WINTER 2023

THE INNOVATION ISSUE

HELENE GAYLE ’76

ON LEADING SPELMAN COLLEGE

A COMMUNITY OF CROSSWORD CONSTRUCTORS

UNDERSTANDING THE PROTESTS IN IRAN

‘Purpose & Passion’

by Sharon D. Johnson ’85In her new role as Spelman College’s 11th president, Dr. Helene Gayle ’76 builds on her success as a leader in global health to nurture the next generation of Black women

Features Departments

2 Views & Voices

3 From President Beilock

4 From the Editor

5 Dispatches

Breaking Norms by Amanda Loudin Barnard faculty and students are proving that the old way isn’t always the best way

Headlines | Coding Collab; Off the Field, A Winning Partnership; Garden Circularity; Championing First-Time Filmmakers

11 Discourses

Faculty Focus | Manijeh Moradian Read Watch Listen | Books by Barnard Authors; Three Takes on ‘Modern Love’

Arts & Culture | Desperately Seeking Sassy

37 Noteworthy

Alumnae Adventures | Miriam Tuchman ’88

Q&Author | Akil Kumarasamy ’10

AABC Pages | Regional Roundup; From the AABC President; AABC Board election nominees

Class Notes

Alumna Profile | Amy Brand ’85 In Memoriam

A Community of Crosswords

Three Barnard alums puzzle out the grid

ILLUSTRATION BY RYAN PELTIER

Obituary | Beryl Benacerraf ’71

Last Image | Nancy (Goodman) Berlin ’61

On the Cover

Illustration by Jeff Hinchee

FEEDBACK

Sarah Weinstein Dennison ‘89 alerted the Magazine that she appears on the cover of the Fall 2022 issue, which shows an archival photo of a protest against an anti-choice group. She writes: “I am photographed but not ID’d on the cover of the new Fall 2022 Barnard Magazine — I am the short brunette standing next to my friend Samantha Black ‘89 on the right protesting against Operation Rescue.”

“I would like to mention that I was very proud of Barnard when I read that we are celebrating ‘The Year of Science,’ where young women can now study science, technology, engineering, and math — STEM. … I know we are all so proud of our Barnard! And I thank those working to give us a fine Barnard Magazine, which keeps us feeling close to the College. That means so much to us.”

—Jane Forsthoff ’45BARNARD’S TOP FIVE READS ONLINE: “Serving Community”

“The Fight Goes On”

“A Literary Legacy”

“Dogs Don’t Smile”

“Sowing Seeds of Change”

ESSAYS WANTED!

Barnard Magazine would like to see a photograph that resonates with you. One that has a story, Please send the photo, along with a 450-word essay that complements, reflects on, or even loosely relates to the image, and we’ll run the selected pairing in our “Last Word” section of the Magazine. We look forward to hearing from you!

EDITORIAL

EDITOR-IN-CHIEF Nicole Anderson ’12JRN

CREATIVE DIRECTOR David Hopson

MANAGING EDITOR Tom Stoelker ’10JRN

COPY EDITOR Molly Frances

PRODUCTION DIRECTOR Lisa Buonaiuto

CONTRIBUTING EDITORS N. Jamiyla Chisholm, Kira Goldenberg ’07

WRITERS Marie DeNoia Aronsohn, Mary Cunningham, Preetica Pooni

STUDENT INTERNS Zuyu Shen ’24, Tara Terranova ’25

ALUMNAE ASSOCIATION OF BARNARD COLLEGE

PRESIDENT & ALUMNAE TRUSTEE Amy Veltman ’89

ALUMNAE RELATIONS

EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR Karen A. Sendler

ENROLLMENT AND COMMUNICATIONS

VICE PRESIDENT FOR ENROLLMENT AND COMMUNICATIONS

Jennifer G. Fondiller ’88, P’19

ASSOCIATE VICE PRESIDENT FOR EXTERNAL RELATIONS AND LEADERSHIP DEVELOPMENT Emma Wolfe ’01 EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR OF COMMUNICATIONS

Quenta P. Vettel, APR

DEVELOPMENT

SENIOR VICE PRESIDENT, DEVELOPMENT AND ALUMNAE RELATIONS Lisa Yeh P’19

PRESIDENT, BARNARD COLLEGE

Sian Leah Beilock

Winter 2023, Vol. CXII, No. 1 Barnard Magazine (ISSN 1071-6513) is published quarterly by the Communications Department of Barnard College.

Periodicals postage paid at New York, NY, and additional mailing offices.

Postmaster: Send change of address form to: Alumnae Records, Barnard College, Box AS, 3009 Broadway, New York, NY 10027-6598

EDITORIAL OFFICE

Barnard Magazine, Barnard College, 3009 Broadway, New York, NY 10027-6598 | Phone: 212-854-0085

Email: magazine@barnard.edu

Opinions expressed are those of contributors or the editor and do not represent official positions of Barnard College or the Alumnae Association of Barnard College. Letters to the editor (200 words maximum) and unsolicited articles and/or photographs will be published at the discretion of the editor and will be edited for length and clarity.

The contact information listed in Class Notes is for the exclusive purpose of providing information for the Magazine and may not be used for any other purpose.

For alumnae-related inquiries, call Alumnae Relations at 212854-2005 or email alumnaerelations@barnard.edu.

To change your address, write to:

Alumnae Records, Barnard College, Box AS, 3009 Broadway, New York, NY 10027-6598

Phone: 646-745-8344 | Email: alumrecords@barnard.edu

The Way Ahead

When you visit the campus this semester, you might notice that it looks a little different. Just a few weeks ago, as I made my way to Milbank Hall, I couldn’t help but pause as I reached Futter Field. The tents, which had been erected during the height of the pandemic to give our students and faculty a safe and comfortable space to convene outdoors, had been taken down, and in front of me was an open expanse.

At that moment, I was reminded of how far we’ve come and how much we’ve achieved just this past year. We have demonstrated a unique ability to be not only adaptable but courageous when it comes to tackling new challenges. And above all, we have forged ahead, providing students, faculty, and staff with the resources and support they need to flourish and reach their full potential.

More recently, we’ve focused our efforts on fostering a number of leadership development opportunities for members of the Barnard community. It is critical that our staff and faculty feel encouraged and empowered to pursue their interests and grow their skill sets at the College. With the help of Emma Wolfe ’01, Associate Vice President and Senior Advisor to the President for External Relations and Leadership Development, we’ve been able to accomplish this in myriad ways: offering pathways to internal promotions, launching leadership workshops for department chairs, holding monthly training and communitybuilding sessions for staff managers, and more. We recently kicked off a monthly series called Barnard Pro Tip, in which faculty and staff come together in a TED Talk-style forum to share their insights and expertise with fellow community members. These conversations have been edifying and inspiring, and I look forward to more of these thought-provoking presentations.

We’ve also made great strides in expanding the programming around physical, mental, and financial wellness at the Francine A. LeFrak Foundation Center for Well-Being, thanks to the leadership of Dr. Marina Catallozzi, our Vice President of Health and Wellness and Chief Health Officer. From emotional and mental health workshops to a host of course offerings on financial planning and investing, students now have access to a number of resources and tools that address the many dimensions of health and wellness.

In the past few weeks, I have passed by Futter Field many times. I eagerly watch as our groundskeepers and staff work hard to restore the patches of dirt back to fresh grass. I can imagine students gathering on the lawn this spring, locked in conversation, and it feels emblematic of something more — of all the progress we’ve made, from the quiet day-today feats to the larger, groundbreaking initiatives. And what becomes clear to me is that Barnard is always striving for more, always ready for the next challenge.

Imagine That

As I write this letter, I am nearing the end of my pregnancy. Like so many expectant parents, I’ve been reading up on anything and everything about newborn care. There’s certainly no shortage of apps, websites, books, and articles dispensing advice and tips on the subject. With so much information to wade through, it can be tempting to look for a road map. But I have a hunch that parenting is not that prescriptive.

One of the many lessons I’ve gained from the work that is being done at Barnard, and especially from the stories that appear in our Winter “Innovation” issue, is that oftentimes we need to evaluate the opinions, the data, the circumstances with fresh eyes. And that means being open to deviating from established norms in order to imagine, and even test out, new and likely better possibilities. It isn’t always easy to do, but it’s necessary — and, frankly, empowering.

