A. Prelude

B. Defining Emotions

C. Evolution and Development

D. Exploring Emotion

E. Interdisciplinary Transfer

F. Methodology

G. Emotion-Based Strategy

H. Deepening Practice

A. Prelude

B. Defining Emotions

C. Evolution and Development

D. Exploring Emotion

E. Interdisciplinary Transfer

F. Methodology

G. Emotion-Based Strategy

H. Deepening Practice

Function is obligatory, emotion the masterstroke!

An intimate relationship between user and product is a further step toward a green future.

The emotional darkroom: Can someone turn on the f****** lights?!

Congratulations on your decision to purchase this highly emotional packet of methods, which contains 450,000 characters and weighs ca. 650 grams. As the authors, we hope to support you in unpacking this opus. To help you avoid the feeling of having purchased a ‘cat in a box,’ we take this opportunity to remind you of its main topics. Emotions, design, methods, and strategies. Four keywords that accurately circumscribe the contents of this book. In the first third of this volume, we guide you step by step into the topic and our methods. In the central section, following the tools, are the corresponding derivations and an interdisciplinary discussion. If you find yourself still wanting more, or have questions or suggestions, please get in touch!

For years now, we have been working very deliberately along the interface between emotion and design. It all began when we asked ourselves: Why do certain things speak to us (while others don’t)? Why do we feel compelled to pull a certain product off the shelf? We were not concerned with marketing tricks, but instead of the question: would it be possible to navigate the emotional impact of design in a targeted way? Our research into the design literature revealed that when it came to the investigation of systematic instruments and methodological solutions, we encountered a proverbial black hole. To explore it leads toward precise brand communication and target group appeal, as well as to an improved acceptance of design.

In 2010, our vision thrust out its first shoots with an essay on the topic of the “Impact of Early Childhood Conditioning on Product Design.” It received continuing nurturance from various expert interviews, and blossomed forth into a 304-page research project, finally attaining maturity as the strategic design office hoch E . Now, with this publication, a number of facets are revealed. Our research bug also impelled us to convey our practical experience and theoretical and methodological expertise to others as lecturers, as supervisors of degree theses, and as consultants at numerous seminars and workshops.

More than 7000 hours of analysis and research have culminated now in a set of scientifically grounded methods, and in unerring design. Through the specialized research foci of our agency, we are in a position to translate corporate values into comprehensible design alphabets, transforming them into a powerful competitive advantage. Psychology, neuromarketing, and design offer tangible discoveries that flow directly into our design work.

All of that and so much more provides the tailwind for our continuing preoccupation with the interface between emotion and design.

“If only it were possible, finally, to introduce a word into our language that did not segregate thought from emotion. I am truly fed up with always having to choose in favor of one and hence against the other. And how much unhappiness has arisen because people have also acted accordingly.”

— Hanna Johansen, Meier-Seethaler, 5Do you still remember the feeling of love at first sight? The unforgettable flirting? The fluttering sensation in your stomach? An awareness of simply wanting more? A relationship is born. With pet names, and a private history, a past and a future. Here, it’s not a question of the sparks that pass back and forth between lovers, but instead of those that are exchanged between an individual and a designed object. Exactly what happens here, and why? Every design has primary — and in many cases secondary — messages, which are conveyed to begin with through form, color, and materiality. With virtually all products, consumers expect its perceptual appearance to correspond to their personal expectations and desires. As a rule, beholders/consumers engage in minimal reflection concerning the impact of individual components and their causes — nor, for that matter, do most designers. To some extent, the design process proceeds intuitively, in reliance upon gut feelings. This can work, but may in fact not. If on the other hand, clarity is achieved about why certain forms have specific psychological effects, concerning the origins of such perceptions, and how these can be aroused subliminally, the result is a powerful design tool.

The secret code here is emotion. For the most part, emotional phenomena occur without conscious awareness. Our conscious emotions are only the tip of the iceberg. More than 80 percent of our daily decisions are guided by the subconscious.

By no means is it our intention to create an all-encompassing panacea — which would be impossible anyway, fortunately. The focus of this book is on the disaggregation of the emotional core of design. And in this spirit, we are opening the airlock of our laboratory to offer you exclusive inside views into a few of our test tubes.

What questions does this book pose?

· Which emotions are relevant to design?

· Can emotions and values of a brand be identified and designed in a focused way?

· Why are certain products perceived, for example, as intelligent, enduring, silly, or brilliant?

What does this book offer?

· It provides an understanding of what the emotions actually are.

· It provides insights into how design is networked with other disciplines.

· It contains the Emotion Grid® (basic version).

· It contains the Design Elements (basic version).

What does this book not offer?

