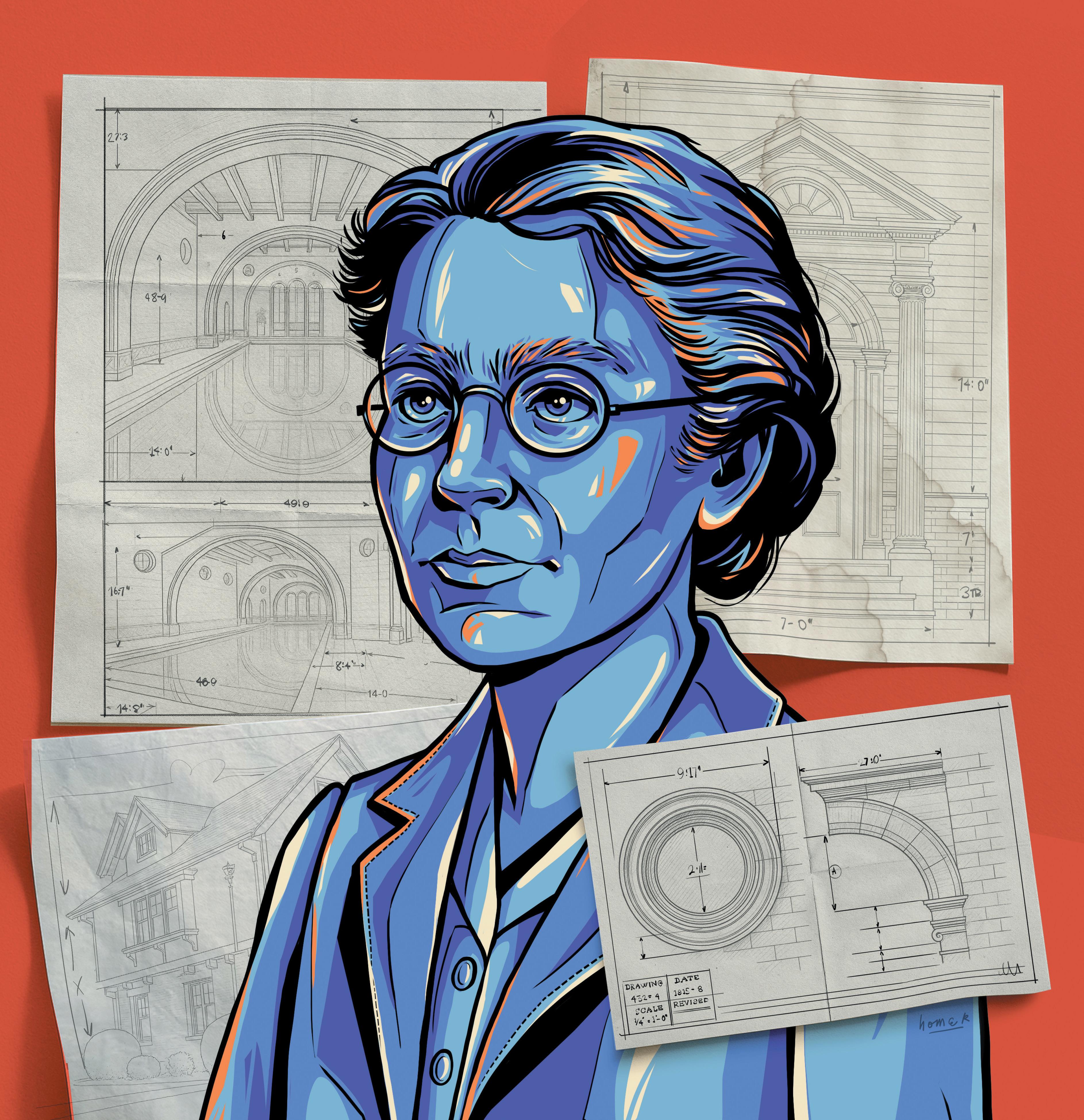

How the history and ideals of the Bay Area laid the groundwork for its diverse and innovative architectural styles

STORY BY MARTHA ROSS ILLUSTRATION BY PEP BOATELLA

Ifyou had to name a quintessential Bay Area style of building, you might go with an elegant Victorian or a cute Arts and Crafts bungalow. You might pick something from the past, such as Mission Santa Clara, or something modern, with lots of wood and glass, set amid redwoods or along the waterfront.

Those architectural styles may seem wildly different, but they are all an integral part of the landscape. If you want to understand the origins and diversity of the Bay Area’s architecture, historians say you have to first consider that it developed in response to the region’s natural beauty and mild, Mediterranean climate, which allows people to be outdoors year-round.

But other factors have influenced architecture here. From the Gold Rush through World War II and into the 21st century, the region has been a magnet for people streaming in from other parts of the United States and around the world.

Seeking a better life, these migrants helped create a worldclass metropolitan region of 7.3 million people that has long been known for its diverse communities and its corresponding variety in architectural styles, from traditional to modern to international.

What’s less considered — but equally important — in the Bay Area’s architectural history is its location on the western edge of the continental U.S., according to architects, authors and historians Alan Hess and Mitchell Schwarzer.

For millennia, the Ohlone and Coast Miwok inhabitants pretty much had the place to themselves. They built conical-shaped homes out of tule reeds and other local materials, but spent most of their time outdoors, hunting and gathering food in accordance with the seasons. It could be said that these indigenous people pioneered the concept of California indoor-outdoor living.

Until the Gold Rush and the opening of the transcontinental railroad in 1869, the surrounding mountains, deserts and oceans kept the Bay Area and the rest of California pretty much isolated from world centers of power and culture. California’s early colonizers, starting with the Spanish in the late 1700s, found it could take months to get here, traveling by wagon over the Oregon trail or sailing down and around Cape Horn.

“It was much easier to get from Europe to Chile than to California,” said Schwarzer,

author of “Architecture of the San Francisco Bay Area: A History and Guide.”

The people who made it to the Bay Area therefore had to be pretty adventurous and motivated by a fierce desire “to start a new life, forget the past and to live the life the way they wanted.

They had the freedom to do that in the Bay Area,” said Hess, the former architecture critic for Bay Area News Group.

For architects, this freedom meant that “no one’s looking over your shoulder,” Hess said.

“The many talented architects, who were either born here or immigrated here from the East Coast or the Midwest or Europe, they came here because of that freedom to really do something new and different.”

There also was a blank-slate quality to the Bay Area, which fostered experimentation and variety. Architects could import familiar styles from the East

Coast, Europe or Asia, then modify them to fit the local landscape or changing times. Likewise, new residents could choose the kind of home they would live in. “If they wanted a castle, they could build a castle,” Hess said. “If they wanted a rustic cabin in the forest, they could do that as well.”

Isolation, of course, is no longer an issue for the Bay Area. But pressures on the population and on the natural environment have pushed the region’s architecture in new directions, including a focus on creating new forms of multi-family housing to address the region’s dearth of affordable housing, Schwarzer said. After the COVID-19 pandemic emptied office towers in San Jose, San Francisco and Oakland, architects and urban planners also are having to rethink how they envision workplaces.

Meanwhile, engagement with the landscape remains the Bay Area’s “calling card,” Schwarzer said. But this landscape is affected by climate change, and earthquakes and wildfires remain a threat, leading to modes of residential and commercial construction that are environmentally sustainable and can survive calamities.

Still, Schwarzer and Hess are optimistic about the future. “Surely,

the beauty and dynamism of our natural environment encourages architects to strive for something similarly magnificent in the built environment,” Schwarzer wrote in his book, while Hess said: “Architects have a sense of continuing tradition that they can bring into current times, but it’s rooted in something solid.”

Here’s an overview of the eras and styles that have shaped the Bay Area landscape:

The traditional architectural practices that Spanish missionaries brought from Southern Europe were easily adaptable to the Bay Area landscape. The abundance of clay, straw and other materials could be turned into adobe, used to build their missions, presidios, pueblos and ranchos. The 21 California missions, from San Diego to Sonoma, still offer the best examples of the classic Spanish style. Because they needed to attract attention as religious centers, they incorporated many of the embellishments appreciated today — whitewashed walls and red-tile roofs, bell towers and courtyards graced by fountains.

After gold was discovered in the Sierra foothills, California’s isolation ended. From 1847 to 1865, San Francisco’s population soared from 450 to more than 100,000, hastening its integration into the American and world economies, according to Schwarzer. The booming economy, which continued past the Civil War, created a new class of millionaires who wanted to flaunt their wealth. Some looked to the classical styles preferred by European royalty or Gilded Age barons for ideas on how to build grand mansions.

Everyday architecture in the late 1800s also “turned up the decorative heat” to bring on a proliferation of richly ornamented homes, with decorative columns, molding and other embellishments made possible by the availability of redwood, Schwarzer said. The Victorian era culminated with the storybook Queen Anne style, with dramatic corner towers, witches’ hat turrets and ornate porches, followed by the more streamlined aesthetic of Edwardian homes.

The approach of the 20th century ushered in a taste for reviving all kinds of classic styles in the Bay Area, such as Tudor, Georgian, Colonial and Mission, the latter best represented by Leland Stanford’s grand scheme to build a prestigious

new college in Palo Alto. Bay Area leaders, meanwhile, looked to bring “City Beautiful” concepts for their cities, especially following the 1906 earthquake. The style thought to best convey this grandeur was Beaux-Arts, which draws on the principles of French neoclassicism and incorporates Italian Renaissance and Baroque elements. Architect Willis Polk helped develop a plan for San Francisco’s Civic Center, which included the 1915 Beaux-Arts City Hall, while other notable Beaux-Arts buildings include Bernard Maybeck’s Palace of Fine Arts and John Galen Howard’s Doe Library, Hearst Memorial Mining Building and the Greek Theatre on the UC Berkeley campus.

Perhaps as a reaction to Beaux-Arts haughtiness, Polk, Maybeck and Julia Morgan also worked in the First

Bay tradition, which shares similarities with the English Arts and Crafts’ emphasis on rusticity, simplicity and fidelity to natural materials. In the Bay Area, redwood also became the go-to material for the shinglesided First Bay homes, churches and community centers that Maybeck and Morgan designed. Arts and Crafts also became the original style associated with Bay Area bungalows, those affordable, solid, working-class homes that became an icon of residential urban and suburban neighborhoods, starting in the early 1900s, wrote UC Berkeley geographer Richard Walker and urban planner Alex Schafran.

During the 1920s and 1930s, many prominent Bay Area builders chose Art Deco to celebrate the region’s growing

economic and industrial power. Originating in Paris and flourishing in Europe and the United States, the style represented a belief in social and technological progress. Art Deco also became a preferred style for glamorous Bay Area entertainment venues, some of which still operate today as movie theaters or concert halls.

By the 1950s, up-and-coming 20th-century Bay Area architects embraced the futuristic design philosophies championed by the Bauhaus and International Schools, which “cast off the conventions of the past,” Schwarzer wrote. Well-known Bay Area monuments of modernism include Frank Lloyd Wright’s Marin County Civic Center, the former San Jose City Hall and the Oakland Museum of

California, the latter built with concrete and the bold, geometric forms of Brutalism. Even before the turn of the century, the urban centers of San Jose, Oakland and San Francisco had begun to go vertical with the use of steelreinforced concrete, though early skyscrapers tended to look to the past with Beaux-Arts, Romanesque or Gothic exteriors. Following World War II, office towers, with modernist-style glass curtain walls, began to rise, such as the 28-story Kaiser Building in Oakland.

One of the leading Bay Area practitioners of modernism was Wiliam Wurster, the dean of UC Berkeley’s School of Architecture, who applied its principles to a signature kind of

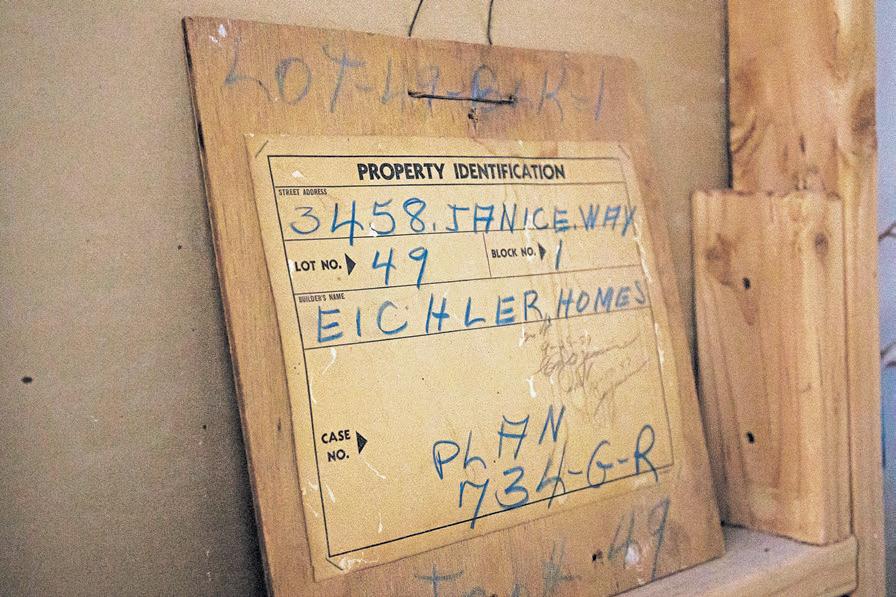

California construction — the suburban ranch house. Wurster’s usually small homes featured flowing interiors that opened up to the outdoors. To address the post-World War II population boom, Wurster also helped build innovative, affordable, massproduced homes, similar to the efforts of developer Joseph Eichler, another modernist fanatic who built thousands of homes in new suburban tracts across the Bay Area.

