Revision of the New Legislative Framework (NLF)

Public Consulation

January 26, 2026

Summary

The New Legislative Framework (NLF) is one of the EU’s most successful and influential regulatory systems It forms the foundation of the European Single Market, having played a key role in transforming a previously fragmented landscape of national markets into a unified European market in which goods can move freely across borders. The system is highly relevant for a strong and competitive industrial base. We therefore support a targeted revision of the NLF to address current and future challenges.

The following priorities are essential for us:

▪ The revision of the Standardisation Regulation (EU) No 1025/2012 must be closely aligned with the revision of the NLF to ensure a coherent regulatory framework. Harmonised European standards must continue to serve as the instrument for presumption of conformity under EU legislation. They should primarily be based on international standards, and the overall process from the standardisation request through drafting, assessment and citation must be accelerated and optimised.

▪ Harmonisation of definitions and terminology must be implemented consistently to ensure legal certainty and coherence across the EU legal framework. The model provisions of Decision 768/2008/EC should be applied without modifications, and any deviations should in future only be permitted if explicitly justified in the recitals.

▪ The review of conformity assessment procedures should retain the existing NLF module system in its current form and significantly expand the freedom to choose Module A, in order to avoid unnecessary regulatory burdens. Furthermore, we call for a shift away from the trend towards mandatory third party certification and towards a risk based approach to conformity assessment, enabling an efficient use of skilled professionals and strengthening market surveillance.

▪ Accreditation and conformity assessment must be further harmonised across Europe. The existing prohibition on competition between national accreditation bodies must be strictly upheld to maintain quality, transparency and international compatibility. At the same time, protecting sensitive data and ensuring sustainable financing is essential to support digitalisation, new areas of work and long term performance of the accreditation system.

▪ The introduction of an interoperable and technologically neutral Digital Product Passport (DPP) must be done in gradual, pragmatic steps and in close cooperation with industry, keeping the administrative burden particularly for SMEs as low as possible. Clear rules on data provision, data security and access must be defined. Sensitive data should only be provided upon justified request.

▪ We call for significantly stronger and better coordinated market surveillance, supported by improved resources, harmonised EU level structures and clear responsibilities, particularly in online trade. This is crucial to ensure effective enforcement and prevent distortions of competition. We also advocate for a closer coordination with customs authorities, full use of Union Testing Facilities, strengthened sanctions for repeated violations and a mandatory enforceability assessment for new legislative acts.

▪ An exemption for spare parts within the scope of the NLF is required to support repairability and sustainability objectives. This exemption should be based on Regulation (EU) 2024/2847 (CRA), Article 2(6), and follow the “repair as produced” principle.

▪ In the field of circular economy, we call for a coherent and legally certain framework for remanufacturing and refurbishment one that clarifies responsibilities, eliminates conflicting requirements across different legal acts and strengthens circularity. This requires clear labelling obligations, flexible delegated acts under the ESPR, a risk based application of only the relevant legislation, and protection of intellectual property while maintaining full manufacturer responsibility for remanufacturers.

Background

The NLF builds on the “New Approach” introduced in the year 1985 and further developed as well as legally anchored in 2008. Since then, the NLF has served as the central regulatory framework governing the placing of industrial products on the market in the EU, forming the foundation for the free movement of goods within the European Single Market.

The system is based on the following fundamental basics, which should be maintained for the future:

Harmonisation of product regulations: The NLF provides legislators with a toolbox of horizontal provisions and measures designed to harmonise EU product legislation across sectors and ensure coherence. This includes horizontal definitions of terms commonly used in product regulation ranging from economic operators such as manufacturers, importers, distributors and authorised representatives to their respective obligations. This harmonisation has helped transform what was once a fragmented landscape of national markets into a unified European market in which goods can move freely across borders.

Cooperation between legislation and standardisation: The NLF regulatory system is based on a clear separation between legal acts that set out the essential product requirements and standardisation, which provides voluntary technical solutions. This approach ensures a high level of protection while offering the flexibility needed to adapt to continuous technological change and to remain internationally competitive.

Conformity assessment: The NLF harmonises conformity assessment procedures. Before a product is placed on the market, manufacturers must demonstrate that it meets the essential requirements of the relevant EU product legislation. Depending on the classification, manufacturers may, for most products, issue an EU Declaration of Conformity themselves (under Module A) and affix the CE marking without third party involvement.

