Beirut Beirut Tower, Ground floor, Zeitoune Street

Across from Beirut Marina, Solidere

Beirut - Lebanon Phone + 961 1 374450, Fax + 961 1 374451, Mobile + 961 70 535301 beirut@ayyamgallery.com

Damascus Mezzeh West Villas

30 Chile Street, Samawi Building

Damascus - Syria Phone + 963 11 613 1088 - Fax + 963 11 613 1087 info@ayyamgallery.com

Dubai 3rd Interchange, Al Quoz 1, Street 8 P.O.Box 283174 Dubai - UAE Phone + 971 4 323 6242 Fax + 971 4 323 6243 dubai@ayyamgallery.com

© All rights reserved 2009

Modern Robin Hood

When meeting Syrian painter Nihad al-Turk, you are faced with a restless man, a modern Robin Hood, as he likes to call himself, who is burdened by poverty, social and political injustice yet unable to restore order. Born to a poor family in Aleppo in 1972, life didn’t go easy on Al-Turk. Finishing only the primary school, having no money and experiencing a series of debacles in his personal life however made Al-Turk all the more determined to achieve his dream and follow the footsteps of painters like Picasso and Da-Vinci, his ideal at the time.

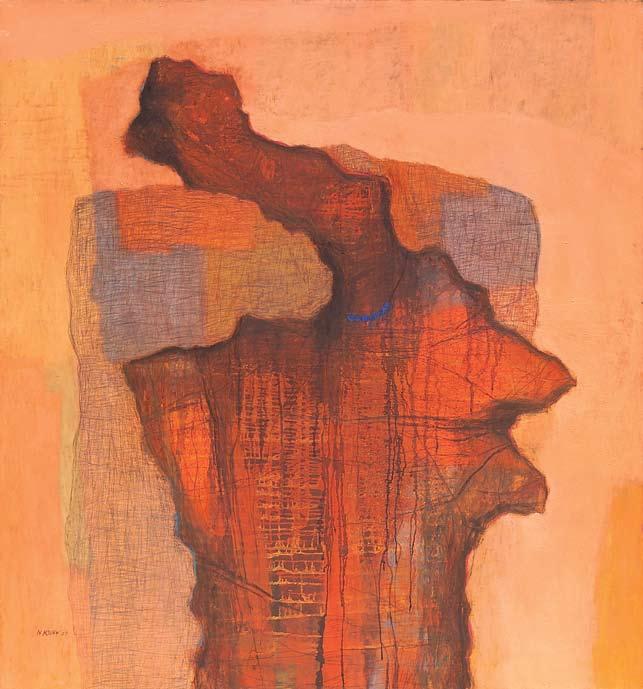

'My works are a reflection of me,' Al Turk tells me. His paintings however depict a deformed, chained character, heavy with disappointment and sorrow. In fact, Al-Turk believes that every man is deformed from the inside and that life is about improving our deformed selves through our lives by love.

As Al-Turk finds life unjust and people only further deform and destroy it, he resorted to the world of animals that he sees as more righteous and innocent. He created a mythical creature that unites the contemporary man, which is deformed, bewildered and disappointed in life and the animals.

'It’s people who deform life and worse they try to chain animals and organize their daily lives and meals according to their taste depriving them from their primitivism.' He says.

A night in his studio’s garden in Dummar marked a turning point in Al-Turks career. Awakened by a little mouse, Al-Turk felt his deep loneliness. By dawn, he depicted himself as a lonely deformed flower vase and painted the mouse as a deformed animal with seven legs. Since then the little animal has been present in all his paintings and has become a trademark of Al-Turks latest works.

Though moved to still life, the sense of alienation and oppression never parted Al-Turk’s works; avoiding the traditional still life stereotype, he deforms every element in his paintings and adds a living creature to each one.

'I can’t imagine painting a still life without life in it. It’s simply too rigid and lifeless that way.'

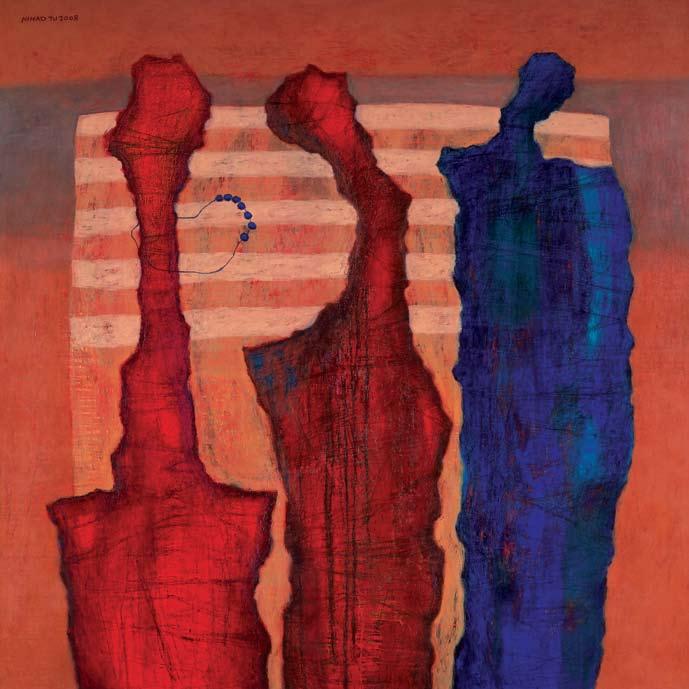

Despite their depressive content, Al-Turk’s paintings bear a lot of strength and love. His intensive use of red colors adds strength and vivacity to the works. Far from the traditional interpretation of red as the color of love and revolution, Al-Turk sees it as a spark, action and a symbol of his intense love for life; for though he never lived on easy street, Al-Turk is very ardent and optimistic about his future. He has already won several prizes, among them the golden prize in the 5th Latakia Biennale in 2003 and his paintings has been sold in international auction houses.

