CONTENTS

I. EXPLOITATION p.6 Definition

Modern History

Protagonists: Trafficker, Officials, Criminal Networks, Society

2. VICTIMS p.23 A Day in the Life

The Numbers

Vulnerabilities

3. IMPACTS p.36 Emotional Physical Psychosocial

A Survivor’s Voice

An Activist’s Voice

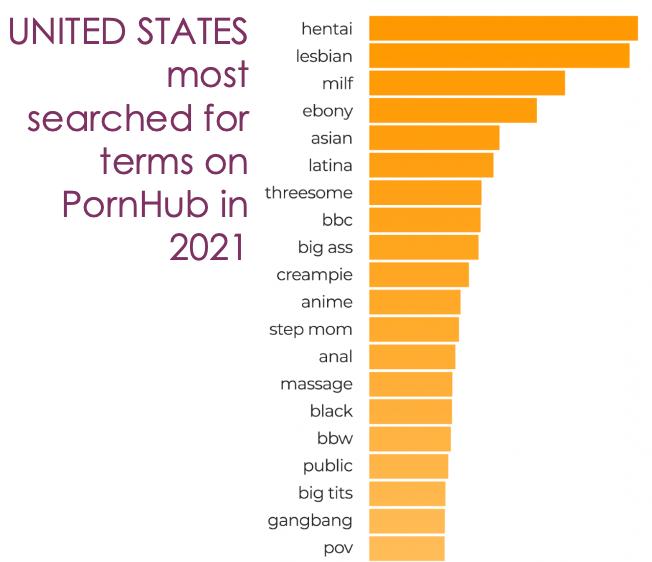

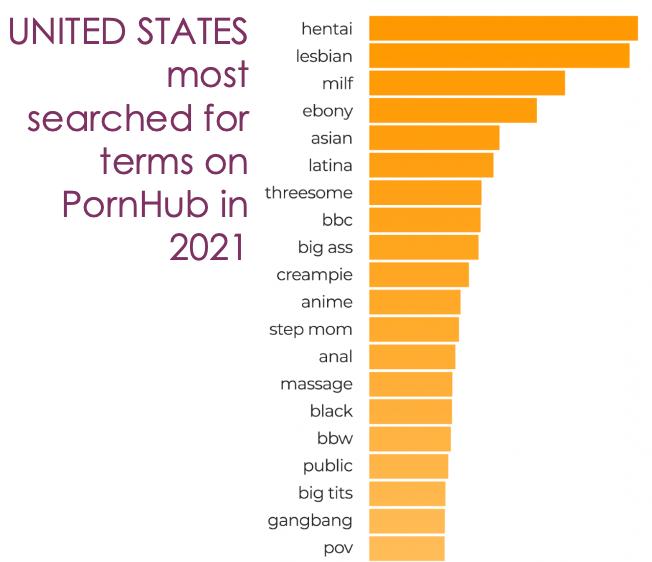

4. DEMAND p.44 Pornography

Sexual Violence and Purchase of Sex Acts Addressing Demand

5. PROTECTION p.52 Home Online Community Positive Attitudes, Traditions and Practices Monitoring and Reporting

6. PREVENTION p.63 A Complex Issue

A Pathway to Prevention Capacity Building Mobilization Resources Zero Tolerance Zones

7. SELFCARE p.70 Compassion Fatigue: Causes, Symptoms and Resiliency

Tips for Managing Compassion Fatigue Core Values of Protect Me Project

END NOTES p.79 | RECOMMENDED READING LIST p.93

3

4

Venezuela: Protect Me Project volunteers working in public schools to empower elementary school children.

ONE: EXPLOITATION

Human trafficking – documented in 175 nations – reveals the normalization of human cruelty and the cultural processes that have empowered it. [People] are bought, sold and resold as raw material of an industry, as social waste, as trophies and offerings.1

DEFINITION

According to the Palermo Protocol, part of the United Nations Convention Against Transnational Organized Crime (2000), human trafficking is:

The recruitment, transportation, transfer, harboring or receipt of persons, resorting to threat, use of force or other forms of coercion, of abduction, of fraud, of deception, of the abuse of power or of a position of vulnerability, or of the giving or receiving of payments or benefits to achieve the consent of a person having control over another person, for the purpose of exploitation2

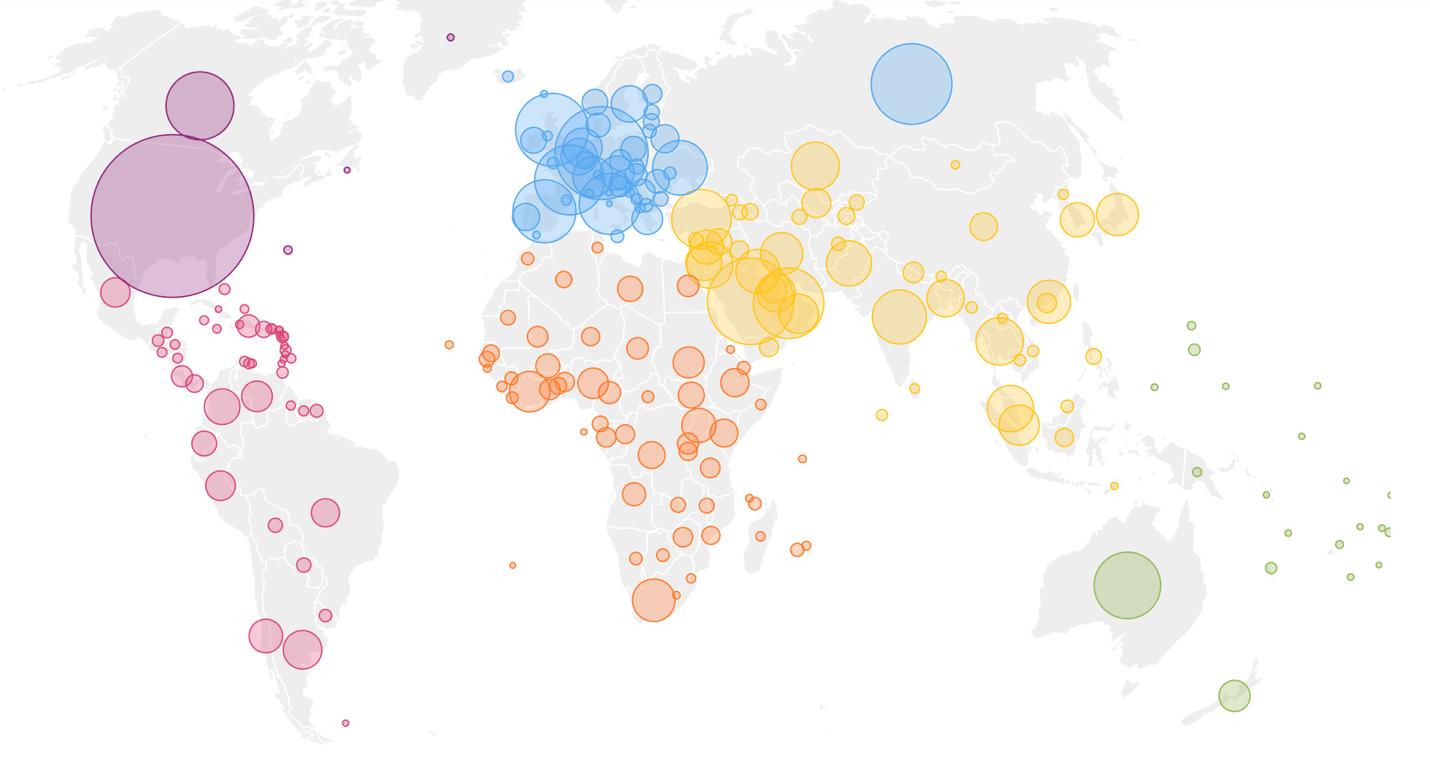

Map1|

5 CHAPTER

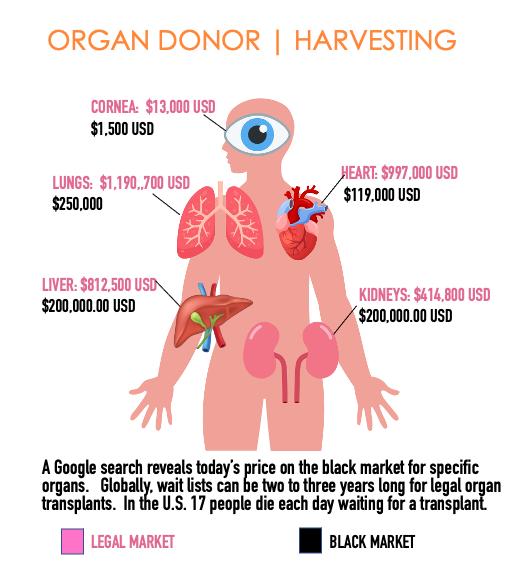

The Palermo Protocol and the Victim of Trafficking and Violence Protection Act (TVPA) passed by U.S. Congress in 20003 stipulate that if a victim is a minor and is being exploited, it is not necessary to prove that he or she was deceived, forced, or that a third person is involved in the handling or control of said person. Because she or he is a minor in exploitation, she or he is a victim of human trafficking The study and investigation of human trafficking is divided into two basic categories: labor trafficking (34%) sex trafficking (59%) with “other” (7%).4 “Other” can include forced marriage, forced participation as armed combatants, women forced to become pregnant in order to sell their offspring, begging or illegal trade in organs which introduces other serious human rights abuses.

However, in practice, the lines are not so clear. Often labor trafficking overlaps with sex trafficking. In many countries the penal code which typifies the crime of human trafficking includes elements which, globally, are not considered part of this crime (for example, illegal adoption in Guatemala). In addition, human trafficking is a situational crime, which means it is very adaptable. Traffickers shift modes and means as circumstances change. Human trafficking is a personal crime. “Despite the explosion of concern some of it fueled by misinformation about complex child sex trafficking schemes and kidnappings, data shows victims usually know and trust their traffickers.” 5

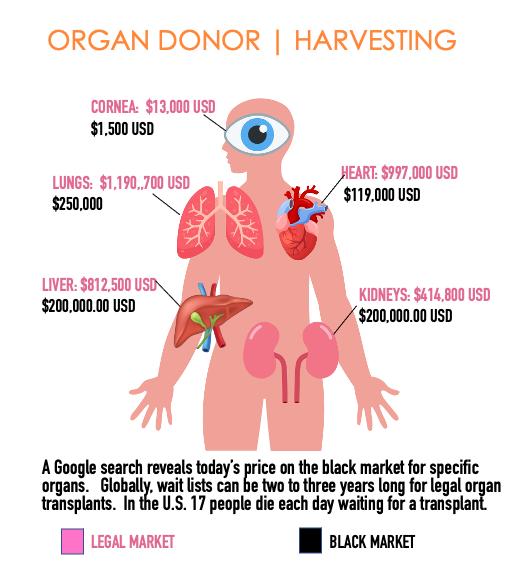

failure. 82% of patients are waiting for a kidney and this demand generates a market for illegal (black market) organs, increasing the risk of human trafficking for the purpose of organ harvesting. Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network website a branch of the US Department of Health and Human Service. Available: https://optn.transplant.hrsa.gov (Accessed July 19, 2017).

Before looking specifically at labor and sex trafficking, we should also mention the crime of human smuggling which sometimes becomes confused with human trafficking. Within the United Nations Convention Against Transnational Organized Crime (mentioned above) is the second protocol: The Protocol Against the Smuggling of Migrants by Land, Sea and Air.6 Human Smuggling involves the provision of a service – typically, transportation and / or fraudulent documents—to an individual who voluntarily seeks to gain illegal entry into a foreign country.7 The risk of human smuggling turning in to human trafficking is high, considering the smuggler’s opportunity for increased profit and the vulnerability of the undocumented migrant.