In this issue, we throw a spotlight on the many ways that the Barnard community is, as our writer Amanda Loudin puts it, “pushing the needle,” inside the classroom and beyond. You’ll read about how students, faculty, and staff are taking out-of-the-box approaches to learning and teaching; embarking on new, multidisciplinary research opportunities; and launching key mentorship programs to enhance the student experience. No two initiatives, methods, or programs are alike, but each one demonstrates the tangible benefits of thinking creatively, if not untraditionally. The result is a learning environment that is more collaborative, gutsy, and yes, innovative.

Beyond Barnard’s gates, our alumnae have been no less on the cutting edge. We profile Dr. Helene Gayle ’76, who is now serving as Spelman College’s 11th president after a prodigious career dedicated to social justice and public health. She speaks with us about her new role and what it means to lead a historically Black liberal arts college for women. And we feature Amy Brand ’85, the director and publisher at MIT Press, who has been hard at work piloting a new business model that provides the public with free access to scholarly books. Her entrepreneurial spirit has led her to spearhead a number of endeavors to bring more equity and inclusivity to publishing.

In these pages, whether you’re reading about a fledgling crossword constructor or Barnard’s sustainability-minded groundskeeper and horticulturist, you’ll find that they all have something in common: an ability to think independently. They aren’t hemmed in by rules or old ideologies. They move through this world with imagination. It’s a promising and inspiring outlook for the generations to come.

Nicole Anderson ’12JRN, Editor-in-Chief

Coding Collab

A Barnard-FIT partnership teaches students how to use computer science to make art

How can you reenvision the way students learn and apply coding? That question inspired two professors — Barnard’s assistant professor of computer science Mark Santolucito and the Fashion Institute of Technology (FIT)’s Maria Hwang — to come together to teach the interdisciplinary course Arts and Computing in NYC, in which students had the opportunity to apply computer science skills to create art. The scholars teamed up for the joint learning experience between the two Manhattan campuses in fall 2021. “One of the benefits of Barnard being where it is is that we have access to the City, and building partnerships with other universities allows us to leverage that,” says Santolucito.

Over the course of the semester, students learned how to use code in a number of creative ways, including producing stitch patterns and generating and manipulating music. Santolucito and Hwang also invited guest scholars and professors, such as Saima Akhtar, associate director of the Vagelos Computational Science Center, to share their expertise. The course culminated in a gallery show in the Barnard Movement Lab, where students, like Leah Teller ’22, a math and computer science major, presented her final project, an abstraction of the universe.

Students will be happy to learn that the course marks the start of an ongoing partnership between Barnard and FIT, says Santolucito, who is looking forward to offering more opportunities for the two institutions to collaborate in the near future. “It was a great experience,” he says. —Mary Cunningham

ATHLETICS Off the Field, A Winning Partnership

The women’s lacrosse team mentors young students in Harlem

For nearly a decade, the women’s lacrosse team has nurtured the next generation of athletes through a partnership with Harlem Lacrosse, which pairs Barnard athletes with students from the Sojourner Truth School (P.S. 149) in Harlem.

Skyler Nielsen ’25, who volunteers as a coach, says that life lessons are learned on and off the field. “Adaptability, communication, and leadership are all muscles that need to be worked on continuously in order to grow and develop,” says Nielsen. “The most effective ways [I’ve found] to coach the students [have been informed] by my own strengths.”

With over 1,500 youth participants across five

cities, including L.A. and Philadelphia, Harlem Lacrosse serves the students most at risk for academic decline. For the youth at Harlem Lacrosse, the partnership provides insight into what’s possible.

“They’re so young … but to see someone who they look up to and then to say, ‘Oh, I can do that,’ is the biggest thing,” says Lily Herrmann, program director of the Girls Harlem Lacrosse team for P.S. 149. “It’s a very tangible connection. Barnard and Columbia are not that far away — [the connection] is right there, in their backyard.”

The Barnard student-athletes play lacrosse through the Columbia-Barnard Athletic Consortium, a collaboration that supports Barnard athletes competing with Columbia undergraduates in the Ivy League Athletic Conference and NCAA Division 1 Athletics — making Barnard the only women’s college to offer this opportunity.

In addition, activities off the field help studentathletes bond with the young students in both meaningful and playful ways. Just before the holiday break, they teamed up in groups for the annual gingerbread house competition.

Fifteen boxes of graham crackers and 10 pounds of frosting later, the competitors presented 14 structures to be judged. Not that anyone ended up losing; the students had “won” coaches, tutors, role models — and friends. —Tara Terranova ’25, with reporting by Preetica Pooni

Garden Circularity

A newly established program brings Barnard perennials to Morningside Park

This semester, Barnard plans to team up with the Columbia Climate School and Circular City Week for a citywide celebration. On March 10, Circularity Day NYC 2023, organizers hope to inspire New York consumers to think twice about where a product will end up when they’re done with it. Part of the celebration will include an opportunity to highlight local “circularity champions.” And while Barnard probably shouldn’t nominate one of their own, the College most certainly could hold up lead groundskeeper Keith Gabora’s recent efforts as a perfect example.

Last February, on hearing that the Biology Department was throwing out grow lights, the horticulturist was quick to get ahold of them to repurpose for his shop’s nursery, where he was growing seedlings. From there, with the help of Barnard Garden Club volunteers, the young native plants found their way to the College’s green space along Broadway last spring. Over the summer, the sunloving natives, such as black-eyed Susans, milkweed, and echinacea, flourished and established hearty roots. By fall, Gabora found the plants a permanent home in Morningside Park at 116th Street. His use and reuse of the plants, as well as the lights, demonstrate the efficacy of circularity practices.

“You can see where we’ve ripped out all the invasive plants [in Morningside] and have reintroduced native plants that we grew here on campus,” Gabora says, adding that circularity is already underway for this semester with yet another planting session set to take place on Earth Day, April 22: “It’s quite a big project that’s going to be taking place over many years.” Alumnae, students, and staff who want to pitch in can contact barnardgarden@gmail.com.

Tom StoelkerChampioning First-Time Filmmakers

At the upcoming Athena Film Festival, emerging filmmakers tackle huge issues in the film shorts program

From its inception, the Athena Film Festival has fostered first-time filmmakers. This year’s edition, which runs in person from March 2 through 5, is no exception. With the shorts program alone, 40% of the directors are first-time or student filmmakers. “We know shorts are an important stepping stone to big-time filmmaking,” says Victoria Lesourd, chief of staff at the Athena Center for Leadership. “It’s through shorts as well as other initiatives — like the new Programming Fellowship — that we are giving Barnard students and burgeoning filmmakers an opportunity to break into the industry.” In addition, the festival nurtures a diversity of talent that convey stories and perspectives that might not otherwise reach the screen. Of the 15 shorts, 87% were directed by women, and 67% were directed by people of color. “Women, people of color, nonbinary individuals have historically faced incredible barriers in the film and entertainment industry,” says Lesourd. “Given our home at Barnard, we are deeply committed to leadership and talent development, particularly for groups who often get overlooked by the film industry.”

Here are six standouts from the shorts program, highlighting women-centric projects primarily by up-and-coming women and nonbinary filmmakers:

Dorothy Oliver is the definition of Alabama charm. Filmmakers Jeremy S. Levine and Rachael DeCruz capture the convenience shop owner in the documentary The Panola Project, in which Oliver goes out of her way to get her neighbors vaccinated for COVID-19 by going door-to-door in her rural Black community. Back at the store under a makeshift vaccination tent, like a loving yet persistent auntie, she cajoles and charms the reluctant residents to get the shot and stay healthy.

Of the many issues raised by the Canadian government’s history of forced assimilation policies toward native peoples, the abuse endured by children at the church-run, government-funded residential schools is perhaps the most unsettling. There’s a scene in the documentary The Road Back to Cowessess in which an alumna of the infamous Marieval Indian Residential School of Saskatchewan stares out at a school-adjacent field of recently discovered unmarked graves of more than 750 people, including many students whose names may never be known. Sobbing, she declares that her grandchildren and her grandchildren’s

grandchildren will know about these graves: “They’re not gonna forget this.” Sean Parenteau’s film follows the painful journey of six alumnae survivors as they return to the school grounds to pay their respects.

In Rebecca van der Meulen’s To Wade or Row, the filmmaker deftly portrays the new normal of covert abortions. When Jane visits a small-town motel with her boyfriend, an exchange of coded questions with the receptionist assures Jane that she is not only at the right place but in a safe space — a notion that gets upended when the local sheriff pays an unexpected visit during Jane’s procedure.

