PERENNIAL

THE UNDERGRADUATE ENVIRONMENTAL JOURNAL OF BERKELEY

We are proud to present the seventh issue of Perennial. We welcomed teams this semester, and we are, as always, both impressed and grateful we want to extend our thanks for envisioning and executing a unique requires both creativity and dedication, and our writers excel on both gratitude for framing our seventh issue with thought-provoking visuals engaging multi-media experience.

This particular issue highlights recent progress in the environmental environmental problems in our society are blooming. We continue to and involve all facets of global society from music to technology, incarceration, economy. The scope of groups that interact with these topics range from and individual peoples—and for that reason, we hope our publication diligently report on the science at the core of environmental issues facing

Alongside our featured articles, we are happy to present several opinion crafted thoughtful responses to timely environmental issues. As a journal, to publishing recent research from undergraduate students, and our seventh both UC Berkeley and UCLA students.

We strive in our publication to showcase and encourage collaboration institutions, and the multitude of sectors working towards greater knowledge communal effort necessary to tackle environmental issues.

Finally, thank you to our readers for your time and attention. We hope Perennial both academically stimulating and personally motivating.

welcomed plenty of fresh faces to both our editorial and design grateful with the output from our members. To our staff writers, batch of stories—environmental journalism is a task that fronts. To our design team, we want to express our thought-provokingvisuals that feed life into the articles and accumulate into an environmental movement at a time when conversations around to explore a variety of environmental issues that affect incarceration, gender, literature, politics, and the from governments to corporations to local communities publication will resonate with wide audiences. Our writers facing the modern era, while maintaining a strong

opinion pieces from our staff writers, who journal, we are also proud of our commitment seventh issue includes contributions from collaboration between research fields, academic knowledge and justice, emphasizing the hope you find this new issue of

Jacqueline Cox, & Thuy-Tien Bui Team

Jacqueline Cox, & Thuy-Tien Bui Team

8)Hip-Hop and Climate Justice by

11)The Road to a Sustainable Forest

14)Conflict, Confusion, and Coexistence: by Cole Haddock

22)The Harvest Hereafter: Extraterrestrial

25)Barriers to Prescribed Burns

27)The Dual Nature of Hawaii’s by Sosie Casteel

30)Big Tech’s Enviornmental

32)Reimagining ‘Silent

37)How Data Science can Op-Eds

42)Climate Change Complex by Stella Singer

46)Climate Change by Mona Holmer

48)The Ethics

Exploitation?

53)Raising Research

58)Understanding Socio-Ecology: Comuna Jack Daley, 70)Traditional Controversies, Mutsun

75)Balancing Riparian

Forest Bioeconomy by Sia Agarwal

Coexistence: Fighting for Control on 8th & Harrison

Extraterrestrial Solar Power by Abby Wilber

Burns in California by Jessica Chan

Hawaii’s Tourism: Thriving Industry or Destructive Force?

Enviornmental Responsibility by Megan Mehta

Spring’ in the Twenty-First Century by Ben Bartlett can Further Marine Conservation Efforts by Paige Thionett

Change Behind Bars: Climate Change & The Prison Industrial Change in a Gendering Society: The Price Women Pay Holmer

Ethics of Animal Experimentation: Resourcefulness or Exploitation? by Elena Hsieh

the Alarm for the Willow Project by Ben Bartlett

Papers

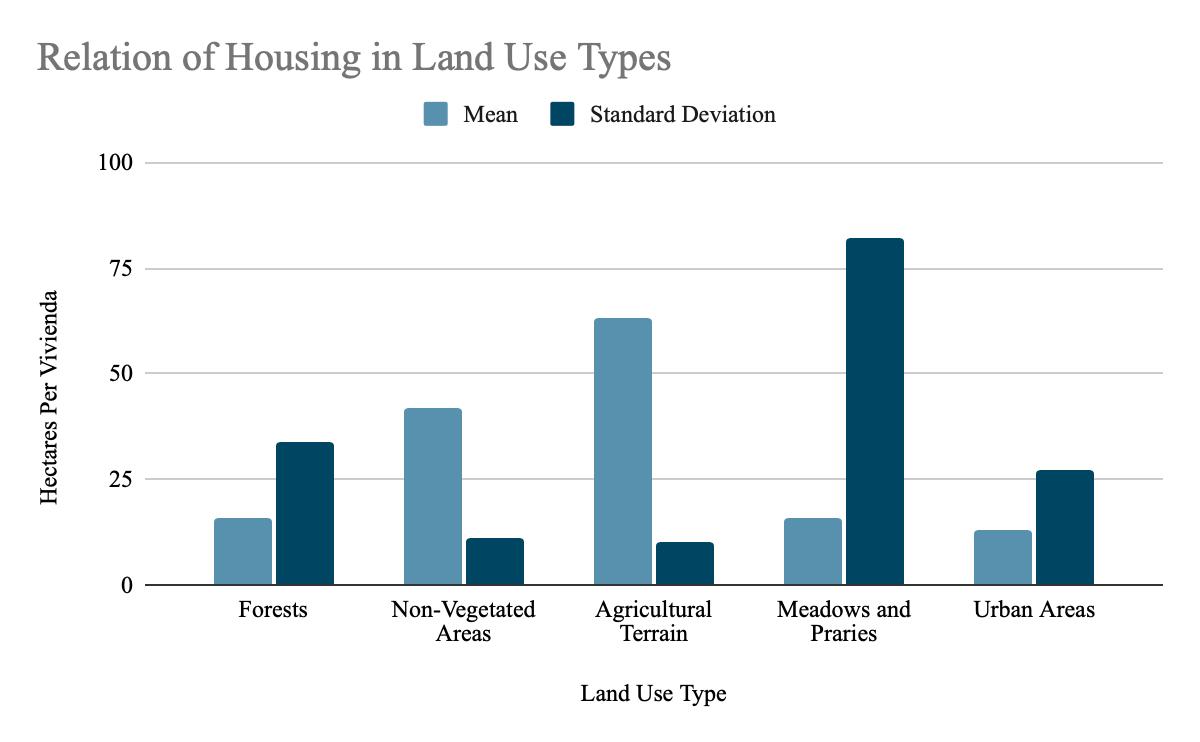

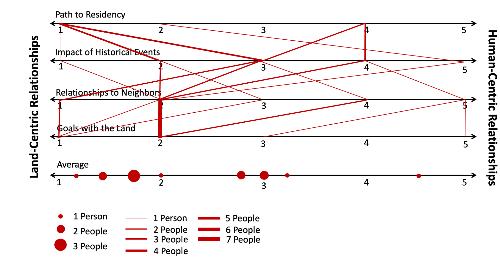

Understanding Ecological Impacts of Land Use Through Local Socio-Ecology: Proposal for Sustainable Land Management in the of Pucon by Emma Klessig, Myla Kahn, Henry Mahnke, Daley, Grace Boyd

Traditional Ecological Knowledge, Indigenous Burning Controversies, and Bringing Back ‘Good Fire’ by the Amah

Mutsun Tribal Band by Thuy-Tien Bui

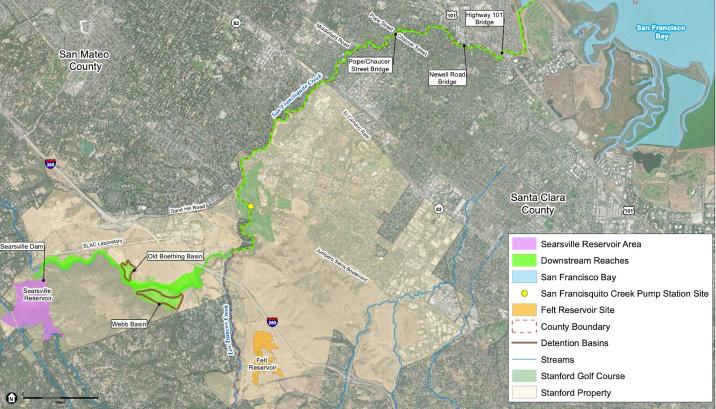

Balancing Community Flood Security and Free-Flowing Riparian Ecosystems by Ben Witeck

by ZORA UYEDA-HALE

by ZORA UYEDA-HALE

Listening to the radio, you bob your head as Drake’s “God’s Plan” booms from your speakers. Then suddenly, a new track starts playing. Instead of rapping about “Mahbed and my momma,” they’re talking about fossil fuel infrastructures and planted seeds. This genre is eco hip-hop.

