The Carroll School of Management at Boston College

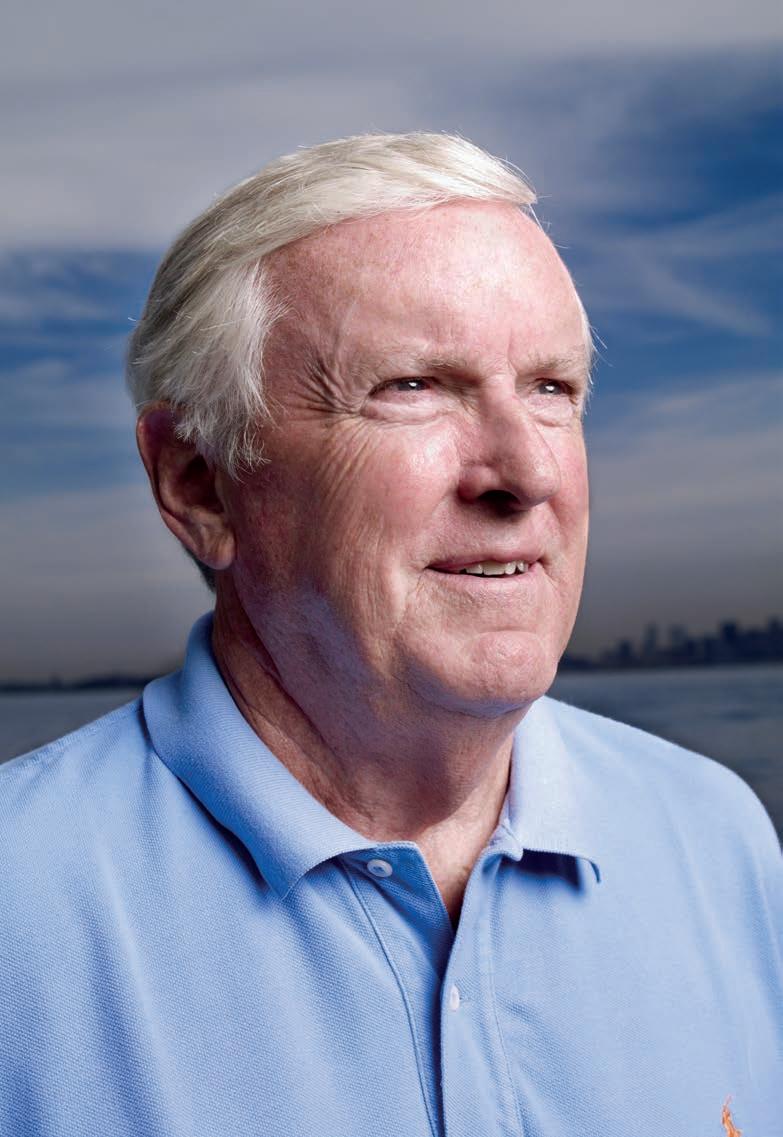

Natalie White ’20 Is Championing Women’s Basketball Through Moolah Kicks Jack Connors ’63, “The Last King of Boston”

Nobel Prize Winner

ISSUE NO.2 / 2024

He’s a Famous Optimist, So Why Is He Worried?

Paul Romer Meet Nine Alumni CEOs Shaking Up Their Industries the Boston College Way

22

Carroll Capital The Publication of the Carroll School of Management at Boston College / Issue No.2 / 2024

Launch

2 From the Editor Paths Up the Mountain BY WILLIAM

BOLE

4 From the Dean The More Things Change BY ANDY

BOYNTON

Ventures

5 Home Run

Joe Martinez ’05 left professional baseball for consulting. It made him understand the game better.

6 Accounts

Ronnie Slamin ’13 brings mixed-income housing to a rich enclave; a bold proposal from the director of the Center for Retirement Research; highlights from speakers on campus; and more.

10 Insights

How anyone can find meaning and hope on the job; the “State of Corporate Citizenship” report.

12 Enterprise

Natalie White ’20 pens a love letter to women’s basketball with her brand Moolah Kicks.

14 Application

AI can write, calculate, and even joke, but can it know when your boss is having a bad day?

35 Disabused

When helping hands are picking the elderly’s pockets.

36 Community

Veterans find support as they make their way to the MBA; alumni entrepreneurs paying it forward with SSC Ventures; the year in competitions.

40 Research

Recent findings by Carroll School faculty members.

