FAMILIES BELONG TOGETHER, FAMILIES DEMAND REPAIR

FAMILIES BELONG TOGETHER, FAMILIES DEMAND REPAIR

Julia Hernandez, CUNY School of Law Family Defense Practicum

Miriam Mack, The Bronx Defenders

Erin Miles Cloud, Black Families Love and Unite

Melissa Moore, Drug Policy Alliance

Ja’Loni Owens, The Transfuturist Collective, The Ad’iyah Collective

Lisa Sangoi, Movement for Family Power

Jasmine Sankofa, Movement for Family Power

Tracy Serdjenian, Black Families Love and Unite

Bianca Shaw, Black Families Love and Unite

Lauren Wranosky, Pregnancy Justice

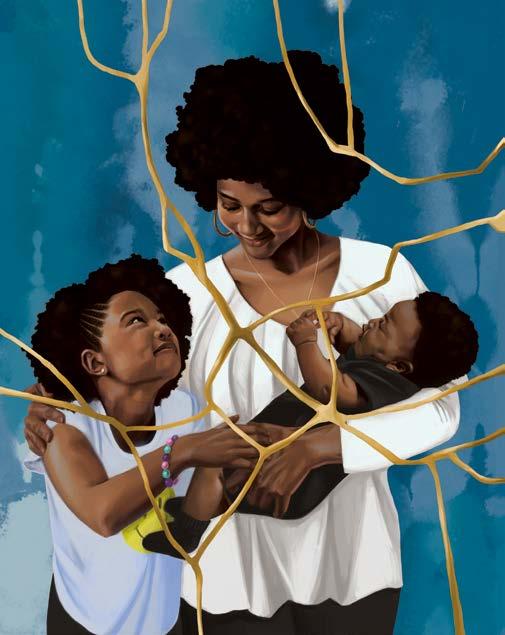

Kintsugi is a Japanese art form where broken pottery is repaired with gold, highlighting the cracks rather than hiding them. In this reparations report, kintsugi symbolizes the repair and healing of our communities by those most impacted by family policing and separation. The fractures represent the deep harms inflicted by these systems, and reparations are the gold that mends these wounds— acknowledging the damage, restoring what has been taken, and making our families whole again. Just as kintsugi transforms brokenness into something stronger and more valuable, reparations are essential to the process of repair, ensuring that healing is not just personal but collective and structural.

The first time that any of the following words appear in this Report, if they appear at all, they will appear in bold text.

The abolition of child welfare is a movement dedicated to ending the existing child welfare system and introducing alternative methods to support children, families, and communities. Advocates for abolition argue that the current system is racist, harmful, and rooted in surveillance and separation. They believe the system should be dismantled and replaced with family and community-based approaches that do not involve state-sanctioned separation of children from their parents.

Black feminism is a political and social movement that addresses the complex oppression faced by Black women in the United States and other countries. Unlike mainstream feminism, Black feminism seeks to understand the specific injustices affecting the daily lives of Black women. It is characterized by a long-standing emphasis on intersectionality—the interaction and cumulative effects of multiple forms of discrimination, including institutional racism, classism, and sexism. The intellectual framework of contemporary Black feminism is akin to womanism, which also focuses on the intersectional oppression of women of color, especially Black women. Outside the United States, Black feminism is often referred to as Afro-feminism.

The use of the phrase “Black, Indigenous, and People of Color”, or BIPOC, is intended to recenter the voices and experiences of Black and Indigenous communities in ongoing discussions about systemic racism, white supremacy, and promoting a racially equitable society.

Child Protective Services, or CPS, is one name for the locally run government agencies responsible for the foster care system; CPS is oftentimes used interchangeably with “child welfare system” despite only being one part of this system!

Any government organization or agency that is child welfare, Child Protective Services (CPS), Foster System, and services mandated by the court system or child protective services.

A word describing the gender identity of a person whose gender identity corresponds with the sex assigned to that person at birth; Not transgender.

The Foster Care-to-Prison Pipeline refers to the collaboration between policing systems to pipeline young people in foster care into jails and prisons. According to national data, over 50% of young people in foster care will have an encounter with the juvenile criminal legal system through arrest, conviction, or detention.1 Another national study revealed that 70% of young people in foster care experience at least one arrest before age 26.2 Without the support and resources to thrive, many of the young people in foster care don’t.

Mandatory Reporting refers to a legal obligation to report suspected cases of maltreatment to the relevant local authorities. Who is legally obligated to file mandatory reports is typically dependent on a person’s professional responsibilities. Some common mandated reporters include: healthcare professionals, social workers, teachers, law enforcement officials, and other professions who work closely with children, elders, and other vulnerable populations.

Inspired by “Revolutionary Mothering: Love on the Front Lines”, we use Mothers, or Revolutionary Mothering, throughout this Report to similarly acknowledge and center marginalized mothers of color as agents of transformation and lasting social and political change in our communities.

The concept of Reparations is rooted in the basic principle of making amends for wrongdoing. In the context of international law, Reparations refers to the obligation of a Government to take concrete steps to provide redress to individuals or groups experiencing deprivations of their human rights. The United Nations recognizes a five-element Reparations framework: Restitution, Satisfaction, Rehabilitation, Compensation, and Guarantees of Non-Repetition.

Reproductive Justice is a feminist framework and intersectional politic informed both by international human rights law and by Black Feminisms. The SisterSong Women of Color Collective, one of the leaders of the Reproductive Justice movement in the United States, defines Reproductive Justice as, “the human right to maintain personal bodily autonomy, have children, not have children, and parent the children we have in safe and sustainable communities.”3

A word describing the gender identity of a person whose gender identity does not correspond with the sex assigned to that person at birth; Not cisgender.

Critical Resistance defines policing as “a social relationship made up of a set of practices that are empowered by the state to enforce law and social control through the use of force.”

The origins of policing in the United States are early slave patrols, which were formed to create and maintain a system of terror that was strong enough to crush slave uprisings and to hunt, capture, and return enslaved Africans to white slave owners. It is critical to understand the foundation of policing in the United States as being the control of African descendants - both their physical location and the continued extraction of their labor.4

The word “preponderance” refers to the level of proof needed to succeed, or win, a civil court case. In whole, to prove a civil

court case by the “Preponderance of the Evidence”, means to show that a person’s civil court claim is more likely to be true than it is not to be true5, or 51% out of 100%6. Preponderance of the Evidence requires less likelihood that a claim is truthful than “Clear and Convincing Evidence” and “Beyond a Reasonable Doubt”.

Primary Traumatic Stress, or “direct trauma,” is when someone experiences a traumatic event directly as the victim or witness.

Critical Resistance uses the term “prison industrial complex” as one way “to describe the overlapping interests of government and industry that use surveillance, policing, and imprisowwnment as solutions to economic, social and political problems”. Critical Resistance also emphasizes that the role of the prison industrial complex is to maintain “the authority of people who get their power through racial, economic and other privileges.”7

Secondary Traumatic Stress refers to the stress or behaviors that happen as a result of an indirect experience of another’s direct experience with trauma.

The Statewide Central Register is the centralized database maintained by some states to collect and store records related to reports and investigations into allegations of child abuse and child neglect. The SCR is often used by city and state agencies, prospective employers, and professional licensing agencies to determine an individual’s eligibility for services, employment, a impact that individual’s ability to obtain government assistance, a stable job, or a professional license needed for their employment.

