C LA RK T HE

A

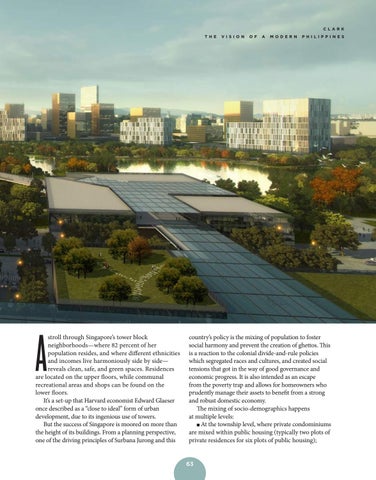

stroll through Singapore’s tower block neighborhoods—where 82 percent of her population resides, and where different ethnicities and incomes live harmoniously side by side— reveals clean, safe, and green spaces. Residences are located on the upper floors, while communal recreational areas and shops can be found on the lower floors. It’s a set-up that Harvard economist Edward Glaeser once described as a “close to ideal” form of urban development, due to its ingenious use of towers. But the success of Singapore is moored on more than the height of its buildings. From a planning perspective, one of the driving principles of Surbana Jurong and this

V I S I O N

O F

A

M O DE RN

P H I LI P P I N E S

country’s policy is the mixing of population to foster social harmony and prevent the creation of ghettos. This is a reaction to the colonial divide-and-rule policies which segregated races and cultures, and created social tensions that got in the way of good governance and economic progress. It is also intended as an escape from the poverty trap and allows for homeowners who prudently manage their assets to benefit from a strong and robust domestic economy. The mixing of socio-demographics happens at multiple levels: At the township level, where private condominiums are mixed within public housing (typically two plots of private residences for six plots of public housing); 63