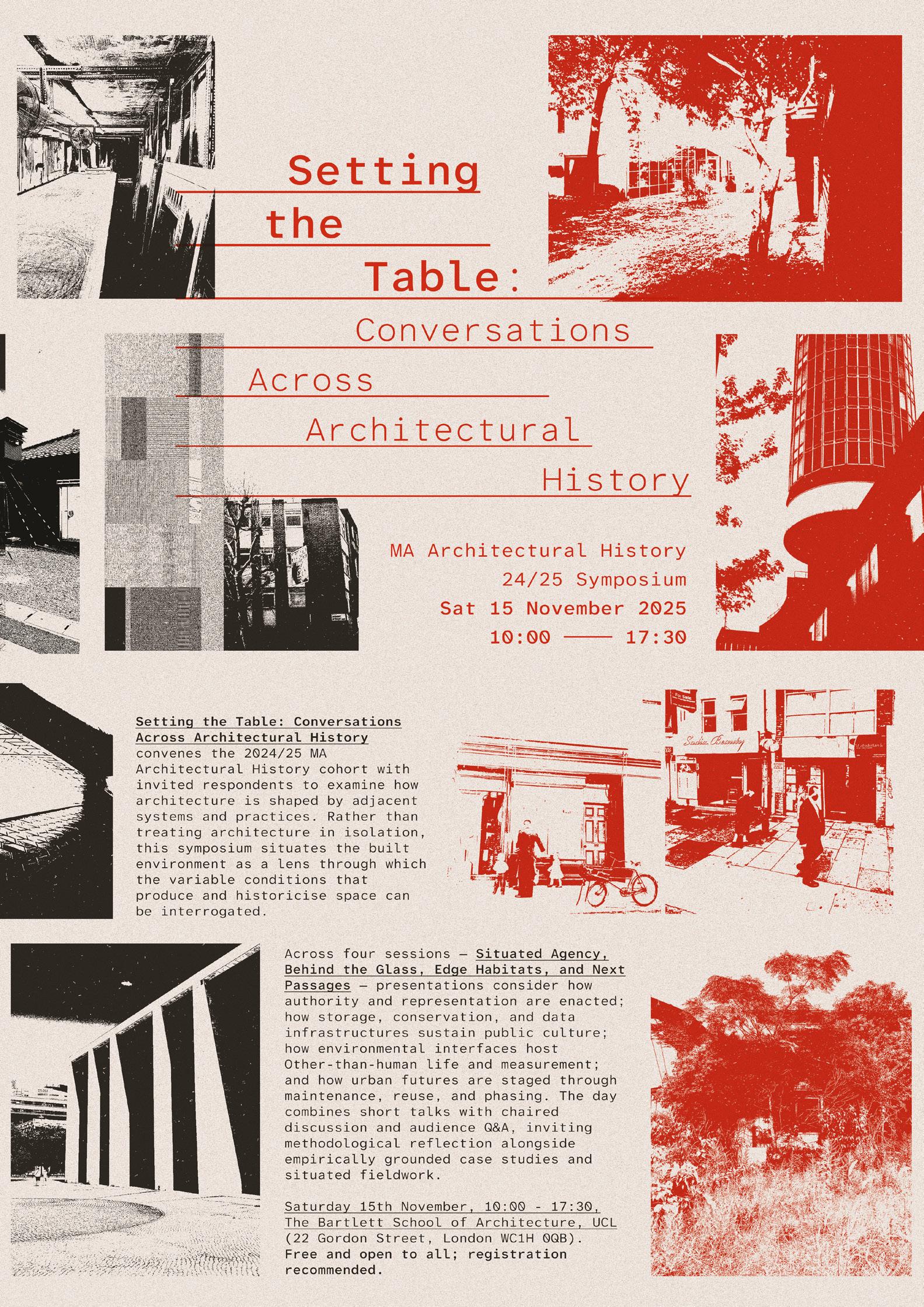

Setting the Table:

Conversations Across Architectural

History

Architectural History MA 24/25

The Bartlett School of Architecture, UCL

Conversations Across Architectural

History

Architectural History MA 24/25

The Bartlett School of Architecture, UCL

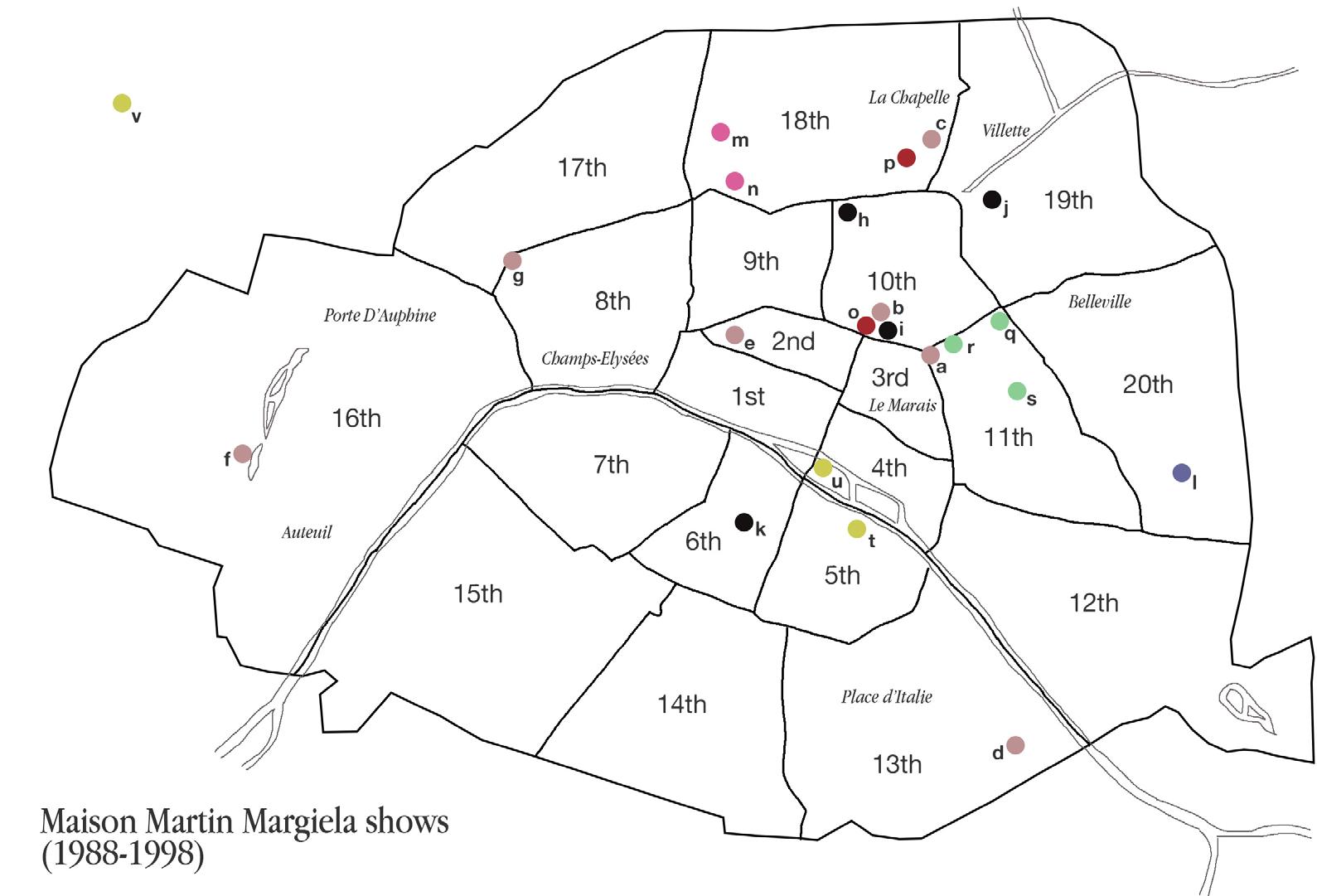

Setting the Table: Conversations Across Architectural History gathers research from the 2024/25 cohort of the Bartlett School of Architecture’s Architectural History MA programme to consider how architecture is shaped by intersecting systems and practices — policy, security, coloniality and decoloniality, labour, sensing, destruction, repair, and representation. Rather than isolating buildings as autonomous objects, the projects within treat these forces as co-authors of the built environment and its histories.

The table is a space of interaction. In the accompanying exhibition, surfaces are ‘set’ with ideas and artefacts — photographs, documents, models, films, and ephemera — so visitors can serve themselves, compare approaches, and assemble their own routes through the material. It echoes the seminar table as a place to gather, question, and exchange, while the surrounding displays show the production of research around a shared centre. The table is a prompt, and an invitation to look closely and think together.

The book carries forward this invitation, unfolding across four sections — Situated Agencies, Behind the Glass, Edge Habitats, and Next Passages each staging its own conversation whilst reflecting a shared commitment to architectural history as a situated, collaborative practice.

Situated Agencies treats architecture as agency embedded in legal, ritual, media, and colonial frameworks. The contributions show how built form shapes and contests political, cultural, and ideological orders: Anna García Molina on Amancio Williams’s unbuilt Church and Preventive Health Ship as a missionary-medical instrument of moral, hygienic, and spatial control; Eden Northcott on the BBC’s acrylic screening of Eric Gill’s Prospero and Ariel and the indivisibilities of contested heritage; Guillermo Gómez Tejera on the Fashion and Textile Museum as transculturation between Mexican modernism and Bermondsey’s cultural economy; Joe Williamson on the BT Tower through Cold War Protestant ritual, telecom myth-making, and surveillance; Zaina Abou Seif on Hassan Fathy’s drawings and prose as affective instruments of cultural sovereignty. Together, the chapters locate agency in procedures, images, and institutions that often remain offstage.

Behind the Glass brings visibility to concealed spaces, practices, and infrastructures that sustain cultural and architectural systems. The papers examine overlooked architectures of work, storage, and documentation: Claudia Vargas Franco rereads Ernö Goldfinger’s 2 Willow Road from its service rooms and routines, proposing ‘partarchitecture’ methods to address archival gaps; Helga Beshiri contrasts display and storage at the Wellcome Collection, the Petrie Museum, and the V&A Storehouse, testing how ‘open storage’ recasts accessibility, provenance transparency, and decolonial politics; Macarena González Carvajal reconstructs the Smithsons’ Painting and Sculpture of a Decade: ‘54–‘64, arguing that exhibition design operates as provisional architecture mediating artworks, viewers, and institutional narratives; Mark Bessoudo reframes Google Street View as an unintentional urban archive within traditions of architectural photography, tracking how pragmatic capture and temporal layering

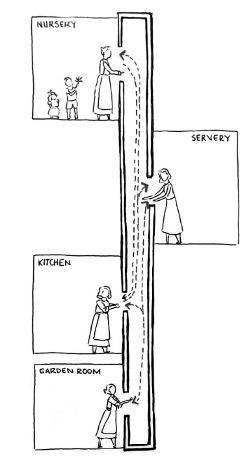

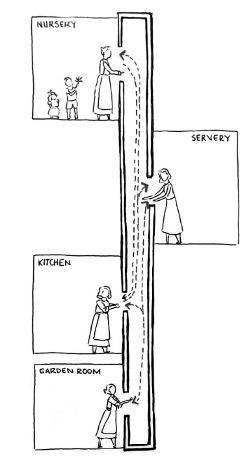

Claudia Vargas Franco, diagram illustrating how the dumbwaiter facilitates the vertical circulation of objects, maintaining the separation of bodies within the house.

migrate into historical interpretation. Mounts, crates, catalogues, servers, and screens emerge as spatial media through which value is produced and public culture kept in motion.

Edge Habitats follows interfaces — arks, tanks, ducts, walls, and data stacks — where environments are sensed, serviced, and made. Treating ecologies as hybrid networks, the essays trace how instruments and protocols negotiate Other-than-human life, evidence, and design across planetary, urban, and domestic scales: Issy MacGregor reads post-Fukushima marine monitoring as radiological architecture — a ‘bucket logic’ in which media apparatuses, tanks, and fish co-produce publics and proof; Qing Tang examines the architecture of digital waste, from retrofitted bunkers to university data centres and online residue, to show how destruction, disposal, and displacement organise material and immaterial ecologies of data; Ertuğ Erpek reconsiders the New Alchemy Institute’s arks and bioshelters through secondorder cybernetics, foregrounding self-regulating habitats of care and feedback; Steven Schultz relocates passive-solar technology from performance metrics to lived routine, showing how the Trombe wall scripts domestic comfort as social choreography. Edge conditions appear as laboratories of cohabitation where environmental claims are tested in practice.

