Heritage and Cutting-Edge Technology: Learning from Buildings as Machines

Ana Tostões

Futurist architecture is the architecture of calculation, of rash audacity and of simplicity; the architecture of reinforced concrete, of iron, glass, cardboard, textile fiber and all those surrogates for wood, stone and brick that make it possible to achieve the maximum of elasticity and lightness.1 Antonio Sant’Elia, 1914

The innovative questions raised by high-tech heritage concepts, from identification to preservation, constitute a challenge for the future of architecture, engineering, and the city; and for the need to refresh the definition and concept of architectural heritage, considering the architectural legacy as an immediate present, dealing with past and future, as it must be. In fact, the mention of high-tech heritage may seem like a paradox. If we talk about high technology, it means that we are dealing with cutting-edge construction systems and processes, able to defy the passage of time. Considering an optimist faith in progress, high-tech architecture emphasises the relationship between engineering and modern architecture. Celebrated for its revolutionary design and timeless character, such buildings theoretically do not age. In fact, they demand maintenance strategies, permanent oversight, and updated construction processes in order to introduce new high technological and inventive solutions.

Closely related to the Industrial Revolution regarding the consequences it had for the world of construction and mechanisation, high-tech architecture not only presupposes the use of industrial assembly methods, but also prefabrication itself: a modular construction made from repetitive, standardised elements, capable of creating spaces of great flexibility. The associated image is that of futurism and constructivism, recalling the iconographic imagery of the avant-garde: the visions of Antonio Sant’Elia with the dreamed mega-constructions as parts of the city, integrating sanitation and transport infrastructures, and created in the likeness of a machine. The sense of the provisional, the ephemeral, the demountable, just like the Crystal Palace (1851), the first building with complete iron bones designed to be dismantled and reassembled. The comprehension, more than the admiration for the machine, is the motto, but above all the need to respond effectively and quickly to the demands of the contemporary world and the society of the future.

High-Tech Architecture and the Dreamers of the Immediate

Future

High-tech architecture stands at the base of the modernist architectural revolution as the most innovative achievement within a radical approach to construction.

It is mostly related to the development and the needs of the then-emergent industrial countries, England, for example, symbolically crowned with the ephemeral astonishing Crystal Palace (1851), immediately followed by the developments led by the Deutscher Werkbund from 1907 onwards in Germany.

High-tech, exploring the possibilities of iron and steel, and associated with glass, is based on the denial, or at least as Ludwig Mies van der Rohe referred to it, the unconcern for the classical composition, as defined by the French Beaux-Arts school, specifically by Julien Guadet in his manuals. This indifference towards composition and the classic rules is the cornerstone of high-tech, in other words, a strong belief in mechanical processes within a steel skeleton construction coordinated with glass, proposing an architecture that integrates industrial processes and construction technology into building design.

