British Dermatological Nursing Group

Volume: 23 Issue: 4

Skin of colour Understanding sun safety and risk

Phototherapy

The knowledge gaps facing dermatology nurses

Educating children Promoting skin health awareness in schools

The BDNG Members Journal delivered to you by

1,2

ILUMETRI ® is indicated for the treatment of adults with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis who are candidates for systemic therapy. 2

ILUMETRI® offers early and long-term control and proven effectiveness in skin treatment including sensitive areas*2-4

ILUMETRI® restores patients’ wellbeing from week 16 up to week 52 in line with general population averages7,9

ILUMETRI® is the only anti-IL-23 giving the flexibility to individualise therapy whilst maintaining an acceptable safety profile1,5,6

Could any of your patients benefit from ILUMETRI® and our enhanced value support services?

*Sensitive areas such as scalp, nails, genitals and palmo-plantar2-4

1. ILUMETRI® SmPC. Almirall. 2. Thaçi D, Piaserico S, Warren RB, et al. Br J Dermatol. 2021;185(2):323–334. 3. Thaçi D, Gerdes S, Jardin K, et al. Dermatol Ther.2022;12(10):2325-2341. 4. Magnolo N, et al. Presented at DDG Congress, Mar 1-3 Wiesbaden, Germany, 2024. P030. 5. Tremfya® Summary of Product Characteristics. Janssen. 6. Skyrizi® Summary of Product Characteristics. AbbVie. 7. Mrowietz U, Augustin M, Sommer R. Abstract presented at 25th World Congress of Dermatology, Singapore, 3–8 July, 2023. 8. Dauden E, Mrowietz U, Sommer R, et al. Presented at 51st National Congress AEDV, 22-25 May; Madrid, Spain. 2024. Current SPA version: 166/2374/199. 9. EuroFound “European Quality of Life Survey - Data visualisation. Eurofound https://www.eurofound.europa.eu/data/european-quality-of-life-survey. Last accessed August 2024.

ILUMETRI® (tildrakizumab) PRESCRIBING INFORMATION

Please consult the Summary of Product Characteristics (SmPC) before prescribing ILUMETRI® is available as 100 mg and 200 mg solution for injection in pre-filled syringes. Active Ingredient: Each pre-filled syringe contains 100 mg or 200 mg of tildrakizumab in 1 mL or 2 mL. Tildrakizumab is a humanised IgG1/k monoclonal antibody produced in Chinese Hamster Ovary (CHO) cells by recombinant DNA technology. Also contains 0.5 mg/mL polysorbate 80 (E 433). Indication: ILUMETRI is indicated for the treatment of adults with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis who are candidates for systemic therapy.Dosage and Administration: The recommended dose of ILUMETRI is 100 mg by subcutaneous injection at weeks 0, 4 and every 12 weeks thereafter. In patients with certain characteristics (e.g. high disease burden, body weight ≥ 90 kg) 200 mg may provide greater efficacy. Consideration should be given to discontinuing treatment in patients who have shown no response after 28 weeks of treatment. Some patients with initial partial response may subsequently improve with continued treatment beyond 28 weeks. Injection sites should be alternated. Elderly: No dose adjustment is required. Renal or hepatic impairment: No dosage recommendations can be made. Paediatric population: No data available. Contraindications, Precautions and Warnings: Contraindications: Hypersensitivity to the active substance or to any of the excipients listed in SmPC section 6.1. Clinically important active infection, e.g. active tuberculosis. Precautions: To improve traceability always record the batch number of the administered product. ILUMETRI has the potential to increase the risk of infections. If a patient develops a serious infection, the patient should be closely monitored and treatment with ILUMETRI should not be administered until the infection resolves. Exercise caution in patients with a chronic infection or a history of recurrent or recent serious infection. Instruct patients to seek medical advice if signs or symptoms of an infection occur. Patients should be evaluated for tuberculosis (TB) prior to initiation of treatment and monitored for signs and symptoms of active TB during and after treatment. In patients with a history of latent or active TB, consideration for anti-TB therapy should be given. Discontinue

use if a serious hypersensitivity occurs. All appropriate immunisations should be completed prior to start of treatment with ILUMETRI. If a patient has received live viral or bacterial vaccination it is recommended to wait at least 4 weeks prior to starting treatment with ILUMETRI. Patients treated with ILUMETRI should not receive live vaccine during treatment and for at least 17 weeks after treatment. This medicine contains polysorbate. Polysorbates may cause allergic reactions. Fertility, pregnancy and lactation: Women of childbearing potential should use effective methods of contraception during treatment and for 17 weeks after treatment. As a precautionary measure, it is preferable to avoid the use of ILUMETRI during pregnancy. A decision must be made whether to discontinue breast-feeding or to discontinue/abstain from ILUMETRI therapy taking into account the benefit of breast-feeding for the child and the benefit of therapy for the woman. The effect of ILUMETRI on human fertility has not been evaluated. Adverse Reactions: Very common (≥1/10): Upper respiratory tract infections. Common (≥1/100 to <1/10): Headache, gastroenteritis, nausea, diarrhoea, injection site pain, back pain. Immunogenicity: In pooled Phase 2b and Phase 3 analyses, 7.3% of tildrakizumab-treated patients developed antibodies to tildrakizumab up to week 64. Of the subjects who developed antibodies to tildrakizumab, 38% (22/57 patients) had neutralizing antibodies. This represents 2.8% of all subjects receiving tildrakizumab.

Please consult Summary of Product Characteristics for further information. Legal Category: Ireland: Subject to prescription which may not be renewed (A). United Kingdom & UK/NI: POM Price & Pack: United Kingdom 100 mg pre-filled syringe - £3,241; 200 mg pre-filled syringe - £3,241 Ireland 100 mg pre-filled syringe Price to wholesaler 200 mg pre-filled syringe Price to wholesaler

Marketing Authorisation Number(s): IE & UK(NI) - EU/1/18/1323/001 ; EU/1/18/1323/003 GB - PLGB 16973/0038 ; PLGB 16973/0045

Further information available from: Almirall Limited, Harman House, 1 George Street, Uxbridge, Middlesex, UB8 1QQ, UK.

Date of Revision: 08/2024 Item code: UK&IE-ILU-2400045

UK-Adverse events should be reported. Reporting forms and information can be found at MHRA https://yellowcard.mhra.gov.uk or search for MHRA Yellow Card in the Google Play or Apple App Store. Adverse events should be also reported to Almirall Ltd. Tel. 0800 0087 399

IE-Adverse events should be reported. Reporting forms and information can be found at HPRA Pharmacovigilance, Website: www.hpra.ie. Adverse events should be also reported to Almirall Ltd. Tel: +353 1800849322

Celebrating a busy year for PEM

Ingrid Thompson

Skin at School: Educational materials on skin and skin diseases for primary schools

Jolien van der Geugten, Karin Veldman

Professional development

The importance of education to enhance phototherapy nursing practice: Feedback from the BDNG Manchester Meeting 2024

Stephanie Greenleaf

What additional educational materials do nurses need to help them care for patients with cutaneous T-cell lymphoma? A report of a BDNG survey

Rebecca Penzer-Hick

A week in the life of a primary care

Lucy Evans-Hill

cancer and sun protection for people with skin of colour

Conducting a literature review: Part four – critical appraisal

Laura

Management of a patient living with PsA exhibiting symptoms of dactylitis and enthesitis: A case study

Jing Husaini BDNG meets

to understand the psychological impact of skin disease

Ella Guest, Rob Mair

The advantages of taking a Master’s degree in advanced clinical practice

Rod Tucker, Emma Button

classes of oral antibiotics are associated with severe adverse cutaneous reactions? Rod

new in the world of research? Rod Tucker

for the workforce

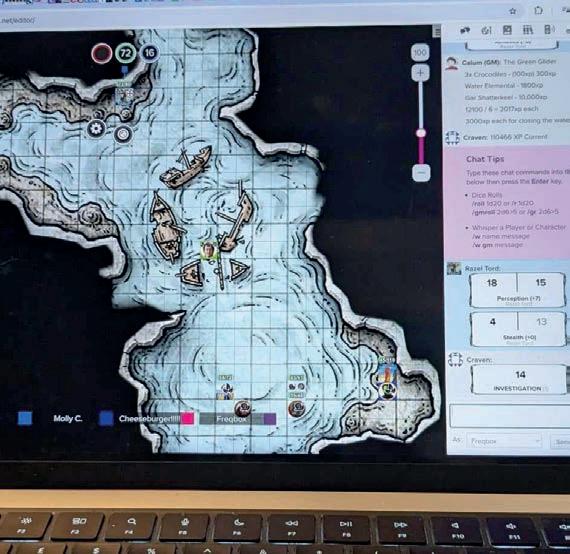

Dungeons and Dragons: Where stress lessens and adventure beckons Molly Connolly

news

An update from the BDNG’s Member and International Liaison Lead

overseas perspective on the BDNG’s annual conference

Editorial

Jackie Tomlinson

Chair of the Editorial Board

Dermatology Clinical Nurse Specialist, Addenbrooke’s Hospital, Cambridge University Hospitals Foundation Trust