The ranch house proved to be highly adaptable to a variety of settings and styles, with the Bay Area flatlands and hillside neighborhoods filled with rows of modernist split-levels or homes that emulated more traditional looks, from Cape Cod to Tudor Revival to the neo-Tuscan style that became “the rage” in the 1980s, with increasingly bloated footprints, according to Walker and Schafran.

Even as historic preservationists strive to hold on to the character of Victorians, Art Deco movie theaters and Eichler neighborhoods, civic leaders, developers, tech billionaires and architects have been pushing design forward. Apple opened its $5 billion “spaceship” headquarters in Cupertino, while sleek, environmentally sustainable, ultramodern designs such as San Jose City Hall and the new M.H. de Young Museum have become de rigueur for any new government, corporate or cultural building that aspires to world-class status.

BY LUIS MELECIO-ZAMBRANO

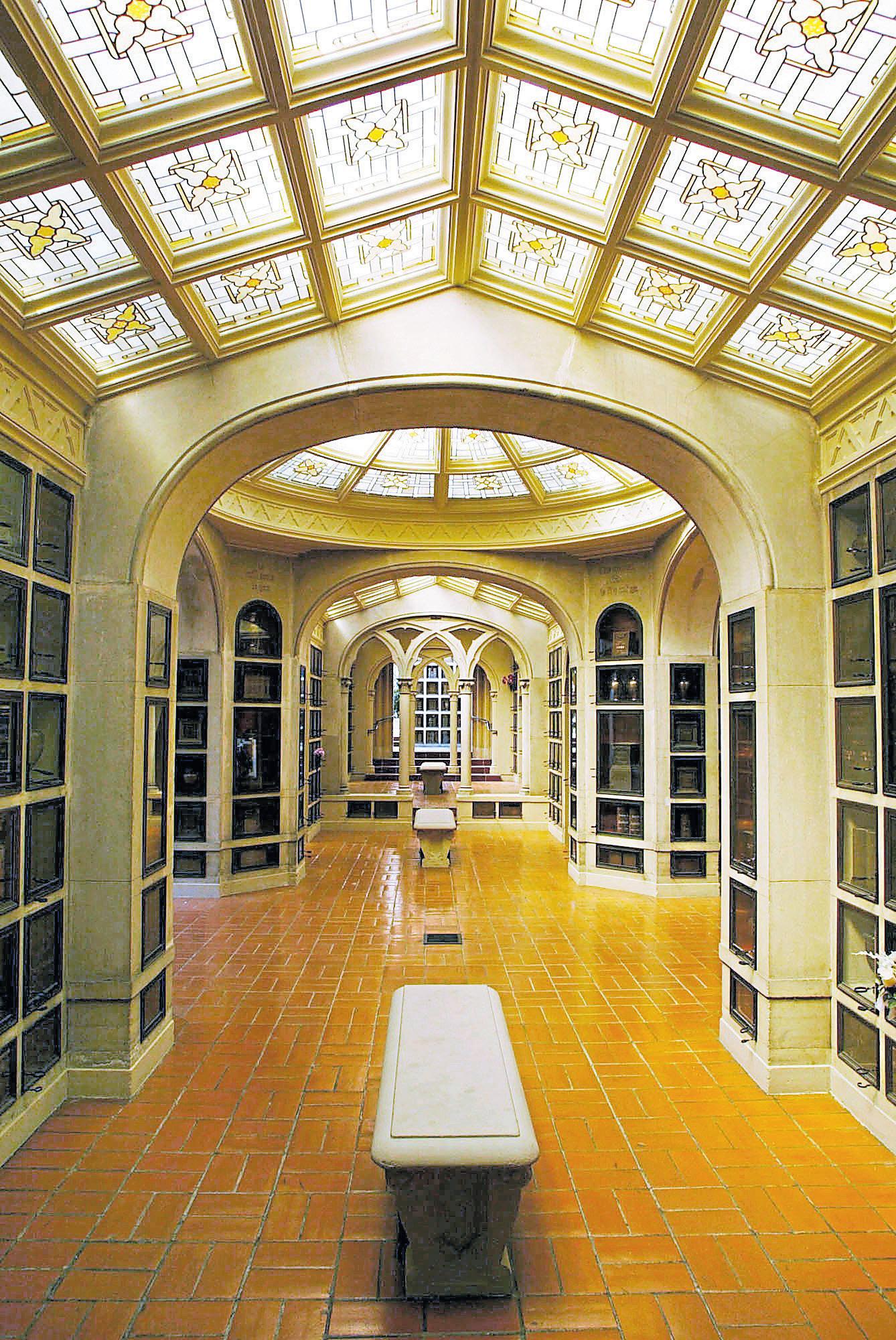

On a warm April Friday, gaggles of children gather between stark white columns painted with bright blue markings reminiscent of petals, listening in as a tour guide distills the core tenets of ancient Egyptian philosophy. Stepping through the gilded doors reveals scores of children who generate a buzz as they explore a replica of a plundered tomb and gaze into the unblinking eyes of a mummified Apis bull.

Behind the group tours that crowd around the glass-encased curiosities, a video softly plays on loop in the back of the museum. With piano music playing in the background, it displays the text of 22 precepts, superimposed over stock footage of diverse people and stunning vistas. Some precepts are unassuming — practice tolerance, be generous towards those in need, regard humanity as a family. Others, however, catch the eye — create a sanctum in your home;

before you eat; purify your food using vibrations from your hands; when taking an oath, think of the Rose Cross.

The Rosicrucian Egyptian Museum has long been a staple of San Jose culture, boasting 100,000 visitors each year — 26,000 of whom are schoolchildren. They come to glimpse pieces of ancient history; with more than 4,000 artifacts, the museum houses the largest collection of ancient Egyptian artifacts in western North America.

But few visitors know much, if anything, about the story behind its name or the century-old group known as the Ancient Mystical Order of Rosae Crucis, or AMORC, which created it.

The Rosicrucians are an offshoot of a Renaissance mystical tradition which traces its spiritual heritage to ancient Egyptian pharaohs and philosophers from Greece, India and what they call “the Arab world.” Their blend of research and mysticism infuses

the museum and the grounds that surround it with a certain spiritual mystique that may go unnoticed by visitors.

“Everything that we manifest at Rosicrucian Park is with the mystical perspective in mind,” says Julie Scott, director of the museum and a Grand Master in the order.

The Rosicrucians believe that they have esoteric wisdom passed down for millennia and that members gain access to much of this wisdom through tiered lessons and initiation.

AMORC traces its roots to ancient Egyptian mystery schools that learned hidden wisdom and engaged in mysti-

cal studies. In AMORC’s telling, this ancient wisdom found a throughline through Greek philosophers like Pythagoras to medieval philosophers and alchemists, until being chased into hiding for centuries.

In the early 1600s, though, a series of texts attributed to a German theologian introduced the Rosicrucian order, and the ideas of alchemy, mysticism and the connection to ancient wisdom influenced a panoply of thinkers and esoteric movements throughout Europe and, eventually, the world.

AMORC, the San Jose organization that runs the Rosicrucian Egyptian Museum, became argu-

ably the most successful offshoot of Rosicrucianism.

The organization was founded in 1915 in New York by H. Spencer Lewis, and in 1927, he moved its headquarters to San Jose. He wrote extensively on esoteric issues and created a model of mail-order lessons for the tiered levels of study and initiation of the order, which helped spread its membership to tens of thousands across the globe.

While the ancient Egyptian origins of Rosicrucianism are considered mythical by scholars, according to Massimo Introvigne, managing director of the Center for the Studies on New Religions, the impact has been

real. “(The myth) is not simply a ‘false’ story, it is more a symbolic one,” says Introvigne. “Driven by their passion for Egypt, some Rosicrucians made worthy contributions in money and other resources to the knowledge of ancient Egypt.”

Lewis and the Rosicrucians backed excavations in Egypt, and — inspired by an artifact he kept on his desk in the ’20s — he decided to create a museum that “shared the spiritual beliefs of the ancient Egyptians,” said Scott. He began building a collection that became the Egyptian Oriental Museum. His son grew the museum, until the current building — modeled after the temple of Amon at Karnak — was built, and the Rosicrucian Egyptian Museum opened in 1966.

In the 60 years since, the museum has become a field trip staple for San Jose schoolchildren and a frequent collaborator with researchers and other museums throughout the Bay Area.

While such an outward-facing

endeavor might seem strange for a semi-secret society, it aligns with a theme of unusual openness for the order. AMORC members’ focus on improvement of their community went beyond the journey to self-improvement that some of their esoteric contemporaries had, according to Kevin McLaren, who wrote a thesis on esoteric movements and Egyptology.

AMORC’s teachings exhort its members to help those most in need and care for the environment. The organization has made its museum carbon neutral and has a public garden full of native and drought resistant plants, and its upcoming alchemy museum — slated to open on the 2026 spring equinox — is meant to meet the highest international standards for sustainable buildings.

Their mystical beliefs also influence how they view Egyptology. While mainstream academic thinking holds that the Pyramids of Giza were tombs, Rosicrucian tradition believes that the pyramids “were actually

places of study and mystical initiation.” Their website’s entry on the matter leaves the door open for interpretation: mentioning the mainstream understanding of the pyramids, but ending the entry saying “more information is being discovered and understood about their mystical purpose.”

“It’s presenting a perspective that doesn’t have the limits of academia,” says Scott.

Several experts in Egyptology, museums and Rosicrucianism admitted this approach might lead to some discrepancies with mainstream views or curation decisions that are unorthodox. They also argue that those may not be that important.

“Will I admit that I take some of their claims with a grain of salt? Yes, I 100 percent do,” said McLaren. “Do I think they include a lot of academic information at the same time? I think for the most part, they do a pretty good job. It’s both.”

Renee Dreyfus has been a curator of ancient art at the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco for nearly 50 years. While she doesn’t agree with all of the curation decisions that the Rosicrucian Museum makes, she has special praise for the museum’s outreach to children — especially since it was her own glimpse at the Egyptian collection at the Brooklyn Museum at age 3 that kicked off a lifelong passion.

“These kids are excited to be there. They’re open to listening and learning and looking — I mean, that’s wonderful,” said Dreyfus.

Back inside the museum, a girl — just a bit older than Dreyfus when she first encountered the relics of ancient Egypt — cranes to gaze at the sunken, leathery features of a mummy. She gasps, eyes wide with wonder as she says to her parents, “Look — it’s real.”

OK, there are no ghosts.

But here’s why it’s crucial to preserving San Jose’s architectural past

Forget ghosts. Forget séances. Forget mazelike passageways constructed to confuse vengeful spirits. The real mystery of the Winchester Mystery House is how it’s such a fascinating study in contradictions. Though we all grew up with the supernatural legends surrounding the San Jose house, they’re simply not true. As definitively explained in South Bay author Mary Jo Ignoffo’s 2012 book “Captive of the Labyrinth,” the mansion’s namesake, Sarah L. Winchester, never gave any indication in her lifetime that she was haunted by ghosts, let alone angry ones who had been killed by the rifles that her family produced. She probably never held a séance or had any interest in spiritualism at all. Pretty much all of the spooky mythology around her started to spread around 1895, according to Ignoffo — long after she had moved to the Santa Clara Valley from New Haven, Connecticut, and begun transforming a simple two-story, eight-room farmhouse into a never-ending construction project in 1886 — and intensified after her death in 1922. First spread by distrust-

ful locals and the San Jose newspapers (seriously, our bad), the stories were meant to paint the independent and extremely reclusive Winchester as an outsider and a freak — and later, as a means of promoting the house as a tourist attraction.

So, pretty terrible, right? Except … well, if it weren’t for those stories, there is almost zero chance that the Winchester Mystery House would still be standing a century later, allowing us to still visit this unique piece of San Jose’s past. Fake history has allowed for the preservation of real history — and considering how thoughtlessly the Santa Clara Valley’s rich heritage has been erased over the last several decades, we need all the history we can get.

There’s another paradox that’s perhaps even

more striking: Despite the focus on the house’s wild idiosyncrasies over the last hundred years, what might be most important about it now as a piece of South Bay architectural history are the ways that it wasn’t different from other homes that were being built in San Jose at the time. Those elements allow us a rare, gorgeously preserved window into what homeowners in the late 1800s were building in this area.

Because, to be honest, Sarah Winchester was a bit of a trend chaser, and the styles of the time that she went out of her way to procure tell us a lot about architecture in San Jose a century ago.

“It became a pretty classic Queen Anne Victorian,” says Winchester Mystery House’s official historian Janan Boehme, noting that it falls within

the American definition of the architectural style, not the British one. “Because it had, you know, the big, broad wraparound porch, the asymmetrical front — quite asymmetrical. It’s got the different textures on the different floors. It has the turrets and towers, all the finials, all the standard stuff that you have on a Queen Anne Victorian in this country. When it was at its full height and its full beauty, it was pretty elaborate.”

This was before the San Francisco earthquake of 1906, which did a huge amount of damage to the house. Winchester’s mansion had seven stories by that time, and she was eating up the large balcony spaces she had originally designed, filling them in with new rooms and fancier woodwork.

“As she was making changes, she would make

them much more elaborate,” Boehme says in an interview.

A lot of that was lost in the quake, as the building was mostly reduced to four floors, though some remnants of the others remained. While you may have marveled at the stairs and doors that lead to nothing —and they are very cool — almost all of them are a result of earthquake damage, rather than eerie design. An exception to this is the famous “Door to Nowhere” near the front of the house, which was added after the earthquake and is thought to be a rather innovative solution for loading and unloading supplies to the upper floors.

