Inherited.

Creative Space: Alex O’Connor

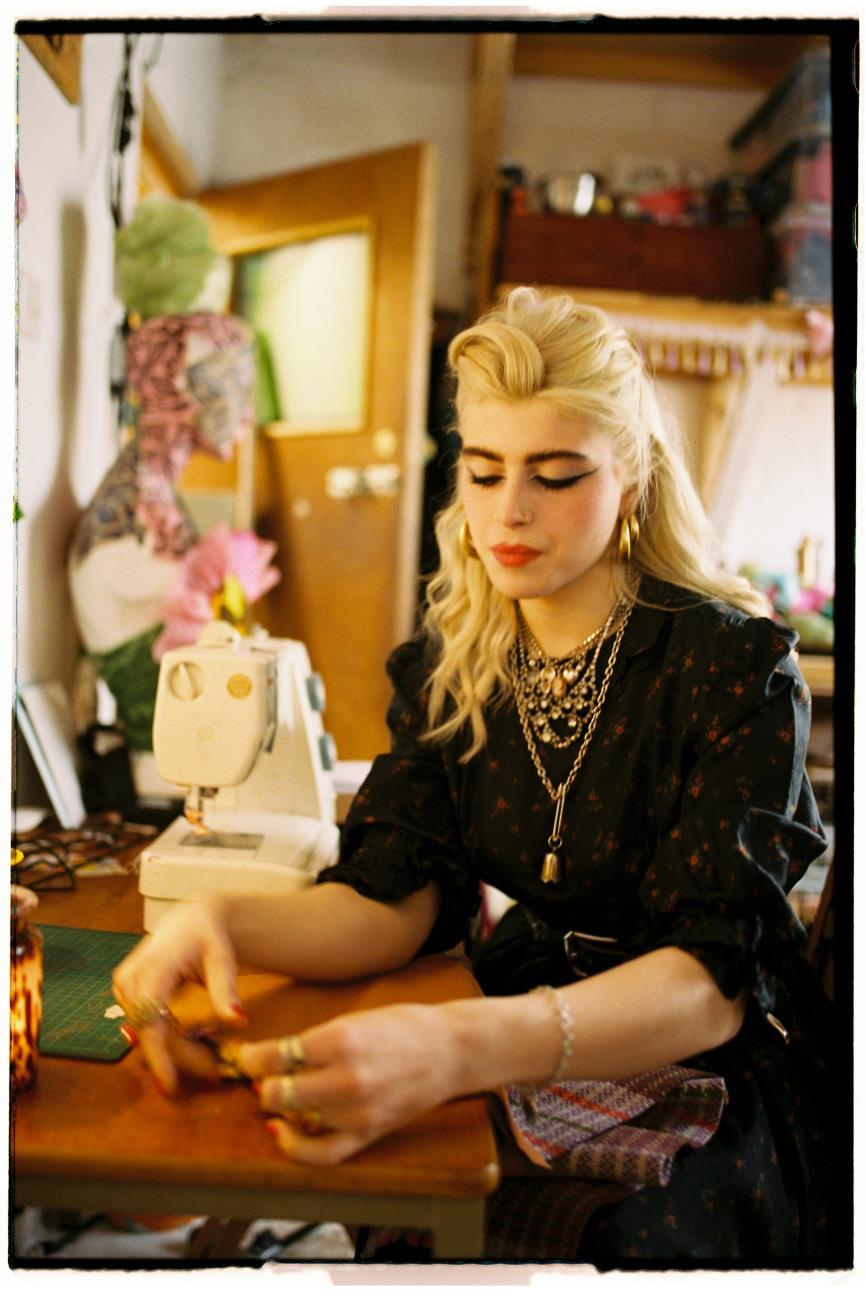

An interview with Molly Brennan of RugistheDrug

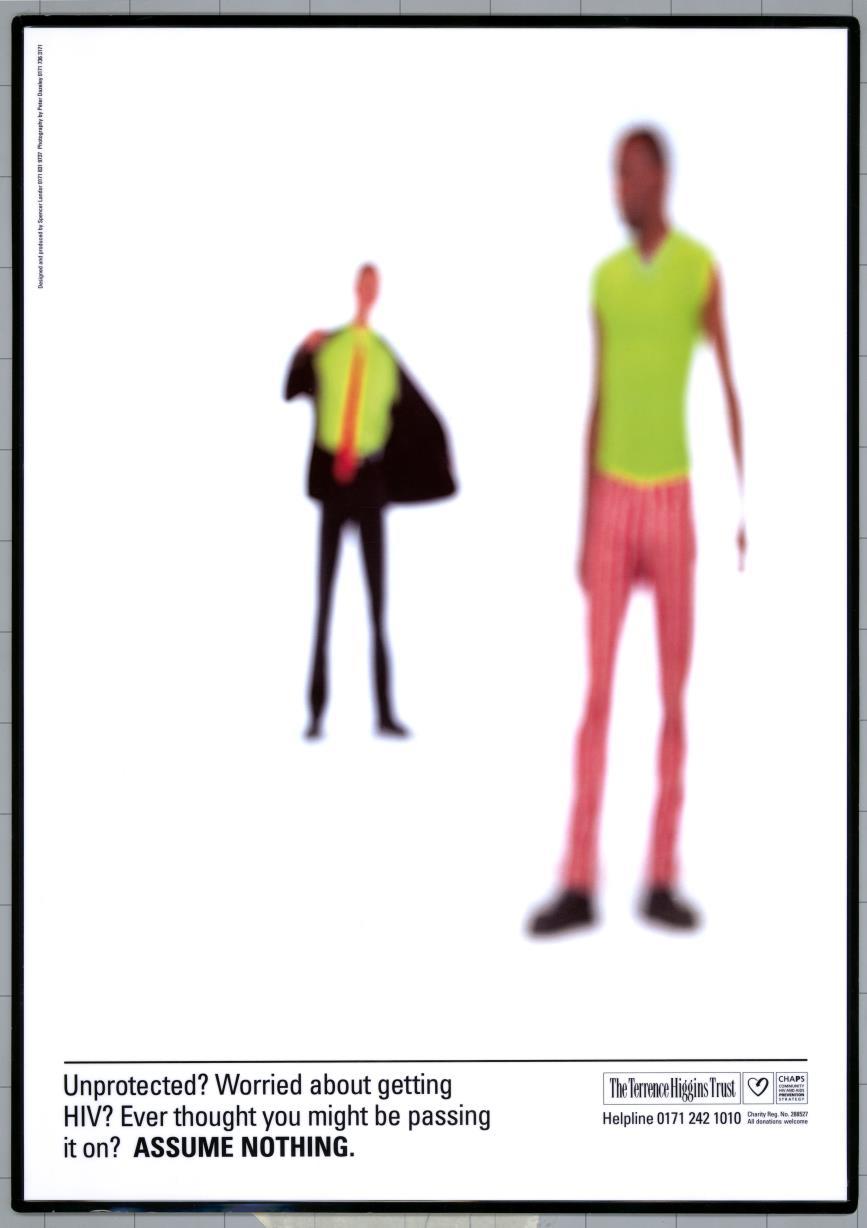

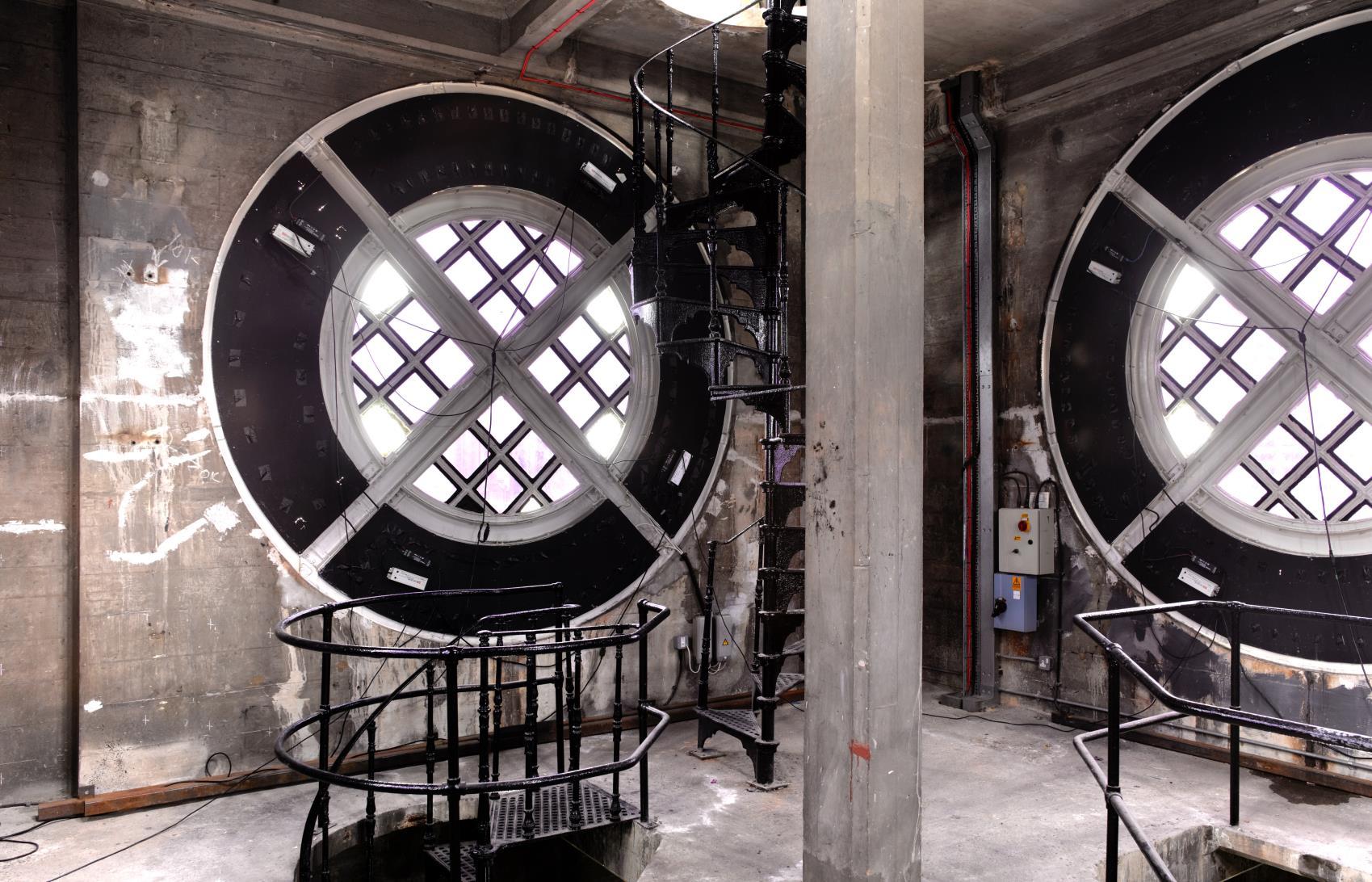

Peter Dazeley and his ‘Unseen London’

CONTRIBUTORS

Editor: Beth Hodges

Photography and Design: Tingshan Liu

With thanks to the following Contributors: Alex O’Connor, for her fascinating interview. To Molly Brennan for sharing her textile delights with us and the team at Wall & Jones, Hackney who provided the beautiful setting of the accompanying photographs. To Andrew Farmer and the team at Watermark Gallery. To Patrick Duffy and Cheska Hill-Wood of Messum’s gallery for giving us a sneak peak into the day to day lives of art dealers. To Peter Dazeley for his insightful interview and allowing us to feature the gorgeous images from his books. To Martin Weller, for his wonderful article on snuff boxes! To the BADA members whose images are featured within this issue.

For Media and Press enquiries, please email: media@bada.org

For further information about joining BADA Young Friends, please email: bethany@bada.org, or call 020 3876 0147

For further information about contributing to Inherited., please email: bethany@bada.org

Follow us on Social Media: @bada1918, @badafriends

Please note, the opinions shared in Inherited., are not held by the British Antique Dealers' Association and those expressed are those of the contributing individuals.

Inherited . All Rights Reserved

Letter from the Editor: Beth Hodges

Dear Reader,

Welcome back to Inherited. for the Summer of Craft issue. We hope you are enjoying the summer months so far! This month, we have quite the variety of trade professionals and crafts people sharing their skills and insights with readers of Inherited.

We hear from silversmith, Alex O’Connor who gives a fascinating insight into the techniques she applies in her work, as well as a wider perspective on the trials and tribulations of the trade and the joy of the community it has to offer- a must read for those considering a career in silversmithing or metal work. We have a delightful time with Molly Brennan of ‘Rug is the Drug’, frolicking in the kooky setting of Wall & Jones Boutique. She speaks to us about her trend-setting creations and her journey to becoming a designer and owner of an independent business. We make a trip to St James’s, London, to speak to the team at David Messum Fine Art about the day-to-day life of a dealer.

Lastly, we are privileged to have interviewed photographer, Peter Dazeley about his series of books exploring the unseen locations and spectacles of London, as well as hearing about his long-standing career in the industry. With all this and more within the issue, we hope as always that you enjoy reading.

For more information on membership to BADA Young Friends, email Co-Ordinator, Beth Hodges at bethany@bada.org or call 020 3876 0147.

