SHAPE

Table of Contents

Yiyao Sun Birds

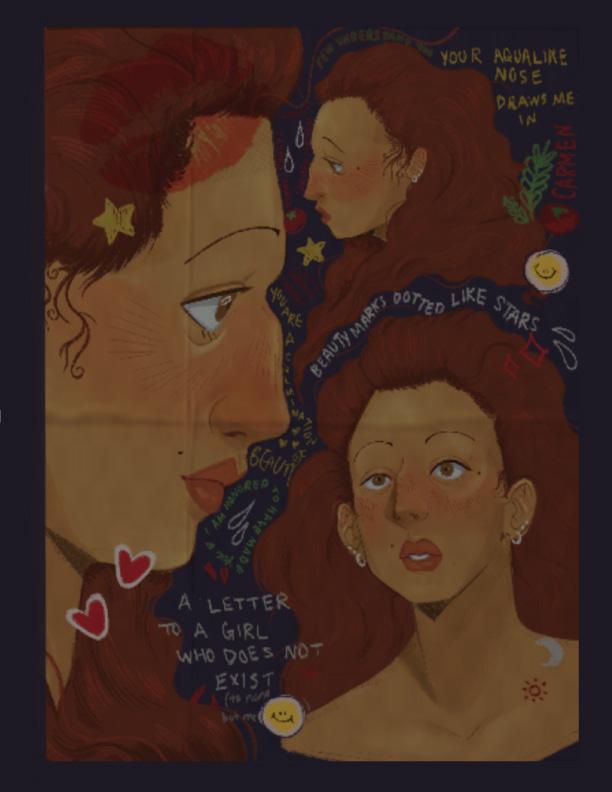

Urunna Anyanwu A Letter to a Girl Who (Does)n’t Exist

Reese Carolina Cuison Villazor ilong

Sarah Hopkins This place

Ash Campos Growing Pains

Tori Harris Water

Juan Simón Angel untitled

Kelly Hui Boots

Josh Nkhata A Nature Poem

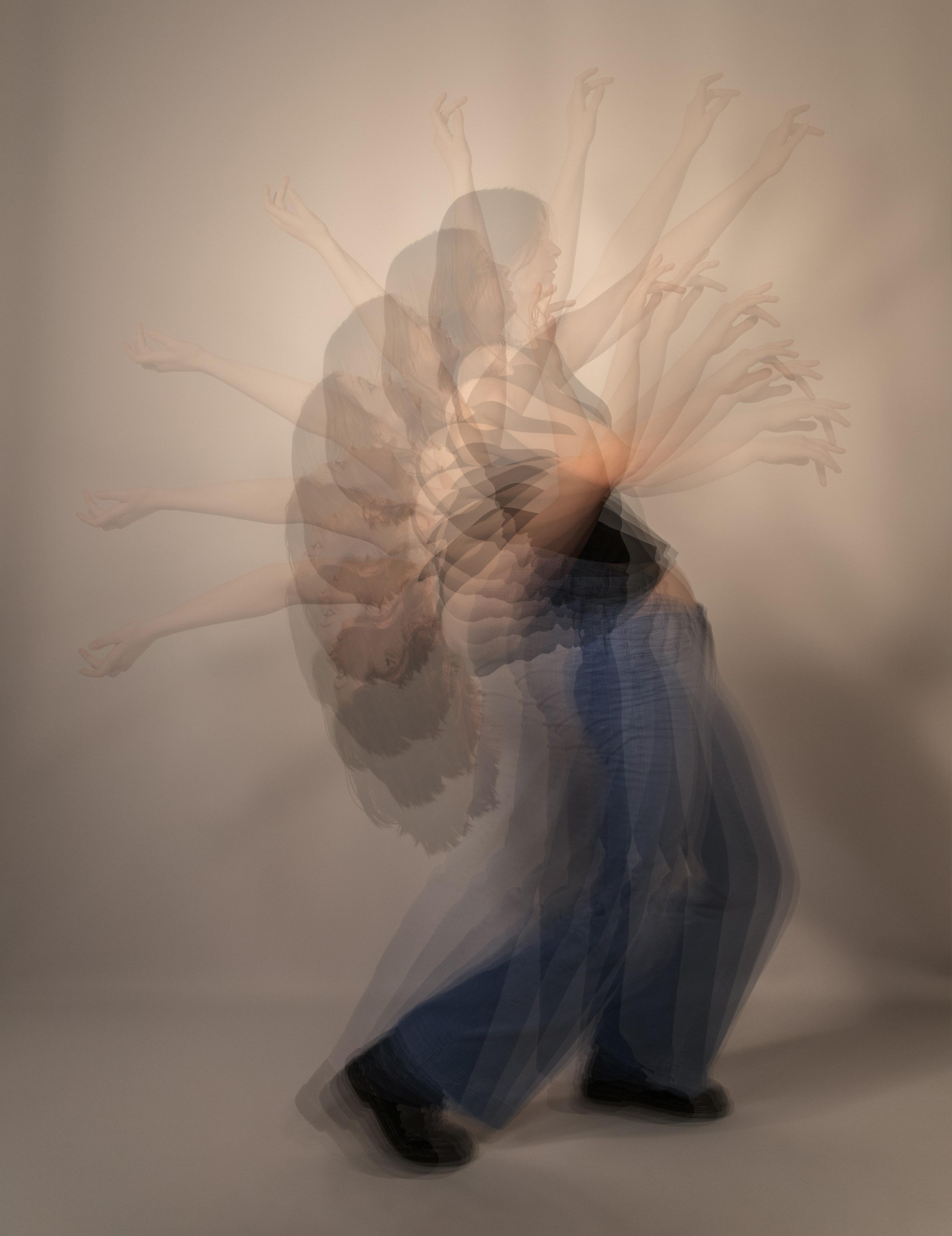

Övgü Defne Özus (dis)figure(d)

Bolanle Ogbala Presentation Pep Talk

Angele I. Yang

Grief, Basquiat, and the Night

Sandler 08_fisheye.jpg

Kate Seiter My therapist tells me

Inioluwa Aloba Pan-Africa, Borders, Personality, and Diasporic pains #1

Natalia Serrano-Chavez baptism defined

Elizabeth Li

Monica Gould, Egheosase Odiase, Melissa Bueno, Mack Minter, Darya Foroohar

EDITOR’S NOTE

Does everything have a shape?

A form, a hue, a structure that you must bend to, concede to, smush and cram yourself into? As marginalized individuals, we are often told to (or made to) conform to shapes that do not fit us. We navigate stereotypes with stiff lines and edges. As new editors, freshly handed the reigns of a space that meant so much to so many, we wanted to explore control. Who shapes who’s life? Who shapes history? But amidst our explorations of control, we found ourselves fascinated by our own shapes. Our noses and tongues. Our homelands and sexualities. The parts of us, undying, intertwined, and persistent, that bulge and recede.

Shape was suggested to the board by one of our new staff writers Ash Campos. As we worked on how to explain a theme as seemingly vague as Shape, we became even more convinced as to why this theme was important. As a student organization dedicated to platforming marginalized voices in the arts and literature, we recognize that we are a shape, formed by our alienation from mainstream culture. When we shape something, its existence is acknowledged, when it is acknowledged it is given a name and a name makes us conscious of the object. This is why saying the name of a homeland, of a shape, like Palestine, is important. As writers who reckon with language, we must, by shaping our mouths around each utterance, say the name of the Masalit people of the Darfur region, who have faced the brunt of the war in Sudan, or acknowledge how the shapes of borders drawn by Belgian colonial forces have affected the people of eastern DRC. These are all shapes that concern us as queer artists and artists of color.

We urge you to consider what shapes you intentionally create and recognize the shapes you purposefully reject. Thank you for being part of our Shape.

Sincerely,

Inioluwa Aloba and Josh NkhataBirds

by Yiyao Sun

In May, the river water swallowed the sandy beach, devouring the wooden abodes that clung to the beach

A boat emitted a feeble snoring sound, Steady, aging, and delicate

Like a ghost from another world.

The boat did not travel on the water’s surface, But beneath it, Parting the mud and sand.