16

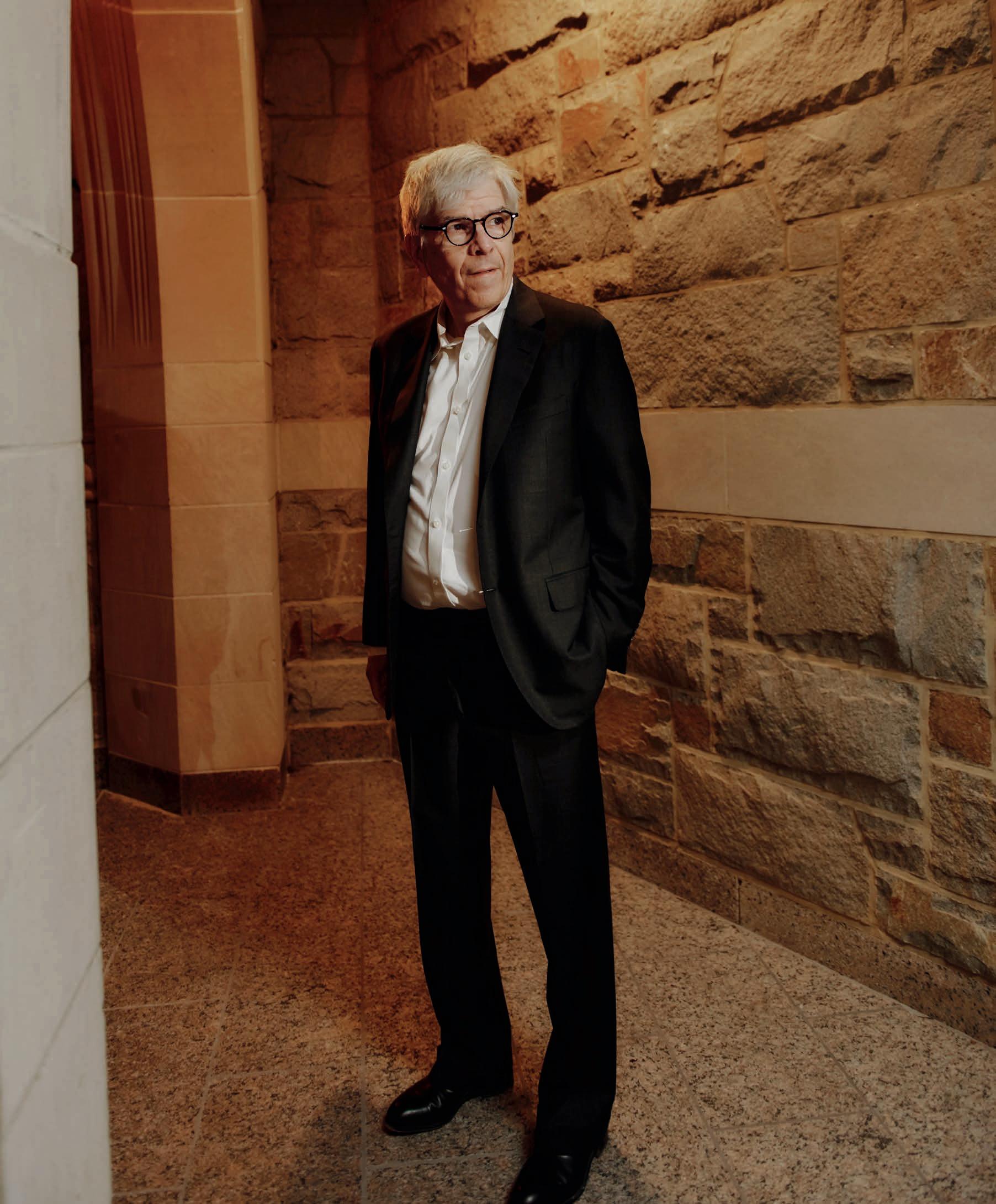

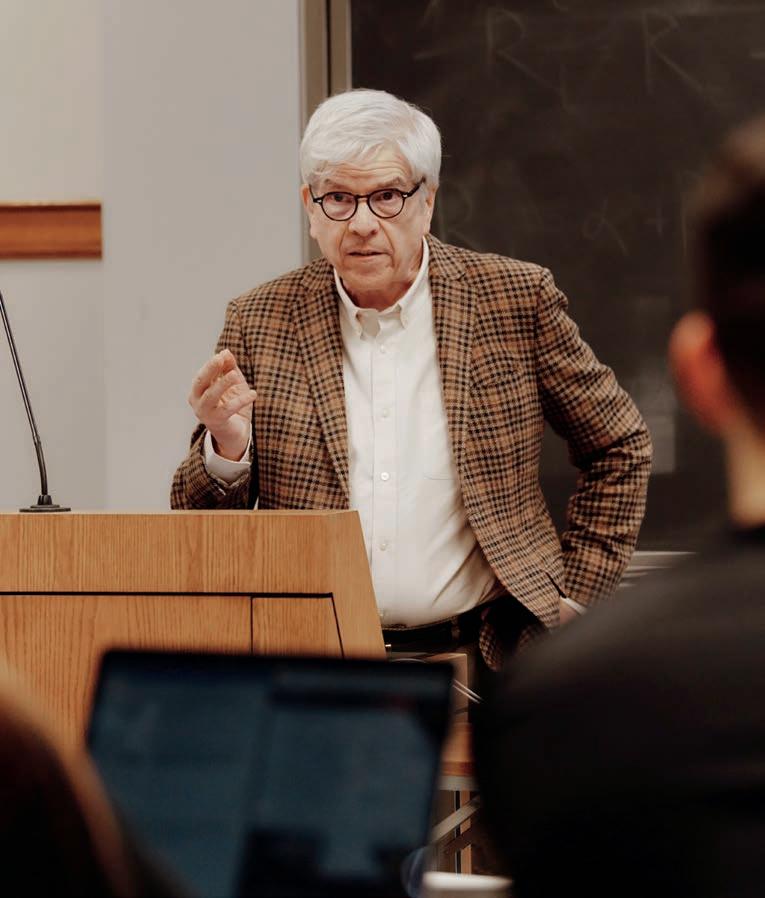

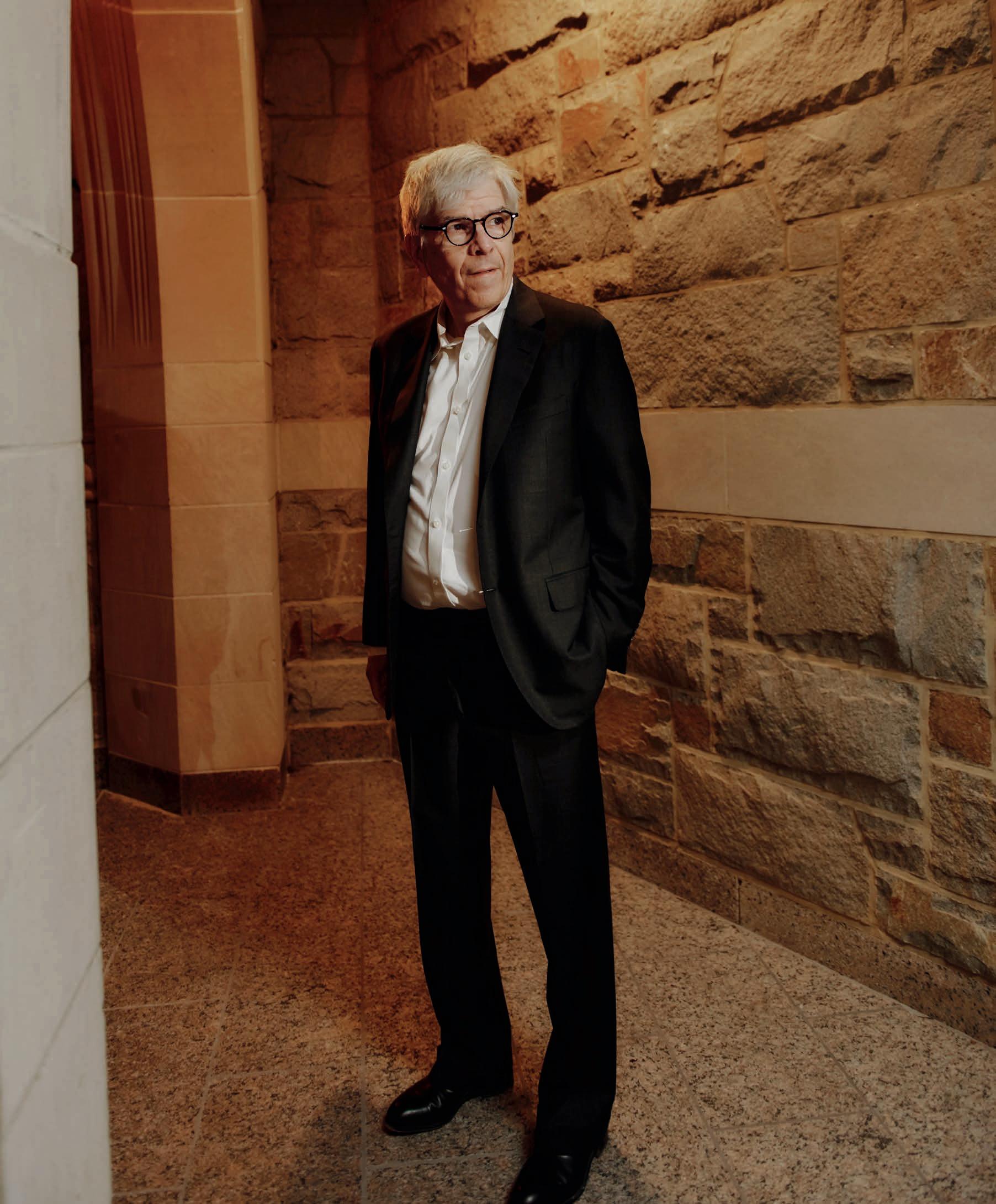

A Nobel Laureate Remakes Himself at Boston College

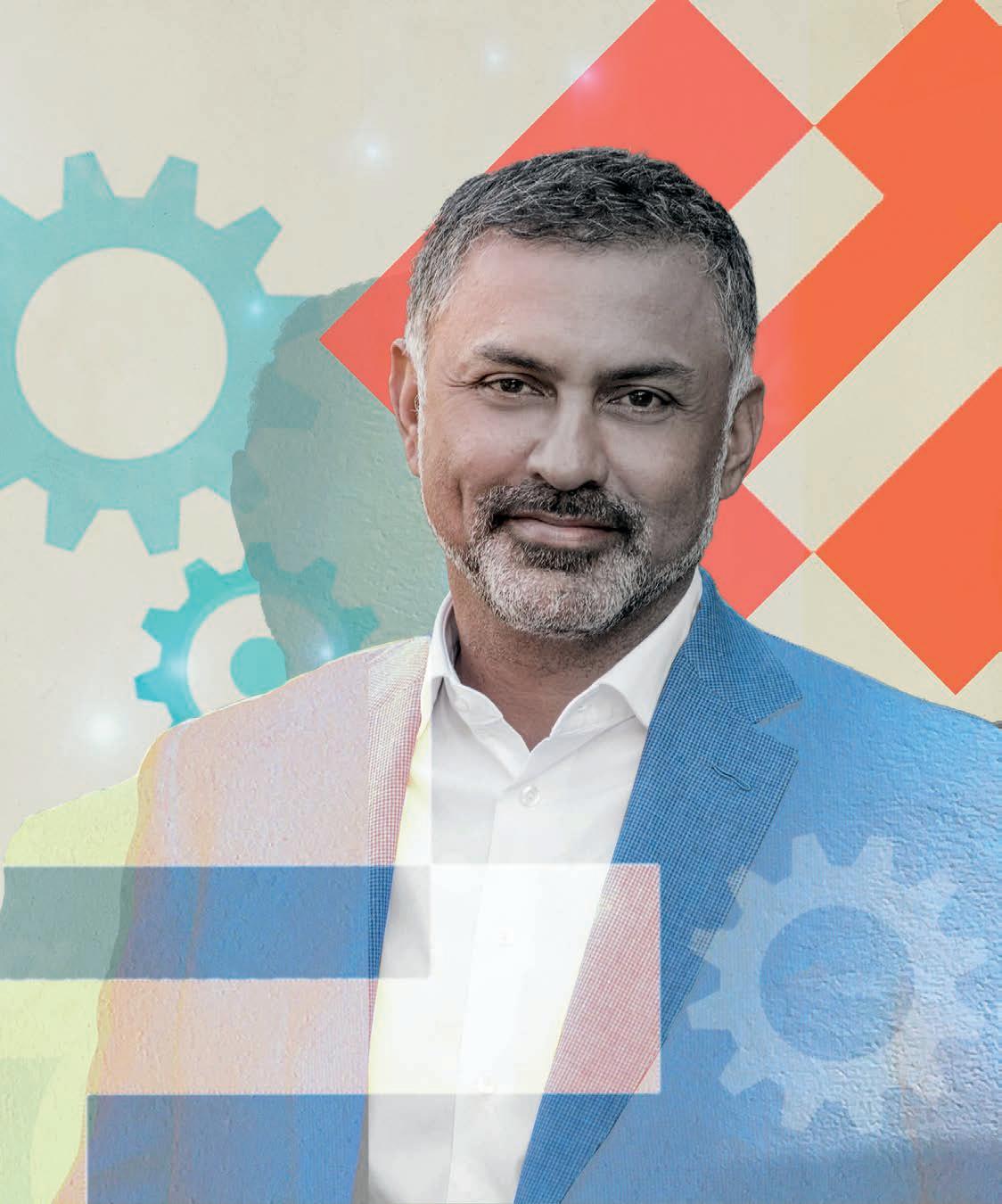

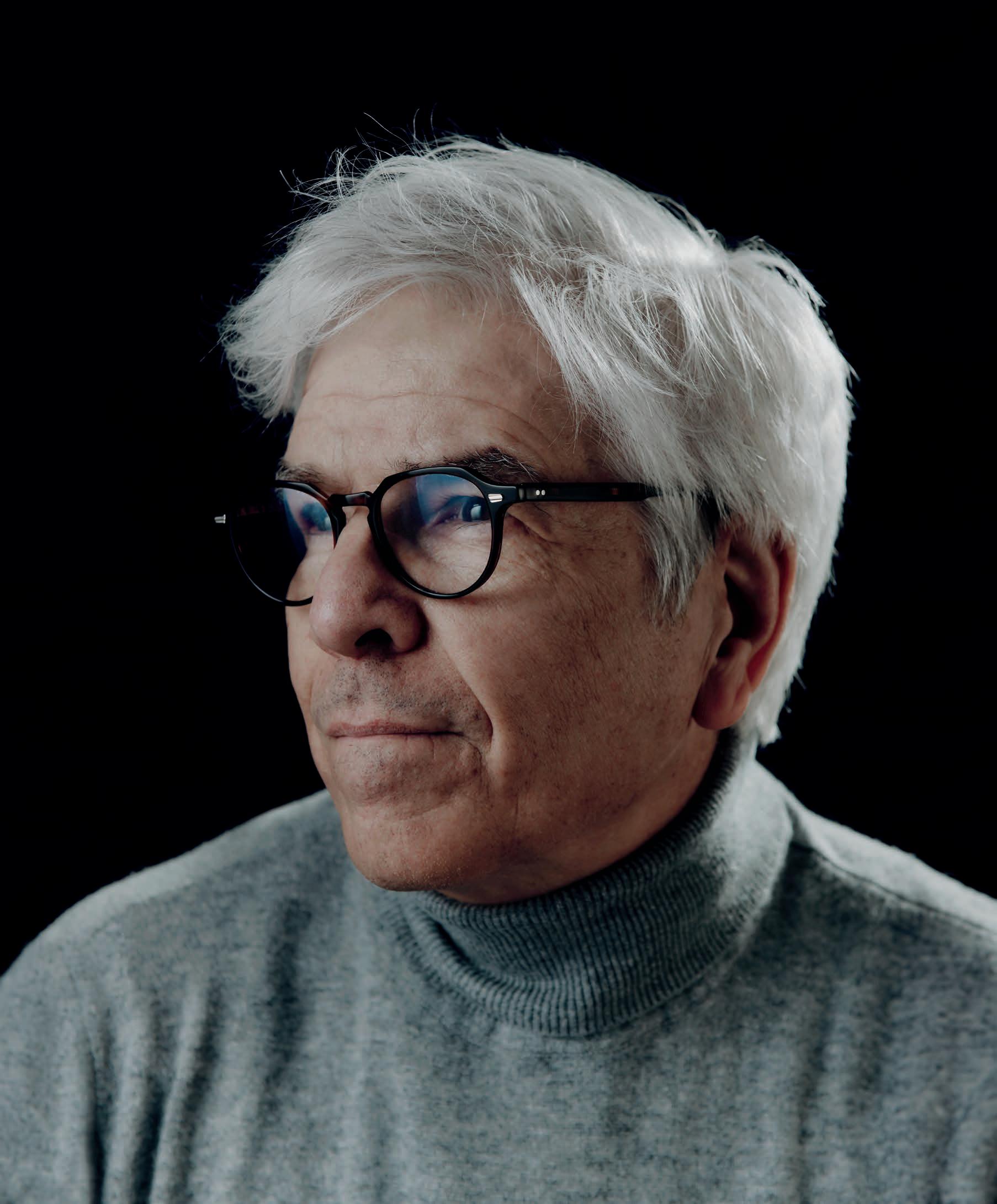

Paul Romer won a Nobel Prize in economics for his upbeat theory of growth, which shined a light on how ideas, rather than things, lead to economic expansion and human progress. Now he’s teaching coding and taking on threats in the digital realm that he fears could forestall new discoveries. Can he change the world twice? BY WILLIAM BOLE

22

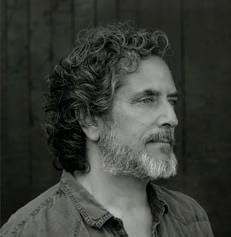

In Any Way, Shape, or Form

Students in the Carroll School of Management spend their years on the Heights charting their own unique paths to adulthood. The University isn’t just standing on the sidelines cheering them on. From academics to extracurricular life, Boston College is shaping the whole experience through formative education. BY

JACLYN JERMYN

26

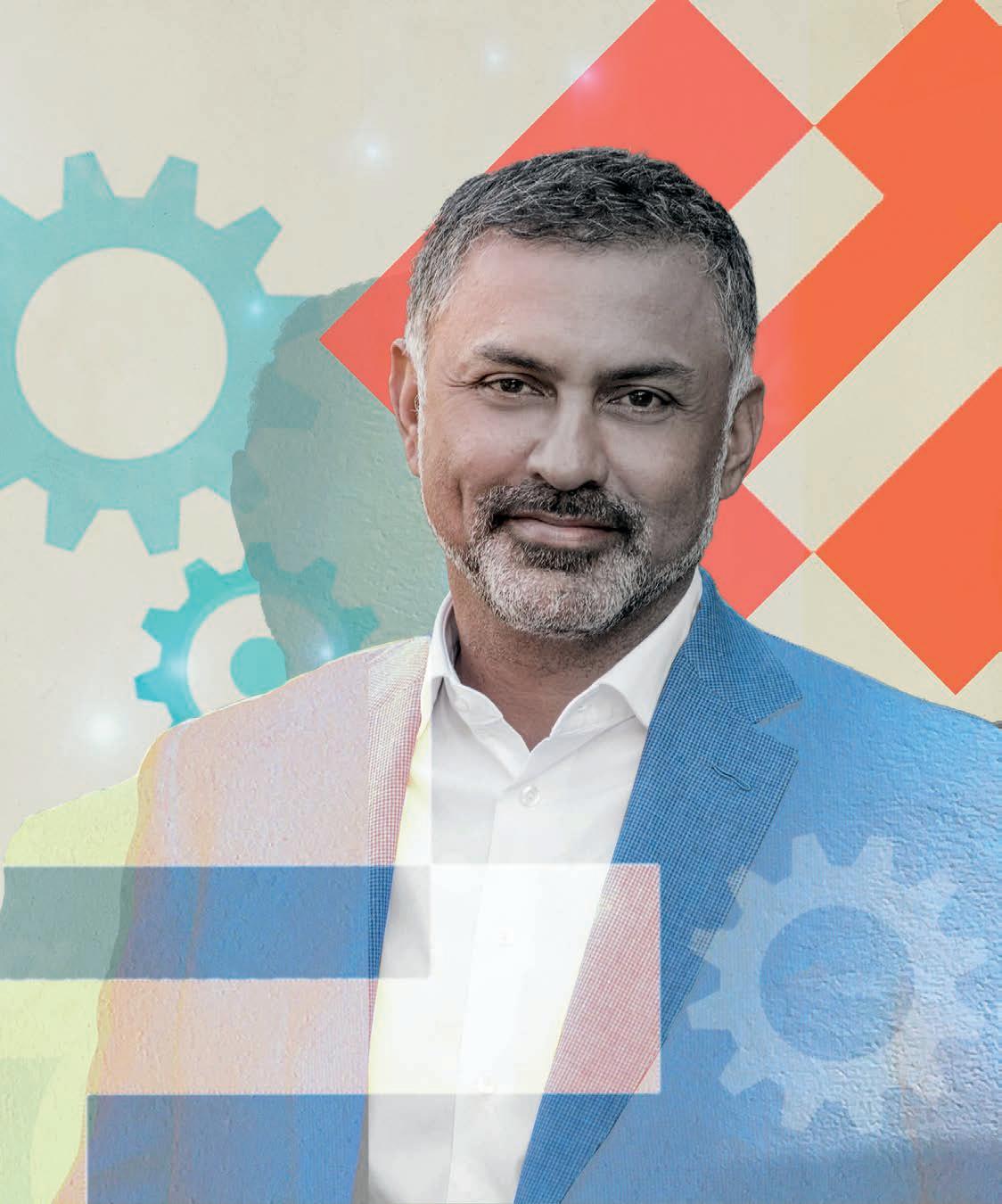

The Changemakers

Running businesses ranging from startups to Fortune 500 companies, these nine Carroll School alumni CEOs are shaking up their industries the Boston College way. BY ABANTI AHMED ’25, WILLIAM BOLE, MASON BRAASCH, AND JACLYN JERMYN

42 Impact

More aggressive recruiting timelines; why every Carroll School student is learning how to use business analytics.

44 Investments

Spring Portico classes provide second-semester seniors with a space to reflect; a new accounting course prepares students for a changing world.

46 Distinctions

Christian Cavaliere ’20 takes a swing at the US Open; the first Carroll School women grads celebrate an anniversary; and other achievements.

48 Bottom Line

Jack Connors ’63, “the last king of Boston.”

2024 CARROLL CAPITAL 1 COVER PHOTOGRAPH BY TONY LUONG

Contents

26

Features

Assets

36 12 Photographs, from left: Joshua Dalsimer, Dana Smith, Kelly Davidson; Opposite: Kelly Davidson

Students can find multiple paths up the mountain by virtue of Boston College’s approach to formative education, which helps them grapple with the big questions as they shape their studies across disciplines and their experiences into a coherent whole.

Paths Up the Mountain

How management students are expanding their horizons, just like their professors.

BY WILLIAM BOLE

There’s an offbeat story of a young man who sets out to learn the meaning of life, and he’s told that there’s a great sage in the high altitudes of India who can tell him what it’s all about. So he travels to the Himalayas—picture a backpacker trekking through mountains and wild forests—and reaches the top. There, he finds the sage meditating in an isolated cave and asks him, “Could you tell me the secret of the meaning of life?” After a few minutes, the guru opens his eyes, looks up from the flat dirt floor, and speaks … “Life is a fountain.” The seeker replies, “You mean, I traveled thousands of miles for you to tell me that life is a fountain?” And the sage tells him, “Okay, so it’s not a fountain.”

Fortunately, young men and women at Boston College don’t need to hop on planes and hike through gorges to seek a higher understanding of themselves and their place in the universe. They can find multiple paths up the mountain by virtue of Boston College’s approach to formative education, which helps students grapple with the big questions as they shape their studies across disciplines and their experiences into a coherent whole.

You could view the process up close by turning to page 22 of this

issue of Carroll Capital. Our story spotlights busy Carroll School of Management students patching together their formative education, toggling between finance in Fulton and philosophy in Gasson, extending outward through organizations like the Joseph E. Corcoran Center for Real Estate and Urban Action, and reflecting on their experiences together with peers at an array of retreats. With any luck, they’re forming themselves—intellectually, socially, and spiritually.

All that might not sound very

hard-nosed for management students. As we report on page 42, they have pressures that past Eagles didn’t have, including for many the need to start jockeying for internships at the start of sophomore year, before they’ve had much of a chance to explore academic interests and career options. They need to be pragmatic, in other words. And yet, those profiled in our article about formative education would heartily agree with G.K. Chesterton’s observation in his classic work Orthodoxy. Chesterton explained that pragmatism is about human needs—“and one of the first of human needs is to be something more than a pragmatist.” Students today are seeking the “something more.”