Megan Plotka and Matt Nadel’s CANS Can’t Stand centers on how Black trans activists successfully fought to stop the arrests of women of trans experience under Louisiana’s Crime Against Nature by Solicitation (CANS) law, which has been used to terrorize their community. The film weaves together historical context with short testimonials given by queer and trans people who have been arrested under the law and subsequently abused by the police. While the film ultimately shows how activists advance trans liberation statewide, it’s their harrowing testimonials that stick. The film’s co-producer, activist Wendi Cooper, speaks of a police officer who misgendered her, laughed at her, hit her with a billy club — knocking out several teeth — and, after she was released, raped her.

Still Waters is a documentary by Aurora Brachman that lives up to its name. This incongruously beautiful film deals with the long-term aftereffects of child abuse. A daughter asks her mother a question about her mother’s childhood. Her answer prompts them to contemplate the rippling effects of abuse throughout their lives.

In a lighter vein, the laugh-out-loud animated short Lilith & Eve by Sam de Ceccatty kicks off with that awkward moment when the first woman on earth meets ... the first first woman on earth. In this feminist reimagining of the Adam and Eve myth, Eve accidentally bumps into Lilith, Adam’s first wife and his equal. Needless to say, Lilith has a thing or two to explain to Eve about eating apples and accepting subservience to Adam.

—Tom Stoelker

—Tom Stoelker

Breaking Down the Protests in Iran

Professor Manijeh Moradian, author of a new book on Iranian revolutionaries in the U.S., provides insight into the women-led uprising

by Mary CunninghamFor months now, images of Iranian protesters have proliferated in the media. They show women removing and burning their headscarves, cutting their hair, and taking to the streets en masse as they resist armed security forces. These demonstrations erupted in Iran last September over the death of 22-year-old Mahsa Amini (also known by her Kurdish name, Jina) in police custody after she was arrested by the so-called morality police for allegedly violating the country’s compulsory hijab laws.

While this current movement was spurred by Amini’s death, it has roots in earlier protests, including the 1979 women’s uprising in Tehran on International Women’s Day. Manijeh Moradian, assistant professor of women’s, gender, and sexuality studies, examines this history in her new book, This Flame Within: Iranian Revolutionaries in the United States. Through archival research and interviews, Moradian takes a closer look at the Iranian student diaspora in the United States in the 1960s and 1970s through a feminist lens.

Moradian, who holds a Ph.D. in American studies from NYU and an MFA in

creative nonfiction from Hunter College, formerly served as the co-director of the Association of Iranian American Writers. She spoke with Barnard Magazine in late November about the current movement in Iran and how the 1979 protests informed it.

Catch us up: How did the protests spread?

The protests began in the Kurdish Iranian city of Saqqez, Jina’s hometown, and spread to every city and even small towns. It was there that the Kurdish slogan “Jin, Jian, Azadi” or “Women, Life, Freedom” was chanted over Jina’s grave by her relatives and community. The outrage over the destruction of a woman’s life over the rigidities of “proper” hijab swept the nation because every woman in Iran knows the daily experience of vulnerability to state surveillance, control, humiliation, and punishment.

Men joined in, no longer willing to be silent or complicit with legal forms of women’s oppression. The protests crossed class lines and mobilized Iranians from all ethnic and religious backgrounds. Nightly battles between unarmed protesters and heavily armed security forces raged, and different sectors of society organized. Bazaar merchants closed shops in several cities, teachers went on strike, university students staged mass protests and shut down classes.

And where do the demonstrations stand now?

The government has killed over 400 people, including 50 children. There are over 16,000 protesters and dissidents in prison, including journalists, and these are overwhelmingly young people. Several have been beaten to death in prison, and now the government is carrying out executions of prisoners sentenced to death. The Islamic Republic has nothing left but violence — they have a core of stalwart supporters, but they have also alienated many religiously devout people, including some clerics. You can see images of religious people joining the protests and hear people arguing that the government is abusing the people in the name of Islam and acting contrary to the values of Islam. So this is not a movement against religion. This is not a movement against hijab per se but against state-imposed hijab. Whether or not to wear hijab should be a decision made by women, not the state.

Iranian women have been challenging the hijab rule for nearly 40 years. What makes this movement particularly unique?

Actually, the first protests against compulsory hijab erupted in March 1979 — just a few weeks after the Shah left the country and Ayatollah Khomeini returned from his exile in Paris and before the

establishment of the Islamic Republic. It wasn’t until 1983 that the government consolidated enough power to fully implement compulsory hijab.

While different groups of women continued to advocate for their rights — in education, in parliament, in court, and through everyday acts that defied the state’s efforts to control their bodies and lives — many years of activism yielded only small changes that often were undone as hardline politicians asserted power within the ruling circles. With the suppression of the pro-democracy, or “green,” movement in 2009-2010, the road to reform was blocked, and Iranian society entered a new phase of increased alienation and despair about the future.

What’s different now is that the current uprising began with and centers women’s demands for bodily autonomy and equal rights. The average age of protesters is 17, and they want to completely transform the conditions of their lives. They are not asking for reform but for an end to the Islamic Republic form of government.

How do you imagine the protestors’ demands evolving? Compulsory hijab is an ideological pillar of the Islamic Republic, and, because of this, opposition to the state control over women’s bodies has become a lightning rod for a wide range of grievances against the government. As Audre Lorde famously said, “There is no such thing as a single-issue struggle because we do not live singleissue lives.”

This is not really a “women’s rights” movement in the sense of women asking for more rights from the existing state. The use of deadly violence against Jina symbolizes all of the violence and injustice of the government: its oppression of Kurds, Baluchis, and other minorities; its economic corruption and callousness towards poor and working-class people; the pollution of the environment; the decline in living standards; censorship; laws against dating and socializing among men and women; laws against queer people and the state regulation of trans people; and on and on. This has become a moment in which the disparate histories of marginalization and state repression faced by different groups is fueling a national uprising.

Your book chronicles the history of Iranian foreign students who joined a global movement against U.S. imperialism during the 1960s and 1970s. What are the lessons from that movement? And how do they carry over to today’s protests? One key lesson from the 1979 experience is already unfolding in the current uprising in Iran, and that is the

need for a capacious vision of freedom that centers the liberation of women and ethnic and religious minorities. Much of the Iranian left initially supported the Islamist leadership as a kind of authentic cultural representative of the people. The fact that so many Iranian students who returned from abroad to join the 1979 revolution did not really question compulsory hijab or the suppression of the Kurds by the new revolutionary government shows just how much they adhered to a hierarchical version of anti-imperialism that placed national sovereignty above issues of equal rights or democracy.

We are now seeing an emphasis on exactly those issues that were deemed secondary 43 years ago. This historical arc helps underscore the significance of the current revolutionary desires.

Do you see this as a tipping point in Iranian culture and politics?

Iranian society has changed irrevocably. Not only are women openly and brazenly defying compulsory hijab every day en masse, but the fear that kept people in line is gone. Young people have risked everything to try to change the direction of their society. What has already changed is the culture — the way women see themselves and each other and how women and men are transforming their ways of interacting. B

Books by Barnard Authors

by Zuyu Shen ’24 and Tara Terranova ’25FICTION

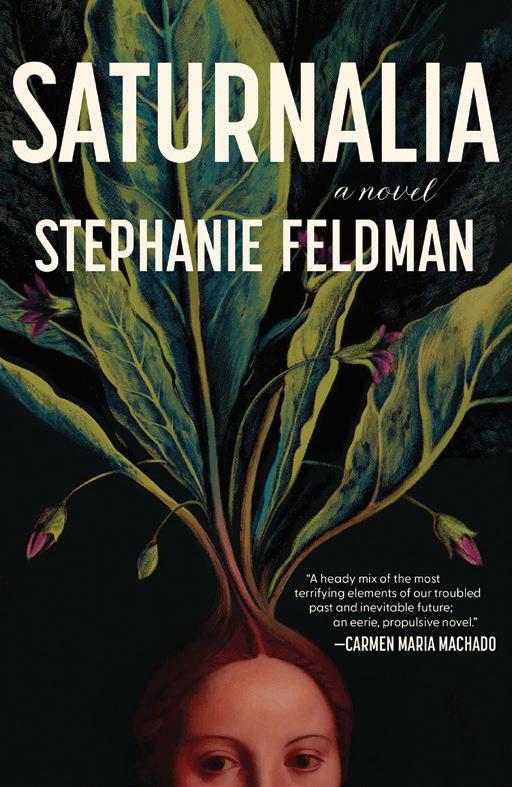

Saturnalia

by Stephanie Feldman ’05

by Stephanie Feldman ’05

In this dystopian thriller, set in a hazy future Philadelphia saturated with climate crises and economic disasters, Nina surreptitiously returns to the exclusive Saturn Club, known for its mysterious occultist practices, where she was once a member. At the club’s wild masquerade party, she uncovers a horrifying secret and realizes she must act quickly to save lives, including her own.