A termination of parental rights is a legal case filed by a State to permanently end the legal rights of the natural parents of a child, thereby "freeing" the child for adoption.8

When Black Families Love and Unite first embarked on the journey towards developing a Reparations framework, we were uncertain about the path ahead. Growing up, my mother often shared stories about our history, emphasizing the importance of receiving our promised “40 acres and a mule”. She highlighted the injustices faced by Black people, particularly the fact that white slave owners were compensated for the loss of their “property” (our ancestors) after the Emancipation Proclamation. This has always resonated with me. After my involvement in the child welfare system, I began to envision what Reparations would look like for me. Even in 2024, 161 years after the legal end of chattel slavery, our people are still owed Reparations, especially since the harms persist to this day.

As BLU began discussing Reparations, it became evident that everyone had different perspectives on what Reparations should entail. We all came into the system under various circumstances; for instance, I am personally affected by mandated reporting by hospitals. I believe hospitals owe an acknowledgment for the harm they’ve inflicted on Black people, particularly Black women. Additionally, the system must recognize the damage and vilification it imposes on Black families.

It’s not a coincidence that the individuals I encountered shared commonalities—we were all low-income, on Medicaid, and predominantly Black, Latinx, or people of color. This is not accidental. As Dericka Purnell notes in her book, “Becoming Abolitionist”, the carceral system isn’t broken; it functions precisely as intended. I believe the same for the child welfare system, it is not broken, it does what is intended—to separate families under the guise of child protection. This governmental harm has persisted for many years. Our group, Black Families Love and Unite, comprises individuals impacted by the child welfare system in various ways, whether as caretakers, parents or former foster children.

The family policing system, which purports to protect children, causes more harm than good. The system presents itself under the guise of protecting children, however it actually destroys family bonds and traumatizes families. Reparations are essential for us to collectively move forward. At our convening, participants expressed that while we can’t turn back time, Reparations are a critical step towards societal healing

Our journey began in August of 2023 with a webinar co-hosted with Law for Black Lives, featuring Dr. Dorothy Roberts, Dr. Tricia Stevens, attorneys at the Bronx Defenders, and the Center for Family Representation, The Real Justice Gatson, among others. We introduced the concept of Reparations and later partnered with CUNY Law’s Family Defense Practicum

to plan a convening. We chose to host a convening to hear from our community what repair looks like. We didn’t want to be the only people to create the framework, because the issue is bigger than us. It is important for those closest to the problem to find solutions. This six-hour event had 45 participants who discussed the harms of child welfare and envisioned what Reparations could look like.

The convening, rooted in restorative practices, was followed by a focus group with over 1,100 sign-ups, from which we connected with 60 individuals to delve deeper into the concept of repair and the harms of family policing. We also conducted a survey with 230 participants, gathering insights on Reparations.

Through this experience, it became clear that people are demanding Reparations. They seek acknowledgment, restitution, and genuine rehabilitation that doesn’t lead to punitive measures. As Ta-Nehisi Coates argued in his 2014 essay, The Case for Reparations,, AfricanAmericans deserve compensation for the systemic extraction of wealth and resources from their communities. Reparations are necessary for us to move forward.

In community and solidarity, Imani Worthy

Black Families Love and Unite (“BLU”) is a Black woman-led organization founded in 2021 committed to the abolition of the Family Policing System and to Reparations for all victims and survivors of the Family Policing System * BLU is proudly guided by the values of abolition and Reproductive Justice and led by victims and survivors of the Family Policing System representing diverse lived experiences and areas of expertise.

As victims and survivors of state intervention in our lives, the lives of our families, and in our communities, we use the term Family Policing System instead of Child Welfare System. We use this term because it reflects the primary function of this system—to surveil, intimidate, harass, violate, and further marginalize poor, working class, Black and brown caregivers and the children we love and care for.

At BLU, we are committed to empowering and developing the leadership of victims and survivors of the Family Policing System to: chart a pathway toward the abolition of all punitive systems intervene and put an end to cycles of State and interpersonal violence protect the integrity and honor the sanctity of our families and our communities

Steadfast in our belief that safety and support are our birthrights, BLU envisions a future where every caregiver receives the resources they need to raise children in communities free from interpersonal and structural violence. BLU believes that if and when a caregiver needs support, that caregiver should receive the support they need rather than be subjected to invasive questioning, non-consensual home searches, and persistent surveillance by CPS agents, dehumanizing family court proceedings, and experiencing their families be traumatized and torn apart. We believe that Reparations are owed to victims and survivors of the Family Policing System. We view Reparations as a critical component of collective empowerment, healing, and support.

* Throughout this Report, you will read both victim and survivor as a way to acknowledge all people directly harmed by the family policing system. This is to acknowledge that some members of our organization and the communities that our organization serves identify as victims, and others identify as survivors. Neither term is superior to the other. By using both descriptors, BLU seeks to honor the nuances surrounding the self-identification of the individuals and communities most harmed by the Family Policing System.

We want to acknowledge that this report is not the first report that attempts to define Reparations or to offer a proposal of what Reparations looks like. To contrary, BLU has learned from its movement siblings in Movement For Black Lives (“M4BL”), Movement for Family Power (“MFP”), the National Coalition of Blacks for Reparations in America (“N’COBRA”), the National African American Reparations Commission (“NAARC”), the Drug Policy Alliance (“DPA”), and others and we have benefitted from their work and leadership. We recognize that the harms of family policing have not always been a part of the Reparations conversation and we seek to honor and situate this ongoing conversation in the legacy of abolitionist freedom weavers by demanding our repair.

We also want to acknowledge the movement forebears in the movement for Reproductive Justice, including the SisterSong Women of Color Collective, whose work continues to empower us to fight for and to defend our birthright to build and care for our families. As mamas, fathers, grandmas, aunties, daughters, children, birthers, caregivers, and revolutionary parents, we know that it is our care, our connection, our Mothering that will turn pain into care and connection.

Our collective freedom requires the elimination of systems that only seek to punish, surveil, and control. We owe it to our children and our children’s children to fight for reparations.

This report, “Families Belong Together, Families Demand Repair”, comes after BLU organized a first-of-its-kind, intimate gathering (hereinafter “the Convening”) of victims and survivors of family policing in February 2024 at the CUNY School of Law in Queens, New York. The goal of the Convening was to begin a collective conversation amongst victims and survivors of the family policing system about the nature of the violence we have all survived and about a pathway to repair.

In addition to the Convening, we distributed a written survey and conducted a series of focus groups to engage a broader swath of victims and survivors of the family policing system. After receiving over 1,100 unique sign-ups to participate in our focus groups, we narrowed our focus group participants down to 60 individuals and vowed to conduct focus groups again in the future. Our written survey received a total of 239 unique responses from people across the United States, the majority of which came from Black cisgender men between the ages of 25 and 34. This survey continued our inquiry into how individuals and families harmed by the Family Policing System view this system and what resources, programs, and support these individuals and their families need or want in order to heal. Although the individual perspectives represented in both the focus groups and the written survey responses are vast, one thing is clear: our communities demand reparations now.

This Report, a labor grounded in a radical love for the victims and survivors of the Family Policing, attempts to archive and contribute to a public record of the violence inflicted by the Family Policing System and the creative, hope-filled discussions that we are having to abolish this system and repair its harm. The next section of this Report will provide a brief overview of our research methodology before sharing the outcomes of our survey and the Convening.