Polly Buchanan

Clinical Editor

Community Dermatology Nurse Specialist, NHS Fife pauline.buchanan2@nhs.scot

Rob Mair

Managing Editor

Rob.Mair@pavpub.com

Lauren Nicolle

Deputy Editor

Lauren.Nicolle@pavpub.com

Tony Pitt

Art Director

Tony.Pitt@pavpub.com

Commercial

Mark Freeman

Journal, Conference & Corporate Sponsorship Sales dnadvertising@bdng.org.uk 07957 404 831

Editorial board

Mandy Aldwin/Sarah Griffiths-Little Ichthyosis Support Group

Tanya O. Bleiker

Consultant Dermatologist, University Hospitals of Derby and Burton NHS Foundation Trust

Julie Brackenbury

Aesthetic Nurse Practitioner, JB Cosmetic, Bath

Ivan Bristow

Podiatrist and Associate Professor, Southampton

Sara Burr

Senior Lecturer, Centre of Postgraduate Medicine and Public Health, University of Hertfordshire. Community Dermatology Specialist Nurse/Clinical Lead Community Skin Integrity Team, Norfolk Community Health and Care

NHS Trust

Fiona Cowdell

Professor of Nursing and Health Research, Faculty of Health, Education and Life Sciences, Birmingham City University

Elfie Deprez

PhD student and Psoriasis Nurse Specialist, University of Ghent, Belgium

Steven Ersser

Professor of Nursing and Dermatology Care and Head of Department of Nursing Science, Bournemouth University

Mark Goodfield

Consultant Dermatologist, Leeds Teaching Hospitals NHS Trust

Karina Jackson

Nurse Consultant, St John’s Institute of Dermatology, Guy’s and St Thomas’ NHS Foundation Trust, London

Teena Mackenzie

Education and Development Lead, British Dermatological Nursing Group

Dermatological Nursing is the official journal of the BDNG. To contact the BDNG, email: admin@bdng.org.uk or tel: 02892 793 981

Printed in Great Britain by Micropress, Fountain Way, Reydon Business Park, Reydon, Suffolk, IP18 6SZ

The BDNG logo and name are Registered Trademarks. All registered rights apply.

Chris McCabe

UK Medical Strategy Lead for Immunology, UCB Pharma

Jodie Newman

Education Nurse, British Dermatological Nursing Group

Michelle Ogundibo

Paediatric Dermatology Nurse Specialist, Chapel Allerton Hospital, Leeds Teaching Hospitals NHS Trust

Rebecca Penzer-Hick

Senior Lecturer, Postgraduate Medicine, University of Hertfordshire and Dermatology Specialist Nurse, Dermatology Clinic Community Services, Cambridgeshire

Kathy Radley

Senior Lecturer, School of Life and Medical Sciences, University of Hertfordshire and Dermatology Nurse Specialist, Dermatology Community Clinic Services, Cambridgeshire

Alison Schofield

Head of Education, Tissue Viability Nurse Consultant at NHS Pioneer Wound Healing and Lymphoedema centres.

Karen Stephen

Lead Dermatology Nurse, NHS Tayside

Delia Sworm

Trainee Advanced Clinical Practitioner – Skin Cancers (Oncology), St Luke’s Cancer Centre, Royal Surrey NHS Foundation Trust

Rod Tucker

Community Pharmacist/Researcher with a Special Interest in Dermatology, East Yorkshire

Andrew Thompson

Clinical Health Psychologist and Reader in Clinical Psychology, University of Sheffield

Carrie Wingfield

Dermatology Nurse Consultant, Norfolk and Norwich University Hospital

Dermatological Nursing (ISSN 1477-3368) is published by the BDNG, 82 Antrim Street, Lisburn BT28 1AU Tel: 02892 793 981. www.bdng.org.uk

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored or transmitted in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the BDNG. Opinions expressed in articles are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the BDNG or the editorial/advisory board. Advertisements have no influence on editorial content or presentation.

The advertisements in this journal are for a UK audience only.

Need 24 hours’ hydration? Prescribe ‘Doublebase Once’ – the yellow pack.

Presentation: White opaque gel.

Uses: An advanced, highly moisturising and protective emollient gel for regular once daily use in the management of dry skin conditions such as eczema, psoriasis or ichthyosis. May also be used as an adjunct to any other emollients or treatments.

Directions: All age groups. Apply direct to dry skin once daily or as often as necessary. Can be used as a soap substitute for washing. If applying another treatment to the same areas of skin, apply treatments alternately leaving sufficient time to allow the previous application to soak in.

Contraindications, warnings, side effects etc: Do not use if sensitive to any of the ingredients. Doublebase Once has been specially designed

Proven to provide at least 24 hours’ hydration1,2,3 from just 1 application.

• For the management of dry skin conditions such as eczema, psoriasis and ichthyosis.

• The Doublebase Once advanced gel formulation provides significantly greater and longer-lasting skin hydration than ointments1,2 following a single application over 24 hours.

for use on dry, problem, or sensitive skin. Rarely skin irritation (mild rashes) or allergic skin reactions can occur on extremely sensitive skin, these tend to occur during or soon after the first few uses and if this occurs stop treatment.

Instruct patients not to smoke or go near naked flames. Fabric (clothing, bedding, dressings etc) that has been in contact with this product burns more easily and is a potential fire hazard. Washing clothing and bedding may reduce product build-up but not totally remove it.

Ingredients: Isopropyl myristate, liquid paraffin, glycerol, steareth-21, macrogol stearyl ether, ethylhexylglycerin, 1,2-hexanediol, caprylyl glycol, povidone, trolamine, carbomer, purified water.

Pack sizes and NHS prices: 100g tube £2.69, 500g pump pack

Legal category: Class I medical device.

Further information is available from: Dermal Laboratories Ltd, Tatmore Place, Gosmore, Hitchin, Herts, SG4 7QR, UK.

Date of preparation: August 2023.

‘Doublebase’ is a trademark.

Adverse events should be reported. Reporting forms and information can be found at yellowcard.mhra.gov.uk. Adverse events should also be reported to Dermal.

10mm

References: 1. Comparison of the skin hydration of Doublebase Once emollient with Epaderm Ointment in a 24-hour, single application study, in subjects with dry skin. Extract report summarising skin hydration results for wiped off sites. Data on file. Dermal Laboratories Ltd, Hitchin, UK. Epaderm® Ointment is a registered trademark of Mölnlycke Health Care. 2. Antonijevic´ MD & Karajcˇic´ J. Ointments or a gel emollient? Randomised and blinded comparison of the hydration effect on ex-vivo human skin. Data presented at the 17th European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology (EADV) Symposium, May 2022, Ljubljana, Slovenia. 3. Antonijevic´ MD & Karajcˇic´ J. Randomised, open, comparative study of the hydration effect on ex-vivo human skin of two emollient formulations with different recommended application regimes. Data presented at the 17th European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology (EADV) Symposium, May 2022, Ljubljana, Slovenia.

Carrie Wingfield

An invitation to write a reflective guest editorial has resulted in a slightly indulgent laying down of words reflecting on my 30 years in this speciality. I hope you will forgive me if I use the opportunity to present you with a frank cathartic offloading of a rollercoaster career that has been my life, my passion, and my nemesis at times.

My career in dermatology started as a healthcare assistant, working in a busy outpatient department for gynaecology, urology, ENT and dermatology. At that time, the dermatology presence was small, consisting of one dermatologist, a registrar and a GP practitioner. My interest in dermatology began in outpatients with a role-model who was not a nurse, but a young consultant dermatologist whose teaching was forthcoming, kind and nurturing. This convinced me to train as an RGN. On qualifying, after a fleeting stint on a surgical ward, I migrated back to dermatology as a staff nurse. In those early days, phototherapy was administered by physiotherapists

Carrie Wingfield is a Nurse Consultant in Dermatology and ICS Advanced Clinical Practice Lead for NHS Norfolk and Waveney Integrated Care System (ICS), Norfolk & Norwich University Foundation Hospital.

and nurse-led clinics were mostly limited to wart and dressing clinics. I questioned my choice of speciality as I started to deskill in acute nursing skills learnt on the wards. Was this a good career move?