Nevertheless, Al Turk believes his art will remain heavy with the poverty, political and social injustice that governs the world. 'As long as there’s no justice in life, tension will never leave my life and therefor my paintings.' He says.

By Nadia MuhannaAesthetics of Distortion

Nihad Al-Turk was born in Aleppo in 1972 in a poor neighborhood. Al-Turk believes that the suffering and poverty of his mother are what that made him a painter. In fact, his mother got married at the age of fifteen. She had only one dress. “I’ve always held the sorrow and suffering of my mother,” says Al-Turk who explains how he became a painter: “My brother was a painter and I’ve always watched him.” At the same time, he denies that painting is a destiny. “I could’ve been a professional politician or a footballer. I lead life with pleasure. I give out my energy wherever I go. I’ve energy and there’s a free being that keeps provoking me. Drawing was the closest activity to my heart.”

Four months in prison, however, were very crucial to him. He was actually jailed because of painting as he quit his compulsory military service for almost a month. Painting became his torture while in prison. “Jailors used to throw the drawing pad to me and order me to finish the paintings the next day. I used to paint according to the taste of jailors who would give my paintings to their beloveds as gifts. I’ve drawn hundreds of paintings while I was there under the pressure of jail. One day, I fainted because of hunger while I was painting.”

Yet, what did imprisonment do to his experience as artist? Al-Turk says: “I was transparent. Something broke inside me. I’ve become very violent. The mythical creature in my painting was born out of jail. This creature has become an integral part of my works. Even if you go to silent nature, you’ll find the creature there. It’s my attitude towards life. You can also see that this creature changes, is transformed and becomes bigger. The creature has now horns. Sometimes you find that it looks like a snake or devil. Instead of becoming more polite, it becomes more exotic. I can say that science fiction films in addition to myths that lie back in my imagination are what feed the image of that creature in my head. This creature looks like the works of Giacometti as I tried to simulate his works in the beginning.”

On top of that, Al-Turk, is fond of observing evil. “I believe that my task is to observe evil in life. Evil seduces me more. The mythical creature is the result of the contemporary human being. Since human being is viewed as ‘a distorted mass working hard to seek the best’, this is the meaning of finding a clear spark of hope in this creature, which is broken and deformed, but loves life at the end of the day. For example, I love the shape of the hunch, which points to a struggling and a repressed human being,” says Nihad Al-Turk.

This is why the characters of Al-Turk are a mixture of fear, heroism and distortion. They are his visual and epistemological memory that takes him towards Expressionism. “I cannot work in a decorative way. These scratches on the surface of the painting satisfy me and make me feel at peace. This suits my nervousness and edginess,” says Al-Turk. We are not sure whether this edginess and strong emotions are what make his painting sway between darkness and shade, and strong light. This play which is considered an essential part of the formation of the painting is part of its aesthetics, as well as other aesthetical aspects such as the lightness of the characters of his paintings and the balance even in the most distorted shapes. Of course, we should add to this the beautiful surface and collage.

In addition to all of that, we always see in Nihad’s work a necklace made up of seven beads, as if it is his own signature on the painting. It is his own personal necklace which he made in prison from olive seeds. Number seven refers to his family members whom he adores. Nihad goes further to use number seven in many elements in his painting. Thus, apart from the beads of the necklace, he attaches seven legs to the animal, as well as seven horns and a crown with seven peaks and so on.

“But forget all of this,” says Nihad. “Neither the creature, nor the necklace is an identity. My identity is the technique, which comes from my own laboratory, rather than from the laboratories of art academies.” Nihad has not studied art in an academic setting. Because of that, perhaps, he has been exercising photography ever since he was a child as a form of challenge. He had always found himself in a state of war with the painting. You notice that he has abundant anxiety and tension on the surface of the painting. He did not study at art academies. Yet, he was able to stand on solid feet on the scene of plastic art, as if he were out of flock, as a lone and unique, but sad, bird.

Nihad Al-Turk

The power of nature over nurture is evident in the artistic practice of Nihad AlTurk. Born in 1972 in Aleppo, northern Syria, the artist grew up in an ancient city far removed from the classrooms and studios of artistic academia. Driven by an innate hunger for self-expression, Al-Turk spent his formative years experimenting on paper and later canvas; approaching each individual work as a separate challenge.

Such frustration is reflected in the tension of his compositions with their carefully chosen subject matter, from still life studies to quasi-mythical portrayals. The dimensional naivety of his works combines with a bold use of color that is contained within lines screaming out in anxiety. While some may feel that AlTurk has achieved a maturity in his artistic expression, he continues to push the limits of his technique within his studio-laboratory.

Al-Turk’s most recent exhibitions: Mark Hachem Gallery in New York in 2008, Ayyam Gallery Damascus and Dubai in 2008 and 2009, and the Inaugural Exhibition of Damascus’s Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art in 2009.

Over the last decade, recognition of Al-Turk's talent has steadily increased; his mixed media works have since captivated viewers and collectors in Lebanon, Istanbul, Dubai, the USA, Paris and Switzerland.

Rashed Issa Palestinian Critic Cultural Correspondent of Assafir Lebanese newspaper in Damascus

'Three Friends' 180 X 180 cm. Mixed Media on Canvas 2008