· A rigid set of rules, to say nothing of a magic formula. This is neither possible nor desirable.

We have now sketched out some of the domains and facets within which the emotions have an impact on human life and sought to shed light on their potential existential significance for the individual. The emotions accompany us constantly, and they shape the most important decisions we make during our lifetimes. Can you conceive of a relationship that is utterly devoid of emotion? Even a marriage motivated primarily by financial or political considerations – where romance and trust play no role at all – contain an emotional component. And powerful emotions underlay even demands for pure objectivity – whether in the realm of interpersonal relationships or in design. Concealed behind them may be yearnings, a desire for reliability, or reticence and reserve.

When it comes to product design, the emotional aspect would appear to play a subordinate, almost incidental role. Our image of “emotions in three-dimensional design” seems rather indistinct and is often associated – albeit without justification – with kitsch, organic forms, or decoration.

Necessary before we turn toward the details and immerse ourselves more deeply in the material is an overview of the various disciplines that seek to come to terms with emotional life. What are the emotions? What distinguishes feelings or sentiments from moods or atmospheres?

This section presents certain positions, along with the highly varied definitions of the “emotions.” The focal areas are psychology, biology, philosophy, and design. Preoccupied with emotional life alongside these disciplines are neurologists, sociologists, a range of cultural disciplines, physiology, psychiatry, religion, and doubtless many more as well. Given the breadth of our topic, as signaled already by the sheer multiplicity of definitions, this chapter focuses on disciplines of relevance to design specifically.

Emo|ti|on, [from Old French esmovoir = to excite] an affective state of consciousness in which joy, sorrow, fear, hate, or the like, is experienced, as distinguished from cognitive and volitional states of consciousness [Collins Dictionary]

Neither in psychology nor in philosophy do we find a unified definition of the term “emotion.” It is evident, however, that psychology has increasingly turned its attention toward this topic in recent decades. According to Klaus Scherer, an emotion psychologist at the University of Geneva, we are now living, unquestionably, in the age of emotion. [cf. Kast 2010]

The content of philosophy is the interpretation and understanding of the world and human existence. Appealed to primarily in this context is rationality, which is often presented as the measure of all things. The following statement, however, is virtually unassailable: “An emotion is a kind of mental phenomenon.” [Wollheim 2001, 19]

In the history of philosophy, emotions are often referred to as affects (Lat. affectus: emotional excitation). Epicurus (341–270 BCE) already distinguished between the affects of pleasure and displeasure. Hedonism, which he founded, regards the avoidance of displeasure and the search for pleasure as the precondition for happiness and the good life.

The natural science of biology is concerned with the general laws governing life. The emphasis is on the peculiarities of individual life forms, their development, as well as their structuration, processes, and organization. The focus is not exclusively on human emotion and the processes associated with it, but with animal life as well.

In his book The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals, Charles Darwin provided an extensive analysis of these processes. Like psychology, a biological perspective of the emotions and feelings incorporates both psychological and physiological aspects.

“The feedback of the peripheral physiological and muscular expressions of feelings contributes to shaping the quality and intensity of emotional reactions (James/ Lange). Feedback from the peripheral effector organs (‘somatic markers’) is analyzed in the superior parietal cortex, and allows emotional perception without conscious registration of the triggering stimuli.” [Schmidt/Birbaumer, 725]

In other words: naturally enough, all of the emotional responses that are displayed by the body (facial expression, heartbeat, perspiration, hormone release, etc.) have an impact on emotional intensity. This means that through physical reactions, an emotion may become perceptible without the affected individual even being aware of its cause.

The emotions are not bound up with basic biological needs, and instead arise through assessments that are related to individual value or goal orientations. Nor do the emotions set rigid motoric behavioral routines into motion in a reflexive way.

[Rothmund/Eder, 684]

Stephan, which tasks and areas are you responsible for at Hilti?

Corporate product design, which is my area, refers to the designs of all of the products in the portfolio, whether physical or digital in nature.

Industrial design is the most essential component of this competence center, and also includes all ergonomic task areas. Also belonging to the area of responsibilities covered by my team are graphic elements and user interfaces, as well as all packaging solutions, such as the familiar red Hilti carrying case.

Basically, we are concerned with the total experience of our products, alongside their purely technical functioning. Meanwhile, we design all of the aspects of our products that are perceptible in sensory terms by users.

Let’s focus on the physical product. What appeals to users most compellingly?

