Informational

[1916-2025]

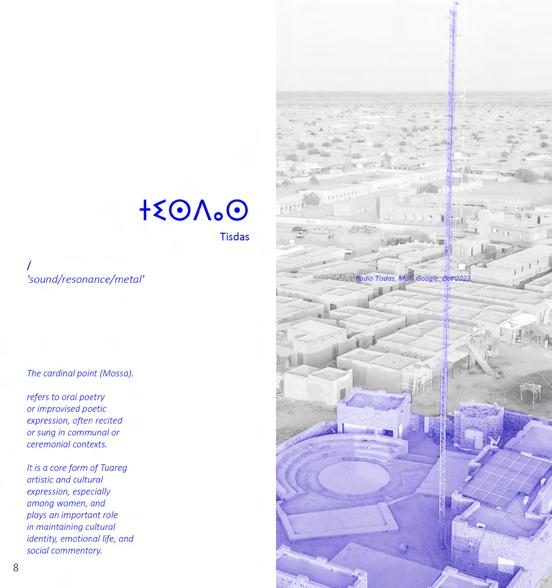

Exploring the tensions and possibilities of cross-border sonic resistance—with the aid of radio –considered as a continuation of oral traditions—in confronting colonialism and state control over conceiving and expression.

[brochure]

[brochure]

1-2-3

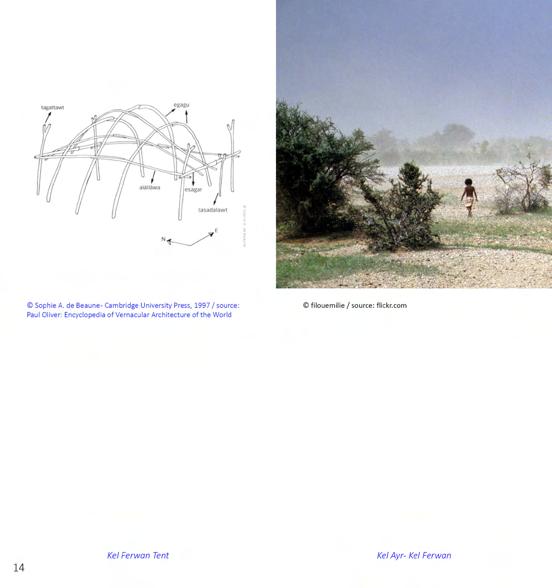

The Kel Ferwan, a Tuareg tribe originally settled near Boughoul in the Tessiderak Valley east of Agadez, strategically positioned themselves within territory historically controlled by the powerful Iteseyen confederation. This settlement asserted not only physical presence but also political influence in the Aïr region. In the 19th century, the Kel Ferwan gradually moved closer to Agadez, establishing camps in Azzemadren—now the boundary between old quarters and administrative districts. Following the 1916–1917 Tuareg revolt against colonial rule, most Kel Ferwan transitioned toward nomadizing in southern Agadez, while their leadership increasingly settled permanently in Aderbissanat (Aboubacar Touraoua, 2013). This transition exemplifies the broader process of sedentarization impacting the Kel Ayr confederation.

[This shift from mobile nomadism to sedentary life has profound implications beyond geography: it disrupts the traditional modes of knowledge transmission and social interaction. The oral traditions that once thrived through personal encounters—expressing, listening, and storytelling—have become immobilized. The communal flow of information, essential to maintaining cultural cohesion and political agency, is now constrained within fixed physical and social borders.]

Iformational immobilization is starkly illustrated by the recent suppression of media freedom following the July 2023 coup d’état in Niger. Since the military junta seized power, there has been systematic repression of journalists and media outlets. Notably, Sahara FM’s founder Ibrahim Diallo reported arrests of key journalists including Hamid Mahmoud, Mahaman Sani, and Massaouda Jaharou (IFJ, Groupe Aïr Info).

Additionally, on June 6, two more journalists, Hamid Mahmoud and Mahamane Bachir, were arrested (Groupe Aïr Info) as well.

[Such suppression silences independent voices and disrupts the vital flow of information, further stiffening the social and political landscape.

