BEAUTY IN ENORMOUS BLEAKNESS

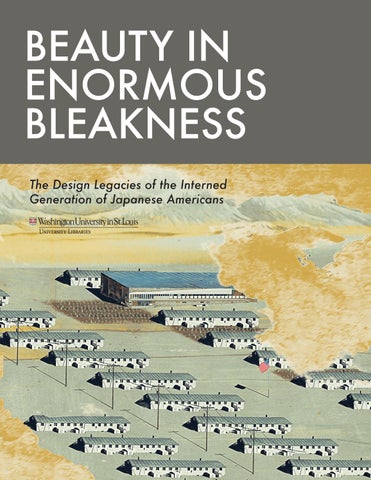

The Design Legacies of the Interned Generation of Japanese Americans

Beauty in Enormous Bleakness (BIEB) is a multi-layered research initiative that includes oral histories, site-based research, a podcast series, and book publication. For more information on this project, please visit the BIEB website at www. beautyinenormousbleakness.com.

Colophon

Beauty in Enormous Bleakness was designed by Danielle Ridolfi using Adobe InDesign on an iMac. The typefaces used are Futura and Brandon Grotesque.

Text © 2023 Heidi Aronson Kolk and Kelley Van Dyck Murphy. All installation photography by Kelley Van Dyck Murphy. Front and back cover Japanese American Influences on the St. Louis Landscape, Kelley Van Dyck Murphy and Makio Yamamoto, 2023.

BEAUTY IN ENORMOUS BLEAKNESS

The Design Legacies of the Interned Generation of Japanese Americans

Curated by Kelley Van Dyck Murphy & Heidi Aronson Kolk with Lynnette Widder & Gabriela Naomi Caden Senno

“If I hadn’t gone to that kind of place, I wouldn’t have realized the beauty that exists in enormous bleakness.”

—Chiura Obata (1885–1975), Japanese American artist and survivor of Topaz, Arizona prison camp

BEAUTY

IN ENORMOUS BLEAKNESS

Beauty in Enormous Bleakness (BIEB) is a multi-layered research initiative that explores architecture’s relationship to issues of immigration, exclusion, and cultural identity in 20th-century American life, focusing on the design legacies of the mass-incarceration of individuals of Japanese descent during WWII. Through various means—oral histories, site-based research, a podcast series and book publication, and this exhibition—BIEB collaborators seek to document the lives and works of Japanese American architects who survived internment, focusing on their vital contributions to the post-war cultural landscape.

The foundational phase of the project has considered four architects—Gyo Obata, Richard Henmi, George Matsumoto, and Fred Toguchi— who left so-called internment camps to study at Washington University in St. Louis. Two of them (Obata and Henmi) settled permanently in the St. Louis region, leading influential firms (HOK and Henmi & Associates) that would produce some of the most-recognizable and -beloved modernist architecture in our region. Like so much art and design work produced by the interned generation, their work would be embraced as “American,” “democratic,” and definitively “modern” in all senses—ideas that required a certain willful disregard of events of the recent past.

Acknowledging the 80th anniversary of the arrival of Japanese American students at Washington University in St. Louis, this exhibition recounts

some of this history and showcases the architects’ influential work, while exploring the hidden history of internment and postwar reintegration—“hidden,” that is, in plain sight, across St. Louis, and the broader American landscape, in locations both celebrated and unknown.

Curated by:

Kelley Van Dyck Murphy (College of Architecture), Heidi Aronson Kolk (College of Art), both of the Sam Fox School, with Lynnette Widder (Columbia University) and Gabriela Noami Caden Senno (yonsei + ’22).

Supported by:

a Faculty Collaboration Grant from The Divided City: An Urban Humanities Initiative (Mellon Foundation + The Center for the Humanities), the Sam Fox School for Design & Visual Arts, Olin Library (Department of Special Collections), and the American Culture Studies Program, all at Washington University.

Special thanks to:

Jessi Cerutti (Exhibitions Manager), Ian Lanius (Exhibitions Preparator), and Miranda Rectenwald (Curator of Local History) from Olin Library; Gabriela Naomi Caden Senno and Makio Yamamoto (BIEB Digital + Research Assistants); the students in the FA22 Matsumoto Modern case studies seminar; and members of the Japanese American community in St. Louis, including Rod Henmi (son of Richard Henmi), Kiku Obata (daughter of Gyo Obata), and other descendants.

5 Washington University Libraries

Beauty in Enormous Bleakness / An Exhibition 6

INTRODUCTION

This project takes its name from a quote by Chiura Obata, the renowned sumi-e painter and father of one of the subjects of the study, architect Gyo Obata. Obata recalled noticing the beautiful colors of the sunrise in a “place where no living thing exists”1 during his in Topaz Internment Camp in the Sevier Desert in Arizona. In an excerpt of an oral history from 1965, Obata recounts his experience,

“…the rising sun in the morning and the sunset is very calm, with a complex mixture of color which is beyond description. I feel so profound gratitude for these things, and in that sense,…I was not feeling abandoned. Instead, I learned a lot. If I hadn’t gone to that kind of place, I wouldn’t have realized the beauty that exists in enormous bleakness.”2

This realization informed his belief that artwork holds the attributes of the artist and an

1 Shipyu Wang, Chiura Obata, An American Modern. (Oakland, University of California Press, 2018), 141.

2 Ibid.

Opposite Letter from Chancellor Throop Regarding Gyo Obata, 1942. Courtesy of Washington University Libraries.

understanding of one’s self in the world.

In 1942, shortly after Pearl Harbor, President Roosevelt signed a now-infamous executive order authorizing the removal of any or all people from military zones “as deemed necessary or desirable” for national security. Within a few months, 120,000 Americans of Japanese descent had been forcibly relocated to hastily-built prison camps in California, and later, Utah, Wyoming, Colorado, and Arkansas. More than two-thirds of those interned—some 80,000—were American-born citizens.

Civil rights groups mobilized to advocate for internees’ rights, and where possible, to help them resettle outside the exclusion zones. Among these organizations was the National Japanese American Student Relocation Council, which worked to secure placement for college-aged Japanese Americans in universities outside the exclusion zones. More than 4,000 students would pursue higher education at a handful of Midwestern and East Coast institutions, among them Washington University in St. Louis.

7 Washington University Libraries

Washington University admitted a total of thirty students in 1942, and would accept some 50 more before the end of the war. Among them were Gyo Obata, Richard Henmi, George Matsumoto, and Fred Toguchi, all of whom studied architecture. Chiura Obata describes his relief and concern after his son, Gyo was accepted to Washington University:

“...The most difficult thing was our second son Gyo, who later became an architect, had just entered as a freshman in the University of California architectural department. Gyo told me, ‘We were born in America. We have no reason to be forced into camp without any crime. If I am put into a camp with papa and mama I would run away.’ We were very worried...During the time when we were being forced into camp, he got the help of many different friends, he contacted many different universities asking if they could accept him, and finally he got permission from the architectural department of Washington University in St. Louis. So we finally sent him to Washington in St. Louis under the guard of a military personnel. Because we didn’t have much money at that time we sold as much as we could, even the oatmeal, to save money and send it there...”3

By all accounts, Washington University made the Japanese American students welcome. The director of one progressive organization, the Campus Y (YMCA)—a man named Arno Haack—advocated vigorously for the students from the moment they stepped foot in St. Louis. Working with local organizations, including churches, to secure housing, jobs, and other support, he also “ran interference”

3 Ibid.

in an effort to prevent negative reactions from the community.