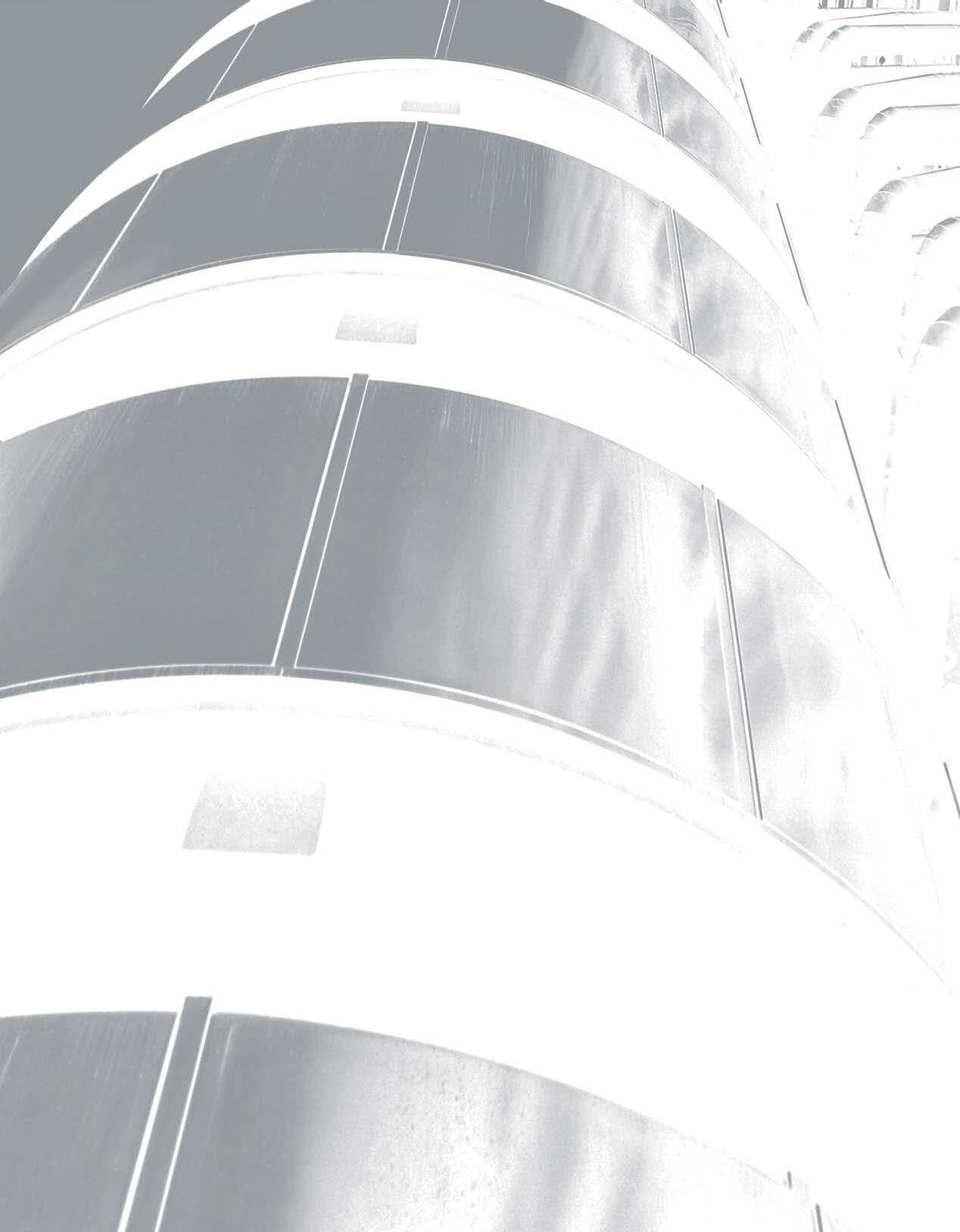

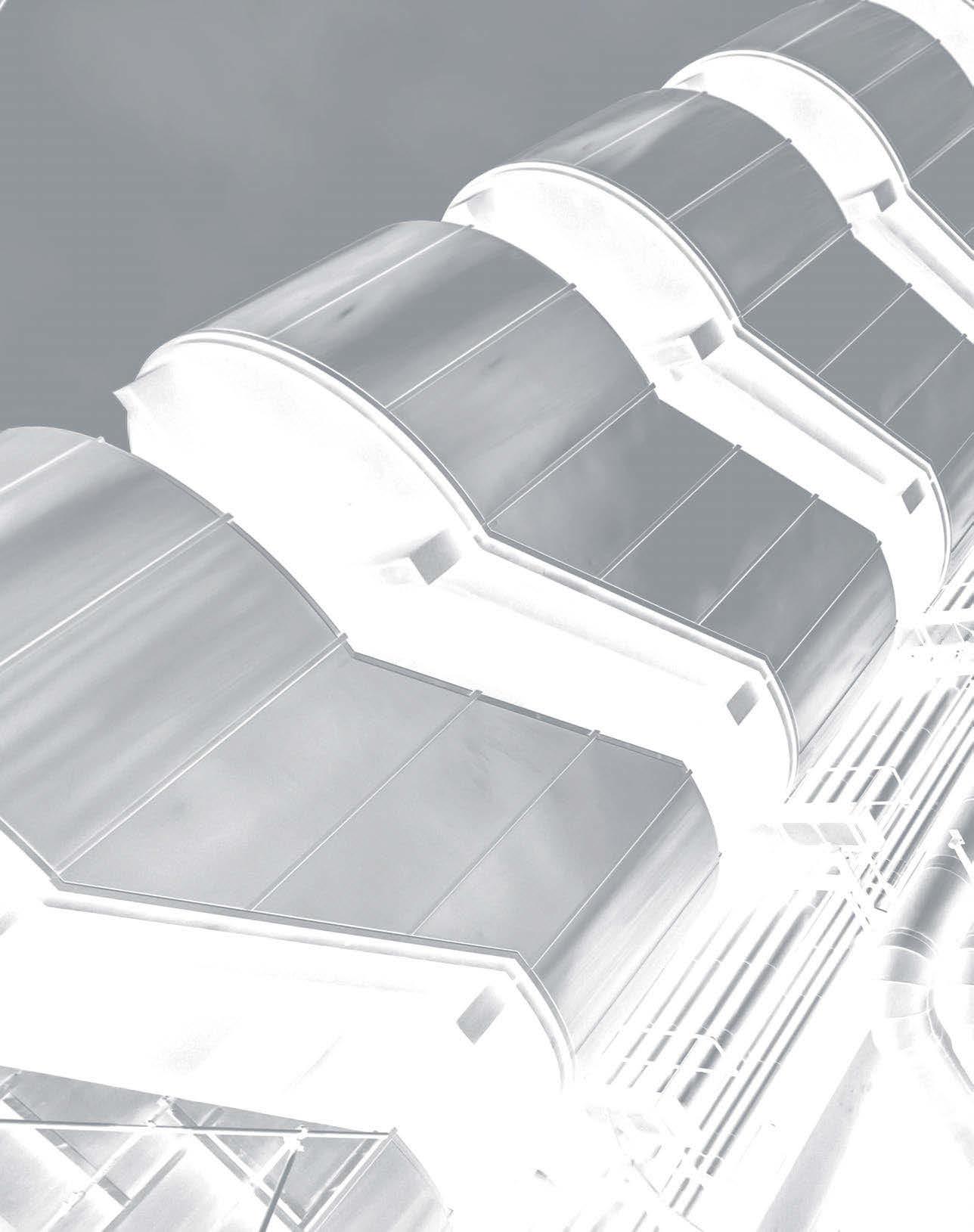

James Stirling’s project for the Library of the Faculty of History at the University of Cambridge (1963–1968) – characterised by the use of large glazed sides of a steel structure coordinated with opaque concrete and brick walls, resulting in a fragmented and transparent building of great scope – stands for one of the first British attempts to renovate the architectural practice by merging the latest technological advances into buildings. But it is the British art historian and critic Reyner Banham who was instrumental in shaping the influence of so-called British high-tech architecture while disseminating the work of Team 4 and historiographically coining the term as a ‘British phenomenon’. Writing mainly for Architectural Review magazine, Banham2 used his rhetoric and critical genius to emphasise the relationship between engineering and the modern avant-garde, becoming a unique chronicler of the movement. Following Nigel Whiteley, Norman Foster and Richard Rogers rose to prominence, Banham praised their Reliance Controls Building (with Su Brumwell and Wendy Cheesman, operating as Team 4), built in Swindon in 1967 and often called the first high-tech building, and Foster’s Sainsbury Centre for Visual Arts in Norwich (1974–1978). He touted the Parisian Centre Pompidou (1971–1977) by Rogers and Renzo Piano when it debuted and became ‘the monument of reference by which High-Tech Architecture is usually defined’. Subsequently, as the preeminent architects associated with high-tech matured to produce works such as Foster’s HSBC Building in Hong Kong (1983–1985) and Rogers’ Lloyd’s of London building (1978–1986), Banham lauded their completed works with renewed enthusiasm.3

It is important to recall Banham’s dissertation, later revised and published in 1960 as Theory and Design in the First Machine Age, arguing that the ‘movement’s claims to functionalism were largely