From its inception, hip-hop music has represented the variety of lived experiences of Black and Brown people. Artists have created tracks about the prison-industrial complex, capitalism, and poverty. Today, they rap about the climate crisis.

Hip-hop has evolved dramatically since its inception in the 1970s. The music has merged with different genres, become commercialized, and spread all over the world. However, hip-hop music maintains a few common threads: a rhythmic beat, vocals or rapping, and percussive breaks.

Eco hip-hop is no different. It incorporates these recognizable musical elements but speaks on topics of consumerism, climate change, and pollution. In particular, music connects communities of color together around these difficultsubjects, opening avenues to discuss radical change.

Although eco hip-hop is a fairly new genre, young people are already definig themselves within it.

From its inception in the Bronx neighborhood of New York City, young people have been at the forefront of hip-hop culture. In the 1970s, Black, Latinx, and Caribbean youth converged to create what would become one of the most popular music genres in the world. Hence, hip-hop has a big role in modern Black culture.

The Hip Hop Caucus, a nonprofitfocused on connecting the hip-hop community to the political

process, honors Black resistance in their work. Whether it’s around voting rights or climate justice, Hip Hop Caucus empowers young people, who resonate with hip-hop culture, to take action. Russell Armstrong is the Policy Director for Climate and Environment at the Hip Hop Caucus.

Based on hip hop’s origin story, he commented on music’s strong influenceand function in Black history. “Music is already a part of [our] own identity,” Armstrong explains. “As Black Americans coming from the slavery days onwards, [music] was a way for people to come together, to organize, to socialize.”

Therefore, for Black youth in particular, hiphop creates belonging and familiarity. In the Bay Area, Youth vs Apocalypse (YVA) is a group of primarily young, Oakland-based climate activists. They use hiphop to organize, change the narrative, and push for policy. The Hip Hop and Climate Justice committee is led by Aniya Butler, an Oakland high schooler and longtime organizer with YVA.

Since the committee’s formation at the start of the pandemic, Butler has led many youth workshops on topics like rapid songwriting, creative writing, and spoken word. Reflecting onthe impact of these events, she notes, “Having a space like Hip-Hop and Climate Justice allows that sense of this is something I’m familiar [with],” Butler recalled, “This is something I can connect with [as a young person of color].”

Creating these spaces in the environmental movement is of the utmost importance. Many young Black and Brown activists face the brunt of pollution and climate change. This racial inequity is due to environmental racism.

Jim Crow,the Anti-Black system of segregation, discrimination, and violence, supposedly ended after the Civil Rights Movement. However, sixty

years later, some activists are labeling environmental racism as the New Jim Crow.

Dr. Robert Bullard, known as the father of environmental justice, is recognized as one of the firstpeople to defineenvironmental racism. In his book, Dumping in Dixie, Bullard states that environmental racism is “any policy, practice or directive that differentially affects or disadvantages (where intended or unintended) individuals, groups or communities based on race.”

This inequity can be, and is often, intentionally structured. For example, the EPA has found that 71% of Black Americans live in counties that are in violation of federal air pollution standards, as compared to 58% of non-Hispanic whites. Consequently, Black Americans have a staggering 36% asthma rate.

In terms of natural disasters, only 50% of Black Americans own their homes, making them susceptible to permanent displacement. This urgent issue was a part of the reason why the Hip Hop Caucus began environmental political mobilization. Their “Think 100%” campaign was a direct product of the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina.

Fyütch, a Grammy-nominated hip-hop educator, reflectedon his awareness of environmental racism. “The older I’ve gotten, [I] start[ed] realizing things like cleanliness, food availability, green spaces, and neighborhood functions are hit hardest [in Black communities].”

“Now you realize everything is affecting [us] down to what we eat, how we eat, what’s being promoted to us, [and] how much things have changed since we were younger,” He continues.

Voices like Fyütch’s, who currently lives in the Bronx, New York, are usually overshadowed by larger, predominantly white, environmental organizations. These socially dominant institutions

“Eco hip-hop puts the power of storytelling back into the control of those most impacted. The ability to tell your own story is liberating.”

are only beginning to acknowledge these statistics and realities. Eco hip-hop puts the power of storytelling back into the control of those most impacted. The ability to tell your own story is liberating.

Butler affirmsthis sentiment. “Hip hop is an art form of resistance,” Butler said. “Resisting the systems that have been built to deprive us.” It’s more than music. It’s a form of protest and can create tangible change.

When Covid hit, big protests and marches were impossible. However, Youth vs Apocalypse recognized the continued urgency of the climate crisis. “This is not an issue that we’re forgetting about,” Butler said. “The climate crisis is here.”

So, they had to shift their tactics. Their firstmusic video, “No One is Disposable”, was created to bring awareness to the ways that corporations were still prioritizing profitsover people, even during a global pandemic. The video features people of all ages, but primarily young people, rapping, dancing, and holding signs of solidarity.

Three years later, YVA has released several music videos and an EP and led countless community events around hip-hop climate justice. “Youth are taking back our future,” Butler says. “[We] are advocating for a future where we have sustainability and these systems are dismantled.”

Hip-hop culture is often boiled down to music, but at its core, it’s social commentary. Fyütch explains, “Hip hop in its nature, always comments on society, it comments on neighborhoods, it comments on conditions.”

This commentary can be musical but also can be represented in visual art or other types of performance. The Hip Hop Caucus decided to channel this core element of hip-hop into a docuseries.

“Big Oil’s Last Lifeline” interviews frontline communities in Louisiana, Texas, and West Virginia, epicenters of the petrochemical industry. Armstrong explains, “I think that’s the whole purpose of [hip-hop] culture, being that it arises from many folks, many people engaging with it.” When more voices are elevated, the culture expands.

One last application of eco hip-hop is in the classroom. Fyütch has been a musician and spoken

word artist for his whole life. After interning for a school arts program during college, he realized these passions were very similar. “Spoken Word is very related to that same energy of hip hop,” Fyütch recalled. “It was more of an untapped lane.”

From there he never looked back, using hip-hop to educate on Black history, empathy, and sustainability. “[Hip-hop] meets kids where they’re at,” Fyutch says, “I’m meeting them with the energy that they understand. So in that way, it’s a perfect bridge to talk about anything.”

On top of self-expression, the work of Youth vs Apocalypse, Hip Hop Caucus, and Fyütch, demonstrate avenues for tangible policy change. Getting an individual to watch a music video, attend a workshop, or watch a docuseries may not seem impactful. However, systemic change starts with individual action.

As Fyütch points out, “the future CEOs of these corporations are in the classrooms right now.”

In urban settings, the city is the environment. Young Black people face everyday environmental racism in the form of food apartheid, air pollution, and contaminated soil and drinking water. Eco hip-hop gives a platform, vocabulary, and community to express lived experiences and dreams for a better future.

The paint on a building. A new sweater from the mall. The wheels of a car whizzing by on the street. There is one common thread: petrochemicals, chemicals derived from natural gas or crude oil.

The life cycle of petrochemicals is linear: Fossil fuels are extracted from the Earth, transformed into new materials and eventually emit carbon compounds. Currently, most products we consume operate on this model, a linear economy where resources are extracted, transformed into products, transported, consumed, then discarded.

The environmental impact of this economic model, where

resources are nonrenewable, is severe: Petrochemicals and their derivatives, including petrol gas, account for 46% of total United States carbon emissions.

Environmentalists are exploring the idea of the circular economy in which renewable resources, as opposed to finite, play a central role. Sage Lenier, the founder of the non-profit Sustainable and Just Future advocates for a circular economy in which resources experience multiple life cycles.

“My major tenets for the circular economy would be: an economy that is based in ser-

edge rather than goods, one in which resources are cycling, and an inherently low carbon, low resource extraction economy,” said Lenier.

One type of circular economy is the bioeconomy, “the production of renewable biological resources and their conversion into food, feed, bio-based products and bioenergy” (European Commission).

Forestry plays a central role in the bioeconomy due to its applications in almost every sector of human needs—such as construction, carbon capture and soil health. However, the path to a sustainable forest bioeconomy has pitfalls, such as overexploitation of forests and the net-zero environmental

benefitof replacing petroleum products with bio-based materials.

One pathway in the forestry bioeconomy is utilizing forest products in construction. Current construction contributes 40% to yearly global carbon emissions; 11% of these emissions are due to construction materials and processes. Emissions from the construction sector are on track to increase as 2 out of 3 people in the world are expected to be living in cities by 2050.

