The official publication of the Arizona Pharmacy Association brought to you by the Pharmacy Network of Arizona

The official publication of the Arizona Pharmacy Association brought to you by the Pharmacy Network of Arizona

az-aCCp Chapter Stacey Hollen, Chair

CommunIty pharmaCy aCademy Susana Horst, Chair Jaime Von Glahn, Chair-Elect

health-system aCademy Jeannie Hong, Chair Aimee (Keller) Itaaehau, Chair-Elect

managed Care aCademy

James Montague, Chair Patrick Hryshko, Chair-Elect

student pharmaCIst aCademy

Brian Seigfried, Chair, MWU Justin Spicer, Chair-Elect, MWU Candice Eastman, Chair, U of A Kassie Notbohm, Chair-Elect, U of A

teChnICIan aCademy J.R. Gill, Chair Kevin Reger, Chair-Elect

dIstrIC t dIreC tors

Laura Moore, Northeast Lynette Wasson, Northwest Jacob Schwarz, Southwest

Industry representatIve John Fezza

dean of Colleges Mitchell R. Emerson, Midwestern University CPG Rick G. Schnellmann, University of Arizona COP

legal Counsel Roger Morris azpa staff Kelly Fine, Chief Executive Officer Cindy Younger, Accounting Deborah Marcum, PAPA Sarah Elenes, Marketing Taylor Daly, Membership Cindy Esquer, Operations Kathy Harty, Continuing Education

The interactive digital version of the Arizona Journal of Pharmacy is available for members only online at www.azpharmacy.org/ajp (480) 838-3385 web@azpharmacy.org

EDITOR’S NOTE: Any personal opinions expressed in this magazine are not necessarily those held by the Arizona Pharmacy Association. “Arizona Journal of Pharmacy” (ISSN 1949-0941) is published quarterly by the Pharmacy Network of Arizona at: 1845 E. Southern Avenue, Tempe, AZ 85282-5831.

Kelly Fine, R.Ph., FAzPA

managIng edItor Cindy Esquer

edItorIal Board

Lindsay Davis, Pharm.D. Whitney Rice, Pharm.D. Andrea Burns, Pharm.D. Christi Jen, Pharm.D. Nicole Scovis, Pharm.D.

Dear AzPA Members,

Spring Training is upon us with pitchers and catchers reporting on February 14th! This is truly an exciting time with so many questions for the upcoming season…

Will the Astros repeat? Will the Dodgers make another run? Can anyone stop the Yankees’ lineup with Aaron Judge and Giancarlo Stanton? Does any of that matter with the Cubs likely to win it all this year?! And, what has the Association been doing all winter?

It certainly has been an active offseason for many teams as well as our association. We have been hard at work updating the strategic plan, the bylaws, a new website, and preparing for the legislative session.

The strategic plan was approved by the board in December and will go to the various committees to develop plans to accomplish the goals. The bylaws were approved at the last board meeting in January and will go to the membership for final approval very soon. We are excited about some of the changes and the streamlining of the board and election process. We really think the changes make the board more inclusive to all practice settings no matter how unique they may be!

We plan to schedule a couple of virtual town halls in February to provide more information on the changes and answer some questions you all might have, but some of the major changes are in the structure of the board of directors. Here is a quick summary of the changes:

• Board decreases in size from 27 members to 16 members.

• (5) Officers (3 year terms): President, President-Elect, Past President, Treasurer, Secretary

• (8) Directors at Large (2 year terms): (5) open spots, (1) Health System Academy Chair, (1) Community Academy Chair, (1) Technician

(3) Non-voting members: Chief Executive Officer, (2) students representatives

Please tune into the town halls to learn more about the proposed changes and the reason for those changes. If approved by the membership, we will have a smaller crew to inaugurate at the Annual Convention: no more standing shoulder to shoulder, wall to wall.

The website is also very exciting! The entire site has been overhauled. Many of you will notice a brand new interface, which is more appealing, and user friendly. Less noticeable is an entirely revamped back end of the site with an entirely new database to help organize everyone’s membership. These changes are intended to address the number one criticism that came out of all four focus groups at our annual meeting last June, the need for a new, more user friendly website. I encourage you all check it out!

As you can see, the association has been as active as any MLB team this offseason and we are ready to make a run at the World Series ourselves!

Keith Boesen, PharmD, CSPI AzPA President

AzPA serves and represents all pharmacy professionals by fostering safe and effective medication therapy, promoting innovative practice, and empowering its members to serve the health care needs of the public.

Empowering pharmacy professionals to provide optimal patient care.

assoCIates

Lisa Parr

pharmaCIsts

Brittany Manzoline

Sienna Miller

Alicia Sacco

David Allison

Folarin Akinola Kayla Hancock

Kendra Karagozian

Kimberly Crabtree

Kory Muto

Lee Stringer

Linh Le

Loan Trinh

Makini Alleyne-Paramo

Melika Eskalaei

Nicholas Ladziak

Pamela Chukwuleta

Robin Pacheco

Thomas Burrell

resIdents

Christa Tetuan Cindy Lau

Ginger Rinner

Jacqueline Hagarty

Jason Kwan

Mary Obeng

Nada Alkhani

Quincy Ostrem

Samantha Huynh

Taofeek Oyewole

students

Aaron Daza

Abraham Osman

Adam Bailey

Aida Garcia

Ajla Mujezinovic

Alexa Goodman

Alexander Guzman

Alexis Hayes

Alford Garner

Alicia Goldberg

Alvin Mansar

Amanda Urban-Tovar

Amy Nguyen

Andrei Grigorosita

Andrew Hirakawa

Antony Kibet

Arturo Perez

Ashlan Twist

Ashley Wilke

Atefeh sharif

Avninder Sekhon

Bambi Randall

Becky Grey

Bianca Ortiz

Bobbie Le

Briana White

Britt Myslinski

Bryan Espinoza

Cassidy Steiner

Cassidy Tran

Catherine Lee

Cecilia Wild

Charles Page-Bruyere

Christopher Sharp Ciara Mitzel

Claire Applegate

Corey Burnes

Cory Saunders

Courtney Kawasaki

Courtney Scott

Daniel Lampley

Daniel Lopez

Daniel Morrison

Daniel Streng

Danielle Klise

David Nisanov

David Titzler

Dennis Schwerd

Dexter Fang

Dorothy Huynh

Elizabeth Englund

Elizabeth Stalker

Elizabeth Stapleton

Eric Styskal

Fiona Luc

Frances Jeffcoat Gabriella Gambadoro

Gina Horton Gurvir Bains Han Vit Jang

Hana Pajazetovic Hanh Dinh

Hannah Muasher

Hannah Throckmorton Harrison Taylor Heather Smith

Hilary McNicholas

Illyra Vote

Jacey Sims

Jacob Sandoval

Jamie Swenson

Jana Sawyer Jasim El-Ali Jason Lau

Jenna Reynolds

Jennifer Flynn

Jennifer Lee

Jennifer Miszuk

Joe Naff

John Heydorn

Johnson Chuang

Jonathan Chien

Joselyn Villanueva

Joseph Maloy Joshua Kassner

Joss Delaune

Juan Villegas

Jude Enwereji Juliana Vargas Julianne Vice

Justin Spicer

Kaitlyn Vuong

Kate Hoefke

Kathleen Blomquist Kendra O’Connor

Kevin Hong Khadidja Meghoufi

Kimberly Eyraud Kristin Saehr Kristin Shelledy Krystal Tran Kyle Root Lauren Piell Lauren Rosa Lauren Wright Lena Kan Linda Son Lindsay Davis Lisa Le Loi Duong Maria McBride

Marian Assad

Marianito Wauneka

Martha Ashine

McKenzie Stratton

Michael Pham

Michael Weissmueller

Michaela D’Angelo

Monica Ramirez

Monika Yadegar Digaleh

Morgan Messmer

Namitha Joseph Nancy Gerges

Neeshi Shah

Neha Patel

Ngoc Pham Nhi Truong

Nicholas Zieser

Nicklas Waterhouse Nolan Banales

Oanh Truong Olivia Diaz

Omair Khokhar

Paige Pasceri

Paul Sion

Princess Leopardi

Priya Patel

Rik Burnett

Ryan Wonjun Kim

Sandra Savaya

Sara Dehbozorgi

Savannah Templeton

Seth Root

Shannon King Shelby Botello

Shreena Govani

Sigrid Hazel Jimenez

Stacie Noetzelmann

Sujin Kim

Supranee

Soontornprueksa

Tanner Reeves

ThanhThuy Van

Theresa Birch Yeoman

Thomas Goss

Thy Phi

Timothy Fierro

Tina Zomorodian

Tommy Nguyen

Tracy Tran

Tram Nguyen

Trang Pham

Trung Tran

Tuyen Nguyen

Urszula Lawerence

Vanessa Daniel

Vivian Mikhael

Vivian Nguyen

Willibroad Aminazong

Yana Fay Yawa Attitso

Zachary Radford Zaynab Khatoun

teChnICIans

Angela Solarz

Joanna Pino

Leah Jacksn

Lilliana Trujillo

Lourdes Soto Frias

Stephanie Thompson

Viviana Zapata

Yuriddia Rubio De la O

teCnICIans In traInIng

Eda Emer-aydin Sandra Paul

NEW MEMBERS: Visit your Member Center to learn how to get more involved with AzPA. Located on www.azpharmacy.org homepage.