In alignment with our shared commitment to community safety, all data gathered from the Convening, the focus groups, and the written survey that now appear in this report do not include identifying information.

At BLU, we see ourselves as part of a long legacy of abolitionist thinkers, healers, visionaries, and leaders. We seek to continue the work of chattel slavery abolitionists in all aspects of our work, including in our research and policy advocacy. One way we continue the abolitionist tradition in the United States is by demanding the abolition of the Family Policing system and Reparations for victims and survivors of family policing.

Historically, chattel slavery abolitionists used a combination of strategies to achieve abolition, including legislative advocacy, running for elected political office, publishing and distributing anti-slavery literature, and both violent and nonviolent direct action.

Since the formal end of slavery in 1865 and the reconfiguration of slavery through the prison industrial complex and other policing systems, Abolitionist as a term of self-identification has evolved into a more expansive political ideology encompassing the end of every component of our society that upholds policing and imprisonment.

Grounded in an understanding of policing as a means of “reinforcing the oppressive social and economic relationships that have been central to the US throughout its history,” originating with chattel slavery, abolitionists believe that the only way to both create real, lasting safety and to repair harm already caused is to solve the epidemic of State violence once and for all – abolition

Critical Resistance, a U.S. based grassroots organization committed to the abolition of the Prison-Industrial-Complex (PIC), teaches us that: “Abolition is a political vision with the goal of eliminating imprisonment, policing, and surveillance and creating lasting alternatives to punishment and imprisonment…Abolition isn’t just about getting rid of buildings full of

cages. It’s also about undoing the society we live in because the PIC both feeds on and maintains oppression and inequalities through punishment, violence, and controls millions of people.”9

Building on this definition, BLU understands the Family Policing System as one of the many carceral systems responsible for the policing and surveillance of our communities. Scholaractivist Dorothy Roberts writes: “The child welfare system is a powerful state policing apparatus that functions to regulate poor and working-class families—especially those that are Black, Latinx, and Indigenous—by wielding the threat of taking their children from them.”10

As with the abolition of chattel slavery, the goal of modern abolitionist movements is not to reform the Criminal Legal or Family Policing Systems, but instead to radically reimagine approaches to family wellbeing. Rather than responding to the interpersonal violence that happens in our communities between one

another with systemic violence, we propose and support many of the existing communitybased responses that provide holistic support that neither dehumanizes caregivers or their children.

In legal contexts, Reparations refers to the legal framework for the relief of civilians from the commission of gross human rights violations by any country. According to a set of guidelines for Reparations adopted by the United Nations in 2005, Reparations requires five elements: restitution, compensation, rehabilitation, satisfaction, and guarantees of non-repetition.11

The attempt to break down each of the elements in this legal framework is below and its application to involuntary family policing intervention.

DEFINITION: The purpose of Restitution is to restore victims and survivors to their original situation before the harm occurred. From lived experience, we know that nothing can make us forget the tremendous loss and suffering that comes with family separation.

POSSIBLE ACTION: In the case of an involuntary family separation, one action that would promote Restitution is family reunification. For families whose separation is made legally permanent by the Termination of Parental Rights, BLU supports the creation of a formal process to annul, or void, the legal effect of the Termination of Parental Rights and to fully reinstate a parent’s legal rights.

DEFINITION: The purpose of Compensation is not to attempt to put a dollar amount on the trauma experienced by victims and survivors of the Family Policing System. As victims and survivors ourselves, we know that there is not enough money in the world to make up for even a single holiday or birthday spent away from your child or from your parent/caregiver. Instead, Compensation is about acknowledging that coming from low-income families and working class neighborhoods has placed a target on our backs for Family Policing System intervention. We believe that our families and our communities are owed direct payments for our pain.

POSSIBLE ACTION: As it relates to how and in what amount direct cash payments would be made to victims and survivors of family separation, we do not claim to have all of the answers. Looking at state and national case studies, including direct payments made to survivors of forced sterilization by the states of California, North Carolina, and Virginia, we know that direct payments for systemic violence are possible! Some factors that have come up in our discussions about direct payments include:

● How many generations of this family have been harmed by family policing?

● How long has the Family Policing System been involved with the family? Six months? A year? Multiple years?

● Has this family experienced the Termination of Parental Rights? If so, how long ago did the Termination of Parental Rights take place? Where is the parent today? The child? These factors are by no means exhaustive, but they are a place for us to begin this conversation!

DEFINITION: The purpose of Rehabilitation is to make as much of the care and support services that a family needs in order to heal on an individual and group level accessible to that family as possible. To truly be rehabilitative, the victims and survivors of family policing must be the ones to determine which services that they and their families need and cost must no longer be a barrier. People and their families should never be coerced or pressured to use any rehabilitation services.

POSSIBLE ACTION: In the case of an involuntary family separation, all members of a family, including those who may not live in the same household, experience the trauma of that loss. One action that would promote Rehabilitation may be to make trauma-informed individual and family counseling services available free of cost both in-person and virtually. In addition to being trauma-informed and free of cost, we also advocate for these services to be culturally-responsive, age-appropriate, and available to individuals and families for as long as they need and desire them. We also advocate for these services to include, as desired, substance (ab)use counseling and trauma recovery services geared toward survivors of domestic violence and sexual violence.

DEFINITION: The purpose of Satisfaction is to repair what is sometimes referred to as “Moral Damage,” or the harm that is done to a person, their family, and their community by dehumanizing them. On a systemic scale, Black people, people of color, and poor people are dehumanized through messages that we are less capable of being loving and supportive parents and more prone to violence than other groups of people.

POSSIBLE ACTION: From the moment someone from so-called child protective services (“CPS”) first enters a home, dehumanizing messaging surround the individual and the family now dealing with allegations of child abuse or neglect. CPS agents, attorneys, judges, and even the people in our communities all can reaffirm ideas of system-impacted people as being immoral, cruel, and as lacking any kind of love and care for the children in their lives. This message remains a guiding narrative in all stages of the Family Policing System. One action that would promote Satisfaction is for formal and public apologies to be given to individuals and families who have experienced family separation. These apologies should include a sincere expression of regret for the actions of the government, systems of policing, and individuals, and a full acceptance of personal responsibility for the harm caused. Some of the people and entities who owe victims and survivors of the system an apology are federal policymakers, state and local policymakers, CPS agencies, and CPS agents. At all levels of government, these apologies might also include honoring victims and survivors of family policing through commemoration, such as a day of remembrance.

DEFINITION: The purpose of Guarantees of Non-Repetition is to implement law, policy, and other mechanisms to prevent systemic harms from happening again. To truly put an end to the harms of family policing, we believe that family policing must cease to exist. The surveillance, harassment, intimidation, and separation of our families is the core mission of family policing; it’s not a glitch in an otherwise just system.

POSSIBLE ACTION: Learning from the testimony of victims and survivors of family policing and other systems of carceral violence, the pathway to non-repetition of the violence of family policing is to abolish the systems policing our families and to replace the Family Policing System with completely new and humane ways of protecting our children and our families. The outcome of each step we take towards abolition should be that we are getting closer and closer to a world where involuntary family separations no longer happen.

“Reparations is a process of repairing, healing and restoring a people injured because of their group identity and in violation of their fundamental human rights by governments, corporations, institutions and families. Those groups that have been injured have the right to obtain from the government, corporation, institution or family responsible for the injuries that which they need to repair and heal themselves.”

