CUT AND

New Faces, Familiar Courage

As the nights grow long, Tallinn once again becomes a meeting place for cinema – for filmmakers both experienced and emerging, each shaping a region that continues to evolve while remaining true to its roots.

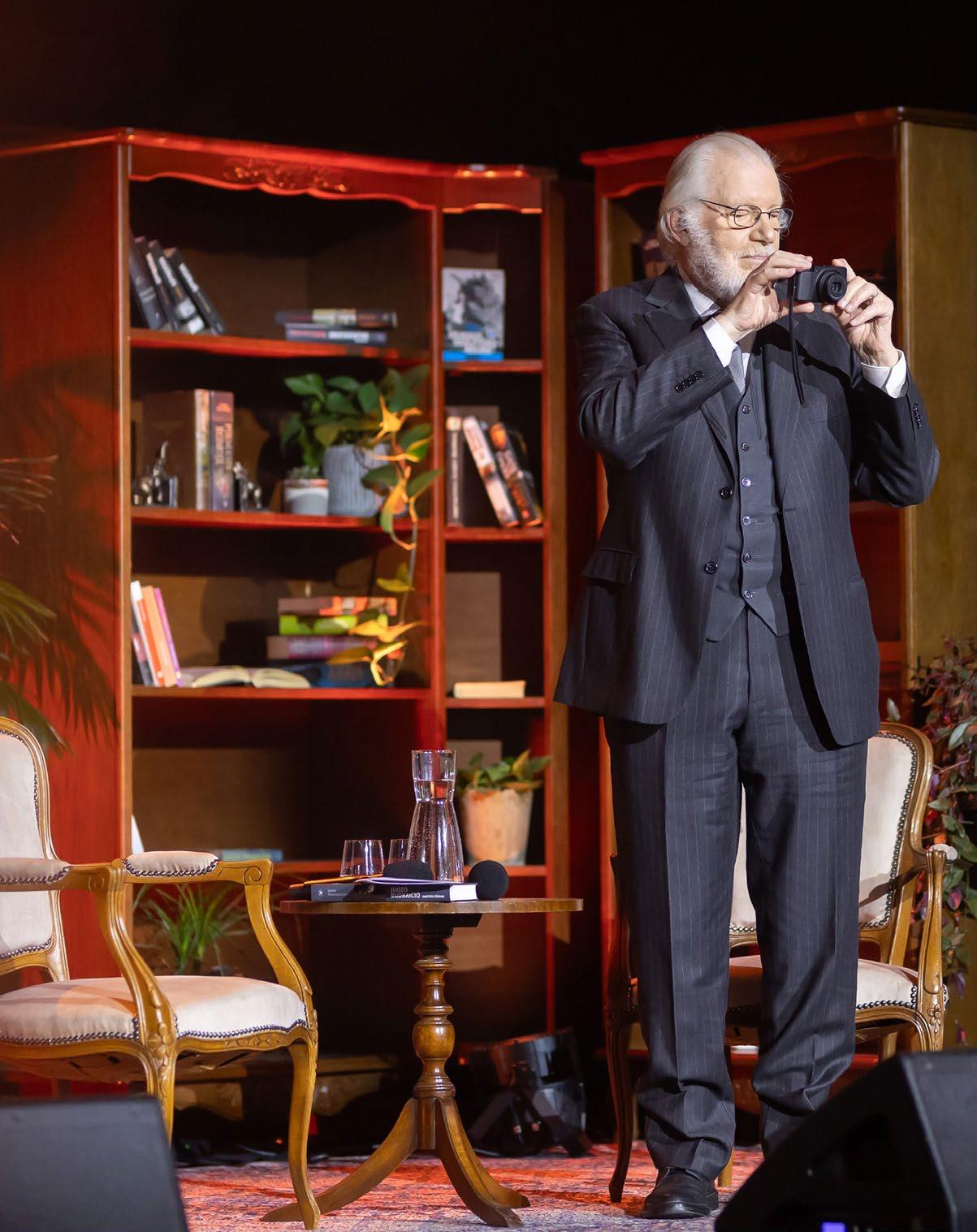

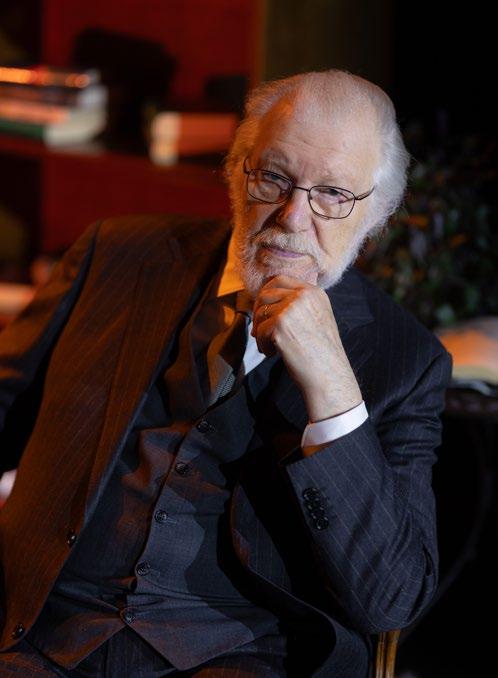

This year, Lithuanian legend Juozas Budraitis receives PÖFF’s Lifetime Achievement Award, honouring a career that spans generations and highlights how deeply rooted the region’s cinematic history is.

The new generation of Baltic filmmakers continues that story with quiet determination. Lithuanian director Vytautas Katkus, whose The Visitor won him the Best Director award at Karlovy Vary, finds drama in stillness and emotion in everyday gestures. Estonian filmmaker Eeva Mägi continues to reinvent cinema language through her independent Mo films — raw, intuitive, and defiantly personal. From Latvia, Alise Zariņa offers a sharp, tender voice on stories of identity, womanhood, and belonging. Together, they represent a new Baltic confidence: small-scale, deeply human, and unmistakably their own.

Documentary cinema also takes centre stage. A new competition section for Baltic documentaries was introduced at PÖFF, recognising that the region’s documentarians are too accomplished to stay in the background. Their films demonstrate a rare balance of precision and emotion. And while Vladimir Loginov’s Edge of the Night competes in the International Documentary Competition, it clearly belongs to the same creative wave reshaping nonfiction storytelling here.

The same energy runs through the Baltic shorts at PÖFF Shorts, where emerging filmmakers continue to surprise with their honesty, humour, and experimentation.

The foundations remain strong around them. Regional film funds continue to be robust, with a new one in Vilnius injecting fresh energy into cross-border collaboration and creative independence. Industry@ Tallinn & Baltic Event continues to bring the wider industry together, covering everything from debut features to high-end TV series.

And as PÖFF celebrates 25 years of Just Film, its youth and children’s section, we are reminded that the future of Baltic cinema begins early – with curiosity, courage, and the simple joy of discovery.

The masters are honoured, the new generation is rising, and the region remains steady – rooted, open, and quietly confident that its best stories are yet to come.

Eda Koppel Editor in Chief

Baltic Film is published by the Tallinn Black Nights Film Festival

E-mail: info@poff.ee, I poff.ee

Editor in Chief: Eda Koppel

Contributing Editors: Mintarė Varanavičiūtė, Kristīne Matīsa

Contributors: Tara Karajica, Andrei Liimets, Elen Lotman, Maarja Hindoalla, Peeter Kormašov, Daniela Zacmane, Egle Loor, Signe Somelar-Erikson, Martina Tramberg, Leana Jalukse

Linguistic Editing: Paul Emmet Design & Layout: Profimeedia

Cover: Alise Zariņa, Eeva Mägi, Vytautas Katkus

Agnese

Photo by Viktor Koshkin

Photos by

Sohvi

Viik-Kalluste, Uldis Cekulis

UNITED by WOLF PACK

PÖFF has become a major Baltic cultural force, known for bold programming and international reach. This year, it launches a campaign to secure its financial future.

Tiina Lokk, Head of the Festival, discusses PÖFF’s role for filmmakers across Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania, and how shifting public and private funding impacts its sustainability.

Wolwes are strong in packs

HBy Martina Tramberg

Photo by Sohvi Viik-Kalluste

ow do you define the festival’s role in the Baltic film ecosystem today?

Over the past decade, PÖFF has established itself as the flagship film festival of the Baltics — a stepping stone for films to gain prominence and attract festivals, sales agents, and distributors. Its strength derives from the synergy with Industry @Tallinn & Baltic Event: today’s project at Industry could be tomorrow’s film in the festival line-up.

PÖFF is the largest export platform for the Baltic film industry. Its broad international reach lets films compete in the context of auteur-driven cinema. Each year, it hosts around 70 countries and nearly 2,000 international guests.

The Industry section addresses the needs of the Baltic film sector, focusing on co-production markets, training programmes, and conferences, with TV Beats developing local TV series. Most importantly, it connects filmmakers with partners genuinely interested in collaboration, where many co-productions and deals begin.

What prompted the festival to launch a new fundraising campaign, Join the Wolf Pack, at this moment?

Fundraising of this kind is common worldwide, especially in the U.S., but less so in Europe, where national

and regional funding often covers up to a third of a festival’s budget. In Estonia, a fragile economy has reduced private sponsorships and state support, while high inflation further strains budgets. The amounts provided by the private sector and the state have also declined.

To uphold its A-class status, PÖFF cannot reduce its budget without impacting quality. Instead of increasing ticket prices, we encourage those who can support the festival directly.

How does PÖFF strengthen collaboration and visibility among Baltic filmmakers internationally?

The festival landscape has its logic: Venice showcases the best of Italian cinema, Locarno focuses on Italian, Swiss, German, and French films, while Berlin and Munich highlight new German films.

The Baltic states have small, uneven film industries, but together they create a strong regional identity that’s easier to promote. As one of the last major festivals of the year, PÖFF complements the “Big Four” — Venice, Cannes, Berlin, and Toronto — by giving films from smaller nations, including the Nordics, valuable international exposure. No one visits solely for Estonian films, but the Baltic and Nordic presence makes Tallinn an appealing hub for producers, directors, and distributors alike. The magic word for PÖFF is synergy.

Where do you envision PÖFF — and the Baltic film scene more broadly — in five to ten years?

Predicting the future is never easy, but I hope the Baltics will soon have strong studios, cash rebates, skilled crews with enough technical workers alongside creative talents, and better funding for local films to raise artistic quality. Filmmaking should be regarded as an investment promoting culture and the economy. Es-

pecially now, global interest in our films and culture is growing — a powerful way to ensure our voices are heard.

On a personal level, what keeps you motivated to lead such a large and complex festival, and what does success look like to you when the Baltic community stands behind PÖFF?