SATURDAY (CONTINUED) | APRIL 28, 2018

11:15AM–12:15PM

BREAKOUT SESSION 2: Let your Voice be Heard: A Discussion of Advocacy and ASHP Delegates

ChristiJen,PharmD,BCPS,FAzPA-BannerBoswellMC,Goodyear,AZ; MindyBurnworth,PharmD,BCPS,FASHP,FAzPA-MWU-G,Glendale,AZ; CarolRollins,PharmD,BCNSP,FASHP,FAzPA-UofA,Tucson,AZ 12:15PM –1:00PM LUNCH 1:30PM – 2:30PM

GENERAL SESSION III: The Role of Biosimilar for Pharmacy: Applications for Biosimilars for Pharmacy and the Pharmacist

AliMcBride,PharmD.,MS,BCPSUofA,CancerCenterTucson,AZ 2:45PM – 3:45PM

BREAKOUT SESSION 3: Clinical Controversies Within Critical Care

LaurenFruhling,PharmD,PGY-2CriticalCarePharmacyResidentatUofA,Tucson,AZ MichelleLaFeverPGY-2CriticalCarePharmacyResidentatUofA,Tucson,AZ

ShannonSullivan,PharmD-PGY-2EmergencyMedicinePharmacyResidentUofA,Tucson,AZ 2:45PM – 3:45PM

BREAKOUT SESSION 4: Pipeline Products: Are Opioids the Answer for Treatment-Refractory Depression?

AlyssaPeckhamPharmD.,BCPPMWU-G,Glendale,AZ 2:45PM – 3:45PM

BREAKOUT SESSION 5: “Is it Me or is There an Interaction Between Us?” | Drug Interactions in Psychiatry

IvanaBogdanich,PharmD,PGY2-ClinicalAssistant,InternalMedicine-UofA,Tucson,AZ

4:00PM – 5:30PM

KimberlyAndrewsLangley,PharmD,MBA,BCPSIHS,Phoenix,AZ

MaryJoZunic,PharmD,MHA,BCACP,BC-ADM,PhCIHS,Phoenix,AZ 4:00PM – 5:00PM

GeorgeNawas,PharmD,PGY-2InternalMedicineResidentUofA,Tucson,AZ 4:00PM – 5:00PM BREAKOUT SESSION

JuanVillanueva,PharmD,BCPS-UofA,BannerMedicalCtr.,Tucson,AZ

MichaelT.Rupp,BSPharm,PhD,FAPhAMWU-G,Glendale,AZ TerriWarholak,BSPharm,PhD,FAPhA,CPHQUofA,Tucson,AZ

RobertJ.Lipsy,PharmD.,BCPS,FASHPUofA,CollegeofPharmacy,Tucson,AZ

Pharmacist Save $25 $300 $250 Technician Save $25 $175 $150 Resident, Retired, Associate Save $25 $175 $150 Student Save $10 $75 $50

Pharmacist Save $25 $225 $175 Technician Save $25 $150 $125 Resident, Retired, Associate Save $25 $150 $125 Student Save $10 $65 $40

Pharmacy Day at the Capitol April 19, 2018 (Phoenix, Az)

Southwestern Clinical Pharmacy Seminar April 27-29, 2018 (Tucson, Az)

AzPA 2018 Annual Convention June 14-17, 2018 (Chandler, Az)

Southwestern

AzPA Immunization Training Program

June 14, 2018 | Chandler, Az

AzPA Psychiatric Training Program

June 14, 2018 | Chandler, Az

APhA’s The Pharmacist & Patient-Centered Diabetes Care Certificate Training Program | Hosted by AzPA

June 14, 2018 | Chandler, Az

AzPA Pain Management Certificate Program

July 28, 2018 (Virtual Program)

See what our tomorrow looks like at: phmic.com/tomorrow2

Imagine being stuck; existing in a place of nightmares; living the life you dreamed of as a child, while suffering in a silent world of depression, guilt, and pain. Married to an incredible spouse, raising four fantastic children, faithfully attending church services, being a respected health professional, active athlete, competent musician, drug addict, and alcoholic. Those final two descriptors were insidious in their onset and became an overwhelming obstacle in my life.

It started with taking an over-the-counter product to aid with sleep. It came to an end during a thirty day stay in a treatment center experiencing withdrawal. The sleep aids progressed through the years to adding prescription controlled substances. At some point, a physician prescribed a narcotic suspension for bronchitis. The cough medication certainly helped with a cough, and worked even better in combination with the sedative/hypnotics. Over a period of a few years the habit increased in scope. I was taking narcotic pain pills and the sleeping medications. Throughout those years, I thought as a pharmacist, I could manage it, and was confident that I could stop anytime. I was sadly mistaken. I tried to stop numerous times. Each failure, and subsequent period of drug abuse, took me down a pathway that I was unable to trace back to where I had started. Every failed attempt to control/stop brought more self-loathing, hopelessness, and despair. A realization occurred; I could not overcome this on my own. One January morning, an internet search located the P.A.P.A. program. I nervously called asking for help. The voice on the other end, while firm, assured with compassion I was not alone and provided directions for me to follow.

The stay in the treatment center rid me of the chemical addictions, introduced me to various recovery support groups, and provided a deeper level of intimacy with my God. I then signed a contract with P.A.P.A., and complied with the requirements set before me in that agreement. By attending numerous meetings, I learned there are hundreds people in those rooms that share parts of my story. They loved me until I could love myself again. A close friend walked me through steps of recovery and gave counsel when I thought I still had all the answers. I spent more daily time in prayer, and more time in the Good Book (Bible). This devotional time provided a source of strength and deepened my relationship with the Lord. I attended weekly meetings with an addiction specialist and other pharmacists in recovery. I also had regular visits with a counselor, to help overcome my damaged thinking, injured personality, and to rebuild a healthy self-esteem. Eventually, I had enough time in my weekly schedule to add playing my guitar and riding my bicycle.

Five years later, I am in awe of the life I am living. I departed an existence surrounded by darkness and depression and now enjoy a life characterized with peace and healing. My life has been completely rearranged. I am a blessing to my beloved family and they have me back. I am playing music again at church and riding my bicycle frequently. Thanks to P.A.P.A, I have added some excellent qualities to my daily practice – I am more humble and a bit wiser; I am more compassionate; and I now know that God and my fellow addicts have provided a way to restore what was once hopelessness. The P.A.P.A. program provided the way out of addiction, a firm guiding hand through the initial years of recovery, and now, at the completion of my contract, a place to see where future dreams take me. I have a profound sense of gratitude for all of those individuals and groups over the last five years that made this possible – a debt that can only be repaid by helping those that find themselves stuck where I was five years ago. Thank you P.A.P.A.!

If you or someone you care about is suffering from an alcohol and/or chemical dependency problem...help is available.

Pharmacists Assisting Pharmacists of Arizona “A Partnership in Caring”

Contact the AzPA Office at 480.207.7869 or papa@azpharmacy.org

All calls confidential. Caller remains anonymous. PAPA is a program of the Arizona Pharmacy Foundation

Committee Purpose Statement: Propose, develop, evaluate, monitor, review, and interpret proposed legislation, rules and regulations affecting the pharmacy profession in the state of Arizona, with special emphasis and activity during the Arizona State Legislative Session.

Join us on the 1st Wednesday of every month by lending your unique voice and experience, so AzPA becomes a more representative association and stronger advocate for your profession.

Governor Ducey called the legislature into a special session on Monday, January 22nd to pass legislation aimed at curbing the opioid epidemic in the state. Mirror bills were introduced in the House and Senate and referred to each chamber’s respective health committees, where stakeholders and members of the public voiced some concerns with the details of the bill, while commending the effort overall. HB 2001/SB 1001 makes changes to prescribing practices and regulation of schedule II controlled substances. Most notably, it prohibits prescribers from dispensing schedule II controlled substances that are opioids, except for opioids that are for medication-assisted treatment for substance use disorders. Prescribers are required to limit initial prescriptions to no more than a 5-day supply and no more than 90 morphine milligram equivalents per day, except in specified circumstances. The bill phases in a requirement that all opioids must be dispensed with an electronic prescription order by July 1, 2019, and the bill requires that pharmacists obtain a patient utilization report from the controlled substance prescription monitoring database before dispensing a schedule II controlled substance at the beginning of each new course of treatment. Beginning in 2019, pain management clinics will be required to meet the same licensure requirements as health care institutions.