Before being recognized as international law, Reparations was a movement demand and organizing strategy by Black, Indigenous, and other colonized peoples. N’COBRA, a massbased organization fighting for Reparations for Black people in the United States since its founding in 1987, defines Reparations as:

“Reparations is a process of repairing, healing and restoring a people injured because of their group identity and in violation of their fundamental human rights by governments, corporations, institutions and families. Those groups that have been injured have the right to obtain from the government, corporation, institution or family responsible for the injuries that which they need to repair and heal themselves.”12

While the adoption of a Reparations framework as international law has absolutely legitimized grievances and demands of Black people living in the United States in the eyes of elected officials and world leaders, we reject any suggestion that our grievances and demands lacked credibility and legitimacy before 2005. The very idea that people of color are not on our own credible lived-experts is a byproduct of the same racist dehumanization that people of color continue to experience in the Family Policing System and other policing systems in the United States.

BLU’s commitment to Reparations for victims and survivors of family policing is also grounded in the idea that legal and policy solutions should not be limited to preventing future harms from occurring. Legal and policy solutions should also seek to make amends for harm already caused or currently occurring. Our commitment to Reparations is one aspect of the organization’s broader commitment to engaging in community organizing and policy advocacy rooted in Abolition and Reproductive Justice.

The origins of the Family Policing System are deeply rooted in the United States’ history of dehumanizing Black mothers and Black children, beginning with chattel slavery and escalating through every iteration of Black-led resistance to the subjugation of Black people.

In March of 1865, the United States Government established the Bureau of Refugees, Freedmen, and Abandoned Lands (“The Freedmen’s Bureau”) to monitor African descendants living in the United States making

their transition from enslaved people to newly emancipated people. Among the specified goals of the Freedmen’s Bureau was to reunify families intentionally separated as part of the institution of chattel slavery and during the Civil War. Prior to the Freedmen’s Bureau, “there was no tradition of government responsibility for a huge refugee population and no bureaucracy to administer a large welfare, employment and land reform program”.13 The Freedmen’s Bureau was quickly dismantled in 1872 due to a combination of inadequate federal resources and the racial terror waged against newly emancipated Black people and their families by white people living in the South.14 For better and for worse, the precedent for such a federal responsibility was set by the Freedmen’s Bureau. The modern Family Policing System is proof that State intervention in people’s lives and families will never be the solution to family separation, mass displacement, and other social problems arising from both.

Decades later, in retaliation to growing national support for school desegregation, racist, sexist, and classist narratives about Black women and Black motherhood fueled a nasty propaganda campaign and violent policy agenda. White legislators, judges, parents, and even teachers, publicly smeared Black children as “bastards” and warned that integrating these “illegitimate” children born from the “illicit sex” of their Black, “welfare abus[ing]” mothers would permanently erode America’s

schools.15 Immediately after the Supreme Court of the United States ordered nationwide school desegregation in Brown v. Board of Education (1954), the State of Mississippi amended its law to remove all children from the state’s welfare roll if those children did not live in a “suitable home.”16 As a direct consequence of this Mississippi law, the State denied welfare to more than 8,000 children who were otherwise eligible to receive it between 1954 and 1960.17 In 1957, the same year that the “Little Rock Nine” successfully integrated Little Rock Central High School in Little Rock, Arkansas, the Governor of Arkansas responded with the state’s very own “suitable home” regulation.18 A 1960 study on Florida’s “suitable home” statute revealed that “state welfare workers challenged the ‘suitability’ of 13,000 families, of which only 9% were white, even though white families made up 39% of the total caseload.”19 Furthermore, “only 186 families being starved by the [Florida] welfare system voluntarily relinquished their children” and, to the surprise of state workers “another 3,000 families withdrew from the welfare program rather than lose their children.”20 The intervention of the state’s workers comes from age-old narratives about Black women lacking the ability to be loving, caring, and overall “suitable” mothers to their children.

Today, the presumption that Black people are apathetic towards their children remains a core tenet of how family policing is carried out in

poor and working class Black communities. In 2023, BLU co-founder and Executive Director Imani Worthy recounted the role of this presumption in her experience navigating the family policing system as a new mother.

Part of the legacy of racist, sexist, and classist narratives about Black women and Black motherhood is that Black mothers cannot rely on any one, including the medical providers responsible for maternal and infant healthcare.

“...When my blood sugar was too high during my weekly check-ins, healthcare professionals forewarned me that unless I effectively managed my diabetes, they would report me to ACS…After my son was born…I couldn’t get [my son] to latch or to take a bottle. Week after week, I diligently brought my son to his pediatrician for weigh-ins, but feeding [my son] just became an uphill battle… and his condition deteriorated with each passing day. Eventually, there was an accident that we could not account for…the doctor cited [my son’s] failure to thrive and this accident as grounds to report me to [ACS]. Ironically, even the hospital struggled to get my son to take his bottle, leading to a three week hospitalization and the insertion of a feeding tube through his nose. Instead of receiving the support I desperately needed, I found myself unjustly labeled as a child abuser and accused of neglecting my son.”

In Imani’s case, we see that she, a Black patient living with diabetes, sought medical care only for her provider to threaten to call CPS due to her medical diagnosis and blame her for struggling to manage her diagnosis; we see a Black mother and a Black child being denied access to compassionate, high-quality healthcare, and then labeled as “failing” to thrive.

At BLU, we view and do our work through a Reproductive Justice lens, recognizing that the family policing system denies poor, Black, and other marginalized people the right to build and care for their families. The systemic kidnapping of poor, Black, and other marginalized children from their families interferes with these families’ ability to bring children into this world and to raise them. One of the four tenets of Reproductive Justice is the principle that each person has a human right to “nurture the children we have in a safe and healthy environment”.21 The Family Policing System and other policing systems continue to deny this basic human right to Black mothers and their families.

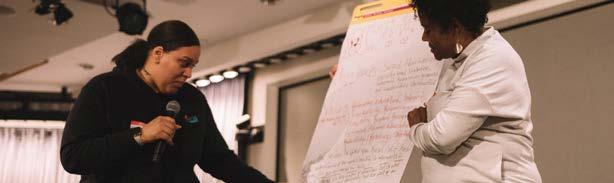

On February 24, 2024, 45 people directly harmed by the Family Policing System gathered together at CUNY School of Law to share individual testimonies of our lived experiences of system intervention, to begin building a framework and organizing strategy for Reparations, and to begin the conversation

about what exactly Reparations looks like for victims and survivors of Family Policing.

Committed to building a shared framework for Reparations, the Convening only included people who have been directly harmed by the family policing system and utilized discussion groups to allow convening participants to speak candidly about the racism, sexism, classism, and other traumatic experiences that people entangled entangled in this system experience day-to-day.

DOES NOT PREVENT CHILD ABUSE NOR DOES IT PROVIDE THE SUPPORT, FINANCIAL OR OTHERWISE, THAT FAMILIES WANT AND NEED TO PREVENT AND RESPOND TO INTERPERSONAL VIOLENCE.

Across the five discussion-groups – Carceral, Domestic Violence, Foster Care, Mental Health, and Substance Use – Convening participants overwhelmingly reported both that: (1) the Family Policing System failed to intervene to prevent abuse, including sexual abuse and domestic violence, in their lives or the lives of their families and (2) In circumstances where the Family Policing System did intervene, the intervention of the system was a traumatic experience. Some of these Convening participants even shared that system intervention permanently fractured their families and has proven to be an impossible obstacle to overcome as they seek to heal their own trauma and to reunite with their families.