“...Many of these Nisei (American-born citizens) applied for admission to Washington University and were promptly accepted. Our discrimination policy was thus selective— requiring non-admission of blacks but no proscription of Japanese. Actually [WashU was] one of the first schools in the country to take this prompt action. [But] it was clear that no action would be taken apart from the routine of enrollment, in spite of the potential problems that these students would bring with them. So the Y moved into action. We were notified somehow of the first arrival, who turned out to be Gyo Obata (now the distinguished St. Louis architect)…”4

Yet these new students faced a difficult psychological reality. Having enrolled in the university sight unseen, they had to acclimate quickly to a whole new life in the Midwest while working to meet the demands of a rigorous program of study.

And they had to do all of this while their families— indeed, their entire communities—remained imprisoned in Arizona, Utah, and Arkansas. Arno Haack describes meeting Obata, and then other students who followed in his footsteps:

“[His]prompt acceptance brought him on his way [to St. Louis] before his family left for temporary accommodations in the horse stalls of the Tanforan [San Bruno, CA] race track. We met him at the train [station] and found him a perplexed and frightened youngster...Very

4 “Arno Haack’s written memories of his years as Director of the Washington U Campus Y, 1930–1948,” Oral Histories of the Japanese American Community in St. Louis (S0682), State Historical Society of Missouri, 8.

Opposite

Helen and Soichi Henmi at the Jerome Relocation Center, Photographer unidentified, 1943. Courtesy of The State Historical Society of Missouri.

Beauty in Enormous Bleakness / An Exhibition 8

9 Washington University Libraries

Beauty in Enormous Bleakness / An Exhibition 10

soon many others arrived and were asking the obvious questions would they be accepted? Was the war time community attitude a threat? How should they act? And many others. We met with them individually and as a group, assuring them of our support and the acceptance they were sure to find on campus—and [had discussions about] things they might do to avoid difficulty. Actually, at the time, we could only guess what problems might turn up in the community.” (8)

In a 1987 oral history, Richard Henmi recollected Haack’s warm greeting when he and his friend Ted

Ono got off the train at Union Station in late fall of 1942. “Arnold was a wonderful supporter to us, and the Campus Y literally [became] our second home.” He goes on to describe the hospitality of a downtown church, Christ Church Cathedral, which hosted social gatherings for the Nisei:

“We didn’t know where to go in a strange town. So they invited us to come down and use their social hall and we put on music, dancing, conversation and we used the swimming pool and occasionally the apartments. It was a wonderful place to get together. Niseis in other parts of the city were able to join in with the students. They were wonderful people who made us very welcomed…St. Louis was a rather, I feel, a fairly good place to live at that time. There wasn’t too much animosity toward us because of our race or features. I didn’t run into any real serious problems myself. I think there were some isolated incidents, but on the whole, St. Louis was a good place.”5

St. Louis may well have been more outwardly “accepting” of the students than west coast cities would have been, but racial discrimination remained a defining factor of their life situation, as it would be after the war.

5 “Richard T. Henmi Interview (February 10, 1987),” Oral Histories of the Japanese American Community in St. Louis (S0682), State Historical Society of Missouri.

Opposite

11 Washington University Libraries

Above

Gyo Obata at Washington University, Photographer unidentified, 1943. Courtesy of Kiku Obata.

Letter from the Japanese American Student Relocation Council to Chancellor Throop, 1942. Courtesy of Washington University Libraries.

On “Internment”

While people still use the word “internment” to refer to the period and events in question the mass incarceration of some 120,000 individuals of Japanese descent, about two-thirds of whom were American citizens the term is by many seen as deeply problematic. Survivors and descendants have objected to its use for decades, although their views on the matter are by no means unified. Meanwhile, some historians have generally continued to use the term descriptively, albeit with a sense of its fraught and problematic nature.

Likewise, the phrase often used by survivors to describe the physical places of internment “the camps” has been called the ultimate euphemism for what amounted to carceral complexes in a variety of forms (from crudely built barracks to high-security prisons), most of them surrounded by barbed wire, and defended by armed guards. Conditions varied somewhat from camp to camp, but internees in all locations suffered routine violations of their civil and human rights, and all manner of indignities and abuses, not to speak of daily deprivations inherent to life in prison camps.

While there are still ongoing debates as to what language best describes the Japanese American experience of confinement during WWII, many Japanese American advocates and scholars have opted to use the word “incarceration,” as the collaborators on this project have done wherever possible.*

The internment ordeal involved more than temporary incarceration. It began with forced relocation, and wide-scale disinheritance the systematic stripping away of incarcerees’ businesses, pets, personal possessions, and the loss of their livelihoods, communities, and communal heritage. This uprooting was, for many incarcerees, all-but-permanent: returning to their places of origin, and reclaiming their former lives, was not possible.

Layered on top of these traumas were the painful experiences associated with postwar “reentry” and “recovery,” which were very often predicated upon silence and strategic forgetting, even within the Asian American community. The silence and forgetting have been reinforced by time and distance, and uneven education on the history of Japanese American wartime experiences. Put simply, the ordeal of internment has not entered the collective imagination of the war or postwar America, much less become collective national heritage.

Learn more about the contested terminology associated with the history of “internment” at www.densho.org/terminology/#incarceration.

Read more about the various ties of incarceration and their histories at encyclopedia.densho.org/ Sites_of_incarceration/

Opposite

List of Japanese-American Students Registered During 1941–1942 at Washington University in St. Louis, 1941. Courtesy of Washington University Libraries.

13 Washington University Libraries

FINDING A FOOTING

Washington University School of Architecture

Washington University was the only institution among the schools accepting Japanese Americans which had a College of Architecture. The program was built on the Beaux-Arts tradition of architectural education and was known for its high degree of rigor. Coursework centered around the idea of the atelier or studio in which students of various backgrounds worked under the guidance of a practicing architect. One of the first assignments involved the design and hand-construction of a wooden toolbox for use throughout the program. A later assignment, as shown in Dick Henmi’s student sketches, entailed the design of a modest singlefamily house. A flat roof, minimalist form and glass block windows characterize the house as modern in every sense.

Obata, Henmi, Matsumoto, and Toguchi who arrived within a few semesters of one another, and interacted often plunged into their studies. But they

had their work cut out for them, for the university did not offer financial support, and they had to pay for housing.

In his oral history, George Matsumoto membered his days babysitting, house cleaning, and tending the garden for local St. Louis families. Henmi later recollected that he supported himself through odd jobs. One especially memorable project involved constructing a scale model of the South Wing addition of the City Art Museum (now the Saint Louis Art Museum) designed by Murphy & Mackey, for which he got paid $600.6

While studying at WashU, the four students began to build impressive portfolios that would position them well after graduation which, in Obata and Henmi’s cases, were delayed by stints in the U.S. Armed Forces.

As soon as it was possible, Obata and Henmi arranged to bring members of their family from the prison camps to St. Louis, where they would remain

6 Ibid.

Opposite

15 Washington University Libraries

Ted Ono, Yo Matsumato, Dick Henmi at Washington University, Photographer unidentified, 1942. Courtesy of The State Historical Society of Missouri.

until after the war. The transition carried with it a number of challenges, including housing and jobs.

