Every day after school, my father would turn to the news on ABC. As a kid, I only wanted to watch cartoons and sitcoms, but my father had other plans. He believed it was important for my brother and me to hear the stories of our community. This inadvertently led me to want to pursue journalism years later. My father always believed I was destined for greatness. He would claim there was something special about me that would launch me into a life that he never achieved but hoped for his kids to have reached. I am now a first-generation Black woman studying journalism at one of the best programs in the country in a top 10 institution.

Unfortunately, my father will never see this dream come to fruition as he passed away in the spring of this year. I tell this story not to bring sadness to this issue and work created, but to echo the power we wield in shaping the future. My father was never a journalist, but he knew from when I was a child that I had a talent for storytelling. When we think of visionaries, we have to go beyond the people advancing our culture currently; we have to honor those who set the precedent in which we ground our work and stories. My father’s story was cut short but that doesn’t mean his dream of my future ends early. I would not be in this position without his constant work to ensure my future was brighter than his. Our future as a community is a testament to all of those who came before us. A testament to all of those who couldn’t come into the future with us to ensure the life we live now is better than theirs ever was. As visionaries, our stories and art start with the work of our ancestors. We’re just the ones who take them to new heights and push our culture forward.

I was my father’s visionary and because of this, I dedicate this issue to my father. The beginning of my story was authored with the help of his love and teachings. My future success will be the epilogue of a story he always dreamed of but could never finish writing.

Viva Nepal, Raven WilliamsWhat defines a visionary? This is a question that we as a staff have grappled with as we approached every piece in this magazine. According to Merriam-Webster, a visionary is “one having unusual foresight and imagination” or “one whose ideas or projects are impractical.” How can we apply this to our lives here at Northwestern? When I think of a visionary, I tend to think of the prominent figures in history books or the icons of the present day. How can the noble title of a visionary relate to my comparatively boring life as a college student?

As we began cultivating the content for this issue, the answer to this question became abundantly clear: Black people have a legacy of being visionaries without necessarily trying. From the development of music genres like jazz and rock and roll, to the influence of Black fashion movements to mainstream trends, to the direct translation of Black vernacular into the slang of Gen Z, Black people have a way of constantly being ahead of the curve. Despite our struggles, we continue to have the audacity to let our innovation and excellence shine, inspiring the world with our resilience and determination.

This issue honors the history of the long line of Black visionaries who laid the groundwork and propelled us to be able to envision further progress. As Black students at Northwestern, we are the product of the Bursar’s Takeover, whose visionary legacy lived on this quarter through the establishment of the Gaza Solidarity Encampment at Deering Meadow. This issue would not be here without the visionary founding of the FMO weekly newsletter, “The Black Board,” in 1971. The subsequent re-foundings of BlackBoard over the years inspired the magazine’s most recent revitalization.

As a sophomore who entered Northwestern while BlackBoard was on hiatus, it was a learning curve managing the intricacies of this publication as the Online Editor-in-Chief. However, I and the rest of the BlackBoard staff embodied the definition of a visionary this year. With our imaginative collective vision through articles, photoshoots, social media posts, and more, we have successfully reaffirmed BlackBoard’s role as an essential platform and outlet for Northwestern’s Black community. I could not be prouder to facilitate the magazine’s first print issue in two years. I hope you enjoy “The Visionary Issue.”

Love, Devin Wilkes

Writers: Dallas Thurman, Gena Jones, Sophia A. Gutierrez, Khyla Bussey, Madison Morgan, Danielle Adekogbe, Stacey Pierre, Devin Wilkes, Hannah Ajogbeje

Designers: Ariana Mason, Josephine White, Khyla

Bussey, Yas’lyn Mohammed, Aida Belay, Stacey

Pierre, Rachel Smith, Breindel Cadja, Sophia A. Gutierrez, Theresa Harrison-Attobrah

Co-Editor in Chief: Devin Wilkes

Co-Editor in Chief: Raven Williams

Assistant Editors: Mariam Fofana and Gena Jones

Creative Director: Josephine White

Photo Editor: Joyin Akinola

Social Media Directors: Hannah Ajogbeje and Riley Morris

Managing & Finance Director: Eden Moore

WRITTEN BY Dallas Thurman

@blackboardmag

Everyone knows the feeling of tasting a watered-down drink or an underseasoned meal. This same feeling is carried over into social media whenever a trend previously established in the Black community becomes viral and is socially accepted after being whitewashed. The appropriation of these trends removes the creator’s artistry and innovation and leaves little room for them to receive credit. Historically, Black culture has often been adopted without the proper recognition or understanding of the people behind the culture. Who are the real faces and visionaries behind some of our favorite moments and trends in pop culture?

Everybody should know what Black Twitter is. It is one of the most entertaining yet scary spaces that you can stumble upon. As a collective, Black Twitter commentates on topics that reflect the Black experience. The community has played a huge role in mainstreaming many things like cancel culture and social change. However, one of its greatest influences is the integration of slang from AAVE, African American Vernacular English, with everyday language use. Words and phrases like “Tea,” “Pressed,” “Bruh,” “Ate,” and “Period” are sure to be heard in any conversation among avid internet users. These words weren’t founded on Black Twitter, but they have taken over so many people’s vocabulary, resulting in AAVE slang being used by everyone.

The popularization of AAVE comes with a price as white or non-Black people tend to misuse and overuse it. Black people use this slang to feel more comfortable while talking with each other and it helps to foster culture

within the Black community. When Black people use AAVE, it is fun and natural because we have grown up around the language. When white or non-Black people try to use AAVE it sounds forced, watered down, and is taken out of context. For example, the phrase “crash out” is making rounds on TikTok, and many white or non-Black people are misusing and overusing it at any chance they can get. To “crash out” is to go insane in response to something and is typically used in situations where that response is violent. Many are using it in the context of crashing out after failing a test or fumbling a situationship which is incorrect.

The whitewashing of AAVE is frustrating because Black people are often criticized and condemned for using slang because they’re speaking “improper” or sounding uneducated. Now, it is trendy to use AAVE, a slang that has been given a negative connotation, resulting in many Black people learning to code-switch to not seem out of place in non-Black spaces. White and non-Black people are seen as cool and trendy because it is now socially acceptable to use AAVE. However, when Black people used it, it was unacceptable because it didn’t have the stamp of approval from the white majority.

As Kansas City Chief’s tight end, Travis Kelce grew in popularity during Superbowl LVIII, kids began to go to the barbershop requesting a “Travis Kelce,” which is just a buzz cut fade. This sparked controversy across social media platforms as the haircut has always been popular in the Black community. According to Ebony Magazine, the hairstyle originated in the U.S. military around the ‘40s and ‘50s due to strict grooming standards. This look was then revamped as a hi-top fade by Black barbers in the mid-80s, which became a staple in hip-hop culture. Rappers like the Fresh Prince, Queen Latifah, and DJ Jazzy Jeff influenced its flair until the second coming of the original style’s more rigid, tapered look in the 2010s.

The issue with the “Travis Kelce” isn’t people wanting to try new styles; it’s about the lack of appreciation for the culture that the hairstyle is a part of.

blackboardmagnu

People didn’t even make an effort to do research or at least think about the story behind the haircut. They went straight to assuming that Kelce originated and invented the look. Many Black people have been getting this haircut for generations, and that has been appropriated and socially accepted because a famous white man wore it. However, the blame is not fully on Kelce, as he denies inventing the hairstyle and wants nothing to do with people claiming that he did.

blackboardmagnu

If you were on TikTok during quarantine, then you’ve watched or learned the “Renegade” dance. The dance was first created by Jalaiah Harmon and was posted to her Funimate and Instagram accounts. It was then brought over to TikTok by another creator, changing some of the original dance moves and not tagging Jalaiah as the owner of the dance. Eventually, Charli D’Amelio danced, and it went viral. This wasn’t the first time a white creator had taken credit for a dance. The lack of credit became controversial, and Charli finally gave Jalaiah credit for the “Renegade” dance and even met up with her to do the original dance together.

Jalaiah could have had the fame and reassurance that people know she owns the “Renegade” dance. This situation is unfair because it plays on power dynamics and systemic biases that project and push white creators to the top of social media. Charli had the power to give her credit at an earlier time or possibly even from the beginning, but Jalaiah’s dance had to be whitewashed and appropriated before it could go viral.

In 2022, Hailey Bieber received backlash from Black and Latina women accusing her of cultural appropriation for her viral lip routine. Her “brownie glazed lips” consisted of her using dark lip liner and clear lip gloss. This lip combo is not new. It has been popular amongst Black and Latina women since the ‘80s and ‘90s. The style was invented in response to the lack of darker lip liner shades for melanated women. Women would use cheaper lip liners to achieve boldness and definition for their lips. During that time, the style choice was considered “ghetto” resulting in Black and Latina women feeling excluded, underrepresented, and overlooked in the common beauty standard. This didn’t last long though. Hailey Bieber wasn’t the only white woman who claimed the lip liner and lip gloss combo to be their own without any credit given to its history. This rediscovery of the style turned into the “Clean Girl” trend where people would wear slick back buns, lip liner and lip gloss, and other “clean girl makeup.” All it took was for a white woman to reclaim the style for it to go viral with non-Brown women. It is not seen as ghetto anymore but aesthetic. On a Black and Brown body, it was condemned but on a white body, it is now accepted and praised. This phenomenon adds to the fact that non-white women struggle to be accepted as the beauty standard and are still fighting for representation in the beauty industry.

