance and the way the castle of Udolpho is described take on new meaning as a symbol of Montoni’s power and desires Consequently, just by a close association with Montoni, the castle becomes a site of patriarchal oppression

The gothic appearance of the castle of Udolpho, particularly the descriptions of its gloominess and obscurity, then gives the castle an immediate association with the sublime. Burke himself even writes in The Sublime and the Beautiful: “Beauty should not be obscure; the great ought to be dark and gloom” (367) The elements of gloominess and obscurity are intertwined in Emily’s description of Udolpho; more often than not it is the gloominess of the castle that renders it obscure: “The gloom, that overspread it, allowed her to distinguish little more than a part of its outline” (Radcliffe 226) Thus, with Emily describing Udolpho as obscure and terrifying, the connection between Udolpho and the sublime is evident since both descriptions are attributes Burke associates with the sublime

The fact that the majority of Emily’s horrific experiences within the castle are caused by male figures, links the sublime with the patriarchy For instance, the mystery of one of her doors being unfastened is later revealed to be done by Count Morano, who, like Montoni, is also a patriarchal figure His association with patriarchal power can be seen in his possessive language towards Emily, as he says things like “you shall be mine” and even goes so far as to “buy” Emily’s ‘love’ from Montoni (262) Therefore, the castle of Udolpho cannot simply be described as a sublime or patriarchal object, rather, it embodies the condition of both

With a close link between patriarchal power and the sublime, Radcliffe portrays the sublime much differently compared to the majority of Romantic poets The distancing from the sublime object is very common among Romantic poets, but especially in Wordsworth’s poetry As he writes in “The Preface to the Lyrical Ballads”, “Poetry” is “emotion recollected in tranquillity” (340) However, in The Mysteries of Udolpho, Emily has no room to recollect her thoughts from the overwhelming experience of the sublime as she is placed directly within the object of the sublime.

“THE SUBLIME DIRECTLY INTRUDES UPON THE CREATIVE SPACE EMILY TRIES TO CREATE FOR HERSELF”

The sublime directly intrudes upon the creative space Emily tries to create for herself This is most evident by the fact that Emily does not write poetry for the majority of the time she is at Udolpho Like Wordsworth, Emily needs the time and space to recollect her thoughts to write poetry again Her temporary escape from Udolpho to Tuscany gave her the space to “recollect the terrific scenery and the horrors she had suffered,” and it is only after Emily had the space to recollect did she experience “a train of images” prompting her to write a new poem (414) In fact, Emily herself claimed that being in the castle had an effect on her creative imagination During her temporary escape from Udolpho to Tuscany, Emily directly attributes her inability to write to the terror she felt within the castle: “These remembrances awakened a train of images, which since they abstracted her from a consideration of her own

situation” (414) The use of the word “abstracted” is an interesting one to describe the loss of her creative imagination within Udolph since the word “abstracted” gives the image of Emily’s creative imagination being robbed by the patriarchal sublime

In a way, Emily is indeed literally robbed of her creative power within Udolpho The obscurity of Udolpho, and by extension the obscurity of Montoni’s patriarchal power, makes it almost impossible for Emily to make meaning of her experiences at Udolpho. She even begins to question if her senses are a good way to make sense of her surroundings; she becomes convinced that “her fancy had deceived her” when she “heard a voice” while at Udolpho (355). This fear that she cannot make meaning of her experiences in the patriarchal sublime is reminiscent of the anxiety of authorship that Sandra Gilbert and Susan Gubar wrote of, the fear that “[the female author can] not fight a male precursor on “his” terms and win” (49).

It makes sense that Emily feels anxiety about authorship during her stay at Udolpho, Montoni has tried twice to control and the meaning of the words to his gain while she was there For instance, Montoni almost tricked Emily into signing away her rights to Madame Montoni’s properties, and eventually did trick her into signing away her rights with the promise he would return her to France These two instances rob Emily of her ability to use her creative imagination since, as exhibited by the fact she writes poetry, Emily often plays with the Derridian conception of slippage, an inherent indeterminacy of the meaning of words However, trapped within the physical manifestation of Montoni’s power and control, Udolpho, Emily is cheated of her ability to interpret meaning on her own terms