A festival is a constantly evolving organism. The one I started 29 years ago is completely different from the A-class festival it became under FIAPF. Building it in a small market with limited resources was a huge challenge, but within ten years, we earned a respected place among the world’s leading festivals. The journey was challenging — but thrilling.

Above all, I am a visionary and an ideas person. I remain fully engaged as long as there are projects in progress and unfinished goals. However, the time is approaching to start passing things on. Although I am

great at delegating and connecting different people’s ideas, there must soon be new perspectives and directions. A festival must never become fossilised or grow old along with its founder.

What would it be if you could express the festival’s spirit in one sentence?

Synergy, auteur cinema, and a democratically liberal festival where the filmmaker, not celebrity glamour, is at the centre. Friendly and caring.

As Tiina Lokk makes clear, the campaign is about more than balancing budgets — it’s about securing a future where Baltic cinema stands confidently on its own terms. For over two decades, PÖFF has been more than a festival; it has been a cultural bridge linking the Baltic states to the wider film world. Now, as the festival calls for renewed collaboration, the message is unmistakable: the strength of Baltic cinema lies in shared responsibility and vision. BF

Tiina Lokk, Head of the Festival, discusses PÖFF’s role for filmmakers across Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania.

JOIN THE WOLF PACK

To see,you must

Chasing a fox across an airport runway, tracing fresh pawprints in the snow, helping tearful flight attendants photograph a baby hare nestled in their palm, freeing a gull’s wing from barbed wire fencing, or relocating a swarm of bees away from sensitive airport equipment — such is the curious daily routine of professionals with the rather ominous job title “scarecrows”

By Kristīne Matīsa Photos by Uldis Cekulis, VFS Films

look!

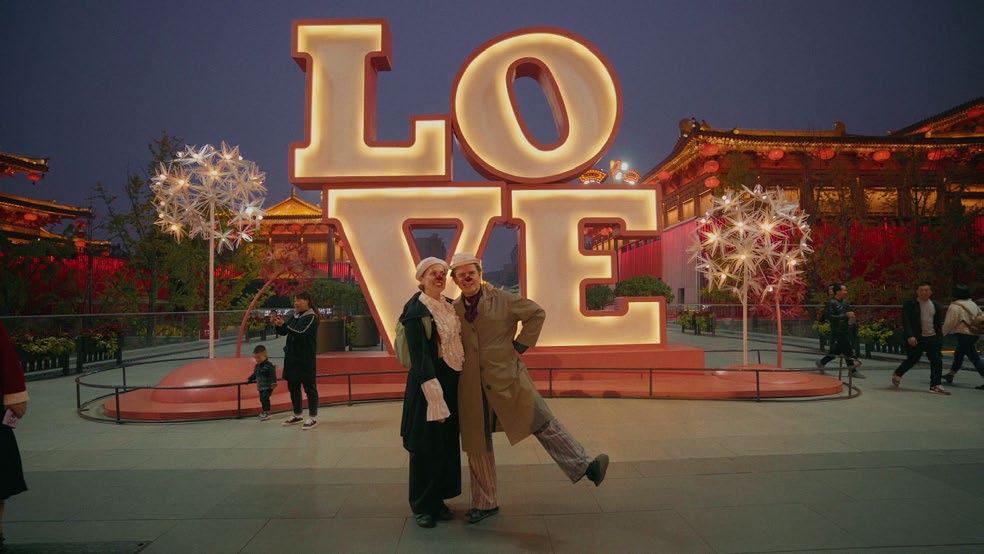

It’s also the name of the Latvian–Lithuanian co-produced documentary Scarecrows, which opens this year’s Baltic Competition at the Tallinn Black Nights Film Festival (PÖFF), symbolising cinema’s – and especially documentary film’s – power to reveal unexpected territories.

The filmmakers describe their Scarecrows as an “airport western,” with its protagonists cast as “runway rangers” operating in a paradoxical environment. Next to the urban citadel of global travel lie forests, meadows, and water – a meeting point for species, each with its own flight path. Humans board giant “metal birds,” for whom real birds pose a genuine threat. Even a tiny snake slithering across the tarmac could trigger disaster. That’s why “bird and wildlife control specialists,” as they’re officially known, patrol nearly 700 hectares of open terrain – a space no fence can truly secure. Yet the most humane aspect of this unusual profession is that it’s not about violence. It’s about learning to recognise and understand animals, so they can be gently persuaded to leave the airport grounds. In truth, scarecrows protect not only aircraft and passengers, but also the animals themselves – preventing fatal collisions that would go unnoticed inside a roaring jet.

THE FORCE OF NATURE

Director Laila Pakalniņa, cinematographer Māris Maskalāns, and the scarecrow team – Mareks and his colleagues – filmed across all seasons over five years at Riga Airport, rarely stepping inside the terminal buildings. Life outdoors, immersed in nature, is nothing new for them. Māris Maskalāns is Latvia’s leading wildlife cinematographer, happiest spending the night in a forest hide with his camera, waiting for a rare bird at sunrise or a woodland scene to unfold. At the airport, he sits in the grass beside a fox, patiently hoping a mouse might appear. Perhaps the strangeness of the setting sparks even greater inspiration than the forest itself. In any case, Pakalniņa and Maskalāns’s earlier documentary Leiputrija / Dreamland (2004), which explored animal life at a landfill site, caught the attention of the European Film Academy and was shortlisted for a nomination. It has since been shown widely at festivals and retrospectives. Pakalniņa credits Maskalāns with teaching her patience – a skill vital for all her subsequent films. “To see, you must look,” she says.

Equally serious, talented, and seasoned are the professionals at VFS Films, the documentary studio that first earned its reputation under the name Environmental Film Studio. Over time, its thematic scope expanded, and it now produces high-quality, expertly crafted films on a wide range of subjects – not just “about birds”. Yet its connection to nature remains strong. Even the studio’s sole fiction feature to date, Upurga (2022), tells a story of nature’s mystical and unstoppable force.

VFS Films is led by internationally acclaimed producer Uldis Cekulis, whose career spans over 30 years. Interestingly, he initially trained as a physicist before entering cinema in the 1990s as a cinematographer – including work on one of Pakalniņa’s early films. Perhaps that’s why he views each film not merely as a “production unit for market distribu-

tion,” but as a work of art to be refined to perfection. For more than a decade, Cekulis has championed international co-productions, often with Lithuanian partners. Scarecrows is co-produced with Lithuanian studio Moonmakers, headed by producer Giedrė Žickytė. The film was edited by Ieva Veiverytė, with sound design by Jonas Maksvytis, and music composed by Paulius Kilbauskas and Vygintas Kisevičius – all in Lithuania.

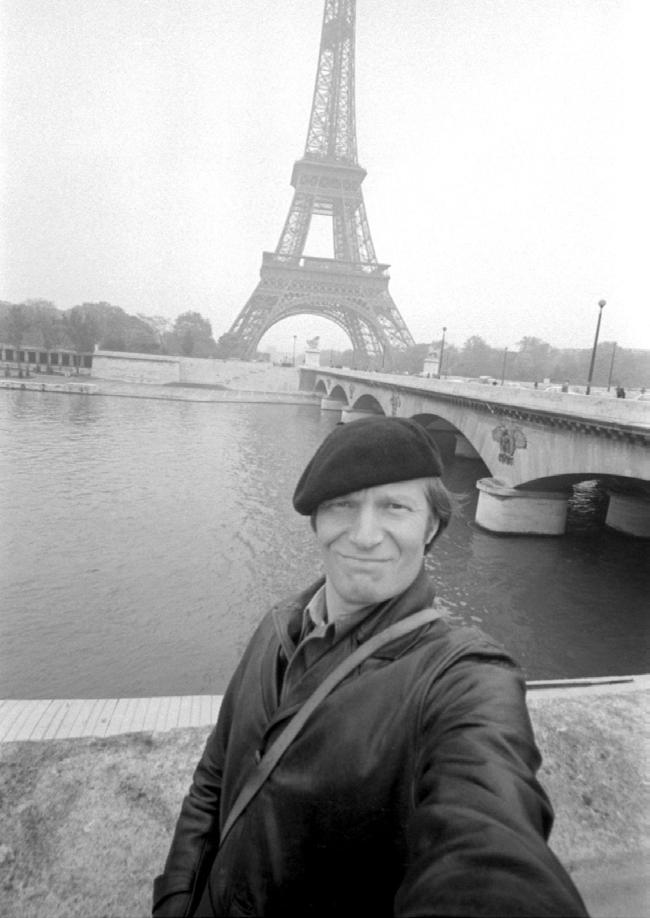

THE PAKALNIŅA ERA IN CINEMA

About thirty years ago, director Laila Pakalniņa (b. 1962) unwittingly opened a new chapter in Latvian documentary filmmaking. Fresh from film school, she made three documentaries in quick succession, exactly as she envisioned them –and this “Pakalniņa Trilogy” was promptly recognised with a FIPRESCI award at the Cannes Film Festival in 1996. That

AS A FILMMAKER,

I see my goal as creating art, not producing a product for global consumption. And this art has wings (and a soul) to cross borders. I know that today is not the easiest time to say something like this. But even now, creating art remains important. Is there a weapon or recipe against fake news, internet trolls, populism,

dumbing down, etc.? Yes, there is: an individual with his or her unique thoughts and feelings. So, I see the transnational appeal of my films – art is also needed in Europe. To preserve something that has become very fragile but still remains very important today – personal emotion and individual thinking. To help people become personalities, not just part of the crowd.

marked the start of a new cinematic journey. Since then, walking that same path, Pakalniņa has become Latvia’s most internationally acclaimed contemporary filmmaker.

She has written and directed over 30 documentaries, five live action shorts, and six fiction features – with several more currently in development. Her work has screened in official selections at Cannes, Venice, Berlinale, Locarno, Karlovy Vary, Tallinn, Oberhausen, Nyon, IDFA and other major festivals, earning numerous accolades along the way.

Many of Pakalniņa’s films are in black and white, though the choice to use or avoid colour is always deliberate. Scarecrows, too, often leans towards monochrome – the grey of concrete runways, autumn rain, or winter snow – yet in every season and at any hour, the neon-yellow safety vests of airport staff and the vivid runway markings flash like warning beacons, signalling that this is a zone where vigilance must never lapse.

Another hallmark of Pakalniņa’s work is her minimalist titling: nearly three-quarters of her films bear single-word names, just like Scarecrows. She explains this with a charming analogy:

“I usually don’t think about what to call a film — the name usually comes with the idea. It’s like, well, you decide you’re going to knit a hat. You start knitting, and you know all along that you’re knitting a hat. It’s the same with a film. I know I’m making a film about a ferry, the mail, a bus, and so on. I know that right from the start.”