6

Labor Trafficking

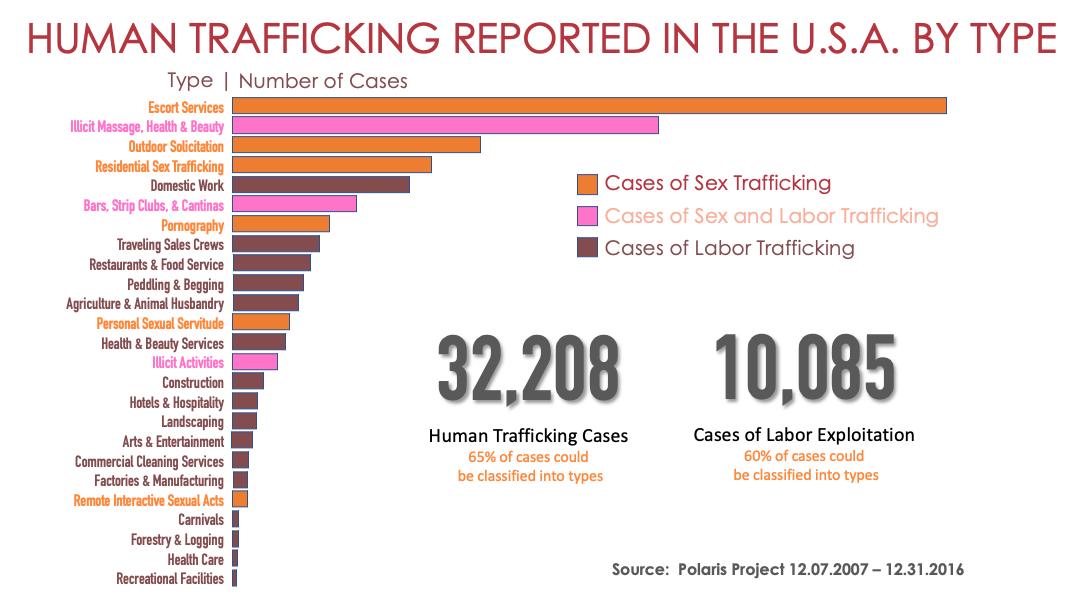

Polaris Project, a non profit in the U.S. tasked with operating the National Trafficking in Persons Hotline (TIP Hotline) reports the top five industries where victims of labor trafficking in the U.S. have been reported are domestic work, agriculture, construction, illicit activities (robbery, drug trade) and traveling sales crews.8 Globally, labor trafficking has also been detected in the fishing industry, mining and quarrying, garment factories, catering and manufacturing, hotels (housekeeping), restaurants, and street vending to mention a few. The 2018 Global

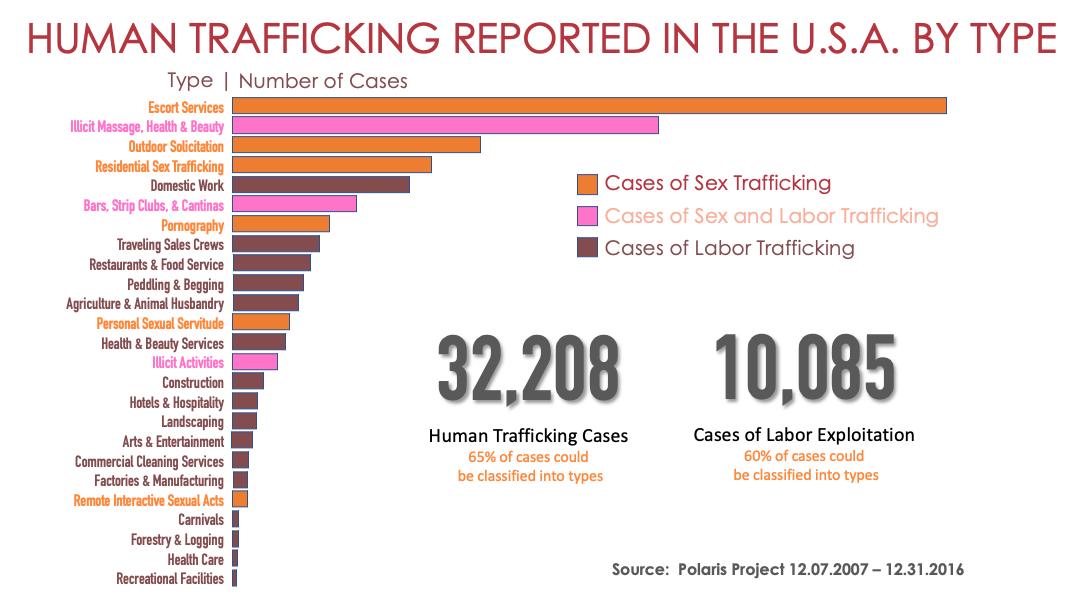

HUMAN TRAFFICKING IN THE U.S.A. BY TYPE

Information from Polaris Project’s Trafficking In Persons T.I.P. Hotline and Text to Report Between 2015-2018. Slavery Index mentions the top five products at risk of modern slavery as (1) laptops, computers and mobile

7

The following terms describe laws against exploitation in the U.S.:

Forced Labor is psychological coercion used to promote labor or services. Prior to establishing the TVPA, this crime came under the heading of Involuntary servitude, pursuant to the 13th amendment: “Neither slavery nor involuntary servitude, except as a punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted, shall exist within the United States, or any place subject to their jurisdiction.”10

Debt bondage (bonded labor, peonage) is probably the least known form of labor trafficking today, and yet it is the most widely used method of enslaving people.11 Victims of debt bondage are forced to “work off” a supposed debt, yet no legal document exists to define the amount owed or the terms of payment.

When looking at these numbers, the reports of victims of sex trafficking are almost three times as many as those of labor trafficking victims in the U.S. Many anti-trafficking workers are asking if there are so many fewer individuals being exploited for their labor in the U.S., or are victims of labor trafficking simply not being identified?

Regarding the low number of labor trafficking cases reported, in an April 26, 2022 podcast Professor Julie Dahlstrom comments on the recent evidence pointing to a lack of information among law enforcement agencies as a factor. “Some law enforcement agents didn’t even know there was a labor trafficking statute, or if they did, had difficulty discerning between what is labor trafficking and what is white [collar] wage theft, or wage exploitation.”12 She mentions labor trafficking is often seen as a civil issue, not a criminal issue, so law enforcement has trouble identifying labor trafficking as something within their purview.

8

TOP FIVE INDUSTRIES EXPLOITED IN THE U.S.A

TOP FIVE PRODUCTS AT RISK GLOBALLY

A further challenge is collecting evidence for a labor trafficking case. Digital evidence, or other corroboratory evidence, may not exist. A final challenge she notes is the unwillingness of a survivor to step forward and report. “This might be caused by fear of reprisal from the perpetrator, or simply a desire to move on with their life and receive wages.”13

Annie Smith, associate professor of law and director of the public service and pro bono program at the University of Arkansas School of Law, encourages prosecutors to pursue justice for labor trafficking victims: “Approached properly, prosecution presents an opportunity to disrupt labor trafficking, to publicly hold traffickers accountable, to secure restitution for survivors and to gain deeper insight into this form of abuse.”14

Smith cautions, however, that prosecution of labor trafficking alone is insufficient to confront it. To truly address labor trafficking, she points to the need for “systemic change that fundamentally alters the vulnerability of populations to exploitation and eradicates the extreme power imbalances between workers and those who employ them.”15 Governments should hold all entities, including businesses, accountable for human trafficking. In some countries, the law provides for corporate accountability in both the civil and criminal justice systems. U.S. law provides such liability for any legal person, including a business that benefits financially from its involvement in a human trafficking scheme, provided that the business knew or should have known of the scheme.16

Protect Me Project insists each community must be responsible for educating and mobilizing concerned individuals in the development of opportunities for less resourced sectors, as well as reporting exploitative practices. By knowing some signs, we can contribute to the solution. The U.S. Department of Health & Human Services Office on Trafficking in Persons offers these guidelines for identifying victims of labor trafficking:

• Victims are often kept isolated to prevent them from getting help. Their activities are restricted and are typically watched, escorted, or guarded by associates of traffickers. Traffickers may “coach” them to answer questions with a cover story about being a student or tourist.

9

• Victims may be blackmailed by traffickers using the victims’ status as an undocumented alien or their participation in an “illegal” industry. By threatening to report them to law enforcement or immigration officials, traffickers keep victims compliant.

• People who are trafficked often come from unstable and economically devastated places as traffickers frequently identify vulnerable populations characterized by oppression, high rates of illiteracy, little social mobility, and few economic opportunities.

• Women and children are overwhelmingly trafficked in labor arenas because of their relative lack of power, social marginalization, and their overall status as compared to men.17

Sex Trafficking

Sex trafficking involves recruiting, transporting, harboring, providing, or obtaining persons through force, fraud, or coercion for the purpose of exploiting that person sexually in various ways: for the production of pornography, lap dance, or live sex shows, phone calls, massage parlors, escort services, truck stops, residential brothels and sugar daddy arrangements. Protect Me Project is dedicated to preventing commercial sexual exploitation (CSE) and considers prostitution and other activities involving CSE as inherently harmful and dehumanizing.18

Survivor Rachel Moran describes her experience this way: “Prostitution, to me, is like slavery with a mask on, just as it is like rape with a mask on, and we were no more recompensed for the abuse of our bodies by our punters’ cash than slaves were recompensed by the food and lodgings provided by their slave masters.”19 Please visit our webpage protectmeproject.org/appendix to open “Appendix A” and consider why our vocabulary is so important as we address this issue.

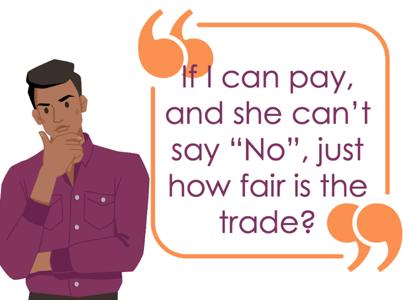

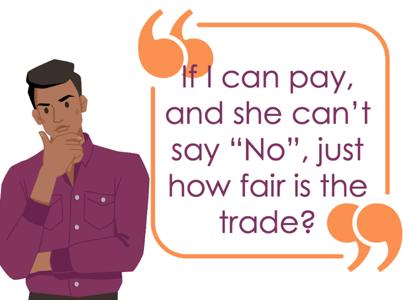

There is a sector of our global society who advocates for legalizing prostitution, supposing this would empower persons in commercial sexual exploitation. Siddarth Kara, an adjunct professor at Harvard who investigated commercial sexual exploitation in four continents from an economic perspective, addresses the concept of legalizing prostitution by saying, “Only governments, organized crime, and pimps benefit from legalization; women and children suffer state sanctioned rape and slavery.”20 Dorchen Leidholdt, Co Executive Director of the Coalition Against Trafficking in Women, writes:

Prostitution and sex trafficking are the same human rights catastrophe… Both are part of a system of gender based domination that makes violence against women and girls profitable to a mind boggling extreme. Both prey on women and girls made vulnerable by poverty, discrimination, and violence and leave them traumatized, sick, and impoverished. The concerted effort by some NGOs and governments to disconnect trafficking from prostitution to treat them as distinct and unrelated phenomena is nothing

10

less than a deliberate political strategy aimed at legitimizing the sex industry and protecting its growth and profitability.21

Because Protect Me Project exists to prevent commercial sexual exploitation, our capacity building and mobilization both focus on push and pull factors contributing to that industry. We must also be aware of and work to mitigate and report the injustice of labor trafficking in our communities.

MODERN HISTORY

Human trafficking is a very old phenomenon that has recently found greater exposure. Phrased differently, we are facing an old problem with a new name, exponentially growing for reasons which will become clear as we study the issue.

During the colonial era, women and girls, particularly of African and indigenous populations, were uprooted from their places of origin and traded for their labor, servitude and/or as sexual objects. Trafficking was perceived as a social problem at the end of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th through what was called white slavery. This concept was used to refer to the mobility and trade of white women, (European, Asian and American), to serve in prostitution or as concubines generally in Arab, African or Asian countries. At that time, the first hypotheses arose that these movements were the product of kidnappings, deceit, and coercion of innocent and vulnerable women with the aim of sexually exploiting them.

