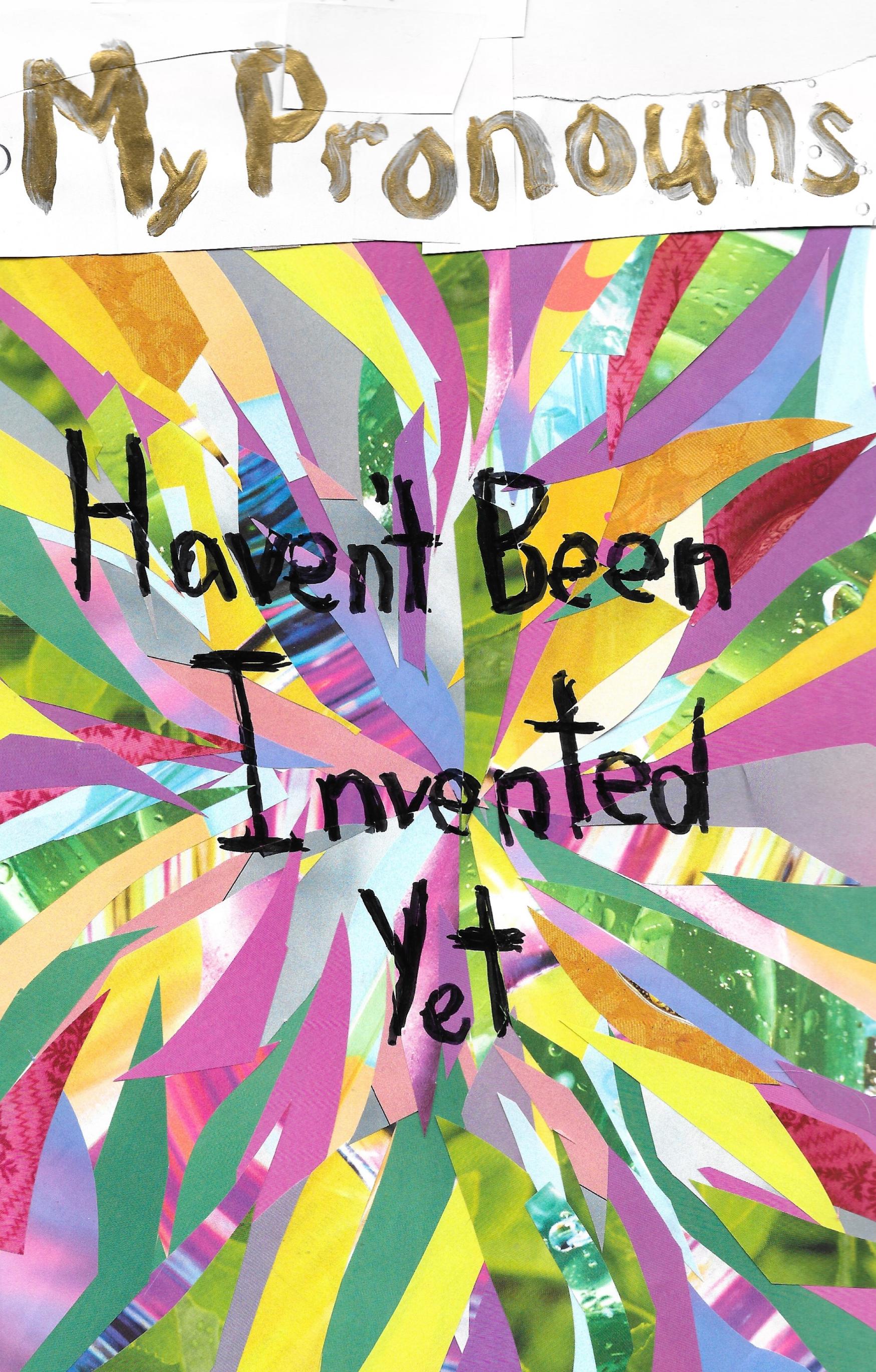

Cover art by Valyntina Grenier. Valyntina is an artist living in Eugene, Oregon, USA. She is the author of three poetry chapbooks and one full length collection. You can find those books at Finishing Line Press, Cathexis Northwest Press and various places where books are sold. You can find her, her visual art and links to individual poems at valyntinagrenier.com

Simon Piesse is an emerging photographer, poet, translator and musician from London, UK. Simon's photography has recently been published by Fusion Art and by Light Space Time.

Jennifer Frederick is an artist, a writer, and a lawyer in Maryland. They have been writing since a young age and creating collages since 2016. On top of being the author of The Coffee Table Book of Pride Flags: Discovering the LGBT+ Community Through Art, their work has appeared in places like Coffee People Zine; Audience Askew; and 1807: An Art and Literary Journal.

Queer moments shimmer within these pages, each fragment a pulse of affection, wonder, courage.

A courthouse becomes a stage where a body is forced to prove itself under the scratch of pens and the weight of official language (Sara Hovda). A married person imagines a different, impossible softness and carries it as a quiet ache (Anna McCracken). Testing the limits of labels results in finding instead the freedom of simply being in-between (Kat Correro). A careful, loving letter home from Toronto folds recollection and longing together, an invitation to meet and belong in two worlds (Toni De Luca). Lavender forts stand as first acts of radical imagination (Wednesdae Reim Ifrach). An alarmed bedroom holds storms that marked a child’s sense of danger — and later, of survival (Zac Thabet). A prayer becomes a kiss, bending into one intimate, stubborn heartbeat (Ejiro Elizabeth Edward). Masculinity is tried on and taken off like costume, language slipping between English and Spanish as desire speaks (Jaime Rodríguez). Binding is not only fabric but ritual — breath compressed, breath returned, a body learned and relearned (Emma Gousset).

A past lover lingers in detail, the aftertaste of passion breaking into thought (András Gerevich). First crushes get misnamed for safety and become the soft, furtive lessons of girlhood (Avani Tibrewal). A fleeting, illicit tryst in an airplane cabin becomes proof that joy can happen in turbulence (Duncan Wu). A myth is readdressed as plea: petals and blood and the question of whether beauty can be preserved (G. Policar). Snow that once stung on playground cheeks returns in other shapes to mark adult collapse and its

costs (Erik Johnson). A living room couch holds the hush of unspoken love and the saddening almostness (Erika Carper). Clay pots filled with marigolds become a slow ritual of mourning, a way to keep a child remembered (Randi Schalet). A secret garden hides scarves and apples and small, stubborn warmth (Ibtisam Shahbaz).

Onstage, someone dons glitter like armor; drag becomes memory and protest braided together (Cade Yoshioka). A woman crowned in serpents and roses refuses being small or hidden (Rowan Aldridge). The past chooses textures: salt, silk, Ocotillo, and a city that lingers on memory like perfume (Walt Trask). Scenes tumble into absurd, fierce vignettes — ancestors, apes, humanity all tangled in one glimpse (Mezi). A petition to fate imagines a body recut and remade with passion rather than restraint (Lucy Coats). A child folds a letter so small it could disappear in a fist, burying a wish among the roots, and those small, shy ceremonies of childhood keep returning to coax wonder into adulthood (Isabel Grey). The self is split and called back, two halves aching to be returned and reconciled (Cara Sullivan). Friendship flickers in suburban dusk an elegy to the fleeting holiness of youth (Rhy Anderson).

Two versions of the same encounter sit side by side, sex work and closeness told in alternate keys, and each perspective reveals a truth the other cannot quite hold (Tony Douglas). Repentance is reimagined as a kind of salvation: a bond reclaimed from condemnation (A.D. Tilley). A delirium of Wagner and wine turns spectacle into confession, music into undoing (Oleg Olizev). Aging becomes appetite: hunger does not always grow quiet with time (David Meischen). A tree bears carved initials and the sorrow of a love that burned too

hot and then burned out (Madeline Avila). A diner of believers becomes a stage for searching — for monsters, for belonging, for proof that what we know to be true can be found (Jessie Scrimager Galloway).

Scent and soap summon a lover’s presence (Svetlana Lukyanova). Ceremony is remade from shadow and crocodile-lore into medicine that steadies and astonishes (Julianna Howatt). Glass towers and city geometry become architecture for yearning, windows full of small, private lights (Io Silas Curtin). The cosmos gets scaled into the palm of a hand, constellations rewritten as intimacies (Elena Bellini). A new set of stars is discovered and named for care that had no sky before (Joshua J. Feyen). On a field under stadium lights a different kind of becoming gambols: metamorphosis disguised as sport, the queer creature that cannot be tackled (Lachlan McGregor). Yearning becomes painted light, a mind thinking of a beloved in color, making absence luminous (Mai Hindawi). A friary fish fry becomes a strange communion of appetite and longing, holiness deep in oil (Danny Warwick). Want churns and burns like breakfast taken black, ravenous and unapologetic, a world seized bite by bite (Zoe Woods). Gentle, untamable intimacy is taught and lived, a careful choreography of love, hands, and shared space that refuses convention (Sarah Gamard).

