OIL AND GAS IN NORWAY

an introduction

An introduction

Advokatfirmaet BAHR AS www.bahr.no

March 2025

Introduction

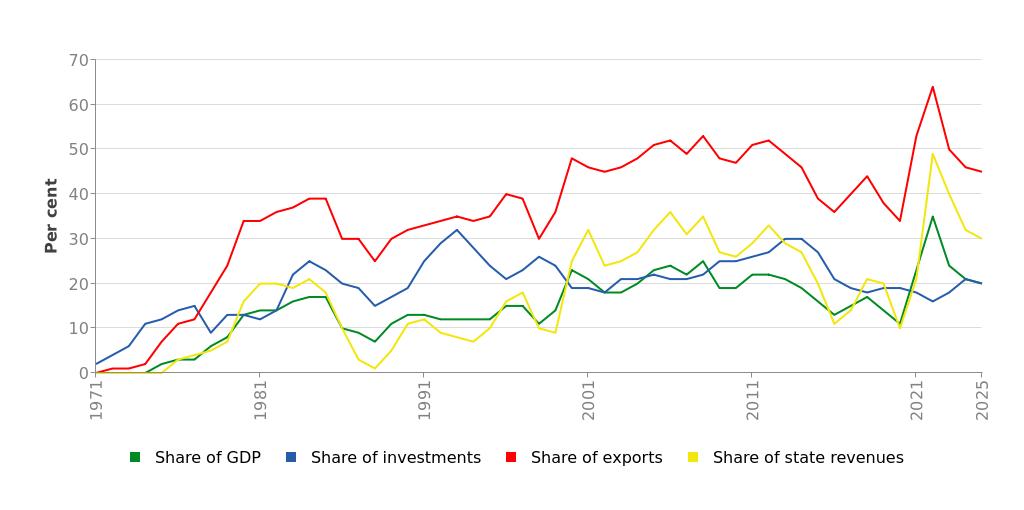

The petroleum industry is Norway's largest industry measured in terms of value creation, government revenues, investments and export value and a cornerstone for Norwegian social and economic development for the last decades. Norway is a small player in the global crude market with production covering about two per cent of the global demand. However, Norway is the third largest exporter of natural gas in the world and Norway supplies about 34% of the EU gas demand. In 2022, Norway replaced Russia as the European Union’s (the “EU”) leading natural gas supplier. Nearly all oil and gas produced on the Norwegian Continental Shelf (the “NCS”) is exported, and combined, oil and gas equal about half of the total value of Norwegian export of goods. For this reason, oil and gas represent the most important export commodities for the Norwegian economy. Government income is secured by taxation and direct participation in the petroleum activities.

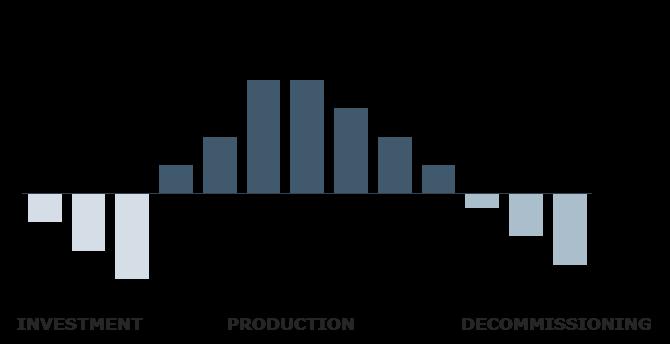

Macroeconomic indicators for the petroleum sector, 1971-2025:

Source: www.norskpetroleum.no

Since production started in 1971, oil and gas have been produced from a total of 125 fields on the NCS. At the end of 2024, 94 fields were in production: 69 in the North Sea, 23 in the Norwegian Sea and 2 in the Barents Sea. In 2024, 2 new fields were set in production. At the year-end of 2024, 23 development projects were ongoing on the NCS. Many of the producing fields are ageing, but some of them still have substantial remaining reserves. Moreover, the resource base in these fields increases when small discoveries in the area are tied into existing infrastructure. Petroleum resources on the NCS have been estimated to 15.6 billion standard cubic metres of oil equivalents. Around 56% of the total discovered and estimated undiscovered petroleum resources have so far been produced and sold.

