BENNINGTON

Bennington Day is April 16!

Join us in celebrating Bennington College’s first-ever annual day of giving! Your gift on Bennington Day can help unlock challenge dollars to support our incredible students. Let’s come together and celebrate all the ways this remarkable place has shaped your path.

Give now. Be counted as an early donor! Make your Bennington Day gift online via the QR code below or mail the envelope, enclosed on page 56, by April 16.

Together, we can preserve and advance the Bennington you love for the classes of the future.

bennington.edu/benningtonday

BENNINGTON MAGAZINE

Ashley Brenon Jowett

Editor and Director of Communications

Kat Hughes

Art Director and Designer

David Morelos Zaragoza Laguera Photographer

Natalie Redmond

Associate Writer

Jeffrey Perkins MFA ’09

Associate Vice President, Communications and Marketing

David Buckwald

Vice President for Enrollment Management and Marketing

CONTRIBUTORS

Ben Hewitt

Charlie Nadler

Edwin Ozoma MFA ’19

Elizabeth Zimmerman ’66

TO SUBMIT

Bennington Magazine welcomes letters, opinions, essays, interviews, thought pieces, fiction, nonfiction, poetry, captioned work samples, and personal and professional updates. Please send submissions, proposals, and story ideas to magazine@bennington.edu. All will be considered. Due to limited space, we may not be able to publish all submissions.

CORRECTION

There were two misspellings in the “Bennington Writing Seminars at Thirty” article that appeared in the Fall 2024 issue: the names of Eugenie Dalland and faculty member Taymour Soomro. We regret these errors and have taken steps to prevent similar errors in the future.

Bennington Magazine is printed on stock that is Forest Stewardship Council® and Preferred by Nature™ certified, and is designated Ancient Forest Friendly™. The cover is made from 30% sustainable recycled fiber and the interior from 100% sustainable recycled fiber.

Dear Alumni and Friends,

What truly transforms a college student’s life? The answer is remarkably clear: According to a landmark Gallup* study, it’s the powerful combination of dedicated faculty mentorship and real-world learning experiences. Students who receive these advantages achieve extraordinary levels of personal fulfillment and professional success throughout their lives.

This is precisely what sets Bennington apart. Through our distinctive emphasis on faculty advising and the Plan process and innovative Field Work Term placements, we don’t just meet these crucial benchmarks—we define them. Every Bennington student experiences individualized mentorship and real-world engagement; less than five percent of students at other colleges nationwide receive the same.

The study’s findings resonate with our alumni’s achievements. Take Andrea Tapia ’15, cofounder of GANAS. Faculty members Marguerite Feitlowitz and Jonathan Pitcher empowered her “to push boundaries—social, intellectual, and personal—and find ways to create things from scratch, even when it felt unrealistic.” Or consider Jessica Smith ’23, whose Field Work Term inspired her to establish an artists’ collective dedicated to social change. These are just two examples of how Bennington graduates transform their education into meaningful lives and make an outsized impact.

Throughout this issue of Bennington Magazine, you’ll discover stories that illuminate our unique educational approach—one that cultivates audacity, deep curiosity, profound compassion, and fierce resilience. You’ll see how the Bennington experience shapes not just careers but lives devoted to positive change.

Yet maintaining this transformative model of education requires significant resources. While other institutions may be content with lecture halls and traditional internships, Bennington’s commitment to intensive mentorship and immersive learning demands a deeper investment. This is where you come in.

Your support isn’t just about maintaining an institution; it’s about preserving and strengthening a proven path to lifelong success and fulfillment. Every gift helps ensure that future generations of students will receive the same life-changing combination of mentorship and real-world experience that makes Bennington extraordinary.

Join me in securing Bennington’s future. Your donation will help sustain the very elements that make our college unique: the close faculty relationships, the real-world experiences, and the innovative spirit that transforms students into creative, engaged citizens who make our world better.

With gratitude,

Laura R. Walker President | Bennington College

*“Harnessing the Life-Transformative Powers of Higher Education” from the September 2024 issue of Liberal Education from the American Association of Colleges and Universities

After

14 From Crisis to Collaboration

Bennington College and former University of the Arts faculty and students dance into the future.

20 Bill Dixon and the Black Music Division

Learn about how one man advocated for Black music’s rightful place within the academy. 26 One Acre, Big Influence

Bennington’s Purple Carrot Farm makes an outsized impact. 32 Self Starters

Bennington alumni make the lives they want and places for others.

First & Foremost

1 How to Make Your Podcast Pop

On October 25, 2024, Bennington College hosted a Podcast Symposium that brought together seventy-five students, podcasters, writers, journalists, and podcast fans for an afternoon of networking and learning.

Bennington College President Laura Walker, former CEO of New York Public Radio, hosted the event with Andrea Bernstein, presidential fellow and visiting faculty member at Bennington and a Peabody and duPont award-winning journalist and creator of podcasts like Will Be Wild and Trump, Inc.

“Podcasting is an intimate and powerful medium for storytelling, journalism, and creative expression,” said Walker. “This event was an opportunity to learn from some of the most talented podcasters.”

Guests included Tonya Mosley of NPR’s Fresh Air and She Has a Name; Kat Aaron, vice president of Development at Pineapple Street Studios; Lauren Chooljian and Jason Moon ’13 of the Pulitzer-nominated 13th Step from New Hampshire Public Radio; Peabody award-winning podcaster Erica Heilman of Vermont Public Radio’s Rumble Strip; Matt Katz of Inconceivable Truth; Cynthia Rodriguez, senior editor at Reveal and editor of 40 Acres and a Lie; and Emily Russell of North Country Public Radio’s If All Else Fails.

“This Podcast Symposium was a chance for the Bennington community to engage with some of the best podcasters in the business,” said Bernstein. “Audio creators like Tonya Mosley and Matt Katz candidly discussed how they reported and

unfurled stories of family tragedies. Local podcasters talked about sourcing, safety, and landing stories. It was a nourishing and enlightening event for podcasters, students, faculty, and everyone who attended.”

2 Stillness. Silence. Time.

Acclaimed director and theater artist Robert Wilson visited Bennington College for a 3-day residency from September 20–22, 2024. The Dance and Drama programs jointly hosted Wilson, thanks to funding from the Peter Drucker Fund for Innovation and Excellence, which allowed him to share his astonishing aesthetic universe with students, faculty, staff, and the general public.

Highlights from Wilson’s residency included an interactive lecture entitled, “1 HAVE U BEEN HERE BEFORE; 2 NO THIS IS THE FIRST TIME,” which combined striking images from moments throughout his prolific career to showcase an intimate self-portrait of his creative process.

Wilson also conducted a master class for students, who explored his manner of working and the creative process. Students focused on the foundational ingredients of motion, space, time, light, text, and sound using only simple scene design and costumes made with newspapers.

3 Your Bennington Bookshelf

Mother and Daughter Coming of Age Together

The New York Times highlighted Bruna Dantas Lobato ’15, winner of the National Book Award for translated literature, whose debut novel Blue Light Hours was published in October 2024 by Grove Atlantic. The book depicts a young Brazilian woman’s first year at a small liberal arts college in Vermont and the rituals she develops with her mother as the pair reconnect from a continent away each week on Zoom.

The Hidden Life of Ordinary Things

The saxophone is “the ‘devil’s horn,’ it’s the voice of jazz— an extension of the player’s soul—it is a character trait of U.S. Presidents, YouTube sensations, and cartoon characters,” and thanks to Mollie Hawkins MFA ’23, it is now the subject of its own book in Bloomsbury’s Object Lesson series. Saxophone blends Hawkins’s research, cultural criticism, and personal narrative to reveal a new perspective on a contradictory instrument.

Behind the Shutters

The writing of Carol Kino ’78 has appeared in The New Yorker, The Wall Street Journal, The New York Times, The Atlantic, Slate, Town & Country, and many art magazines. She has published her first book, Double Click, with Simon & Schuster. It is a nonfiction account of the McLaughlin twins, trailblazing female photographers of 1930s and ’40s New York.

A Jolting Exploration of a Broken System

In her latest book, journalist and author Claudia Rowe ’88 takes an in-depth and intimate look at the American foster care system and the way it so often fails the children it is meant to help. Wards of the State: The Long Shadow of American Foster Care, released by Abrams in May 2025, tells the story of eight former foster youth whose stories—along with accounts from psychologists, advocates, and judges—champion a need for reform in a broken $30-billion-dollar system.