Fig. 1. Mies van der Rohe, Crown Hall, Chicago, USA, 1950–1956.

Fig. 1. Hospital and Medical Faculty in Aachen, south view.

Fig. 2. The interior: organisation, roof gardens, landscape.

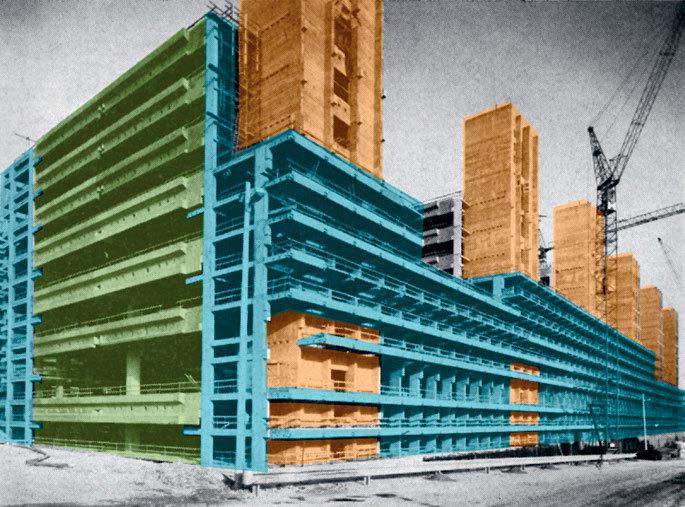

Fig. 3. Elements of the structure: the cores (orange), the core zones (blue), and the field zones (green).

can be identified as a particular organising principle of later projects, for we find it very often in contemporary architecture. Another aspect of Le Corbusier’s concern should be emphasised: In 1963, in a statement on German urban planning, Weber and Brand took a critical look at the development of the post-war period and, in particular, at the urban sprawl caused by the single-family housing estates that were being built en masse. They explicitly refer to Le Corbusier’s ideas of the vertical city and emphasise the preservation of the landscape:

The goal of urban planning [is] not de-urbanization […] but urbanization: concentrated units in a landscape as undestroyed as possible […] in which modern technology will overcome all biological inadequacies and […] communication difficulties. […] Perhaps, for once, a group of our generation should be given the financial opportunity and scientific support to work out new concepts; even if we lack experience […] we might have the courage for an urban utopia.3

Regardless of the urban planning issue, we find here three essential ideas that would also shape the Aachen project:

• The advantages of concentrated units

• Problem solving through technology

• The courage to be utopian and the courage to experiment

The call to entrust the younger generation with greater tasks was soon heeded, and the lack of experience was made up for in the following project, the University Hospital in Münster.