Enforcement of legal requirements: A core element of the overall product compliance system, built on the principle of manufacturer responsibility, is market surveillance. National authorities perform checks either on a sampling basis or risk based to ensure compliance with essential product requirements. They are also obliged to cooperate and exchange information to maintain high levels of protection and ensure a level playing field across the EU.

The NLF creates a common framework for industry and authorities, which combines free trade with high safety standards, supports market integration and fosters growth. Moreover, the alignment of technical requirements set out in standards with essential safety requirements established in legislation ensures mutual understanding among authorities, manufacturers and consumers. Since its introduction in 2008, the product landscape has evolved profoundly driven by digitalisation and new lifecycle wide requirements. This creates an opportunity to modernise the regulatory framework in a targeted manner without departing from its proven principles, and to adapt the system to both current and future challenges.

In the following, we will comment on the options proposed by the European Commission, provide additional suggestions and explain the underlying reasoning

1. Coherence between the NLF and Standardisation

The Standardisation Regulation (EU) No 1025/2012 constitutes a central pillar of the NLF. The separation between essential requirements defined in EU legislation and their technical specification through harmonised European standards (hEN) enables a practical, technology neutral regulatory approach. This structure is therefore a fundamental prerequisite for ensuring that Europe remains an attractive and competitive industrial base. For this reason, the revision of the Standardisation Regulation should be closely aligned with the revision of the NLF to guarantee a coherent regulatory framework. The following elements are of particular importance to German industry:

The performance of the system depends on the timely availability of standards at the moment the corresponding legislation enters into force. Since the current timelines for making hEN available neither meet market needs nor reflect international competitive pressures, the entire process from the standardisation request, development and assessment to citation must be accelerated and optimised.

Harmonised standards must continue to serve as the primary instrument for presumption of conformity within the framework of EU legislation. The use of Common Specifications should not become an alternative to the NLF and the European standardisation system; rather, they should be considered only in strictly defined and sufficiently justified exceptional circumstances.

Considering recent court rulings, it is essential to clarify the legal status and formal requirements of hEN in order to resolve existing legal uncertainties. It must be reaffirmed that harmonised standards are technical specifications reflecting the state of the art and that their application remains voluntary. They must not be equated with binding legal acts.

Standards are a strategic instrument. Harmonised standards are particularly system relevant, as they translate essential safety objectives of EU legislation into technical requirements. For strategic and security related reasons, standardisation requests issued by the European Commission for the development of hEN must continue to be directed exclusively to the recognised European Standardisation Organisations listed in Annex I of Regulation (EU) No 1025/2012. We firmly reject any direct allocation of standardisation requests to organisations from third countries.

The revision of the Standardisation Regulation must be considered in both a European and an international context. For the global competitiveness of European industry, it is crucial that technical requirements are designed in a globally aligned manner. Accordingly, hEN should, wherever possible, based upon existing international standards. Maintaining international alignment, including the established cooperation with ISO and IEC, is essential.

2. Harmonisation of Definitions and Terminology

We welcome the efforts to harmonise the definitions used across different legal instruments in particular between the NLF and Regulation (EU) 2019/1020 on market surveillance. Clear and consistent terminology significantly improves legal certainty. Wherever possible, definitions should be applied uniformly in order to avoid unnecessary room for interpretation and inconsistent implementation across the EU.

This alignment should go beyond definitions alone. The legislative template for product regulation set out in Decision 768/2008/EC has successfully harmonised core elements across currently 30 regulations under the NLF. The established practice of regulatory alignment through the consistent application of the model provisions and definitions of Decision 768/2008/EC should be maintained without modifications. This principle should also extend to legislative instruments originally introduced in non harmonised acts (outside the NLF) and subsequently replicated across other regulations. Such an approach would improve regulatory consistency and legal clarity throughout the body of EU legislation.