In each of the Domestic Violence discussion groups, Convening participants who experienced or witnessed domestic violence first hand shared that the fact of a caregiver’s experience as a survivor of domestic violence was often weaponized against them by the Family Policing System. When asked to use three words to capture their experiences with the Family Policing System, one Convening participant, a domestic violence survivor, said, “Mad, scared, and alone…[Living in a] domestic violence shelter, it is an isolating experience for the parent.” Another Convening participant shared that they, a caregiver previously involved in the Family Policing System, experienced homelessness due to domestic violence and was in turn separated from their child for more than a decade. “There is a misconception that [CPS] will help [domestic violence] survivors”, one participant said, “but [CPS] invites more surveillance,” likening the experience of being tormented by their abuser to being hounded by [CPS] agents.

Across the five discussion groups, Convening participants recounted experiences of seeking support from CPS referral programs, specifically for mental health struggles, only to

have their children forcibly removed from their care as a response. One Convening participant shared that their child is currently in foster care because of the participant’s decision to seek care for postpartum depression. The Family Policing System punishes caretakers who identify their own support needs and then seek out support, while claiming to exist to do the opposite – to support families who need and ask for it. nother Convening participant said, “They come in like a wrecking ball. They want everything. They want all [your] records. They strategically pick and choose things to hold it against you and keep your kids away from you. That’s not what [CPS is] there for. You’re there to look at a whole – not pick and choose things to use against you and your family.” The Family Policing System punishes caretakers for seeking support services because the goal of the Family Policing System has never been to prevent or hold people accountable for abuse and neglect at all. The Family Policing System is a site of abuse, neglect, dehumanization, and trauma in and of itself.

Convening participants were also broken into five distinct discussion groups based on participants’ lived experiences that either triggered the intervention of the Family Policing System or most deeply impacted their lives: Carceral, Domestic Violence, Foster Care,

Mental Health, and Substance Use. Over the course of our one day together, participants shared deeply personal and varied experiences about navigating the Family Policing System

Convening participants reported varied experiences of the routine disrespect, dehumanization, and sexual and gendered abuse that happens in United States prisons and jail. One Convening participant, who was pregnant during her incarceration, recounted the experience of being repeatedly ordered to strip down completely naked throughout her pregnancy despite her pleas to keep, at least, her shoes and bra on due to how difficult it was to remove them. Another Convening participant recounted the vicarious trauma their children experienced visiting them in prison. This Convening participant shared, “[the] parent is treated poorly in prison and so are the children coming to visit”.

As we began discussing above, for people experiencing and witnessing domestic violence firsthand, the Family Policing System oftentimes enabled that violence and deepened their trauma. Several Convening participants shared that, during the course of domestic violence related CPS investigations,

CPS threatened to separate children from their caregiver experiencing domestic violence. One Convening participant expressed, “ACS threatened to remove children during DV investigations, adding to the trauma rather than helping. The system’s involvement often led to more surveillance and less support.” For many victims and survivors of family policing who have experienced or witnessed domestic violence firsthand, system intervention only brought surveillance into their lives and created a new cycle of fear instead of providing support.

The experiences of Convening participants who navigated the foster care system were equally harrowing. Their stories revealed that life in the foster care system consisted of cyclical removal, abuse, neglect, and abandonment. One Convening participant shared, “Foster care was a lie. I was abused, molested, and even stabbed. Friends from [foster] care committed suicide due to the trauma.” Another Convening participant recounted her repeated failed attempts to get proper support while in the foster care system. She shared that “the system criminalized us for seeking help and failed to provide proper support or resources, perpetuating cycles of harm and abuse.”

Convening participants also reported a variety of firsthand experiences with mental health stigma by agents of the Family Policing System and the far-reaching negative impacts of a lack of high-quality mental health services in their communities. When describing the experience of seeking mental healthcare, Convening participants used language like “judgmental” and “violent”. One Convening

participant shared, “[CPS] dismantled existing support systems, forcing us into their chosen services, often with incompetent providers. The experience was overwhelming and humiliating.” Experiencing CPS agents’ disrespect and apathy while seeking support only made matters worse, according to one Convening participant, who shared, “The system treated parents like they knew nothing, disregarding our insights and needs. This lack of respect and empathy worsened our mental health issues.”

Convening participants also reported stigma towards people who use substances and/ or may experience substance addiction. Convening participants described the treatment of people accused of or who admit to using substances by the Family Policing System as “hurtful” and “shameful”. Some of the hurt Convening participants experienced was due to “feeling powerless, voiceless”, being denied the ability to breastfeed one’s own child, and losing the “chance to bond” with one’s child. For one Convening participant who stopped using substances altogether, the Family Policing System refused to “honor [their] growth” and used their history of substance use “against [them]” as if sobriety didn’t ultimately matter. Another Convening participant described the experience as completely stripping her of her motherhood –“taking away [her] maternity”. Participants’ personal narratives and reflections on these experiences shed light on the profound emotional, psychological, and other impact of Family Policing System intervention on the trajectory of their lives. Below, we continue summarizing these personal narratives and reflections.

During the Convening, participants were asked to describe their experiences in the Family Policing System using just three words. Here are some of our Convening participants responses:

● “Unjust, institutionalized, perpetual,” reflecting the systemic racism embedded in the Family Policing System and unfair practices,

● “Degrading, dehumanizing, repulsive,” reflecting the profound emotional and psychological toll of system intervention and the weight of the indignities they faced dayto-day.

● “Scary, frightening, unnerving”, reflecting the fear and uncertainty associated with navigating the Family Policing System,

● “Anger, betrayal, anxious”, reflecting the range of emotions felt by one caregiver throughout the system’s intervention in their life and the lives of their family, and

● “Scared, indecisive, retraumatized” reflecting the experience of a caregiver navigating interpersonal violence and systemic violence at the same time – domestic violence and the Family Policing System.

Commonly cited values included protecting one another, integrity, empathy, respect, honesty, as well as communication. In response to the question of whether the Family Policing System took note of and respected families’ dynamics and values, many Convening participants said no. One Convening participant described their family’s core values as “protecting and empathy”, and then said, “the system did not respect these values; instead, it subjected us to constant surveillance and mistrust.” Another Convening participant shared that “Respect and honesty are crucial in [their] family”, and that “[CPS] failed to honor these [values], often intruding disrespectfully [into family matters] and ignoring our communication [with one another].”

THE INTERVENTION OF THE FAMILY POLICING SYSTEM INTO THEIR FAMILY LEAVES PEOPLE WITH BOTH PRIMARY AND SECONDARY TRAUMATIC STRESS FROM WITNESSING HOW CARCERAL SYSTEMS MISTREAT THEM AND THEIR LOVED ONES

Convening participants’ personal narratives revealed deep-seated vicarious trauma due to forced interactions with the Family Policing System and other policing systems. One Convening participant recounted childhood visits to an incarcerated parent, “Visiting my parent in prison was traumatizing. The system treated both the incarcerated parent and the visiting children poorly, perpetuating trauma into adulthood.” Another Convening participant, who was previously incarcerated, recounted her lived experience of invasive and dehumanizing security screenings associated with family visits while she was pregnant in prison.