The faculty play no trifling part in the scheme of student formation. In and out of the classroom, they model the habits of mind that lead students to think broadly, critically, and analytically. One such scholar is Seidner University Professor Paul Romer, profiled on page 16. He sets an example of how to form and reform yourself by seeking ideas and inspiration in all places, a trait that won him a Nobel Prize in economics.

And some Carroll School professors not only impart meaning but also devote their research to the subject. They include several Management and Organization professors whose research (featured on page 10) offers insight into how anyone, whether a hospice nurse or a financial analyst, can find meaning in their work. As future professionals, Boston College students get a head start on cultivating that sense of higher purpose, and they don’t even have to scale the Himalayas to reach those heights.

From the Editor 2 CARROLL CAPITAL 2024

Launch

PAGE 22 PHOTOGRAPH BY MATT KALINOWSKI

Contributors

A proud Coloradan, Davis recently graduated from Boston College with a bachelor’s degree in Communication. In addition to completing minors in English as well as Management and Leadership, Davis also served as a staff writer for The Heights and as president of the Ignatian Society. For this issue, she reported on golfer and business owner Christian Cavaliere ’20 and his journey from the Heights to the life-changing experience of playing in the 2023 US Open (page 46). Davis lives in Boston and is pursuing a career in public relations.

About

Check out our website and follow us on social media for the latest on the Carroll School of Management.

bc.edu/carrollschool

Facebook-square carrollschoolbc

TWITTER bccarrollschool

INSTAGRAM bccarrollschool

linkedin school/carroll-schoolof-management

Tim Gray WRITER

Gray is a freelance writer and editor who specializes in financial topics. He contributed to The New York Times for two decades, and has written books and case studies with professors from Harvard Business School and the Wharton School. In this issue, Gray covered topics including recent faculty research (page 40) and the utilization of AI in the workplace (page 14). A graduate of Georgetown University, he and his spouse, Joseph L. Sweeney Chair Mary Ellen Carter, live in Bedford, Massachusetts, with a spoiled pointer named Greta.

Mission

Originally from Clinton, Connecticut, Luong is a Boston-based photographer who earned an MFA from the Massachusetts College of Art and Design. His work has been exhibited in Boston and New York, and has appeared in publications including The Atlantic, Bloomberg Businessweek, The New York Times, The New Yorker, Esquire, Time, and Wired. He believes that the act of photography can be a conduit to understanding each other better. Luong photographed Nobel Prize winner Paul Romer for this issue’s cover story (page 16).

Smith is an editorial illustrator and photographer whose work has appeared in publications worldwide such as The New York Times, The Wall Street Journal, The Washington Post, The Boston Globe, Fortune, The Los Angeles Times, Stern, and Le Monde. In this issue, Smith depicted the nine Carroll School alumni CEOs featured in “The Changemakers” (page 26) through photo collage, a process he describes as akin to “putting together a jigsaw puzzle first and then finding a way to squeeze narrative tidbits in between.”

The Carroll School of Management at Boston College ranks among the world’s leading business schools. It offers a rigorous, transformative academic experience that integrates the study of management with the liberal arts, while developing critical thinking skills and fostering ethical leadership. Part of a vibrant, Jesuit, Catholic university, the Carroll School draws inspiration and direction from our centuries-old religious and intellectual heritage. We maintain an enduring conviction that successful management education in the 21st century must combine excellence in teaching and research with reflection and action. The Carroll School educates the whole person in an atmosphere that is inclusive, ethical, caring, collaborative, and respectful of all, consistent with Boston College’s institutional mission and motto of “Ever to Excel.”

Engagement

We invite alumni, parents, and friends to engage with Boston College and the Carroll School of Management, in concert with the University’s mission and priorities. Through opportunities such as the Alumni Association’s programming, the Career Center’s Eagle Exchange, or a gift to the Carroll School in support of students and faculty, the BC community can make a meaningful impact on the University and beyond. For more, visit bc.edu/alumni.

John and Linda Powers

Family Dean

ANDY BOYNTON ’78, P ’13

Editor-in-Chief

WILLIAM BOLE

Deputy Editor

JACLYN JERMYN

Assistant Editor MASON BRAASCH

Creative Director

ROBERT F. PARSONS / SEVEN ELM

SEVENELM.COM

Contributing Writers

ABANTI AHMED, MCAS ’25

PATRICK BOLE, MCAS ’24

RILEY DAVIS, MCAS ’24

TIM GRAY

OLIVIA JUSTICE, CSOM ’25

PATRICK L. KENNEDY, MCAS ’99

DANIEL M c GINN, CSOM ’93

ELIZABETH M c GINN

SALLY PARKER

LILIANA STELLA, CSOM ’27

MARGIE ZABLE FISHER, CSOM ’89

Contributing Artists

CHRISTOPHER CHURCHILL

JOSHUA DALSIMER

KELLY DAVIDSON

EDU FUENTES

JAMES GRAHAM

LUISA JUNG

MATT KALINOWSKI

MIKE LEMANSKI

TONY LUONG

ADAM M c CAULEY

KAGAN M c LEOD

LEE PELLEGRINI

DAVID PLUNKERT

DANA SMITH

STEPHEN VOSS

BRYCE WYMER

DAVID YELLEN

Image Specialist

STEPHEN BEDNAREK

Printing

ROYLE PRINTING

© 2024 Trustees of Boston College. All rights reserved. Carroll Capital is published once a year in June. Carroll Capital is printed by Royle Printing in Sun Prairie, WI. Please send questions, comments, or requests for more information to:

Phone: 617-552-1373

Mail: Carroll Capital, Carney Hall 443, 281 Beacon Street, Chestnut Hill, MA 02467

Email: carrollcapital@bc.edu

Opinions expressed in Carroll Capital do not necessarily reflect the views of the Carroll School of Management or Boston College.

2024 CARROLL CAPITAL 3

Tony Luong PHOTOGRAPHER

Riley Davis ’24 WRITER

Dana Smith ILLUSTRATOR

Launch

The More Things Change

Dynamism and stability at Boston College.

BY POWERS FAMILY DEAN ANDY BOYNTON

At the end of the spring semester, I found myself reflecting on the old and the new at Boston College, and how those two aspects of life hang together in a creative and dynamic balance on the Heights. Clearly, so much has changed. Just a sprinkling of examples: Boston College now has the HumanCentered Engineering program, aligned closely with the liberal arts and the Schiller Institute for Integrated Science and Society; we’ve built a bridge between management and the arts and sciences, with half of all Carroll School students majoring or minoring at the Morrissey College of Arts and Sciences, and around 1 ,500 MCAS students enrolled in our management minors;

also, as you may know well, the selectivity rates for Boston College undergraduate admissions are off the charts.

Still, almost every day brings reminders of how much has remained the same since I walked the halls of Fulton as an undergraduate during the 1970s. Students are still stressed out about Financial Accounting, as I was, too. They’re still taking theology in Gasson and sociology in McGuinn, still tossing footballs on Stokes Lawn (known in my day as the Dust Bowl), still seeking out the counsel of priests and professors during the occasional difficult times (the mentors have different names but they’re every bit as compassionate). I did all of that, and I still walk up and down the million-dollar staircase, alongside students who tend to climb up slightly faster than I do these days.

The two elements—dynamism and stability—have been essential to carrying out Boston College’s mission and staking out new paths at the Carroll School.

For example, we invested heavily in Business Analytics, revamping our curricular offerings in response to an urgent need for data skills in today’s organizations; our Business Analytics Department is now ranked 10th in its discipline nationally, according to U.S. News and World Report. But at the same time, leaning into tradition, we intensified the study of key ethical theories with application to business in our required freshman Portico class, and we went further to create a new slate of Portico courses for seniors who want to end their days at the Carroll School the way they began, with Portico. You can read about how both Business Analytics and Portico have

evolved on pages 43 and 45 of this Carroll Capital edition.

This interplay of old and new brings into focus not only our style of management education at Boston College but also the challenges in today’s rapidly changing business environments. The best organizations—in any industry—combine a quality of enduring greatness with a drive to constantly renew themselves. They draw upon a legacy of values and success, as well as a spirit of innovation. An outstanding example is Amazon, which has built upon a foundation (namely, the retail website) with an ongoing stream of experimentation, including its cloud and web services.

You could get a taste of how all this is done, the Boston College way, by perusing our profiles of Carroll School alumni CEOs (page 26), who are tackling tough issues in their industries, ranging from cybersecurity and turbulence in the banking industry to diversity and sustainability. They’re succeeding partly by applying the lessons they learned and values they encountered on the Heights. And then there’s the illustrious Jack Connors ’63, H ’07, P ’93, ’94, who makes things happen for his alma mater and his city by personifying the dynamism of old and new. He’ll regale you on the last page of this publication with his stories and wisdom.

Boston College and the Carroll School have made great strides in recent times, but the gains would have been few and far between without the continuity—most essentially, the Jesuit Catholic ethos and liberal arts tradition that animate the curriculum, student life, and other areas of the University. Change and stability will carry us further still. Ever to Excel!

