Painting with an Accent German-Jewish Émigré Stories

Barbara Loftus at work on The Grandparents Visit

Barbara Loftus at work on The Grandparents Visit

Barbara Loftus at work on The Grandparents Visit

Barbara Loftus at work on The Grandparents Visit

‘As much as I have an accent in my language, I have an accent in my painting’

Harry WeinbergerBen Uri Gallery & Museum in cooperation with the German Embassy London

Cover image: Draperies, 1939, Martin Bloch

Ben Uri Gallery and Museum wishes to extend sincere thanks to the German Embassy for supporting this virtual exhibition and catalogue and to all the artists and artists’ estates who have made this possible. We also thank the copyright holders for permission to reproduce the images.

Edited by Sarah MacDougall Production Alan SlingsbyI am delighted that the German Embassy London is once again working in partnership with the Ben Uri Gallery & Museum in London to mark and commemorate the 85th anniversary of the November Pogroms and the first Kindertransports to the United Kingdom with the digital exhibition Painting with an Accent: German-Jewish Émigré Stories.

“As much as I have an accent in my language, I have an accent in my painting”. This statement by Harry Weinberger vividly captures the feelings of émigré artists who carry both their old and new homes within them. Born in Berlin to a Jewish industrialist family, he only just managed to board the last Kindertransport with his sister to reach the safety of British shores. His journey and story stand for many Jewish émigré lives cruelly uprooted by the Nazi persecution. By exploring the legacy and heritage of Jewish émigré artists in this exhibition, we would like to pay tribute to the many German-Jewish émigrés who fled the Nazi regime and Nazi-occupied territories in Europe to find liberty and a new home in Britain. We would also like to honour the thousands of children and all the other refugees who were forced to flee their homes under traumatic circumstances on the Kindertransport or via other routes and leave their loved ones behind, most of whom perished in the Holocaust.

The anniversaries of the beginning of the Kindertransports and the November Pogroms serve as a call to action and an important reminder to us all that we – like the people behind the Kindertransport rescue operation – must prevent antisemitism, racism and populism from taking root again. Germany of all countries has a historic responsibility and defending our liberal values and protecting our democracy as well as the rule of law are at the heart of Germany’s political identity.

In this spirit, this exhibition will also shine a light on the legacy of these German-Jewish émigré stories for the next generations. Their voices and creativity must keep alive the message that we all need to remember the horrors of the Holocaust, especially now that the voices of the survivor generation are slowly fading away.

I would like to express my deep gratitude to the Ben Uri Gallery & Museum, especially its director Sarah MacDougall and its chairman David Glasser, for the opportunity to jointly tell and remember the stories of these German-Jewish émigré artists.

Miguel BergerAmbassador of the Federal Republic of Germany to the United Kingdom

Five years on from the exhibition Finchleystrasse: German Artists in Exile in Great Britain and Beyond, 1933-45 (2017), marking the 80th anniversary of the Kindertransport, the digital exhibition Painting with an Accent: German-Jewish Émigré Stories, once more in collaboration with the German Embassy London, marks the 85th anniversary of this important event. It presents the work of ten artists from German-Jewish émigré backgrounds – seven first-generation and three second-generation – whose personal lives, careers and artworks were either interrupted, impacted and/or lastingly influenced by their experience of Nazi persecution in Germany and subsequent resettlement in Britain.

Two older artists, Hans Feibusch and Martin Bloch, open the exhibition. Both left Germany as adults, prior to the Kindertransport, but through teaching and example became important influencers upon the younger refugee generation in Britain. At the exhibition’s heart are five artists, who came to Britain as children or adolescents, either directly on the Kindertransport, or under similar schemes: Heinz Koppel and Harry Weinberger, cousins, were both taught in London by Bloch; Susan Einzig and Eva Frankfurther, shared strikingly similar backgrounds but pursued divergent artistic paths, and Peter Midgley (né Fleischman), an orphan, who adopted the name of a welcoming English family, received a thorough art education from older refugee artists during internment (1940-41). All but Frankfurther went on to become influential art teachers themselves. Traces of their German inheritance – painting, as Harry Weinberger put it, with ‘an accent’, can be found in all their works, but they also responded to the succeeding decades and art movements with which they engaged in postwar Britain.

From the second-generation come three contemporary artists engaging directly with their tumultuous family histories: Julie Held, whose expressionistic paint handling implies a direct legacy and whose painting engages three generations of her own family; Barbara Loftus, whose ongoing series of large-scale peopled interiors meticulously recreates her grandparents’ apartment in Berlin and the story of their persecution and exile; and Carry Gorney, whose Burnt Histories series relates the stories of individual family members. Together, they remind us how closely life and art are intertwined and the continuing importance of history and legacy.

I would like to thank all the artists and their estates for their kind cooperation and the Ambassador Miguel Berger and Dr. Susanne Frane at the German Embassy London for their support in realising this online exhibition and catalogue.

Sarah MacDougall Director, Ben Uri Gallery and Museum Julie Held, Commemoration, 1993

Martin Bloch was born into an assimilated Jewish family in Neisse, Silesia (now Nysa, Poland) in 1883. He initially trained as an architect, later studied drawing in Berlin, and held his first solo exhibition at art dealer Paul Cassirer’s Gallery in Berlin in 1911. Between 1914 and 1920, he lived in Paris and Spain, then returned to Berlin, where he co-founded a painting school with Anton Kerschbaumer in 1926; after the latter’s death in 1931, he was assisted by ‘Die Brucke’ artist Karl Schmidt-Rottluff. In 1933, to escape Nazi persecution, Bloch fled to England, via Denmark, opening the School for Contemporary Painting in London with Australian painter, Roy de Maistre in 1934. There, his students included young refugee cousins, Harry Weinberger and Heinz Koppel, whose freedom of expression and love of colour he helped to develop. Bloch participated in the Exhibition of German-Jewish Artists’ Work at the Parsons Gallery (1934) and in the Exhibition of Twentieth-Century German Art at the New Burlington Galleries (1938) – the latter intended as a riposte to the notorious Nazi Entartete Kunst (‘Degenerate Art’) exhibition (1937); he held his first solo London show at the Lefevre Gallery in 1939.