With help from local advocates, the Henmis found lodging in the carriage house of a wealthy business owner who employed his father Soichi as the caretaker. His mother Helen, who had once run a fashion school, worked as a seamstress. They never regained the economic or social standing they had as owners of a grocery business in Fresno. When asked why he and his family chose to leave camp when many others didn’t a decision that took a certain amount of courage Dick answered, simply, “I guess we were a little gutsy. My mother and father [left after I did], and they went on their own…” As for why he was so determined to finish his schooling during the war, he noted, simply, “the Isseis always stressed education….Take the benefit of as much education as possible [as it] would help you in the long run.”7

7 Ibid.

Obata’s family also came: his parents, and an older brother and younger sister all arrived within a year, and, with the help of Haack, found placement. Gyo’s father Chiura Obata—renowned painter and UC-Berkeley art professor accepted a job painting window display backgrounds for $15 a week (Haack later noted how “embarrassed” he was “to offer this to an artist who had done a mural for the San Francisco Opera.”).8

While they managed to secure work, the family faced discrimination house listings mysteriously being pulled when they attempted to go see them as did many other families whom Haack and his collaborators helped get settled in St. Louis. Even their intensive advocacy efforts, could not insulate the Obatas and Henmis from the everyday racism of life in a divided city.9

8 “Arno Haack’s written memories.” 23.

9 Ibid 24–25.

Beauty in Enormous Bleakness / An Exhibition 16

Left

“Going Back to Civilian Life” booklet, undated. Courtesy of Rod Henmi.

Top and Bottom Right

Dick Henmi’s student work at Washington University School of Architecture, circa 1943–45. Courtesy of Rod Henmi.

Bottom Left

17 Washington University Libraries

Gyo Obata in his Army Uniform. Photographer unidentified, 1946. Courtesy of Kiku Obata.

Above

Gyo, Yuri, Haruko and Chiura Obata, Webster Groves, Missouri, Hikaru Iwasaki, 1944. Courtesy of the Bancroft Library at the University of California, Berkeley.

Below

Helen, Ed, Dick, and Soichi Henmi in St. Louis, Photographer unidentified, 1944. Courtesy of State Historical Society of Missouri.

Opposite Architectural Society photo (including Japanese American students Hiroshi Kasamoto, Gyo Obata, Fred Toguchi, Robert Kiyasu, and George Matsumoto). Washington University Hatchet, 1943. Courtesy of Washington University Libraries.

Beauty in Enormous Bleakness / An Exhibition 18

19 Washington University Libraries

Establishing Professional Roots

Within a few years of graduation, all four Washington University-trained architects had found places in influential firms, and would eventually be named be partners in practices responsible for the important public buildings seen in this exhibition. But this was hardly a foregone conclusion, given the discriminatory practices within their communities, and the white-masculinist field of architecture that they were entering. Nor did it come without psychological costs.

In her essay exploring the cases of extremely influential Nisei artists/designers, Sanae Nakatani shows how, in media depictions of their careers, the “Japanese American success story” was made to align with “celebratory national narrative[s] of benevolent assimilation and liberal democratic values,” even as it “understated the factors of race, class, and gender that significantly affected one’s chances of achieving the American dream.”10

10 Sanae Nakatani, “‘Successful’ Nisei: Politics of Representation and the Cold War American Way of Life,” Pacific and American Studies 15 (March 2015), 143–162, p. 145.

These representations have constituted a “multiculturalist” historicism by means of which Japanese American artists’ racial/ethnic identities are not only celebrated, but made definitive, and de-politicized. They are made into “ethnic representatives” that is, “cultural figures” singular both for what they accomplish and what they “overcome.” Such are stories of ambition, creativity, skill, resilience, and, ultimately, assimilation, and in which internment recedes into the background. Set against these stories, there is a well of racial grief, which, as cultural-literary studies scholar Anne Annlin Cheng argues, should be understood as foundational to the formation of racial identity.

Gyo Obata

Following graduation from Washington University, Obata earned master’s degrees in architecture and urban design from the Cranbrook Academy of Art in Bloomfield Hills, Michigan, mentoring under Finnish-American architect Eliel Saarinen. After serving in the Army, Obata joined the offices of Skidmore, Owings, and Merrill in Chicago. He later returned to St. Louis to join the firm of Minoru Yamasaki where he worked on the design of a new terminal for the St. Louis Lambert International Airport. A few years later, Obata joined George Hellmuth and George Kassabaum to establish the St. Louis-based world-renowned architecture firm Hellmuth, Obata & Kassabaum. Notable buildings by HOK include the Abbey at the St. Louis Priory School, the James S. McDonnell Planetarium at the St. Louis Science Center, the National Air and Space Museum, and the Japanese American National Museum.

Left Henmi Logo, from Henmi & Associates, Inc. Architects and Planners Booklet, circa 1981. Courtesy of The State Historical Society of Missouri.

Beauty in Enormous Bleakness / An Exhibition 20

21 Washington University Libraries

Above Gyo Obata in the HOK offices, Photographer unidentified, 1981. Courtesy of Washington University Libraries.

Below Gyo Obata and Minoru Yamasaki. Photographer unidentified, 1951. Courtesy of Kiku Obata.

Richard Henmi

Henmi accounted for his relatively rapid success in securing good work in St. Louis by describing the pathbreaking work of successful Nisei colleagues:

“[They] were doing good work in the field, especially people like Yamasaki, who designed the World Trade Center and [the Lambert airport] terminal, [and who] was a partner at that time to Hellmuth, Yamasaki and Langberger [sp?]…the predecessor of Hellmuth and Kassabaum…which brought Gyo in as partner [when Yamasaki left].” He added that “being at least of the same race, in this case, helped us because they thought [the] Japanese were good designers….Anyway there was good work being done by fellow architects. And I took advantage of that.”11

Henmi spent several years working as an architect with St. Louis-based Schwartz & Van Hofen before becoming a partner (Schwartz & Henmi), and later Henmi & Associates. His firm worked on a wide range of projects across the region, from prominent hotels and mixed-use urban planning projects to public housing and hospitals.

Fred Toguchi

Toguchi worked in St. Louis after graduation and then relocated to Cleveland, where he established his own firm, and designed schools, office buildings, churches, and libraries, as well larger projects, among them the Burke Lakefront Airport Terminal and the Frank J. Lausch State Office Building. His firm was praised for their collaborative model, and Toguchi himself described as an exceedingly patient designer, committed to the highest-quality results.12

Toguchi also designed modern residences in Cleveland and nearby suburbs. The work often

11 Richard T. Henmi Interview.

12 Richard Fleischman Interview (September 29, 2006), Cleveland Regional Oral History Collection. Interview 951017.

Beauty in Enormous Bleakness / An Exhibition 22

Above Portrait of Gyo Obata, Henry T. (“Mac”) Mizuki, 1955.

Courtesy of The Missouri Historical Society.

Below

Dick Henmi at Work in his Architecture Firm, Photographer unidentified, 1961. Courtesy Rod Henmi.

featured open floor plans, natural materials, and expansive views to the outdoors. Several of the homes were featured in Progressive Architecture and other journals and won awards from the American Institute of Architecture.

George Matsumoto

Matsumoto, who, like Obata, attended Cranbrook after Washington University, worked at influential firms such as Skidmore, Owings & Merrill and then pursued a long teaching career, including at the University of Oklahoma, UC-Berkeley and North Carolina State Universities, where he was one of the founding members of the School of Architecture.

George Matsumoto made a significant mark on the mid-century suburban landscape of North Carolina, designing over thirty award-winning residences between 1948 and 1961. These designs for demonstration homes for General Electric and Westinghouse, vacation houses sponsored by Women’s Day and the Douglas Fir Plywood Association, and commissions for clients interested in new ideas in architecture—served as prototypes for domestic living, and were inspired by postwar logics of mass production. Matsumoto’s houses aspired to be functional, beautiful and affordable, while also providing a model for modern American domesticity.