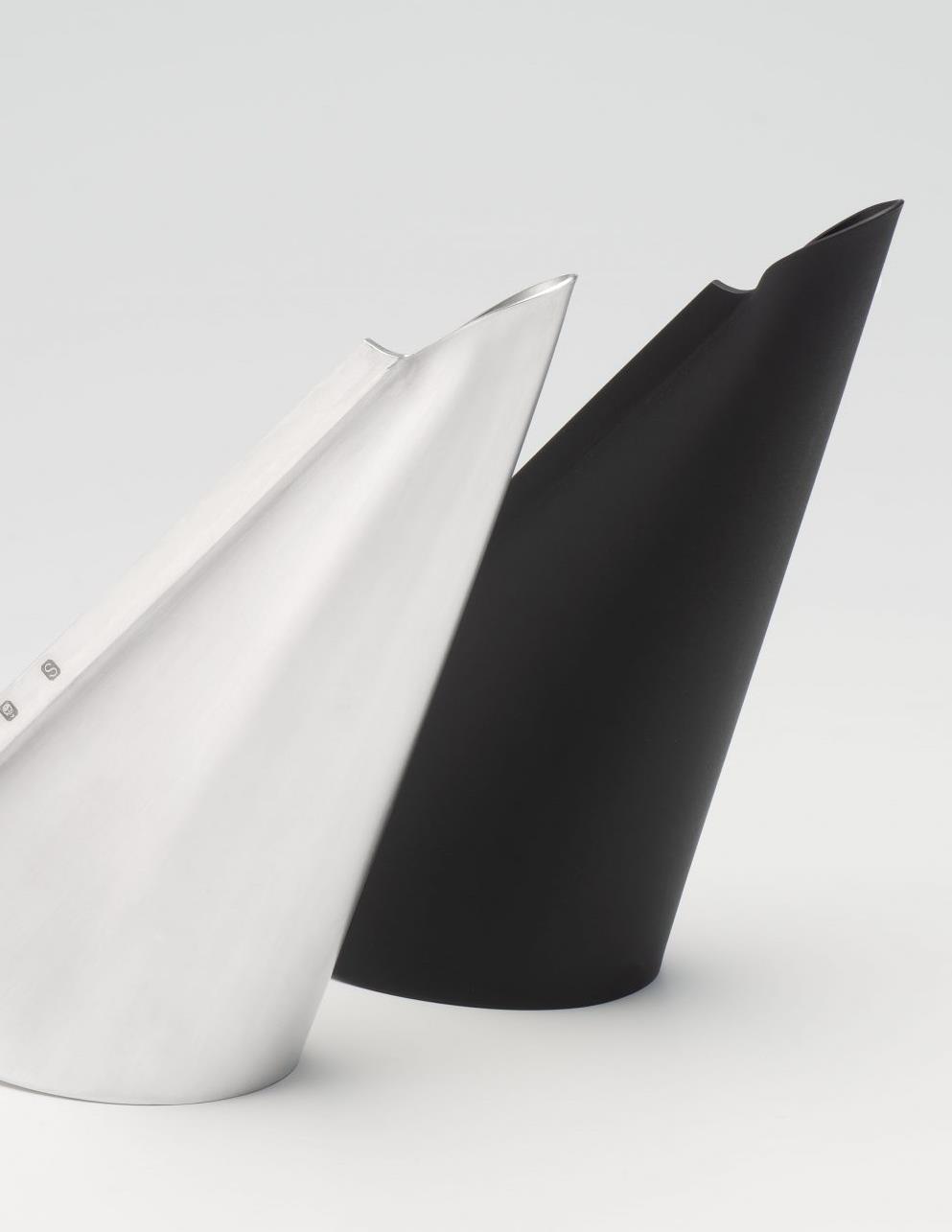

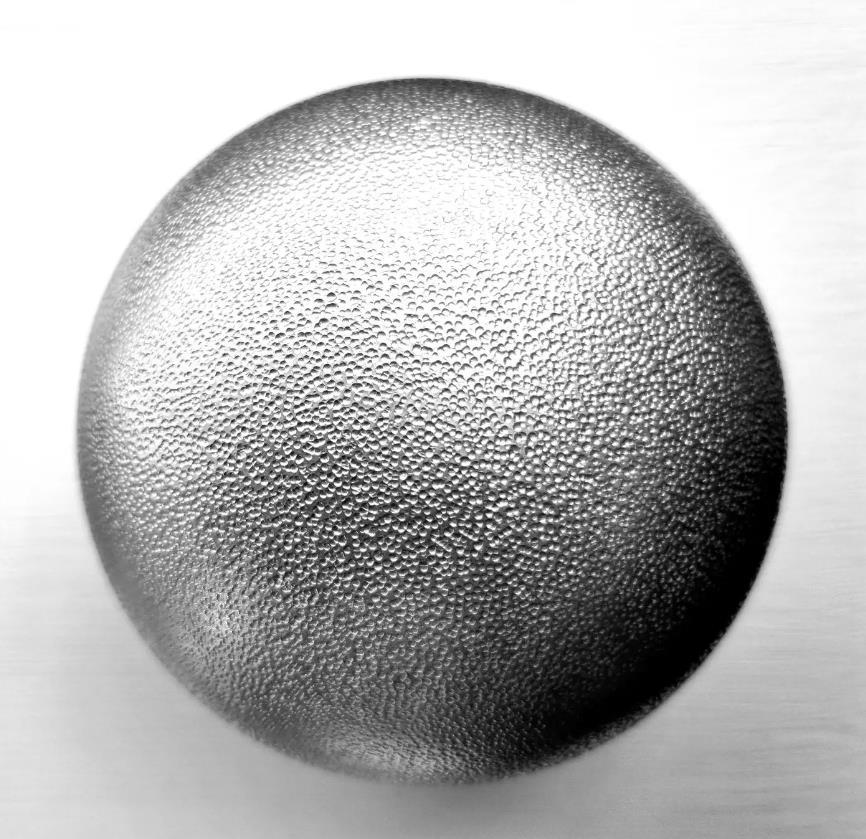

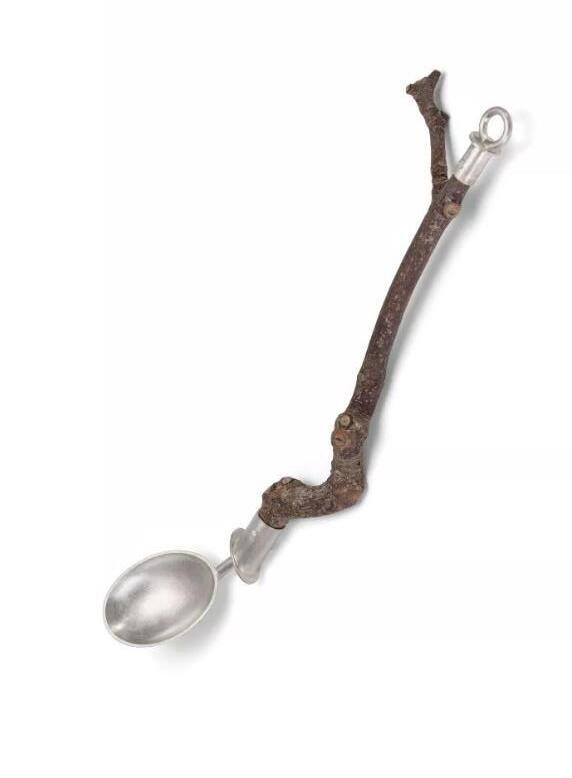

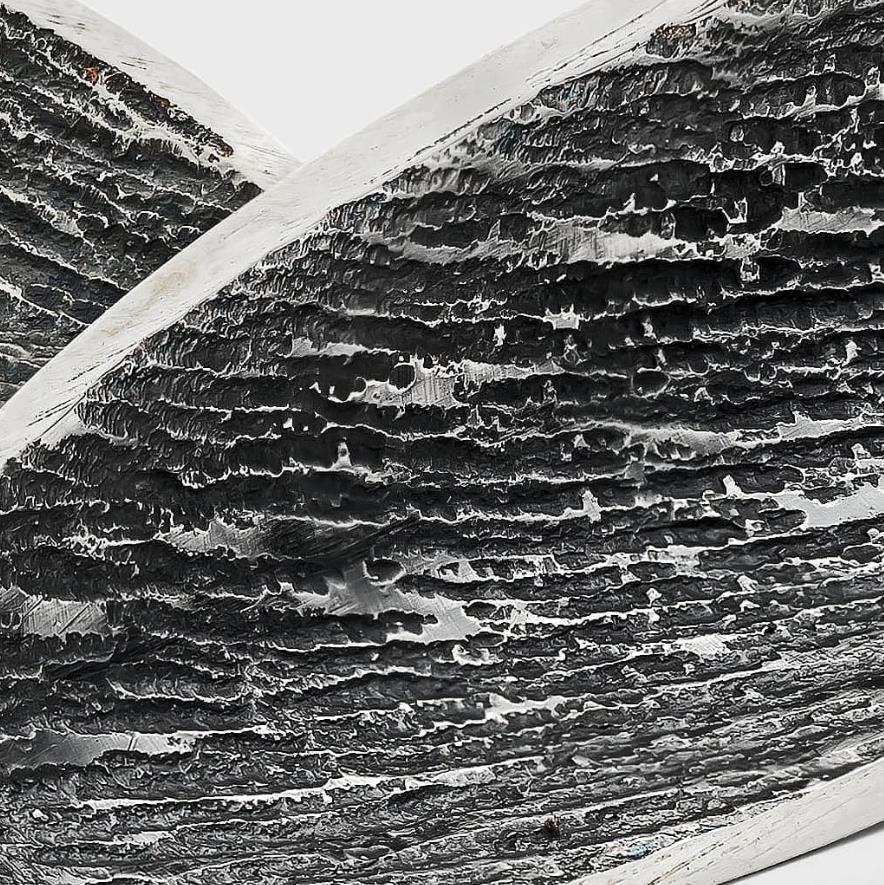

Contemporary Silversmith

A: My name is Alex O’Connor and I am primarily a silversmith, as well as a jeweller. I have been doing this since 2017

B: Could you talk me through a few of the techniques applied in your work?

A: I start with basic techniques, such as sawing. I often use a fine bladed jewelers saw and for bigger pieces, I use a bandsaw. Another tool I commonly use is a scoring tool, which can be made from an old file. The purpose of this is to score a groove in the silver, so that it can then be folded along the score This is a very traditional method, historically used for making crisp, fine objects, such as metal boxes. I use them to shape metal and create forms, like my vessels. I do some hammering in my work, often in the form of ‘raising’, where I hammer a disk of silver over a steel stake. I use different tools for creating the finishes of my pieces, such as polishing or texturing. Sometimes I scour the surface of a piece with abrasives. In general, I use traditional tools that have been brought up to date with modern technology.

Spinning is a technique, alongside polishing, which I outsource to specialists in that particular area. Spinning involves a spinning lathe with a chuck. It’s a highly specialised technique and there are only a handful of good spinners left in the industry.