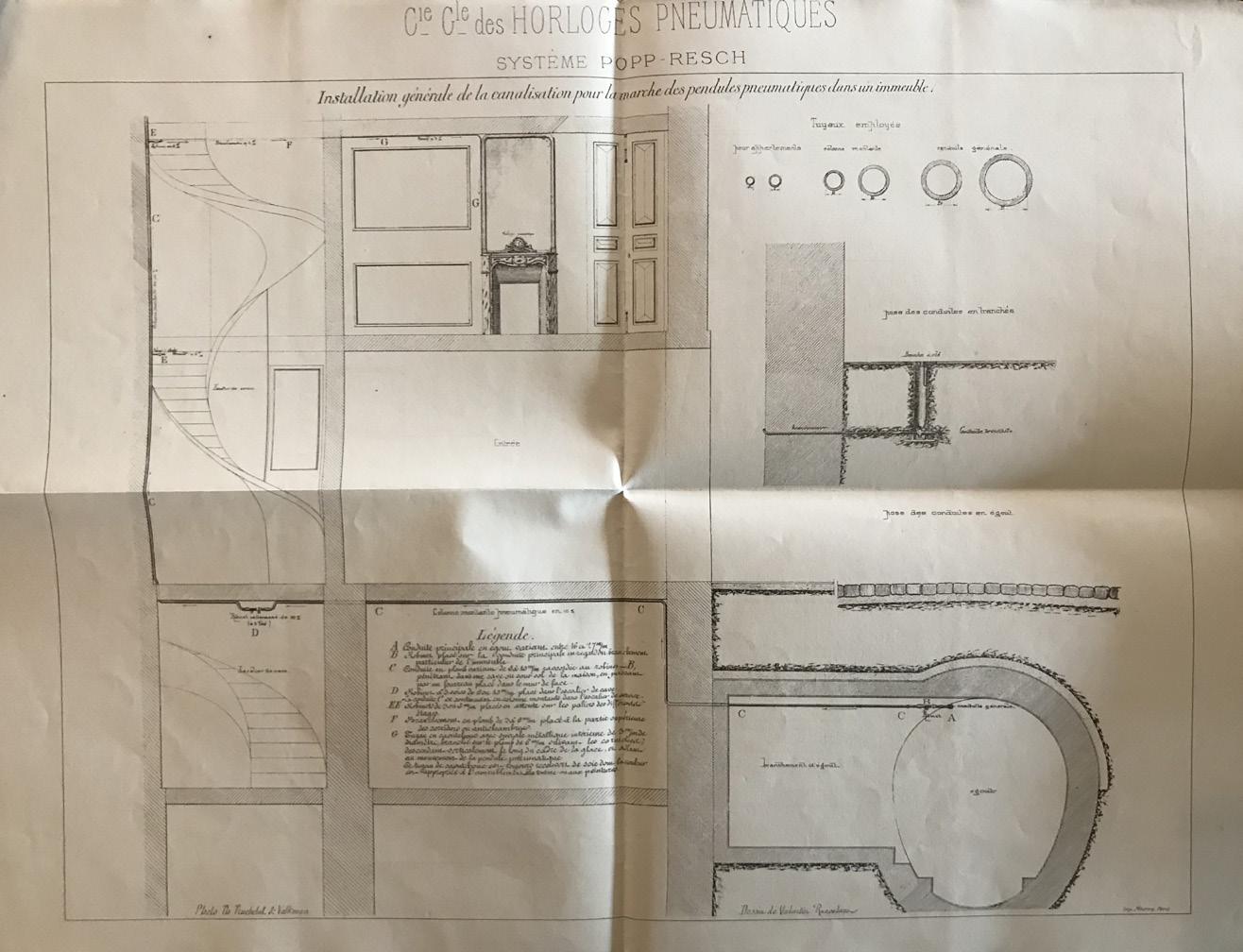

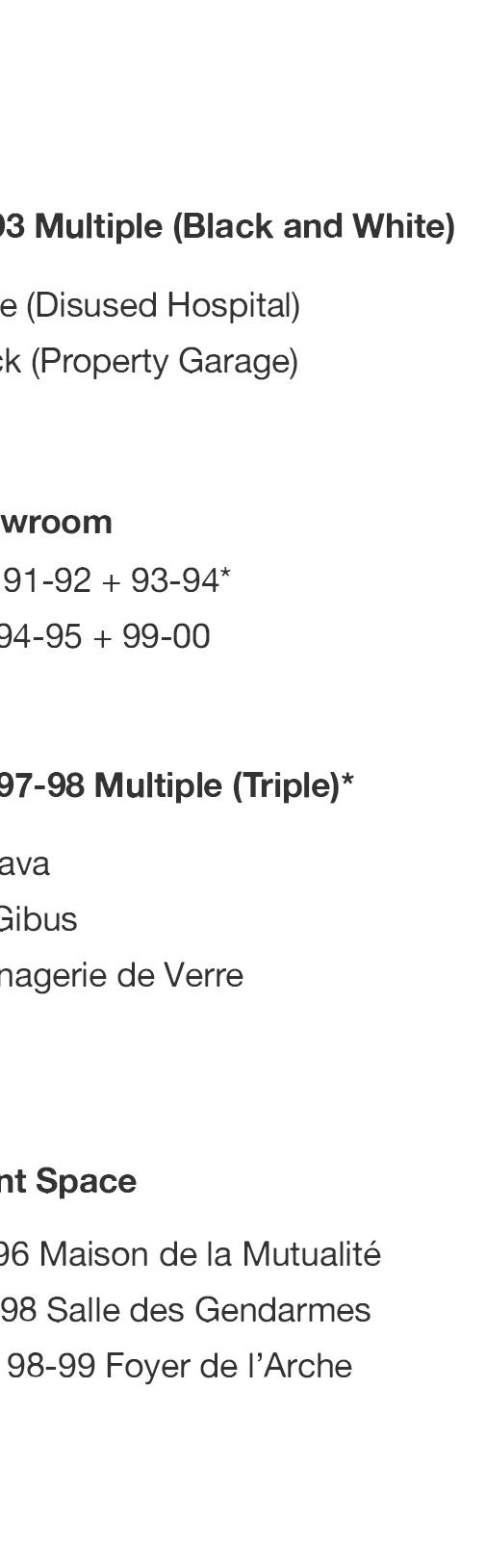

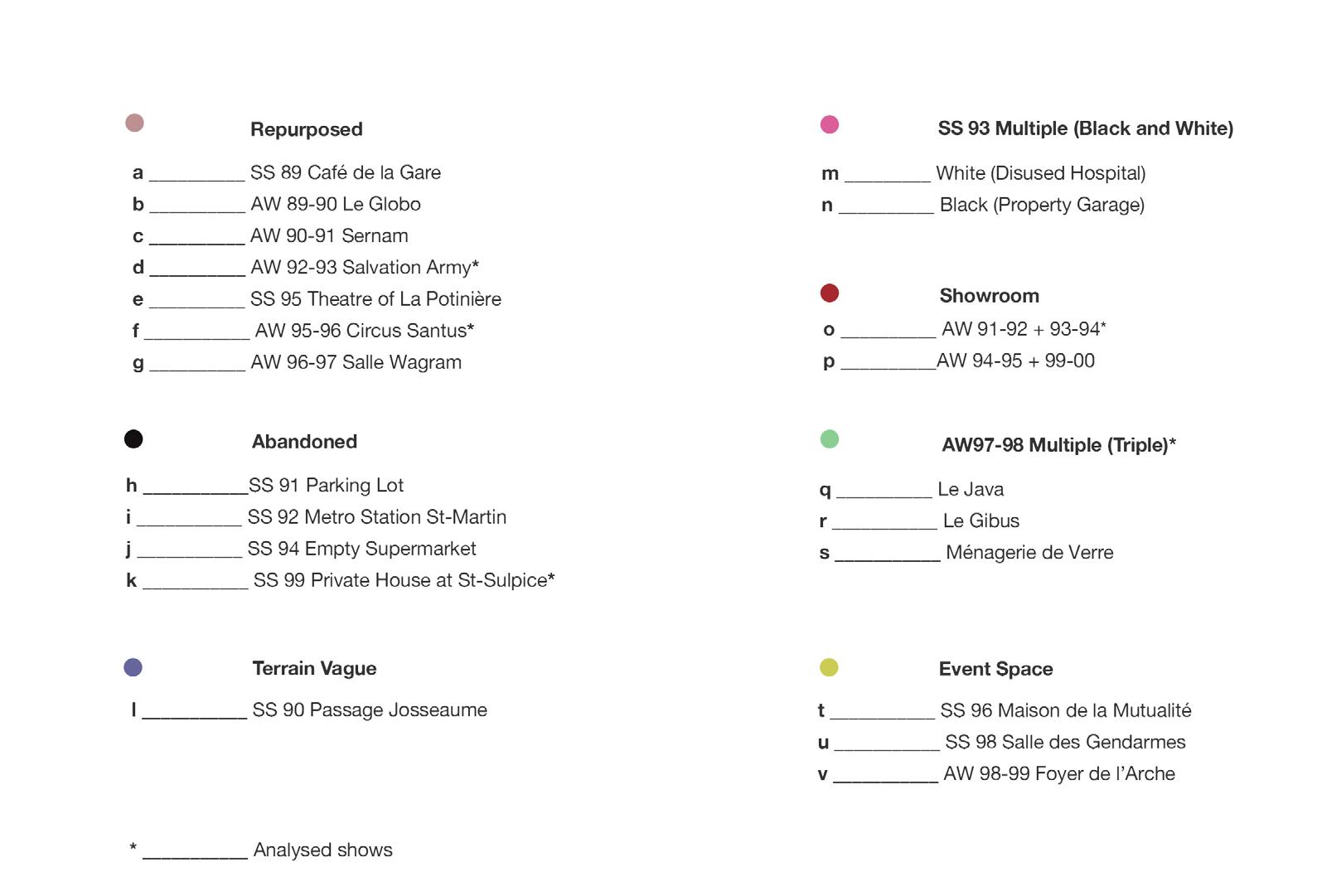

Next Passages examines how urban landscapes are shaped by overlapping temporalities — standards, images, ruins, and repairs — through which cities and structures are narrated and remade. The chapters track passages from past to next: Eleanor Moselle on Paris’s pneumatic clock network inscribing standard time via the sewer; Audrey Zhang on French Gothic Revival polychromy and the chromatic debates that recast medieval space and its futures; Kitty Alexander on Bristol’s St Mary-le-Port as palimpsest, where representation orchestrates vacancy, value, and redevelopment; Jazmine Simmons on imaginaries of a flooded London that render hydrological futures present and reshape public attachment to the Thames; Lora Lolev on Maison Martin Margiela’s off-centre runway shows as site-specific interventions rerouting attention, tenure, and meaning across urban margins. Permits, images, atmospheres, and affects operate as temporal instruments, choreographing new futures for built environments.

Across their differences, these essays speak to a common ethic — a recognition of the agencies that surround architectural design and history-making. With this in mind, the papers show how architectural history can be practiced not only as interpretation, but as care, collaboration, and repair. ∎

Editor’s note: Please be aware that some of the material in this publication deals with sensitive topics, including child sexual abuse.

Alongside this publication and accompanying exhibition, Setting the Table was presented as a research symposium at the Bartlett School of Architecture on 15th November 2025.

Navigating the Territory: The Church and Preventive Health Ship 14

Anna Garcia Molina

Structurally Difficult Heritage: Eric Gill’s Prospero & Ariel and the Problem with Architectural Integration 20

Eden Northcott

The Fashion and Textile Museum: A Piece of Mexico in London 26

Guillermo Gómez Tejera

The Power & The Glory: Nuclear War and the Protestant Ethic at the BT Tower 30

Joseph Williamson

Between Earth and Ink: Vernacular, Memory, and Utopia in Hassan Fathy’s Architectural Visualisations

Zaina Abou Seif

02 Behind the Glass

Invisibilized Domesticities: 2 Willow Road and the Embodiment of Housework

Claudia Vargas Franco Display vs Storage: Visibility, Accessibility and Transparency in Museums with Colonial Inheritances

Helga Beshiri

A Table of Intentions: Alison and Peter Smithson’s Exhibition of a Decade ‘54–‘64

Macarena González Carvajal

Google Street View and the Architectural Image: Rethinking Histories of Urban Representation

Mark Bessoudo

Testing the Waters: On Situated Ecologies and Sensing Radiological Architectures

Issy MacGregor

Architecture of Digital Waste: Hidden networks, materialities, and myths of data destruction

Qing Tang

Eco-Recursivity: Cybernetic Thinking in Eco-Machines of the New Alchemy Institute (1969-1991)

Ertuğ Erpek

68

74

80

Living with the Beast: The Impact of Trombe Wall Technology on Residential Life

Steven Schultz

04

86

When the Cathedrals were Painted: Decorative Mural Polychromy in the French Gothic Revival, 1840–1870

Audrey Zhang

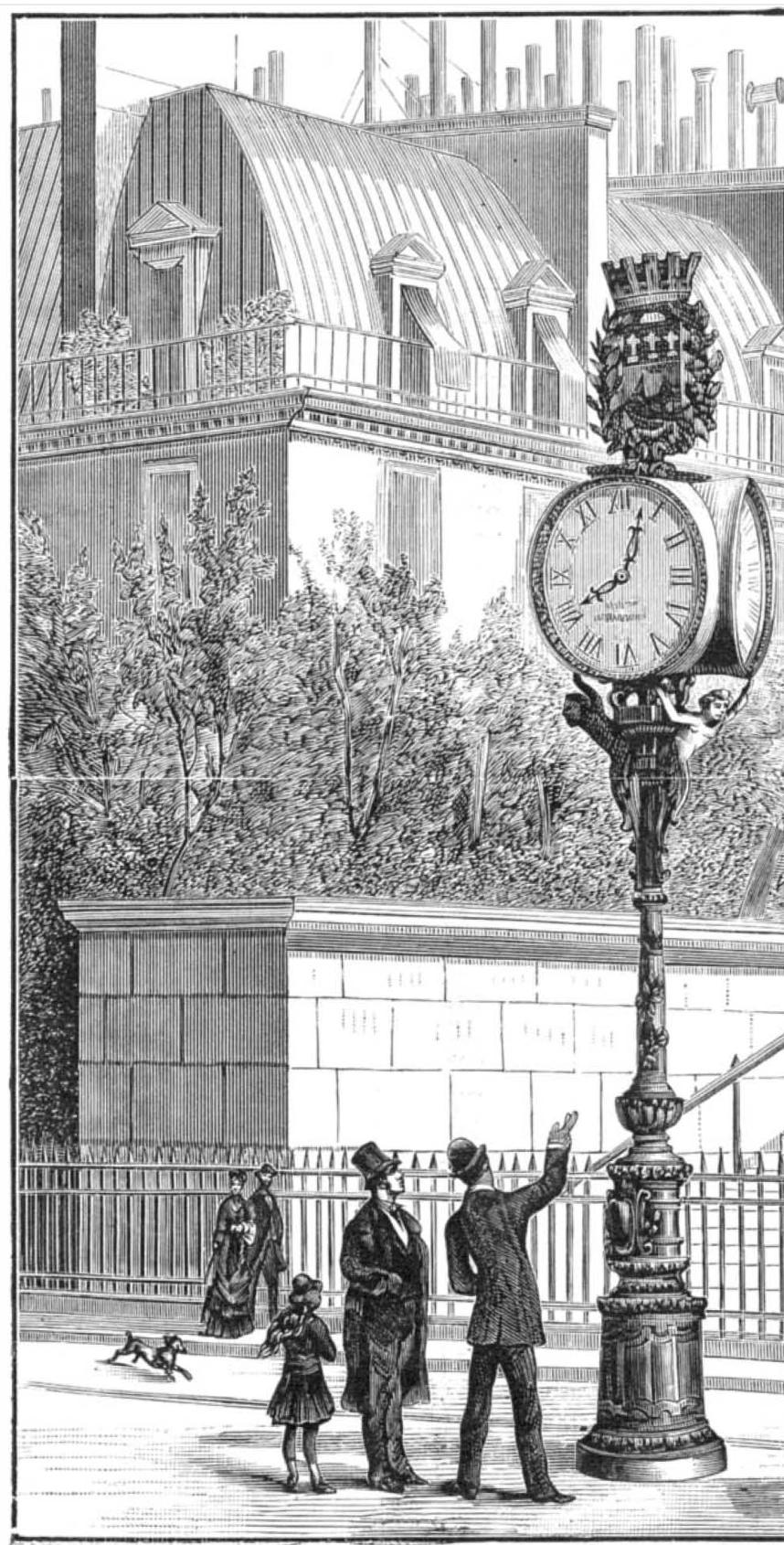

Networks of Time: Pneumatic clocks, standardised time, and underground infrastructure as expressions of modernity in 19th century Paris

Eleanor Moselle

Urban Water Imaginaries: London and its Connection to Waterlogged Realities and the Built Environment

Jazmine Simmons

The Spectacle of Decay: Ruin, Representation, and Renewal at St-Mary-le-Port, 1940–2025

Kitty Alexander

Crossing Boundaries: Subverting the Catwalk through Maison Martin Margiela (1988–1998)

Lora Lolev

94

100

106

110

116

06 Credits & Back Matter

Architecture as an active agent in shaping and contesting political, cultural, and ideological systems. These papers interrogate how built form and spatial strategies are implicated in colonial governance, postcolonial identity, religious symbolism, and geopolitical surveillance.