The house’s most devoted fans, however, know there is still plenty of beauty to take in throughout the house, from incredible stained glass to the art tiles on the house’s remarkable number of fireplaces to the design motifs that were in vogue at the time, like sunbursts.

“I started to count them one day,” says Boehme, “and then I stopped because I was busy doing something else, but I think I got to about 40. They’re hidden all over.”

Winchester Mystery House historian Janan Boehme shows the details of the Winchester Mystery House, including ornate ceiling medallions, top left, floor grates, bottom left, and the famed “door to nowhere,” right.

Of course, it’s the unconventional architecture of the house itself that continues to capture the cultural imagination. Other than two people she hired early on to help her with plans before going it alone, Winchester designed the house herself. Her father was a successful carpenter who made decorative pieces for Victorian homes, which might explain where she got her first taste of architecture and construction.

“When she was growing up, that stuff was going on basically right in the backyard,” says Boehme. “Her father had a shop right there on the adjoining property. Sometimes, I wonder if this was kind of an homage to her dad.”

Ignoffo, who wrote “Captive of the Labyrinth,” also thinks Winchester’s husband, William Wirt Winchester, could have inspired Sarah with his own love of architecture. He died in 1881, after they had been married for 19 years.

When considering the question of why Sarah would take on this

perpetual building project by herself, Ignoffo puts it in a larger cultural context; in the 1880 and 1890s, the nation was having what she describes in her book as an “architectural awakening.” Interest in the craft was running high, and for a person of means, architecture was not necessarily an outrageous hobby to pursue.

“I mean, there wasn’t even such thing as a professional architect yet,” says Ignoffo in an interview. “Certainly, people had been designing amazing things for thousands of years, but to go to school and get educated to be an architect was a new thing.”

So how did Winchester do? Well, in her own estimation, not great.

“After the earthquake, she told her niece’s husband how ashamed she was of her skills,” says Ignoffo. “These are not the words she would have used, but maybe it would have been a good idea to have an engineer, you know.”

But perhaps that’s yet another paradox in the Winchester Mystery House story: Sarah’s approach to architecture may have been unconventional, but the fact that there’s nothing like what she built is a big part of what continues to make it so compelling.

In 2020, the Winchester Mystery House celebrated 100 years of being open to the public. The couple who first turned it into a tourist attraction, John and Mayme Brown, were extremely controversial, even in their time. They amplified the false rumors that had been spread about Sarah Winchester and basically solidified them in the public consciousness. On the other hand, they took a property that was considered to have absolutely no

value and turned it into a place that continues to draw visitors from around the world.

“I guarantee this house would not still be here if it weren’t for them,” says Boehme.

Is the majority of interest in the Winchester Mystery House still centered around goofy ghost stories? Absolutely. However, with Boehme just installed as the house’s first official historian within the last decade — though she first started working there in 1977 as a tour guide — the approach to the real role that the Winchester Mystery House has played in San Jose’s history seems to be growing in importance. While tour guides still talk about ghosts, and ghost hunters still come looking for them, there seems to be a

shift away from centering the haunted history around Sarah Winchester and toward what people say they’ve experienced themselves in the house. It’s a subtle change, but an important one, and Ignoffo — who hammered previous management’s approach to the house’s history in her book — is glad to see it.

“Who are we to say what somebody experiences or doesn’t?” she says about the many claims of ghostly sensations made by visitors and staff to this day. “But I’ve always felt like the historical, three-dimensional Sarah Winchester is more interesting than the caricature.”

Details: The Winchester Mystery House is located at 525 South Winchester Boulevard, San Jose.

Palo Alto’s Elizabeth F. Gamble Garden is a calming hub for history and horticulture

BY STEPHANIE LAM

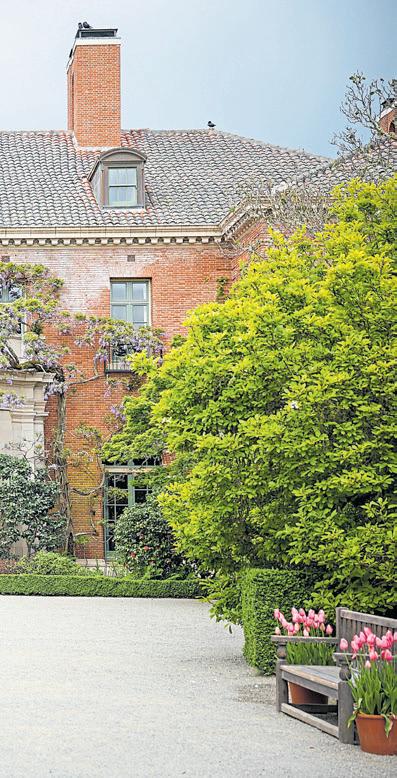

In the midst of the hustle and bustle of Palo Alto — where a cutting-edge technology company can be found on nearly every corner, and luxurious cars and homes line the neighborhoods — sits a humble garden, undisturbed and frozen in time.

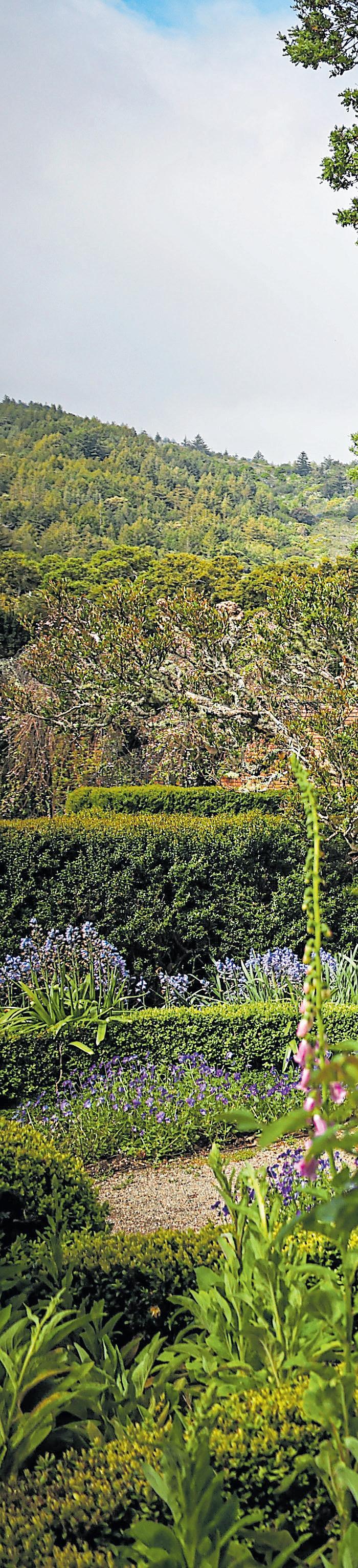

Here, regal Colonial-style buildings rest on 2.5 acres, with lush green vegetation sprouting up all around. Multicolored flowers peel open their petals and reach towards the sky. People dress in plaid gardening clothes or simple T-shirts, wearing digital cameras around their necks and wide-brimmed sun hats. They walk slowly, savoring the site of one of the city’s oldest properties — the Elizabeth Gamble Garden.

“It’s a place to come and get

away,” said Mica Pirie, executive director of the garden, on a recent April afternoon. “My cheesy little thing I say is that it’s a calm in the center of the silicon storm.”

Located off Embarcadero Road in Old Palo Alto, Gamble is a historic public garden dedicated to providing horticultural enrichment and education for community members. Garden staff and volunteers host a number of yearlong events, from educational programs and gardening classes to luncheons and guided tours.

This year marks the 40th anniversary of the garden opening to the public — but the Gamble estate has been around for much longer than that.

The property’s three-story

house was built in 1902 and served as home to Edwin Gamble, the son of Procter and Gamble’s co–founder, his wife and their four children. Among them was Elizabeth, who would inherit the estate upon her father’s death in 1939.

Over the years, Elizabeth preserved the architecture of the house and filled the estate with elaborate gardens. Smaller buildings were added, including a Tea House in 1948 that served as an area to entertain guests.

When Elizabeth died in 1981, she left her house and garden to the city. For years, the City Council debated what to do with the property, before the Garden Club of Palo Alto led a

as the Tea House and Carriage House have been transformed into elegant gathering spaces.

“It’s exciting, it’s fun and a response to how the community is using the space and what we want to do for it,” Pirie said.

already blooming.”

Cherry trees are also in season in the spring, Ancheta adds.

community campaign to restore and maintain the estate. In 1985, Gamble Garden opened to the public for the first time.

Maintaining the integrity of the buildings is important for volunteers and staff, Pirie said. There’s even a dedicated volunteer group that keeps track of what needs to be maintained — the dark roof tiles, antique lighting system or anything else that has been worn down over time.

The first floor of the house is kept as a little museum filled with old black-and-white photographs of the Gamble family, along with some of their belongings. But other parts of the building at Gamble, such

The building’s architecture is breathtaking, but when spring rolls around and the sun starts to shine, the garden is the main attraction.The area is a hotbed for dozens of flower and edible plant species, which are planted along winding dirt paths. Occasionally, it will also be home to Saturday morning yoga sessions or monthly garden luncheons.

On one hot April morning, Garden Manager Ella Ancheta and Director Cory Andrikopoulos take a break from gardening and lounge in the staff’s break room, which also doubles as a makeshift storage space for more gardening supplies. They talk back and forth, listing out several different flowery attractions that visitors can look forward to in the summer months.

“We’re going to start adding a bunch of fruit trees,” Andrikopoulos said. “The oranges are

Their small pink petals flutter every time there’s a breeze. “People stand underneath there, and it’s like they’re getting rained on.”

And then there’s the Puya Flower. Six years ago, staff welcomed the drought-resistant plant to Gamble. No one has seen it bloom — until now. The plant’s stem shoots out from a mass of thin, dull-green, spiky and droopy leaves. Its stem resembles the color and structure of asparagus, but once the buds come in, the Puya will look like an intricate bouquet of small flowers.

Then there is Elizabeth Gamble’s favorite flower, the iris. The garden even grows a special type of iris named after her; the pale blue Elizabeth Gamble irises are planted close to the paved pathway so they can be easily seen by visitors. Even Ancheta considers them standouts in a landscape full of delights.

“I’m just so happy when I see them growing well and very vigorously,” she said.

The historic modernist homes from midcentury have a devoted Bay Area following

STORY BY MARTHA ROSS

SUGANO

When Diane and Bob Reklis bought their Eichler home in Palo Alto’s Palo Verde neighborhood in 1979, they weren’t necessarily looking to be part of one of America’s great experiments in residential design and social progress.

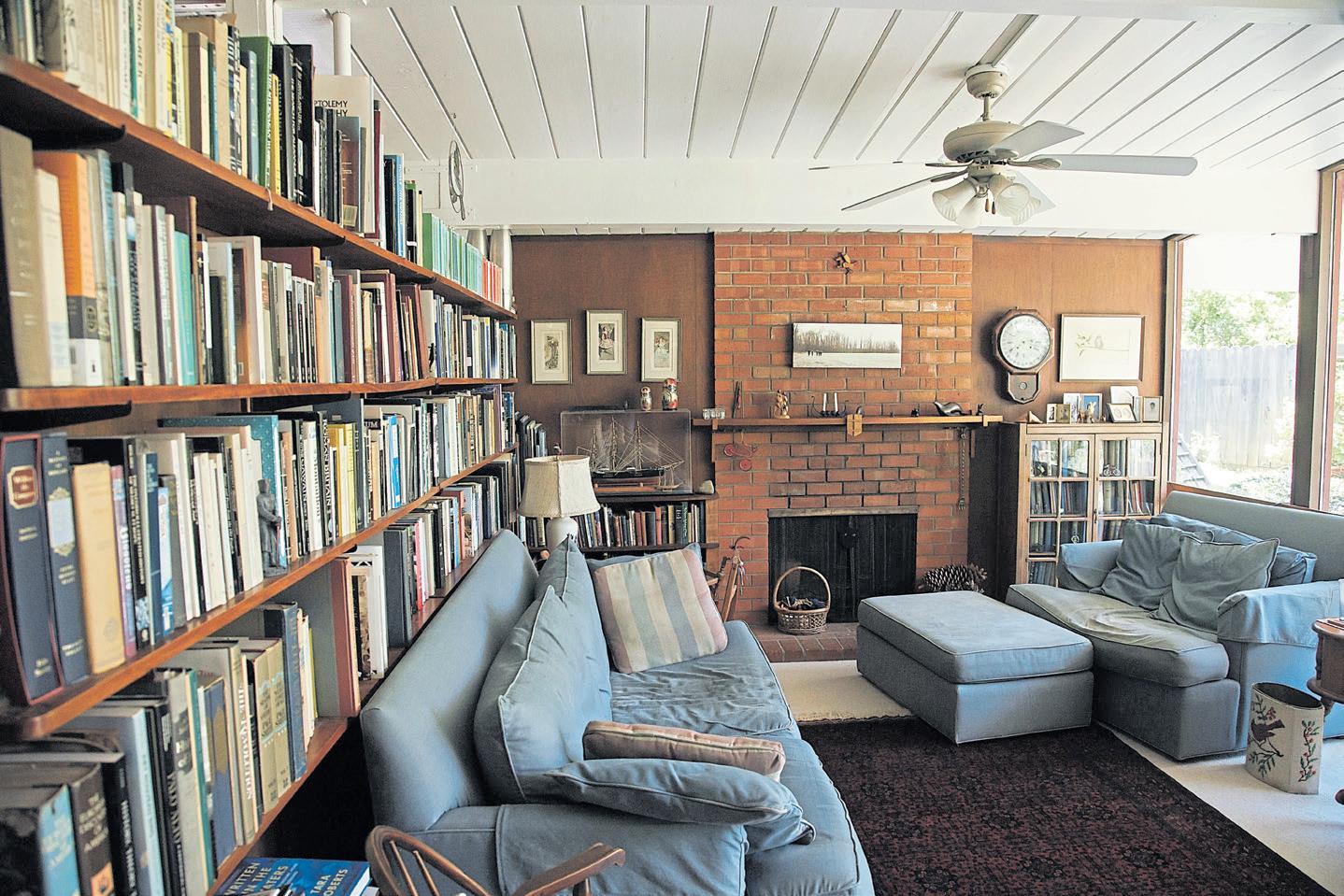

Parents of three daughters, they wanted to live in a family-friendly neighborhood near Bob’s job at Lockheed. But they were drawn to the Eichler brand of stylish, affordable modernist homes. They especially loved the open layout, with floor-to-ceiling glass doors that opened onto the side and back yards, encouraging that California concept of yearround indoor-outdoor living.