B: What draws you to silver as a material to work with?

A: Although the price for silver is high and this can sometimes dictate designs, silver is a wonderful material to work with. I often work with sterling silver, which is alloyed with copper, to make it stronger. Fine silver is much softer and requires folding or chasing to give it strength.

With sterling silver, you can anneal it (apply heat and relax it). This allows you to bend, twist and hammer the silver Press forming (I use a hydraulic press) allows me to create beautiful, smooth and seductive shapes This can be done with hammering too.

Silver can also be finished in different ways, changing its surface It can be highly polished to give a chrome appearance. Through using abrasives or a pumice, it can be given a soft, milky finish. To texture pieces, I sometimes put them in a warm pitch and then use a hammer and steel punch

Silver is beautiful but challenging, both technically and in terms of its cost. It can be a rather harsh mistress, but also very magical and I think most silversmiths would say the same thing. Previously, sterling silver was a popular material due to its practicality and strength. Silver has oligodynamic properties- which makes it anti bacterial. This is probably where colloidal silver came from. Silver was superseded by steel and stainless steel, due to industrial processing and cost.

B: Could you tell me how you both maintain the traditional aspects of silversmithing in your work, whilst creating innovative and experimental pieces for your collections?

A: Anyone who works with silver, beyond the scale of jewellery is maintaining tradition Through whatever iteration a silversmith chooses, they are tapping into a long tradition. Many aspects of basic tooling would be familiar to silversmiths from 100s of years ago. We still use heat, but instead of an open fire with bellows, we now use propane and air. We use acid to pickle the oxides off silver and we still use hammers and stakes The techniques of scoring and folding are age old, as well as soldering. Metal spinning is also traditional, in the context of the industrial revolution.

Core skills are very important. Tradition is vital and becoming familiar with techniques and tools is the foundation from which silversmithing grows but it can be augmented, through digital techniques, for example.

It’s a tricky and interesting question. My work is pretty much hands-on, it’s just tools and my hands, which is how studio and artisan silversmithing has always been.

B: Do you think it is considered to be controversial when silversmiths move away from traditional techniques?

A: The advent of studio silver, with silversmiths such as Gerald Benney (who was also an enameller) opened the door to different approaches to silver. Michael Rowe, who was a tutor at the Royal College of Art, also embraced and advocated a different philosophy. There was less demand for functional silver objects and this necessitated working with new forms and concepts.

David Clarke is a highly skilled silversmith whose practice has become increasingly experimental. He is a fascinating and restless silversmith. He carried out experiments, such as putting salt into silver to see what happened (it etches and burns the silver). He has actually just become a freeman of the Goldsmiths company. Sculptural silver objects and art objects were key in the development of silversmithing over the last 40 to 50 years. Contemporary craft in general is often a cross over of design, function, art and concepts which I think is quite healthy.

B: Your pieces are wonderfully balanced between fulfilling both a decorative and utilitarian function for your collectors. Could you speak about how you have achieved this and perhaps touch upon the common belief that collectable and precious pieces should be admired, but not used?

A: I really think it’s about the attitude of the collector and this isn’t a cop out!

My hope for the pieces I create is that they find a space in a home and a life One of my vessels, for example could hold roses, or freesias or an orchid and this would fulfill its purpose. I hope that my pieces feel beautiful in the hands of its owner. I also aim for my pieces to work in a space or on a surface They can be enjoyed and added to or used as art objects in a static state. They can be put in different configurations, as I often make the pieces in groups. If the collectors of my items decide to use them, they need to accept them being marked, tarnished and getting dusty. When I make and sell something, it takes on another life. A craftsman I recently visited makes pewter bowls, which are initially crisp, clean and precise, but over time, they are used by families and become dented with a lovely patina.

With my tumblers, they can be kept and cherished behind glass, but I have made them with being held in a hand in mind. In fact, I have witnessed many men and women hold the tumblers and men almost always hold them with one hand, whereas women always use both. It’s things like this that fascinate me- that it is completely split.

B: Do you feel a sense of disappointment when an object is used in a way that you did not intend it to?

A: No, because a huge part of my practice is considering the sculptural aspect of the pieces It’s about their composition, balance, visual weight and their insides and outsideswhich are slightly more abstract ideas and allows for them to be engaged with in a more abstract way.

There are pieces I make that rock- they have rocking bases. I made one of these pieces for a gentleman and his intention was to put pens in it, on his desk Lots of people said, ‘No! How could you do that’ and I said, well that’s how he saw my piece, on his desk, rocking with pens in it. Every time he takes a pen out and puts it in, it rocks and it’s engaging People bring their own ideas and their own responses to my work.

B: Following on from this, what sparked your desire to create vessels as part of your practice?

A: I wrote a dissertation on this and I still haven’t quite got to the bottom of it. I like them, I love them, they intrigue me. I don’t knowthere is probably something a bit Freudian about it. The interior/ exterior really resonates with me. I wish I could say “It’s because X, or Y”, but I can’t- it’s something I just gravitate to every time, even in little forms, like the jewellery pieces. They always have vessel forms. One day I’ll do something completely flat- but to be honest, it will still probably end up like a dome shape.

I suppose vessels are the most ancient, universal of objects, we encounter them every day in mundane tasks, yet they are realistic too.

B: What would you say is the most important aspect of quality craftsmanship?

A: I think skill is really important, no matter what medium you work in. I suppose an openness to keep learning is also important. Unless you are a virtuoso silversmith, like Clive Burr, who is amazing- although even he says he is always learning. Wayne Meeten or Ray Walton are both superb and would say the same. Imposter syndrome is big for me, because I haven’t been doing it for very long. It’s all about having the humility to learn and keep learning and to keep challenging what you do. That’s how you learn- by challenging your work, instead of coasting. It takes work and time. I don’t know about the 10,000 hours thing- it’s a bit off putting But it does take time to learn. There are plenty of makers who have a formula to how they work, but there are no shortcuts. There is no thoughtlessness- it’s precise, it flows. Work like that often comes from years of gaining fluency with tools, materials and processes. In the words of Browning, ‘A man’s reach should exceed his grasp- or what’s a heaven for?’ You always should be reaching in your work

There is often a sense of ‘oh is that it then’, when you complete a piece of work. You have to make friends with your work- a lot of us have a very loud inner critic.

B: Unfortunately, as with many other creative professions, silversmithing continues to be subject to misconceptions by those outside (and within!) the community. Most commonly, the profession of silversmithing can be perceived as a ‘closed’ community and very traditionalist. Could you speak to why this is certainly not the case?

A: I finished my degree in 2017 and prior to that, whilst I was a student, I found it to be very open as an industry. I could always ask for help and ask questions. People were very generous and still are. It’s a very small community, so everyone knows each other, either through their work or their reputation. It’s certainly not closed in my experience. There are a lot of new makers coming into the industry, which really helps. There are also lots of women in the industry. If people from outside the industry, ask what I dothey might say ‘what’s the point in that’- but there is a market for it. There are lots of different silversmithing communities, outside the UK- in Europe, the Netherlands, Scandinavian countries- they all have their traditions of silverware and craftsmanship. The tradition in this country is so old, it can be perceived as witheringly conservative but generally there is an acceptance that you can be as ‘out-there’ as you like, as long as your craftsmanship comes from a place of trying to gain skill. I love it- I think it’s very flexible- it flexes and moves with the times.

B: Your pieces could be considered as the antiques of the future. What do you think about this and how do you think people will interpret your creations?

A: I think that’s such an incredible idea, I almost can’t wrap my head around it. It’s a very humbling idea- to think that these pieces would endure- it’s phenomenal- I hope they do and live as antiques of the future. And that’s why I make them as well as I can, I get them hallmarked. I hope that, aesthetically, they have something about them- I think the cleanness of the design will age well- you never know if something would date. I don’t think they will in the near future, because of their simplicity and they have a certain classicism. They aren’t laden with frills and they aren’t so contemporary that it would date them I think they have a long life, hopefully And of course, silver has inherent value I would hope the pieces wouldn’t just be melted down to get the bullion value- but who knows, with the value of silver! I think they will endure. People collect things- and sometimes, people build an entire collection, they complete it and they sell it. It’s back to the autonomy of ownership. People collect for all sorts of reasons- there’s a psychology to collecting and owning antiques. It blows me away that you use the word ‘transcendent’ when describing my work because that’s what I aim for- so thank you. Some people find it cold, but that’s ok.