An attempt at mending comes line by tender line, a reconciliation pieced back into life (Matthew Vargo). The small rituals of home — the kitchen, the laundry, the shared bread become altars of everyday felicity (Izzy Forrest). A refusal of biological determinism reclaims the body from expectation and opens possibility (Kaycee Painter). Intox-

ication loosens the self and reveals what sobriety might hide, whether truth or rupture (Liz Darrell).

Open any page. Let a sentence hold you, an image snag your mind, a voice become the company you need. This anthology is far from tidy; it is messy. Alive. It holds work that will make you laugh in the wrong place, sob without warning, and nod because a small truth has finally been named. Read a courtroom plea then a kitchen hymn; follow a prayer into a kiss; sit with a mourner planting marigolds and then walk into a stadium where a beast comes out of the locker room to cheer. The pieces are faithful to life’s contradictions — erotic and holy, comic and devastating — and they were chosen to sit next to each other so those contradictions can sing and shout. Enjoy Beyond Queer Words, 9th Edition!

Gal Slonim, Editor

Sara Hovda

Sara Hovda is a transgender woman from rural Minnesota. She currently attends the MFA program at UC-Riverside while also working as an online entertainer. Her poems have appeared or are forthcoming in magazines such as Passages North, Nimrod, and Shō Poetry Journal, among others. She can be found online at SaraHovda.com

I wrote history, court documents. My black dress impressed the judge when I begged him to change my name. A wish transmuted into longing, how the throat vibrates into song. I excised the betrayal: my dick, angle of jaw. One surgeon carved my pussy, living mausoleum. Another shaved my brow. Before all this, I stood in suicide’s mouth, waiting— when it swallowed, I made my decision— let it take the boy.

Anna McCracken

Anna McCracken is a writer, systems dreamer & bridge walker living in the Kimberley. Anna marinates on the relationships between ecology, mythology, queerness, sickness & settler colonial experiences that live both inside and outside her flesh.

What if we had swapped sides— changed a decade of sameness? What if the latex didn’t predict the shape of us?

I never knew, on your side, you could see Sirius. I wonder, if every night, with my head turned upward to that burning, bright beacon, I might have held you and her differently.

If I had dared to ask for more, to insist: this isn’t a phase but a birth mark.

I can’t return from her body of softness now trapped on the right side, gazing at a ghost gum, chanting the wrong mantra into my marital bed.

Kat Correro

Kat Correro (they/she) is a queer, nonbinary poet, artist, and mental health advocate based in the South. Through poetry, performance, and visual art, they explore themes of identity, healing, and radical self-expression. You can find more of their work at kataclysmickreations.com

I’ ve worn the name they gave me like a borrowed dress too tight, too frilly, never mine.

So I cut it short. Just Kat. No title. No bow. Just breath and bone.

I pass as girl the curve of my hips, the sound of my laugh, a name in someone else’ s mouth.

But inside, I’ m a childhood daydream, racing the boys, playing prince and princess, boyfriend and girlfriend, the cat, the dad, the storm. Becoming Sporty Spice and Michael Jackson in the same afternoon.

I was most myself before puberty carved me up. Before curves told a story my heart never meant to write.

I wore sports bras like armor, shrinking into corners where no one could call me “woman” without the word shattering something inside me.

You call me she— I flinch.

You call me they— I breathe.

Not because it’ s perfect, but because it’ s free.

I am not man. I am not woman.

I am the child in the photograph grinning with scraped knees, soft and fierce, both and neither.

I don’t fit in your boxes. I never wanted to. I’ m not made for straight lines.

Call me what lifts my spirit. See me in between, around, beyond.

Just human. Just me.

Toni De Luca

Toni De Luca is a queer writer, poet and psychotherapist based in Scotland. She writes about the human experience, inner journeys and our connection with nature. Her work has been published in Scots and English. @toni_she_writes

Toronto, August 1st, 2025

Dear Mamma,

The other morning on the streetcar to work, I saw a schoolgirl pull a handwritten letter from an envelope. Who sends letters anymore? But I watched her face glowing in the early sunlight as she read, and I thought of us. I was fourteen, sitting cross-legged on your bedroom floor, the tiny mirrors on your turquoise saree catching the light. We were sifting through the stacks of family letters in the teak chest under your bed. You were helping me with my school project on the Indian Diaspora. You read aloud in your careful English reading voice while I teased you, though really I was entranced. New York. Melbourne. London. Relatives I’d never meet, writing news of studies and jobs. I wanted more than their reports. I wanted to know about their lives: the food, the weather, whether monsoon storms reached that far. That day I thought: maybe one day I’ll go abroad too.

You told me that people left India but never in spirit, and their letters proved it. I wonder now how much truth they put into those envelopes. What they shared, what they left unsaid. It’s the same for me here in Toronto. You’ve asked me for years to send you a letter for the family chest. So here it is at last.

Life here is good, Mamma. I have a job where I’m respected and not overworked. For the first time, I have time for life itself. And maybe that’s what I need to share—the unedited part of my life we never speak about.

I still remember coming home from school, running into your arms, then sitting at your dressing table with your shiny gold boxes of makeup. While Papa was away, you let me play, blending colors, finishing with kajal and mascara. You’d kiss my head, then remind me to wipe it all off before dinner. I don’t

know how, but I understood from your eyes, from your tone, that Papa must never know about the game I play with your makeup.

I’ve always wanted to ask: did you know? Even then, did you know? Is this why you’ve kept the aunties at bay, never pressed me to marry?

Mamma, I need to tell you what I haven’t said. I am not alone here. I have someone. His name is David. He’s kind and funny. He makes me ginger tea when I’m sick, and he’s even learned to cook khichdi. He knows me, really knows me, and still chooses me. He is… my home.

I think you’d like him. I imagine the two of you sharing tea and pakora on a rainy afternoon, just as we used to on the balcony in Bangalore. I imagine you telling him stories from my childhood, and him laughing, nodding, adding his own about my habits now. You may not gain a daughter-in-law, but you would gain a son-in-law.

I want to get married, Mamma. It won’t be the marriage others expect, but it will be full of love. And I want you to be there. This may not be the life you imagined for your son, but I’m still the same person you’ve always loved. It is only by leaving India that I’ve been able to be my true self, but now I want you to know me as I am.

Please keep this letter in the wooden chest with the others, Mamma. But also see it as an invitation. David and I are waiting for you.

Your loving son, Krishan

Wednesdae Reim Ifrach is a queer therapist, researcher, and artist whose work weaves together poetry, visual art, and expressive therapies to explore identity, healing, and transformation. Their creative practice centers on giving voice to marginalized experiences, using art as both a therapeutic tool and a form of resistance. Through a harmreduction and trauma-informed lens, they create spaces where grief, joy, and queer embodiment can coexist in vivid, meaningful expression. IG: Queer.Art_Therapist

You say: boxes define.

Contain. Classify.

But I was a box once, a fridge box, a lavender fort on the beach. A world unto itself. Imagination, not enclosure. Magic, not shame.

I didn’t create these other boxes, the ones with checkmarks and limits. You did.

I click them now like keys on a piano, because I must. But don’t you mistake compliance for consent.

I am not wrong. You are not right. We are, in the simplest of truths, different. Valid. Alive.

I ask you, not loudly, but with the deep voice of the sea,

the one that carved every coastline: Let me be.

Witness me as I witness you.

Because we are the joyous children inside the lavender box before shame had language. We were never broken.

We have always existed. And we are still playing in the technicolor.

Zac Thabet

Zac Thabet is a West Virginia-based writer whose work has been featured in Et Cetera Literary Magazine, Blue World Literary Journal, Mountain State Press, and The New York Times. They also served as Nonfiction Editor for Et Cetera Literary Magazine in its 2023-24 issue. Zac received their B.A. in Creative Writing and Literary Studies from Marshall University in 2023 and is currently pursuing an M.A. in English from the same university.

I was born in the year 2000. This meant that growing up, much of my childhood was spent somewhere between the birth of boy bands and the death of landlines. It was a time when most of us relied on cable, and to own a flat screen was a luxury. It meant my siblings and I arguing over whose show was going to be recorded because they all came “on the air” at the same time. It meant all of us crowding around the television at 8 o’clock because that’s when our favorite reality show came on. It meant that anytime there was a storm warning, an alarm would interrupt whatever we were watching to inform us of the impending storm It meant plugging my ears and crying at every alarm, only to be held by my mother until the storm felt conquerable.

As a child, I was usually afraid more than anything else. Most people I know have used fear to dictate their life at one time or another, but I took it to an extreme. I could create a fear-induced catastrophe out of a light breeze outside. Who is to say why that is, really?