From the Dean 4 CARROLL CAPITAL 2024

PHOTOGRAPH BY MATT KALINOWSKI

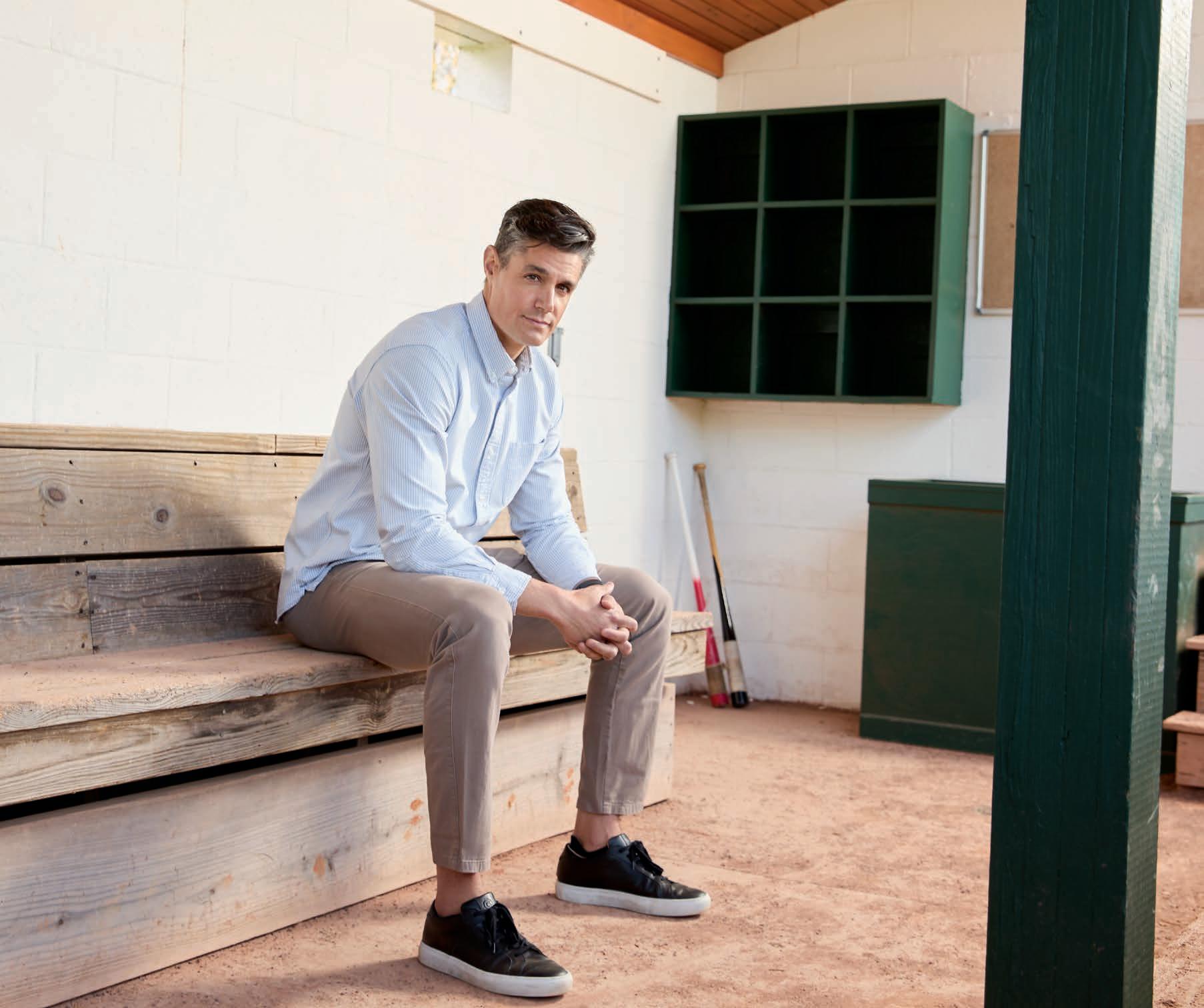

Home Run

Ventures

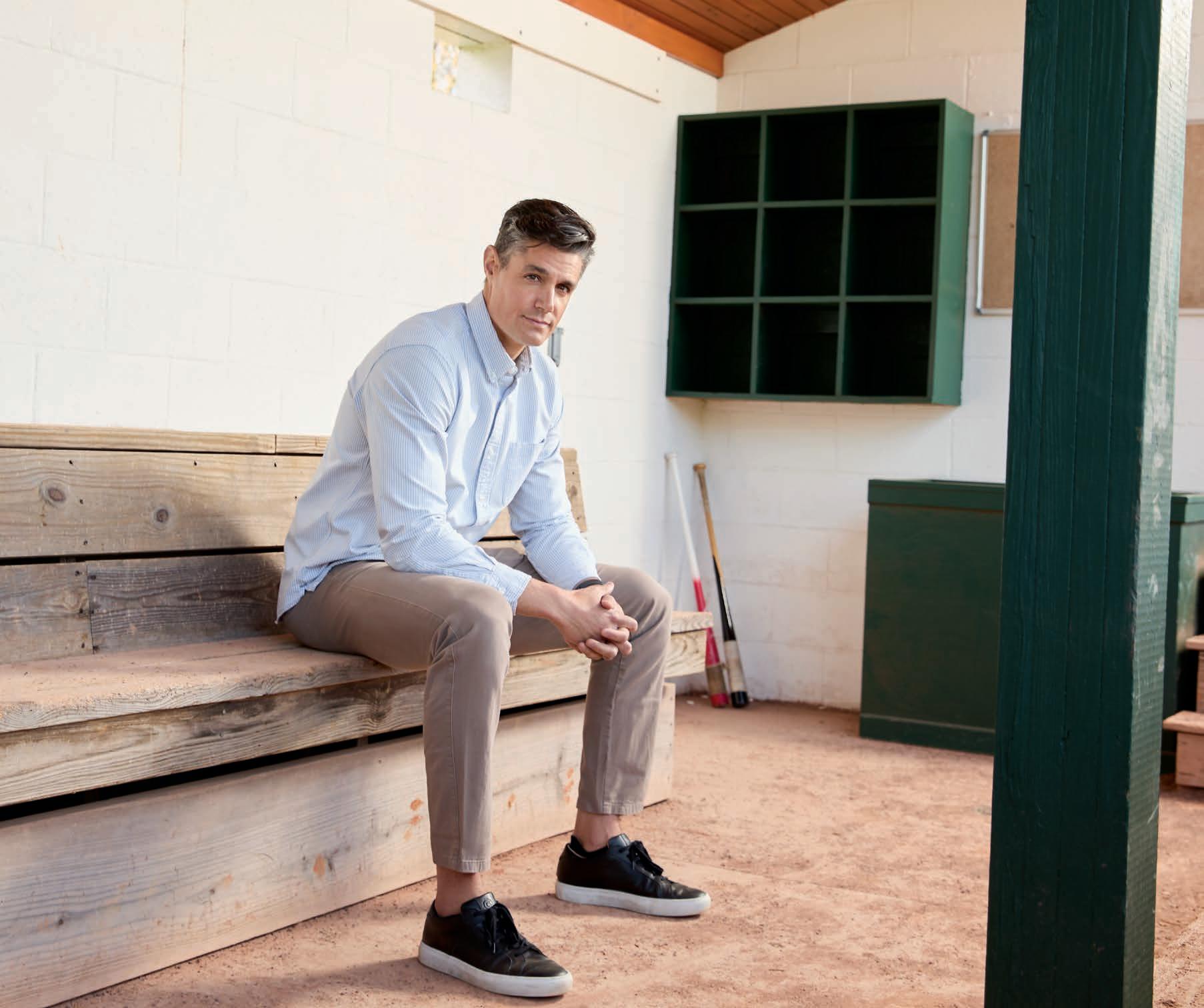

JOE MARTINEZ ’05 LEFT PROFESSIONAL BASEBALL FOR CONSULTING. IT MADE HIM UNDERSTAND THE GAME BETTER.

With something so steeped in American culture as baseball, it’s easy to forget that the sport is also a business. “Just like with any business, you always have your consumer in mind,” says Joe Martinez ’05. “We need fans to pay to watch, come to games, and buy merchandise.”

Martinez, the vice president of on-field strategy for Major League Baseball, spent a decade playing baseball professionally—even earning a World Series ring with the San Francisco Giants—before trading his jersey for a suit and entering the consulting industry, first at Morgan Stanley and then PwC. Martinez says it was a desire to up his professional game that made him take the leap, a risky move that paid off when the MLB came calling again in 2020. These days, part of his role revolves around implementing new league rules—like the introduction of a pitch clock—to improve gameplay and fan experience. While the MLB wants to ensure fans see a great game, “you don't want to make it too difficult for our players to do what makes them great,” he says. “I have a unique perspective,” he says of his experience on and off the field. “I consider myself very fortunate to be able to keep structuring my life around the game I love.”

JACLYN JERMYN

2024 CARROLL CAPITAL 5

Accounts P.6 Insights P.10 Enterprise P.12 Application P.14

PHOTOGRAPH

BY JOSHUA DALSIMER

Ventures Accounts

On the Heights

James N. Mattis

The former US Defense Secretary headlined the annual Finance Conference in May, highlighting threats to global stability. “The best way to deal with this is allies, allies, allies,” especially in Europe, he said. Other speakers included former Boston Fed president Eric Rosengren; NFL owners Jonathan Kraft, P ’24, and John K. Mara ’76, P ’03, ’05, ’08, ’12; and AI expert Anima Anandkumar.

Stuart Weitzman

American shoe designer and founder of his eponymous luxury brand put his best foot forward at a February talk cohosted by the Edmund H. Shea Jr. Center for Entrepreneurship and Winston Center for Leadership and Ethics. “Risk is your absolute best friend,” said Weitzman. His risks have paid off: Luminaries like Beyoncé and Taylor Swift are regular customers, along with millions of others.

Nadia Murad

The Nobel Peace Prize winner brought her story of kidnapping at the hands of ISIS to the spring Winston Center for Leadership and Ethics Clough Colloquium. After surviving her imprisonment in Iraq, Murad started Nadia’s Initiative, which advocates for survivors of sexual violence.

“I knew silence was not an option,” she said of becoming an activist even after experiencing such brutality.

James M. Lang

The educator brought his gospel of “small teaching”— simple changes that bolster student learning—to the Carroll School’s Wilson Faculty Teaching Seminar in March. One example: pausing briefly during class; a study found that students doing so recalled more exam material than those who didn’t pause. “I sometimes feel like an evangelist about these things,” Lang said.

Lighting a Fire

With their startup MLV Ignite, two students are hoping to spark a passion for entrepreneurship in high schoolers.

BY OLIVIA JUSTICE ’25

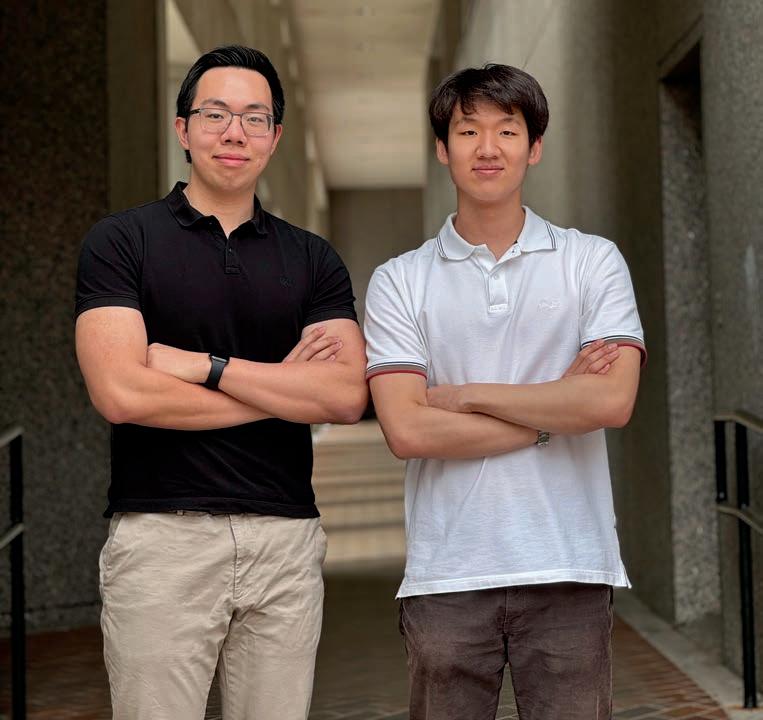

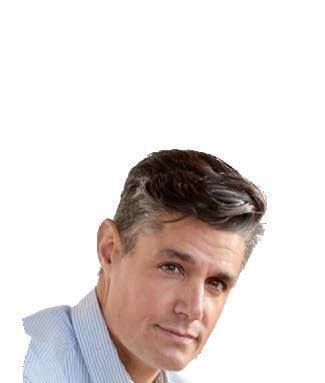

Growing up in Hong Kong, Tim Liu ’26 spent his primary school years in a local education system that emphasized memorization and high-stakes exams. When he later had the opportunity to attend an international school, Liu was exposed to a learning environment where, in addition to getting good grades, creativity and open-mindedness were also rewarded. “It was a radical shift in teaching philosophy,” he says of the transition. “There was more emphasis on seeing things from different perspectives.”

When Liu arrived on the Heights, he became fast friends with Dylan Kim, MCAS ’26. The pair joined the Start@Shea Freshman Innovation Program, where they regularly attended workshops and information sessions hosted by the Edmund H. Shea Jr. Center for Entrepreneurship. Inspired, Liu knew he wanted to provide high school students with similar opportunities for holistic and hands-on education.

Together with Kim, Liu launched MLV (Mâm Lá Viêt—which translates to “Vietnamese Leaf Sprouts”)

Ignite, a two-week program in Kim’s home country of Vietnam that guides high schoolers through the steps of developing their own startups. Liu utilizes his finance and entrepreneurship concentrations to act as CFO, while Kim, a computer science major, serves as CEO. MLV Ignite was piloted in Winter 2024 and more than 100 students applied for 10 open spots.

“The idea is not for these students to be experts in entrepreneurship,” says Liu. To him, it’s more about giving them the confidence and resources to explore their business interests broadly. The first MLV Ignite summer programs will take place in two Vietnamese cities, Ho Chi Minh and Hanoi, and consist of English-language lessons on topics like pitching, revenue generation, and goal-setting.

“We’re trying to give students the skills they need to stand out on their college applications, but also prepare them [for adulthood] through entrepreneurship,” Liu says. “The most important thing is to find your passion. That’s what we hope to do, give them that passion.”

6 CARROLL CAPITAL 2024

EVENTS

Tim Liu ’26 and Dylan Kim, MCAS ’26

Kavner photograph: RC Rivera

TASTE MAKERS

LAUNCHING A

STARTUP IN THE FOOD INDUSTRY IS A NOTORIOUSLY TRICKY ENDEAVOR. MEET THREE ALUMNI WHO TOOK THE CHALLENGES IN STRIDE—WITH SOME DELICIOUS RESULTS.

BY JACLYN JERMYN

Can-Do Attitude

Kat Kavner ’14 was taking note of booming sales of canned beans during the pandemic as people stocked their pantries for extended stays at home. As an on-again, off-again vegetarian, Kavner already knew how versatile beans could be when it came to cooking, but she felt that canned food could use a bit of a makeover for a new generation of grocery shoppers.

Her company, Heyday Canning Co., which launched in Winter 2022, sells a line of canned beans in chef-inspired sauces. With bold, eye-catching branding and inventive flavors like Kimchi Sesame Navy Beans and Harissa Lemon Chickpeas, Heyday’s products are made for millennial and Generation Z consumers looking to get delicious meals on the table quickly. “If you look at Campbell’s ads from the 1950s, they were selling the same thing that we’re selling, which is easy home cooking,” she says, but Heyday’s products are tailored to its customers’ modern palates and busy schedules.

The company had difficulties starting during the pandemic, due to manufacturing challenges. Now, Heyday’s beans—and a new line of canned

soups—can be found in grocery stores nationwide. “There are all of these different categories with no innovation,” she says. “We want to reinvent canned food for a new generation.”

Sweet Success

After graduating and moving to New York to start a marketing career, Joe DeCarle ’09 stumbled across the story of a family-run coconut farm in Sri Lanka that fundamentally changed his goals. “I realized I wanted to connect this network of small farmers to consumers in America,” he explains. Inspired, DeCarle started Sweet Origins, a wholesale import company that works with farmers globally to source tropical products like coconut water and sell them to smoothie bars, juice shops, and more. It’s no small feat to navigate a small business with a global footprint. “When you’re moving goods across the world, so much is out of your control,” he says. “We had the pandemic with ballooning costs, then the issues in the Red Sea … political, economic, and otherwise, so many things can impact what’s happening on these trade routes.”

DeCarle has to maintain good relationships with shipping companies and farmers while managing customers’ expectations, he explains—and do all that outside his day job as a marketing director for American Express. He recently introduced new products to Sweet Origins, including açaí berries and dragon-fruit puree. “I’m trying to position the company as the expert at importing tropical ingredients,” he says.

Cold Comfort

Matt Fonte ’94 thinks it was about time someone shook up the ice cream industry. “It’s been the same since our grandparents were eating ice cream as children,” he says. In 2018 Fonte created ColdSnap, a rapid freezing appliance churning out ice cream and other frozen treats from single-serving pods in about two minutes— like a Keurig coffee maker, but much cooler.

When his daughters Sierra and Fiona (then nine and seven years old) pitched him an athome ice cream maker, Fonte explained that it already existed—the machines just required multiple, intensive steps to use. A serial entrepreneur, Fonte’s wheels were already turning. What if there was a machine that could produce fresh ice cream in just minutes?

ColdSnap hit the commercial market in Spring 2024. At the company’s factory in Billerica, Massachusetts, machinery has been sourced from around the world to produce and package the product mixes—like salted caramel ice cream, mango smoothies, and frozen margaritas—into shelf-stable pods. Doing this work in-house means that ColdSnap can keep proprietary technology protected. “We’re building a picket fence around our intellectual property,” Fonte says—ColdSnap currently holds 105 issued patents. This strategy also ensures that supply chain disruptions, like those that arose during the pandemic, won’t derail the business.

With ColdSnap currently available for sale to businesses, Fonte is already thinking about how to get his product in homes so other families can have ice cream on demand. It’s a goal that unites his team, he says. “We want to do something that has never been done before.”

2024 CARROLL CAPITAL 7

Kat Kavner ’14

MIXING IT UP

RONNIE

SLAMIN ’13 IS BRINGING

MIXED-INCOME HOUSING TO ONE OF THE RICHEST NEIGHBORHOODS IN WASHINGTON, DC.

BY DANIEL M c GINN ’93

As a freshman at Boston College, Ronette “Ronnie” Slamin ’13 signed up for a summer service trip to Jamaica because she wanted to make more friends. There, she witnessed the connections between poverty, education, and housing. “I was really taken aback by how poor the roads and housing were,” she says, describing leaky tin roofs and roads marred by cavernous potholes. And because of where they lived, residents had no real options for quality education. Their housing impacted their trajectory in life.

It’s approximately 2,300 miles from those low-income neighborhoods of Jamaica to one of the wealthiest areas of Washington, DC. But for Slamin, that service trip provided the spark for a career that’s led to a mammoth undertaking: a $19 million deal to buy and rehab a mixed-income apartment building a few blocks from the Bezos and Obama residences.

Slamin, who grew up in a low-income area of Delaware and went to boarding school in Maryland, arrived at Boston College with aspirations to become a sportscaster. But after returning from Jamaica, she registered for the Real Estate and Urban Action course taught by Joseph Corcoran ’59, H ’09, P ’85, ’86, ’87, ’98, and Neil McCullagh. Corcoran, who died in 2020, would later become the namesake of the Carroll School’s Joseph E. Corcoran Center for Real Estate and Urban Action, with McCullagh as executive director. During college (as an intern) and after graduation, Slamin also worked for

PHOTOGRAPH BY STEPHEN VOSS 8 CARROLL CAPITAL 2024

Ventures Accounts

Ronnie Slamin ’13 stands in front of an apartment building that her firm, Embolden Real Estate, is rehabbing and turning into affordable housing.

The American City Coalition (TACC), a Corcoran-funded nonprofit directed by McCullagh that focused on neighborhood revitalization. She became drawn to the vision of mixed-income housing, which Corcoran pioneered in Boston.