As I learnt my craft, the true worth of this speciality emerged. Its diversity, the layered knowledge required to deliver care for chronic lifelong skin disease, debilitating conditions that impacted on every aspect of life, the stigma, and psychological consequences. This was no ‘Dermaholiday’, a misconception and sometimes a put down I have witnessed within our profession, a perception that sometimes views dermatology as a low adrenaline, sedate and ‘Cinderella’ speciality, a cop out in the nursing world. Boy, did we prove them wrong. The rise of dermatology and evolution of service delivery has put nurses at the forefront of innovative nurse-led services, highly qualified specialists and educational leaders. This is a speciality and career path where nurses can make a difference and where education and drive are needed across the board to improve patient experience and access to specialist care. Changing those misconceptions and pushing the scope of service improvements became an obsession throughout my career.

After a couple of years, I found myself in a senior role and joined the BDNG. On reflection, this was the exposure and opportunity to gain experience from my peers that led to personal accomplishment and exposed me to so many innovative role models. I started a challenging process of instigating departmental change, to encourage a growing consultant and nursing team

to see the true worth of a diverse dermatology workforce. We had to evolve, and this meant unpopular decisions, such as losing the ward where increasingly our beds were lost to non-dermatology patients. This meant moving staff out of their comfort zones. It meant taking risks to move on and establish a team that could meet the challenges and changing face of both dermatology and the NHS. There was resistance and anxiety along the way, but as the workforce started to develop it formed the foundation for a benchmark department that is now unrecognisable from those early days.

A supportive and forward-thinking dermatologist team who work in unison with dermatology nurses is imperative for moving services forward. As a service leader you need to be a voice in your department, put your head above the parapet, do not be frightened about taking risks. Be in no doubt that we can be a dysfunctional family at times, especially as we face the challenges of targets, waiting lists, lack of funding, lack of capacity, staff shortages and insourcing services. All presenting, at times, a sense of loss of control.

My message to the future nursing leaders and dermatology teams is simple: nurture your team, value them, support them, retain, and develop their skills and recognise their talent, do not let them slip through your fingers. Do not ignore those who are struggling, do not shy away from the difficult conversations and confrontations, be part of that change process on a personal level and strive against adversity to keep your dermatology service at the top of its game.

… Adex Gel emollient with an Added Extra anti-inflammatory action.

Adex Gel emollient offers an effective, simple and different approach to the treatment and management of mild to moderate eczema.

Specially formulated with a high level of oils (30%) and an ancillary anti-inflammatory, nicotinamide (4%) to help reduce inflammation.

Can be used continuously, for as long as necessary, all over the body including on the face, hands and flexures.

Adex Gel may help reduce the need for topical corticosteroids.1,2 Does not contain corticosteroids.

Suitable for patients aged 1 year +.

Presentation: White opaque gel.

Uses: Highly moisturising and protective emollient with an ancillary anti-infl ammatory medicinal substance for the treatment and routine management of dry and infl amed skin conditions such as mild to moderate atopic dermatitis, various forms of eczema, contact dermatitis and psoriasis.

Adex Gel - bridges the gap between plain emollients and topical corticosteroids.

Directions: Adults, the elderly and children from 1 year of age. For generalised all-over application to the skin. Apply three times daily or as often as needed. Adex Gel can be used for as long as necessary either occasionally, such as during flares, or continuously. Seek medical advice if there is no improvement within 2-4 weeks. Contra-indications, warnings, side effects etc: Do not use if sensitive to any of the ingredients. Keep away from the eyes, inside the nostrils and mouth. Temporary tingling, itching or stinging may occur with emollients when applied to damaged skin. Such symptoms usually subside after a few days of treatment, however, if they are troublesome or persist, stop using and seek medical advice. Rarely skin irritation (mild rashes) or allergic skin reactions can occur on extremely sensitive skin, these

tend to occur during or soon after the fi rst few uses and if this occurs stop treatment. Vitamin B derivative requirements are increased during pregnancy and infancy. However, with prolonged use over signifi cant areas, it may be possible to exceed the minimum recommended levels of nicotinamide in pregnancy. Safety trials have not been conducted in pregnancy and breast feeding therefore, as with other treatments, caution should be exercised, particularly in the fi rst three months of pregnancy.

Instruct patients not to smoke or go near naked fl ames. Fabric (clothing, bedding, dressings etc) that has been in contact with this product burns more easily and is a potential fi re hazard. Washing clothing and bedding may reduce product build-up but not totally remove it.

Ingredients: Carbomer, glycerol, isopropyl myristate 15%, liquid paraffi n 15%, nicotinamide 4%, phenoxyethanol, sorbitan laurate, trolamine, purifi ed water.

Pack sizes and NHS prices: 100g tube £2.69, 500g pump pack £5.99. Legal category: Class III medical device with an ancillary medicinal substance.

Further information is available from: Dermal Laboratories, Tatmore Place, Gosmore, Hitchin, Herts, SG4 7QR, UK.

Date of preparation: December 2022.

‘Adex’ is a trademark.

Adverse events should be reported. Reporting forms and information can be found at yellowcard.mhra.gov.uk. Adverse events should also be reported to Dermal.

1. Djokic-Gallagher J., Rosher P., Hart V. & Walker J. Steroid sparing effects and acceptability of a new skin gel containing the anti-infl ammatory medicinal substance nicotinamide. Clinical, Cosmetic and Investigational Dermatology 2019;12:545-552.

2. Gallagher J., Gianfrancesco S., Hart V. and Walker J. Performance of Adex Gel: A retrospective survey of healthcare professionals with an interest in dermatology. Data presented at the Austrian Society of Dermatology and Venereology (OGDV) Science Days, September 2022, Bad Gastein, Austria.

Ingrid Thompson

PEM Friends is a small UK-based charity that supports pemphigus and pemphigoid patients and their carers. In the last year, the PEM Friends support group has made some substantial changes, including becoming a charity in February 2024.

Pemphigus and pemphigoid are rare autoimmune blistering diseases that cause blistering on the skin and mucous membranes. They are often confused with each other because they have similar symptoms, but they affect different layers of the skin and cause different types of blisters. Pemphigus and pemphigoid occur when the body’s immune system attacks healthy skin cells, mistaking them for foreign invaders. The exact cause is unknown, but genetics and environmental factors may play a role.

An accurate diagnosis is important in order to find the right treatment and prevent complications like infection, scarring, and vision problems, and in some cases they can be fatal.

On behalf of the PEM Council, here is our update for the year.

We always seem to say the same, but 2024 has been an exceptionally busy year. A huge amount of change has happened.

Most significantly, we became a charity in February, or a charitable incorporated organisation (CIO) to be exact. Becoming a charity has several benefits, not least of which is that we can claim gift aid on any donations, and we have access to more resources than we had before. However, it does bring some pressures, and our administration and management needs to be even tighter than before. Some of the time spent has been in managing the transition, such as developing more policies, setting up ‘Give as you Live’ donations and creating a new bank account to manage the finances. Changing our bank account involves a lot of work to comply with the bank’s terms and conditions. Most of the council have also become trustees, which is a big personal responsibility.

Our long-standing chair, Isobel, stepped down this year and her last day was 31 October. As a leaving present to us, Isobel organised a PEM Zoom meeting with Molly Connolly, Clinical Nurse Specialist from Scotland and a prominent member of the BDNG. We will be posting this talk to the new website soon. With Isobel leaving we now have a new chair, Trina. She has taken on a huge task and we are very grateful to her. We have also re-modelled the PEM Council, with three new people joining including a new treasurer, John, who has the experience and commitment for the role.

We have launched a new website that is packed with information and has regular updates. Development of this is still ongoing, so please do take a look. You can find the website at www.pemfriends. org.uk or use this QR code.