“The construction of our cities is predominantly done with concrete, steel, and glass. The extraction and produc tion of these raw materials are very energy intensive,” said Dr. Galina Churkina, a researcher with the Pots dam Institute for Climate Impact Research in Ger many (PIK). “This ener gy is currently produced from burning fossil fuels because this is the cheap est source of energy.”

Since wood is a carbon-se questering material, woodbased construction provides an alternative to carbon-in tensive building materials. One five-storybuilding could store up to 180 kilograms of carbon if made from timber. In fact, a singular cubic meter of wood holds about one ton of carbon which corresponds with 350 liters of gasoline.

If enough buildings were made of wood, a city could potentially function as a man-made carbon sink. The idea of cities as a carbon sink hinges on the idea of embedded carbon, “the stor-

age of carbon for long periods of time” (Think Wood).

“When we build a building, we transfer carbon that was absorbed sequestered by trees by forest into the city,” Dr. Churkina said. Her research posits four scenarios of timber in construction over the next 30 years. Across the four possibilities, at least 10 million tons of carbon per year could be stored in buildings; at most, it could be around 700 million tons.

application is as a soil amendment: When sprinkled across a forest floor,biochar improves forest soil quality and reduces nutrient runoff.

By creating biochar from biomass, carbon is sequestered in a more stable form, staying put for thousands of years in soils. Applying biochar to agricultural land can also reduce the plot’s methane and nitrous oxide emissions, two dangerous greenhouse gasses.

A sustainable bioeconomy would need to strike a balance between extracting sufficient resources from forests and making sure forests remain viable ecosystems. Therefore, in order for wooden construction or biochar implementation to be successful, there would need to be guardrails on the bioeconomy.

building’s life cycle, wood-recovery is the most sustainable option, according to Dr. Churkina’s research. Wood from a demolished building can be directly reused for other purposes such as insulation or interior finising.

Alternatively, wood waste could be converted to biochar, the result of thermal breakdown of biomass. Its primary

Dr. Brian Palik (the Science Leader for Applied Forest Ecology at the USDA Forest Service Northern Research Station) researches ecological silviculture. He definesan ecological approach as “managing a forest as an ecosystem as opposed to a collection of trees that are important to timber purposes.” He also indicates that as opposed to timber-focused management, an ecological approach to forestry could maintain healthy forests and a robust bioeconomy.

One example of ecological silviculture is the retention of biological legacy, a technique that is relatively well-accepted across the U.S.. Organisms and structures—such as giant sequoias, coastal redwoods and

down logs—left behind after a natural disturbance are biological legacies. Biological legacies provide habitat for many wildlife, promote structural diversity and supply a space for seed germination. Dr. Palik explains that in an ecological approach, foresters “will do a harvest to regenerate a forest… but it looks a lot closer to that natural model after a natural disturbance than typical timber silviculture”.

“[Another] example is to let forests develop for longer periods of time before there is a harvest,” explained Dr. Palik. “When [trees] stop growing at their optimal rate…that’s typically what defineswhen the trees are harvested. In the ecological approach, it’s based on ecological cues when you would harvest and that tends to be longer than timber-focused silviculture”.

This second technique is more controversial according to Dr. Palik “as it starts to affect the economic return of a forestry approach.”

Risks of over-harvesting forests include poor soil health and impacted biodiversity.

“If you are trying to optimize… fast growth of trees, there are definitemeasurable negative impacts to habitat, diversity, and sustainability,” Dr. Palik asserts. Aiming for accelerated growth of forests for economic purposes resembles an agricultural system rather than cultivating our forests to be economically viable and healthy.

Ecological silviculture is just one management strategy for

the tradeoffs between a profitable bioeconomy and healthy forests. Dr. Tobias Heimann, lead researcher on the project ‘BioSDG’ at the Kiel Institute for the World Economy, evaluates the possible pathways to a bioeconomy and examines trade offs between ecosystems, food security, land-use, and the Sustainable Development Goals.

“We couple global CG models with economic models, with a biophysical model from our partners in Munich, and with a forest sector market model from our partners in Hamburg. We can model trade offs and global effects in land use change, but also in carbon emissions when climate policy or bioeconomy policies are implemented in certain regions,” explained Dr. Heimann.

Although the bioeconomy taps into a circular system, it can easily be a system with no net environmental benefit.Destruction of forest ecosystems, land grabbing and displacement are just some of the risks that a mismanaged bioeconomy system poses.

Already, the biomass production industry competes for land space, endangering local communities. In the Southeast of the United States, wood pellet mills — which are 50% more likely to be near POC communities — emit toxic air pollutants, and unsustainable logging weakens these regions’ resilience against storms.

The IPCC suggests that largescale biomass production for bioenergy purposes could be grown on degraded lands, but this strategy depends on if af-

forestation is done with natural or plantation forests. Cooperative production systems could be developed where natural forests are grown with some crops dedicated for biomass production. However, the success of these systems are hard to quantify.

“There is no model that is able to simultaneously include all the different aspects that are affected by the bio economy,” said Dr. Heimann. “For example, with biofuel policies, which are very common, many different SDGs are affected simultaneously, making it difficlt to evaluate all.”

According to Lenier, “Ideally, in a circular economy, we’d be building principles so that any extraction has to be fair trade. The benefitof having a system in which resources are circling is we naturally have less of a need to cut down more forests.”

The bioeconomy in forestry represents a new way of interacting with goods and services that could maintain balance between human needs and the integrity of global ecosystems. If properly bounded by sustainable forestry practices, forest products could meet the world’s growing construction and carbon capture needs in an environmentally, socially-conscious way.

by COLE HADDOCK

by COLE HADDOCK

On August 19th, 2023, Jennifer Gerlach died behind a dumpster in Berkeley, CA. She died across the street from a Tesla warehouse, an urban farm, and a tea shop. She died after her condition was noted by several outreach workers. She died from maggot infested wounds and diarrhea, a ten minutes drive away from a hospital. She died on 8th and Harrison in the Gilman District, one of the most contested blocks in Berkeley, CA. For years, the City of Berkeley has been trying to manage the unhoused

community there, with outreach teams, sweeps, and law enforcement. As many surrounding encampments have been swept and shut down, the number of people living in the Gilman District has remained high. It is crowded and chaotic. On August 19th, 2023, in one of the richest areas of the country, Jennifer Gerlach died behind a dumpster. How was that allowed to happen?

CHAPTER 1- 8TH AND HARRISON

Ms. Alice Barbee walked out in a dress and blazer, put a rug down, and sat on the curb to wait for her interview. She took the microphone like she knew what she was doing and introduced herself with the type of contagious, passionate grin that would make you either fall in love or vote for her. It makes sense that she’s running for mayor.

Ms. Barbee came to 8th St. fleeingdomestic abuse. She had been in Berkeley for ten years, isolated from friends by

a possessive partner and 500 miles away from her family in LA. But, “the morning that I thought for sure that [my partner] was going to kill me and my dog, I left and never looked back.” She’s been living in Gilman since March 2022, and she’s a landmark on 8th St., with a well-built tent and a koi fishflagthat announces when she’s home. Her dog’s still with her, “sweet if she loves you, loud if she doesn’t.” She’s always wearing a good outfit. If you ask her about the food, she might gloat a bit, saying, “It’s amazing the food that actually comes out of this place. Mackey makes really, really great salmon.” Ms. Barbee describes, “a great support group out here. We build eachother up…Even if it isn’t exactly home, it still gives you a sense of it.”

While she spoke, dozens of cars sped by, going to work and staring. The public anonymity of 8th St. bothers Ms. Barbee. A speeding car honked for someone to get out of the way, and she sighed. In an interview with Mark Morrisette, owner of the Berkeley Rep building across the street, he couldn’t name a single person he’d worked next to for years.

“You know, the stigma that comes with homelessness is ridiculous. We might as well all be pit bulls. And nobody likes pit bulls. Like my dog is a pitbull, right? She’s a big old bark dog. And people will cross the street to get away from the side of the street where I’m walking down. And they just don’t realize that she’s the sweetest. She is, you know? If anybody took the time to realize or take the time to notice or even talk to

any one of anybody out here, they’d be like, Wow, right?”

The firstthing most people notice about 8th & Harrison is how much stuff there is. There are tents, shopping carts, beds, clothes, bikes, and RVS. There are boxes and dogs and trash and collected recycling. It’s people’s lives, all laid out on the sidewalk.

The city receives a lot of complaints about the appearance of 8th and Harrison. Business owners say the encampment is a deterrent to their customers. Nearby residents say it’s unsafe, and the stewards of the creek at the end of the road complain of environmental degradation.