The film industry has a color problem.

While early innovators helped to liven the screens of twentieth-century classics like Gone with the Wind and The Wizard of Oz using technicolor, the industry remains historically underdeveloped when it comes to getting people of color both behind and in front of the camera.

A Hollywood Diversity report by UCLA showed that only 8% of theatrical film leads were Black in 2022. Beyond the screen, just 5.6% of theatrical film directors and a negligible 2.2% of screenwriters are Black.

While the statistics are a glaring indictment against barriers for Black creatives in Hollywood, the small share of our community that has broken into the film industry have had a mighty impact. Of the films that were helmed by Black creators, 90% feature casts that are majority actors of color.

We are an audacious people with revolutionary courage — Black minds have worked for centuries towards a more equal world for our community. But the Black radical vision doesn’t end with our activism: Black writers, producers, directors, and actors continually make waves in the political and creative realms through their work in film.

As an ode to the visionary achievements of the Black community on screen, here’s a list of just a few of the times Black filmmakers took up space on screen with grace, innovation, and unparalleled ingenuity.

In a time when D.W. Griffith’s silent film The Birth of a Nation (1915) was throwing fuel onto the fire of racial tensions in the United States, Oscar Micheaux was making history as the first major Black feature-filmmaker. In response to the early racially charged portrayals of the Civil War, slavery, and segregation, Micheaux began writing stories that would serve as a genesis for Black representation in film with The Homesteader (1919) and Within Our Gates (1929).

Black presence behind the camera dwindled after Micheaux’s breakthrough, as more and more of Black representation constituted early African American actors like Sidney Poitier, Dorothy Dandridge, and Harry Belafonte. We would ride the wave of their performances until we landed in the time of contemporary film, a conversation that can not be had without mentioning Black film champion and pioneer, Spike Lee.

Lee was among the first to be in conversation with rich, white film executives in the eighties and nineties, paving the way for more financially lucrative careers for people of color looking to enter the industry. With a budget of only $175,000 for his first feature film, She’s Gotta Have It (1986), he outperformed and amassed $7.1 million dollars in the box office. His success in creating movies that shed accurate light on Black stories and commented on their place in a white society set precedents for the kind of screenplays that could be funded and produced in the future.

Lee’s films would go on to inspire someone at the center of the new Black generation in film: Barry Jenkins. Jenkins’ work with Moonlight (2016) and If Beale Street Could Talk (2018) expand upon the conversations of Black sexuality and policing started by his predecessor, Spike Lee. Moonlight became the first film with an entirely Black cast and the first film with LGBTQ+ themes to win the Academy Award for Best Picture. A personal favorite of mine, Jenkins’ has cre-

WRITTENBY

Gena Jonesated a filmography with such cultural innovation in lighting, storywork, casting, symbolism, and the construction of a good pause that has creatively improved the discipline of film as a whole. In the Florida-born filmmaker’s work, we are able to see beyond a character and find poignant truths about Black youth, families, and social pressures. He’s golden.

While Key & Peele gave us laughter and dapping memes for eternity, the 2010s comedy also blessed us with a down-right visionary filmmaker in Jordan Peele. Get Out (2017), Us (2019), and Nope (2022) were all experimental moments in horror and thriller, that weaved crazy and suspenseful tropes with social criticism to birth innovative, yell-at-the-screen worthy plotlines. Peele’s work is the beginning of a breakdown to genre barriers for Black filmmakers and actors alike.

But there’s an important piece of this Black film history missing: women. In 2022, only 1.5 of every 10 theatrical film directors were women. Cue the record scratch.

That’s right. One and a half.

Despite audiences craving more diverse content, modern credit lists remain overwhelmingly white and male. Julie Dash was a part of the beginning of that change dating back to the seventies. Dash has been breaking down the intersectional impediments that kept Black women away from the director’s seat for decades now, directing, writing, and producing stories about Black women, their sexuality, and the impacts of generational trauma. Her 1991 film, Daughters of the Dust, made her the first Black woman to direct a nationally distributed feature film with a theatrical release.

In the landscape of modern Black filmmakers, we can’t neglect the name Ava DuVernay. The impact of her credits is endless: Selma (2014), When They See Us (2019), 13th (2016), A Wrinkle in Time (2018). Her catalog spans themes of the civil rights movement, hip-hop history, and fantastical stories about astral travel, that has broken into the worlds of streaming limited-series and television. DuVernay, who didn’t enter the industry until she was 32 years old, became the first Black woman to win Best Director at the Sundance Film Festival and one of the highest grossing African-American filmmakers of all time.

As for the future, the film industry has found a groundbreaking leader in Marsai Martin. The nineteen-year-old actress became the youngest executive producer in Hollywood history after pitching the film Little (2019) to studios when she was just 10 years old. Martin continues to produce and star in major projects, but with one catch.

“I don’t do no Black pain,” Martin told The Hollywood Reporter in a 2021 interview.

The 11-time NAACP Image award winner has made a commitment to not putting any more stories about Black pain and trauma on screen. She has a vital positive vision for the future of Black stories that even her older counterparts can aspire to. There is good to be seen in the lives of Black characters on screen, and Martin says it’s time to highlight that.

For what we were able to see and celebrate on this list, just know that there is more — much, much more that deserves your attention. Stream it, buy a ticket and sit in theaters, watch and support by any means necessary. Film, television, news, music: all of these are fundamental elements of media that allow us as Black creatives to reclaim our narratives and dictate the frameworks that exist around our community.

We can make it beautiful like Barry Jenkins, explore our history like Julie Dash, or create something happy like Marsai Martin. In film, we can bring to the screen the intricacies of our culture in daily life. If we continue to create like the examples we’ve seen, I have no doubt that the future of Black film will be just as visionary as the past.

Perhaps the most talked about, yet least understood word in the English language–yes, that four letter word: love.

It feels like an intrinsically radical act to write this word out on the page in the year 2024, as it seems I am writing to a generation that has given up on the concept. Whether you believe that it is a cookie-cutter myth, that an unrealistic and oppressive Hollywood media conglomerate indoctrinated the populus with, or you’re just a cynic without the need for a flowery stump speech – I resist. The formidable bell hooks opens her introduction to All About Love: New Visions resisting such cynicism, wisely acknowledging “ultimately, cynicism is the great mask of the disappointed and betrayed heart.” Disappointed and betrayed, are we? Indeed. Slouching towards what we’ve convinced ourselves to be “progress,” humanity is now reaping the consequences of such ideals in the form of a global identity crisis, complemented by generations of lovelessness.

The current global social order, inspired by our domineering and oppressive American exceptionalism, functions in the name of profit and power. The impact of this is devastating, as profits supersede human need. When human need is considered, it’s in the absence of the psychic and emotional, as that would slow the overall capitalist process too much. We are a generation of lovelessness, whether we know it or not.

At the end of the day, we are left with the promotion of that lovelessness on the macro level, as we can’t see past our enchantment with the current system that provides us the clothes on our backs and the food in our stomachs; “We are completely dependent on consumerism, the culture of the dollar, and the colossal powers that sustain our lifestyles,” brilliantly notes Gloria Anzaldua, in her piece The Path of Conocimiento. We sustain lovelessness on the micro level, as the system keeps us isolated, divided and pitted against one another in that same name of profit and power. This leads us towards worshiping the false Gods of money, power, superficial beauty, and intellect; all distractions from the energy of oneness which fills the space between us and shows us we’re not alone, that people matter, that love matters.

It is a unique trauma that women of color experience in their current and past lives. One needs not look further than the first chapter, “The Legacy of Slavery: Standards for a New Womanhood”, from Angela Y. Davis’, Women, Race and Class, or gain a basic understanding of colonial history and its impact on the formerly colonized today, to understand how these unique traumas came to be.

Perhaps that is why they have been the most brilliant orators and artists on the topic of love and the importance of it; they’ve had to live out those past and present lives under a socio-political order that has stripped them of their humanity in some or every capacity, and tried to keep them away from love. Those who tried, tried and failed, and these women have come to tell the story.

According to the self-described black, lesbian, mother, warrior, poet, Audre Lorde, there is “a resource within each of us that lies in a deeply female and spiritual plane, firmly rooted in the power of our unexpressed

or unrecognized feeling…we have been taught to suspect this resource, vilified, abused, and devalued within western society…the erotic is a measure between the beginnings of our sense of self and the chaos of our strongest feelings.”

This “resource” has become known as the “erotic”, an essential power source for women that has been historically devalued in western society, as noted by Lorde.

This devaluation is due to the capacity of the erotic to tap into a woman’s natural strength, so that they can rebel against oppression. Lorde elaborates on the characteristics and necessity of the erotic for women in her essay “The Uses of the Erotic: The Erotic as Power,” which is where the above quote is lifted from. Perhaps the most powerful function of the erotic according to Lorde lies in its ability to share “deeply any pursuit with another person. The sharing of joy, whether physical, emotional, psychic, or intellectual, forms a bridge between the sharers which can be the basis for understanding much of what is not shared between them, and lessens the threat of their difference.”

Lorde’s celebration of the erotic’s functionality to promote human connection, in the company of hooks’ and other scholars of color, is clearly rooted in a love ethic. These conceptions typically posit that love is worthy of mainstream attention when exploring interpersonal relationships, particularly those of the romantic variety. Although she recognizes and celebrates the importance and beauty of romantic love, Lorde argues that love is essential in forming a myriad of human relationships. Those human relationships help foster community, which is essential to dismantling oppression. For as she notes in the end of her essay,

“Recognizing the power of the erotic within our lives can give us the energy to pursue genuine change within our world, rather than merely settling for a shift of characters in the same weary drama. For not only do we touch our most profoundly creative source, but we do that which is female and self-affirming in the face of a racist, patriarchal, and anti-erotic society.”