23 Washington University Libraries

Above Portrait of Fred Toguchi, Photographer unidentified, undated. Courtesy of Betty Toguchi.

Below Portrait of George Matsumoto, Photographer unidentified, circa 1958. Courtesy of University of North Carolina State University Libraries.

BUILDING A NEW HOME

All four architects settled in smaller cities far from the exclusion zones Obata and Henmi in St. Louis, Matsumoto in Raleigh, and Toguchi in Cleveland. All four found relative security and opportunity in their adoptive cities, and spoke of friends who, by comparison, were unable to find design work on the west coast.

Not only that, but all four experienced considerable success as well as creative autonomy in these new places. Their speculative and built works from the post-war period provided opportunities to challenge norms, and amplify experimental aspects of design, through focused investigations of the potential of new materials, innovative construction systems, or provocative formal capabilities.

Henmi Residence

Henmi designed a house in Kirkwood, Missouri in his early days as a designer, and then a partner, with local architecture firm, Schwartz & Van Hoefen, reputedly the oldest firm west of the Mississippi. According to interviews with his son Rod Henmi

(also an architect and graduate of Washington University’s College of Architecture), Henmi spent his evenings and weekends building the house, brick by brick, with help from his father, brother, and friends, including Ted Ono. It was a labor of love, and one that signaled the family’s arrival into the middle class.

The Henmi home was sited in a hilly, wooded section at the outskirts of the new suburb, and its design incorporated natural materials, a low-slung roof and floor-to-ceiling windows—features that were relatively uncommon for suburban St. Louis at the time. Rod recalls how, even decades later, his father was still making improvements, and that he learned about design principles from watching him at work.

Obata Residence

Gyo Obata also designed his family’s residence, a modest home on a sloping lot on Greeley Avenue in Webster Groves, Missouri. The sloping site allowed Obata to develop a split-level scheme that took advantage of the uneven terrain and doubled

25 Washington University Libraries

Opposite Woman’s Day Douglas Fir Plywood Associates Vacation Home, George Matsumoto, 1958. Courtesy of North Carolina State University Libraries.

Beauty in Enormous Bleakness / An Exhibition 26

the interior square footage while still allowing for plenty of light. For the exterior of the home, Obata devised an innovative modular panel system that incorporated modern architectural materials such as glass, stucco, and aluminum.

The Architectural Record featured the home in its Recording Houses of 1959, celebrating its “simple elegance, expansive livability” and cost effectiveness (under $18,000 total). Obata’s design represented a “thoughtful interlarding of practicality and sensitivity,” and incorporated “familiar (and formal) techniques [that were] perked up by little surprises,” such as the subtly asymmetrical vertical panels on the front facade, and the roofing material: white marble chips.13

13 Record Houses of 1959, Architectural Record, Mid-May, 1959. 112–115.

Opposite Above

Henmi House, Richard Henmi, 1951-1952. Photographer unidentified, 1950. Courtesy of The State Historical Society of Missouri.

Opposite Below

Henmi House, Richard Henmi, 1951-1952. Photographer unidentified, 1951. Courtesy of The State Historical Society of Missouri.

Above

Art Filmore, “Residence for Mr. and Mrs. Gyo Obata, St. Louis, Missouri,” HOK, as it appeared in the Architectural Record, May 1959. Courtesy of Washington University Libraries.

Below

Obata Residence Drawings, circa 1950s. Courtesy of Kiku Obata.

27 Washington University Libraries

Above

Below Douglas Fir Plywood Association Cabin as it appeared in Women’s Day, August 1958, George Matsumoto, 1958. Courtesy of Washington University Libraries.

Beauty in Enormous Bleakness / An Exhibition 28

House in the Round from the Home and Garden Show, Fred Toguchi, 1964. Courtesy of Betty Toguchi.

Toguchi Residence

Fred Toguchi’s “House in the Round” (1964), a “glamorous” four-bedroom home with a distinctive cylindrical shape, was in its time declared the “epitome of wonderland elegance.”14 That same year, a local paper company executive commissioned Toguchi, who generally did not design residences, to build him a cedar-clad home in Pepper Pike, an otherwise traditional neighborhood “lined with colonials with manicured lawns.” Its distinctive pagoda-style roof created abundant “living and

14 “Home and Flower Show Planned,” The Amherst News-Times, 26 December 1963.

Above Student Drawings and Models from Matsumoto Modern, David Yi, Ella Matthews, Jacob Davies, Jacob Greengo, Alex Lyu, and Stephen Pan, FL 2022. Courtesy of The Sam Fox School of Design and Visual Arts at Washington University in St. Louis.

The architectural models and drawings shown here, and are included in the physical exhibition, were created during a Fall 2022 Sam Fox School / College of Architecture case study course called Matsumoto Modern. Students engaged in archival research, building analysis, digital modeling and drawing, and physical model building for selected Matsumoto-designed modern homes throughout the semester.

sleeping spaces,” as Toguchi later explained, that “are thrust into the trees for the most intimate relationship with nature.” “All in all, the object was to achieve a quiet statement of living in the woods.”15

In these and other residential designs, Toguchi often left units such as ductwork and conduit pipes exposed to add interest to interior spaces. His residential designs featured natural materials like wood and cork, and large windows to provide a connection to the outdoors.

Matsumoto Residence

The George and Kimi Matsumoto House (1953) is a post-and-beam house designed in the International Style and sited on a sloped wooded lot in Raleigh, North Carolina. Taking form as a “floating” wooden box suspended over the landscape, the avantegarde home was distinct from the local more traditional homes of the area.

The house functioned as both residence and an architecture studio where Matsumoto’s design concepts and teaching materialized in full-scale. The house, with sweeping views from one side of the house to the other, had natural materials such as wood paneling and cork and floor-to-ceiling windows—signaling a connection to nature and the outdoors. The exterior of the house had Japaneseinfluenced details including a symmetrical paneled facade resembling Shoji screens and a recessed door.

Matsumoto emphasized an economy of materials throughout the house by utilizing standardized materials and modular construction. He deliberately chose to expose the character of the plywood, glass and concrete used to compose the structure, stressing his focus on efficiency, privacy, and site.

29 Washington University Libraries

15 Michelle Jarboe, “Cool Spaces: Mid-century modern house in Pepper Pike grabbed the same buyer twice,” Cleveland Plain Dealer 16 December 2015.

PURPOSE AND MOTIVES

What did it mean for individuals who endured the radical dislocation of incarceration to resettle so far from their points of origin, in relatively conservative, racially divided Midwestern and southeastern cities? What did “reentry” look like in these places, which had relatively small populations of Japanese American communities, and small design communities?

Without a doubt, the building of new homes and joining of established firms represented the start of new lives, and forging of new social identities for these architects. But their participation in these worlds involved adopting something of an accommodationist stance the setting-aside of grievances—the “forgetting”—one might even say, the “suppressing”—of collective traumas and losses.

More to the point, their success as architects and businessmen—which involved collaboration with white partners and progress-oriented community leaders—required a kind of pragmatism, and a future mindedness. Ironically, when their Japanese

American identity did receive acknowledgment, it often came in the form of euphemistic talk about their “quiet determination” and “ambition,” their “resilience” and “assimilation”—the causal factors, the sufferings they had endured, of course never being named.

Indeed, the broader internment ordeal, not to mention internees’ painful “reentry” experiences, sit on the edges of public consciousness and memory. These episodes have been “marked by silences and strategic forgetting,” even within the Asian American community. These silences have been reinforced with time and distance, and uneven education on the history of the incarceration. Put simply, such experiences have not entered the shared imagination of the war, much less become collective national heritage.