From a legal perspective, this immobilization engages multiple dimensions of environmental criminal law and human rights law:

The principle of environmental justice underscores that indigenous and nomadic populations, such as the Kel Ferwan, have the right to maintain their cultural practices and mobility patterns without disproportionate harm or displacement. The forced sedentarization and immobilization constitute a form of environmental harm and cultural destruction that may qualify as a crime against the environment under emerging international legal norms.

The military and political control over territories, including airspace surveillance and infrastructure domination, results in environmental degradation and the destruction of nomadic livelihoods. Such acts may fall under ecocide or environmental crimes as defined by the Rome Statute and proposed international frameworks on ecological protection, which recognize the deliberate or reckless destruction of ecosystems affecting vulnerable populations.

The immobilization of people and information contributes to the stiffening of the socio-environmental landscape, restricting the ability of Tuareg communities to respond adaptively to environmental changes, a violation of their environmental rights and self-determination as indigenous peoples.]

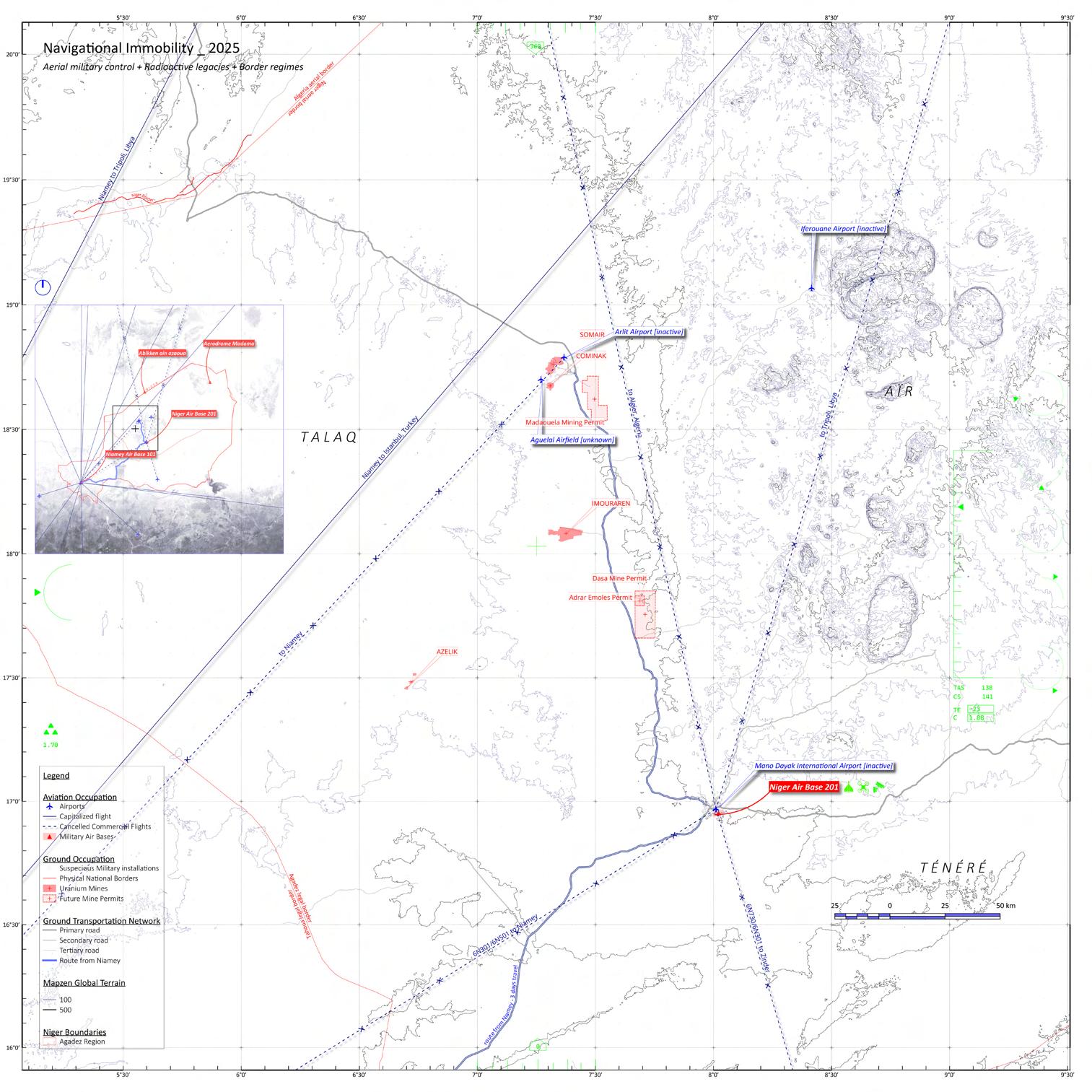

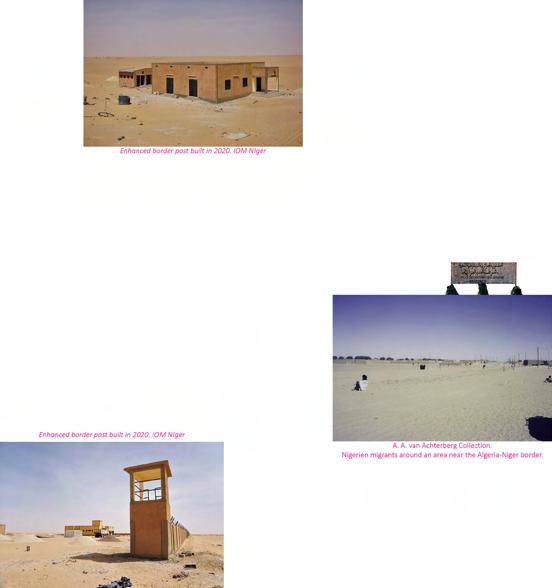

Exploring the contrast between pre-colonial nomadic navigation across the Sahara and the post-colonial immobility imposed by border control and surveillance— both on the ground and in the airspace.

Exploring the contrast between pre-colonial nomadic navigation across the Sahara and the post-colonial immobility imposed by border control and surveillance— both on the ground and in the airspace.

[brochure]

[brochure]