Additional activities this year:

l We had our 3rd AGM, many of us meeting face-to-face for the first time

l We attended a few conferences but, most notably, the British Association of Dermatologists Annual Meeting in July

l We had a PEM Advisory Group meeting (the advisory group are a team of notable clinicians who help us)

l We have participated in several studies and research activities, for example: The Centre of Evidence Based Dermatology in Nottingham have produced a paper just published in the British Journal of Dermatology on ‘Bullous pemphigoid and drugs that may trigger this.’ Also, there is a trial about to start on a new treatment for scarring in ocular mucous membrane pemphigoid (OcMMP) at Birmingham

l Our leaflet campaign has been slow but still progressing

l We have set up a few regional groups.

At our AGM in July, we discussed how we would manage the group in the absence of Isobel, who has done so much for PEM Friends in the last 10 or so years.

Running PEM Friends is a team effort. With 11 people (at its maximum) keeping things going, we manage to maintain our role as a patient group that is respected and well-known to those in the field of pemphigus and pemphigoid across the UK and beyond. We are all volunteers and patients, though we are looking to employ volunteers from outside to help us.

Our plan constantly evolves.

PREVIOUSLY CALLED HAELAN TAPE

Recommended by The British Association of Aesthetic Plastic Surgeons as a simple steroid treatment for scars & keloids1

Fludroxycortide 4 micrograms per square centimetre Tape effectively treats inflammatory dermatoses and it can be cut to any size or shape.

Including hand eczema and finger tip fissures2

Scan the QR code to view the application video. Alternatively visit typharm.com or call 01603 722480 for more information

Typharm Limited, 14D Wendover Road, Rackheath Industrial Estate, Norwich, NR13 6LH

Can be cut to size for scar site

Reference: 1. Scars & Keloids. BAAPS. Available at https://baaps.org.uk/patients/procedures/16/scars_and_keloids [Last Accessed January 2023]. 2. Layton A. Reviewing th e use of Fludroxycortide tape (Haelan Tape) in Dermatology Practice. Typharm Dermatology.

FLUDROXYCORTIDE TAPE PRESCRIBING INFORMATION: Fludroxycortide 4 micrograms per square centimetre Tape See full Summary of Product Characteristics (SmPC) before prescribing. Presentation: Transparent, plastic surgical tape impregnated with 4 micrograms fludroxycortide per square centimetre. Indications: Adjunctive therapy for chronic, localised, recalcitrant dermatoses that may respond to topical corticosteroids and particularly dry, scaling lesions. Posology and Method of Administration: Adults and the Elderly: For application to the skin, which should be clean, dry, and shorn of hair. In most instances the tape need only remain in place for 12 out of 24 hours. The tape is cut so as to cover the lesion and a quarter inch margin of normal skin. Corners should be rounded off. After removing the lining paper, the tape is applied to the centre of the lesion with gentle pressure and worked to the edges, avoiding excessive tension of the skin. If longer strips of tape are to be applied, the lining paper should be removed progressively. Paediatric population: Courses should be limited to five days and tight coverings should not be used. If irritation or infection develops, remove tape, and consult a physician. Fludroxycortide Tape is waterproof. Cosmetics may be applied over the tape. Contraindications: Chicken pox; vaccinia; tuberculosis of the skin; hypersensitivity to any of the components; facial rosacea, acne vulgaris, perioral dermatitis, perianal and genital pruritus; dermatoses in infancy including eczema, dermatitic napkin eruption, bacterial (impetigo), viral (herpes simplex) and fungal (candida or dermatophyte) infections. Warnings and Precautions: Not advocated for acute and weeping dermatoses. Local and systemic toxicity of medium and high potency topical corticosteroids is common, especially following long-term continuous use, continued use on large areas of damaged skin, flexures and with polythene occlusion. Systemic absorption of topical corticosteroids has produced reversible hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis suppression. Long-term continuous therapy should be avoided in all patients irrespective of age. Application under occlusion should be restricted to dermatoses in very limited areas. If used on the face, courses should be limited to five days and occlusion should not be used. In the presence of skin infections, the use of an appropriate antifungal or antibacterial agent should be instituted. Long term continuous or inappropriate use of topical steroids can result in the development of rebound flares after stopping treatment (topical steroid withdrawal syndrome). A severe form of rebound flare can develop which takes the form of a dermatitis with intense redness, stinging and burning that can spread beyond the initial treatment area. It is more likely to occur when delicate skin sites such as the face and flexures are treated. Should there be a reoccurrence of the condition within days to weeks after successful

Waterproof protection once in place

For both children and adults

treatment a withdrawal reaction should be suspected. Reapplication should be with caution and specialist advise is recommended in these cases or other treatment options should be considered. For children, administration of topical corticosteroids should be limited to the least amount compatible with an effective therapeutic regimen. Children may absorb proportionally larger amounts of topical corticosteroids and thus may be more susceptible to systemic toxicity. Pregnancy and Lactation: Use in pregnancy only when there is no safer alternative and when the disease itself carries risks for mother and child. Caution should be exercised when topical corticosteroids are administered to nursing mothers. Undesirable Effects: The following local adverse reactions may occur with the use of occlusive dressings: burning, itching, irritation, dryness, folliculitis, hypertrichosis, acne form eruptions, hypopigmentation, perioral dermatitis, allergic contact dermatitis, maceration of the skin, secondary infection, skin atrophy, miliaria, striae and thinning and dilatations of superficial blood vessels producing telangiectasia. Transient HPA axis suppression. Cushing’s syndrome. Hyperglycaemia. Glycosuria. Adrenal suppression in children may occur. Infected skin lesions, viral, bacterial, or fungal may be substantially exacerbated by topical steroid therapy. Wound healing is significantly retarded. Local hypersensitivity reactions. Stop treatment immediately if hypersensitivity occurs. Withdrawal reactions - redness of the skin which may extend to areas beyond the initial affected area, burning or stinging sensation, itch, skin peeling, oozing pustules. Precautions for Storage: Store in a dry place, below 25oC. Pack Size and Price: Polypropylene dispenser and silica gel desiccant sachet in a polypropylene container, with a polyethylene lid, packed in a cardboard box, containing 20cm or 50cm of translucent, polythene adhesive film, 7.5cm wide, protected by a removable paper liner. 7.5cm x 20cm £19.49. 7.5cm x 50cm £28.95. Legal Category: POM Marketing Authorisation Number: PL 00551/0014 Marketing Authorisation Holder: Typharm Ltd., Unit 1, 39 Mahoney Green, Rackheath, Norwich NR13 6JY. Tel: 01603 722480, Fax:

van der Geugten, Karin Veldman

The implementation of the ‘Skin at School’ programme in the Netherlands was motivated by various factors. Skin complaints are often underestimated, impacting the quality of life for individuals with chronic conditions and contributing to significant bullying effects on children.1-3 In every class, there are children who suffer from skin problems such as warts, athlete’s foot or eczema. Patient representatives reported that children with a chronic skin condition and their parents have questions about how to talk about this at school as not

Summary:

every child is comfortable giving a presentation about his or her condition.

Skin cancer is the most common form of cancer in the Netherlands, with 83,300 reported cases in 2022. Skin cancer is mainly caused by excessive exposure to UV radiation from the sun and tanning beds.4 Children can learn through education about the risk of excessive exposure to UV radiation from the sun and the importance of using sunscreen to prevent skin cancer later in life.

Skin at School aimed to address the underestimation of skin complaints, recognising the impact on children’s quality of life, particularly those who experience bullying as a result of their skin’s appearance. Parents of affected children face challenges discussing these issues at school. The project therefore aimed to empower children aged four to 12 by developing educational materials, fostering knowledge, skills and attitudes about skin. Healthcare professionals, educators, and patient representatives collaborated on a curriculum, resulting in tailored lessons for pupils. Skin at School has been successfully implemented and positively assessed, prompting a call for further research on its broader effects.

Abstract:

Background: The impact skin conditions can have on young people’s quality of life is often underestimated, with many children bullied as a result of their skin’s appearance. Parents of children with skin conditions report facing challenges discussing these issues at school, despite the critical importance of skincare and skin cancer prevention. Moreover, inaccurate information shared on social media is being followed and believed by young people. Education is therefore vital in preventing health risks. Aim: To develop educational materials for children aged four to 12, fostering knowledge, understanding, skills and attitudes about their own and other’s skin. To empower children to prevent health risks and enhance their wellbeing and resilience. Methods: Healthcare professionals, educational experts, and patient representatives collaborated to determine learning objectives, curriculum topics, and assignment designs. The curriculum was carefully crafted to be substantively correct, fitting into the educational context and being appropriate for patient representatives. A children’s council provided advice. Results: The curriculum – comprising five lessons tailored to specific age groups – covers skin basics, skincare, skin colour, temporary and long-lasting skin problems, sun protection, assessing reliable information, acceptance and wellbeing. Conclusion: Skin at school has been successfully developed, implemented and positively assessed. Further research on the effects of this programme is needed.