Weber, Brand + Partner and their mentor Schachner won the first prize in the realisation competition in 1963 with a ‘flat-footed layout’, a combination of a projecting low building from which the highrise buildings of the patient rooms develop, also as an urban landmark. Buildings in the United States and Canada, such as the Methodist Hospital in Rochester, which Wolfgang Weber and Peter Brand visited in 1967, served as models.4 The concept of a ‘low building with round bed towers’ was successfully implemented in Münster after extensive studies of all functional interrelationships. It was considered to be the ideal solution for the ‘University Hospital’ concept, which had to combine very different uses in one building.

The Building of the University Hospital in Aachen

In the same year, 1968, when the planning for Münster was completed and the construction was prepared, Weber, Brand + Partner was awarded the contract for the planning of the medical faculty and hospital in Aachen. Ministerialdirigent Dr. Fridolin Hallauer gave Peter Brand the verbal order on a hot July day on Kerpener Strasse in Cologne: ‘You do it – you are young and resilient. Besides, we don’t have time to develop anything new in Aachen, because what’s good in Münster can’t be wrong in Aachen.’5

Hallauer turned out to be wrong, but initially it was also advantageous for the young office to transfer the concept from Münster, since the planning costs here had gotten completely out of hand. Secondary uses are well known in the history of architecture, and a comparison of the designs reveals the close relationship between the approaches. While working on the project, the architects learned of a new hospital being built in Hamilton, Ontario, Canada. In the spring of 1969, members of the office studied the new facility on site and were so fascinated by the concept that they began a fundamental redesign. The Canadian model was not simply copied, but further developed into the Aachen structural system.

The gridded checkerboard layout of the McMaster building is dominated by soaring stair towers and horizontal transoms that serve to distribute equipment. The special features here are the installation floors and the column-free layout of the areas, which means that the floor plans can be used in a completely flexible way, as there are no load-bearing elements to consider, and any type of installation can be placed anywhere. The structure also allowed the free creation of courtyards, which made it possible to illuminate large areas. All these features are not new in themselves, but the analysis of the possibilities offered by this structure was considered the ‘initial spark’ for the Aachen project. The idea was to develop a three-dimensional spatial grid, not on a square grid, but as a band system.

Conspiratorial meetings with numerous participants followed to convince the client of the change, and once this was possible, the complete redesign took place within a few months. By the end of 1970, the first preliminary plans and cost estimates were available. Construction began in the spring of 1971.

The spatial grid had to unite, separate, or interlock five completely different structures:

• The treatment and surgical areas

• The patient areas

• Theoretical medicine, such as laboratories, and so on

• The teaching areas with lecture halls and institutes

• The public areas and facilities

The architects have always insisted that they did not develop a building, but rather a structure, because the building is constructively expandable in all directions and completely flexible in terms of its uses. The diagram associates a city or maybe a machine, but perhaps these references are insufficient limitations. It is a very large and flexible structure. This freedom to change and adapt to any use was not just a promise of young architects or a general wish at the time, but it actually works, is still practiced today, and is not just a matter of moving a few walls! Institutes become patient rooms and seminar rooms become treatment rooms. A few years ago, a completely new open courtyard with a garden was added.6

The planning effort for the realisation was immense, and to avoid delays, it was decided to use

Davide Allegri, architect and PhD, specialised in Architectural and Landscape Heritage, is a Full Researcher and Professor of the Architecture Construction Laboratory at the School of Architecture, Urban Planning and Construction Engineering (A.U.I.C.) at the Politecnico di Milano. Focusing on the topic of sport architecture, in particular on its technological aspects, since 2017 he has been scientific coordinator of the International Master in Sport Design and Management organised by the Politecnico di Milano and Graduate School of Management (GSOM-POLIMI).

Marcela Aragüez is Assistant Professor of Architecture and Director of the Master in Architecture at IE University in Madrid. She received her PhD in Architectural History and Theory at the Bartlett School of Architecture and is a licensed architect. Marcela’s research focuses on the production of adaptable architecture, with an emphasis on cross-cultural post-war practices. Her work has been acknowledged by grants and awards from institutions such as the Japan Foundation, Sasakawa Foundation, Canon Foundation, and the Society of Architectural Historians of Great Britain. She has published in international journals including Roadsides and Architectural Research Quarterly and is a general editor of Architectural Histories

Silvia Battaglia, architect and PhD, graduated with honours in Architecture from the Politecnico di Milano. She focuses her research on the topic of sports architecture and, in particular, on the enhancement of the built heritage within the processes of urban regeneration. She graduated at II Level Master in Progettazione Costruzione Gestione delle Infrastrutture Sportive (now International Master in Sport Design and Management) at Politecnico di Milano, where she carries out research activity and teaching support at the Department of Architecture, Built Environment and Construction Engineering.