In 2020, after earning dual master’s degrees in urban planning and real estate development at MIT, Slamin and her husband, Robert Slamin, MCAS ’12, relocated to Washington, DC. While pregnant with their first daughter, Slamin opted to start her own firm, Embolden Real Estate, with a mission to develop mixed-income housing. Although she’d enjoyed working in community development, she says, “I realized I didn’t like being the middle person—I wanted to be the developer.” Slamin began looking for an opportunity to launch a project.

By 2022, she’d identified a target: a six-story, 23-unit, rent-controlled building in Washington’s Kalorama district. The neighborhood features single-family homes typically selling for between $1 million and $10 million. The beigebrick building was up for sale, and tenants were concerned about the reputation of a developer who wanted to buy it. So the tenants organized and, utilizing a program that allows residents the right of first refusal, searched for a partner to buy it. When tenants met Slamin, they were sold. “She really understood our predicament … how residents loved it here, and why it was important,” says former tenant association leader Ashley Warren. Slamin applied for grants, lined up financing, and in May 2023 closed on the building for $9.05 million. She renamed the property The Bobbi, after her daughter. (She has since had a second daughter.)

Before beginning a $10 million rehab later this year, Slamin must relocate all residents to temporary homes and pay all associated costs. Then her contractors will do a gut renovation, restoring historic features and adding new elevators, solar panels, a green-energy upgrade, and new amenities including a library and fitness room. Although Slamin loves the building, when she discusses the project, she talks mostly about the benefits of living in a great neighborhood. “It’s safe, it’s near great schools, and it’s near affluent individuals so people can grow their networks,” she says.

When construction is complete at the start of 2026, existing rent-controlled residents can move back in. When units turn over, they’ll be offered to families earning less than $130,000 a year, at rents ranging from $1,000 to $3,500— half the cost of comparable market-priced apartments in Kalorama. More than architecture or construction, it’s this aspect—the impact on residents—that makes Slamin excited about development. “I’m not into picking which marble goes into a luxury bathroom,” she says. “My interest is in providing stable, affordable, high-quality housing.”

A Difficult Conversation about Retirement Savings

“Andrew and I usually have opposing views—he is conservative, and I’m more liberal,” says Alicia Munnell, director of Boston College’s Center for Retirement Research, speaking of Andrew Biggs, an American Enterprise Institute senior fellow. In 2017, The Wall Street Journal highlighted their differences under the headline, “Is There Really a Retirement-Savings Crisis?” Biggs argued there wasn’t a crisis, while Munnell said there was.

Now, the two retirement experts are combining forces. Earlier this year, the center published a proposal by Munnell and Biggs titled “The Case for Using Subsidies for Retirement Plans to Fix Social Security.” In it, they make a bold statement: “The case is strong for eliminating the current tax expenditures on retirement plans, and using the increase in tax revenues to address Social Security’s longterm financing shortfall.”

Tax deductions for contributions to retirement plans primarily benefit high earners while failing to boost national savings significantly, according to the

research. They suggest that if the federal government eliminated tax benefits for 401(k)s/IRAs, it would collect an additional $185 billion in tax revenue. That would help shore up Social Security, which will be unable to pay full benefits in about 10 years without any policy changes.

The proposal drew extensive media coverage, which didn’t surprise Munnell, who is cited regularly in The New York Times, The Wall Street Journal, and other outlets. She and her team were a little stunned, though, by the volume of often-heated reactions on social media.

“The goal of the brief wasn’t to create controversy, or to get Congress to take immediate action,” says Munnell, who is the Peter F. Drucker Chair of Management Sciences. “We wanted to start a dialogue.”

Some critics argued that employers would have less interest in offering the plans if their workers were to lose the tax benefit. On this point, critics might have missed the fine print: The proposal also calls for a federal mandate that all employers must either provide a plan of their own or contribute to a national fund for that purpose. With or without this particular plan to fix Social Security’s shortfall, Munnell’s end goal is clear: “I want people to be able to live in dignity after they’ve spent their entire lives working.”

MARGIE ZABLE FISHER

’89

2024 CARROLL CAPITAL 9 ILLUSTRATION BY MIKE LEMANSKI

ON PURPOSE

HOW ANYONE, NOT JUST THOSE OUT SAVING THE WORLD, CAN

FIND MEANING AND HOPE ON THE JOB.

BY SALLY PARKER

When people think about doing work that’s meaningful, one picture that likely comes to mind is someone in a helping profession—say, a hospice nurse tending to a dying patient in their final days, providing comfort and easing their transition. ¶ Caring for the sick and dying is one way people find purpose in their work, but there are many more, and they look wildly different. These experiences give rise to what Aristotle called eudaimonia, a sense of flourishing. ¶ “It applies to everyone and not just people in nonprofits or stereotypically meaningful jobs,” says Ben Rogers, assistant professor of management and organization. “That worth can come from what you’re doing, it can come from

who you’re doing it for. It can be a million different things.”

For some, it’s working in an organization that strives to solve society’s challenges, fueled by a sense of hope. Others derive satisfaction from self-improvement and mastering new skills, or doing a difficult task that requires sustained effort—uplifting experiences that a financial analyst can have just as much as a social worker. For many, it’s not the job itself that is a source of meaning but what it enables outside of work—the ability to provide for a family, for instance. “Everyone falls into one or more of those buckets,” Rogers says. “It’s really difficult for people to sustain work for any meaningful amount of time if they’re not doing it for some greater purpose.”

One challenge is that people often don’t connect the meaning they find in work with a larger life purpose, Rogers says. Because jobs

often demand sacrifices of time and effort, it’s natural to think there’s a trade-off between meaning at work and fulfillment in life.

But the two aren’t mutually exclusive, he says: Work is part of life, not a separate domain. What people find meaningful in life can find echoes in their work, and vice versa. For example, someone who enjoys working with others in their town on quality-of-life goals may get that same endorphin rush leading a feel-good community project at work. “People don’t often think of how these things fit together and how they can match up or be complementary,” Rogers says.

With his collaborators, Rogers has studied how personal narrative can boost meaningfulness through a “growth mindset” at work. A person may believe she can acquire a new skill, or may be convinced she can’t because it was hard one time when she tried it. The resulting story that she tells herself drives the level to which she finds work meaningful, they found. In one of the studies, an openness to learning new things not only created a greater sense of meaning at work but led to a desire to help other employees who also want to grow.

These narratives throw light on what mythologist Joseph Campbell called the hero’s journey. In this classic plot structure, the protagonist faces and overcomes challenges, leading to personal growth and transformation. To understand this narrative in the context of work, Rogers guided participants through a writing task to retell their life and career stories as a hero’s journey. “When people saw their journeys in their careers as a hero’s journey, they felt like their

ILLUSTRATION BY LUISA JUNG 10 CARROLL CAPITAL 2024 Ventures Insights

jobs themselves were more meaningful. They were able to see the results of this big journey, this story that they’re a part of,” he says.

Finding meaning through work is a central theme of recent papers by faculty in the Management and Organization Department, on topics ranging from the mixed feelings that gig grocery shoppers had about public praise of their work during the Covid-19 pandemic (Assistant Professor Curtis Chan) to how female managers, surprisingly, are more likely than male managers to limit gender equity policies (Assistant Professor Vanessa Conzon).

Judith Clair, professor of management and organization and a William S. McKiernan ’78 Family Faculty Fellow, has studied the role of hope in medical settings and in organizations that tackle entrenched global problems. In the daily grind of often-difficult work, it pulls people together toward a meaningful goal.

But hope can be crushed. In one organization Clair studied, a center for women who had been sexually exploited, staff and clients were devastated when a client who had become a role model for her success overcoming addiction died of an overdose. They began to question the value of their work. “The fact of her success supported the hope culture itself,” Clair explains, but this tragedy showed how “failures can be extremely emotionally difficult for the collective.”

And yet, setbacks can amplify meaning when they lead to renewed commitment. Clair says, with a splash of hope: “Meaning still can be found in a variety of really horrible circumstances—times when hope seems hard to achieve.”

Speaking More Softly

“State of Corporate Citizenship” report finds that companies are treading more carefully on issues of corporate responsibility.

With critics on all sides and regulators breathing down on them, companies looking to do the right thing are still pushing ahead on social and environmental issues. But they’re doing it a little more quietly.

That’s according to a newly released report by the Boston College Center for Corporate Citizenship. In the biannual survey, nine out of 10 executives reported that during the previous two years, leaders in their company had taken a stand on ESG (environmental, social, and governance) concerns—a robust 54 percent increase since 2020. Approximately 850 senior-level executives participated in the survey.

At the same time, these leaders are turning down the volume. “Some are stepping back from the marquee, but they’re not stepping back from social and environmental investments,” says Katherine Smith, executive director of the center, which is the largest organization of its kind with 500 corporate members that bring almost 10,000 employees to its programs each year. Quieter steps range from improving gender-equity policies to reducing plastic waste, moves that also align with business goals like employee retention and cost saving.

Companies are also shifting their public advocacy. The center’s “State of Corporate Citizenship” survey shows that in 2022, corporate leaders were voicing a clear stand

“There’s a lot of frustration about the continued fragmentation of reporting standards. Right now it’s the wild, wild West in terms of how companies are addressing these issues.”

Katherine Smith

on gender and racial equity and inclusion. That remains a central priority for the companies, but now their public statements are more likely to highlight issues like sustainability and climate change, which are viewed as less controversial. Still, because ESG in general has become a political hot potato, that, too, is a softer message. These changes reflect the intense pressure companies are under from various quarters, according to Smith. Corporations are facing the competing demands of employees, activists, and politicians of all political stripes. “It’s a sea shift in the ESG space, and we’re experiencing the storm of that shift right now,” Smith says.

On the regulatory side, new rules in the European Union are taking effect, and US companies are not prepared, Smith says. While US laws focus mainly on greenhouse gases and carbon emissions, the EU’s Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive is more sweeping. It calls for a clear and comprehensive picture of what companies are doing on social and environmental issues.

American firms doing business in Europe, including many members of Smith’s organization, will be expected to comply. Some are scrambling to understand the requirements—but others are looking away. That’s partly because the regulations are complicated, with a raft of standards, each with its own requirements. “So there’s a lot of frustration about the continued fragmentation of reporting standards” in both the EU and US, Smith says. “Right now it’s the wild, wild West in terms of how companies are addressing these issues.”

SALLY PARKER

2024 CARROLL CAPITAL 11 PHOTOGRAPH BY KELLY DAVIDSON

Ventures Enterprise

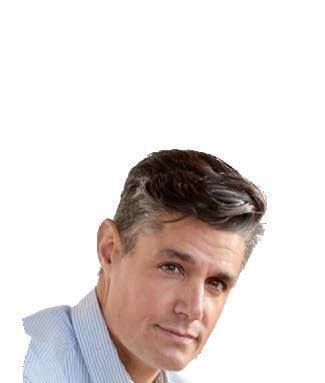

CARRYING THE BALL

NATALIE WHITE ’20 IS WRITING A LOVE LETTER TO WOMEN’S BASKETBALL WITH MOOLAH KICKS.

BY JACLYN JERMYN

The first word that Natalie White ’20 learned to say was “ball,” so it’s fitting that at 26 years old, she’s the founder and CEO of the top women’s basketball brand, Moolah Kicks. While her business instincts have landed her products in stores across the country, her driving force is less about entrepreneurial dreams and more about building a community for women’s basketball fanatics just like her.

White loved sports from a young age, playing soccer, football, lacrosse, and basketball all by the time she was a high schooler. She began her college search interested in Boston College—White wanted to study business and her older sister Whitney was already on the Heights—but what sealed the deal was getting to try out for the varsity lacrosse team, even after a high school injury. “Boston College was the type of school I wanted, where everyone gets a shot,” White says.

She didn’t end up on the lacrosse team, but while exploring academic life at the Carroll School as a finance and entrepreneurship student, she decided to join the women’s club basketball team. She later also became a manager for the women’s varsity basketball team. Despite spending so much time thinking about basketball, White hadn’t thought much about the fact that she was wearing men’s sneakers on the court.

The shoe choice wasn’t a preference, but a necessity. The vast majority of basketball sneakers

marketed to women are just smaller versions of men’s sneakers. “I saw this ad with four WNBA players holding sneakers named after NBA players,” she says. “You can be the best in your game, but at the peak of your career, you’ll still be promoting products made for someone else.”

Women’s feet typically have a higher arch than men’s, not to mention a slimmer width, a narrower heel, and a shallower lateral side right above the toes. “When we wear shoes built for the male foot, we’re more at risk for knee, ankle, and leg injuries,” White explains. Seeing that advertisement was the moment she knew she had to change the industry.

“The toughness of the industry is matched by how tough she is,” says John Fisher, a senior marketing lecturer and former CEO of athletic shoe and clothing company Saucony. Fisher was a mentor to White in her time at Boston College, but he initially tried to steer her toward any other career path. He told White: “Basketball is the most important category in the athletic footwear market. When they spit on you, it’s gonna be like a fire hose pounding your way.”

White took the reality check in stride. “It’s not about what I want. It’s about what the community needs,” she says. If no one else was solving the problem, why couldn’t it be her? “The outstanding attributes that she had

from minute one were the stubbornness and drive to succeed,” Fisher says. To White, Moolah Kicks is a product of Boston College, especially the women’s basketball community on the Heights. “They believed in [Moolah] when it was just an idea,” she says of her college teammates, who supported her dream by assisting with everything from initial concept ideation to testing out early prototypes. “That is the reason we’re here today.”

A year after graduating, White launched a Moolah Kicks presale campaign without having a single pair of sneakers ready. “There was one shoe and it wasn’t even all the way put together,” she says, laughing. That didn’t stop her—White and her friends made Moolah Kicks shirts and shot a promo video in Brooklyn. As the story got picked up by The Boston Globe and industry publications like Sneaker Freaker, Moolah Kicks saw $30,000 worth of sales within the first three weeks of the campaign. Then White heard that Dick’s Sporting Goods was looking to put an emphasis on women’s sports. She leveraged her industry connections, aiming for an introduction. It felt like a full-court shot—a bold move to get Moolah Kicks the attention it deserved.

She got her chance to pitch to Dick’s in June 2021. By that fall, Moolah’s first production run was in 140 Dick’s stores—a number that has grown to 570 stores nationwide. Moolah Kicks now counts Shark Tank personality Mark Cuban among its investors

and has endorsement deals with WNBA players Courtney Williams and Sug Sutton. White also landed a spot on the 2024 Forbes 30 Under 30 list.