In response, the City of Berkeley tried to negotiate with the camp residents. They agreed to an unofficialset of rules for the residents, including keeping their tents to one side of the streets and out of the creek. In return, the city put it in a dumpster for the dozens of people living there to throw away their trash.

But fundamentally, when people don’t have anywhere to go, neither does their stuff. The dumpster didn’t solve that problem.

There’s conflictingreports on how much notice the residents of 8th St were given, but in October, the Environmental Management Division, the Public Works Division, and the Homeless Outreach Team decided that the conditions had deteriorated unacceptably at 8th and Harrison. Citing rodent harborage conditions, they declared

the whole neighborhood an environmental health hazard.

The City of Berkeley issued a nuisance abatement to the residents of the Gilman District. If they didn’t clean up their own belongings, the City would.

For the health and safety of these residents and the entire Berkeley community, the Homeless Response Team respectfully recommends that you order immediate abatement of the public nuisance conditions in this area (specifically, Harrison St from Tenth St to Sixth St, and Eighth St from the creek to Gilman St), including destruction of any property constituting such a nuisance if the nuisance cannot be abated otherwise, pursuant to BMC 11.36.050 and 11.40.130 through 11.40.120.

“So a sweep is one of the most miserable things I’ve ever seen in my entire life. The city will arrive where people are sleeping, usually around seven in the morning. And they will wake them up by washing their high beams or shaking the tents. Usually, the first people that arrive are the police and homeless outreach team. So the homeless outreach team will go around and talk to people and say, you know, do you want to go inside today, but they don’t actually have any resources to offer. Public works will be pressuring people to move, and throwing things away. Sometimes it’s trash, sometimes it’s people’s belongings, they rarely stop to ask. And then by 8:30 , most people are gone. I mean, they’ve taken their belongings with them across the street, or they’ve had them thrown in a dump truck.”

Interview with Director Ian James,

At 6:40 am, on October 4, 2022, residents of 8th St & Harrison were woken to police cars and flashinglights. Over the next twelve hours, police officers and outreach cleaned the streets. Medicine, food, toiletries, recycling, and bedding were thrown away. They bargained with residents to leave, and threatened arrest. They offered small replacement tents and hygiene items.

It was all documented by Yesica Prado, a resident of 8th and Harrison, advocate, and journalist. Her documentation, and the testimonies of advocates and residents, describe a profoundly traumatizing event. In police records, they describe calling the ambulance for a heart-related medical emergency.

Ms. Barbee had just been diagnosed by the mobile medical unit with congestive heart failure. The day of the sweep she described, “they literally took everything that everybody had. All of it. I mean like anything that there was– any heirlooms, all of the medication that I’ve been taking. They said if you want to keep anything, get it across the street. So we got it across the street. And as soon as all that was done, they came back and they took all that stuff too. I literally was almost gonna have a heart attack. They had to have the paramedics come out and check me out to make sure I wasn’t going to just die.”

Prado’s report documents mental health crises not disclosed in the public police records. At 10:11 am, “Shawna

Garcia is asking for help. She feels threatened, and fears being pushed back to Second Street, where the city was allowing people to live in tents and makeshift structures — but that was also where her abusive ex-boyfriend was living…. Shawman is clearly in distress. After city employees take her tent, she scrounges in the roadway trying to save whatever food she can gather. “

12:01 pm: Rufus, who was hit by a car and cannot move easily, was left on the sidewalk without proper clothing for hours. His belongings were thrown away.

1:11 pm: Jeff asks for reasonable time to move his stuff out of the area. His wife, Eren, is breaking down in tears inside their tent with her dog. She is unresponsive and shut down from the stress, her mind scattered on what to do next. ‘My wife is losing it,’ Jeff says. ‘They are just breaking her down more.’”

Months later, all of the residents remember the sweep. Chloe Madison, an RV resident, remembered that, “They had the bulldozer and a bunch of garbage trucks and they were just tearing shit apart apart. It was nightmarish. Honestly, it was quite just disgusting to watch other humans tear down the living quarters of other humans. I think we all got through it. Everybody’s still alive. But it’s really fucked up shit.”

By the next week, conditions had pretty much returned to the way they were, according to a complaint email from a

neighbor. This time, the city claimed they could not do anything about it. As Beth Gerstein from the City of Berkeley explained, “We need housing solutions for the 20 plus individuals that have been sleeping on the street down there which is not something we currently have. We need addiction treatment resources and supportive housing for seriously mentally ill people. We don’t have those either. This should be more readily available within the county and state, but it is not, and Berkeley, like all cities, is the firstline of defense and we just aren’t able to keep up.” The city admitted that it wouldn’t do anything serious again unless the conditions deteriorated to warrant another sweep.

Today, 8th and Harrison is more crowded than ever. As unhoused people get pushed out of almost every other place in Berkeley, this is the only place to go. There’s almost double the tents as there were a few months ago. It’s crowded, and chaotic. The City apologized for their treatment of unhoused people, and promised reform.

On August 19th, 2023, resident Jennifer Gerlach died behind the dumpster on 8th & Harrison.

How did we get here?

CHAPTER 3 - DAN THE BLACKSMITH

There’s a whirlpool in Dan’s yard. The whirlpool is fast and strong, and pulls all of the flood water underneath tenth street and out of his backyard. Dan built this concrete diverter with his friend when he first

moved into the house thirty years ago. See, he can’t allow it to flood. His house is only ten feet away from the creek– if it got out of control, his entire house could be gone.

On 10th St in the Gilman District, Dan’s also constantly fightingto defend his property from unhoused people that live nearby. He gestures at the fence that lines his property. “One day, I came home, and on my front steps, two people were fucking. I don’t know if it was consensual, I don’t know,” He trails off. “But I yelled them off, and then I put this fence up. I had to keep that out.” The fence isn’t that tall, or officiallooking. It would be easy to jump. 8th and Harrison is surrounded by barbed wire and cameras. The businesses around the encampment want to stay safe. The fence in Dan’s yard does its job—this land is not public. It is fenced; it is his private property. Stay off.

From the inside of his living room, Dan looks out at Codornices Creek through an iron barred window. He shows pictures of the squirrel that he has been feeding, as well as some birds that he’s watched hunting on his property. He points out the willow trees that he’s trimmed every year. They’re native willow trees, grown from sticks into a massive canopy, and he’s very proud of them. He talks about the rainbow trout that swim up the creek.

As much as he documents the beauty in his yard, he also carefully documents how unhoused people affect it. Showing a massive fileof photos he had

taken of the encampment that had taken up residence across the street , he says, “Look at how much trash is there. It’s a dumpster; it’s so dirty.”

Dan Dole has lived in the East Bay for a long time, and this is not how it used to be. He says the unhoused population has increased significantly,the city doesn’t care, and the neighborhood has completely changed.

Dan doesn’t think they’re necessarily terrible people, but they need serious help. He says, “They know where I live. I have to protect myself.” He shows me pictures of a man that had accosted him once outside the front of his house as an example of how dangerous it’s been sometimes.

His neighbors have similar sentiments- the owner of the plumbing company next door said that the unhoused population is hurting his business. He’s been in Berkeley for decades, and now his customers refuse to come down here. He got robbed not that long ago. He says, “Those people need serious help. They’re dirty, and the university and the city won’t do anything about it.”

The Gilman District is supposed to be a light industrial neighborhood, known historically for being worker’s’ and artist’s’ housing. But a 1-bed, 1-bath apartment in the Gilman District rents out for $1,725. One of the newer neighbors on Harrison St is a Tesla service center. It is hard enough not to be pushed out of the neighborhood, without unhoused people making property values lower, and scaring customers away.

Dole says the City of Berkeley doesn’t care about small business owners– if they did, they would protect the people and businesses down here.

Susan Schwartz sympathizes with businesses. “People don’t want to come to their premises- It’s creepy.” From her view, nobody wants to visit Codornices Creek, either. She’s spent the last twenty years trying to maintain this creek, and has watched as unhoused people have camped, started fires,and trampled plants on the creek. “I mean, we’ve had our work destroyed repeatedly. It’s heartbreaking. We didn’t get paid to do any of this. We’re trying to make something beautiful.”

In her own words, Susan Schwartz has been a writer, a mother, a sleuth, an environmental janitor, a failure, a leader, and a needle pusher. If you ask her directly, though, she says, “My name is Susan Schwartz. I am an old lady.”