The old man took out a ladder, Coarse hemp rope, and an anchor from the boat.

The water vapor made the surfaces nearly transparent. Step by step, she descended from the air to the land.

Two dogs peeked their heads over the side, Warmly and restrainedly wagging their tails.

Amidst the endless silver water and The still colossal hull,

Two tails swung like pendulums.

Cold and warm air dances,

The wind wafted from the river, Carrying the scent of fish, Entering the treetops, the land, and she approached me,

Steady, aging, and delicate

Her face gradually revealing an expression, Seeming unfamiliar with this skill.

Along the uneven slope, We walked side by side with the cargo ship. Regarding the decent of clouds and the sunset, She remained silent, Her expression gradually dimming, A habitual dimness, or boredom. Or sadness.

We didn’t discuss boredom or sadness; We talked about people leaving, Empty houses, Wood piled up on the shore, The flip of prayer books, The growth rings of cypress trees, And birds.

Birds have no age or hometown; Birds just appear In her time and mine,

Suddenly returning and disappearing again.

Urunna Anyanwu

Urunna Anyanwu

ilong

by Reese Carolina Cuison VillazorOne night as we are in bed, you run your finger over the bump in my nose and ask me where I got it from.

The word for nose in Tagalog is ilong – I have always liked the way the sound of it is echoed in my arched, elongated shape. They say the nose has the best memory out of all the other features. My lolo, the one I never met, was said to be very tall, his face containing worn lines and hard edges in an uncanny resemblance to the famous (i.e. less forgotten) author from his province. Most people will look at my face and see my mother. She looks at me and says that her father was a complicated man, a comment she directs towards my nose. In class, I trace the cover of America is in the Heart as if it is his face. They share the same weary eyes, same tired working hands, the only difference being that the author died here, waiting to go home, and my lolo died there, waiting to get here. I imagine my lolo caught up in that liminal space of longing, equal parts wanting and resenting the country that took his children, that raises his grandchildren with nosebleed-inducing tendencies. My body will remember all of this better than I can.

I tell you my sister broke my nose with a softball.

You laugh and fall asleep, smelling like sticky sweet drink, dreaming of someone else. Even when you are long gone, my body still remembers your straight, pretty nose pressed to my collarbone. It remembers and remembers and remembers.

This place

was built to hold my people

Entrance fee: a sunflower, a fallen whisker, a missing sock

Sunlight comes in through the paned glass because she likes making us mosaics

You slip through us (the group swaying to Billie Holiday) holding two bottles above your head

This place holds us at 72 degrees and sunny with no chance of anything grey

Everyone came in once as strangers and left with red strings

An address or directions could not help for it can be found in a curl or hiding behind piano keys

This place holds what is too precious to be under lock and key what looks like my sisters and your own

by Sarah Hopkins

Growing Pains

by Ash Campos

by Ash Campos

When I was younger, I lived in a trailer park. Across was my grandmother, next door was my cousin, and friends were scattered all over. Weekday mornings, friends and I would race each other to the bus stop and sit together. After school we’d argue whose home would be our new imaginary land. Nights, my cousin would be dropped off for playdates while our mothers worked night shifts. Weekends were spent at my grandmother’s house while my parents worked from sunrise to fall. Everyday was the same; uncalculated but expected. The sun kissed our skin, we embraced the itchy grass, and our laughter would envelop the birds, adding on to the creation of mother nature. I slept in warm colorful sheets that shrunk with age, developing a fear within me; Who’s under the bed?

Boxes full of old birthday letters, teddy bears, concert tickets, and friendship bracelets, made me curl my feet under my sheets. If I close my eyes and cover myself with the blanket, maybe they won’t get me. Maybe If I close my eyes tight enough I’ll open them to the sight of abuelita. Or maybe I’ll wake up in the trailer park, or or maybe I’ll wake up to the sound of tuning instruments. But abuelita passed away, I live in a house, and I Don’t play the cello anymore. So I’ll hang my feet off the edge of my bed, hoping for someone to save me. Maybe abuelita will respond to my tarot readings, or maybe old friends will reach out to me, maybe I can join the birds in their morning songs. Who’s on the bed?