SINCE THE TALLINN MARATHON

Pakalniņa’s connection with PÖFF includes a notable milestone. A decade ago, when PÖFF was officially recognised as an A-list festival, her fiction feature Ausma / Dawn (2015) – a LatvianEstonian-Polish co-production – was selected for the main competition. Its

world premiere took place on 18 November, Latvia’s Independence Day, and the film subsequently reached the European Film Academy shortlist and the longlist for the Academy Awards.

To mark its selection, Pakalniņa ran the full 42-kilometre Tallinn Marathon in September, turning the event into the world’s longest film-release announcement: the back of her shirt bore the message that Dawn would premiere at PÖFF in November. She also ran at sunrise on the day of the premiere. In fact, she runs every morning at every festival she attends – and has completed more than ten marathons. She runs daily at home, too. “You won’t believe it, but I do it for the films!” BF

Scarecrows

Director & Scriptwriter: Laila Pakalniņa

Cinematographer: Māris Maskalāns

Editor: Ieva Veiverytė

Composers: Paulius Kilbauskas, Vygintas Kisevičius

Sound director: Jonas Maksvytis

Main Cast: Mareks Arbidāns

Producer: Uldis Cekulis

Co-producer: Giedrė Žickytė

Produced by: VFS Films (Latvia), Moonmakers (Lithuania)

Year of release: 2025

90 min

Main team of “airport western” – “scarecrow” Mareks Arbidāns, cinematographer Māris Maskalāns and director Laila Pakalniņa.

THE ART OF EVERYDAY THE

Vytautas Katkus is one of the most recognized filmmakers of his generation in Lithuania. As a cinematographer, his work spans more than thirty short and feature films, including Aistė Žegulytė‘s documentary Animus Animalis (2018) and Saulė Bliuvaitė’s Toxic (2024). But Katkus is not only behind the camera – he also directs. This summer, his debut feature The Visitor premiered at the Karlovy Vary International Film Festival, where he received the Best Director award.

By Mintarė Varanavičiūtė Photo by Audrius Solominas

In this conversation he reflects on his path in cinema and the creative process behind the quiet, human stories.

Let’s start from the beginning. How did cinema find its way into your life?

I wasn’t one of those people who grew up watching films all the time, dreaming of becoming a filmmaker. For me, movies were more of an entertainment. I imagined myself doing something more technical, maybe working with computers or numbers. But then, quite early on, I realized that film and technology aren’t so far apart. In cinema, you always have a tool in your hands, something to create with – and that means there’s never any routine, which I love. Once I started exploring filmmaking, I found myself watching more and more movies, music videos, anything that told a story through images.

You graduated as a cinematographer, but later started directing. Where did you learn to direct?

There isn’t really one clear answer. I think I learned a lot just by being around people – friends who studied directing, the directors I worked with as a cinematographer, and, of course, from the films I love watching myself. I never had a single moment when I decided, “Okay, now I’m a director.”

It actually started with a small idea for a script, something drawn from real moments in my own life

– things I didn’t want to forget. I sent that idea to a few friends in film, and from time to time I’d come back to it, changing scenes in my head, trying to see what it could become.

Back then, I was really fascinated by films where the image itself becomes a kind of character – where you can tell a story or create a feeling just through visuals, something that’s hard to put into words. I wanted to see if I could do that too – to tell a story purely through what you see. At one point, I asked myself whether to invite a director friend who already had experience, or to just try it on my own and see where it would lead. In the end, I decided to do it my way.

Your short films Community Gardens (2019), Places (2020), and Cherries (2022) have all screened at major festivals – from Cannes to Venice. Let’s go back to 2019 – how do you remember that time?

When producer Viktorija Seniut and I finished Community Gardens, we didn’t really have big plans for it. We didn’t even know much about how the festival world worked. So when we got the news that the film had been selected for Cannes Critics’ Week, we were honestly shocked – and incredibly happy. Then it hit us that the festival was just a month away, and the film wasn’t even completely

finished! That moment taught me a lot about the importance of letting go – about knowing when to say, “It’s done.”

Critics’ Week took such good care of us. They didn’t just select the film – they welcomed us, introduced us to the community, and made us feel part of something bigger. That recognition gave me a quiet kind of confidence. After the screening, I felt that maybe I was moving in the right direction. I realized that I could make the kind of films that feel true to me – and that there might be at least a few people who connect with them.

Where do you find inspiration for your work?

Mostly in everyday life – small, ordinary moments where nothing much seems to happen, yet something shifts inside. I’m drawn to situations that aren’t about what you see directly, but about what you feel underneath – relationships with parents, friends, the simple act of being together. So inspiration usually comes from emotional states, not from big events. Of course, I’m also inspired by other art forms – music, painting, photography, literature – but those come later, when I’m looking for ways to wrap everyday themes in a cinematic form.

Do you find time to watch films yourself?

I try to watch as many films as I can. You can learn something from every film. Of course, sometimes I

Inspiration for Vytautas Katkus comes from everyday life –small, ordinary moments where, at first glance, nothing much seems to happen.

have to watch them for technical reasons, but I prefer to watch as a viewer, not as a cinematographer analyzing how something was shot. I want to be immersed. I enjoy seeing a wide range of films – a lot of independent and arthouse cinema from all over the world. I think it’s important to understand what’s happening in film right now, where it’s heading, how it’s changing.

Do you have any “rules” when making a film?

I like working with individuals who are not only great professionals but also genuine people. That’s why I often make films with friends, or with people who later become friends. I want filming to feel comfortable and human, not stressful or overly rigid. I believe that to create a film full of emotion and atmosphere, everyone on set needs to feel good, supported, and respected.

Vytautas Katkus won the Best Director Award at the Karlovy Vary International Film Festival.

The Visitor premiered at Karlovy Vary alongside Gabrielė Urbonaitė’s Renovation, where you worked as cinematographer. What was that experience like?

I’d heard that Karlovy Vary really values filmmakers and attracts people who genuinely love cinema – and it’s true. What mattered most to me was having our team at the premiere. We’d lived and worked together for a month, and everyone gave more than what their job required. Since Gabrielė’s team was there too, there was a strong sense of mutual support.

I remember thinking I’d feel calm after the premiere – but the next morning I woke up anxious, wondering how the film would be received. Before the premiere, I could still change things. After that, the film had to live on its own.

You co-wrote the screenplay with Marija Kavtaradze, your longtime friend and collaborator. How did that process go?

Marija and I have known each other for more than half our lives, and we’re close friends. Writing together was a really warm, natural process – we didn’t set strict rules about who does what. Marija has more experience

in writing, but she always tried to capture in words what I wanted to express visually. The idea itself came from old memories – fragments of moments that somehow stayed with us and began to connect.

You often work with non-professional actors. In Cherries, you acted alongside your father, and The Visitor also features real people from your life. What does that bring to the film?

It’s something I think about early on, but I usually confirm during the process. In Cherries, I liked the idea of acting with my father, but we still did casting and took time to decide. With The Visitor, I wanted a mix – some professional, some non-professional actors. From the start, it was clear which roles needed trained performers, and which could come from real people we knew. That mix adds a sense of honesty – a bit of documentary truth. Non-professionals bring their natural selves, while professionals give structure and confidence.

Sound also plays a key role in The Visitor. Can you tell us more about that?

I worked on the sound with Julius Grigelionis. Before filming, we watched a lot of movies together and talked about how they used sound – how bold or experimental they were. It was a great learning experience. For this film, I wanted everything we recorded on set to feel real. The songs you hear in the film were actually playing – from phones and radios – so the actors naturally reacted to them. It’s not easy in post-production, but that authenticity matters to me. For example, if the camera is far away, the voices also sound distant. Sometimes we shaped the sound around what a character hears or feels. The idea was for sound to not just accompany the image, but to deepen it.

Both lead roles in The Visitor were played by non-professional actors.

The island in the film is visually striking. How did that idea come about? When we were writing, we imagined a real island, but once we decided to shoot in Lithuania, we knew we’d have to build it. No one on the team had done anything like that before, so it became a fun learning process. The island was the only thing created entirely from scratch – but it needed to work both visually and physically. It’s like a place from a childhood dream, somewhere you’d want to reach. There’s a sense of quiet surrealism, like in the whole film, where you’re never quite sure what’s real and what’s imagined.

Which of your latest projects as a cinematographer are coming out next?

In November, Aistė Žegulytė’s documentary Holy Destructors will premiere at the International Documentary Film Festival Amsterdam (IDFA) – a project we worked on for nearly six years. That same month, Gerda Paliušytė’s documentary Ship will be released in Lithuania, and in spring, Renovation will also premiere locally. Both Holy Destructors and Renovation will be presented at POFF, too. BF

THE VISITOR 2025 | fiction | 111 min | Lithuania, Sweden, Norway End of summer. Danielius (in mid 30s) makes a return to his hometown to sell his parents’ flat. Having nowhere to rush, he reconnects with people and the town that’s no longer his. He is confronted with a quiet sense of loneliness. But instead of resisting it, he allows himself to explore it.

Director: Vytautas Katkus Scriptwriters: Vytautas Katkus, Marija Kavtaradze Cinematographer: Vytautas Katkus Editor: Laurynas Bareiša Sound Designer: Julius Grigelionis Production Manager: Gabrielė Misevičiūtė Production Designers : Lisanne Fransen, Ieva Rojūtė Costume Designer: Morta Jonynaitė Make-Up Designer: Jurgita Globytė Cast: Darius Šilėnas, Vismantė Ruzgaitė, Arvydas Dapšys

Producers: Marija Razgutė, Brigita Beniušytė Co-Producers Elisa Pirir, Anna-Maria Kantarius Produced by: M-Films (LT), Staer (NO), Garagefilm International (SE) Sales: Totem

The island is like a place from a childhood dream, somewhere you’d want to reach.

by

Photo

Paulius Makauskas

Oscar Season

The Baltics Bring Their Best

The Baltic film trio – Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania – is again stepping onto the world stage with their official entries for the 98th Academy Awards.

By Eda Koppel

Baltic cinema’s relationship with the Oscars has been a slow but steady ascent. A decade ago, Estonia’s Tangerines (Mandariinid, 2015) became the first Baltic feature nominated for Best International Feature Film, opening doors and raising expectations for the region.

Then came Latvia’s breakthrough last year, when Gints Zilbalodis’ animated masterpiece Flow not only became the first Baltic film to win an Oscar – for Best Animated Feature, but also earned a nomination for Best International Feature Film. This double distinction made headlines worldwide.

The night marked a significant milestone for Baltic cinema. The ceremony’s host, comedian Conan O’Brien, even joked, “The ball is now in Estonia’s court.” A year later, the challenge has been accepted –and expanded.