Acknowledging this gap, Beauty in Enormous Bleakness aims to advance the work of recovering those pasts, and more specifically, to bring them into view alongside the recognizable and even

31 Washington University Libraries

Opposite

Photograph of the Beauty in Enormous Bleakness Exhibition, Thomas Gallery, John B. Olin Library, Washington University, 2023. Courtesy of Washington University Libraries.

iconic (but under-studied), features of the postwar cultural landscape, and more specifically, the accomplishments of the four Japanese American architects in question. The exhibition does this through imaginative re-engagement with the built environment, as well as the traditional archives—oral histories, architectural drawings, press coverage, family photographs, and more, which it seeks to animate through storytelling.

Much of that storytelling work is visual in nature, and can be seen in the large scroll-like collage above, a kind of imaginary landscape that represents both eastern and western artistic traditions, and draws upon a diverse array of contemporary and historical visual sources and techniques.

The configuration and visual logic of the landscape is inspired by paintings in Ukiyo-e tradition in particular, Scenes in and Around the Capital (17th or 18th century), a pair of six-panel folding screens depicting many of the most prominent sites in Kyoto.16 The map-like quality of the image and golden clouds specifically recall Scenes in and Around the Capital. The drawing also engages a tradition of panoramic mapping popular in the late nineteenth century St. Louis’s most-famous being Compton and Dry’s magisterial Pictorial St. Louis, the great metropolis of the Mississippi valley; a

topographical survey drawn in perspective A.D. 1875 (1876).

Designing the Collage

As noted, the design for the collage was inspired by ukiyo-e, a Japanese painting and woodblock printing style popular in the Edo period (1603–1867), in which diverse spatial and temporal elements, including design artifacts (buildings, bridges, gardens), atmospheric elements such as clouds, and topographical features are drawn together into a single landscape. Sometimes referred to as “pictures of the floating world,” these multi-layered landscapes evoke dreams, or memoryscapes, in which past and present and objects remote and close-by, seen and unseen merge and interact.

To create this specific “picture of the floating world,” we began with a background sampled from Chiura Obata’s painted skies over the dusty orange Arizona desert, which in this rendering, are made to peer through the golden ukiyo-e style clouds, shifting between the concealment and display of these lost spatial histories.

The color palette chosen ochres, browns, greens, and pale blues are colors often found in mid-century modern interiors as represented in architectural drawings and brochures, while the

Beauty in Enormous Bleakness / An Exhibition 32

16 Scenes in and around the Capital (rakuchu rakugai zu), 17th or 18th Century, Japan (The Shimane Art Museum, Matsue, Shimane Prefecture, Japan).

dithered halftone patterning recalls mid-century modern lifestyle magazines such as Women’s Day and Better Homes & Gardens. Like the panoramic map, the drawing records identifiable geographical and architectural details (which are gleaned from photographs), and encourages close looking and identification of landmarks. But as with Scenes in and around Kyoto, a surreal quality is introduced by the presence of multiple and converging perspectives, which imply or even foster a shifting gaze. As one scans the landscape horizontally west to east one moves from a desert scape and rows

of prison camps to the iconic architectural and landscape works by Obata, Henmi, Matsumoto, and other Japanese American designers linked to St. Louis.

This movement is not intended to suggest some kind of strict chronology, much less a teleology of “progress” or “career achievement. Rather, it is meant to evoke dislocation and relocation, and the loose trajectory of creative work, which is so often characterized by unplanned convergences and distorted echoes visible in the exhibition, for instance, in the juxtaposition of Henmi family photographs taken in front of the prison barracks and the Henmi family home built less than a decade later in Kirkwood.

Bringing together material landscape and cultural memory, we seek to show how they are interwoven, mutually constitutive phenomena, and in so doing, to highlight the convergences of then and now, remote and close-by, visible and invisible and to

Top

Japanese American Influences on the St. Louis Landscape, Kelley Van Dyck Murphy and Makio Yamamoto, 2023. Courtesy of Washington University Libraries.

Left Above

Scenes in and Around the Capital (Rakuchu Rakugai Zu), 17th or 18th century. Courtesy of The Shimane Art Museum, Matsue, Shimane Prefacture, Japan.

Left Below

Pictorial St. Louis, the Great Metropolis of the Mississippi Valley; a Topographic Survey Drawn in Perspective A.D. 1875, Richard Compton and Camille Dry, 1876. Courtesy of The Library of Congress.

33 Washington University Libraries

Designing the Exhibition

In the exhibition, a variety of physical objects photographs, drawings, architectural models and other 3-D artifacts, as well as snippets of oral histories and personal correspondence provide additional layers of visual / textual information. These items correspond to the locations found on the collage but also in the lives and experiences, the memories, of the designers in question.

Our curatorial approach for the exhibition has been informed by a concept of “landscape” that encompasses official and vernacular sites and practices of planning and development on a large scale, for example of building highways and courthouses and sports arenas and more localized actions and interventions, local ways of knowing and improving the community, which involve adaptation and use and repurposing. Geographer J. B. Jackson describes this as a landscape that is formed “not just by topography and political decisions, but by the indigenous organization and development of spaces to serve the needs of the focal community: gainful employment, recreation, social contacts, contacts with nature, contacts with the alien world”.

Many aspects of the landscape lack the monumentality and ostensible permanence and that special kind of visibility that memorials or courthouses or town squares generally have. These lesser-known elements of the landscape are nonetheless powerful expressions of local identity and community as it has been lived, negotiated, and sometimes contested. They testify to resilience and collective memory, and diverse cultural heritages, of the Japanese Americans who designed them.

Beauty in Enormous Bleakness / An Exhibition 34

explore the tensions, contradictions, and uneasy juxtapositions that constitute the terrain of cultural memory and forgetting. In this sense, we seek to acknowledge both the hyper-present and the erased or disregarded, the consciously and unconsciously known, features of that terrain and also the problems of erasure and forgetting.

Below

35 Washington University Libraries

Photographs of the Beauty in Enormous Bleakness Exhibition, Thomas Gallery, John B. Olin Library, Washington University, 2023. Courtesy of Washington University Libraries.

PUBLIC SITES IN ST. LOUIS

Some of the earliest commercial projects with which the WashU-trained architects were associated would become their most memorable. This is especially evidence in the case of St. Louis-based designers, Henmi and Obata. The McDonnell Planetarium in Forest Park, and the “Flying Saucer” on Grand Avenue, for instance, are beloved St. Louis landmarks that have been featured on tourist maps, t-shirts, postcards, and magazines. And other projects in which they played a strong shaping hand, such as the Mansion House, Priory Chapel, the Magic Chef headquarters (with a ceiling designed by Isamu Noguchi), as well Lambert International Airport, have also been widely celebrated, some of them given awards for their distinctive designs or innovative engineering.

Still other of these sites Brentwood Bowl, and the American Zinc Building for instance while perhaps less-famous, are no less significant in the cultural sense, having achieved iconic status in St. Louis’s mid-century modern canon.

These and many other buildings designed by the interned generation of Japanese American architects have given expression to a range of postwar ideals, and served as anchors of community identity and public life. All of them have had measurable social impact, and contributed to the rapidly expanding landscape of modern design.

While some of these public buildings have been featured in architectural magazines or textbooks, many have fallen out of vogue, and indeed out of public view, in recent decades. A few, however— including the Flying Saucer and the Noguchi ceiling, and Toguchi’s Pepper Pike house have enjoyed “rediscovery” as specimens of “mid-century modern design.”