The product’s dependability in conjunction with its performance, which is multifaceted. It’s not just a question of mechanical performance, but also of the haptically perceptible ergonomic performance and the intuitive, self-explanatory quality of the forms. We develop our products in a way that allows us to offer our target group solutions that increase productivity and we succeed here only once we have achieved a deep understanding of users. In designing solutions systems, we think everything through down to the smallest detail for each individual product. As a component that can be evaluated rationally, this central focus of our design tasks is an essential factor in purchas-

ing decisions, and in the long-term satisfaction of our target group.

But I’m also convinced that alongside such rational criteria, enthusiasm for our products is also driven by emotional traits. The theme “joy of use” is becoming increasingly important; here, it’s not just a question of the emotional charging of the design language, but instead of the interplay of all perceptible facets through which a product is experienced. Seen in this way, designers not only shape a functional form, but also act as mediators between the other disciplines that contribute to defining the product.

From your perspective, what is the value of the topic of emotion in the design of Hilti equipment?

As I said, emotionality is an important area. The credo of our enterprise is not just to deliver satisfaction to our customer community, but to fill them with enthusiasm in the long-term as well. That’s an ambitious goal, and it’s not always easy to achieve, but it does propel us onward in each individual project. Like everyone, our target group perceives things in emotional terms, and evaluates them emotionally rather than rationally, on the basis of their culture, their life experiences, or their individual tastes. So it would be negligent, in trying to achieve this goal, not to integrate such emotional patterns into the design of our products.

For me, emotion means first taking the client’s essential nature absolutely seriously, and designing products in such a way that they do max-

For me, emotion means first taking the client’s essential nature absolutely seriously, and designing products in such a way that they do maximum justice to his or her personality traits.

Stephan Niehaus is an engineer and a trained industrial designer. After various positions on the agency side, Niehaus moved to Hilti AG in 2003. As head of corporate design, he is responsible for the brand’s overall design identity.

imum justice to his or her personality traits. A demolition hammer, for example, which is used in construction by professionals, can’t look like a kitchen blender; it has to look like a work tool to do justice to its status. On the other hand, it’s a question of identifying forms of expression in the product language that tell you something about its inherent properties: quality, load-bearing capacity, performance, and, in some cases, precision. This is not at all trivial when we consider how people from diverse cultural milieus respond to forms, proportions, dimensions, and different technologies, as well as what their expectations might be.

But emotion is also evoked by the brand-appropriate character of a design language, when this is recognized. The brand image is an enormously important driver for the interpretation of design, and we are pleased that our image is extremely positive within the global building industry.

What challenges arise through this multifacetedness of design?

Unsurprisingly, the various departments have divergent expectations of design, which they of course want to see addressed in the design process. There are objectives arising from the areas of technology, marketing, production, brand design, and quality control, but also from product design itself. Our developmental processes are clearly structured, and they embed the design process, with its creative and implementation-oriented phases, very effectively. That’s extremely important if the above-mentioned objectives are to be considered holistically, and are to be introduced deliberately at just the right moment. I regard it as important not only to define these processes clearly, but to implement them transparently.

This means that discussions can be conducted in a far more goal-directed and productive way, and, above all, stable decisions arrived at. Oftentimes, that is not as simple in practice as it is in theory. Undoubtedly, our colleagues in the adjacent departments have considerable expertise in their areas, and hence considerable influence on the design concept, as well as on the final design. For me, designers are also always communicators. I need someone who not only has a good command of CAD systems, and can guide creativity in the right direction, but who can also mediate, and is in a position to convey the right solution.

At the start, you referred to values like dependability and performance. How do you make these values become visible through design?

Our brand color — red — helps with security. We not only employ it in a way that is brand-relevant, but also in connection with the use of red to express power, which is also why it is used for the design of the center areas of the main bodies of our equipment. An additional point is the 'outof-one-piece’ style of our tools. This can be seen, for example, with the classical combi-hammer, where the motor, gear unit, and grip components form a coherent unity, a self-contained, contoured body. Associatively, the device makes an

Emotions are reactivated, hereditarily determined, and genetically guided reaction patterns, often present only in a rudimentary or vestigial form, which guarantee, as dispositions, the survival of the species (for example, Darwin, Plutchik).

Emotions are consciousness-moderated representations (feedback, information) of bodily (peripheral or central) processes, or more simply: emotions are sensations of physical changes (for example, James/Lange).

Emotions are the contents of consciousness that arise as products of physiological activation (excitation) and related cognitive interpretations, and that conceivably emerge only during interruptions of a course of action (for example, Schachter/Singer, Mandler).

Emotions are condition-based, evaluative reactions, or judgments that can be regarded as the products of cognitive activities (for example, Lazarus).

Emotions are regulators of adaptive behavior that serve their function by signaling inadequate adaptation as ‘disturbances,’ hence initiating enhanced adaptation (for example, Reykowski, Scherer, Weinrich, and to some extent Freud).