“Despite the rather austere title, I’ve written [Wards of the State] to be an engrossing, character-driven look at the intimate connection between foster care and the criminal justice system,” said Rowe.

Navigating Grief and Parenting

Kirkus Reviews gave a starred review to I Will Do Better, a memoir by Charles Bock ’97 published in October 2024 by Abrams Books, praising it as “a uniquely forthright and powerful addition to the literature of fatherhood.”

Bock’s no-holds-barred memoir traces his experience raising his infant daughter Lily during and in the aftermath of his wife’s battle with leukemia. Left a single father saddled with medical bills and grief, Bock and Lily navigate their new reality together. “Single parents will find much to identify with in this warts-and-all account,” wrote Publishers Weekly.

4 Sharing a Love of Languages in Local Schools

As part of the course Teaching Languages and Cultures K-6, cotaught by faculty member Noëlle Rouxel-Cubberly and Ikuko Yoshida, Bennington students have the opportunity to share their love of languages with local children at the Village School of North Bennington (VSNB). This long-standing relationship between the schools offers myriad benefits for the VSNB students, as bilingual language learning has been linked to improved cognitive ability, problem-solving skills, and memory in children.

This year, Bennington students—including Destiny-Rose Chery ’25, Ebony Dalimunthe ’25, and Jacqueline Walsh ’26— taught Japanese, French, Indonesian, and Spanish at VSNB. Dalimunthe has worked with preschool, first-grade, and sixth-grade students at VSNB. This year, she taught Indonesian to sixth graders and was also taken by the enthusiasm students have shown in class.

“They are curious, they are caring, and in the end that is the perfect recipe for an open-minded, diligent, forward-thinking student,” said Dalimunthe.

Detail, still from Sonya Dyer, Action>Potential (2023), two-channel video. Image courtesy of the artist.

5 Experiencing the Past Anew

Queens Girl: Black in the Green Mountains, the third installment of the Queens Girl plays trilogy by Caleen Sinnette Jennings ’72, was produced at the Everyman Theatre in Baltimore from October 20 to November 17, 2024.

“While the weight of history hangs heavy overhead, Queens Girl: Black in the Green Mountains allows you to experience the past anew and through a lens so often ignored,” wrote DC Theater Arts critic Constance Beulah.

Black in the Green Mountains uses poetry, music, and dance to tell the story of Jacqueline Marie Butler, a young Black woman who arrives at Bennington College in 1968. The play was directed by Danielle A. Drakes, and all twelve characters in this one-woman show were performed by Helen Hayes Award-winning actor Deidre Staples.

6 We Have Reach

On view in Bennington College’s Usdan Gallery through April 26, We Have Reach is a visual/performance curation that considers avenues of the body in space, particularly how the Black feminine has been restricted or exploited or expelled or compelled in relationship to taking up space. This group exhibition seeks to facilitate a conversation about the Black feminine figure in relation to her exterior environment—the extent of the body across time and space, fugitive movement and fugitive stillness, exploitative fecundity, and her longing for heaven and home.

Curated by Studio AGD, We Have Reach is in dialogue with historical muses including Henrietta Lacks, Anarcha Westcott, and Sawtche (widely known as the Hottentot Venus). The curatorial group Studio AGD includes Bennington Literature faculty member Anaïs Duplan ’14, Zoe Butler, and Folasade Adesanya.

Courtesy of Theresa Castracane and Everyman Theatre

7 Dramaturgies of Care

Curator, poet, and performance artist jaamil olawale kosoko ’05 returned to Bennington for a residency in fall 2024. During this time, he taught the course Dramaturgies of Care, which he developed while teaching and performing in Europe in the fall of 2022 as a response to the lack of health, care, and safety protocols he noticed while touring live art performances internationally.

Throughout the term, the class explored how care systems— explored in art, politics, and natural processes—can serve as frameworks for both personal and collective transformation. Students engaged in interdisciplinary research and brought performance strategies, political theory, and ecological care systems together to develop creative projects that reflect how care informs not just art making but active social engagement.

While at CAPA during the Fall 2024 term, kosoko also focused on developing a new performance work “Voncena’s Spell,” which will premiere at Abrons Arts Center in June 2025.

“The experience was incredibly enriching, not only because of the dedicated students, but also due to the community I found in the CAPA environment, especially having the opportunity to reconnect with Susan Sgorbati, who was quite important to my education when I was a student here years ago,” said kosoko.

8 The Bennington Multiform

Bennington students put their personal artistry and distinct personalities at the forefront of fashion and make campus style feel more “multiform” than uniform.

Fashion has always been a creative outlet for Sawyer London ’24, who now serves as a recent alumni member of the Bennington College Board of Trustees. When he arrived at Bennington in the fall of 2020, he was impressed with fellow students’ personal style. Almost immediately, he was inspired to start an Instagram account highlighting it. He called it @BTONFITS, as in Bennington Outfits.

“My perspective wasn’t much about curating a certain look. I would ask people [if I could take their photo] whenever I saw them wearing something that stuck out—a color combination, a texture, a cow print, or whenever I saw someone who was just themselves and confident.”

Over the course of four years he requested, took, and posted 100 fashion-fabulous portraits. “Bennington is very fashionable,” said London. “And I think it creates an environment, ideally, where people feel comfortable to express themselves in that way.”

London tapped Nico Migdal ’25 to continue the project. “Sawyer has such a great eye for fashion and personal style, and he did a really great job highlighting the subtleties of that,” Migdal said. “You don’t have to be wearing a crazy extravagant outfit to get posted on @BTONFITS. He was more looking for people’s personality coming out in their outfits. I definitely want to keep that focus going.”

Share images of your best Bennington look to magazine@bennington.edu. ●

For more Bennington news, visit bennington.edu

Ten Years of Grassroots Activism

By Ashley Brenon Jowett

On a Monday afternoon in the first days of November, nearly twenty students sat around a ring of tables in a design lab in the Center for the Advancement of Public Action (CAPA). Among the topics for discussion was how to get Miguel, an undocumented worker who speaks only Spanish, translation services for a phone call with the Department of Motor Vehicles (DMV). He wanted to apply for a Vermont Driver’s Privilege Card.

The conversation unfolded in a mix of English and Spanish. A first-term GANAS student, Ananda Zamarrón ’26, raised her hand to provide translation. Another, a tutorial participant, Cyrus Vella ’26, offered to provide Zamarrón transportation to the farm where Miguel works. The process was well worn.

They hit a snag when they realized the DMV hours conflicted with Miguel’s work schedule, which includes long hours six days a week. “It’s often the DMV,” said Spanish faculty member Jonathan Pitcher with some frustration. A third of the requests they receive involve the DMV.

Pitcher was among the founding members of the group, called GANAS, “motivation to act” in Spanish, more than a decade ago. He acts as both a member and the faculty facilitator. The student-run group aims to create meaningful connections and cultural exchange with undocumented immigrants and to provide opportunities for students to support migrant workers through providing translation and English lessons. The Latino migrant worker population serves the Vermont dairy industry and other industries in Bennington County and faces constant fear of deportation, difficulty advocating for safe and equitable working conditions, and racial profiling.

THE BEGINNING

In 2011, Carlos Méndez-Dorantes, PhD ’15, Selina Petschek ’15, and Andrea Tapia ’15 had begun volunteering at the Bennington Free Clinic, a local medical practice that offers free care to those without insurance. They were missing interactions with Spanish-speaking people since having come to Bennington; Méndez-Dorantes and Tapia were among the few Latinos at Bennington during that time. And they had the urge to be useful. “I found the need to do something more practical with what I was studying,” said Tapia, who now works on the digital communications team at the World Bank in Washington, DC. “I remember being frustrated thinking, ‘I

am studying Latin America as a region, but I am in the middle of nowhere. Where are the Latin Americans?’ It was ironic.”

Méndez-Dorantes, who was undocumented while at Bennington and now works as a cancer researcher at Dana Farber Cancer Institute in Boston, noted that the clinic waiting room was one of the few places for migrant workers to meet people from other farms and connect. “Latinos were so isolated on their separate farms that a lot of the healing happening in the clinic was occurring in the waiting area,” he said. “Upon that realization, Selina and Andrea had the vision to think, ‘We can fix that. We can provide opportunities where students can teach and also learn from this community, which is very much part of the Bennington area.’”

That’s when Petschek and Tapia approached Pitcher, who had just returned from a frustrating trip to the U.S.-Mexico border with his border theory class, and asked if they could work together to offer services to migrants living nearby. Pitcher was enthusiastic. “I said yes immediately,” he remembered.