Elischa Bischof studied architecture at ETH Zurich. During his studies, he worked as a student assistant at the Chair of Architecture and Construction, led by Annette Spiro, and at the Chair of Construction Heritage and Preservation, headed by Dr. Silke Langenberg. After completing his master’s degree at ETH in 2023, he continued as a research assistant at the Chair of Construction Heritage and Preservation while also working in architectural practice with a focus on existing structures.

Matthias Brenner, M. A. (TUM), is a doctoral candidate at the Chair for Construction Heritage and Preservation at ETH Zurich. As part of the interdisciplinary research project ‘High-Tech for High-Tech’ he is investigating the potential of digital fabrication for repairing the hightech architecture of the 1980s. He studied architecture at TU Munich, Università di Roma ‘La Sapienza’, and Toronto Metropolitan University.

Marianna Charitonidou (Dr. Ing., https://charitonidou. com/) is Senior Researcher, Senior Lecturer, and Principal Investigator in Architecture and Urbanism at Athens School of Fine Arts. She was Lecturer at the Department of Architecture of ETH Zurich between 2019 and 2021. She is the author of more than 100 peer-reviewed scientific publications and four monographs: Architecture, Photography and the Moving Eyes of Architects: The View from the Car (Routledge, 2024), Reinventing Modern Architecture in Greece: From Sentimental Topography to Topographical Sensitivity (Routledge, 2024), Architectural Drawings as Investigating Devices: Architecture’s Changing Scope in the 20th Century (Routledge, 2023), and Drawing and Experiencing Architecture: The Evolving Significance of City’s Inhabitants in the 20th Century (Transcript Publishing, 2022).

Kovács Dániel (1983) is a Hungarian art historian and curator. He studied art history at the ELTE in Budapest and La Sapienza in Rome. Since 2010, he has been a member of the Hungarian Contemporary Architecture Centre. From 2015 to 2018, he served as programme director at the Collegium Hungaricum Berlin and organised two conferences focusing on the post-war architectural heritage of the Eastern Bloc. In 2021 he cocurated the Othernity project at the Hungarian Pavilion of the 17th International Architecture Exhibition in Venice, Italy. Since 2020, he’s been working at the Hungarian Museum of Architecture and Monument Protection Documentation Centres in Budapest, as curator of the post-1945 collection.

Irina Davidovici is the director of the gta Archives at ETH Zurich. Her research straddles housing studies, the history of housing cooperatives, and recent architectures in northern Switzerland and Ticino. The author of Forms of Practice. German-Swiss Architecture 1980–2000 (2012, second expanded edition 2018) and editor of Colquhounery: Alan Colquhoun from Bricolage to Myth (2015), she is currently working on two books, The Autonomy of Theory: Ticino Architecture and Its Critical Reception (gta Publishers, Zurich, 2024) and Common Grounds: A Comparative History of Early Housing Estates in Europe (Triest Publishers, Zurich, 2025).

Catherine De Wolf, Assistant Professor of Circular Engineering for Architecture at ETH Zurich, conducts research on digital innovation towards a circular built environment. She has a dual background in civil engineering and architecture from Belgium, obtained her PhD in building technology at MIT, and worked for the University of Cambridge, EPFL, and TU Delft. She collaborates closely with governmental institutions (e.g., European Commission’s Joint Research Centre) and pioneering industry partners (Arup, Elioth, etc.) on the reuse of building materials in real-world projects, including the reuse of glass from the Centre Pompidou.

Georgios Eftaxiopoulos (BArch(Hons), AADipl, AAPhD) is an architect. He is assistant professor of architecture and urbanism at the University of California, Berkeley, and principal at the architecture and urban design practice EO. Previously, he practiced in Belgium and Switzerland and, most recently, he has taught at the Royal College of Art, the Architectural Association, and the Aarhus School of Architecture.

Tom Emerson is an architect based in London and Zurich. He co-founded 6a architects in London with Stephanie Macdonald, producing buildings and landscapes for the arts and education. He is a professor of architecture and construction at ETH Zurich where he leads a design studio exploring the relationship between making, landscape, and ecology. In his early career, he worked in the office of Michael and Patti Hopkins. He studied architecture at the University of Bath, the Royal College of Art in London, and the University of Cambridge.

Clément Estreicher is currently an architecture student. Upon completion of his bachelor’s degree at EPFL, where he cultivated his interest in history and contributed to the construction of a parametrically processed pavilion, he will embark on his master’s degree at ETHZ. Estreicher served as an assistant to the Chair of Architectural Archaeology and Architectural History, gaining proficiency in photogrammetry. He also undertook the restoration of a centuries-old window as part of a course led by Dr. Silke Langenberg. Following his participation in the construction of a pavilion crafted entirely from salvaged materials, Estreicher completed a one-year internship at baubüro in situ. In addition to his academic pursuits, Estreicher is dedicated to craftsmanship and actively engages in carpentry projects.