Following the introduction of internment, Bloch was interned, first at Huyton Camp, Liverpool, then briefly on the Isle of Man. Afterwards, he exhibited in Oxford and Cambridge in 1941. In 1948 he became a guest teacher in Minneapolis and exhibited in both Minneapolis and Princeton, New Jersey, before resuming his influential teaching career in England. His fluid style of painting and spontaneous use of colour inspired his students at the Camberwell School of Arts and Crafts (1949-54). He exhibited regularly including with Ben Uri Gallery, where he held a joint exhibition with Polish émigré Josef Herman in 1949.

Martin Bloch died in London, England in 1954. His work is held in numerous UK public collections including the Ben Uri Collection and Tate.

Self-portrait, 1926

Oil on canvas

64 x 54 cm

Private Collection

© The Estate of Martin Bloch

Bloch’s Self-portrait, painted in 1926, the year that he co-founded a Berlin painting school with Anton Kerschbaumer, projects a quiet self-confidence. The work combines the instinctive, emotional approach of German Expressionism with a Fauvist love of colour, apparent in the ochre-yellow background.

Oil on canvas

68 x 79 cm

Ben Uri Collection

© The Estate of Martin Bloch

In 1934, eight years after his Self-portrait, Bloch was forced to flee Nazi Germany and made his way to England via Denmark, after accepting an invitation from the Danish novelist Karin Michaelis, who helped many émigrés including Bertolt Brecht. Svendborg Harbour, Denmark, a claustrophobic depiction of boats in a crowded harbour, is a classic symbol of exile. Despite the traumatic experience of flight, it is full of energy and colour as the forms are pared down into simple shapes and emotion is conveyed through the use of heightened purples, greens, and mustard yellows. The compression of the perspective into a single, suffocating plane jams the boats against the harbour and creates a distinct uneasiness. Later the same year, Bloch opened a second painting school in London with the Australian painter Roy de Maistre. There, and later at Camberwell School of Art, Bloch encouraged his students to paint with spontaneity and rhythm, beginning by establishing the painting’s dominant and then ancillary colour palettes, then juxtaposing warm and cool tones.

103.5 x 129.5 cm

Private Collection

Draperies demonstrates the enduring legacy of German Expressionism and is also Bloch’s only work to engage with his Jewish heritage. It was included, together with Svendborg Harbour, in his first solo exhibition in London at the Lefevre Gallery in 1939. Interviewed at the exhibition opening in February 1939, Bloch is quoted as saying that he saw the five yards of remaindered Manchester cotton in a shop in Kensington High Street and bought them on impulse. This complex study of overlapping textiles includes a six-pointed Star of David motif, set against a yellow background, both at the centre of, and partly concealed within the overall design, although the centrality of this symbol predates the Nazi decrees which enforced compulsory wearing of the star by those of Jewish origin. The painting highlights the freedom of artistic expression that Bloch found in exile and helped to instil in the next generation of both British-born and younger refugee artists.

Painter, muralist and sculptor Hans Feibusch was born into a Jewish family in Frankfurt, Germany in 1898. After serving in the First World War, he studied painting in Berlin, winning the Prix de Rome and travelling to Italy, where he admired Italian Renaissance mural paintings, before completing his studies in Paris. Upon his return to Germany, as a member of the Frankfurt Künstlerbund, he co-designed a series of murals. After winning the Prussian State Prize for Painting in 1930, he aroused Nazi antagonism; his pictures were publicly burned, and he was forbidden to paint. He found refuge in Britain in 1933, joining his British fiancée in London.

In 1934 Feibusch participated in the Exhibition of German-Jewish Artists’ Work at the Parsons Gallery, London, organised by German-Jewish émigré dealer Carl Braunschweig (Charles Brunswick) to highlight artists suffering persecution under the Nazi regime. Later that year, he held the first of five solo shows at the Lefevre Galleries, London, and exhibited regularly with the London Group (until 1939). In 1937 his work was included in the notorious touring Nazi Entartete Kunst (‘degenerate’ art) show, and in 1938 to the Exhibition of Twentieth Century German Art, the English riposte to the Nazi show, held at the New Burlington Galleries in London.

Following his first public mural commission in England in 1937, Feibusch was championed by Dr George Bell, the Bishop of Chichester, and executed some 35 Church of England commissions, including for Chichester Cathedral, becoming Britain’s most prolific muralist. In 1973 he was also commissioned by Holocaust survivor Rabbi Hugo Gryn, to execute five panels for the Stern Hall of the West London Synagogue (now in the Ben Uri Collection on long-term loan to St. Bonifatius Church, London, courtesy of the German Embassy London).

Feibusch exhibited widely including at the Royal Academy (from 1944), the Ben Uri Gallery, including solo exhibitions (1970, 1977), and at Pallant House Gallery, Chichester (1995). In the 1970s, forced to abandon painting after his eyesight began to fail, he took up sculpture. Although he had converted to Anglicanism in the 1960s, in his later years he reverted to his Jewish faith.

Hans Feibusch died in London, England in 1998 and his estate was bequeathed to Pallant House Gallery in Chichester. His work is also held in other UK collections including the Ben Uri Collection, Dudley Museums Service and Tate.

Feibusch’s Power, made in 1933, the year that Adolf Hitler was appointed to the German Chancellorship, unleashing the Nazi era, and precipitating the artist’s own flight to England, is both a personal response to the increasing anti-Semitism he encountered and a symbol of the wider persecution of German-speaking Jewry. Feibusch uses this dramatic vertical format and pyramidal structure to depict an image of violence and oppression. Created in the year he left Germany after his pictures were publicly burned and he was forbidden to paint, it is a harrowing depiction of a victim at the mercy of two oppressors, who close in upon him from both sides, their fists raised menacingly above his head. The bold yellow is the only colour in an otherwise subdued colour scheme with areas of brown and white chalk on brown paper. In another image, entitled Star of David, created in the same year, and using a similar composition, a lone male figure is shown with hands upraised in an attitude of supplication or horror and a flaming Star of David on a backdrop behind him.

Two years after Power, in 1935, Feibusch re-employed the same dramatic vertical format and pyramidal structure to create an ostensibly more playful, celebratory circus image but one that still highlights an ambiguous, coercive relationship in which the horse performs at the behest of his master’s raised whip hand.