A Small Door

by Michele S. Lowy ’76A Jewish family is forced to evacuate their home in Belgium after the Nazi invasion during World War II. As they attempt to escape war-torn Europe, 19-year-old Rachel and her brother, Alexander, articulate the despair felt throughout the continent, from occupied France to Auschwitz. While Lowy’s characters are fictional, her debut novel is based on the experience of escaping the Nazis as recounted in her grandfather’s unpublished postwar memoir.

NONFICTION

Climate

by Julie Carr ’88 and Lisa Olstein ’96These epistolary essays, a collaborative call-andresponse between the two poets, express deeply sensitive concerns about the disturbing issues that infiltrate modern life, including climate change, school shootings, and sexual abuse. The friends, writing to each other about their lives and hearts with poetic language, prompt contemplations on philosophical and political issues that often go unnoticed or seem unsayable.

Unknowing and the Everyday: Sufism and Knowledge in Iran

by Seema Golestaneh ’06Through ethnographic case studies, Golestaneh delves into how the texts and practices of classical Sufism remain in dialogue with contemporary Iranian life. Exploring the Sufist idea that human knowledge is bounded and some parts of the sacred world will remain unreachable, Golestaneh proposes that this limit is actually a starting point for humans to reconfigure notions of self and reality.

Miriam Hearing Sister

by Miriam Zadek ’50In this evocative memoir, Zadek recalls growing up with two deaf sisters and a hard-of-hearing father in a Jewish community with a constrained understanding of deafness and explores how this experience morphed into her lifelong advocacy for deaf people. In brief, affecting vignettes, Zadek reveals the dynamics of mid-20th-century Jewish and deaf communities in a distinctive and potent way.

Daughter of History

by Susan Rubin Suleiman ’60Suleiman, a professor emerita of French and comparative literature at Harvard, explores her early life as a Holocaust refugee and American immigrant, taking herself as an example of how historical events shape our individual lives. The author tells her story through such everyday objects as a traveling chess set, and her narration inquires into the complexities of immigrant families and losses that carry over generations.

The

Politics of Religious Literacy: Education and Emotion in a

Secular Age

by Justine Ellis ’11Ellis offers a new approach to engaging with and understanding how the popular conception of religious literacy affects today’s modern multifaith democracies. Her book details the practices that create so-called secular societies while questioning the true nature of their status quo.

Buried Beneath the City

by Amanda Sutphin ’92 (co-author)This book explores the archaeological history of New York City alongside lavish images of objects excavated there. Through daily items that illuminate the details of everyday life across eras and cultures, this urban archaeology reveals how the City has been constantly rebuilding itself, from the first traces of Indigenous societies more than 10,000 years ago to its transformation into a modern metropolis. B

Three Takes on ‘Modern Love’ Barnard alums explore the intricacies of love and relationships in the New York Times’

Modern Love column

by Tom Stoelker and Nicole AndersonIn recent years, several of our very own Barnard grads have contributed to “Modern Love,” the immensely popular New York Times column on what love looks like today. The column has spawned another column, a contest, and a television series, in addition to a podcast launched by yet another Barnard alumna. The stories from our alums demonstrate that modern love is a concept that is both familiar and evolving. From open relationships and gay courtship to a daughter’s memories of her mother, the universality of the emotions expressed in the three essays underscores the diversity of experience. We spoke with our Modern Love writers — and the podcast’s founding producer — about what it was like to contribute to this beloved column.

ERIN THOMPSON ’02

“If a Rat Falls Into Your Bed, Call Your Lover’s Boyfriend”

Thompson’s April 2022 contribution to the column starts with every New Yorker’s worst nightmare: finding a rat in the apartment. In this amusing piece, Thompson refuses to accept the help of a man, specifically her girlfriend’s man.

Much of your writing focuses on art-world-related issues. What was it like to write something more personal?

I was raised in a church that tried to make me believe that I would go to hell for being queer or having sex before marriage. I wish I’d had the Modern Love column when I was young — to read funny, sweet stories celebrating all sorts of ways of living, loving, and having sex. I’ve been writing personal essays for the past few years in the hopes of connecting with readers who might need them.

What kind of reception did you receive?

I heard from people in open relationships that they appreciated the column, both as a nondramatic depiction of an open relationship and as an acknowledgment that I’m in an open relationship at all. I know lots of people who aren’t public about all their relationships for fear of blowback.

There are some wonderful comic turns in this story. I didn’t even have space for all the funny parts! For example, I think the rat was karmic retaliation. That evening, I had been to a book launch event where the author of a memoir about sex work reclined nude on a table, their body covered in creampuffs for guests to eat. “That was the most New York thing ever!” I thought as I fell asleep. Maybe the city sent in the rat to show that she could do me one better....

I hope there are no more rat sightings in your apartment. Not in my apartment, but I did overhear the super who was so skeptical about my rat telling an exterminator that the building was having problems with rats in the trash. Vindicated!

MADELINE TAYLOR-ÖRMÉNYI ’16

‘United by Flight’

Taylor-Örményi’s January 2021 Tiny Love Story recalls a Barnard class in New York ornithology where she met the love of her life.

For “Tiny Love Stories,” you tell your personal narrative very succinctly. What were the challenges and advantages of this abbreviated format?

I tend towards verbosity in my writing, so the 100word limit was a challenge — cutting it down to fit the limit was agonizing! But it was also a helpful limitation, because it forced me to focus on the details that mattered most and to trust my readers to make the leaps between them.

How does it feel to read or revisit your story a few years later?

It feels special and sweet to revisit this piece, especially because this tiny story has come full circle in a funny way — my wife now works as the technical supervisor of the Glicker-Milstein Theatre at Barnard, where I proposed to her!

Continued on page 77

Desperately Seeking Sassy

Barnard Library adds the full run of the iconic teen magazine to its catalog of late, great, and current magazines

by Marie DeNoia AronsohnWhen author and therapist Mary Pipher published her seminal book Reviving Ophelia in 1994, she underscored the contradictory, confusing, and damaging messages directed at adolescent girls.

“Girls struggle with mixed messages: Be beautiful, but beauty is only skin deep. Be sexy, but not sexual. Be honest, but don’t hurt anyone’s feelings. Be independent, but be nice. Be smart, but not so smart you threaten boys,” she wrote in her New York Times bestseller. Pipher and others pointed to mainstream media for helping to reinforce this confusing, impossible set of teen girl standards.

Enter Sassy, the magazine that offered a very different message, a counterpoint to the teen girl magazine model of the time. For a number of women who came of age during the late 1980s and early ’90s, Sassy holds a unique place in their hearts. The edgy teen glossy, helmed by founding editor Jane Pratt, was an oasis of real-girl feminist power and celebration in a sea of magazines that featured the prevailing themes of the day — namely, how to be thinner, prettier, smarter, and more appealing to boys.

“Sassy was a refuge from airhead teenybopper magazines, and in its first two years, the magazine established its worldview,” wrote Kara Jesella and Marisa Meltzer in their 2007 book, How Sassy Changed My Life. “Girls weren’t encouraged to be smart for the sake of getting good grades or getting into a good college. Instead, they were encouraged to be themselves.”

From its beginnings, it was clear that Sassy was a different kind of teen publication, making its mark with articles such as “So You Think You’re Ready for Sex? Read This First”; “Backstage at Miss America,” an exposé on the dehumanizing aspects of the pageant; and “Life After Suicide,” which covered the deaths of three teens and how it devastated their families. When the magazine folded in 1996, after an eight-year run, it left a gaping hole.

Now the full, 80-issue collection of Sassy has a home at Barnard. Jenna Freedman, director of the Barnard Zine Library, working in her capacity as the personal librarian for the College’s Department of Women’s, Gender, and Sexuality Studies, spent six years trolling eBay and Twitter to collect the entire run. Freedman says she set out on this quest partly because she received a number of inquiries over the

years. While researching their book, Jesella and Meltzer had even cross-referenced Sassy ’s listings of zine recommendations, and that led them to Barnard’s robust zine library.

“Sassy had a zine-of-the-month feature, so [some of our] zines are widely ordered and read because they appeared in Sassy,” says Freedman. “It seemed the magazine had a special relationship with our zine library. I guess I was thinking with both brains, as director of the zine library and gender and sexuality studies [when I decided to acquire Sassy].”

