beyond bars the

2 Beyond the bars: Looking through crime constructs

Introduction

3

9

15

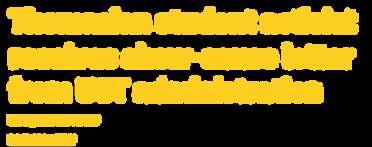

Criminalization of Resistance

AJ Dela Cruz

Not Right nor Wrong: Is It Acceptable?

Risven Dela Paz

Familial Foundations

Faith Qua

31

19

21

Krimen ng Estruktura

Phebe Jandayan

Territorial Stigma on Urban Crime in the Slums

Ian Jerome Noble

25 29

Inherited Gazes/ Paradox of Self-Policing

Andrei Fuerte

The fluidity of the law/ The shift of the way we see crime

Victor Soriano

Breaking the 4th Wall Conclusion

“The 'Enlightenment' , which discovered the liberties, also invented the disciplines. ”

- Michel Foucault

Our earliest reference of crime may have been legal law — the set of morally-based principles that define what is an acceptable societal behavior and what is not. We do not steal or kill others because it says so in our laws. But is crime solely determined by law, or is there more to it?

Throughout our lives, starting with our parents, we may have been socialized to see crime legalistically in black and white, but this is not as simple as it seems — the line between right and wrong is more fluid than we think it is. So, what influences this line between right and wrong, good and bad? In this zine, we argue that it is the things around us — the social structures governing our lives.

In this zine, we will also tackle the ways the structures of family, education, government, media, and economics influence how people construct the way they view crime. We will also look at how systemic biases formed by these structures might result in unequal perceptions of crime based on race, class, gender, and other social positions.

We, the creators of this zine, had the freedom to express our sociological explorations of crime in our own ways. The differences in design, language, and more are extensions of our unique social positions.

When I was six, my entire Ilocano family moved to Metro Manila due to the lack of opportunities in the province. My aunt, an economics graduate from a state university, was the first of us to traverse the urban jungle. Her first job in the city? A 7-11 cashier. She eventually landed a government job and climbed the bureaucratic ladder — a success story that taught her and by extension, the family, to respect the government and never turn our backs against it.

Then came the pandemic and all its issues that radicalized me into becoming a national democratic activist. I believed that genuine learning happens not inside the four corners of my laptop but outside in the streets with the masses. Instead of attending my synchronous classes, I joined mobilizations, organized other students and my neighborhood, and created propaganda materials.

Similar to the experience of other activists, when my family found out, they were furious like I committed a crime. And I did: I disobeyed the family rule to never bite the hand that fed us They told me that if the government knew that their relative was conducting “anti-government” activities, they would be terminated from their posts, threatening our only source of livelihood during a period of economic unpredictability.

A micro-level analysis of this reasoning made me realize that my family’s conception of crime was (1) coming from their positionality as migrants trying to keep their place in an environment they had to toil for years to reach, and (2) constructed by their knowledge of the state’s institutional capacity to exact retribution against dissenting citizens by framing them as criminals.

My family knew of activists being falsely tagged as terrorists, illegally imprisoned on fake charges, and worst, extrajudicially killed and they did not want such violent state-sponsored fates for me.

Aside from my positionality as a migrant and the institution of family, the construction of crime is facilitated by my positionality as a queer student and by the institution of religious education. My peers and I’s membership in mass organizations and our queer gender expression were violations of our Christian senior high school’s handbook.

The criminalization of long bleached hair, of gender-affirming lived names, of militant activism points to the latent function of meso-level environments like religious education to produce workers imbued with what Max Weber coined as the Protestant Ethic.

Weber argued that religious values such as hard work, discipline, and obedience reinforce the capitalist system by shaping individuals into compliant, self-regulating workers. The disruptive nature of creative selfexpression and organizing exists as a criminal threat to such system which relies, according to the ethic, on the moral imperatives of uniformity and individualism to turn its gears for eternity.

Some societal actors are challenging the exploitive gears of capitalism maintained by the intersecting institutions of the family, state, education, religion, and international organizations to a halt. But these actors are still tagged as criminals by different macro bodies.

For example, the New People’s Army, which seeks to replace the existing Philippine government with proletarian leadership and expel imperialist influence from the country, is tagged as a terrorist organization by the Office of the Philippine President, the European Union, the United States, and Japan.