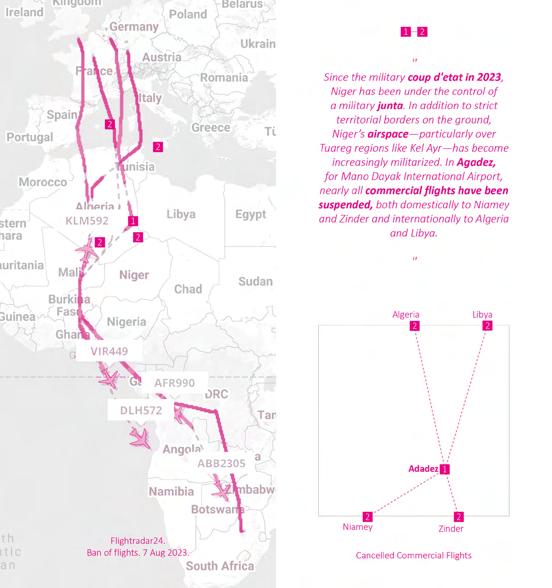

1-2

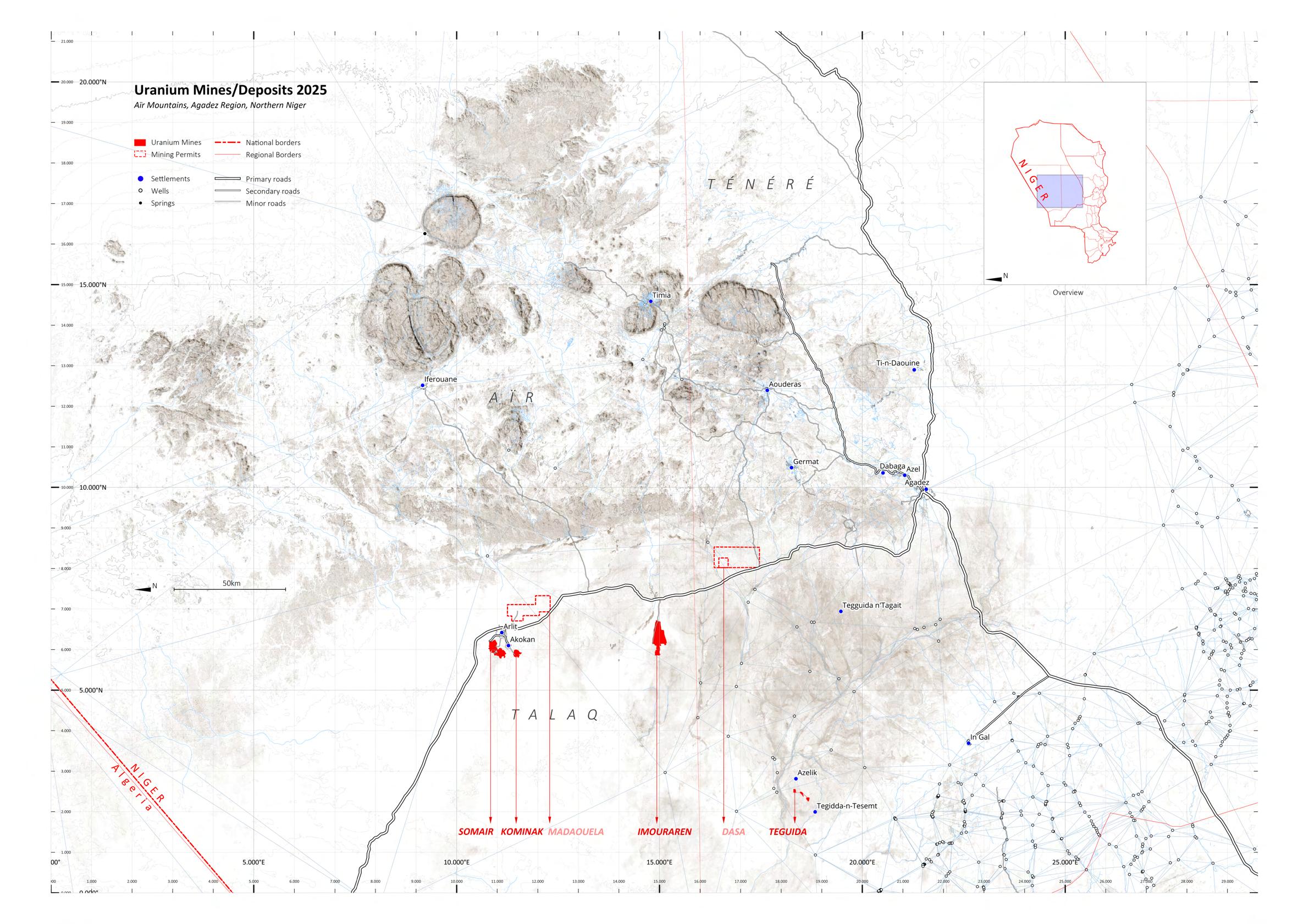

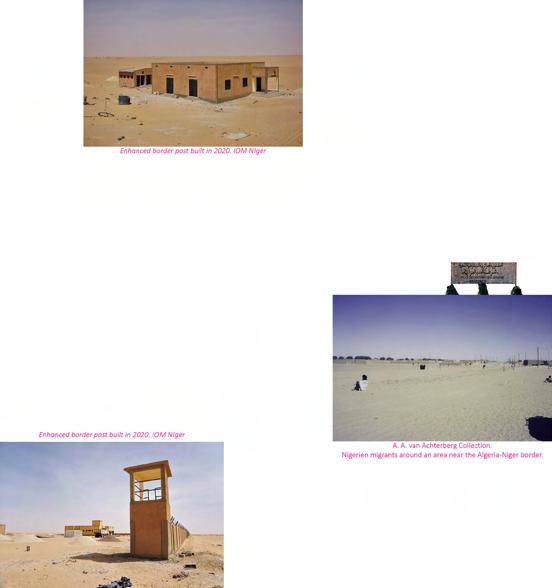

Since the military coup in 2023, Niger has been under the control of a military junta. In addition to strict territorial borders on the ground, Niger’s airspace—particularly over Tuareg regions like Kel Ayr—has become increasingly militarized. In Agadez, for Mano Dayak International Airport, nearly all commercial flights have been suspended, both domestically to Niamey and Zinder and internationally to Algeria and Libya.