Gouache on board

97 x 71 cm

Private Collection

© The Werthwhile Foundation

Oil on canvas

152.5 x 66 cm

Private Collection

© The Werthwhile Foundation

In 1943, in a third vertical picture, Feibusch further narrowed his canvas, compressing and elongating the composition to focus on the two intertwined figures at its centre. Here, he returns to the familiar New Testament parable of The Prodigal Son, from the Gospel of Luke, one of a number of biblical stories that he often explored as a prominent and prolific Church of England muralist. Here, the father’s loving forgiveness as he lays a gentle hand upon the kneeling figure of his wayward but repentant son, is a complete reversal of the first image of power and oppression. The light he holds aloft is an allegory for love and forgiveness.

Heinz Koppel was born into a Jewish family in Berlin, Germany in 1919 and showed an early interest in art, taking private lessons while still at school. Following the rise of Nazism, his family removed to Prague for safety in 1933, and here, Koppel took further private lessons from the painter Friedrich (later Fred) Feigl (who also later fled to England in 1939). In 1935 Koppel travelled to London and briefly studied under Martin Bloch at his School for Contemporary Painting until, after losing their German citizenship, the Koppel family became ‘stateless persons’, living briefly in Italy and Antwerp, before gaining Costa Rican citizenship and eventually returning to Britain in 1938. The family settled near Pontypridd, Wales in 1939, and Koppel resumed lessons with Bloch in London. In 1941 he took up a teaching position himself at the Burslem School of Art in Stoke-on-Trent and in he 1942 exhibited at fellow German-Jewish émigré Jack Bilbo’s Modern Art Gallery in London.

In 1944 Koppel moved to the mining town of Dowlais in South Wales, after accepting a post as an art teacher in the Merthyr Tydfil Educational Settlement (a school for workers and their families); he established the Merthyr Tydfil Art Society the same year. In 1947 he exhibited with the Welsh Arts Council, becoming head of the Dowlais Art Centre in 1948, and leading a Dowlais group exhibition at the National Museum of Wales in Cardiff, while exhibiting concurrently in London at both the Kingly Gallery and the Whitechapel Art Gallery. In 1956 he returned to the capital, exhibiting at Helen Lessore’s Beaux Art Gallery (1958, 1960, 1963) and participated in group shows at Ben Uri Gallery (1946 and 1960). He taught at Hornsey (1960) and Camberwell Schools of Art (1960-63), Liverpool College of Art (1964), and at the Slade School of Fine Art, before returning to Aberystwyth, where he spent his final years. His final exhibition was at the Oriel Gallery, Cardiff in 1978.

Heinz Koppel died in London, England in 1980. A retrospective was held at the Gillian Jason Gallery, London in 1988 and at the Berlin Centrum Judaicum in 2010. His work is in UK collections including the Arts Council Collection, Ben Uri Collection, the National Museum of Wales in Cardiff, Newport Museum & Art Gallery, and Tate.

Annunciation, 1950

Oil on canvas

50.5 x 63.5 cm

Heinz Koppel Picture Trust

© The Estate of Heinz Koppel

Koppel was one of many artists to revisit popular biblical stories, but his retelling of the Annunciation, in which the angel Gabriel announces to the Virgin Mary that she will conceive a son, Jesus, by the power of the Holy Spirit, is highly original. It follows convention only in the positioning of his figures – the angel Gabriel (left), the Virgin Mary (right) and the Holy Spirit fluttering above them – and perhaps also in Mary’s uncertain expression as she receives the news. The nakedness of both figures is highly unusual, as is their non-naturalistic treatment, and the foregrounding of details such as Gabriel’s enlarged and exaggerated hand as he plays a harp or lyre and Mary’s long, dangling earring. The vivid yellow palette which provides the backdrop to the composition conveys the joyful nature of the announcement.

Happy Family, 1953

Tempera on hardboard

102 x 76 cm

Heinz Koppel Picture Trust

© The Estate of Heinz Koppel

Happy Family was executed while Koppel was living in Dowlais, South Wales, initially working as an art teacher in Merthyr Tydfil Educational Settlement (a school for workers and their families), and then as Head of the Dowlais Art Centre, in the years when his own young family was rapidly expanding. As in his other compositions from this period, his bright palette and non-naturalistic treatment of the figures combine to create a mood of fantastical storytelling. The three children, particularly the central girl with her laughing expression, swinging plaits and skirt ballooning out behind her, appear to form a joyful chorus as they float above the town like angels; her rounded shape is echoed by the comical form of a bended figure at the centre of the composition, almost bisected by a telegraph pole towering above him. Two dogs play or scrap on the road beneath them while beyond the road the town is revealed through a series of colourful rooftops compressed like the folds of a concertina.

This monumental painting depicts two musicians - a male cellist on the left, seen in three quarter-face, as he stands waiting for his cue, resting his chin upon his hand – and a female harpist, seen in profile, draped over her instrument as she plucks at its strings. The presence of a musical score to the boy’s left and a music stand positioned far behind the girl, as well as the title, suggests they are engaged in a performance, yet the size, scale and positioning of the elongated and flatly painted figures, together with the presence of the harp, suggests a religious connotation, recalling the work of early Renaissance painters such as Fra Angelico and Giotto, and drawing an interesting analogy with Koppel’s own earlier Annunciation (1950). Their youthful forms, the girl’s white dress and red hair, are also reminiscent of Mary and the Angel Gabriel in Dante Gabriel Rossetti’s Ecce Ancilla Domini! (The Annunciation) (1849–50, Tate).

The Musicians, before 1960

235 x 102 cm

Heinz Koppel Picture Trust

© The Estate of Heinz Koppel

Harry Weinberger was born into a Jewish family in Berlin, Germany in 1924. His family were keen collectors, exposing him to art from a young age. Following the rise of Nazism, his family moved to Czechoslovakia in 1933, where they remained for six years, until the threat of German occupation, initiated by the annexation of the Sudetenland in 1938, caused him to flee to England with his sister, Ina, on the final Kindertransport in 1939. Initially apprenticed as a toolmaker, Weinberger joined the Queen’s Own Royal West Kent Regiment in 1944, and subsequently transferred to the Jewish Brigade, serving in Italy during the Second World War.