A body too big, a blanket too small, a heart too full, and a mind so empty.

by Tori HarrisWater

These are the places that shaped me:

The Charles River, Boston. 2006.

It was cold, but my father put us in a boat, and away we went.

I watched the water twist into baritone whirlpools and velveteen eddies

That would suck me right into its treachery.

Then I looked up.

The current had carried us to a bank dressed in gleaming white and gold.

The McClure Park Pool, Tulsa. 2009.

It was hot, but my mother placed me in the water, and stepped back.

She had done all she could.

Today I learned how to swim.

The air burned my lungs, but the water soothed my worries,

As I dove down

And opened my eyes.

Watery fingers held me safe.

Fort Gibson Lake, Middle of Freaking Nowhere. 2012. It was hot, and I was sweating through my swimsuit.

But my friends held onto my arms.

I held onto their arms.

And we clung onto a raft too small for the three of us.

The water hurt to touch.

It stung any open skin it could find.

But in between sprays, it whispered hang on.

We stayed on that raft the longest out of anybody at camp.

Union Pool, Broken Arrow. 2017.

It was stifling, but my coaches looked on.

We swam from wall.

To wall.

To wall. I could do this.

The water was too hot, but I kept swimming. Everything hurt, but I kept swimming. Why am I here?

Union Pool, Broken Arrow. 2018.

It was throbbing, but my coaches looked on. We swam from wall.

To wall.

She’s not even injured. To wall.

I had nearly torn my rotator cuff last month–Of course I was injured.

To wall.

But I had never stopped swimming. The water was still too hot.

Booker T. Washington Pool, Tulsa. 2018.

It was sweltering, but wasn’t it always these days?

I bit back my tears. Shifted on my crutches.

Don’t worry. Just focus on getting better. I avoided the pool the rest of the season.

Booker T. Washington Pool, Tulsa. 2019. It was warm, and I couldn’t stop laughing. The water gurgled happily between me and my new teammates. Red water ran clear

Providence River, Providence. 2021.

It was sickening, but my dad stayed with me through it all. I told him everything Through watery gasps and tears. Can she even swim?

I heard Black people can’t swim. My dad is a force of nature.

That day, he was unnaturally still.

Good fucking riddance. The river agreed.

Oologah Pool, Oologah. 2022.

It was just right, and everything felt perfect.

I felt my relay’s arms around me.

The record laid shattered at our feet.

I was dripping wet in the worst pool in the state

Half the team was out with Covid

And I couldn’t stop smiling.

Whoever said water has no shape Has clearly never been To the water.

Shape has always eluded me. In return, I too have decided to elude it, to scuff at its parameters, to wage war on its demands. Because shape is a thing that has long been robbed from me.

I mean it literally, too. An established repertoire of forms I’m allowed to inhabit, of ways that I’m permitted to shave, and starve, and bleach my way into. A “precurated” set of existential outfits I can wear and be smiled at and complimented on and thanked for- an expected sensibility for the way I take up space in the world. Why rebel and argue, when it’s so much more simple to fit in and smile? Because it’s all so painfully ironic.

Ironic in that it’s the same closet that I’m shoved into- for being too foreign, too brown, too femme, too queer, too bold- that they themselves are trapped in. All desperately clawing at their necks as the realities of their lives begin to set in. Nevermind how poorly their limited shapes fit me, see how meager and feeble it leaves them. A systemic impoverishment of their social, intellectual, emotional, cultural… understandings of life. It’s ironic because in the end I am robbed as much of my shape as they are of theirs. We all lose the same richness from our experiences, the same vivacity from the colors that fill us, the same sense of fulfillment and peace from our existence. Because the issue is our imaginations, how they have shrunk ever so small so that the possibilities of our existence have dwindled to only a few sad shells of what we could be as a species.

And it’s not about what they see of themselves in us, though that plays a role in it, but so much more about what they don’t. They hate, they crush, they attack, because they see all that they lack. All the possibilities that they could never muster for themselves. And they see it in people like me. So for me to exist is to live a cruelness incessantly — it’s to perpetually translate my beauty into a language so simple, so coarse it nearly defeats the point of the exercise. But the point remains, that each and every time I, a proud and radiant queer brown immigrant, strut right through the smallness of their lives, I hope that they see me. I hope they desire me. I hope they scuff and spit. I hope they understand I’m every bit of their reflection as the world is a reflection of me. Eclectic and complicated and without shape.