A current example where this approach has failed: The AI Act (Art. 3(14)) defines a safety component in broadly functional terms, including any component whose failure may endanger health, safety or property. By contrast, under the Machinery Regulation (Art. 3(3)), a safety component performs safety functions exclusively for persons, applies only to components placed independently on the market, are not necessary for the basic functions of the product. These divergent scopes create uncertainty for manufacturers and conformity assessment bodies when classifying AI supported machine elements. Such inconsistencies risk fragmenting conformity approaches and undermining coherence within the NLF

Proposal for addressing this issue in the future NLF (Article 2 of Decision 768/2008/EC should be expanded as follows):

“Where Union law departs from the general principles and provisions of Annexes I, II and III or from other previously established legal principles, a recital shall be required to justify and explain the deviation. The legislator and the European Commission, in its role as guardian of the Treaties, shall ensure that only necessary deviations are introduced and that no deviation from the model provisions remains unexplained in a recital.”

We are convinced that the legislative process becomes significantly more efficient and produces better outcomes if every deviation from the template must be explicitly explained.

The extension of these definitions to digital products in particular requires a thorough analysis of their technological characteristics and risks. In order to avoid future inconsistencies such as the divergence in the notion of a safety component between the AI Act and the Machinery Regulation a systematic examination of the applicability of key NLF definitions to novel product categories is essential.

Furthermore, the European regulatory framework should increasingly draw on internationally standardised definitions and terminology, as this structurally strengthens Europe’s export oriented economy by facilitating compliance with global requirements.

3. Strengthening Manufacturer’s Self Declaration (Module A)

Industry, notified bodies and market surveillance authorities have extensive experience with the currently available modules. In their present form, these modules have created a high level of legal certainty and facilitated access to the Single Market for increasingly complex and safer products, many of which fall under multiple NLF regulations. To preserve these achievements and avoid unnecessary burdens, the existing set of modules should be retained without amendments or additions.

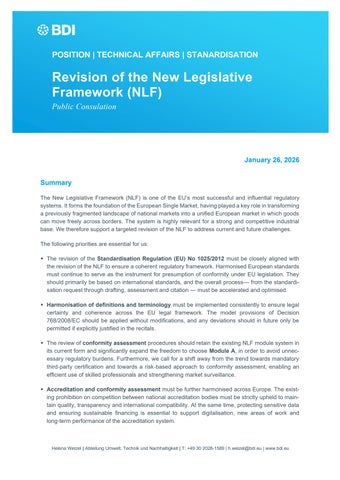

However, a realignment of the NLF and its harmonised legal acts is essential (see Figure 1). To reduce regulatory burdens, industry requires a significantly expanded possibility to choose Module A, as set out in Annex II of Decision 768/2008/EC commonly referred to as “conformity assessment by the manufacturer” . This procedure has enabled companies to place products on the European market efficiently and safely. Applying Module A in conformity assessment allows new technical solutions and innovations to reach the market quickly while ensuring the timely availability of tailored solutions. This must be accompanied by strengthening the capacity of market surveillance authorities.

Figure 1 – Triangle illustrating the balance between manufacturer’s conformity assessment (Module A), market surveillance and mandatory third party assessment by notified bodies (remaining modules).

The introduction of Module A has facilitated market access, while the overall high level of safety of technology in Europe has continued to improve. Technology developed in Europe, already starting at a high level, becomes safer over time. However, recent legislation increasingly favours mandatory third party certification. Given Article 4(1d) of Decision 768/2008/EC which states that legislators should avoid prescribing modules that are disproportionate to the risks covered by the legislation a reversal of this trend is urgently required, aligning the choice of conformity assessment modules with the actual risk of the products concerned (see Figure 1). This need is even more acute in view of the continuous evolution of the state of the art, demographic developments and the shortage of engineers across Europe.