It is my hope that the brief introduction this article might provide vis-a-vis the ingenuity of Black female scholars such as bell hooks, Audre Lorde and Angela Davis, can inspire and energize you to recognize the legitimacy and indispensable value, on a personal and collective basis, which love possesses. It is simultaneously my hope that their mighty word can showcase how insidious the culture of lovelessness, individualism, greed, insensitivity and cynicism, largely in the name of profit and power, is in the global community at this moment in time.

Radical love is a necessity. When I say radical love, I am referring to the advocacy aspect in the dictionary definition of the word radical. I am referring to a complete commitment to embodying a life of love, for the ultimate goal of creating positive change in our world. Going beyond affection, an aspect of love which is all too often emphasized in the media, living a life of radical love means to embody radical hope and radical empathy. Whether you find yourself at the negotiating table in the name of ceasing war, or at the pivotal point in your relationship with someone, love is omnipresent and necessary — and it will serve you and the world around you, if you let it.

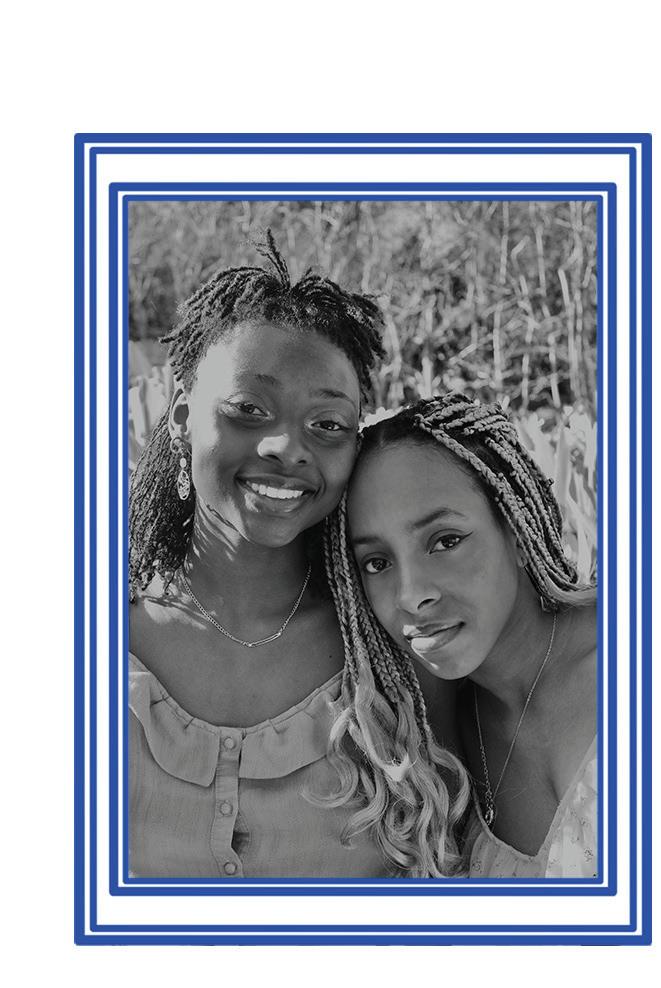

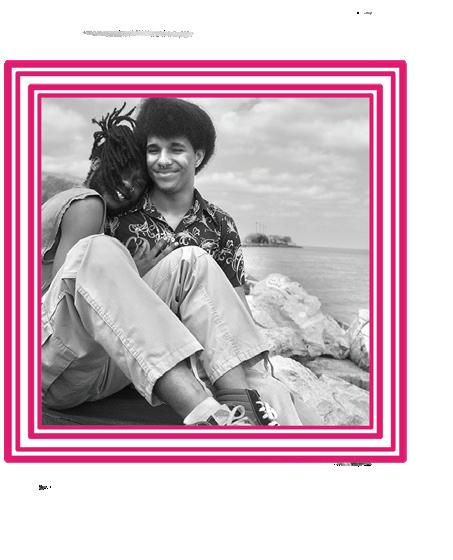

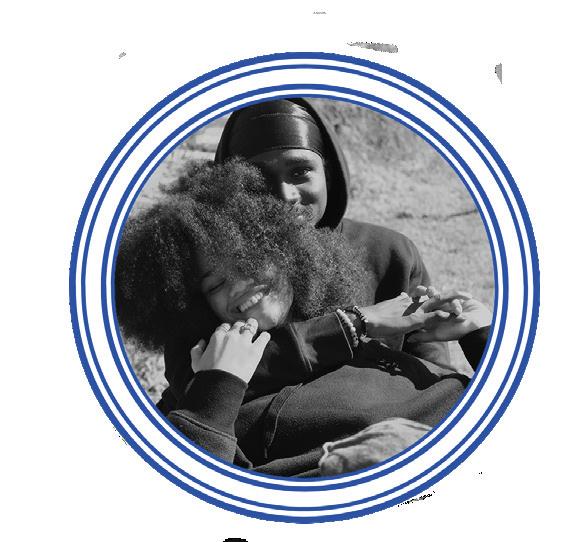

DESIGNED AND PHOTOGRAPHED BY Khyla Bussey

I

before the kiss of life caught in one another’s shadow the sunlight dipping under their sweet brown ears black stubble around his lips, mouth covered in gold caught in the shimmer, obsessed with the mouth her eyelids a sugary shoreline planes are echoing above the air but propped up on a brick wall her cocoa butter hand covered in youthful rings cups his chin her looking unlocking his lips smoother than jazz

a silhouette of clay bodies wrapped in clover ocean in the backdrop a sky of oranges & pinks staring into one another with crystallized eyes that say come to me at last, the waves have quieted against the pier and God has parted the clouds resembling an old photograph grandma preserves in the garage

III

lounging on a velvet black couch in the living room on an evening in winter awake & wearing nothing but skin legs inked in emblems of the past a girl who never dies and he rest at her feet, cuddled freeform locs tickling her inner thighs offering the belly a starshine warmth available only when Love Jones rolls silently in the background

IV

she’s walking down broadway in his green fitted cap threaded with he initials and a pink heart she’s all her own but ain’t no shame in holding and being held in saying thank you baby for bringing to life the wishes of nostalgic rhythm & blues thank you baby for creating moments to reminisce randomly when walking to the corner store on tuesday afternoon

V

aged, and dressed in white holding glasses of soft wine laughter has kept their faces young an alchemy of grays and silvers bloom from their scalps light of diamond sparks in her eyes at a glance of her cherish the day young black girls fulfill their childhood prayer their urges to wrap their hands around each other’s hips following the voice of Patti LaBelle playing on a old stereo reincarnating their midnight wedding

Cameron Freeman, a Weinberg senior from Los Angeles, turned an idea into a successful business by creating bedazzled Northwestern merchandise for school events. She felt deep down that her peers were worthy of more school spirit than what is offered by the average wildcat hoodie. Her skills vary, with a passion for fashion, pursuit of the entrepreneurship minor, IMC certificate and a major in English. As a former athlete, Freeman’s business, NUDAZZLE, has created a full circle moment as she is now making clothing for college sports games and more.

Q: What inspired you to start this business?

A: Northwestern is definitely a well-known school, more so for academics than sports, I’d say, but I realized with all my friends going to Michigan, USC, or big schools like that before coming to school as a freshman, they’re getting all this game day merchandise. A lot of the websites they’re shopping on for cuter, unique clothing didn’t have Northwestern as an option because it was a more niche school in relation to sports as far as that ra-ra aspect. So I saw this niche market since a lot of people were looking for cute game day clothes, and I loved making them and saw it as a side hustle at first.

Sophomore year is when I started it. I was in my apartment, and I’d get Hans tank tops and bedazzles and do everything by hand with simple designs, but people loved it. I sold maybe 20-something shirts at the time, and I thought it was great because I was just doing it for fun and to make some money. Junior year I went abroad, so it wasn’t really on my mind. Then, I came back to Evanston and really wanted to continue the business. I felt like I was at a place where I could really make it so much better. So I did some research, and I started to make things over this past summer before football season, and everybody loved it. It just started to become this thing people were talking about more than just my friends.

Q: What role did the Garage play in your business creation process?

A: This part is a bit blurry, but I believe at the end of my junior year I did a program where I was given a grant, mentorship and resources. The thing is, I actually had a slightly different idea, but it was still fashion-related and a business I wanted to create. Through that I got a lot of mentorship and met people, whether it was my peers or professors who could help me talk through my ideas and how to make it possible. You couldn’t get the grant unless you knew what you wanted to purchase and I wasn’t at that stage yet, so I didn’t use the money in the way I would now. But the Garage definitely helped me motivate myself to start my own business. I’m the type of person that when I dive into something I want to give it 110% and make sure it comes out well because at the end of the day, my name is on that. I haven’t used the Garage as much as I should have, but as it’s my last quarter here, I definitely plan on being there more often because I want to expand my business.

Q: Can you explain the creation process?