The do-it-yourself publications known as zines have a strong base of support at Barnard. The collection encompasses a wide swath of personal and political publications on body image, the queer community, the feminist punk movement riot grrrl, sexual assault, and more. Magazines with a feminist/rebel ethos are no strangers to Barnard Library’s stacks. Among the library’s collection are Bust (selfdescribed as a magazine that covers music, news, crafts, art, sex, and fashion from an independent, third-wave feminist perspective) and $pread (a magazine by and for sex workers and those who support their rights).

In addition to Barnard’s extensive zine library, Freedman has made an effort to bolster the College’s collection of iconic general and special-interest magazines — among them, Ebony, which covered the lifestyles and accomplishments of influential Black people in fashion, beauty, and politics and is now back on newsstands under new ownership. Ebony has a new, permanent place in the stacks, thanks to a legendary professor.

When Barnard Africana studies and English professor Quandra Prettyman died last year, her daughter, Johanna Stadler, made Prettyman’s extensive collections available for the library to review. Prettyman had a collection of issues of Ebony (and Gourmet). Freedman claimed four nonconsecutive calendar years of Ebony to supplement the library’s digital access.

“For most of Ebony ’s run, the magazine was a large format, which feels different when you’re holding versus beholding it. I think there’s also value in seeing how the pages have faded a bit over time,” says Freedman. “It’s a visual, and maybe

The edgy teen glossy ... was an oasis of real-girl feminist power and celebration in a sea of magazines that featured the prevailing themes of the day — namely, how to be thinner, prettier, smarter, and more appealing to boys.

even olfactory, reminder that the item the researcher is viewing is of a different time, perhaps older than they are.”

The magazines in the library’s eclectic collection are, for the most part, no longer in print but live on as primary and secondary sources for Barnard researchers and students. Freedman expects students will tap into the Sassy collection for a range of projects, from researching ’90s, thirdwave feminism to the popular culture and fashion of the era.

Barnard associate professor of history Andrew Lipman followed Freedman’s hunt for Sassy issues and helped by retweeting her posts on social media. “It interested me just because, you know, I grew up as a teenager in the 1990s. And my older sister had a subscription to Sassy,” explains Lipman. He says that as a preteen boy, he, too, could tell Sassy offered a unique perspective.

“It was just a totally different kind of magazine because it was taking a feminist point of view. It had something of an aesthetic that I didn’t realize then, but I think I can recognize now, was sort of influenced by zines,” says Lipman. “I advise senior thesis projects. I would say [if you’re exploring] ’90s young women’s feminism, [Sassy] is a pretty important source.”

A special report in the fall 2021 issue of the Columbia Journalism Review points to “Sassy ’s progeny,” including the publications Jezebel, The Hairpin, Worn, Feministing, Bitch, and Bust. The article — “Teen Vogue: OK, Seriously” — pays particular attention to Sassy ’s most popular current offspring and notes that “Teen Vogue has surpassed even Sassy ’s political chutzpah.” Media analysts note that Teen Vogue has even more forward-thinking, inclusive content.

There’s no denying that Sassy made its mark: “If magazines best represent the time in which they were created, then Sassy is the ultimate avatar of its era,” wrote Jesella and Meltzer in the final chapter of their book.

Freedman believes the addition of Sassy to Barnard’s collection adds an important layer to a multidimensional understanding of female empowerment. “By having several of these publications together, we’re putting feminists from different eras and generations in conversation with each other,” says Freedman. B

“If magazines best represent the time in which they were created, then Sassy is the ultimate avatar of its era.”

Breaking Norms

Barnard faculty and students are proving that the old way isn’t always the best way

by Amanda Loudin

by Amanda Loudin

most of these unique opportunities. The old ways may be good, but new ways may be even better.

After more than 130 years of providing a stellar liberal arts education, Barnard’s faculty and staff could easily rest on their laurels. But instead, the College perpetually innovates, preparing students for the future. Nowhere is that more apparent than in a recent crop of classes, seminars, and programs. Using multidisciplinary approaches, these new offerings combine cross-sectional methods, research, and practices to open students’ eyes to all that’s possible. Innovation comes in all shapes and sizes. As a team, the Barnard staff, faculty, and students are pushing the needle in myriad ways, leading to breakthroughs that extend well beyond the campus.

ILLUSTRATIONS BY JEFF HINCHEEComputing for Critical Thinking

Traditional thought would suggest that liberal arts students might not have much interest in computer science. But today’s learning environment is anything but traditional, and Barnard’s Computing Fellows program turns that line of thinking upside down. In fact, the three-year-old program makes a strong case for exactly why liberal arts and computer science can be a very good match.

“We want to bring the excitement and awareness of computing to all students and lower the barrier of entry,” says Rebecca Wright, the Druckenmiller Professor of Computer Science and inaugural director of the Vagelos Computational Science Center. “In today’s world, it’s critical to engage with computing.”

It’s also important, says Wright, that students learn to think critically about computers, how they shape the world, and how the world shapes them. To that end, the Computing Fellows program has helped instructors bring computational activities and projects into their classes, showing how computing is useful across a wide range of disciplines.

Computing fellows in the program — around eight to 10 per semester — take on the role of peer academic leaders. They meet regularly to build community, discuss pedagogy, and put together activities for the classroom. “It’s very much a cohort experience,” explains Wright. “The fellows work together with the instructors to help bring computing into the classes.”

In a course about history and climate, a fellow led an interactive coding workshop in which students used the Python language to graph the average temperatures on earth over many decades. “The activity included a discussion about how to interpret the data and how it might contribute to science and decision-making,” Wright says.

Other collaborative efforts have involved courses like Education in a Polarized and Unequal Society. A fellow worked with the instructor to incorporate the use of computational and data visualization tools into the class throughout the semester. The beauty of the program is that it can be utilized in multiple classes. And in an Intro to Neuroscience class, a fellow led a workshop examining the circadian rhythms of fruit flies. The fellow guided the students through the coding steps needed to visualize data from the professor’s lab of fruit flies with modified and unmodified brains. Students were then tasked with guessing from the visualizations which data came from the modified or unmodified flies.

Both students and fellows benefit from the program, and perhaps the biggest takeaway is this: “Students learn to use code to make sense of information, to form arguments, and to make informed decisions — regardless of their field of study,” says Wright. “The program helps the fellows deepen their engagement with computing. It’s training that fosters clear communication and empathy as they work with their peers.”

Students Helping Students

A deliberate “rebranding” of a program or department is always a big undertaking, but sometimes it’s warranted. That was the case in 2019, when the Office of Disabilities Services at Barnard became the Center for Accessibility Resources and Disability Services (CARDS), says current director Rebecca Sime Nagasawa, who learned that prior to her tenure, there had been “some less-than-stellar student experiences, so the College became very intentional about our response.”

Barnard began the transformation by forming a working group to address accessibility and improve resources. “We added two accommodations coordinators, expanded our capability for accommodated exam proctoring, and partnered with other campus offices to create a pipeline of support,” says Sime Nagasawa. “Logistically, we worked with the resident life offices to ensure the dorms and dining facilities are accessible to students.”

CARDS has also worked hard to provide academic coaching and bolster students’ executive functioning skills like planning and meeting goals and focusing in the midst of distraction. In another show of support, CARDS founded a peer mentoring program in 2019. “This matches [juniors and seniors] with new students with similar diagnoses,” explains Sime Nagasawa. “The [first-years] benefit from their mentors in learning how to navigate specific issues, whether physically or academically.”

A different peer support group, formed as the pandemic began, has proven its staying power, too. Initially strictly remote, the group of students registered with CARDS met monthly online to provide camaraderie throughout the pandemic. An unexpected benefit: It taught CARDS how to better meet the needs of students with various disabilities in a remote environment. “Students who have hearing disabilities are often proficient in lip reading, but over Zoom, that gets tougher,” says Sime Nagasawa. “Even wearing a mask in person can create a host of issues.”

As students transitioned back onto campus for live instruction, CARDS turned its focus to helping an entire class of students who had only experienced remote learning. “They needed resources to figure out how to integrate into campus life,” Sime Nagasawa says. “The peer mentoring and individual class year coordinators became essential.”

CARDS considers the postgraduation experience as well. Some of the peer mentors remain active even after entering the workforce, helping the disabled undergraduate population as they prepare to enter the world outside campus. Members from the Class of 2021 took part in these efforts by posting advice to students who are registered with CARDS on social media and, later, participating in a panel discussion in which they “shared strategies they used to successfully persevere to graduation as well as land positions in the workforce or graduate school,” says Sime Nagasawa.