The bill also takes steps towards opioid prevention and requires the Department of Health Services to develop strategies targeting youth and at-risk populations in particular. The bill appropriates $10 million from the general fund to establish the Substance Use Disorder Services Fund, and licensed health professionals will be required to take opioidrelated clinical education. Additionally, the bill includes a “good Samaritan” provision stipulating that a person who seeks medical attention for a person experiencing a drugrelated overdose and the person in need of medical attention cannot be charged with the possession of a controlled substance or drug paraphernalia if the evidence for the violation was gained as a result of seeking medical assistance.

While there were many concerns raised on both sides of the aisle regarding the fast pace at which the bills were pushed through the process, several consensus amendments we adopted on the floor and the bills passed both chambers unanimously on Thursday, January 25th. The first special session of the 53rd legislature adjourned sine die at 7:10 pm Thursday night, and the governor signed the bill in law Friday, January 26, 2018.

AzPA Action: AzPA signed in supportive of the governor’s opioid package, but joined other pharmacy stakeholders in expressing concerns with several parts of the bill. The requirement for schedule II opioids to be dispensed in containers with red caps

was not amended and remains in the signed bill. However, the floor amendment did clarify language concerning “refills or extensions” of the drugs, reduced the mandatory pharmacist check of the CSPMP to only CII medications, and added pharmacists in to the provision that checking an electronic medical record system that is integrated with the PMP satisfies the check requirement.

HB 2040: pharmacy board; definitions; reporting

• Sponsor: Representative Carter

• Summary: Various changes relating to the Board of Pharmacy. The definition of “pharmacy” is expanded to include a “satellite pharmacy” (defined). If a medical practitioner, pharmacy or health care facility dispenses a controlled substance listed in specified statutes, the person or entity is required to submit the required informational report to the Board once each day.

• Status: 1/18 House Health do pass · Position: Neutral with AzPA amendment ·

• Actions: AzPA proposed amendment to address concern about revocation to allow individuals additional rights if their license is revoked.

HB 2041: pharmacy board; licenses; permits

• Sponsor: Representative Carter

• Summary: Eliminates the graduate intern license that the Board of Pharmacy was previously authorized to issue to a graduate of a Board-approved college, school or program of pharmacy.

• Status: 1/22 House Rules OK

• Position: Neutral

HB 2107: prescription drug costs; patient notification

• Sponsor: Representative Syms

• Summary: A pharmacy benefits manager or other entity that administers prescription drug benefits is Arizona cannot prohibit by contract a pharmacy or pharmacist from informing the patient that the patient may be able to procure a prescription medication at a lower cost, including paying the cash price.

• Status: 1/22 referred to House Health

• Position: Support

• Actions: Invited Representative Syms to our stakeholder meeting on 2202 which addresses the same provision

HB 2107: prescription drug costs; patient notification

• Sponsor: Representative Syms

• Summary: A pharmacy benefits manager or other entity that administers prescription drug benefits is Arizona cannot prohibit by contract a pharmacy or pharmacist from informing the patient that the patient may be able to procure a prescription medication at a lower cost, including paying the cash price.

• Status: 1/22 referred to House Health

• Position: Support

• Actions: Invited Representative Syms to our stakeholder meeting on 2202 which addresses the same provision

HB 2149: pharmacies; remote dispensing

• Sponsor: Representative Weninger

• Summary: For the purpose of pharmacy licensure and regulations, the definition of “pharmacy” is expanded to include a “remote dispensing site pharmacy” (defined) where a pharmacy technician or pharmacy intern prepares, compounds or dispenses prescription medications under “remote supervision by a pharmacist” (defined as a pharmacist directing and controlling their actions through the use of audio and visual technology). A remote dispensing site pharmacy is required to obtain and maintain a pharmacy license issued by the Board of Pharmacy.

• Additional licensing requirements for remote dispensing site pharmacies are established, including requirements for continuous video surveillance, and recordkeeping and inventory requirements. Establishes minimum experience and professional education requirements a pharmacy technician must have before preparing, compounding or dispensing prescription medications at a remote dispensing site pharmacy.

• Status: 1/18 House Health do pass

• Position: Support with AzPA amendment

• Actions: AzPA has worked on negotiations with Cardinal Health regarding the telepharmacy bill through various webinars and stakeholder meetings. We are happy to report that were able to reach a compromise on provisions of the bill to ensure this is a safe option for our patients and a viable option for community pharmacies who want to expand their business. The bill has passed House Health on January 16th and awaits Rules Committee.

• Amendment will include: mandating CPhT for remote dispensing technician; eliminating compounding; reduce number of sites to 1 or 2 depending on whether the pharmacist is supervising another physical location; and increase surveillance records from 30 to 60 days.

2202:

• Sponsor: Representative Cobb

• Summary: Pharmacy benefits managers are prohibited from charging or collecting from an “enrollee” (defined) a cost sharing requirement for a prescription or pharmacy service that exceeds the amount retained by the pharmacist or pharmacy from all payment sources for filling the prescription or providing the service. Pharmacy benefits managers cannot prohibit a pharmacist or pharmacy from informing an enrollee of the difference between the enrollee’s cost sharing requirement and the amount the enrollee would pay without using prescription drug coverage, or from selling a prescription drug to an enrollee who chooses not to use prescription drug coverage. Pharmacy benefits managers are prohibited from restricting a pharmacy from dispensing a 90-day fill of a prescription medication pursuant to State Board of Pharmacy rules. If the Department of Insurance believes a pharmacy benefits manager has violated these prohibitions, the Director is authorized to issue a cease and desist order, assess a civil penalty, and refer the matter to the Attorney General for enforcement. A person aggrieved by a violation may institute a civil action in superior court.

• Status: 1/24 referred to House Health

• Position: Support

• Actions: AzPA’s bill concerning PBMs was first read and assigned to the House Health

Committee on January 24th.

• Representative Cobb is convened another stakeholder meeting on the bill on Monday, January 29th where a proposed strike everything amendment was discussed. The bill looks to prohibit co-pay clawbacks, gag clauses, restrictions on delivery service and restrictions on 90 day fills.

• Sponsor: Representative Carter

• Summary: Health insurers are required to establish a process for the electronic submission of a credentialing or re-credentialing application and supporting documentation. A credentialing committee of at least two persons is required to review credentialing applications. Establishes deadlines for a health insurer to acknowledge receipt of an application, provide notification of an incomplete application, and conclude the credentialing process. A health insurer is prohibited from denying a claim for a covered service provided to a subscriber by a participating provider who has been approved to contract with a network plan if the covered services are provided after the effective date of the contract. Health insurers that comply in good faith with these requirements are immune from civil liability for the purposes of reviewing and approving a credentialing application. Effective January 1, 2019.

• Status: 1/24 referred to House Health

• Position: Support

Who’s representIng you?Kelly L. Fine, R.Ph., FAzPA AzPA Chief Executive Officer (left) Jessie Armendt Compass Rose Public Affairs AzPA Contract Lobbyist (right) Ken Bykowski, BS Pharm, MSHSA (left) Mark Boesen, JD, Pharm.D., FAzPA (right) AzPA Legislative Committee Co-Chairs

The authors have no conflicts to disclose.

Purpose:

To provide a brief review of the most recent literature evaluating corticosteroid plus antiviral therapy versus corticosteroid therapy alone in improving treatment outcomes in Bell’s palsy patients.

Summary:

Bell’s palsy is a condition characterized by the abrupt onset of unilateral facial weakness and paralysis of unknown etiology. Corticosteroids remain the predominant pharmacologic therapy in the treatment of Bell’s palsy due to their ability to reduce swelling and inflammation. According to the American Academy of Neurology’s 2012 clinical practice guideline update, the role of antivirals as adjunctive agents in the treatment of Bell’s palsy remains ambiguous as studies have failed to provide sufficient evidence of their benefit. Recently published literature suggest that there may exist a modest benefit in patients with severe facial palsy. However, the overall benefit of antiviral therapy in the management of Bell’s palsy remains unclear.

Conclusion:

To date, the culmination of existing evidence fails to demonstration substantial benefit with adjunctive antiviral therapy in the treatment of Bell’s palsy.