Silvie Frei, born in 1998 in Switzerland and currently living in Wettingen, Argovia, started her architecture studies at ETH Zurich in 2017. She aims to dedicate her professional career to the preservation of existing buildings.

Bernhard Furrer, professor emeritus and architect, pursued his studies and obtained his doctorate from ETH Zurich. His professional career encompasses residencies in Finland and Tunisia, along with stints working as an independent architect. From 1979 to 2006, he worked as a preservation officer for the City of Bern, contributing to the listing of its old town on the World Heritage List of UNESCO, followed by its management and conservation. From 1997 to 2008, he held the position of President of the Swiss Federal Commission for Monument Preservation. From 2000 to 2012, he was a Professor of Recovery, Restoration, and Transformation (Recupero, Restauro, Trasformazione) at the Accademia di Architettura in Mendrisio. Today, he continues his work as an independent architect and serves as an expert for the Swiss Confederation and several cantons. He is a member of ICOMOS International and the German National Committee, where he offers his expertise in the field of monument preservation and restoration.

María Álvarez García (MArch, MA, PhD, ARB) is an architect and senior lecturer at Leeds Beckett University (UK), and Lecturer at the University of California, Berkeley (US). Among other institutions, María has taught at the Architectural Association, the Aarhus School of Architecture, and the University of Navarra. Her research has been published in books, international journals, and online platforms.

Patricia Ann Hopkins, Lady Hopkins, OBE, is an English architect and joint winner of the 1994 Royal Gold Medal for Architecture with her husband, Sir Michael Hopkins. Trained at the Architectural Association in London, she co-founded the architectural practice Hopkins Architects with Sir Michael. Recognised with honours such as Honorary Fellowships from the Royal Institute of Architects in Scotland and the American Institute of Architects, she was appointed Officer of the Order of the British Empire (OBE) in the 2024 New Year Honours for her services to architecture, highlighting her enduring impact on the field.

Yat Shun Juliana Kei is a lecturer in Architecture at the University of Liverpool. She is currently investigating how the term ‘built environment’ was first coined in the 1960s in Britain, unpacking the technocratic ambitions behind the reconceptualisation of architecture and town planning. This research will be published as a monograph of the Routledge Research in Architectural History in 2024. Building on this work, Juliana is starting her research on the architecturalurban transformations instigated by the establishment of the Department of Environment in Britain in 1970. Her other research interests include late/post-colonial architecture and urbanism. She just completed her research, with Daniel Cooper, on Vietnamese refugee camps in Hong Kong (1975–2000), sponsored by Lord Wilson Heritage Trust, Hong Kong.

Silke Langenberg is Full Professor of Construction Heritage and Preservation at the Department of Architecture at ETH Zurich. Her professorship is affiliated with both the Institute for Preservation and Construction History (IDB) and the Institute of Technology in Architecture (ITA). Previously, she was a full professor of Construction in Existing Contexts, Conservation, and Building Research at the University of Applied Sciences in Munich. Langenberg studied architecture in Dortmund and Venice. Since her engineering dissertation on ‘Buildings of the Boom Years’, her research has focused on issues related to the development, repair, and longterm preservation of serially, industrially, and digitally produced structures. At ETH Zurich, she and her team address theoretical and practical challenges of inventorying, appreciating, and preserving monuments as well as recent (including very recent) buildings.

Hannes Lukesch is working at the Chair of Construction Heritage and Preservation at ETH. He continues his research on reverse engineering the planar sheet metal facade of the Briefzentrum Mülligen with Matthias Brenner.

Sacha Menz (born 1963 in Vienna, Austria) is a Swiss architect, co-founder of sam architects, former Dean of the Department of Architecture (D-ARCH) and cofounder of the Institute of Technology in Architecture (ITA) at ETH Zurich, where, since 2020, he also directs the Future Cities Lab (FCL) Global programme. Sacha Menz studied architecture with Dolf Schnebli at ETH Zurich, has worked together with him, Tobias Ammann, and Flora Ruchat, and is interested in the entire planning and construction process, in urban planning and the economic aspects of construction, as well as in the organisation of stakeholders and the integration of sustainability goals.

Athena Moustaka (Dr.) RIBA, ARB, FHEA is Senior Lecturer in Architecture and Design. Her interdisciplinary research on concrete sits on the cusp of architecture and philosophy, exploring the agency of concrete in Brutalism.

Thomas Pearson is the founder and co-leader of the Heritage and Conservation Architecture team at Arup. He has delivered design and conservation projects for some of the UK’s most distinctive historic buildings. He authored the book Diamond-tipped, on James Stirling and James Gowan’s Engineering Building in Leicester, after leading a major refurbishment project there. He has taught and lectured at various universities and heritage groups including Docomomo and ASCHB. He sits on advisory committees for the Twentieth Century Society, Georgian Group, Church of England, and Durham Cathedral. Thomas is based in York, in the north of England.