Recent developments and key events on the NCS

Energy security on the global agenda

Following Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine on 24 February 2022, the EU launched RePowerEU, a plan to make Europe independent from Russian fossil fuels by 2027.

Before the Russian invasion of Ukraine, EU relied on Russia for around 40% of its natural gas and 27% of its oil consumption. In 2023, import of Russian gas was down to only 15%. Norway and the U.S. have become the EU’s largest gas suppliers, providing 34% and 20% of EU gas imports respectively in March 2024.

The importance of energy security has been a key topic on the global agenda for the last years The energy prices rose dramatically in 2022, where the price of natural gas in Europe hit an all-time high in 2022 and remained high in 2023 and 2024. As Norway already is a large supplier of oil and gas, and the demand for fossil fuels is increasing, Norway is likely to be important in securing energy supply to Europe also in the coming years.

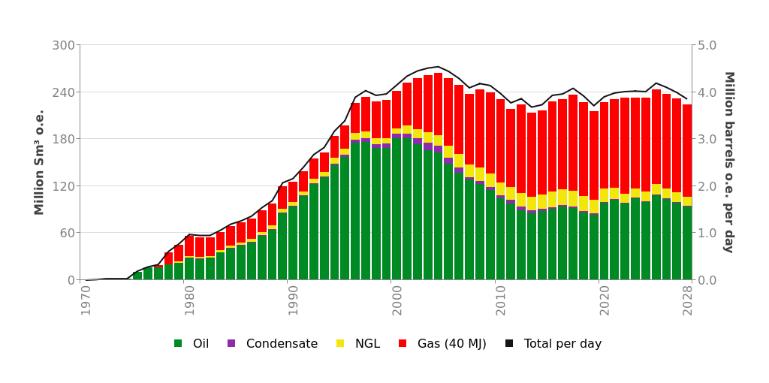

Historical and expected production in Norway, 1970-2028:

Source: www.norskpetroleum.no

High activity level in 2024

Gas production from the NCS reached a record-high level in 2024. A total of 124 billion standard cubic metres (Sm3) was sold. In comparison, the previous record of 122.8 billion Sm3 of gas was set in 2022. The high production in 2024 was caused by high regularity on the fields and increased capacity following upgrades in 2023.

In 2024, overall production reached about 240 million standard cubic metres of oil equivalent (MSm3 o.e.). This is the highest level since 2009. Production from the Troll and Johan Sverdrup fields in the North Sea contributes about 37% of overall production from the NCS.

In 2022, 13 Plans for Development and Operations (“PDOs”) were delivered to the Ministry of Energy (“MoE”), as well as several plans for projects where the aim is to increase the production close to existing fields or extend their lifetime. These plans were approved in 2023. Following such wave of PDO’s, only one PDO was delivered in 2023. In 2024, PDOs for the Eirin field, located in the Sleipner area in the North Sea, and the Bestla Field, located in the Oseberg area, were approved. Two new fields came into production in 2024: Tyrving and Hanz, both in the North Sea.

The high number of PDO’s submitted in 2022 was driven by the temporary tax regime adopted in 2020. The tax regime intended to stimulate activity and to preserve the Norwegian service industry, which employs a significant number of persons.

Menon Economics has estimated the aggregated investments under the temporary tax regime to approximately NOK 440 billion. According to a report by Rystad Energy, these investments are expected to yield revenues for the State in the vicinity of NOK 747 billion (in 2023 monetary values).