Keywords: antivirals; corticosteroids; facial paralysis; Bell’s palsy

Introduction:

Bell’s palsy is a mononeurapathy which is defined as disorder affecting a single nerve or nerve group. It is characterized by acute, unilateral facial weakness and paralysis. 1-5 The cause of Bell’s palsy has not been definitively identified. What is known is that compression of the facial nerves as a result of swelling combined with inflammatory processes leads to the observed paralysis.1-4 Reactivation of the herpes simplex virus (HSV-1) is theorized as a possible etiology of Bell’s palsy.4 This theory is based on serological studies identifying positive HSV-1 IgG levels in 20-79% of patients.4

Corticosteroids represent the cornerstone medication therapy in the treatment of Bell’s palsy as an extensive body of evidence exists supporting their efficacy.1-4 Treatment with corticosteroids has demonstrated shortened recovery times. In addition, early steroid therapy has shown to improve the chance for complete recovery.2, 3 Trials evaluating antiviral monotherapy (e.g. acyclovir, valacyclovir or famciclovir), on the other hand, have failed to provide sufficient evidence of benefit. 1-4 Combination therapy with corticosteroids plus antivirals remains controversial as the available literature either reports a modest benefit of no statistical significance or no additional benefit of such regimens when compared to corticosteroid therapy alone. 5-7

In their 2012 clinical practice guideline update, The American Academy of Neurology (AAN) states that all patients with new-onset Bell’s palsy should be offered corticosteroid therapy to increase the probability of facial functional recovery.5 Similar stances and recommendations with respect to corticosteroid monotherapy are made in the clinical practice guidelines published by the American Academy of Otolaryngology – Head and Neck Surgery Foundation (AAOHNSF) and the Canadian Medical Association Journal (CMAJ).6,7 In general, across the three guidelines, antiviral monotherapy is not recommended. However, the guidelines do differ in their recommendations for adjunctive antiviral therapy. Despite the lack of established benefit, both the AAN and AAO-HNSF guidelines state that combination antiviral therapy may be offered to all new-onset Bell’s palsy patients; although the AAO-HNSF guidelines specify that this offer should be made within 72 hours of symptom onset.5,6 Alternatively, adjunctive antiviral therapy should only be considered in those patients with severe disease, including complete paralysis, according to the CMAJ guideline.7 Following the AAN guideline recommendation, any patient offered antiviral therapy in addition to corticosteroid therapy should be counseled on the lack of established benefit with such therapy.5

The purpose of this paper is to provide a brief review of the most recent literature evaluating corticosteroid plus antiviral therapy to corticosteroid therapy alone in improving treatment outcomes in Bell’s palsy patients since publication of the AAN guideline update.

Bell’s palsy randomized controlled trials published since the AAN guideline update:

In a prospective study conducted by Lee and colleagues, a total of 237 subjects with severe (defined by a House-Brackman (HB) score ≥ 5) Bell’s palsy were randomized to receive treatment with methylprednisolone tapered over 10 days as monotherapy or in combination with oral famciclovir 750 mg daily for 7 days.8 Following randomization, 134 subjects were assigned to be treated with methylprednisolone alone while 113 subjects were assigned to receive combination antiviral therapy. However, the study data for only 107 and 99 subjects, respectively, were analyzed. The study outcome was defined as

complete recovery at the end of 6 months, defined as a House-Brackman grade of I and II. Complete recovery was achieved in 82.8% of patients within the combination treatment group and 66.4% in the methylprednisolone alone arm (p=0.010). Additional analysis revealed that subjects in the combination therapy group were 2.6 times more likely to achieve complete recovery than those receiving just methylprednisolone (OR = 2.2). Based on these results the authors concluded that combination methylprednisolone and famciclovir therapy improved the chances of complete recovery in patients with severe Bell’s palsy.8

A double-blind, randomized controlled trial examining corticosteroid and/or antiviral therapy versus placebo in Bell’s palsy patients with varying degrees of disease severity demonstrated that the addition of valacyclovir to prednisolone did not improve complete recovery of facial function at 12 months.9 In this prospective study, patients were randomly assigned to receive one of the following treatments: placebo plus placebo, prednisolone plus placebo, valacyclovir plus placebo, or prednisolone plus valacyclovir. Patients who received prednisolone were treated with a dose of 60 mg daily tapered over the course of ten days. Patients who received valacyclovir were administered 500 mg twice daily for seven days. Following randomization into a treatment group, the degree of facial palsy was assessed utilizing the Sunnybrook scoring system with a score of 0 representing complete paralysis and a score of 100 representing normal facial function. Patients were either stratified into a severe, moderate, or mild severity group based on their Sunnybrook score. The primary outcome of complete recovery was defined as a Sunnybrook score equal to 100 at 12 months. In those patients with severe facial palsy (Sunnybrook score at baseline ≤ 20), there was no difference in the achievement of complete recovery at 12 months between those patients treated with prednisone alone (50%, 19/38 patients) versus those patients treated with prednisone plus valacyclovir (51%, 20/39 patients) (p=1). Complete recovery of facial function at 12 months for patients with a moderate severity score (Sunnybrook score at baseline 21-40) was achieved in 65% (46/71 patients) of those patients who received prednisone alone compared to 72% (53/74 patients) of patients who received prednisone and valacyclovir (p=0.48). For those patients who had mild facial paralysis (Sunnybrook score at baseline >40), 82% (82/100 patients) of patients who received prednisone alone achieved complete recovery at 12 months compared to 85% (79/93 patients) of patients who were treated with prednisone plus valacyclovir (p=0.70). The results of this study suggest that the addition of valacyclovir has no statistically significant impact on the rate of recovery from facial paralysis based on disease severity.9

Bell’s palsy systematic reviews & meta-analyses published since AAN guideline update:

A Cochrane report published in 2015 assessed the study data of 10 trials evaluating the effectiveness of antiviral therapy in addition to, or instead of, prednisolone alone in the treatment of Bell’s palsy.10 Of the ten studies included in the review, eight studies (n = 1,315 subjects) specifically examined the rate of

incomplete recovery of facial function following treatment with corticosteroid and antiviral therapy or corticosteroid therapy alone. These studies used a number of validated scoring systems used in the assessment of facial paralysis. Analysis of the pooled data revealed that the addition of an antiviral agent to corticosteroid therapy significantly reduced incomplete recovery rates with a risk ratio (RR) of 0.61 (95% CI: 0.39-0.97). However, this systematic review included the aforementioned randomized controlled trial conducted by Lee et al. which examined combination antiviral therapy in severe Bell’s palsy patients. The inclusion of this study may have skewed the results of the analysis considering that none of the other included studies selected patients based on disease severity. A comparison of antiviral to corticosteroid monotherapies yielded results similar to previous studies where antiviral therapy alone was found to be inferior to corticosteroid monotherapy (RR = 2.82; 95% CI: 1.09 – 7.32).10

A second systematic review with meta-analysis compared the impact of antiviral monotherapy to that of antiviral therapy plus corticosteroid or placebo on complete recovery rates of patients with varying degrees of facial palsy at baseline.11 A total of ten randomized controlled trials (n= 2,419 patients) met the study’s inclusion criteria. The primary outcome of complete recovery was defined as a grade I on the HB facial paralysis assessment scale. In two of the selected trials, subjects were randomized to receive antiviral therapy plus corticosteroid or placebo therapies. All subjects in the remaining eight studies received concomitant corticosteroid therapy. However, only six studies provided a sufficient amount of data to adequately assess complete recovery rates within the selected study population. A random effects analysis of the composite study data showed no statistically significant difference in the attainment of complete recovery in patients who received an antiviral agent versus those who did not (RR = 1.06; 95% CI: 0.97 – 1.16; P = 0.19).11 In addition, a subgroup analysis on the composite study data from seven trials demonstrated that the response to antiviral therapy did not significantly differ according to symptom severity (P = 0.11).11

To date, the combined body of literature has not conclusively substantiated the effectiveness of antiviral therapy in addition to corticosteroid therapy. Currently published literature provides weak evidence of benefit with adjunctive antiviral therapy. Considering the conflicting nature of the evidence reviewed, the benefit of antiviral addition is still unclear. Pending publication of additional literature, antiviral therapy may be considered in patients with severe disease.

1. Zandian A, Osiro S, Hudson R, et al. The neurologist’s dilemma: a comprehensive clinical review of Bell’s palsy, with emphasis on current management trends. Med Sci Monit. 2014; 20: 83-90.

2. Davenport R, McKinstry B, Morrison J, et al. Bell’s palsy: new evidence provides a definitive drug therapy strategy. Br J Gen Pract. 2009; 59: 569-570.

3. De Almeida JR, Al Khabori M, Guyatt GH, et al. Combined corticosteroid and antiviral treatment for Bell palsy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Jama. 2009; 302: 985-993.

4. Numthavaj P, Thakkinstian A, Dejthevaporn C, et al. Corticosteroid and antiviral therapy for Bell’s palsy: a network meta-analysis. BMC Neurol. 2011; 11:1.

5. Gronseth GS, Paduga R. American Academy of Neurology. Evidence-based guideline update: steroids and antivirals for Bell palsy: report of the Guideline Development Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurol. 2012; 79: 2209-13.

6. Baugh RF, Basura GJ, Ishii LE, et al. Clinical practice guideline: Bell’s palsy. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2013; 149: S1-27.

7. De Almeida JR, Guyatt GH, Sud S, et al. Management of Bell palsy: clinical practice guideline. Can Med Assoc J. 2014; 186: 917-22.

8. Lee H, Byun J, Park M, Yeo S. Steroid-antiviral treatment improves the recovery rate in patients with severe Bell’s palsy. Am J Med. 2013; 126: 336-41.

9. Axelsson S, Berg T, Jonsson L, et al. Bell’s palsy–the effect of prednisolone and/or valaciclovir versus placebo in relation to baseline severity in a randomized controlled trial. Clin Otolaryngol. 2012; 37: 283-90.