B: What defines you as a creator in your field?

A: I feel like I’m the wrong person to ask. It’s like that great question of ‘What’s your brand’- what do people say about you when you’re not in the room. It’s so difficult. Minimal isn’t the right word I’m very exacting, in terms of what remains when I make a piece. There will be lots of models and drawings, and then I strip things away, so that what remains is essential. There’s no fat on them and no bits that shouldn’t be there. I have a real vision for what I do- I don’t always know what it is until it arrives there. It’s very hard to put into words- but I’m trying to do something very specific. I try to use a crossbow and not a shotgun.

B: Do you have any predictions for how silversmithing will develop or change in the future?

A: It’s a very interesting question- if we can hold onto some of the really good courses out there, we stand a chance of surviving. The price of silver is very high at the moment- so giving students the chance to work with it is hard You can play around with other metals, like bronze, copper etc, but nothing responds in the same way as silver. It behaves like nothing else and there is no substitute. Organisations like Contemprary British Silvershmiths provide training and they work with a company that loans silver, so you can practice and keep the silver or send it back. In many ways, the future seems quite rosy. There’s been a resurgence in interest in contemporary silversmithing- with Adi Toch for example. Her work traverses traditional silversmithing and art objects- its amazing. Once people get the bug, they’re hooked- it’s what they do. It’s an obsessive environment, you want more tools, more projects- there’s a nerd-core element, so I think that bodes well.

B: Could you recommend to our readers some organisations, courses, or communities you think they should engage with, should they wish to pursue a career or interest in silversmithing?

A: Contemporary British Silver smiths are really good- they work with students, interested people, graduates, full members. The Goldsmiths centre in Clerkenwell is great, they are the educational arm of the Goldsmiths Company. The Goldsmiths Company contain the London Assay Office and host the Goldsmiths Fair, which is a great event to visit, get insights and ask people how they started. There are some very good short and taster courses available as well as degree programmes. I love a bit of social media- it’s a great way to see what’s out there- it makes the community smaller.

B: What advice would you give to budding silversmiths on how to develop confidence in their own practice?

A: Be open to guidance, be resilient- that’s important. It’s a tough gig, silversmithing. It’s great fun and a lovely community to be in- ask for help. Reach out and ask and people can help you. If you have 50 silversmiths, they will do things in 50 different ways- but one way will work for you! Cara Murphy at CBS is great-she has run technical and educational Zooms since 2020 where all questions are welcome

B: Within Inherited, we like to give the space for creators to speak about their peers and other work they admire. Could you name a couple of silversmiths you think our readers should take a look at?

A: I think in terms of peers, or someone who knocks the spots off everyone- I would say Jessica Jue. She has a light touch and creates amazing pieces. Anna Rennie is a great silversmith who I admire. She does a lot of hammering and raising pieces- very different to what I do. She has a ballsiness to what she does, which I love. With work I admire and those who influence me- Cara Murphy, Angela Cork, Rauni Higson are just a few. A real spectrum of different makers, different creators and approaches Sometimes it’s the technique that inspires me- Ndidi Ekubia works completely differently to me. Her hammer is almost like a paintbrush- the way she works the metal blows me away. Her boldness and fearlessness is something I really admire.

The BADA is proud to announce that the BADA Art Award is returning for a fourth year, promoting “the antiques of tomorrow” by awarding a £1,000 grant to an emerging contemporary artist whose work exemplifies the enduring ingenuity and quality illustrated by our members’ objects. For more

Rug is the Drug

Firstly, please could you introduce yourself and your practice to our readers who might be unfamiliar with your work?

B: M:

Hello! I am Molly Brennan an artist & designer based in North London. My work focuses on my love of patterns and geometry. Over the past few years this has expanded into tufting and printing on textiles, from which ‘Rug is the Drug’ was born. This is my brand where I make rugs, bonnets, bags, cushions and whatever else I fancy.

Please Could you talk me through a few of the techniques applied in your work? I am particularly interested in the tufting methods used in creating your rugs and bonnets.

There are many stages and variables in the process of tufting. I was drawn towards learning how to tuft initially as a way to develop my paintings into something more tactile, something more physical that makes you want to touch it. For me, all the hands-on aspects of the process are soothing, from the initial drawing of designs, feeding wool into the tufting machine, to sewing the finished piece to a backing.

As with all kinds of different crafts, there is a process and importance in every stage in order to create something one of a kind. I like finding inspiration through experimenting with materials I already have to hand or have sourced second hand. I really enjoy the randomness this adds to the process and the surprise when colours and patterns turn out better than I could have imagined in my head.

How does geometry lend itself to textiles in terms of material, process and colour etc.?

The beauty of geometric designs is endless! Especially when applied to textiles, whether its to wear or not. It provides a framework in which the colours can sing alongside each other and the infinite qualities and variables is what has kept me hooked. I love creating items where no two pieces will quite be alike.

Could you tell us about your initial design process- do you begin with sketches?

I am constantly travelling with my sketchbook in my bag, taking inspiration from patterns in daily life. Some elements of these drawings I think will work amazingly as rugs and some will exist better as paintings. I also carry out a lot of custom work with clients in which there will be a back-and-forth conversation about my designs, alongside ideas they have in terms of colours.

B:

What is your background in the arts and how did your path lead to geometric designs and patterns?

M:

I remember always sketching and daydreaming a lot as a kid, but also going to Catholic Church growing up. This undoubtedly drew me to replicate the beauty within the Church, whether this be from the tiles or the big ceilings, being around geometry just gives me a good feeling. I moved from Ireland to London to study fine art before finding my own style. I felt that university never did much to aid my creativity personally, so once I dropped out after a year and gave myself no pressure and constraints within which to create, this was when I actually began developing in my own way.

Could you tell us about your relationship with Wall & Jones? Your pieces are a perfect fit for the boutique- what is the shop’s ethos?

Wall and Jones is an eccentric dresser’s dream! Filled with unique clothes, jewellery and accessories in every corner, it’s almost impossible not to want everything. People that come in get to support independent designers in exchange for a one-of-a-kind new statement wardrobe piece! I’m so thrilled to have a selection of bonnets, bags and cushions stocked in-store so that customers can come and check out my work in person. It’s really a magical place!

What advice would you give to budding designers on how to develop confidence in their own practice?

Create without pressure. Your confidence in your practice will be born from something only you can do which takes time to nourish. That’s what has helped me the most anyway, putting time into creating without pressuredespite not being sure of the outcome.

Andrew Farmer

The Yorkshire Impressionist

Doncaster may not evoke the same romantic artistic connotations as Paris or Provence but the skills of local artist Andrew Farmer in capturing light and landscape have seen him acclaimed as ‘The Yorkshire Impressionist.’

Andrew, who says the Impressionists such as Monet and Cezanne are his ‘heroes and inspiration,’ was the youngest artist to become a Member of the Royal Institute of Oil Painters (ROI) when he was elected five years ago, aged just 33.

His most recent exhibition, ‘Northern Impressions,’ features images of the Northumberland coast created from numerous visits over the last 18 months, often working ‘Plein Air’ – in the open air – and the more than two dozen works trace his transition from the use of brush to almost exclusively palette knife. It is, he says, a technique that allows greater exploration of light and texture in the finished work.

Andrew, who is married to paediatric nurse Sarah and father to Jacob, aged 10 and Eden, 8, has painted since leaving university but only turned full-time professional 10 years ago and has been garnering a growing national and international reputation ever since. In December last year he was awarded the prestigious ‘Le Clerc Fowle’ medal for an outstanding group of paintings at the ROI’s London exhibition at the Mall Galleries

He says:

“I love painting the ordinary, analysing simple, everyday subjects to encourage the viewer to look more closely at the many wonderful and beautiful things that surround us daily but which aren’t always fully appreciated.