“When the kids got roller blades for Christmas, and it was raining, we could let them rollerblade up and down the halls, because there were no carpets. It was great for families,” Diane Reklis said.

The pair are among a very special and enthusiastic group of Bay Area homeowners. They live in what have become known simply as “Eichlers” — the sleek, single-story tract homes that could be the

setting for an episode of “Mad Men.” From the late 1940s to the 1960s, pioneering developer Joseph Eichler and his company mass-produced nearly 11,000 of these Frank Lloyd Wright-inspired residences in the Bay Area and other parts of California to support a booming post-World War II population.

In the Bay Area, there are Eichlers everywhere, usually clustered together in San Jose, Contra Costa County, the Peninsula and Marin County.

Among Eichler owners, there are a fair number of designers, artists and other creative types. Palo Verde, for example, was home to engineer Douglas Engelbart, the inventor of the computer mouse, while Steve Jobs grew up near Eichler homes in Mountain View and once said their “clean and simple” design inspired his vision for the first Apple products.

It’s easy to get Eichler homeowners talking about their homes and neighborhoods. From the street, the classic Eichler neighborhood is a tableau of individually varied flat- and sloped-roof homes that presents a certain American ideal of visual harmony and community.

“It’s a caring, caring neighborhood,” said Soo-Ling Chang, a jewelry designer who has lived in her art-filled Palo Verde home for 53 years. She recalls that her home was a hub for kids when she was a stay-at-home mom to her two sons. These days, she appreciates the block parties organized by neighbors like Katie Renati and the way they all share fruit picked from each other’s trees or help when a new family moves in or has a baby.

Chang also says the “diversity and inclusion are wonderful,” with neighbors of different races and nationalities harkening back to the way Eichler introduced the concept of Diversity, Equality and Inclusion (DEI) to the American suburbs decades before the term existed. As the son of Jewish immigrants,

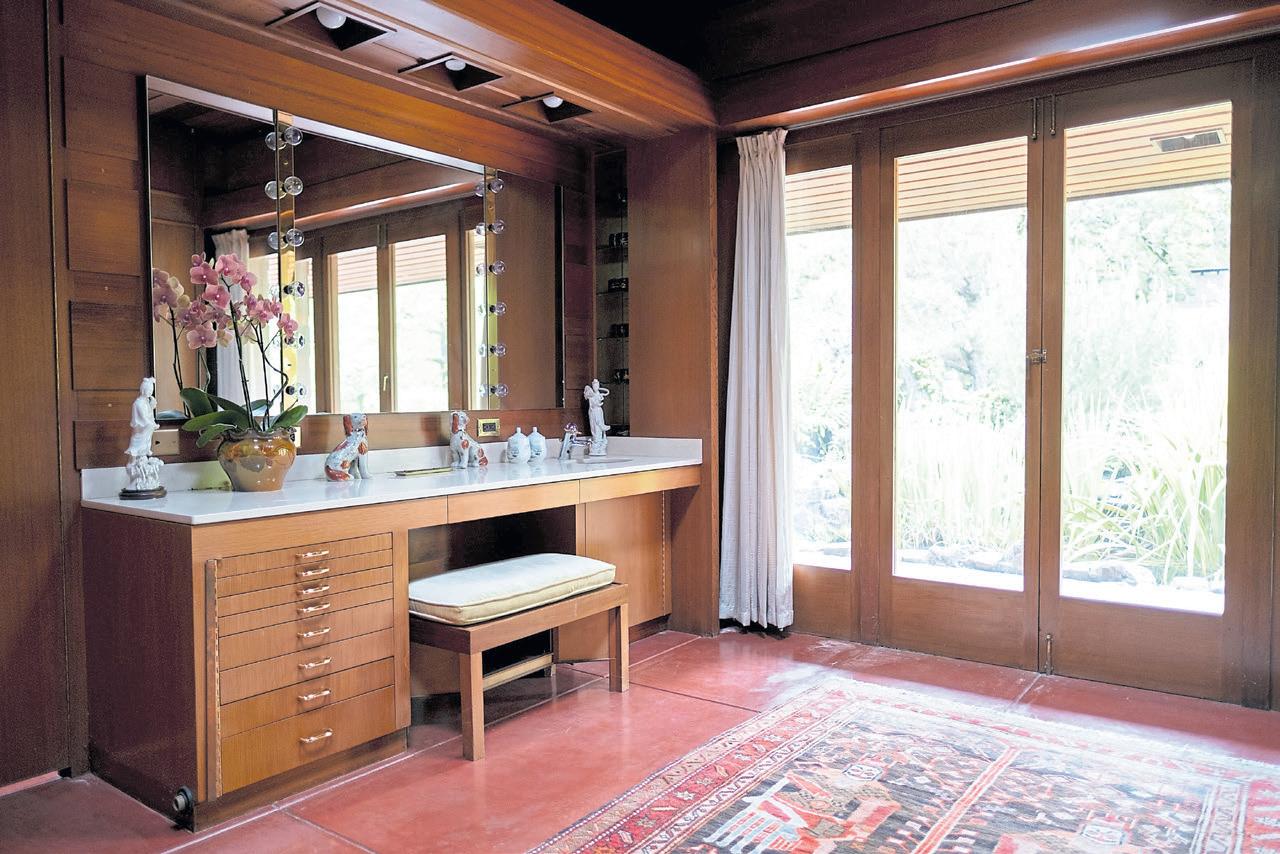

A Buddha statue, above, brings visual drama to the backyard, while the primary bedroom, right, brings in puddles of light with floor-to-ceiling windows at of Swati Kapoor’s Eichler home in Palo Alto.

Eichler, who died in 1974, sympathized with society’s underprivileged, his son Ned Eichler wrote in The Mercury News in 1993. That’s why he began selling homes to Black families in the 1950s and fought for integrated neighborhoods when it wasn’t popular for a prominent American businessmen to do so.

Grant Reiling, a former architect who designed schools and museums, spent three years looking for the right Eichler to buy in Walnut Creek’s Rancho San Miguel neighborhood in 2010. A big selling point for the

home he chose was the mahogany wood paneling and other original features.

“As soon as I walked in the door, I thought, this is it,” he said. Even during a recent upgrade, when he replaced the original radiant heating in the concrete floors, Reiling has leaned into the Eichler aesthetic with vintage exterior colors, a Le Corbusier chaise lounge and other furnishings that are evocative of earlyto-mid-20th-century styles.

Similarly, the Reklises have kept much of their four-bedroom home’s original dark-wood

panelling. But they’ve filled their living room and main hallway with shelves of beloved books as well as antiques, 19th-century family heirlooms and models of old sailing ships that Bob likes to build.

The first Eichler-branded tract went up in Sunnyvale in 1949. Each home, selling for $9,500, featured three bedrooms, one bathroom, redwood siding, open interiors and radiant floor heating. Over the years, the designs for each new subdivision were modified or expanded to include different roof lines, more bathrooms or even a central outdoor atrium. Eichler and his architects “were always experimenting and getting feedback from

the people who lived in homes,” said Dave Weinstein, Eichler expert and former features editor at CA-Modern magazine.

Though Eichler himself had no architectural training, he had an innate love of design, especially for modernist architecture, according to his son Ned, who died in 2014. Eichler and his wife moved out to “liberal, cosmopolitan” San Francisco in the 1920s so he could work in her family’s wholesale food business — “a job he hated,” his son wrote in The Mercury News. After their two children were born, he insisted the family live

“As soon as I walked in the door, I thought, ‘this is it.’”

Grant Reiling

in a rented Frank Lloyd Wright house in Hillsborough before and during the war.

After Eicher embarked on his second career as a master builder in 1947, he worked with architects like Bob Anshen, Quincy Jones, Frederick Emmons and Claude Oakland, who shared his love for Wright’s modernism and his view that America’s new neighborhoods should advance social goals, Weinstein said.

Paul Adamson, an East Bay architect, preservation advocate and author of “Eichler: Modernism Rebuilds the American Dream,” noted that modernism

neighborly interactions. Streets were not laid out in grids, but in curves and cul-de-sacs that were amenable to pedestrians, kids’ games and block parties. Many Eichler neighborhoods also were built with community parks, clubhouses and swimming pools, serving as California versions of the New England “village green,” Adamson said.

Sean Giffen is a second-generation Eichler homeowner in Palo Alto’s Greenmeadow neighborhood. He raised his five children in his late parents’ home, which is next door to the Eichler-designed community center and swimming pool. His mother and other moms once ran a preschool in the community center while he was at the pool most days, especially in the summer.

“It was awesome growing up here,” said Giffen, while “All summer long, we went to the pool every day, and we swam on the swim team. And, you know, our parents didn’t have a worry in the world about what we were up to.”

Grant Reiling’s

developed in Europe to provide quality housing for the working class. Translated to the United States, that meant building affordable homes so that G.I.s returning from World War II and their families could access the American dream of home ownership.

Eichler’s architects also introduced innovations to suburban planning to encourage

For a time around the ’80s, Eichlers stopped being cool, written off as small, outdated, even shabby, according to Weinstein. But as thought leaders like Jobs began to sing their praises, so, too, did a new generation of home buyers who wouldn’t think of drastically altering their look and didn’t mind zoning in some areas that prevent second stories. These days, a well-maintained Eichler in a desirable Bay Area neighborhood can sell for several million dollars or more.

Swati Kapoor said she and her husband, Shekhar, could have chosen a bigger house than their 1,700-square-foot Eichler when they moved to Palo Alto in 2011. But during their home search in Palo Verde with their son Shaan, then 5, they found a block party in full swing. They also realized that the house, especially with its huge yard, would be more than sufficient.

“Our son, he was the one who came into the house and said, ‘I love it, I love it,’” Kapoor said.

STORY BY STEPHANIE LAM

Off the busy Interstate 280 in Woodside, past a metal gate and down a winding road wedged between grassy fields is one of the Bay Area’s best-hidden — and most iconic — landmarks: Filoli House and Garden.

The 16-acre property is home to pristine English Renaissance-style yards, where hundreds of flowers and trees of all shapes and sizes grow from every crevice. A handsome, massive Georgian Revival mansion rests on the property. Nearby, half a dozen trailheads lead guests into preserved woodlands.

Since Filoli’s creation in 1917, aristocrats, dignitaries and even presidents have made the long

trip to soak in the splendor. But on any given day, the gardens are open for residents of all ages and backgrounds to admire.

“These historic sites were built by wealthy individuals for their families and close friends,” said Kara Newport, president and CEO of Filoli. “To have it kind of now become a community center and community cultural asset is really important. It feels like full-circle to me, like this is a true way of giving back to the community.”

Filoli’s first owner, William Bourn, named the estate as a sort of portmanteau of his personal motto: “Fight for a just cause; love your fellow man; live a good life.”

Bourn spent years commissioning the mansion. The space grew to accommodate 56 rooms con-

An employee picks edible flowers for a tea event, top, while a visitor explores Filoli House and Gardens in Woodside.

sisting of a mix of bedrooms and bathrooms alongside grand entertainment spaces, like a ballroom and reception room.

A separate wing near the mansion served as a staff work and housing area. The living spaces were small but cozy areas close to the massive kitchens and butler’s pantry, where the staff conducted their day-to-day duties.

After Bourn’s death in 1936, the Roth family purchased Filoli. Lurline Roth and other family members helped expand the estate to include the luxurious gardens. She donated the estate to the National Trust for Historic Preservation in 1975, saying “I have always felt that such a place should be preserved ... and made a center of horticulture and cultural activities.”

The house was empty when it was given to the trust, as most of the furniture and artworks were sold at auction or taken by the Roths to their new home. But over the years, both families donated items back to Filoli.

Now, guests can see evidence of the mansion’s legacy — from faded photographs of the owners and tapestries to the old-fashioned dining tables and fine china.

Fioli is known for its polished aesthetic. However, staff members and volunteers don’t want that to deter people from having fun on the property.

On one April morning, staffer Rachel Young, who often coordinates and leads tours for various community groups, strolls around the grounds, watching

Photographs show an era when aristocrats, dignitaries and even presidents made the long trip to Filoli House and Gardens in Woodside.

guests slowly trickle in and take in the site. They take pictures, point at the different flowers in bloom and talk excitedly with one another.

“We encourage them to go play, go lie down on a blanket, bring a sketchbook,” she said.

“Do something that is more imaginative than just respecting the appearance of a place.”

And there are plenty of things people can do at Filoli.

This summer, for instance, guests will have a chance to explore the property’s more untamed and untouched side, with a special exhibition featuring six enormous troll sculptures made from recycled materials. Each troll will be positioned under several towering trees along hiking trails for visitors to admire and interact with.