So everytime you see me in public, smile. Smile because I do too. Because shape has decided to elude me, to unrestrain the flow of my existence, to free me.

I eluded shape because it never served me, nerve served the richness or fullness of what and who I am, never encompassed me. But that won’t matter to me, not anymore.

by Juan Simón Angel

Boots

After his diagnosis, I found my father in the wetlands where we used to walk with too-big boots borrowed from the neighbors. I would follow him, plaintive squelch under my feet, to where fish lay still under a snow sunk lake and the peat ate rot like it knew mercy. My father’s face, even in the wind, like the season’s Asian pear: white, hard, fat.

Through sodden uncut switchgrass, we found a trickle of stream carrying cold water down the way. And what was it for? Who would carry my father’s thwarted body home?

by Kelly Hui

A Nature Poem

I sought out this thaw due to my pre-natal love of mud. I come to sink and this maple indulges and joins me. I unfurl,

“If you, friend, rested a spile in my belly button I too would seep.

As though you were my lover after loving.

As though the bubbling over was release.

As if the contortion was ruse and the burden sunk deeper now. Tap my tough brown.

Watch me leak tender.”

I am the one man unburdened but burled, but behind, a voice, with the rasp of a lit fuse speaks,

“You know no one likes that shit, right?

That nothin’ talk bout nothin’ in particular. The only time for having smoke blown up your ass is when there’s a beehive up your colon.”

A small gray rabbit stands upright, his fur twisted into tight cornrows and a large blunt held loosely in the corner of his lips.

“So many fucking boring-ass nature poems.

I got a 9-year lifespan from emergence to reentry

You think I want to spend it hearing about some fucking tree?

And from you, man? What you doin’ out here?

Ain’t there some dead brother out there for you to write about?

Heard a cop shot a 12-year-old the other day and your ass is out here writing about this musty-ass tree.”

I don’t oft take gab from big-toothed prophets.

“I was going to bend it till circle but keep it firm and pretty. I was going to warble and in the wobble there it would be.

Don’t eyes spin like geocentric models of the universe?

Don’t you see, friend? I am not the talker who disrobes himself at breakfast. You must peel me open. For my dignity! For meaning!”

by Josh Nkhata“If you mean something then do it.

A light-skinned motherfucker was here last week writing bout some nightingale. Kept on saying his poem was about death or something. So you know what I did? I handed him semi-automatic. I told him to shoot it.

How do you write a poem about death where nothing dies? The more blood the easier it slides down your gullet. When he said ‘no’, I paid the fox twenty shillings to eat his bird in front of him. Learned him real good.”

“It is the flux’s essence that eludes you. Poetry is the fervor of the stroll. It must drip out slowly from your gut.”

“They musta got you deep in the brain out there! They domesticated your ass!

Don’t you remember? Goddamn! Give a brother a cookie and he won’t even remember he harvested the grain for 2 dozen. For us, poetry squirts and spews. Are you gonna make me prove it?”

I stare at him unspeaking, realizing rabbits aren’t supposed to talk, only mumble. He picks up a stick and gnaws it to a sharp point. He hops to a branch in the maple before driving the stake through his body. Staggering, he pulls it out and stumbles forward.

“OH GOD! YES! FUCK! FINALLY! YES!

I AM PUNCTURED BUT YOU ARE FILLED!

I AM PUNCTURED BUT YOU, yes you, ARE FILLED! FINALLY! FINALLY! A GOOD NATURE POEM! WRITE ME DOWN! WRITE ME DOWN, MOMMA!

PRAISE THE BLACK GOD! PRAISE THE DURAG! PRAISE THE CHOKEHOLD! PRAISE THE BAOBAB TREE!”

I watch him empty. He spews first but then he drips. Gush then trickle. Downpour then dew. Perhaps, I have interlaced my fingers in between another man’s toes. Perhaps, my tongue has pruned from the wetness of my mouth. He watches me empty.