After the war he attended a life-class run by Welsh painter Ceri Richards, and decided to focus on art. His cousin, Heinz Koppel, with whom he was closely connected, was by then already engaged upon his own career as an artist. At Richards’ suggestion, Weinberger enrolled at Chelsea School of Art in London, where he was criticised for his ‘crude’ colour and moved to Goldsmiths College, but his main influence was Martin Bloch, who helped him to establish and develop his signature style and robust palette, and to forge a career both as a painter and a respected art teacher. Weinberger held his first solo exhibition at London’s Leger Gallery in 1952. Two years previously, he had begun his training as a teacher in Brighton and subsequently, taught art at schools in London and Reading, eventually becoming head of painting at Lanchester Polytechnic (now Coventry University) in 1964. The department was then at the forefront of British conceptual art and often challenged the methodology of painting. However, Weinberger’s appreciation for the medium prevailed and he continued to offer courses for students who were interested in adopting traditional approaches. On retirement in 1983, Weinberger moved to Leamington Spa in Warwickshire, where he continued to paint. His favoured subjects included interiors and still lives; however, he also painted portraits including one of his close friend, author, Iris Murdoch.

Harry Weinberger died in Leamington Spa, England in 2009. His work is in UK public collections including the Ben Uri Collection, the Government Art Collection, Manchester Metropolitan University, and the National Museum of Wales in Cardiff.

Welsh Village (in memory of Heinz), 1982

Oil on canvas

71 x 91 cm

Private Collection

© The Estate of Harry Weinberger

Welsh Village recalls and pays affectionate homage to both Weinberger’s own time in Wales and to the work of his cousin Heinz Koppel, who had earlier taught in South Wales. Like Koppel’s Happy Family – painted some thirty years earlier – the cluster of houses, huddled together against the backdrop of a hill, is central to Weinberger’s composition; while Koppel’s figures are separate from the town and float above it however, Weinberger’s are so firmly embedded within their landscape that they even share the same palette. The use of vivid greens and blues throughout, with colour applied in pure, unmodulated passages of paint, has the effect of blending and uniting the seemingly disparate elements of town and countryside into a harmonious whole.

Brooklyn Heights

Acrylic on canvas

130 x 130 cm

Private Collection

© The Estate of Harry Weinberger

Weinberger was a frequent traveller and made numerous drawings, which often inspired later compositions in which he employed recurring motifs such as the sea, seascapes, harbours and ships. Brooklyn Heights uses familiar elements of his style: bold, nonnaturalistic colour is applied in broad, flat strokes to create a shimmering whole, as the East River snakes through a townscape bounded by high buildings jostling against the skyline and contrasting lower dwellings, perhaps the remnants of old residential brownstones.

Weinberger’s love of bright colour reaches its zenith in his painting of rural Tuscany, glimpsed through a window on a summer’s day. In place of the muted tones typically used to depict the vernacular pan-tiled roof, the artist prefers a joyous clash of reds and blues, picked up in flashes of colour in the sky beyond and contrasting with the verdant green of the countryside beyond the window.

Window in Tuscany

Oil on canvas

76 x 51 cm

Private Collection

© The Estate of Harry Weinberger

Painter, printmaker and teacher, Peter Midgley (né Fleischmann), was born into a Jewish family in Berlin, Germany, in 1921; orphaned by the age of two, he was raised by his maternal grandfather, following whose death in 1931, he was sent to the Auerbach Orphanage for Jewish Children. He studied briefly at the Royal School of Art in Berlin before forced to flee Nazi persecution, arriving in England on a Kindertransport in 1938. He later adopted the surname of the Midgley family in Manchester, who befriended him. Following the introduction of internment, Midgley transited through Warth Mills and Prees Heath camp, north Shropshire, and was finally interned in Hutchinson camp on the Isle of Man, where he received a comprehensive arts education from fellow German-speaking internees, particularly Merz-founder Kurt Schwitters, self-taught painter Fred Uhlman, and sculptors Paul Hamann (German) and Georg Erhlich (Austrian).

Postwar, Midgley trained at Beckenham School of Art (1947–51), then the Royal College of Art, gaining the prestigious Rome scholarship (1953–4). He exhibited extensively in London, particularly with the Redfern Gallery and Royal Academy and taught at Beckenham School of Art (1955-65), and Ravensbourne College of Art and Design (1966-86). A versatile artist, his work spanned various media, including painting, sculpture, printmaking and murals for several prominent architectural projects including a floor design for Liverpool Cathedral.

Peter Midgley died in London, England in 1991. His work is in UK public collections including the Government Art Collection, the Victoria Gallery & Museum, Liverpool, and the University of Warwick Art Collection.

Circular Diamond, c. 1969

Folded paper

76.2 x 76.2 cm

Private Collection

© The Estate of Peter Midgley

During the internment of so-called ‘enemy aliens’ in Britain and the Commonwealth (1940-41), 19-year-old Peter Midgley (then using his given name of Peter Fleischmann) was interned at Hutchinson Camp on the Isle of Man, known informally as ‘the artist’s camp’. There he received such a thorough art education from German refugee artists including the Dadaist Kurt Schwitters, painter Fred Uhlman, and sculptors Paul Hamann and the Austrian Georg Ehrlich, that he described everything he later learned at art school as ‘just a recap’. Midgley’s later practice was often experimental, and he worked in a variety of media including a series of at least three abstract reliefs in 1969. Expertly constructed from tightly folded newspapers woven into different designs, they show the legacy and influence of Schwitters, celebrated for his Merz, in which he repurposed found and discarded materials. Another version, entitled Paper Maze (1969), is in the collection of Warwick Arts Centre at the University of Warwick.

Summer Heat Sunset in Yugoslavia, 1977

Silk-screen print

87.6 x 117.4 cm

Private Collection

© The Estate of Peter Midgley

A decade later, Midgley’s screen print captures the essence of a scorching summer evening at sunset in Yugoslavia through a succession of melting stripes of colour stretching in bands across the horizon. The ancient process of screen printing, which probably originated over a thousand years ago in China and was only introduced to the West in the late eighteenth century, was popularised by Andy Warhol in the mid-twentieth century, who established it as a major technique. Midgley uses this highly skilled process to experiment with line and colour.