“I regard myself as enormously privileged to do what I do and, in reality, I am just inspired by the infinite fascination of life ”

Andrew’s work tackles a broad range of subjects, including highly personal family scenes, still life, portraiture as well as rural and urban landscapes. His work is held in private collections across the globe and he has won numerous awards.

When painting ‘plein air’ he will spend no more than 60-90 minutes at a time capturing a certain light in the landscape and return to the same spot over several days to complete the scene in the same weather conditions, a technique practiced by Monet.

He says:

“I feel dissatisfied with creating a painting in a single session so multiple visits enable me to really dig deeper into the subject so that I really ‘see’ it and not just ‘look’ at it. I work almost exclusively from life and find that nature offers endless inspiration with the seasons having real impact on my work.”

Of course, modern artists can have the kind of problems that didn’t trouble their predecessors.

On the way home from a painting trip/ family holiday on the Northumberland coast creating works for the exhibition, the car broke down requiring the attention of three breakdown trucks and turning a 2.5-hour journey into an 11-hour marathon.

“I am very flattered at any comparison to the Impressionists, of course, but right at that moment our worlds did seem very far apart,” said Andrew.

Liz Hawkes, owner of Watermark Gallery said in regard to Andrew’s most recent exhibition: “Andrew is one of our most popular artists with a previous show called ‘North Landing’ and based on the Cleveland Way being one of the best-selling exhibitions we have ever had. I have no doubt at all that this one will be every bit as successful.”

You can view Andrew’s work for sale, here.

With thanks to Watermark Gallery You can visit the gallery at 8 Royal Parade, Harrogate, HG1 2SZ.

Meet the Dealers

Patrick & Cheska of David Messum Fine Art

Get to know the people and personalities that make the BADA, as we delve into their businesses, passions, and insights on buying and collecting. Through a series of interviews, we uncover their stories and discover what drives them in the world of art and antiques.

Established in 1963, David Messum Fine Art is a name that has long held a powerful reputation as one of the country’s leading art galleries, not only a pioneer in the field of British Impressionism and the Newlyn and St Ives Schools, but also a specialist in exhibiting contemporary British art and sculpture. The gallery also provides a comprehensive service to collectors and clients supporting and advising on conservation, restoration and framing. Below is an interview with Cheska HillWood, Head of Sales at David Messum Fine Art, and the gallery's Sales and Archivist, Patrick Duffy.

(Interview with Cheska Hill-Wood)

B: Could you tell us about your favourite piece currently in your stock and what makes it special?

C: My star piece at the moment is from our March exhibition of paintings from the estate of Jean-Marie Toulgouat. It is entitled Profusion de Lys which he painted in 1970 He spent most of his career restoring the house and gardens at Giverny and was hugely inspired by the abundance of flowers and planting that surrounded him. It is a large work that would look absolutely stunning above a mantlepiece in an elegant drawing room, I can visualise it perfectly, I just wish I had the space! We change our shows every month so I am extremely lucky to work amongst an ever changing ‘lust list’. Each month I mentally bankrupt myself!

Patrick Duffy (left) & Cheska Hill-Wood (right)

From David Messum Fine Art

B: How did you first discover your love for fine art and antiques? And had you always wanted to work in the industry, or did you have a career change?

C: I grew up surrounded by wonderful works of art: paintings, sculpture, objects, furniture and in a family who were passionate about creativity. I was fascinated by all the objects that were around me. I don’t remember ever being bored as a child. It was inevitable, I suppose, that I would end up in a creative world of some description and I initially went to art school, followed by drama school whereupon I became an actress for many years, but my love of art was always present.

B: Could you tell us your three top tips for buying and collecting antiques?

C: Only ever acquire works that you love –it’s a cliché perhaps, but so true. There needs to be a visceral connection. It’s difficult to explain why you love something, but the ‘why’ doesn’t matter.

What is important is that you can’t live without it. If, when you leave a gallery, the picture doesn’t leave you then you know you should buy.

B: Could you tell us about a recent visit to a gallery, exhibition or fair you have visited and enjoyed?

C: I went to Tate Britain to see "Sargent and Fashion" and was totally blown away by the scale of it – the number of paintings in the show as well as the size of some of the pictures. It’s breathtaking. His skill at capturing the richness of the fabrics worn by his sitters is unsurpassed. It was particularly interesting for me as we represent the Estate of Wilfrid de Glehn who was Sargent’s painting companion, so to see the similarities in some of the portraits was inspirational. I am obsessed with Tate Britain – the building and the exhibitions. Even during the lockdowns, I had to cycle passed it to ‘get my fix’ in lieu of being able to visit.

B: What is a common misconception about the world of art and antiques?

C: That we are elitist or that you shouldn’t come in to a commercial gallery unless you are planning to buy something. We are delighted to welcome visitors to our St James’s gallery. It’s wonderful to be able to discuss an exhibition or artist with people. We don’t want to be on our own all day! There is such an incredible wealth of dealers in this area that you can spend all day seeing the most varied works and learning so much I think I speak for everyone in the area, when I say the doors are always open (even if you do have to ring a bell!)

(Interview with Patrick Duffy)

B: Could you tell us about your favourite piece currently in your stock and what makes it special?

P: My favourite piece we will be exhibiting in the summer exhibition, ‘British Impressions’, by Newlyn painter, Harold Harvey. Called ‘The Fishing Wharf, Newlyn’, it has been in private hands for decades and was previously unrecorded. Being able to bring unseen works to the market is always exciting as it gives you the opportunity to be the first to research the work and to add to the artist’s history.

B: What would you say has been your biggest personal achievement in your career in fine art & antiques so far?

P: My biggest achievement personally has been being able to work closely with the paintings by the artist, Gluck.

Mercurial and incredibly talented, Gluck’s paintings are highly desirable, not simply because of their stunning graphic realism, but for their quality, and for the personal and historical context in which they were produced

B: How did you first discover your love for fine art and antiques?

P: Art, for me, is all about telling stories. Every object tells a story and if it doesn’t, then something has gone terribly wrong for the artist.

B: How did you first get involved in the industry?

P: Serendipity I left university with a view to work in a gallery, started interning at The Fine Art Society and that was it.

B: If you weren’t a dealer, what would you be?

P: I’d probably own a pub.

B: Could you tell us your three top tips for buying and collecting antiques?

P: Buy what you love. Shop around, and do your homework but don’t trust everything you see on Artnet.

B: Could you tell us about a recent visit to a gallery, exhibition or fair you have visited and enjoyed?

P: The last exhibition I was truly effected by was ‘Invisible: Art about the Unseen 1957-2012’ at the Hayward Gallery in 2012. I’ve never been more disturbed.

B: What would you say is needed to be a successful dealer?

P: Common sense goes a hell of a long way in this industry.

B: What is a common misconception about the world of art and antiques?

P: I think it is sad that people still perceive west London galleries to be a closed world. We like to remind people that everyone is welcome at the gallery in St. James’s and we try to offer a variety of art works for all to enjoy seeing and not just to buy. The trade have an amazing opportunity to create new research and build upon art history from first hand contact with artworks and that is what we are seeing more of.

B: Who do you admire in the world of art and antiques and why?

P: Sadly they are no longer with us, but Charles and Lavinia Handley-Read were an inspirational, and highly influential collecting duo who fused their passion for art and research together in a way very few people are able to claim to do, even today.

B: What is your favourite appearance of an antique in a film, play or book?

P: The Dale Chihuly vase in the American sitcom, Fraser. It was the most expensive item on set and needed to be locked in a vault after shooting each scene in Fraser’s flat. I like random pieces of trivia like that.

B: What events have you got coming up and where can we next view your stock?

P: Currently we are working hard on our Summer exhibition of British Impressionist and Newlyn School pictures, however, before that, we have a new show of work by Matthew Alexander. His views of the Southeast coast will fill the gallery with a sense of light and wanderlust just in time.

B: Who would be your dream dinner party guests, dead or alive?

P: There are too many to think about, but if you sat me down in the dining room of the Chelsea Arts Club in the 1890s, I’d be pretty happy.

Shop at David Messum Fine Art, Here.

Interview: Peter Dazeley, Photographer

B: Firstly, please could you introduce yourself and your practice to our readers? Could you tell us about your first camera and how you started shooting?