ESTONIA: ROLLING PAPERS

BY MEEL PALIALE

Estonia’s official submission, Rolling Papers by Meel Paliale, captures the restlessness of youth in a world of endless freedom and no easy answers.

The film follows Sebastian as he navigates friendship, ambition, and uncertainty with humour and tenderness – qualities that feel unmistakably Estonian.

Produced by Tallifornia, the film exemplifies a confident new wave of local filmmakers unafraid to blend irony and sincerity. The Estonian Film Institute praised it for “reflecting the spirit of a free society with all its possibilities and uncertainties.”

LATVIA: DOG OF GOD BY LAURIS AND RAITIS ĀBELE

Latvia continues its adventurous streak in animation with Dog of God, an audacious rotoscope feature by brothers Lauris and Raitis Ābele.

Set in 17th-century Livonia, the film blends religion, myth, and madness with painterly motion. It premiered at the Tribeca Festival in New York, where critics praised its bold visuals and haunting spirituality.

The Latvian selection committee observed that Latvia has established a presence in the global film scene through “unusual animation”, and Dog of God is its next daring chapter. Following Flow’s Oscar triumph,

Rolling Papers

A moment of triumph as Latvia’s Flow makes Baltic cinema history.

it serves as a reminder that Latvian animation is no longer a niche – it’s a movement.

LITHUANIA: THE SOUTHERN CHRONICLES BY IGNAS MIŠKINIS

Lithuania’s choice, The Southern Chronicles by Ignas Miškinis, takes us to the chaotic optimism of the 1990s, when the country and its youth were redefining freedom.

The film has become a national sensation: over 411,000 viewers, twelve Silver Crane Awards, and the title of Lithuania’s highest-grossing film.

Committee chair Neringa Kažukauskaitė described it as “a film bursting with vitality and authenticity” – a statement that captures its nostalgic energy and modern relevance.

BALTIC SHORT ANIMATION

TAKES FLIGHT – TWICE

Estonia’s animation scene, long a source of quiet national pride, is also back in Oscar contention with two acclaimed stop-motion shorts now qualified for the race.

Winter in March by Natalia Mirzoyan (Rebel Frame, Estonia / ArtStep Studio, Armenia) narrates a young Russian couple fleeing their homeland after the invasion of Ukraine. Mirzoyan creates a tactile, dreamlike journey through guilt and exile using puppet animation, fabric, and embroidery. Combining puppet animation with embroidered textures makes it intimate and political – and it has already won the

Heart of Sarajevo and Cannes La Cinef third prize.

Anu-Laura Tuttelberg offers a poetic contrast with On Weary Wings Go By, an Estonian–Lithuanian co-production between Fork Film and Art Shot. Filmed over three winters on the Estonian coast and in northern Norway, the film follows a porcelain girl wandering through a frozen world where birds have flown south – a gentle reflection on time, nature, and transience.

RUN for the Golden Man

The short premiered at Locarno, screened at over 85 festivals, and collected major prizes, including DOK Leipzig’s Golden Dove, and Animafest Zagreb’s Golden Zagreb Award.

Mirzoyan and Tuttelberg’s works reaffirm Estonia’s place as one of the world’s leading voices in artistic stop-motion – small-scale, handmade, but with global resonance.

THREE NATIONS, ONE STORY

From Estonia’s introspective realism and lyrical animation to Latvia’s fearless mythmaking and Lithuania’s raw post-Soviet energy; the Baltic film industries enter Oscar season with a mix of distinct styles and shared ambition.

If last year belonged to Latvia, this year might very well be Estonia’s or Lithuania’s turn. As always, the true victory lies in how these three small nations continue to punch well above their cinematic weight. As someone said, smiling, “The Baltics used to whisper at the back of the world’s cinema hall. Now they’re sitting in the front row and have brought subtitles.” BF

Winter in the March

The Southern Chronicles

Dog of God

On Weary Wings Go By

Baltic animation soars between belief and dream.

Two Baltic films capturing the echoes of change, from the warmth of freedom to the chill of departure.

AT THE EDGE NIGHT OF THE

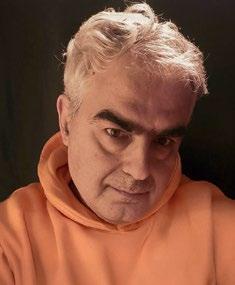

Documentary filmmaker Vladimir Loginov is known for films like Anthill (2015) and Celebration (2019), with Hippodrome (2022) being his latest. His style can be described as observational and poetic. At the Tallinn Black Nights Film Festival, his new documentary Edge of the Night (Ööäär, 2025) will have its international premiere in the Doc@PÖFF International Competition programme.

By Peeter Kormašov Photo by Max Golomidov

Edge of the Night doesn’t feel like the familiar Tallinn but rather like a city in a foreign country. You also avoided the usual nightlife spots. When someone says “nightlife,” you immediately think of clubs -which we do have in the film - but I wanted to avoid clichés. It might seem that I collected these moments one by one, but actually, it all happens every night. Especially when we were shooting at the emergency call centre – it’s crazy! It seems impossible that every second there’s a new call coming in.

Watching the camera focus on the main character, the blonde woman, you can really feel the tension. The call in the background, where a woman has barricaded herself in the bathroom from a violent husband... It’s even more intense because you don’t see the situation. For me, this was a great example of how sound alone allows you to imagine what’s happening and how reality is created through sound. We used the same effect with a man waiting in a hospital while his wife gives birth.

Was the cinematographer again Max Golomidov?

Yes. It was me, him, and the sound designer Dmitry Natalevich on site. The producer Janika Möls also made a tremendous contribution, I’d say at least as much as for a feature film.

Was there anything especially captivating that you had to leave out of the final version?

We filmed at the Tallinn Observatory, and I wanted to make a connection with the cosmos. The footage was good, but I couldn’t find a place for it. We also had to cut scenes from the Tallinn water works hangars in Paljassaare.

I wanted to include Rusalka (Mermaid, a popular warship memorial in Tallinn) and even rented a crane, but on screen it didn’t look the way I wanted. Still, it was an interesting experience; nowadays, you’d normally film something like that with a drone.

The other sculptures in the film work well, I think. The portraits of graveyard sculptures are also inhabitants of the city. That was the biggest ethical question for me: they didn’t give permission to film them, but I’m still using the footage.

EDGE OF THE NIGHT

Director: Vladimir Loginov

Cinematographer: Max Golomidov

Sound: Dmitry Natalevich

Editor: Hendrik Mägar, Vladimir Loginov

Producer: Janika Möls

Production: Anthill Films (Estonia)

Co-production: Korraks lm (Estonia)

Festival distribution: Raina Films

Andy Norton, andy@rainafilms.com

Inka Achté, inka@rainfilms.com

Production Year: 2025

Languages: Estonian, Russian, English

Duration: 92 min

How did you get so close to the swingers? Why did they let you film them? In a way, they go there to show themselves. Maybe they’re not ready for so many people to see them, but we don’t show faces clearly. We asked whether they wanted to cover their faces or not.

People there are super friendly, looking for a partner or a friend. They smile, chat, and encourage body positivity. A nice crowd, many from abroad, like Finland and Latvia.

We shot there a couple of times. Some people said it was okay to film them but not to show it in the movie. That’s understandable, it’s a private world, even with politicians among the visitors. They have their own Telegram group, which surprisingly has around 10,000 members.

We also see other alternative clubs. Usually the “crazier” or more underground a place seems to the “normal” world, the nicer the people are.

Always. In my experience it’s often the opposite – the danger comes from where you least expect it. Even biker clubs are full of completely normal people.

What about the young guys wrestling at the bus station? It looked like they were just having fun.

Yes, and it’s also easier with young people. They film themselves all the time. If you see something foreign or uncomfortable, it doesn’t mean it’s uncomfortable for them – it’s their normal life.

You think you’re filming an interesting face, something dramatic – but not for them. Will the audience see it as I saw it? How will the people themselves see it? I have no ill intentions, what’s there is pure beauty. Also, the viewer is a co-author, as in any art form.

You’ve said you don’t want to solve problems with your films. I can’t. Even if I show something, I don’t want to criticise it. People live their lives as they wish. Even if you feel you should help them, very often that’s not true – it’s just your own perception. Of course, when someone is sick or in danger, that’s a different story. But usually, on a human level, there’s no difference, and the problems are the same.

Was it hard to get close to people?

Sometimes you see a person for the first time, start filming, and they just continue their lives like nothing’s happening. Some people are already “in character,” like police officers or firefighters. Others ask where the footage will be used – “Will something happen when my boss sees it?”

We didn’t need too many people. The woman in the emergency call centre became the main character – she volunteered when they asked at work who wanted to participate. There were a couple of candidates, and we met with them.

What other obstacles did you face?

At the maternity hospital I thought it would be easy to find parents happy to have such footage later. But women are in

For me there is no distinction between a feature film and a documentary.

a completely different reality before childbirth and if you don’t have an agreement beforehand, it’s not happening. Also, KAPO (the Estonian Internal Security Service) checked on us several times. The water works, the emergency call centre, and the airport are all objects that automatically report activity to them.

Did you consider including police stations or homeless shelters?

I didn’t want to show too much police or ambulance work – it’s been done too many times, it would just be another cliché like the clubs. It would also make a different film, and you can’t show patients on screen anyway.

The guy rummaging through the trash – I don’t know for sure if he’s homeless. He might be a dumpster diver. Again, all people are the same. Of course homelessness is a problem, but it can also be a choice. Some are offered help and reject it.

Again, I don’t want to put labels on anything. For me, everyone is the same.

How did you choose the locations? What kind of story did you want to tell?

As often, I didn’t want to tell a story. I just had this thought that at night everything is different. When you don’t sleep, your thoughts seem super clear, even genius –but by morning they become total nonsense.

How reality changes in your head is fascinating. My initial thought was to see if that’s really the case. During editing I couldn’t find a connecting thread, and then director and producer Liis Nimik sent me an article from Aeon magazine called “Spinning the Night Self,” about insomniacs and the positive sides they find in their condition. Why was I even looking for something different from my original idea?

The article was excellent – like a short story. I wrote my own text and was looking for someone to read it with a deep voice. I didn’t want an actor since they read too perfectly. I also didn’t want to make a radio drama. I found the Estonian rapper Reket (Tom-Olaf Urb) to read the text, and used the voiceover as a connecting element instead of a main character.

Your films often deal with places or worlds that are disappearing. That’s especially true of Hippodrome (2022), which has since been demolished. With Edge of the Night, you seem to have changed the subject.