A: It’s come a long way. Initially I was hand making stencils with a hole puncher and cardboard. I would make a stencil of a paw print or whatever was popular, and then I’d one by one fill in every single hole with the stencils, then iron it on and fix things. That took a very long time and was not practical for a business. Now I do a combination of things. I focus more on the actual designing of the bedazzles and graphics, I actually get everything sourced and manufactured. I hand pick all the bedazzles and clothing items depending on popular trends or something me or my friends would like. I want to make sure that the

Q: So, on average, how much time is spent on the most simple versus complex piece?

A: Probably the most simple piece takes ten minutes, whereas complex could be about 30 minutes. I do everything on my own besides having my friends be nice enough to model. If I had help, it would definitely be a lot quicker, which is something I’m kind of looking into.

Q: What challenges do you have being an entrepreneur and fulltime student?

A: I think it’s hard. Even though I’m so grateful that I did really dive into it, there’s still so much I’d like to do for the business for it to be what I envision. I think a lot of people think it’s something great that they love, but there’s so many improvements I can make that I’m aware I can make, but at certain times, I don’t have the time, which can be frustrating. But in this last quarter I have a lighter class load than in the past, so I’m hoping to focus on it and make those changes. I’m excited for what’s to come in this next fall, a relaunch of sorts. I want to make a website and expand to other schools. People have reached out so I’ve done orders for places outside of NU. Off the top of my head, I can think of Syracuse and Michigan. I even did an order for a moms group doing a pickleball tournament.

Q: So if people reach out, you take custom orders?

A: If people reach out I definitely do custom orders. Every piece is unique since they are handmade, but there are some designs I’ll repeat.

Q: How do you currently promote your products, and how do you plan on doing so in the future?

A: I use Instagram. Right now, it’s kind of a convenience thing rather than my priority. What I mean by that is when I have so much free time, I’m really excited to do it and there might be ten things posted, but when I don’t, there’s a gap and maybe you haven’t seen posts in a little while. In the future I want to be more consistent about posting. Another part of my brand is having that sense of exclusivity. I promote the fact that no piece is exactly the same, and I think that makes people feel special. There are some designs that I can tell are popular, so I’ll make more, but since they’re done by hand, it’s not a perfect replica of any item before. Right now, people DM me when they want a piece, like Instagram Shop, although I don’t actually use Instagram Shop. In the future I plan on creating an official website.

Q: Since you plan on expanding your brand, would you change the name?

A: Yeah, I’d probably change it to UDAZZLE. Like University Dazzle, instead of just Northwestern.

Q: Would you ever consider selling your apparel to campus stores or doing a collaboration with an on-campus organization?

A: Definitely something I would be interested in, but I want to be careful as to how I establish the brand. Where I have the most hold right now is Northwestern because I’m a student here. However, I don’t want to box myself in, making it only a Northwestern brand. Eventually, I would love to sell my brand in campus stores nationwide. I see that as probably the

equivalent of having your products being sold in Target. But there’s also this dilemma I have just from a consumer mindset of having a product that’s hard to get. It’s something that I have to think about as I continue this journey.

Q: Have there been any significant milestones you’d like to highlight?

A: This is probably the fourth time I’ve been reached out to talk about NUDAZZLE, and the first time I was honestly shocked. When you have someone that you don’t know reaching out to you saying, ‘I heard about NUDAZZLE, can I write a piece on you and your business?’, it sounds so serious and that other people perceive it in a serious manner. The reactions I’ve gotten from other students and customers has really pushed me to keep going. The other day, I was walking to class and saw someone wearing a sweatshirt, and that felt so cool because I made it myself. I’m just proud that I did it. This interview highlighted that there’s so much growth and things I want to do with the business, but there’s also so many things that I’ve done. I wouldn’t be able to get to these next steps If hadn’t started somewhere.

Q: Any advice you’d give others with a dream who just need that push to go for it?

A: I’d definitely give the advice and listen to what everyone told me: just do it. If there’s something you’re passionate about, just start. It doesn’t have to be a full-fledged idea. Also, don’t be afraid to ask for help. I think I’m the type of person who takes a lot of pride in doing things by myself, but there’s nothing wrong with asking for help. And maybe you don’t like what you’re doing, but you’ll learn that from the experience, and in my eyes, any experience is a good experience.

Q: How is graduating going to impact the business?

A: I have established it very much as a Northwestern brand; however, most of my customers have been freshmen, so I feel like I’ve built a good base. I don’t even have that many followers on the Instagram page, but it spans wider than who actually follows me. I don’t think graduating is going to impact the business as much as I initially thought, but I guess we’ll just have to see—another trial-and-error experience.