FOR PARENTS, THE

FAMILY

POLICING SYSTEM OFTEN RIDICULED THEIR DECISIONS, WEAPONIZED DETAILS OF THEIR PASTS, AND UNDERMINED THEIR

AUTONOMY

The Family Policing System’s persistent intrusion and intervention into parental autonomy and parents’ decision-making was a recurring theme. Participants recounted

instances where their children were taken by CPS for minor incidents, leading to incarceration and further trauma. One mother recalled, “My children were taken by CPS for minor incidents like inappropriate dancing or running away, leading to incarceration and further trauma.” Another shared the harrowing experience of kinship foster care abuse, where her children were abused but did not tell her out of fear of losing their connection.

FEW CONVENING PARTICIPANTS SHARED PERSONAL NARRATIVES THAT INCLUDED FEELING SUPPORTED BY CPS AGENTS OR THE FAMILY POLICING SYSTEM IN GENERAL.

Some Convening participants recounted positive experiences with CPS agents, including one Convening participant acknowledging that, perhaps indirectly, system intervention pushed her to acknowledge and begin working toward some clear goals. At other points in Convening, a handful of other Convening participants recounted brief moments of open-mindedness and understanding from CPS agents. Overwhelmingly though, Convening participants did not experience the Family Policing System as being made up of “only a few bad apples”. Quite the opposite, because the problems being described are systemic rather than solely being rooted in individual biases.

This singular gathering did not produce one definition of Reparations or one strategy for achieving Reparations for ourselves, our families, and our communities; Building a shared definition and developing a grassroots organizing strategy will take time.

Pulling on the major threads in these Convening participants’ discussions, we now attempt to capture some how Convening participants believe Reparations for family policing could and should take shape.

Below is a summary of the discussions between Convening participants about the policies, practices, and strategies that promote Restitution.

● Targeted decarceration efforts, including re-entry support and expungement, for victims and survivors of domestic violence, sexual abuse, and other interpersonal violence. Sealing records is not enough, and does not acknowledge that victims and survivors of these forms of violence should not have been criminalized.

● Exhaustive efforts to locate members of separated families and to eliminate barriers to family reunification (e.g. availability of reliable public transportation and the cost of travel).

● Targeted job support efforts for victims and survivors of family policing. One consequence of being listed on the Statewide Central Register (“SCR”) is becoming ineligible for the kind of work typically done by the people who are most likely to be listed on the SCR.

● Universal programs that benefit all people, including universal basic income programs, universal access to stable housing, free programs geared towards promoting literacy in historically underserved communities.

Below is a summary of the discussions between Convening participants concerning Compensation, specifically direct payments and broad financialw investments in underserved communities.

● Direct payments to victims and survivors of the Family Policing System by local and state agencies responsible for the intervention of the Family Policing System into their lives.

● This financial debt should also be repaid by the companies and corporations who fund mass incarceration and who benefit from mass incarceration through prison labor, because of the Foster Care-to-Prison Pipeline.

● Financial investment to “fix up” the neighborhoods and communities that are

frequent targets for Family Policing System intervention based on generational poverty and a historic lack of investment.

● Any direct payment or financial reinvestment must be grounded in accountability, or else those payments become “hush money”, or money used to appease and silence victims and survivors of family policing.

● Any direct payment or financial reinvestment must also be awarded in conjunction with systemic changes, or else those payments become “a bandaid”.

● Culturally-relevant, non-judgmental community programs to shift community mindset about money, to teach their community how to manage money, and to provide support in creating and maintaining generational wealth.

● Victims and survivors of family policing must have agency over the use of direct payments that they receive. Some examples of how Convening participants would like to use these funds include:

-Buying and maintaining a family home,

-Seeking dental care to “fix [their] teeth”,

-Accessing a high-quality health insurance plan and healthcare services,

-Investing in themselves and their families after generations of poverty, years of system intervention, and living in shelters.

Below is a summary of discussions between Convening participants about the policies, practices, and strategies that promote Rehabilitation.

● Free, lifelong and holistic body-mind care services to all directly impacted people that exist outside of the Family Policing System.. These services could include individual and group counseling, tailored emotional support services for pregnant and postpartum people, and non-judgmental support services for people who currently use or previously used drugs.

● Holistic and age-appropriate trauma services to young people currently enduring physical, emotional, and sexual abuse as a consequence of being in the family policing and/or juvenile legal systems.

● Financial investment in community-led services and “safe havens” to give poor families somewhere to reunite with one another and to give all families a fair chance at healing and reconnecting. To quote two Convening participants, “[We need] time, resources so that we can spend time individually and in community” and “[We need] safe neighborhoods and access to resources that any family would need to raise children in dignity”.

Below is a summary of discussions between Convening participants about the policies, practices, and strategies that promote satisfaction.

● Acknowledgement that the Family Policing System targets, punishes, and surveils Black, brown, working class, and poor families, especially single parents and their children. To quote one Convening participant, “Revealing how the system has been so violent is important - systems are isolating, make you feel ashamed.”

● Acknowledgement and an acceptance of responsibility for the harms experienced by families that were separated by the Family Policing System. To quote one Convening participant, “Do a full accounting of what was done wrong and who did it, what could be done differently, what can be done to ensure nothing like that will happen again.”

● Acknowledgement and an acceptance of responsibility to victims and survivors of domestic violence, sexual abuse, and other interpersonal violence who were discredited by the Family Policing System and ultimately fed into other policing systems by agents of the Family Policing System.

● Acknowledgement and an acceptance of responsibility for the role of the Family Policing System in contributing to and maintaining a culture where gender marginalized people, including women and girls, are abused without real accountability.

● Acknowledgement and an acceptance of responsibility for the persistent failure of the Family Policing System to connect victims and survivors of interpersonal violence to free, trauma-informed, culturally-relevant, non-judgmental resources necessary to live and to parent in a safe, healthy environment (e.g. stable housing, mental health counseling).

● Acknowledgement and an acceptance of responsibility for the Foster Care-to-Prison pipeline and for the profound trauma experienced by young people transferred from one traumatic system immediately into another.

● A commitment to a wide scale narrativeshifting campaign, which should include public education about the history of family policing in the United States and the history of victims and survivors of family policing fighting back against the system. Convening participants also expressed support for the inclusion of other topics, including Reparations, Black Feminisms, and abolition, in history curricula for school students at all levels.

Below is a summary of discussions between Convening participants about the policies, practices, and strategies that will guarantee the non-repetition of the harms experienced by victims and survivors of family policing. This summary attempts to capture both Convening participants’ demands of government actors and some hopes and dreams Convening participants have for their communities.

● Convening participants hold diverse perspectives and viewpoints about abolition versus reform of the Family Policing System. However, all Convening participants make clear that it is deeply important to them to prevent their children and their children’s children from the Family Policing System.

● To prevent the Family Policing System from intervening in future generations of families, the autonomy of families of color and poor families must be restored. Across the five discussion groups, Convening participants use language like “control”, “humiliation”, “pressure”, and “forced” to describe how the Family Policing System operates. To quote one Convening Participant, “[We need] freedom to make our own decisions…I don’t think an outsider should come in and force what they believe is right for you. We know what is best for our families…We know what is best for our communities.” Another

Convening participant invoked the saying, “It takes a village”, and expressed excitement around deepening relationships to their neighbors who share and respect these values and supporting one another in building families and raising children.

● Although Convening participants do not feel that they alone have all the answers to questions about what should exist instead of the Family Policing System, some of the proposals made during the Convening include:

Sharing the responsibility of walking children to and from school with other caregivers in the neighborhood,

Creating more opportunities for parents to get to know their children’s teachers and vice versa, especially parents who are seen as less active due to a demanding work schedule, Creating neighborhood “Single Moms Clubs” to support meaningful relationships between single mothers, leaning into building one’s “village” or support system.

