8 minute read

CURRICULUM DESIGN

COULD CURRICULUM DESIGN BE AS SIMPLE AS ABC?

A curriculum design process known as ABC is helping classroom teachers review and plan more balanced online learning activities

Advertisement

Arena Blended Connected (ABC) curriculum design is a popular and well-respected process used in universities worldwide. Based on Professor Diana Laurillard’s research and designed and developed by University College London (UCL), the process guides educators to create or adapt sequences of learning modules to include online and blended elements. The process centres decisions around the type of learning that will take place rather than the technology that will be used.

In early 2020, the Computing at School (CAS) Research working group ran a series of training sessions to introduce teachers at primary and secondary schools to the process, as it had potential benefits to support the planning of learning during school closures. Working with the team at UCL, CAS Research developed training that presented the basics of ABC. A group of teachers then set to work trialling and adapting ABC to their schools’ needs.

ABC explained

ABC is based on the idea that there are six learning types (not to be confused with the now-debunked visual, auditory, and kinaesthetic learning styles): acquisition, investigation, discussion, collaboration, practice, and production. Educators review the type of learning that they would like to occur for a particular learning objective and design an activity to meet the need.

To help educators, the ABC method makes use of cards with suggestions of potential activities for each type. The potential activities are either a face-toface or an online option. As the computing teachers who were taking part in the ABC training started using the standard ABC cards, they soon realised that they needed to create their own sets for their own situations. Rather than having just a faceto-face and an online option, the group decided to include three online options. These were low-tech, mid-tech, and hightech: some teachers, and their students in some schools, had the skills and experience to use quite complex software, whereas in other situations, a more low-tech option was needed. Two primary teachers and two secondary teachers created sets of context-specific cards. Since then, a set of cards has also been created for delivering professional development.

Acquisition

Learning through acquisition is about what learners are listening to: hearing a lecture or podcast, reading from books or websites, or watching demos or videos.

Collaboration

Learning through collaboration embraces mainly discussion, practice, and production. Building on investigations and acquisition, it is about taking part in the process of knowledge building itself.

Discussion

Discussion requires learners to articulate their ideas and questions, and to challenge and respond to the ideas and questions from the teacher and/or their peers.

Investigation

Investigation encourages learners to take an active and exploratory approach to learning, to search for and evaluate a range of new information and ideas.

Practice

Practice enables knowledge to be applied in context. The learner modifies actions according to the task, and uses feedback to improve. Feedback may come from selfreflection, peers or the teacher, or from activity outcomes.

Production

Production is how the teacher motivates learners to consolidate what they have learnt by articulating their current conceptual understanding and reflecting on how they used it in practice.

Uses and challenges

The computing teachers who trialled ABC found the cards were a great way to help them and their colleagues plan for remote teaching. The cards have been used for quick reviews of current planning and to help develop new activities.

ABC has been used both by individual teachers to review their lessons, and by groups of teachers. In one school, the cards have been very popular across the whole school, and in another context, they are being used to support professional development for teachers across many schools. Some of the teachers have also used the ABC process for reviewing other subjects, including English and maths. In several primary settings, both specialist and generalist teachers have started to use cards. Teachers have used them not only to work out remote activities, but also to help them flip between remote and in-school delivery.

When developing the cards, teachers audited the content to be delivered and the resources that were usually used. The process focused them on thinking about alternative pedagogies. Approaches such as flipped learning were encouraged, moving away from an emphasis on passive learning (acquisition) through watching videos. Some teachers also reported that the process

AN EXAMPLE OF AN ABC CARD

Creator of card: Matthew Wimpenny-Smith Date created: 19 May 2020 Context (e.g. phase, subject, school): Primary Key Stage 2

Card name: Practice

Current activity

Worksheet-based task is photocopied and handed out in class

Low-tech

Worksheet is converted to digital format and emailed to learner. Learner prints and completes worksheets, then photographs or scans and emails back.

Prep time: quick Feedback time: slow

Alternative activities

Mid-tech

Worksheet converted to editable file and then posted on Google Classroom as one copy per child, or on Seesaw app. Learner completes digitally via keyboard or digital inking.

Prep time: some initially Feedback time: quick and all digital

High-tech

Worksheet becomes Google Form or other web-based activity for the learner to complete, for example interactive Seesaw activity.

