Welcome to the Asian Chamber

Welcome to the Arizona Asian Chambe thrilled to have you explore our vibrant Sun Magazine. As one of Arizona’s faste Asian Pacific Americans bring incredibl challenges. We’re here to support and g Our mission is to foster a thriving busin strengths of Asian Pacific American-ow economic growth, innovation, and cultu dedicated to creating an inclusive busin businesses, and advocating for impactfu

Our vision includes: Inclusive Collaboration: Building a entrepreneurs and professionals ca Economic Empowerment: Providin to help businesses succeed and cre Leadership Development: Cultivat programs and opportunities Advocacy and Policy Influence: Sh environment through strategic eng Global Connectivity: Connecting lo markets and opportunities.

Thank you for your support over the pa continued engagement, we’ll keep maki prosperous, inclusive Arizona. Stay tune for updates, events, and community sto let’s build a thriving future for our comm

Join the Asian Chamber of Commerce: www.azasianchamber.com/membership

Letterfromthe ExecutiveDirector

Meet the new Executive Director of the Arizona Asian Chamber of Commerce

I am truly honored to introduce myself as the new Executive Director of the Arizona Asian Chamber of Commerce. My name is Eric Day, and I am a firstgeneration Cambodian American. My parents, who survived the Khmer Rouge regime, instilled in me a profound understanding of perseverance and resilience. Their experiences have deeply influenced my journey and shaped my perspective on leadership.

Being Cambodian American means more to me than the language I speak or the cultural practices I follow It’s about embracing and accepting who I am despite the challenges and expectations we face This radical acceptance of my heritage and our collective struggles forms the foundation of my approach to leadership and my vision for the Chamber.

At the Arizona Asian Chamber of Commerce, we are committed to empowering diversity and driving prosperity. Our goal is to cultivate a thriving business ecosystem where Asian Pacific Americanowned enterprises can truly excel. I am excited to work towards this vision by fostering an inclusive environment, supporting economic growth, and advocating for our community.

As I step into this role, I look forward to contributing to our shared mission of celebrating diversity and driving economic development Together, we will build a future of lasting prosperity and success for Asian Pacific American businesses in Arizona I am eager to collaborate with you all to create a vibrant and interconnected business community that reflects our unique strengths and collective efforts.

ASIAN CHAMBER MEMBERSHIPS

CulturalFootprints: TracingImmigration inArizona

BY BEI DI GULINO

Uncover the rich tapestry of Asian settlement in Arizona, where diverse cultures have shaped the state’s history and identity.

The history of Arizona is deeply intertwined with the stories of its immigrant communities, each contributing to the state's diverse cultural and economic fabric. Among the first to migrate into Arizona include the Filipinos, Chinese and Japanese communities. This article delves into the history of Asian immigration into Arizona, exploring their initial arrivals and the growth of their communities.

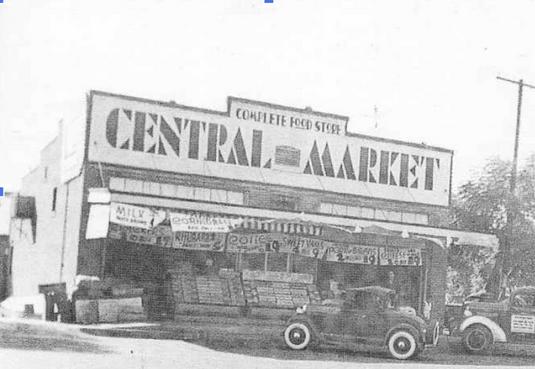

Chinese Immigration into Arizona

According to the 1860 census, the first Chinese man in Arizona was William Tsching, residing in Arizona City, now known as Yuma. He worked as a cook on a Colorado River steamboat. Ten years later, there were twenty-one Chinese laborers working in the territory as miners, cooks, and laundrymen. This small number rapidly increased in the 1870s, partly due to a virulent anti-Chinese movement sweeping through California. In contrast, Arizonans were more accepting of the incoming Chinese workers who contributed significantly to railroad construction, copper mining, and service industries where labor was in high demand Chinatown communities were established in Tucson and Prescott, with the largest influx of Chinese immigrants occurring during the construction of the Southern Pacific Railroad from 1878 to 1880. The Arizona Sentinel noted the arrival of seven hundred Chinese laborers in a single week in November 1878. This crew laid the tracks from Yuma to Maricopa.