At the beginning of the 1980s, after several years of silence, the discourse on the trafficking of women for the purpose of sexual exploitation regained strength among different national and international sectors. This can be attributed, among other reasons, to the increase in transnational female migration that had been taking place since the end of the 1970s, or at least become more evident.22 The incidence of trafficking in almost all regions of the world and in many different forms was also increasing. In this way, the old definition of white slavery fell into disuse because it no longer corresponded to the realities of displacement and trade in persons, nor to the nature and dimensions of the abuses inherent to this scourge. Notice here a comparison by year of human trafficking statistics globally:

These statistics [next page] are estimates derived from data provided by foreign governments and other sources and reviewed by the Department of State. Aggregate data fluctuates from one year to the next due to the hidden nature of trafficking crimes, dynamic global events, shifts in government efforts, and a lack of uniformity in national reporting structures. The numbers in parentheses are those of labor trafficking prosecutions, convictions, and victims identified.23

11

YEAR PROSECUTIONS CONVICTIONS VICTIMS IDENTIFIED

NEW OR AMENDED LEGISLATION

2014 10,051 (418) 4,443 (216) 44,462 (11,438) 20

2015 19,127 (857) 6,615 (456) 77,823 (14,262) 30

2016 14,939 (1,038) 9,072 (717) 68,453 (17,465) 25

2017 17,471 (869) 7,135 (332) 96,960 (23,906) 5

2018 11,096 (457) 7,481 (259) 85,613 (11,009) 5

2019 11,841 (1,024) 9,548 (498) 118,932 (13,875) 7

2020 9,876 (1,115) 5,271 (337) 109,216 (14,448) 16

Victor Malarek points to four “waves” of trade in women: 1) mostly from Thailand and the Philippines in the 1970s. 2) Early 1980s, Nigerian and Ghanaian women. 3) Next, Latin Americans mostly from Colombia, Brazil and the Dominican Republic. 4) The fourth wave is made up of victims flowing from “the newly independent states” of the former Soviet Union. Today they make up more than 25% of the slaves in the world.24

With the increasing concerns about the growth of transnational criminal organizations developing among these “newly independent states”, intelligence reports pointed to sex trafficking and forms of forced labor as some of these organizations’ largest sources of profit. The first efforts to address trafficking in persons focused heavily on combating the sex trafficking of women and girls: “As the understanding of human trafficking expanded, the U.S. government, in collaboration with NGOs, identified the need for specific legislation to address how traffickers operate and to provide the legal tools necessary to combat trafficking in persons in all its forms.”25

It was at this time that, in the same year, the United States and the United Nations put forward legislation to prevent, suppress, protect from, and prosecute the crime of human trafficking.

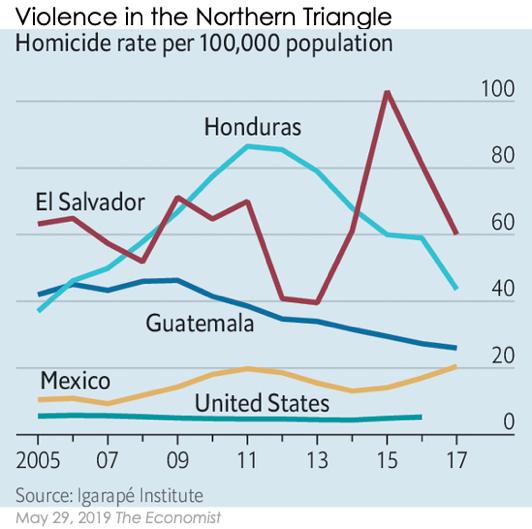

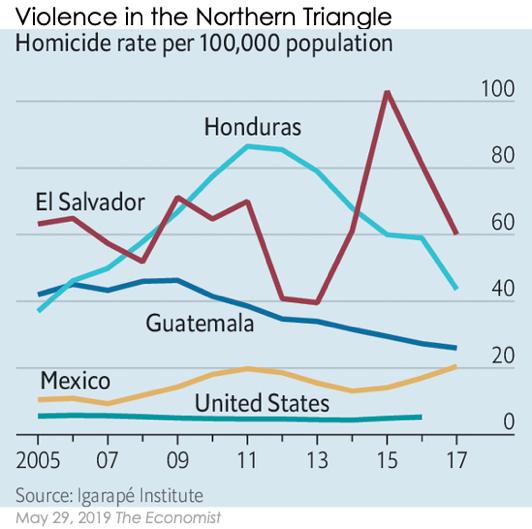

More recently, as the economic condition continues to spiral into critical deterioration in Venezuela, more than 5.6 million Venezuelans have fled to neighboring countries. Venezuelan women and girls previously were particularly vulnerable to sex trafficking in Colombia, Ecuador and Trinidad and Tobago. In 2020, 23 percent of victims identified in the Mexican state of Quintana Roo were Venezuelan.26 In the Northern Triangle of Central America, more than two million people are estimated to have left El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras since 2014, many fleeing poverty, violence, and other hardships27 and falling prey to traffickers en route.

12

PROTAGONISTS

For commercial sexual exploitation to be the business that produces billions of dollars a year ($150 billion annually according to Bradley Myles of Polaris Project), there must be certain players: a trafficker, a victim, and a consumer. Along the way, the victim will pass by witnesses (society), officials (immigration officers, police) and businesspeople (transportation and hotel or tourism industry, etc.). All are protagonists in this malevolent tragedy.

Trafficker

Who are the pimps or traffickers? In her book Domestic Minor Sex Trafficking: Beyond Victims and Villains, (Lutnik, 2016) the author warns us that the villain vs. victim model doesn’t contribute to strengthening the most vulnerable among us and mitigating exploitation. To the contrary, the dominant narrative about pimp controlled youth results in outrage and indignation directed at these individuals instead of a questioning of the structural factors that are the antecedents to such involvement.28 Julia O’Connell Davidson proposes that entry into pimping is often predicated on precisely the same poverty, abuse, neglect, depravity, and despondency that form the basis of entry into prostitution.29

As agents of change, the volunteers of Protect Me Project seek to partner with local stake holders in building strong families in our communities. This includes the young male trapped in a cycle of abuse, violence, poverty, and unrealistic social expectations.

After analyzing human trafficking cases, common traffickers noted are:

• Pimps

• Husband/boyfriend/family member/friend

• Gangs and criminal networks, both local and international

• Small or large business owners, business or factory supervisors

• Owners and supervisors of massage parlors and brothels, strip clubs, nightclubs and karaoke parlors

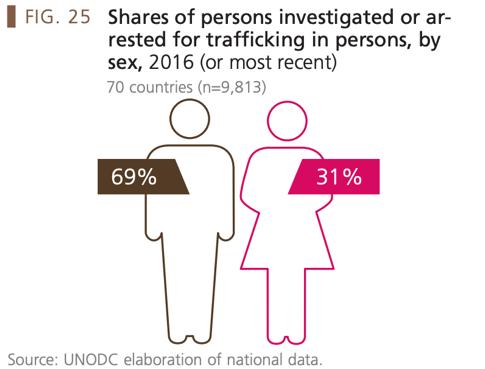

52% of those who recruit victims are men, while 42% are women and 6% are male/female teams. In 46% of the cases the recruiter was a person known to the victim. Most of the people involved in the human trafficking chain are natives of the victim's country of origin.30

13

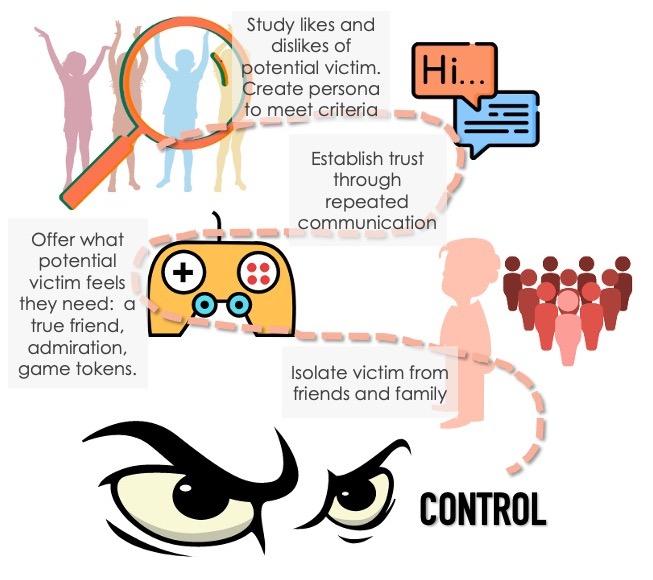

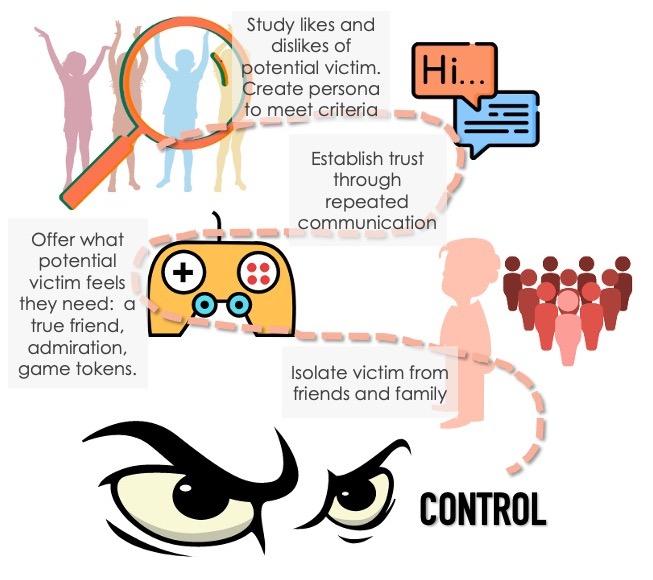

GROOMING

As can be seen, human trafficking is a very complex crime that generally takes place in an identifiable sequential pattern. Traffickers are experts at finding those moments when people are vulnerable, at working the angles, at manipulating reality and leveraging fears. The process is called grooming.31

Young people who have run away from home, who are vulnerable and lack experience on the street, are especially targeted. Loyola University investigated labor and sex trafficking among homeless youth through Covenant House ministries and found nearly 1 in 5 were victims of some form of human trafficking.32 Traffickers may scour specific locations such as bus stations, shelters, or local malls looking for someone without a safe place to stay or who they may be able to charm with their flattery and attention.33

Making the Connection:

The trafficker may recruit the victim indirectly through advertisements in the print media, online contacts, referrals from relatives or acquaintances, alleged employment opportunities, recruitment agencies, the offering of academic courses, through travel agencies, and through sentimental manipulation during courtship or even marriage. In all these cases, recruitment depends partially or totally on the use of deception, although there are also situations in which a victim is kidnapped or forced through rape and submission.

According to the U.S. T.I.P. Hotline, in 2020, 42% of trafficking victims were brought into trafficking by a member of their own families and 39% were recruited via an intimate partner or a marriage proposition.34 Some families “lend” their daughter into domestic servitude; sometimes in exchange for money, sometimes simply as an alternative to the extreme material poverty of their household and the lack of local education or job options.

Establish Trust:

In her book Survivors of Slavery: Modern Day Slave Narratives, (Murphy, 2014) Laura Murphy recounts the story of Shamere McKenzie, a native of Jamaica trafficked in the United States.

I will never forget the day I met my trafficker. It was a cold but sunny afternoon in January 2005. As I crossed over Ninety Sixth Street in Manhattan, New York, this car was approaching me. I stopped to look if it was my friend, who had a similar car, but this man came out of the car and introduced himself. Although he was not the typical guy I would talk to, he was extremely polite. That initial conversation made me completely forget how chubby he was. Nonetheless, we exchanged numbers. Within ten minutes, he was already calling my phone, but I was at work and had no time to speak.

14

Over the next several weeks, we had great conversations as we got to know each other (or should I say he got to know me). We had conversations about politics, single parents, the high number of men incarcerated, and how the government is building fewer schools and more jails. This was the kind of conversation I enjoyed. I became attracted to this man, as he had stimulated my mind. I easily looked past the fact that I was not physically attracted to him, especially when he told me he graduated from Morehouse College. He never told me his profession, as he said he wanted me to be with him for who he is, not what he does. In my mind, this was a well-educated, intelligent man, so he must have a great job. I began thinking that he must be used to females getting involved with him because of his profession and not for who he was as a person. Therefore, I never tried to find out what he really did for a living.

At this point in my life, I was working trying to save $3,000 I needed to go back to school at the end of January. When he learned about this, he immediately offered the money for me to go back to school. He said all I had to do was dance…35

During this “grooming” phase, the trafficker often manipulates the victim with feigned love and affection. They may have several conversations and form a bond over common interests and will pretend to care about what the would-be victim has experienced. This is crucial if he or she is to achieve lasting mental dominance over the victim. He or she will employ tactics such as human warmth, gifts, compliments, and sexual and physical intimacy. He or she will promise the victim a better life, easy money, and luxurious material goods. Drugs may be introduced, and the victim becomes addicted in a short time. When she or he begins to feel loved and safe, the next phase will begin.