14 Navigating the Territory: The Church and Preventive Health Ship

Anna García Molina

20 Structurally Difficult Heritage: Eric Gill’s Prospero & Ariel and the Problem with Architectural Integration

Eden Northcott

26 The Fashion and Textile Museum: A Piece of Mexico in London

Guillermo Gómez Tejera

30 The Power & The Glory: Nuclear War and the Protestant Ethic at the BT Tower

Joseph Williamson

36 Between Earth and Ink: Vernacular, Memory, and Utopia in Hassan Fathy’s Architectural Visualisations

Zaina Abou Seif

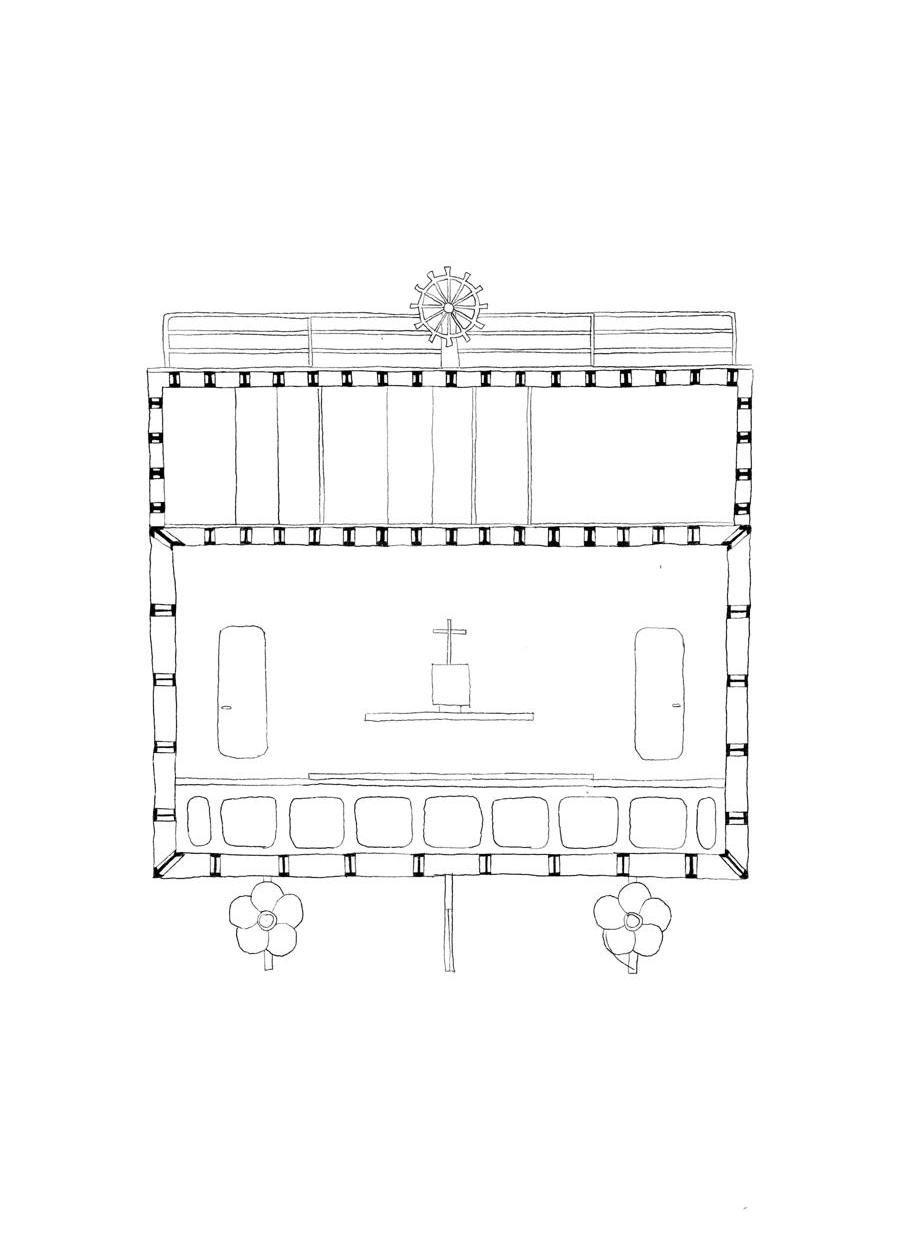

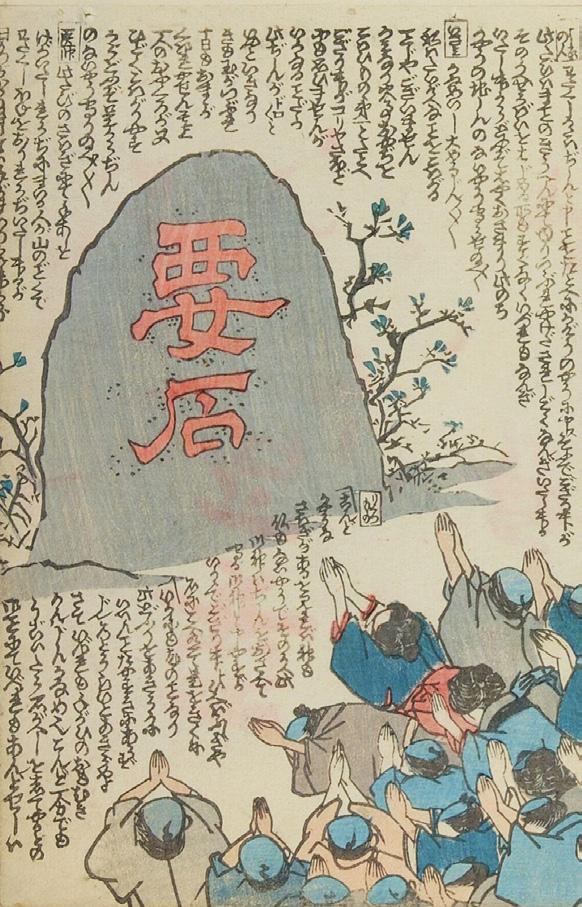

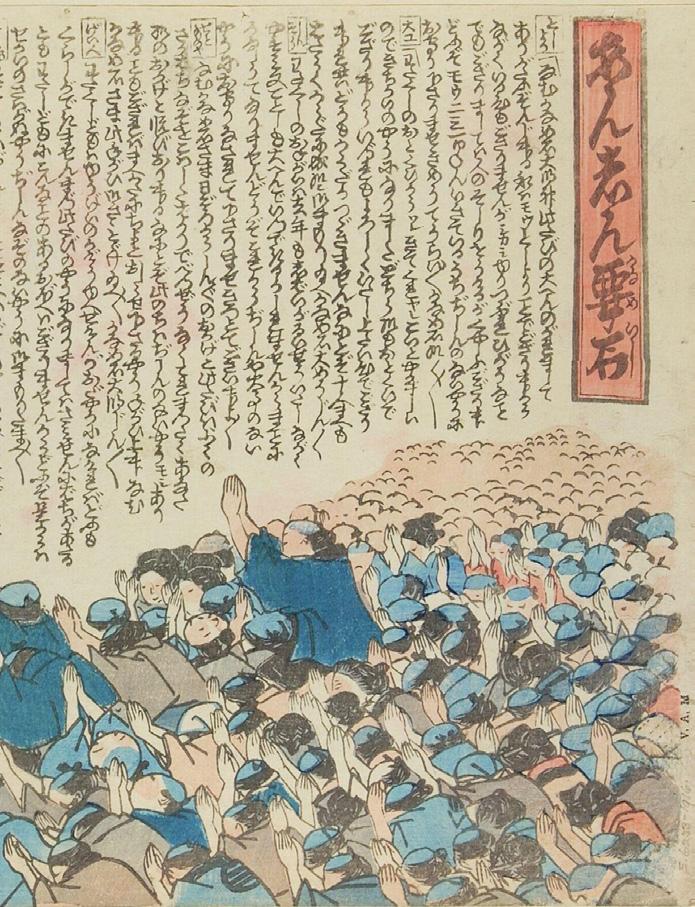

In 1948 the Argentinian modern architect Amancio Williams designed a ‘ship destined to carry out a social and moralising action in a region that was very neglected in those aspects.’1 The region, described by Williams as being ‘socially and morally abandoned’, was the Delta del Paraná, a vast isolated wetland landscape with numerous islands formed by the sediments of the Paraná River. To save this supposedly morally corrupt region, Williams designed the ‘Barco Iglesia y Sanidad Preventiva’, which translates as the ‘Church and Preventive Health Ship’. As the name suggests, his design merged a floating health clinic and church together in order to bring ‘culture’ to the inhabitants of the Delta. Although it was never built, the project was designed to civilise that impassable region, to bring the gospel and hygiene to those living there. It is a testament to the era in which it was conceived and a direct product of the legal, political and intellectual framework formed in 19th- and 20th-century Argentina to advocate for the control and regulation of the landscape and the bodies of those inhabiting the Delta del Paraná.

1 Description in ‘The Curriculum Vitae of Amancio Williams’, Amancio Williams fonds Collection Centre Canadien d’Architecture/ Canadian Centre for Architecture, Montréal; Don des enfants d’Amancio Williams/ Gift of the children of Amancio Williams. [Quotation translated by the author].

This thesis aims to critically examine the ‘Church and Preventive Health Ship’ as a cultural and architectural artefact. This involves analysing how it reflected – and participated in –ideologies of hygiene, morality, and territorial control within its context. The text will investigate how architectural typologies can become vehicles for state power, especially in those places framed as ‘uncivilised’ by the ruling elite.

However, this critical approach to a lesser-known, unbuilt project stands in contrast to the main currents in Williams’ scholarship. The literature on Amancio Williams reflects both fascination and unevenness, shaped by the difficulty of situating his work within established historiographical categories, since many of his projects remained virtually unchanged over decades and most were never built.

Many of these unbuilt projects remain overlooked, even marginalised, within the literature of Williams’ work. The project which forms the subject of this thesis, ‘The Church and Preventive Health Ship’, has never been studied in any detail. When mentioned, it is usually grouped into a series of works he produced while advising the Argentinian Ministry of Health, rather than analysed on its own terms. This thesis addresses that absence, situating the ship within the broader context of Williams’ thought and the intersections of religion, medicine, and infrastructure in mid-20th century Argentina. By combining historical, geographical, and theoretical approaches, it examines how architectural interventions like the ‘Church and Preventive Health Ship’ were not merely technical or aesthetic solutions, but instruments through which power, morality, and social order were enacted in the Delta del Paraná.

The questions that sparked and guided this thesis were fivefold. Why did the delta even need to be ‘cured’ by modernity? What role did architecture play in this quest? In what ways were physical and moral health understood as being related? How did the ‘Church and Preventive Health Ship’ reflect Argentinian ideologies of morality, hygiene, and civilisation? What architectural, religious, and medical discourses shaped its design,and how were these translated into spatial terms? While this thesis cannot claim to have the definitive

answers, it does suggest paths for thinking about how these factors might relate, intersect, and continue to be reinterpreted.

Because the ‘Church and Preventive Health Ship’ (1948) –as well as its successor project, the ‘Health Registry Ship’ (1949) – were never built, it means that the primary sources for this thesis had to be extracted from archival material. In the manner of Le Corbusier, Amancio Williams’ archive was meticulously recorded and manipulated by keeping hundreds of drawings, correspondence letters, and texts which describe his projects, exhibitions and publications. Precisely because Williams didn’t manage to build that much, it is why architects and academics regard his archive as the most important source to understand his work and ideas.2

Williams’ archive, which is now held at the Canadian Centre for Architecture in Montreal can be publicly accessed yet is in a location far distant from where the material was created. It was at the CCA, while conducting research for some exhibitions by that organisation, when I encountered the drawings for the ‘Church and Preventive Health Ship’. I was immediately struck by the strangeness of Williams’ concept. But as I delved deeper into the conditions that shaped this project, its unusual combination of church, clinic, and ship revealed an underlying logic. It was clearly an architectural attempt to merge moral, medical, and infrastructural programs within the unique geography of the Delta del Paraná. Williams’ drawings, although small and somewhat schematic, open a window into a rich intersection of historical, geographical, political, and philosophical processes.

This kind of study of unbuilt architecture demonstrates the value of thinking beyond construction. Even in the absence of physical manifestation, drawings allow us to trace how ideas, ambitions, and social imaginaries take form. In the case of Williams’ ship, it acts as a nexus where concepts of care, morality, territorialisation, and biopolitical control converge. By following these conceptual threads, we can understand not

2 Luis Müller, ‘El Archivo Como Obra Total: Amancio Williams y La Construcción de Su Memoria,’ Bitácora Arquitectura, no. 45 (December 2020): p. 52. Available at: https:// doi.org/10.22201/fa.14058901p.2020.45.77621.

only the conditions that produced the design, but also the broader mechanisms through which modernist architecture sought to intervene in marginal or unruly spaces. In this way, unbuilt works are not merely hypothetical: they are analytical tools that reveal the workings of architecture as a social and political practice.

The ‘Church and Preventive Health Ship’ should thus not be treated as just an architectural curiosity. It is a highly charged cultural artefact that reveals the ideological labour that architecture is called upon to perform when it sails into landscapes considered as wild, impure, or uncivilised. By placing the project within a wider framework of environmental control, religious mission, and biopolitical governance, the thesis offers new ways of thinking about architecture’s role in shaping and disciplining peripheral territories. ∎

The ship as an architectural drawing. Image by the author.

Editorial note: This article contains themes of sexual abuse and child abuse that readers may find distressing. Some of the original images from the dissertation have been omitted from this article.

For further discussion of considerations in the making and reproduction of such images, please consult David Roberts, ‘Making Images’, the first of the Practising Ethics guides to built environment research, available for download from the Bartlett’s Practising Ethics open-access website: www.practisingethics.org/practices.

Drawing on Sharon Macdonald’s concept of ‘difficult heritage’1, this paper explores how Eric Gill’s Prospero and Ariel (1931–32), at BBC Broadcasting House, represents a new category of contested heritage: structurally difficult heritage. Unlike standalone contested monuments that may be removed when they become morally problematic, structurally difficult heritage is integrated into protected building fabric; therefore, removal is complex and damaging to the integrity of the listed building it adorns. Commanding one of London’s most prominent apex views at Regent Street’s termination, the curved BBC frontage forces Prospero and Ariel upon a compulsory public audience. This case questions whether some sculptures are ultimately too problematic to impose as public art as part of the everyday urban environment, especially if, as figural depictions, they are enmeshed with unethical, immoral, and therefore hurtful representations.

The sculpture has been controversial since its creation, experiencing a reduction in the size of

1 Sharon Macdonald, Difficult Heritage: Negotiating the Nazi Past in Nuremberg and Beyond (London and New York: Routledge, 2009).

the boy’s genitalia at the BBC’s request2 and vitriol in Parliament as ‘objectionable to public morals and decency’3. Yet this cannot be dismissed as Victorian prudishness. What distinguishes Gill’s Ariel from ubiquitous nude cherubic decoration on London’s buildings is that it abandons established artistic conventions that made such imagery morally acceptable. In Shakespeare’s play, Ariel’s gender is deliberately ambiguous, allowing for his relationship with Prospero to remain asexual. Yet Gill clearly abandoned this ambiguity for an explicitly male child in a state of undress. His genitalia prominent, his form lean — a boy old enough to be conscious of his own nudity and vulnerability, positioned in intimate dependence with an adult man whose long robes emphasise his nakedness. The problem then was not the unclothed boy, but the inappropriate power dynamic that formed the context for this juxtaposition.

Since Fiona MacCarthy’s 1989 biography exposed Gill’s sexual abuse of his sisters, daughters and family dog4, there have been calls to remove the statue. However, its architectural integration into the Grade II* Listed building complicates matters. The sculpture was carved onsite in the same Portland stone as the building’s facade, in a specifically designated niche. As Gill himself theorised, architectural sculpture is not merely decorative but integral to the building itself5. To remove the sculpture risks violating Historic England’s listing protection, potentially compromising the architectural integrity of one of Britain’s most significant Art Deco buildings. But to leave it unprotected risks further vandalism. David Chick’s

2 John Stewart, British Architectural Sculpture (1851-1951), Lund Humphries (2024), p. 172.

3 Astragal, “Notes & Topics: The Fig-Leaf Mind,” The Architects’ Journal (Archive: 1929–2005) 77 (March 29, 1933), p. 418.

4 Fiona MacCarthy, Eric Gill, (London: Faber & Faber).

5 Eric Gill, “Prospero and Ariel,” The Listener, March 15, 1933, p. 397. The Listener Historical Archive, 1929-1991

attacks in 2022 and 2023 revealed that some heritage has become so contested that it requires physical protection from the public it was intended to serve. Throughout this controversy, the BBC has firmly maintained that separation between Gill and his work is both possible and necessary.

The convergence of revelations about Gill’s crimes with the BBC’s own institutional failures — Jimmy Savile, Rolf Harris, and accusations against founding Director-General Lord Reith — fundamentally altered how the sculpture could be perceived. Within this context, the sculpture’s content has become profoundly inappropriate. Separation is now impossible. What was once an architectural ornament and metaphor for broadcasting has been exposed as a monument to institutional failure that enabled such crimes to flourish.

Many support the BBC’s position, however, we must forgo this selective blindness — Gill’s work cannot be viewed as wholly discrete from who he was and what he did. MacCarthy posits that the true subjects of Ariel and Prospero are not the Shakespearean characters but in fact Gill and his adopted son, Gordian6. Throughout his work, Gill systematically inserted himself into sacred father-son iconography, conflating his earthly paternal role with divine meaning. When we view the sculpture through this biographical lens and Gill’s documented crimes against children, it becomes increasingly difficult to justify continuing to celebrate this work simply as a mythological allegory for the BBC.

In 2025, the BBC unveiled its response: a restored sculpture enclosed in what clumsily resembles a museum vitrine in the sky. The BBC paradoxically achieves the very separation from its architecture it claimed to want to avoid, transforming it into an artefact divorced from its context. The steelwork plate slices the globe awkwardly off-centre, severing the conceptual foundation from which Ariel is to be released into the world. The sculpture can no longer be read through Gill’s definition of architectural sculpture, as ‘a flowering…of the very stones of which the

6 Fiona MacCarthy, “The Word Made Flesh.” RSA Journal 141, no. 5436 (1993): pp. 14345.

building is made’7. Instead, this continuity is interrupted by the vitrine. By separating the sculpture from the public, rendering it untouchable and separate from the architecture, the acrylic barrier inadvertently deploys the visual language of museumification that amplifies rather than manages its cultural legitimacy.

The BBC’s attempt at contextualisation fails to protect the public from the sculpture. The QR code mounted within the ground-floor window feels like an afterthought. Buried six paragraphs in, the BBC has only this to say on the sculpture’s creator: ‘revelations about Gill’s private life in a 1980s biography created a backlash against him; and while the BBC in no way condones his abusive behaviour, it draws a line between his life and his artistic creations’8. The words are careful, concise, and diplomatically evasive. The QR code is performative and meaningless while enabling the BBC to claim engagement while keeping Gill’s crimes obscured.