10. Gagyor I, Madhok VB, Daly F, Somasundara D, Sullivan M, Gammie F, Sullivan F. Antiviral treatment for Bell’s palsy (idiopathic facial paralysis). Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015; 11

11. Turgeon RD, Wilby KJ, Ensom MH. Antiviral treatment of Bell’s palsy based on baseline severity: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Med.2015; 128: 617-28.

American Academy of Neurology (AAN) 2012 Update5

American Academy of OtolaryngologyHead and Neck Surgery Foundation (AAO-HNSF) 20136

Should be offered in all patients with new-onset Bell’s palsy

Oral steroids should be prescribed within 72 hours of symptom onset for Bell’s palsy patients ≥ 16 years

Canadian Medical Association Journal (CMAJ) 20147

Corticosteroid therapy is recommended in all Bell’s palsy patients

No recommendation made

Might be considered in patients with new onset Bell’s palsy

Antiviral therapy should not be prescribed alone in new-onset Bell’s palsy

Antiviral therapy in addition to oral steroids may be offered within 72 hours of symptom onset.

Antiviral treatment alone is not recommended

The combined use of antivirals and corticosteroids is recommended in patients with severe to complete paralysis.

I Normal Normal facial function in all areas

II Mild dysfunction

Slight weakness noticeable on close inspection; may have very slight synkinesis

III Mild dysfunction

IV Moderately severe dysfunction

V Severe dysfunction

Obvious, but not disfiguring, difference between 2 sides; noticeable, but not severe, synkinesis, contracture, or hemifacial spasm; complete eye closure with effort

Obvious weakness or disfiguring asymmetry; normal symmetry and tone at rest; incomplete eye closure

Only barely perceptible motion; asymmetry at rest

VI Total paralysis No movement

**Adapted from Coulson SE, Croxson GR, Adams RD, O’Dwyer NJ. Reliability of the “Sydney,”“Sunnybrook,” and “House Brackmann” facial grading systems to assess voluntary movement and synkinesis after facial nerve paralysis. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2005; 132:543-9

Figure 1: Sunnybrook Facial Grading System

Resting Symmetry (compared to normal slide)

Symmetry of Voluntary Movement (degree of muscle excursion compared to normal side)

Synkinesis (rate the degree of involvement muscle contraction associated with each expression)

Eye (Choose one only)

Mouth Normal 0 Corner Dropped 1 Corner Pulled Up/ Out 1 Total: Resting Symmetry Score x5:

Total:

Standard Expressions None Mild Moderate Severe Normal 0 Forhead wrinkle 4 1 2 3 5 0 1 2 3 Narrow 1 Gentle eye closure (OCS) 4 1 2 3 5 0 1 2 3 Wide 1 Open mouth smile 4 1 2 3 5 0 1 2 3 Eyelid Surgery 1 Snarl 4 1 2 3 5 0 1 2 3 Lip Pucker 4 1 2 3 5 0 1 2 3 Check also (naso-lablal fild) Normal 0 Absent 1 Less Pronounced 1 More Pronounced 1

Synkinesis Score Total: Voluntary movement score x4 Vol mov’t score - Resting Symmetry score - Synkinesis score Composite score

=

JenniferLee,Pharm.D.Candidate;UofA,Tucson,AZ

AmandaKlein,Pharm.D.,CDE;ElRioCommunityCenter,Tucson,Az

DustinHollowway,MPH;ElRioCommunityCenter,Tucson,Az

The authors have no conflicts to disclose.

Purpose:

To evaluate prescribed dosages of amoxicillin in the treatment of pediatric acute otitis media (AOM) at a community health center, as part of a quality improvement project.

Methods:

Based on the health center’s pharmacy data during a 4.5-month period, pediatric patients who received amoxicillin for AOM were identified. Their records were reviewed retrospectively, and the total daily dose and mg/kg/day values were calculated. Weight-based categories of < 20 kg and > 20 kg were used for analysis based on previously published studies.

Results:

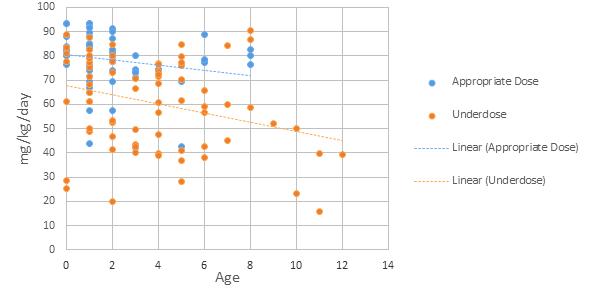

Of the 207 patients whose records were reviewed, 133 (64%) had been prescribed amoxicillin or amoxicillin/clavulanate for AOM, and 60 (45%) of these prescriptions were considered to have provided appropriate dosages of amoxicillin. Under-dosing was common (55%), and occurred in 48% of the cases in the < 20 kg group and in 77% of the cases in the > 20 kg group. Ten (8%) dosages fell below the regular dosage of 40 mg/kg/day, and 8 of these 10 occurred in the > 20 kg group. The mean (SD) dosage of amoxicillin was 69 (18) mg/kg/day, with a range of 16 to 94 mg/kg/day.

Conclusion:

A wide range of amoxicillin dosages was observed (16 to 94 mg/kg/day), and approximately half of the prescriptions were considered to be appropriate per guidelines. With 55% and 8% of the prescriptions considered under-dosed and falling under 40 mg/kg/day, respectively, the health center may benefit from pharmacist interventions to verify the indications and encourage optimal dosing. Large outcomes studies on regular vs. high-dose amoxicillin in pediatric AOM are lacking, however, and further research is warranted.

The 2013 AOM Clinical Practice Guidelines published by the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) and American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP) provide the following recommendations:1

• Observation (for 48 to 72 hours, with close follow-up) may be an option in:

• Children 6 months to 23 months of age with non-severe unilateral AOM

• Children 2 years or older with non-severe unilateral/bilateral AOM

• High-dose amoxicillin (80 to 90 mg/kg/day divided into two doses) is the first-line antibiotic choice in patients who are not allergic to penicillin

• Children who have taken amoxicillin in the past 30 days, who have concurrent purulent conjunctivitis, or who need coverage for β-lactamase-positive organisms should be treated with high-dose amoxicillin/clavulanate (90 mg/ kg/day of the amoxicillin component)

• Children with persistent symptoms despite 48 to 72 hours of antibiotic therapy should be re-examined, and a second-line agent, such as amoxicillin/ clavulanate, should be used if appropriate

High-dose amoxicillin (80 to 90 mg/kg/day divided into two doses) has been shown to yield middle ear fluid levels that exceed the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) of all Streptococcus pneumoniae strains that have intermediate resistance to penicillin, and many of highly resistant strains (penicillin MICs, > 2 µg/mL) for a longer period of the dosing interval (time over MIC), and has been shown to improve bacteriologic efficacy compared with the regular dose (40 mg/kg/day).1-4

However, with rising childhood obesity – as indicated by the increasing linear trend published in the 2017 National Center for Health Statistics data, the recommended 80-90 mg/kg/day dosage may exceed the standard adult dosage of 1500 mg/day.4-5 There are limited data regarding a maximum recommended dosage or how to appropriately dose amoxicillin in such cases; the manufacturer of brand-name amoxicillin and brand-name amoxicillin/clavulanate recommends following adult dosing, while other experts have suggested a maximum of 4,000 mg/day for high-dose therapy.6-7 A prospective study of 51 pediatric patients at a poison control center suggested that over-dosages of < 250 mg/kg of amoxicillin are not associated with significant clinical symptoms and do not require gastric emptying.8,9 When 14 members of the AAP’s Subcommittee on Management of AOM were surveyed, 66.7% stated that they would prescribe the standard adult dosage (1500 mg/day), whereas 33.3% stated that they would prescribe the recommended 80-90 mg/kg/day.4

Based on the health center’s pharmacy data during a 4.5-month period, pediatric patients who received amoxicillin were identified. Their records were reviewed and collected data included age, weight (kg), medication (amoxicillin or amoxicillin/ clavulanate oral suspension), prescription directions, and indication. The total daily dose and mg/kg/day values, based on total body weight, were calculated. A dosage was considered to be appropriate per guidelines if the amoxicillin component was within +5% of the recommended dosage (80 to 90 mg/kg/ day for amoxicillin, 90 mg/kg/day for the amoxicillin component in amoxicillin/ clavulanate). For children with a weight above 20 kg, a total daily dose of 1500 to 4000 mg amoxicillin was also considered to be acceptable as long as it did not exceed 90 mg/kg/day +5%. Weight-based categories of < 20 kg and > 20 kg – a weight that results in a dosage of > 1500 mg/day – were used for analysis based on previous studies found in the literature.

A total of 207 patient records were reviewed. Of the 207 patients, 133 (64%) had been prescribed amoxicillin or amoxicillin/clavulanate for AOM. Other top indications included pharyngitis (16%), prophylaxis for dental procedures (8%), and rhinosinusitis (4%).