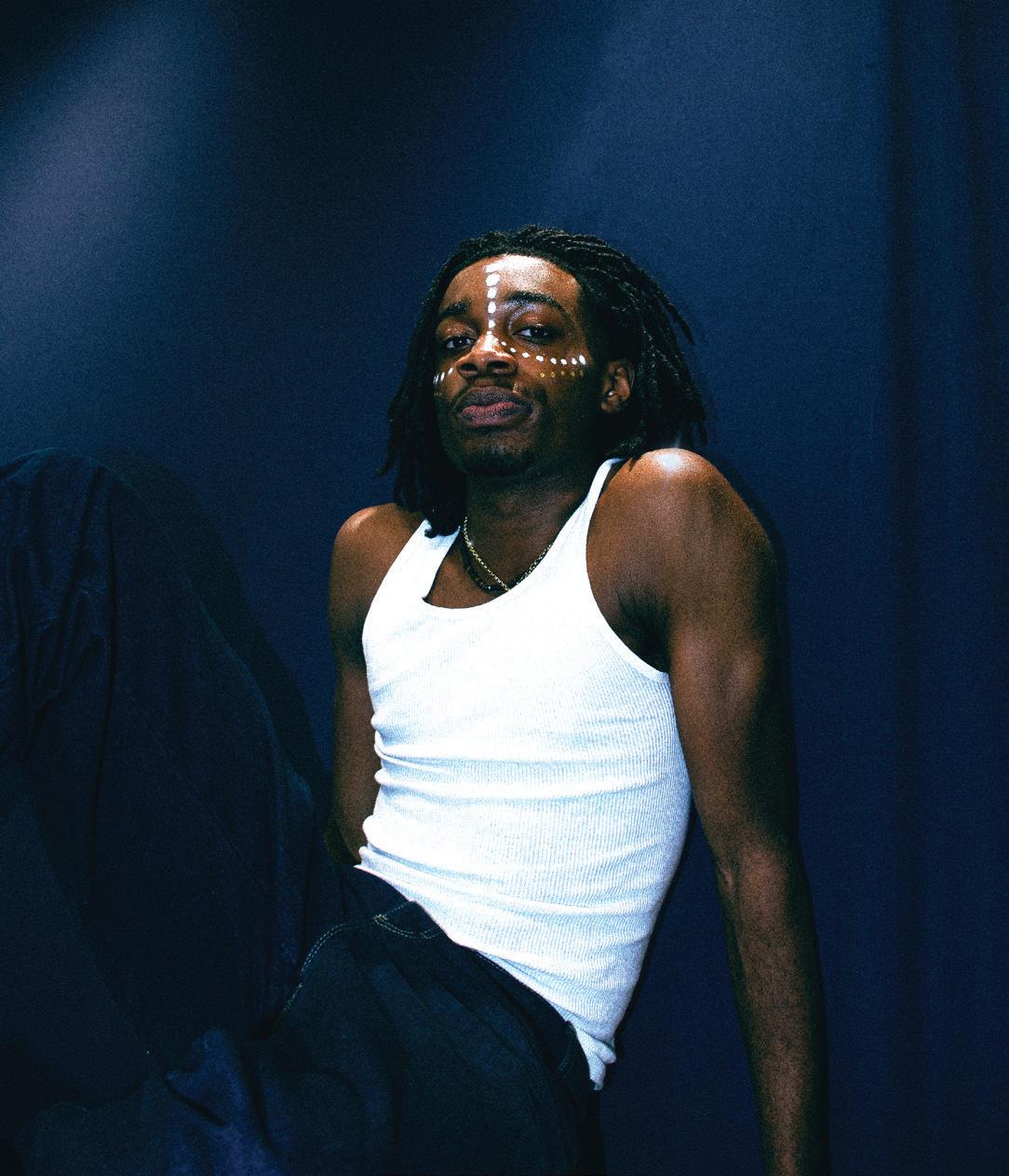

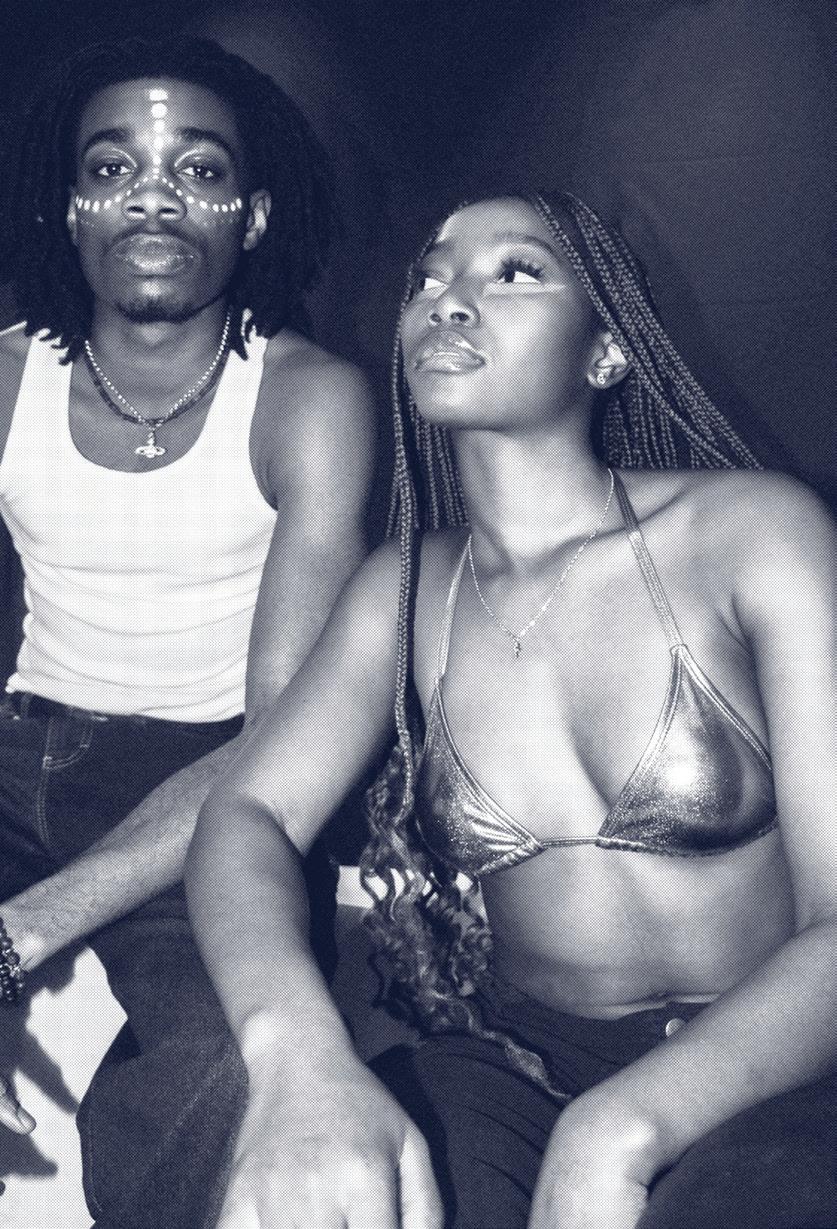

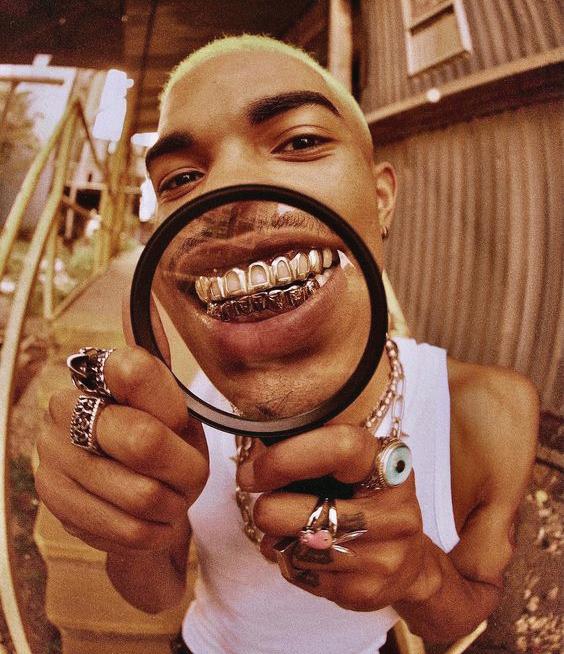

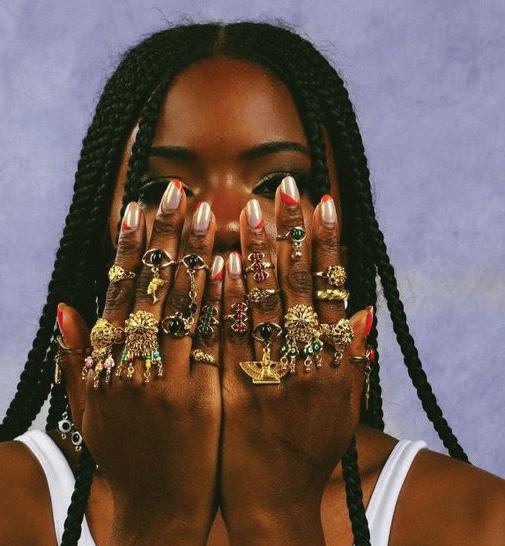

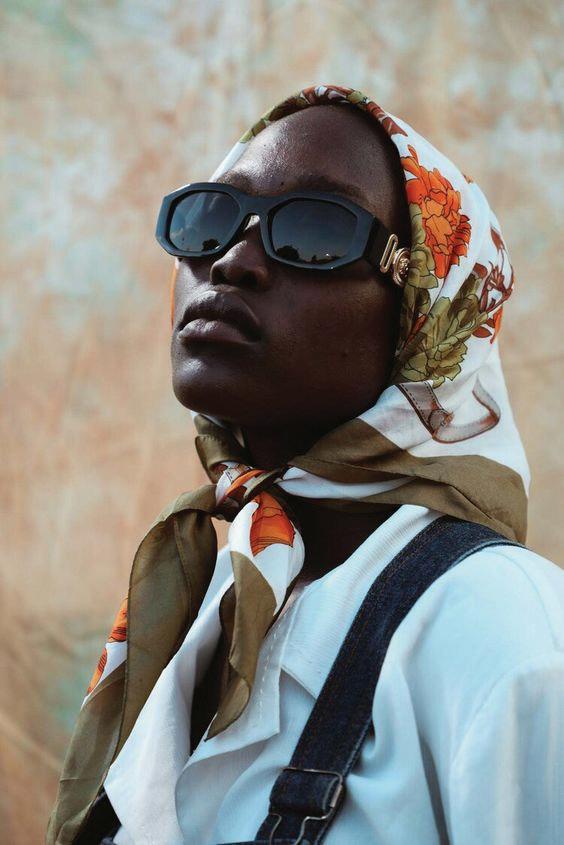

VISIONARY IS DEFINED AS SOMEONE WHO POSSESSES THE SUPERNATURAL ABILITY TO PREDICT THE FUTURE. GIVING LIGHT TO THE PAST, PRESENT, AND FUTURE PIVOTAL MOMENTS IN CULTURE WE WILL DIVE INTO HOW BLACK PEOPLE HAVE ALWAYS BEEN VISIONARIES. OUR FASHION, MUSIC, AND IDEAS HAVE ALWAYS BEEN AHEAD OF THE CURVE. SOCIETAL TRENDS HAVE ALWAYS BEEN CONTINGENT ON AN ASPECT OF BLACK CULTURE. BLACK IS THE BLUEPRINT BLACK IS THE FUTURE.

SHOT, EDITED AND DESIGNED BY JOYIN

DIRECTED, AKINOLA JOSEPHINE WHITE

BY

MODELED BY SOPHIA A. GUTIERREZ, DAMILOLA OLABANJI

MODELED BY TIMI OKE ELEBETEL NEGUSSE

MODELED

SOPHIA A. GUTIERREZ, DAVID DIOUF, NIGEL PRINCE, DAMILOLA OLABANJ, TIMI OKE, FEJIRO FELIX - OKPE, NAOL WORKU, NZUBE NWAFO

MODELED BY FEJIRO FELIX - OKPE

MODELED

SOPHIA A. GUTIERREZ, DAVID DIOUF, NIGEL PRINCE, DAMILOLA OLABANJ, TIMI OKE, FEJIRO FELIX - OKPE, NAOL WORKU, NZUBE NWAFO

MODELED BY FEJIRO FELIX - OKPE

MODELED BY TIMI OKE

MODELED BY NIGEL PRINCE, DAVID DIOUF, NZUBE NWAFO

MODELED BY AUTUMN VIVIANNA ROSE

MODELED BY TIMI OKE

MODELED BY NIGEL PRINCE, DAVID DIOUF, NZUBE NWAFO

MODELED BY AUTUMN VIVIANNA ROSE

Gweldon was the biggest city in southern Arizona. Unfortunately, that meant for its residents that any semblance of peace and quiet would be heavily disrupted until the Christmas rush was over.

That’s why these last few days were particularly surprising. Of course, early December had welcomed the regular influx of travelers, extended families, and nomadic specialty shops. But just around December 18th, the foot traffic and commerce hit an unusual pause.

The spike in inactivity continued until December 21st, 2020. Everything seemed especially normal, almost as if the city wasn’t four days away from the biggest holiday of the year. The temperature had lulled at the same 74.5 degrees for the past few days. The same kids spun their bikes around her cul-de-sac exactly at 4:50 p.m. The mailman dropped her package at the door at exactly 3:45 p.m. The unnatural synchronicity of the week had put her mind at an unfamiliar ease, making the day so much sweeter.

Shalom, who was humming to herself, peered outside. Except for the occasional straggler, the streets were void of activity. The only thing missing from the day was the smell of her mother’s cooking.

Shalom pranced over to her mother’s room, fully expecting to have to shake her mother awake from one of her ‘naps’.

Instead, when Shalom opened the door, fear immediately slivered through her body. Her mother, entranced in her episode of “Scandal,” had yet to notice that her body no longer made contact with the bed. A distracted eye would not have noticed that her mother’s body was just an inch too high over the bed, but Shalom, who had spent countless months caring for her mother, was especially cognizant of the state of her mother’s body.

Her mother had her eyes peeled to the TV screen, but it was the trembling of Shalom’s body reverberating through the squeaky door that finally caught the woman’s attention.

“Oh honey-” Shalom’s mother’s body quickly dropped to the bed, causing her to lose balance and knock her head against the bed frame.