Whether now esteemed or overlooked, many of these buildings were taken, in their time, to exemplify American values and ideals, as well as modernist design sensibilities and innovations. Not only that, but their Japanese American designers were often conscripted into a postwar Nisei “success story,” which, as Sanae Nakatani has shown,

37 Washington University Libraries

Opposite Aerial View of Downtown, Henry T. (“Mac”) Mizuki, 1967. Courtesy of Missouri Historical Society.

was made to align with “celebratory national narrative[s] of benevolent assimilation and liberal democratic values,” even as it “understated the factors of race, class, and gender that significantly affected one’s chances of achieving the American dream.”17

For this reason, the buildings might well be interpreted as sites of forgetting, in multiple senses. Set against these stories, there is a well of racial grief, which, as cultural-literary studies scholar Anne Annlin Cheng argues, should be understood as foundational to the formation of racial identity.

Preserving Mid-Century Modern Design

Many of the buildings seen here were first showcased in national design journals and the newspapers, and have since featured in textbooks and mid-century architecture/design enthusiasts’ blogs. They have also been regularly photographed. Some of the buildings have also been advocated for by preservation-minded entities such as the Landmarks Association of St. Louis, the Preservation Research Office, and ModernSTL. But even if they have been especially well-loved, enshrined as “historical significant” in national register applications, their fates have not always been secure. Some have been demolished, or obscured, and many that survive remain endangered despite their iconicity.

More to the point, their underlying histories, and the unique life experiences of their designers, remain largely unrecognized, even by a public which has at-times celebrated them.

The Japanese Garden

In 1972, members of the local chapter of the Japanese American Citizens League (JACL) selected a renowned landscape architect and UCLA professor, Koichi Kawana, to design a Japanese-

17 Sanae Nakatani, “‘Successful’ Nisei: Politics of Representation and the Cold War American Way of Life,” Pacific and American Studies 15 (March 2015), 143–162, p. 145.

style garden for St. Louis’s venerable Missouri Botanical Garden (MOBOT).

An elaborate, multi-year project, the Japanese Garden would be built on the site of an existing lake at MOBOT, and funded by donations from the JACL, along with the National Council of State Garden Clubs, Inc, and the local chapter of Ikebana International, among others). The garden was conceived as a gift to the city of St. Louis, expressing Japanese American residents’ gratitude for the “warm welcome” extended to them during and after WWII (including those, like Obata and Henmi, who first came to the city as WashU students).

Kawana’s ambitious incremental design called for the construction of bridges, islands, peninsulas, waterfalls, and many other landscape elements to be integrated slowly, with attention to the condition and arrangement of existing planting. In a 2021 interview, former MOBOT president Dr. Peter Raven explained that the garden should be considered a “natural area,” but one cultivated in the Japanese style, with objects such as a tea house, stone lanterns, and a Zen garden, and hundreds of flowering trees and shrubs—each one placed deliberately to highlight the inherent features of the landscape.

The resulting garden not only dramatically transformed the botanical garden as a whole, but became the central focal point for visitors, many of whom, as long-time head gardener Ben Chu recently noted, name it as their favorite element of MOBOT. Kawana himself described the design as an “expression of the Japanese character,” and indeed, since ground was broken on the garden in 1973, it has served as both a site, and a symbol, of Japanese (American) cultural heritage and memory. These include public events such as the hugely popular Japanese Festival that takes place on-site

Beauty in Enormous Bleakness / An Exhibition 38

39 Washington University Libraries

Above Japanese Garden at the Missouri Botanical Garden, Koichi Kawana, 1977. Henry T. (“Mac”) Mizuki, 1978. Courtesy of Missouri Historical Society.

each September, as well as numerous private ones. A granite chrysanthemum-shaped sculpture titled “Shumeigiku,” made by Gyo Obata’s wife, Mary Frances Judge, and honoring Courtney Bean Obata, is one of several such personal memorials / tribute objects in the garden.

Henry T. Mizuki

Many of the buildings designed by the WashU four were first showcased in national trade publications architecture journals, lifestyle magazines, and newspapers, where they were recognized, and often given awards, for their innovative designs. They have since achieved a new kind of attention in design textbooks, historic register applications and mid-century modern enthusiasts’ blogs.

Contributing to their visibility and appeal are the many architectural photographs taken of this work over the decades, including a large number taken by long-time St. Louis-based Japanese American photographer Henry T. “Mac” Mizuki, several of which are featured in this exhibition.

Mizuki specialized in documenting commercial buildings both during and after construction and he soon developed a relationship with the partners of HOK, who hired him to shoot many their projects. He also devoted considerable time to capturing iconic public buildings across the St. Louis region, and produced striking streetscapes, interiors, and aerial photos. Many of these ran in regional papers including the St. Louis Post-Dispatch, and served to foster local enthusiasm for the city’s distinctive version of modernist design.

The Abbey Church

The Abbey Church at the St. Louis Priory School was commissioned and designed as a place of worship for the Benedictine monks of the Saint Louis Abbey. Designed in consultation with the Italian architect and engineer Pier Luigi Nervi, the church consists of three successive tiers of thin castin-place concrete parabolic arches that rise above a circular plan. A bell tower with a central skylight illuminates the altar below. Translucent wall panels provided the interior with consistent soft white light casting an atmosphere of meditative serenity within the monastic church.

Beauty in Enormous Bleakness / An Exhibition 40

Above

St. Louis Priory Church, Gyo Obata / Hellmuth, Obata & Kassabaum, 1962. Henry T. (“Mac”) Mizuki, 1964. Courtesy of Missouri Historical Society.

Top to Bottom, Left to Right Mansion House Center, Richard Henmi / Schwarz & Van Hoefen, 1966. Henry T. (“Mac”) Mizuki, 1965. Courtesy of Missouri Historical Society.

Brentwood Bowling, Richard Henmi, 1954. Henry T. (“Mac”) Mizuki, 1954. Courtesy of Missouri Historical Society.

St. Louis Priory Church, Gyo Obata / Hellmuth, Obata, & Kassabaum, 1962. Henry T. (“Mac”) Mizuki, 1961. Courtesy of Missouri Historical Society.

Lambert International Airport, Minoru Yamasaki / Hellmuth, Yamasaki & Leinweber, 1956. Henry T. (“Mac”) Mizuki, 1954. Courtesy of Missouri Historical Society.

41 Washington University Libraries

Noguchi Ceiling

In 1946, local architect Harris Armstrong commissioned the Japanese American sculptor Isamu Noguchi to design a sculptural lobby ceiling in the American Stove Company headquarters building in St. Louis. Noguchi’s ceiling was one of three built lunar landscapes inspired by his incarceration at the Poston Internment Center, which he voluntarily entered in 1942. Noguchi created dozens of plaster models of lunar landscapes; however, only three were built—a ceiling in the Time and Life Building in New York, the interior wall of the SS Argentina Ocean Liner, and the American Stove Company ceiling in St. Louis. The American Stove ceiling, though only recently uncovered in 2016, is the only lunar landscape still in existence today. The earlier models, often misunderstood as sculptures, were proposals for spaces meant to be inhabited.

Beauty in Enormous Bleakness / An Exhibition 42

Below Mansion House Towers, Richard Henmi / Schwarz & Van Hoefen, 1966. George McCue, 1973. Courtesy of The State Historical Society of Missouri.

Above Magic Chef Building Ceiling, Isamu Noguchi, 1946. Hedrich-Blessing, 1948. Courtesy of Washington University Libraries.