At the beginning, the founding students note, it was not always easy. “On paper, we were this sexy project for the College to talk about, but I didn’t always grasp that the institution had our back,” Petschek, who now works as a certified nurse midwife, confides. Méndez-Dorantes agrees, “Bringing migrants to campus, transporting migrant workers in college vans…there was pushback,” he said. It took a lot of advocacy with the administration and others to develop the foundation and keep it going. “I think we got a taste of what activists do and how difficult it can be to do this kind of work,” said Tapia. That the group would survive its first years, much less a decade, was not a given.

Early members of the group handed out Pitcher’s business cards to Spanish speakers at Walmart and China Wok, a local restaurant, and posted flyers on bulletin boards. With the initial people who responded to them, only two or three at first, they started a weekly soup kitchen at the Unitarian Universalist church in Bennington. Little by little, more people came. By the end of the first term, they had ten regulars. “We would just have conversations, enjoy food together, tell stories,” Pitcher said. “By the following term, we asked them what they needed. That was the true beginning of GANAS.”

THE EVOLUTION

Since 2016, GANAS has been a part of the curriculum as both a class for first-time participants and a tutorial for those with experience. In their first term in GANAS, students learn about the group and help out on projects led by those who have participated for multiple terms. They often become a primary contact for a small group of GANAS “friends,” as the migrant worker contacts are known collectively. By their second year in GANAS, students are in the tutorial, which means they lead a project of their own.

Alex López ’27, who studies Spanish and Architecture, took the class and spent two terms in the tutorial. In addition to keeping the group’s finances, organizing students to serve as primary contacts, and serving as a primary contact themself, they are often at the helm of organizing the social events. These events, which made up the core of the activity at the start, continue to be important. “Farms are isolated, miles apart, and migrants don’t have great access to transportation,” said López. “So, apart from GANAS, migrants aren’t very well connected to each other.” At the last social event, López witnessed friend attendees exchanging phone numbers. “That’s why we have social events, to connect people,” said López.

Zamarrón, along with tutorial participant Abraham Dreher ’26, is teaching friend Lupita, from Colombia, English.

“It’s an opportunity to learn new things, meet people, and practice English,” said Lupita, through a student interpreter. “I am grateful for the opportunity of being able to share my time with these students who have taken the time to teach me English. They’re very kind and very committed to what they do. I’m glad I met them.”

Jacqueline Walsh ’26, who studies politics, is the latest in a string of students who have worked with a Vermont organization called Migrant Justice to bring Milk with Dignity to local migrants. The program, run by migrant farm workers, aids dairy workers in efforts toward safe working conditions, including adequate housing, safety equipment, reasonable hours, and paid sick days. She organizes protests and call drives. “The top of the supply chain, places like Hannaford, are not willing to pay prices high enough for farmers to provide

their workers with safe housing, safety equipment, one day off a week…,” she said. She pointed out that Hannaford’s parent company made $2.98 billion in profit in 2023.

That the work is still happening much as they had envisioned it, Tapia said, “This makes me want to cry. I tear up when I see it,” she said. “It’s definitely one of the most important things I have done.” Petschek acknowledged, “It took a lot of support [to keep it going]. Ultimately, the work Jonathan Pitcher did was a constant.”

TOMORROW

Through the work of GANAS, Bennington has become the recognized leader in a consortium of nearby colleges and universities with students interested in doing this work. It has been recognized as the Southwestern Vermont Chapter of Vermont’s Migrant Justice organization and has been acknowledged with a grant from the Mellon Foundation and support from the Peter Drucker Fund for Innovation and Excellence.

Looking ahead, Pitcher would love to have migrants and farmers come to campus one night a week for language classes. He imagines a situation where the farmers would be in one room learning Spanish, while friends would be in the next room learning English. His “3-year utopian vision” is one where a connected and respected Latino community is able to advocate, socialize, and support itself without help from students and where local migrant workers, many of whom had other professional careers in their home countries, come to campus to teach in a cultural studies or social sciences series. “My dream is that [GANAS] will one day be obsolete,” Pitcher said, “that we will no longer have to do this work, any of us, ever again.” ●

Alumni who participated in GANAS are especially encouraged to reach out to Pitcher at jpitcher@bennington.edu and to attend Reunion October 3–5, 2025.

Photo by Malvika Dang

Collaborative Art Project Bridges Cultures

HOW STUDENTS AND FACULTY BROUGHT

ART TO THE U.S. CONSULATE IN CHIANG MAI

By Ashley Brenon Jowett

When the U.S. Department of State’s Office of Art in Embassies needed art for a new consulate building in Chiang Mai, Thailand, in 2019, they called on now former faculty member Jon Isherwood, Director for the Center for the Advancement of Public Action (CAPA) Susan Sgorbati, and Bennington College students to submit a proposal.

Bennington was a proven entity. Faculty and students had developed a unique and highly collaborative artmaking process, underwent a rigorous evaluation, and oversaw the successful installation of a trio of pieces for the U.S. Embassy in Oslo, Norway, in 2017.

“Because they had worked with us before, we had a track record,” said Sgorbati. “We had developed not only artworks for these public spaces but a way of creating artwork that resonates with the place where it is installed.”

The Bennington group met with U.S. State Department structural engineers at the fabrication facility in Chiang Mai on November 2, 2022 to review the voice circle prototype.

THE PROCESS

As they had for Norway, Isherwood and Sgorbati formed a class around the project, which attracted students studying an array of disciplines, including visual arts, politics, environmental action, poetry, history, dance, and others. “The most important thing was not to start with what the artwork would look like,” Isherwood said. Megan Banda ’24, a student on the project elaborated. “It started off getting us to understand, ‘what is public art? What does that mean?’ From monuments to murals to street art, we were examining the things that we encounter in public spaces and how they connect us and how they spark dialog.”

Then, Isherwood and Sgorbati directed the students to choose an aspect of Thailand’s culture—its landscape, arts, history, literature, traditions, commerce, politics, and ecological activity—and conduct thorough research. The class welcomed a steady stream of virtual guests to class, including artists and curators, diplomats, and a geographer. Students researched the history of the relationship between the United States and Thailand in an effort to identify shared values and patterns that could represent the relationship.

THE DESIGN

The next step was to translate the research into the forms, shapes, and colors that presented an idea for consideration. The focus of the Chiang Mai work was on speech. Jessica Smith ’23 studied art at Bennington and is now in her second year at Vermont Law School. “The individual right to freedom of speech is in question around the world,” she said. “The piece includes our hopes that [freedom of speech] will be restored and continue for everybody wherever they are at whatever time they need to use their voice.”

With the voice as a starting point, students experimented with translating recordings of their own voices into visual elements. They were surprised to find that each of their voices made a unique pattern. They used those patterns along with their own designs and motifs from Thai culture to create a series of six etched glass disks, each 6 feet in diameter. These translucent lenses are stacked parallel to one another along the consular walkway. The placement allows viewers to look through them or to see each one individually.

ADDING SENSES

In addition, the site provided an opportunity to create a design for the top of a low wall, 62 feet long, leading visitors up to the consulate waiting room. For this our students recorded their own voices and the voices of Thai college students studying with Karma Sirikogar at Silpakorn University International College in Bangkok, reading phrases and poetry each student developed in their own language and reflecting on their shared values.

They added imagery of resounding elements from Vermont’s and Chiang Mai’s landscapes. The two areas are remarkably similar geographically, Smith said. “Both have rivers and mountains. Both are agrarian. They have villages at the bottoms of their mountains, so we represented that in the piece.” The students’ images were designed to be translated into mosaics by วิเศษศิลป, Wises Silp, a multigenerational family of mosaic artists in Suphan, Thailand.

“We envisioned a person approaching the consulate for a visa having a calming contemplative moment as they view and run their hand along the mosaic on the top of the wall,” said Isherwood. “The idea was to create a journey that would relax and engage the people coming to the consulate.”

As they were nearing the end of the project, “four years of intense knowledge and research,” Banda said, “I just knew that people had to hear us because we have had a lot to say, and our voices…. It’s how we were connecting to each other and how we are reaching each other.” Banda and Smith, along with Tanner Criswell ’24, composed an original sound score from the voice recordings they had collected. It was a lastminute addition but one that Banda, Criswell, and Smith felt passionately about.

Consul General Lisa Buzenas commented, “I am truly grateful to the students at Bennington College for their collaboration with Thai students and artists in creating this meaningful and beautiful mosaic tile and glass voice-circle artwork that will welcome millions of visitors to the U.S. Consulate General Chiang Mai for generations to come.” She continued, “The art exemplifies the cooperation and collaboration that has been the foundation of the U.S.-Thai partnership for more than 190 years.”