In the AOM group of 133 children, the mean (SD) age was 3 (2.7) years with a range of 5 months to 12 years, and the mean (SD) weight was 17.5 (10.9) kg with a range of 4.5 to 69 kg. The mean (SD) dosage of amoxicillin was 69 (18) mg/kg/day, with a range of 16 to 94 mg/kg/day.

Of the 133 prescriptions, 17 (13%) were for amoxicillin/clavulanate, and 60 (45%) were considered to have provided appropriate dosages of amoxicillin. Underdosing was common (55%), and 10 (8%) dosages fell below 40 mg/kg/day – 8 of these 10 occurred in the > 20 kg group. No prescriptions exceeded the upper limit of 94.5 mg/kg/day. If a more lenient, +10% range were to be chosen, the number of prescriptions with appropriate dosages would increase modestly to 72 (54%).

The results for the weight-based groups are summarized in Table 1 and Graph 1.

Table 1. Results of the < 20 kg and > 20 kg pediatric groups with amoxicillin or amoxicillin/clavulanate prescriptions (n=133)

Age, mean (SD), yr 2 (1.5) 6.8 (2.3)

Weight, mean (SD), kg 13 (3.6) 33 (12.6)

Daily dose, mean (SD), mg/day 912 (269) 1640 (540)

Daily dose, median (range), mg/day 880 (250–1500) 1600 (750–3600)

Weight-based dosage, mean (SD), mg/kg/day 73 (15.2) 54 (20.5)

Weight-based dosage, median (range), mg/kg/ day 77 (19.9–93.5) 53 (15.7–90.6)

Appropriate dosage, n (%) 53 (52) 7 (23)

Under-dosage, n (%) 49 (48) 24 (77) Over-dosage, n (%) 0 (0) 0 (0)

Dosages below 40 mg/kg/ day, n (%) 2 (2) 8 (26) *

Once-daily dosing, n (%) 0 (0) 0 (0) * 5 of the 8 dosages were also < 1500 mg/day

The findings of this internal review are consistent with those of a previous study by Christian-Kopp, et al. The retrospective study of 359 pediatric patients found that those in the higher weight category (> 20 kg) were prescribed a significantly lower-than-recommended amoxicillin dosage (40.4 vs. 74.2 mg/kg/day in the < 20 kg group, P < 0.001).4 The support for high-dose amoxicillin in AOM is primarily based on pharmacokinetic and bacteriological studies, which have suggested

its advantage in providing coverage for penicillin-resistant S. pneumoniae. A retrospective study by Chu, et al. showed that, in a pediatric cohort, high-dose amoxicillin/clavulanate led to improved outcomes only in children < 20 kg with bilateral AOM illnesses.10 Prospective studies are needed to provide higher level evidence, as a lack of consensus is seen in practice. The guidelines do not address maximum doses or how to approach cases in the higher weight category, leaving this up to the clinician’s professional judgment and thus resulting in large variations. A major limitation of this review was the absence of data regarding the clinical outcomes of the patients, and thus unknown implications of under-dosing amoxicillin. As with all retrospective data collection, it was dependent on accurate documentation in the electronic medical record.

A wide range of amoxicillin dosages was observed (16 to 94 mg/kg/day), and approximately half of the prescriptions were considered to be appropriate per the AOM Clinical Practice Guidelines. The clinical significance and impact of this is unclear, however; large outcomes studies on regular vs. high-dose amoxicillin in AOM are lacking, and further research is warranted. With 55% and 8% of the prescriptions considered under-dosed and falling under 40 mg/kg/day, respectively, the health center may benefit from pharmacist interventions to verify the indications and encourage optimal dosing. Priority may be placed on patients who present with risk factors for penicillin-resistant S. pneumoniae – such as < 2 years of age, day care attendance, antibiotic use in the previous month, and recent hospitalization – as well as ensuring that dosages are > 40 mg/kg/day (unless adult dosages are reached) with twice daily administration.1,11

Disclosures: None.

1. Lieberthal AS, Carroll AE, Chonmaitree T, et al. The diagnosis and management of acute otitis media. Pediatrics. 2013;131(3):e964-e999.

2. Embree J. High dose amoxicillin: Rationale for use in otitis media treatment failures. Paediatr Child Health. 1999;4(5):321-323.

3. Piglansky L, Leibovitz E, Raiz S, et al. Bacteriologic and clinical efficacy of high dose amoxicillin for therapy of acute otitis media in children. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2003;22(5):405–413.

4. Christian-Kopp S, Sinha M, Rosenberg DI, et al. Antibiotic Dosing for Acute Otitis Media in Children: A Weighty Issue. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2010;26(1):19-25.

5. Hales CM, Carroll MD, Fryar CD, et al. Prevalence of Obesity Among Adults and Youth: United States, 20152016. NCHS data brief, no. 288. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics. 2017.

6. FDA Prescribing Information: AMOXIL® (amoxicillin) capsules, tablets, or powder for oral suspension. Dr. Reddy’s Laboratories, Inc. (per FDA), Bristol, TN, 2015.

7. Bradley JS, Nelson JD, Kimberlin DK, et al. Nelson’s Pocket Book of Pediatric Antimicrobial Therapy. 21st ed. American Academy of Pediatrics. 2015.

8. Swanson-Biearman B, Dean BS, Lopez G, et al. The effects of penicillin and cephalosporin ingestions in children less than six years of age. Vet Hum Toxicol. 1988;30(1):66-67.

9. FDA Prescribing Information: AUGMENTIN® (amoxicillin/clavulanate potassium) tablets. GlaxoSmithKline (per FDA), Research Triangle Park, NC, 2006.

10. Chu CH, Wang MC, Lin LY, et al. High-dose amoxicillin with clavulanate for the treatment of acute otitis media in children. Scientific World J. 2014; Article ID 965096. doi:10.1155/2014/965096

11. Ipp M. New evolving strategies for the management of acute otitis media. Pediatric Child Health. 1999;4(7):451-452.

1993

• Median salary for pharmacist aged 25-34 was $48,980 for men and $47,507 for women

• The World Wide Web was born at CERN. 1968

• Health Manpower Act of 1968 provided institutional grants in support of pharmacy education.

• First full time (24/7) drug information center established as part of the ninth floor pharmacy project at the University of California San Francisco. 1943

• President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed the Durham-Reynolds bill as Public Law 130, establishing the U.S. Army Pharmacy Corps. 1918

• University of Idaho, Southern Branch (Pocatello) formed College of Pharmacy (later renamed Idaho State College). 1893

• University of Texas (Austin) College of Pharmacy formed

• State University of Oklahoma College of Pharmacy formed.

By:

Dennis B. Worthen, PhD, Cincinnati, OH

OneofaseriescontributedbytheAmericanInstituteoftheHistoryofPharmacy,auniquenon-profit societydedicatedtoassuringthatthecontributionsofyourprofessionendureasapartofAmerica’shistory. Membershipoffersthesatisfactionofhelpingcontinuethisworkonbehalfofpharmacy,andbringsfiveor morehistoricalpublicationstoyourdooreachyear. Tolearnmore,checkout: www.aihp.org

ACPE UAN: 0129-0000-17-009-H01-P

Author

: Amanda R. Kriesen, R.Ph., PharmDThe author has no relevant financial relationships to disclose.

Goal: The goal of this lesson is to provide background information on insomnia, and a summary of recommendations for the nonpharmacologic and pharmacologic treatment based on current guidelines.

At the completion of the CPE activity, participants should be able to:

1. demonstrate an understanding of the scope of insomnia and its effects on both the economy and the healthcare system;

2. recognize common risk factors and clinical presentation associated with insomnia;

3. list non-pharmacologic strategies for treating insomnia; and

4. demonstrate an understanding of pharmacologic agents used in the treatment of insomnia.

Background:

Quality of sleep has become increasingly recognized as an important public health topic.

Excessive daytime sleepiness may lead to diminished work performance

and increased absenteeism from the workplace. Insufficient sleep has also been associated with an increase in motor vehicle accidents, industrial hazards, and occupational errors. Patients who lack sufficient sleep have an increased mortality and reduced quality of life. Several studies have demonstrated an increased risk of psychiatric disorders among individuals with prior insomnia.

Sleep insufficiency takes a toll on the economy with respect to loss of workplace productivity, costing an estimated $63.2 billion in the United States alone. Insufficient sleep may be caused by a broad scale of societal factors, including round-the-clock access to technology and demanding work schedules. However, sleep disorders also play an important role.

Insomnia affects 10 to 30 percent of the U.S. adult population, although as many as 35 to 50 percent of adults report having symptoms associated with the disorder. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), an estimated 50 to

70 million U.S. adults have sleep or wakefulness disorder. Insomnia places a large burden on the healthcare system, accounting for a total approximate cost of $30 to $107 billion spent annually.

Insomnia is the most commonly reported sleep disorder in the general population and is characterized by dissatisfaction with sleep quantity or quality. It is associated with difficulty initiating (sleep onset latency) or maintaining sleep and/or early-morning waking with inability to return to sleep.