Hamas, the militant Palestinian government combatting Israel’s profitable, United States-backed occupation of Palestine, is similarly designated as a terrorist organization by Australia, Canada, Israel, Japan, New Zealand, the United Kingdom, and the United States. Ironically, Israel’s genocide of Palestinians continues on without concrete accountability despite war crime rulings from macro bodies such as the United Nations, International Criminal Court, and International Court of Justice.

If macro resistances against capitalism are criminalized while profitable genocides are permitted, what is left of us students at the meso level, of families and individuals at the micro level?

Beyond our positionalities, we must recognize the role of intersecting hegemonic institutions in the construction of criminality and assert that since these institutions are socially constructed, they can be changed by the power of our agency as argued by Anthony Gidden’s structuration. I then forward Antonio Gramsci’s counterhegemony — the creation of alternative interactions, ideas, and institutions that undermine prevailing structures.

Coming from the ND tradition, I try my best to live a counterhegemonic life. As family and friend, I initiate digestible political discussions centered on issues close to my loved ones as stepping stones to more complex social ills and to debunking state narratives against activism’s purported criminality. As a student engaged in journalism and research, I immerse myself in communities to learn about their conditions and bring my knowledge from university back to them. I also use my discipline to reflexively formulate and advocate for an education system that does not criminalize resistance but is free in tuition, free in thought, and free to serve national needs, not corporate and foreign profit.

Finally, as a simple individual, I commit myself to criticism and self-criticism. While criticizing oppressive institutions with all the theories out there is important, we must never forget to remold ourselves into kind, humble individuals. We cannot clinch people to our cause to change macro institutions that criminalize our every move if, at the micro level, we are arrogant and antagonistic to prospective allies, if we coddle abuse and erroneous “due” processes within our ranks, if we live with problematic attitudes that cannot be masked — or even often justified — by name-dropping Marxist theorists.

In sum, our little symbolic interactions of unlearning entrenched notions of criminality in different levels of society can pave the way for better institutions that will hopefully usher in a more progressive world.

Not Right nor Wrong: Is It Acceptable?

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:My_body_my_choice_sign_at_a_Stop_Abortion_Bans_Rally_in_St_Paul,_Minnesota_(47113308954).jpg

for us to experience the same thing?

FAITH QUA

The family is considered as the basic unit of society. All of us are born into one and many of us grow into multiple stages of our lives alongside them. At the same time, in the Philippine context, we must prioritize and place the family at the center. Therefore, the family holds a lot of influence over how we construct the idea od crime. Firstly, the familial structure imposes the idea of crime through positive and negative reinforcement. From childhood, the concept of punishment vs rewards has been introduced. We are punished for actions our parents deem as wrong or deviant to their orders while complying will grant us rewards and praises. This becomes ingrained in our minds and acts as a foundation in gauging whether an action is one to be emulated or renounced. As we grow older, we learn to apply such teachings ourselves in discerning whether an act is a crime (whether petty or heinous) or not through our interactions with society and social media.

As we engage in various interactions with others, we expose ourselves to varying perspectives on what is considered shameful or wrong and the opposite. Additionally, from these interactions, we also get to form specific standards of a model person or citizen, which is shaped by multiple subjectivities. We can then identify patterns within these standards and stand by them. For example, to be a model citizen, we can perceive it as being law-abiding because that is what is generally said around us. However, instead of finding patterns, we may also choose to pick apart those we perceive as more significant to us. Instead of law-abiding, we may perceive a model citizen as someone who embraces the nation through direct action like buying local products and updating oneself with local news. Being lawabiding still makes a model citizen, but we choose to place more emphasis on traits we deem to align closer with our values.

At the same time, social media also plays an integral role in shaping this distinction. If we come across a criminal case online (or even smaller anecdotes from netizens), we have the opportunity to gauge the distinction between right and wrong from the general reactions of netizens. A simple click of the “quote tweets” on X and even just taking a glance at the reactions tab on the bottom left of a Facebook post provides enough information on the general consensus of different matters. Therefore, with the foundational ideas from our family, actions that yield to negative engagement are associated with crime or an action we should not do to avoid facing the same outcome. At the same time, actions that garner positive reactions (like compliments, and physical rewards) are those we find ourselves trying to replicate or find ourselves praising in others as well.