I think I’m looking not for what’s disappearing, but for what exists. In a way, Edge of the Night is the same and those fascinating night-time thoughts that are gone by morning. Everything is different at night. Even people who watch the film and want to have the same experience won’t have it. Just fragments, to experience this all in one night is impossible.

Jim Jarmusch also comes to mind, since his films often take place at night and create this distinctive nocturnal reality.

It’s especially different when you’re not part of it – when you just observe that world for hours. Filming a kiosk where people buy shawarma, you see all kinds of people – young, old, someone with a Mercedes, someone with a tractor... Like in Buddhist philosophy, you just sit on

head of programming at DocPoint. They represent art films, documentaries, and shorts. At the moment we’re waiting for responses from other festivals, and Raina Films is building a strategy.

Actually, even though people make a distinction between documentary and fiction, I don’t understand it – for me, there’s no difference. Edge of the Night isn’t strictly a documentary either.

the riverbank and everything flows past. People often say my films are slow-paced. They are slow, but at the same time full of themes and places. Don’t rush, and you’ll get everything.

The film will premiere at the Tallinn Black Nights Film Festival. It’s the only Estonian film shown in the Doc@PÖFF International Competition. Do you have other screenings planned?

We have a Finnish distributor, Raina Films, and Inka Achté, who is also the

or “Who’s your main character?” Once I was at a pitching session for a film about the war in Ukraine. One powerful scene had a completely black screen – the lights go out in a window when the bombing starts. TV producers said, “We can’t show that – there can’t be a black screen, even for a few seconds. Viewers will change the channel.”

Incredible, but that’s the reality. They say, “We don’t have a shelf for you.” It’s

I agree. Most of the time I felt I was watching a fiction film. People often say that about my work. With Anthill, they said the acting was bad – that’s funny. When you think about early cinema - the Lumière brothers, Dziga Vertov - there was no distinction. And with Godard’s last films, I’m not sure if they’re documentaries or fiction. I don’t need to name it; I’m just watching the world.

But when you pitch a film, decision-makers say, “This isn’t our format,”

the same with festivals: they need an audience, and it’s easier to attract people with familiar formats like comedies. There have to be political themes, like the conflict between Palestine and Israel. No festival director sits there thinking, “I really need a film about night-time.” You have your fans, and other screenings will come later if the film is accepted. Even some Oscar winners went through the same struggle – they had trouble getting funding at first. You need a decision-maker with good taste and passion. BF

Healing Old Wounds

Latvian director Alise Zariņa is on a mission to heal old wounds and raise questions while making us feel good in the process.

By Tara Karajica Photo by Agnese Zeltiņa

In her latest endeavour, Flesh, Blood, Even a Heart, the ostensibly dark topics of slow death, fear of abandonment, emotional estrangement, and the contempt some feel for their parents; mix effortlessly in a surprising and captivating blend of humour and humanity. Zariņa discusses the film, her work, her activism, contemporary Latvian Cinema, and what she is up to next.

Can you talk about your time at the Baltic Film and Media School?

I really liked it! I went to France to study advertising and it was really hard for me as a foreigner in a different country. It was weird when I came to Tallinn –there were lots of foreign people too. It was also not my country, of course, but we immediately clicked. And I remember, in the first year, all the guys were so confident that they were going to make great films, and all the girls were more realistic and shyer. I befriended those guys and we became really good friends and worked together. I still go to PÖFF more or less every year. I have this nostalgia for Tallinn. It really gave me a new perspective on everything.

How did Flesh, Blood, Even a Heart, come about?

Several of my friends lost their fathers more or less the same year, and most of them had really bad relationships with them. They were shocked how hard the process of grieving for somebody, who you thought you had already grieved, was for them. At the same time, my grandfather was about to pass away, and through my own grief I observed that weird feeling one gets in hospitals.

When I went to Berlin for a script consultation for this film, the French-German lady told me: “Well,

what you have written is so Kafkaesque.” But actually, everything I had written about the hospitals was either from my own experience or from collecting people’s stories. Nothing is made up from thin air, even if I have put the legal disclaimer that everything is made up so the hospitals wouldn’t get mad at me. When I was in the hospital and I knew my grandfather was dying, I was observing what was happening around me all the time. And I knew I was in a film nobody wants to make. It was very important for me not to critique the doctors or the nurses, but the system itself, because it’s all about two things: post-Soviet times, and lack of money, and somehow those two things came together. For me, even if the film turns out to be not that great, if I managed to catch this unique experience we still have in post-Soviet countries, that’s already something. Because I know that most of us unfortunately go through that at some point.

Liv, the protagonist, is in a very vulnerable place. She is reliving her childhood trauma, her relationship with her parents – especially her father – is difficult, her marriage is falling apart… I’m not trying to create a character that is very specific to the times, but rather create her in a very particular moment of her life, when she is holding onto the little things she has. I was trying to push through this moment with something we call the “Childless Mother” moment when you’re forced to take care of everybody around you, but you have very little understanding of how to take care of yourself. I wanted to capture that moment in her life. If I think about the character in a bigger sense, I don’t think she’s a person who wants a family right now. I think at this point she just wants to hug her inner child. But, of course, it comes out of this need to make a normal family. I think that if it were real life, she wouldn’t go for a swim, she would go to therapy, honestly. Liv is more of a symbol of this first post-Soviet generation – a woman who is a bit lost and who has to rebuild herself.

There are so many themes in your film. It’s a story of slow death, of a broken heart, of fear of aban-

DIRECTOR

donment, of suffocation of our inner child, of contempt for our parents, of emotional estrangement, of how our upbringing has an impact on our life. Why was it important to delve into all these elements in this particular film?

It was important to give these glimpses of a situation where you can actually be in the character’s skin a bit, and feel how this world is kind of falling on her. With everything I’ve done so far, I’ve tried to keep it light, humane. This is my second feature. I’m now starting my third feature on an idea level, and the further I go, the more I want to experiment with how far can I go into the darkness to find some kind of lightness there. Making fun of death or a broken heart is a risky thing. Like I said before, when I was in the hospital, it kept striking me how absurd it all was. It’s important for me to find these little relatable moments that unlock it.

It’s mostly empathy and connecting my character to the audience – at least that’s how Cinema works for me. I can admire beautifully made films but, at the end of the day, I’m still that person who will go to the cinema because she wants to feel. There’s also another element in the film – modern relationships and their various iterations – that you explore in different ways. Can you elaborate on that?

For me, the three-generation span was important because the sixty-year-old women who have really taken up their duty of taking care of the men, and they

wouldn’t leave them, and they feel responsible – that’s the mother. She is quite literally taking care of the man, who is her ex. Liv, on the other hand, is trying to quit this way of living. And I really want her to be. That’s my wishful thinking. That means this generation is learning a lot. Marcis’ parents appear for a very, very short period of time, but they are the other kind of stereotype: the illusion of a normal family in which the mother has this soft power in the family, and that creates situations where Marcis is a bit helpless because he’s used to being told what to do. That comes again from the generation before, and he has to really learn how to parent and how to manage this new family. Liv wants something, but when she’s asked what she wants, she can’t actually articulate it. Neither of them has role models, so they have to reinvent that. Then, there is the young generation, which is much more open and much more communication oriented. When the young girl gives advice to Marcis, it’s cute and funny and naïve, but I think it’s very refreshing to see how they already do not repeat these mistakes, and how they reflect much more. It’s about three different ways of communicating, three different models.

Was the process healing or cathartic?

It gave me a lot of space to think about different things. I had a very interesting interview during the shooting, when a journalist came to see the set, and she was asking me: “What’s the film about?” and I’m like: “It’s about how we’re still angry at our parents to a certain degree.” And she’s asking: “And it’s about forgiveness and how you should forgive.” I’m like: “Well, not necessarily.” And she goes: “Maybe it’s about how you can keep being angry, but forgiveness is important.” I’m like: “Well, yeah, but I mean, that’s not about that.” And then, I’m looking at the journalist and I’m realizing she’s talking to herself. I thought that was a really funny episode. I thought about that a lot afterwards. When we think about closure, we think about this clean slate and that the past is the past. I thought that maybe this sort of film can help understand and accept that some issues are unresolved. Sometimes, it’s better than saying: “I’m trauma free. I’ve healed myself. I’ve found a new me.” It’s really important to

Alise Zariņa and the DoP of the film Mārtiņš Jurevics on the set.

Alise Zariņa with the childactress Ērika Vilisone.

see what happens when the film comes out, how it’s going to be seen, how people will relate to it.

Can you talk about your writing, activism and feminism?

That’s a form of procrastination! I read and I write both about social topics and Film. I’m trying to write less about Film. I used to write about local films. I do not do that because I don’t think it’s fair to be making films and writing about films. I did have a dream that I would one day write a very critical review of my own film as a performance, but I have not done that yet. That’s still on my list.

What I like about living in a small country is the feeling that you can actually do something – you can reach people. Every time I think about moving abroad for better weather, better politics, or something else, I also think that I’m very grateful that the size of my country has helped me actually matter a little bit. Maybe it’s an illusion, but it’s a good illusion that in a small country you can, by relatively small means, get attention on a subject. I went to a protest and I drew myself a blue eye and did a little speech and it reached people. I don’t think I can wake up in the morning, go to a protest and get on TV just because I did a little activism thing anywhere else. That’s why I keep doing that. I also feel a bit responsible for my country. I feel responsible that I can’t just complain because I like complaining, as most people do. But, at this point, I’m also a bit tired because I have the feeling that things are going in circles. I question myself a lot.

How do you see Latvian cinema today?

It’s getting better in Latvia now thanks to Matīss Kaža and Gints Zilbalodis. Flow got a lot of attention and I admire them and what they have done. They showed what you can do with a low budget, but when they talk about the film, they talk a lot about that. That’s not the norm, and I think that’s very important because, of course, it all depends on money, but we’re finally getting contemporary stories out. That’s very important to me. I think dwelling on the past is important too, but I think we’ve been too passionate about that. I’m seeing people telling more contemporary stories, stories about the recent past, and that makes me happy. I still think that we have to work on normalising women’s stories instead of separating them. We have a very good film community in which people stand up for each other more and more. That’s what I appreciate the most. There’s a lot of support and it’s moving in the right direction. Of course, more money, more time, more films, more exposure, would be great, but I’m an optimist, and I haven’t heard anyone say that we don’t need women’s stories in a long time. That’s also good.

What are you working on next?