The class met for three consecutive terms and extended a further 18 months for a smaller group of students, including Banda, Smith, and Criswell. Altogether, more than eighty individuals engaged on the project. Banda summarized. “We let each other’s exploration build the outcome, which speaks to the journey that we went through, from research to design to collaboration, even cross-continental collaboration with people in Thailand,” she said. “I think that’s at the heart of what we all aimed to do, to have an exchange of ideas, of people, of talents.” The opening of the Chiang Mai consulate is planned for this summer. ●

To

By Ashley Brenon Jowett

In May 1999, Berte Hirschfield ’60—who had retired to Wilson, Wyoming, near Jackson Hole—read a letter to the editor in her local newspaper. It described a multibillion-dollar U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) project to build a first-of-itskind plutonium and hazardous waste incinerator upwind in nearby Idaho. The incinerator had the potential to spew “a witch’s brew” of toxic particles into the air over her community. Moreover, it could pollute Yellowstone National Park.

“I began to realize that if we were really downwind, this was going to be very dangerous,” Hirschfield said. She deployed all of the skills she gained throughout her life— including those from her time at Bennington—to execute her personal formula for change, one that became ever clearer throughout the many projects she has worked on. Her work put an end to the incinerator project and led to a ban of nuclear and hazardous waste incineration at Department of Energy sites nationwide.

and distributed bumper stickers. The campaign caught the community’s attention.

“Here’s a woman who was retired, who had a lovely home down on Fish Creek,” said Woollen of Hirschfield. “Her children, some were in the community, some were elsewhere. She could have been doing a million different things with her time, but this is what she trained her focus on. And she got her hands dirty.”

Hirschfield’s first task was to get the facts. “[Going directly to the source] was the main thing I took away from college,” said Hirschfield. “That’s Bennington. That’s just the way it was. We read original texts.” So when she heard about the incinerator project, she consulted her doctor, Brent Blue, MD, and Gerry Spence, a friend and legendary trial lawyer known for representing the family of nuclear whistleblower Karen Silkwood. Both Blue and Spence agreed they needed to act fast. The incinerator project was shovel ready. The public comment window, which had not included Jackson Hole, was closed. “Idaho saw no reason to inform us, as we were in a neighboring state,” said Hirschfield.

Dr. Blue suggested Hirschfield contact Mary Woollen, a hospital social worker and mother who also felt called to action. Hirschfield and Woollen put together a group and started a public information campaign with the eventual aim of raising money to secure expert lawyers. They named the group Keep Yellowstone Nuclear Free (KYNF), posted flyers,

They booked Walk Festival Hall for a large community meeting. The crowd was estimated at 500 people and bridged the socioeconomic divide. It included “ski bums and service workers, members of the social elite,” reported The Christian Science Monitor. After a short presentation from the nuclear and hazardous waste experts, Spence gave a rousing speech.

Ellen Safir ’66, who is a member of the Jackson Hole community and is on Bennington College’s Board of Trustees, was there. She credits Hirschfield for building a large base of support and involving partners like Spence, who “spoke very dramatically about the topic,” said Safir. Then they asked attendees to stand and pledge support.

The response was overwhelming. The big donors were important, but people from all levels of society pitched in. “The same people who clean the homes of the rich and famous also contributed parts of their meager paychecks,” reported the Monitor. Altogether, they raised $496,000, more than $800,000 in today’s dollars, in about an hour.

Hirschfield had always been fiercely independent and “take charge.” She took responsibility for her household and two younger siblings when her mother passed away when she was just 13. At Bennington, she learned not to take no for an answer. “There was an ethic, an underlying assumption, that if you really have a passion about something, keep going.” And

fighting the DOE took every bit of her resolve. The project was one of the biggest the Department of Energy ever set out to do. There was a lot of money involved; they weren’t going to back down easily.

The DOE tried every mechanism imaginable to deflate KYNF. They opened a local public relations office. “Nobody went in,” said Hirschfield. The DOE presented what they claimed was a sophisticated fail-proof filter system, but KYNF uncovered thirty emission control system breakdowns, eight of which involved filter failures. “They were trying all sorts of ways to make it look like we didn’t know what we were talking about,” said Hirschfield.

The project had already been rejected in two other communities. KYNF wanted to put a stop to it entirely. Hirschfield said, “Not here, not anywhere.” Spence sued the government, not only to stop the project in nearby Idaho, but to find an alternative to incinerating nuclear and hazardous waste altogether.

Meanwhile, the national media got wind of the story. First, The New York Times sent a reporter. “After that, we got a lot of attention,” said Woollen, including from CNN, NPR, The Chicago Tribune, and others. Everybody got on board, said Hirschfield. “Even those in the government, the congressional delegation and the governor, who, at first, were uncomfortable with us challenging the federal government.”

While Spence, Woollen, and a new member of the group, Tom Patricelli, took a trip to New York City and Washington, DC, to visit the Council of Environmental Equality and hand deliver a letter to the Vice President of the United States Al Gore, Hirschfield connected with Roger Altman, who served in leadership of the Treasury Department under two presidents. He was able to talk with the then-secretary for the DOE Bill Richardson.

In January 2001, after more than a year of fighting, Richardson came to Jackson Hole to announce that the project would not go forward. Hirschfield invited Ellen Glaccum, the author of the “Witch’s Brew” letter to the editor, to the event. It was a celebration. They had gotten the first part of what they wanted: “not here.” And in March 2001, the lawsuit settled. The settlement led to the creation of a commission to seek alternatives to incineration of transuranic nuclear waste and hazardous material at DOE sites. The second part of their demand was resolved: “not anywhere!”

The waste was treated non-thermally and most has been shipped to the Waste Isolation Pilot Plant in New Mexico. Woollen, who had quit her hospital job to lead KYNF, started a 25-year career at the intersection of nuclear waste and the communities affected by it. And Spence, now 95, is retired from law without ever having lost a case.

Hirschfield continued work with Jackson Hole Childcare Helpers, a nonprofit she founded to help childcare programs afford equipment. She responded to needs in her own family— two of her grandchildren had been born deaf—and founded the non-profit the Pediatric Audiology Project, which brings renowned experts to conferences in Jackson to share best practices, including hearing tests for all newborns at birth. She created a lymphoma research endowment at Dana Farber Cancer Institute in honor of her husband and Dr. Arnie Freedman. And she and her husband, who cared deeply about Native American art and culture, funded the creation of the Institute of Tribal Learning at Central Wyoming College. She also served on the board of Brain Chemistry Labs, a research organization working to end Alzheimer’s, Parkinsons, and ALS, and was chair of the Jackson Hole Community Housing Trust. “I go about each thing in a similar way,” said Hirschfield, referring to her modus operandi: get the facts, gather a coalition, and don’t give up.

“It goes back to my challenges growing up, taking responsibility for my sister and brother. Bennington’s culture nurtured that independence. It’s in my DNA now because it has been the case throughout my life; if I see something that needs to be done, I don’t question if I can do it.”

“Berte is my poster woman for Bennington College,” said Safir. “In terms of her activism, in terms of her being undeterred by obstacles…. That, to me, is the kind of problem solving that I associate with the Bennington-educated woman.”

Hirschfield passed away, surrounded by her family, on January 27, 2025. An exhibit and archive of articles and videos about Keep Yellowstone Nuclear Free and its work are available at the Jackson Hole History Museum. ●

By Elizabeth Zimmer ’66 | Photography by Daniel Madoff

NE AFTERNOON last fall, eight years after my last visit to Bennington for my fiftieth reunion, I found myself on a balcony in Greenwall Auditorium, observing a series of rehearsals by students and faculty of a newly blended dance program, called Dance Lab, that weeks earlier had incorporated thirty-six students and a number of faculty members from Philadelphia’s University of the Arts (UArts).

Down on the main floor, Jesse Zaritt, a Brooklynbased dance artist, led a run-through of Dance Lab choreographer Sidra Bell’s latest work for the students. Then Cameron Childs, teacher/administrator with the BFA program, saw another group through a balletic piece by Gary W. Jeter II, a UArts MFA graduate now on the faculty of the same Dance Lab. Both pieces and others were part of a concert shown at Bennington and then again in Philadelphia in December. The rehearsals I saw evidenced a kind of highly technical, expressive dancing notably different from Bennington’s dance program, which is generally more experimental, personal, and improvisational. Around me on that balcony were several students waiting their turn to perform, a couple of others nursing injuries, and Donna Faye Burchfield, developer of the beloved UArts dance program.