Relationship Turns Sexual, Coercion and Isolation:

Traffickers need to put themselves at the center of victims’ lives to create a near total dependency. To do so, they distance their victims from anyone who might weaken their influence or contradict the messaging they’re providing. They might make off handed comments about how they don’t like the potential victim’s friends or make it so they become increasingly reliant on them by driving them to school or work and being there to pick them up. By isolating their victims, traffickers make it more difficult for them to reach out to others for help later on down the line.36

Pimps are continually “trolling” the internet, present on sites frequented by children and young people, posing as a boy or a girl in search of friendship.

15

The relationship develops without threat until the victim moves to meet the pimp in person or sends compromising photographs or shares her or his innermost dreams. The practice of “sexting” (sending nude or semi nude photos) exposes the sender to “sextortion” (blackmail or extortion based on the shame the person wants to avoid if the photo is published). It is then that the predator can intrude on the victim's life and begin to separate him or her from his or her support network.

The trafficker now breaks the victim in every possible way. In 2011 a DVD series called “Cross Country Pimping” was published in which pimps gave instructions on how to tame and control their women:

Weakness is the prime characteristic you look for if you want to control someone. If you don't find a weakness, you have to create one. You have to totally destroy someone's ego before that person will depend on you for their salvation.37

This phase often includes gang rape, verbal and sexual abuse, beatings, food deprivation, the offering of kindness and affection and the deprivation of both; isolation, and any tactic that serves to create dependency and break the spirit of the victim. The trafficker will move the victim to separate her or him from their family and friends, and to disorient her or him.

Abuse and Exploitation:

The way traffickers begin the process of exploiting their victims isn’t always transparent. They may start slowly, by pushing their victim to do things they might be uncomfortable with, like asking them to have sex with a friend once or arranging a date for them as a way to make some quick money. Over time, the victim may be conditioned to believe that what they’re being asked to do is “normal.” They may even feel like they owe their trafficker for all they have done for them or believe their trafficker when they say that the situation is just temporary or a way for them to reach their common goals, such as getting out of the sex trade and starting a family – or keeping the current, abusive family together.38

Once recruited the victim will have to be transferred to the place of exploitation. This can be to another point within the same country or to another country, or within the same city. The itinerary, and even the exploitation, can pass through a transit country or be direct between the country of origin and the country of destination. According to the Global Report on Trafficking in Persons (U.N. 2020) the majority of victims are exploited within their own sub-region.

Borders can be crossed openly or clandestinely, legally or illegally. Frequently, so-called "identity theft" is used, that is, the generation of identity documents that do not belong to the victim, not only passports but also birth

16

certificates, identity cards, driver's licenses, school reports, among others which makes it extremely difficult for the victim to prove their identity and seek justice.

Control:

Debt bondage: Once documents are confiscated the victim is often charged the cost of moving to another city or country. In this way a debt is created and the consequent relationship of dependency since the victims will never be able to earn enough to pay their captor. This is called "peonage" or "debt bondage." Being subjected to abuse, beatings, rape, blackmail and threats, the life of the victim becomes a painful and prolonged exploitation.

Mechanisms used by traffickers to control their victims: Many of the victims of human trafficking are exploited in open places and have contact with society: brothels, massage parlors, saunas, bars, restaurants, farms, factories, maquiladoras. How is it possible they don't run away or ask for help? Let's look at some keys:

• The use of violence or the threat of physical, psychological and/or sexual violence. Many times, children and young women are beaten or raped by their exploiters to keep them subdued. In the case of physical violence, the person is injured in places not visible to the public, such as the belly or thighs.

• The threat of being sent to prison or deported for being foreigners in an irregular situation, sometimes even highlighting the real or supposed relationships of traffickers with the authorities.

• Pressure or blackmail for debts or alleged debts contracted to create fear, dependency and psychological barriers between the victim and people who live outside the environment of abuse.

• Social and linguistic isolation occurs when dealing with foreigners who are unfamiliar with the country or the locality where they are (sometimes they do not even know where they are) and even worse if they do not speak the same language. In these cases, their identification documents (passports, etc.) are confiscated.

• The provision of alcohol or drugs is an increasingly used method.

• Threatening to kill a relative or even a pet.

• Threatening to release photos or videos as a form of blackmail (sextortion).

Officials

This group includes patrols in border areas, police, immigration officers, lawyers, members of the public ministry and judges. Some ignore the laws of their own country, while many take advantage of their leadership positions to squeeze money from traffickers. Still yet, some are direct consumers of enslaved people.

Kara interviewed the superintendent of the police unit responsible for investigating cases of commercial sexual exploitation in Thailand. When asked about the consumption of prostituted women by his officers, the officer cited

17

low pay (which promotes bribery and "kickback" pay), the human right (to exploit another person?), and the alleged “good” that the prostituted woman receives when she has a job.39 The superintendent reveals the cultural prejudices and ignorance that prevail in many areas of our world.

Speaking with a former federal agent from a Latin American country, he told us the corruption in his government was systemic, beginning with his president's office and permeating all government offices down to the local level.

Note the level of corruption indicated by Transparency International in the following diagram:

We recognize the economy is a major influencing factor when we talk about corruption. In her book Las Hijas de Juárez the author Teresa Rodríguez talks about the police force of that Mexican border city:

Their salaries were among the lowest of all city employees, attracting less-desirable candidates. They were only required to have finished elementary school. . . Those who had honorable hearts were often forced to retire from their posts or left the job in frustration.40

18

In every place where there is commercial sexual exploitation, the presence of corrupt officials is observed, some countries at a lower level but always present. If the victim cannot count on the help of those charged with protecting her, who can she trust?

Organized Criminal Networks

It has been said that “women are the new drug”. There are indications in the criminal world of the preference to trade in people over the trade in illegal drugs since it implies less risk with higher income. Kara offers figures outlining the profit margin a sex slave generates compared to the world's most lucrative legitimate companies.

Who are the ones running the commercial sexual exploitation industry?

Although cases of relatives offering a son or daughter for sexual sale for their own gain are common, most of the $150 billion in annual revenue generated by the human trafficking industry remains in the hands of organized criminal networks, also called “mafia”. Mafias are instruments of violence that are used to protect the interests of an industry, or business, or even political systems. In the case of commercial sexual exploitation, it has been proven that international mafias such as the "Yakuza" (Japan), the "Triads" (China), the Italian mafia, the cartels of Colombia and Mexico, the Nigerian, Albanian and Russian mafia; the Maras and Salvatruchas of Central America, just to name a few, control the slave “trade” routes. (See graph above by insightcrime.org)

Society

We want to make note here the similarity between the methods used by traffickers and those used by 8 year old bullies. Both seek to intimidate, exploit, and control their victims. In both cases there are perpetrators, victims, and bystanders. If we can “get there before the trafficker” and offer alternatives to these behaviors, might we be able to offer a future with options for this generation? Perhaps beginning with bystanders, AKA society.

Protect Me Project is calling for new activists: people who are informed about the problem and who raise their voices against this atrocity. Not just human trafficking, but each of the push and pull factors which are at the root

19

of the problem. Our children and sisters depend on us to engage the issues. We are the streets these victims are sold on. We are the neighborhoods where these slaves are held captive. We are the families of those who spend their money for sex acts. We are the parents raising bullies.

The Declaration of the Basic Principles of Justice for Victims of Crime and Abuse of Power of the United Nations (1985)41 says in clause 16 that persons who are likely to be in contact with victims (such as police, justice officials and community health and social services staff) should be trained to identify them and be sensitive to their needs.

What role could you play in that training?

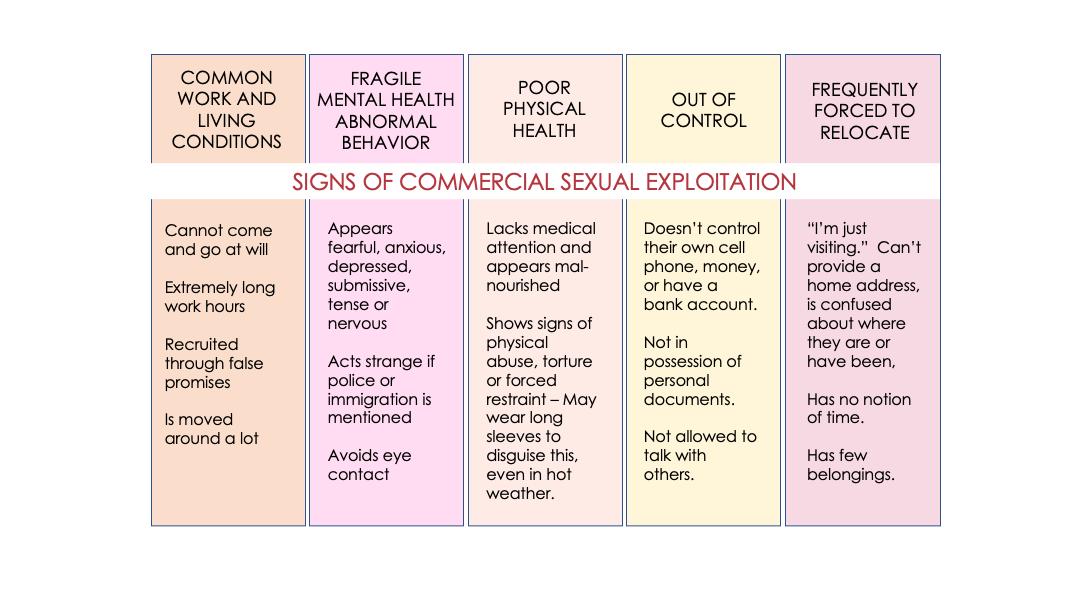

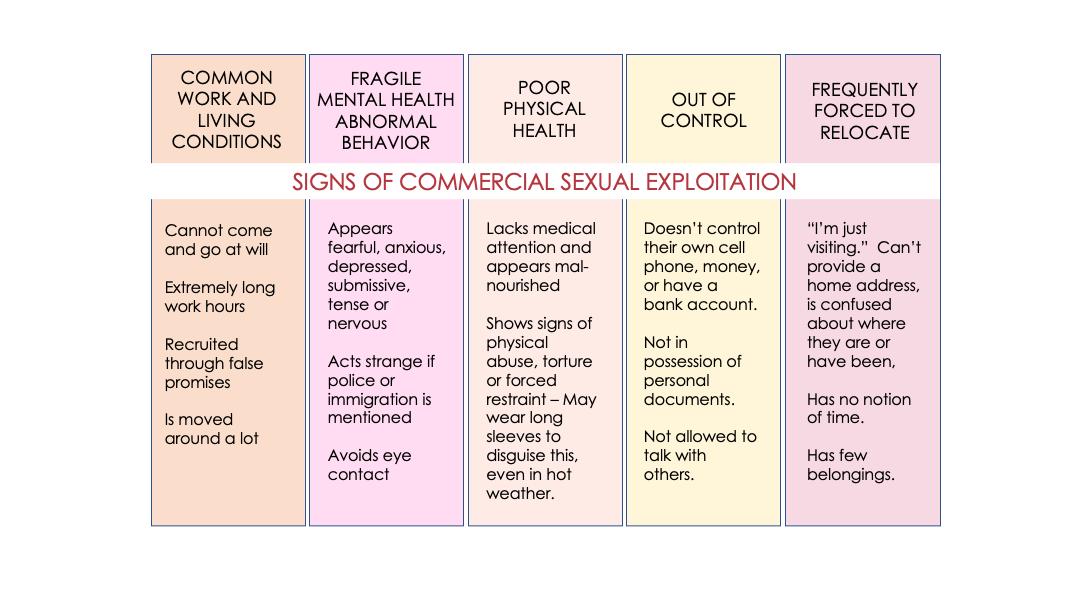

Notice the signs that society can observe when the individual is being enslaved. (See page 43) The presence of just one sign may not be alarming, but the presence of more than one should prompt a call to the Polaris Project’s T.I.P. Hotline number (888 3737 888) to report. Women and children who are victims of commercial sexual exploitation depend on a society that exercises zero tolerance. Will you be part of the new activists?

We have what we tolerate. Our volunteers have all heard facilitators say this, and it is true. As parents, we get the behavior from our toddlers that we tolerate. As spouses, we have the type of relationship we tolerate. As long as we are comfortable with things as they are, we will never be agents for change.

20

Map2|

Photograph of spikes in a cross at the border between El Paso, TX and Cd. Juárez, CHIH – one spike for each woman whose life has been snuffed out. Some estimate more than 5,000 women have disappeared from this border city since the 1990s.