P: I’m a born and bred Londoner and in the 1950s/60s was educated at Holland Park School, now known as the Socialists’ Eton I struggled wildly with dyslexia But neither I nor the teachers knew anything about dyslexia in those days. The school had amazing facilities including photographic studios and darkrooms. I think photography discovered me. I was taught on plate cameras with glass plate negatives. I left school aged 15 and got a job as an assistant in an advertising studio, where I was paid £4.50 per week. Not even in a lifetime, we have gone from glass plates, through film, to digital photography. I now also sometimes shoot just on an iPhone camera.

B: Do you have a favourite image within your wider portfolio? What’s the story behind it?

P: I love blagging. My favourite picture is of my 13-year-old son, Indigo, being born by caesarean section. I asked the surgeon if I could take a picture. He said ‘I’ll let the screen down’. I managed two frames of my son’s first breath, an amazingly emotional moment I put the image up on social media and it was greeted with loads of ‘likes’, and also shocked abuse. I love to create images that provoke a reaction.

B: Do you prefer photographing interiors or people and why?

P: As an advertising photographer, I’ve been so lucky to work across so many different subjects. Whether its portrait, lifestyle, architecture, in fact there is very little I haven’t shot in my career. At the height of my career now, it is lovely to take on personal projects which I can work on in my own time and at my own speed, without the pressure of clients and deadlines.

B: In 2013, you were awarded a fellowship by the Royal Photographic Society. Could you tell us about the criteria for receiving the fellowship and how it felt to receive such a prestigious award?

P: It was a great honour to receive the Fellowship from the Royal Photographic Society, as it represents the highest distinction of the RPS for original work and outstanding ability.

B: Could you speak about your experience in the world of photography for advertising? How has this leant itself to your work today?

P: I’ve had a wonderful career working for advertising agencies. For accounts like: Dove, Adidas, Waitrose, Sky, Tower of London, Aviva, Labour Party, Gordons Gin and many, many more. You get to collaborate with a lot of great creatives, stretching you in a direction that you wouldn’t necessarily have gone. It’s all about answering the brief and working with a team. My agent, who represents me in the UK, says: “making the ordinary look extraordinary is Dazeley’s gift”. After such a wonderful career I have also done a lot of pro bono work for charities such as the Terence Higgins Trust, Prostate Cancer and Shelter, which is a lovely way of giving back. I was lucky enough to be recognised for this work and awarded the British Empire Medal for services to charity and photography

B: How do you approach capturing locations that are prolifically photographed and what enables you to make your images so unique?

P: I always research locations before I visit, to see what has been done in the past and how I can make my pictures different. I arrive with an open mind and look for the unexpected things that really interest or surprise me, such as the detail and behind the scenes A great example is the Royal Naval College at Greenwich After arriving I asked what interesting places there were that I hadn’t seen and was taken underground to find the undercroft- the only remaining part of Greenwich Palace, also known as the Palace of Placentia where Henry VIII was born and lived. It was the principal Royal Palace for two centuries.

B: Over what time scale did you photograph the collection of images for your books?

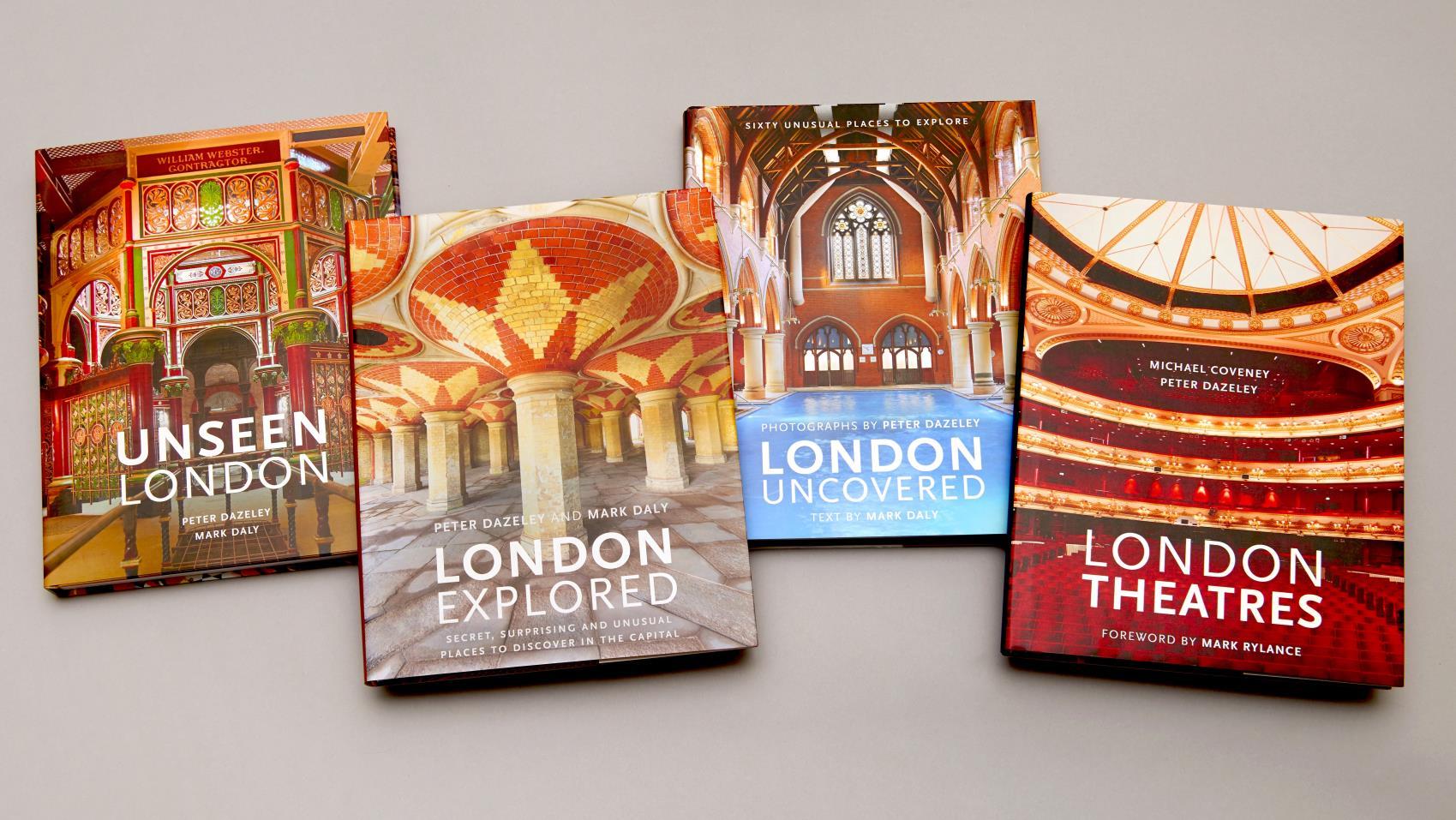

P: My first book, Unseen London took me about 4 years. After I had a book to show people it made gaining access to locations so much easier. My other three books took about 12 months each.

B: There is a lovely synergy between old and new within your books- was this intentional or were you simply capturing what London has to offer?

P: Being a born and bred Londoner, I thought I knew London incredibly well. But once I started researching for the book, I continued to find and photograph amazing old and new locations, a lot of which I was unaware of. In fact, I recently discovered a working Windmill in Brixton.

B: What is the location in London that you feel most privileged to have been granted access to for a shoot and why?

P:This is a difficult question as I have felt privileged to be in an awful lot of these locations, it’s a bit like asking which is your favourite child. But at the time I did know the chairman of the Conservative party who was very helpful and got me into Downing Street, for which I was eternally grateful. The building is like a Tardis, so much bigger than it looks from the outside; it’s absolutely enormous.

B: What was the biggest surprise you encountered when photographing London?

P: My London Theatres book was a big surprise My publishers approached me out of the blue, as it was a project that they felt readers would love and it matched with the work I had already done with my other London books. Working with writer and theatre critic Michael Coveney and the actor Sir Mark Rylance, who wrote a fabulous foreword, was so much fun I was going behind the scenes, above the stage, below the stage, the grids, the fly floor, the royal boxes and dressing rooms etc. I met lots of great people.