Véronique Patteeuw is maître de conférences (Associate Professor) at the Ecole Nationale Supérieure d’Architecture et du Paysage de Lille and visiting professor at EPFL Lausanne and KULeuven. She is the academic editor of OASE, Journal for Architecture. Patteeuw’s research and teaching explore the relevance of postwar theoretical concepts for today’s architecture in an age of acceleration. She recently co-edited The Architect as Public Intellectual (2023), Authorship (2022), Modernities (2021), and Mediated Messages: Periodicals, Exhibitions and the Shaping of Postmodern Architecture (2018). In 2022, Patteeuw co-curated the 10th International Architecture Biennale of Rotterdam, It’s About Time: The Architecture of Change

Verdiana Peron graduated with honours in Architecture for the Old and the New (master’s degree, 2017) from Università Iuav di Venezia. Her master’s thesis was mentioned at the second SIRA (Italian Society of Architectural Conservation) Young 2018 Award and ARCo Young 2017 Prize. She obtained a postgraduate specialisation in Architectural and Landscape Heritage from the Università Iuav di Venezia (2020). She is a PhD student in Preservation of the Architectural Heritage at Politecnico di Milano and she collaborates on the teaching of their university courses. Her research focuses on the conservation of twentieth-century heritage, in particular on roadside architecture.

Tomáš Ploc is an Architect, PhD student of the Industrial Heritage Programme (2021–present), Architecture and Civil Engineering (2013–2019), and Faculty of Civil Engineering CTU in Prague. His area of research is the history and adaptation of ski jumps.

Uta Pottgiesser is Professor of Heritage and Technology at TU Delft (NL) and Professor of Building Construction and Materials at TH OWL (DE). From 2017 to 2019, she also served as Professor of Interior Architecture at the University of Antwerp (BE). In theory and practice, she is concerned with the protection and conservation, reuse, and rehabilitation of the built heritage. She is chair of DOCOMOMO International with 79 national working parties and editor-in-chief of the DOCOMOMO Journal since 2022, board member of DOCOMOMO Germany, and was chair of the DOCOMOMO International Specialist Committee of Technology (ISC/T) from 2016 to 2021. She is a licensed architect, graduated in Architecture from TU Berlin, and holds a PhD from TU Dresden.

Lenka Popelová is an architect, historian of architecture, and chair of the doctoral programme of the Industrial heritage CTU in Prague (2019). She studied at the Faculty of Architecture CTU in Prague (2003–2011, PhD) and the Faculty of Architecture TU Delft (2001) and taught at the Research Centre for Industrial Heritage (2003–2006) and Faculty of Civil Engineering CTU in Prague (2006–present). Her area of research is the history and theory of twentieth-century architecture and industrial heritage. She has published several books and articles on twentieth-century architecture and industrial heritage. A member of the Czech ICOMOS, since 2023 she has lead the Ministry of Culture of the Czech Republic research project, an active rescue of immovable industrial heritage through new use (NAKI III).

Andreas Putz is Professor of Recent Building Heritage Conservation at the Technical University of Munich. His research on the recording and conservation of recent building heritage is funded by the European Research Council and the DFG, among others. In addition to the history and theory of building conservation and the preservation of historical monuments in the last century, he is currently particularly interested in facade constructions and building components made of acrylic glass, aluminium, flat glass, natural stone, and exposed concrete from the middle of the last century. He is a member of the board of the Arbeitskreis Theorie und Lehre der Denkmalpflege (AKTLD), and member of the German National Committee of ICOMOS.

Christian Raabe studied architecture at TU Berlin and the Université Marseille-Luminy, France. In 1993–1994, he researched at the Institute for the History of Building Technology, TU Cottbus, focusing on Museum Island’s construction history in Berlin. In 1994, he founded Abri+Raabe Architekten in Berlin, working on monuments from the nineteenth century and medieval structures. From 1995 to 1999, he was a research assistant at RWTH Aachen University, and lectured at the International Film School in Cologne from 1998 to 2002. He also gave lectures at FH Potsdam and FHTW Berlin. From 2004 to 2006, Raabe was a substitute professor at Aachen University of Applied Sciences. In 2006, he became a substitute professor of monument conservation at RWTH Aachen University. In 2007, he completed his doctorate at the Bauakademie, and was appointed Professor of Monument Conservation at RWTH Aachen University in 2008.

Inès Rausis was born in 1999 in Geneva, Switzerland. She has been studying architecture at ETH Zurich since 2017 and is currently doing her master’s degree with an interest in social and climate matters in architectural practice.

Xiang Ren (Dr.), architect and academic, teaches and researches architectural history, theory, and design at the University of Sheffield School of Architecture. He directs the architectural humanities research group and the interdisciplinary research unit’s East-West studies in architecture and landscape. Ren’s research, shortlisted twice for the RIBA President’s Research Medal in 2014 and 2016, spans diverse publications such as AA Files, Architectural Research Quarterly, and The Journal of Architecture, covering topics from Dong minority heritage to mnemonics, ritual, and social production. Ren’s recent projects, supported by Arcadia, Alexander von Humboldt Foundation, British Academy, and the French Embassy in the UK, explore 3D scanning of China’s pre-modern architectural heritage, Asian cultural mobilities, the architectural anthropology of homecoming, and minority heritage in place and displacement.