Sunny and warm weather means the garden gets its time to shine. Filoli offers outdoor events for people to learn new skills or socialize — all while breathing in the scent of fresh flowers and witnessing the blossoming estate. There’s the Insider’s Garden Tour, where people can purchase tickets in advance and get treated to a detailed walk-through of Filoli.

For more large-scale events, they can sign up for summer Flora Parties, where selected flowers on the property can be turned into personalized flower arrangements.

“Everybody’s here together but doing their own thing,” Newport said. “Filoli is such a good place to choose your own adventure.”

STORY BY JASON MASTRODONATO AND STEVE PALOPOLI

On the last Tuesday of each month, Matias Bombal heads over to the Orinda Theatre and does what he was born to do: entertain Contra Costa County theatergoers like it’s 1941.

In an attempt to make the experience as close as possible to what moviegoers experienced when the theater opened that year, Bombal plays newsreels and a cartoon from the era, along with a 20-minute musical short and some previews.

Finally, Bombal jumps on stage to introduce the film. His commanding voice, charisma and enthusiasm are pitch-perfect as he transports movie lovers back in time.

But none of it is as important to capturing that historic feel as the Orinda’s magnificent architecture.

Recognized by the Art Deco Society of California as “Moderne,” the building finished construction just after the Art Deco explosion of the ’30s. Bombal calls it, “modern baroque,” but with Art Deco influence.

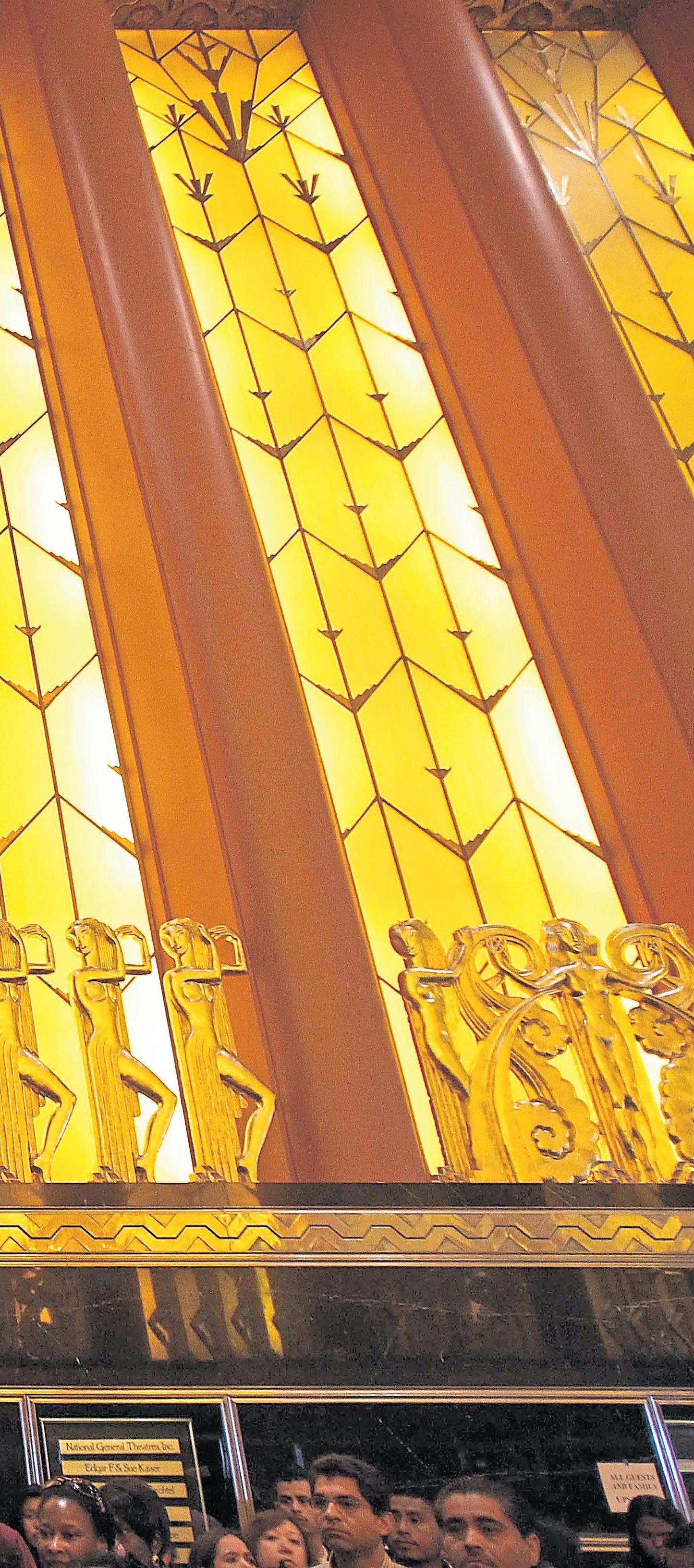

Paramount Theatre in Oakland includes a well-lit grand lobby featuring gold and emerald green throughout. There is no wallpaper throughout the theater; everything was hand-painted.

JANE TYSKA/ STAFF ARCHIVES

“The circular lobby of the Orinda has a feeling of the living room,” said Bombal, a program director at the Orinda who also has a nationally syndicated radio show discussing modern cinema. “It’s intimate.”

This year is the 100th anniversary of the birth of Art Deco at Paris’ L’exposition internationale des arts decoratifs et industriels modernes; in English, the International Exhibition of Modern Decorative and Industrial Arts — Art Deco, for short. The exhibit was held in 1925, just after World War I, and presented the world with a glimpse of the newest designs that reshaped architecture at the time.

Why the big change? There was a rejection of the establishment following the war, which altered every part of society. Instead of looking to the past with warm nostalgia, people had their eyes set on the future as they hoped to create a new world amid the temporary peace before World War II.

Designers began using new materials like aluminum, fiberglass, bakelite and neon. The style is said to have represented power and opulence, hence the heroic human figures, floral motifs and bold geometric shapes. The entire idea was rooted in progress; humans were developing, artists observed, and new buildings would come with a hope for a brighter future.

At the exhibit in Paris, there were 15,000 exhibitors from 20 countries, and 16 million people were estimated to have visited between April and October.

“It was seen as the launching pad of the Art Deco style that was bubbling up in Europe to the world stage,” said Therese Poletti, the preservation director of the Art Deco Society of California. “It was a huge exposition that focused on the new decora-

tive arts in France. It was a way for France to get back the design mantle it lost in World War I.”

In California, a lot of the new buildings were constructed after the recovery from the 1906 earthquake. With the population boom followed a lot of Spanish Colonial and Victorian designs. But the Art Deco explosion between 1925 and 1940 wasn’t lost on this region.

“You can find a lot of Art Deco

here if you look for it,” Poletti said.

Here are five great Bay Area places with Art Deco influence that are worth a visit:

Orinda

The inviting scenery first starts when you’re driving down Route 24 and catch a glimpse of the theater’s original neon pink and green sign.

“The vertical sign looks like a shark fin, so it looks like the vertical is cutting through the air and moving forward,” Bombal said.

Once inside, you’ll notice something different from some of the other theaters of the era. With many movie palaces,

like the Paramount Theatre in Oakland, “the first thing that happens is you walk in, and everyone looks up and nearly passes out falling over backwards, because it’s so impressive to look at it,” Bombal said. “But the Orinda is a round, circular space, which feels more intimate. So it’s like you’re walking into your living room at home.”

The lobby is small but colorful, with American beauty rose, bright blue, midnight blue and a woven carpet that matches the ceiling painting by Anthony Heinsberg.

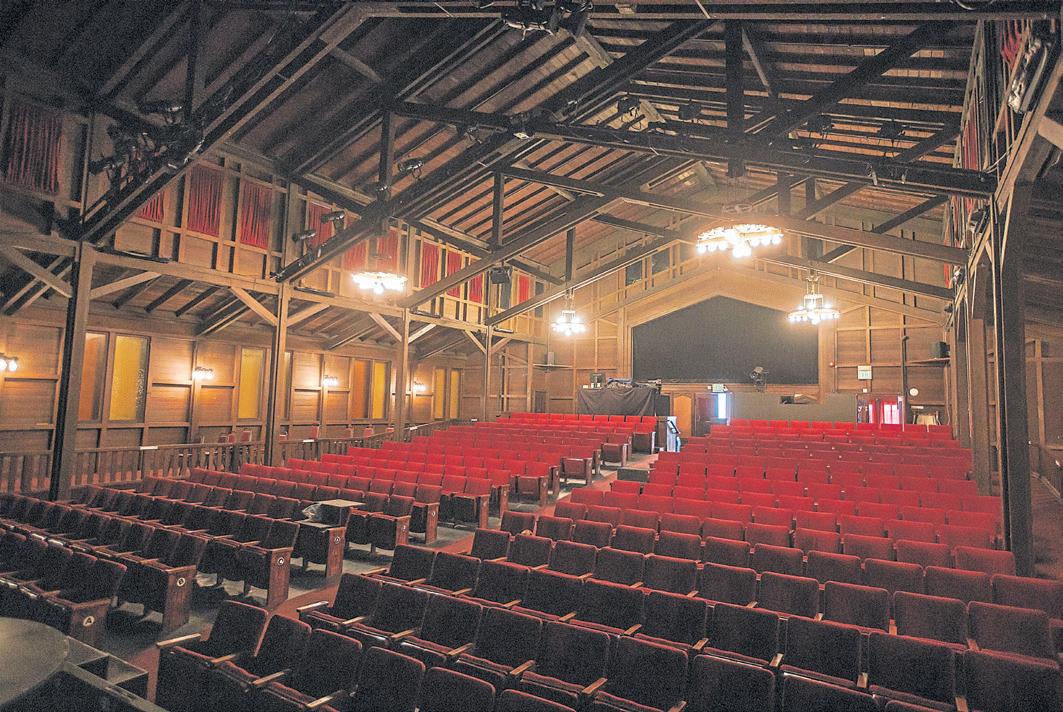

“You have a nice thematic closed space, then go up a long flight of stairs, and you’re in a big auditorium,” Bombal said.

“And it’s much larger than you’d think it’d be, based on the

narrowness of the entrance you come through.”

The architect was Alexander Aimwell Cantin, who built many theaters in the Bay Area. He also remodeled some older spaces to make them look more modern.

“In the case of the Orinda, he throws in illustrations and artwork, which is not necessarily congruent with these design styles at the time,” Bombal said.

The theater stayed open until 1984, when it was scheduled to be demolished to pave the way for a new complex to be built. But local preservationists fought the plans in court, and in 1985, the California Supreme Court ruled in their favor. New seats were put in as well as additional renovations that took years to complete before the theatrer reopened in 1989.

Today, the Orinda continues to show old and new movies as well as host live performances from Broadway stars, musical acts, standup comedians and cabaret performers.

Details: Located at 4 Orinda Theatre Square in Orinda; https://www. orindamovies.com.

San Jose

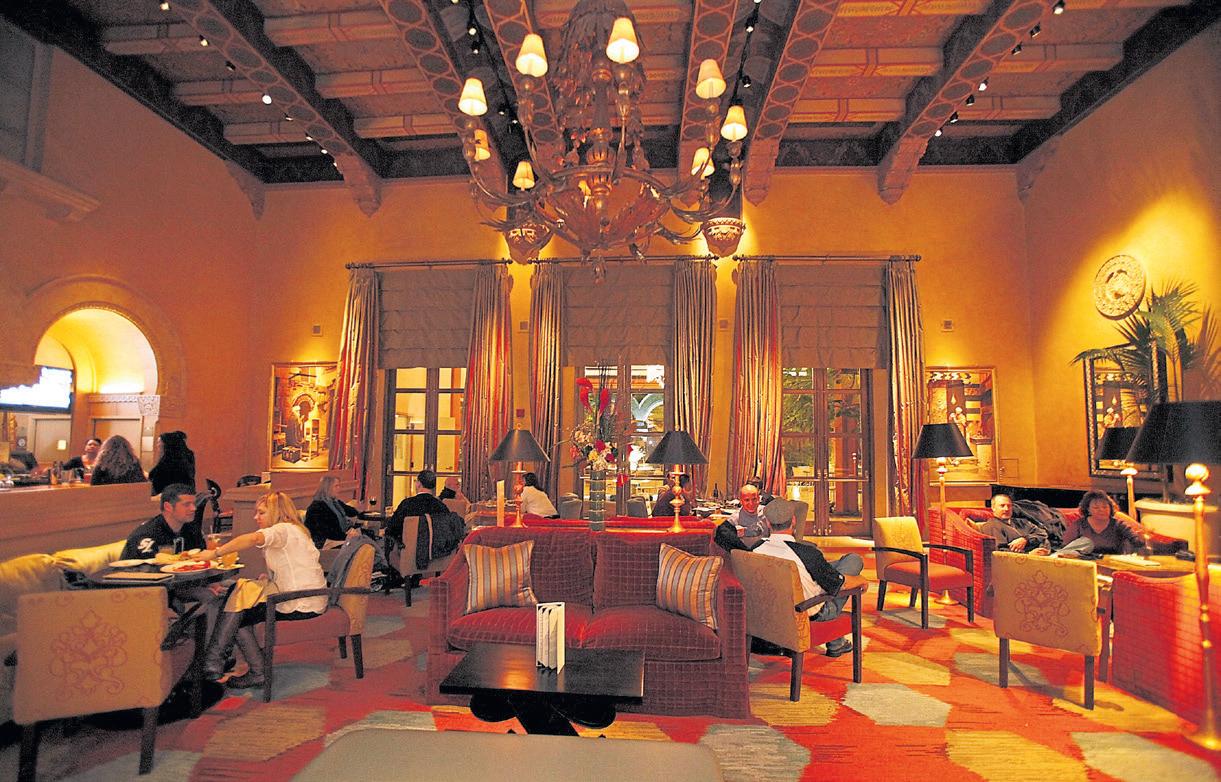

Built in 1931, the 10-story Hotel De Anza may be the crown jewel of San Jose’s Art Deco buildings.