Burchfield, whose students call her “DFaye,” was the longtime dean of the American Dance Festival, which began life at Bennington in 1934. She had been the Dean of Dance at UArts for 14 years when she received a disconcerting message: her workplace was closing down in a week. An arts educator with more than 40 years’ experience, she swung into action.

A compact dynamo with a graying braid and a brisk, engaging manner, Burchfield is a native of Georgia who trained at Texas Christian University in Fort Worth and received BFA and MFA degrees before joining the administrative staff of the American Dance Festival in 1984. Founded by Martha Hill at Bennington when the college itself was only two years old, ADF has been the spine of modern dance training in the United States for nearly a century and exposes students and teachers from across the country to the latest and best developments in the art form for six weeks every summer. The festival migrated from Bennington to Connecticut College in New London in 1948, and then to Durham, North Carolina, in 1978. Burchfield became dean at ADF in 2000, only the third person to hold the position, succeeding the late Martha Myers; in 2003 she also began directing the MFA program at Hollins University in Roanoke, Virginia, after having

been teaching there since 1993, simultaneously with her administrative and teaching duties at ADF.

When an educational institution fails—goes bankrupt, closes down without warning—lives are disrupted. Faculty and staff members lose their jobs. Entering students have to make other plans. Matriculated students must, as well. UArts shut its doors on June 7, 2024, a few days after announcing its financial difficulties. It has since filed for bankruptcy liquidation. The school, which grew over about 150 years through the mergers of various visual arts and musical academies with a dance school and eventually a theater department, attained university status in 1987, and was a training ground for many luminaries in music and art. Its dance program, originally known as the Philadelphia Dance Academy, produced Judith Jamison, Alvin Ailey’s muse and later the director of his company, who died last fall at 81.

Dean Burchfield was understandably frantic; her thirty-one MFA students were holding airline tickets and about to depart for their summer term in Montpellier, France. She had dozens of undergraduates expecting to continue their training at the Philadelphia institution and newly admitted students knocking at the door. Laura Walker, the president of Bennington, and Provost Maurice Hall sprang to her aid, urged, said Provost Hall, by two UArts deans who “have kids here at Bennington.”

“The UArts dance program’s mission, rooted in the liberal arts, matches Bennington’s values,” said Hall. “It’s a wonderful complement, dare I say marriage, both the BFA and the LowResidency MFA.” The UArts dance division was the only one of the University’s programs to be “adopted” in quite this way.

The Bennington dance faculty and the Philly teachers were deeply familiar with one another’s work, which smoothed the way for the new alliance. “Within the first day, I got emails from my faculty asking, ‘Can we help?’” said Walker. “Our enrollment is the highest it’s ever been, but we had space for around thirty-seven students. And we’re delighted that it’s a really diverse group from countries around the world.”

Dana Reitz, choreographer, dancer, and visual artist, has taught at Bennington for 30 years. “We were asked by Laura [Walker] and Maurice [Hall] if we were OK with them joining us in some way, in our spaces, with a very different agenda and different needs. There was a very intensive technical schedule that they wanted to keep… We respect the journey and the agony and everything they went through.”

A hastily assembled task force managed, in a week, to raise $1 million to underwrite the MFA program’s mission to Montpellier and other expenses involved in transplanting thirtysix UArts undergraduates, their teachers, and a few staffers from Philly to Bennington. Sebastian Scripps, the son of Louise Scripps who, with her husband Samuel, had been a longtime benefactor of the American Dance Festival, came through with most of the necessary funds; other contributions came from the Ford Foundation and the Transformational Partnerships Fund.

Nate Tantral-Johnson ’26, a 19-year-old student from Stratford, Connecticut, had been at UArts for one year when the news broke. “I really don’t know what I would have done without Bennington. I was preparing to travel to France as a research assistant with the School of Dance MFA program, and all of a sudden, I had to look into transferring schools or taking a gap year, neither of which seemed like the right option.”

He continued, “The program that DFaye cultivated [is] like nothing else. She’s teaching us to tune our attention, priming us as critical thinkers, encouraging us to engage with art in a special and unique way. I couldn’t just go back home to Connecticut after being in that world. It would be like closing my eyes. I’ve joked about how I would be willing to follow her halfway around the world, but in some part, that’s true. And now I’ve followed her to Vermont. I think what we’ve been able to build here is incredible. The way we think about education and community has been totally recontextualised. It’s such a fragile thing, and that means you have to hold each other tighter. The other students have kept me grounded. There’s so much support.”

Cat Bauermann ’25, a native of Baltimore now in the final term of their BFA degree, chose UArts because of its hip-hop offerings. They “felt completely lost” when the closure was announced and fought hard to keep the UArts program alive in Philly by writing dozens of letters to politicians and others on social media. “If it hadn’t been available to continue DFaye’s program,” they observed, they would probably have left school and headed to a metropolitan area where they could continue

“Te BA students study a working alongside them has

The arrival of the former UArts students and faculty on the Bennington campus is not, Burchfield hastened to say, “program acquisition.” “We’re developing a new experimental, likely mobile, BFA program.” As many as fourteen members of her full-time UArts faculty have taken part-time work, paid by the course, in order to join her in Vermont. They are continuing the developing relationships they have with the students and their creative and technical efforts.

Bennington’s financial aid office “matched or beat the aid students had at UArts,” said Provost Hall. The dance students, a lively, energetic, and diverse community whose previous training was in some ways closer to the conservatory emphasis of a place like Juilliard than to the free-ranging, experimental model in use at Bennington, appear to be having a wonderful time. Five newcomers enrolled directly into the College’s BA program.

performing, in New York or Los Angeles or Amsterdam; “I would continue my education in the ‘real world,’” which would be their classroom instead. They are trying “not to calculate, but to follow my heart.” Bauermann is thrilled that Philadelphia hip-hop leader Kyle Clark is teaching at Bennington now. “I’m in Kyle’s POD (Performance Pedagogies),” a series of intensive weekends that enable students to continue their engagement with hip-hop in Vermont. They are delighted with the similarity between “the moral compass at UArts and at Bennington” and glad to have access to “places like ‘the Cave’ in VAPA, with new resources and new tools” that feed their special interest in making dance films.

Three of the UArts students enrolled in Reitz’s multidisciplinary Collaboration in Light, Movement, and Clothes,

milliondiferent things;

made me

reorientmy

CAT BAUERMANN ’25

taught with designers Michael Giannitti and Tilly Grimes last fall. Bauermann said of that class, “the BA students study a million different things; working alongside them has made me reorient my perspective. What they see in a dance work, versus what I see, has shed a light on different ways of making things. It’s been incredible to experience how someone sees my work because that person is a sculptor.”

What does the future hold for Bennington’s newest dance program? Walker said, “We’re figuring it out. We’re learning from having Donna Faye and the BFA in Dance students and faculty on campus. We could move [the program] back to a center in Philadelphia, with a cultural institution [there] as partner. We want to be a little out of the box. What could a mobile dance campus look like, embedded in Philadelphia? It will be experimental in several ways.” ●

Donna Faye Burchfield (top) and President Laura Walker in VAPA.