B: What is the location that was most challenging to photograph and why?

P: The Crystal Palace subway, the cover photograph for my book London Explored. It took about a year to agree access, due to safety concerns etc It is run by a ‘friends’ group and the local council. But it was well worth it in the end. Such beautiful architecture for first class train customers arriving at the Great Exhibition of 1851.

B: What would be the dream location for you to photograph in London or beyond?

P: The two locations that got away from me. The Public Gallery in the House of Lords and House of Commons. I was keen to illustrate and encourage people to go and see democracy in action But the speaker and civil servants ignored my requests

B: My favourite image is the interior of the OXO tower. Could you share the story behind the image?

P: The Oxo Tower picture is an example of the fun I have with the creation of my London books and blagging my way into gaining access behind the scenes. I had eaten many times at the restaurant and was intrigued to find out exactly what was inside the famous Oxo Tower

B: I am very much intrigued by your decision to photograph the toilets at Lords Cricket ground- there is something quite aesthetically appealing about the image- could you speak to this?

P: I love the picture at Lords. Especially as only 50% of the population can see it. It shows wonderful Victorian architecture at use, for urinals.

B: How do you think/hope your photographs will be received in the future?

P: As London is constantly changing and being rebuilt, I love the fact that I have tried to record London as it stands today in the 21st Century I plan to offer the images to my favourite museum, the London Museum for Posterity.

B: What advice would you give to budding photographers on how to develop confidence in their own practice?

P: Always have a camera with you – there have been several times when I have seen things and I really wish I had had a camera to record it. Experiment like mad. For my work, featured in my new Monochrome book, I have used all sorts of techniques such as anamorphic lenses, mammograms, x-rays, limited focus. Don’t wait for the phone to ring, go out and make it happen. Get your work seen. Be prepared for knock backs, have thick skin and feel good about yourself Sign and date your pictures and put them on the wall, be proud of your work.

I have also mentored many young aspiring photographers, with work experience and advice. Helping them navigate a career as a photographer. I also love giving talks, doing podcasts and radio & TV about my work. To share my world, my experiences and the joy of being a photographer. No two days are the same. I feel I have been very lucky.

B: Within Inherited, we like to give the space for creators to speak about their peers and other work they admire. Could you name a couple of photographers our readers should take a look at?

P: One of my favourite photographs and biggest influence, is Irving Penn. I love his portraits, fashion and still life images from the 1930s and 40s. His images still look modern today. I also love Scottish Photographer Albert Watson His fashion photos and portraits are amazingly diverse. Like me, he is blind in one eye, and has produced a wonderful book called Cyclops, which is well worth having a look at. See Peter’s work: www.peterdazeley.com

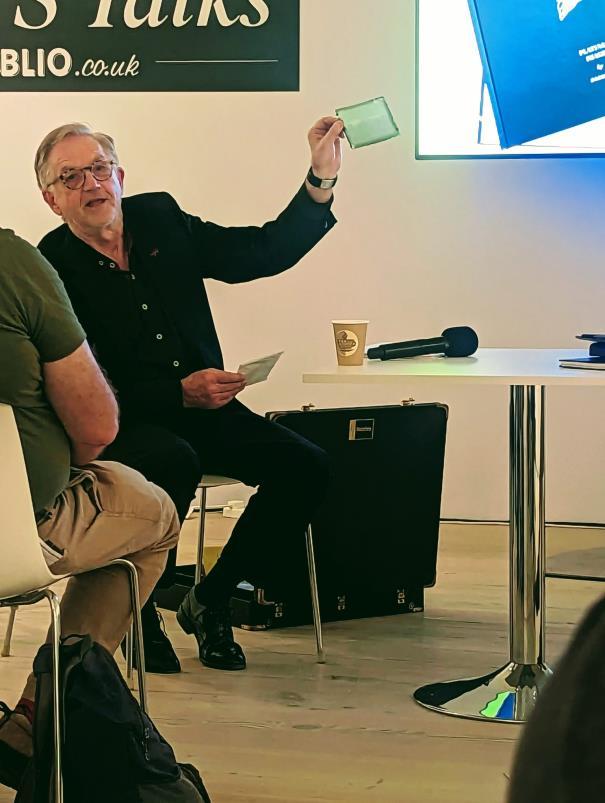

Peter Giving a talk for the BADA Friends at Firsts Fair, London

The Maker’s Series: Snuffy Charlotte

One of the most frequently searched items on the BADA website, the humble snuff box has been a mainstay of English society since the mid-17th century.

Manufactured from ground tobacco leaves, snuff is a fine powder that is inhaled into the nasal cavity and was first imported to Europe by Spanish traders in South America and quickly became a luxury commodity.

Often flavoured with scents and essences, snuff became fashionable in England in the 1650s with many people believing the new craze had medicinal powers. Not surprisingly, consumption of snuff rose sharply in London which was gripped by an outbreak of bubonic plague in 1665-66.

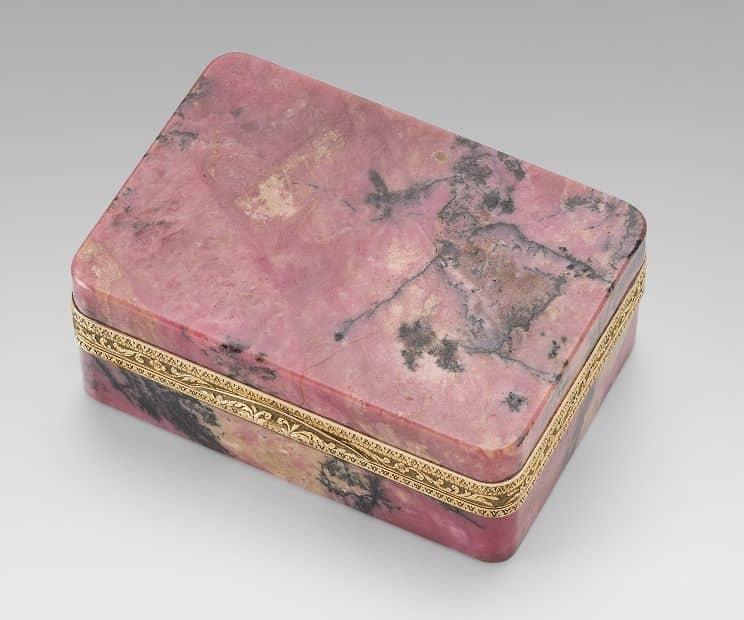

The quality of snuff is compromised by prolonged exposure to air so enterprising entrepreneurs created the snuff box as a solution for safely storing your supply. These were offered in two variations, small sized options that fit conveniently into a pocket, containing around a days’ worth of snuff, and more substantial boxes for practical domestic storage, known as mulls.

Golda Rosheuvel as Queen Charlotte in season one episode two of Bridgerton:https://www.yahoo.com/lifestyle/que en-charlotte-sniffing-bridgerton-204429150.html

The handy containers were manufactured in a wide variety of mediums to suit every budget, from everyday affordable materials like wood, metal, and horn, to more luxury alternatives made from gold, ivory and silver. The more expensive designs were often finished with exotic decorative materials and motifs such as mother-of-pearl, tortoiseshell, fine enamels, precious gemstones and even portrait miniatures

Snuff taking was seen as a pastime of the more elite members of society, setting them apart from the common pipe-smoking man. Celebrated snuff enthusiasts include Queen Anne, Lord Nelson, the Duke of Wellington, Napoleon, and Marie Antoinette.

While Queen Charlotte, wife of George III, was such a prolific consumer of snuff that she requestioned an entire room at Windsor Castle for storing her personal reserve. In fact, her usage was so prolific that it earned the Queen the extremely unflattering nickname, “Snuffy Charlotte”.

One of the most famous English snuff boxes was the Parliamentary snuff box, first installed at the House of Commons in 1694 after smoking in the chamber was prohibited Designed for use by Members of Parliament, the box was destroyed during the Blitz when a German bomb struck the Palace of Westminster in 1941. A replacement box was fashioned from timber salvaged from the chamber’s door and remains in use to this day.

View a selection of BADA members’ Snuff Boxes for sale, here.