Övgü Defne Özus

Presentation

Pep Talk

by Bolanle OgbaraI am sizzling with electricity, I am riddled with anxiety. The floor is both below and above me, I am suspended but I am falling. You say I am fine, I cannot believe you. I can taste my pulse, my stomach was left behind when I dropped, I cannot feel my center or my extremities.

You again insist that I am fine, and I Unravel.

My skin untethers itself from my muscle, my muscles tear, and my organs escape. Stuffing spills from my abdomen, my teeth become a snapped string of pearls. My hair is a disintegrating fan of feathers. My spine fossilizes and crystallizes into quartz and shatters into pretty pink shards. Memories shake out of my ripping seams, my thoughts become a fine mist in the thick air. (You can’t see it because I am fine).

Eventually, my stripped skeleton crashes into the blistering ground. My blood bubbles and oozes. The rest of me (I think it must be me) Splatters and fizzes and hisses in the puddle around me. Slowly, I reform. Memories rub into my mending seams, thoughts condense into a stream, my spine melts together and hardens, the plumage returns to hair, the pearls become teeth, organs are confined to the knitting muscle, and my skin finishes its last stitch.

I am changed. Something is new or old or not quite right or rearranged or missing. You can see this change when I scrape myself off the ground. You approve. See, fine. You offer your stern hand.

My knees knock when I stand on my own, my lungs whistle when I breathe, my shaking shoulders vibrate in tune to my grinding joints. I gasp. You are already walking away, because I am fine.

I know I cannot take another fall. Still, I walk to the podium, and ignore the static picking at my hair.

by Angele I. Yang

by Angele I. Yang

Grief, Basquiat, and the Night Sky

Fig. 1. JEAN-MICHEL BASQUIAT, BACK OF THE NECK, 1983, SILKSCREEN WITH HAND PAINTING.

Fig. 1. JEAN-MICHEL BASQUIAT, BACK OF THE NECK, 1983, SILKSCREEN WITH HAND PAINTING.

For my father,

楊明, Ming Yang, MD, MBAIt was sometime in the hazy California summers of the 2000s, early 2010’s that my dad and I would rent a tandem bike and ride it along Shoreline Lake. But we ran into the same conundrum every time. We could never seem to find a helmet that fit him. Instead it would sit on top, like this:

Fig. 2.

“Now that’s what happens when you have a big brain like mine.” I’d watch him laugh as he clipped mine on. It’s what I’d watch bobbing up and down while pedaling behind blissfully, my dad leading the way. And it’s what I’d watch make its way back to me eight years later sometime during the two weeks between the day my dad was carried away unconscious from a stroke, vomit dribbling down his neck, and the day his heart stopped while doctors were discussing organ donation.

My dad once told me I was the one person he could exchange his big ideas with. When his doctors were explaining that younger stroke patients counterintuitively have lower chances of survival, I asked to see his CT scans. Despite its uncanny asymmetry from the swelling, I found a strange peace in seeing his brain.

When he was 7-years-old, Jean-Michel Basquiat was in the hospital recuperating from a car accident. This was when his mother brought him a copy of Gray’s Anatomy, a text that would forever influence his artworks. In his painting Back of the Neck (1983), Basquiat depicts an X-ray of a faceless black man (see fig. 1). Dominating the undercurrent of anatomic accuracy is Basquiat’s creative flair. Deeply saturated colors and splatters of paint dot the canvas, capturing the fragmented experience of a black man living in America.

When they tell you, “There’s nothing more you could’ve done,” you know that simply isn’t true. You make a list of everything leading up to your father’s death that you could’ve prevented if it weren’t for the doctors’ incompetence, his body’s incompetence, your incompetence. You are reminded of how grotesque the human body really is, the same one you grew up so fascinated by.

Mostly, though, I think I was angry that he was taken from me without any warning.

Six months later, I found myself in Korea in the middle of my gap year staying with my grandparents. Korea was supposed to be perfect. I was going to be immersing myself in a foreign country, reconnecting with family, taking college classes at a local university—the idea of a productive gap year I’d always wanted. I was finally doing something right. It wasn’t until four months in that I admitted to myself that things were not going to plan.