“Being a woman in sports, it’s a smaller community,” says Boston College women’s club basketball team president CeeCee Van Pelt ’24, a finance and accounting student. “Having people like [Natalie] at the forefront, it’s really encouraging for all of us.” The women’s club team currently wears Moolah sneakers even though New Balance is the official athletic footwear and apparel provider for all Boston College varsity teams. “I used to play with men’s shoes. You don’t realize they hurt until you put on a shoe that actually fits,” she says.

White is currently a jack-of-alltrades for Moolah, which makes her grateful for the Carroll School accounting and operations classes she took, as well as the college art classes that taught her about design. Moolah recently added warmup gear and a low-top sneaker model to its product line, and it’s “continuing to get shoes on feet,” White says. “There are challenges every day, but you have to see those as opportunities. How do we keep getting better every season?”

The answer is simple: She has to make sure women and girls know there are basketball sneakers made by and for women ballers like them. “The goal for me was never that I wanted to start a company,” White says. “What I wanted was for the world to see women’s basketball the way that I do.”

“The goal for me was never that I wanted to start a company. What I wanted was for the world to see women’s basketball

the way that

I

do.” —Natalie White ’20

PHOTOGRAPH BY JOSHUA DALSIMER

12 CARROLL CAPITAL 2024

Natalie White ’20 shows off some of her Moolah Kicks, which counts Mark Cuban among its investors and has endorsement deals with WNBA players Courtney Williams and Sug Sutton.

Natalie White ’20 shows off some of her Moolah Kicks, which counts Mark Cuban among its investors and has endorsement deals with WNBA players Courtney Williams and Sug Sutton.

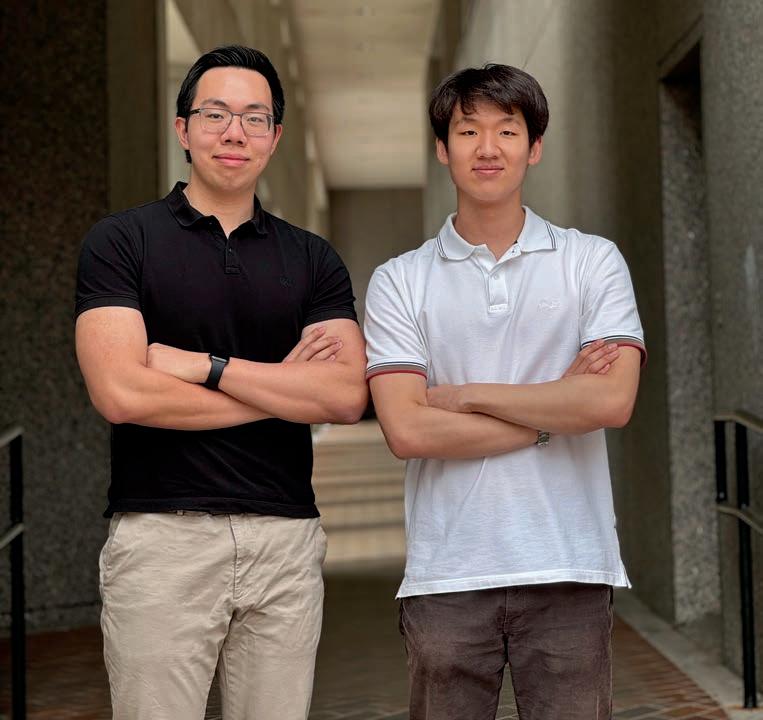

AI CAN WRITE, CALCULATE, AND EVEN JOKE...

BUT CAN IT KNOW WHEN YOUR BOSS IS HAVING A BAD DAY?

BY TIM GRAY

If you’ve read the headlines about artificial intelligence, you might believe it will turn us all into horses. Automobiles, of course, changed horses from essential laborers to luxury purchases in just a few years. AI, doomsayers predict, will do something similar to us humans. It’ll take our jobs and leave us to fill niche roles.

Professors at Boston College’s Carroll School of Management who study AI call predictions like that overblown. Yes, AI will revolutionize the workplace, and, yes, some kinds of jobs will disappear. The McKinsey Global Institute, for example, has estimated that activities accounting for 30 percent of hours currently worked in the United States could be automated by 2030. But Carroll School scholars argue that people who learn to use AI to increase their productivity could end up better off. As they see it, AI-adept folks will be able to work faster and smarter.

“I don’t think our real concern right now is about overall job loss,” says Sam Ransbotham, a professor of business analytics. “What’s going to happen is you’re going to lose your job to someone who’s better at using AI than you are, not to AI itself.”

How do you become an AI ace? It’s doable for many people, says Ransbotham, who’s also the host of the podcast Me, Myself, and AI. You don’t have to become an expert, just the most knowledgeable person in your office.

With curiosity and diligence, most anyone can learn enough to figure out how to apply AI on the job, he says. The way to start is with play. Go online and play around with ChatGPT, OpenAI’s chatbot. Try, say, having it write first-draft emails or memos for you. (But fact-check anything you use: ChatGPT and other large language models can sometimes offer up “hallucinations,” information that sounds plausible but is false.)

“AI tools are accessible to the masses,” Ransbotham says. “That’s an interesting change. Most people don’t play with Python

ILLUSTRATION BY DAVID PLUNKERT 14 CARROLL CAPITAL 2024 Ventures Application

code.” He uses AI to generate the background images for slides in his presentations. “For me, images on slides fall into the good-enough category. I want my computer code to be awesome, but the images I use on slides can just be good enough.”

In speaking of “good-enough slides,” Ransbotham was alluding to the peril of leaning too heavily on AI: what he calls the “race to mediocrity.… You can use an AI tool to get to mediocre quickly,” he explains. ChatGPT, for example, can give a draft of an email or memo in seconds. But its prose will be generic, lacking color and context, because ChatGPT “averages” the prose it finds on the web. Stop there, and you’ll end up with average prose.

Another way to tool up on AI is to read and listen. Plenty of established publications, like Wired and Ars Technica, as well as newer ones, like Substack newsletters by Charlie Guo and Tim Lee, cover AI. Ditto for podcasts like Ransbotham’s. As you explore, understand that, despite the hype, the technology does still have real limitations, says Sebastian Steffen, an assistant professor of business analytics. “I tell my students that ChatGPT is great for answering dumb questions,” he says. “For factual questions, it’s quicker than Wikipedia.”

But AI can’t make judgments, which is often what work entails. Your boss may ask you to help formulate strategy, allocate staff time and resources, or determine whether a worrisome financial indicator is a blip or the beginning of something bad. Facts can inform those decisions, but facts alone won’t make them.

Steffen cautions that it may take several decades before we really understand how to use AI and the best ways to incorporate it into our workplace routines. That’s typical of big technological rollouts. Even AI’s inventors may not see the future as clearly as they claim. “Alfred Nobel invented dynamite to use in mining, but other people wanted to use it for bombs,” he says. That troubled Nobel, a Swedish chemist, and was one of the reasons he funded the Nobel Prizes.

Even in an AI world, humans will still likely have plenty to do, says Mei Xue, associate professor of business analytics. “Think about doctors—we still need someone to touch the

patient’s belly” to get subtle information that sensors miss, she says. Robots can move pallets in warehouses, but they haven’t learned bedside manner. Xue says humans will likely continue to fill roles that require “talking to clients, meeting with customers, reading their expressions, and making those personal connections—we can gather subtle impressions that AI can’t.”

AI can’t tell whether the crinkles at the corner of someone’s eyes are from a smile or a grimace. So soft skills will still be rewarded. Brushing up on those may pay off.

Even in humdrum workplace communications, like those endless emails and memos, there will likely be a continuing role for us humans, Xue says. “What’s unique with us humans is personality, originality, compassion—the emotional elements.” ChatGPT can generate jokes, but it can’t know your coworkers or clients and what will resonate with them.

Similarly, you can let AI write your cover letters for jobs or pitches to clients. But you might fail to stand out, Xue says. ChatGPT “is searching for what’s available on the internet and putting together what’s best based on probability,” she explains. “For now, it can’t provide originality.”

Xue adds that one can find the need for a human touch, or voice, in unexpected places. “This weekend I was listening to some books on an app in Chinese. I found they offered two types of audiobooks— one read by a real person and one by an AI voice. I didn’t like the AI readings. They sounded fine but had a perfect voice. When you have a real person read, you feel the emotion and uniqueness.”

IN THE CLASSROOM

Teachable Moment

The Carroll School gives professors three options for using AI as a tool.

BY ELIZABETH M c GINN

With the launch of ChatGPT in Fall 2022, many educators feared that AI would completely upend academic integrity, a concern that many Carroll School faculty initially shared. “At first [the reaction was] ‘we have to stop this menace,’” says Jerry Potts, a lecturer in the Management and Organization Department. Still, a handful of professors started making a compelling case: AI wasn’t going anywhere—instead, the Carroll School would have to rethink how to use it academically. By the following fall, three new policy options had been presented: Professors could completely prohibit AI, allow free use with attribution, or adopt a hybrid of the two options.

Some faculty members, like Potts, have fully embraced AI as an educational tool. In his graduatelevel corporate strategy class, one project tasks students with pitching a business plan for a food truck with only 30 minutes to prepare.

Potts has found that while AI often helped with organizing the presentations, it was humans who came up with the most creative ideas overall. Bess Rouse, associate professor of management and organization and a Hillenbrand Family Faculty Fellow, opted for a hybrid AI approach and allows it only for specific class assignments. In one case, she instructed students to use ChatGPT in preparing for peer reviews, which minimized the awkwardness of critiquing other students’ work.

“There is less concern that this will be the ruination of teaching,” says Ethan Sullivan, senior associate dean of the undergraduate program. “We’ve instead pivoted to how AI complements learning.” For his part, Potts is optimistic. He says that if professors stay on top of this technology and adapt their courses accordingly, “We should be able to take critical thinking to another level.”