Still, that couldn’t really serve as an excuse. After all, I was also the child who had panic attacks at 6 am over how certain shirts felt on my wrists. If my hair reached a certain length, I couldn’t fall asleep at night. So, no, my social fears did not quite explain my anxieties. Of all my anxieties, the one that recurred most often was the fear that some natural disaster would strike and tear my home apart. I was constantly peering over my shoulder, waiting for a tornado to burst from some nearby bushes, or a tsunami to rise over the hill behind my house. Our childhood home sat nestled in the mountains of West Virginia, making the likelihood of a tornado or a tsunami extremely small. Even

knowing it was unlikely, I couldn’t convince myself it wouldn’t happen.

I grew up when movies like 2012 and The Day After Tomorrow were on every other channel, and I was gifted—or cursed—with an imagination that could not only build a castle but also conjure all the monsters hiding inside it. This is the same imagination that once caused me to cry so profusely it woke my parents up down the hallway. Why was I crying? Because I imagined a bloodthirsty wolf had broken in, waiting to tear me apart. It really is no wonder I expected the worst.

Every time I heard that alarm on the television, I had to stop and run into my room. I’d find my favorite bag, a clear plastic one with “Crayola” on the front and bright orange straps. I collected all the things I loved most: all the books I could carry, my favorite toys, a picture frame of me and my mom, and my old Taylor Swift disc. I’d run back into the living room and set all of my things up until they surrounded me. In my mind, these were the essentials. If a storm came and blew the house down, I had everything I needed right in front of me. In a way, I guess I was grabbing the things that made me feel safe. The things that made me feel like I would survive the tornado. Surrounded by my treasures, I could almost believe I would survive anything.

If storms once dominated my imagination, the real storms were waiting in the hallways and on the streets—monsters I could not conjure away.

It is funny to think back on the things that left us terrified as children. The irrationality of a tornado hitting West Virginia is the same irrationality that makes every child’s monsters seem real. Reflecting, I want to go back in time and tell the seven-year-

old queer kid that their battle has only just begun. There were far worse monsters than a storm or a television alarm. In fifth grade, two boys would call them a ‘wannabe girl’ simply for bringing a diary to school. Later, a stranger at the store would tell them something was wrong, just because all they wanted was a Taylor Swift doll. This encounter would traumatize them to the point that they pretended to dislike Taylor Swift for years. And in sixth grade, a boy would threaten to stab their eye out and follow them after school. As a queer person, they would be compared to a murderer by my own family members and threatened by a passing stranger at 16. Their battle has only just begun.

Of course, I’m sure that seven year old wouldn’t have listened to me. Besides, who is to blame them? Even now, I still have panic attacks over my clothes, and that storm alarm can still make me cry—but I survive. I always survive.

Ejiro Elizabeth Edward is a writer and passionate advocate for the arts. She is the convener of the Benin Arts and Book Festival and is currently pursuing an M.A. in Creative Writing at Iowa State University, where she holds a scholarship and is a recipient of the Pearl Hogrefe Award.

Note. Chi, in the Igbo world, means God—an ultimate supreme overseeing one's destiny.

Chi, as in sister, or approximately God, depending on which face you show— playing God or mammon, Chi,

Do you remember the yellow sand of Eko? Filling up our hands with them as we laid the foundation to the fire, that same fire where I once saw horses dancing. We would lay our backs, bodies facing the heavens. You spoke of an alternate universe where angels danced. I only thought of your pink cheeks rubbing the blackness off my body and I would call your name

As in Chi. Chinelo. Chinyere.

As in Chi. Strength, Given.

As in Chi. Chi! Chi!

As in god! god! god!

As in

My first kiss melting into your mouth as lovers, but time fast-forwards into a place

where I cannot pause time, so I step into this paper, into this ink, and stay in the loophole called here.

Jaime Rodríguez

Doing to ourselves is the undoing of ourselves.

Jaime Rodríguez is a Chicano poet from the Rio Grande Valley. His work explores queer intimacy, masculinity, and cultural silence. Blending English and Spanish, his poems follow the coded languages of desire, survival, and sacred disruption.

Am I an ordinary eighteen-year-old when I jerk off to women, men, money, and week-old fruit? when I lick sweat from my pits, and cum into boots—rank, wet, beat— too dirty to clean, too mine to lose?

Am I an ordinary eighteen-year-old when I finger the tender rim, spit-slick and testing my limits? when I ride the ache, one knuckle deeper, eyes shut, his name slipping— half-swallowed, conflicted, ceiling fan ticking?

Am I an ordinary eighteen-year-old when I fuck toilet paper rolls, praying I’m too thick to go through it? when I taste my own cum, then spit—gagged by truth, sink, slick—won’t rinse, refuses to leave me, shadows under the door—waiting, not knowing?

Am I an ordinary eighteen-year-old when I huff his jock yellow and stiff ripe and stretched, once damp from gym? when I stroke with a sock till it stiffens, bleach kick stinging, salt-thick and dense, boards creak, light through slats betraying me?

Am I an ordinary eighteen-year-old when I sink into the backseat, abs sticky, jeans bunched at my knees? when I replay what I did a storm I drown in, jersey damp, windows fogged from breath, no one opens the door, and I don’t flinch Am I ordinary now?

Ten years later, I move through life when I nod through their jokes, loud and crude, raunchy, brash fake laughs, frat slaps, secret grips. when I say “bro,” like it’s a shield, masculine, forced, automatic from my throat— a prized chameleon still laughing, still lying still only me.

Ten years later, I move through life— when I watch him crouch hips open, bulge pressed unaware, inviting. sacred rites—slapped asses, warm hands, nurturing lies. when I remember the pin his thigh across my face. cold shower, body steam rising blinders on, no one speaking. and drive home to shower again—sore, stiff, and silent.

Ten years later, I move through life when I finally let go—no words, just moans and blur, breath, skin, and names: Swallowed, Red Panties, 9” Thick. when I whisper their plates under my breath, like a spell. the small space scented, stained tissues on the floorboard. they say nothing—chats boxed, locked, three combinations.

Ten years later, I move through life when he stretches, bare and yawning, towel forgotten. he sinks into the bed, legs open scratching, loose, unguarded. when he turns, pulling the blanket low half-asleep, unknowing. tracing his moles—pillow between his thighs—envied, soft, invited. then curls soft gentle snore, passing gas raw, natural, potent.

Ten years later, I move through life— when he texts “you up?”—snaps, memes, but never how I’ve been. waiting: pings fade texts die unanswered lips and nails bitten raw, gutpunched, spent. when I ask what he wants, he shrugs “whatever” deflected, burdened, dismissed. cold beer sweating like me. mirror shame fractures; lies split. door half-open, borrowed boxers drop—subtle. familiar. Unclaimed.

Emma Gousset

Emma Gousset is a queer writer and farmer from Mississippi. They currently live in Seattle, Washington, where they draw inspiration from the natural world and daily joys and toils of working outdoors. Their work can be found in Rooted magazine, TheDilettanti, and AmbrosiaZine.

Inhale, weave broad shoulders through the fabric, pressing lungs into a kiss.

Breath lodged in bronchioles leaks in shallow exhales. Sit up straight so it can drain.

In the mirror, your chest lies flat as the Delta fertile, masked, motherhood.

Empty highway bought by breath. Run your fingers along the cover crop and try to tread lightly.

Soil can only take so much compaction before it cracks, crumbles into dust. Peel it off soft, slow

let your ribcage return so the scream inside can loosen.

Exhale, slouch into submission,

chest tighter than before.

Ex

András Gerevich

András Gerevich is an all-round Hungarian writer with eight books of poems to his name. His work has been translated into over a dozen languages. He is a graduate of Dartmouth College and the National Film and TV School in the UK.

I saw him in a restaurant yesterday but he didn’t recognise me, his shaved head turning away to think.

When we lived together, ten years ago, we always made eyes, made love, spent whole days in bed.

I’m glad he didn’t recognise me. I didn’t want to puzzle out the years men, women, drugs, medication from his confused stare.

Once precious, now his face hangs, worn out like last season’s shirt so many men wanted to be with him, and what pride in having him.

As he sits, the glint of his dark arm still has the motion of the old embrace, which I don’t miss because I feel it on my skin sometimes, when I think of him. He was the best of all my days.

translated from the Hungarian by Andrew Fentham with the author

Avani Tibrewal

Avani Tibrewal is a high school student who writes to make sense of the world. Outside of writing, she's usually reading, studying languages, or overthinking plot twists.

I said I liked him because your face lit up like the birthday candles I was too shy to blow out. You grinned, told me finally, as if I’d just joined a secret club I didn’t ask to be in.

You braided my hair that day, tighter than usual. Said he's cute, and I said yeah, though the word didn’t feel like mine.

I watched you write his name in the corner of your notebook with little hearts. You drew one for me, too, next to his, and I smiled like a prize I didn’t want.

When I sat next to him in class, I kept thinking about your hands how they moved when you talked, how they smelled like pencil shavings and lotion. He passed me a note. You winked from across the room. I folded the paper into a square and never opened it.

Once, you fell asleep on my shoulder after a movie, your breath slow and warm.

I didn’t move, didn’t speak, just stared at the ceiling like it could explain anything.

Years later, someone asked about my first crush. I said his name out of habit, like reciting a poem I’d never understood. But really, it was you. It was always you. I just didn’t know who the story was meant for.