Emily’s struggle to interpret meaning on her own terms is reminiscent of the struggles Gilbert and Gubar see the female author

facing: “Unlike her male counterpart, then, the female artist must first struggle against the effects of a socialization which makes conflict with the will of her (male) precursors seem inexpressibly absurd, futile” (49; my emphasis) With Montoni using the fact that society privileges the written word to his advantage, from the lens of The Madwoman in the Attic, by making Emily sign the papers, Montoni forcibly pits Emily’s way of making meaning against society, or “socialization” (Gilbert 49) Having signed the papers, Emily is robbed of any chance to explain what Montoni’s words meant to her (with its indeterminacy of meaning) since society always attempts, through writing, to cement meaning on paper As such, by Emily, any attempt to reconcile her honest mistake would be thereby seen as “absurd” (Gilbert 49)

Having been deprived of her creative freedom, Emily’s mind becomes consumed by imaginings fueled by terror Her inability to enjoy the passages of the poems she once enjoyed best marks the change in her imaginative state After going to Tuscany, the imagination has “recovered its tone sufficiently to permit her to the enjoyment of her books” (418) However, when she is back in Udolpho, Emily attributes her inability to enjoy the poems to the fact that “the mind of the reader is not tempered like [the poet’s] own” (383) Emily’s use of the word “tempered” suggests that she knows her current state of mind is not desirable to enjoy these poems; she cannot tap into the right kind of imaginative state to do so This is evident when, throughout her stay in Udolpho, the word imagination is often followed by the word terror caused by the sublime: “her imagination was inflamed and the terrors of superstition again pervaded her mind” (371). This is in direct contrast to her imaginative state before she entered Udolpho, which often focused on the beauties that her mind could conjure: “And here, other forms of beauty and of grandeur, such as her imagination had never painted” (176) It is clear then, without the space to step away from the sublime, since

she is trapped within it, she cannot even begin to exercise her creative imagination, let alone to its full extent. Thus, it becomes clear that as Virginia Woolf writes, “a woman must have a room of her own if she is to write fiction”, for a woman to be able to exhibit her creative imaginativeness, she must have the space to do so (3)

Without the imaginative space necessary to make meaning of her experiences on her own terms, added to the fact that she is placed within the sublime object, it comes to no surprise that Emily even feels robbed of her reason Emily is not without reason when she enters Udolpho During the beginning of her stay, she often attempts to examine and question superstitious stories from a cool and reasoned perspective This is evident from the reply Emily gives to Annette when she first approached Emily with the idea that there is an apparition that guards the cannon of the castle: “‘Well,’ said Emily, ‘but that does not prove, that an apparition guards it” (255). However, having already been filled with terror by the appearance of Udolpho, and as her anxieties and terror continue to accumulate the more she stays within the castle, her mind inevitably becomes too “overburdened” (249) and “long-harrassed” to continue being reasonable (335) Therefore, it is clear that it is not Emily’s lack of reason that prevents her from examining things calmly when she is at Udolpho, but rather it is because the patriarchal sublime has suppressed her reason

By showing how Radcliffe aligned patriarchy with the sublime, I have argued that women’s creativity is often thwarted under a hetero-patriarchal system Without the space and ability to make sense of one’s experiences, it is inevitable that even the most logical person would fall victim to believing in the supernatural; this was the case for Emily, who recongnized, not even a chapter after she escaped from Udolpho, that she had been overtaken by “foolish terror” for believing in the supernatural (458). Therefore, by redefining the sublime

as a patriarchal object as something that only inspires fear, Radcliffe shows, through the suffering of Madame Montoni and Emily throughout the novel, how the sublime is the condition of women’s everyday lives under patriarchy As such, Radcliffe critiques male poets of the time who go out of their way to experience the sublime when it is the very condition that causes women suffering

Burke Edmund, “A Philosophical Enquiry into the Origin of Our Ideas of the Sublime and Beautiful (1757)”, The Broadview Anthology of Romantic Poetry, edited by Laura Buzzard et al , Broadview Press, 2016, p 365-370

Gilbert Sandra, Gubar Susan, The Madwoman In the Attic, Yale University Press, 1979, https://archive org/details/TheMadwomanIn TheAttic/page/n3/mode/2up

Radcliffe Ann, The Mysteries of Udolpho, edited by Bonamy Dobrée, Oxford UP, 2008

Woolf Virginia A Room of One’s Own

Edited by David Bradshaw and Stuart Nelson Clarke Chichester, England: Wiley Blackwell, 2015