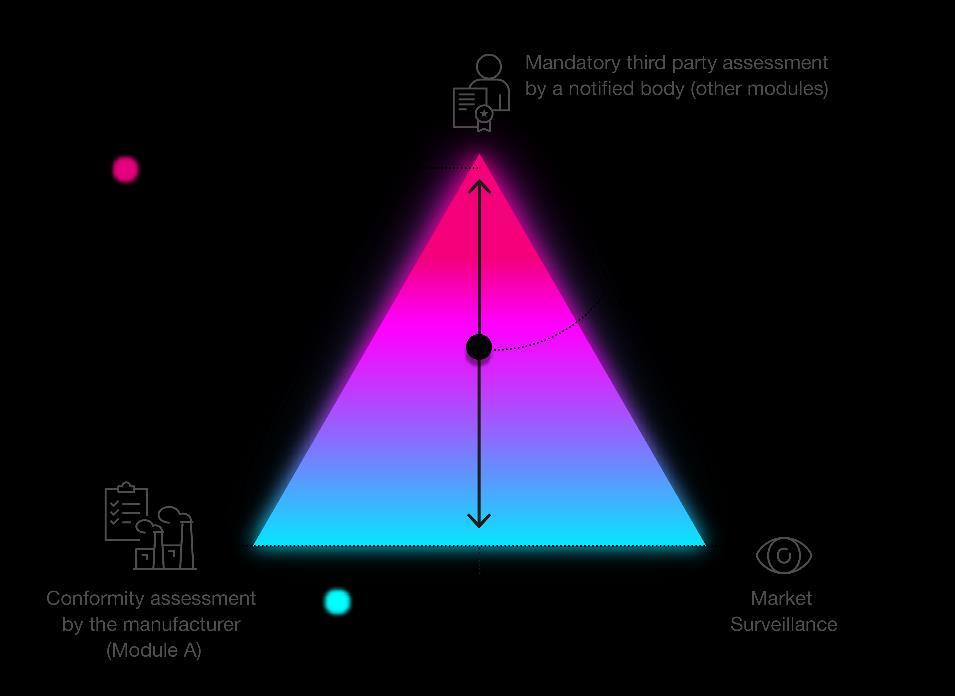

Expanding mandatory third party assessments will reduce productivity, as scarce engineering expertise is diverted from corporate innovation departments to external notified bodies. This technical

expertise would then also be lacking within market surveillance authorities, consequently weakening this essential governmental function. Regardless of which modules are required under the NLF legislation, both industry and market surveillance must constantly adjust workforce capacities to ensure compliance. In contrast, legislators can directly influence the required size of the workforce for third party conformity assessment by enabling or restricting the use of Module A (see Figure 2).

This problem becomes particularly severe where limited resources and qualifications, a small number of notified bodies and the absence of supporting standards coincide significantly increasing the risk of divergent assessments.

Figure 2 – Areas in which STEM professionals are required to ensure the functioning of the NLF.

In the interests of simplification, enforceability and reduced regulatory burden, we call on the European Commission to enhance the application of Article 4(1d) of Decision 768/2008/EC in order to strengthening competitiveness and make greater use of the conformity assessment by the manufacturer. To adjust existing legislation, an “omnibus for simplifying conformity assessment” should be launched focusing exclusively on reviewing requirements for third party modules.

Furthermore, in some harmonised legal acts such as the Machinery Regulation the use of Module A is tied to the availability of harmonised standards. This obligation should be explicitly lifted where citation in the OJEU is missing

4. Conformity Assessment Bodies and Accreditation

Accreditation is a key instrument for ensuring the competence of conformity assessment bodies (CABs) and is therefore essential for quality assurance, consumer protection and international competitiveness. The European Co-operation for Accreditation (EA) the association of national accreditation bodies in Europe must be strengthened, and accreditation advanced consistently Divergent national regulations must be carefully reviewed and avoided wherever possible to ensure uniform market conditions and international alignment.

The principle of flexible accreditation should be supported to make efficient use of technical expertise and reduce administrative burdens. To further reduce bureaucracy, the introduction of a workable multi-site accreditation system (systemically cross-site while technically site-specific) should be examined. It must, however, be ensured that national accreditation bodies are not pushed into competition with one another. The systemic and organisational part of multi-site accreditation must be conducted exclusively in the Member State in which the company seeking accreditation has its headquarters, and only by the national accreditation body responsible in that state. This presupposes that companies have not relocated their headquarters to another Member State within the previous 24 months. The technical part, however, must take place in the Member State where the accredited site is located. To safeguard harmonisation across Europe, the EA must be granted the authority to intervene where necessary. In this context, the obligation for regular audits conducted by national notifying authorities should be reviewed and, where appropriate, aligned at European level.