Emotions are experiential, instinct-driven conditions of an individual that vary between ‘pleasure’ and ‘displeasure,’ and that always also reflect conflictual biographical experiences, specific societal expectations, the milieu of the individual’s upbringing, and attempts to satisfy individual needs (psychoanalysis).

Emotions are experiential states that mirror, in particular, needs and experiences from early interpersonal interactions and relationships (recent psychoanalysis).

Emotions are learned motivational states of readiness for experience and action, or ‘secondary’ needs that influence behavior (neo-behaviorist behavioral learning theories; to some extent Izard; Tomkins).

Emotions are experiences (or actualized experiences or anticipations) of confrontation with a specific environment, with its expectations, constraints, and possibilities. The individual’s experiences and attitudes, for example, helplessness as a consequence of constricting living situations, or anxiety as a consequence of unfathomable living situations (sociological approaches, individual theories from clinical psychology, and ‘critical’ psychology, for example, Holz-Osterkamp 1976).

chologist Jean Piaget, for example, says nothing about whether basic emotions exist, and what they might be – in contrast to Izard, who proceeds from the assumption that innate neuronal excitation patterns exist for ten fundamental and discrete emotions:

· Interest: attentive, focused, alert

· Suffering: downcast, sorrowful, dispirited

· Disgust: aversion, nausea, revulsion

· Joy: delighted, happy, cheerful

· Anger: incensed, wrathful, furious

· Surprise: amazed, perplexed, astonished

· Shame / shyness: shy, timid, reserved

· Fear: fearful, anxious, apprehensive

· Disdain: contemptuous, derisive, scornful

· Guilt: remorseful, guilt-ridden, blameworthy

[Rost 2001, 52]

The focus here is on the three theories of evolutionary psychology based on Charles Darwin, William McDougall, and Robert Plutchik. They are deemed critical because first, these define certain basic emotions, and secondly, they address the question: What purpose do the emotions serve? Moreover, they take facial expression into account. This aspect is particularly important for a deeper analysis that is of relevance to design.

From the perspective of evolutionary theory, the emotions are “Dispositions (preparedness for experience and action) that guide behavior in an adaptive direction. All answers respond to the question: How do the emotions help people to cope with ‘survival’ tasks?” [Ulich, 105] This point of view has faced repeated criticism from the ranks of the emotion researchers. It is difficult to provide evidence for the assertion that all of the emotions are based on an evolutionary purpose. Indisputably, however, certain emotions – among them fright and anxiety – possess a life-sustaining function in many situations.

Darwin’s basic hypothesis is that certain forms of expressive behavior in humans and animals exist only in order to ensure the survival of the species. The emotions are therefore governed by specific evolutionary-biological purposes, for example protection, intimidation, or preparation for conflict. [cf. Ulich, 102]

Darwin had already concluded that there exist innate forms of expression for a number of the emotions, a so to speak genetic–biological basic program. In his studies of

As a rule, feelings of shame emerge in the context of emotional relationships, or when things do not proceed as expected. In contrast to sorrow or disappointment (often associated with shame), this emotion has a personal-moral component that relates to self-image. Shame appears in the context of actions that are irreconcilable with one’s self-image.

"Shame occurs typically, if not always, in the context of an emotional relationship. (…) Shame motivates the desire to hide, to disappear. Shame can also produce a feeling of ineptness, incapability, and a feeling of not belonging. Shame can be a powerful force for conformity. (…) Shame avoidance can foster immediate self-corrective behavior as well as sustained programs of self-improvement." [Izard, 92]

When someone feels ashamed, they are uncomfortable in their own skin. An averted gaze, a lowered head, a sudden stutter, a bright red face, and increased perspiration are the most conspicuous indicators of shame.

Emotions that are intimately entangled with shame include fear, revulsion, anger, joy, and interest. The last-named emotion is strongly connected with sexuality in particular. Here, it is the close, intimate bond that is strengthened, since sex and mutual exposure have a reinforcing effect.

Aside from this, shame does not seem to offer any positive utility and is generally associated with unpleasant feelings. In our relations with others, in particular, shame tends to inhibit social communication and body language.

Yet shame also heightens sensitivity. The increased attentiveness it brings about promotes self-reflection, self-criticism, and receptiveness to criticism from others. Such capacities are essential, particularly in relation to social community.