Schwartz has been co-running the neighborhood group Friends of Five Creeks for twenty-fiveyears. The collective of citizens, students, and nonprofitsworks to “control erosion, remove trash and harmful invasives, and plant natives, creating varied and welcoming urban oases for people and animals” (2021 Annual Report). One of their biggest projects has been at Codornices Creek, which runs right next to the encampment on 8th St.

After being infilled,trenched, and polluted by West Berkeley’s early industrial land use, Codornices Creek was put in a concrete pipe. When a creek goes underground, the ecosystems and species they

support cease to exist. In 1995, activists pushed to bring Codornices Creek back to the surface.

In two major efforts, the first in 1994 and the second in 2003, Codornices Creek was unearthed. A trench was dug, willow trees were planted, and today it flowsfreely between Sixth and Ninth Streets in the Gilman District.

After the unearthing, however, Codornices Creek quickly fell into major disrepair. As Schwartz described it, “[Cornodices Creek] went to hell. And was completely overgrown with an invasive that essentially just blanketed everything.“ In 2018, volunteers discovered about “half million dollars in escrow for maintenance of restorations [at Codornices Creek], and that escrow was going to expire in a couple of years.” The discovery of these funds refueled the efforts of Friends of Five Creeks, who removed trash, cleared invasives, and taught a lot more people to love Codornices Creek.

Today, Codornices Creek stands as a testament to urban greenspaces, with informative signs, paths, and birds everywhere. Rufus, a resident of 8th St., loves the creek. It’s quiet, beautiful, and green. Rufus moves slowly, going ten feet a minute from old injuries in an old wheelchair. The quietest part of the creek, across the street from Dan Dole’s house, is a couple of blocks and maybe a couple hours walk from his tent. It’s next to the baseball field,and on good days, he can eat his doughnuts and breathe the air while sitting next to the

creek.

He’s not the only unhoused person that loves Codornices Creek. Across the Bay, unhoused people have less access to water than meets the international WASH standards for refugees. Without access to water, or restrooms, people often end up near creeks. When people get swept off the streets and out of the public eye, they often end up in natural spaces. In places like Codornices Creek, there is water, seclusion, and less police harassment.

Susan Schwartz, Dan Dole, and Rufus all love the same creek. But for Schwartz and Dole, their fightfor survival isn’t about findingfood, struggling to maintain sanitation, or desperately needing clean and quiet time. It is about property ownership, protecting their neighborhood, and long-term accountability. When asked if it was possible for the 8th St. community to reconcile under shared goals and understandings, Schwartz said, explicitly, “If we take it that the unhoused people are part of the community, no.”

Schwartz is well-known for her emails. Every officialinterviewed for this article had been on the receiving end of one. She is an educated and connected activist. She sends emails documenting people stomping over native vegetation, pulling up flags,setting fires,and releasing sewage into the creek. Her organization doesn’t host as many events at the creek as they used to for safety fears.

She expressed sympathy for “society’s failures of these people” and their “impossible situations”,” but using language that is common amongst housed people in the community., sShe describes the unhoused (and RV) community as “addicts “ and”deeply insane people” overwhelming the neighborhood. To her, it is obvious that “as long as there is Berkeley’s outdoor insane asylum on Eighth St.,” Codornices Creek will be continually destroyed.

Across the Bay Area, this is common. There is public support for sympathetic policies, more housing, and a network of nonprofitsand housed people trying to assist unhoused people. But there is also a growing sense of frustration with a perceived lack of community responsibility on the part of unhoused people.

A map of San Francisco went viral after documenting reported human feces sites across the city. Another NBC investigative map went viral after documenting sightings of feces and needles in downtown San Francisco. Both maps were trying to alert pedestrians of where not to walk, and also bring light to the issue of homelessness. Or at least, the dirtiness of unhoused people.

When discussion of homelessness focuses on “filthiness,” and the degradation of the natural environment, a sense of injustice all over the Bay Area begins to build. Someone took out a full page ad claiming that San Francisco had let the “tax-paying” citizens down by “catering to the lowest com-

mon denominator.”

Nationally, East Bay and San Francisco have made headlines about being filthy,and overrun by homelessness. Notably, in 2019, President Donald Trump tried to get the EPA to cite the city of San Francisco, saying, “They’re in serious violation. This is environmental, there are needles and feces flowing into the ocean…. and they have to clean it up. We can’t have our cities going to hell…We can’t lose our great cities like this.”

Mayor Breed of San Francisco expressed frustration with unhoused residents, saying, “I work hard to make sure [housing and homelessness] programs are funded for the purposes of trying to get these individuals help, and what I am asking you to do is work with your clients and ask them to at least have respect for the community — at least, clean up after themselves and show respect to one another and people in the neighborhood.”

Keith Lichten, from the San Francisco Water Quality Control Board said as an environmental regulator, “Of course, we’re concerned about water quality, specificallyabout discharges of human waste of sewage, and trash associated with homelessness. But we also have an eye on longer term solutions, jobs, housing, supportive services. And recognizing the limits of resources that are available.” The ideal of long-term and underfunded solutions doesn’t solve the onthe-ground realities of places like the Gilman District.

On August 8, 2022, Susan

Schwartz sent an email to the city of Berkeley, also CC’ing the State Waterboard. In it, she describes the “death of Codornices Creek.” She cited sewage discharges into the creek and describes “Camps overflowing with trash and belongings now occupy the entire sidewalk and spill into the street, with conditions worse than any I recall from the slums of Africa.” Her finalcomplaint was that, “Much of the creek below Eighth Street is more attractive than everbefore…[but] the public cannot enjoy or feel safe in the creekside trails (now tent occupied).”

The State Waterboard has the power to review the City of Berkeley’s natural water quality, and if it deems that the City has violated sewage regulations, can enforce the codes with stricter regulation and fines.After this email, the Waterboard followed-up with their concerns and scheduled meetings with the City of Berkeley to voice their concerns for the creek and conduct a walk-by test. Between the date that Susan Schwartz sent her provocative email and the Waterboard came to visit, the City of Berkeley held the October encampment sweep referenced above.

This email, and the dozens of other continuous complaints about the filthof 8th & Harrison, hits a nerve within the City of Berkeley. Peter Radu, Assistant to the City Manager for the City of Berkeley and often the one deciding how the city will manage its unsheltered population, expressed his frustrations.

“I think I mean, yes, I think I

would be lying if I told you that the city wasn’t feeling frustrated about the situation down there,” He said. “Mostly because we’ve tried to do everything possible to just maintain cleaner and better conditions.” He acknowledges that the people at 8th & Harrison need housing, but refers the responsibility of that to Alameda County.

It’s up to Alameda County to house people long-term, not the City of Berkeley. All they can provide are small numbers of temporary shelter beds and motel room vouchers, which many people refuse because they’re often temporary, crowded, and controlling. Without the ability to solve the problem completely, the City of Berkeley “really did a lot to try to maintain as safe conditions as possible for that encampment over the course of several months.” They provided a dumpster, showers, and a port-apotty. Yesica Prado would counter this, say that it took months for the city to deliver on those promises, and that they were insufficient.

But, Radu says, the residents just didn’t maintain their side of the deal. He says that, “The conditions were so bad that the environmental health inspectors were very concerned about what they saw–the unmitigated human and animal waste, the rodent harbourage conditions, the loose and scattered syringes, what appeared to be raw sewage in buckets, like it was really, really bad conditions. So bad that they had to be declared an imminent health hazard.”

Radu talked about the importance of keeping public space open to the public, “to the university village students going to work and class”’ and the nearby business

owners. When asked about the traumatic nature of the sweeps, he didn’t respond, saying, “I’m going to counter your question with a question. At what point, acknowledging that encampments are the new normal for the foreseeable future, at what point do we have to enforce some semblance of a social norm?”

Cars don’t stop coming on Harrison St. Over and over, cars screeched around RJ’s wheelchair. One man even slowed to yell, “HEY! You could get hit.” RJ shook his head, and kept moving. The reason he was in this wheelchair, the reason he was pulling himself down the middle of the street, was because he had already been hit the year before.

Rufus was hit near the 580 in South Berkeley, which was one of the biggest encampments in Berkeley before it got swept out. Many of the unhoused people living in the Gilman District have already been kicked out of a lot of places- Adeline St, Albany Bulb, the Berkeley Marina, and the Aquatic Park. Amber Whitson, a well-known inhabitant of Albany Bulb, a previous dumpsite where many unhoused people set up camp, said, “They’re just running people around. It’s the leaf blower effect. Blow your problems onto somebody else’s sidewalk. I don’t think they understand physics too well. Everybody’s got to be somewhere.”