Author info:

Jolien van der Geugten is Project Manager for Skin at School at the Dutch Skin Coalition (Huid Nederland); Owner and scientific researcher at WYS Research & Education. Karin Veldman is President at the Dutch Skin Coalition (Huid Nederland); President Association for Ichthyosis Networks, The Netherlands; Vice-President European Network Ichthyosis.

Keywords: Skin, Skin disease, Skin cancer, Educational materials, Skin care

Citation:

Van der Geugten J, Veldman K. Skin at School: Educational materials on skin and skin diseases for primary schools. Dermatological Nursing 2024. 23(4):10-16

“Skin cancer is the most common form of cancer in the Netherlands, with 83,300 reported cases in 2022”

Yet dermatologists involved in this project observed inadequate skincare knowledge among participants, including a lack of awareness of the importance of suncream and protecting our skin from sunburn.

Nurses provide care and guidance to children with skin conditions and their parents. Nurses are also involved in the patient journey, and can therefore determine what information children and their parents need at particular times. Educational materials can help nurses inform children and their parents, and these materials can also be used in schools to increase understanding of skin conditions.

We – Jolien Van der Geugten and Karin Veldman – are the initiators of the Skin at School programme, and we found that more knowledge about having a chronic skin condition at school is necessary. In 2009, Veldman was diagnosed with a severe and ultrarare skin condition called Netherton syndrome. Her years in primary school have led to trauma, as she was bullied both mentally and physically. Van der Geugten has three children, one of whom has eczema and one of whom has ichthyosis. Her children are frequently questioned about their flakes or red spots by other pupils. From these experiences, the authors are determined to address the acceptance of children with skin problems, and skin care in general.

In 2020, we carried out a survey among 41 teachers. Around three-quarters of the respondents said students do not know about common and chronic skin problems. Fortunately, a large majority of the teachers believe it is important to have educational materials to improve knowledge about skin and to increase acceptance of students with skin conditions.

Finally, there are many inaccurate messages circulating on social media channels about skincare, which are often followed and believed by young people. For example, the use of blister plasters on acne and that using sunscreen actually causes cancer.5,6 A lack of basic knowledge about the skin is a major contributing factor to the spread of misinformation.

In the Netherlands, there are specific goals and building blocks for primary education including that pupils ‘learn to take care of the physical and psychological health of themselves and others’.7 In addition, there are crosscurricular themes of ‘Health’ and ‘Digital literacy’.8 The textbooks for elementary schools related to biology that were looked at for this project showed that there is limited focus on skin. Elementary schools in the Netherlands do have project work and themes such as health and body, where ‘skin’ could be included.

Optional teaching material on the skin can be found online, however, it is not clear who developed these materials

and for what purpose. Teaching materials developed by patient organisations were mostly focused on informing the child, their parents or the teacher about a specific skin condition. There are children’s books, short animations and educational television programmes about common skin problems and chronic skin conditions, but these have been developed independently of formal education.

At the congress of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology in Berlin (2023), various patient associations and medical professionals were interested in an educational programme on skin such as Skin at School. They agreed that this programme should be known and used by many children.

The aim of Skin at School is to develop and implement educational materials about skin conditions and skin care for students at primary schools, enabling them to develop knowledge and understanding, and embrace a more positive attitude to their own skin and that of other students. We intend to contribute to the empowerment of children to prevent health risks and enhance their wellbeing and resilience.

The Dutch Skin Coalition initiated Skin at School on behalf of its members,

“Across five lessons, children developed their knowledge, insight, skills and attitude towards their own skin and that of other students”

including patient associations, patient representatives and their loved ones, dermatologists and skin therapists. As an umbrella organisation, we do not possess independent financial resources. Therefore, in 2020, we submitted a grant application for patient organisations to the Dutch government to develop educational materials on skin care and skin conditions tailored for children aged eight to 12. In 2023, we submitted another grant application for the implementation of (1) the educational materials tailored for children aged eight to 12 years, (2) a specific lesson about acne and (3) the development of educational materials for children aged four to eight years. Both grant applications were approved and assigned to us. The Dutch Association for Dermatology and Venereology, along with a Dutch health insurance company (Under Your Skin Foundation and Foundation CW De Boer) provided co-funding.

To have sufficient support for the outcome of this project, it was important to involve all stakeholders. Therefore, in this project we collaborated with patient organisations, patient representatives, dermatologists, nurse practitioners, skin therapists, teachers, educational experts and children themselves. In addition,

we have partnered with the Dutch association for dermatologists, the Dutch association for skin therapists and the Under Your Skin Foundation.

We assembled a project group with three dermatologists, three teachers/ educational experts, two nursing specialists, a skin therapist and six patient representatives. We formed a junior council with six children aged eight to 12, including some who had skin conditions and some who did not.

As a result of the Covid-19 pandemic and project group members living and working far apart, the project group had online meetings.

The first phase of the project involved formulating goals for teaching materials and selecting topics. For this, we used the knowledge and experience of all project group members together with available guidelines and educational policies.

Based on the meetings, one didactical expert and the project leader worked this into a draft. This was discussed with the project group and presented to the junior council. Practical consideration was given to its feasibility at school and in the classroom. We tested our

materials on the junior council, who provided us with feedback. We also asked some teachers to test the materials at their schools, after which we made some more adjustments.

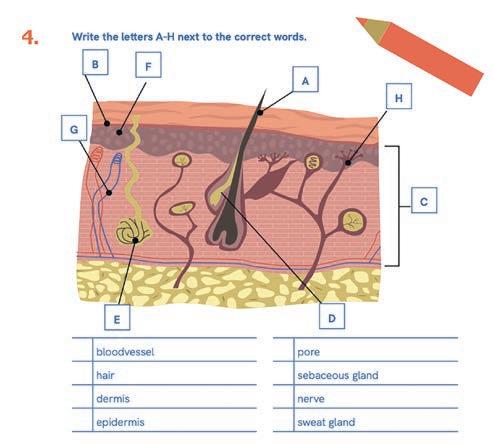

Across five lessons, children developed their knowledge, insight, skills and attitude towards their own skin and that of other students. They learn how to prevent health risks and improve their wellbeing and resilience through the activities within the curriculum. They learn about the structure and function of the skin, the similarities and differences between people’s skin, and the importance of skin care. They are educated on sun protection and preventing skin cancer, and about temporary and permanent skin conditions and their consequences (Table 1). They learn that children’s skin should not be the subject of bullying or stigmatisation.

The Skin at School programme is designed to educate children that everybody can be affected by a skin problem, ranging from temporary to lifelong. With the rise of misinformation on social media, the children also learn how to critique information they read about skin on the internet.

The lesson series consists of five lessons, with each lesson tailored to children of different ages (4-6 years, 6-8 years, 8-10 years and 10-12 years). Each lesson can be covered in 30 to 45 minutes (Table 1). The first lesson covers basic skin knowledge, including skin colour and how the skin works. The second lesson is about taking

care of the skin, such as using creams, showering, good hygiene and hand washing. In the third lesson, we focus on common skin problems such as warts, foot fungus and acne. The fourth lesson is about the risk of sunburn and how children can protect themselves from UV radiation. The fifth lesson is about chronic skin conditions (such as eczema, psoriasis and vitiligo) and what it is like to have one of these conditions.

There are four additional lesson sheets for children aged eight to 12 years. Three are on rare skin disorders such as ichthyosis, congenital naevi and vascular malformations. These sheets can be used when a child or a child’s sibling has one of these skin conditions. There is also one lesson sheet about acne for children aged 10-12, because teachers and skin therapists emphasised this as an important topic for children of this age.

The teaching materials are flexibly designed, so that teachers can decide which materials to cover with their students. We always recommend starting with Lesson 1, as this lesson contains basic concepts. After that, the other lessons can be followed in any order. To provide a safe learning environment, we

Lessons Subject

1 Basics of the skin: how the skin works

Learning objectives

Characteristics about their own skin and that of others.

The structure and function of the skin.a,b The protective function of the skin.b Possible advantages and disadvantages of washing hands with soap.a,b,c

2 Care of the skin Characteristics of skin types.a,b Hygiene and the importance of skin care. The origin and care of an abrasion.