Prep time: high initially Feedback time: could be very fast through self-marking

linked nicely with other frameworks for integrating technology in the classroom, such as the SAMR (Substitution, Augmentation, Modification, and Redefinition) model and the TPACK (Technological Pedagogical Content Knowledge) model.

Teachers who trialled ABC noted that those schools who had already implemented a standardised approach to remote learning (such as using Google Classroom, Microsoft Teams, etc.) were at a great advantage. However, ABC can also help schools that are new to remote teaching. Sets of ABC cards have been created for different technology options, and these can be shared, giving less experienced teachers a menu of ideas to select from.

One of the main benefits of the ABC approach is that it allows for the development of remote teaching that isn’t just centred around acquisition, production, and the recall of information and facts, but can expand into collaboration, investigation, and discussion. ABC particularly highlights where learning is passive, and also supports teachers to include assessment.

Embedding formative and summative assessment is a significant challenge in designing remote education. Often, quite high-tech options are needed to provide timely feedback to pupils. Learning platforms such as Google Classroom can be used for online marking. Rubrics can be set up and shared with pupils, for self-assessment, questions asked in live lessons, and quizzes used for asynchronous learning. Teachers have found that ABC has helped them tackle the assessment challenge by pinpointing potential strategies and opportunities for introducing assessment.

Other challenges to introducing ABC have been not about the process itself, but more about the contexts for learners and schools. One such challenge has been the range of pupils’ access to technology, while another involves safeguarding restrictions. Some schools found their pupils had to share devices with siblings or parents who were working from home, or that they only had access to a phone or tablet device in the evenings. The low-tech, mid-tech, and high-tech options on the cards helped teachers to begin to address these technical and timing issues.

However, to know what low-tech, midtech, and high-tech would look like in context, teachers needed to ask families what devices would be available to pupils, and when. It would therefore be useful, as part of the ABC process, to include a first step of auditing the devices available to your pupils. The audit needs to be done before you start your cards. Similarly, you also need to take into account the devices and platforms available to teachers, and their level of expertise.

Further challenges for the introduction of ABC are those of CPD and time. Teachers need training and time to enable them to develop these cards in preparation for the next period of remote education. In one school, senior management was concerned about how long the process would take, and the additional teacher workload. However, the teacher trialling the process is looking at how ABC can be integrated into PPA time once training has been delivered.

Taking it further and training in ABC

You can read about the original ABC process at helloworld.cc/abc; to find out how it has been adapted to our current computing school context, visit helloworld. cc/abc_cas. There, you can find a resource describing ABC, and sets of example cards, along with templates to create your own sets. A set of resources to share the ABC process with teachers is also available for CAS members at helloworld.cc/casinabox. Please contact Jane Waite (@janewaite) if you would like more information about using ABC in schools.

JANE WAITE, MATTHEW WIMPENNY-SMITH, CLAIRE BUCKLER, CALVIN ROBINSON & NIC HUGHES

MAKE CONCRETE

34 CULTURALLY RELEVANT

PEDAGOGY 36 LEARNING THROUGH MAKING 38 SCRATCHMATHS: INTEGRATING

COMPUTING AND MATHEMATICS 40 SCRATCH ENCORE: A CULTURALLY RELEVANT SCRATCH CURRICULUM 41 “ENGINEERS MAKE THINGS

THAT HELP PEOPLE” 42 DON’T TOUCH THE PLUGS OR BREAK ANYTHING!

Many of the ideas that pupils will encounter in computing are abstract and complex, and need to be illustrated using concrete examples and activities. Bringing these abstract concepts to life with realworld contextualised examples, and connecting them to other subjects, will help pupils assimilate new ideas into their existing understanding.

There are many ways in which you might make an abstract concept more concrete. One example that computing teachers may be familiar with is the use of unplugged activities, in which you take a computing concept and explore it in a noncomputing context. You can also make use of analogies and storytelling to help connect a new concept with familiar experiences and comparable examples.