If shame occurs in situations where others suffer harm or are disadvantaged, it frequently leads to feelings of guilt: "Guilt occurs in situations in which one feels personally responsible. (…) In guilt people have a strong feeling of 'not being right' with the person or persons they have wronged. (…) Intense and chronic guilt can cripple the individual psychologically, but guilt may be the basis for personal-social responsibility and the motive to avoid guilt may heighten one’s sense of personal responsibility." [Izard, 92]

Like anxiety, the emotion shame can also impel us to avoid unpleasant situations or to exercise caution. In this regard, shame has a strongly preventive character. We attempt to avoid situations that can lead to shame, striving instead to emphasize our strengths. “To avoid the shame of ineptness the individual is motivated to find his strength and develop it.” [Izard, 400]

In this sense, the avoidance of shame can serve as a motivation to advance the development of mental, physical, and social capacities. It therefore has strongly motivational and experiential traits that are of special relevance to the individual and to society. [cf. Izard, 401–2 ff.]

In most instances, disgust is associated with the visual, gustatory, or olfactory senses, but the tactile or acoustic senses may play a role as well. Occasionally, we may perceive surfaces or certain sounds as disgusting, the squeaking of chalk on a chalkboard, for example. A decline in moral standards or the transgression of moral boundaries may also elicit similar reactions. “Physical or psychological deterioration tends to elicit disgust. When disgusted one feels as though one has a bad taste in one’s mouth, and in intense disgust one may feel as if one is ‘sick at the stomach.’ Disgust combined with anger may motivate destructive behavior, since anger can motivate ‘attack’ and disgust the desire to ‘get rid of.’” [Izard, 89]

In such cases, disgust is often combined with negative emotions such as annoyance or anxiety. Pure disgust, then, does not really exist, since it is always mixed with overtones of other emotions, and these define the main tendency. When we are revolted by other people, because we reject their attitudes or values, for example, we are actually dealing with contempt.

Contempt often occurs with anger or disgust or with both. These three emotions have been termed the “hostility triad.” (…) Even today, the situation in which the individual has a need to feel superior (stronger, more intelligent, more civilized) may lead to some degree of contempt. One of the dangers of contempt is that it is a ‘cold’ emotion, one that tends to depersonalize the individual or group held in contempt. [Izard, 89–90]

The emotion disgust has many facets. Disgust may also trigger revulsion or shuddering, but paradoxically, it may also involve attraction. Here, we could almost speak of fascination, coupled with excitation and curiosity. Concerning this paradoxical sensation of fascination, which may be associated with this emotion, William Miller writes: “[Disgust] (…) has an allure, a fascination, which is manifest in the difficulty of averting our eyes from gory accidents (…), or in the attraction of horror films. (…) Our own snot, feces, and urine are contaminating and disgusting to us, [but we are] (…) fascinated in and curious about them (…) we look at our creations more often than we admit (…) how common it is for people to check their Kleenex after blowing their nose.”

[Ekman, 192]

Generally speaking, disgust is experienced as negative and unwelcome. This becomes particularly clear when we think of putrefaction or spoiled food products. Our immediate response is “a feeling of aversion. The taste of something you want to spit out, even the thought of eating something distasteful can make you disgusted.”

[Ekman, 189]

But not just inedible food products elicit such reactions; our own bodily fluids and excreta trigger displeasure to an equal degree, provoking reactions of revulsion: “(Paul) Rozin found that the most potent, universal triggers are bodily products: feces, vomit, urine, mucus, and blood.” [Ekman, 191]

Viewed in evolutionary terms, disgust has a primarily warning function and prompts us to avoid certain things.

SURPRISE

· Raised eyebrows

· Wide-opened eyes

· Wide-opened mouth

· Emphatic frowning

· Bright eyes (pleasant surprise)

· The mouth forms a smile (pleasant surprise)

[cf. Darwin, 1201 ff.]

JOY (laughter, high spirits, cheerfulness)

· Wide-opened mouth

· The corners of the mouth drawn back and up

· Raising of the upper lip

· Contraction of the upper and lower circular muscles of the eyes

· Contraction of the eyelids

· Wrinkling below the eyes

· Cheeks drawn upward

· Bright, shining eyes

· Raised head

· Smooth appearing eyebrows

[cf. Darwin, 801 ff.]

ANGER (rage, hate, indignation)

· Bared teeth

· B aring of the canine tooth on one half of the face

· Blushing or paling

· Grinding of teeth

· Marked frowning

· Eyebrows drawn down at the ends

· Wide-opened eyes

· Staring, shining eyes

· Lips drawn back

· Flared nostrils [cf. Darwin, 1001 ff.]

SHAME

· Reddening of the face

· Humble look [cf. Darwin, 1301 ff.]