Opposite

James McDonnell Planetarium, Gyo Obata / Hellmuth, Obata & Kassabaum, 1963. Dorrill Studio, 1962. Courtesy of Missouri Historical Society.

Beauty in Enormous Bleakness / An Exhibition 44

The Flying Saucer

Left

One of the most-iconic of these specimen mid-century modern buildings also happens to be (comparatively speaking) one of the humblest: a former Phillips 66 gas station. Designed by Dick Henmi in 1967 (then with Schwarz & Van Hoefen), the “Flying Saucer,” as it came affectionately to be called, sat at the heart of a mixed-used development project known as Council Plaza, much of which still stands today—at a notoriously complicated/dangerous intersection of Grand Avenue and Highway 40 near Saint Louis University.

Council Plaza was built on contested ground: the southwestern corner of the former Mill Creek Valley district, which until 1960, had been home to a thriving African American community of some 20,000 residents. Today, the Saucer now home to a Starbucks and a Chipotle stands as a silent testament to another era of city planning one predicated on “slum” clearance and wide-scale redevelopment as well as to the early stages of Dick Henmi’s career.

In 2009–2010, the building became the subject of a grass-roots “Save the Saucer” preservation campaign when its impending demolition was announced. Channeling their affections for the gas-station-turned-diner-turned-drive-thru taco-joint, or their a love for midcentury modern design, activists rallied successfully to save the building at a time when many others from the same era were torn down.

Opposite Above

The American Zinc Building, Gyo Obata / Hellmuth, Obata & Kassabaum, 1967. Henry T. Mazuki, 1967. Courtesy of Missouri Historical Society.

Opposite Below

Steinberg Hall, Fumihiko Maki, 1959–1960. Photographer unidentified, circa 1970. Courtesy of Washington University Libraries.

45 Washington University Libraries

The Flying Saucer, Richard Henmi / Schwarz & Van Hoefen, 1967. Ian Lanius, 2023. Courtesy of Washington University Libraries.

CONCLUSION

This exhibition underscores the significance of telling a more complete and nuanced version of design history that incorporates insights from personal and community histories alongside career narratives and analysis of works. The underlying histories of these works, and the unique life experiences of their designers, remain largely unrecognized, even by a public which has at-times celebrated them.

There are powerful connections between material objects and their creators’ lived experiences, particularly when it comes to how their educational, professional and personal lives become entwined. This project juxtaposes traditional archival sources with stories and sites––elements that have not been viewed together. By placing personal artifacts, archival documents, and storytelling in conversation with architectural sites, the exhibition itself can be seen as a three-dimensional “picture of the floating world” linking design history, material landscape, and cultural memory. Moving from the dislocated landscape of the western internment camps to the creative works of the architects in their Midwestern contexts, this hybrid spatial continuum evokes

Opposite Mansion House Center, Richard Henmi / Schwarz & Van Hoefen, 1966. Henry T. (“Mac”) Mizuki, 1965. Courtesy of Missouri Historical Society.

paradoxical concepts of relocation and dislocation, achievement and self-repression.

While attending to such past preservation efforts, Beauty in Enormous Bleakness aims to document these buildings, their origins, and the ongoing significance, in other ways: by means of visual study and documentation, historical storytelling, and site-specific explorations. This documentation has involved archival and oral histories work, a podcast series, and course-based research, an edited volume and accompanying symposium (April 2023).

Together, these activities seek to reconstruct the hidden histories of internment—“hidden,” that is, in plain sight—across St. Louis, and in the broader American landscape, in locations both monumental and vernacular, celebrated and unknown. Beauty in Enormous Bleakness, aspires to tell an urgently needed new chapter in design and architectural history that acknowledges the signal contributions of Japanese Americans to post-war culture and cultural life. Ultimately, we hope to create new visibility for work generated by especially creative members of the interned generation while also expanding the public imagination for the culture legacies and inheritances of the war.

47 Washington University Libraries

Exhibition Inventory

Exhibition Case

“30 American Born Japanese Students from West Coast in Colleges Here.” St. Louis PostDispatch (St. Louis, MO), Oct. 27, 1942.

Coverage of ground-breaking, opening celebration, and ongoing construction of Japanese Garden, Missouri Botanical Garden Bulletin 1974–1977, Missouri Botanical Garden, Peter H. Raven Library.

Dick Henmi’s Army Uniform Cap. c. 1945. Rod Henmi Family Collection.

Dick Henmi in his Army Uniform, c. 1945, S0682, St. Louis Japanese American Citizens League Records 1930–1951, The State Historical Society of Missouri. St. Louis, Missouri.

Dick Henmi in his Army Uniform. n.d. Photograph. Rod Henmi Family Collection.

Family members at Henmi residence in Kirkwood, MO, 1953, S0682, St. Louis Japanese American Citizens League Records 1930–1951, The State Historical Society of Missouri.

Flying Saucer at Naugles Restaurant. c. 1970s. Photograph. Retro & Cool.

Henmi, Dick. Original folder of Dick Henmi’s student work at WashU’s School of Architecture, including sketches for a kitchen arrangement in a suburban home. c. 1943–45. Rod Henmi Family Collection.

Henmi Family in St. Louis, 1944, S0682, St. Louis Japanese American Citizens League Records 1930–1951, The State Historical Society of Missouri.

“Japanese Americans Call St. Louis a Friendly Haven.” St. Louis Post-Dispatch (St. Louis, MO), Jan. 26, 1956.

Japanese American Citizens League (JACL) newsletter outlining the history of Japanese Americans in St. Louis. 1958. Rod Henmi Family Collection.

Kawana, Koichi. Sketch of Japanese Garden in “Japanese Garden Planned for Lake Area.” 1973. Drawing. Missouri Botanical Garden Bulletin LXII, pg. 1.

Letter to Isamu Noguchi from Harris Armstrong,

1947, Series 3, Box 1, Folder: American Stove Company/Magic Chef Building 46–5, Harris Armstrong Collection, Department of Special Collections, Washington University Libraries.

Mansion House Promotional Materials. 1966. Rod Henmi Family Collection.

Midwest Architect: Structural Aesthetics. October 1973. American Institute of Architects.

Nisei Coordinating Council of St. Louis from the St. Louis Nisei Newsletter. 1946. Rod Henmi Family Collection.

Obata, Gyo. Obata Residence Drawings. c. 1950s. Kiku Obata Family Collection.

Obata, program and ticket for JACL Full Moon Festival, 1960, S068, St. Louis Japanese American Citizens League Records 1930–1951, The State Historical Society of Missouri. Okubo, Miné. TREK Magazine. December 1942. Rod Henmi Family Collection.

Pettit, Karl. Japanese Garden Footbridge Under Construction. c. 1974. FL20619.

Planetarium Photographs and Objects. 1950s. The Saint Louis Science Center Archives.

Reflected Ceiling Plan, Plot Plan and Aerial Perspective of Magic Chef Building, St. Louis, c. 1946–7, Series 5, Drawer 1-4-8, Folder 465, American Stove Company (St. Louis, MO) Administration Building, Harris Armstrong Collection, Department of Special Collections, Washington University Libraries.

“Residence for Mr. and Mrs. Gyo Obata, St. Louis, Missouri” in “Record of Houses 1959.” Architectural Record, May 1959.

Schwarz & Van Hoefen, Blueprint and Renderings of Mansion House, Downtown St. Louis. 1966. Rod Henmi Family Collection.