Self-portrait, c. 1990

Oil on canvas

Dimensions unknown

Private Collection © The Estate of Peter Midgley

Midgley was a versatile painter, printmaker, sculptor and muralist, whose practice spanned many genres including portraiture. His self-portraits span his long career. This one, painted in the year before his death, is considered an excellent likeness by his family and demonstrates an undiminished passion for colour.

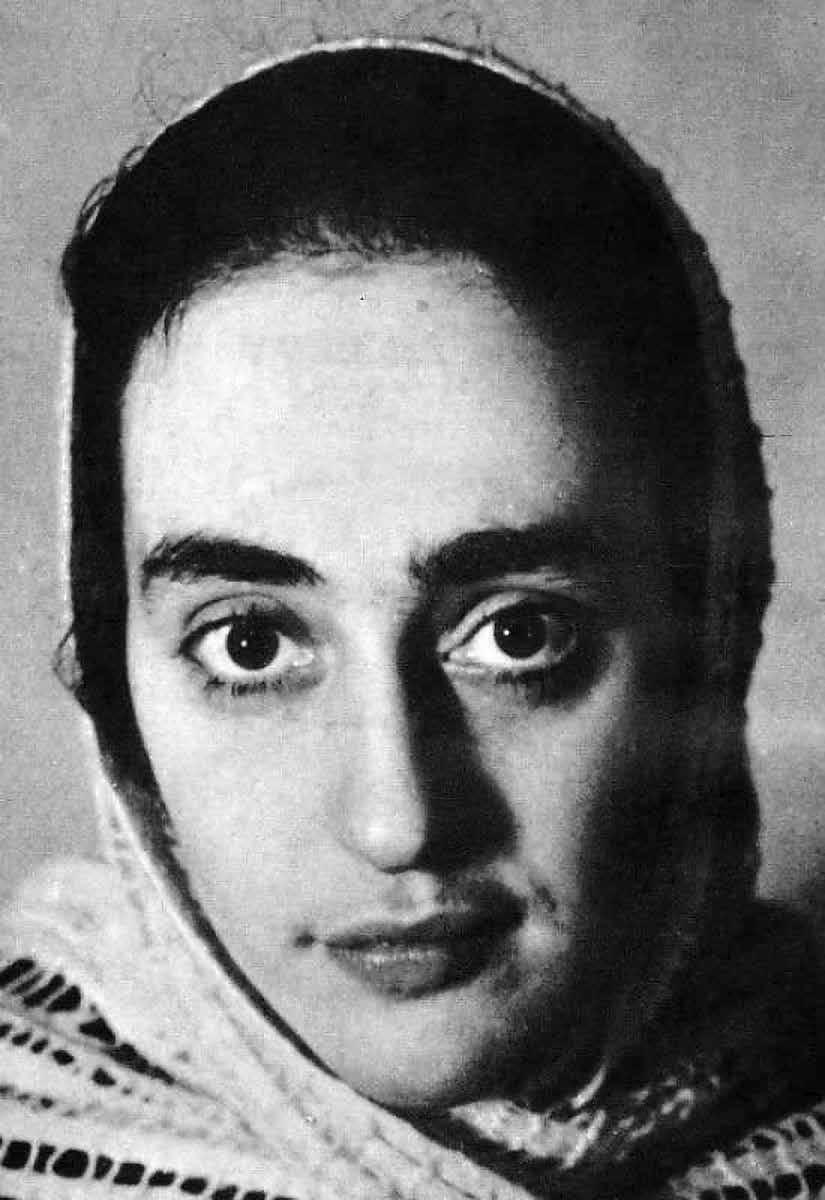

Susan Einzig

Private collection

Susan Einzig

Private collection

Illustrator and painter Susan Einzig was born into an assimilated Jewish family in the Dahlem district of Berlin, Germany in 1922; her father encouraged her early interest in art and illustration. After being expelled from the local Lyceum because of her Jewish origins, she studied briefly at the Breuer School of Design in 1937. In 1939 she boarded one of the final Kindertransports to England, later followed by her mother and brother; her father perished in a concentration camp. She enrolled at the Central School of Arts and Crafts in London (relocated to Northampton during the war), studying drawing under Bernard Meninsky and Morris Kestleman (both of Jewish origin), and William Roberts, illustration under John Farleigh, and wood engraving under Gertrude Hermes. This ‘nourishing’ experience was followed by a difficult period as a technical draughtsman, a position secured through the designer Abram Games, for the War Office, and she was released from service days before the end of the war.

Afterwards, Einzig pursued a career as a freelance illustrator, specialising in children’s books, including Norah Pulling’s Mary Belinda and the Ten Aunts (1945), and most notably, Philippa Pearce’s Tom’s Midnight Garden, for which she was awarded the National Book League’s Illustration Prize. Other titles included Alphonse Daudet’s Sappho: A Picture of Life in Paris (Folio Society, 1954), and E. Nesbit’s The Bastables (Franklin Watts, 1966). From 1947 onwards, Einzig was a regular illustrator for magazines including the best-selling Radio Times and Lilliput. She taught at Camberwell School of Arts (1946–51), where she met artist John Minton – a close friend and significant early influence –followed by St Martin’s (1948–51), Beckenham (1959–60), and Chelsea Schools of Art (1959–65), where she became a senior lecturer in 1966, until her retirement in 1988. A member of the Artist Partners and the Society of Industrial Artists, she also designed posters for London Transport and the Empire Tea Board, among others; in her later career, she resumed painting, holding a solo exhibition in 1975.

Susan Einzig died in London, England in 2009. Four of her pen-and-ink drawings from Tom’s Midnight Garden are held in Seven Stories, the National Centre for Children’s Books, Newcastle upon Tyne.

Self-portrait, c. 1940

Oil on board

27 x 20.5 cm

Current whereabouts unknown © The Estate of Susan Einzig

Susan Einzig’s youthful self-portrait, with its direct gaze, was probably painted about a year after she arrived in England as a refugee, during her time at London’s Central School of Art. The dark interior with its still life composition and free brushstrokes suggests a link to her German origins, while her later painting was more post-Impressionist in style and technique. Her self-portrait sketch (below) also dated to around 1940, is bolder, sparer, and more modern in execution, shorn of any unnecessary detail, and also more introspective.