Duncan Wu

Duncan Wu is Raymond A. Wagner Professor of Poetry at Georgetown University. He is the author of Origin Myths, a book of poetry published in 2024. He is bisexual and has had a number of same-sex relationships.

(BA217, Washington DC to London)

To Nicholas

Because you wanted to shag in the plane we climbed over our neighbors at dead of night, found an empty toilet, locked it tight, and, flying high, I could hardly contain myself. You dropped your Calvins. “Cockalicious,” you said, “slam on the jiz fountain, Henry!” and I, inflamed, went lust-monkey blindly unashamed, screamed, torpedoed your ass (surreptitious), came fast on the mirror, door handle, basin and taps. Like Adam and Eve we slunk from our soiled nature then sunk back to sleep. If such acts made me a vandal or owner of a childish mentality I think them now of the utmost sanity.

G. Policar

G. Policar (He/They) is a writer originally from San Francisco, based in San Diego. When they aren't writing, G. can be found singing, playing trivia, or searching for the best turmeric latte.

You never even asked what kind of flower I wanted to be.

You say there was no time, but what can the gods do if not the impossible?

Your father impregnated a woman, as a goose.

When Zephyr blew the discus why did you let me jump in the way? You, the god of song. Surely, you heard the sharp sting a flat of the flying guillotine. Was I so beautiful that I had to be a bloom?

You should have made me a star. If you loved me so, I could’ve hung in the sky, as you rode across.

Erik Johnson

Erik Johnson is an emerging writer living with his husband in New York City, taking writing courses, and trying his hand at flash fiction, short stories, poetry, and a draft novel. He has been published in The Yard: Crime Blog, Half And One, and Humans of the World. He also has work in the Permanent Collection of Chateau D’Orquevaux

International Artists and Writers. His writing crosses genres, often containing elements of grief, social justice, LGBTQ+ themes, and situations where light and dark meet in the human experience.

White sphere, hastily sculpted, Crystalline hatred.

“Run, faggot,” was your warning. A three-count of escalating terror.

I try to outrun the pummeling, Tingled by fear, Adrenaline limbs.

But parkas can be death shrouds, And snow boots can become anchors. Your laughter, an icicle driven into my spine.

A billion white diamonds: They say each is different, unique. Yet each inflicts pain just the same. Diamonds sparkle the sky; Diamonds blanket the grass; Diamonds erupt from my eyes; They are washed out,

An ocean contained in a teardrop.

Pristine crystals embedded in my collar. Shards of shame slither down my back.

Icy trails of scalding humiliation:

Pure white douses my desires, virginal skin aflame.

“How did you get so wet?” my mother asks. My lie, a tiny suicide of the soul.

How do I tell her I am weak, devoid of courage?

I got caught in the blizzard of your malevolence; It entombed me in disgrace.

To me, you will always be a monster with deadly aim.

White line, razor cut, Crystalline affliction.

“Help me,” was your plea. A whiff of deepening desperation. You cannot outrun the high, Ablaze with frenzy, Euphoric limbs. But candy can be toxic, And snow powder can be addictive. Your mania, a squall beneath your skin.

A billion white diamonds: They say you can dilute them. Yet they can poison just the same. Diamonds sprinkle the counter; Diamonds coat the steel; Diamonds slicing into your cerebrum; They are washed out, A spray of crimson droplets.

Tainted crystals embedded in your ganglia. Tiny daggers tearing through the vasculature. Bursting needles of prickly stimulants: Ruby splotches splatter the snowscape; misfiring filaments from iced circuitry.

“Will no one help him?” your wife asks. Your oblivion, a lesion on her heart. Who will tell her you were mean, devoid of decency? You caught yourself in an avalanche of dependence; It interred you in despondence. To her, you will always be an angel with shackled wings.

Your cruel battering plowed away sympathy. Your tragic addiction conjured an air of justice. Your wife may mourn your memory; Your victim delights in your death.

Yet, are either of us free when your frozen specter still haunts?

Erika Carper (she/her) writes in Baltimore, Maryland. She received her Bachelor degree in English at Otterbein University, and is now pursuing her Master’s in Opera at Peabody Conservatory. Feel free to connect with her on IG: personal: @artsy.metrics; professional: @operawitherika

I had sat on this particularly ugly brown, beer stained couch a million times. Well, actually I had sat on the one across from this couch a million times, which was just as brown and beer stained. This was because most of the time, Angie and I sat on separate ends of the room. Though sometimes, on the nights she pretended I was her girlfriend, we snuggled against the worn, scratchy fabric till I drifted to sleep on top of her long, slender form. I could feel her arms protectively around me, my head resting against the bony part of her collarbone. This would leave a mark on my cheek the next day, and I would smile knowing that I could keep a piece of her for another two or three hours tops. But on this particular evening, the only piece of Angie lingering on me was the faint smell of the coffee she had accidentally spilled on me earlier that morning, which was admittedly better than nothing.

I was cast in the role of best friend that day, which happened to be the one I hated most. (This was because best friends don’t have sex, but mortal enemies are always ensured time between the sheets.) We had been out all day with her other friends, many of whom were passed out on the upstairs couches, leaving Angie upstairs in her room, and me on the couch with James, my boyfriend at the time. I was leaning my body against his chest, keeping my eyes fixed to the movie playing on the TV. The stubble on his chin scratched my cheek like a battalion of Brillo Pad soldiers, and every one of my muscles seemed tangled up in vines of super glue tight and defiant. The longer I attempted to sit still, the harder I continued squirming into new positions. With each shift, his grasp on me seemed to tighten, pushing me deeper into his embrace. It was obvious to me what was coming next.

Please don’t try to kiss me.

But eventually he asked, and what was I supposed to say?

Not now, James. I’m gonna go make out with Angie as soon as you fall asleep.

So I smiled and nodded, letting him press his lips against mine. His tongue entered my mouth like a fat ice cube cold and shocking. It made violent swirling motions against my teeth and wormed its way along the insides of my cheek.

I have that essay due on Jane Eyre next week. I hope my teacher likes it.

Axe body spray aggressively leaped off his neck and into my nostrils. My stomach started to churn, and I closed my eyes tighter to avoid the dizziness.

Jane Eyre was a great book.

His hands slowly traced the arch of my back, making their way to dangerous territory.

Remember when she heard Rochester calling to her in the wind?

His giant, furry hands had finally slid into their desired destination.

Fuck Jane Eyre, James’ hand is on my ass.

I thrusted my body upward to subtly push the hand off, but he mistook it for an act of passion, and his hand clutched tighter. I turned over on my side, but his hand chased after me, latching firmly against my bottom. The claustrophobia in my chest tightened, nausea rising, my skin crawling.

Just when I thought I couldn’t take another second of it, the smell of the brown couch rose around me the same couch where Angie and I had spent a hundred nights. Everything smelled like her: her citrus vanilla perfume, the soapy laundry detergent that

stuck to her clothes, her Secret Watermelon deodorant all mixing together and easing the weight of my stifling nausea. Her presence filled the room in my mind, every movement and curve replaying itself on the couch where we had spent countless nights together. I imagined her trotting in from a long run, sweat glistening on her skin, the faint scent of her perfume lingering in the air. I began feeling round, pink lips pressed delicately on my skin. The gentleness of her mouth on mine was a hushed secret she told me slowly. The animal paws clenched around me softened to long arms sitting on my body like silk sheets on a freshly made bed. I reached up and grabbed the thin brunette locks that hung lazily around her head. They smelled of Herbal Essence and my musky perfume. She must have gotten that a lot.

Ang, you smell just like Eva. Probably because you’re secretly lovers.

I pressed my body harder up against James. I began to crash my lips forcefully onto his mouth. My sudden change of interest shocked him, and he seemed almost confused by my gesture. He started moving his tongue faster in my mouth, and my head began reeling at the sheer possibilities it incited. I felt something against my thigh, hard and distinct. My eyes were closed so tightly that purple spots splattered across my pitch-black view. My head could hammer nails into the wall; my body could light the candle in the corner. Dizziness was overcoming me, and I was forced to pull away. As surprised as he should’ve been, he wasn’t. It was usually at this point I stopped anything more from happening. He simply sat up in his routine defeat, and I cast my eyes immediately to the ground. I knew he was waiting on my made-up excuse. I didn’t dare give him as much as a glance.

“Hey, I’m just tired.”

He nodded, giving me a reassuring smile. “Don’t worry about it. We’ve had a long day.”

I hated how nice he always was. I wished he would scream at me, break up with me, or tell me I was a terrible person. But he never did. He always smiled, told me it wasn’t a big deal, and pretended our relationship was normal. I had even convinced him I was taking things slow for his sake. I was awful.

Nevertheless, I dragged myself in all my awfulness home to Angie’s bedroom. I closed her door a little harshly, to wake her in case she was sleeping. She turned around from her side of the bed and looked me up and down.

“Hey,” she said.