21

CHAPTER TWO: VICTIMS

“There is no us and them. There is simply a lot of this and that inside us all.” Kathy Brooks43

“Referring to these young people as “victims” ignores the resilience that many of them show, as well as the fact that they are doing the best they can given their options and limited support.”44

Who among us wants to be viewed as a "victim"? It feels weak and powerless. So, let’s define our use of the word “victim” here: a person who has suffered direct physical, emotional, or pecuniary harm as a result of the commission of a crime.45 By using the term “victim” we place the onus of guilt directly on the perpetrator of the crime and not on the person exploited. We use the word “victim” to refer to a person being exploited. Once that individual exercises agency, the appropriate term is survivor.

It is true that not all persons in prostitution are trafficking victims. Yet, we would argue, they are victims of commercial sexual exploitation. What is the difference? The person in prostitution as an adult receives money or goods in exchange for sex acts and might choose to deny engaging in sex acts with a given consumer. The trafficking victim has lost all agency, cannot accept or deny a consumer, and does not earn a wage for his or her participation in sex acts. Both suffer the exploitation of their sexuality.

The route to prostitution is more complicated than the villain/victim narrative. Sometimes it appears to be by choice, even if that choice is based on hopelessness. In other words, material poverty places the victim in prostitution because they do not perceive options. In some cases, it is a decision based on feelings of low self esteem created and fueled by abusive experiences. In the next chapter we speak in detail of the progression from sexual abuse as a minor toward commercial sexual exploitation. One survivor describes her entrance to “the life”:

It started, not with the first time I traded sex for money, but with the dysfunction of my family. The next steps on that path were the educational disadvantages and homelessness that I experienced as a teenager. It is a familiar story among prostituted people. The most common that I have met.46

22

“If you were born to my parents and put in the exact same situation, you would be writing this letter right now.” (Survivor)42

The legal reality of the trafficked person is that she or he was (or is) the victim of an abuse of power. She or he was not (and is not) responsible for crimes committed during captivity. (See Appendix B at protectmeproject.org/appendix)

It is crucial, however, to be clear: Yes, she or he is responsible for her or his life. A trauma informed lens upholds each person as an active agent of their own recovery process.47 Any service or program that ignores this fact misses an important piece in rebuilding her or his holistic health. Any intervention on their behalf must be informed by the trauma experienced and must empower her or him to make their own decisions and include multi sectoral support as they move toward full self actualization.

Understanding the above, we use the word “victim” as a legal or criminal term. According to the Palermo Protocol, a minor in prostitution is effectively a victim of human sex trafficking, even if she or he does not self identify as such. There is no need to prove that he or she was deceived or forced, or that a third person is involved: being a minor, he or she is a victim of trafficking.

A DAY IN THE LIFE

In daily life, victims of sex trafficking endure unspeakable acts of physical brutality, violence, and degradation, including being raped by so called clients and pimps. One survivor from Connecticut shares her experience, “The beatings were one thing, but being called a bitch every second and being told that you will never be anything but a prostitute was not something I could deal with anymore. So I told him to kill me.”48

Some are subjected to forced abortions.49 Dependencies on alcohol and other drugs may be acquired since these anesthetize and help mitigate physical and psychological pain.

Victims live in fear for their lives and for the lives of their family and friends. One trafficker explains, “Not everyone likes the job. There are cases where girls have to get forced, through rape, beatings, or torture. Once she starts to fear for her life, she gives up the resistance and starts to work.”50

Individuals caught in commercial sexual exploitation suffer psychological reactions as a result of both physical and emotional trauma. In addition, they contract sexually transmitted diseases that, all too often, involve a breakdown in health that can have lifelong implications.

23

Often, victims do not get medical attention in time. When they are taken to the doctor it is usually when it is already too late for a cure, and this hastens their death. “Alarmingly, studies have shown that only 47% of female prostitute[d persons] are aware of their HIV status, less than 50% of these women had a health screening in the previous year, and on average had 17 sex partners per week.51 If they survive the physical, psychological, and spiritual impact of these experiences, the impact on the victim is devastating and long lasting.

From the beginning the victim may believe she or he will be a domestic worker, a farm worker, or sometimes a nightclub dancer or involved in prostitution. It may only be upon reaching her or his destination that she or he becomes aware that they, too, are a victim of exploitation.

HOW MANY?

Reliable statistics for human trafficking are hard to come by. Human trafficking is a clandestine crime, and few victims and survivors raise their voices for fear of reprisals, punishment, or ignorance of what is really happening to them or what their rights are.

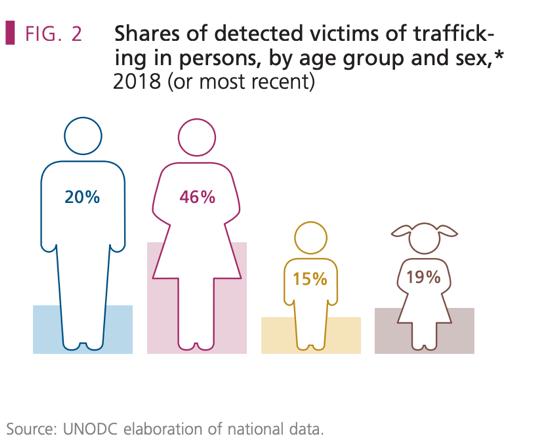

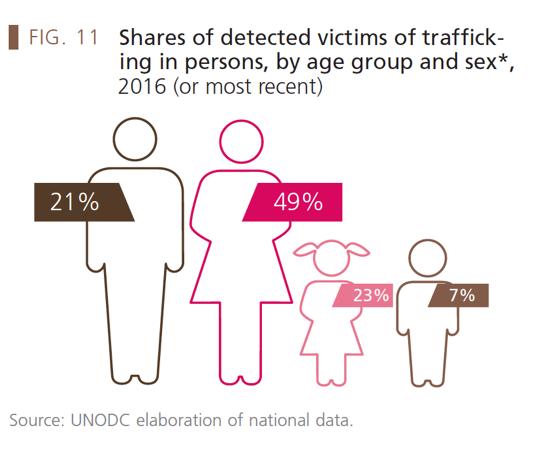

The 2018 Global Slavery Index reports a 2016 statistic that 40.3 million slaves remain in our world. This research was conducted in 25 countries, covering 44% of the global population.52 The International Labor Organization (ILO) offers the figure of 24.9 million who exist under the yoke of forced labor.53 They claim it is a conservative estimate.

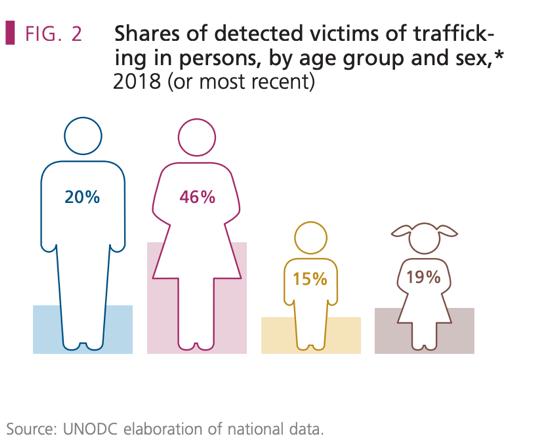

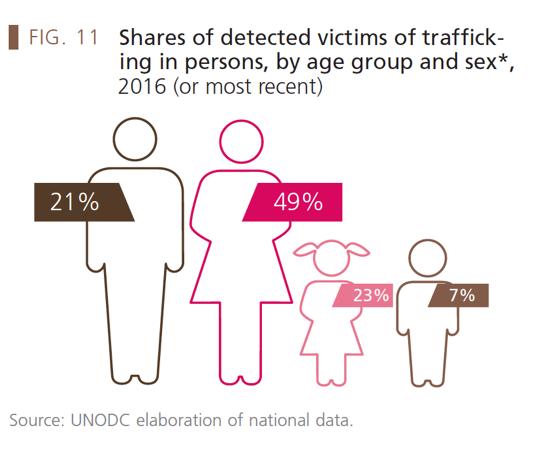

According to the latest Global Slavery Index, women and girls represent about 70% of slaves and adults are more affected than children (74%). Of the 24.9 million slaves, the ILO estimates 4.8 million are sex slaves, 16 million are exploited in the private sector and 4 million are in forced labor imposed by the state.54 However, in a speech in

24

April 2012, the executive director of UN Women, Michelle Bachelet, announced that, “80% of trafficked people are used and abused as sexual slaves.”55

The disparity between these statistics is a good example of how difficult it is to guesstimate the number of people who are victims of modern slavery. The variation is due to many factors, among them the lack of uniformity in terms and definitions, the variety in methodology when investigating, the focus of each investigation and the invisibility of the population in question.

Many organizations working with victims claim that women and children who are victims of forced labor are also victims of sexual abuse and often commercial sexual exploitation. This nuance is not reflected in published statistics.

Official statistics estimate that between 14,500 to 17,500 people enter the United States each year as victims of trafficking.56 The 2021 T.I.P. Report U.S. Country Narrative indicates the top three countries of origin for victims identified by federally funded providers in the United States are the U.S., Mexico and Honduras57 When we talk specifically about commercial sexual exploitation, the figures offered by the C.I.A. from 1999 to the present are between 45,000 and 50,000 women, boys and girls are exploited annually in the sex trade in the United States.31

In 2005 the International Labor Organization (ILO) published its estimate of the annual income generated by the illegal industry of forced labor and human trafficking: $32.5 billion dollars. Today, on the ILO website, they cite an income of $150 billion a year. Before you deduce that there has been a 500% increase in the rate of slavery over the last two decades, we must insist that statistics on the crime of human trafficking come from a variety of sources: many NGOs, government departments independent from each other, and each in different geographical regions and cultures. This makes harmony in terms and calculations difficult.

In an interview with the Mexican journalist Lydia Cacho, she comments:

It is hard to know if commercial sexual exploitation and child pornography are more prevalent now or if we are simply better informed. This scourge exists because we have agreed not to see it, especially in Mexico where being a witness means risking your life, or the life of your family.32

Instead of focusing on statistics, one advocate recommends focusing on individual personal survival stories, or new government initiatives, or fledgling academic research efforts until better statistics are available.

25

RISK FACTORS

The average age of induction to the world of commercial sexual exploitation is difficult to know. Many cite the age between 12 14 years, referring to research done in 2001 that today is considered unreliable. According to the International Organization for Migration (IOM) most victims of human trafficking are between 18 and 24 years old,58 but this does not indicate how old they were when they entered the world of exploitation.

In the United States, Polaris Project reports that, of the 123 survivors they helped in a given time frame, 44% said they were under the age of 17 when they entered prostitution. The average was 19 years, although they emphasize that the vast majority of people who call the emergency line are adults.59 Loyola University interviewed 641 homeless youth in ten cities in the United States. They found that one in five was trafficked, and the median age of entry into prostitution reported was 16 years.60 Research suggests that the average of a sex slave in the United States is around 20 while the average age outside of the United States is approximately 12 years old.61

Conclusion? Although there is much research, we do not have reliable statistics to say for sure the average age at which exploitation begins for most enslaved people.

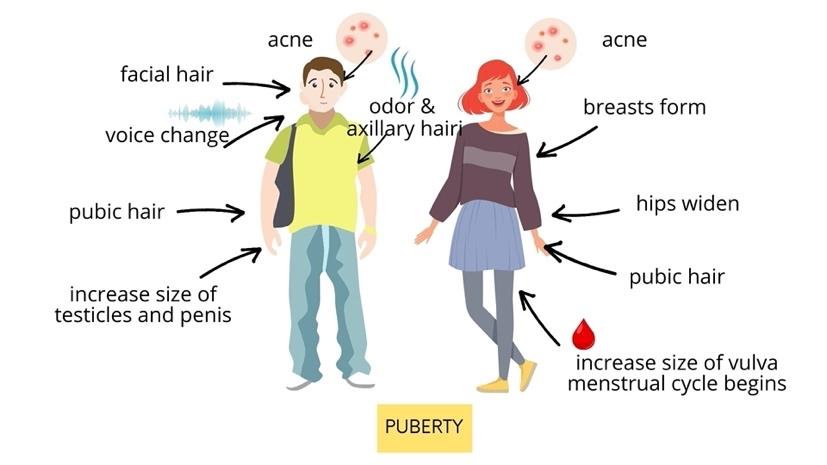

What we do know is that age is a primary risk factor (read “vulnerability”) and that adolescents are more susceptible to advances and tactics of coercion, deception, and intentional manipulation. The emotional and economic dependence of a minor, along with his or her limited ability to analyze decisions and calculate their consequences, makes him or her especially vulnerable to the predator. For all these reasons traffickers spend time in or near places where young people gather: social media sites, shopping malls, schools, parks, bus stops, shelters, and so called "farms."