Considering the high activity, the temporary tax regime can be said to have been successful and worked as intended. However, the temporary tax regime has also been heavily criticised as being too favourable, particularly considering the high petroleum prices in the recent years.

2024 saw a higher exploration activity than in 2023. In 2024, 42 exploration wells were drilled, and 16 new discoveries were made on the NCS. The preliminary overall estimate for these discoveries is 38 million Sm3 of recoverable oil equivalent. In the 2024 Awards in Predefined Areas (“APA”) round awarded in January 2025, 20 companies were awarded a total of 53 licenses, compared to 62 in 2023, consisting of 33 in the North Sea, 19 in the Norwegian Sea and 1 in the Barents Sea.

The Norwegian Offshore Directorate expects overall production from the NCS to decline in the late 2020’s. How steap this decline will be, will depend on several factors. To slow this decline and to uphold production, more investments must be made, both in fields, discoveries, infrastructure and technology, as well as maintaining exploration activity.

The NCS still contains large undiscovered oil and gas resources. These resources can provide a basis for high levels of production, export and value creation for many years to come. However, to maintain a high activity level, these resources first need to be found. Finding these resources will require more exploration, both in frontier areas and close to the infrastructure already in place.

Participants on the NCS

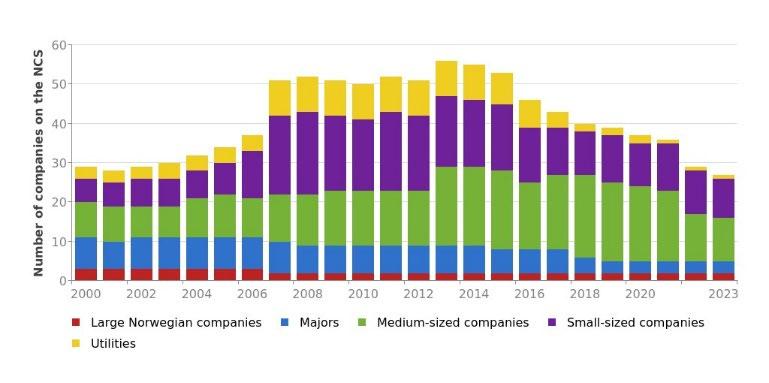

Following the introduction of several new policies in the first decade of 2000, the number of new participants to the NCS substantially increased and the combined number of active companies trended upwards. In the last 10 years, that trend has shifted, and the number of participants has been reduced from 56 in 2013 to 25 active exploration and production companies today. Over the past decade, several major and utility companies have either exited the NCS or shifted to indirect ownership positions. This have laid the foundation for an active M&A market and the growth of several midsized companies, which have developed to be sizeable and important companies through acquisitions and organic growth. Mid-sized companies now hold a relatively larger share of production and are active within exploration, new developments and in the application and award of new production licenses.

Numbers of companies on the Norwegian continental shelf 2000-2023, categorized by size:

Source: www.norskpetroleum.no

The Norwegian State’s takeover of gas infrastructure on the NCS

The Norwegian gas infrastructure is the world’s largest offshore network, as it comprises of around 8,600 kilometres of pipelines. Most of the gas transportation infrastructure is owned through the partnership Gassled. On 28 April 2023, the MoE published a press release informing that the Norwegian State intends to exercise its right to take over key gas transportation infrastructure, upon the end of the licence period and that the State wants to acquire full ownership of the central parts of the Norwegian gas transportation system.

On 12 November 2024, MoE announced that it had entered into purchase agreements with seven companies to acquire interests in Gassled and other key parts of the Norwegian gas infrastructure system The agreements were made with 1 January 2024 as an effective economic date. The total consideration was NOK 18,1 billion (subject to adjustments). Closing was subject to, among other things, the approval of the Norwegian Parliament (Stortinget), and took place 23 December 2024

Climate litigation and the oil & gas sector

Globally, judicial actions addressing climate change are on the rise, with cases before both domestic and international courts. These legal challenges, frequently based on human rights arguments, are increasingly influencing the framework of climate accountability. The industry should anticipate increased legal scrutiny concerning environmental impact assessments, governmental approvals, and compliance with international climate agreements.