I crawled into my spot beside her. “Hey,” I responded quietly. We were quiet for a long time, just looking at each other as we often did.

“James and I were making out down there,” I told her, as if it meant anything.

“Gross,” she mumbled, turning away from me. “I knew that’s what you were doing.”

Her tone was brash and reeked of bitterness. I bit my lip, knowing I shouldn’t ask what I was about to ask next. “Are you jealous?”

She started laughing, of all things. “No,” she said immediately.

I frowned and turned away from her. I almost felt as if tears may find their way into my eyes.

“Will you hold me?” I asked quietly.

“Yeah,” she said, like I just asked her to take the trash out, like it wasn’t anything.

She wrapped her arms around me, and I buried my head into her chest. She smelled the same, felt the same, and it was enough to hold me steady. Everything ended here in this room, in this bed, and in her arms. We were safe and warm. We were happy and sick.

Even worse, my thoughts weren’t on my boyfriend downstairs, but on my pretend girlfriend here. The tiny part of my brain that discerned actual facts knew Angie had no real intentions of ever being with me. She had rejected any invitation of an actual relationship, saying, “Why would we sacrifice what we have now?”

To which I responded, in my head, Because what we have is nothing. What we have only exists in the confines of your dark bedroom with stupid purple walls. What we have is quiet passion when you’re lonely and blaring silence after you get your fix. What we have is eating me alive and spitting me out again. Whatever we have, is far from what I want. But out loud, I said nothing. Because nevertheless, losing whatever we had meant losing Angie, too.

So there I was, wrapped in the comfort of her embrace, convincing myself we were something we could never be.

“I love you,” I told her.

“I love you too,” she whispered back, kissing the crown of my head.

But I knew it wasn’t the I love you I was looking for.

I knew that right now we would go to bed just like this, lovers lying in the dark. But in the light of day, we would wake up as nothing more than casual friends. I would go back to my boyfriend, and she would go back to her comfortable indifference.

But for tonight, I would keep lying until it didn’t hurt as bad.

Marigolds Randi Schalet

Randi Schalet is a clinical psychologist and writer living in Berkeley, California. She began writing poetry following the overdose death of her twenty-six-year-old queer son, a loss that reshaped both her life and creative voice. Randi is the author of two novels, Lunch and Dessert, and her memoir pieces have appeared in publications such as Chicago Story South, Peauxdunque Review, and Prime Time Magazine. Her poetry chapbook The Last Things I’ll Remember will be forthcoming in 2026 from Finishing Line Press.

Marigolds in clay pots

Line the dock, Those cheap, showy fillers.

Crooked mohawk

Dyed in the mirror, Purple-stained fingers.

Spandex tights

Hugging his butt, The swish:

All he thought he had to offer.

Everyone says He must be somewhere

A spirit, a spark, his soul

Reborn as a Trumpeter swan

And released into Jamaica Pond By the mayor.

“You’ll be happy when I’m gone,”

He argued, headphones on. I wish he could see me now So I could prove him wrong.

Ibtisam Shahbaz

Ibtisam Shahbaz is an Australian writer whose work has been featured in several anthologies, reflecting her commitment to contemporary poetry. Ibtisam served as the Poetry Editor for Belonging Magazine, where she curated diverse voices in art, short story and poetry. Through her writing, Ibtisam seeks to create space for shared humanity.

there in a secret garden i lie where water turns to might and sun wanes into night. i think i will come back here tomorrow, the day after, and the day after that.

her hand opens to the sky, our smile lines crease deeper than a fold in a palm, a deer hobbles over a folded picnic blanket and nuzzles a half-eaten apple i was happy here roses blooming over lush grass the dew dampens my jeans the bees might sting me, dear so she plucks the flowers off their stem now, you have nothing to fear

a loose scarf drapes over our legs if only truth could be so transparent i wear my wound like a sword while she calls checkmate on a cheeseboard

the mastery of the ignored time, never quite dulled this longing of mine exercising my vocal cords it seems the whole world heard me yet why do I still feel so unseen?

tapping away on a keyboard the to-do lists never end she said she would come back tomorrow— but tomorrow never came.

Cade Yoshioka

Cade Yoshioka is an emerging poet from Castle Rock, Colorado. He is currently an MFA Poetry student at Queens College in New York. His other works can be found in Hindsight Journal.

ghosts exit a right earlobe pierced by a needle they are cochlea fluid leaking from a waxy mouth

we garnets mark transformation; haunted bodies inhabited by voices of a movement cry out like the first brick thrown at Stonewall

we’ll appear on a platform glitter-bathed, turned upstage faceless to the audience

hail us touch our backs

wipe your tears with our boas grieve our lost names

you are the lapidary cutting the garnet of yourself

Rowan Aldridge

Rowan Aldridge is a queer engineering student and amateur poet trying to find the right balance between art and life. If she figures it out, she'll let you know.

On the brink of wild and wonder, between the scar-vines and the roses, is a lady divine, holding more than forbidden fruit,

Snakes and vines entwine her, move with her, as if to boldly say “This one is ours! And we are also hers, to do with as she pleases.”

Baying hounds are silent as her feet move through glades of trees lit by moonlight, love light, stirred by autumn breeze.

Walt Trask

Walt Trask is an emerging poet influenced by his upbringing in the Hudson Valley, New York. His work has appeared in Wingless Dreamer, The Ana, Tofu Ink, WILDsound, Ursa Minor, University of California, Berkeley Press and in the collection The Lightness of Being, The International Library of Poetry. He lives in Palm Springs, California and San Miguel de Allende, Mexico.

The dog lies on the cool ceramic floor one open ear periscoping the rustling in my bed

My tongue brushes your shoulder

Moroccan salt lingers for the first time then coffee rivers my lips chocolate tobacco licorice.

You know?

Someone ought to bottle the feel of my hands against the navy silk shirt draping your torso last night, smoother than marble in museum halls igniting one thought to the next.

We traverse Florence in my head as I stare at spiny Ocotillo branches in my garden wanting to embrace them thorns and all.

Harder still to pull back to wait for rare orange blooms. Me trying to be as patient as undelivered mail feeling like the empty space inside an unopened gift holding only anticipation.

Mezi

Mezi is a Canadian-based poet, photographer, and Zen student. His work appears in literary journals across Canada and the United States, exploring themes of relation, identity, ecology and social justice. In 2017, he published Medellín, a photopoetry chapbook for the benefit of refugees. Learn more at mezi.site | @mezi.ig

IFor a time, I sought formations in symphonies and fine affairs to see them slipping through my fingers the day we settled across the harbour. You keep reminding me of our future life downtown. I’m not always sold. Like the day we spotted Ironman dragging his life along the sidewalk. He stumbled like an olive branch, stared me down like ransom. Or the time I saw Lady Granville as I crossed her bedroom unnoticed. I can’t tell you what they saw. It’s apeshit. The same ape that holds me so close to split the nuclei of my sitting bones. Or the ape that keeps her shit together. I think her name is Ardi.

I see you in her porcelain eyes like the fusion of a sleepy daffodil and the wakeful hum of silence.

II

I’d like to sit with no toys, or make a run for the mountains. Ironman beat me to the crosswalk. I stopped and let him go.

Lucy Coats is a bisexual writer and poet living in Northamptonshire, UK. She writes about queerness, war, goddesses, the minutiae of the countryside where she lives, and the effects of patriarchy on the lives of women everywhere. In 2024 she was shortlisted for the Bridport Poetry Prize, and has been published in many magazines and literary journals, including Clarion, BQW and The Winged Moon.

If I could start again, I would ask the Fates to send me lush-bodied witches with midnight hair, and pillow soft breasts to lay my head in the long light of solstice dawns. A back strong as oak boughs yet supple as willow fronds, so that I could dance fandangos without pain; a gut that could ingest the heat of scotch bonnets and laugh; a heart that loves without fear of becoming burnt sugar in a neglected copper pan. I would demand a life that fitted me like green velvet gloves on a plump holy whore

Isabel Grey

Isabel Grey holds an MFA in Creative Writing from Western Colorado University. She is an assistant editor for Terrain.org. Find her writing & art on IG: @greyauthor222

Can fantastical beings sympathize with my fantasy? I struggled to believe it when the TV aired The Fairly OddParents episode, “The Boy Who Would be Queen.” I was writing letters to fairies then Post-it notes inscribed in my tiniest-cursive handwriting. In hindsight, Mom worked overtime in her imagined roles: Santa Claus, Tooth Fairy, and now a whole community of fae who lived in the Croton leaves bordering the reddened chain-link fence of our side yard.

It was hard to believe I could ask much more than What do you eat? or Is that your ring in the grass? Especially when the answers came back in a penmanship that uncannily resembled my sister’s. It was too dangerous to request Dear Fairies, please change me into a girl. Even folded so many times it resembled a Chicklet, origamied against prying human eyes, buried in the humid dirt along the property line.