Rufus is in a wheelchair and findsit difficultto get off the ground and out of the tent. He

pulls himself along by his toes, going astronomically slowly towards the McDonald’s or the donut shop a few blocks away. He is missing an eye and a figer, and looks a lot older than he is. Asking Okeya Vance why he wasn’t on the top of the list to get housed, she said he needed a nurse and assistance, and there aren’t the resources for that. He also wasn’t that compliant with them. So instead of anything, he would stay on the street.

Rufus lives right next to a dirt street planter, right next to the rat holes documented in the city’s public health report. He glared at them, and said that the rats were evil. He said the pavement was hard on his back, and every time we speak, he has a new plan to get an RV or an apartment.

Lady J and Alejandro’s problem is that people think they’re mean. I asked them what brought them together, and they both said, “we don’t take shit from no one.” They’d both been to prison. They’d done hard time in hard places, and they learned the kind of walls you put up to survive in those sorts of worlds.

Lady J had grown up institutionalized. “No. I don’t have family to help support me. I have to do everything on my own. And that’s hard. Especially being a female. I grew up in and out of foster care and group homes since I was three. I started running away from home at the age of I think 10. I was bounced from foster home to foster home from group home to foster home from foster home to group home. And

finally,when I was 16, they’re like, ‘we’re locking you up until you’re 18.’” She said she lost everything in prison. Lady J doesn’t trust anyone, anymore, except her dogs.

“I’m not like most girls. I’m very different. I look like a girl but I can handle my own. I’m not really afraid of anything. Except the dark. Don’t tell nobody. (Everyone busted up laughing).” Lady J recycles for a living. It’s hard work- she collects pounds and pounds of metal to drag to the recycling center everyday. She’s on the waiting list for housing, but won’t go into temporary shelter for fear of losing her dogs.

Walking up to Alejandro, Ms. Barbee was cheering him on as he spun rings. He got shy in front of us though, and asked if we just wanted to talk instead. He said growing up in Richmond, he never used to get shy, but “Just going back and forth to the penitentiary. It gave me to the point where I felt like I can’t be in public. Like, you know, I got post traumatic. I can’t be in big stores, you know. It’s anxiety attacks now.”

He was deeply skeptical of law enforcement, and talked about getting dragged to jail and about starving while incarcerated. He’d been harassed by police officers,and rejected job offers. He talked about a judge asking him where he was gonna end up. “Oh, well, are you going to the shelter? Are you going back to the penitentiary? It’s clear you’re trying to just make me a statistic.”

Alejandro talked about not

being able to go into a Target. “I used to like that type of environment. I mean, I played football, for crying out loud. I played baseball and you know, you smack a homerun at the end, your whole team waiting for you right there. I can’t do that no more. I can’t be around people like that no more. They ruined me a little. That was why people like to be around me, because I was a people’s person. I’m not a people person anymore. And that’s, that’s making me bitter.”

Asking Lady J and Alejandro why they hadn’t gotten housed yet, they both said it was because they weren’t nice enough for the workers. Lady J said, “I just don’t like them putting their noses up to us because we were them. You know what I mean? They can lose what they have at any moment– they could hit somebody in a crosswalk and go to prison and lose everything. For vehicular homicide. You know what I mean? And it’s not their fault. But still, they still got their noses turned up to us. I don’t like it. I don’t like stuck up people.”

There’s dozens of stories on Gilman St. There’s Stan, who wears bright pink glasses and lost his arm in a corn picker in rural Minnesota. There’s Felix, who accompanied every answer with an improv guitar solo. There’s Alice Barbee, Chloe Madison, Keith, Sissy, and Hassan. There are formerly incarcerated people, Black and brown and white people, trans people, mothers, fathers, and dogs. There are musicians, artists, and chefs. There is every type of person that can fall through the cracks.

Between 2011 and 2017, the Bay Area created 531,400 new jobs but approved only 123,801 new housing units, a ratio of 4.3 jobs for every unit of housing. In 1955, there were 558,239 severely mentally ill patients in the nation’s public psychiatric hospitals. In 1994, this number had been reduced to 71,619. Gavin Newsom is emptying the prisons. Hard and addictive drugs are readily available at 8th & Harrison.

There are endless ways to end up on the streets. There are endless ways to end up broke, struggling, and tired. There aren’t endless things needed to get off the streets, though. People need mental health care. People need housing. People need patience, and follow-ups. People need time, effort, and care, and there just aren’t enough resources available.

Yesica Prado is an East Bay investigative reporter whose work has been referenced above. Prado explained that as a graduate student at the U.C . Berkeley School of Journalism, “I basically ended up having to give up my apartment. I couldn’t pay rent anymore. And then that’s how I ended up getting the vehicle. I had no idea what to expect. I just think it was like, I’m just gonna do this, because I’m gonna try to get to school.”

At sweeps, city council meetings, and in solving everyday conflicts,Prado has been appointed as the advocate for 8th & Harrison. She’s spent years showing up, and telling real stories about the people at 8th & Harrison. And nothing much

has changed.

“You pour your heart out to them. And you tell them like, this is how it really is. And at the end of the day, they’re not just gonna do whatever they were gonna do anyways, you know? Yeah, so it almost feels like yeah, I don’t know. I don’t know.”

by ABBY WILBER

by ABBY WILBER

Maybe offworld colonization is the only way for humanity to outrun the damage of anthropogenic climate change, or maybe space-based solar power will be a lifeline.

A climate-healthy future may yet be prolonged, owing to Earth’s firstsource of energy: one bestowed rather than demanded, one inherent with photosynthesis and the routine of each new day from an Earthen perspective. Solar radiation as renewable energy is not a revelation, but what if it came straight from the source—making the sun an ever-resonating provider of the planet?

Sometimes, dreaming and pondering faraway worlds yields innovation to confound humanity’s relationship with the cosmos. Space-based solar has become an increasingly non-fictionpiece of Sci-Fi since 1968, when an aerospace engineer took it from a fantasy to a plausibility. Space-

based solar power is energy from the sun collected by a satellite in Earth’s orbit.

Though set apart from all existing energy-generating methods by its distance from Earth, this method relies on the already well-established use of photovoltaic panels that can convert sunlight into energy—in essence, the same cells that are already scattered across many rooftops here on Earth.

With terrestrial solar panels, we wait for the morning to bask in rays as the polarized charges of an electric fieldmade by photovoltaic panels remove electrons from atoms and turn them to usable energy. If solar energy could be captured every hour, the sun would become a ceaseless, omnipresent power bank, unencumbered by nightfall. Satellite solar panels could collect light in its most powerful form of blue waves, which

dilute and scatter when they hit Earth’s atmosphere.

A UC Berkeley professor in environmental policy and nuclear engineering, Daniel “Dan” Kammen is the James and Katherine Lao Distinguished Professor of Sustainability, former science envoy in the Obama and Biden administration and former Senior Advisor for energy and innovation at the U.S. agency for International development.

Initially inspired by offworld stories and technologies, the self-proclaimed Star Trek quoter Dr. Kammen worked in a team of three just last year to devise a design and plan for the firstsatellite solar power station. This proposal was elaborated into a budget report with the help of a few Berkeley undergraduates, and later approved by scientists at NASA’s Glenn Laboratory. The estimated cost of the assembly and launch of a trial satellite the size of the one designed by Kammen and his original team would be around $25 million. By comparison, NASA’s current mission, Artemis, is projected to cost $13.1 billion total and over $4 billion per launch.

Kammen describes the vision of solar-harvesting in space reflectedin his work: a large network of photovoltaic cells, protected by a polymer film.Witha plastic protective layer, the cells would be able to prevent potential destruction from small meteorites and other threats in the extreme environmental factors of space.

For solar energy to be transmitted down to Earth, the conversion of electrical energy into microwaves would result from the use of a klystron—a device that manipulates electron speed and thus wavelength. A large receiver on Earth, a “stationary satellite” such as a satellite dish, would capture this microwave energy, already in a ready-touse manner similar to any terrestrially generated

solar energy.

With the extraterestrialization of energy harvesting, energy’s mobility suddenly becomes a serious consideration: Solar energy is made a traveler through the cosmos. Relative to the distance between the sun and Earth, its current capture and dissemination seem local.

In early designs of solar space satellites, lasers were proposed as the mode of transporting solar energy down to Earth. However, as these plans were brought out of the realm of science fiction and into the very real sphere of contemporary politics, it became clear that, though less high energy, unobtrusive microwave beams would be much less concerning to the public than lasers from space.