And it wasn’t anyone’s fault in particular. My reasons for going to Korea were all things I would’ve very much enjoyed individually. But its combination with the unexpected passing of my father turned it into a nightmarish alternate reality: I was surrounded by loving family, but unable to communicate the immovable weight of my grief in a country with language barriers and different cultural values when it came to mourning. I grew resentful of the reclusive person I’d become, yet stalwart in keeping my word and finishing what I’d started. It would be a long time before I realized I wasn’t being kind to myself.

loneliness or solitude?

the question that would follow me during long winter nights in Korea spent

in the dark, incorporeal, wandering a liminal space reading Sally Rooney’s books and between Seoul and Dublin listening to Conan O’Brien’s podcast

as I was being whisked away by Sally Rooney’s stories i found myself drawn to the idea of creating, producing instead of only consuming.

and what is the rawest form of creation if not the recreation of oneself, the unlearning and relearning of values?

How can I begin to capture my dad’s spirit when he was larger than life?

Stumbling onto a Basquiat exhibit months later in Seoul was like walking into the inside of my brain. Basquiat understood the enigmatic beauty I saw in the human body and in seeing my father’s brain. He gave me the beginning of an answer.

Flanked by blood and bones lies the black man’s spine, crowned, dripping in gold. Even amongst the gore, Basquiat looks to the fallen man with pride.

The figure offers redemption despite his suffering.

If you were to enter the bedroom at the end of the hallway of the apartment on the 17th floor belonging to the two most wonderful grandparents in Seoul, you’d find a little girl standing at the open window, gazing up at the wintry night sky, searching into its deepest blue. And if you were to follow her gaze, next to that speckle of a star, you’d find her father, smiling down at her, with all the pride in the world.

Fig. 3

Fig. 3

in my dreams of the future, I sit across from border security at the Shiraz International Airport

Has your atlas been corrected. How many died

In the fire. Will you step this way.

In our language, your family name means fortunate Did you know this already Is it true.

Are you a revolutionist. Does your luggage contain contraband items. Did you have a nice trip. What did you dream of as you flew Over us.

In what life do you come here. In what life do you bury him in white Shrouded, like a pomegranate seed divested from flesh. Does this mean anything to you.

Who started our wars. How many died to finish them. Would you consider them martyrs, Or just unlucky.

At night, what color are your eyes. What does it mean when a woman suffers. Are you happy to be here.

Did he tell you what it was like? Did you need an interpreter. When he left, did he kiss the earth

As if on pilgrimage.

Did the cormorants peck away

The salt

From his regretful wounds.

Did he watch the bombs sow our earth with the dead

Were they his

The bombs or the dead?

by Lekha Masoudi

Teddy Sandler

Teddy Sandler

My therapist tells me

to masturbate.

She says it will help me sleep. Quiet my mind, relax my body.

“What?” I ask her.

“Masturbate,” she repeats, smiling.

I don’t like her smile. Too many teeth, too thin lips. Her eyes are never really focused. But I laugh it off, wave my hands around, change the topic. I ask her a question that I know will trigger a story. She likes to talk about herself more than she likes to talk about me.

When I leave, she tells me she’s worried about me. But she says it happily, a giggle lacing her words, like an inside joke.

“Don’t do anything, okay?” She makes me promise, and I do. “Try masturbating instead!”

That night, when I’m in bed, alone, I can’t fall asleep.

My head hurts. My mind sinks deep down inside of me. My body feels too big, too heavy. It aches, and I feel sick. Voices whisper and laugh and yell behind my forehead, around my ears. I want it to stop. I want nothingness. I want to sleep. So I masturbate.

I reach into the drawer of my bedside table, quiet and coquettish, and pull out my pill bottle.

I trace it scandalously before twisting off the cap. I shudder when it pops open.

My hands shake as I pour the pills into my cupped fingers and lay them in the space between my knees. I begin to count, one by one.

Twenty-eight pills. I count again.

Twenty-eight pills.

My breath picks up, and my skin feels hot. An eagerness spreads through me, an excitement. I gather the twenty-eight pills and I take them into my mouth. They taste bitter. They taste of color—like the odd salmony pink they are.