· Making oneself small

· Self-touching

· Hands slapping in front of the face

· Embarrassed smile

· Covering oneself

INTEREST

· Dilation of the pupils

· Opened, shining eyes

· Inviting look

· Corners of the mouth raised slightly

DISGUST (contempt, disdain)

· Raising of the outer parts of the upper lip

· Exposure of the canine tooth on one half of the face

· Furrowed eyebrows

· Emphatic frowning

· Oblique gaze

· Sneering laughter

· Averting the gaze

· Slightly upturned nose

· Sniffing

· Raised upper lip

· Wide-opened mouth

· Corners of the mouth drawn down [cf. Darwin, 1101 ff.]

FEAR (fright, horror)

Contraction of the muscles around the eyes

· At times, firmly closed eyes

· Frowning

· Wide-opened mouth, the lips drawn back

· Exposed teeth and gums

· Eyebrows drawn downward

· Furrowing around the eyes

· Crosswise furrows between the eyebrows

· Reddened eyes

· Wavy furrows on the forehead

· Down-drooping corners of the mouth

· Extension of the facial features [cf. Darwin, 1201 ff.]

SORROW (suffering, weeping, dejection, despair)

· Contraction of the muscles around the eyes

· At times, firmly closed eyes

· Frowning

· Wide-opened mouth, lips drawn back

· Exposed teeth and gums

· Eyebrows drawn downward

· Furrowing around the eyes

· Crosswise furrows between the eyebrows

· Reddened eyes

· Wavy furrows on the forehead

· Down-drooping corners of the mouth

· Extension of the facial features [cf. Darwin, 701 ff.]

Up to the present, the design sector has had no unified or well-founded method for visualizing and communicating the connection between emotional expression and form, color, and materiality – a black hole that was ignored for decades and simply passed over with the slogan “form follows function.” If we are to stay “on course,” an important step will be to fill this gap. Moreover, it would provide designers with an industry-appropriate basis for argumentation when advocating and explaining their inventions to other participants in the product development process. To be sure, emotions are always found in a certain context and are never arbitrary. The same is true with the corresponding design parameters. But more on this later.

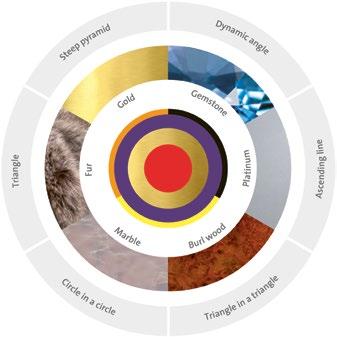

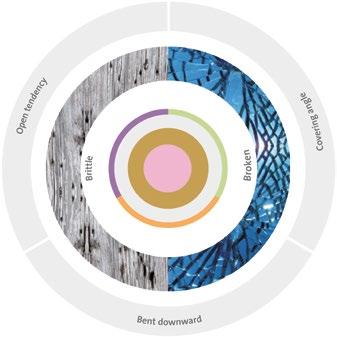

The most important models of emotion, influences from neuromarketing, and industry-appropriate briefing glossaries are only some of the ingredients that make the Emotion Grid® into a genuinely practicable tool for designers. Mapped here are values, along with sub- and basic emotions. This makes it possible to define zones, and in a subsequent step, communicate these with the design parameters form, color, and material. The first hurdle that must be overcome in the design process is to resolve the question: In which emotional direction should the product navigate? The definition of the zones proceeds on the basis of target groups, brands, and product lines. For the conceptualization, these determinations represent an important basis for arriving at an agreement between marketing, corporate management, and the designer. But let us begin by explaining the structure and functioning of the Emotion Grid®.

The Grid is divided into two basic areas that contain the emotional conditions pleasure (white area) and displeasure (gray area). The ten basic emotions (red/gray) are distributed in the two areas together with their surrounding secondary emotions (red/gray contours). As with additive color mixture, this produces zones with emotional focal points. The emotions and secondary emotions are supplemented by values (blue contours); these are exclusively positive in significance.

Values are an important component of brands and briefings. The values and secondary emotions positioned here make no claim to completeness; they facilitate the improved location of the emotions.

The basic emotions themselves are clustered around the three so-called emotional axes:

1. the axis of fascination , with the basic emotions interest and surprise

2. the axis of drive, with desire, anger, and fear

3. the axis of harmony, with trust

If a product is to sell, the design must awaken desire. Desire, meanwhile, is strongly dependent upon the expectations of the prospective purchaser and may be awakened, for example, through interest or trust. This is not to be confused with objects that themselves emanate desire and are often characterized by a strong impulse toward dominance. Desire, therefore, can be expressed in design terms, or conversely, it can be elicited in the beholder.