Featuring a marquee with zigzags and geometric floral motifs and a pink neon sign scheduled to light up again this summer, the hotel is a standout in the city, and it was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1982.

There are more floral designs in the lobby and conference rooms, with large paintings, archways, chandeliers and decorative elements that also incorporate some Spanish Colonial designs.

Facing demolition in the 1970s, the hotel was saved by the now-defunct San Jose Redevelopment Agency, which helped renovate it in 2015.

An ownership group headed up by Northern California hotel owner Dhaval Panchal purchased the property last year and temporarily closed the hotel as they began renovations. The electrical panels, which

Theatre has met considerable success since being refurbished and reopened as a multiplex in 2008.

spokesperson Maxine Reyes described as, “previously being held together with duct tape and glue,” were restored.

Investing in such renovations

“shows the community that this family is here to stay, and they want this landmark to be this special hotel everyone knows it for,” Reyes said.

Details: Located at 17 Notre Dame Ave. in San Jose; https://www.hoteldeanza.com.

Palo Alto

While the Stanford Theatre is recognized as a landmark by the Art Deco Society of California,

some purists may have a nit to pick with that designation, as the building in the heart of downtown Palo Alto was actually designed more in the tradition of neoclassical architecture.

Perhaps it’s most accurate to say that while the outside of the theater reflects neoclassical’s obsession with simplicity and more subtle design, the interior is an absolute explosion of Art Deco showmanship. Lined floor to ceiling with Deco’s obsessive geometric patterns and alight with the reds and golds of the archetypal Californian movie palace, the Stanford has become one of the most popular places

in the U.S. for fans of classic cinema to gather week in and week out.

It wasn’t always that way. Like Art Deco itself, the Stanford Theatre is celebrating its 100th anniversary this year, and newspaper clippings from the time — permanently on display in the theater’s annex, which is a treasure trove of posters, lobby cards and more from films scheduled to be shown — reveal that the theater was the center of attention when it opened on June 9, 1925. By the 1960s, though, the Stanford had fallen into disrepair.

Ironically, it took the death of Fred Astaire, one of the stars

whose movies the Stanford had shown in its heyday, to bring it back to life. David Woodley Packard, son of Hewlett-Packard co-founder David Packard, organized a film festival honoring Astaire’s work shortly after the icon’s passing in 1987. It was so successful that the Packard Foundation purchased the theater for $7.7 million and set about restoring it, making it a permanent safe space for Hollywood’s Golden Age.

Over the years, the Stanford has become famous for its themed festivals — Cary Grant, Alfred Hitchcock, Val Lewton, Vincente Minnelli and Audrey Hepburn are just a few of the actors and directors to be celebrated recently — and for some rather clever pairings by programmers in its double features. (“Bride of Frankenstein” and “Sunset Boulevard”? We see what you did there, and we don’t know which is the grande dame and which is the monster, either.)

With its sparkingly preserved architectural flourishes, wide range of programming, family-friendly affordability and mighty Wurtlitzer organ played between evening showings — you can count on at least a few awestruck moviegoers videoing these performances every weekend — the Stanford is possibly the most important home for classic cinema to be found, not only in the Bay Area, but anywhere.

Details: Double features ThursdaySunday. 221 University Avenue, Palo Alto. stanford.theatre.org.

One of the most prominent architects in the Bay Area during the 1920s was Timothy Pflueger, who’s got his name on some of the most stunning theaters in the region. But none

is quite like this one.

“The Paramount is probably Pflueger’s Art Deco masterpiece,” said Poletti. “Someone once compared his role there to a symphony conductor — in charge of a lot of artists, craftsmen and builders — and it’s not a bad analogy, since the building is a true work of art.”

Pflueger hired some of the era’s leading painters, sculptors and muralists, who leaned into towering mosaic and classic Art Deco patterns to create the country’s second-to-last theater with more than 3,000 seats (Radio City Music Hall was the last).

After the stunning neon sign greets visitors from the outside, the well-lit grand lobby features gold and emerald green throughout. There are tall designs along the walls and figurelike shapes crafted in. Throughout the theater, there’s no wallpaper; everything was hand-painted.

There are Art Deco lamps and curtains, geometric shapes on the rugs and magnificent displays of light all around; look up from the auditorium, and the lightbulbs resemble an Egyptian figure.

Similar to the Orinda, the Paramount was also slated for destruction, but the Oakland Symphony bought it in 1972 and started a series of matinee concerts.

The Paramount became a California Registered Historic Landmark in 1976 and a National Historic Landmark in 1977. Today, it’s the home of the Oakland Symphony and is one of the area’s leading destinations for popular performers in art, music and theater.

Details: The theater offers 90-minute tours on the first and third Saturdays of the month. Located at 2025 Broadway in Oakland; https://www. paramountoakland.org.

Another one of Pflueger’s masterpieces, the Alameda Theatre, opened in 1932 and is known as “The Little Paramount.”

“Because it’s just as spectacular but at a smaller scale,” Poletti said.

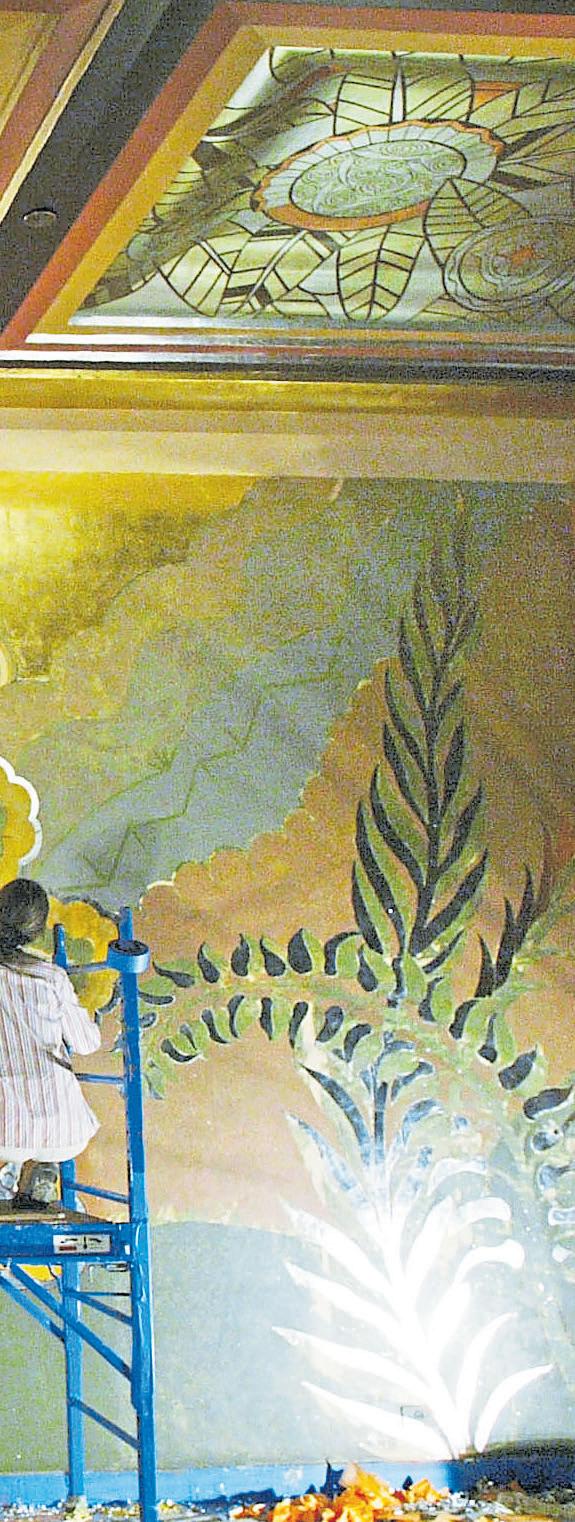

The towering pink and orange neon sign lights up Central Avenue. The tall, floral patterns on the facade are signature Art Deco designs. The grand lobby features more flowers and figures, though much of the lobby has been updated.

The building closed as a theater in the 1980s and was later used as a gymnastics studio and roller rink, before being redesigned in 2008. The ticket booth and concession were updated to complement the Art Deco.

The original decorative finishes were restored and the metal leaf structures made to sparkle again. The painted stage curtain, carpeting ceiling grilles and most of the light fixtures were also restored by the Architectural Resources Group.

The ceiling has layers of decorative finishes and a wall mural, though they were painted over with a swan motif in the ’40s. The mural was uncovered and restored as part of the 2008 project.

The theater is now operating as an eight-screen multiplex showing new films, and it also hosts popular events in Alameda’s Park Street Historic District.

“It’s a great example of how a movie theater can be saved, with smaller theaters added, but they do not mar the original, main auditorium,” Poletti said.

Details: Located at 2317 Central Ave. in Alameda; https://www.alamedatheatres. com.

DOUGLAS

BY JOHN METCALFE

Around the Bay Area, the Marin County Civic Center is known as Frank Lloyd Wright’s greatest achievement. The largest constructed work to come off his drafting table, it’s a shining Versailles of inimitable vision that may be quite an eye-opener for those coming in simply to fight a traffic ticket.

But Wright’s quieter legacy lies in the houses he designed for ordinary people. There are roughly a half-dozen around the Bay Area, executed in a modest yet alluring style he called Usonian (his shorthand for architecture that’s uniquely “United States of North Independent America”). Young professionals wrote the star architect, begging him to make their dream homes. To their great surprise, he often agreed, descending with cape and cane to manifest beautiful designs for the ages.

Born in 1867 in Wisconsin, Wright moved to the Bay Area in the 1950s to oversee his projects here. His time in the region marked an important period in his career for both projects finished and unrealized. Among his never-built structures were a wedding pavilion for Berkeley’s Claremont Resort & Club and a butterfly-themed Bay Bridge with a lush, hanging garden. Even Hollywood has benefited from his local work: Since his

Though the historic Maynard Buehler House in Orinda has a garage, Wright’s designs showed a distinct lack of garages.

death in 1959, his architecture has been featured in films from “Gattaca” to George Lucas’ first movie, “THX 1138.”

“Extending over nearly sixty years and including a broad range of building types, Wright’s Bay Area works are distinctive mainly for their diversity and the unprecedented nature of many of them,” writes Stanford professor emeritus Paul V. Turner in his 2016 book, “Frank Lloyd Wright and San Francisco.” “They demonstrate, perhaps more than his buildings in any other location, the amazing variety and innovation of his creations and the fertility of his imagination.”

So what exactly is a Usonian home?

“It’s a made-up term. He wanted to see an indigenous American architecture flourish here in this country and not ape European architecture,” says William J. “Bill” Schwarz, a licensed architect in Marin County who worked on the Civic Center and was close with Wright’s local protege, Aaron Green. “He sought an expression of American democracy — freedom, in other words, extension, openness. Democracy is fragile, but it’s open, and it’s vulnerable. So Wright’s little houses are a

little bit fragile, and they have lots of glass.”

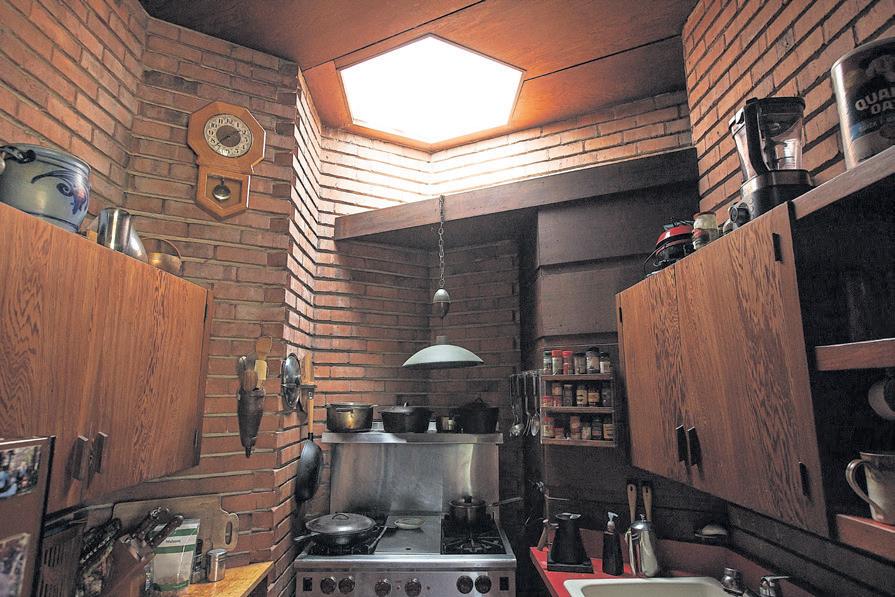

The houses were to be affordable and accessible to the middle class; Wright even produced “Usonian Automatic” plans, like DIY Sears kits, for folks who weren’t professional builders. They typically had modular and repeating motifs, a concrete-slab floor with radiant heating, fluid spaces that blurred room separations and flat roofs that often sprung leaks, the bane of his career.

Unpainted wood and other natural materials factored large, as did sprawling glass windows that opened onto courtyards and green spaces. There was a distinct lack of garages. “He had a lot of ideas about what he thought was a waste of resources,” says John H. Waters, preservation programs director at Chicago’s Frank Lloyd Wright Building Conservancy. “To him, a car was perfectly fine — this is someone from Wisconsin. But he thought, ‘Why spend money on the walls of a space for a car, when you can spend it on your own space?’”