If the launch of a solar satellite is funded and successfully deployed, the technology could have the potential to singlehandedly power a new global energy grid. With 24/7 energy capture, there would no longer be a need for energy storage. Typical solar energy harvesting methods must account for the fluctuationsof the sun’s availability on Earth, requiring the use of batteries that can store the energy to be used when the sun isn’t momentarily available.

All solar energy generated is stored in centralized batteries that connect back to power grids; the “grid model” of energy has in this way allowed solar energy to become much more reliable and widely used. However, these batteries themselves play a part in counteracting the alternative to natural resource use and lessened emissions achieved by solar energy.

Lithium ion batteries in particular, known for their fast charging time and longevity, are rising in popularity and becoming a global market for the storage of many forms of renewable energy. The harvesting of lithium entails either open pit

“If solar energy could be captured every hour, the sun would become a ceaseless, omnipresent power bank, unencumbered by nightfall.”

mining or brine extraction, both of which disrupt their ecosystems by producing toxic chemicals, causing health risk and pollution. (source)

Receiving energy from a space solar satellite in large dishes or radio telescopes would allow large areas to access solar energy in real time both day and night— without the need for costly and environmentally damaging batteries. Making this method even more efficientis the fact that the amount of solar energy available to be captured and put to use in space is 13,172 watts per square meter.

On Earth, in the prime location for solar energy harvesting (which is in the Atacama Desert of Chile), 850 to 900 watts per square meter is the most you can hope for, even on a day of maximum sun exposure.

Engineers at Caltech, the Japanese Space Agency (JAXA) and UC Berkeley are all contributing to the development of space-based solar in different ways, with their collaboration possessing the potential for synergy and coherence in one technological breakthrough to make space-based solar possible on a large scale.

At Caltech, the Space Solar Power Project is spearheading the design of every aspect necessary to make space-based solar a reality, in collaboration with NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL). They are advancing photovoltaic technology beyond the typical model of rooftop solar by investigating new materials, taking the conditions of space for the design challenge that they pose.

By using novel photonic structures, materials can better manipulate and utilize the specificwavelengths of light emitted by the sun. Caltech’s Space Solar lab has also worked intensively on developing wireless power transfer systems, working to answer the questions of how energy can effectively be transferred from a space satellite, received, and redistributed as energy usable in everyday life.

Caltech, JAXA, and Kammen’s lab at Berkeley each take a holistic approach to developing space-based solar systems, but each has their particular area of strength. Caltech’s progress towards mobilizing space-harvested solar energy, JAXA’s work involv-

ing launch logistics and Berkeley’s innovative solar panel design, optimized for launch and self-assembly, each fita piece in the puzzle. According to Dr. Kammen, their harmony sets the precedent of a possible collaborative effort between the three.

Keeping space-based satellites from roaming the sky is in large part the perceived costliness of the construction and deployment of the technology. However, Dr. Kammen’s insight informs that the price of solar energy-harvesting mechanisms have dropped by 90% in the past decade. He notes that with regard to the costliness of renewable energy, the greatest upheaval in cost lies within the batteries that store harvested energy.

With the hypothesized storage methods of spacebased solar power, Dr. Kamen states that energy storage by way of expensive lithium ion batteries and other typical storage methods would become unnecessary with the direct channeling of solar energy from space to where it is needed. Kammen mentions that in addition to dropping prices within the solar industry, private space launch prices are decreasing due to the industry’s global growth.

Space-based solar power was dreamt up decades ago, and as so many works of fictiondo, it aged well in order to meet the present state of the world. In conjecture with the increasing affordability and technological advance of its components. Dr. Kammen sums up the exciting and miraculous plausibility of the technology: “If solar hadn’t become cheap, and if launch costs hadn’t gone down, we wouldn’t be thinking about it. But both have happened.” And so we can look to the sky as we consider the next steps in transitioning to renewable energy.

In March 2022, California Governor Gavin Newsom’s Wildfire and Forest Resilience Task Force issued a Strategic Plan for Expanding the Use of Beneficial Fire. The plan set a target of expanding the use of “beneficial fire,” which includes prescribed fire and cultural burning, to 400,000 acres annually by 2025. The shift towards using prescribed fire in forest management was a major change of tune

for California, as prior to the 1960s, state agencies believed that all wildland fires should be extinguished as quickly as possible.

This fire suppression approach has dramatically altered Califnoria’s ecosystems by removing an important abiotic factor in fire. Scientists have shown that California’s native plants and animals benefit from periodic fires and that the fire suppression policy has created unnaturally high abundances of biomass, resulting in conditions that are actually more prone to severe wildfires. Research has shown that prescribed fires help mitigate these issues by reducing fuel load and creating conditions that fire dependent species need to reproduce.

Scientists, gov -

ernment officials, and CAL Fire have all acknowledged the need and importance of prescribed fires, along with the imperative to rapidly scale up California’s prescribed burning efforts. However, despite the consensus, the historical rejection of fire in any form has created a number of legislative hurdles and an infrastructural deficit that make it difficult to perform prescribed burning.

One barrier to increasing the amount of prescribed burns in California is the Clean Air Act. The Clean Air Act allows the Environmental Protection Agency to set legal limits for how much pollution districts are allowed to emit and includes a host of emitters such as agriculture, automobiles,

electric utilities, and pre-

scribed fire.

However, while prescribed fire must adhere to the pollution limits, wildfires are not held to the same standard. Lenya Quinn-Davidson, fire advisor for the University of California Cooperative Extension, explains how the differing approaches to air pollution creates a bias towards destructive wildfires, rather than controlled and prescribed burns.

“ Prescribed Fires create smoke with the intention of preventing more distructive levels later on. ”

“

Scientists have shown that California’s native plants and animals benefit from periodic fires.”Designed by Olivia Rounsaville

“The inherent problem with that is that we’re basically selecting for the worst kinds of fires, because we are saying those ones are off the hook and they can burn as much as they want. Whatever happens, happens,” she said. “But if we are trying to do good work we are going to account and regulate it heavily and actually prevent it from even happening in the first place.”

Fire scientist Molly Hunter supports this point of view, explaining that prescribed fires create smoke with the fundamental intention of preventing even more destructive levels of potential wildfire smoke later on.

In addition to political challenges, finding enough skilled workers to perform prescribed fires has given California great difficulty. The shortage stems from the sharing of skilled personnel that fight wildfires and perform prescribed burns, the temporary nature of these positions, and a century-long pause during which prescribed fire knowledge was not actively utilized.

Quinn-Davidson states that California is undergoing a “workforce crisis” because the state’s fire suppression policy has disrupted the “cultural continuity” for prescribed burning in indigenous

“there’s so much fire work to be done and there just aren’t that many people who have those skills.”

Moreover, according to Hunter, prescribed burning positions being temporary contradicts the fact that prescribed burns can happen year round in California. She believes that it’s important to have a “workforce available to do prescribed burning when they do have those windows open up.” This approach maximizes the opportunities to take advantage of favorable weather conditions for prescribed burning.

There are also liability issues that have resulted in unequal protections for burn bosses burning on public lands through state and government agencies compared to those performing burns on private lands. In California, current policies place the sole liability of the prescribed

lands is absorbed by the government.

The differences in liability exemplifies how federal and state employees have major protections compared to private individuals or indigenous peoples performing prescribed burns.

For example, Quinn-Davidson looks to a 2022 federal prescribed fire in New Mexico that got out of control: “The person in charge of that burn was a federal burn boss who worked for the forest service… he is protected in his position because he works for the federal agency and he was operating within the scope of duty of his job.”

“If I were burning on private land and had that kind of situation happen. I would be personally liable,” said Quinn-Davidson.

In an effort to address this gap, recent steps like California’s Senate Bill 332, passed in the fall of 2021, have been put into place. The bill applies to individuals burning on private lands and changed the liability standard in California from simple negligence to gross negligence for an individual to be held personally liable for paying fire suppression costs — making it more difficult for prescribed burners to be found responsible when unforeseen conditions take the fire beyond its set boundaries.

nia’s legal requirements for fire ignition on public and private land. Prescribed burns that occur on private property have fewer legal requirements, as they don’t have to comply with larger governmental regulations or processes like the California Environmental Quality Act or the National Environmental Policy Act. Fulfilling these regulations and processes is a time-intensive process and can result in long processing periods and bureaucratic hurdles for burns.

According to Quinn-Davidson, policies required for prescribed burns on federal or state land or done with federal or state money results in longer planning processes “that could take several years to document and demonstrate that your project is not going to have negative impacts on important resources.”