This is an especially helpful piece of CARDS, says Sime Nagasawa, because while disabled students can find a comfortable, flexible experience at Barnard, they must eventually transition to life after graduation. “Our goal is to deliver efficient services in support of building a strong student and alumnae community.”

When Design Informs Well-Being

When you picture a classroom, you probably think of a series of desks and chairs, or a big table with chairs around it. While this design has long worked for most students, for some it just doesn’t. Sitting still for a long lecture or seminar can be nearly impossible for neurodivergent students, who might need to walk around, or find a corner to take a break.

That’s just one of the considerations under the microscope in the “Environments for Inclusion” seminar taught by Irina Verona, adjunct assistant professor in architecture and an expert in designing for neurodiversity at the firm Verona Carpenter Architects. “There are so many things we can do with design in order to empower the occupants of a space,” says Verona. “There’s a big cultural shift that needs to happen in order to accommodate a range of people.”

The mission of the seminar is to help identify biases in building and space design and focus on ways to undo them. This can extend from classroom space into open public spaces as well. “Public spaces have differences beyond the physical that we should consider,” explains Verona.

The students did a sensory audit of open spaces on the Barnard campus, reimagining certain areas. “We record visual characteristics but also sounds, smells, and textures, and how a body might react to them,” says Verona. “Many of the students envisioned a safe, cocoonlike environment. These are the hidden desires in design that we need to take into consideration.”

Verona and her team found that for many students, the idea of creative redesign resonated. This is a population, she says, that has long lived with frustration when it comes to learning and living environments because their needs are not always

met. “We’re used to seeing physical accommodations for mobility limitations,” she says. “Picture a ramp for wheelchairs, for example. But other cognitive- or sensory-related differences aren’t always visible, and we just expect people to adjust to their environment.”

This year will be the second that Barnard has offered the architecture seminar, and enrollment was capped at 16. “We had a lot of interest but opted to keep it small,” Verona says.

Last year’s class turned out two students who continued to do research with Verona after the seminar. They investigated historical moments surrounding inclusion and design, going back to the late 1970s when the push began for physical accommodations. They learned that since then, progress has been slow with regards to design, and they’ve expressed interest in continuing the conversation and study.

“Many of the solutions are really quite simple,” says Verona, “from dim lighting to chairs without backs or seating off to the side, rather than around a table. It’s all about ensuring there are choices available.”

SPARKing Conversations on Protest

The murder of George Floyd. The Chinese government’s zero-COVID lockdown policy. The Supreme Court’s overturn of Roe v. Wade. The death of 22-year-old Mahsa Amini in the custody of Iran’s “moral police.” All have ignited widespread protest, and behind every protest is the desire to drive change.

With this in mind, the Athena Center for Leadership has selected “Protest” as the theme for its SPARK events and experiences this year. It’s a fitting choice for the series, now in its third year.

“We focus on changemakers and explore how change happens,” explains Umbreen Bhatti ’00, the center’s Constance Hess Williams ’66 Director. “We look at what people are working on and where students can find inspiration to help them understand what’s going on behind the scenes.”

SPARK achieves this through a series of lectures, films, field trips, panel discussions, and more, which are open to students, staff, faculty, alumnae, and friends of the community.

Past years’ SPARK topics have included the racial wealth gap, women’s reproductive freedom, and journalism for a Black audience. Events are collaborative, multigenerational, and allow for many perspectives.

This year’s focus on the topic of protest involves deep dives into current and historic protest movements. Following a film screening about the 1969 Stonewall uprising, for instance, participants took a field trip to important LGBTQ-related sites, using these two formats to instruct on the topic. An Iranian activist spoke to participants about the current protests in her country, which have involved mass public hijab burnings. All the SPARK events showcase the many forms and

contexts of protest.

“We want to highlight what makes a protest effective, who’s involved, and what role protests have taken in driving change in the world,” explains Bhatti. “We want students to think about expanding their ideas of protest.”

As SPARK participants look back, in the moment, and ahead, they have the opportunity to compare and contrast as well as consider what an effective protest can accomplish.

“When we look at Iran, for instance, what’s different this time?” asks Bhatti. “Or if we look at the protest of sexual misconduct in the workplace, what has changed as a result? There are many layers of complexity and nuance to consider.”

Bhatti says that Barnard serves as the perfect space for these conversations and approach. “We could do this at a library, but it wouldn’t feel the same,” she says. “This is a co-created, co-shaped series of events with a wide variety of players. I can’t think of another place with all these feminist minds where this could happen.”

Toddlers, Caregivers, and Emotional Well-Being

If you’ve ever attempted to get a group of toddlers to sit down, sit still, and stay interested in something for longer than 10 minutes, you know it’s a difficult task. Add in the layer of trying to understand this age group’s relationship with parents and how that impacts their emotional development, and you can appreciate the latest research challenge the Barnard Toddler Center is undertaking.

A collaborative effort between the center’s long-serving director, Tovah Klein, and Nim Tottenham ’96, professor of psychology and director of graduate studies at Columbia, the project will draw on Tottenham’s lab, the Toddler Center’s new, expansive space in Milbank Hall, and the women’s combined backgrounds and skill sets.

Klein, who is also a professor of psychology, and Tottenham were a natural fit for collaboration, with complementary areas of knowledge plus a long-standing relationship: Tottenham was Klein’s first student at Barnard. “We’re combining my knowledge of toddlers and Nim’s knowledge of research,” says Klein.

The project centers on understanding what caregivers do or don’t do to enhance children’s emotional well-being early in life. The new Toddler Center was literally designed for such a project.

“Nim and I worked with architects and a play designer in setting up a facility that incorporates research directly into the space,” explains Klein. “We built this in so that the research is simply integrated into the flow of the day for the children.”

In the new environment, Klein and Tottenham will build on their existing research into children’s behavior by studying their underlying neurobiology of

development. “We’ll use functional imaging — MRI — as a safe and noninvasive way to look at brain development,” says Tottenham.

Returning to the idea of coaxing toddlers to sit still for an extended period of time, Tottenham settled on video as a distraction in order to proceed with an MRI. “If you show kids their favorite show while in the tunnel, you can get them to lie still,” she says. “We had the opportunity in the center to practice in models of an MRI so that they could get comfortable before we proceed with the actual imaging.”

The timing of the new research comes on the tail of the pandemic, during which toddlers and parents spent increased time together, potentially playing a role in the ultimate results. “Given the importance of parents in early life, it’s not surprising that parents’ well-being in a time of stress translates to toddler well-being, and vice versa,” says Tottenham.

When stress and loss is high, and toddlers don’t have a sound relationship with their parents, they’ll struggle. “The truth about young children,” adds Klein, “is that if they have what they need in life, they can rebound from stressful events.”

Five Years Bolder

Learning doesn’t stop after you’re no longer a student. For the past five years, Barnard students and faculty have engaged in a different kind of learning than the traditional route of continuing education. At the behest of students, in 2018, students and faculty collaborated to launch the annual Barnard Bold Conference.

A student-led event, Bold facilitates conversations between faculty, students, and staff, with the intention of continuing to strengthen teaching and learning. Support for the conference comes by way of the Center for Engaged Pedagogy (CEP), whose mission is to develop transformative, collaborative, and holistic approaches to teaching and learning, including assessment and curricular projects.

This year’s Barnard Bold Conference will be the first since the start of the pandemic to fully return to a live format, a fitting note as students and faculty mark the five-year anniversary of the event. CEP’s interim executive director, Melissa Wright, says that the format will feature a full day of on-campus conversation and learning and a keynote address from Bold’s creator, Shreya Sunderram ’19.

Last year’s event featured sessions on “Evolving Engagement: Reimagining Educational Experience” and “Examining Exams: A Reimagination of Traditional Assessments.” For 2023, students, faculty, and staff can all submit ideas surrounding teaching and learning. Recent proposals include sessions on digital humanities coursework, the “Undesign the Redline” exhibit, and ChatGPT (the controversial new AI writing tool), Wright says.

Annabelle Tseng, a Ph.D. candidate at Columbia, has been working with Bold since 2019, and this year will assist CEP in its support of the event. “The nice thing about the event is that it’s not about critiquing what isn’t working in the student/ faculty relationship, but about strengthening teaching and learning at Barnard and finding solutions that are more inclusive and welcoming,” Tseng explains.

The Bold sessions in previous years have served as student-led laboratories for exploring emergent teaching and learning topics with faculty, staff, and students within the Barnard community, according to Wright. For example, past sessions on grading and assessment informed the CEP’s development of the popular Alternative Approaches to Grading Workshop in June 2022. This was useful for expanding the department’s research base on rigorous and antioppressive grading practices as the College officially transitioned to P/F grading for two courses: the FirstYear Seminar and First-Year Writing.