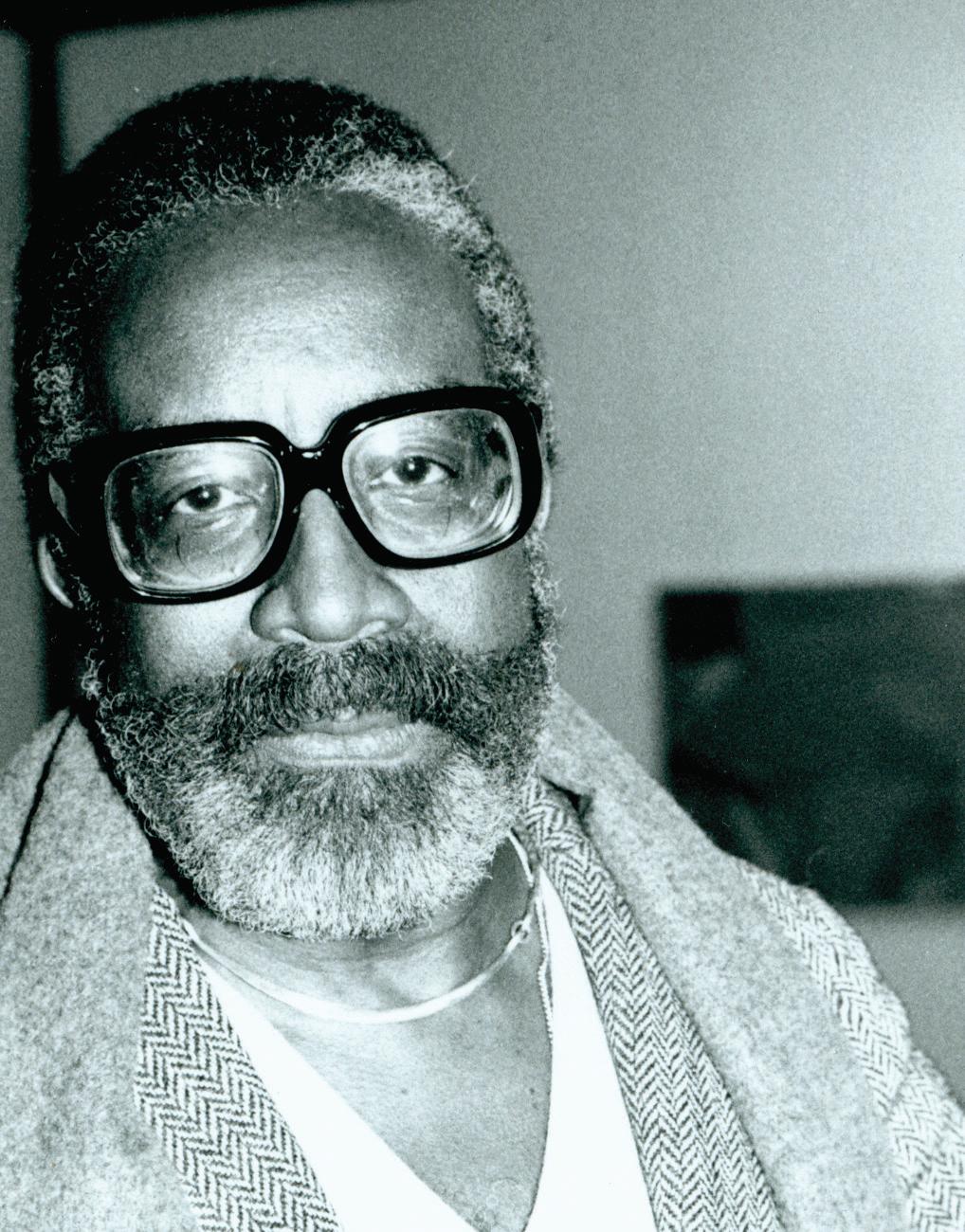

The Legacy of Bill Dixon & the Black Mu ic Divi ion

By

O. Edwin Ozoma

Black Music is legacy. You hear it every day. You hear it in music that you didn’t know was Black, that you hadn’t considered sprang from Blackness.

It’s easy to hear in Robin Thicke, Amy Winehouse, and Bobby Caldwell. You might even recognize it in Michael Franks, George Michael, and No Doubt. It’s even there in Daft Punk’s house music and disco, Black Sabbath’s rock and roll, and Billie Eilish’s sample-bopping rhythmic ballads. It’s not hard to argue Black Music’s legacy and impact on the greater cultural landscape in a post-Prince, post-Michael Jackson world that awarded Kendrick Lamar a Pulitzer Prize and has Lupe Fiasco teaching at MIT. Praised by the white masses and even accepted by their academy, in 2025 there is no argument that Black Music is king. In 1974, in the era of funk, disco, R&B, soul, jazz, and the blues, it wasn’t such an easy argument.

Bill Dixon, a trumpet virtuoso, came to Bennington College in 1968 with dancer Judith Dunn. Dixon played, Dunn danced, and the students were awed, previously unaware that people were allowed to move, to play, to present the way they did. They were radical, engaged, and charismatic. Bill brought his ideas about Black Music and its position in the greater landscape and the academy with him.

Dixon noted that western music was celebrated, lauded, and praised as the default. He wanted to create a program that celebrated Black Music. He successfully created a curriculum under Black Studies, but he wanted more. He wanted an entire Division—a department—dedicated to Black Music. He wasn’t without opposition.

Most of the music faculty at the time argued that there was no such thing as Black Music, and if there had been, they could not teach it because they didn’t know what it was, Dixon wrote in the 1974 document called “Statement of Intents and Purposes with Regard to Being a Division Among Divisions.”

He continued that by the music department’s assessment, not only was there no such thing as Black Music, but there was no such thing as a Black Musician either, despite having a few of them as colleagues, as if a field of study or its practitioners could not exist without the approval of the faculty at an academic institute. If that was how the music division felt, then “there [was] no room for experimentation, new thought or ideas or implementation of those ideas within the single music

division makeup,” Dixon said in his Statement. “So things have to be separate,” he continued.

Dixon was born in 1925 on Nantucket Island in Massachusetts. During the Great Depression he moved to Harlem with his family where he attended high school. As a student there, Dixon played the trumpet and started to paint— creative endeavors that would stay with him for the rest of his life. In 1944 he went off to serve with the U.S. Army in Germany during WWII. He returned in 1946 and attended the Hartnett Conservatory of Music until 1951. In the fifties Dixon worked with the United Nations and founded the UN Jazz society. By the time he made it to Bennington, Dixon had been working to legitimize Black Music in the larger culture for years.

Dixon was aware of the musician’s struggle, and the pull between making art and making a living. “The young musician coming up doesn’t have the strength, tenacity, or even willpower to resist the overtures of commercialism that are laid on you to survive,” Dixon stated about Black musicians in an interview in 1975. “The only way for it to survive would be if the universities and colleges in this country are going to survive, then this should be a part of the curriculum.” Dixon had been teaching for years by this point, but it was still no wonder that he had worked so hard to create the Black Music Division. To preserve the artist, to preserve the art of Black Music, Dixon suggested you find the artists and you “make this person a real teacher, and you turn the person loose in what the person’s doing.”

Dixon was a force who believed in improvisation, “live composition without notation.” He composed on the fly for the audience and the piece that was being played in the moment. It was a sort of interactive composition that took the environment into account. And that innovation added to the conversation in a way that changed the musical landscape. In this sense, through his work as an educator who inspired students and broadened their views of Black Music, as someone who emphasized improvisation the way he did, Dixon was certainly an innovator.

It is worth noting that Bennington College is a private liberal arts college in Vermont: not exactly a hub of Black activity, or an oft-sought home for Black students. So why a Black Music Division there? How many Black Students would Dixon reach with his division at a predominantly white institution, or PWI? Frankly, these are fool questions. Bennington is an institution that takes itself and art seriously, and not focusing at all on Black Music would be a misstep. Besides, why not? The students certainly responded well to the Black Music Division. Dixon himself knew that he wasn’t teaching a ton of Black students, certainly not more than he’d teach at a university in a more integrated city, or at an Historically Black College or University. Dixon was also aware that Black Music wasn’t solely consumed by Black people, that it was an integral part of American music culture, and that teaching it would inspire and change the way new nonblack musicians created and the way students who weren’t musicians would engage with the art and the culture.

Below: Dixon teaches his aesthetics class, 1973; Left: Dixon conducts his advanced ensemble in concert at Great Meadow Correctional Facility in Comstock, N.Y., November 1973.

An early course, Aesthetics as They Relate to Black Music, was primarily for non-musicians and contained readings by music critics, liner notes, record reviews, and album listenings. It wasn’t so much about creating Black Music but understanding it and its culture, and the culture that it came from. Dixon believed that it was impossible to teach all of Black Music. The art was too vast, too varied to cover everything. But he did believe that there was a Black aesthetic he could teach students to recognize. He stated in an interview that, “the Black aesthetic is one that has arisen out of the very nature [of] how Black people came to this country, how they were

treated in this country, and how they are still treated in this country. Which is to force them to take everything that is around them and metamorphosize it into something that makes sense for them.” The class was a cultural and sociological study through music. It was accessible to non-musicians and, though it was an advanced course, it accepted anyone who chose to enroll. The class was truly a celebration of Black Music.

Clearly Dixon got his division. It included faculty members Arthur Brooks from 1975–1995 and Milford Graves from 1975–2012. The Black Music Division ran for 10 years, from 1974 to 1984. After that, the courses were listed under Music, and much of the faculty remained. Dixon himself taught at Bennington until 1995. He fought to create a legacy at Bennington, and he won. He brought along a powerhouse staff, designed a curriculum, and implanted Black Music in academia. Dixon died in 2010, but not before he left Bennington College changed.