I’m working as a co-writer on a true story that happened in Latvia in 2022 from a very, very personal perspective. What I can tell you, and what’s on my mind a lot, is something I call “new patriotism,” because the

What I like about living in a small country is the feeling that you can actually do something.

old kind of patriotism – we don’t need that. That’s horrible. That’s like nationalism, and nationalism will become very strong and very present in Europe in the future. So, I’m thinking a lot about how to redefine this notion of patriotism for my generation, how to talk about the place, the people and our feelings for the homeland from a new perspective, and not from a place of bravery or fear, and not being better than others. Maybe the next logical step is for me to try and see how to place ourselves on a map, and talk a bit about the map itself. It’s called Not My War BF

FLESH, BLOOD, EVEN A HEART

Drama, 90 min, Latvia

Scriptwriter & director: Alise Zariņa

Director of photography: Mārtiņš

Jurevics

Production designer: Juris Žukovskis

Editor: Armands Začs

Sound designer: Matīss Krišjānis

Composer: Oskars Jansons

Costume designer: Ance Beinaroviča

Makeup designer: Emīlija Eglīte

Casting by Beatrise Zaķe, Laik/A Casting

Cast: Ieva Segliņa, Gatis Maliks, Leonarda Kļaviņa-Ķestere, Ērika Vilisone, Eduards Johansons, Januss Johansons, Kate Oliņa

Producers: Alise Rogule, Roberts Vinovskis

Associate producer: Alise Zariņa

Produced by Mima Films

Ieva Segliņa plays the leading character Liv.

STARTING a Movement

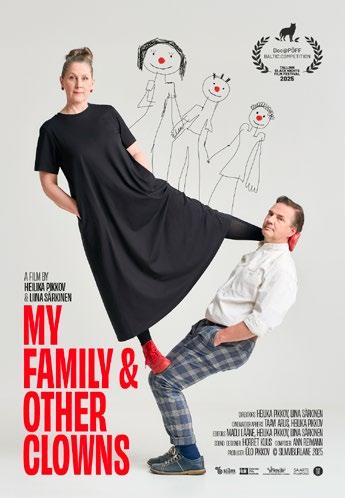

Director Eeva Mägi, premiering

her film Mo

Papa at PÖFF’s Critics’ Picks programme, talks about Estonia’s answer to the famous Dogma movement.

By Andrei Liimets Photos by Sohvi Viik-Kalluste

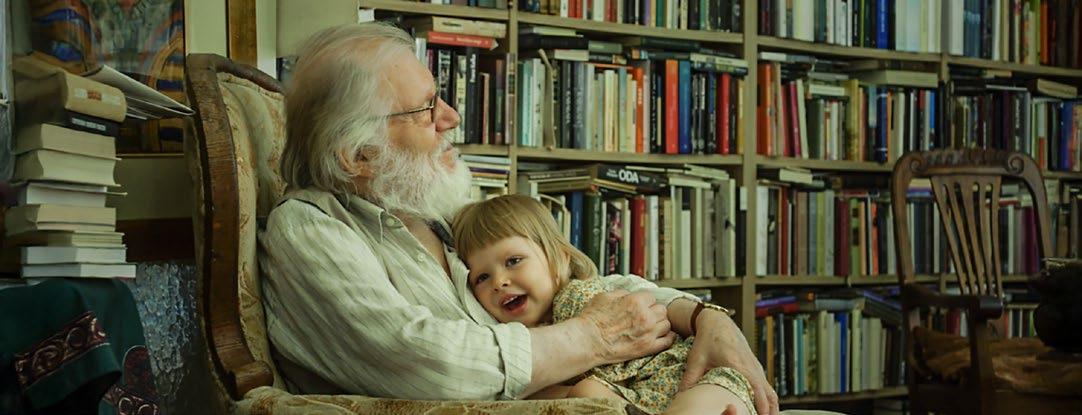

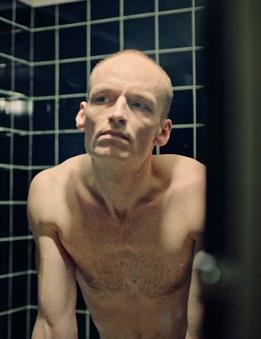

Your previous film Mo Mamma was a very personal story, based on your own relationships with your mother and grandmother. Mo Papa, apart from the generational themes, has little in common with its predecessor. Where does the story stem from?

Mo Papa doesn’t have the same kind of personal background — it’s not about my father or family relationships. With Mo Mamma, the idea of a trilogy emerged — a series of differently made films, from which the Mo movement has now grown. I started planning an experimental film and was reading about Ancient Greek mythology, Kronos and Uranus — the father killing his sons out of fear they would kill him. That led me to look into different cases in Estonia where either a father had killed a son or a son had killed his father. I found an article about a boy who had killed his father “because of poor upbringing.”

I started researching why things like this happen — spoke with a police investigator, an acquaintance from the prosecutor’s office. It’s easy to condemn in such situations, but very difficult to understand what’s really going on. That’s how I arrived at the story of Mo Papa, where a convicted person is stuck in a cycle of trauma he can’t escape. Things just keep happening, and it seems easier for society to simply eliminate someone like that.

A key aspect of the Mo movement is that nothing is written down — that gives the freedom for the story to grow organically. I heard a story from an acquaintance: his mafia-connected father was killed, his mother committed suicide, and eventually, a major mafia figure raised him — carrying the guilt until his death, believing it was all his fault. That led to the creation of the character Eugen — someone who was placed in an orphanage at a young age to later discover he has a

brother, feels like he missed out on something, longs for understanding and love, but ends up doing something very reckless.

We visited the Tallinn prison multiple times with lead actor Jarmo Reha. I was afraid the story would be too grim, too unrealistic. But to them, it felt very believable. We started adding more, because in that trauma cycle, things just keep piling on. For example, you attack someone in prison because you don’t know how else to express your emotions — you don’t know any other way.

Jarmo lived in the character the entire time. He only had a basic phone, let us film in his home, did the kinds of odd jobs Eugen does in the film — at a moving company, shovelling snow, working at a funeral home. It’s common to get out of prison and have nowhere to live or work. You start from zero. It’s a very difficult return.

In the film, the titular papa ends up fading into the background. Was that the original plan?

I wanted to intertwine different stories. I’ve heard many times about fathers walking past their children on the street, not speaking to them. Often there’s no great tragedy involved — they just don’t take any responsibility. I don’t know why, but there are many fathers locked in their own lives and mindset that nothing can change. They just coast through life without taking responsibility for their children or seeking resolution — even though everyone is hurting.

At the same time, you don’t portray the father as a cartoonish villain. He is just passive.

I don’t think he’s bad. It’s unfortunately typical in such cases — fathers who just can’t look their children in the eye.

DIRECTOR

You have a background in law and have seen the justice system up close. How much do you believe prisons rehabilitate people?

I don’t think they rehabilitate at all. Imprisonment should be used less, because it doesn’t change anything. Of course, there are some people who are extremely violent or maniacal and need to be separated from society, but most problems start elsewhere. We should be solving those problems and helping people — not locking them up. Thankfully, more services are being offered now. But people still love the idea of punishment — the first reaction is always to send the guilty to prison. Unfortunately, that doesn’t change anything.

What does Eugen lack the most? Is it family support or help from the state?

Everything starts with family. He was given away — his parents didn’t raise him. Missing out on parental love is incredibly hard to compensate for, even if orphanages do good work. Some kids come out of the system and manage fine, but Eugen is trapped in this trauma cycle. No one wants to give you unconditional love unless you’re family. That creates a loop of selfblame and hatred. You constantly feel the lack of something. That’s when irrational behaviour starts — you take out your need for love on others, replicate the same behaviours. It pulls you into a strong centrifuge that’s very hard to escape. But you can, if you’re surrounded by understanding.

To me, the most beautiful line in the film is when Stina asks, “What’s the most beautiful thing someone’s said to you?” and Eugen replies, “That it’s not your fault.” It’s very hard to be freed from guilt — even prison officers told us that the media tends to label ex-prisoners, writes stories about how things aren’t safe anymore after someone is released.

There’s a scene between Eugen and Stina involving a bug that crawls on a shoulder. Was that improvised?

Completely random! Often, we start filming knowing the situation, but not what will happen. Sometimes we

MO PAPA

Drama, 88 min

Director: Eeva Mägi

Cinematographer: Sten-Johan Lill

Cast: Jarmo Reha, Rednar Annus, Ester Kuntu, Paul Abiline

Editor: Jette-Krõõt Keedus

Sound Designer and Composer: Tanel Kadalipp

Production Designer: Allan Appelberg

Costume Designer: Ulvi Tiit

Make up Designer: Liisi Põllumaa

Producer: Sten-Johan Lill, Eeva Mägi

Produced by Kinosaurus Film

search for half an hour, saying lines, and then suddenly something clicks — the whole crew knows immediately that something is happening. That’s the divine creative impulse — you can’t force it. You have to wait through the chaos and not interfere, even though it’s tempting. Directors fear chaos, but I think the best moments come when you don’t know exactly what you’re doing and let it unfold.

In that scene, a spider fell on the actor, and everyone immediately knew what to do.

methods.

You’re almost like a documentarian of fiction. Interestingly, when it comes to documentaries, I’m the opposite — I can’t just observe. I always think: nothing happens by chance.

Mo Papa was filmed with a small crew on real locations using guerrilla-style

Mo Papa rests heavily on Jarmo Reha’s shoulders. Why did you choose him for the role?

He’s a friend, and it all just happened naturally. We were sitting in a wine bar in early December, had just received a rejection on a funding application, and suddenly this film idea started rolling. I had no doubt who should play the lead — he was perfect for it. And the method suits him. Going forward, I’d like to make films without fixed roles like director, cinematographer, or production designer — instead, everyone is a co-author. We go wherever the road takes us. It’s a big collective creation. I’m so grateful to them — we had no money; this was made with very few resources.

Mo Mamma was also born out of a rejected funding application and was made on a small budget. For some, that would be discouraging, but for you, it’s become a series. How so?

It started with Mo Mamma, then came the idea for Mo Papa, then the trilogy, and now it’s become a movement. Mo Amor is finished, and Mo Hunt has been filmed. Life itself is the driving force — I haven’t set limits, just let creativity flow. For a long time, I was haunted by Werewolf, a film that didn’t get funding. Now I’m grateful for every rejection — otherwise, I might be sitting in some big production company waiting around. It’s so easy to get sucked into the machinery that pulls you away from the creative core. Every change needs approval from so many people. You start thinking that there’s no other way. I don’t even know who’s on set for big films anymore — our team is so small.

Sounds like an Estonian Dogma 95. What is the Mo movement all about?

It’s similar in some ways. This year in Cannes, young Danish filmmakers launched Dogma 25 — a counter-movement to large, expensive, long-development projects that often don’t justify the cost. I wouldn’t say

You do have an exceptionally talented cinematographer.