“Mom?” Shalom rushed to her mother, whose expression confirmed her confusion.

“Sorry hon, I didn’t even notice I was off-balance-”

“No, Mom, you were...you were levitating!” Shalom said frantically.

Shalom’s mother released a deep hearty laugh, one that she rarely heard these days.

“You play too much, Sha Sha,” she said, leaving Shalom’s grasp and sitting up.

“But mom, you—” Shalom attempted.

“And you know I’m not broke, honey,” Shalom’s mom swiftly retorted.

That made Shalom go quiet. Shalom was overprotective when it came to her mother; after all, it was just just the two of them. That overprotection doubled after her mother’s diagnosis, tripled after her first surgery, and skyrocketed after her long journey with chemotherapy.

Her mother noticed the flat expression that took over Shalom’s face and chuckled slightly.

“Well, I know you didn’t come in here to disrupt ‘Scandal’ time. Bet you were looking for that famous stew, huh?”

Shalom’s mother said as she walked towards the bathroom door.

“I didn’t see any meat thawing, so I guess we’ll wait ‘til Chef Sha Sha does her part,” Shalom’s mother erupted into a heap of laughter.

Shalom, on the other hand, began frantically searching her phone for a tweet. It was her friend’s repost of a seemingly harmless tweet that had swept Black X up in its usual discourse.

SOURCE: X post from @lottidot

She quickly swiped out of the app to confirm today’s date. And there it was: 12/21/2020.

Shalom’s mouth was so agape at this point that it became noticeably sore. If she had seen what she had seen, and she was certain she had, then that could only mean that her mother had gotten her powers, complimentary of the Negro Solstice. And if what she was witnessing was her mother gaining a superhuman ability, then another thing was certain: she had to be next.

And if she was next, who else was next? Who else in Gweldon? Who else in the world?

Suddenly, the memes of Superman flying with an edit of Shaq on his body were less comical and all too real.

“I’m headed out!” Shalom screamed and bolted from her mother’s room.

She punched the FaceTime icon on her phone, frantically awaiting the call to pick as she forced her car key into the ignition. She was two miles from her house, when Chima finally picked up.

“Friend!!” Chima said, talking through a mouth full of rice.

“Chima,” Shalom said with an eerie tone.

“What? Girl, you know I have anxiety!” Chima said in a panic.

“The Negro Solstice, it’s real!” Shalom finally got out.

Chima was silent and contemplative for a few minutes. The silence crept into Shalom’s car as well. Shalom was about to repeat when Chima replied:

“I think so too?”

Shalom took her eyes from the road, staring into the phone.

““Well, I-I think I knew you’d call me? And not just in a ‘Shalom is calling me, as she usually does when she’s bored’ type of way, but in a ‘I knew you’d call me about this exact thing at—’” she glanced away from the phone, “‘—at 4:15 kind of way.’”

Chima continued.

“Last night, around 2:00 a.m., I had a vision that this exact call would happen. Except, I never got to the ‘Negro Solstice part,’ I thought it was an anxiety nightmare, but now that it’s playing out exactly how I saw it.. well.”

A smile creeped up on Shalom’s face.

“What?” Chima asked.

But Shalom was no longer listening. In fact, if not for the human mind’s ability to drive on auto-pilot, Shalom would’ve been eating a load of airbag and a ton of regret.

But instead, she was hyper-focused on her new reality, a notion she only toyed with in her freetime. The notion that being super-powered was no longer just an element of literary exposition.

Would she be able to read minds and finally figure out whether her uncle was lying about stealing her twenty-dollar bill in the sixth grade? Or would she conveniently hack into the U.S. reserves and pay reparations to every Black person in America with some super-powered genius?

Or maybe she could heal her mother completely. Restore the life back into her eyes and the sway back in her step.

Finally, freed from her daydream, Shalom fixed her eyes back towards Chima to speak, but before she could release a word, her world erupted in a brilliant display of colors.

DESIGNED BY Aida Belay

Lassos. Horses. Banners. Flags.

Beyoncé’s new country album, COWBOY CARTER, sent sounds of the South soaring across the United States.

Lead single “TEXAS HOLD ‘EM” earned the singer her first No.1 on the Hot Country Songs chart and her ninth Billboard Hot 100 No. 1 in the United States. The rest of the album followed suit in its success, surpassing nationwide virality after debuting at number four on the Billboard Global 200 as contributed by streamers in Belgium, Canada, Croatia, Iceland, and the United Kingdom. Worldwide, the single amassed more than 31.9 million streams and 48,000 downloads. Her venture outside of R&B attracted an immense amount of attention, but it hasn’t all been good.

Criticism and rejection towards Beyoncé seem to stem from the one incessantly-asked question since the album’s release in late March: “Why is Beyoncé making country music?”

To which, there is a simple answer: Why not?

Beyoncé Giselle Knowles-Carter is a Texas-born, American singer known for her hearty vocal ability. As an artist with decades of experience, she has produced classic hits throughout the rhythm & blues, soul, rap, hip-hop, dance, and electronic genres. Culturally, these musical genres harbor robust roots in communities across the Black diaspora, where its sounds are most celebrated. Recently, the association between race and genre has become a restriction on Black artists who wish to expand the boundaries of their musical expression.

Take the Grammys for example. The popular music awards ceremony has a history of neglect towards the work of Black artists who dare step outside the bounds of designated “Black” genres. We’ve seen this with Lil Nas X’s country-rap record “Old Town Road”, which a Billboard representative openly expressed as not, “...embrac[ing] enough elements of today’s country music to chart in its current version.”

Only two Black artists — Ray Charles in 2005, and the Black Eyed Peas in 2010 — have won the Grammy Award for Best Pop Vocal Album in recent history. With this pattern of exclusion in mind, the question, “Why is Beyoncé making country music?” begins to have less to do with the singer’s inability to contribute to the genre, and more to do with criticizing her audacity to join it.

Experimentation by Black artists has been a longstanding topic of discourse, often labeling Black artists who do venture outside of R&B and hip-hop as “whitewashed” or unfitting for their new musical

sound. Their willingness to explore is usually met by simple theft.

In 1955, Little Richard released his hit single, “Tutti Frutti”. On the 1956 National Pop list, the “genre-ambiguous” sensation charted in twenty-first place. When white artist Pat Boone released his own version of “Tutti Frutti”, it charted twelfth in the National Pop list and was considered plain rock by critics. In an interview with the Washington Post, Little Richard addressed those discrepancies in his reception by the music industry.

“They didn’t want me to be in the white guys’ way,” Little Richard expressed. “I felt I was pushed into a rhythm and blues corner to keep out of rockers’ way, because that’s where the money is.”

Despite historical impositions, Black artists have recently been given proper credit for their innovative impact on an array of musical genres. Black country singer Tracy Chapman recently received her due flowers for the 1988 hit single “Fast Car”. The song, covered by white country artist Luke Combs, started a domino effect of traction through the creation of two other covers: a reggae version by Wayne Wonder and a tropical-house version by Jonas Blue. The official music video garnered more than six million video streams, 28 million audio streams, and the official song more than 154 million U.S. audio streams on Apple Music and Spotify.

Chapman was surprised to even be celebrated by the predominatly white genre, stating to Billboard, “I never expected to find myself on the country charts, but I’m honored to be there.”

Black musical culture is vast and ever-changing, with newer artists putting a twist on their sonic historical roots by adding present-day dashes of artistic essence to modernize the sound. Artists like Rico Nasty reclaim rock and metal — originally created from African-American jazz, R&B, gospel, and country — by combining electric sounds with a trap and hip-hop flair. The indie/alternative realm has been melded with tints of R&B and soul by artists Frank Ocean, Janelle Monae, and Tyler, the Creator. English-born artist PinkPantheress has even become a sensation in the realm of bedroom pop.

Collectively, Black musical experimentation has been widely celebrated. Reception of Beyoncé’s country album has been exceptional in the Black community. Whatever tune you’re looking to give a listen, COWBOY CARTER’s got it on hand.

Get into a very sentimental mood with songs like “AMERIICAN REQUIEM” and “PROTECTOR”. If you’re feeling like busting a move on the dance floor, let your stereos blast the widely-loved “TEXAS HOLD ‘EM” or the risqué “RIIVERDANCE”. Slowly switch into an amped up theme with “SPAGHETTII”, which features elements of rap and country. Take a trip back in time while listening to Beyoncé’s fantastic covers of The Beatles and Dolly Parton as heard in “BLACKBIIRD” and “JOLENE”. It is contributions like Beyoncé’s that exemplify the untapped and multifaceted pool of Black talent that goes underappreciated by the music industry year after year.

COWBOY CARTER isn’t just a country album. It’s a landmark piece in Beyoncé’s discography that tells the world that Black musicians are not rookies when it comes to versatile musical expertise.

They are the experts.

The iconic sounds of rock, R&B, country, and gospel all started in the hidden corners of Black spaces, only to be unfairly claimed by non-Black artists. Reclamation of these genres is a must in order for the Black community to assert credibility, authority, and history within creative spaces as visionary pioneers.

DESIGNED BY Rachel Smith

Jumping into the ocean off the iconic Jaws Bridge. Day parties on Inkwell Beach. Illuminated nighttime strolls through the Gingerbread Houses. And, of course, did you really go to the Vineyard if you didn’t leave with a souvenir from the iconic Black Dog store? It’s almost like a secret language when it comes to the traditions of traveling to Martha’s Vineyard.