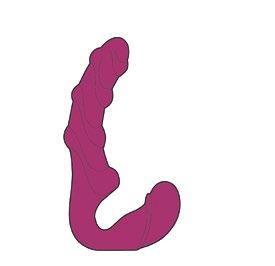

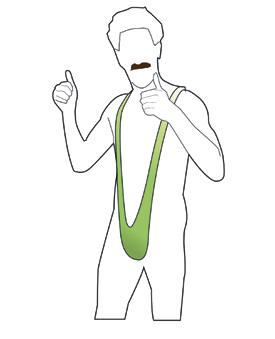

Certain elements, such as the asymmetric curves and the eye symbol, which can be associated with all of the pleasurable emotions – regardless of the primary design language involved – are particularly representative of desire. As innate trigger stimuli, they are closely associated with things we perceive as beautiful. Beauty awakens desire and is often found behind it as a motive. Hardly by accident, desire is by nature a highly demanding and purposeful emotion, and it is expressed clearly through emphatically angular forms, which may at times tend toward the crystalline. In individual instances, circular or rounded elements may embody desire as well. Paradoxically, this may switch over into its counterpole, an amorphous sensuousness.

The color world of desire is already clearly verifiable through a historical retrospective. The focus of attention here – alongside clear or unusual color worlds, often those reserved for the aristocracy – are those derived from precious metals such as gold. With the palette of materials, we encounter a similar background. Characteristic here are precious woods, rare metals, and sought-after furs. The placement of the emotion desire on the axis of drives on the Emotion Grid® makes its character quite clear. The secondary emotions yearning, longing, and craving indicate the ascendancy of the sensual. With arrogance, pride, and greed, and the values rivalry, authority, egoism, the aggressive character of this emotion becomes evident.

BMW M1 study: freeform surfaces and accentuated linearity are merged | dynamic, striving directionality toward the radiator grille symbolizes speed | the hard edges and soft surfaces are consistent with the current BMW design language | consistent wedge shape | the “liquid orange” paint color creates a red-gold shimmer

PuraVida by Hansgrohe: the cylindrical structure with the bent surfaces form a dynamic triangular shape | flowing form and precise circumferential edges form a clear field of tension between desire and trust | the materiality and collaboration are unusual and luxurious

The emotion shame lies in the displeasure area of the Emotion Grid® and is located in immediate proximity to terms such as intimacy, shyness, and embarrassment. The proximity to disgust suggests that a low threshold separates these two emotions from one another.

Expressions of shame, however, cannot be linked directly with specific forms. In addition to facial expression, shame is displayed through uncertainty and shielding. Shame in relation to an event, an action, another person, or a product is strongly dependent upon the respective circumstances. The purchase of a certain object, for example, may result in delight and act as a stimulus on the keyboard of pleasurable emotions – in a different context, a rapid transition to shame is however conceivable. Novices in a sport, for example, tend to purchase economical equipment, which fulfills their purpose, at least to begin with, to the delight of the sales clerk. With increasing experience, and in particular through contact with more experienced practitioners of a sport, a shame component develops. This may even go so far that the initially purchased equipment may be avoided entirely, now that it appears inadequate to the situation.

In particular, among adolescents, the conflict between brand articles (brand image) and no-name products may lead to feelings of shame. The image of a brand, however, may also be counterproductive. In certain social milieus, it may be regarded as incongruous to wear Gucci sunglasses – something that has more to do with the brand image than with the design. The color tones of shame are never bright. This emotion is experienced through pastel colors and is pale and restrained.

Particularly when it comes to the intimate sphere, especially regarding sexuality, involuntary disclosure may be experienced as extremely unpleasant. Even today, erotic articles are packaged in opaque containers bearing third-party labels, sparing the (often already ashamed) customer the discomfort of public revelation.

The nip brand is a family-run enterprise whose history stretches back 90 years. As the oldest manufacturer of pacifiers, nip develops and produces a wide selection of products for infants and toddlers. Together with their parents, small children are among the most sensitive target groups, and they make exceptionally high demands with regard to quality and product safety. Their demands are reflected both in strict standards and material requirements, as well as in an advanced sensibility for communication and design impact.

In 2018, when a new subsidiary brand was established, it soon became clear that the greatest challenge was to establish trust between the brand and its users — a delicate area, not least of all because the new, and at this point still unknown brand, was oriented specifically toward nursing mothers. After a comprehensive examination and analysis of emotional factors, among them the anxieties related to the topic of breast-feeding and birthing, an attempt was made to establish clear differences in relation to nip, the umbrella brand, and to do so without abandoning its historically evolved guiding values — which already ensure a high degree of trust among users. The strategic value foundation here was formed by an extension of the existing guiding values via important new dimensions. Ultimately, these flowed as essential ingredients into the brand name and its promise: “first moments: Inspired by mother love.”