In 1872, three men and two women, the first Chinese to move to Phoenix, opened the first laundry in what was then little more than a dusty trailside camp of adobe shacks and tents. The number of Chinese remained small until May 1879, when the Southern Pacific Railroad halted work on railroad construction across Arizona due to the intense summer heat The tracks ended at a new railhead called Terminus (near Casa Grande), thirty-five miles south of Phoenix, and many of the temporarily unemployed Chinese workers moved to Phoenix to find work and residence for the summer. When rail construction resumed in January 1880, most Chinese returned to work, but at least 164 are known to have stayed in Maricopa County, creating a sizeable Chinese community in and around Phoenix. Those who settled south of Phoenix began growing vegetables, a scarce commodity in a valley dominated by grain farmers. Those who moved into town started grocery stores, restaurants, and laundries and found work as domestic servants, cooks, gardeners, and vegetable peddlers Early Chinese businesses and boarding houses were clustered along the west side of Montezuma Street (1st Street), extending a halfblock north and a half-block south of Adams Street Through the 1880s, this area grew to become the Phoenix Chinatown

FirstInauguralBanquetand BalloftheProtectivePhilippine PioneersofAmerica,1941.

Filipino Immigration into Arizona

No Filipinos were recorded as living in Arizona in 1910, according to the federal census. In 1920, there were ten Filipinos listed, and by 1930, there were 472 living in Arizona The number of Filipinos decreased to 232 by 1940 During this period, the majority of Filipinos were male and over the age of twenty-one However, the actual numbers are likely underreported since many Filipinos were involved in seasonal agricultural labor, making it difficult to accurately measure their population. The majority of Filipinos who came to the United States before the mid-1930s did so in response to the integration of the Philippines into the global market as an agricultural export economy.

This process, which began with Spanish colonization, advanced under American rule. As export crops such as sugar, tobacco, and coffee grown on large-scale plantations became more important, small-scale rice farming declined and was displaced by tenancy Displaced workers came to Hawaii as early as 1906, where they replaced Japanese workers as a cheap labor force Between 1906 and 1934, over 100,000 sakadas, or contract workers, arrived from primarily Ilocanospeaking northern Luzon. Though over 50 percent eventually returned, many stayed in Hawaii and formed communities there or moved on to the mainland. The path to the United States was often via Hawaii, with almost 20,000 coming to the mainland between 1906 and 1932.

Unlike their Japanese and Chinese counterparts, Filipino workers could immigrate to the United States as nationals, without legislative constraints. By the 1920s, Filipino students and laborers were self-supporting and filled niches in local economies, especially as service workers in urban areas. Typically, they worked in restaurants, hotels, private clubs, and as personal servants. In rural areas, they worked in agriculture. However, laws were passed by various legislatures, including Arizona, forbidding miscegenation between "white" and "Mongolian" partners.

Just as Chinese and Japanese immigrants had faced discrimination, Filipinos were also targeted by racist laws and other anti-Filipino activities, particularly in California Filipino immigrants followed a specific pattern in settling in Phoenix. Initially, their families were transient, moving from one rental home to another and holding various service-related jobs. Eventually, they saved enough money to purchase houses. In many instances, they rented out rooms to other Filipinos. The Phoenix Filipino Americans, possibly due to their matrilineal connections to the Hispanic community, primarily settled in an area of South Phoenix bounded by Van Buren Street on the north, 15th Avenue on the west, the Salt River on the south, and 20th Street on the east Many also moved into Santa Maria, a small community located southwest of Phoenix, near 70th Avenue and Lower Buckeye Road

Japanese Immigration into Arizona

Japanese immigration to the United States began at a virtually unnoticeable rate In 1870, there were fifty-five Japanese living in the country, and by 1880, the number had grown to only 148 However, with the passage of the Chinese Exclusion Act in 1882, many more Japanese started migrating directly to California, often encouraged by businessmen who wanted a compliant work force to replace the dwindling population of Chinese laborers. Over the next decade, 2,000 Japanese arrived in the United States. Japan removed most restrictions on emigration in 1896 and the U.S. annexed Hawaii in 1898, prompting an even larger wave of immigrants to come to California. By 1900, more than 24,000 Japanese had arrived on the West Coast Almost all of them were men; only 985 women had made the journey to America

Hachiro Onuki was the first Japanese to arrive in Phoenix. As a young man, he visited Philadelphia in 1876, and then went on to Tombstone, where he worked as a freighter hauling fresh water for miners. He became a naturalized citizen in 1879, and took a more Anglicized name, Hutchlew Ohnick.