Insomnia is not defined by a specific amount of sleep, as individuals with other sleep disorders may also report short sleep durations. Insomnia largely differs from minor sleep disturbance conditions in that it affects various aspects of life and has the potential to cause harm due to residual daytime drowsiness. Additionally, diagnostic criteria for insomnia specify adequate opportunity and circumstances for sleep and significant distress or symptoms during wakefulness. The opportunity for adequate sleep further differentiates insomnia from sleep deprivation, which has different causes and consequences. Criteria for the diagnosis of insomnia are listed in Table 1.

While general insomnia is classified as a sleep disorder, its pathophysiology suggests hyperarousal during sleep and wakefulness. Evidence of hyperarousal includes increased whole-body metabolic rate during

sleep and wakefulness, elevated cortisol and adrenocorticotropic hormone during the early sleep period, decreased parasympathetic tone in heart rate variability, and elevated electroencephalographic (EEG) activity during non-REM sleep. Functional imaging studies have demonstrated lesser degrees of differentiation in regional brain metabolism in patients with insomnia, when compared to imaging of patients who are considered “good sleepers.”

Two types of insomnia exist. Sleep onset insomnia is defined as difficulty initiating sleep; whereas sleep maintenance insomnia is defined as difficulty staying asleep and, in particular, waking too early and struggling to return to sleep.

Primary insomnias may result from a combination of psychological and/or social factors. Conversely, secondary insomnias are iatrogenic in nature and are, therefore, induced by a disease process, underlying medical condition, or external substance (e.g., medication, alcohol). Due to the various causes of clinical insomnia, clinicians must perform a thorough patient evaluation and make the diagnosis based on careful clinical history of the sleep problem and relevant comorbidities. Patient evaluation should include information regarding the individual’s sleep characteristics, daytime behaviors, medical and psychiatric history, medications, and symptoms of other sleep disorders.

Pharmacists are often the primary

1. Report of difficulty initiating sleep, difficulty maintaining sleep, waking too early, or sleep that is chronically non-restorative or poor in quality.

2. The reported sleep difficulty occurs despite adequate opportunity and circumstances for sleep.

3. At least one of the following forms of daytime impairment related to the nighttime sleep difficulty is reported:

• Fatigue or malaise

• Attention, concentration, or memory impairment

• Social or vocational dysfunction

• Mood disturbance or irritability

• Daytime sleepiness

• Motivation, energy, or initiative reduction

• Proneness for errors or accidents at work/home or while driving

• Tension, headaches, or GI symptoms in response to sleep loss

• Concerns or worries about sleep

Chronic Disease States

• Breathing disorders (obstructive sleep apnea)

• Cancer

• Circadian rhythm disorders

• Dermatologic disorders (pruritus)

• Endocrine conditions (diabetes mellitus, menopause, thyroid dysfunction)

• Gastrointestinal conditions (GERD)

• Heart failure

• Ischemic heart disease

• Neurologic disease (dementia)

• Pain

• Pulmonary disease

• Restless legs syndrome

• Anxiety

• Depression

• Post-traumatic stress disorder

Medication Classes

• Antidepressants

• Antihypertensives (beta antagonists, calcium channel blockers)

• Appetite suppressants

• Central nervous system stimulants (including caffeine

• Diuretics

• Glucocorticoids

• OTC allergy, cough, and cold medications

• Respiratory stimulants (theophylline)

• Sedatives and hypnotics

• Rheumatic disease (arthritis, fibromyalgia)

• Urologic disease (benign prostatic hyperplasia, nocturia)

point of contact for patients requiring assistance with health conditions which may potentially be treated with over-the-counter (OTC) agents. Appropriate management of chronic insomnia is critical, as both non-prescription and prescription medications may be used in treating chronic insomnia. Therefore, it is vital for pharmacists to understand chronic insomnia and its effects on patients. Furthermore, pharmacists play a crucial role in patient education with regard to patient expectations and potential adverse effects.

Insomnia occurs in patients of all ages and races; however, symptoms often vary between younger and older adults. Younger adults have an increased likelihood of reporting issues with sleep onset latency (difficulty falling asleep), whereas older adults generally report difficulty maintaining sleep or waking after sleep onset. Additionally, women are more likely to experience insomnia, especially following menopause and during late pregnancy.

Risk factors for development of

• Alcohol

• Illicit drugs

• Tobacco

chronic insomnia include female sex, increasing age, comorbid medical and/or psychiatric conditions, certain medications, shift work, and possibly unemployment and lower socioeconomic status. Patients with comorbid medical and/or psychiatric conditions are at highest risk, with psychiatric and chronic pain disorders having insomnia rates as high as 50 to 75 percent. Table 2 lists common comorbid disease states, medication classes, and conditions associated with insomnia. Approximately half of patients diagnosed with chronic insomnia report continuing symptoms at one year or more. Chronic insomnia is an independent risk factor for the development of depression anxiety; when these conditions occur concomitantly, a decline in response to treatment has been reported.

Patients with insomnia often complain of difficulty falling asleep, frequently waking, and difficulty returning to sleep or waking too early in the morning. Additionally, patients complain that sleep does not feel restful, refreshing, or restorative. While some patients may complain of one symptom, it is common for patients with chronic insomnia to experience a combination of

symptoms. It is also common for the presentation of chronic insomnia to vary over time.

Treatment is generally recommended if the insomnia has a significantly negative impact on a patient’s sleep quality, health, comorbid disease states, or daytime function. Treating insomnia is often challenging, as both modes of intervention have limitations. Treatment selection should be individualized with the patient’s values and preferences, availability of advanced behavioral therapies, severity and impact of the insomnia, and potential risks versus benefits, costs, and inconveniences

taken into account.

Goals of insomnia treatment include improvement in the quality and quantity of sleep, reduction of distress and anxiety associated with insufficient sleep, and improvement in daytime function. Treatment includes two broad categories — non-pharmacologic therapy and pharmacologic therapy. Insomnia may be managed with psychological therapy, medication therapy, or a combination of both. Complementary and alternative approaches such as acupuncture and Chinese herbal medicine have been used to treat insomnia; however, sufficient evidence is lacking in determining the safety and efficacy of these approaches.

Treatment of insomnia should include at least one behavioral intervention. Psychological and behavioral interventions are well-supported by scientific evidence. Behavioral treatments are indicated for both primary and secondary insomnia and include sleep hygiene education, stimulus control, relaxation, and sleep restriction therapy. Psychological intervention includes cognitive behavioral therapy. Such interventions are recommended as an initial approach in treating insomnia and may overlap with one another.

Sleep Hygiene. While the efficacy of sleep hygiene therapy alone has yet to be elucidated, several clinical trials have shown it to be superior to placebo. Achieving sufficient and adequate amounts of sleep is critical to both physical and mental health. Assessment for proper sleep hygiene involves reviewing an individual’s bedtime habits and rituals. According to the National Sleep Foundation, frequent sleep disturbances and daytime drowsiness are the most common signs of poor sleep hygiene. Sleep hygiene techniques are recommended as an initial intervention for all adults with insomnia, as the techniques allow personal habits and environmental factors that negatively impact sleep to be identified and corrected.

Patients should be advised to limit daytime napping to 30 minutes or less. Although short naps have been associated with improved alertness and performance, the National Sleep Foundation states that daytime napping cannot replace inadequate nighttime sleep.

Regular exercise promotes good sleep quality. As little as 10 minutes of aerobic exercise may drastically improve nighttime sleep quality. While it is often advised that patients avoid strenuous exercise before bedtime, there is no substantial evidence to support this statement.

Avoiding substances such as caffeine, nicotine, and alcohol within four to six hours before bedtime also helps promote rest. Caffeine and nicotine are stimulants and have

the tendency to keep patients overly alert during sleep. While alcohol has the potential to induce sleep initially, its effects are short-lived. Too much alcohol too close to bedtime has been associated with sleep disruption, due to the body processing the alcohol during the sleep cycle. Patients should be advised to avoid heavy or rich foods, fatty or fried foods, and edibles containing spicy, citrus, or carbonated beverages close to bedtime.

For patients who may not venture outdoors regularly, exposure to natural light during the day and darkness at night helps maintain a healthy circadian rhythm. Patients should also ensure they have a pleasant environment for sleep. This often includes eliminating televisions and other electronics at bedtime to associate the bedroom with sleep. Bedroom temperature should be cool and comfortable. The National Sleep Foundation recommends a bedroom temperature between 60 and 67°F as an optimal temperature. Patients should be encouraged to establish a bedtime routine to help the body associate sleep with the routine.

Stimulus Control. Stimulus control involves establishing a regular sleep-wake cycle by associating the bedroom with sleep. Recommendations for stimulus control include lying down to sleep only when feeling sleepy; exclusive use of the bedroom for sleep and sex only; removal of distractions such as electronic devices from the

bedroom; leaving the bed if unable to fall asleep within 20 minutes and returning to bed when sleepiness returns; and limiting daytime naps. Additionally, patients should be advised to set an alarm for the same time every morning, regardless of how many hours of sleep occurs during the night, allowing for the establishment of a regular sleep cycle.