2024 CARROLL CAPITAL 15

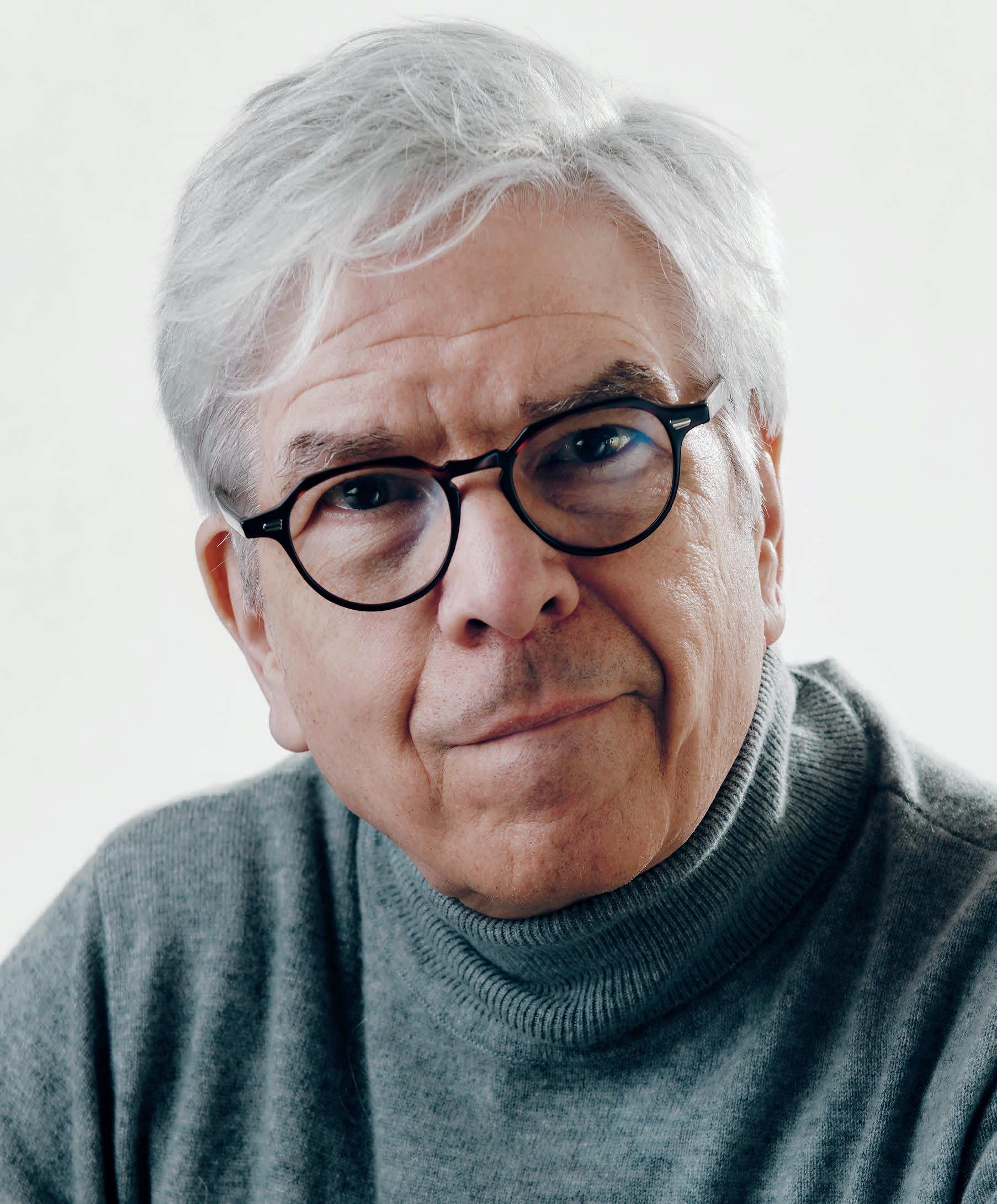

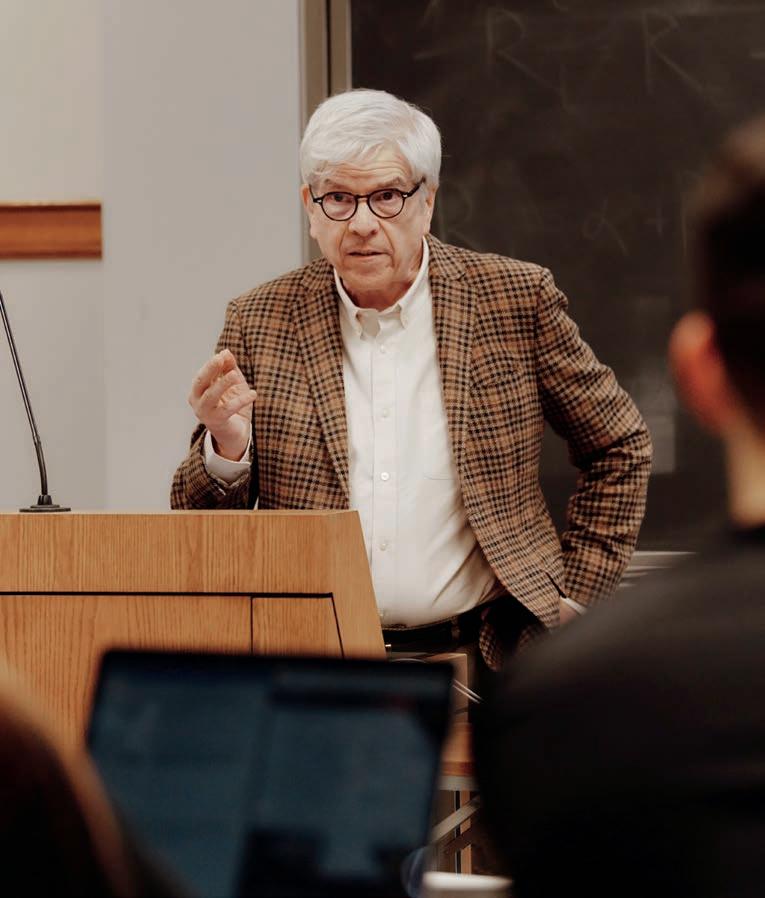

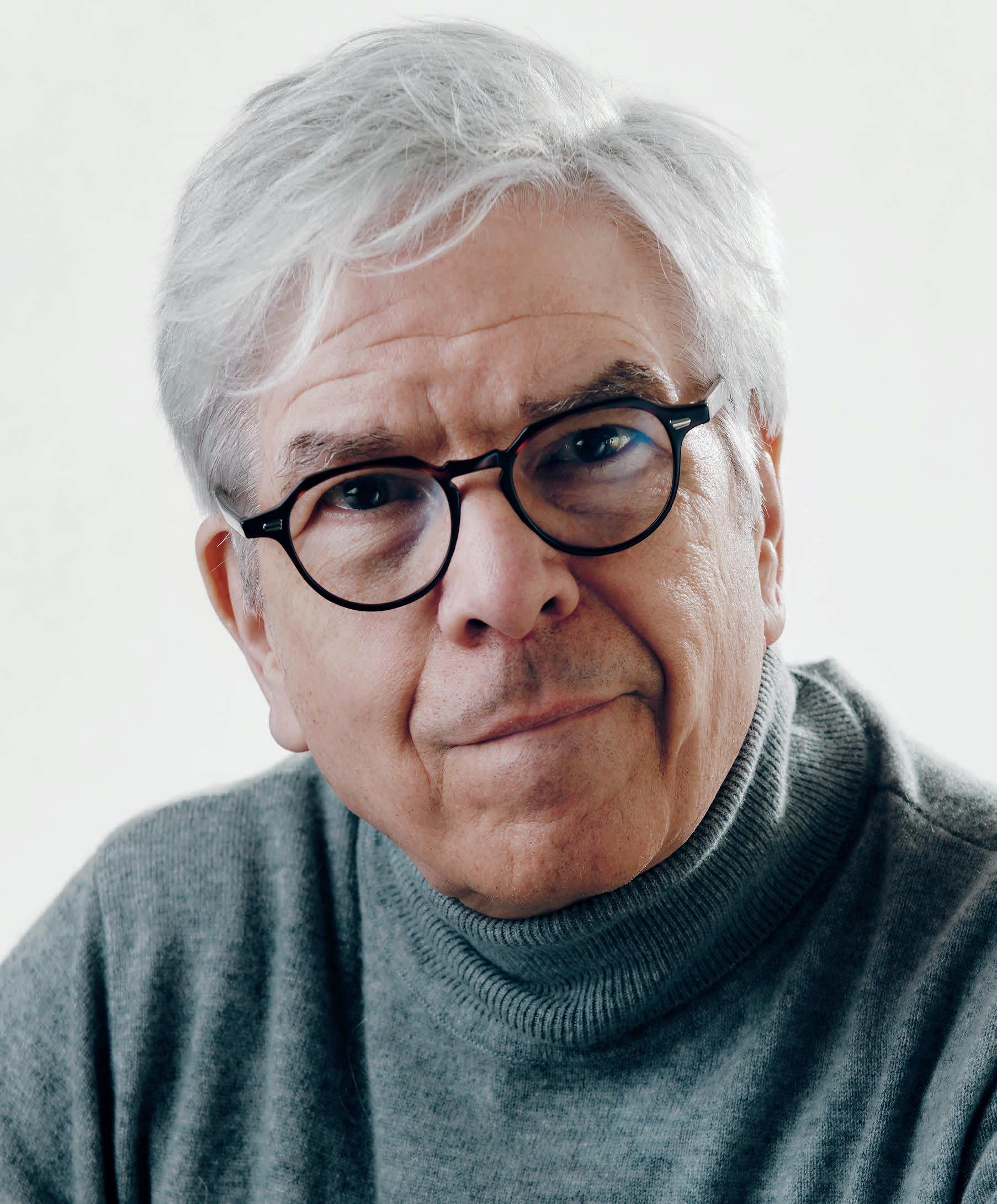

NOBEL AT A LAUREATE REMAKES HIMSELF BOSTON COLLEGE

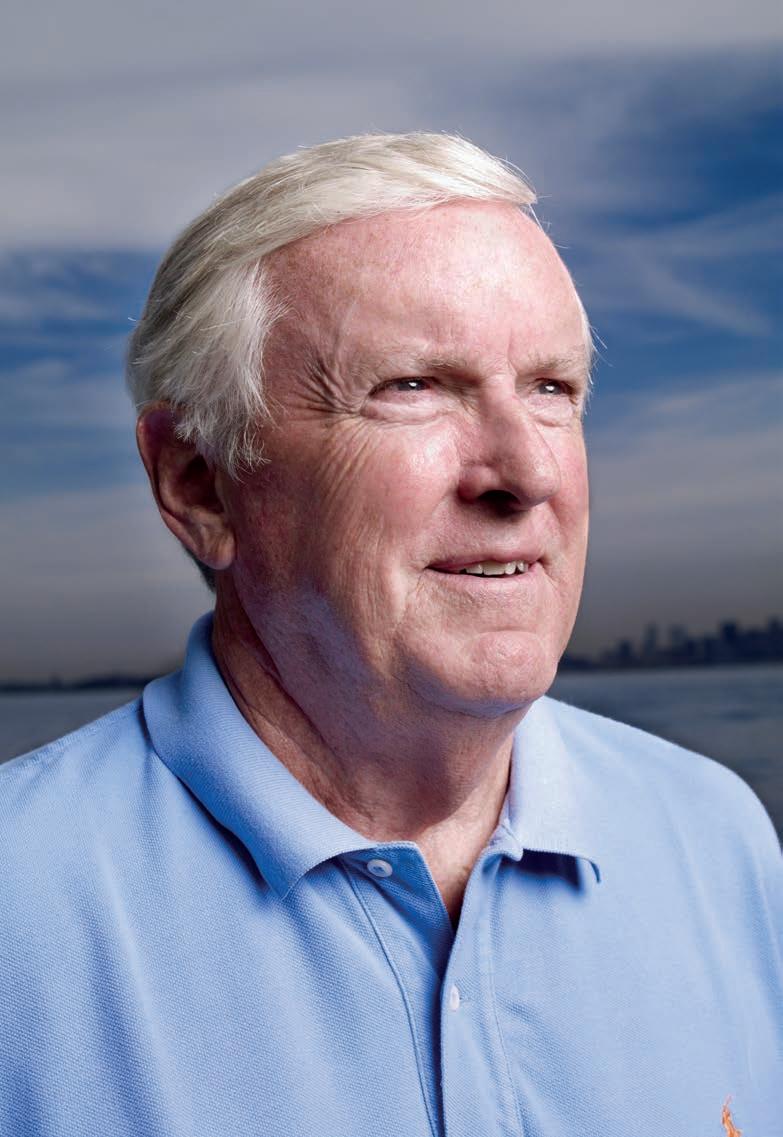

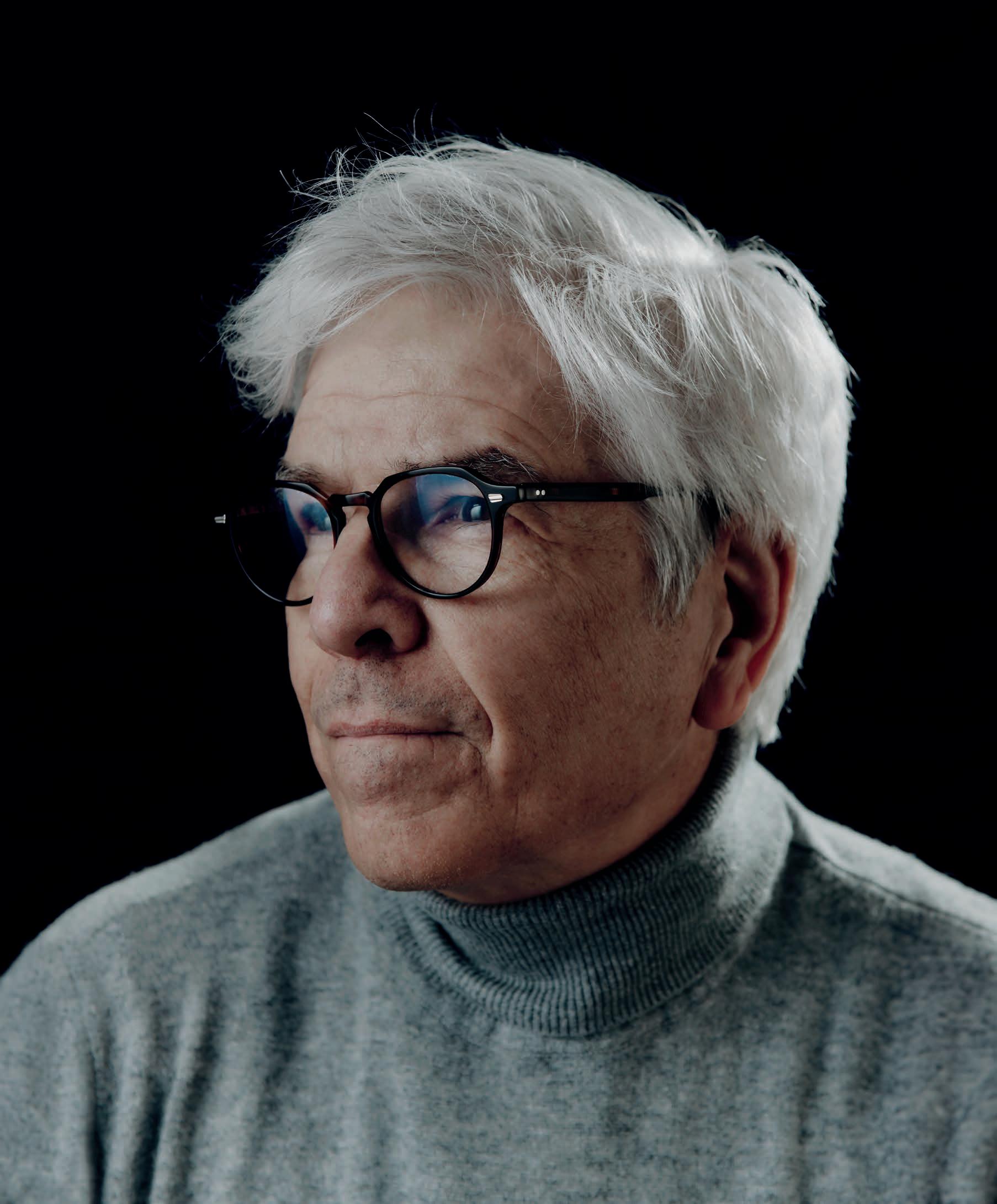

Paul Romer won a Nobel Prize in economics for his upbeat theory of growth, which shined a light on how ideas, rather than mere things, lead to economic expansion and human progress. Now he’s teaching coding and taking on threats in the digital realm that he fears could forestall new discoveries. Can he change the world twice?

By WILLIAM BOLE

17

Photographs by TONY LUONG

Inside a tiered lecture room in Higgins Hall, Carroll School of Management professor and Nobel laureate Paul Romer is speaking at a gathering of physicists and peppering his lecture with terms of art that they’d know well, like “convexity,” a mathematical property featuring tangent lines on a graph. The renowned economist is plotting out theories of growth that trace back to physics, including the relationship between inputs and outputs of energy. Minutes into the lecture, a professor in the front row interrupts Romer, challenging the idea that if you double all of the inputs (say, the people, land, and tractors), you’ll double the outputs (food for those people). The objections continue, and a few of the professor’s colleagues try to shush him. But Romer, the Seidner University Professor who directs Boston College’s new Center for the Economics of Ideas, is unperturbed. He’s clearly enjoying the give-andtake, and he salutes his interlocutor. “He’s showing me respect,” Romer tells the colleagues. “This is how you show respect—you disagree. You engage.”

The whole scene, not just the exchange but the curiosity of an economist floating into the orbit of physicists, begins to sketch a portrait of Romer the scholar. For one thing, he doesn’t sit comfortably in his own discipline, chiming with the preferred ways of understanding people and economies. He isn’t sitting at all in an economics department; he’s a finance professor at a school of management. To be frank, Romer isn’t resting easily at the Carroll School either. Though he has tossed himself into the daily stir of a topranked finance department, he keeps popping up in disparate places on the Heights, discoursing with political scientists on the nature of citizenship in a globalized world; hanging with the physicists in Higgins late last year; back in Fulton, presenting his research to a standing-roomonly crowd of Carroll School faculty; and wending his way into other conversations. The 2018 Nobel Prize winner in

economics isn’t even teaching economics, or finance for that matter. His first course at Boston College this past spring was “Digital Self-Defense with Python,” a coding class (he taught himself Python in 2018 after a stint as the World Bank’s chief economist). Why is Paul Romer teaching coding to undergraduates? And why is he having so much fun being cross-examined at a physics colloquium?

It’s all about the ideas.

Romer won the Nobel for his “New Growth Theory,” which holds that knowledge and ideas are the key drivers of economic growth. Previous research had highlighted the role that technology plays in expanding the quantity and quality of goods and services, but Romer turned the accepted wisdom on its head, demonstrating the essential difference between physical objects and ideas. Basically, objects are subject to the laws of scarcity; as more people tap a new freshwater source in the developing world, for instance, there’s less of it to go around. On the other hand, ideas (which he likes to call “recipes”) are endlessly plentiful and reusable once they’re discovered.

One of his favorite illustrations is a bracingly simple idea concocted several decades ago in refugee camps in Bangladesh. Some medical personnel began mixing glucose, sugar, and a little water, and found that this recipe, in just the right amounts, would cure children suffering from deadly dehydration. Since then, the solution has saved millions of lives in poor nations, because ideas are replicable. The life-saving idea of oral rehydration therapy could be used over and over, at scarcely a cost, and administered by parents in their own homes.