Since as early as the nineteenth century, this hatshaped island off the coast of Massachusetts has long resembled a coastal haven for the African-American elite. Every summer, typically around August, Black families flock to the ferries to enjoy a vacation. Many take the hours-long trip just to meet up with people from their local communities, whether it’s through renting a house with another family in their Jack and Jill chapter or organizing a reunion with their Divine Nine brothers and sorors. No matter where you’ve been all year, Martha’s Vineyard is a unique annual homecoming for Black people to enjoy tranquility, privacy, and expression.

The Vineyard is popularly the summer destination for the Obamas. Over the past century, it has welcomed visionaries like Martin Luther King, Jr., Lena Horne, Henry Louis Gates Jr., Spike Lee, and Oprah. Although the island is known for being a bougie getaway, this legacy has been in the making for hundreds of years.

in hotels, while a few purchased property and became business owners.

Some of the earliest Black entrepreneurs on Martha’s Vineyard were the Shearers. Charles (who was born into slavery) and Henrietta Shearer founded a laundry in Cottage City in 1903. They established Shearer Cottage in 1912, the first inn on the island catering to Black visitors. African Americans were otherwise unwelcome on the rest of the island, but the Shearers envisioned and provided a safe haven for the increasing visiting population. Shearer Cottage quickly became the prime destination for Black vacationers, swiftly welcoming icons of the Harlem Renaissance like actor Paul Robeson and composer Henry T. Burleigh. The couple’s daughters, granddaughters, and great-granddaughters have continued to manage it to this day.

The very first Black people to arrive at Martha’s Vineyard were enslaved, and the Black population remained small even after Massachusetts abolished slavery in 1783. The Second Great Awakening of the 1800s brought an influx of white and Black settlers, leading to the founding of Cottage City (which would later be known as Oak Bluffs). Most African Americans on the island worked as domestic servants or

By the mid-twentieth century, Oak Bluffs swarmed with middle-class and wealthy Black islanders and visitors. Though the destination resembled an escape from life on the mainland, the rampant racism that plagued America still infected the streets and beaches of the Vineyard. For example, the name of Inkwell Beach, the most popular beach among the Black community, was derogatorily assigned by white people in reference to beach-goers’ skin, which they compared to ink. Today, however, Black people have re-envisioned the Inkwell as a symbol of pride and a cultural core of Black life.

Martha’s Vineyard continues to epitomize an ideal location for African Americans to live freely, serving as an antithesis to the often all-consuming self-consciousness of being Black anywhere else in America. Frequently referred to as the “Black Hamptons,” the island also illustrates a picture of African American life that shows

that despite our history with violence and marginalization, our culture also includes traditions of affluence, happiness, and community.

Additionally, the island is a valuable landmark of Black intellectual activity. From as early as Frederick Douglass’ 1857 speeches at the First Congregational Church and the Edgartown Town Hall, prominent civil rights leaders have lectured in Oak Bluffs. More recently, events such as the Juneteenth Jubilee and the Martha’s Vineyard African American Film Festival annually attract Black visionaries to share their work and exchange ideas.

Martha’s Vineyard has enjoyed a sense of secrecy and exclusivity for decades, but the island streets become busier (and more expensive) each year. One result of this increasing popularity is the hit Bravo reality show Summer House: Martha’s Vineyard. The program features an all-Black cast of young professionals and entrepreneurs as they enjoy a summer vacation on the Vineyard, which they lovingly call “Martha.” While the show has its fair share of messy drama and antics, it is a necessary show case of youthful Black joy and freedom that contrasts common media portrayals of Black strife.

When I watch the reality show every Sunday, I am reminded of my own childhood vacations to Martha’s Vineyard. Some of my fondest memories are watching the sunset at Menemsha Beach and standing in line at midnight to get a treat from Back Door Donuts. As I got older, though, I used to groan at the thought of traveling over five hours just to spend time with the people who lived only a town over from me. What was it about coming all this way and hanging out with the same people from your hometown circles?

However, I now realize that Martha’s Vineyard carries a cer tain magic of belonging and peace that can rarely be achieved elsewhere. The reunions, functions, and celebrations enable us to be our most authentic and happiest selves. The Vineyard is a living embodiment of the beautiful legacy that Black visionaries can create.

American Author & Poet

Phillis Wheatley is the first African-American author of a published book of poetry. Born into slavery in Boston, she gained notability for publishing her poems, which was a remarkable feat at a time when enslaved Black people were widely illiterate. Wheatley’s achievements were used by abolitionists as examples of the intellect and literacy of Black people that helped to fuel the antislavery movement.

Surya Bonaly is the first figure skater to land a backflip on one foot during the 1998 Winter Olympics. The move that had never before been performed in competition and was subsequently banned after her demonstration.

“I

don’t know why... a lot of people through my life said, ‘No, you can’t. Don’t do that,’” Bonaly said in an interview at the Olympics,. “Well, listen. I will.” (Olympics)

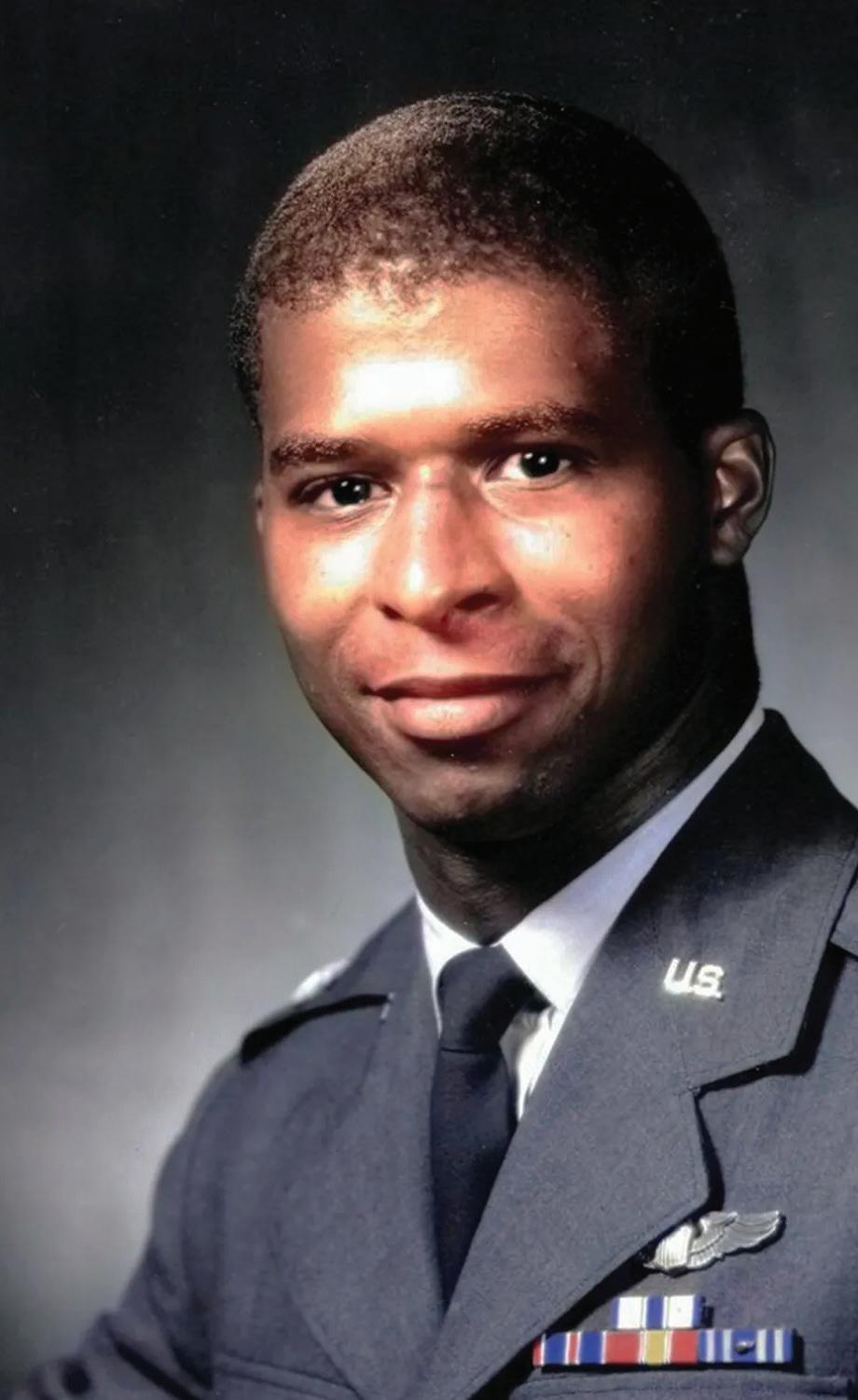

Robert Henry Lawrence was the first African-American astronaut to be selected by any national space program. Born and raised in Chicago, he was a highly accomplished pilot who graduated high school at 16 and got his bachelor’s degree at 20 years old from Bradley University. He received his PhD in physical chemistry, making him the only astronaut selected by the program with a doctorate. Lawrence was involved in the crucial development of the “flare maneuver,” one of NASA’s space shuttle landing techniques. He died in a crash in the Space Shuttle Program in 1967 and his name was largely forgotten under the Nixon administration’s cancellation of the Manned Orbiting Laboratory program

André Leon Talley is the first African-American creative director and editor of Vogue Magazine. He helped style Michelle Obama when she served as First Lady and mentored supermodel Naomi Campbell. He also led a Vanity Fair shoot called “Scarlett N’ The Hood,” which reimagined “Gone With the Wind” with Black protagonist. Talley is remembered for addressing the racism, elitism, and exclusivity of the fashion industry in a time when few dared to. American Fashion Journalist

Robert Bullard is regarded as the father of environmental justice for his work spanning across four decades, during which he united civil rights with environmentalism to pursue legal changes towards environmental justice. He conducted research in the 1970s around the Bean v. Southwestern Waste Management Corp lawsuit to understand if the placement of a landfill in a primarily Black community was a part of a larger pattern of environmental racism. Bullhard also authored 18 books and received recognition from various climate change organizations. American Environmental Justice & Academic

WRITTEN BY Hannah Ajogbeje

WRITTEN BY Hannah Ajogbeje

From being trilingual to loving fashion, student-athletes’ highlight reels can go far beyond 80-yard touchdowns. Studying at a top 10 university and playing for a Big Ten school sets the bar high for all of our student-athletes. However, being a Black student-athlete at Northwestern creates a nuanced challenge that many of our peers have to overcome along with academic obligations. Contrary to popular belief, being a Black student-athlete and a stereotypical “jock” don’t play well together when you’re on a Northwestern field.