With interactions we encounter in our daily lives and the digital sphere, we then tend to perceive crime as actions that lead to negative reactions (hateful comments, punishments) and/or challenge our idea of a d l iti /

HE WHO DOES NOT PREVENT A CRIME WHEN HE CAN, ENCOURAGES IT

Next, even families outside of our own have the power to construct the way we view crime. Political families or simply families with power and influence have resources at their disposal that further blur the lines of what action is considered a crime. With their power and status in society (even being a president in the Marcoses’ case), we witness many actions we consider crimes (with our foundational ideas previously stated) going unpunished and suspects being exonerated for such actions. This includes taking the country’s funds, torture, taking away people’s freedom of speech, killings, and more under the Marcos rule. This starts an introspection within ourselves on such erasure of crimes. On one hand, some may start to identify the act as not a crime instead and may even try to replicate it due to the lenient aftermath and the lack of stakes. On the other hand, those who still consider it a crime understand that it is not solely the legal system that can make this distinction but there are also moral grounds at play.

This was true in my case. I found myself questioning how such actions I considered as crimes, which were even done in a very public and blatant manner are almost absolved (in the present) as the Marcos family were able to gain political power once more. At the same time, many continue to suffer under the aftereffects of martial law whether it is from the death of a loved one or from the torture they experienced themselves, and yet, receive little to no justice. I realized that people’s moral stances take up more of a forefront role in not only what constitutes a crime but also how they deal with it afterward.

With that, the influence of the familial structure on our perception on crime may stem from our own families, but it may also come from external families who possess status and power in our society.