I’m not supposed to taste these pills.

But I’m dancing on a tightrope, pushing myself closer and closer to the edge every second the pills remain in my mouth.

Muscles draw tighter and tighter. Breath comes faster and faster. I’m shivering. I’m panting. The pills are turning mushy—gushing, wet

My body burns with anticipation: just a bit more; do it, swallow the pills. They’ll put me to sleep. And I’ll never have to wake.

The thought brings me to the precipice. I’m going to—just a bit more—and I’ll—!

Orgasm

I hear footsteps down the hall, and the feeling’s gone.

I cough, sputter, choke. I spit out the pills onto my sheets, now a sticky, congealed salmony pink.

I’m frozen-–listening, listening, listening

Someone went to the bathroom. I hear them shuffling around. Soon the toilet flushes and feet pad back down the hall.

I feel each step in the pit of my stomach. It makes my sweaty skin cool, and my cheeks burn hot.

I feel something heavy behind my head. A presence. A guilt.

Silently, trembling, I scoop the mush of pills back into their bottle. I twist the cap back on, and I slip the bottle back into the drawer.

I wait a bit. No more steps. The house is asleep.

I go to the bathroom, wash my hands, scrub them raw.

But then I see an old bottle of Advil by the sink.

I try again, and this time I spit the candy red mush of the seventy-three pills into the toilet. I flush it and toss the empty bottle.

And I go back to bed.

by Kate SeiterPan-Africa, Borders, Personality, and Diasporic pains #1

by Inioluwa Aloba

I often forget people are soft things

When I press my lips together they are stiff

So I forget that I am a soft thing

Full of life and blood from the clay of the earth,

Molded by a porous land

Where bodies flowed across each other like rivers,

Where stories transmuted before your ears,

But the truth of it was fixed

Where everything living was a permeable substance

But blood has birthed borders soaked deep in dirt,

Around the rivers

And diffused deep into the sea

The same deep dark earth that made me

Is in kin I know and love

And more I will never meet

We were from a mass of Earth

Now fixed with more shapes

Than just bodies

Defined by sharp and jagged lines, Hot tears bubbling and spilling over the surface,

And a couple dollar signs.

This continental illness has attached itself to me

What was once a soft malleable thing

Is now a body forced to become

Evicted from becoming

Now a constant stiff lip

if you ask me where my heart is, i’d give you a map to a mountain & tell you to turn right then left then right again then go straight down to a riverbank now take off your shoes, feel the dirt, feel the land, you’ll hear the river whisper to get into the water & now you’re obliged to visit my grave, i apologize if the water stings with sin that’s what it’s for, you know, to cleanse us of our delitos because if you ask me where my heart is i’d give you a map to a mountain & tell you to turn your eyes away from the sun when your body begins to enter the water, it’ll singe your pupils like mine when i died there, stupidly steady seizing your feet, the water will demand more of you so once you step in, stay for a while thank it for its frigid feel & whatever you do, refrain from dunking your head under so that if you ask me where my heart is, i could still give you a map to a mountain & tell you to turn your gaze unto the colony of ants that has occupied the river bank since before my death kissing gnawing crawling all over those who penetrate the dirt

defined

they protect sins from cascading out onto the land, still the river of rage, safely guarding my grave, welcoming you to dissect yourself bare, if you ask me where my heart is i’d give you a map to a mountain & tell you to turn away from the congregation when you stumble upon them singing their songs near the bank clapping away to their deity, waiting for you to submerge yourself entirely in the water & [Him] asking you to confess your crimes and to die die die sorry i didn’t warn you before but they’ll be there, they will ask everything of you, give nothing ask me where my heart is, i’ll give you a map to a mountain & tell you to turn your perspective onto the ground of the riverbank & stare until you can feel every single sin, pay your respects, always, to the brothers and sisters who have died there they like i confronted god & under the water our bodies went my veins the length of that water, i profess three times that i never go back to my grave ever but if you ask me where my heart is, i’d tell you it is in the shape of a river

by Natalia Serrano-Chavez

by Natalia Serrano-Chavez