Another risk factor noted among exploited individuals is identifying as LGBTQ+. According to Gallup, 5.6% of adult population in the U.S. identifies as gay62, but a disproportionate percentage of persons from this population are commercially sexually exploited.63 Most of the young people who self identify as other than their biological sex and receive help cite the rejection of their sexual choice by their families as the reason for finding themselves on the streets, and therefore exploited.64 According to studies by the Mayo Clinic, members of the LGBTQ community

26

suffer more from anxiety disorders, lower levels of mental health, and chronic emotional conditions which are all contributing factors to their vulnerability.65

For some, prostitution offers a space to experiment with their sexuality. Others are looking for an adventure, something exciting, or the economic resources to obtain the goods coveted by their contemporaries: nails, shoes, cars, clothes, technology. In other cases, material poverty convinces the person that prostitution is his or her only option. Mental health is another factor that appears in so many cases of trafficking worldwide. There are many cases in which a mentally disabled person is exploited, but many other cases in which the adults in charge of them suffer from mental health problems, which makes the son or daughter feel responsible to support the family, or run away from home to escape abuse and find a place to belong.

A final notable factor that draws vulnerable people into the sex market is love. One survivor offers, “Most girls are not motivated by lust or greed or gluttony or anger or envy or pride or sloth; they are attracted by love.”66

Traffickers prey on people with little or no social safety net. They look for people who are vulnerable due to their illegal immigration status, poor command of the language of the country where they are located, and who may be in vulnerable conditions due to economic problems, political instability, or natural disasters.

Here we want to highlight a few specific risk factors.

Sexual Abuse of Minors (SAM)

“Child sexual abuse is, by far, what I have heard the most mentioned in discussions regarding the commercial sexual exploitation of minors as the factor that predisposes [the victim] to being commercially exploited.”67

A 1983 study found that 60% of 200 individuals involved in the sex trade (adults and minors) were sexually exploited as minors.68 A 2012 study found that 40.8% of 115 individuals who identified themselves as “sex market participants before the age of 18” also self reported as victims of child sexual abuse.69 Patricia Murphy, in her book Making the Connections (1993) cites two studies where they calculate that between 65-85% of the prostituted women in their research were victims of "child rape". In fact, the author states that some clinicians

27

consider this number to be close to 100%.70 “Many of the organizations that provide services to victims of commercial sexual exploitation of minors have confirmed these higher statistics to me.” says Holly Austin Smith, survivor, author, and activist.71

Rachel Moran writes, “I discovered that childhood sexual abuse was common among the girls I knew in my life and, in many cases, was the primary factor that caused them to run away from home.”72

Prolonged and repeated trauma usually precedes entry into prostitution. From 55% to 90% of prostitutes report a childhood sexual abuse history. Silbert and Pines noted that 80% of their interviewees said that childhood sexual abuse had an influence on their entry into prostitution. A conservative estimate of the average age of recruitment into prostitution in the U.S.A. is 13 14 years.73

The World Health Organization (WHO), basing its report on several global investigations, calculates that approximately 20% of girls and between 5 to 10% of boys suffer child sexual abuse.74 Based on retro research (in which adults report abuse that occurred in their childhood) 1 in 4 girls and 1 in 13 boys in the U.S. will be abused before reaching pubertal age according to the CDC.75 D2L.org states that 1 in 10 children is abused before their 18th birthday.76

The body of evidence points to sexual abuse of minors as a common factor driving minors onto the street. Being homeless, whatever the push or pull factor, is what pressures him or her to sell sex acts to survive. Other risk factors add to that scenario.

Alexandra Lutnik warns us in her book entitled Domestic Minor Sex Trafficking: Beyond Victims and Villains not to limit the topic of the presence of minors in the sex trade to the discussion of sexual abuse of minors. The misconception that child sexual abuse is the primary factor leading to commercial sexual exploitation may keep us from focusing on the need for quality economic opportunities. “We must talk about poverty, which is inseparable from racism, gender inequality, socio economic class, and lack of community.”77

Misogyny

More than poverty, military conflict, and other social disasters that drove rural women into the clutches of sex traffickers, this was the primary factor wherever I investigated the phenomenon of sex trafficking: millions of women lived in a world that overwhelmingly loathed them.78

Misogyny is a social concept that describes an attitude of hatred or contempt towards the female sex. “Every day, on average, at least 12 Latin American and Caribbean women die for the sole fact of being a woman.”79 According

28

to F.B.I. data, female intimate gendered killings in the United States happen at a rate of almost 3 every day.80 The lack of legal and social equality for women and girls is a breeding ground for commercial sexual exploitation. Where women and girls are reduced to mere objects and viewed as economic assets or liabilities, a climate is created in which they can be bought and sold.

The abusers, but also many judges, police officers, prosecutors, and public ministries, are traditional men and women who have been educated with stereotyped sexual roles, and fervently reproduce them. . . The word of a man has much more symbolic value and social weight than the word of a woman and a girl. Women who have power in the judicial environment often reproduce sexist values to be accepted in a world that for centuries was male territory.81

We can't think of eliminating sexual abuse of minors without understanding adult sexual violence as well, because they are correlated. To the degree there continues to be an imbalance of power between men and women, there will continue to be exploitation of the latter.

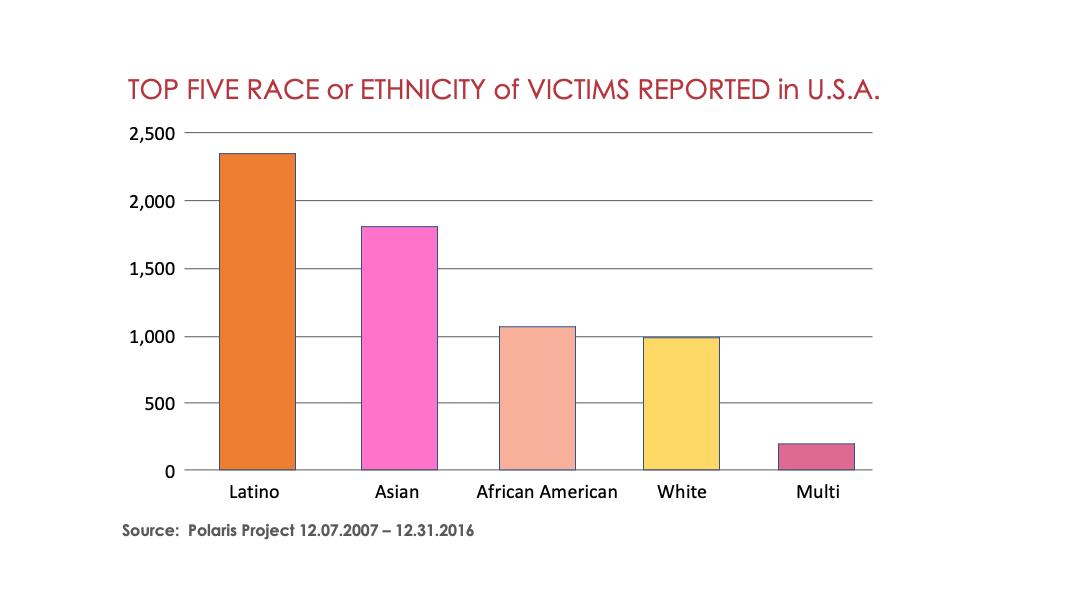

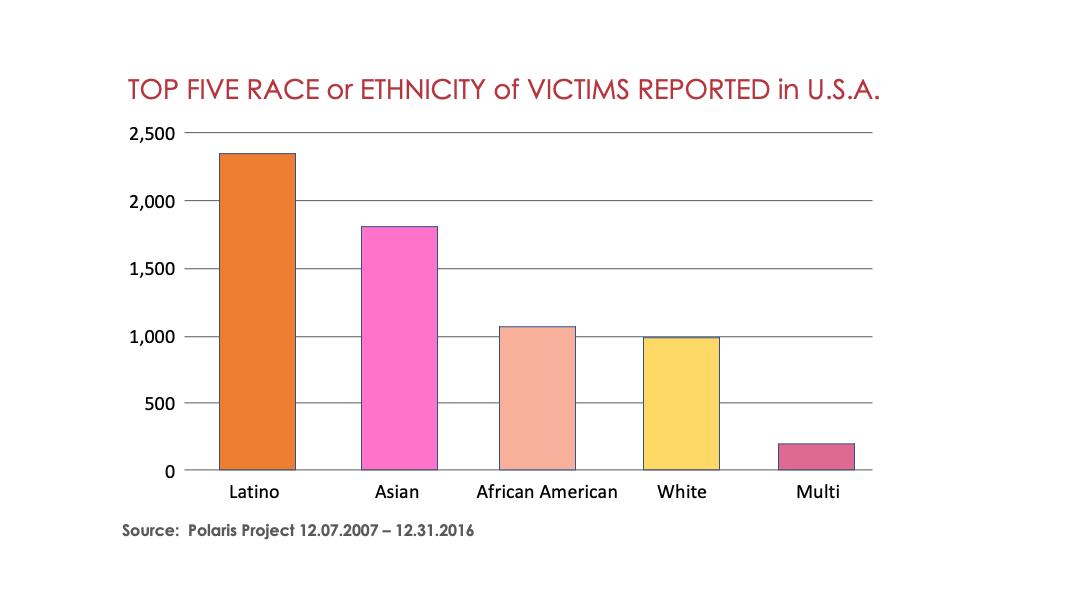

Race

The Polaris Project 2018 Statistics from the National Human Trafficking Hotline ethnicity of victims of human trafficking. (See graph above.) Based on these statistics, almost double the number of Hispanics report being exploited in the U.S. compared to Asians, and over twice the number of African American or Caucasian.

The fact remains, child sex trafficking survivors are disproportionately girls of color. The following statistics focus on Black victims in the U.S. In King County, Washington, 52% of all child sex trafficking victims are Black and 84% of youth victims are female, though Black girls only comprise 1.1% of the general population.83 In Multnomah County Oregon, 95% of youth victims are female, and 27% of child sex trafficking victims are Black, though Black people comprise less than 6% of the population.84 In Cook County, Illinois 66% of sex trafficking victims between 2012 2016 were Black women.85 In Nebraska, 50% of individuals sold online for sex are Black, though Black people comprise only 5% of the general population.86

29

We must consider a larger picture as we evaluate the push and pull factors fueling slavery in our communities. Why are persons of color disproportionately marginalized? Are we looking for this vulnerability in our communities? Are we strategizing and collaborating to mitigate the circumstances creating these vulnerabilities and perpetuating unjust systems? Are we investing in development of assets among these populations?

Lack of Schooling

In some cultures, girls are denied the opportunity to go to school and instead are forced to stay home to do household chores. They remain untrained and uneducated. Girls are frequently abused within their families, making commercial sexual exploitation networks appear as a false escape route from exploitation and domestic violence. For many people, migrating or looking for work outside their communities is not only an economic decision, it could be a search for personal freedom, better living conditions or a means to support their families.

Children and adolescents who are not in school can easily fall prey to traffickers. Of the world’s 787 million children of primary school age, 8% do not go to school. That’s 58.4 million children, the majority being girls.87 Significant progress has been made toward achieving universal primary education. Globally, the adjusted net attendance rate reached 87 per cent in 2019, and about four out of five children attending primary education completed it. Additionally, over the past two decades, the number of out of school children was reduced by over 40 per cent.88 Yet, according to UNICEF, still today there are 115 million young people (15 24 years old) who are illiterate.89

The lack of schooling produces several effects: children will have fewer employment options, fewer social tools, and less contact with a potential support network in their community. Not being in class means a lot of unsupervised time, which exposes them to gangs, drugs, illegal businesses, and predators. If "work" is what prevents them from attending classes, it brings with it a whole series of concerns about their physical (food, rest, abuse), psychological, social, and spiritual health.

Regarding the prevention of trafficking, most prevention messages are aimed at children and adolescents who can read, with the illiterate being at a clear disadvantage. This is something Protect Me Project teams must take into consideration, even as we mobilize for the “100 Schools Project”: how do we reach the children who do not attend school?