Self-portrait, c. 1940s

Pencil

Dimensions unknown

Current whereabouts unknown

© The Estate of Susan Einzig

Illustration to Tom’s Midnight Garden, 1958

Pen-and-ink on paper

Private Collection

© The Estate of Susan Einzig

Illustration cover to Tom’s Midnight Garden

by Philippa Pearce, 1958

Watercolour

Private Collection

© The Estate of Susan Einzig

Perhaps Einzig’s best-known work is her series of evocative black-and-white illustrations to the children’s book, Tom’s Midnight Garden by Philippa Pearce, published in 1958, which earned her the National Book League’s Illustration Prize. This celebrated story, a narrative of love and loss, slips between fantasy and reality as the protagonist, Tom, attempts to lay to rest the ghosts of the past. Einzig is known to have visited Pearce and made careful notes in her preparation for this work, but it seems likely that the memory of the lost Eden of her own Dahlem childhood – living in a three-storey house, surrounded by a large tree-filled garden, where she played with her brother, Rolf –haunts these images. This is underpinned by her use of hand-rendered titles in the Neo-Romantic manner on the jacket, leading Martin Salisbury, Professor of Illustration at Cambridge School of Art, Anglia Ruskin University, to call Tom’s Midnight Garden ‘one of the most iconic book cover designs.’

In her later years Einzig returned to painting, particularly landscapes. A recurring motif of a path winding up and away between trees, sometimes including two figures walking towards or away from the viewer, has been collectively observed by the art historian Frances Spalding and the artist’s daughter, Hetty Einzig, as ‘a return’ – whether conscious or unconscious – ‘to the core themes carried over from her childhood: attachment, separation and loss’.

Eva Frankfurther was born into a cultured and assimilated Jewish family with a strong leaning towards the arts, in Berlin, Germany in 1930. Following the rise of Nazism, she escaped to London with her siblings in April 1939; her father and stepmother followed afterwards, just prior to the outbreak of the Second World War. After a year at Stoatley Rough, a mixed boarding school in Haslemere, Surrey for German refugee children, she was later evacuated with her sister, Beate, to Hertfordshire for a further four years.

Between 1946 and 1951 Eva studied at St Martin’s School of Art, where her fellow students included Leon Kossoff and fellow child refugee from Nazism, Frank Auerbach, who recalled Frankfurther’s ‘contempt for professional tricks or gloss’ and her work as ‘full of feeling for people’. Disaffected with the London art scene, after graduating, she moved to Whitechapel. For the next six years, she earned her living working the evening shift as a counterhand at Lyons Corner House and, later, in a sugar refinery, leaving herself free to paint during the day. Inspired by artists as diverse as Rembrandt, Käthe Kollwitz and Picasso, she took as her subject the ethnically diverse, largely immigrant population among whom she lived and worked. Her studies of the new Caribbean, Cypriot and Pakistani communities, as well as Jewish, Irish and Italian East Enders, portrayed both at work and at rest, with empathy and dignity, are her greatest achievement. Never without a sketchbook, she also made hundreds of vivid sketches, occasionally from life, most often from memory, usually in a few telling lines. Despite exhibiting regularly in local group shows at the Whitechapel Art Gallery and the Bethnal Green Museum, she rarely signed or dated her work, often selling it at low prices or giving it away to friends.

Between 1948 and 1958 Frankfurther also travelled extensively in Europe and the USA. In her last year, she spent eight months living and working in Israel, where a large body of her work was stolen. She returned to London in October 1958 and, suffering from depression, took her own life in London, England in 1959. Retrospectives were held at Ben Uri Gallery (1962) and Clare Hall, Cambridge (1979), followed by an important exhibition at the Boundary Gallery, London in 2001, and two further exhibitions at Ben Uri Gallery in 2014 and 2017. Her work is held in UK collections including the Ben Uri Collection and Clare Hall, Cambridge.

Eva FrankfurtherBeate

PlanskoyBlack-and-white photograph

© Beate PlanskoySelf-portrait in Red, 1951-58

Oil on paper, 76 x 55 cm

Private Collection © The Estate of Eva Frankfurther

When Eva Frankfurther’s posthumous exhibition at Clare College, Cambridge in 1979 was reviewed by art historian and critic Frank Whitford, he observed: ‘The work on show is so good that I wondered why I had not heard of Eva Frankfurther before. It did not surprise me to find that she was a refugee from Germany, coming to Britain at the age of nine, for her style of portraiture belongs so clearly to a German tradition’ (Cambridge Evening News, 27 November 1979).

This half-length self-portrait is one of Frankfurther’s boldest and most Expressionist. Wearing a vivid red jumper (identified by her sister as one of her favourites), she shows herself with a painting rag in her right hand, which is shown over-large, perhaps to emphasise her profession, although no further tools of her trade are included. After the war, materials were still scarce and expensive, and Frankfurther worked predominantly in oil on paper. Here, paint has been thinly applied in vertical streaks, particularly in the lower half of the picture, where at times the paper shows through, and in denser layers to the hands, neck and face, the latter finished with a firm, black outline.

West Indian Waitresses, c. 1955

Oil on canvs, 76 x 55 cm

Ben Uri Collection

Presented by Beate Planskoy (the artist’ sister), 2015

© The Estate of Eva Frankfurther

Frankfurther often focused on women’s faces and postures, observing her subjects with empathy and dignity, although typically they neither smile nor engage with the viewer. In her half-length double portrait of two Caribbean waitresses at Lyon’s Corner House, she employs loose brushwork and a restricted palette. The composition is carefully arranged so that the two waitresses appear to mirror one another, implying their close personal as well as professional relationship. Frankfurther’s migrant Corner House workers also document the changing landscape of postwar Britain with its new multicultural communities and changing working practices. The rose-coloured background is also typical of the ‘feminine’ palette that indicates Frankfurther’s instinctive sympathy for working women.

Woman with Two Children, c. 1955

Oil on paper

76 x 54 cm

Private Collection

© The Estate of Eva Frankfurther

In Woman with Two Children, the vivid scarlet of the toddler’s dress and bow and the mother’s Titian-red hair, stand out against the muted background and her drab overcoat, suggesting the biting postwar austerity of the family’s straitened lives. The composition is strengthened by an invisible diagonal that binds the two children to their mother.