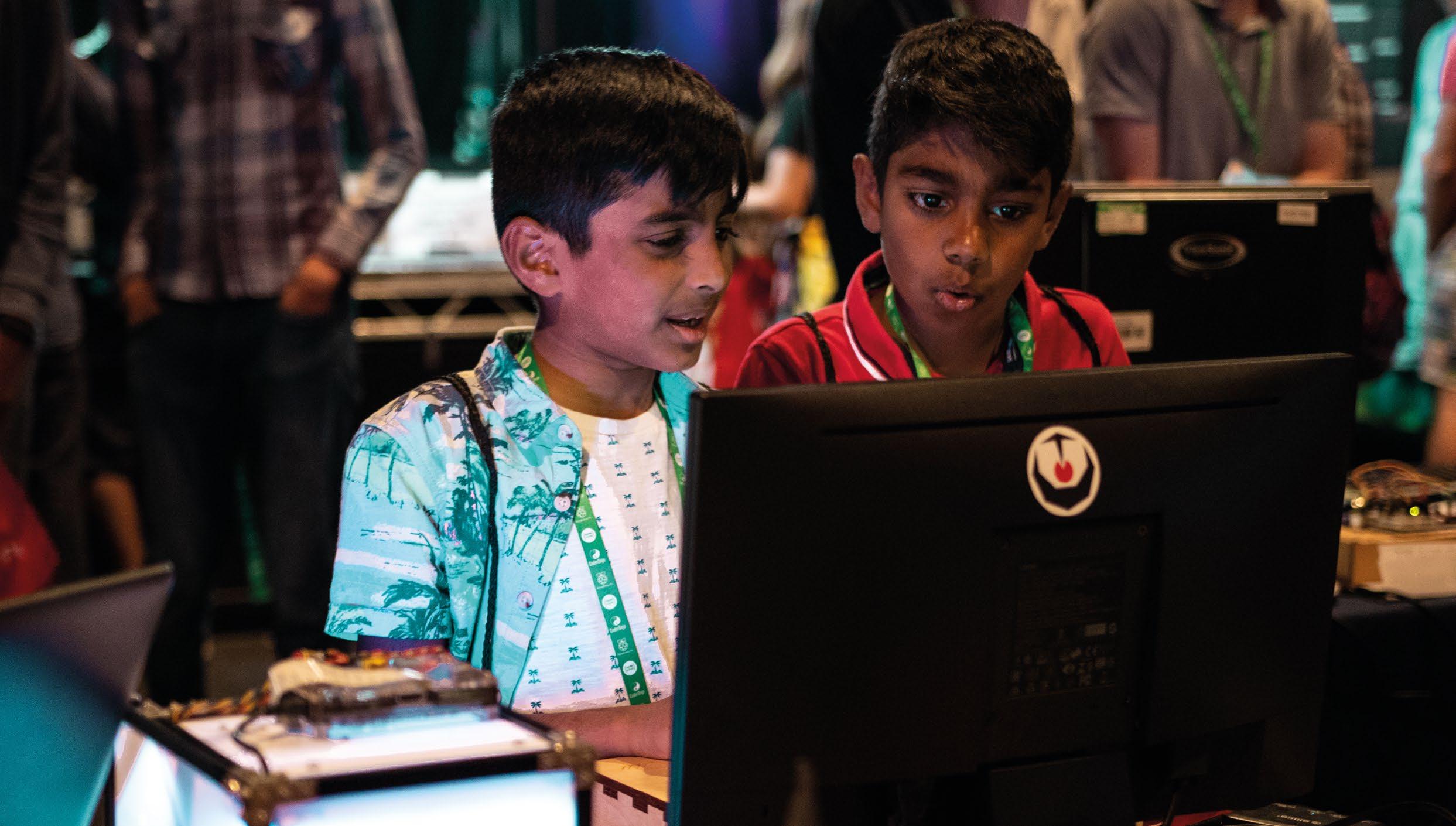

When considering concrete examples or providing context, you should reflect on the diversity of experience and culture of your learners. Use this knowledge of your learners to help you to deliver culturally responsive learning experiences.

IN THIS SECTION, YOU WILL FIND:

■ What the research says: culturally relevant pedagogy ■ What the research says: learning through making ■ What the research says: integrating computing and maths ■ What the research says: a culturally relevant Scratch curriculum ■ Cultivating engineering skills ■ Hands-on learning to break down abstract concepts