There are various models in Latin America of NGOs, church ministries and individual advocates who have risen up to create a safe and supportive environment. “Girls of Promise” in Costa Rica90 offers a place where teenage girls can go after school. In a marginalized neighborhood, the girls grab a bite to eat, hang out with their friends, get

30

help with their homework and learn new skills. “M.D.A.” in the Dominican Republic91 sponsors events for young women that highlight the dignity of women and explore options for their future. “Zo¡e”92, also present in a marginalized area where sex tourism is rampant, is a drop in center providing physical, intellectual, emotional, and spiritual support. Friends in Chile operate a feeding center for food impoverished families with ongoing educational opportunities for single moms.93

Homelessness

Children and adolescents without adults to care for them are vulnerable to trafficking and exploitation. Parents provide an essential safety net for their offspring. Cases in which minors are forced to leave their homes – due to extreme material poverty, fleeing abuse, being rejected, and expelled or decide to go in search of love or fortune or exciting experiences, are at high risk of being exploited.

Those living in institutions are targeted by traffickers and, if raised in an institution, often lack community ties and opportunities, and may also be at greater risk. Assessments carried out by the International Labor Organization (ILO) have found that orphaned children and adolescents are much more likely to work in domestic service, commercial sex, commercial agriculture or as street vendors.94

Children separated from their parents due to material poverty, armed conflict, violence, or migration may live with more distant relatives or with a transitional family. Without guidance, without a sense of belonging or opportunities, they will be in a position of greater risk of being victims of exploitation.

To develop and implement effective policies and programs, we must be willing to acknowledge the diversity of young people who deal in sexual acts. We will need to explore the ways in which our constructions of childhood and victimization can contribute to the marginalization of young people and assess what we as a community can do to offer them alternatives, so these young people do not see selling sexual acts as their only option.

Lack of Birth Registration

Children and adolescents who are not registered in official records are more likely to be victims of trafficking. It is estimated that 41% of the children born in the year 2000 were not legally registered at birth. Today it is said that globally 1 in 4 children does not exist legally.95

Lack of birth registration can also reinforce existing gender gaps in areas like education. Worldwide, 132 million girls are out of school, and these girls are more likely than out of school boys to never enroll in school. Not having a birth certificate makes it even more difficult for them to do so. And girls without

31

birth certificates who are unable to legally prove their age are also even more susceptible to child marriage, after which they are much less likely to complete their education.96 When children lack a legal identity, it is easier for traffickers to hide them. It is also more difficult to track them and monitor their disappearance. Additionally, without a birth certificate it is difficult to confirm the age of the child and hold traffickers accountable for their actions. Lack of identification may mean that those who were trafficked between countries cannot be traced and therefore cannot be easily returned to their communities. The falsification of adoption documents, identity cards, or birth certificates are ways used by the trafficker to hide the identity and/or age of the victim.

Natural Disasters and Armed Conflict

During conflicts, children and adolescents may be abducted by armed groups and forced to participate in hostilities. They may be victims of sexual abuse or rape. Kilborn and McDermid tell us, “Rape and forced incest used as weapons of war break down the morale and fabric of a society. These tactics used regularly and mercilessly in recent wars, such as in Cambodia, Liberia, and Bosnia, certainly capture the meaning of exploitation.”97 Conflicts contribute to unprotected borders, increasing the ability of traffickers to move people. Finally, the flow of international workers that occurs during a crisis can increase commercial sexual exploitation.98

In fact, when United Nations troops enter a region, the trafficking rates tend to rise. United Nations troops have been implicated in sex slavery and human trafficking cases in Mozambique, Bosnia, Kosovo, Cambodia, Congo, Haiti, and elsewhere. Despite the fact that in 2002 the U.S. military enacted a stringent no tolerance policy forbidding military personnel and contractors from engaging in sex trafficking in war zones and providing for criminal prosecutions of those who purchase sex, by 2010 there had been absolutely no prosecutions.99

Political and economic upheavals contribute to increased vulnerabilities among populations who are already vulnerable. Siddarth Kara, a Harvard University Fellow, points to the fall of the former Soviet Union as a catalyst for sex trafficking: “Capitalism and democracy are almost always more desirable than oppressive, state controlled regimes, but during this fragile transition period, many post communist countries became sources of trafficked sex slaves.”100

Disasters that disrupt livelihoods or result in the death of one or both parents make children and adolescents vulnerable to exploitation.

32

These crises create chaos and the collapse of official structures to uphold justice, which decreases the chances that traffickers will face legal consequences for their actions.

Migration

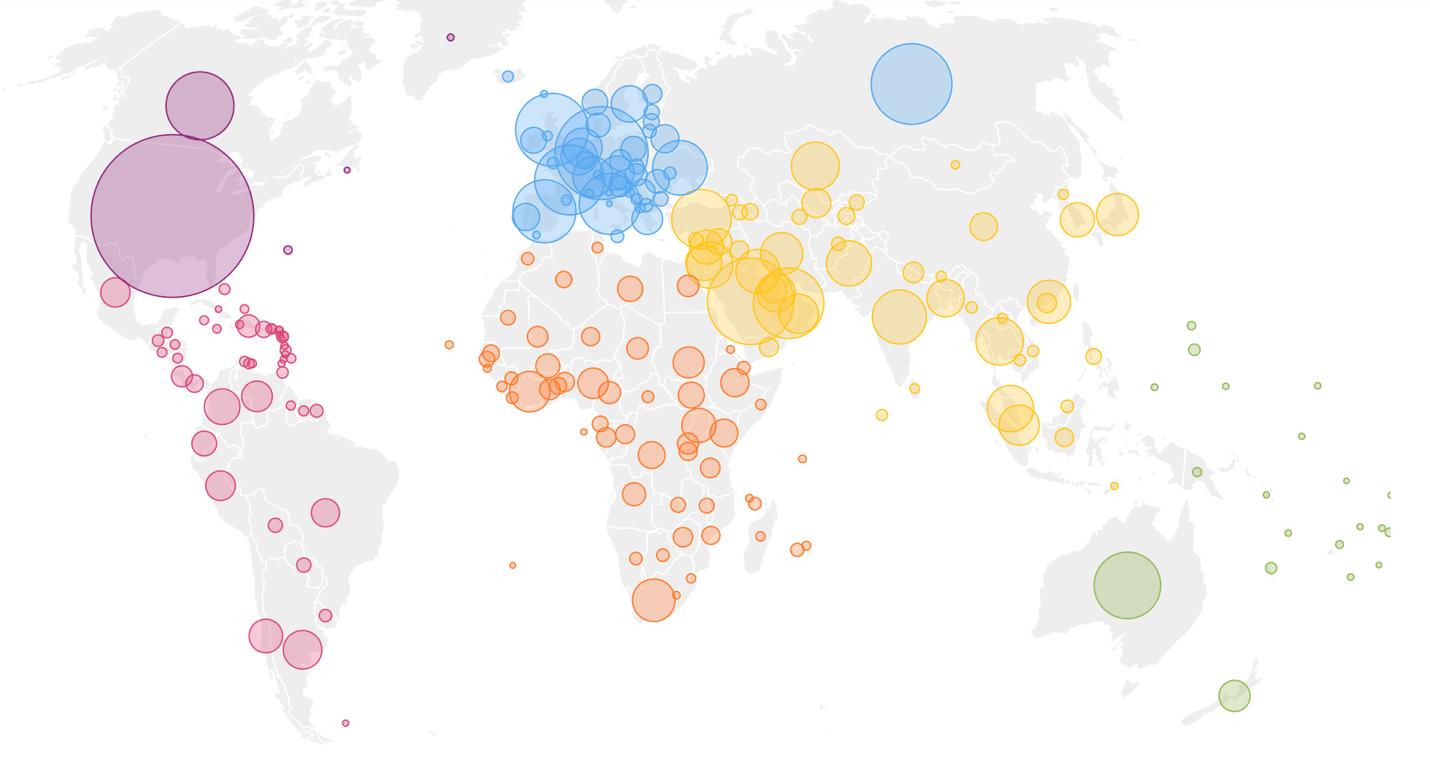

Map3|

The map (above) from the World Migration Report 2022, shows concentrations of migrants. The United States of America is displayed here as the largest destination country for migrants, constituting 15.3% of the population.101

When an individual chooses to relocate, the simple fact of leaving behind relational networks and what is familiar creates certain vulnerabilities. When the destination is another country, that migrant might face language barriers, isolation and lack the connections needed to obtain employment. These issues are magnified if the migrant is undocumented.

In an April 26, 2022 interview with Professor Julie Dahlstrom, the Director of Immigrants’ Rights and Human Trafficking Program at Boston University School of Law, Dahlstrom explained, “Some people think of non citizens

33

being brought to the U.S. and then trafficked, but while that does occur what we see in many of our cases is non citizens who are in the U.S. and undocumented, then they are recruited by perpetrators.”102 Traffickers take advantage of the undocumented status to threaten the migrant with deportation, imprisonment, physical harm or harm to their family back home.

Even migrants holding visas can be vulnerable to exploitation.

Polaris Project reports six U.S. temporary (non immigrant) visas commonly associated with labor exploitation and trafficking as reported to the National Human Trafficking Resource Center (NHTRC) and the Befree Textline they operate. These include the A 3, B 1, G 5, H 2A, H 2B and J I visa.103 The Council on Foreign Relations notes 550,000 visas were issued under the U.S. Temporary Foreign Worker programs in 2021, down from 846,000 in 2019.104

Traffickers take advantage of the dreams and hopes many migrants carry with them, believing in their country of destination they will earn wages and be able to send remittances back to their families. High income countries are almost always the main source of remittances. “For decades, the United States has consistently been the top remittance sending country, with a total outflow of $68 billion in 2020, followed by the United Arab Emirates ($43.2 billion), Saudi Arabia ($34.6 billion), Switzerland ($27.96 billion), and Germany ($22 billion).105

Many domestic workers in the U.S. “often hold special visas tying their immigration status to a single employer.”106 If a situation is abusive and the worker feels compelled to leave, they become undocumented. Dahlstrom adds, “People are brought in and told ‘You can’t work for anyone else’, then there are deportation threats.” She speaks of cases her program in Boston has assisted involving such industries as agriculture, domestic work, carnivals, sports such as soccer, restaurants, and construction.

Classroom, Ecuador. Protect Me Project volunteer teaching the PornoFREE flip book.

34

CHAPTER THREE: IMPACTS

“I may try to represent to you Slavery as it is; another may follow me and try to represent the condition of the Slave; we may all represent it as we think it is; and yet we shall all fail to represent the real condition of the Slave.”108

This explanation was given to the Female Anti Slavery Society of Salem in 1847 by William Wells Brown, a survivor of slavery in the South. Brown could describe in detail the torture of Lewis, a young man who had been strung up to the beams of a warehouse so that his toes only barely touched the floor, after which he had been beaten with a whip. Brown also related an event he saw on a boat when a young mother had her baby stolen from her arms and given away because the baby cried too much. He recounted the rapes of another beautiful young woman he knew and the unfortunate life she led as the mother of the children born of her violation.109 William Wells Brown recognized that although some excruciating details of a slave’s existence may be related to others, still other deeper, hidden aspects of that life are too shocking, too shameful and denigrating to speak.

Respecting this truth, let’s consider some impacts the unspeakable atrocities of modern day slavery may have on victims.

THE EMOTIONAL IMPACT

The overriding feeling when reflecting on the experience of prostitution is simply this: loss. Loss of innocence, loss of time, of opportunity, credibility, respectability, and the spiritually ruinous loss of connectedness to the self.110

Children who have been victims of commercial sexual exploitation show feelings of shame, guilt and low self esteem, and are often stigmatized. “A Canadian study of 229 juvenile male and female prostitutes indicated that 80 percent of the juvenile prostitutes suffered serious depression, 71 percent had a sense of devastated self esteem, and the subjects were three times more likely to have suicidal tendencies than the control group.”111

Often victims feel betrayed, especially if the person who abused them was a person they had trusted; and it is, in the majority of cases. In his book The Wounded Heart, Dan Allender describes the shame of betrayal. “The person who is betrayed often laments: How could I have been so stupid? How could I have trusted someone who was so deceitful? The shame of being taken advantage of increases the fury of self incrimination.”112 Victims of sexual violence often turn to drug and alcohol abuse to numb their emotional pain, and others commit suicide.