The Hanna House on the Stanford University campus is the earliest and one of the best examples of Usonian principles in the Bay Area. Erected in 1937, the house relies on a grid system of hexagons — like a bee’s honeycomb — and lacks traditional right angles.

“There’s not a 90-degree corner in the house in terms of the arrangement of the walls,” says Schwarz. “He thought it was an interesting alternative that would facilitate human movement through the spaces

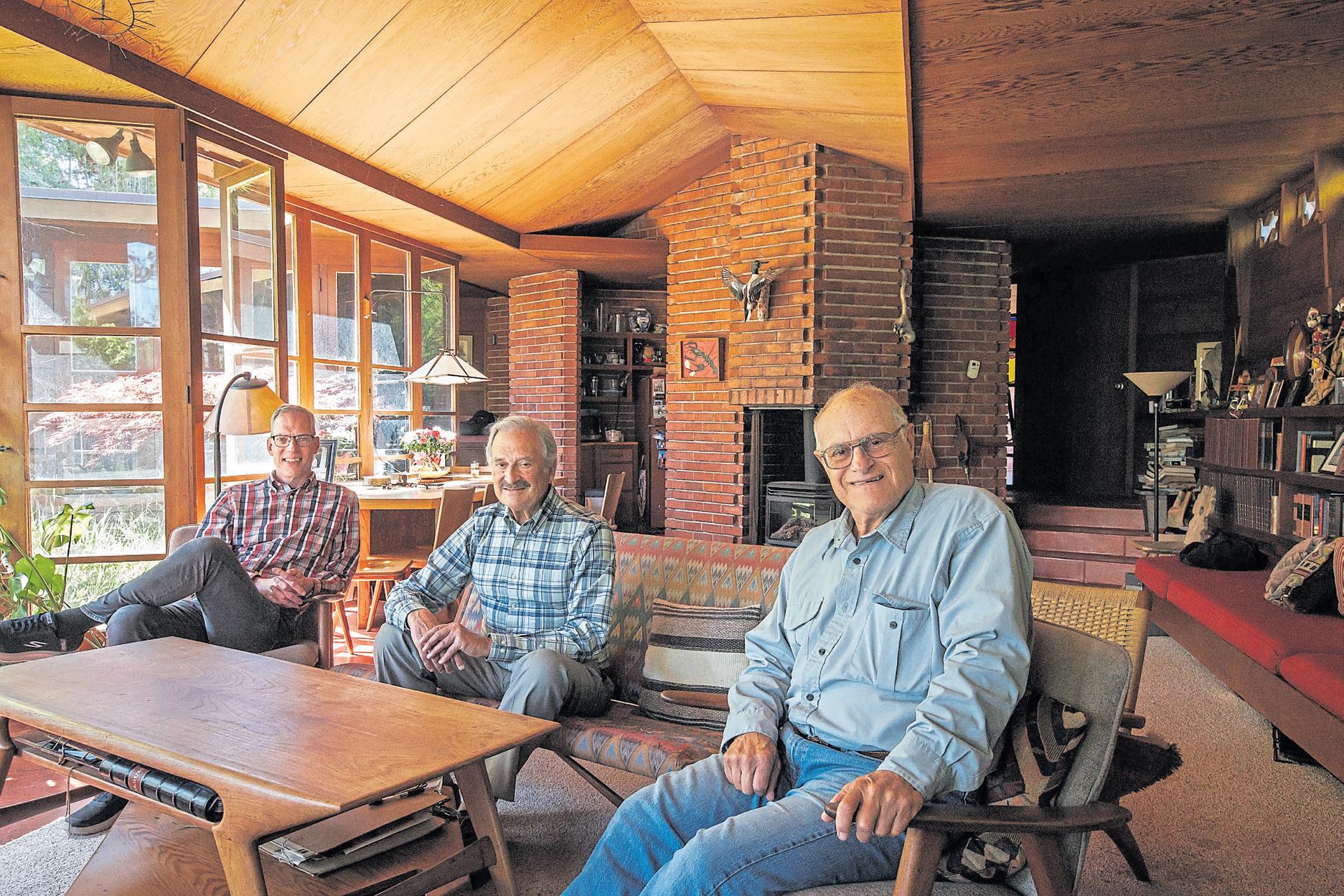

Top right: Homeowner Laurence Frank, right, sits with architects John Waters, left, and William J. “Bill” Schwarz, center, at the Bazett-Frank House in Hillsborough, a home designed by Frank Lloyd Wright.

Bottom right: It is hard to find 90-degree angles on the exterior view of the BazettFrank House; odd angles were details often found in Wright’s designs.

DAI SUGANO/STAFF

— you’d bump up against a 90-degree corner, but you’d kind of glance off a 120-degree corner. He was an innovator, and if anything came to his attention that was different than what’s been done, he would explore it.”

Next up for Wright was the Sidney Bazett House in Hillsborough, built in 1940 with a similar hexagonal grid and “sleeping boxes” that opened up to the outdoors. These homes gain their names from their owners; this one’s also known as the Bazett-Frank House for a subsequent owner who built an addition. It’s also important to note that most of these homes are privately owned and not available for tours.

The Bazett home features the smallest bedroom Wright ever designed, which for unclear reasons was nicknamed the “Mummy Room” — perhaps because it felt as cramped as a sarcophagus? Famed architect Bernard Maybeck stopped by during its construction, according to Turner’s book, and expressed himself as “both puzzled and intrigued.”

The Robert Berger House in San Anselmo was based on a Wright plan but built by the owner, who beginning in the early 1950s, would pour into it 20 years of backbreaking labor.

The thick walls were made by dropping rough-cut stones into wood frames and flooding concrete over them to create a rustic desert vibe with visible stone in the surfaces. Near the end, the owner estimated he’d lifted more than a million pounds of material and must have the “heaviest house in Marin County.”

These painstaking design touches were vintage Wright. “He would design everything, if he could. He’d design the silverware if you let him,” says Schwarz.

For instance, the Berger home is notable for having the

smallest structure Wright ever devised — a doghouse for the owner’s 12-year-old son Jim, named Eddie’s House in honor of the special pup. The canine hut had all the traits of Wright’s style, including a hidden entrance in the back and an overhanging roof that was quite flat — and leaked. The story goes the dog refused to use it, which the son recalled as being “kind of depressing.”

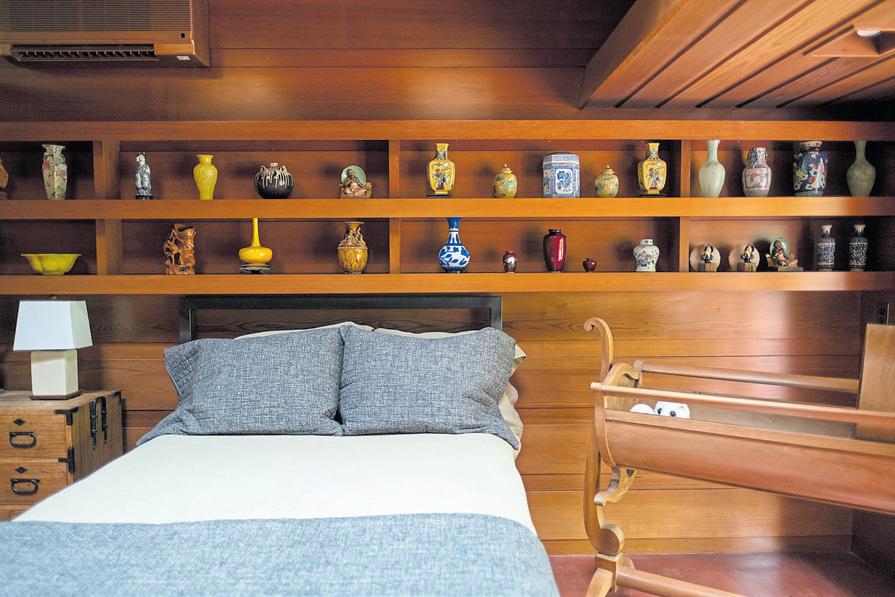

Wright designed at least two other existing homes in the Bay Area: the circa-1950 Mathews House in Atherton, remarkable for its lovely use of organic materials, and the late-1940s Maynard Buehler House in Orinda. An example of Wright’s fandom for Asian art and culture, the latter property had enchanting gardens created by Henry Matsutani Sr., lead designer of the restored Japanese Tea Garden in Golden Gate Park.

Above: The Marin County Civic Center building in San Rafael is the largest of Frank Lloyd Wright’s projects, but the legendary architect designed a half dozen homes in the Bay Area with his signature Usonian style.

RAY CHAVEZ/STAFF

Top left: A guest bedroom view inside the Maynard Buehler House in Orinda features gorgeous wood built-in shelves.

DOUGLAS DESPRES FOR BAY AREA NEWS GROUP

wrote the architect, according to Turner. “Every day, she meets the mailman half way up the block looking for a letter from you. She is worrying herself sick about rising building costs.”

The husband described Wright as the “most domineering person I ever met,” and the wife considered him “arrogant” and “self-centered.” One issue of contention was her request for a bigger kitchen, which reportedly led Wright to remark: “Madame, you do not seem to realize that women have been emancipated from the kitchen.”

It’s true that Wright could rub people the wrong way. There’s a reason that Ayn Rand cited him as the partial inspiration for Howard Roark, the individualist-architect hero of “The Fountainhead.” He had strong opinions underlying his work and did not suffer criticism without a fight.

Mark Anthony Wilson, an art historian and professor living in Berkeley, recalls being a child and attending one of Wright’s lectures. Two students in the audience decided to be smart alecks and ambushed him about his belief that everything in a home must have a function.

Bottom left: Sunlight from a hexagon-shaped skylight illuminates the kitchen in the Bazett-Frank House in Hillsborough.

DAI SUGANO/STAFF

The young owners who originally commissioned Wright went through some alarm seeing their construction budget double. “I’m sitting around here watching my wife become a nervous wreck!” the husband

“They said, ‘In one of your houses in Wisconsin there’s a staircase that doesn’t go anywhere — it just leads up to the top of a platform, and there’s no access. So why did you put in a nonfunctioning staircase?” recalls Wilson, author of the 2018 book, “Frank Lloyd Wright on the West Coast.” “He said, ‘OK, I’ll tell you why I designed that. I designed it for the two of you to climb up to the top and jump off.’

“That was rewarded with laughter, including from my parents. And that’s classic Wright, of course.”

In the end, the owners of the Buehler House made peace with Wright, and the wife even called him a genius. “Overlooking the leaks in the roof,” they wrote to him, “we can’t imagine living anywhere else — we love it.”

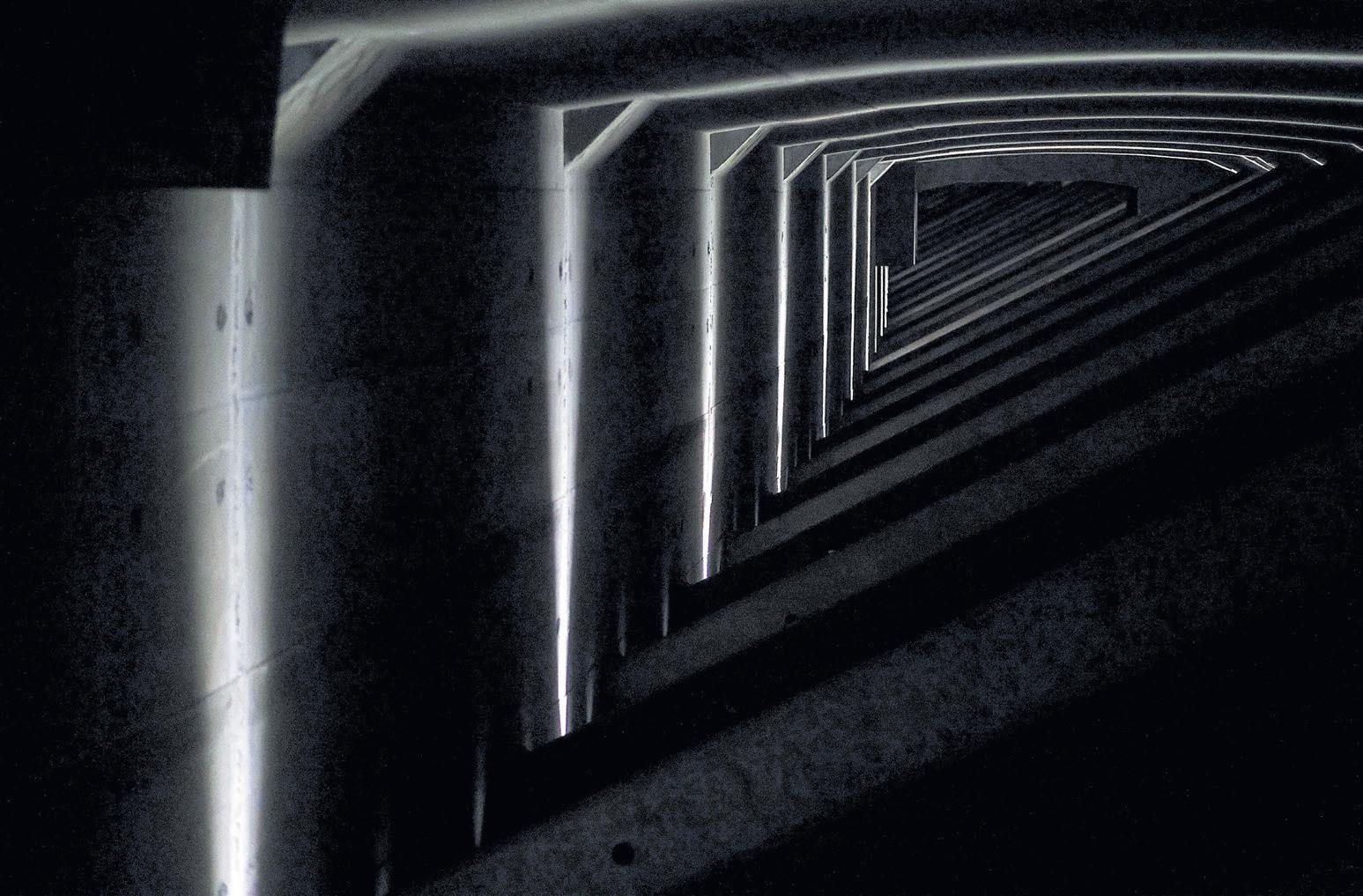

Despite enormous challenges, the rebuilt Bay Bridge has become our most incredible architectural marvel

BY KATIE LAUER

There’s a surreal serenity atop the world’s longest self-anchored, single-tower suspension bridge, crowned by a thick blanket of fog more than 500 feet above the rippling tides off Yerba Buena Island’s eastern shore.