The vitrine in the sky can satisfy no one — it neither preserves the integrity of the imagery nor adequately addresses concerns about the artist’s motivations. Removal would represent a new path forward for the BBC. An empty niche would represent the BBC’s transparency, humility, and accountability. There would be a direct message in the emptiness — one that aligns with the BBC’s stated commitment to truth-telling.

This case illuminates the inadequacies of the government’s ‘retain and explain’ policy, suggesting that heritage management must evolve from prioritising historical over contemporary values and should never outweigh public welfare. Arguably, an empty niche on the front facade of Broadcasting House would become a more powerful symbol for the BBC than Gill’s sculpture ever was. This would not constitute heritage destruction, but heritage evolution — demonstrating that our relationship with the past can and must evolve to serve contemporary society. ∎

7 Gill, The Listener, p. 397.

8 British Broadcasting Corporation, History of the BBC - Broadcasting House, BBC, QR code at Broadcasting House.

This dissertation examines the Fashion and Textile Museum (FTM) in Bermondsey, designed by Mexican architect Ricardo Legorreta for the British designer Dame Zandra Rhodes, as a case study of architectural transculturation. It explores how Mexican architectural identity is expressed abroad and how cultural exchange between Mexico and London becomes material through architecture. The argument proposed is that the museum embodies a reciprocal process of transformation, where Mexican modernism and British urban culture meet and reshape one another.

The research began with a personal encounter in 2018, when I first came across the building’s bright orange and pink façade set among Bermondsey’s brick warehouses. Its colours and geometry felt instantly familiar, echoing the architecture I had grown up with in Mexico. Yet, within London’s context, it also appeared foreign. This dual feeling — of recognition and estrangement — became the starting point for the question that guided this research: what does it mean for a building to be ‘Mexican’ when it stands in the middle of London?

The study situates the museum within the broader history of Mexican modernism, tracing its development from post-revolutionary nationalism to its international projection through figures such as José Villagrán García, Luis Barragán, and Ricardo Legorreta. Drawing on Celia Esther

Arredondo’s The Making of Modern Mexican Architecture (2023), it challenges frameworks of acculturation that view non-Western architecture as derivative, instead adopting Fernando Ortiz’s notion of transculturation — a dynamic and reciprocal process of exchange. This perspective reframes Mexican modernism as an active participant in global architectural discourse rather than a regional response to Western influence.

To expand on this framework, the dissertation draws on Mary Louise Pratt’s concept of the contact zone, where cultures meet and negotiate, and Homi Bhabha’s theories of hybridity and translation, which describe how cultural forms change through encounter. Together, these ideas allow the museum to be read as both an object and a process of cultural negotiation, where Mexican and British identities redefine one another.

The methodology combines historical and visual research with site observation and interviews with Zandra Rhodes and Víctor Legorreta. These sources ground the theoretical discussion in practice, revealing how transculturation occurs not only through ideas but through everyday exchanges between architect, client, and local collaborators. My position as a Mexican architect living and working in the UK also shaped the research approach, allowing me to reflect on the museum through a dual lens — of both origin and reception.

The first part of the dissertation, From Mexico to London, traces how Mexican modernism developed as a hybrid formation after the Revolution of 1910. Architects such as Villagrán García and Barragán combined European modernism with local traditions, light, and materiality to form a modern language grounded in emotion and place. Legorreta continued this lineage through what he termed ‘emotional architecture’ — an approach defined by geometry, light, and vivid colour. His work carried forward the spirit of Mexican modernism while extending it internationally.

The dissertation then turns to Bermondsey, situating the museum within its post-industrial regeneration. Once defined by warehouses and food processing, Bermondsey underwent a decline before its transformation in the 1990s into a creative district. Within this context, the FTM played a significant role in

reshaping Bermondsey Street as a cultural hub, embodying the shift from industry to design-led redevelopment.

The second part, In London, from Mexico, focuses on the building itself. Located at 79–83 Bermondsey Street, the museum integrates Rhodes’s home and studio with exhibition and educational spaces. Its geometry, light, and use of pink, yellow, and orange express a shared language between Rhodes and Legorreta. For Legorreta, colour reflected Mexican light and tradition; for Rhodes, it was an extension of her textile practice. Their collaboration created an architecture that merges two creative identities and resists being attributed to a single source.

Working alongside local architect Alan Camp, Legorreta adapted his design to London’s planning requirements, demonstrating transculturation in practice. The resulting building is neither a direct export of Mexican modernism nor an imitation of London’s style, but something in between — a hybrid that carries traces of both. As Víctor Legorreta described, it is ‘Mexican, but also Zandra Rhodes, and also London’.

The museum thus operates on multiple levels of exchange: between Mexico and Britain, between architecture and fashion, and between regeneration and identity. Rather than a static object, it functions as a contact zone where cultural meanings are negotiated through form, colour, and collaboration.

The dissertation concludes that the FTM embodies architecture as a living form of cultural translation. Mexican modernism, itself a product of hybrid influences, extends outward and finds new meaning in London’s context. The building challenges linear models of cultural influence, revealing instead a two-way process of transformation. The FTM, at once Mexican and London, demonstrates that architecture is not a fixed expression of identity but a continual act of translation, shaped by movement, memory, and exchange.

The BT Tower was originally built as a civildefence asset, part of a ‘Backbone’ microwave network designed to provide telecommunications resilience in the event of nuclear attack. Its architect, Eric Bedford, said of the Tower, ‘it was built to last, bombers or not’.1 The building’s design follows a template: ‘Chilterns-type’, which comprises several unorthodox design choices that safeguard against nuclear attack such as, a cylindrical concrete core, perspex screening around the dishes and reinforcement at the tower’s base (fig. 1). The Chilterns-type comprises a cylindrical concrete core, or ‘chimney’, with dishes and aerials attached. In the event of nuclear attack, dishes and aerials would be destroyed but their replacement would ensure quick

1 Tavia Swain, ‘How Did the BT Tower Achieve Icon Status and Has This Been Maintained Into the 21st Century?’ (Unpublished, 2023), p. 25.

re-connection to wireless national communication.2 Despite early considerations, the BT Tower in Birmingham chose to avoid the type two years later in favour of a rectangular shaft.3 This development would imply that concern about the nuclear bomb was waning by then, but in fact, it was more a case that any hope of survival was waning — and that while in 1961 the A-bomb was seen as a counterable threat, by 1963, with the emergence of the much more devastating H-bomb, all hope had been lost for any sort of telecommunications-based civil defence in the aftermath of a strike.

Beatriz Colomina states in Privacy and Publicity that, ‘The modern media are war technology’:4 As an ambassador for an age of modern media, the BT Tower itself is war technology, not just a tool of defence, but also offence. Virilio equated propagation of ‘jet-sets and instant-information banks’ to a ‘whole social illusion subordinated to the strategy of the cold war’.5 The Tower’s revolving restaurant is a ‘Fun Palace’ and a distraction from the inner workings of the tower — a diversion outwards. It is noted in the banned 1966 film The War Game about the aftermath of a nuclear bomb, that by 1966, ‘silence had descended’ around nuclear war despite the fact that warheads had doubled in the preceding five years.6 This silence is a deliberate strategy of pacification, for the threat of nuclear holocaust was increasing at a tremendous rate.

Harold Wilson, Tony Benn, Harold Macmillan and Geoffrey Rippon, engineers of the BT Tower, are equatable to the ‘priests of civilisation’, in that the engineers are those who preach and practice the doctrine of modernity most fervently.7 Benn, a devout Christian, was labelled ‘ministering priest or maintenance engineer to the great god Technology’.8 Despite the fact that

2 Peter Laurie, Beneath the City Streets: The Secret Plans to Defend the State, (Granada, 1979), p. 247.

3 B. L. G. Hanman and N. D. Smith, ‘Birmingham Radio Tower’, The Post Office Electrical Engineers Journal, 58.3 (1963).

4 Beatriz Colomina, Privacy and Publicity : Modern Architecture as Mass Media (MIT Press, 1996), p. 156.

5 Paul Virilio, Speed and Politics, trans. by Marc Polizzotti (Semiotexte, 1986), p. 136.

6 The War Game, dir. by Peter Watkins (BBC, 1966).

7 Virilio, Speed and Politics, p. 41.

8 Bernard Levin, The Pendulum Years: Britain in the Sixties (Jonathan Cape, 1970), p. 180.

the tower was largely complete by the time that the Labour government came to power in 1964, it has become a symbol of Wilson’s ‘White Heat’ policy.9 (fig. 2) Its ‘engineers’ became a revolving cast, devoted to a form of progress dominated by control and paranoia. Virilio mentions, ‘the English engineers ended up significantly reducing their motto to UBIQUE… “everywhere.” This means the universe redistributed by the military engineers, the earth “communicating” like a single glacis, as the infra structure of a future battlefield’.

10 Mass media is itself co-opted as a civil defence asset,

9 Christopher T. Goldie, ‘“Radio Campanile”: Sixties Modernity, the Post Office Tower and Public Space’, Journal of Design History, 24.3 (2011), p. 209.

10 Virilio, Speed and Politics, p. 74.

Figure 2. Author’s Own, ‘Forged in the White Heat of Scientific Revolution’, 2025, Photograph.

‘bread and circus’ became ‘television and revolving restaurants’. Telecommunications are not only the ‘infra structure of a future battlefield’, they are the battlefield itself.

The bomb is political, ‘not because of an explosion that should never happen, but because it is the ultimate form of military surveillance’.11 The threat of the bomb is advantageous to the government, as it allows for creation of ‘war technology’ that consolidates control of their populace. This functions in the same way that religious groups use threat and fear of the Final Judgement and the Apocalypse as leverage in controlling their adherents. The possibility of the bomb is what enabled the government to encroach on telecommunications. This legitimised further encroachment during later events, i.e. the War on Terror and the War on Drugs; framed as crusades against threats to secular civilisation, but rooted in Christian eschatology. Nuclear war portended an alternative apocalypse without redemption or final judgement; pacification was no longer about a promise of a celestial future but about distraction, for which telecommunications could become a primary enabler. In this way, the BT Tower was a flagship for a new way of seeing the end of the world.

After the devastating paranoia of nuclear war; a formlessness started to emerge, a messianic hope for another kind of invisible force to rescue us. ‘It [was] shown that we cannot now change the world any longer, anything that might tend to prove the existence of another form of reality will be welcomed’.12 It became necessary to find a new way to ‘mobilise, cumulate and recombine the world’; and in this way, ‘telecommunications, not only as space and time transcending technologies, but as technological networks within which new forms of human interaction, control and organisation can actually be constructed’ became the replacement for what religion had provided before.13 Telecommunications, and the networks upon which they are built, were the first truly invisible source of power outside of

11 Ibid, p. 119.

12 Umberto Eco, ‘Signs of the Times’, in Conversations about the End of Time, trans. by Ian Maclean and Roger Pearson (Fromm International, 2001), p. 179.

13 Stephen Graham and Simon Marvin, Telecommunications and the City (Routledge, 1996), p. 54.

religion, relying on material receptacles (the antennae, aerial, dish) while dispersing an intangible presence into the lives of all who interact with it, just as the church did before.

For Teilhard de Chardin, ‘spirit looks very much like energetic information. Spirit is software in action’, a ‘Network [that] is physical but not material’.14 In this sense, the BT Tower becomes a pure material representation of the energetic information (spirit) that flows through it; conversations whizz through it, lives are broadcasted, and it enables a disembodiment from the material source of these exertions. It facilitates an invisible reality rather than embodying that reality, and holds the disembodied ‘souls’ of the people whose voices and likenesses it transmits — without any tangible physical or audible presence.

In this way, the ‘place’ of the Tower becomes wherever the network reaches. As the home becomes part of this immaterial network, it is then enabled to fulfil a break in temporal duration. The tower becomes redundant as a typology as technology surpasses it, and those who participate in this extended network become ‘cut loose from the sociality of urban life, separated from the world by the pixilated screen’.15 For someone like Benn — instrumental in the push for technology and in agreement with Gerrard Winstanley that God is ‘reason’16 — this rational application of the irrational perhaps aligns with Marx and Kierkegaard’s notion that ‘experience [...] forms the core of religious life’, and that via spiritual ascendency, ‘all confront themselves and each other on a single plane of being’.17 With the telecommunications network, an invisible Church, and an invisible elect, was created.

14 Eric Steinhart, ‘Teilhard de Chardin and Transhumanism’, Journal of Evolution and Technology, 20.1 (2008), p. 17.

15 Stephen Graham and Simon Marvin, Splintering Urbanism : Networked Infrastructures, Technological Mobilities and the Urban Condition (Routledge, 2001), p. 247.

16 Tony Benn, The Best of Benn, ed. by Ruth Winstone (Hutchinson, 2014), p. 123.

17 Marshall Berman, All That Is Solid Melts into Air: The Experience of Modernity (Verso, 1993), p. 115.

When historian Leïla el-Wakil stood before a room of Hassan Fathy’s closest admirers at the Bibliotheca Alexandrina in 2007, she began with an apology as she had dared to call him ‘unknown.’1 To those who had shared his company, the phrase seemed absurd, and even offensive. Outside that circle, perhaps her words carried a truth. Fathy remains a paradox of recognition, mythologised as a visionary figure through architectural fragments while seldom grasped in the totality of his practice.

Born in Alexandria in 1900 and passing in Cairo in 1989, Fathy remains Egypt’s most influential architect, celebrated for his advocacy of rural mudbrick construction, community-based design, and his ethical reconciliation of vernacular knowledge with modern socio-climactic imperatives. His canonical 1940s New Gourna Village garnered him international attention, rising to recognition as the architect of the poor. Whilst a fitting moniker, this paper pushes beyond the material realm of his built work to interpret Fathy’s vast — and overlooked — oeuvre of speculative drawings, gouache paintings, and fictional stories as active, autonomous components of the artist-architect’s philosophical trajectory. Attending to the interplay of form and narrative, I contend that the futurist

1 Leïla el-Wakil, ‘The Unknown Hassan Fathy,’ paper presented at the seminar Hassan Fathy and His Legacy, Bibliotheca Alexandrina, October 25, 2007, p. 1.

sensibilities often associated with his mature architecture were already present in these multimodal early midcentury explorations.

Fathy’s career spanned nearly the entire twentiethcentury, unfolding in tandem with Egypt’s own turbulent transformations. As both witness to and agent within the nation’s shifting political landscape, he operated amid the lingering imprint of successive colonial regimes, whose architectural legacies threatened to eclipse local typologies. Caught between the instability of Europeanisation and arabité, his work registers the psychic and cultural tension of a country negotiating its own modernity.

Rather than defining him through essentialist labels, I locate Fathy’s personal and polymathic dualities within the broader nahda, or the Arab Awakening, a period marked by postcolonial critique and creative renewal. Within this intellectual climate, Fathy translated the crisis of national identity into an idealistic architectural vision that sought to reclaim cultural memory through pieces of the past, projecting them into possible futures. Drawing on the vernacular ‘Arab house’ as both model and metaphor for his artworks and literature, he traced a lineage extending from Pharaonic precedents and Nubian huts, to Mamluk and Fatimid mosques and dwellings — forms he studied intimately through site visits to the Citadel, Aswan, and Luxor. These geographic encounters informed his lifelong project of reactivating indigenous knowledge systems as a radical proposition for envisioning modernity otherwise. I propose that Fathy’s utopian impulse to craft an ‘ideal’ world thus functions as a retrieval of a homeland of form — a territory that exists at once as memory and aspiration. When we embrace place as a socially constructed phenomenon achievable through imaginative engagement, imagination itself becomes constitutive of collective belonging and resistance.

Despite his Beaux-Arts training in a French-inflected cosmopolitan Cairo, Fathy’s outlook was transformed

Top Transcription of Hassan Fathy’s reflections on Nubian artistry and the inseparable bond between tradition, community, and modernity. He celebrates the psychological freedom found in building ‘with what is at hand,’ rejecting imported forms in favour of an architecture rooted in self-knowledge and place. For him, what is ‘Pharaonic’ or ‘Arab’ is not past, but modern — an affirmation that ‘they did not need anything that wasn’t already theirs.’ Image by the author.