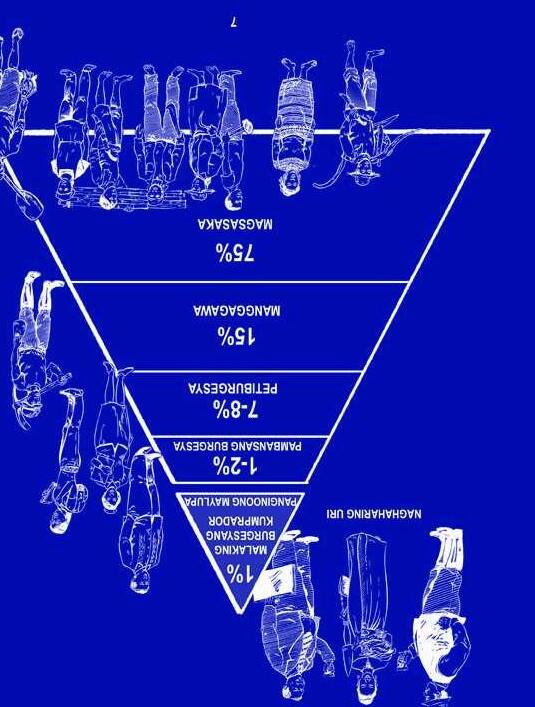

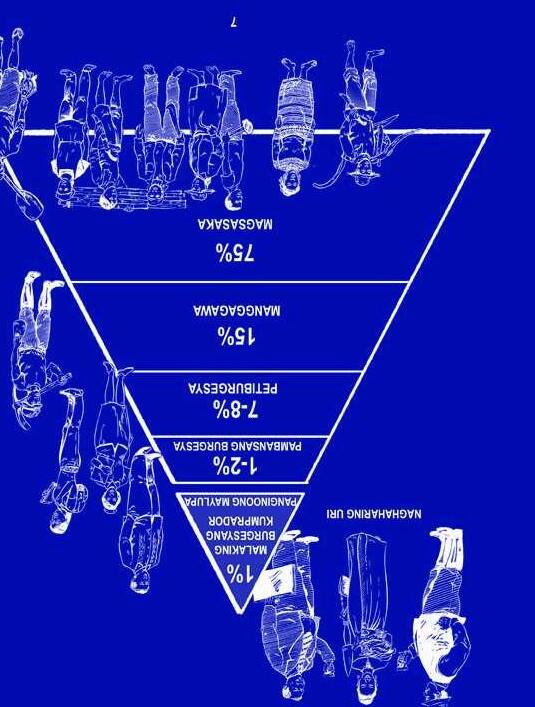

Phebe Jandayan

Ang mga gawain ay madalas na itinuturing na krimen batay sa mga batas na nilikha ng pamahalaan (istruktura ng lipunan), at ang mga batas na ito ay kadalasang nakaugat sa pangangailangang maiwasan ang mga paglabag sa karapatang pantao, at sa proteksyon ng buhay, ari-arian, at seguridad na nakatuon sa kaayusan ng lipunan na ideya ng teoryang Structural Functionalism. Ngunit hindi ito ang sistema sa lahat ng pagkakataon sapagkat kung minsan hindi ito lubos na kumakatawan sa pangangailangan at karapatan ng lahat na sektor kundi ng mayaman at makapangyarihan lamang. Ginagamit din ng ilang tagapamahala ng pamahalaan ang Sosyal na Kontrol at Dinamika ng Kapangyarihan (Social Control and Power Dynamics) upang gawin ang pansariling interes, kontrolin ang mga marginalisado sa lipunan, at tuwirang proteksyunan ang kanilang sarili sa kabila ng pang-aabuso na ginagawa nila sa mga nasa laylayan. Gayunpaman, ang paraan ng paglilingkod ng mga batas na ito sa mga indibidwal ay maaaring magkaiba-iba nang malaki batay sa kanilang katayuan sa lipunan at ekonomiya.

Bilang isang mamamayang naninirahan sa komunidad na nakatatamasa ng katamtamang kahirapan kung saan nakakamit ang mga pangunahing pangangailangan ngunit sa mahirap na paraan, at nakatuntong sa lipunang talamak ang korapsyon. Hindi maitatanggi ang krimen na karaniwang kinasasangkutan ng mahihirap tulad ng pagnanakaw, illegal na kalakalan ng droga, at illegal settling dahilan ng kakulangan sa pangangailangan at oportunidad . Tunay na mananatili itong krimen sa harap ng batas at ng lipunan anuman ang dahilan kung kaya may agarang pananagutan, mabuti man ang pangunahing dahilan at hangarin nito. Subalit, ang kalagayang kinakaharap ng mahihirap ay nakasandig sa krimeng ginagawa ng makapangyarihan at mga estruktura tulad ng patakaran sa ekomiya, at sistema ng hustisya na nagdudulot ng paghihirap, kawalang-katarungan, at hindi pagkakapantay-pantay sa mga nasa laylayan. Dahil patuloy nitong ipinagkakait sa mga tao ang kanilang mga pangunahing karapatang pantao, naniniwala ako na ang structural violence—gaya ng kawalan ng access sa serbisyong pangkalusugan, edukasyon, disenteng tirahan, at makatarungang trabaho ay dapat ituring na uri ng krimen. Isa lamang sa pangunahing dahilan nito ang talamak na korapsyon sa lokal na pamahalaan na sa kasalukuyan ay tinatanggap na lamang ng mga mamamayan bilang isang normal na gawain sa kabila ng lubusang kaapektuhan nito sa kanila. At dahil sa kapangyarihan at kayamanan, ang krimen na ginagawa ng mga nasa posisyon na gumagawa at nagimplementa ng batas ay madalas na isinasawalang bahala at pinapalipas na lamang dahilan ng kanilang Sosyal na Kontrol at Dinamika ng Kapangyarihan (Social Control at Power Dynamics).

Bilang karagdagan, ang posisyon sa lipunan, partikular ang socio-economic status ng isang indibidwal, ay may malaking epekto sa kanilang pananaw tungkol sa krimen at kung paano sila pinoprotektahan ng batas panlipunan. Halimbawa, ang mga marginalisado na grupo ay itinuturing na mga krimen ang mga kawalan ng katarungan at hindi pagkakapantay-pantay sa lipunan, tulad ng diskriminasyon, kakulangan ng access sa serbisyong pangkalusugan at edukasyon, bilang anyo ng structural violence.

Sa kabilang banda, ang ilang mayaman at makapangyarihan at lalo na ng mga kapitalistang indibidwal ay itinuturing na krimen ang pagkawala ng ari-arian ngunit hindi nila isinasama ang kontraktwalisasyon, pang-aagaw ng lupa, at mga hindi pagkakapantay-pantay sa lipunan laban sa mga marginalisadong grupo bilang krimen, basta't ito'y pakibang sa kanila.