Within the broader goal of harmonisation and efficiency, options should also be examined to allow notified bodies, while maintaining quality standards, to obtain a simplified multi scope designation. This requires that procedures remain transparent, traceable and coordinated at EU level without creating parallel systems or additional national requirements. Again, national deviations must be avoided, and alignment with harmonised European rules must be ensured through EA coordination.

Governance structures at European level must be clearly defined and efficiently organised, avoiding any additional parallel structures to those that already exist. The involvement of stakeholders from industry, the public sector and science in the strategic committees of accreditation organisations is essential to ensure practical relevance and acceptance. Evaluation committees, ombuds offices and customer advisory boards should be systematically established to enable structured feedback and continuous improvement. EA has already created such an advisory board at European level, including representatives of national authorities, conformity assessment bodies and industry; this board must be maintained in its current composition and function.

Disclosure of subcontractor structures outside the European Union is necessary to ensure transparency and protect sensitive corporate data. The sale of CABs should be regulated, for example by a right of first refusal for EU-based companies. At the same time, mandatory third party assessments should be critically reviewed and avoided wherever they do not provide clear added value for quality assurance.

A reliable and sustainable financing system for accreditation organisations is required to avoid economically driven disincentives and to enable investment in digitalisation and new areas such as AI. Such financing must allow for long term project planning and ensure that new requirements can be integrated into accreditation practice at an early stage.

5. Digital Integration through a Mandatory Digital Product Passport (DPP)

The Digital Product Passport (DPP) is being introduced for the first time on a cross sectoral basis under the EU Ecodesign for Sustainable Products Regulation (ESPR). To ensure EU wide implementation and to cover information relevant for compliance purposes, it is reasonable to introduce the DPP horizontally across the NLF. The following considerations are essential in this regard:

Regulatory Coherence

It is crucial that there is a single (technical) DPP system that can be used across all product groups and EU regulations. This system must be interoperable, technologically neutral, free from lock in effects and internationally compatible. Under the ESPR, such a system meeting these criteria is currently being developed and must form the basis for all DPPs. Only this approach allows sector specific requirements and existing systems to be integrated effectively.

However, it is already clear that the DPP will need to integrate into a highly heterogeneous IT landscape. Even minor inconsistencies in interfaces, data formats or update cycles may cause significant disruptions. To mitigate these risks while delivering early benefits, a staged and pragmatic introduction of the DPP system, in close cooperation with industry, is advisable. The goal must be to minimise administrative burdens, especially for SMEs. In an initial phase, only the core functionalities that deliver the greatest societal and economic value should be implemented via a "Minimum Viable DPP". The system can be further developed step-by-step in later phases, when the technical standards are mature, the administrative processes are established, and the market actors are prepared: adding more structured role models, extended data content and stronger validation functions. Clear responsibilities among market actors will be essential to ensure accuracy of DPP information.

Moreover, integration with the planned EU Business Wallet should be envisaged.

Data Provision and Access Rights

A central conflict of objectives in the DPP system concerns data sensitivity. On the one hand, the DPP is meant to enhance transparency and make as much information publicly accessible as possible. On the other hand, depending on the sector, the DPP may contain confidential or commercially sensitive information, such as supply-chain data or product characteristics.

Industry therefore takes a clear position:

▪ The publicly accessible part of the DPP must not contain confidential or competition sensitive information.

▪ Sensitive data that are relevant only for certain authorities (e.g. market surveillance) should be provided only upon justified request and not be mandatory to provide in the DPP. This approach ensures the protection of IP and business secrets and significantly reduces the burden on manufacturers, especially SMEs and industries with a large number of products.

Compliance Data

The DPP should integrate existing compliance related information taken from the traditional Declaration of Conformity. There must be no duplication of information obligations.

Sensitive and IP-related information must not form mandatory components of a horizontal DPP, so as to avoid compromising business or operational secrets This applies to large parts of the technical

documentation required under EU legislation such as construction plans, test protocols or circuit diagrams which must always be provided strictly on a need to know basis.

Furthermore, the system should allow the inclusion of additional voluntary information clearly separated from mandatory compliance data to support transparency for consumers, end users or actors along the supply chain.