Julie Held was born in London, England in 1958, the daughter of GermanJewish émigrés who both fled Nazi Germany in the 1930s and made their lives in England. Her mother, Gisela Held, was a professional sculptor and Julie was fascinated by drawing from an early age. She trained at Camberwell School of Art (1977-81), followed by a post-graduate diploma at the Royal Academy Schools (1982-85). She is the recipient of a number of awards including the Picker Fellowship, Kingston Polytechnic, where she had her first solo exhibition in 1982, and The Brandler Prize in 2002. Her painting, Girl with a Cat (a portrait of her niece) was purchased by Ben Uri Jewish Artist of the Year Award in 1991. She held a solo show at Ben Uri Gallery in 1996, followed by a joint exhibition with Shanti Panchal, Regard and Ritual, in 2007. Held has had solo exhibitions in Prague, Leipzig and Hamburg, as well as in London, at Eleven Spitalfields Gallery (2014), followed by a joint exhibition with her former tutor Tony Eyton (2017), and a further solo exhibition at the London Jewish Culture Centre (2015). She regularly exhibits at group exhibitions including the Royal Academy summer exhibitions, The Jerwood Drawing Prize, The Threadneedle Prize and her portrait of her father, Peter Held, My Father (2011) was shortlisted for the B.P. Portrait Award.

Held is a former tutor at the Camden Institute, the Barnet College of Further Education, and the University of Wolverhampton, and is currently a visiting lecturer at the Prince’s Drawing School in London. She was elected a member of the Royal Watercolour Society in 2003 and is also a member of the London Group.

Held is currently a visiting lecturer at the Royal Drawing School in London. She was elected a member of the Royal Watercolour Society in 2003 and is also a member of the London Group, the New English Art Club and the Arborealists. Her work is in UK collections including the Ben Uri Collection; Nuffield College, Oxford University; the Open University; the Ruth Borchard Portrait Collection; and The Women’s Art Collection, Murray Edwards College, Cambridge University, as well as The Thomas Choir School, Leipzig.

Memory and identity are important concepts in Julie Held’s art. She has commented elsewhere that her ‘sense of Jewishness’ is broadly based within the German Jewish tradition. ‘All émigrés’, she has noted, ‘must experience the dilemma of assimilation and the retention of identity’. Colour is also central to her practice, expressing poignancy and an ongoing preoccupation with the powerful yet fragile cycle of life.

In Commemoration, the anniversary being marked is not clear – an element of mystery often lies at the heart of Held’s narrative paintings – but the gathering includes three generations of women, including the artist’s aunt and her sister (sat with her back to the viewer) regarding her own reflection in a mirror. The healthy complexions of the younger women are in stark contrast to the pallor of the elders, especially against the acid yellow of the window. The still-life objects and the mirror together function as a ‘memento mori’ –suggesting the transience of life.

Commemoration, 1993

Oil on canvas

152.5 x 107 cm

Ben Uri Collection

Purchased 1993

© Julie Held

The Shoe Shop, 2004

Oil on canvas

90.8 x 86 cm

Ben Uri Collection

Presented by the artist 2008

© Julie Held

Shoe Shop III, the third in a series of paintings of this title, combines self- portraiture with the artist’s ongoing interest in the symbolic value of objects and in shops as subject-matter, stemming from childhood visits to Florence. The red shoe, an object of desire, recurs in several of Held’s paintings, particularly in relation to women. The window is a further recurring motif that separates the subject from the objects, and the viewer from them both, also allowing both artist and viewer to stand on the outside looking in.

Held’s deeply felt portraiture is centred on a familiar cast of sitters, chief among them her father, Peter Held, the subject of numerous portraits over the years and, until his death in 2018, probably her most frequent sitter; each session deepening the bond between them both as father and daughter, as well as artist and sitter.

Peter Held, born into a Jewish family in Leipzig, Germany, fled to England in the 1930s but (unlike the artist’s mother, Gisela), frequently returned to his birthplace in later life, receiving the freedom of his native city shortly before his death. In this moving portrait, shortlisted for the 2011 B.P. Portrait Award, he is portrayed as a dignified, ageing figure, sitting patiently in his chair, wrapped against the cold, calmly meeting the viewer’s gaze.

Painter and filmmaker Barbara Loftus was born to an Anglo-Irish Catholic Communist father and a German-Jewish mother in London, England in 1946. Her mother, Hildegard, who had fled Nazi Germany in 1939, was the only member of her family to survive the Holocaust but revealed nothing of her past until she was in her 80s when her revelations compelled Loftus to undertake an artistic exploration of her family’s past and the lost world of her German-Jewish inheritance that is still ongoing. She cites a current theory that the second-generation, often the daughter, ‘carries the candle’ for such legacies. In this sequence of three works (part of a larger series), she has reconstructed the aura of the home life of the family she never knew. These artworks, centred on the ‘topography of home and location’, are meticulously realised, always rich in period detail, though often muted in palette, and executed on a monumental scale, detailing episodes from her relatives’ past.

Loftus’ solo exhibitions have been held at numerous locations including the Freud Museum, London (2011), Schöneburg Jugend Museum, Berlin (2013) and Ephraim Palais Stadtmuseum Museum, Berlin (2013-14). Her work is held in UK public collections including the Towner Eastbourne.

Her latest publication is Barbara Loftus: The Distanced Observer (2022), combining testimony, excavation and interpretation, with essays by art historian Dr. Deborah Schultz and Exile Studies specialist Prof. Lutz Winckler.

The Grandparents’ Visit fabricates a detailed interior typical of a comfortable, respectable, middle-class German household prior to the Second World War. The grandparents and granddaughter (the artist’s mother) all face outward as if posing for a photograph: they are well-dressed, but not ostentatiously so, although the grandfather’s handkerchief seems to have been arranged with a slight flourish and the granddaughter’s hair is dressed in a large bow which, together with her neat, matching dress suggests she has been suitably attired to receive visitors. A maid, shown in profile, busy with a minor task at the table, is less defined, a less tangible presence than the others, who are shown at leisure: the grandmother holding a pug across her lap; the grandchild showing a book, perhaps a little selfconsciously, to her grandfather.