In Norway, as is the trend gobally, there has been an uptick in climate litigation. A notable example occurred in 2020 when the Supreme Court rendered a decision in a Climate Case brought forth by the non-governmental organisations Greenpeace Nordic and Nature and Youth against the Norwegian State. The plaintiffs questioned the validity of the award of exploration and production licences in the Barents Sea in the 23rd licensing round. The Court determined that the award did not infringe upon Section 112 of the Constitution, which guarantees the right to a healthy environment, nor were any other human rights obligations breached. On the argument that

procedural errors were made, the Supreme Court dismissed the claim and ruled that it did not constitute a procedural error that combustion emissions associated with petroleum produced from possible future fields (so-called Scope 3 emissions) were not assessed in the environmental impact assessment related to decision to open the areas awarded in the concession round. The Supreme Court noted that the net effect of Scope 3 emissions from Norwegian oil and gas production is a complicated and disputed matter, and that the net effect of Norwegian petroleum production could be positive, neutral or negative depending on the assumptions. As such, the effects from the combined emissions from Norwegian oil and gas production in general should be assessed together. It was for the MoE and government to decide whether these matters should be assessed as part of the general petroleum policy, or as part of the specific impact assessment. It was referenced that a broad political majority on several occasions has rejected proposals to reduce or stop Norwegian oil and gas production by reference to the global CO2 emissions and that the matter has been thoroughly debated and assessed. The Supreme Court noted that the climate effects of the petroleum production will be continuously politically assessed - and will be subject to an environmental impact assessment in the event of an application for a PDO. Thus, the Court concluded that no procedural error was present. This Supreme Court ruling is currently under review by the European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR), with a decision pending as of February 2025.

Following the Supreme Court ruling in Norway, Greenpeace Nordic and Nature and Youth initiated a second climate case, this time challenging the State's approvals of the PDO for three specific fields. On 18 January 2024, the Oslo District Court invalidated the State's PDO approvals for the Breidablikk, Yggdrasil, and Tyrving fields. The Court identified a procedural error, noting that the assessment of Scope 3 emissions had not been subjected to the formal requirements of an environmental impact assessment, as mandated by the EU Environmental impact assessment directive (2011/92/EU) and the Petroleum Regulations, interpreted in light of Section 112 of the Norwegian Constitution. The Court concluded that this procedural oversight could have potentially influenced the decision to approve the PDOs, leading to their invalidation. Additionally, the District Court issued a preliminary injunction prohibiting the State from awarding further licences based on the assumption of a valid PDO for these fields. The Norwegian State has appealed both the ruling and the injunction, advancing the case to the Court of Appeal.

The appeal process has divided the case into three parts. Initially, the Court of Appeal separately assessed the preliminary injunction in a hearing in the fall of 2024, ruling in favour of the State and overturning the injunction. This decision has been appealed to the Supreme Court, with a hearing scheduled for 18 and 19 March 2025. The main issue, concerning the invalidity of the PDO decisions, is set to be heard by the Court of Appeal later in 2025. Meanwhile, the State has sought an advisory opinion from the EFTA Court on the interpretation of the EU's Environmental Impact Assessment Directive, with a hearing held in December 2024 and an opinion pending as of February 2025. Notably, the oil companies involved in the affected production licences are not parties to the court case, meaning the ruling directly impacts only the State, leaving the PDOs valid in relation to the oil companies.

In the UK, recent court decisions have similarly interpreted the EU's Environmental Impact Assessment Directive. The UK Supreme Court's decision in Finch v. Surrey County

Council affirmed that the Directive and therefore UK law, requires an assessment of combustion emissions before granting permission for oil and gas projects. This principle was further reinforced by the Scottish Court of Session on 30 January 2025. The Scottish court invalidated the development and operation permits for the Rosebank and Jackdaw fields due to insufficient consideration of scope 3 emissions. As a result, the operators must reapply for permission to develop the fields, and an immediate production ban has been imposed.