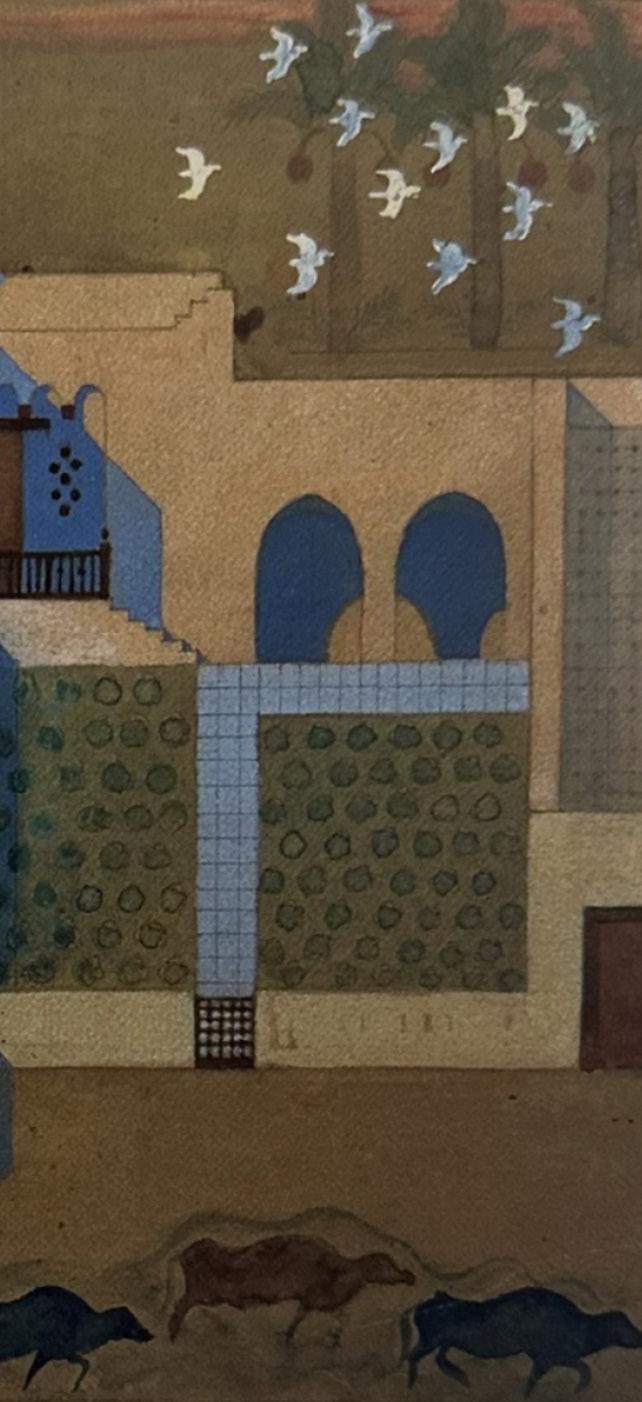

Bottom Hassan Fathy, Abd al-Razik Eastern Rest House, gouache, 29.2 × 27 cm, 1943. Reproduced from Archnet’s Architect’s Archive: Hassan Fathy, © Aga Khan Trust for Culture.

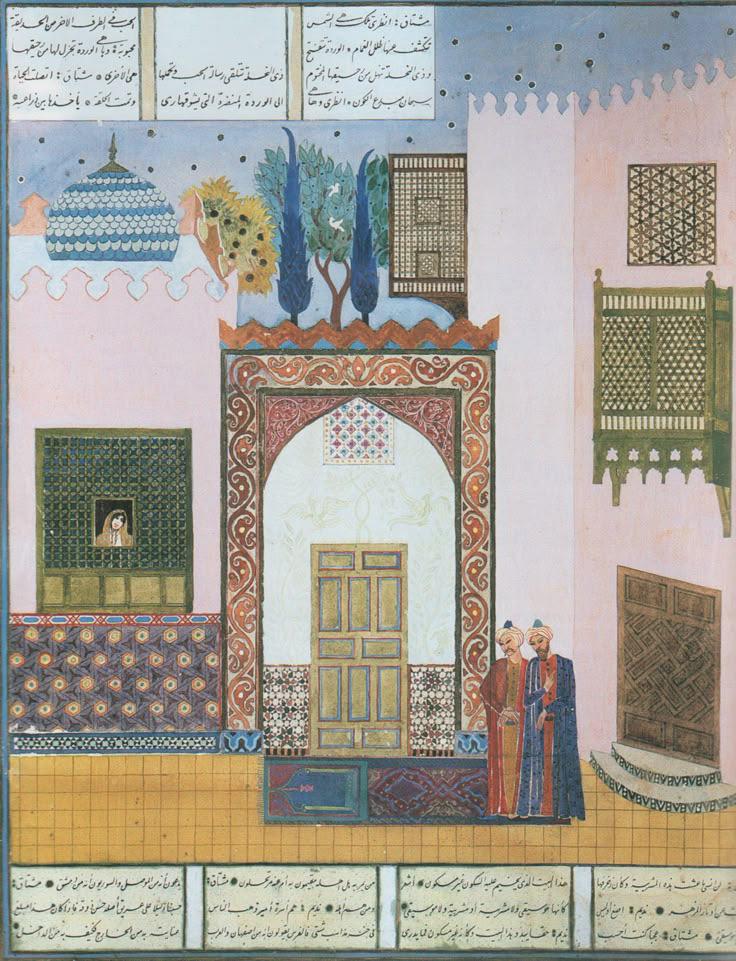

through a direct pedagogical engagement with Egypt’s rural countryside, where he encountered historic, local modes of spatial knowledge that reshaped his understanding of architecture’s social purpose. His paintings, in particular, reveal a sustained resolution between Western orthographic conventions and indigenous visual epistemologies. Drawing on Eastern techniques — such as the ornamental marginalia of miniature painting or various perspectival points within a single frame — Fathy employed a syncretic strategy that reimagined drawing as a catalyst for contemporary architectural representation. These experiments channeled his inherited methods toward inward reflection, and consequently, two mutually generative principles thread across his visual and literary work: the collapse of temporality and the multiplicity of experiential seeing. By engaging with his archival artworks as sites of theoretical production in their own right, this study expands the notion of architectural visuality, questioning what forms of making and representing are permitted to register within the discipline’s canon.

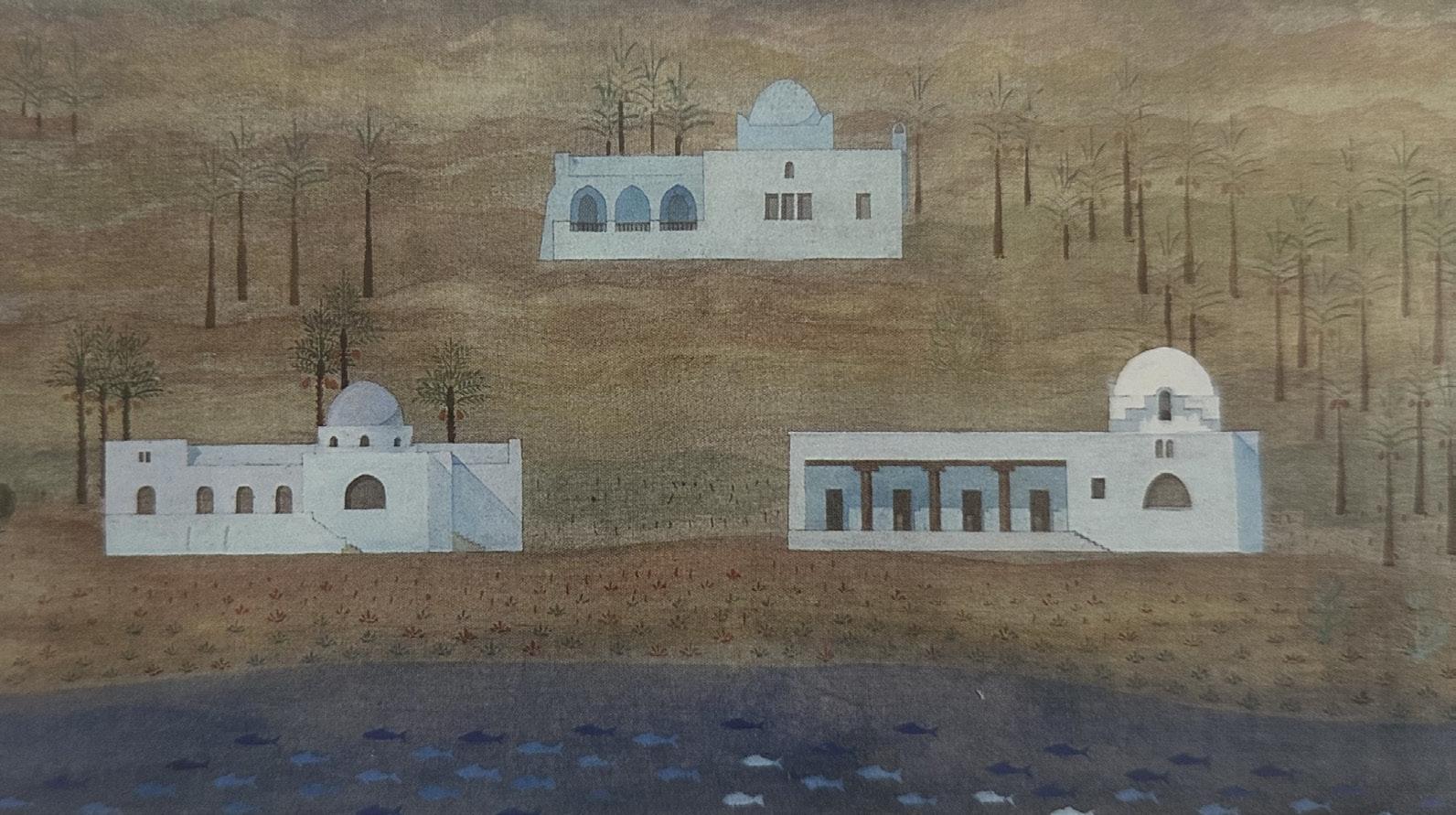

At times, Fathy’s compositions echo the symbolic precision of Pharaonic wall paintings or the rhythmic hieroglyphic inscription of form; at others, they adopt a restrained, notational clarity that allows affect to emerge through minimal means. His pictorial language is marked by a pared-down mise-en-scène, in which a few symbolically charged motifs — including botanical taxonomies, rural figures at work, cattle — enliven the central architecture whilst acting as its interlocutors. Their presence situates the manmade environment within a network of traditional sociospatial practices and natural life. Central to this ecology is the fellah, the peasant farmer, whom Fathy casts as an active, central subject sustaining reciprocity between architecture and landscape. He therefore reclaims the vernacular gaze on indigenous terms, constructing an alternate vision of the Egyptian countryside as a site of cultural continuity, quiet resistance to Western urbanism, and ethical reflection for the architect-intellectual.

These non-practical, unbuilt works operate as atmospheric constructions — sites where perception and emotion are jointly produced, rendering the act of seeing inseparable from the act of sensing. The value of visual affect, here, becomes particularly generative. His paintings indulge in the expressive capacities of

hue, often through washes of ochre, pistachio, and rust arranged around the luminous whiteness of a vernacular form, translating the fleeting play of daylight into permanent pigment. Indeed, the colour-consciousness of Fathy’s painterly imagination stands parallel to the monochromatic paleness of his realised buildings, which accept the pragmatic restraint of whitewashed adobe. However, I argue that they become participants, receptive canvases, in the daily rhythm of light and shadow, constantly reimagining themselves through their relationship with time blushing rose at sunset and bleaching to near-translucence under the midday sun. Together, these modes construct a dialectic between ephemerality and solidity, material necessity and chromatic plenitude, situating colour as both a sensory and philosophical tool to conjure the tenderness and temporality of place.

Across his repertoire runs a sensibility both devotional and rigorously mathematical, where drawing becomes a meditative, almost sacred, engagement with space and community. Each line ritually structures relations of attachment, exclusion, and belonging. In Fathy’s hands, heritage and utopia are not fixed endpoints, but surfaces to be continually reassembled. Ultimately, his paradigmatic legacy suggests that spatial imagination is a sociopolitical act — a means of claiming agency over how place and identity are constructed.

Left Hassan Fathy, Utopian Landscape series, private farmhouses overlooking Lake Qarun, gouache, 101 × 49.2 cm, 1937. Reproduced from Salma Samar Damluji and Viola Bertini’s Hassan Fathy: Earth & Utopia (London: Laurence King Publishing, 2018), p. 95. © Aga Khan Trust for Culture.

Top

Hassan Fathy, Utopian Landscape series, gouache, 53 × 42 cm, 1937. Reproduced from Damluji and Bertini’s Hassan Fathy: Earth & Utopia, p. 96. © Aga Khan Trust for Culture.

Bottom

Gouache and watercolour on paper depicting Fathy’s set for his unperformed play The Story of the Mashrabiyya (1942). The characters exchange dialogue about the qualities of the lattice screen between them, visible in the surrounding calligraphic portals. Reproduced from Damluji and Bertini’s Hassan Fathy: Earth & Utopia, p. 137. © Aga Khan Trust for Culture.

Bringing visibility to the concealed spaces, practices, and infrastructures that sustain cultural and architectural systems. From service quarters to museum repositories, and the digital streetlevel view, these studies examine the overlooked architectures of work, storage, and documentation.