“Any kid here who’s a Black student-athlete has to do well and I would even say over-perform in their spaces. Just because we are fighting,” said Christopher Thaggard, second-year soccer player.

Unfortunately, the rareness of non-athletic coverage of athletes continues to perpetuate a negative connotation and misunderstanding of athletes to our students. Some Northwestern athletes say they often feel they are not seen beyond their athletic talents.

“We are more than just an athlete,” said Miller, a notion that some collegiate athletes consistently express.

Outside of Walter Athletics Center, five students continue to bendsociety’s rules on what it really means to be a Black student-athlete.

Joe Himon is a second-year football player studying learning and organizational change (LOC) and entrepreneurship. At Northwestern, he serves as a member of Kappa Alpha Psi Fraternity Incorporated and Black Student Athlete Alliance (BSAA). Within BSSA, Himon interacts with Northwestern Black student-athletes to get them more engaged in the larger Northwestern community. He performs through volunteer work at surrounding schools and charity events. One of Himon’s main hobbies is reading.

“I like to read a lot of self help and motivational books, and I feel like that just keeps my mind going while I’m not thinking about school or football.”

Himon says his favorite book is Relentless by Tim Grover. The book follows the life of Kobe Bryant’s trainer, Tim Gover, and details the story of Bryant’s mentality on and off the court. Himon says the story inspired his mentality

Himon says outside of the facility, being courageous is a significant aspect of his student-athlete identity.

“In today’s world the system is set up for Black men to fail and I just feel like for me, I have to take take the courage in following my dreams and just doing everything that I love to do,” said Himon.

Kennedy Hill is a second-year volleyball player studying Environmental Policy and Legal Studies. Unlike others who started their sports in early childhood, Hill discovered her passion for volleyball at thirteen years old. Hill expressed her ambitions to build a life outside of volleyball and does not have the dreams to go pro like many athletes.

“I’d say [I’m] ambitious only because volleyball is a means to an end. I say that because I am working towards a goal that is outside of

volleyball. I feel like a lot of athletes want to go pro or keep playing but, I’m ready to get out when I graduate and want to be able to build my life after this without the weight of being on volleyball,” said Hill.

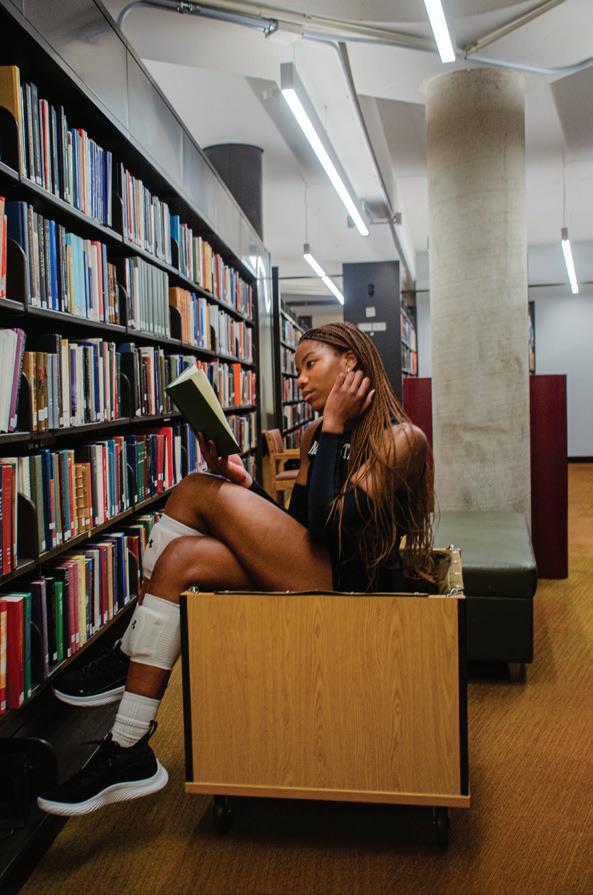

Outside the realm of volleyball, Hill finds a significant importance in cultivating a life apart from athletics. From recreational pottery, to hanging out with friends and reading for leisure, Hill creates a healthy student-athlete life balance.

“I feel like creating a very healthy balance is important. Like I choose not to do certain things with volleyball, if the team is going out I’ll choose to stay home,” said Hill. Just finding that balance with trying to make space for yourself alone outside of volleyball, and alone separate from friends is very important for me”

Hill expresses a sense of relaxation when she is separated from the day-today life of essentially working as an athlete.

“I find myself thriving when I’m alone. So, I like to just chill and make sure I just take in the chill time so that I’m ready to be alert when I have to basically work here.”

After college, Hill has aspirations to attend law school, and if not law school, she plans on doing something in relation to Environmental Policy.

“I prioritize my education over everything. Out of all the options I had I felt like coming here was the best because of the academics and also because of the Big Ten,” said Hill. “I felt like I was getting the best of both worlds on and off the field. I would be getting a great education while also maximizing my opportunities on the field playing at the highest level,” said Hill.

Christopher Thaggard is a second-year men’s soccer player studying LOC and developed a love for soccer at just four years old. He is deeply rooted within his Christian faith and expresses that through involvement in faith-based organizations like Athletes in Action (AIA). As a member of AIA, Thaggard joins other athletes to talk about Christ and their Christian beliefs.

“For soccer, my Christianity helps me remove my identity from the sport, that’s not all of who I am. If I get injured or a result does not go my way I understand it is not the end all be all,” said Thaggard. “My actual identity is in Christ so I don’t need to be that stressed out or so connected to the sport in terms of the outcomes,” said Thaggard.

AIA provides a gateway to build athletes at the highest level possible to honor God.

The club holds weekly meetings for members to discuss Christ and their beliefs. “Being a Christian helps me be a better person, and really take care of my relationships. Along with valuing my relationships outside the aspects of winning or losing.”

Along with his Christian faith, Thaggard expresses himself through minimalist fashion.

“I think throughout most of my life my self-expression has been through soccer and its always such a competitive environment. I feel like in fashion, you can express yourself without those types of pressures,” said Thaggard.

Brooke Miller is a second-year women’s soccer player studying journalism. Since the age of four, she began to play women’s soccer due to influence from her parents and has continued to play ever since. Outside of soccer, she enjoys podcasting, photography, and film editing.

“I like how you can capture emotions and how when you want something or see something a photograph can make you feel a certain type of way,” said Miller. “I think it’s cool to capture that human emotion or experience. So I think editing and putting it together is just cool [because] I like the final product.”

Miller exercises her leisure for podcasting through her soccer-related podcast, “Whiskers”. However, with the constraints of being an athlete, she rarely has the time to indulge in her hobbies.

Depending on the time of year, Miller’s soccer can take up as much as 20 hours per week alone.

Timi Oke is a first-year undecided football player with an interest in economics. The British-Nigerian athlete was raised in London and arrived on campus in January 2024. Although Oke is the newest recruit to the football program, He did not always have football in his playing cards.

Oke attended the NFL Academy, where he learned most of his football skills. From there, he gained opportunities to attend numerous football summer camps in America, and gained college recognition.

However, outside of picking up new sports, Oke has a vast array of talents. He is trilingual speaking English, Chinese, and Spanish. Yet, his most poignant interest is music.

At the age of five, he began to play piano in church due to influence from his mother. He continues to use music as a means to express his creativity.

I like music a lot. Listening to music and also justin my free time, music production. I used to do that back home a lot but I haven’t had time to do that here,” said Oke. “I just kind of like it because it allows you to use your creative skills and build something from scratch into a final piece. It’s kind of satisfying when you have an idea in your head and being able to hear it as a final product.”

Oke says he uses FL Studio to create lo-fi, hip-hop and jazz music.

As he closes out his first quarter as a Northwestern student-athle te, Oke says he learned many of

“The amount of people especially that I see on the team that like to read [is something] people wouldn’t know when you look at them. But they love to read in the locker room,” said Oke.

“I think as athletes we have a lot more to offer than just our sports. I just think more people need to realize that there will be a day where we won’t be playing a sport anymore,” said Himon.

Take off the jerseys and cleats and see our student-athletes for the proud, highly academic multi-faceted Northwestern students that they really are. Their jersey numbers is just one of the numerous qualities making their exuberant athletic and academic contributions to our community. Just because their jerseys say the same school, doesn’t mean they represent the same qualities.