In a broader European context, the ECtHR has recently delivered judgments in cases concerning the impact of climate change on fundamental human rights and state responsibility. In the most notable case, Verein KlimaSeniorinnen Schweiz and Others v. Switzerland, the ECtHR found that Switzerland had violated the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR) article 8 by failing to provide adequate protection against the severe negative effects of climate change on individuals' lives and well-being. The court emphasized that Article 8 of the ECHR includes the right to effective state protection against such effects. This decision could have implications also for Norway, as it underscores the importance of an appropriate regulatory framework, a national greenhouse gas emissions budget, and the pursuit of emissions reduction targets.

Energy transition and new industries

The transition to a carbon neutral society has wide implications across all industries and fuels the development of new industries.

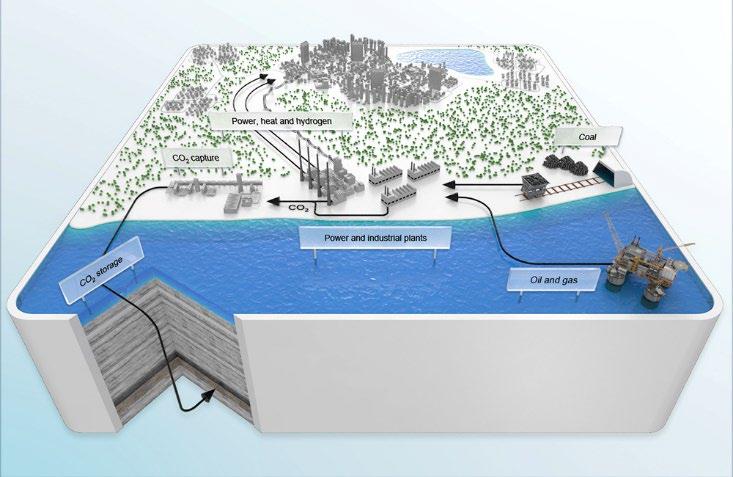

To succeed with the goal of a carbon neutral society, the capture, utilisation and storage of CO2 (“CCUS”) is required. The theoretical storage capacity on the NCS exceeds 80 billion tonnes of CO2, the equivalent of about 2000 years of Norwegian CO2 emissions at current levels.

Source: Illustration CCUS, Gassnova, www.norskpetroleum.no

Prior to 2024, the MoE had awarded 7 permits for injection and storage of CO2 on the NCS. In 2024, two licensing rounds were held, and in September, four additional licences were awarded, all located in the North Sea. Two licences were offered to Equinor ASA,

while the other two licences were offered to one group consisting of Vår Energi ASA, OMV (Norge) AS and Lime Petroleum AS, and one group consisting of Aker BP ASA and PGNiG Upstream Norway AS.

In total, 11 licences have been awarded to 13 companies; 1 exploitation licence and 10 exploration licences. Offers for two additional licences were issued in December, with awards expected in 2025.

An important initiative that has paved the way to progress CCUS was the approval of funding for “Longship” in 2020, being a full-chain carbon capture, transportation, and storage project, including the project Northern Lights. Northern Lights is a project which intends to transport captured and liquified CO2 by ship from the Eastern part to the Western part of Norway, and thereafter by pipeline to an offshore storage location subsea in the North Sea for permanent storage. The development plan for the Northern Lights project, the storage part of the Longship carbon capture and storage project, was approved by the MoE in March 2021 and in 2022.

Recent developments include that, on 26 September 2024, the Northern Lights receiving terminal formally opened in Øygarden. This means that the world’s first commercial facility for transport and storage of CO2 across national borders is now complete and ready to receive and store CO2. Start-up is scheduled for 2025.