In 1886, Ohnick moved to Phoenix and joined with two white businessmen to create the Phoenix Illuminating Gas and Electric Company. The town's first power supplier received a twenty fiveyear franchise and Ohnick was the superintendent of the gas works and generators for several years, until he sold his interest in the company In about 1900, he started a truck farm south of Phoenix called Garden City Farms Shortly thereafter, Ohnick moved his family to Seattle where he opened the Oriental American Bank. He died in California in 1921.72 There were no other Japanese in central Arizona until 1897, when the Canaigre Company of Tempe hired one hundred Japanese to gather canaigre (a perennial herb) roots along the Agua Fria River. This venture, using the wild plant to produce tannic acid, was unsuccessful, and the Japanese workers apparently returned to Califo

The history of Asian migration into Arizona is deeply rooted, with Chinese, Filipino, and Japanese communities being among the earliest settlers who contributed significantly to the state's cultural and economic development. These groups laid the groundwork for a diverse and vibrant Asian presence in Arizona. While this article has highlighted the experiences and contributions of these pioneers, it is essential to acknowledge that many other Eastern and Southeast Asian communities have also found a home in Arizona From Vietnamese and Korean to Indian and Thai immigrants, each subgroup has enriched the state's tapestry with unique traditions, cuisines, and cultural practices. As we celebrate the rich heritage of Arizona's Asian communities, we pay tribute to all the diverse groups whose stories and contributions continue to shape the state’s multicultural identity

PICTURES PROVIDED FROM THE TADANO FAMILY

The success of Asian Pacific American entrepreneurship in recent years has been nothing short of remarkable As the fastest growing demographic in Arizona and across the nation, our businesses have not only contributed economically on an astronomical level, but are carving spaces for greater representation, inclusivity, and innovation. Asian Pacific Islander entrepreneurs have not only achieved personal success, but are fostering pathways within their communities for the next generation.

With over a decade in the beauty industry, mainly as a makeup virtuoso on YouTube, Hannah recently launched her own lash line that caters to the Asian demographic. She curates products that are designed to enhance the unique features and needs common to Asian facial features and her mission is to increase Asian representation in the beauty industry.

Hannah Cho is a Korean American adoptee and local Phoenician. Wearing multiple hats, she is an entrepreneur, influencer, and community advocate; who has a passion for our growing Asian community and all things beauty-related

Recently, the Arizona Asian Chamber of Commerce had the opportunity to discuss her growing Asian-owned business, the necessity of representation, and how her identity inspires her work.

ARO: As an Asian American woman, what was your motivation to start your own business?

Hannah: Because there wasn’t a space yet. And so, starting out on YouTube - 15 years ago - before Michelle Phan was Michelle Phan, at that cusp, I was still trying to learn, how do I do makeup for my eyes? I didn’t even know what it was called back then So YouTube 15, 18 years ago is what taught me that I had monolids and “Oh wait there’s people that struggle, they have short, stubborn eyelashes like mine?” And started consuming the content and then went there wasn’t enough, there was only a couple people you could find and so then I said, “Okay, I’m going to start making my own content” and it really grew from a place of…I tested eyeliners for my monolids that wouldn’t flake, that would hold up all day. And mascaras for my short stubborn lashes and it just…thousands, thousands of views. And I went, there’s a need for this. And as I grew and got older on it, realized that there wasn’t the products… there wasn’t a hub for it So I thought, well I’m just going to start building that

ARO: When you see the representation you are growing yourself, what are your hopes from that foundation you are setting?

Hannah: When people see Asian people, it’s not just “foreigner, foreign”. Like that thought doesn’t come to mind anymore, because I think that’s what separated us for so long.

ARO: The perpetual foreigner.

Hannah: Yes. So breaking that and also so the next generation of young girls…that they don’t grow up with that same loneliness, that same ‘seeking’ that we had to that it’s just there for them

ARO: Something particular and inspiring to highlight about your brand is that you are redefining “Yellow”. And for Asian Americans, that is very significant…what was your thought process for redefining that term and using it for your branding?

Hannah: Using the color yellow was really intentional And it came really easily

Growing up here, my best childhood friend, who I’m still best friends with - she’s Nigerian. And so we grew up here. She didn’t have a people, I didn’t have a people. We bonded over the fact, she would joke she was an “ oreo ” , black on the outside, white on the inside. And I would joke that I’m a Twinkie, yellow on the outside, white on the inside. And we would play around a lot. So even doing social media together, we would call ourselves Ebony Yellow-y. Just playing on and making fun of our labels that people have used negatively. And so that was, when creating this brand, it was really easy for me to go “Yellow” I want to claim that color back why have all these negative things around it? Let’s make it positive, let’s claim it back - make it something to celebrate

ARO: For the next generation who may still struggle with their identity or may still not have that representation, what are your hopes for them? What kind of fulfillment will they get by seeing your representation?