3 Temporary skin problems like warts and acne

4 The protection of the skin against the sun

5 Long-lasting skin problems like eczema, psoriasis, vitiligo and alopecia

a For children aged 8-10 years

b For children aged 10-12 years

c For children aged 6-8 years

Common skin conditions that anyone can get.

The infectiousness of skin conditions.a,b

Skin colour types. Sunburn and protection against it. The relationship between skin and vitamin D.a,b

Chronic skin conditions.a,b,c

The effects of a chronic skin condition.a,b How to treat others with chronic skin conditions.a,b

advise holding a consultation in advance with students and parents. In the materials, students observe their own skin and the skin of their classmates to learn about similarities and differences.

The lessons are light-hearted so that students can process the material easily. There is a manual for teachers, which provides more detailed explanations. The children who can already read can work on the assignments independently or in small groups. Children also watch episodes from educational television programmes and explanations and animations via YouTube to complete assignments. In addition, we ask the older children to reflect on what they read and see, such as the impact of a permanent skin condition. Several assignments lend themselves well to classroom discussion. Each lesson begins with an assignment in which students record personal information about their own skin in their ‘skin passport’.

The teaching materials come in a cardboard case with a manual, skin passport, poster, flyer and skincoloured pencils. There is dish soap and a jar of pepper for doing an experiment. Worksheets and manuals are downloadable for free from the website, and are also available from an online Dutch primary education platform. There are 600 teaching kits distributed to schools in all provinces of the Netherlands. Teaching kits were sent upon teacher request to ensure purposeful use, avoiding random distribution to prevent potential waste.

Teachers applied for the teaching materials for various reasons: some aimed to educate about the skin, others had personal connections through their own skin conditions or a partner’s melanoma, some organised a health week, and others incorporated sun protection into their lessons. Not all schools were interested in our teaching materials and indicated that they were too busy with regular classes. It was mostly individual teachers who ordered the material because they saw possibilities for the subject they had to teach anyway or wanted to pay special attention to.

Healthcare professionals sought the kits to offer to patients or deliver guest lessons at their children’s schools. The Netherlands Association of Skin Therapists (NVH) embraced our project, collaborating on a webinar and ordering an additional 200 cases. They also decided to reward members with accreditation points for conducting guest lessons at schools, emphasising the priority of providing skin care within their professional responsibilities.

During the June 2022 Skin at School launch, Veldman spent two days at a primary school delivering guest lessons on skin to all classes and sharing her personal experiences. Collaborating with authors of children’s books about different-looking skin enriched the lessons. Veldman received compliments from teachers on the quality of our materials.

It is modern, accessible, widely applicable, didactically well put together, and aligns well with the core values of primary school education in the Netherlands. The launch of Skin at School gained additional coverage with reports from local and regional radio. A teacher with almost 2,000 followers on Instagram created a great video about our teaching materials and as a result, over 100 requests for the teaching materials came from other teachers.

We actively promoted Skin at School within patient associations, featuring a booth at the 2022 Dutch World Eczema Day organised by the

eczema patient association. During the event, positive feedback came from children and patients who expressed appreciation for the initiative. Emotional responses were noted, with some individuals saying they wished such lessons existed in their youth. The profound impact of childhood experiences where differences led

to social exclusion were shared. Our teaching materials extended their reach to family meetings of various patient associations, including vitiligo, psoriasis, congenital naevi, vascular malformations, and ichthyosis. Further visibility was achieved through mentions on websites, newsletters, and patient magazines.

“We actively promoted Skin at School within patient associations, featuring a booth at the 2022 Dutch World Eczema Day”

To engage dermatologists, we reached out to the Association for Dermatologists in the Netherlands, published articles in magazines, and posted on LinkedIn. Our presence at the annual symposium for paediatricians and dermatologists allowed us to deliver a presentation on our educational materials, ensuring awareness among these medical

professionals. Many dermatologists and paediatricians are informed about Skin at School and how it offers a valuable resource for children and parents facing skin-related bullying and for those seeking guidance on discussing skin conditions. Flyers in various hospitals and GP practices further disseminated information to children and their parents.

Teacher: ‘I myself have skin problems/a chronic skin condition and one of the students had a chronic skin condition, which allowed us to explain together what it does to your skin and your life.’

Teacher: ‘I think it is very important that children learn about their skin and the different skin types. In addition, it is important that they learn, especially in primary school, about protecting the skin.’

Teacher: ‘Children think it is boring to talk about skin, but you have included social media. This makes it more interesting’.

Parent: ‘Thank you for this interesting material! My child was anxious to talk about his eczema, but during the lessons it turned out he was not the only one in his class!’

Skin therapist: ‘The children really enjoyed the lesson and actively started applying sunscreen.’

Skin therapist: ‘Nice way to offer a lesson in schools, the teaching materials are well put together.’

During implementation, our team utilised social media, disseminating messages on LinkedIn, raising awareness among patient representatives, healthcare professionals, teachers, and educational experts. Our Instagram account successfully reached numerous teachers and skin therapists, providing regular informative posts about the teaching material’s content. Relevant hashtags facilitated discovery by teachers, patients, and patient organisations, fostering engagement and visibility.

In total, 700 teaching kits have been distributed to schools in 170 different cities in the Netherlands. We could not record on the website how many times the materials were downloaded. Our evaluation form was completed by 24 skin therapists who gave guest lectures at schools (70%), teachers (26%) and a parent of a child with a skin condition (4%). In Figure 1 you can see which lessons were taught.

All the respondents mentioned positive aspects about the learning material. For example, that it is interactive, developed clearly and

at the right level, nicely designed, and that assignments were easy to use. Some of them provided advice for improving lessons, such as simplifying the skin passport (less cutting and folding), creating standard presentations for guest teachers by topic, and adding sunscreen to the teaching kit.

Discussion

We have succeeded in implementing educational materials about the skin, skin care and skin problems throughout the Netherlands. The collaboration between various healthcare professionals, educational professionals, patient representatives and a junior council allowed the materials developed to be well placed to achieve the aims of Skin at School.

The strength of the Skin at School material lies in its focus not only on children with skin problems but on all children. Everyone has skin that requires proper care. Through knowledge and understanding of your own skin, you discover that everyone can develop common skin problems, and some individuals have a permanent skin condition. The teaching material is also inclusive regarding skin colour.

Our project team’s analysis showed that teaching material about the skin was scarce and the quality was unclear. Most of the material available focused on children with a specific skin condition. Our materials align with educational policy and current affairs related to information literacy and assessing of health information.7,8 Children can be exposed to fake news or misinformation through social media or prominent individuals who make claims, such as the use of sunscreen.5,6 Education can play a crucial role in preventing health risks.

Our teaching materials can be utilised by teachers themselves. Schools have the option to use a guest teacher, or they can choose to teach the material independently. The teaching materials are available for free by digital download or print. Some teachers may find it challenging to broach the

subject of having a skin condition, and Skin at School is designed to make these conversations easier. We are now mainly contacting teachers who are interested in the subject or looking for teaching materials, as some schools feel they are too busy with regular classes. Therein lies a challenge for us to bring the programme to the attention of all schools and implement it.

The Netherlands is a multicultural society with diversity in skin tone. Of the 17.5 million inhabitants, 14% came to the Netherlands as migrants and 11% were Dutch-born children of migrants. 8 There was no data available on how many people have skin of colour. With our programme, we aim to show children both the similarities and differences in skin tones. We provide them with a set of pencils representing various skin tones from around the world, not limiting it to the commonly used salmon pink, which is often considered a default skin colour by those with white skin. Our lessons are inclusive, covering all skin tones, and we aim to educate children about the consequences of stigmatisation.

In addition, we see it as our responsibility to teach children at a young age to protect themselves from sunburn. Children are at a high risk of developing skin cancer later in life, but they may not be aware of it. Many people do not realise that sunburn during childhood can lead to skin cancer in adulthood. By setting a good example early on in life, we can hopefully encourage healthy behaviours that will last long into adulthood. By doing so, we can influence how many children develop skin cancer. 9

One limitation of our project is that due to limited funding, we have not been able to investigate the effect of our teaching materials on knowledge, attitudes and behaviours. We need to acquire additional funding to investigate the programme’s impact, and to translate our teaching materials to other languages so it can be used in countries other than the Netherlands.

Skin at School has been successfully developed and implemented and the feedback we have received has been largely positive. Further research on the impact of this programme is needed.