Exhibition Powerpoint

2 and 3 Bedroom Homes for Woman’s Day Magazine—Exterior Rendering 3 Bedroom, MC00042-005-FF0025-000-001_0011, George Matsumoto Papers 1945 to 1991, Special Collections Research Center, North Carolina State University Libraries.

American Zinc Building. n.d. Photograph. National Park Service.

Anthony’s Bar. 2020. Photograph. Google Reviews.

Ashtabula Arts Center, Fred S. Toguchi, FAIA Architect, 1922–1982, Arts Prize Recipients, 1965 Cleveland Arts Prize For Architecture, Cleveland Arts Prize.

Blair Hall, 1961, Building and Infrastructure Archives, University Archives, University of Missouri Libraries.

Bristol Primary School Exterior. 1956. Photograph. HOK.

Bristol Primary School Interior. 1956. Photograph. HOK.

Brentwood Post Office. c. 2023. Photograph. Rod Henmi Family Collection.

Burke Lakefront Airport, Fred S. Toguchi, FAIA Architect, 1922–1982, Arts Prize Recipients, 1965 Cleveland Arts Prize For Architecture, Cleveland Arts Prize.

Cecil and Bryce Dewitt Residence Exterior, George Matsumoto, FAIA, 1922-2016, US Modernist, Modernist Archive.

Cecil and Bryce Dewitt Residence Interior, George Matsumoto, FAIA, 1922–2016, US Modernist, Modernist Archive.

David P. Wohl Senior Mental Health Center. 2011. Photograph. Vanishing STL: Chronicles of the Vanishing Urban Landscape of St. Louis.

Eric and Jeanette Lipman Residence Exterior, George Matsumoto, FAIA, 1922–2016, US Modernist, Modernist Archive.

Eric and Jeanette Lipman Residence Interior, George Matsumoto, FAIA, 1922–2016, US Modernist, Modernist Archive.

Fine Arts Building, 1958, Building and Infrastructure Archives, University Archives, University of Missouri Libraries.

Frank J. Lausche State Office Building, Fred S. Toguchi, FAIA Architect, 1922–1982, Arts Prize Recipients, 1965 Cleveland Arts Prize For Architecture, Cleveland Arts Prize.

George and Kimi Matsumoto House Exterior,

Beauty in Enormous Bleakness / An Exhibition 48

George Matsumoto, FAIA, 1922–2016, US Modernist, Modernist Archive.

George and Kimi Matsumoto House Interior, George Matsumoto, FAIA, 1922–2016, US Modernist, Modernist Archive.

George W. and Virgina Kelly Residence, George Matsumoto, FAIA, 1922–2016, US Modernist, Modernist Archive.

George W. Poland House Exterior, George Matsumoto, FAIA, 1922–2016, US Modernist, Modernist Archive.

George W. Poland House Interior, George Matsumoto, FAIA, 1922–2016, US Modernist, Modernist Archive.

Greyhound Bus Terminal Exterior. n.d. Photograph. Flickr.

Greyhound Bus Terminal Interior. 1967. Photograph. Flickr.

Gwendolyn Sully Hudson Residence Back Exterior, George Matsumoto, FAIA, 1922–2016, US Modernist, Modernist Archive.

Gwendolyn Sully Hudson Residence Front Exterior, George Matsumoto, FAIA, 1922–2016, US Modernist, Modernist Archive.

Henmi Residence, 1953, S0682_0108, St. Louis Japanese American Citizens League Records 1930–1951, The State Historical Society of Missouri.

I.B.M. Building Exterior Rendering, MC00042005-FF0042-000-001_0001, George Matsumoto Papers 1945 to 1991, Special Collections Research Center, North Carolina State University Libraries.

J. Gregory Poole Cabin, George Matsumoto, FAIA, 1922–2016, US Modernist, Modernist Archive.

J. Gregory Poole Lake House Exterior, George Matsumoto, FAIA, 1922–2016, US Modernist, Modernist Archive.

J. Gregory Poole Lake House Interior, George Matsumoto, FAIA, 1922–2016, US Modernist, Modernist Archive.

Kirkwood F. and Sarah Adams Residence, George Matsumoto, FAIA, 1922–2016, US Modernist, Modernist Archive.

Kenneth C. Beck Center for the Cultural Arts, Fred S. Toguchi, FAIA Architect, 1922–1982, Arts Prize Recipients, 1965 Cleveland Arts Prize For Architecture, Cleveland Arts Prize.

Mansion House Apartments. n.d. Photograph. Atomic Dust.

Milton Julian House Exterior, George Matsumoto, FAIA, 1922–2016, US Modernist, Modernist Archive.

Milton Julian House Interior, George Matsumoto, FAIA, 1922–2016, US Modernist, Modernist Archive.

Mizuki, Henry T. Building, Hellmuth, Obata and Kassabaum Office, Interior. 1956. Photograph. Mac Mizuki Photography Studio Collection, Missouri Historical Society. St. Louis, Missouri.

Mizuki, Henry T. Laborers at Work on the St. Louis Priory Church, 530 South Mason Road, Creve Coeur. 1961. Photograph. Mac Mizuki Photography Studio Collection, Missouri Historical Society. St. Louis, Missouri.

Paul O and June Richter House Exterior, George Matsumoto, FAIA, 1922–2016, US Modernist, Modernist Archive.

Paul O June Richter House Interior, George Matsumoto, FAIA, 1922–2016, US Modernist, Modernist Archive.

Pi Kappa Alpha Fraternity House at North Carolina State University, George Matsumoto, FAIA, 1922–2016, US Modernist, Modernist Archive.

Rendering by Schwarz and Van Hoefen Showing Mansion House Apartments, c. 1960, P0197-S04-00011, 1950 to 1959, 1960 to 1969, Missouri Historical Society.

Southern Illinois University. 1961. Photograph. HOK.

The Galleria Houston. 1969. Photograph. HOK.

Trefts, Charles. Brown Shoe Company. 1954. Photograph. Charles Trefts Photographs, The State Historical Society of Missouri. St. Louis, Missouri.

Woman’s Day Home, George Matsumoto, FAIA, 1922–2016, US Modernist, Modernist Archive.

Works Cited

“Arno Haack’s written memories of his years as Director of the Washington U Campus Y, 1930-1948,” Oral Histories of the Japanese American Community in St. Louis (S0682), State Historical Society of Missouri, 8.

“Richard T. Henmi Interview (February 10, 1987), “Oral Histories of the Japanese American Community in St. Louis (S0682), State Historical Society of Missouri.

“Arno Haack’s written memories.” 23.

Sanae Nakatani, “‘Successful’ Nisei: Politics of Representation and the Cold War American Way of Life,” Pacific and American Studies 15 (March 2015), 143–162, p. 145.

“Richard T. Henmi Interview.

”Richard Fleischman Interview (September 29, 2006), Cleveland Regional Oral History Collection. Interview 951017.

Record Houses of 1959, Architectural Record, Mid-May, 1959, 112–115.

“Home and Flower Show Planned,” The Amherst News-Times, 26 December 1963.

Michelle Jarboe, “Cool Spaces: Mid-century modern house in Pepper Pike grabbed the same buyer twice,” Cleveland Plain Dealer 16 December 2015.

Scenes in and around the Capital (rakuchu rakugai zu), 17th or 18th Century, Japan (The Shimane Art Museum, Matsue, Shimane Prefecture, Japan).

Sanae Nakatani, “‘Successful’ Nisei: Politics of Representation and the Cold War American Way of Life,” Pacific and American Studies 15 (March 2015), 143–162, p. 145.

49 Washington University Libraries