Even as the state tries to change its attitude toward burning, legislative frameworks from the state’s past of fire suppression are in the way of California achieving its prescribed burning goals. As a result, many scientists argue that the work isn’t being done fast enough to reduce wildfire risk.

communities, where prescribed burning expertise is greatest. Now, she says

burn on private land owners, while liability of a prescribed burn on public

However, these legal asymmetries have not been resolved in Califor-

Now, California’s approach to tackling the legislative and liability frameworks, the workforce shortage and the knowledge gap to meet Newsom’s prescribed burning goals is still unclear.

by SOSIE CASTEEL

by SOSIE CASTEEL

America’s beloved volcanic archipelago, Hawai’i, checks every box for the perfect island getaway: gorgeous beaches, crystal-clear ocean waves, and delicious food. Formed by an active volcanic hotspot, this series of islands has recently become another type of hot spot — one for tourists. Tourism on the beautiful Hawai’ian islands continues to increase yearly, especially in the age of vacation rental platforms such as AirBnB and Vacation Rentals by Owner (VRBO). Even during the pandemic, millions of people chose Hawai’i as their destination.

Annually, the Aloha State attracts nearly 10 million visitors who bring in over 15 billion dollars

for the local economy. However, excessive travel has created a myriad of issues for Hawai’ian natives and the islands themselves. Besides the annoyance of obnoxious mainlanders stampeding across the lush forests and once-pristine beaches, the constant stream of visitors pushes natives into a housing crisis, contributes to habitat fragmentation and prostitutes Hawai’ian culture.

To understand the complex relationship of Hawai’i with the mainland, it is necessary to understand the imperialist background of the United States’ control of the islands. Americans have influencedthe Hawaiian islands since just after the arrival of European explorers in the late 18th

century. For centuries, the island chain prospered as a kingdom, relying on agricultural exports to sustain its economy. As a result of diseases spread through contact with Europeans, the population of Native Hawaiians on the island declined by hundreds of thousands until stabilizing in the mid 20th century.

In 1891, Queen Liliuokalani took the throne amidst financialturmoil in Hawai’i. Although she tried to preserve the power of the monarchy, Liliuokalani was deposed two years later by Americans and Hawaiian citizens of American descent who sought to hand the islands over to the United States. Hawai’i became a Republic and was soon annexed by the United States. In 1959 it became the 50th state, an event which set the stage for the modern influx of mainland tourists

Erin Carroll is a Environmental Science, Policy, and Management PhD student at the University of California, Berkeley who grew up in O’ahu. “I definitely do not feel that people who visit Hawaii are respectful of the land, its people, or the culture,” she said. “That isn’t necessarily their fault, and I believe most people come with an open heart and positive intentions. It’s just a lack of educational resources and an absolute tsunami of negative ones.”

Hawai’i is the most isolated archipelago on the face of the Earth, sitting thousands of miles away from any continental mainland. Underwater volcanic eruptions created the chain of islands, beginning around 70 million years ago. This is a process that continues today, with islands still being created due to gradual tectonic plate movement.

As an archipelago that is classifiedas a subtropical forest, Hawai’i is home to a great variety of unique species due to its distinct location. Its geographic isolation results in a lack of species immigration, and therefore extinction rates are far more detrimental to the overall biodiversity of the islands. More recently, Hawai’ian residents and climatologists have emphasized both the fragility of the ecosystems, as well as the relative scarcity of the islands’ natural resources.

Coral reefs in Hawai’i have experienced the most significantlosses due to excessive tourism. Hudson Slay, an EPA biologist in the PacificSouthwest Water Division, describes coral reefs as key

to the islands:hey provide habitats for local fiseries, protect the shores from heavy wave action and storm surges, and allow for offshore activities such as snorkeling.

While the EPA recognizes global threats to coral reefs, Slay’s department is dedicated to locating and mitigating local nonpoint sources of pollution that harm corals. “What happens is the coral gets stressed either by water temperature, excessive sediment, or some other stressor,” says Slay. “Then those zooxanthellae may be expelled from the coral skeleton and when that gets to a certain point the coral looks like it was dipped in bleach.” According to Slay, the threats to the reefs were prevalent before extensive travel to the islandsowever, the development of roads has increased runoff, a major source of nonpoint pollution to coral reefs.

Tourism, like any other industry, depends on natural resources. Hotels, which tend to be placed near water lines, demand a significantamount of freshwater for guests, golf courses and manufactured green spaces. Extreme water use has caused island-wide droughts and inflationin the price of freshwater for locals. Tourism, above all, takes up space. Land is scarce in Hawai’i, and tourists and corporations continue to push locals out of their homes and drive up the cost of housing for natives. The median cost of a one-family house in Hawai’i is over $1 million, one of the highest of any U.S. state.

The development of this limited land has a number of negative ecosystemic effects. Habitat fragmentation is the cause of most modern extinction in Hawai’i. For instance, the draining of ponds to make room for hotels and other infrastructure has left many migratory birds without a place to land and reproduce. The arrival of humans has induced more extinctions and threatened multiple plant and animal species on the islands. Endemic birds, spiders, flowers,marine animals, and many insects struggle to thrive in highly toured parts of the islands.

Hawai’i also sits right in the middle of swirling ocean currents close to an oceanic trash pile called the “Great PacificGarbage Patch.” Trash that was not even created by Hawai’i washes up on the shores of Hawaiian beaches. Fifteen to twenty tons of marine debris wash up on the relatively inac-

cessible Kamilo Beach every year.

In addition to littering the beaches, waste, mainly single-use plastics, litters fresh waterways and other places throughout the islands. Waste removal in Hawaii is complicated and expensive because trash has to be carried out of the islands by large boats to go to mainland landfills.Tourism exacerbates this crisis, as according to a study conducted by the Kohala Center, the average Hawaiian visitor generates over seven pounds of waste a day. With thousands of travelers staying on each island, the waste piles up and often ends up in natural spaces due to littering or wind.

Hawaiian natives have expressed their concern for decades, but many of the most crucial issues for the islands aren’t easily reversible or have complicated solutions. For instance, a decline in the industry that is responsible for so much environmental destruction would also cause many natives to suffer as it is an integral part to the island economy.

This is proven historically: The dip in travel after the attacks on September 11 left busy hotels and restaurants struggling to stay afloat.Tourism quickly picked back up after the period of mourning and incentive discounts on popular attractions. However, the post-9/11 circumstances demonstrated the potential negative effects of limitations on visitors.

Tourism, nevertheless, remains limited by geographical and environmental considerations. “Tourism is a huge part of the local economy, but the land is not infiniteand the tourism value will be better sustained in the long term if its capacity isn’t disregarded,” Carroll said.

Taking smaller, more specificsteps could slow the negative impacts of tourism without damaging the Hawaiian economy. Incentivizing limited water and energy usage in hotels or protecting green spaces, coupled with education about Hawai’i on the mainland may make tourism less harmful. In an interview with Spotlight Hawai’i, Hawai’i Lodging & Tourism Association President & CEO Mufi Hannemann described the industry as “open for business and trying to promote the fact that we are looking for respectful tourists.”

According to Slay, the Hawai’i Tourism Authority

provides potential travelers with tips to limit their impacts on both the natural aspects of the islands as well as the culture of the natives. Additionally, many airlines play informational videos or hand out pamphlets to their passengers in an effort to prevent common mistakes travelers may make during their island vacations. “If you don’t understand something, ask. Ask a lifeguard if you’re not sure if you should be somewhere,” Slay said.

Hawai’i represents both a challenge and an opportunity for conservation because of its diverse habitats that must be protected despite the swarms of curious travelers. This Pacificparadise can continue to thrive with more emphasis on careful traveler tactics and widespread education on the preservation of island environments.

Addressing tourism in Hawai’i reflectssome of the most pressing challenges in conservation: dealing with an industry that is simultaneously the lifeblood of a local economy and also the source of a large share of environmental degradation. With climate change on the horizon, Hawai’i’s success will depend on its ability to mitigate the drawbacks of its tourism industry without damaging it.

by Megan Mehta

by Megan Mehta

Conversations regarding big tech’s (Meta/Microsoft, Apple, Netflix, Google, Amazon; also known as MANGA) responsibility to maintain data security, privacy, and ethics are necessary but often overshadow the energy consumption and environmental damage these corporations also cause. Although many of them pledge to be carbon negative or carbon neutral in the next few decades, MANGA’s current energy consumption and harm towards the environment is unparalleled.