In the background we see objects typical of such a household: china ornaments on a cabinet, a framed picture, an elaborate light fitting, and solid, comfortable seating, all indicative of and supporting the solid framework of these similarly comfortable and respectable lives.

The Grandparents Visit, 2020-2022

Oil on canvas

213 x 152 cm

The Artist’s Collection

© Barbara Loftus

In this interior scene, the setting is ostensibly unchanged: we see a similarly comfortable room: a large table covered with a tablecloth, chairs with carved backs, a large, wooden, mirrored fireplace surround covered with framed photographs and numerous framed prints and drawings on the walls behind them. Nonetheless, the quiet intimacy of The Grandparents’ Visit has disappeared, replaced with an atmosphere of tension and anxiety as a middle-aged couple and a young man – presumably their son – contemplate the application of the title: the woman sits, chin in hand, studying several sheets of paper spread on the cloth before her, holding another tightly in her hand; the older man sits slightly back in his chair, looking out abstractedly, as though in exhaustion or disbelief; while the younger man stands with hands folded over the chairback, patiently looking on. We can only assume that this may be an application for a German passport (Deutsches Reich Reisepass), which would have been stamped on the first page with the red letter “J” to identify and isolate Jewish citizens, but would also be needed to gain vital passage out of Germany.

Confiscation – photographed on the easel to show its size and scale – emphasises the monumentality of this suite of paintings: capturing and pinning down the domestic details of homes and lives similarly ostensibly solid yet fatally disrupted, dispossessed, scattered, and lost. It also refers back specifically to the first incident of her history that the artist’s mother shared with herwhat Barbara Loftus has called a ‘late-life unburdening to me of her formative years in pre-war Berlin’: when, a few days after Kristallnacht, two stormtroopers arrived at her grandmother’s house carrying a tea chest and demanded that she open the china cabinet, which they then emptied with care, removing each porcelain figure, wrapping it in tissue paper and laying it in the chest, before moving on to do the same with the family silver. We view this scene as though we are standing behind the table with the two women on either side, looking into the room beyond as the systematic looting and unravelling of the family’s life begins.

Artist, writer, and psychotherapist Carry Gorney was born in 1945 in Leeds, England to German Jewish refugee parents, who left their native Berlin on their wedding day in 1937.

She recalls: ‘My father used to tell me about his life in Berlin before the war. I snuggled down into images from a pre-war Ashkenazi world, beginning the century before last. The nuggets of his life were tucked into music, always a tune, a song. I grew up listening to the symphonies of German composers and my own soul returned to Mittel Europa. The processions of musicians walking across our landscape held the beat of my father’s heart, the rhythm of his life, a language beyond words. Music had been the only constant in the chaos of his changing world.

We were raised between two languages. Our family inhabited an in-between world, they moved from a word in one language to a sentence in another. I never knew which language was which. My syntax still betrays my German background. German was the language of our nursery rhymes. We were lifted, held, hugged, tickled in German. Strong accents wrapped themselves around us like a blanket. We lived in a no-man’s land, an émigré country; the German world they created through the stories they told, the music they danced to, the embroidery they never finished and the friends who had disappeared.’

In 1966, when Carry graduated in Drama from Manchester University, she had already become a listener, and collector of stories; going on to make comics with young offenders, teaching improvisation at the Jacob Kramer College of Art, Leeds, then becoming one of the pioneers of the Community Arts movement in the 1970s, turning stories within local communities into plays and processions on the streets, where costumes, banners and scenery were made from discarded, scrap and recyclable materials. She later used video to initiate participatory programmes with Cable television, involving isolated young parents, and eventually developed this work with babies and their mothers in the NHS.

Burnt Histories: Thea, 2017

Collage with photography and textiles

30 x 40 cm

The Artist’s Collection

© Carry Gorney

Carry Gorney has observed that her ‘goal has always been to strengthen the threads which connect us across beliefs, across ethnicity and across time’. In her series of textile, mixed media and stitch collages, Burnt Histories (2017), she traces the exilic stories of her three great aunts, who fled Nazi persecution to settle in England: ‘homeless, stateless, carrying their embroidery and old photographs, the last fragments of their vanished world’. Her publication of the same title follows her memoir, Send Me a Parcel with a Hundred Lovely Things (2015), which considers how her own life was shaped by her refugee antecedents and their experience of displacement and reinvention.

The series includes each individual family member’s story, among them that of the artist’s mother, Thea, who is shown, aged seven, on her first day at school in Berlin, in a photograph on the left of the composition, printed on burnt and torn organza.

Burnt Histories: Rhea, 2017

Distressed image overlaid on frayed and torn embroidery and attached to hand stitched painted lace

35 x 32 cm

The Artist’s Collection

© Carry Gorney

Rhea was one of the artist’s great aunts, who fled Germany with only a handful of photographs, embroideries and lace. This piece employs a double image: a photograph printed twice onto burnt organza and overlaid on frayed and torn cotton; distressed Tyvek (a unique, non-woven material) is then embellished with fragments of transfer foil and painted lace attached with hand stitching.

Burnt Histories, 2017

Collage with textiles and photography

41 x 58 cm

The Artist’s Collection

© Carry Gorney

This larger collage, which takes the series title, Burnt Histories, was completed after the individual tales and draws together these threads and fragments of the earlier stories, circling us back to the first generation of German-Jewish émigrés and the vestigial fragments of their lives. The piece comprises multiple layers of torn, painted German newspapers and photographs re-torn in strips to form seven layers, embellished with gold thread, Micah flakes, lace fragments and hand stitching.

An entry from the artist’s diary reads:

I imagine burnt out buildings - Dresden, Coventry, Berlin. I must paint a cityscape; my ancestors were urban. I ripped and tore all day. Seven layers in vertical strips to represent the broken buildings, the broken lives. Only the children between the crumbling and torn mass, pale little faces against the burning city …

Pieces of burnt synthetics, photo fragments, an image of debris … I iron down the black Micah fibres, rubbing with my fingers the charcoal and smearing paint on and scraping it off. It has layers, orange and blue but more brownish and greyish. Before applying the organza burnt pictures, I’ll stain the buildings …

If I stepped into my picture, I would become German and I would be gone.