Data Storage and Back-Up

Long-term data retention within the DPP framework remains unresolved, as regulatory provisions on archiving, data backup and recoverability are either lacking or vague. This creates considerable uncertainty, especially given the complex and multi-layered data structures involved in DPPs and referenced documents. Questions arise regarding responsibility, retention periods and cost feasibility. System availability and required response capacities likewise remain unclear potentially involving significant expenses.

The EU must establish a clear, horizontal framework for data retention and back-up within the DPP system including principles on responsibility, retention periods and system availability. Sector-specific requirements should then be clarified through delegated acts, preventing excessive demands while ensuring that data are retained where it is genuinely needed

Overcoming Written-Form Requirements

All required information should be allowed in digital form only. If the DPP becomes mandatory, then all user information, including safety information and user instructions, should be permitted to be provided exclusively via the DPP, without any obligation to supply paper-based documentation. Responsibility for meeting the instruction requirement including form must remain with the manufacturer.

The introduction of the DPP must not result in replacing the CE marking on products.

6. Strengthening Market Surveillance

Market surveillance is a central pillar of the NLF. Its objective is to ensure the consistent enforcement of EU harmonisation legislation, thereby protecting public interests such as health, safety, environmental and consumer protection, and ensuring that only compliant products reach the Single Market. These objectives are currently not being fully achieved, resulting in significant competitive disadvantages for manufacturers and other economic operators who comply with the rules.

The principal weakness of market surveillance lies in the insufficient speed and consistency of responses to non-compliant or dangerous products. To address this shortcoming, we support improved financial resources for market surveillance authorities provided by the Member States, as well as closer cooperation between national authorities. Establishing a centrally coordinated EU-level market surveillance authority could make a decisive difference provided it is efficiently organised, builds on existing expertise and avoids creating additional bureaucracy. The European Product Compliance Network (EUPCN) offers a suitable foundation for such coordination. Additional national decision-making structures must be avoided, as divergent enforcement practices undermine the Single Market and create uncertainty for both economic operators and authorities. A dilution of harmonisation would weaken the enforcement of Union law and intensify distortions of competition.

Improving coordination with customs authorities is also essential. While customs carry out operational checks, the technical expertise lies with market surveillance authorities. These structures must be

more closely interlinked to prevent, for example, the re-importation of rejected products via other Member States.

Additional potential remains in the Union Testing Facilities, introduced in 2019. Their use must be systematically enabled and promoted. These facilities make it possible to perform uniform cross-border testing, thereby helping to balance and supplement national capacities.

The issue of online trade also requires urgent attention. In recent years, unsafe products from third countries have increasingly entered the EU through online channels. Clear transparency obligations and reliable legal responsibilities are needed here. Effective market surveillance requires the ability to take action also against economic operators outside the EU, regardless of where they are established. Additionally, online platforms must be obliged to act when they become aware of non-compliant products sold via their services.

As a direct consequence, we call for the consolidation of the currently identical obligations of importers, authorised representatives and fulfilment service providers into a single role that of a verified EU representative, including a clearly defined mandate. This approach would create clear accountability, strengthen enforceability and effectively prevent circumvention of EU rules.

For repeated violations of product safety legislation, market surveillance authorities should, as a measure of last resort, be empowered to withdraw the possibility to use Module A and temporarily require the use of Module H instead. This measure is necessary to address systematic non-compliance and strengthen prevention.

Furthermore, market surveillance authorities should also be systematically involved in legislative procedures. A mandatory enforceability assessment prior to adopting new or revised legal acts is needed to ensure enforceability and practical implementation from the beginning

7. Exemptions for Spare Parts

Spare parts falling within the scope of an NLF legislative act must currently comply with the same state of the art requirements as newly manufactured products. In practice, this causes significant problems. Spare parts are often intended for products that were originally placed on the market under earlier standards and legal requirements. Aligning them with today’s state of the art is technically impossible. As a result, maintaining technical systems both in the private sector and in critical public infrastructure becomes increasingly difficult. In some cases, systems risk being decommissioned because identical spare parts are no longer available.

Repairs of consumer devices are also hindered, their spare-parts availability is restricted, and sustainability objectives are undermined. Yet spare parts are a central component of a functioning circular economy and a precondition for implementing the Right to Repair. They extend product lifecycles and reduce waste.