Free community-run centers where young people in the neighborhood can do free activities (e.g. play games) together.

Sharing the responsibility of responding to interpersonal harm, such as domestic violence and child abuse, between community members by undergoing trainings in restorative justice, conflict resolution, safety planning, and violence intervention

strategies. Convening participants generally support communities working together to solve conflict and respond to harm instead of policing systems intervening in community conflict and harm.

● Negative stereotypes about people of color and poor people play a huge role in how the Family Policing System treats these communities. Convening participants emphasized that trusting and respecting people of color and poor people will be central to eliminating family policing. Convening participants unified around the shared experience of coming from diverse households with strong values and distinct cultural norms, only to have these values and customs disregarded by the Family Policing System. To quote one Convening participant, “The more values you have, the more annoyed [CPS is]. The more you stand your ground and stand up for your family, [the more that] you get punished…If you stand up in court to get your kids, you don’t get your kids…I’m a human. I don’t have my kids. I miss my kids…They decontextualize...the anger, the tears, the fear…”

● Stigma against people who have struggled with their mental health is a huge reason why certain families experience system intervention. Part of eliminating family policing must be eliminating all policies and practices that further dehumanize and deny autonomy to people who struggle with their mental health. This includes people who have been labeled as having a problematic or dependent relationship to drugs and alcohol (e.g. addiction).

● Some Convening participants focused on specific policies and practices that they would like to see eliminated as a pathway toward totally eliminating family policing.

These policies and practices include:

Mandatory or Mandated Reporting – At one point during the Convening, a small group of participants formed a Mandated Reporting discussion group. In their conversations, Convening participants expressed how problematic it is that Mandated and Mandatory Reporters are given so much deference in the eyes of the Family Policing System, which means that a caregiver is automatically seen as less credible regardless of what evidence that caregiver has to dispute the claims made against them. Although Convening participants acknowledge that some people do file reports in good faith, others do so from a place of bias, discrimination, and dishonesty.

Accountability for Misconduct by Judges –Also discussed in the Mandated Reporting discussion group was accountability for judges and for the lawyers representing CPS. One Convening participant recalled complaining to their caseworker about the behavior of the judge presiding over their case. According to this Convening participant, “I wrote to [the Office of Child and Family Services] to complain, and they said, ‘We don’t have any jurisdiction over [judges]’.” Another Convening participant recounted a similar experience but with attorneys representing CPS. According to this Convening Participant, “...Parents have a service plan and we’re told ‘do this, and you get your kids back’ and [CPS does not tell you] that if [you don’t complete the program] in a certain time frame…you can’t get your kids back…I did five..six programs over the years…still didn’t get my kids back. [CPS] told me if I did this, I would get my kids back. I didn’t. [CPS] lied to me.” These accounts prompted questions about the professional responsibilities of judges and attorneys,

who judges and attorneys are directly accountable and answerable to, and the process for filing and investigating complaints made against judges and attorneys.

● Some Convening participants discussed eliminating the Family Policing System more broadly, and expressed hope for more spaces in which parents can be heard, heal, and gather together to “put the [Family Policing] System on trial” and discuss how to reduce the amount of power the system has on their lives currently.

On February 27, 2024, BLU made a written survey available to victims and survivors of family policing across the United States with the goal of gaining a deeper understanding of the socioeconomic factors that precede the family policing system’s intervention in people’s lives, the impact of this system’s intervention on families, and how victims and survivors of this system believe Reparations should take shape. Largely enlisting survey participants using social media and word-ofmouth, we are proud to share that 239 people with lived experience of Family Policing System involvement moved forward and completed our survey in full.

As an organization led by people who experienced Family Policing System involvement as parents, as young people, or multiple times throughout our lives, we also sought to uplift the lived experiences of people who experienced the violent intervention of this system as adults and as young people, rather than only one or the other. We are

proud to report that of the more than 200 people who completed our survey, 52.3% reported experiencing Family Policing System involvement as a parent/caregiver and 44.8% reported experiencing Family Policing System involvement as a child/young person – a fairly even split.

Below, we report on these survey findings.

The majority of respondents (48.5%) reported being between the ages of 25 and 34. The second and third most represented age demographics are people 65 and older (23.8%) and people between the ages of 35 and 44 (19.2%). Although we only surveyed people ages 18 and older, we acknowledge that people under the age of 18 are also victims and survivors of family policing and other policing systems and hope to engage young people in future surveys.

The majority of respondents (56.9%) reported their gender identification as a cisgender man. The second most represented gender population is cisgender women (28.9%).

The majority of respondents (57.7%) reported their race/ethnicity as being Black/African Descent. The second, third, and fourth most represented racial/ethnic populations are people of Hispanic or Latino/a/x descent (15.5%), people of Native American or Indigenous descent (11.7%), and people who are white (10%). The high response rate of people of Black/African descent and of Native American/Indigenous descent is relatively consistent with national data on the racial and ethnic identification of children entering foster care. According to national data in 2021, “Black

children represented 20% of those entering care but only 14% of the total child population, while American Indian and Alaska Native kids made up 2% of those entering care and 1% of the child population”.22 Although national data on foster care tends to focus on the children entering and in foster care, whereas our survey includes people who have experienced Family Policing System intervention as young people, adults, or both, we can see that our data speaks to the racial overrepresentation of people of Black/African descent and Native American/ Indigenous descent.

The majority of respondents (40.2%) reported that the intervention of the Family Policing System in their life and/or in the lives of their families lasted between six months and one year. The second, third, and fourth most represented lengths of system intervention are between one and three years (28%), less than six months (15.9%), and, close behind, more than three years (15.5%). Based on national

40.2%

reported that the intervention of the Family Policing System in their life and/or in the lives of their families lasted between six months and one year.

foster care data, in 2022, the median amount of time that a child exiting foster care spent in the system was 17.5 months.23 Approximately 14% of children in foster care have experienced foster care for three or more years. If we are to assume that these children are either reunified with their families or permanently separated from their families through a Termination of Parental Rights (“TPR”) proceeding, then this number is almost directly proportional to the number of respondents who report experiencing Family Policing System intervention for a duration of more than three years.24

When asked about how the experience of Family Policing System intervention impacted their family dynamics, the majority of respondents (35.1%) reported that Family Policing System intervention strained their family relationships. 31.8% of respondents reported that their family relationships were ultimately made stronger in the aftermath of forced Family Policing System intervention. 22.6% of respondents reported that the intervention of the Family Policing System

22.6% 35.1%

reported that Family Policing System intervention strained their family relationships.

reported that the intervention of the Family Policing System resulted in the separation of their families.

According to a joint report by the American Civil Liberties Union (“ACLU”) and the Human Rights Watch (“HRW”), these involuntary family separations are “acutely distressing” and the circumstances surrounding the involuntary separation of a family can augment the family’s trauma and emotional suffering.

resulted in the separation of their families. According to a joint report by the American Civil Liberties Union (“ACLU”) and the Human Rights Watch (“HRW”), these involuntary family separations are “acutely distressing” and the circumstances surrounding the involuntary separation of a family can augment the family’s trauma and emotional suffering.