Hannah: I hope that they feel seen. I hope that they know there is a safe space. But I think aside from that…there’s this era right now that’s happening and it’s a very crucial time that these niche businesses and niche communities that are growing, that still feel small - I want it to be big I don’t want it to be, “Oh we ’ ve carved out this corner of the world of the beauty industry of ‘whatever’” No, I want it to be, “We ARE the space ”

LIVE MUSIC FOOD VENDORS

Asian Voting Matters in 2024

BY AADITYA UGALE

As the 2024 elections approach, the significance of the Asian American and Pacific Islander (AAPI) vote has never been more evident. This demographic, often called the "sleeping giant" in American politics, is waking up and making its presence felt in crucial ways Here's why Asian voting matters in 2024:

The AAPI population in the United States has been growing rapidly. Pew Research Center reported that the Asian American population grew by 81% between 2000 and 2019, making it the fastest-growing racial or ethnic group in the United States. By 2020, there were approximately 23 million AAPIs in the U.S., making up 7% of the total population. By 2060, we can expect this number to double, making their influence on American politics more essential.

We have also seen an increased voter turnout among AAPIs in recent elections In the last presidential election, about 11 million AAPIs were eligible to vote, and voter turnout increased by nearly 40% compared to 2016 This surge was driven by a combination of factors, including heightened political awareness/education,

“The AAPI vote is no longer a sleeping giant but a vibrant and essential part of the American democratic fabric”

targeted outreach by political campaigns, and a sense of urgency regarding safety, immigration, healthcare, and, most importantly, the occurrence of “Stop Asian Hate,” racial justice. The AAPI vote is particularly crucial in several key swing states In states like Arizona, Nevada, and Texas, the AAPI population has grown rapidly, making them a key group in turning the tides for closely contested races This was seen in Georgia, where the state shifted towards the Democratic Party in 2020 due to Asian voting.

One of the unique aspects of the AAPI electorate is its diversity. The AAPI community is not monotone; it is made up of people from various countries, cultures, and political preferences. Leaders need to understand and address the diverse needs and concerns within the AAPI community, which is essential for any political party aiming to secure their votes

So why does AAPI voting matter? Because several key issues resonate strongly with AAPI voters and connect all of them together.

Many AAPIs are first-generation immigrants or descendants of immigrants. Policies that address family reunification, visa backlogs, and pathways to citizenship are of extreme importance This, in tandem with access to affordable healthcare, is a significant concern, especially in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic, which disproportionately affected minority communities. Most importantly, rising incidents of anti-Asian hate crimes have pushed the community to demand stronger protections and policies promoting racial equity.

The increasing political engagement and representation of AAPIs are also noteworthy. In recent years, there has been a surge in the number of AAPI candidates running for office and winning at local, state, and national levels The 117th Congress, for example, included a record number of AAPI members, reflecting the community's growing political clout

The 2024 elections are where Asians can share their voices, and we now know that the AAPI vote is a critical factor that has shaped and should shape the political landscape With the AAPI community's rapidly growing population, increasing voter turnout, and influence in key swing states, AAPIs are emerging as a powerful force in American politics Political parties and candidates must recognize and address the diverse concerns of the AAPI community to secure their support and ensure their voices are heard in the electoral process. But most importantly, the AAPI community needs to make their voices heard and join together in solidarity to make the rest of the country realize that they are a force to reckon with.

The AAPI vote is no longer a sleeping giant but a vibrant and essential part of the American democratic fabric, making them a key demographic to watch in the upcoming 2024 elections

Why advertise with us?

Want to spread the word about your company or event? Get your advertisement in Arizona’s most influential and pivotal Asian American publication Our readership is comprised of corporate sponsors, small businesses, influencers and leaders of the community, universities, public officials, and members of the general public.

What is your mission?

The Asian Sun features content from public officials, professors, scholars, entrepreneurs, community leaders, and giants of the industry It has grown over the years and is distributed statewide and in other major cities in the United States. All advertisement content should align with the Asian Chamber’s branding and mission to qualify.

Think we’d be a good fit? View our advertisement opportunities below and contact

Advertisement Packages

Advertisement packages bundle all of our promotional deals. Receive magazine ads, social media ads, articles in the Asian Sun, and exclusive membership discounts Package pricing varies Magazine Advertisements

Magazine ads are available for purchase in various sizes and pricing. Individualized ads (not to be confused with advertisement packages) are offered on a case-by-case basis as approved by the Asian Chamber

Social Media Advertisements

Sponsored social media ads will be featured on the Asian Chamber’s Facebook and Instagram channels and can run for a varied duration.

Want More Info?

Want more details about our advertisement opportunities? Email us your questions or request our full advertisement kit with pricing at info@azasianchamber com.