At the Carroll School’s Finance Conference two years ago, Romer spoke of such breakthroughs as he brushed aside a national mood of pessimism. “Throughout history, things get better and better, and they get better faster and faster. People come up with ideas that give us so many ways to do more with less,” he said. “It’s not even remotely possible that we’ve run out of new things to discover.” This is vintage Romer optimism, and yet, the proclaimer of economic progress has been raising alarms that have grown more urgent. He talks about what he sees as a business culture in which lying and deception have been normalized, about increasingly untrustworthy digital messages that hamper the flow of ideas, and other trends that would derail the train of human progress. Romer, the acclaimed optimist, is worried.

During an interview in his fifth-floor Fulton Hall office, he wants to make it clear that his optimism has always been a product of empirical evidence, not so much his personality. “I don’t have a naturally sunny disposition,” says Romer, who keeps a fairly steady look on his face, at times wearing a slight grimace, at times offering a strong suggestion of a smile. He cuts a striking figure with his mane of pearly white hair, dark brows, and black-framed glasses.

Growing up in Denver, Romer could see the world as a friendly place. He lived in a tree-lined city neighborhood with squads of kids playing kickball on the streets. His father, Roy, was a lawyer, small business owner, and politician who eventually became Colorado’s governor; his mother, Beatrice, was an advocate of early childhood education who, as first lady, spearheaded Colorado’s statewide preschool program. They

18 CARROLL CAPITAL 2024

had seven children. “We weren’t wealthy, but we were fortunate. Our parents created an environment for learning, exploring, and developing a taste for understanding the world,” Romer recalls. He spent summers in the mountains outside Denver, working on his father’s ranch and tending to horses and cattle.

It was, though, the 1960s, and the wider world was convulsing with protests and assassinations. The upheavals hit home for Romer when his father, after losing a US Senate election as the Democratic Party’s nominee in 1966, was ostracized by his party for opposing the Vietnam War. Rather than backtrack, Roy Romer chose to leave politics, a decision that made a lasting impact on his son, 11 years old at the time. Paul Romer says the lesson was: “If you reach a point in your career where

“Throughout history, things get better and better, and they get better faster and faster. People come up with ideas that give us so many ways to do more with less. It’s not even remotely possible that we’ve run out of new things to discover.”

SEIDNER UNIVERSITY PROFESSOR PAUL ROMER

you feel you have to compromise to continue on the path you’re on, just change the path.” His father returned to politics a decade later, when he became secretary of agriculture in Colorado; he served as governor from 1987 to 1999. In a way, family history repeated itself during the 1990s. Paul Romer wasn’t exiled from academia, but he says the prevailing winds—blowing, notably, from economics professors at the University of Chicago, his undergraduate and PhD alma mater—were complicating his path to publication. Some influential economists were throwing cold water on his findings about the growth effects of ideas. “I got to a point where my voice couldn’t be heard. I couldn’t get the word out through traditional journals,” he says. “I hit a roadblock and was forced to either compromise or go do something else.”

Applying his father’s lesson, Romer chose to leave the economics profession and stake out new passions. In 2001, he founded an educational technology company, Aplia, which created online exercises to reinforce classroom learning; he sold the company to Cengage Learning six years later. After that, Romer turned to urbanization, launching the concept of Charter Cities, newly created municipalities in developing nations. He became founding director of New York University’s Marron Institute for Urban Management.

Asked if he felt vindicated by the Nobel Prize, Romer says, “What would make me feel vindicated is if people were more willing to engage with the general questions I’ve been asking.”

Does this mean that economists were unswayed by his growth theory? Hardly, says Michael Kremer, who won a Nobel Prize in 2019 for his research on development economics in lower-income countries. “Paul’s work sparked an explosion in research on economic growth in the ’90s. I think his work was widely appreciated very rapidly,” says Kremer, now teaching at the University of Chicago. He adds that Romer’s insights “form the core” of how economists today think about growth.

Chad Jones, a Stanford University economist who built his own ideas on Romer’s foundation, says Romer “relaunched the whole field of growth” that had languished for decades, but he points out that it’s hard to change the world twice, and Romer’s subsequent work on growth attracted less interest after his groundbreaking 1990 paper. Jones says it’s partly because Romer “didn’t play the academic game”—for one thing, he wrote in a less technical style than other economists. The Stanford professor also notes that some of Romer’s closest and most prominent colleagues at the University of Chicago didn’t buy into his growth theory, which might have, to an extent, tilted the publishing decisions of some top journals. Romer’s sober

2024 CARROLL CAPITAL 19

“I don’t think anyone really needs to be anonymous. You wouldn’t trust someone who insisted on meeting with you in a gorilla mask, not wanting to tell you who they are. And you shouldn’t want that digitally either.”

SEIDNER UNIVERSITY PROFESSOR PAUL ROMER

assessment is that economists overall have gone from ignoring the role of ideas to making it a “footnote” in their work.

Romer often says that management professors have been perhaps his most engaged audience, owing to the implications of his research for innovation driven by ideas. One of those academics was Peter Drucker, the father of modern management theory. Another was the Carroll School’s John and Linda Powers Family Dean, Andy Boynton, who first connected with Romer by email in the early 1990s. In 2011, Romer wrote a blurb for Boynton’s book The Idea Hunter: How to Find the Best Ideas and Make Them Happen, coauthored by Bill Fischer; they argued à la Romer that a shortage of ideas inhibits innovation much more than a shortage of things. The Boynton-Romer connection continued with the invitation to address the 2022 Finance Conference, after which the dean recalls asking him, “Would you ever consider working here?” Romer replied, “I might.” After numerous conversations with Boynton and University Provost David Quigley, Romer arrived at the Carroll School in Fall 2023, the first Nobel laureate to serve on Boston College’s permanent faculty. He commutes weekly between Chestnut Hill and New York’s Greenwich Village, where he lives with his wife, Caroline Weber, and their five dogs. Notwithstanding his forays beyond Fulton, Romer has embedded himself in the Finance Department, attending lunch conversations, mentoring junior faculty, and participating in interviews with prospective faculty, who are often surprised to see him. “He’s already made an impact on our department,” says Haub Family Professor Ronnie Sadka, department chair and senior associate dean for faculty. “He’s very interpersonal, very approachable, quick to contribute.”

For his part, Romer calls Boston College “a place where people care about integrity and values. It’s part of why I like the intellectual community here.” It also meshes with his mounting concern about companies, especially in the tech sector, “adopting business models that involve dishonesty, misrepresentation, and exploitation of the customers,” he says. “They feel they’re in these winner-take-all contests where they have to win at any cost or die. And once they win, even if they’ve damaged their reputation, they’re dominant. They’ve cornered the market.” During an interview in April, he cited a plethora of examples, including headlines that day about Google agreeing to destroy billions of data records to settle a lawsuit that claimed it secretly tracked people’s private browsing, even though the company had earlier said it would be impossible to destroy the data. Romer acknowledges that it’s hard to produce data on something as nebulous as an increase in dishonesty, but of course we’re talking about someone with a history of bringing dimly lit truths out of the haze.

On a raw and rainy night in April, Romer is setting out for his coding class, which will take up ways of authenticating digital transmissions. This isn’t theoretical for Romer, whose X (Twitter) account was impersonated with a slightly tweaked handle in 2023; the fake Romer messaged some of the followers, inviting them to invest in a dubious cryptocurrency fund. (Now off social media, Romer continues to blog at paulromer.net). “It could be a social media message, an email, a spreadsheet, whatever,” he explains while taking the stairs four floors down to class. “You can’t trust anything unless you know who’s the person who vouches for it, someone who has a track record of being reliable. You can’t trust the content inside those messages.” His solution, easier said than done, is for the sender to put a “digital signature” on the message that the recipient can verify, which reveals the sender’s identity and ensures that no one has tampered with the message.

This is his ambitious project as founding director of the Center for the Economics of Ideas, where Romer, with help from Business Analytics Professor Sam Ransbotham, is working on practical solutions. The chief goal is to develop user-friendly software that would enable any reader to sign and verify files they receive; he’s testing out the software partly by having students work on prototypes. But as Romer begins discussing authentication during class, he gets pushback from some students who want to keep open the possibility of anonymity, which a digital signature would undo. One young man remarks that whistleblowers, for example, need to be anonymous “or else they’re vulnerable to attack.” Romer responds that false accusations by trolls and nameless whistleblowers have become a worrisome trend in academia and other circles. “I don’t think anyone really needs to be anonymous,” he says. “You wouldn’t trust someone who insisted on meeting with you in a gorilla mask, not wanting to tell you who they are. And you shouldn’t want that digitally either.” But the students—members of the digital generation—seem at ease with the gorilla masks.

For all his concerns (including what he sees as a growing disconnect between corporate power and social benefit), Romer’s empirical optimism remains intact. He always returns to the possibilities of progress and the endless discoveries waiting to happen. That confidence comes through in his moonshot for digital authentication, which takes on fuller significance when you consider how critical digital messaging is to research and the transmission of ideas that propel growth. Romer’s new mission will surely invite skepticism, but his dean says it would be foolish to underestimate him. “He’s changed the world once with his discoveries about ideas and growth,” says Boynton. “Can he do it again, in the digital sphere? I’m betting on it.”

2024 CARROLL CAPITAL 21

IN ANY WAY, SHAPE, OR FORM

Students in the Carroll School of Management spend their years on the Heights charting their own unique paths to adulthood. The University isn’t just standing on the sidelines cheering them on. From academics to extracurricular life, Boston College is shaping the whole experience through formative education.

BY JACLYN JERMYN PHOTOGRAPHS BY KELLY DAVIDSON

O

ON ANY GIVEN WEEK DURING HIS SENIOR YEAR, AIDAN SAID ’24 COULD BE FOUND JUGGLING CLASSES and homework for his two management concentrations plus the theology major he tacked on junior year, carrying out his duties as part of the Air Force Reserve Officers’ Training Corps, hanging out with friends, and somewhere in there also trying to get some sleep. ¶ Said didn’t mind what he refers to as the “go, go, go” pace of his days, but his evening routine of meditation, prayer, and reflection was a nonnegotiable in his to-do list. “That’s the way I digest my day,” he says, explaining that the process of reflection often helped him make sense of his place in the world amid competing priorities. “When you have all these different ideas that kind of clash, it always leaves you reverberating.” ¶ For many, college is a time of great personal growth— students across the globe experience these moments of clashing ideas—but it is the

22

SAID ’24

AIDAN

ability to feel that reverberation, the point where experiences intersect meaningfully, that is integral to a Boston College education. If these years are so formative to students, how exactly is Boston College shaping the college experience? The answer revolves around a concept known as student formation, or “formative education.”

“We don’t own the market around formative education. We’re not the only place that students grow and develop and learn,” says Mike Sacco, executive director of the Center for Student Formation and the Office of First Year Experience. “We’re just a bit more intentional. We have an emphasis on it.”

The broader concept of formation comes from St. Ignatius of Loyola, founder of the Jesuit order, and his way of using his own intellect and reasoning to reflect on his personal experiences. Ignatius saw God as a teacher and himself as a student of the world formed in God’s image—he also envisioned the Jesuits as a religious order dedicated to service and teaching.

Even with its faith-based origins, formative education has become part of the Boston College DNA that touches all spheres of life and learning, religious or secular. “All are welcomed and the University is not a church,” says John T. Butler, SJ, the Haub Vice President of the Division of Mission and Ministry. “Yet, the [Jesuit Catholic] ethos springs from the notion that life is a gift and it’s meant to be lived.”

With so many fields of study, service opportunities, clubs, teams, and events to pick from, Boston College emphasizes a choose-your-own-adventure approach to finding meaning during these formative years. The three primary facets of student formation are intellectual, spiritual, and social growth, but these dimensions can, and almost certainly will, interweave as students explore their options.

Andrew Namkoong ’24 appreciates that the University’s core curriculum allowed him to traverse subject areas from epistemology to business law. “Through the core, you become not just specialized but a well-rounded individual,” he says. He shares a similar sentiment about Portico, the required first-year management course that weaves in threads of ethics, philosophy, and social responsibility. That class is part of the reason he later decided to pursue a philosophy major in addition to his finance concentration. “I didn’t know that philosophy could cross over into the business world,” he explains. Around 50 percent of Carroll School students complete an additional major or minor in the arts and sciences. It’s an opportunity to discover surprising connections. For Namkoong, who describes himself as “a big yapper,” the appeal of discussion-based classes like Portico stretched beyond the course material. There he was encouraged, and even expected, to engage vocally with his new peers.

Said chose to blend his intellectual and spiritual growth when he added a theology major to his concentrations: finance, and accounting for finance and consulting. “A lot of what you’re doing

in theology is the same as what you do in business—you’re trying to find a precedent,” he says. “If I want to know something about a company, I will look back at their old financial statements. If I want to know something about the Book of Exodus, I’m going to look at the comments from theologians about Exodus.”

It was through his theology classes that Said came to better understand his own spirituality. After attending a Jesuit high school in Detroit, he was no stranger to Jesuit practices like the Examen, a daily reflection on one’s experiences, but classes including “Buddhism and Christianity in Dialogue” helped Said rethink prayer and reflection through mindfulness. “I view the world through my practice. I do my meditation and my examination of conscience and then pray,” he says. For Said, this routine applies as much to rehashing his performance on an exam as it will to his post-graduation role as an Air Force Tactical Air Control Party Officer. “I’ve had time to think about what this means for me,” he says about his next steps. “It’s daunting but I feel prepared.”

While some students find that their formation is intertwined with their religion, others with no religious affiliation still seek something that helps form them as whole persons. “Although not everyone belongs to a faith tradition, most, whether they know it or not, function in some sort of religious structure, ritual, or symbolic expression,” says Butler. “All of our students want to transcend themselves and experience things greater than who they are and where they came from.”

By virtue of being a Jesuit university, Boston College’s educational and spiritual influences loom large in the formative education picture, but the process would be incomplete without social elements. “We’re trying to inform and educate in the classroom, first and foremost,” says Sacco, “but we also give students experiences to help them grow socially with leadership, self-awareness, and social responsibility.”

Irfane Soumanou ’25, who studies finance as well as computer science, got involved with Boston College’s African diaspora dance group, Presenting Africa to U (PATU), as a way to meet more people on campus. “It was my stress reliever. In the studio, dancing was all I thought about. I wasn’t worried about my other preoccupations. I was having fun doing something I love with my chosen family,” she says, adding that she grew as a dancer and as a team player through PATU.

Namkoong cemented his commitment to social responsibility during his internship with Metro Housing Boston. As part of

AIDAN SAID ’24