Pursued in tandem with brand development was the product design for the first core assortment. Emerging as a major advantage was the close emotional dovetailing between corporate and product design, as well as continuous coordination between decision-making on both sides. To delineate the essential features of this complex process, we have chosen a simplified presentation for the two following pages. Enormously helpful in the context of such processes is a strategic and methodical approach that draws upon the Emotion Grid® and the Design Elements — not only within the design team, but also and particularly when it comes to communication with responsible individuals at nip.

Project scope: the branding process

1. Strategic positioning

2. Communication theme and name

3. Corporate design

4. Packaging design

5. Graphic design (icons, motifs, etc.)

Project scope: product design

1. Modular wide-neck bottle

2. Wide-neck nipple

3. Breastmilk container

4. Pacifier

VALUE ESSENCE

nip (Umbrella Brand)

Family Responsibility

nip first moments

Family Responsibility Guidance

Aspiration Research

STRATEGIC NICHES & DESIGN MISSION

ZONE 3

Current research findings

Expert knowledge from midwives

Research Activity

Design Mission

Lead emotion: INTEREST

ZONE 1

Assume an advisory and accompanying role

Recognize and understand anxieties and needs

Family Responsibility

Security Guidance

Design Mission

Lead Emotion: TRUST + SENSUALITY AREA

Nursing Segment

Gentleness

Naturalness

Security Performance

Hygiene

ZONE 2

Material quality, know-how, and experience

Product logic, simplicity, and operability

Security Quality

Functionality

High standards

Design Mission

Lead Emotion: TRUST + COMPOSURE AREA

The integration of the nip umbrella brand represented a special challenge. Both brands appear side by side, among other things, at points of sale. For this reason, the circle symbol was taken up and adapted through a process of design evolution for the new brand. Now, the circle as a symbol for trust was reinforced by a smooth color transition. This suggests tenderness and openness, symbolically linking rational brand values such as research and standards (gray) with the emotional brand values family, responsibility, and supervision (apricot).

Supplementing the two primary brand colors — warm gray and natural apricot — and creating a new harmony are two additional tones. These are deployed, for example, as a guidance system for the three nipple sizes, and within the icon system for the packaging.

Color: white [Interest | Trust]

Form element on teat: trio [Interest]

Form pathway: S-curve/wave [Trust | Sensuality area]

Mareike Roth | Is an industrial designer who conceptualizes holistic relationships between brands, products, and users. In 2012, together with Oliver Saiz, she founded hoch E — after the team had already performed extensive research along the interface between design and emotion. Previously, she worked as a salaried project manager for various international brands in the area of communication in space. Between 2012 and 2017, she was an instructor for three-dimensional fundamentals and product design at the Hochschule für Gestaltung Schwäbisch Gmünd. She continues to share her knowledge with students at various institutions of higher learning, and to supervise degree theses. In diverse side projects, she links design with personal facets, for example through her label, “A Visible Mind.” Timeouts with her cat Miu — aka Chief Emotion Officer (CEO) — are at least as important. Receptivity to change and creative drive are two of the values that characterize and propel her. With insatiable curiosity, she reflects upon psychological models and the imperceptible factors of influence in our cultural conditioning, preferably during a stroll with sheep or donkeys, or simply in natural surroundings.

Oliver Saiz | To understand people and to bring out their abilities is a labor of love for Oliver Saiz, cofounder of hoch E . Therefore he has been conducting research in the field of design and emotion together with Mareike Roth since 2010. His professional activities encompass specialist publications and teaching, as well as many years of experience in design and consulting for startups and corporations. Fired by a desire for a future worth living for everyone, Oliver deploys his skills as a graphic designer and strategic industrial designer in concert with various enterprises and organizations in order to move forward with ecological transformation. His enthusiasm for genuine change has taken him to climate camps, circuses, and even up trees. To maintain his equilibrium, this nature-loving entrepreneur has been known to combine trips on inflatable dinghies with nights spent in a hammock under the open sky. As a freshly-minted operator of a nesting ball for wrens, he also enjoys relaxing (with maduros and hot cocoa) while observing these tiny avian creatures.

hoch E specializes in the strategic design of the emotional identity of brands and products. The interdisciplinary team from Nuremberg develops solutions in the areas of brand strategy and industrial design for a broad spectrum of international enterprises and startups. For their achievements along the interface between design and emotion, Mareike Roth and Oliver Saiz were singled out in 2014 by the German government as one of the most innovative creative enterprises and awarded the title of “Cultural and Creative Pilots in Germany.” More information about hoch E is available at www.hoch-e.com.