Further, on 27 January 2025, as part of the Longship-project, the MoE announced that the Norwegian government and Hafslund Celsio had signed a grant agreement to support carbon capture and storage at the Klemetsrud waste-to-energy plant in Oslo. The project aims to capture 350.000 tons of CO2 annually, that will be stored permanently in the Northern Sea. The project marks an important milestone in the Norwegian government’s commitment to carbon capture and storage through the Longship project.

Several projects for the electrification of NCS installations are underway, driven partly by the cost of CO2 emissions and the climate targets set by the oil and gas industry and the Climate Act. Today, the fields Johan Sverdrup, Edvard Grieg, Ivar Aasen, Gina Krog, Ormen Lange, Snøhvit, Troll A, Goliat, Valhall and Martin Linge are supplied with power from shore. This means that third-party fields connected to these installations are also electrified and produce with a lower carbon footprint. Additionally, the fields Sleipner and Gjøa are partially electrified. Furthermore, the onshore facilities Kårstø, Kollsnes, Melkøya LNG, and Nyhamna (including the subsea installations at the Ormen Lange field) receive power entirely or partially from the electricity grid. Power from onshore is also under development for the installations at the Draugen, Njord, Troll B and C, Oseberg Field Center, and Oseberg South fields.

In December 2022, the MoE received plans for increased gas production from Snøhvit and electrification of Hammerfest LNG on Melkøya from Equinor ASA, Petoro AS, TotalEnergies EP Norge AS, Neptune Energy Norge AS and Wintershall Dea Norge AS, which is called “Snøhvit Future”. In August 2023, Equinor ASA and the Snøhvit partners received approval from the MoE to proceed with the project, which has been subject to a lot of public debate. The electrification of the facility is planned to 2030.

Electrification of oil and gas installations has become an increasingly debated topic as domestic electricity prices onshore rose sharply during 2022, and a deficit in domestic renewable electricity production is expected within the next few years.

In November 2022, the first turbine in the Hywind Tampen floating offshore wind farm started its power production, delivering power to the Gullfaks A platform in the North Sea. As of August 2023, Hywind Tampen was in full operation, supplying Gullfaks and Snorre with power from offshore wind.

Additional floating and bottom fixed offshore wind farms are expected to be developed over the next 7 to 10 years. After the opening of the areas Utsira Nord and Sørlige Nordsjø II in 2020, the government announced the rules for award of acreage for one 1.5 GW capacity project on Sørlige Nordsjø II and a qualitative award process for the award of three projects up to 1.5 GW (in aggregate) on the Utsira Nord area in March 2023. The announcement was later updated on 17 October 2023.

On 20 March 2024, it was announced that Ventyr SN II AS won the auction for the allocation of a project area for offshore wind in Sørlige Nordsjø II, with a winning bid of 115 øre/kWh. Ventyr SN II AS is owned by Parkwind (Belgian) and Ingka (the Ikea group’s investment company). The contract between the Norwegian state and Ventyr SN II AS was signed on 17 April 2024. The wind farm is expected to be operational in 2030.

For Utsira Nord, the three project areas will be awarded after a competitive process based on qualitative criteria, however, there will not be a prior pre-qualification process as with Sørlige Nordsjø II. The plan is that the project with the highest score will be awarded its preferred area, with the project with the next best score being awarded its preferred area of the two remaining areas, and the third best project being awarded the last remaining area. The MoE is currently in the process of notifying a common model for state aid for Utsira Nord and the areas suitable for floating offshore wind in the award round of 2025.