Sleep Restriction. Sleep restriction has been beneficial in patients who spend a disproportionately long amount of time in bed attempting to fall asleep. Patients undergoing sleep restriction interventions are advised to limit the amount of time spent in bed to the number of hours they actually spend sleeping. This time should be no less than five hours. As the amount of time of sufficient sleep improves, sleep time is gradually increased so an individual spends the majority of his or her time in bed asleep.

Temporal Control. Temporal control also focuses on re-establishing a consistent sleep-wake cycle. Patients undergoing temporal control intervention are instructed to avoid daytime napping and wake up at the same time every day — regardless of the amount of sleep achieved during the prior night. The most commonly reported limitation of both sleep restriction and temporal control interventions is excessive daytime drowsiness.

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy. Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) is the cornerstone of non-

pharmacologic management of insomnia. CBT targets the underlying issues that lead to or exacerbate sleep problems such as maladaptive behaviors, thoughts, and beliefs. Treatment consists of a combination of sleep hygiene education, stimulus control, sleep restriction, relaxation training, journaling, and cognitive restructuring.

CBT is recommended as first-line therapy in older adults and has been shown to increase REM sleep and decrease wakefulness, improving homeostasis. Several randomized controlled trials have demonstrated improved mood and long-term sleep quality with the use of CBT.

Although CBT is considered firstline therapy, its availability is not yet widespread. One-on-one CBT requires the use of local clinicians with specific training. Not only may a patient have a difficult time finding such a clinician, but CBT may also be financially unsustainable for clinicians due to the complicated reimbursement system. Therefore, much interest has been generated in alternatives to face-to-face cognitive behavioral therapy.

One cost-effective and accessible way to provide CBT utilizes online platforms that a patient may log into and go through the basics of CBT via a step-by-step process for six to eight weeks. Another alternative is group cognitive behavioral therapy. Group CBT allows trained clinicians to interact with and treat multiple patients with chronic insomnia. Groups generally consist of five to

eight participants and treatment involves five sessions delivered on a weekly or biweekly basis. Lastly, video conferencing offers another lowcost and easily accessible mode of delivering CBT.

The use of sleep aids and selfmedication are very common among individuals with chronic insomnia. Therefore, it is imperative to ask about the use of sleep aids in any evaluation of a patient with insomnia symptoms. Several pharmacologic agents have gained FDA approval for the treatment of insomnia, while other agents may be prescribed “off label” for such treatment. Due to the potential adverse effects associated with the use of pharmacotherapy, risks and benefits of all agents must be considered on a case-bycase basis. Table 3 lists indications, dosages, and common adverse effects of medications indicated for the treatment of insomnia. Per the American College of Physicians clinical guideline for management of chronic insomnia, pharmacologic therapy should be supplemented with cognitive behavioral therapy, when possible.

Benzodiazepines. Agents such as triazolam and temazepam have historically been used in treating patients with sleep disturbances. Benzodiazepines (BZDs) bind nonselectively to any of four GABA-A receptor subunits, resulting in several possible outcomes including sedation, anxiolysis, amnesia, and muscle relaxation. The practice of using such agents, however, has

fallen largely out of favor due to an increase in observed adverse effects, especially in older adults. Furthermore, several randomized controlled trials have demonstrated insufficient or low levels of evidence to support regular administration of BZDs in the treatment of chronic insomnia.

Benzodiazepines approved by FDA for use in chronic insomnia include estazolam, flurazepam, temazepam (Restoril™), triazolam (Halcion®), and quazepam (Doral®). Of these agents, the American Academy of Sleep Medicine (AASM) only recommends triazolam and temazepam in the treatment of insomnia. Triazolam has a shorter half-life in comparison to the other agents and is, therefore, used in treating issues with sleep onset. Agents with intermediate half-lives, such as temazepam, should generally be reserved for patients with sleep onset or sleep maintenance problems. Longeracting agents, such as flurazepam, may improve sleep maintenance, but are rarely prescribed due to the higher risk of residual daytime effects. Potential adverse effects of BZDs include drowsiness, dizziness, lightheadedness, impaired motor control, and cognitive impairment. Benzodiazepines carry an FDA Boxed Warning regarding concomitant administration with opioid agonists, as combined use of opioids with BZDs or other drugs that depress the central nervous system (CNS) have resulted in serious adverse reactions, including slowed or difficult breathing and death. Pharmacists should

counsel patients and caregivers about the risks of slowed or difficult breathing and/or sedation, and the associated signs and symptoms. Lastly, benzodiazepines are classified as controlled substances and have the potential to become addictive. Pharmacists should exercise caution and clinical judgment in dispensing BZDs.

Non-Benzodiazepine Hypnotics.

Non-benzodiazepine hypnotics include zolpidem (Ambien®, Ambien CR®, Intermezzo®), eszopiclone (Lunesta®), and zaleplon (Sonata ®). Similar to BZDs, non-BZD hypnotics also target the GABA receptor. However, they have a much higher binding affinity for the alpha-1 subunit, which mediates sedation and amnesia. Non-BZD hypnotics are generally considered to have milder side effect profiles in comparison to BZDs, although administration dose and half-life also play important roles in selecting an appropriate agent. Agents with short half-lives, such as zolpidem and zaleplon, are recommended by current AASM guidelines for treatment of sleep onset insomnia. When administered during middle of the night awakenings, zolpidem has been associated with residual daytime effects at approved doses. Therefore, a patient should be counseled to take zolpidem prior to bedtime and only when he/she has adequate time to sleep. Conversely, zaleplon has not been found to produce residual daytime effects when taken at middle of the night awakenings. Eszopiclone and the extended-release zolpidem

formulations, with long half-lives, may be prescribed for sleep maintenance insomnia or sleep-onset insomnia. Long-term studies of both eszopiclone and extended-release zolpidem have shown continued efficacy without rebound insomnia, which has been observed with shorter-acting agents in the same class.

Potential side effects of nonBZD hypnotics include sedation, dizziness, impaired motor control, cognitive impairment, headache, amnesia, gastrointestinal symptoms, and unpleasant taste (eszopiclone). Parasomnias, such as sleep walking or sleep driving, are potentially dangerous side effects of this class of sleep medications. Parasomnias are often exacerbated when nonBZD hypnotics are concomitantly taken with alcohol or other sedating agents; at times other than the patient’s normal bedtime; or in the setting of untreated sleep disorders, such as restless legs syndrome or sleep apnea. Like BZDs, non-BZD hypnotics may be potentially habitforming and caution should be used when dispensing these agents.

Orexin Receptor Antagonists. Suvorexant (Belsomra®) is a relatively new agent indicated for treatment of sleep onset and/ or sleep maintenance insomnia. AASM guidelines, however, recommend suvorexant as a treatment for sleep maintenance insomnia versus no treatment in adults. Suvorexant acts by preventing the binding of wakepromoting neuropeptides orexin A and orexin B to their respective

temazepam sleep onset & sleep maintenance insomnia 7.5-30 mg triazolam sleep onset insomnia 0.125-0.25mg

Boxed Warning:

Concomitant use of BZDs with opioids may cause potentially fatal CNS depression

• drowsiness, dizziness, lightheadedness, impaired motor control, cognitive impairment

eszopiclone sleep maintenance insomnia 1-3 mg zaleplon sleep onset insomnia 5-20 mg zolpidem sleep onset insomnia IR: 5-10 mg Cr: 6.25-12.5 mg SL: 1.75-3.5 mg suvorexant sleep onset & sleep maintenance insomnia 10-20 mg

Boxed Warning:

Concomitant use of nonBZD hypnotics with opioids may cause potentially fatal CNS depression

• sedation, dizziness, impaired motor control, cognitive impairement, headach, amnesia, GI symptoms, unpleasant taste (eszopiclone), parasomnias

Concomitant use with opioids may cause potentially fatal CNS depression

• cognitive and/ or behavioral changes, complex behaviors, worsening depression, daytime impairment, sleep paralysis, hallucinations

doxepin sleep maintenance insomnia ≤6 mg

ramelteon sleep onset insomnia 8 mg

*Per the American Academy of Sleep Medicine

receptors (OX1R and OX2R). Antagonism of OX1R and OX2R is thought to suppress the drive to awaken. Separate clinical trials comparing suvorexant to placebo demonstrated no significant increase in adverse effects in patients taking suvorexant. Additionally, no clinical trials have demonstrated evidence of daytime residual drowsiness or withdrawal symptoms in patients administered suvorexant versus placebo.

Patients taking suvorexant should be counseled to administer the medication approximately 30 minutes prior to anticipated sleep and only if he or she has at least seven hours to devote to sleep. Food may delay the effects of suvorexant; therefore, patients should be counseled against taking suvorexant with or immediately after a meal. Adverse effects of suvorexant include cognitive and behavioral changes such as amnesia, anxiety, hallucinations, and other neuropsychiatric conditions; complex behaviors such as sleep driving or eating; worsening of depression including suicidal ideation in patients with comorbid