“Some parents described being placed in handcuffs and escorted away from their children by a police officer. Others described the look of confusion on their children’s faces as they left with a caseworker. Many parents describe visiting their children’s rooms in the immediate aftermath, holding their children’s favorite toy, or trying to hold on to their smell. The profound loss and sheer helplessness of the moment was evident in every parent’s story.”25

When asked about whether they or their family was satisfied with the quality of the services provided as part of the Family Policing System’s intervention in their lives or the lives of their family, only 28.5% of respondents reported being very satisfied. Most respondents reported being somewhere along the spectrum of somewhat satisfied (39.3%) and neutral (19.7%). A significant number of respondents also reported being either somewhat dissatisfied or very dissatisfied with these services. For clarity, so-called “child protective services” agencies, which are one part of the Family Policing System, typically do not directly provide counseling and/or substance (ab)use treatment services. As such, whether families are satisfied with these types of services depends on the availability of comprehensive counseling, substance (ab)use treatment, and other mental health services providers in their area and the quality of their local “child protective services” agency’s referral network.

All respondents were asked a series of questions to deepen BLU’s understanding of what victims and survivors of the Family Policing System believe constitutes Reparations, which entities are responsible for making Reparations to victims and survivors of the Family Policing System, and what resources and programs our communities need to get started. These questions, and respondent’s responses, are as follows:

1What are some of the social shifts that you believe are immediately necessary to begin repairing the harm done to your community by the Family Policing System?

The majority of respondents (62.3%) reported that a social shift away from family separation and toward family reunification and preservation is immediately necessary to begin repairing the harm done to victims and survivors of family policing.

More than half of survey respondents (56.1%) also expressed the need for a shift away from punitive, judgmental mental health services and toward confidential, compassionate mental health support without any negative repercussions.

43.9% of respondents indicated support for the immediate implementation of culturallyresponsive practices within the Family Policing System pending a total end to family policing.

32.6% of respondents indicated support for an immediate acknowledgement of and a broad commitment to redress for historical injustices faced by marginalized communities.

Based on the harms you’ve experienced or observed, who do you believe are the responsible people and entities to make Reparations?

In response to this question, the majority of respondents (58.2%) both chose the two following answers:

Government agencies overseeing the administration of family policing, including Child Protective Services, and

Non-profit organizations whose stated mission is to advocate for children and families.

45.6% of respondents indicated that while community-based initiatives led by victims and survivors of family policing do not owe Reparations, these groups and initiatives should steer this process.

34.3% of respondents expressed a similar sentiment regarding the role of educational institutions providing resources and support to victims and survivors of family policing.

Just one survey respondent expressed that individual people who filed reports of child abuse, neglect, and maltreat in compliance with mandated reporting laws owes Reparations.

We understand that there are diverse perspectives on the implementation of the various components of a Reparations package for family policing. What are some aspects of implementation that you are concerned about?

The majority of respondents (58.2%) expressed concern that, in the implementation stage, emphasis would be placed on direct payments to victims and survivors of family policing, and no other material changes would follow.

A majority of respondents (52.3%) also expressed concern that changes made in law and policy would focus solely on punitive measures taken against families, and fail to acknowledge the harms that take place before a family is separated.

A majority of respondents (51.9%) also expressed concern that law and policy will be changed and implemented without meaningful community involvement.

In a similar vein, 28.5% of respondents expressed concern that the voices and lived experiences of victims and survivors of family policing would be totally discarded throughout a Reparations process.

What hopes do you have for programmatic and resource offerings made available as part of a Reparations package for family policing?

The majority of respondents (60.7%) expressed hope for educational and vocational training opportunities for victims and survivors of the Family Policing System.

A majority of respondents (58.2%) are also hopeful for trauma-informed therapy and counseling services.

A majority of respondents (56.1%) also shared their hopes for tailored financial assistance and other support in securing stable housing.

34.7% of respondents are hopeful for increased community-based support groups and support networks by and for victims and survivors of family policing.

What are some factors that you believe we should be thinking about when determining the success of a Reparations process for family policing?

A majority of respondents (64%) indicated that one metric for success will be whether the Reparations program provides ongoing support to victims and survivors of family policing beyond the immediate interventions discussed above.

A majority of respondents (60.7%) indicated that another metric for success will be whether the Reparations process and program was as accessible to and inclusive of victims and survivors of family policing as possible.

A majority of respondents (51%) indicated that another metric for success will be whether the Reparations process and program centers and is actually responsive to the needs of marginalized communities.

38.5% of respondents indicated that the success of a Reparations process and program will be contingent upon whether an accountability process, specifically one that monitors the effectiveness and overall impact of the Reparations measures, is implemented.

How can Reparations support your community in counteracting shame associated with experiencing family policing and promote healing?

A majority of respondents (72.8%) expressed that Reparations would promote healing by finally addressing historic and ongoing systemic inequality and bias perpetuated by the Family Policing System.

A majority of respondents (56.9%) shared that Reparations would support communities in their healing by promoting cultural responsiveness and setting a baseline for respect across government services.

A majority of respondents (51%) expressed that Reparations would promote healing through its investment in community-led programs and initiatives that empower and support the leadership of directly impacted people.

33.9% of respondents reported that Reparations would promote healing by establishing formal mechanisms for truth-telling and reconciliation as it relates to the harms of family policing.

Above, you’ve read stories of loss and hope from the people and families directly impacted by the Family Policing System. While there is no way to completely undo the generational harms of systemic racism, including the harms experienced by people who’ve experienced system intervention, we can end these cycles of systemic and interpersonal violence. The path to healing is a long one, and we make no misrepresentation that we have all the answers. However, from our community to yours, we offer the following insights and recommendations for how victims and survivors of family folicing and our allies can mobilize and organize toward abolition and for Reparations together.

Build Coalitions and Campaigns That Value Diverse Sources of Expertise. As both a movement demand and strategic approach to law and policy, Reparations is intended to be responsive to the unique needs of communities experiencing systemic and other violence. Any coalition or campaign that emerges to prevent or put an end to the violence of family policing must value the livedexpertise of the parents and young people radicalized by their experiences with and in the family policing system. Valuing lived expertise includes but is not limited to:

● Center movement leaders who have lived experience with racism in the Family Policing System and grassroots organizing guided by a commitment to eliminating white supremacy. Fighting back against the Family Policing system will take more than creating space for victims and survivors to share our lived experiences; it also requires that we build shared understanding of white supremacy and take collective, anti-racist actions together. For members of this movement who are not BIPOC, it is crucial to recognize your biases, privileges, and identities. Acknowledge how these factors shape your perspective and interactions. For members of the BIPOC community, remember that racism affects all of us, but the impact varies based on social, educational and economic class. Your experiences may differ from those you support, and it’s important to recognize that while racism is a major issue, classism is also deeply intertwined.There are poor

people from all backgrounds, but being Black and poor is often particularly vilified and scrutinized. To genuinely support the people you are working with, you must embrace and invest in them in ways that may be unfamiliar to you. This means going beyond acknowledging their struggles to actively working to uplift and empower them.

● Center movement leaders who have lived experience of involuntary family separation by the Family Policing System. The Family Policing System cannot be dismantled without the expertise and insight of victims and survivors of the Family Policing System. Organizations committed to the abolition of family policing, including legal service organizations and philanthropic organizations, must materially support the organizing, research, and general advocacy efforts of directly impacted movement leaders without pressuring or requiring that these movement leaders compromise their radical political vision. Material support includes financial support and investment, capacity building, operational support.