Sten-Johan Lill is amazingly talented, and his ability to manage in scarce conditions is impressive. The key is in that scarcity. I’m thinking about writing a Mo Manifesto. We don’t have a written script, but that doesn’t mean there’s no script. Written isn’t the only form — a script can be an idea that grows. I always have the story in my head. The more organically it grows, the stronger it becomes. If I write something down, it gets stuck there — and I start approaching it differently. Generally, we also don’t use makeup, although the hairstyle in Mo Papa was done by Liisi Põllumaa.

This approach also limits the kinds of stories you can tell. Period dramas or sci-fi would be difficult unless you go completely abstract.

True. None of us have assistants. Everyone is responsible for their own field. The expectation is that everyone on set watches the monitor. We review all the footage together every night. We don’t have long project-based development. The way funding is given to films has become kind of terrifying. These massive applications, psychological analyses of characters — it pulls you away from creativity.

Directors fear chaos, but I think the best moments come when you don’t know exactly what you’re doing and let it unfold .

Mo Papa rests heavily on Jarmo Reha’s shoulders.

Mo Papa looks much worse than a 2-million-euro film. Our budget ended up being 80,000.

DIRECTOR

You said that limitations have propelled you for ward. Would you even want to work with a bigger budget?

It’s not so much that limitations have propelled me forward — it’s the rejections. I haven’t tried to align myself with the funding criteria; I’ve let the creative process flow freely. Of course, I’d like to have some money, but I actually think that current budgets — and now all the producers will probably hate me — are too big. You can make things more cheaply; the whole machinery around production is too large and unnecessary. It would be better to give smaller sums to more films.

But on the other hand, directors often live hand to mouth. From that perspective, it seems there isn’t enough money in film. Yes, because those big budgets don’t reach the cre ative core. Directors still get very little. The mas sive production machine eats it all up. The equip ment is very expensive, and it comes with a huge crew. We, on the other hand, always film using natural light.

Even Netflix and streaming platforms orig inally came with the idea that Hollywood is wasteful and films can be made more cheaply. But in reality, the technical quality has dropped, the films often look the same, flagship productions still have huge bud gets, and there hasn’t really been a new level of quality or huge public interest. Doing things differently is also extremely uncomfortable. For example, with Mo Papa we shot outdoors in –26°C. We had to take breaks because Sten-Johan couldn’t pull the focus anymore — his hands were too cold. On a regular set, there would be a heated trailer and so on. A typical New Year’s Eve fireworks shot would be planned — they’d blow everything up just for the film, and stage a big crowd scene. We just decided to shoot, instead of partying, on New Year’s Eve. We were in the right place at the right time. All the locations are real, and we use guerrilla methods. As the saying

goes: it’s easier to ask for forgiveness afterwards than to ask for permission beforehand. (laughs — AL)

What’s next for the Mo movement? Two films are already in the can. Is there a common thread between them?

They’re all completely different. We’re currently Mo Amor. It’s a fairy tale, a chamber drama about a trans man who has kept it secret from his exes and invites them to a summer house to come out and ask for forgiveis about a theatre director and a burned-out ballerina — a story of suppressing pain, but also of finding meaning through it. was generally well received but reached very few viewers at the domestic box office. The themes you describe now might be even more difficult for audiences. How much do you think about your audience — or are you more focused on festivals?

I think a lot about the audience. I always have an abstract viewer in mind. I don’t believe in dividing films into “festival films” and then “light entertainment” that people enjoy. You have to reach your audience. Wider marketing would require a budget — and we don’t have that. But I could resonate BF

EEVA MÄGI is an Estonian writer and director working in both fiction and documentaries. Her shorts Lem(2017) and The Weight of All the Beauty (2019) received international recognition, with the latter being longlisted for the Oscars. Her debut feature (2023) garnered a jury mention at the Tallinn Black Nights Film Festival. Mägi has received several awards, including the Estonian Cultural Endowment’s Young Filmmaker Award. Mo Papa (2024) is her second feature.

Mo Hunt, the fourth film of Momovement was shot this summer.

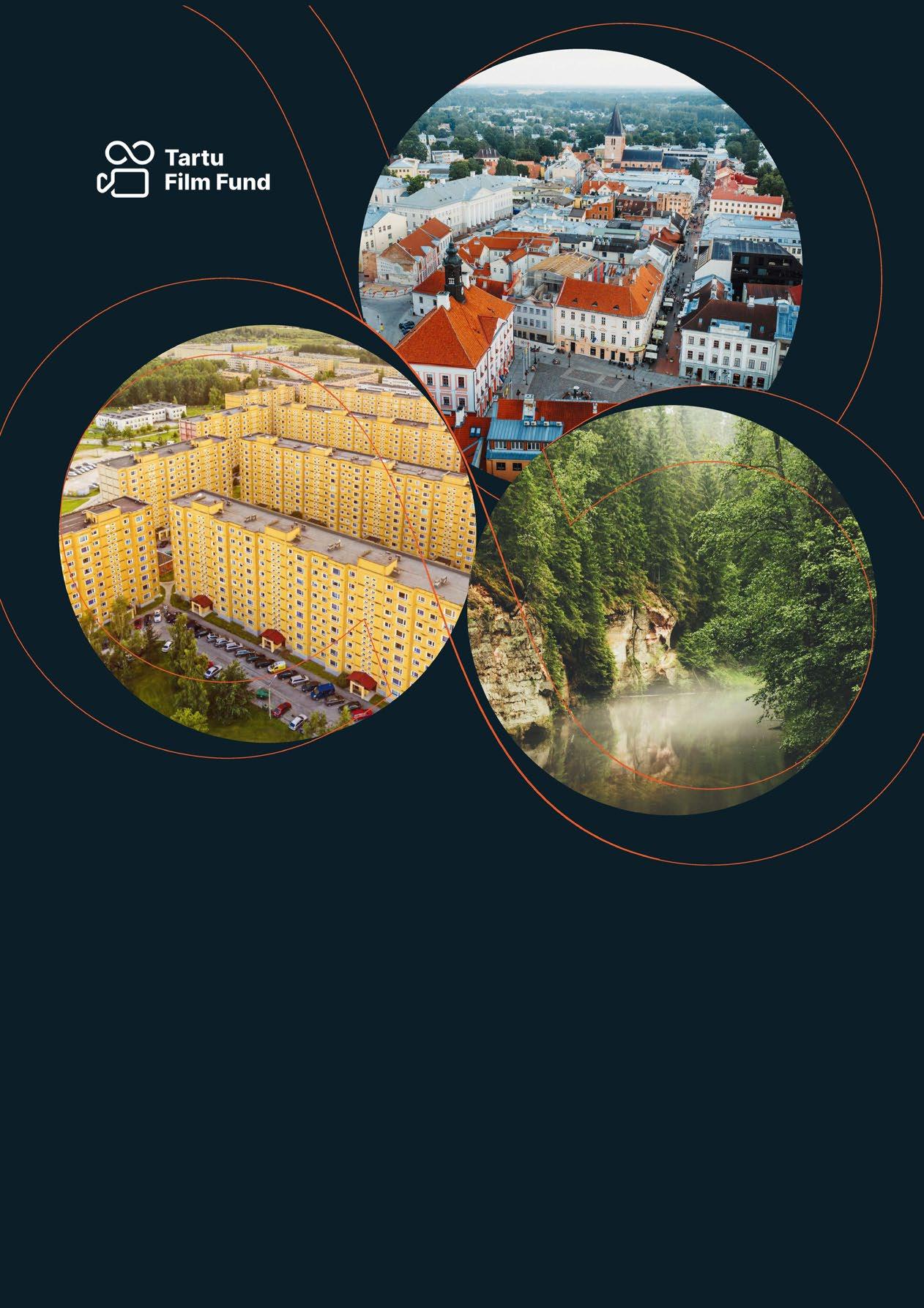

IDA HUB

EMERGING HOTSPOT FOR BOLD FILM INNOVATION AND PRODUCTION

In northeastern Estonia, Ida-Viru County is quietly reinventing itself - transforming from an industrial heartland into one of the Baltic region’s most intriguing creative frontiers.

By Teet Kuusmik

At the center of this transformation stand two key forces: the Viru Film Fund and the IDA Hub Film and Multimedia Innovation Centre. Together, they form the backbone of a creative ecosystem that combines funding, infrastructure, and innovation.

The Viru Film Fund, managed by the Ida-Viru Enterprise Centre (IVEK), offers up to 40% cash rebates for productions filmed in the region. With no artistic restrictions and no minimum spend, it has earned a reputation as one of the most flexible and filmmaker-friendly incentive schemes in Northern Europe. This approach has already attracted international productions such as The Agency and The Swedish Torpedo, while supporting homegrown titles like Mud on

FUNDS

Your Face (Taska Film) and At Your Service (Stellar Film).

The rare concept of IDA Hub film innovation center unites a modern space for film production, skilled local production support, and technology-driven startup innovation. Behind this concept stand three partners: Ida-Viru Investment Agency, Tehnopol Science and Business Park, and Ida-Viru Enterprise Center.

Ida-Viru Investment Agency (IVIA) is developing the largest studio complex in the Nordics, due for completion in early autumn 2026. The facility will feature two large sound stages, 1,200 m² and 2,000 m², alongside post-production suites, workshops, offices, and full on-site support. Designed to meet both domestic and international production standards, the complex aims to offer filmmakers a

complete, cost-efficient alternative within Northern Europe. To date, 50% of the construction work has been completed, and the construction company is moving ahead of schedule.

Film and Multimedia Accelerator, powered by Tehnopol, which offers a strong and practical journey, from hackathons and bootcamps to acceleration and growth, helping teams with bold ideas reach market readiness and attract investment. Each team is supported by a dedicated lead mentor, a seven-part training program, and access to community events and top industry experts. The accelerator focuses on early-stage tech startups developing tools for the next generation of storytelling - from XR and animation to AI-driven production and post-production innovation. To date, 11 teams have joined the accelerator, and the most promising ones will pitch their solutions on the stage of PÖFF Industry.

Ida-Viru Enterprise Centre (IVEK) runs the Film Industry Incubation Programme, a hands-on initiative for professionals and entrepreneurs looking to enter the audiovisual sector. Participants receive practical training, work with a mentor from the industry, and get guidance from a business consultant, helping them build industry connections and transition into film and TV production. The programme focuses on essential behind-the-scenes roles: from logistics and photography to hair and makeup and set construction.

Together, these initiatives are turning Ida-Viru into a full-spectrum creative region, one where stories are imagined, produced, and brought to life. Backed by the EU Just Transition Fund, this evolution represents more than cultural growth; it’s a blueprint for regional renewal, where creativity and innovation build the foundations of a more resilient future for northeastern Estonia. BF

by

Photos

IVIA Behind the Ida Hub concept stand three partners: Ida-Viru Investment Agency, Tehnopol Science and Business Park, and Ida-Viru Enterprise Center.