1. Ablett K, Thompson AR Parental, child, and adolescent experience of chronic skin conditions: a meta-ethnography and re- view of the qualitative literature. Body Image 2016.19:175–185

2. Golics CJ, Basra MK, Finlay AY, Salek MS. Adolescents with skin disease have specific quality of life issues. Dermatology. 2009;218(4):357-66.

3. Holm EA, Wulf HC, Stegmann H, Jemec GB. Life quality assessment among patients with atopic eczema. Br J Dermatol. 2006 Apr;154(4):719-25.

4. De Groot, J, Kramer-Noels, E. Nationaal actieplan huidkanker. Stuurgroep Huidkankerzorg Nederland; 2021 April.

5. Joshi, M, Korrapati, NH, Reji F, Hasan, A, Kurudamannil RA. The Impact of Social Media on Skin Care: A Narrative Review. Lviv Clinical Bulletin. 2022, 1(37)-2(38):85-96.

6. Borba, AJ, Young, P.M, Read, C. Armstrong, A. Engaging but inaccurate: A cross-sectional analysis of acne videos on social media from non–health care sources. JAAD. 2019 Aug;83(2):610-612.

7. Greven J, Letschert J. Kerndoelenboekje basisonderwijs. Den Haag: Ministerie van Onderwijs, Cultuur en Wetenschap; 2006 April.

8. Curriculum.nu. Samen bouwen aan het primair en voortgezet onderwijs van morgen. Curriculum.nu; 2019 Oktober.

9. CBS. Hoeveel inwoners van Nederland zijn in het buitenland geboren? Retrieved from https://www.cbs.nl/nl-nl/visualisaties/ dashboard-bevolking/herkomst [Accessed May 2024]

10. Baig IT, Petronzio A, Maphet B, Chon S. A Review of the Impact of Sun Safety Interventions in Children. Dermatol Pract Concept. 2023 Jan 1;13(1)

The authors would like to thank the following people for their contribution to the project: Dermatologists Shiarra Stewart, Kirsten Vogelaar-Burghout and Suzanne Pasmans, and all of the patient representatives and educational experts.

KLISYRI® (tirbanibulin) is indicated for the field treatment of non-hyperkeratotic, non-hypertrophic actinic keratosis (AK, Olsen grade 1) of the face or scalp in adults.1

WELL-TOLERATED FIELD THERAPY2 NOVEL MoA1,2

KLISYRI® (TIRBANIBULIN) PRESCRIBING INFORMATION

Please consult the Summary of Product Characteristics (SmPC) before prescribing. Klisyri 10 mg/g ointment Active Ingredient: Each gram of ointment contains 10 mg of tirbanibulin. Each sachet contains 2.5 mg of tirbanibulin in 250 mg ointment. Excipients with known effects: Propylene glycol 890 mg/g ointment Indication: Klisyri is indicated for the field treatment of non-hyperkeratotic, non hypertrophic actinic keratosis (Olsen grade 1) of the face or scalp in adults. Dosage and Administration: Tirbanibulin ointment should be applied to the affected field on the face or scalp once daily for one treatment cycle of 5 consecutive days. A thin layer of ointment should be applied to cover the treatment field of up to 25cm2 Consult SmPC and package leaflet for full method of administration. Contraindications, Precautions and Warnings: Contraindications: Hypersensitivity to the active substance or to any of the excipients listed in section 6.1 of SmPC. Precautions: Contact with the eyes should be avoided. Tirbanibulin ointment may cause eye irritation. In the event of accidental contact with the eyes, the eyes should be rinsed immediately with large amounts of water, and the patient should seek medical care as soon as possible. Tirbanibulin ointment must not be ingested. If accidental ingestion occurs, the patient should drink plenty of water and seek medical care. Tirbanibulin ointment should not be used on the inside of the nostrils, on the inside of the ears, or on the lips. Application of tirbanibulin ointment is not recommended until the skin is healed from treatment with any previous medicinal product, procedure or surgical treatment and should not be applied to open wounds or broken skin where the skin barrier is compromised. Local skin reactions in the treated area, may occur after topical application. Treatment effect may not be adequately assessed until resolution of local skin reactions. Due to the nature of the disease, excessive exposure to sunlight (including sunlamps and tanning beds) should be avoided or minimised. Tirbanibulin ointment should be used with caution in immunocompromised patients. Changes in the appearance of actinic keratosis could suggest progression to invasive squamous cell carcinoma. Propylene glycol may cause skin irritation. Consult SmPC and package leaflet for more information. Fertility, pregnancy and lactation: No human data on the effect of tirbanibulin ointment on fertility are available. Tirbanibulin

Reference: 1. KLISYRI® SmPC. Almirall. 2. Blauvelt A, et al. N Engl J Med. 2021;384(6):512-520. 3. Schlesinger T et al. Skin, 2023: 7(3); 771-787. PROVEN EFFICACY2 CONVENIENT SHORT TREATMENT COURSE1

ointment is not recommended during pregnancy and in women of childbearing potential not using contraception. It is unknown whether tirbanibulin/metabolites are excreted in human milk. A risk to the newborns/infants cannot be excluded. Consult SmPC and package leaflet for more information. Adverse Reactions: Very common (≥1/10): Application site - erythema; exfoliation; scab; swelling; erosion. Common (≥1/100 to <1/10): Application site - pain, pruritus and vesicles. Consult SmPC and package leaflet for further information. Legal Category: Ireland: POM Subject to prescription which may not be renewed (A). United Kingdom & Northern Ireland: POM Price: Ireland: Price to wholesaler United Kingdom & Northern Ireland: UK NHS Cost: £59.00 (excluding VAT). Marketing Authorisation Numbers: Ireland and Northern Ireland: EU/1/21/1558/001 Great Britain: PLGB 16973/0043 Marketing Authorisation Holder: Almirall, S.A., Ronda General Mitre, 151 08022 Barcelona, Spain Further information available from: Almirall Limited, Harman House, 1 George Street, Uxbridge, Middlesex, UB8 1QQ, UK. Date of First Issue: August 2021 Item code: IETIRBA-2100011 Complete information on where to find reportingforms and information for adverse events search MHRA Yellow Card in the Google Play or Apple App Store.

UK and UK(NI)-Adverse events should be reported. Reporting forms and information can be found at MHRA https:// yellowcard.mhra.gov.uk Adverse events should be also reported to Almirall Ltd. Tel. 0800 0087 399

IE-Adverse events should be reported. Reporting forms and information can be found at HPRA Website: www.hpra.ie. Adverse events should be also reported to Almirall Ltd. Tel. +353 (0) 1431 9836

Soothe, hydrate and comfort dry skin around the delicate eye area

sensitive, irritated eyelids or for those with eyelid eczema

Helps to relieve eyelids that are:

to find out more

EPIMAX® Eyelid Ointment is available for patients to buy OTC and online

EPIMAX® Eyelid Ointment Product Information

Presentation: Ointment in 4g tube Main ingredients: Yellow soft paraffin 80%, liquid paraffin 10% and wool fat (lanolin) 10%. Indications: Soothing moisturiser for dry, itchy, red, and flaky eyelids. Method of use: Apply to the eyelid skin as frequently as required. Warnings: For external use only. Avoid contact with eyes. If product does accidentally come in to contact with eyes, rinse well with water and seek medical advice. Do not use if allergic to any of the ingredients. This product contains lanolin, which may cause local skin reactions or allergic reactions. Seek medical advice before use if the skin is broken, infected, or bleeding; or after use if any undesirable effects are experienced, or if accidentally swallowed. No special precautions during pregnancy or breast-feeding. Contraindications: Patients with known hypersensitivity to any ingredient. Product classification: Class I Medical Devices. Cost: RRP: £9.95 NHS List Price: £2.35 Legal Manufacturer: Aspire Pharma Ltd, Unit 4, Rotherbrook Court, Bedford Road, Petersfield, Hampshire, GU32 3QG, UK. Date reviewed: March 2023 Version number: 10104511504 v 2.0

Adverse events should be reported. Reporting forms and information can be found at www.mhra.gov.uk/yellowcard. Adverse events should also be reported to Aspire Pharma Ltd on 01730 231148.

Please advise your patients to always read the label

Stephanie Greenleaf

Phototherapy is a vital treatment for various dermatological conditions including psoriasis, eczema and vitiligo.1 Over the past seven years, I have had the privilege of setting up and leading a phototherapy unit in an acute hospital in Southwest London. This role has not only fuelled my passion for dermatological nursing but also allowed me to engage deeply with both the operational and educational aspects of service provision.