Wordsworth William, “Preface to the Lyrical Ballads”, The Broadview Anthology of Romantic Poetry, edited by Laura Buzzard et al , Broadview Press, 2016, p 340

by Grace Goudie

there is a finite amount of matter, or, everything must die for anything to be born with this our minds are mortal: dreams of sweet figs, fairies that fit in your palm, fables we told by candlelight so long ago when we recognize we owe our bodies to the earth, we let this magic go but a broken branch does not breed death from gifted grafts, new blossoms can grow, with petals hanging like eaves of snow off an aging spruce these blossoms bloom, their bodies guiltless and unrecognizable, to the size of stars pressed between the pages of the night fresh flowers bring new fables, young fairies, ripe figs like a baby’s fist let us make way to celebrate the coming of the summer sun let slow-growing fruits ease the wanting of youth’s bloated tongue

by Grace Goudie

you are watching me watch myself standing naked in the mirror I am poking a bruise on my bicep, a purple spore that has bubbled to the surface of my skin you think that I am thinking about the size of my hips, but I am considering how growth spurts used to make me feel like a new moon orbiting Earth I must look sad to you because you say you’re beautiful, Grace, spoken softly like it’s a consolation prize for an offcentered axis I hate how you conceive of beauty with a man’s eyes, watching this intimate moment unfold in the middle of my room I would rather you mark me by action than by contemplation: rolling out of bed to write poems in the middle of the night, smiling with uneven dimples, loving you but these fleeting moments aren’t what you reference, and I wonder if you will ever see me as I see myself; standing here, naked, watching my reflection in the mirror

bloom.

Bensaou, Lamine “L'Algéroise ” Wikimedia Commons, 26 Nov 2015, https://commons m wikimedia org/wiki/File:L%27 Alg%C3%A9roise02 jpg#filelinks

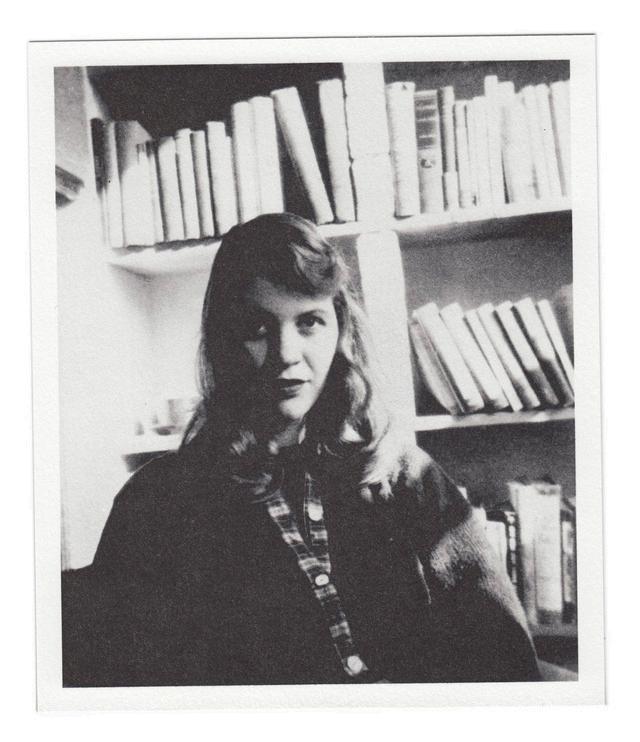

Bettmann “Sylvia Plath in an undated photo ” The New York Times, 8 Mar. 2018, www.nytimes.com/interactive/2018/obituaries/overl ooked-sylvia-plath.html.

Grambow, Madelaine. “Female Reflection.” Flickr, 17 Aug. 2011, https://www.flickr.com/photos/bloodyblacklace/60 53988596/in/photostream/

Jill “Rose in the Window ” Flickr, https://www flickr com/photos/58783060@N05/

Showroom “Musing ” Instagram, 7 Mar 2025, https://www instagram com/p/DG6t7jPttAu/

Tipoune “Les peintures de la galerie des Glaces du château de Versailles ” Wikimedia Commons, 1 Jan 2009, https://en m wikipedia org/wiki/File:Les peintures de la galerie des Glaces du ch%C3%A2teau d e Versailles jpg

Zollernalb. “Burg Hohenzollern mit Schwarzwald.” Wikimedia Commons, 23 Dec. 2007, https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Burg Hohenz ollern mit Schwarzwald2-b.jpg