35

The victim of commercial sexual exploitation may not self identify as such. On the contrary, he or she may consider their trajectory to have been of their own choice since it may be true that she or he took the initiative to flee their home of origin and head for the street. In some cases, this claim is her or his only remaining vestige of control over their own life.

Let’s read in their own words what survivors teach us about their experience:

“I see prostitution now as an enemy that snuck up on me because I didn’t know enough to anticipate it.” Rachel Moran, survivor of sex trafficking, in her book Paid For.

“It's a cycle: I was looking for a boyfriend who would affirm my self esteem; I sexualized myself to attract boys; it felt good to attract the attention of older guys; I felt bad after agreeing to sexual demands and then being ignored.” Holly Austin Smith, survivor of sex trafficking and author of Walking Prey. Painting by survivor “Sonja Dove”

“When you grow up three blocks from the [prostitution] district, attend an overcrowded and under resourced school, and see violence on a daily basis in your community, it's hard to believe you have other options.” Rachel Lloyd, trafficking survivor, in her book Girls Like Us.

“I was only twelve years old . . . at the time he was like, what, 29, 30; I didn’t really care, I felt like it was cool for me to be twelve years old and for a older dude to be interested in me. . . I was like I’m sexy, like I had it going on . . . He was like I love you, you my baby; and we gonna be together. . . . I thought that was the best thing that ever happened to me.”

From Showtime Documentary Very Young Girls.

“And then there are the mothers who have settled, have stayed with the man, because he’s a man, and you don’t know when one might come along again, so you stay and you ignore it, whatever it is . . . until one day your daughter tells you that he did something, and you just know she’s lying, how could he, why would he, she’s just a child, you’re a woman, he doesn’t need to, that’s disgusting, of course she’s lying, she’s been acting a little fast, a little grown anyway, so you slap her in the face for telling such heinous lies, and when she doesn’t say anything again you know she’s learned her lesson about that kind of bullshit. After all, you didn’t say anything when it was happening to you all those years ago.” Rachel Lloyd, survivor of sex trafficking and author of Girls Like Us.

Added to these details given by survivors of sex trafficking are feelings of shame, heightened by the lies the controllers have told the victim, convincing a victim he or she does not deserve help and they have

36

Painting by Sonja Dove, Survivor| Gift

Painting by Sonja Dove, Survivor| Gift

brought these consequences upon themselves. For the same reason, the intervention of people from outside the circle of abuse may be perceived by the victim as another form of violence.

It is not uncommon for victims who have suffered commercial sexual exploitation to suffer from dissociation disconnecting from past events – and multiple personalities – the healing reaction of the human mind when the trauma experienced exceeds the soul's ability to cope. 113

Often, a victim will suffer from what is called Stockholm Syndrome, developing feelings of affection, loyalty, and dependency towards the abuser. Psychologist Dee Graham points out the key consideration is the victim’s perception. Survivor Rachel Lloyd explains,

It doesn’t matter if those on the outside believe that the victim had an opportunity to escape, that the threat wasn’t really as great as the victim thought it was, or that the kindness shown was trivial and ludicrous in the face of the violence involved. All that matters is that the victim believes these things to be true. Bonding to their captor/abuser is simply a survival mechanism born out of great psychological fear and oppression. 114

One example of a method of trauma bonding is with holding of food for a long period of time until a quota of money is given to the trafficker. Many hours later when the victim returns with the quota, feelings of starvation, anxiety, and emotional upheaval have set in. “As food is presented, the victim experiences a positive mental and physical response—euphoria and gratitude—directed toward the provider of the food. While the trafficker is responsible for withholding food, the more immediate feeling of the trafficker as hero for solving the problem overshadows earlier negative feelings.”115

Combining all the elements mentioned above we see that those who suffer within sexual slavery rarely self identify as victims until much later, looking back. This lack of identifying as a victim complicates the efforts of law enforcement or other entities who might attempt to intervene on their behalf and facilitate an exit from “the life”. Victims can resist aid, not recognizing they are working against themselves.

THE PHYSICAL IMPACT

The presence of sexually transmitted diseases (STDs) can increase the risk of being infected with HIV. STD is any disease that is spread when a virus or bacteria is passed from one person to another during sexual activity. There are several types of STDs, but the most common ones are HPV, gonorrhea, syphilis, herpes, chlamydia, trichomoniasis.116 The absence of medical attention to mitigate symptoms and complications from these diseases further weakens the individual’s hope of health.

38

Victims of commercial sexual exploitation are susceptible to contracting sexually transmitted diseases, including HIV/AIDS. The dangerous “virgin cleansing myth” promotes the notion that having sex with a virgin can cure HIV/AIDS. This has led to an even higher demand for young girls. Many women and girls report consumers pay more for sex without a condom, and people in exploitation are rarely in a position to insist on their use.

Within the physical impact we must mention the risk of unwanted pregnancy, forced abortion and its serious physical and psychological consequences. It is common for the victim of commercial sexual exploitation to suffer from violent attacks: beatings, kicks, being dragged by the hair, burned, cut, and even shot. A nine country study interviewed 854 in commercial sexual exploitation. The findings reveal the level of physical violence endured:

Seventy percent of women in prostitution in San Francisco, California were raped. A study in Portland, Oregon found that prostituted women were raped on average once a week. Eighty five percent of women in Minneapolis, Minnesota had been raped in prostitution. Ninety-four percent of those in street prostitution experienced sexual assault and 75% were raped by one or more johns. In the Netherlands (where prostitution is legal) 60% of prostituted women suffered physical assaults; 70% experienced verbal threats of assault, 40% experienced sexual violence and 40% were forced into prostitution and/or sexual abuse by acquaintances. 117

Survivor Rachel Moran notes the stereotype of the heroin addict who enters street prostitution to feed her habit, admitting this does happen, but explains it is much more common to acquire these addictions, “…usually to alcohol, valium and other prescription sedatives, and to cocaine. These substances are used to numb the simple awfulness of having sexual intercourse with reams of sexually repulsive strangers.” 118

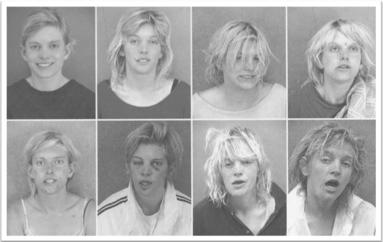

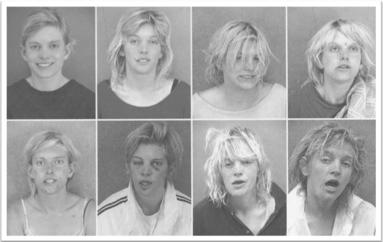

The Salvation Army estimates that once subjected to commercial sexual exploitation, a young woman will survive an average of seven years. These photographs (right) of the same young woman, taken over a four year period at the time of her arrest for prostitution, demonstrate the process of dehumanization that occurs within the confines of abuse. The imminent health risk among prostituted women is premature death. A recent US study of nearly 2,000 prostituted [women] observed

39

over a thirty year period, the leading causes of death were femicide, suicide, drug and alcohol related complications, HIV infection, and accidents in that order.119 The mortality rate among active prostituted [women] was 200 times higher than that of other women with similar demographic profiles.120

THE PSYCHOSOCIAL IMPACT

Commercial sexual exploitation of children is a severe form of human trafficking. Child victims of trafficking suffer adverse effects on their social and educational development. Many never knew a loving nuclear family life and are forced to work at an early age. Without access to support from school or family and being isolated from normal social activities, they are unable to reach their potential. Also, living under constant surveillance and restriction, they have little contact with the outside world and are often unable to seek help. When they are victims of physical and/or emotional violence and abuse, the effects can be long lasting and life threatening.

The Department of Justice in the United States published a timeline in 2010 tracing the progression from sexual abuse as a minor to commercial sexual exploitation. (See below)

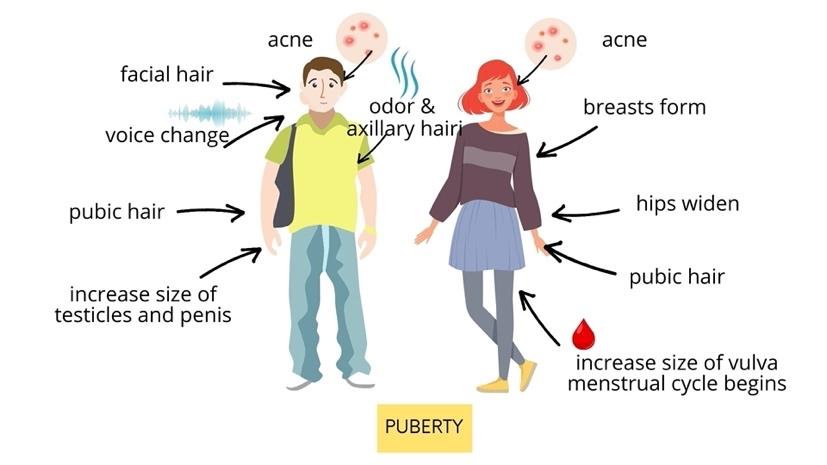

When adult sexuality invades childhood, the child is incapable of processing their feelings in relation to what has happened. In most cases the abuser is someone the child knows and trusts. At that point the child begins to associate love with sex and abuse. This becomes the filter through which they perceive their world and themselves

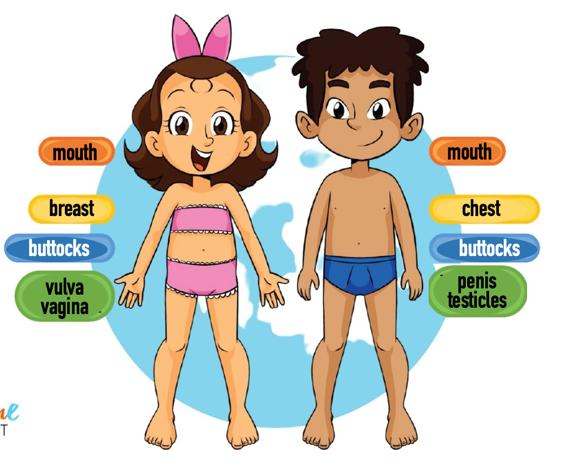

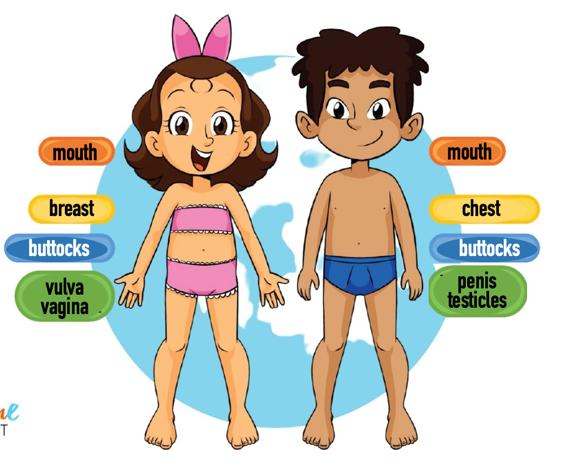

Protect Me Project teaches parents to empower their 2 to 8 year olds by establishing safe boundaries: 1) We have private parts and public parts. 2) No one has a right to touch, tickle, kiss, see or take pictures of our private parts – or ask us to do the same with theirs. 3) Secrets, no. 4) If anyone does something we’re uncomfortable with, we can say “NO” and run to tell a trusted adult.

But what if a child doesn’t know these boundaries? Boundaries are passed over without even knowing it.

40

Guilt and shame grow in the silence of abuse. The child begins to see him or herself as only having value when performing sexually. They may use their sexuality to please, impress or gain acceptance. On the other hand, they may despise their sexuality since they perceive it to be to blame for the advances of their abuser. The same could be said for their physical body. In either case, they believe themselves to have little value. Some expression of that among children might sound like, “I’m not worth defending.” “I’m just trash.” “No one cares what’s happening to me.” “I’m invisible.”

Minor victims of sexual abuse whose personality is that of a risk taker, and perhaps hopeful, may decide at this point to run away from the abusive environment at home. If they chose that path, they would soon find themselves hungry, with nowhere to sleep and no source of income. Surrounded by street savvy adults, the imbalance of power becomes evident. Encouraged by a hyper sexualized pop culture and confronted with a sex market, they will find someone who can “solve all their problems”. This “savior” appears as a friend but is really a trafficker.