In spirit, and in course offerings, The Black Music Division lives on at Bennington. Michael Wimberly teaches several courses in the spirit of the Black Music Division and is leading a Black Music Symposium March 21–22. While there was a strong focus on jazz to begin with (though jazz was certainly not the only music covered by the Black Music Division), Wimberly’s courses reimagine what the Black Music Division would look like

now and cover the culture and artists who are making contemporary Black Music. He says that the focus is on serious artists, not the lighter pop artists, but there’s certainly a wide range of Black artists covered in Wimberly’s courses now. They include Thelonious Monk, Sun Ra, Max Roach, Nina Simone, and Jimi Hendrix but also Parliament Funkadelic, Beyoncé, Public Enemy, Childish Gambino, Kendrick Lamar, and others. And like the Division in Dixon’s time, Wimberly invites a rotating cast of Black artists to the school to present, perform, and engage the student body.

Now, at universities all over the country, all over the world, jazz is

recognized by the academy at large as a serious and even formal music of study. It would be preposterous to assume that Bennington’s Black Music Division alone is responsible for that change in perspective in academia, but it is reasonable to say that, at the very least, Bennington was not left in the past when it came to recognizing Black Music. It would be reasonable still to say that Bennington’s Black Music Division helped, in a small way, contribute to jazz being legitimized and Black Culture being recognized as a field of study. Even today, in a time when Lupe Fiasco is teaching hip-hop at MIT and “Outkast and the Rise of the Hip-Hop South” was taught at Armstrong State University in Savannah, Georgia, Bennington won’t be left behind. It holds onto and celebrates its legacy and continues to offer Black Music courses.

The Black Music Division is a hell of a legacy to leave. Dixon himself said, “I like to think that when I die, I’ve left something.” ●

The Bill Dixon Ensemble, from left: Milford Graves, Stephen Horenstein, Bill Dixon, Henry Letcher, Susan Feiner, Jay Ash, Sidney Smart, and Arthur Brooks.

THE OUTSIZED ROLE OF THE PURPLE CARROT FARM

By Ben Hewitt

In the United States, the average farm comprises 464 acres, and the USDA defines a “small farm” as comprising 179 acres or less. According to this definition, Bennington College’s Purple Carrot Farm, which consists of a single acre, is small even by small farm standards. One might call it a mini farm, or maybe a tiny farm, or even a micro farm.

Yet none of these definitions would account for the ripples that extend outward from the Purple Carrot Farm into the many communities it touches daily. There are the students who tend it, turning soil, sowing seeds, harvesting crops; there are the chefs who transform its bounty into nourishing meals that feed hundreds daily; there is the broader Bennington community who benefits from the farm’s

partnership with the Bennington Fair Food Initiative. If one considers these ripples, and how they often reverberate across the decades after a student graduates and impact lives far beyond the greater Bennington College community, then perhaps that humble one-acre farm isn’t so humble after all. Perhaps the measure of its physical size is just one way to understand its influence and not such an accurate way at that.

Lilly Kelly ’25 is just one of the many Bennington students whose life has been profoundly impacted by that single acre. Kelly came to Bennington as a freshman, with a keen interest in farming already instilled in her. She began working on the farm immediately, knowing how important it was for her health and happiness to remain engaged in agriculture, which

had become a passion for her during the COVID-19 pandemic. What she didn’t yet realize was how much more the farm had to offer. “The farm has been one of the most important educational experiences I’ve ever had,” she explained. “It’s been really interesting to realize that I’m not just a sponge for knowledge; I’m actually someone who can spread knowledge. I have something to share with others.”

Still, for Kelly, perhaps the greatest lesson of the farm is rooted in the connections it fosters. “Farming and food is one of the easiest, most natural connectors between people. There is something that feels uniquely loving and important in the act of growing and sharing food.”

Kelly’s experience at Purple Carrot is exactly what staff member Kelie Bowman had in mind when she partnered with the College in 2021 to revitalize the farm and expand the food and agriculture studies opportunities. It was a natural fit for both Bowman, a self-professed “obsessive gardener,” and the College, the alma mater of best-selling author Michael Pollan ’76, whose books include The Omnivore’s Dilemma, In Defense of Food, and Food Rules. Long an advocate for regionalized food systems and regenerative farming methods, Pollan is widely credited for popularizing the local food movement.

Much like Pollan and the students who work the farm, Bowman believes fervently in the power of small-scale regenerative food production. Regenerative farming leverages a variety of techniques and technologies to produce nutrient-rich crops while always returning more to the soil than it takes, even as it supports the physical, economic, and social health of the communities it impacts. Increasingly, its proponents point to regenerative farming’s capacity to mitigate climate change through the rapid creation of top soil, which acts as a carbon sink. “Farming has such a direct impact on the land and community,” said Bowman, an established artist and

gallery owner who came to Bennington when her partner took a job at the College. “I’ve come to think of it as my new social service work.”

Part of Bowman’s work involves deepening and broadening the College’s food and ag-related opportunities to deliver a greater emphasis on sustainable farming methodologies while also ensuring that students have ample chances to put these methods into practice. According to Bowman, this approach serves the students in several ways: first, by giving them the hands-on experience they need to experiment with and truly understand regenerative practices such as no-till soil management and Hügelkultur, a horticultural technique that involves planting into mounds of organic biomass for improved soil fertility and heat retention. And second, by offering them the opportunity to connect directly with

the very source of their sustenance.

“The cool thing about growing food is that it’s very tangible,” said Bowman. “It offers a way to measure value that’s not connected to money, and I think that’s really important.”

There’s also the fact that farming takes place outdoors and requires physical effort, often in the company of others, a combination that’s particularly beneficial in the cerebral environment of higher education, to say nothing of the myriad life stressors we all navigate.

“I’ve really noticed how some of the students have come to rely on the farm for their mental health,” said Bowman. “It’s incredibly therapeutic.”

This observation is mirrored by Lilly Kelly’s lived experience. “It tends to get pretty brainy around here,” she said with a laugh. “I was feeling a little lost without anything to do with my hands, and the farm has really helped

“The farm has been one of the most important educational experiences I’ve ever had.”

LILLY KELLY ’25

ground me. It’s had such a positive influence on my learning beyond the farm.”

The positive influence of the farm extends in many directions, including the College Dining Hall, where Chef Matthew Daigneault transforms its seasonal abundance into nourishing meals that feed hundreds of students and faculty daily. In 2024, the farm provided over 5,000 pounds of produce to the school kitchen, up from 1,500 pounds the year prior. Chef Daigneault’s appreciation for the farm is rooted first and foremost in his commitment to using the freshest, highest quality produce possible, and also in its ability to provide him with ingredients he simply can’t source elsewhere. “I love and adore and get a little crazy about using all the tomatoes before they ever see the inside of a refrigerator. I want them to go through as few hands as possible before they land in mine,” he said. “And I love how the farm makes me a more creative chef. My other purveyors only sell what they already know, which tends to pigeonhole you into using certain things.”

Perhaps the biggest challenge inherent to Chef Daigneault’s relationship with the farm is the sheer abundance and variety of food it produces during the peak harvest months of September and October. Here, too, he relies on his creativity to make the most of the boxes upon boxes of produce finding their way to his kitchen. According to Chef Daigneault, there’s a fringe benefit to his creative thinking and meal planning that might just be as important as the food itself: it engages the students. “The more I use food from the farm, the more kids get involved and talk about it with other students, which leads to more students getting involved.”

It’s a fitting dynamic for a piece of land with a long history of feeding its immediate community, first as a part of the original 140-acre piece of farmland donated by Fredric and Laura Jennings that became Bennington College and later as a victory farm during World War II, comprising 100 acres.

For many years following the war, the farm lay fallow but was resurrected again in the ’90s under a Community Supported Agriculture (CSA) model, which sold farm “shares” to the community in exchange for produce. The College hoped to make the farm financially self-sustaining while also engaging the student body in its operations. The CSA program met with limited success, and by the year 2000, it was winding down.

In 2011, two College students— Sofie Sherman-Burton ’13 and Bryan Markhart ’13—petitioned the College to commit an acre of land to a permanent student garden, and this became the Purple Carrot Farm. “In our first year, we had a kids’ camp that would come by the farm and help out,” recalled Sherman-Burton. “We had planted purple carrots, and one of the campers didn’t believe there was such a thing. Even when we harvested and he saw they were actually purple, I’m pretty sure he thought we’d painted them somehow.”