My cheeks blushed at the thought because on TV, Timmy Turner, the main character of The Fairly OddParents, said, “Why would anyone want to become a girl? What a dumb wish!” His fairy godmother, Wanda, steamed crimson at her godson’s misogyny and proceeded to zap him with a yellow magic ray, resulting in Timmy’s change of sex.

I remember where I was in kindergarten when despair sank into me, thinking of that episode. A kind of FOMO, like shadows stretching

across the school sports field during P.E.

It was hard to believe that one day I would enjoy physical activity after my wish to become a girl was granted not by fairies, but by my own wandless hand.

It’s easy to believe that little boy eventually grew her wings.

Cara Sullivan

Tired eyes rise, unmoved, my reflection cleaved in two. Slick, fissured glass mirrors bones split, splintered jagged halves of being swimming in mercurial pools. A creeping patina, meant to skim and shimmer over truths laid bare but not mine.

One half, a sleeping sylph suspended in Eden’s ether a dreamscape where Asteria has spirited away a fistful of my heart. Throbbing, breathless, the stolen flesh weeps joy. I wade in its scarlet pool.

The other: gaping, restless, thrashing wild. Screaming silent beneath silken chains that bind these bones. There I wait in agony for Asteria to return.

To gather the bloodied remains of my heart in her wings, to fly it home, to place it in the palm of the hand that made me feel, to make me whole.

Rhy Anderson

Rhy Anderson is a queer, agender, sound engineer and immigrant living in Berlin. Rhy also organises for several poetry events including Petty Slam and Berlin Spoken Word. Rhy gets gender euphoria from the artist bio that must be written in the 3rd person.

//The friend who moved away in fourth grade needs to take out the trash//but isn’t ready//

Standing in a hallway where time does not pass it leans

Working hard to make a river from a puddle//beating time as if//shaking out a rug//in a sandstorm// //if we are holy by deed and action let us aim to do nothing long enough that the light of heaven forgets to swallow us// To hope that this world chokes on us// cigarette smoke stuck in the lampshade//chicken bones in the garbage disposal//

Give me pudding for a backbone and two arms just long enough to hold us in the twilight perimeter of our block Bric-a-brac’d beside //Those parked cars with weeds in their hubcaps// The friend who helped me pack when I moved away from home for the last time// takes out the trash and we kick the bag apart//beating ourselves out of it// my cans in your Hermes heels//your scraps and tangled hair//a mess//

we have learned not to tidy ourselves//We’ve learned to hold this mess//us//dusk spilled and shimmering things// lost luggage//in a drowning red sunset //Now a subtropic suburb// //Now a quiet Somewhere// //watching God become a forgotten bike//rusting in the yard// Our shadows slippery in the neighbourhood grass Echoes of light dappling our feet as we run

Timeless//ghostly//uneventful Light catches us//forgets us// And we do not care //our footsteps a kiss

on the face of the world//

//Let tonight be a nothing worth writing about//

//all our friends get home safe the way they used to//

//all our friends wake up tomorrow// and here I am tonight where time splits open like a soft confession with a tap on your window to ask you

//If you are done being holy//

//And if god doesn’t mind// Would you like to go outside to play?

Tony Douglas is the pen name of a Queer activist and cancer survivor in Chattanooga, TN.

I looked for someone quiet. Mid-twenties. Slim. Willing to lie still. No talking. No touching back.

The man I found was all of that. Compact. Calm. Professional. He took his clothes off like he’d done it a hundred times for a hundred people.

He lay on his side, back to me, the covers pulled down to his waist. The bed looked like it belonged to him already. Like he’d been sleeping there for years. I got in behind him. My body bulkier now—hormones had packed on weight I never asked for. There was more of me than I wanted, more than before. But I aligned myself anyway. Chest to his back. Legs tangled in his. Soft against soft. I let myself settle, skin to skin, my ever-flaccid cock resting between the cheeks of his ass just enough pressure to remind me I was still here. It never hardens anymore. Nerve damage left it not just flaccid, but shortened too. A pale memory of what once stood. The surgeries took the cancer, and everything that came with it.

I reached around. Found his cock, already warm. One hand working him while the rest of my body stayed still. I didn’t want anything else. Not from him. Just this. His body told me everything. The way his thighs flexed. The twitch of his stomach. The way his breath caught and stuttered. I felt each shift as if it were happening in my own body. Through his cock, I listened. Through the nerves in my hand, I remembered. The foreskin moved easily. Smooth over the head. Each stroke a little longer, a little firmer. His hips started to move not toward me, but upward, caught between reflex and permission. His breath came faster. His cock thickened. His body tightened.

And then: the jolt, the spasm. His spill, hot and sudden, across my hand. Some on the sheet. Some on my wrist. I didn’t wipe it away. I let it sit there. I wasn’t sure if I wanted to clean it, rub it in, or just feel it cool against my skin. Eventually, I touched the salty liqueur to my tongue, bringing back life to a distant memory.

He went still again. His breath slowed. I stayed beside him a little longer, listening to the weight of the silence settle around us.

I said his name, thanked him, and kissed him. Then I rolled away, reached for a towel. Wiped my hand. Pulled the sheet up over his shoulder.

A young man. Brave enough to lend an old man what was taken from him.

Sleeping a well-earned sleep.

What I Gave

He said his request had something to do with cancer and was strange. It wasn’t. Not in sex work, anyway. It was unique. It was oddly specific, but not weird. The half-dozen clients I turn down every week they’re weird.

He wanted someone quiet. Mid-twenties. Slim. No talking. No touching back. I knew that type of request. I’ve gotten versions of it before.

I was available. Professional. Calm. I took off my clothes like I always do: not with indifference, not with shame, just readiness. He didn’t speak much, just made space on the bed. I lay on my side, back to him. Still. Neutral. The rules were clear, and I like when they’re clear.

Then I felt it: his chest, his arms, the slight press of a body that didn’t want to take, just… inhabit. There was nothing urgent in it. No hunger. Just presence. His skin against mine, like someone remembering a song they used to know.

He reached. His lubed hand moved with practiced ease. I’ve been touched badly before. This wasn’t that. This was different. Focused. Careful. Not performative. Not for me, exactly but not against me either. My body responded like it was supposed to. It always does. But something passed between us something electric but muted, like static trembling in the air before a storm.

And when it happened when I came he didn’t react with triumph or embarrassment. There was quiet. Breath. He didn’t wipe it off me. He might have tasted a bit, but didn’t say anything. Just held the silence like it was part of the service.

And that’s when it made sense: he hadn’t hired me to give him a handjob. He’d just jerked himself off with my dick.

Eventually, he shifted. I felt the air cool against skin where he’d been. Then he turned me over, and for the first time, he said my name. Thanked me not like a trick who’d just gotten off, but like someone borrowing something valuable and returning it intact.

“My pleasure, truly,” I said. My fingers touched his face light as breath. Just once.

He stood to dress, and I let myself look. He wasn’t even that old. Mid-forties, maybe. He was big. Not broad or built just soft, everywhere. His belly curved outward in a heavy, round swell. His thighs pressed thick against one another. Even his arms had the weight. But his chest wide and padded with silver hair

caught me. Even my recently spent cock gave a futile twitch at the sight of it. Not what I expect to respond to. But I did.

He wasn’t someone I’d sleep with outside of work. Not slick, not sculpted, not lithe. But in the right room in the bear gatherings he’d be a prize. All of him. Wanted for exactly what he is.

I let my eyes drift downward. His cock hung thick but softened by time. Still, I imagined it rising, with a little coaxing. A slick hand. A whispered name. I bet I could make him moan. But I didn’t. He’d asked for no touching and still radiated that energy. He also hadn’t paid for that.

He pulled on his shirt, and I indulged in some post-coital sleep. In a couple of hours, I’d be back here satiating my own sexual appetites, but I wouldn’t forget the man who used me to jack off.

A.D. Tilley is a queer poet from Arkansas, currently residing in the Northwest portion of the state with her wife and their three unruly cats.

For Beth

I can feel the last five years in the muscles tightening in your back as you dip my body under the imaginary waves.

The salty, sun-screened lips brushing mine, joy, bubbling, bursts through the gaps in shining teeth as the speakers reverb with the threats of our youth. You pull me back on my feet, dazzling like the rainbows in this sweat-scented heat. Not new, not necessarily reborn, but healed.

The street preaching continues in shouts, but you smile, and I take your hand, and we continue on.

Oleg Olizev

Oleg Olizev is a Russian-born writer, poet, and visual artist based in Manhattan. He left Irkutsk, Siberia, in pursuit of artistic and personal freedom. A lifelong creator, he spent years developing a private body of work novels and paintings that remained unseen until recently. In May 2025, he submitted his work for the first time, and within months his writing appeared or was accepted for publication in BULL, Fjords Review, Audience Askew, Panorama: The Journal ofTravel,Place,andNature, TheArgyleLiteraryMagazine, Half and One, The Ana, Night Picnic, Neon Origami, and Untenured. He has completed two novels rooted in queer experience and sexual exploration and is currently seeking a publisher. His work is visceral, boundary-pushing, and committed to the unspoken.