Sara Di Resta is Associate Professor of Architectural Preservation at Università Iuav di Venezia. Architect and PhD in Conservation of Architectural Heritage, her research activities are focused on the conservation of twentieth-century heritage and on the architectural language in conservation design. She is responsible for Education and Internalisation of SSIBAP – the Specialization School on Architectural and Environmental Heritage in Venice. In 2017, she won a Gold Medal at the VI Domus International Prize for Architectural Conservation. She is an executive board member of Docomomo Italia and SIRA – the Italian Society of Architectural Conservation.

Regula Steinmann studied architecture at the ETH Zurich. After graduating with a master’s degree, she worked in planning and execution, and as a design assistant at the ETH Zurich. As a communications manager in an architecture firm, she focused on mediation and public relations. Since 2019, she has been working for the Swiss Heritage Society on publications and campaigns on various topics related to building culture.

Sophie Stockhammer is an architect in Vienna. In her architecture studies at the Vienna University of Technology she focused on the design of the built environment and preservation of historical monuments, as well as communication design in an architectural context and exhibition architecture. With her thesis Die Schule am Kinkplatz. Technische Ruine oder Denkmal? she advocates for the preservation of Helmut Richter’s school, which is currently the subject of much discourse. For several years, she has been supporting architectural firms in projects in the field of architecture, urban planning, preservation, and interior design. Since 2021, she has also been active in exhibition architecture.

Léa-Catherine Szacka is senior lecturer (Associate Professor) in Architectural Studies at the University of Manchester and visiting tutor at the Berlage. She is the author of Exhibiting the Postmodern: The 1980 Venice Architecture Biennale (2016, awarded the 2017 SAHGB Alice Davis Hitchcock Medallion) and Biennials/ Triennials Conversations on the Geography of Itinerant Display (2019), co-author of Le Concert: Pink Floyd à Venise (2017) and Paolo Portoghesi: Architecture between History, Politics and Media (2023), and coeditor of Mediated Messages: Periodicals, Exhibitions and the Shaping of Postmodern Architecture (2018) and Concrete Oslo (2018). In 2022, Szacka co-curated the 10th International Architecture Biennale of Rotterdam, It’s About Time: The Architecture of Change.

Ana Tostões, PhD, is an architect, architecture critic, and historian. Full Professor at Instituto Superior Técnico –University of Lisbon, and leader of the Heritage research line of CiTUA. Guest professor at the University of Tokyo, Universidad de Navarra, and FAUP. Her research field is the critical history and theory of Modern Movement architecture. In this field, she has published Key Papers in Modern Architectural Heritage Conservation (with Liu Kecheng, 2012) and Modern Heritage. Reuse, Renovation, Restoration (Birkhäuser, 2022). She was principal investigator for the research projects Exchanging World Visions and Cure and Care_the rehabilitation, and is principal investigator of the project The Critical Monumentality of Álvaro Siza. She was president of Docomomo International and editor-in-chief of the Docomomo Journal (2010–2021). She is president of the Portuguese section of AICA. She was distinguished by the President of the Republic with the Order of Infante Dom Henrique.

Klára Ullmannová is a PhD candidate at the Faculty of Architecture of the Czech Technical University. In her dissertation, she focuses on the heritage of architecture of the second half of the twentieth century in Czechia. She studied art history at the Charles University in Prague and completed her master’s degree at Uppsala University, where she graduated from the Cultural Heritage and Sustainability programme. Her research interests include conservation of built cultural heritage and perspectives in heritage studies.

Petr Vorlík is an architect and historian of modern architecture. In 2019 he was appointed professor at the Faculty of Architecture CTU, where he leads the Department for Theory and History of Architecture, and is also vice-dean for Science and Research and chair of Docomomo Czech. He is the author of a number of publications, including The Grounds of the CTU in Dejvice in the 1960s, Interwar Garages, The Czech Skyscraper, and Beton Břasy Boletice. As part of a project focused on the architecture of the 1980s (2018–2022), he edited the books (A)typ, Unbuilt, Interviews, Improvisation, and Ambitions. He developed the concepts for several databases, including industrialnitopografie.cz and architektura80.cz.

Peter Walker RIBA is Professor in Construction Science and Management and Head of the Sustainable Built and Natural Environments Directorate. His research interests are in the management of design and architecture and in post-war British architectural practice.

Maria Yioutani-Iacovides (Dr.) RIBA, ARB, IHBC, FHEA is lecturer in Architecture and Conservation Architect. Her research interests span from vernacular to twentieth-century heritage.

Authors