The purple carrots were real, and so was the energy coalescing around the farm, which quickly became a focal point for the student body. At one farm meeting in 2012, more than 100 students, one-sixth of the student body, showed up. “The energy around it was huge,” said Sherman-Burton. “People felt like they were part of something big and had an opportunity to shape things in a positive way. I think that was really alluring.”

It’s exactly that opportunity that excites Kelie Bowman. “More and more, I see the farm as a community space for people to gather. It’s not merely about physical nourishment anymore; it’s about nourishment of the soul too.” ●

This just in: NSF Awards $1.8 Million to Bennington

In January, the National Science Foundation awarded $1.8 million to Bennington College as a part of an $8 million Science and Technology Research Initiative for the Vermont Economy (STRIVE). Under the direction of David Bond, Associate Director of CAPA, this grant includes an array of new analytical equipment for the sciences, two new positions, and support toward a timber-framed barn to reintroduce sheep and chickens to the campus. Building on the foundation CAPA Director Susan Sgorbati started with a $1 million grant from the Mellon Foundation for local food security work and food studies courses in 2019 and as a part of the $2 million Bennington Fair Food Initiative in 2022, this award will create a laboratory for locally focused sustainability studies.

“The campus farm was founded in the forties as a homefront in the fight against fascism,” said Bond. “Support from NSF will help us sharpen that legacy for the ecological and economic challenges we face in southern Vermont today.”

Alumni with memories of the campus farm, insights from their own work in agriculture and food issues, and those simply interested in learning more about exciting work on the campus farm, contact magazine@bennington.edu.

SELF STARTERS

BENNINGTON ALUMNI MAKE THE LIVES THEY WANT AND PLACES FOR OTHERS

Bennington Magazine spoke with four alumni who have started radically different projects: a shop, a forest cemetery, a nonprofit writers residency, and an augmented reality gaming company. Despite their differences, each has used deeply personal motivation marked by creativity, uncertainty, and the joy of the work.

By Ashley Brenon Jowett

BRIANA MAGNIFICO ’08

W. COLLECTIVE

Since high school, Bennington native Briana Magnifico ’08 has always wanted to have a shop, specifically one that sold both beautiful pastries and handcrafted items she made herself. She cofounded and owns W. Collective on North Street in Bennington. “It is my dream realized,” she said during a recent visit. “I always knew that I was meant to be a business owner.”

At Bennington, she studied costume and fashion design, photography, acting, and voice. She was able to get a job straight after graduation working as a costume production assistant for Taking Woodstock, directed by Ang Lee. From there, she worked for fashion designer Adam Selman and assisted him and his brand with all of Rhianna’s tours and red carpet looks, most notably the nude Swarovski crystal dress she wore for the Council of Fashion Designers of America Fashion Icon of the Year award show. “Bennington College gave me so much. It was unlike anything else,” she said. “I miss it, and I dream of it often.”

All along, while working other jobs, she designed and made things—candles, original clothing, and napkins and placemats dyed with natural pigments—and curated antiques and vintage clothing to take to markets.

Now, in the spacious, artistically appointed space at W. Collective, Magnifico sells handcrafted items made by women artisans, including herself. Items are chosen for their beauty and sustainability. Between the work of operating the shop, she makes screen-printed clothing, candles, a string of pennants made of recycled denim—And she stages them.

“I have an idea in my mind, and I am a perfectionist. I sacrifice a lot to reach my vision,” she said, pointing to a pink light illuminating a 5-foot grapevine wreath studded with dried hydrangeas. “It had to be pink,” she explained.

True to her high-school daydream, Magnifico also sells coffee and espresso drinks and pastries from local women-owned bakeries and those she bakes herself. The shop is the only local purveyor of natural wine. “It just tastes better, and it’s better for the environment,” she said.

“It’s important to have a place like this in my hometown, to have that sense of community and to feel a little bit better every time you leave,” she said. “I hope people can come in and feel inspired and make the world more beautiful for ourselves and for each other.”

Photo by Jamie Magnifico

MICHELLE HOGLE

ACCIAVATTI ’05

THE VERMONT FOREST CEMETERY

Photo by Glenn Russell

As a student at Bennington College, Michelle Hogle Acciavatti ’05, who now lives in Montpelier, Vermont, studied human development and the brain. “Bennington allowed me to pursue that as a science exploration and a philosophy exploration and to look at neuroscience through writing and not to give up my love of singing,” she said. “I went to Bennington because I never understood that you had to fit into one box to do anything.”

But just a few months before graduation, her class suffered deep trauma. There were three student deaths all within five months: Adam Mills ’05, Kelly Muzzi ’06, and Elissa Sullivan ’05. She thought of them throughout Commencement. “The people at the podium were saying that we could do anything we wanted.” At the same time, she recognized that lives end, sometimes abruptly.

She carried the thoughts of her friends with her as she entered graduate school for neuroscience at Boston University and, later, as she worked as a research consultant in the Office of Ethics at Boston Children’s Hospital. She saw parents and families go through what she describes as the worst possible situation, the death of a child. Despite having access to the most extensive medical and support resources available she remembered thinking, “these parents need more than what exists. There is a piece missing.”

That’s when she began to ask, how do we support people through the dying process? “That has been the driving question for me throughout my work.” She trained as a hospice volunteer, then a home funeral guide and an end-of-life doula, not long after the term itself was coined. Acciavatti racked up many end-of-life credentials by the time she started Ending Well, a for-profit company, in 2016. (She rebranded it as Green Mountain Funeral Services in 2023.) Her aim was to help people understand what their options were and how to access them.

The more conversations she had, the more she came to understand people’s needs and fears. She heard people say, I want to go back to nature. I want to do something good with

my body when I die. “These are people who drive electric cars and eat organic food. They don’t want their bodies stuffed with chemicals or contributing to the carbon load in the atmosphere,” she said. She and many others she encountered wanted to be buried naturally in a forest. Only natural burial— placing a deceased person’s remains directly into the earth without embalming, a casket, or a burial vault—was not legal at the time. “The missing piece kept getting bigger,” she said.

In 2016, Acciavatti led a campaign, successful in 2017, to legalize natural burial in Vermont and began steps to create a forest cemetery on more than fifty acres in Roxbury, Vermont. It’s called the Vermont Forest Cemetery. Looking back, she recognizes, “It’s not so much about creating the cemetery. I am really attempting to create a system that changes the way people in Vermont engage with the end of life,” she said. “How do we connect people with how they want to die? It means connecting with how we live and with our values.”

The cemetery has five areas of interest. In addition to burial, they also work on conservation, art, learning, and community. “We want people to come into relationship with this land. If you are going to sustain it with your body when you die, what can it offer when you are still alive?” There are a lot of ways people are interested in engaging, she said. Conservationists are interested in the land’s tree and bird populations and how to turn forests into natural sponges to alleviate flooding, while historians are considering the land’s precolonial and colonial inhabitants. “It’s not even about death and dying; it’s about making this place meaningful to them in life.”

Acciavatti considers herself as much a storyteller as a deathworker. “People’s stories… have been tremendously enriching to me.” When people visit the cemetery, she gives them tours and shares the stories of the people buried there. “One of the things that we have tried to do at the cemetery is make sure that people’s stories become as much a part of the ecosystem as their bodies do.” She is working with a documentary filmmaker to offer 15-minute documentaries to the families of each of the the twenty-three people buried in the cemetery so far. An interactive map will allow visitors to read about, see photos, or watch a short film about the people who Acciavatti describes as literally sustaining the forest.

“For me, it is all about love. How do we love the world and how do we love the people that we bury and how do we continue to love the people who come in the future? Who we are is how we love.” For more information, visit cemetery.eco

V Hansmann MFA ’11’s 30-year career in finance ended abruptly when the company he worked for closed in 2008. He said, “If I never see another annual report in my life it will be too soon.” His retirement lasted just six months. “I was at risk of becoming that gay man who had seen everything on and off Broadway and could talk at length about it, and I did not want to be that person.” So he applied to the Bennington Writing Seminars and became, he said, “the English major I always intended to be.” His favorite part of the master’s of fine arts in writing was the residencies, ten days in January and June, especially the company. He said, “I loved being with smart people who are interested in making better sentences.”

When graduation came in June 2011, he didn’t want the program to end. He had heard poet Donald Hall say, “The friendship of writers is the history of literature,” and he took it to heart. Thinking of ways he could replicate the residency experience, he went back to New York City and started a monthly reading series that ran for 10 years. While the series expanded his literary circle in New York and achieved great success, he said, “What I really wanted was to build something.”