TULA SA MAGSASAKA

Isa lamang ang magsasaka sa mga marginalisado

Na inaapi ng mga kapitalistang may yaman at ari-arian

Madalas ang mga polisiyang ginagawa’t isinasabatas

Ay angkop lamang sa may pera’t kapangyarihan

Ninanakawan ng lupa, dekada ng sinasakahan

Kapag di sinang-ayunan, karahasan, Militarisasyon at diskriminasyon ang tugon

Mula sa pamilyang komersyalisasyon ang layon

Sila ba'y bulag sa krimeng ginagawa nila?

Ngunit kapag pera’t ari-arian, sa kanila’y nawala

Huntisya’y agad nakaantabay

Tila polisiya’y naka-alalay

Kailan mabibigyang pansin ang diskriminasyon, Sosyal na pagkiling, at kawalang katarungan

Krimen sa mahihirap, ngunit yaman at halakhak

Sa mayamang gaya ng Cojuanco, Araneta, at Villar

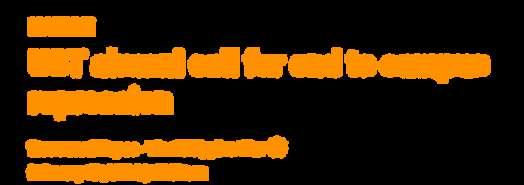

Ian Jerome Noble Ian Jerome Noble

Lumaki ako sa isang slum residence kung saan maingay at magulo ang karamihan ng mga tao. Sa murang edad pa lamang ay nakasanayan ko na ang ganitong kultura ng maingay na kapaligiran at bahagyang marumi at magulo’t dikit-dikit ang mga bahay. Normal ang mamuhay sa ganitong komunidad para sa akin. Subalit pagpasok ko ng elementarya, namulat ako sa pananaw ng ibang tao na nagsasabing may mataas na ingklinasyon na gumawa ng mga ilegal at masasamang gawain ang mga tao sa aming lugar. Nagmistulang culture shock ang pananaw na ito matapos na sabihin ito ng aking kaklase nang ikuwento ko kung saan ako nakatira.

Labis ang pagtataka ko dahil hindi naman ganito ang kinalakihan kong kultura. Kahit pa magulo ang komunidad namin, hindi naman kami humahantong sa paggawa ng krimen dahil lang mahirap kami. Sadyang kumakayod ang mga tao sa amin para itaguyod ang pang-araw-araw ngunit kalimitan ay hindi naman ito humahantong sa paggawa ng ilegal na gawain. Pero kahit na ganoon, napatanong na lang ako: bakit may ganitong pananaw ng kriminalidad na iniuugnay sa mga mahihirap at mga nakatira sa slums o mas tinatawag na ‘iskuwater’?

Mula sa ideya na ang standard na mamamayan ay dapat edukado at may delicadeza, iginuguhit nito na ang mga taong mahihirap sa “iskuwater”— maaaring tumutukoy sa lugar o sa taong nakatira dito—ay mas may tendensya na gumawa ng krimen. May ibang nagdadahilan na dahil nga sa pagiging salat at sa kahirapang nararanasan ay nagagawa nilang gumawa ng krimen, o mayroong ibang pananaw na nasa kultura na sa iskuwater ang paggawa ng ilegal na gawain.

Nagbubunga ito ng “territorial” stigma sa mga residente ng iskuwater—ang mga mahihirap ay itinuturing bilang mga walang delicadeza at mga kriminal. Dito makikita kung bakit laganap ang pagtanaw ng diskriminasyon sa mga iskuwater, kung saan idinidiin ang negatibong pananaw ng kriminalidad sa kanilang social position. Dahil sa hindi pagkakapantaypantay sa access sa kapangyarihan, edukasyon, at oportunidad sa lipunan, nagkakaroon ng pagbubukod batay sa kanilang posisyong pangekonomiko. Bunga nito, negatibo ang pagtingin ng mga taong nasa mas mataas na panlipunang uri (class) sa mga mahihirap dahil tinitingnan sila bilang may mababang katayuan sa lipunan.

Ang batas ang nagdidikta kung ano ang tama o mali na gawi ng mga mamamayan sa isang bansa. Ito ang nagsisilbing written codes na nagpapanatili ng kaayusan sa lipunan at pinapangalagaan nito ang ating mga karapatan. Pero bakit tila may kinikilingan ang batas sa Pilipinas?