Last year, students identified three areas to focus on and then selected topics within them. Support from CEP ranged from the logistical to the advisory. “We supported them as a sounding board on who to invite as panelists and what questions to ask them,” Tseng says. “It’s so nice to see how much students care for their instructors and each other and to help continue the work that was started a few years ago.”

As the live March event approaches, CEP, students, staff, and faculty will formulate the right mix of presentations, panel discussions, workshops, and collective brainstorming. Together, they’ll enrich the learning experience for students and faculty alike. B

PHOTO BY BEN ROLLINS

PHOTO BY BEN ROLLINS

At the beginning of the Fall 2022 semester, as students and their families returned to Spelman’s campus in Atlanta, they were welcomed at the entrance by a new face: Dr. Helene Gayle ’76, the College’s new president. Shaking blue pompoms, Gayle, who was clad in a Spelman T-shirt, jeans, and sneakers, greeted arriving cars with an exuberance that made clear she is the students’ biggest cheerleader.

For the public health leader and humanitarian, leading Spelman — considered the country’s premier undergraduate institution for women of African descent — is a natural evolution in her career. “I’ve been guided by my purpose and my passion. That has led me from one step to the next,” says Gayle, a physician who majored in psychology at Barnard and considered a career in that field. “I give a lot of credit to Barnard because it has such a history of women going into medicine. I got a broader exposure to that as a career.”

‘PURPOSE & PASSION’

Gayle realized practicing medicine was a way she could have a meaningful impact on people’s lives. “A lot of why I pursued medicine was really because of my passion for social justice and equity and being able to give back to communities that I had come from,” she explains of her career path from clinician to public health and social justice advocate.

That path for Gayle has included such key roles as serving as president and CEO of several major organizations, including one of the nation’s largest community foundations, the Chicago Community Trust, and the humanitarian organization CARE.

Gayle has spent over 30 years tackling global health issues, with a particular focus on HIV/AIDS and reproductive health, and served as the director of programs for organizations including the Centers for Disease Control and the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. In addition, she sits on the Advisory Council of the STEMM Opportunity Alliance, which aims to increase diversity, equity, and inclusion in STEMM (science, technology, engineering, math, and medicine) fields. Serving as Spelman’s current president is a fitting part of that trajectory.

by Sharon D. Johnson“We know that HBCUs [historically Black colleges and universities] have had such a huge impact on making a difference in the social mobility for African American communities,” Gayle explains. “At this point in my career, I want it to be about giving back to the next generation and to be at a school where the next generation looks like me.”

Although Barnard and Spelman maintain a long-standing student exchange program, students who look like Gayle were not in the majority during her undergraduate years. Still, she considers her time at Barnard instrumental to her vision and goals as president of Spelman. “I can’t say enough about the good fortune that I had to come to Barnard — to have been at a place where you get grounded in who you are, what it means to be a woman, and how to take your power with you. That is something so vital,” she offers. In a current social climate fraught with racial and cultural tensions, Gayle recognizes a particular necessity for Black women to have such sacred space. “At Spelman, there is an important place where young women of African descent can come to express their whole selves, where the issues that are key for them are not fringe issues but core issues.

In her new role as Spelman College’s 11th president, Dr. Helene Gayle ’76 builds on her success as a leader in global health to nurture the next generation of Black women

’85

It’s not the choice for everyone, but it is an incredibly empowering experience to be here.”

It is significant to be at a private college for Black women at a time when the existence of women’s colleges seems vulnerable. A 2021 Daily Beast article, “The Fight to Save Women’s Colleges From Extinction,” reported that several women’s colleges that year, including Mills, Judson, and Converse, were closing or transitioning to coed — casualties of low enrollment and reduced revenue caused by the COVID-19 health crisis, as well as markers of an 85% decline in women-only colleges since the early 1960s. Gayle understands the gravity of the situation particularly at a time when key women’s rights issues such as education, economic empowerment, and reproductive rights are facing legal challenges and rollbacks.

“If we look at what makes the biggest difference, we know that if women get an education, the trajectory for their life is so different. If they have economic empowerment, not only are they empowered, their families are empowered,” says Gayle. “I think women’s colleges are critical perhaps more today than ever because when a woman makes the choice to go to a women’s college, she’s also making a choice to invest in herself as a woman.”

In 1983, when Columbia College transitioned to coeducational admissions, there was some concern among Barnard students and administrators that applications and matriculation to Barnard would drop and that a consequential number of enrolled Barnard students might transfer. As an outcome of the negotiations between the Colleges, Barnard became more autonomous. Although Gayle graduated before these changes occurred, she

recognizes the impact on women who have had the option to attend Columbia instead.

“Women who choose Barnard today are making a very different choice about being in a place that absolutely believes, as a woman, you can do anything, you can achieve anything,” she asserts. “The same for Spelman, which [also] says that as a Black woman you can achieve anything, that [neither] your race nor your gender needs to be a barrier. It is still an important choice that [women] are making to invest in themselves.”

Perhaps one of the greatest challenges for a college president is convincing donors to invest in higher education. As reports in Higher Ed Dive and the Daily Beast have shown, fundraising can be more difficult for women’s colleges. The intersection of gender and race has the potential to make it that much more difficult for an institution like Spelman. “Everyone doesn’t necessarily appreciate why, in today’s age, a school that is race- and gender-based is still necessary. I don’t think that it is the only option in today’s world,” Gayle concedes. “But I think our enrollment numbers — which have tripled in the last decade — speak for themselves. At a time when college enrollment and applications are declining, they are actually increasing for HBCUs.”

A September 2022 segment of PBS Newshour reported that applications to HBCUs had increased almost 30%. “There is a need, and there is a niche,” Gayle emphasizes. “There is clearly a desire for young people to be in a place that speaks to who they are and has no bar on what the expectations are for them in the world.”

“A lot of why I pursued medicine was really because of my passion for social justice and equity and being able to give back to communities that I had come from.”

For Gayle, there is a social and historical imperative to HBCUs that intersects with what students need and want from higher education today. “Spelman, for over 140 years, has been educating women of African descent, starting out at a time when Black people were [emerging from] the period of enslavement and did not have opportunities,” explains Gayle. “The initial colleges were set up so that Black men had opportunities for education. At that time, it was a radical notion that Black women also should have the opportunity. Starting from that premise — that there is a right to education in an institution that values you for who you are — is critical.”

Equally critical to generating financial support is highlighting alumnae achievement and service. Among the notable women who’ve attended Spelman are Georgia gubernatorial candidate Stacey Abrams; novelist and poet Alice Walker; actress, director, and producer LaTanya Richardson Jackson; Walgreens Boots Alliance CEO (and one of the first Black women to serve as a Fortune 500 CEO) Rosalind Brewer; and Marian Wright Edelman, founder of the Children’s Defense Fund, who was Barnard’s Commencement speaker in 1985. This past November, Spelman renamed its admissions office in honor of film director Spike Lee’s grandmother Zimmie Reatha Shelton and mother Jacquelyn Shelton Lee, alumnae of Spelman classes 1929 and 1954, respectively. “And there are a lot of names you’ll never hear,” Gayle adds, “but when I travel the country, I am told all the time, ‘Our best workers, our best staff, are the young women

who got a Spelman education.’ So it speaks for itself. From the arts to the sciences to business and all, Spelman produces incredible women.”

As president and role model for the next generation of Spelman women, this Barnard woman, who purposely imbued her STEMM career with social justice, is only just getting started. “I feel privileged to have had a long and wonderful career,” Gayle reflects, adding with a chuckle, “It’s now my time to figure out how to give the kind of opportunities that I’ve had to young Black women so that they can go on and I can retire.”

Until that time comes, Gayle is focused on helping her students broaden their visions and follow their passions as she did. “That’s why I’m proud to be at a liberal arts college,” she says. “Whether you decide to go into a STEMM career or an arts career, it’s important to have the basic foundation of a liberal arts background that allows you to continue to be a lifelong learner. It should be the cornerstone to the specializations we keep trying to drive young people into, that we keep trying to have them decide from birth. Let them learn to learn and then think about how to use that.” B

“I think women’s colleges are critical perhaps more today than ever because when a woman makes the choice to go to a women’s college, she’s also making a choice to invest in herself as a woman.”