Example: Repair of a tumble dryer under the Right to Repair: A heat pump tumble dryer is placed on the market after the Right to Repair rules enter into force. Years later, new technical requirements (e.g., a revised component standard) require a different compressor design. But the new compressor no longer fits into the old appliance, making repair impossible. Instead, manufacturers should be permitted to continue offering the original, fitting component as a spare part even if it no longer complies with subsequently updated regulatory or standardisation requirements to enable repair.

We therefore recommend introducing a spare-parts exemption under the NLF, based on the repair-as-produced principle: Components intended exclusively as spare parts should only need to

comply with the NLF requirements that applied at the time the original product to be repaired was first placed on the market. This approach has already been applied under the Cyber Resilience Act (CRA). We therefore propose extending the wording of Regulation (EU) 2024/2847, Art. 2(6), analogously to the entire NLF. The legal text could read as follows:

“This Regulation shall not apply to spare parts made available on the market to replace identical components in products to be repaired and manufactured according to the same specifications as the components they are intended to replace, unless they pose significant risks to health, safety or the environment.”

8. Advancing Circular Economy

The need for coherence and legal clarity is equally crucial in the context of remanufacturing and refurbishment, both of which are essential for advancing the circular economy. These processes can only be viable if supported by a coherent regulatory framework.

We welcome the fact that the Ecodesign for Sustainable Products Regulation (ESPR) for the first time defines and distinguishes these two concepts. Remanufacturing refers to an industrial process in which a new product is created from old and new parts and components, requiring full compliance with all applicable product legislation, including a new CE marking. Refurbishment, by contrast, restores a used product to a functional condition without necessarily meeting all of its original specifications. For this reason, we call for clear labelling (e.g. “refurbished by”) to avoid confusion regarding responsibility and liability.

Despite this clarification, industry continues to face uncertainties caused by overlapping and at times contradictory requirements in various regulatory frameworks such as RoHS, REACH, CRA, and the Machinery Regulation. For example, new substance restrictions introduced after a product was first placed on the market may conflict with remanufacturing efforts or even with recycling processes

To address these issues, future delegated acts under the ESPR should not narrowly define when a change is considered a substantial modification within the meaning of the Machinery Regulation (see Article 3(16) of Regulation (EU) 2023/1230), as doing so could constrain innovation and limit future technological repurposing. Instead, the Machinery Regulation’s provisions should remain decisive. Delegated acts for specific products or product groups should instead clarify which existing requirements (e.g., product safety, product design, chemicals legislation, circularity requirements) apply, and how any potential conflicts between overlapping obligations are to be resolved.

For instance, if an assessment of a machine refurbishment project concludes that a substantial modification within the meaning of the Machinery Regulation has occurred, it would be disproportionate and contrary to the objectives of a circular and resource-efficient economy to require the entire refurbished machine to comply fully with the latest RoHS, REACH or CRA standards, particularly if the original machine was placed on the market before these rules entered into force. A more proportionate approach would be to assess which legal acts are genuinely affected by the modification and apply only those. The refurbisher should issue a declaration of conformity for those acts and append the existing compliance documentation for all others. For components not affected by the modification, the refurbisher should conduct only a risk assessment

Furthermore, original manufacturers must not be obliged to disclose technical documentation, in order to protect intellectual property. Remanufacturers must assume full manufacturer responsibility, including labelling obligations. This ensures product safety for consumers while safeguarding the investments and reputation of the original manufacturers.

About the BDI

The BDI represents the interests of German industry to political decision-makers. In doing so, it supports companies in global competition. It has an extensive network in Germany and Europe, in all important markets and in international organisations. The BDI provides political support for international market development. It also offers information and economic policy advice on all industry-related topics. The BDI is the umbrella organisation for German industry and industry-related service providers. It represents 38 industry associations and more than 100,000 companies with around eight million employees. Membership is voluntary. Fifteen regional offices represent the interests of industry at the regional level.

Imprint

Federation of German Industries (BDI)

Breite Straße 29, 10178 Berlin www.bdi.eu

T: +49 30 2028-0

German Lobbying Register number R000534

EU Transparency Register: 1771817758-48

Editorial Office

Helena Weizel

Environmental, Technology and Sustainability, Senior Manager

T: +49 30 2028-1589 h weizel@bdi.eu

BDI document number: D2228