SUDDENLY A WOMAN SPECTATOR

My shift in spectatorship came very suddenly and specifically out of the influence of the women’s movement, so that was suddenly watching films

EDITORIAL DESIGN : LOOK Print WOMEN’S INDEPENDENT FILM ISSUE NO.1 WINTER 2019 Nia DeCosta’s ‘Little Woods’: The Female-Led Neo-Western PG.6 24 28 RUNGANO NYONI'S AM NOT A WITCH WHERE WE ARE IS HERE Nyoni’s provocative satire revolves around young girl sentenced to life imprisonment state run witch camp. Avant-garde women’s cinema showed that women were active in the Hollywood big leagues as well as the indie margins. 03 06 14 20 FROM STAR TO DIRECTOR TOUCH AND ITS HESITATIONS SUDDENLY A WOMAN SPECTATOR JEANNE MOREAU AND MARGUERITE DURAS: Between 1953 and 1962, Tanaka directed six films, making her the first woman Japan to have career as film director. Mulvey coined the term ‘male gaze’ and tackled the inequality at the heart cinema — the centrality of the male viewer. this representation of an aging, alcoholic genius Jeanne Moreau plays Duras the story of her incipient affair with her much younger fan, lover, collaborator, and carer, Yann Andréa. Enyedi unravels series contrasts and more formal than metaphysical, these contrasts mediate the film’s affective exploration of touch — its hesitations well as its limit-points. 2 CONTENTS Look at Kinuyo Tanaka’s Directorial Debut An Interview with Laura Mulvey On Film, Love and Female Friendship In Ildiko Enyedi’s ‘On Body and Soul’ On the Influence of Female Filmakers Accusations and Tourism in Zambia ISSUE 01 WINTER 2019 Suddenly A Woman Spectator 6 7 Suddenly A Woman Spectator My shift in spectatorship came very suddenly and specifically out of the influence of the women’s movement, so that was suddenly watching films that I’d loved and films that had moved me with different eyes. “ “ Laura Mulvey (b. 1941) is best known for the groundbreaking essay Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema (1973, published 1975) in which she coined the term ‘male gaze’ and tackled the asymmetry at the heart of cinema — the centrality of the male viewer and his pleasure. The ideas developed throughout her long career as both film theorist and filmmaker have cast long shadow, continuing to influence a host of other thinkers and makers, many of whom appear in this journal. Currentl, she professor of film and media studies at Birkbeck, University of London. Could you start by telling me a little about what was latterly termed your ‘cinephile period’, before your involvement in the theorising of and making of films? was born in 1941 and lived the countryside for the whole of the war so didn’t see any films until came back to London at the age of six. Because of this, remember the first films ever saw quite clearly. think the first was Nanook of the North (Robert Flaherty, 1922), because my father was from the far North of Canada and was interested in Inuit culture. The other films that stand out very vividly for me, from the early fifties, are Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger’s The Red Shoes (1948) and Jean Renoir’s The River (1951). sometimes think that it’s because didn’t see many films in my childhood that these two films are indelibly marked on my cinematic unconscious. My genuinely cinephile days started when left university and started going to the cinema with group of friends, including Peter Wollen. These friends were all influenced by the Cahiers du Cinéma, so that marked shift into an adoration SUDDENLY A WOMAN SPECTATOR AN INTERVIEW WITH LAURA MULVEY BY ANOTHER GAZE 08.15.2018 Illustration by Natalie Briscoe Desktop Web Mobile Web

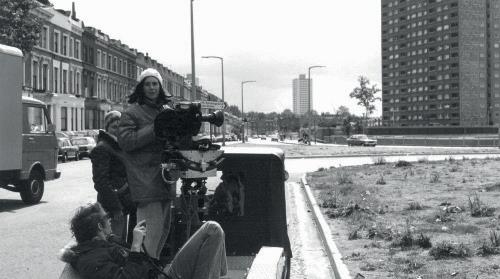

AN INTERVIEW WITH LAURA MULVEY BY ANOTHER GAZE 08.15.2018 Laura Mulvey (b. 1941) is best known for the groundbreaking essay Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema (1973, published 1975) in which she coined the term ‘male gaze’ and tackled the asymmetry at the heart of cinema – the centrality of the male viewer and his pleasure. The ideas developed throughout her long career as both film theorist and filmmaker have cast long shadow, continuing to influence host of other thinkers and makers, many of whom appear in this journal. At present, she is professor of film and media studies at Birkbeck, University of London. Could you start by telling me little about what was latterly termed your ‘cinephile period’, before your involvement in the theorising of and making of films? was born in 1941 and lived in the countryside for the whole of the war so didn’t see any films until came back to London at the age of six. Because of this, remember the first films ever saw quite clearly. think the first was Nanook of the North (Robert J. Flaherty, 1922), because my father was from the far North of Canada and was interested in Inuit culture. The other films that stand out very vividly for me, from the early fifties, are Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger’s The Red Shoes (1948) and Jean Renoir’s The River (1951). sometimes think that it’s because didn’t see many films in my childhood that these two films are indelibly marked on my cinematic unconscious. My genuinely cinephile days started when left university and started going to the cinema with group of friends, including Peter Wollen. These friends were all influenced by the Cahiers du Cinéma, so that marked a shift into an adoration of Hollywood, and of those directors that the Cahiers had sanctified as part of the ‘politique des auteurs’. That took up great deal of my time in the

to see films that weren’t so current but

fallen out of currency, and the National Film

show retrospectives,

the

SUBSCRIBE FOLLOW GO

sixties…Going

hadn’t

Theatre was beginning to

and we were going to Paris,

Cinémathèque and any of the cinemas on the Left Bank, and building up as much of knowledge of Hollywood cinema as we could.

that I’d loved and films that had moved me with different eyes. “ “ And what did you see this knowledge as being for? Or was it just pleasure? Yes, pleasure. think it was just pure enjoyment of going to the cinema. remember reading the Cahiers during what’s now referred to as ‘the yellow period’, but was really accumulating the films and absorbing the culture, quite unreflectively, from my point of view at least just for pleasure. So when did this reflectiveness kick in? Was it from watching more avant-garde cinema, where the techniques were made deliberately more visible? No, my shift in spectatorship came very suddenly and specifically out of the influence of the women’s movement, so that was suddenly watching films that I’d loved and films that had moved me with different eyes. Instead of being absorbed into the screen, into the story, into the mise-en-scène, into the cinema, was irritated. And instead of being voyeuristic spectator, male spectator as it were, suddenly became a woman spectator who watched the film from a distance and critically, rather than with those absorbed eyes. Peter became very caught up with new avant-garde tendencies and was becoming very influenced by Godard. Around the late sixties, early seventies, when started being influenced by feminism, whole new types of cinema were appearing in London that hadn’t been seen before. New Brazilian cinema, Godard, Straub-Huillet, African cinema: much more radical ways of approaching storytelling but also ways of visualising ideas and thinking cinematically. At the time, we felt very strongly that Hollywood was finished. you’d asked me… in 1972, would have said that Hollywood would continue to make films, but that would no longer have the power either cinematic or industrial that it had possessed before. SHARE CONTRIBUTE TERMS OF USE PRIVACY POLICY CURRENT ISSUE SUBMISSIONS ABOUT US CONTACT SHOP