They walked up on us outside the store. Thomas was smoking, and I was chewing a bruised banana.

“Wild,” one of them said. Tall guy, suit, tie, and white shirt. He wasn’t smiling. Just staring.

“What’s that supposed to mean?” Thomas asked, not looking away.

“You two,” the guy said. “You look like a gospel someone left in a shopping cart. Like something you don’t want to see, but can’t stop staring at.”

The second guy stood a little behind. Lean. A poster-boy cop, straight teeth, buzz cut, calm face, telling you to shut up and behave like he already knew how this would go. Name was Tolik. He held out a beer and said:

“We’ve got Wagner, drinks, and one hell of a filthy offer.”

Max’s apartment had ceilings like a museum high and cold. Books everywhere. Wagner’s “Ride of the Valkyries” blasted from the next room. Max walked in, tossed his blazer, and changed into a monk’s robe. Not because he was holy because he liked theater. Then again, who knows?

We sat in the kitchen. Tolik poured beer into heavy mugs. Could’ve just passed the bottle, but he moved like he was curating a show. Thomas watched him with eyes half-shut, like he was waiting to see who’d undress first. Max sat down next to me, placed his hand on my neck, and sucked my tongue like he was pulling something out of me. I couldn’t breathe. Thomas laughed and raised his bottle.

“Let’s drink. Before the filth begins.”

We drank. We smoked. Thomas unzipped and slowly pulled his cock out. Tolik dropped to his knees without a word, like it was instinct. He went down deep and sloppy.

“Neck like a gymnast,” Thomas said.

“You’ve bent deeper,” I said.

Max touched my hand.

“Get closer,” he said.

I lifted his monk’s robe. It wasn’t a dick; it was a weapon. Long, wide, too thick for my hands.

Max licked my ear slow and hot. It thrilled me. I couldn’t breathe right. His tongue started working all over my ear, wet and insistent. He pulled me in, tight so tight I thought my joints might pop.

Thomas kissed Tolik mouth-to-mouth. Tolik didn’t flinch. Just breathed like someone was telling him everything would be okay.

We didn’t speak. Only hands on skin, breaths breaking, the chandelier casting shadows across our stomachs.

Max kept whispering I was beautiful. Called me baby. Bit me hard. I wasn’t used to the biting but it worked.

My ass was seasoned, but not for this it hurt like hell. He moved slow but firm. Pain and pleasure tangled until I couldn’t tell them apart. Max was relentless he’d been fucking me for an hour, and I was still trying to figure out why I like it.

Thomas was fucking Tolik on the floor. Tolik’s eyes were gone rolled up and he moaned like an animal. He grabbed Thomas’s wrists like if he let go, he’d disappear.

Later we switched. Or maybe not.

I was on my back, my thighs sticky.

They were smoking, and kissing all of it at once, like nothing else existed. Max said, “In the end, flesh always wins in art.”

Tolik drank straight from the bottle, looking at the ceiling like it might start moving. Thomas ran his hand through my hair. I just breathed.

Then again but this time I’m sucking Tolik off, Max is fucking Thomas, and Thomas is screaming from both pain and pleasure, like I’ve never heard him before.

Now he’s on the floor, breathless, like a corpse, lying in a pool of his own cum.

I bend down, kiss his back slow, greedy and slide my fingers over his hole, still wet, soaked, raw.

“See how Max fucked you?” I whisper. “Feel how deep he broke you?”

I say it, and the more I speak, the more the heat coils inside me sharp, sick, laced with control and I start fucking Thomas. He moans, then starts crying.

After that, we were smoking again and kissing, pressed against each other, no rhythm, no rest, just heat, breath, and the bitter weight of our bodies.

We drank more. Beer turned into wine. Wine into some burn-your-guts-out stuff Max pulled from an old pharmacy bottle labeled 70%. He called it “extract of the sacrificed.”

Tolik didn’t say a word. The only food was a bag of sunflower seeds Thomas brought.

Max started reading from some book he liked. Whispered and laughed. Then he stood up and threw the windows open. Wagner blasted like the world was ending from the roof down.

At first, we thought he was just drunk. Then we thought it was a performance. Then it turned into something else.

He started speaking Latin real or fake, who knows. Called Thomas “soldier of the Antichrist.” Called me “prophecy bearer.” Called Tolik “traitor of emerald blood.”

He climbed onto the table in that wine-soaked monk’s robe, shouting he was gonna jump out the window like a falcon prove God exists, because he was God.

Tolik went pale. Tried talking him down.

“Max... Max, please…”

But Max was already preaching to the ceiling.

When the ambulance showed up, he was growling. Called the medics “insect’s secret police.” Bit one. Spit on the other.

Thomas stood smoking by the window. I was holding a blanket, not sure who it was for Max, or me.

They strapped Max into a restraint jacket and wheeled him out. He looked back at us from the stretcher — eyes lit like he’d just brushed against heaven.

“Don’t let them shut the windows,” he said. “Let the wind bear witness.”

When the door slammed and the hallway went dead quiet, Tolik sat down on the floor. Right there in the entryway. Didn’t cry. But his lips were shaking.

“I’m sorry,” he said. “I didn’t know it would come back.”

“Does it happen often?” Thomas asked.

Tolik looked up, eyes glassy.

“Rarely,” he said. “But when the DTs hit like that... there’s no stopping him.”

He got up. Washed his face. Grabbed his briefcase.

Looked at us like we might disappear if he blinked.

“You can stay here overnight or longer. No food, but the fridge works. Books read whatever. Sleep wherever.”

“And you?” I asked.

“I can’t be here. Not without him. The whole place hums. I’ll go home.”

He put his shoes on. Paused at the door.

“When you leave, just pull it shut. The latch will catch. I’ll come by tomorrow, check in on you.”

I sat on the floor by the bookshelves. Naked, wrapped in a blanket. A wine glass in my hand. Empty.

The music was still playing. Wagner.

David Meischen

David Meischen is the author of Caliche Road Poems (Lamar University Press, 2024) and Nopalito, Texas: Stories (University of New Mexico Press, 2024). Anyone’s Son, from 3: A Taos Press, won Best First Book of Poetry from the Texas Institute of Letters in 2020. A Pushcart honoree, with a personal essay in Pushcart Prize XLII, David lives in Albuquerque, NM with his husband Scott Wiggerman.

Zero gravity is what it comes to : this incessant petition for a succulent mouthful.

Yearn is the verb that defines me : thirsting, emptied, weightless again.

X-rated tussles with the hairy-bellied one : does he want what I want while my throat is full with him? Groaning, vampiric, I want to choke on satiation : his blood my blood upwelling so soon I’m back to less than zero, tailgating, chasing the next spill : I sing for another go, coax the aging body desperate to reverse the decline that’s in me : I

quibble with the maker do I believe in a maker? keep me in the pink. Bloodrush this desolate shell I wake inside like Orpheus, vacant days without Eurydice, nohow minutes ticking by for looking where he promised not to : this man I have become these airless arid lonely days lusting for time-capsule magic I’m knocking at the mandate that says all creatures age and die. Janis Ian’s on the radio. Long ago and far away the world was younger than today.

I don’t want liftoff : I can be angel-winged when I’m dead : I want helter-skelter days again romping naked in a cove splash-full of bare-butt friends : good ol’ carpe diem days, a dick in my mouth to satisfy the falcon-beaked hunger that was in me. Is in me, effuse and dissipating these days I cry me a river. Dinah sang my blues so well so long ago : someone’s Chevy radio theme-songing the dark : heartbreak balanced on the hood ornament, lighting this American boy’s dream of living in the flesh.

Hickory Madeline Avila

Madeline Avila is a 10th grade student at the Harker School in California. She loves to write about current-world problems and express her opinions in a way that is powerful and can be heard, taking inspiration from writers like Margaret Atwood and Ray Bradbury after developing an interest in banned books. Since she was a little girl, she always loved writing and got into it at four years old, specializing in realistic fiction and romance. Recently, she started a writing club at her school to help support students who are equally as passionate as her in the beautiful art of literature.

I never thought I would find myself hiking back up the Washington Crest Trail, let alone with anyone besides EJ. The wind bristled my hair, crisp and autumnal, just as it always did, and a musty and earthy scent filled my nose. The trail was as I remembered: dry earth beneath my feet, the crooked arrow sign pointing upward, the fallen river birch unmoved in a year. Somehow, it was the same, but so different.

“Come on, Lily,” I beckoned to the little red-haired girl following me close behind as she made her way up the steep part of the trail. “We’re almost there.”

Eventually, we came upon a dense thicket of shrubs. It had overgrown since my last visit, EJ no longer tending its maintenance. I slowly plucked one of the flowers and twirled it between my fingers before pushing through the bushes, holding Lily’s hand with my other hand. I had never taken anyone to our hideaway before.