44 Invisibilized Domesticities: 2 Willow Road and the Embodiment of Housework

Claudia Vargas Franco

50 Display vs Storage: Visibility, Accessibility and Transparency in Museums with Colonial Inheritances

Helga Beshiri

56 A Table of Intentions: Alison and Peter Smithson’s Exhibition of a Decade ‘54–‘64

Macarena González Carvajal

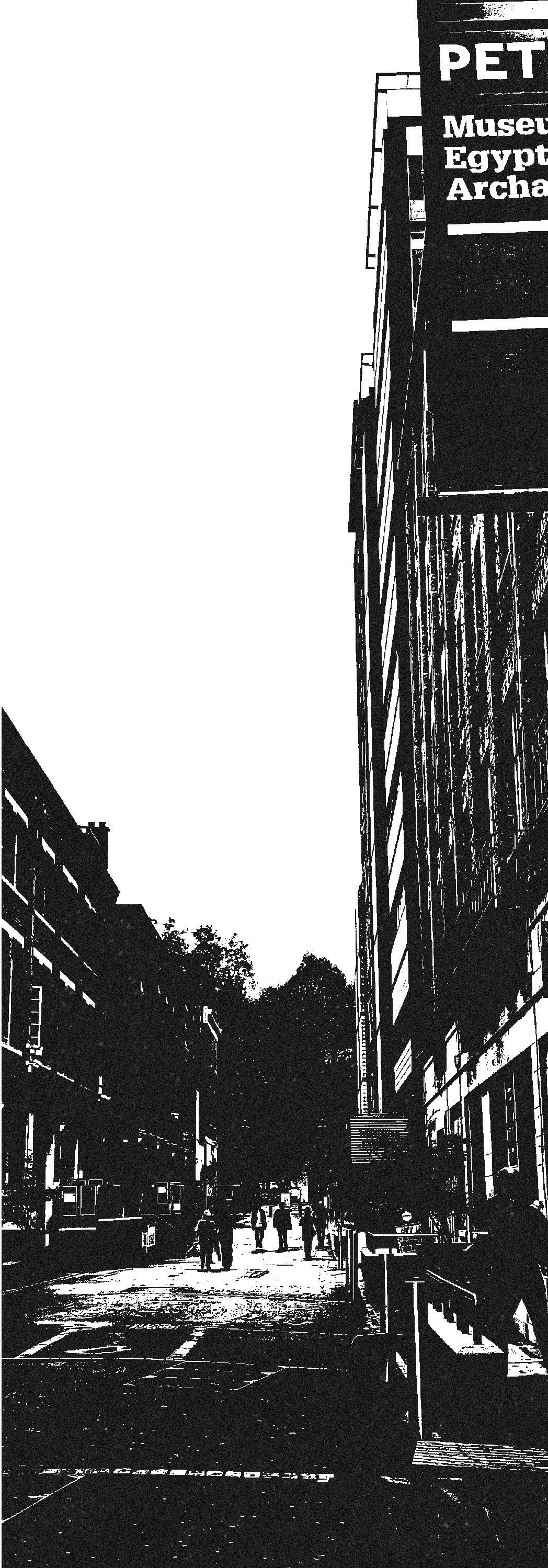

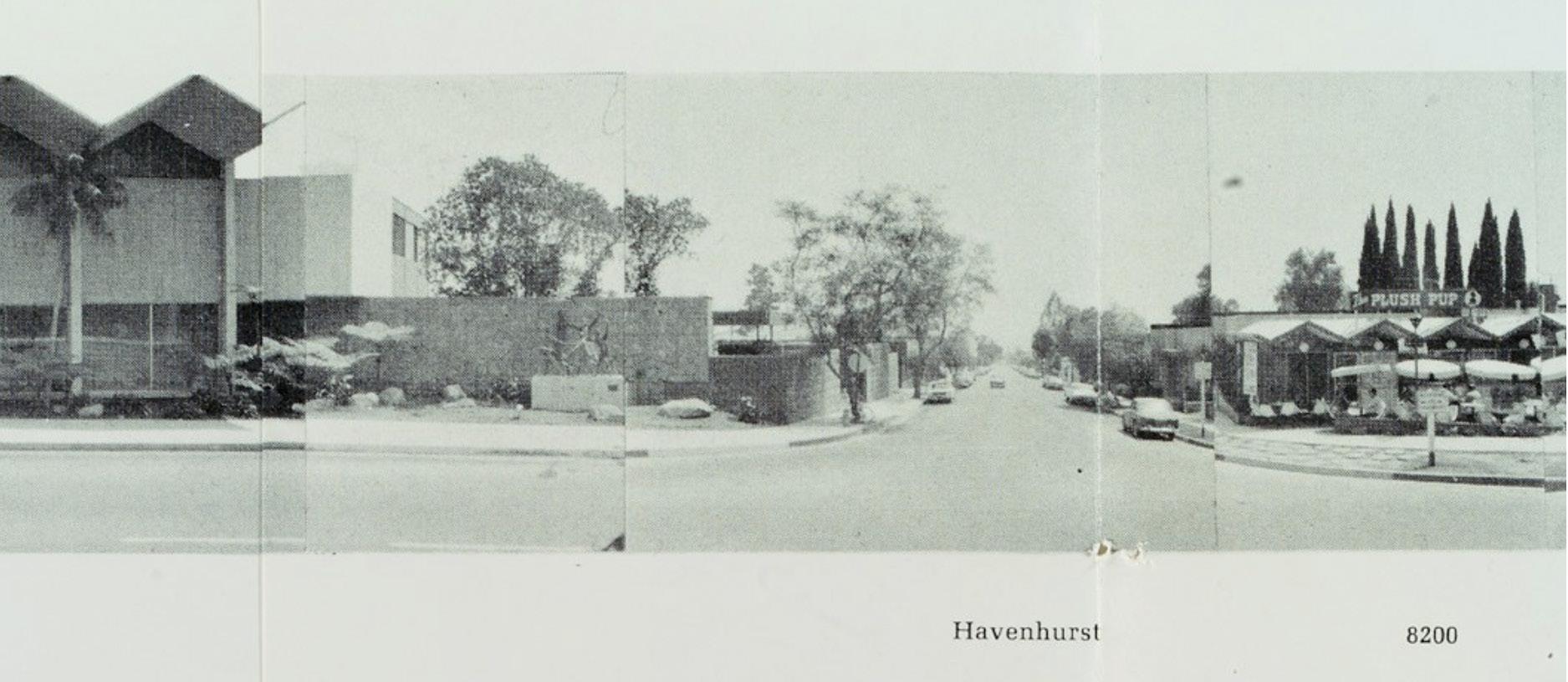

60 Google Street View and the Architectural Image: Rethinking Histories of Urban Representation

Mark Bessoudo

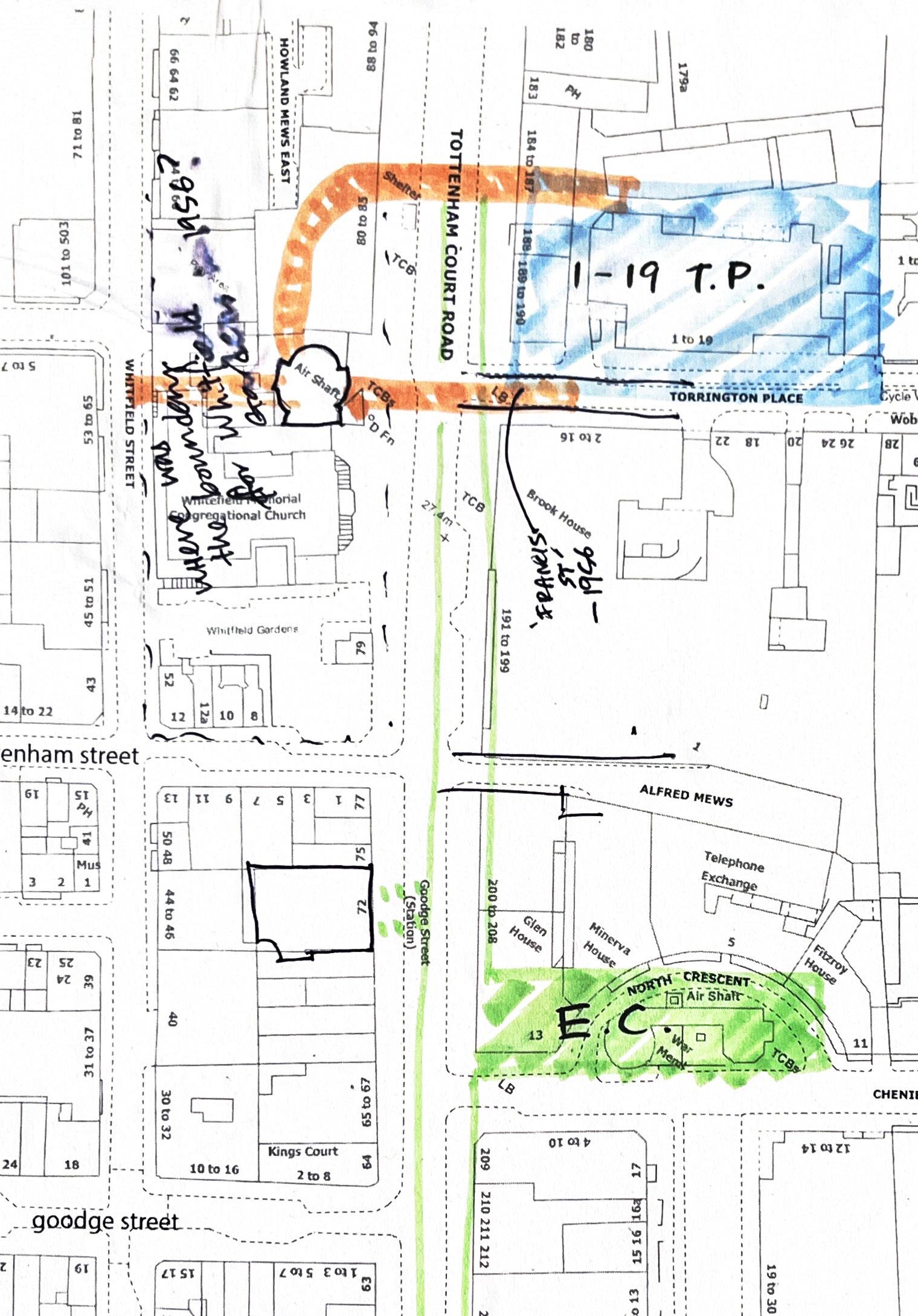

Our bodies leave traces in the spaces we inhabit: dust made of fragments of our bodies that detach, fall, and settle onto architecture, signalling human presence. As Mary Douglas noted, we clean and discard those traces to restore order.1 But who performs this morally charged labour, and do their own traces vanish along with the dust? Housework unfolds in an intimate relationship with the materiality of the house; however the bodies performing these tasks have been invisibilized both through the canon of architectural history and within modern domestic architecture itself.

The house at 2 Willow Road in Hampstead, London (1938–39), offers a revealing case study. Designed by architect Ernö Goldfinger as his family home, it was first inhabited by himself, his wife, the artist Ursula Goldfinger, their two children, Peter and Elizabeth, and three domestic workers: Rosie Hayden, the cook; Betty Boothroyd, the nanny; and the chauffeur whose name remains unknown. However, most accounts of the house have overlooked the role of domestic service in its architectural history. A white door in the corner of the hall that once led to the servants’ quarters — later converted into a

1 Mary Douglas, Purity and Danger: An Analysis of the Concepts of Pollution and Taboo (Routledge, 1991), p. 2.

separate living unit — now stands permanently closed. This thesis aims to reopen that door to critically examine how housework was embodied in modern domestic architecture, and how space materializes and negotiates social structures of domestic life.

2 Willow Road negotiated ideas around gender, class, and service in complex and often contradictory ways. It contributed to the invisibilization of housework, both in its initial design and in its subsequent use and adaptations. Although it has often been celebrated as a modernist house, the ideas around domesticity that informed its design and inhabitation aligned more closely with nineteenthcentury traditions. In this sense, the house was transitional, embodying modernist ideals while simultaneously reproducing long-standing social and gender hierarchies. ‘Progressive’ architectural features such as folding partitions, coved skirtings, or easyto-wipe surfaces did not fundamentally challenge class or gender norms, but some of them ended up highlighting inequalities.

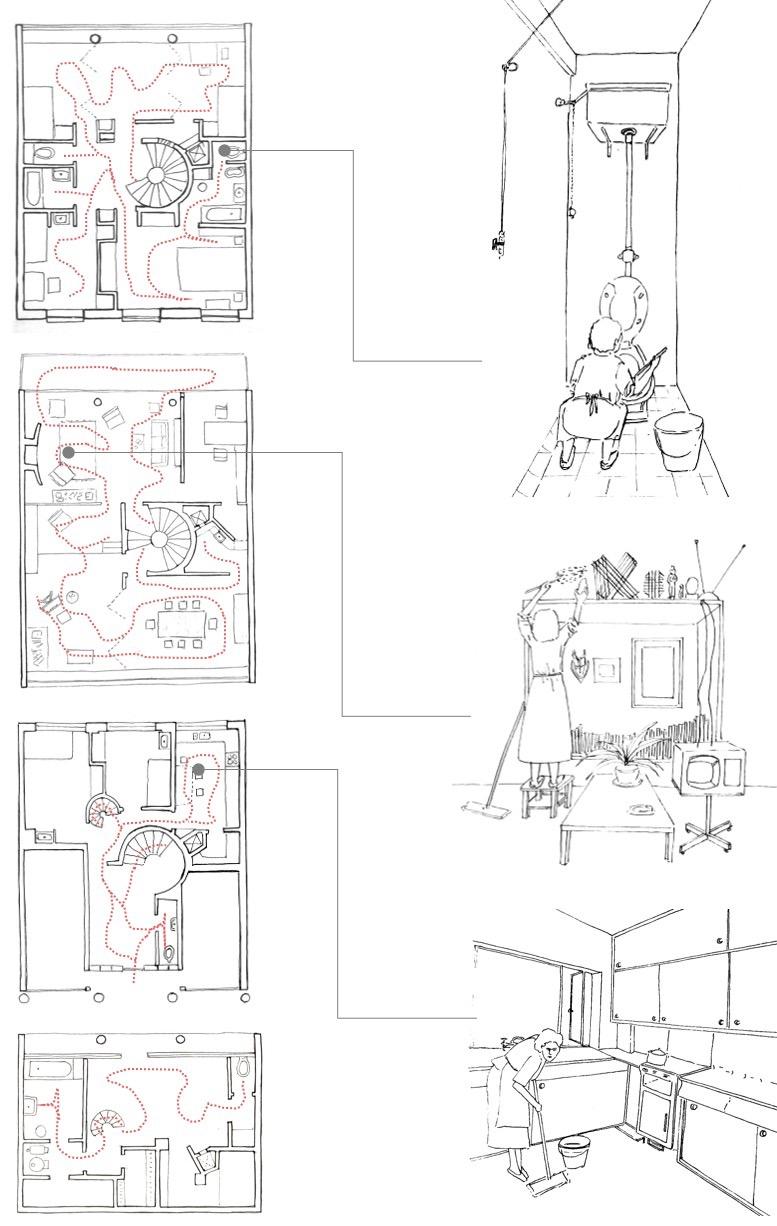

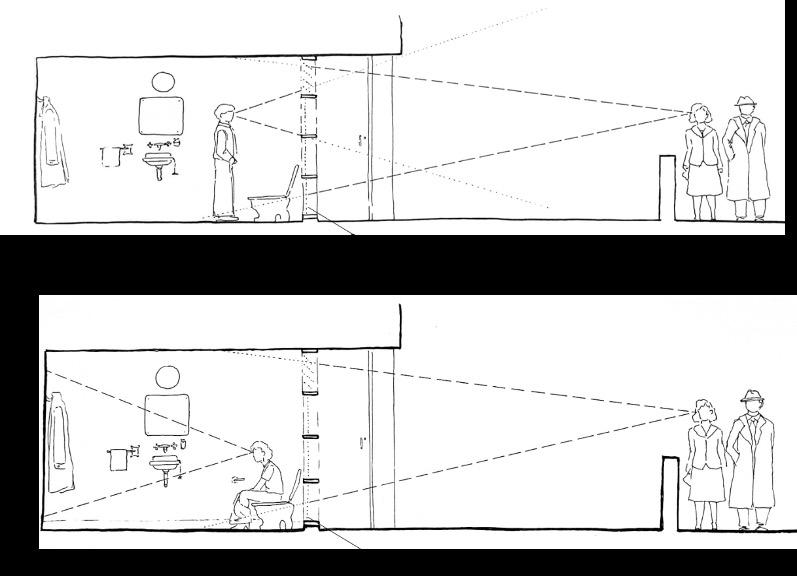

These tensions ran throughout the house. The first kitchen, hidden away, was located in the servants’ quarters so that smells and noises would ‘stay in their place,’ reflecting a traditional view of domestic labour as something to be concealed; yet it was large and functional. Furthermore, the compact layout of the house and Goldfinger’s dislike of corridors hindered the separation of bodies, thereby creating spaces of collision. However, a dumbwaiter was introduced to mediate this tension, encapsulating the paradox of simultaneously erasing the workers’ presence and easing their physical burden, thus functioning as a mechanism for invisibilization. This dialectic of exposure and concealment extended to other areas of the house, most notably the ground-floor cloakroom (toilet), one of the most provocative spaces. Its translucent glass and stark exposure make it sensual and playful, simultaneously obscuring and revealing,

unlike Le Corbusier’s or Adolf Loos’ sinks designed to ‘clean the gaze.’2

The post-war transition to a ‘servantless’ domesticity shifted responsibilities to Ursula Goldfinger. Yet the family still relied on hired domestic help. A daily woman carried out the roughest household tasks. ‘Servantless’, then, meant a reconfiguration of service, not its disappearance. This transition did little to challenge gender roles: housework remained strongly feminized, and middleclass women like Ursula were expected to take responsibility for it. This required a reframing of domestic labour as an act of love, care, and emotional reward, while also being couched in scientific discourses of hygiene and efficiency. This dual framing sought to preserve social status, but ultimately deepened existing contradictions. Love and duty were tangled with labour and science, placing women in a conundrum of conflicting expectations. At 2 Willow Road, this meant Ursula’s responsibilities tied her to the ‘invisible’ realm of the ground-floor kitchen and the nursery, while the daily woman’s presence was rendered even more invisible, as Goldfinger’s correspondence with his father reveals an overlooking of her labour.

The disjunction between the house’s representation in architectural media — marked by austere, carefully staged interiors — and its lived reality — cluttered with objects, rugs, plants, art, and trinkets — reveals that, although hygiene remained an aesthetic value, it was more rhetorical than practiced, and the house was not shaped by modernist hygiene anxieties. Nonetheless, the kitchens designed in 1960–61 retained a stronger connection to those ideals of hygiene and efficiency. The exhibition ‘Planning Your Kitchen’ (1944), developed by Ernö Goldfinger

2 Mark Wigley, ‘La Nueva Pintura del Emperador,’ RA: Revista de Arquitectura, 13 (2011), p. 8

in collaboration with Ursula Goldfinger, seemed to have informed their design. Yet the results were ambivalent. The basement kitchen was more open and integrated with the dining room. In contrast, the first-floor kitchen — the one used by Ursula — was cramped, poorly ventilated and illuminated. Although efficient in its organization, it confined her labour to an isolated, relegated space. Meanwhile, Goldfinger gained Ursula’s studio, symbolically reinforcing a hierarchy of bodies and activities: the architect’s professional work was prioritized over the housework that sustained it.