From here, the 300,000 daily commuters below who cross the newest, asymmetrical side of the Bay Bridge look like a frenetic ant highway, as 15-mph winds blow towards the perennial stack of vibrant shipping containers that frame the Port of Oakland. Barges lazily float under the 1.4-mile skyway, while Coast Guard patrols fade into the horizon past Treasure Island.

Once hotly debated as an experimental, costly pitch to restore the vulnerable eastern span in the wake of the 1989 Loma Prieta earthquake, the rebuilt Bay Bridge now has more than a decade under its belt serving one of the Bay Area’s most vital transportation arteries.

The iconic tower that boasts this panoramic view is home to one of the last remaining architectural secrets of the Bay Bridge: A last-minute final design touch was a case of life imitating art.

The single anchored suspension section on the eastern span of the Oakland Bay Bridge is as beautiful as it is functional.

ARIC CRABB/STAFF

As revealed for the first time by Bart Ney, who quickly became one of the most prominent public faces of the bridge as the California Department of Transportation’s Bay Area spokesperson in the early 2000s, the creative team at Popular Mechanics magazine took a little extra creative license when putting the Bay Bridge on the cover of their June 2007 issue.

“They put parapet walls up there and a little inspector standing on the top of the bridge,” Ney said. While the roof was originally intended to be flat, he said there was still time and money in the budget for a moment of inspiration. “When our designers saw that, it was so compelling, we redesigned the top of the bridge.”

Roughly 24 years and $6.5 billion in the making when it reopened to Labor Day weekend traffic in 2013, the Bay Bridge was the most expensive public works project completed in California — a title it still holds, along with its place as the fourth most expensive such project in the nation and the widest bridge in the world.

One of the biggest architectural challenges, Ney said, was physically bridging the design gap between structural longevity, functional use and artistic flare.

“This bridge was built out of fear — fear of an earthquake, fear of death,” Ney said. “The inspiration was to counteract that fear. When you look at this bridge, you’re supposed to feel better.”

They started with designs to fulfill “lifeline criteria” laid out within the highest seismic safety standards in the state. There were two basic rules: The new landmark had to be able to withstand the largest ground motions from an earthquake, but it also needed to be immediately accessible to emergen-

cy-service vehicles following violent tremors.

Of the roughly 100 other, self-anchored suspension bridges in existence, Ney said a majority only support pedestrians.

“To build one at this scale was rare, and then to build one that was record-setting was really rare,” he said, admitting that even he wondered at one point if the groundbreaking plans would ever break ground. “The Bay Bridge has proven itself, not just with the looks, but with its performance. The scale that this was done is herculean.”

As a vast team of architects, engineers and transportation officials started brainstorming a structure that could physically withstand extreme ground movement — jolts that are estimated to occur every 1,500 years — local leaders and community advocates wrestled over a way to ensure that the

“This bridge was built out of fear — fear of an earthquake, fear of death. The inspiration was to counteract that fear. When you look at this bridge, you’re supposed to feel better.”

Bart Ney, California Department of Transportation Bay Area spokesperson in the early 2000s

two segments were put in place Dec. 7, 2006,

new Bay Bridge was a “signature” design that represented and served the East Bay.

“Parts of the bridge had to be invented that didn’t exist before,” Ney said, explaining that even though the science behind the self-anchored suspension bridge wasn’t novel, no one had previously attempted to construct a structure that could safely span the Bay. “There were really difficult times when engineering solutions had to come almost out of the ether.”

The final result was a catenary arch — the signature curve formed by the single, 32-inch diameter cable holding the reconstructed span together 1,400 feet above the water — refusing to swing, sway or strain while bearing 35,200 tons of steel, concrete and asphalt.

Ney said the Bay Bridge’s architectural genius could not

Above: The container ship Ever Fame glows at the Port of Oakland as it prepares to set sail under the Bay Bridge on route to Taiwan in 2021.

have been built anywhere else — forged through a uniquely local mix of tragedy, community and ingenuity.

“We had to build a brand new bridge in the same footprint as an existing bridge that carried one of the busiest routes in the nation — all without closing the bridge,” Ney said, recalling the years of heated public debate and strict regulatory oversight that painstakingly slowed construction. “And then we had to make an icon.”

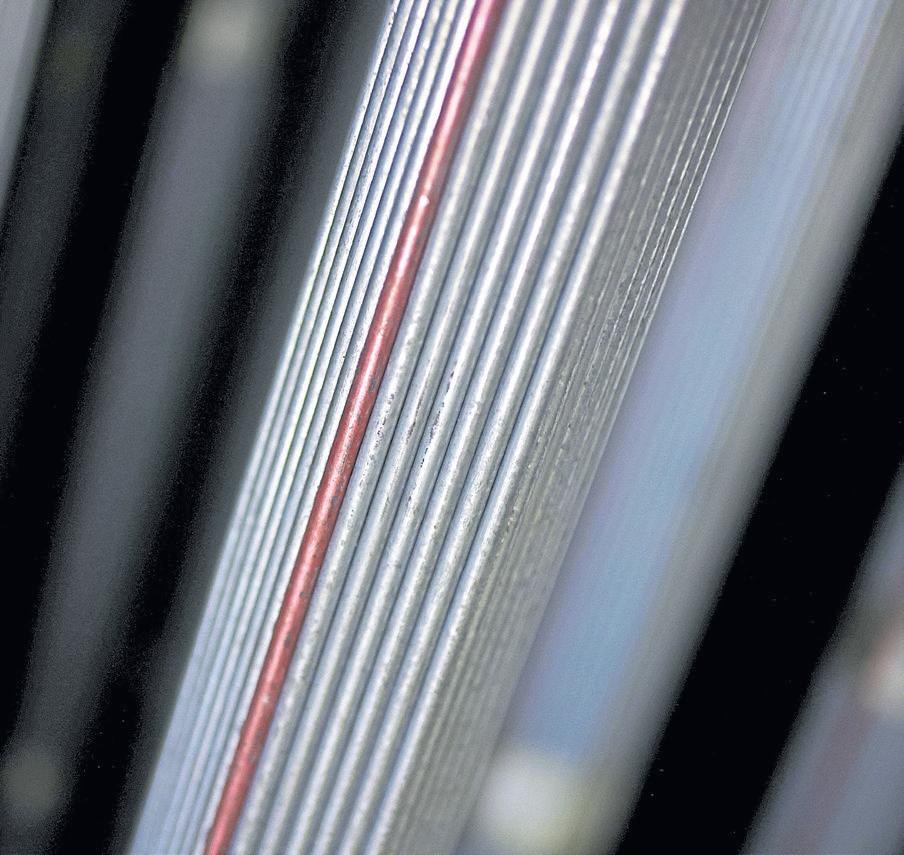

A hinge pipe beam on the bridge’s eastern span includes a spare “fuse” section” designed to help protect from overload.

ARIC CRABB/STAFF

Lower right: Giant cables and bolts secure the eastern span of the Bay Bridge

Part tour guide, part dream coach, Ney’s job was to explain how such a gargantuan feat was even possible, especially built on a strata of unstable mud near a hotbed of seismic activity.

“I was the guy that used to sit out in a boat, hand waving for politicians, engineers and anybody that would listen — over hundreds, maybe thousands

of tours — explaining what we were planning to put in this big hole,” Ney said. “It was not easy to defend, but I definitely felt like I could throw my weight behind it.”

The secret to the Bay Bridge’s architectural sauce is hidden deep within its core, where a network of catwalks, staircases and access ways help protect from unnecessary damage, deterioration or disregard.

Mechanical hums rattle the mile-long interstitial space, married with a cacophony of tires thumping over the hundreds of omni-directional, accordion-style joints that are designed to absorb any displacement, rotation or seismic movement.

Ney proudly notes that the eastern span of the Bay Bridge is designed to last 150 years — twice the life of a standard

bridge — and is outfitted with several components that architects and engineers anticipate will extend the structure’s life even further.

One inevitability, Ney said, is that the concrete will begin to sag. Secondary anchor points, however, are standing ready to secure new cables to pull the self-anchored suspension bridge taut for another century.

Climate control systems within the belly of the bridge keep humidity low to prevent the moist, salty air from compromising exposed portions of the Bay Bridge’s main cable, which are meticulously splayed out into 137 separate bundles in order to loop around the bridge’s single tower. In total, nearly 17,400 pencil-thin wires are then repacked into the main cable, suspended back over the bridge

and self-anchored in cement on the other side.

Twenty hinge-pipe beams were installed below segments of the roadway, which allow steel pipes within the bridge to flex and slide back and forth as the ground shakes but prevent lateral jolts that could jeopardize the bridge’s integrity.

Easily repairable, hollow stress points called “fuses” were designed to absorb the brunt of impact when overloaded — mitigating catastrophic structural damages, similar to a blown fuse at home. Miles of utility lines are funneled through channels and empty pipes to protect essential services during an emergency.

“The idea is that the bridge will potentially live forever,” Ney said. “If the people that are alive then want to keep this bridge, we built this for them.”

STORY BY JASON MASTRODONATO

PHOTOS BY KARL MONDON

It was a near-perfect Friday — in the 60s, sunny and breezy — at di Rosa Center for Contemporary Art, the home of the world’s foremost collection of Northern California art.

The quirky and dynamic collection, mostly curated by late owner Rene di Rosa, is spread out across 273 picturesque acres in Napa in an unusual style that features both indoor and outdoor exhibits. Sculptures like Mark di Suvero’s red geometric wonder, “For Veronica,” and Sam Yates’ 65-foot-tall filing cabinet recognized by the Guinness Book of World Records stand proudly amid the rolling hills.

Every part of the land is used artistically, with the landscape itself a beautiful work of art buzzing with creative energy, making it one of the region’s uniquely designed spaces.

And yet, on this particular Friday, hardly a soul could be found.

Two employees sat at the front desk to welcome only occasional visitors. A friendly tour guide prepared to show a stunning collection of paintings, sculptures and other artistic masterpieces to a group not big enough to field a softball team.

How is it possible that so few people know about this place?

“It’s such a good question,” di Rosa executive Kate Eilertsen said

Mark di Suvero’s “For Veronica” sculpture sits on the lip of a reservoir at the di Rosa Center for Contemporary Art in Napa.

as she pondered the uncertain future on a recent spring day. “I’m trying to figure that out. Part of it is that not everybody loved Rene. He was a controversial figure. Some of the art he collected is not what you’d call beautiful landscapes. It’s controversial. It’s sometimes provocative. Sometimes it’s political. Sometimes it’s hideous. And sometimes it’s great.”

Eilertsen has been around the Bay Area art world for more than 20 years, but she only took over the di Rosa — in all its glory and imperfection — in 2021.

Like anyone who inherits something that doesn’t belong to them, Eilertsen now finds herself balancing tradition against evolution.

On the one hand, she’d love to stick with tradition, keep the art collection in Napa and carry out Rene’s dream of continuing to support new artists that are local, progressive and challenging societal norms.

But she’s also facing the very troubling reality that many Bay Area art venues are struggling. Hundreds of millions of dollars of federal funding to local institutions have disappeared.

And in Napa, the almost 1,700 pieces of art are not being appreciated the way so many folks think they should be.

Eilertsen has a plan.

‘MY GREATEST PLEASURE’

To understand where the di Rosa Center goes next, one must first understand where it started.

Boston-born Rene di Rosa moved to Paris after World War

II in hopes of writing the next great American novel. When that wasn’t happening, he moved to San Francisco to take a job as a reporter at the Chronicle, where he covered the Haight-Ashbury scene. When he came into a small inheritance in the 1960s, he used it to buy 450 acres of land in wine country and began to study viticulture at UC Davis.

But he found himself much more interested in befriending the school’s artists, several who became his lifelong friends.

And in 1982, he was able to sell about half of his property while making enough of a profit to help fund his new passion: collecting art.

After years of collecting with his wife, Veronica di Rosa, they opened the di Rosa Art Preserve to the public in 1997.

“I never regarded myself as having financial ability to do anything except buy art,” he said in the 2004 documentary “Smitten.” “Without it, I can’t imagine how to function. My greatest pleasure is finding a work of art by an artist who has never

sold anything. They are pleased that somebody likes what they’ve done, and I am pleased I discovered an artist that grabs me.”

In particular, he was drawn to contemporary artists who were creating in the Bay Area.

“Bay Area artists are always doing the opposite of what the market wants to do,” said Twyla Ruby, the di Rosa Center curator.

Local painter Chester Arnold remembers what it was like selling a piece to di Rosa.

It was 1997, and Arnold had just painted one of his masterpieces, “Thy Kingdom Come II,” in which a giant ball of junk is