A Community of Crosswords

Three Barnard alums puzzle out the grid

by Tom StoelkerToday, sitting down with a crossword, especially if you do it on paper and in ink, evokes a certain sophistication and smarts. But there was a time in the early part of the last century when these puzzles, though all the rage, were considered by many to be a colossal waste of intellect. The crossword was also considered “a threat to the family unit” — wrote one of The New Yorker ’s puzzle constructors, Anna Shechtman, in the December 27, 2021, issue — due in no small part to the fact that the earliest innovators were not just women, they were “New Women,” who, it was feared, could shatter what remained of Victorian mores. These days, the analog pastime has caught up to modern times, engaging a more inclusive audience that fosters community, and fun, for both solvers and creators. Here, we present puzzles and musings on the ubiquitous American hobby by three Barnard cruciverbalists: Rebecca Gray ’13, Rebecca Goldstein ’07, and Gustie Owens ’22. Enjoy.

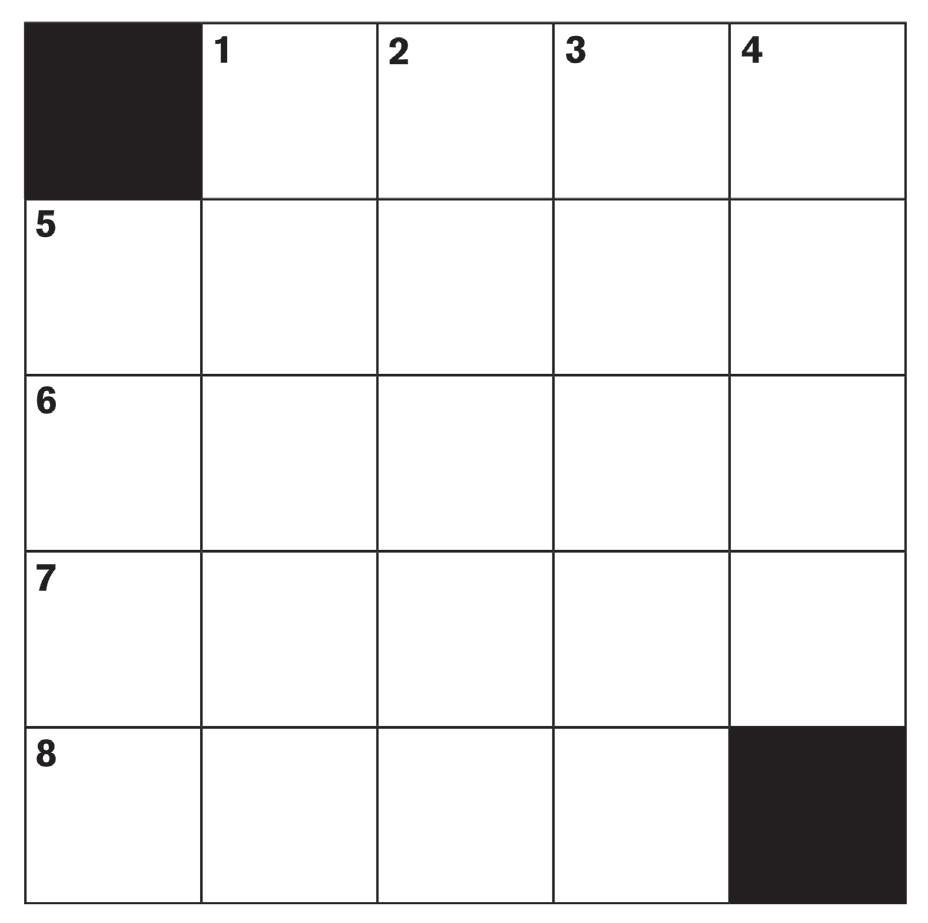

ACROSS

1 The College’s home for intersectional feminist analysis

5 They tried to make Amy Winehouse go here

6 Concert venue

7 “______ no?” (2 words)

8 Envelope abbr.

DOWN

1 French hat

2 Top surgery target

3 Talked and talked

4 The College’s radio call sign

5 Private dating app for celebs

Rebecca Gray ’13

Rebecca Gray is a writer, educator, and musician living in Seattle. They regularly contribute crossword puzzles to Barnard Magazine.

How did you start writing crossword puzzles?

I am a percussionist; that’s my first art form. I am also really into math and figuring out how things work. But there was a particular time I was staying with relatives who had strange rules and I couldn’t make music. I was like, “Oh, I have a piece of paper and a pencil, and I like shapes and words. I’ll just focus on making crosswords.” I would just freehand with a straightedge and a pencil, create a grid, and start writing out words that I liked. It was super chaotic and looked like a psychopathic murderer writing iterations of letters and words that make no sense. But it was fun and a good way to try to figure out how the puzzles worked.

What inspires you?

I watched this documentary from 2006 called Wordplay. It’s deliciously nerdy, but within that movie it shows how to make a puzzle. I felt like I learned some rules, and I began to experiment with themes, like female protagonists of books, such as Virginia Woolf’s Orlando and Daphne du Maurier’s gothic novel Rebecca — which was funny because it’s my name. And Beezus and Ramona [from Beverly Cleary’s 1955 children’s novel]. So that’s kind of how it started. Now I use this free, very bare-bones software called Phil.

Can crosswords foster community?

The first crosswords were really focused on current events. If you weren’t reading that week’s New York Times, you would be lost. But I love community. I love ways that we can help each other. We shouldn’t have to know everything that’s happening in the world all at once, but if we’re a part of the community, it’s really nice to know that we can understand what’s going on through puzzles. Then there are deeply general puzzles, like USA Today puzzles. They are trying to appeal to millions of people, and that’s great, but niche puzzles are great too. I put stuff in my puzzles that not everyone will get. Hopefully there’s enough material in there that people relate to — that’s how you do community. But I think my last puzzle for Barnard Magazine, I kind of went off the deep end with Rage Against the Machine.

What is the perfect setting to enjoy crossword puzzles?

Airplane, for sure. It’s a super-focused space that has a finite ending. It makes your brain really work, and that’s kind of yummy.

Crossword answers on page 76.

Rebecca Goldstein ’07

Rebecca Goldstein lives in the San Francisco Bay Area with her wife, Ariela. She holds a doctorate in pharmacology and now leads a small group supporting immuno-oncology drug discovery efforts at Merck.

How do you construct a themed puzzle?

Almost all the puzzles I write are themed, meaning that the longest entries in the puzzle are unified by a common idea or element of wordplay. The themes are often tied together by a final entry known as a revealer. I’m mostly inspired by phrases I come across in the wild — in conversation, in television dialogue, and even in solving crossword puzzles — that seem like potential revealers or theme entries. I will then set out to find matching entries. For example, as I became more and more consumed with constructing crosswords, I remarked to my wife that it felt like I had CREATED A MONSTER, which I immediately recognized as a perfect revealer for a theme set with entries containing hidden monsters, like LIN(T ROLL)ER and PRI(DE MON)TH. That idea became my first New York Times crossword acceptance.

Can a crossword be subversive?

Yes, absolutely. The New York Times crossword is famously known for needing to pass “the breakfast test.” In other words, would the content of the puzzle be acceptable for discussion over the family breakfast table? That can be limiting. There is a burgeoning indie scene of crosswords that embraces more provocative content than mainstream publishers will allow. There are numerous constructor blogs, subscription-based crosswords like the American Values Crossword, and fundraising puzzle packs like “These Puzzles Fund Abortion Too” and “Queer Qrosswords.”

The earliest innovators of the crossword were women. How does that resonate with you?

Despite strong female influence in the birth of crosswords, for decades, crossword puzzles have skewed largely toward white cis-het male normativity, which can be alienating for new solvers who don’t see themselves represented in the puzzle. As the voices of new constructors and solvers have gathered steam, the larger crossword community has grappled with the growing demand for increased representation in puzzles. In mainstream publications, editors Patti Varol of the Los Angeles Times, Erik Agard of USA Today, and David Steinberg of Universal Crossword have all made tremendous strides in increasing the diversity of constructors, editors, and puzzle content. In the indie world, the Inkubator only publishes puzzles written by women and nonbinary people. The way I see it, not everyone will enjoy every puzzle they encounter, but the more diversity that exists in puzzles, the more likely everyone is to find something they see themselves represented in, and I’m all for it.

What is the perfect setting to enjoy a crossword?

I solve for speed, so for me, a silent room with no distractions.

ACROSS

1 With 1-Down, blue for the Class of 2023 (and 2007!)

6 Simple skateboard trick

7 “See ya!”

8 ___ Phi Beta

9 Word with gem or form

DOWN

1 See 1-Across

2 Animal wearing pajamas, in kids’ songs

3 Fit for a queen?

4 Prolonged battle

5 Skincare components

ACROSS