This imbalance spatialized gendered hierarchies. The first-floor kitchen was hidden and small, barely accommodating more than one person, while Goldfinger’s studio was untouched and even took over Ursula Goldfinger’s studio, which was regarded as the heart of the house. Architecture itself thus mediated inequality — not only rendering housework invisible, but also relegating the female body to invisibility. In this light, works like Ursula Mayer’s film Interiors (2006), which stages female presences within the house, are essential in reintroducing the gendered dimensions effaced in its representation.

This dissertation argues for the critical potential of reframing such sites through the lens of housework, gender, and class. Doing so not only makes visible the often-erased contributions of women like Ursula Goldfinger, servants, and domestic workers, but also challenges the ways architectural history has naturalized their invisibility within modernism. More broadly, it opens a pathway for curating modernist homes with greater attention to housework, highlighting how these spaces were lived, negotiated, and shaped by dynamics of class and gender. Such a perspective not only enriches the narrative of 2 Willow Road but also reframes Ernö and Ursula Goldfinger within the broader discourse of domestic modernity in Britain.

art and trinkets. Reproduced from Alan Powers and the National Trust’s booklet 2 Willow Road (Swindon: 1996).

Top Diagram mapping the woman’s daily work within the house through circulation plans and perspectival vignettes. Image by the author.

Bottom Sections of the 2 Willow Road cloakroom illustrating spatial and visual dynamics: the female figure, seated with her back to the textured glass façade, is unable to see potential onlookers outside, while the male figure, facing the façade as he urinates, is more aware of possible viewers. The textured glass makes the bodies hard to read, blurring their visibility. Image by the author.

Display vs Storage: Visibility, Accessibility and Transparency in Museums with Colonial Inheritances

Helga Beshiri

Museums with colonial inheritances have long served as instruments for organising and displaying knowledge, shaping narratives about civilisation and progress through their spatial hierarchies of display and storage. This essay explores how the visibility or invisibility of collections in such institutions reflects and perpetuates colonial power structures. Focusing on three London case studies — the Wellcome Collection, the Petrie Museum of Egyptian and Sudanese Archaeology, and the V&A Storehouse — it examines how different configurations of display and storage engage with contemporary calls for transparency and decolonisation.

Since the Enlightenment, European museums have embodied systems of classification that ranked societies from ‘advanced’ to ‘primitive’.1 They materialised imperial hierarchies by displaying ethnographic objects as evidence of Western superiority and rationality.2 The very act of collecting and displaying non-Western artefacts — detached from their original contexts—was a mode of controlling both bodies and knowledge. According to Alice Procter, the museum itself is a ‘colonialist, imperialist fantasy … that the whole world can be neatly catalogued, contained in a single building’.3

1 Tony Bennet. The Birth of the Museum: History, Theory, Politics. 1st ed., (Routledge, 1995), p. 34.

2 Adam Kuper, The Museum of Other People: From Colonial Acquisitions to Cosmopolitan Exhibitions (Profile Books, 2023), p. 5.

3 Alice Procter, The Whole Picture: The Colonial Story of the Art in Our Museums & Why We Need to Talk about It (Cassell, 2020), p. 84.

Through curatorial decisions on what to show and how to interpret it, museums construct narratives that sustain this colonial legacy. Display and storage are not neutral categories: the visible exhibition represents selective interpretation, while storage conceals the remainder of the archive. Both spaces, as Swati Chattopadhyay argues, share ‘an ontology of colonial dislocation’, manifesting the displacement and possession at the core of empire.4

Films such as Les Statues Meurent Aussi (1953)5 and You Hide Me (1970)6 expose the violence of museological display and concealment. By isolating objects from living cultures, museums render them aesthetic curiosities for Western consumption, ‘a prison of masks, jewellery, robes, statuettes’ hidden from view.7 Storage thus extends colonial control through invisibility: nearly 90% of museum collections remain inaccessible to the public.8 These unseen artefacts become ‘hoarded capital’, material assets through which Western museums assert cultural authority and generate value.9

The tension between display and storage, therefore, mirrors broader struggles over visibility, authorship, and access. Decisions on what to exhibit or withhold are inseparable from the hierarchies established during empire. Curatorial practices that claim neutrality often replicate those same structures of dominance, determining which stories are told and which remain hidden.

4 Swati Chattopadhyay, ‘[Unarchiving: Toward a Practice of Negotiating the Imperial Archive’, PLATFORM, 5 June 2023 <https://www.platformspace.net/home/ unarchiving-toward-a-practice-of-negotiating-the-imperial-archive>.

5 Les statues meurent aussi. dir. by Alain Resnais, Chris Marker, and Ghislain Cloquet (France, 1953).

6 You Hide Me. dir. by Niki Kwate Owoo (1970).

7 Swati Chattopadhyay, ‘Collections and Containment’, in Small Spaces: Recasting the Architecture of Empire (London: Bloomsbury, 2023), pp. 223–30.

8 Lara Corona, ‘Stored Collections of Museums: An Overview of How Visible Storage Makes Them Accessible’, Collection and Curation, 44.1 (2025), p. 1.

9 Chattopadhyay, ‘Collections and Containment’, p. 223.

The Wellcome Collection epitomises how colonial narratives are embedded in display. Founded from Sir Henry Wellcome’s global collecting during the British Empire, it was reorganised in 2007 around the permanent exhibition Medicine Man. This show assembled artefacts related to health and healing ‘through the lens of a single person, Henry Wellcome’.10 Objects from diverse cultures were categorised by medical theme rather than by origin, stripped of context, and re-presented as trophies of one man’s curiosity.

Despite architectural renovations intended to increase accessibility, in 2022, the exhibition was closed indefinitely for its ‘racist, sexist and ableist’ approach.11 Most artefacts were moved to their storage location in Swindon. The choice of invisibility — removing the problematic display without yet providing an alternative — was framed as an ethical pause. Yet, as critics noted, simply concealing colonial objects neither restores context nor enables restitution.

For Wellcome’s curators, invisibility was a means to avoid perpetuating colonial narratives; however, unless followed by repatriation or reinterpretation, it risks reinforcing the same erasures.

The Petrie Museum, by contrast, reveals the complexities of partial visibility. Created from the excavations of Flinders Petrie and the bequest of Amelia Edwards to University College London in 1892, the museum originated as a teaching resource deeply embedded in imperial archaeology. Its displays followed Petrie’s taxonomic logic — grouping objects by typology and chronology rather than cultural significance. While pedagogically

10 Wellcome Collection. ‘Statement on the closure of our Medicine Man Gallery’, Welcome Collection, 28 November 2022 <https://wellcomecollection.org/statement-on-theclosure-of-our-medicine-man-gallery>

11 Robin McKie, ‘Wellcome Collection in London Shuts ‘Racist, Sexist and Ableist’ Medical History Gallery’, The Guardian, 27 November 2022 <https://www.theguardian. com/culture/2022/nov/27/wellcome-collection-in-london-shuts-racist-sexist-andableist-medical-history-gallery>

coherent, this organisation reinforced colonial hierarchies of knowledge and authority.12

Today, the Petrie Museum occupies a repurposed stable on Malet Place. Its modest architecture restricts both visibility and flexibility: only 8,000 of 80,000 objects can be displayed. Nevertheless, recent curatorial projects seek greater transparency. The 2019 re-design of the entrance gallery introduced labels addressing Petrie’s involvement in eugenics and the colonial conditions of excavation. Displays now highlight neglected figures such as Ali Suefi, an Egyptian overseer, and Violette Lafleur, who safeguarded the collection during WWII.

Initiatives such as ‘Hidden Hands’13 by Steven Quirke attach the names of Egyptian workers to specific artefacts, restoring agency to those previously unacknowledged. The ‘Sudan Living Cultures’ project similarly collaborates with London’s Sudanese community to reframe the museum’s dual heritage and recognise how indigenous knowledge can be seen within existing Western collections. Although constrained by space and bureaucracy, these acts of naming and reinterpretation exemplify microdecolonial practices within a colonial institution.

The newly opened V&A Storehouse (2025) in Hackney represents an architectural and conceptual experiment in transparency. Designed by Diller Scofidio + Renfro, it embodies the idea of visitable storage — a hybrid between gallery and archive where all objects are potentially visible. By ‘flipping the usual progression from public to private’, as Liz Diller explains, visitors can see conservation work and explore vast reserves once hidden from view.14

12 Pierre Bourdieu, ‘The Forms of Capital’, in The Sociology of Economic Life (Routledge, 2018), p. 80.

13 Hidden Hands: Egyptian Workforces in Petrie Excavation Archives, 1880-1924 (Bristol Classical Press, 2010).

14 Oliver Wainwright, ‘“The National Museum of Absolutely Everythin”’: New V&A Outpost Is an Architectural Delight’, The Guardian, 28 May 2025 <https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2025/may/28/v-and-a-east-storehouse-architectural-delight>

Glass walls, open shelving, and cross-sectional displays replace the opacity of the traditional museum. Every six months, the configuration changes, granting different artefacts visibility. This design literally materialises transparency, aligning architectural form with curatorial ethics. Yet full visibility does not automatically equal decolonisation: what remains to be addressed is the interpretation of these objects and the narratives surrounding their colonial acquisition.

Across these three institutions, the relationship between display and storage functions as both metaphor and mechanism of colonial power. Invisibility — whether physical or curatorial — has historically legitimised Western ownership and authority over other cultures’ material heritage. The Wellcome Collection’s retreat into storage shows the limits of erasure as a strategy; the Petrie Museum demonstrates how visibility, transparency, and community collaboration can begin to unsettle inherited hierarchies; and the V&A Storehouse pushes the logic of visibility to its architectural extreme.

Ultimately, the challenge for museums with colonial inheritances lies not merely in making objects visible but in revealing the conditions of their visibility — how space, design, and curatorial practice continue to mediate access and meaning. Only by confronting the intertwined histories of collection, concealment, and display can museums move towards genuine decolonial transparency.

González Carvajal

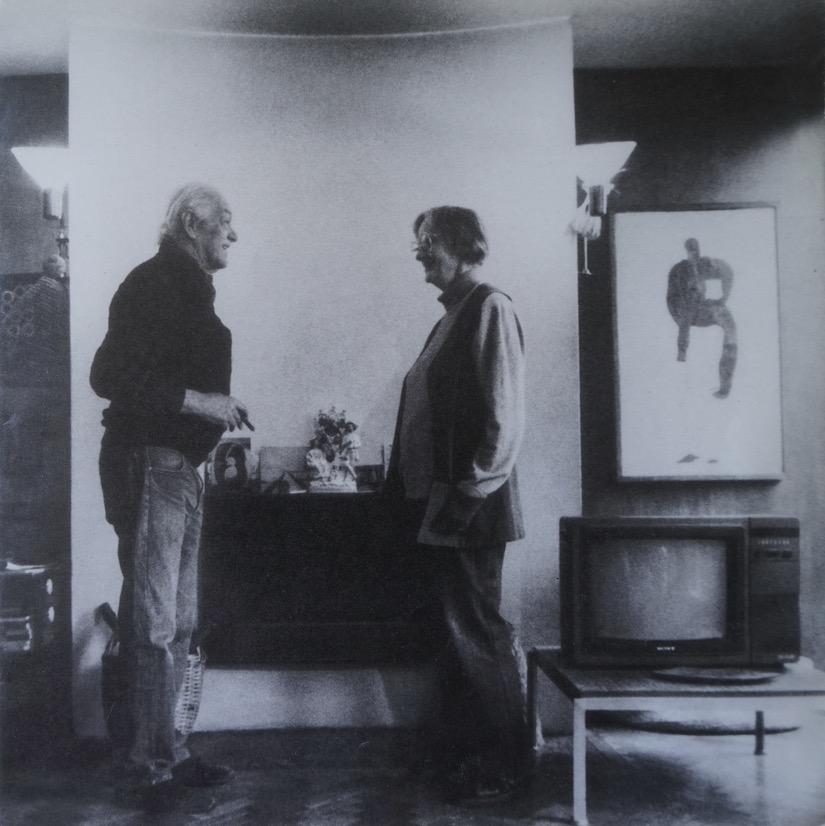

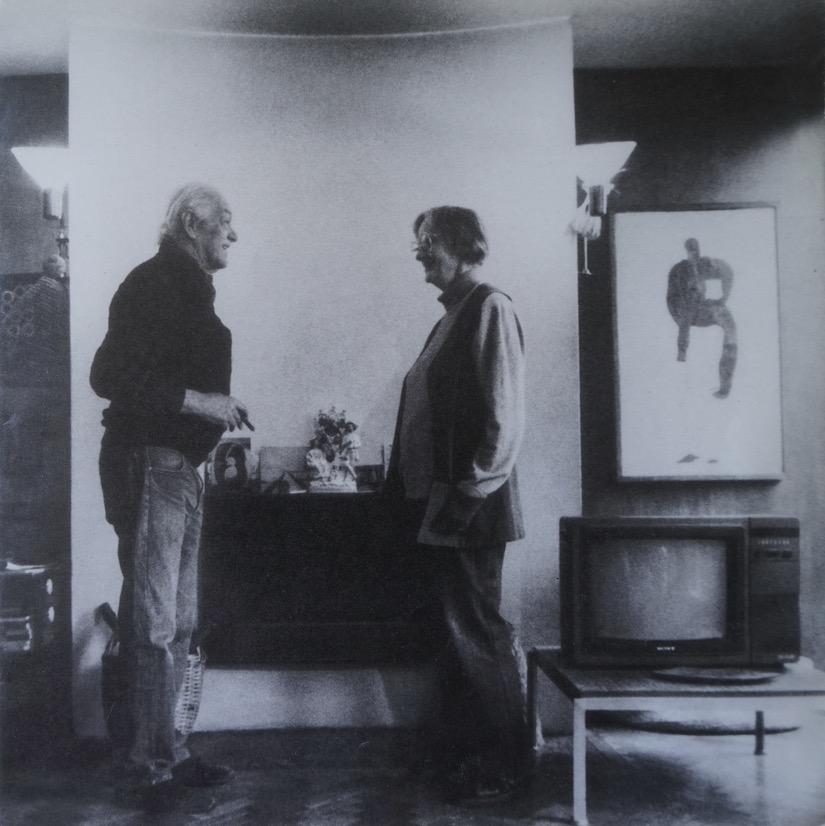

Alison and Peter Smithson’s Exhibition of a Decade ‘54–‘64

This dissertation examines the exhibition Painting and Sculpture of a Decade: ‘54–‘64 at the Tate Gallery in 1964, designed by the architects Alison and Peter Smithson, as a case study of exhibition-making as a form of architectural practice. While the Smithsons are widely recognised for their role in shaping post-war British architecture and the discourse of New Brutalism, their installation design for the ‘54–‘64 exhibition remains underexplored within architectural history. For the Smithsons, exhibitions and installation designs were fundamental to their practice, as they expressed in a series of writings from the 1980s.1 This perspective opens a framework for understanding exhibitions as provisional architectures: representations of spatial and conceptual ideas that often lay the ground for or run parallel to build work, but whose significance is frequently overlooked due to their ephemeral nature. Consequently, this vision raises certain questions that become the central theme of the dissertation. What are the implications of designing the display for an art exhibition in the

1 Alison and Peter Smithson and Karl Unglaub, Italienische Gedanken, Weitergedacht, 1st edn (Birkhäuser, 2014), cxxii, doi:10.1515/9783035602647; Peter Smithson, ‘Conglomerate Ordering: The Restaging of the Possible’, in Helena Webster, Modernism without Rhetoric: Essays on the Work of Alison and Peter Smithson (Academy Editions, 1997); Peter Smithson, ‘The Masque and the Exhibition: Stages towards the Real’, in ILA&UD Yearbook: Languages of Architectures (Sansoni Editore, 1981), pp. 62–67; Peter Smithson, ‘Three Generations’, in ILA&UD Yearbook: Languages of Architectures (Sansoni Editore, 1980), pp. 88–89.

practice of architecture? And at the same time, can an exhibition design be a synthesis of the intention that carries architecture?