My journey started in a small unit with one nurse and has expanded into a comprehensive service offering extensive treatment options to our local population and surrounding area of patients. This expansion was guided by strict adherence to the British Association of Dermatologists’ (BAD) phototherapy service guidelines and the St John’s Phototherapy Guidelines.2,3 The guidance supports implementation of high standards for patient care and safety. There was an agreed narrative of ensuring excellent leadership, incorporating trust values by addressing staff development through training and access to learning with an overarching aim to build a team, capable of delivering exceptional care to our dermatological patients.4

My role as phototherapy lead has naturally developed. Alongside the managerial aspect, I provide education to junior doctors, student nurses and nursing staff. The opportunity to teach and mentor others has been profoundly rewarding and continuously reinforces my commitment to nurturing the next generation of phototherapy and dermatology professionals.

This aspect of my work led to an invitation from my clinical lead Emma Button to present at the prestigious BDNG Manchester 2024 Meeting, which I proudly accepted.

Preparing for the two-day BDNG meeting involved extensive research to ensure relevant, current and correct information was shared. The meeting covered a wide range of topics within phototherapy designed to engage a diverse audience of professionals. I utilised the BAD Service Guidance and Standards for Phototherapy Units to ensure current and relevant information was used throughout

This article provides an overview of implementing phototherapy guidelines and practices within a clinical setting, considering the importance of education to enhance patient outcomes and streamline services. Additionally, it details how the development of a comprehensive training programme can also improve staff proficiency in line with the NMC Code (2018). The insights shared are drawn from my leadership experience in a phototherapy unit, firsthand observations, and feedback from the attendees at the British Dermatological Nursing Group (BDNG) Manchester 2024 Meeting.

The discussion covers the integration of best practices, the evolution of patient experience and the impact of continuous professional development on treatment efficacy. Reference is also made to the St John’s Phototherapy Guidelines, (2009), which inform best practice by providing detailed protocols and safety measures for the effective and safe use of phototherapy in treating dermatological conditions. Although there are numerous other UK phototherapy guidelines, time constraints limited their use within the meeting.

Keywords:

Phototherapy, Education, Professional Development, BDNG Manchester Meeting

Author info:

Stephanie Greenleaf, Clinical Nurse Specialist Lead for Phototherapy, West London NHS Trust.

Citation: Greenleaf, S. Expert consensus on the systemic treatment of atopic dermatitis. Dermatological Nursing 2024. 23(4):19-23.

the meeting as well as the Nursing and Midwifery Council (NMC) Code (2018) to guide best practices in nursing. In doing so, I was able to deliver a comprehensive timetable of subjects offering relevance and interest to all those working within the phototherapy field.

This process allowed me to creatively convey complex information in an accessible format.5 However, integrating technology such as digital tools into ‘classroom’ tasks would have significantly enhanced learning by promoting oral presentations and collaborative group activities.6

I encourage phototherapy nurses to engage and embrace educational activities, as through personal reflection I am able to advise on personal growth and discovery, shaping my professional practice and reinforcing my commitment to advancing phototherapy nursing through continuous learning and teaching.7

The BDNG meeting provided an update and refresh in education for both me and the nurses in attendance. Reflection is deeply integrated into our practice through revalidation and appraisals, which mandate dedicated time for self-development.8

The feedback from the BDNG meeting was collected through a set of questions answered by participants. This feedback offers a comprehensive understanding of the meeting’s impact and areas for improvement.

The data presented below reflects the overall satisfaction levels, the effectiveness of the presentations and the value of the meeting, highlighting both strengths and opportunities for further enhancement.9

Q1. How did you hear about this event?

The data from 62 respondents shows that 40.32% heard about the meeting through colleagues, underscoring the power of word-of-mouth in professional networks. The BDNG website was the next most common source at 37.10% followed by email notifications at 19.35%.

“Reflection is deeply integrated into our practice through revalidation and appraisals, which mandate dedicated time for self-development.”

A small fraction (3.23%) received information via other means, such as personal anticipation and department managers and no respondents used postal mail.

These insights emphasise the importance of interpersonal communication and official online platforms for effective information dissemination and could help in planning future communication methods to ensure maximum reach and effectiveness.

Q2. Who paid your registration fee?

The data indicates that 66.13% of respondents had their registration fees paid by employers, highlighting strong organisational support for professional development. This suggests employers value their employees’ participation and are keen to invest in their growth, enhancing job performance and satisfaction.

Meanwhile, 30.65% of respondents paid their fees themselves, showing high personal commitment to professional development but also suggesting some employers do not provide financial support for these activities. A small number (3.23%) had their fees covered by third parties, such as sponsors or grants, indicating alternative funding options exist.

Q.3 Who paid your travel costs?

Just under two thirds (64.52%) of respondents had their travel costs paid by their employer, while 32.26% paid their own costs and 3.23% were covered by third parties. This indicates strong employer support for professional development. However, the significant number of self-payers suggests substantial personal commitment and

highlights a gap in employer support, potentially due to budget constraints or policies. The presence of thirdparty payments, though minor, points to alternative funding sources such as sponsorships and grants.

Q4. Did you receive study leave to attend this meeting?

Nearly all (96.77%) respondents received study leave to attend the meeting, showcasing strong organisational support for professional development. Only 3.23% did not receive study leave which may be due to company policies or staffing issues.

This high level of support suggests a positive organisational culture which prioritises continuous educational and professional growth, leading to increased employee satisfaction and retention. However, the small percentage not receiving leave highlights potential areas for improvement, such as exploring flexible solutions for inclusivity in professional development. Overall, the data reflects positively on organisational practices and underscores a commitment to employee growth.

Q5. Please evaluate each presentation

The evaluation data for the presentations, categorised as ‘Excellent’, ‘Good’, ‘Average’, or ‘Poor’, show that high ratings were generally received, with most responses falling under ‘Excellent’ or ‘Good.’

What is phototherapy?

An overwhelmingly positive evaluation with 64.41% of respondents rating this talk as excellent and 30.51% rating it as good. Only 5.08% rated the presentation as average and none rated it as poor. This suggests that the explanation of phototherapy was both

clear and comprehensive, effectively meeting the audience’s expectations and educational needs.

This presentation was well-received with 57.63% of respondents rating it as excellent, 37.29% as good and 5.08% as average. No poor ratings were received. This suggests that the presentation effectively conveyed a strong understanding of conditions responsive to phototherapy, meeting the audience’s expectations and educational needs.

Patient assessment/the patient journey

Results show positive feedback with 55.93% of respondents rating the talk as excellent and 38.98% as good. Only 5.08% rated it as average, and none rated it as poor. This reflects effective communication of the patient assessment processes and the journey through treatment.

Treatment protocols

Nearly half (49.15%) of respondents rated this talk as excellent and 45.76% as good, with only 5.08% rating it as average and none rating it as poor. This suggests that the presentation provided clear and useful treatment guidelines.

Patient safety

This talk also received very positive feedback with 59.32% of respondents rating it as excellent and 37.29% as good. Only 3.39% rated it as average and none rated it as poor. These high ratings indicate that the presentation effectively conveyed vital information on maintaining patient safety.

Photosensitising drugs

This talk was well-regarded with 49.15% of respondents rating it as excellent and 44.07% as good. In total, 6.78% rated it as average and none rated it as poor. This indicates that the information was thorough and effectively communicated, successfully meeting the audience’s needs and expectations.

MED/MPD testing

Just over half (50.85%) of respondents rated this talk as excellent, 38.98% as good, 10.17% as average and none as

Evaluation data for the presentations (Q5)

Photo-responsive dermatoses

Patient assessment/the patient journey

Treatment protocols

Patient safety

Photosensitising drugs

MED/MPD testing

Protective measures

When to seek advice

Discharge of patients

Service standards

Phototherapy in children

Safe calculations

Competences

Topical treatments

% of respondents

poor. These ratings suggest that the presentation clearly communicated the procedures and importance of these testing methods for these critical components in phototherapy.

High ratings were received for this talk, with 57.63% of respondents rating it as excellent and 33.90% as good. A smaller proportion (8.47%) rated it as average and none rated it as poor indicating that the audience found the information valuable and well-communicated, with the talk effectively addressing the importance of protective measures in ensuring safe and effective phototherapy treatments.

A well-received presentation, with 55.17% of respondents rating it as excellent and 37.93% as good. A small percentage (6.90%) rated it as average

and none rated it as poor. This indicates that the information on when to seek additional advice, support and guidance was clearly conveyed to the audience.