The regulatory framework

The Norwegian Petroleum Act of 1996 (the “Petroleum Act”) sets out the main regulatory framework for petroleum activities on the NCS. The Petroleum Act is based on the principle that all petroleum deposits on the NCS are owned by the Norwegian State, and that the State can grant production licences allowing others to explore for and produce petroleum. Governmental control is further exercised through the requirement of approvals in all phases of petroleum activities, from gathering of seismic data and exploration drilling, to development, operation and decommissioning of oil installations, as well as approval for the transfer of already granted production licences. The Petroleum Act is supplemented by other legislations specifically relating to petroleum activities, such as the Petroleum Tax Act of 1975, as well as general legislation relevant to petroleum activities such as the Working Environment Act of 2005 and the Pollution and Waste Act of 1981.

In addition, there is a significant volume of secondary regulations concerning different aspects for petroleum activities.

The main regulatory bodies and State participation in petroleum activities

The main regulatory body is the MoE, which has authority over most parts of the Petroleum Act including ownership regulations and licensing rounds. Some of these functions are delegated to the Norwegian Offshore Directorate. Major development projects and issues of fundamental importance must be approved by the Norwegian Parliament. The Ministry of Finance has authority in petroleum tax matters. The Norwegian Ocean Industry Authority is responsible for safety and HSE matters.

The Norwegian State has substantial holdings in production licenses on the NCS through the State’s Direct Financial Interest (“SDFI”). The formal licensee for the SDFI assets is Petoro AS, a company wholly owned by the State. In addition, the State participates through its ownership interests in Equinor ASA and Gassco AS. The latter is a company wholly owned by the State which is the operator of the comprehensive gas transportation system on the NCS. The responsibility for managing the State’s direct and indirect participation in the petroleum activities through SDFI/Petoro and Equinor lies with the Ministry of Trade, Industry and Fisheries – who also manage the State’s ownership interest in other entities such as DNB, Norsk Hydro and Yara.

Petroleum activity requires a production licence

Companies wishing to produce petroleum on the NCS must hold a production licence, providing certain exclusive rights to perform petroleum activities within the geographical area defined by the production licence

Production licences can be awarded to existing oil companies on the NCS, or to new entrants that are prequalified to hold such licences. The general policy is that petroleum activities must be carried out by entities that are able to contribute to the Norwegian petroleum industry beyond just financial participation, and that the activities are carried out in an efficient, competent, and responsible manner. Therefore, licence awards and prequalification require that the company can demonstrate sufficient technical, financial and Health, Safety and Environment (“HSE”) skills and resources. The prequalification procedure for new entrants typically takes up to half a year. Guidelines for pre-qualification are found on the web page of the Norwegian Offshore Directorate.

Licensing rounds

Production licences are awarded through licensing rounds. There are two different kinds of licensing rounds on the NCS. There is an annual system of Awards in Predefined Areas (“APA”) in mature parts of the NCS. The APA rounds were originally intended to ensure that areas close to existing and planned infrastructure are available to the industry before existing infrastructure shuts down. Over time, the APA area has been expanded and today the APA area comprises most of the open, accessible exploration area on the Norwegian continental shelf. In addition to the APA system, ordinary licensing rounds are held - normally every second year (although the current government have stated that no such round will be initiated in this parliamentary term, as the 26th licensing round has been postponed until 2025). The ordinary rounds focus on frontier areas that are less explored and where less existing infrastructure has been built.

The MoE awards production licences based on the applications submitted. Relevant, objective, non-discriminatory and announced criteria form the basis for these awards. Applicants can apply individually or as a group.

New production licences are awarded to a group of companies, that each will hold a participating interest in the licence. The licence grants the participants exclusive rights to surveys, exploration drilling and production of petroleum within the geographical area covered by the licence. The licensees become the owners of the petroleum that is produced, with each licensee being entitled to a portion of the petroleum corresponding to their participating interest in the licence.

Production licences are valid for an initial period (exploration period) that can last for up to ten years. During this period, the work program determined by the licence must be carried out, typically consisting of geological/geophysical surveys or reprocessing, exploration drilling and/or submittal of a PDO. If all the licensees agree, the production licence can be relinquished when the work commitment has been fulfilled. Licensees having satisfied the work commitment can demand that the production licence is extended for a period which typically is 30 years but may be up to 50 years in special circumstances.