Painting and Sculpture of a Decade: ‘54–‘64 (1964) was organised and sponsored by the Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation, a Portuguese institution that established a UK branch in 1956, dedicated to helping artists and stimulating public interest in the arts. The initiative and selection of works were led primarily by Alan Bowness, Lawrence Gowing, and Philip James.2 Conceived as a comprehensive survey of artistic developments in Britain and abroad over the preceding decade, the exhibition brought together 366 works by 170 post-war artists such as Pollock, Kline, Rothko, Dubuffet, Correll, and Paolozzi. Its scale and ambition required an equally rigorous and carefully conceived design, a responsibility entrusted to the Smithsons, which took over two years to develop.

The role of the museum’s architecture, as well as the selection of artworks to be exhibited, marked three completely different stages of the project, which are expressed very clearly through the drawings of the floor plan of the installation. For the architects, the intention behind the design of the installation for the exhibition ‘54–‘64 was to highlight the relationships between the artists’ different works, leaving the architecture of the installation and the Tate itself in the background.3 This allowed the Smithsons’ design to constitute a strategy for creating a space that would distance itself from the conventional museum environment.

From their first curatorial and installation project, Parallel of Life and Art (1953), Alison and Peter Smithson revealed their conviction that architecture develops in dialogue with history and cultural reminiscence. By collapsing disciplinary and cultural hierarchies through images in an exhibition, the Smithsons suggested that each generation of artists and architects learns from and reworks what has come before. Crucially, their first exhibition design established an approach that would shape

2 Lisa Tickner, London’s New Scene: Art and Culture in the 1960s (Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art, 2020), p. 75.

3 Penelope Curtis and Dirk van den Heuvel, Art on Display 1949-69 (Calouste Gulbenkian Museum, 2019), p. 86.

the Smithsons’ later work, positioning exhibitions not only as displays but as vehicles for thinking about genealogy, intention, and the construction of meaning in architecture.

Almost thirty years after the exhibition Painting and Sculpture of a Decade: ‘54–‘64 (1964), the Smithsons’ reflections on this project and the rest of their exhibition repertoire became a much more recurring theme in their writings. These writings expressed the belief that exhibitions could embody an intention which was consistent with each generation of architects. In the draft version of the text of ‘The Staging of the Possible’, later revised and published in 1995 in Italian Thoughts, was introduced a diagrammatic ‘table’ recording relationships between generations of architects and their intentions with an image.4 This schema reframed exhibitions as historiographic tools, simultaneously retrospective and projective. Their final iteration on this idea, ‘Re-staging of the Possible’ in 1997, reinforced this vision; emphasising the exhibition as a medium for tracing genealogies and imagining futures. In this sense, their curatorial and architectural practice operated as a consistent thread linking their early post-war experiments with their later theoretical reflections.

Building on these reflections, exhibition design can be seen as a unique synthesis of architectural intentions, where spatial strategies, object relationships, and audience experience converge into a cohesive whole. In the case of the ‘54–‘64 exhibition, the installation supported the artworks while simultaneously shaping the way they related to one another, creating a dialogue between pieces that extended beyond their individual qualities. It also produced a distinct environment within the Tate Gallery, transforming the existing architecture into a provisional space capable of hosting new experiences and interactions. By bringing together objects, space, and experience, the case of the ‘54–‘64 exhibition demonstrates how architectural thinking can operate beyond permanent buildings, asserting that temporary, curated environments are not merely displays but complex frameworks in which ideas, histories, and sensibilities are communicated.

4 Smithson and Unglaub, Italienische Gedanken, Weitergedacht, cxxii, p. 44.

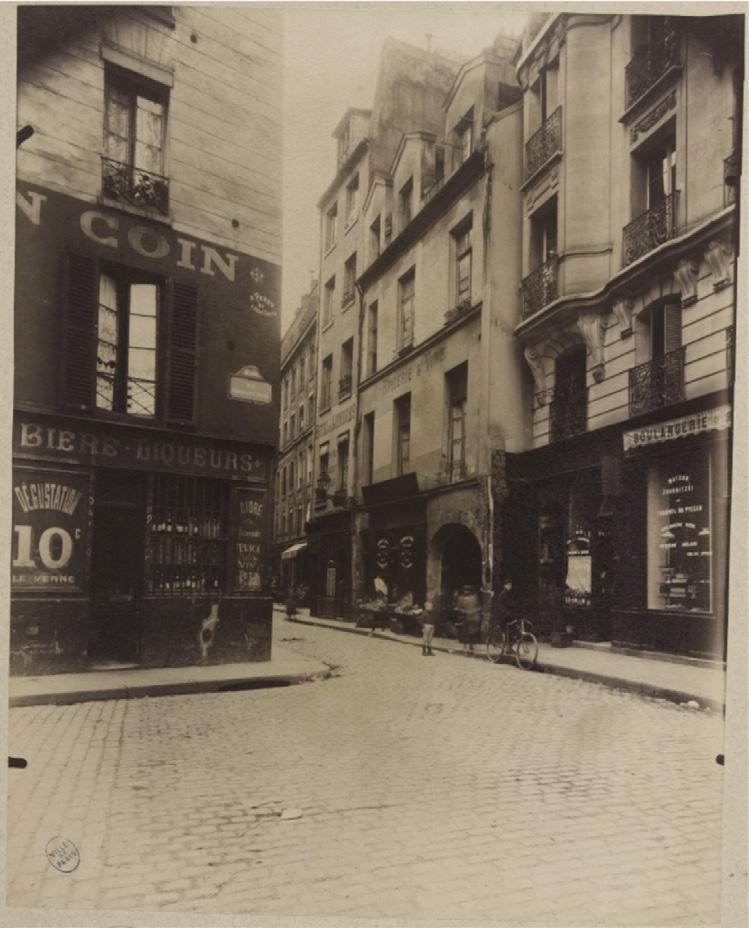

Left Eugène Atget, Port des Invalides [Pont Alexandre III. Escalier et arche, rive gauche], 1913, Bibliothèque Historique de la Ville de Paris, https:// bibliotheques-specialisees. paris.fr/ark:/73873/ pf0001820043/.

Right Port des Invalides in August of 2009. Image by the author via © Google Street View, captured 2025.

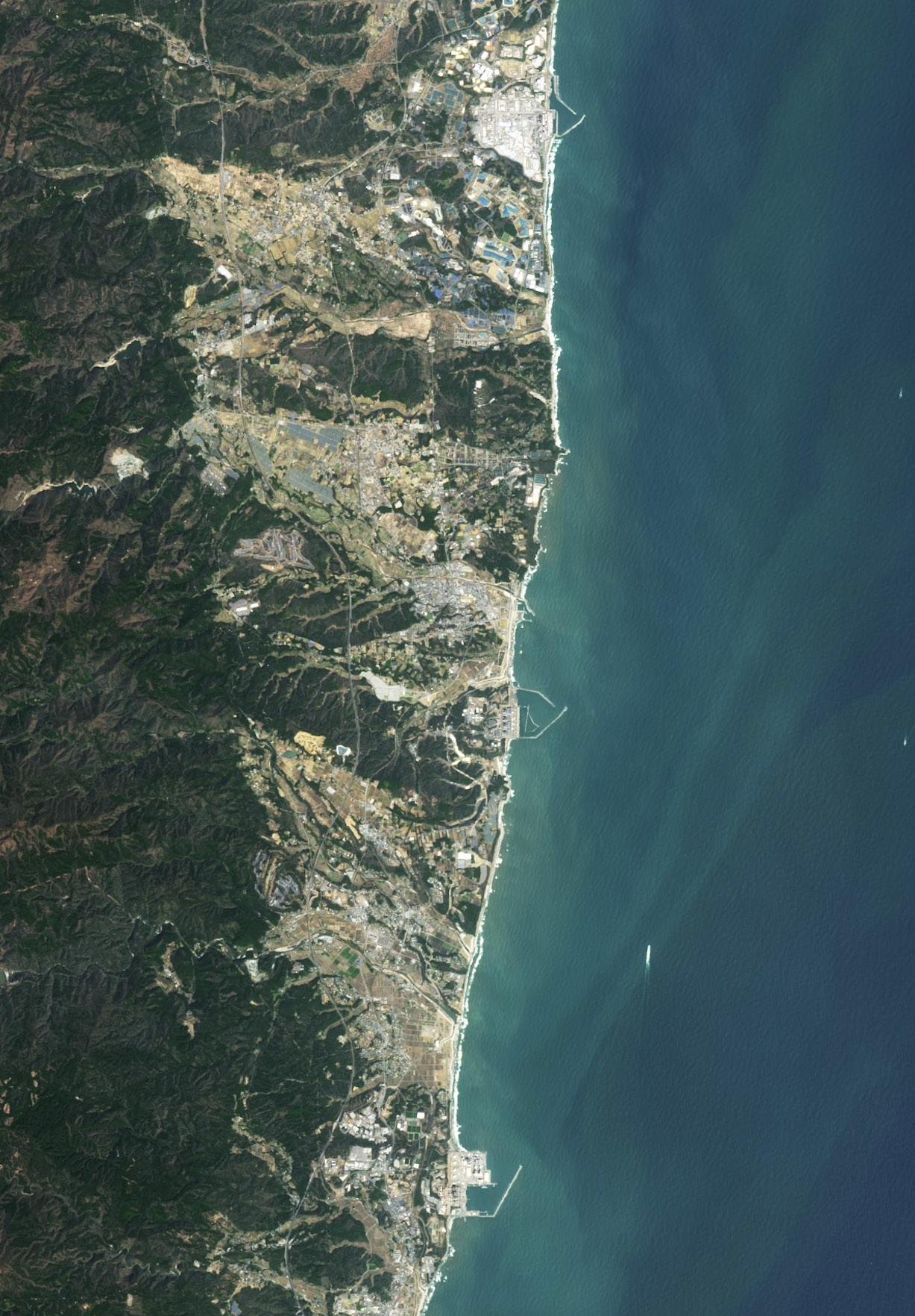

This dissertation investigates Google Street View, a component of Google Maps, as both a visual and historiographical instrument in architectural study. It argues that Street View, through its automated panoramic imaging of the built environment, has become a vast but largely unacknowledged form of architectural documentation and urban representation. The project examines how this machinic archive can be understood within the historical lineage of architectural photography.

Street View is considered not simply as a mapping technology but as a representational system that produces, archives and circulates images of the built environment on an unprecedented scale. Unlike the singular image captured by a photographer who isolates and composes, Street View operates serially and indifferently. Yet through this process it generates a continuous record of streets, buildings and urban change. The dissertation’s central claim is that these images, though made without intent, inherit the documentary impulse that has long informed architectural and urban photography.

Cheryl Gilge describes Street View as a ‘spatialised image’ that fuses photographic and cartographic operations. Her analysis establishes the conceptual ground for understanding Street View as a hybrid visual infrastructure — part image and part

interface.1 This clarifies how the platform collapses distinctions between the photographic act and the mapped territory, between representation and navigation. Drawing on Ariella Azoulay’s conception of photography as a collaborative process2, the dissertation also argues that Street View extends that relationship across code, infrastructure, and user. Meaning arises not at the moment of capture, but through acts of retrieval and reuse. The same relational logic can be traced backward through earlier photographic practices that sought to describe the city systematically rather than subjectively.

Eugène Atget’s work sits at the origin of this lineage. At the turn of the twentieth century, he documented Paris not as an artist but as a maker of documents for clients such as architects, artisans and preservationists who required visual records of façades, shopfronts and courtyards.3 His photographs were practical documents, yet their persistence and breadth turned function into history. What began as a commercial service to capture the built environment became an archive of urban space. His method established how photography could operate as both evidence and interpretation, a condition Street View later amplifies through automation.

Nigel Henderson, working in post-war London, extended this empirical impulse into the social realm. His photographs of East London neighbourhoods captured the vitality of working-class life, observing rather than idealising. Henderson’s method constituted a form of urban fieldwork that used the camera to register both physical and social texture. In

1 Cheryl Gilge, ‘Google Street View and the Image as Experience,’ GeoHumanities 2, no. 2 (2016): 469–84.

2 Ariella Azoulay, ‘Photography Consists of Collaboration: Susan Meiselas, Wendy Ewald, and Ariella Azoulay,’ Camera Obscura 31, no. 1 (2016): 187–201.

3 Molly Nesbit, Atget’s Seven Albums (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1992).

Top Nigel Henderson, Photograph of two heads through a pub window [Bethnal Green, 1949–54], Courtesy of the Tate Archive, https://www. tate.org.uk/art/archive/ items/tga-9211-96-14/hendersonphotograph-of-twoheads-through-apub-window. © Nigel Henderson Estate.

Bottom Two heads seen through a bus window in July of 2019. Image by the author via © Google Street View, captured 2025.

his work the street becomes a site of enquiry, a space where architecture and life intersect.4

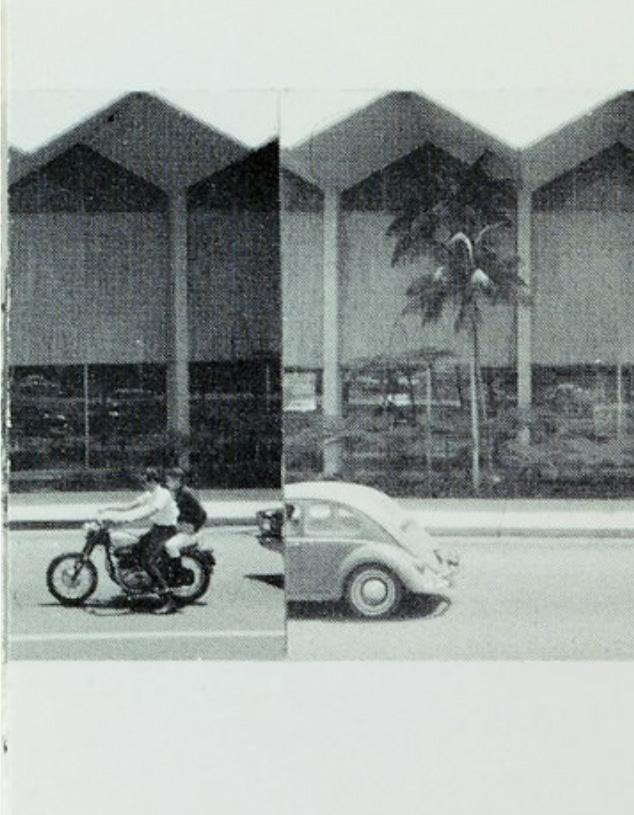

Ed Ruscha, in mid-century Los Angeles, brought this documentary logic into the realm of system and procedure. In Every Building on the Sunset Strip (1966) he mounted a motorised camera to his truck and produced a continuous photographic scroll of a single street.5 Like Atget and Henderson, Ruscha pursued the ordinary, but his method was mechanised, detached, and serial. His project converts the city into a linear, unbroken record assembled through movement. The work anticipates Street View’s automated survey, turning documentation into a procedural operation rather than a subjective act.

Together Atget, Henderson, and Ruscha define the methodological and conceptual ground from which Street View emerges — a history of image-making shaped by documentation, social immersion and automated infrastructure. Street View extends these tendencies and translates them into an industrial form of visual capture. What results is a record both total and impersonal, the city rendered as archival dataset.

Street View also occupies a central position in what might be called post-photographic practice. Contemporary artists such as Jon Rafman, Doug Rickard, and Mishka Henner have reappropriated its imagery to explore the shifting boundaries between authorship and automation. Their works expose the latent aesthetics of Street View and its capacity to record the incidental life of the city without intent or judgement.

Street View continues the lineage of architectural documentation while transforming its conditions.

4 Clive Coward, ed., Nigel Henderson’s Streets: Photographs of London’s East End 1949–53 (London: Tate Publishing, 2017).

5 Edward Ruscha, Every Building on the Sunset Strip (Los Angeles: Ed Ruscha, 1966), Tate Library, London.

Mishka Henner, No Man’s Land, 2011–2013, https://mishkahenner. com/No-Man-s-Land.

The image has become infrastructural, maintained by systems of corporate control and algorithmic surveillance that both preserve and obscure the city they record.

By situating Street View within this historical and methodological continuum, the dissertation redefines how architectural imagery can be mediated and used. It treats the platform not as a neutral mapping tool but as a living archive whose images reveal the conditions of the built environment. In doing so, it reframes architectural photography as a distributed practice, one enacted through systems rather than individuals. Street View’s automation does not end the work of the photographer; rather, it shifts attention from the moment of capture to the acts of selection and interpretation that follow. The ordinary city, endlessly imaged and re-imaged, becomes both subject and method — the ground through which architectural history continues to write itself.