Ang kamakailan lang na War on Drugs ng administrasyong Duterte ay kakikitaan ng ganitong pagmamanipula ng batas. Sa kampanyang ito laban sa pag-abuso sa droga, ang mga tinutugis ng gobyerno ay kalimitang mga mahihirap. Nagsilbing batas ang salita ni dating pangulong Duterte laban sa pagpatay ng mga drug offenders nang walang paglilitis. Sinang-ayunan naman ng ibang mga tao ang sentimyento ng pagpatay sa kanila. Sa pamamagitan din ng media, mas pinagtibay pa nito ang pananaw na ang mga iskuwater ay pinagpupugaran ng mga kriminal.

Mula rito, mahihinuha na ang batas ay nagkakaroon ng sariling interpretasyon na nakaangkla sa mga institusyon ng pamahalaan, depende sa impluwensya ng kung sino ang may kapangyarihan at awtoridad. Sa kaso ng War on Drugs, si Duterte, ang institusyon ng kapulisan, at ang impluwensya ng media, ang ilan sa nagdikta na kailangang puksain ang mga kriminal na drug offenders para sa ikabubuti ng lipunan. Ito ay pagsasaalang-alang sa seguridad ng buhay ng mga mas nakaaangat sa buhay na tinatanaw bilang maaaring maging biktima ng mga kriminal sa iskuwater. Pinapatunayan lamang nito na ang batas ay nababaluktot ng mga nangingibabaw na institusyong panlipunan at mga makapangyarihan.

Dagdag pa rito, hindi maipagkakailang mayroong kawalan ng katarungan sa pagdidikta ng krimen pagdating sa mga mahihirap. Masasabing mayroong “ poor criminal justice system” sa Pilipinas. Mula sa terminolohiyang pa lang na ito, makikita nang tila may bahid na agad ng kasamaan at pagiging marumi ang pagkakaintindi sa salitang “poor.” Kumbaga nabuo na sa pananaw ng mga tao na ang terminong poor at mga tao o bagay na may kaugnayan dito ay may masamang konotasyon.

Ang “poor criminal justice system” sa Pilipinas ay naipapahayag sa mga kaso ng kriminalidad kung saan kalimitan ay walang takas ang mga mahihirap sa kamay ng batas, habang ang mga may mas kakayahan sa buhay ay kayang sustentuhan ang mahabang proseso ng paglilitis at pag-piyansa. Ito ay sa pamamagitan ng pagkakaroon ng mga middle class at elites ng resources at connections. Sa kabilang banda, ang mga mahihirap naman ang mas nagdurusa dahil sa kawalan nila ng sapat na resources upang maitawid ang kanilang mga kaso at makamit ang hustisya.

Dahil dito, masasabi ko na ang posisyon natin sa lipunan (race, etnisidad, kasarian, katayuang sosyoekonomiko, citizenship) ay mahalagang bahagi sa pagbuo ng identidad natin pagdating sa pagpapasya sa kriminalidad. Nagkakaroon ng hindi pantay na pagtingin ang mga institusyong panlipunan sa karapatan ng mga tao dahil sa hirarkikal nating posisyong panlipunan at katayuang sosyoekonomiko. Bunga nito, madalas na ang mga naaapi at marginalized na grupo o sektor sa lipunan ang nagiging biktima ng hindi pantay na pagturing sa kriminalidad—ito ay anti-poor. Kaya ang mga nangingibabaw na institusyong panlipunan ang nagmamando kung saan kumikiling ang dikta sa moralidad ng batas.

With the constant presence of multiple structures in each of our lives, there is no denying that they are capable of framing our views on crime. However, our agencies give us the power to confront structural influences alongside our own principles. It is this interplay of structures and agency that paves the way for the nuances and complexities of society.

Assessing societal complexities then demands the need to acknowledge that every person comes from different social positions that diversify their perspective and experience of society and its issues like crime. Hence, even if we all grew up in the Philippines, our varied social positions resulted in equally varied sociological explorations of crime.

Thankfully, our subjectivities enabled our introspections to venture into different structural institutions we deem more influential in our own lives. Such multiplicity helped us to break the fourth wall — the smoke screen that had long blurred and limited our understanding of crime — and come to the conclusion that crime is not black and white.