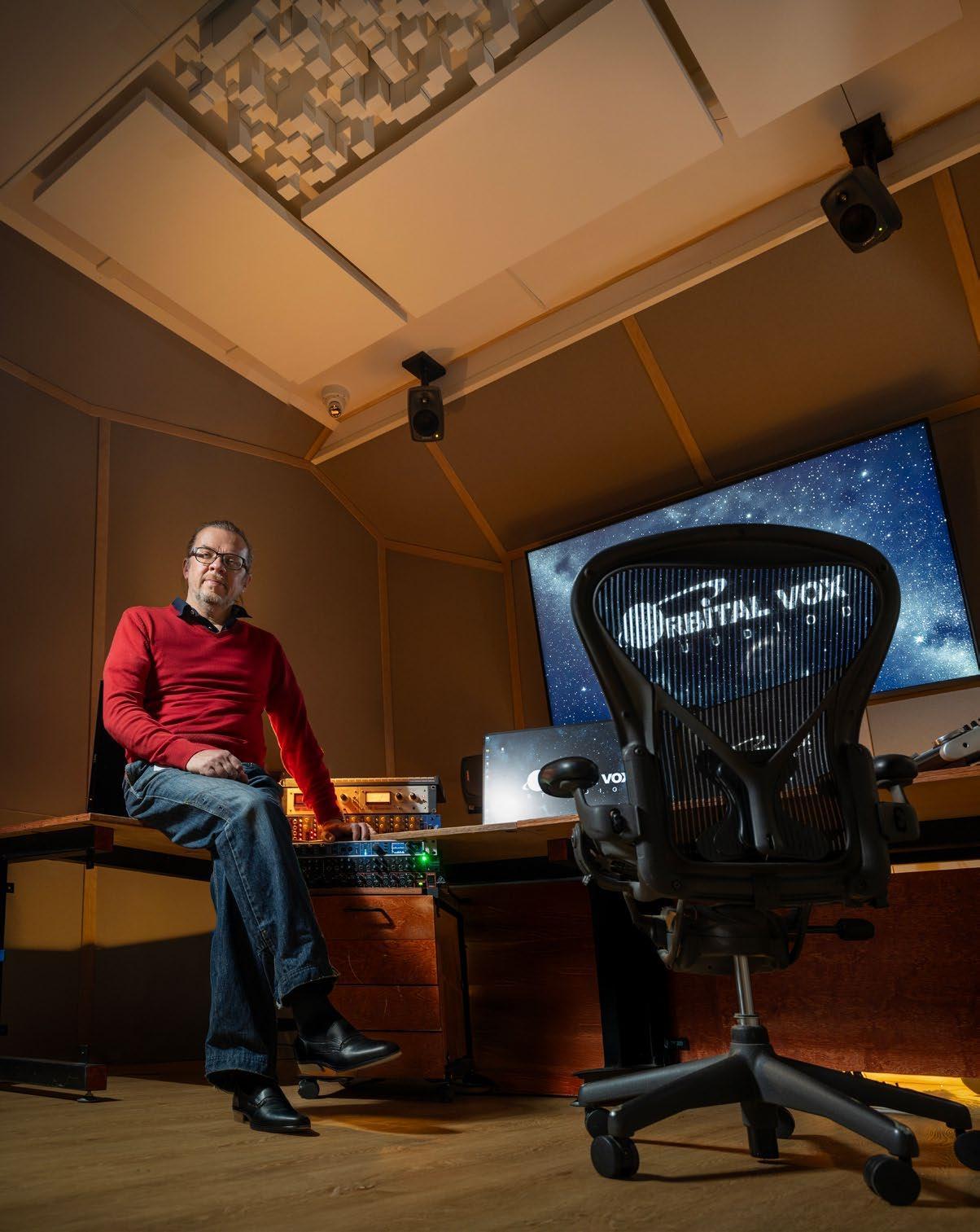

E�ERY SOUND T� LLS A STORY

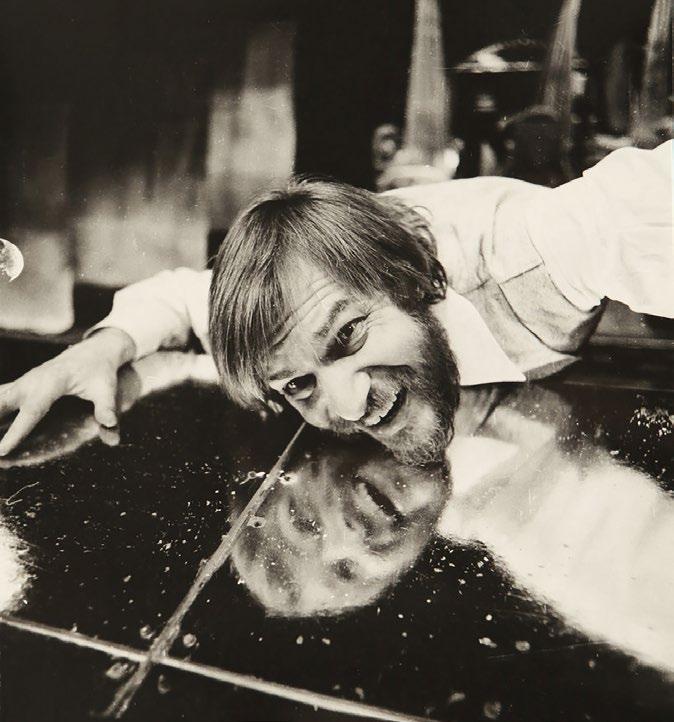

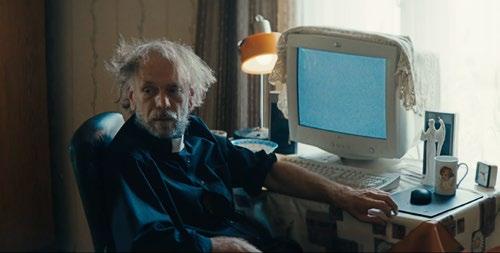

Orbital Vox Studios has been part of Estonia’s sound and post-production scene for over thirty years. What started as a small home setup has recently evolved into a new chapter – a modern studio where technology supports creativity more smoothly than before. Its founder, Uku Toomet, describes how a personal passion has developed into a lifelong project – and what motivates the team to keep moving forward.

By Eda Koppel Photos by Viktor Koshkin

How did Orbital Vox Studios begin, and how has it evolved? It started from a simple wish to record my own music. Professional studios were too expensive, and friends often weren’t happy with their recordings. I used a Soviet cassette deck, a few microphones, and a small mixer. The sound quality was rough, but the spirit was there.

Later, I got a job at Estonian Public Broadcasting, where I worked with many local artists and learned a lot about recording and mixing. At the same time, I continued working with underground musicians in my home studio. Step by step, I bought better equipment, and the studio gradually became more professional. I named it

Orbital Vox – from the band Orbital and the Latin word vox, meaning “voice.”

Today, we are a team of six plus freelancers, working on commercials, dubbing, film sound, and colour grading. I manage the studio and teach film post-production at the Baltic Film and Media School.

What have been the key milestones in Orbital Vox’s journey?

The first was moving from my bedroom to a real studio, 30 years ago. The second was working on international projects – our first was dubbing Pixar’s The Incredibles, which taught us a great deal about professional workflows. The third significant step was building our new studio based on modern standards. The new space turned out even better than we had hoped.

POST-PRODUCTION

What inspired the move to your new studio, and what makes it special?

We had long outgrown our old space, and when the building was set for demolition, we took the opportunity to move. Eventually, we found a good location in the city centre – an old print factory with thick limestone walls, ideal for acoustics. Now we have floating rooms with high ceilings, modern speakers, proper ventilation, and even a small kitchen and lounge area. All rooms are interconnected, allowing us to switch easily between recording and mixing. The studio has been built on proven professional principles, making it one of the most refined and distinctive in the region.

The design is simple and calming –natural oak, soft colours, and good lighting. It brings a sense of ease that offsets the studio’s high-tech nature.

How has the new space changed your work?

Better acoustics and a well-designed environment help improve focus, and we can now achieve the desired results much faster. The workflow has become more seamless, and the atmosphere feels more inspiring. Inside the walls, there are about 10 kilometres of cables – but ultimately, it’s the small visible details on the surface that shape the overall impression of the space.

What were the main challenges during the move?

The biggest challenge was maintaining continuous work. For some time, we op-

erated two studios simultaneously. Moving all the servers and IT systems was also a major task, but everything went smoothly thanks to careful planning and teamwork.

How does technology shape your work, and what kind of new equipment do you use in the studio?

Our film mixing room has cinema-grade speakers and a large acoustically transparent projection screen. One room follows Dolby Atmos specifications, while the others use 7.1 and 5.1 systems, enabling several projects to run simultaneously. The studios will serve us well for our own projects, but are also available for outside productions that bring their own sound engineer. The cinematic mixing room, in particular, is unique in the area and has attracted considerable interest.

Technology is essential, but it’s still only a tool. What matters most is how it supports the creative process. Our sound directors have a strong musical sense and value projects that allow artistic freedom.

The studio has always been a place where creativity and technology meet –where ideas take shape. Creativity is natural and harder to control, while the technical side can be studied and improved. Working in a studio means balancing these two worlds, even though the technical side often takes the lead.

The real goal is to understand the creator and help express their vision in a form ready for playback. The path to-

ORBITAL VOX’S STUDIOS:

A - 7.1 Cinematic Mixing

B - 5.1 Editing and Mixing

C - 7.4.2 Editing and Mixing of Immersive Sound

D - Colour Grading with 5.1 Sound Mixing

E - 5.1 Sound Editing and Mixing

MIC BOOTHS:

A - 13 m² B - 6 m² C - 6 m²

SERVICES:

Cinematic and TV Mixing

Editing, ADR, and Sound Design

Dubbing, Commercials,

Voice Talent Roster

Colour Grading

Post-Production Supervising

Cinema and TV Deliverables

ward mastery never truly ends. With good tools and smooth workflows, ideas can flow more easily into reality, leaving more time and energy for the artistic part of the work.

Which projects stand out in Orbital Vox’s history?

There have been many interesting ones –film sound design, ADR, and museum installations. We’ve worked for directors like Christopher Nolan, Ilmar Raag, Priit Pärn and many others. Each project has been a worthwhile experience.

What are your plans for the next few years?

We want to work on more films, explore new sound formats, and continue improving. The main goal is to keep learning and stay curious.

What motivates you personally?