After a moment, the shrubs paved the way to a previously trampled path with little dried footprints of very distinguishable Doc Martens that led over to the hickory tree. Subconsciously squeezing Lily’s hand tighter, I edged my way over to the trunk. This tree belonged to us. Anyone could have known that from the prominent ‘EJ + K’ etched into the bark. Part of me hoped the day it healed would never come, because that would mean it was time to let go. Coming back here, the memories rushed back to me. The late afternoons that the two of us would spend here, EJ flipping through the Harry Potter series for the millionth time while I drew in a pocket sketchbook with a charcoal pencil.

I chewed my thumbnail, willing the tears away. Today was special, but not the good kind. Exactly one year ago today, Ethan James Galko died. And it was my fault.

I don’t want to remember that day. It’s hard to remember that day anyway; it’s something that I willed myself to forget. We had never fought before in the 13 months that we knew each other. It was just a bad day for me, and I wasn’t ready. EJ wasn’t pushing me at all. I just… lashed out.

“I didn’t mean it like that! Kit- Kit!” he begged, trying to catch my hand as I stormed up the stairs and slammed the door in his face. I heard his hand slam into my door. “Kit! Kit, please. Please, I just…”

“I told you! I’m not fucking ready!” I snapped back from the opposite side of the door.

“I’m not trying to push you, I just want to be with you! Please…”

“It’s not that simple!” My voice reverberated through my bedroom. “They would never accept me! My family isn’t like yours.”

EJ fumbled around with my door handle a little bit before the rattling stopped and all I could hear was his soft, heavy breathing from outside the door. I could always tell when he was upset. He was crying. I hated it when he cried. “And what, you just want to hide forever? Like I’m just some friend that you just happen to spend time with? Don’t you know how much that hurts me?” replied EJ, his voice breaking a little bit with each silent sob.

I could feel my heart clench, and I knocked my head against the door as frustration bubbled up in my chest. “You think I don’t want to tell them? Do you think that I’m happy hiding this? It’s not about some ‘not loving you enough’ bullshit! You can’t even begin to comprehend what it’s like to be rejected by the people who are supposed to love you unconditionally!”

“Well, I love you! Doesn’t that mean anything to you? I feel like I’m losing you every time I come over and you just pretend that I’m nobody! If you’re ashamed of me, just say it.”

For a while, I just stayed silent, letting the vexation silently froth. I wasn’t ashamed. I was just…scared. I was terrified that things would change. That I would be treated differently if they knew. Looking back on it, I should have just told him. He would have supported me and loved me regardless. But I just couldn’t lose. And eventually, I burst.

“I am not ashamed of you! Stop turning this around and making it all about you and your own shitty life! It’s not my fault that you couldn’t just stick with your own fucking gender!”

The second the words came out of my mouth, I knew that I messed up. It was silent for a minute before I heard EJ running down the stairs and out the door. I couldn’t bring myself to follow him. I felt like I didn’t deserve it after what I had just done. So instead, I just slowly sunk down to the floor and hugged my knees to my chest.

*

The next day, my mother told me that he was dead. EJ didn’t go home that night, and in the morning, they found his body beneath our hickory tree, right by the engraving of our initials. They said that he had overdosed on his antidepressants.

*

“Is this it?”

I slowly turned around to look at Lily and nodded softly.

“Yeah. This is the one.”

At the hickory’s trunk, I knelt and traced its shaggy bark with my fingers. Lily sat down beside me, and I let her lean her head on my shoulder.

We stayed there for a bit, just watching the Virginia wind rustle the hickory leaves and remembering. I’m not really sure how long, but it was long enough that the sun began to sink below the horizon. Eventually, I sent Lily behind the shrubs first so I could have a few minutes alone to myself. For a moment, I just played with the strings of my sweatshirt and sat underneath the shade of the tree.

“I told my parents. They were… shocked. But I think I’ll get through it.”

Only the delicate rustle of leaves replied. That was enough. I shut my eyes for a second and just felt the breeze on my skin. There was so much that I wanted to say, but I just didn’t know how to say it. I still blamed myself, even though his family told me that

it wasn’t my fault. So instead of talking more, I just gripped the material of my pants and started crying. I guess it was the first time that I had just let myself… feel.

“I miss you,” I choked out quietly. Only after I realized how much time had passed, I gradually regained my bearings, stood up, wiped my face with my sleeve, and put my hand over the engraving of our initials. I closed my eyes and took a few deep breaths.

I pulled a sketchbook from my back pocket one I’d never show anyone, filled with private sketches of him. I gently laid it down at the base of the tree, open to the last page with today’s date, before shoving my hands into my pocket and slowly walking away, rejoining hands with Lily.

“Let’s go home,” I whispered to her, gently rubbing the back of her hand with my thumb. She nodded slowly and we both followed the footprints back through the shrubs and onto the Washington Crest Trail, leaving the final, perfect charcoal drawing of EJ: he was sitting under the hickory tree reading the Prisoner of Azkaban, grinning in his red sweater and black beaten Converse.

Jessie Scrimager Galloway

Jessie Scrimager Galloway is an adopted, queer, disabled masculine-of-center poet, community organizer, educator, and development consultant for nonprofits focusing on social change and cultural equity. She formerly served as Poetry Editor and Development Director for Foglifter Press, and she is author of the chapbook Liminal: A Life of Cleavage and the full-length collection, not my daughter, published by Etched Press in 2024. She loves her wife’s fried chicken and enjoys riveting conversations with her best editor: Snacks, a wily, polydactyl, orange cat.

It’s October in Portland, 2011, and I’m sitting opposite my bestie, Will G, in the cracked red-vinyl booth at Patti’s Diner.

We’re eyeing a group of guys, doppelgangers multiplying an odd assembly of lumberjack plaid, two- to three-foot beards, Velcro-pocketed safari vests, army canteens swinging from utility belts. Not gonna lie we’re straight-up judging this gathering. Eavesdropping,

we learn it’s Bigfoot Society’s annual gathering. Some drive eight hours to bust out castings of prints, hand-drawn maps, green circles of sightings, tufts of fur encased in clear plastic boxes meant for display: plaques with dates.

They all order coffee, black. One asks for six eggs over easy with rye toast. Another: same, but sourdough.

Our check sits on the table, but when the server warms our weak coffee, we add a piece of apple pie to buy time.

We’ve just been discussing our exes and the dating fiascos that followed.

Will says, “Sasquatch could exist. Who are we to say?”

I say, “Who am I to diss people who search with certainty, believe in something with passion?”

Everyone’s got their own elusive beast. We all chart maps, keep small signifiers of our trails toward big finds.

Are dating red flags really green-circle glimpses?

I want to believe. I want to relax my jaw, stop baring my teeth, unscrunch my brow, and know the scary beast will soften its eyes and reach out its paw to me, in recognition, in peace.

Svetlana Lukyanova

Sveta Lukyanova (she/her) is a writer and co-founder of the writing courses and community for women* WLAG (Write Like a Grrrl) Russia. Her short stories have appeared in Oranges Journal, Voidspace Zine and various Russianlanguage literary journals. She wrote a book about growing up queer in a small town in Russia and a later-in-life lesbian coming out, titled I Do Nothing Wrong, published by the underground small press Papier-Mâché in 2023.

I bought the same laundry pods you used to have, by accident. They were on sale. I washed my whites T-shirts, panties, socks and when I was taking them out of the dryer, I brought a warm T-shirt up to my face and just stood there. And you were right in front of me. And all day I felt this excitement.

When I got off the bus, we hugged awkwardly, rather briefly. Like people who never sent each other messages late at night. Then we went to your place. The whole room carried your scent. Like those pods.

And I didn’t know what to do. I bought a big pack; I couldn’t just throw it away. But how to live with you around me all the time? I forgot. I thought I was done with it done with you. That’s why I bought the pods. I didn’t think it would be a problem. I hadn’t looked at those pods in two whole years. So yes, it wasn’t entirely an accident that I bought them.

I washed my face masks. That was bold, I know. Every time I entered a store, the post office, any building, I took a sweet breath of you. My heart fluttered, like when I used to run to the third floor where Tim had classes walking past the door, waiting for him to come out. Anticipation. Anxiety. Thrill. That’s how it all started, you know. One day, he did come up to me. And he said hi.

You won’t come out, though. You won’t be in the store or my post office; you’re in another city. It was always like that with you never easy, never close. Another city. Somewhere else entirely. You have a headache, you put on a skirt, you leave for work. You tell me to leave the keys in the mailbox. I don’t even

want you to be in my post office. It’s good that you’re not here. But the fragrance is.

It turns out the scent doesn’t last long on masks. The first breath, yes, but then it’s just air. Regular discomfort drops of sweat under the nose. So I washed the bed linen. Like you used to do. On the day I arrived, we had breakfast and you left for work. I lay in your bed, meant to sleep, but I couldn’t stop I couldn’t, I wouldn’t, I wouldn’t. The smell captured me, tormented me, curled around me like smoke. It was embarrassing to masturbate, but impossible not to.

I hoped that I’d dream of you. The way you were. Those arms and hair and everything. But I dreamt of dogs running.