The production licences are registered in the Petroleum Registry which is an official and publicly available register that among other records ownership and encumbrances. Production licences can be mortgaged upon application and approval from the MoE.

Plans for Development and Operation (PDO)

If the licensees determine that it is commercially viable to develop a discovered field, the development shall be done in a prudent manner. The licensees are responsible for the development of new projects, but the development is subject to approval from the authorities. The approval is provided on the background of a PDO submitted to the MoE for approval. PDO’s for large and/or particularly important projects are presented to Parliament before the MoE’s approval. An important part of the PDO is an impact assessment which is submitted for consultation to various bodies that could be affected by the specific development. The impact assessment shall assess how the development is expected to affect the environment, fisheries, and society in general. The processing of this assessment and the PDO itself is intended to ensure that the projects are prudent in terms of resource management, and that the consequences for other public interests are acceptable. The impact assessment is compulsory unless the licensees can document that the PDO is covered by a relevant existing impact assessment. The MoE has expressed that the impact assessment shall include an assessment of the financial climate risks associated with the development. This entails an assessment of the economical profitability of the development based on future oil prices in a market/revised policy scenario compliant with the goals of the Paris Agreement. Furthermore, following up on the Supreme Court ruling in 2020 in the “climate lawsuit”, the MoE will as part of its approval process include an assessment of the climate effect of emissions from both production and the use of petroleum produced from the field (Scope 3 emissions). The adequacy of this procedural change is presently subject to judicial review, see the above section on climate litigation.

The petroleum activities shall be conducted in a prudent manner to ensure that a high level of HSE can be maintained and developed throughout all phases, in line with the continuous technological and organisational development. The licensees are responsible for pollution without regard for fault. This is referred to as strict liability.

Joint Operating Agreements

The licensees form a joint venture that is responsible for the petroleum activities within the licence area. The licensees are required to enter into a Joint Operating Agreement (“JOA”) which regulates the rights and obligations for the joint venture within the specific licence. The JOAs are standardized by a format that the MoE requires all licensees to use. The MoE nominates one of the participants in the licence as the operator, which will be responsible for the operational activities authorised by the licence. Major decisions are made by the management committee where all licensees are represented and have voting rights according to voting rules set out in the agreement for petroleum activities. Normally, a decision is made by the management committee when at least two of the participants that jointly represent at least 50% of the participating interest vote in favour of a proposal. The participants in the licence have joint and several liability for the obligations and liabilities arising out of the licence.

Licensees are required to provide a Parent Company Guarantee

The Petroleum Act section 10-7 gives the MoE the right, at any time, to demand adequate security for holders of production licences on the NCS. The authority pursuant to section 10-7 is quite wide with regard to timing and the nature of the security that can be required. However, in practice the MoE requires licensees to provide an unlimited Parent Company Guarantee (“PCG”) for the benefit of the Norwegian State to secure all obligations in relation to the petroleum activities. The format and wording of the parent company guarantee is based on a standard template. This standard form is non-negotiable and is kept in a brief format. So far there have been no instances where the guarantee has been used in practice, and there are therefore several issues where the interpretation is unclear. For instance, it is debated whether other participants in a licence can draw on the guarantee if another partner in the licence defaults on its obligations.

The main policy is that the MoE will require that the parent company guarantee is provided by the ultimate parent company of the licensee. A company is considered a parent company if the company, directly and/or indirectly, owns or controls more than 50% of the licensee. Thus, a company owning and/or controlling less than 50 % will normally not be required to issue a PCG. There are examples where the parent company guarantee has been issued by entities within a group that is not the ultimate parent company. For corporate transactions, the current policy of the MoE is to return parent company guarantees if a shareholder ceases to have more than 50% of the shares in the licensee.