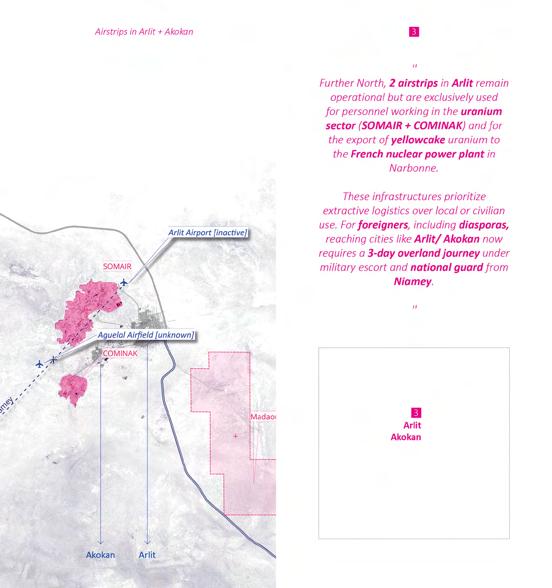

3

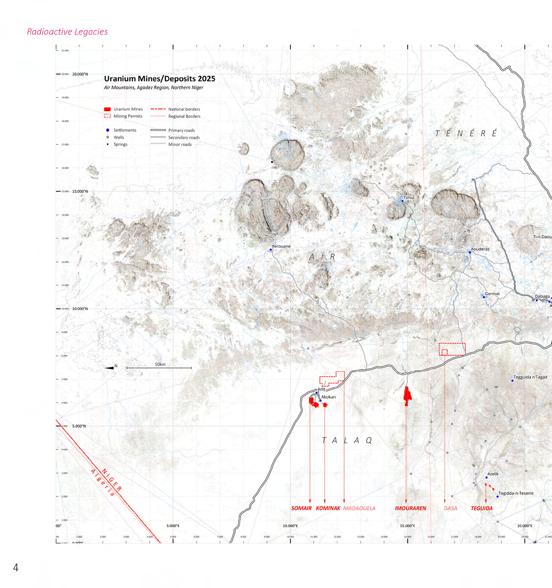

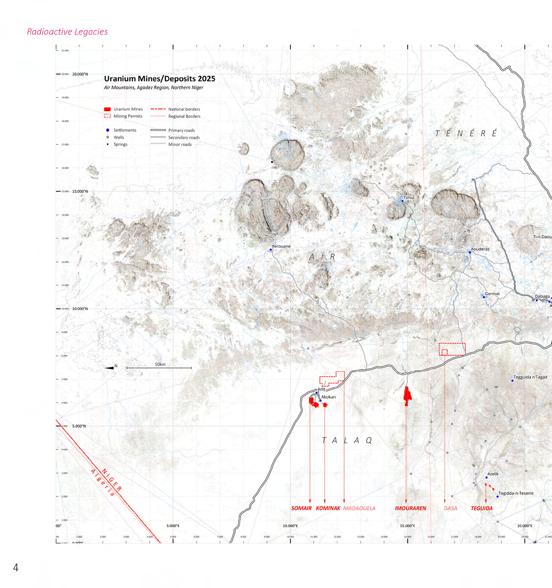

Further North, two airstrips in Arlit remain operational but are exclusively used for personnel working in the uranium sector and for the export of yellowcake uranium to the French nuclear power plant in Narbonne before the closure.

[These infrastructures prioritize extractive logistics over local or civilian use. For foreigners, including diasporas, reaching cities like Arlir/ Akokan now requires a three-day overland journey under military escort and national guard from Niamey.]

4

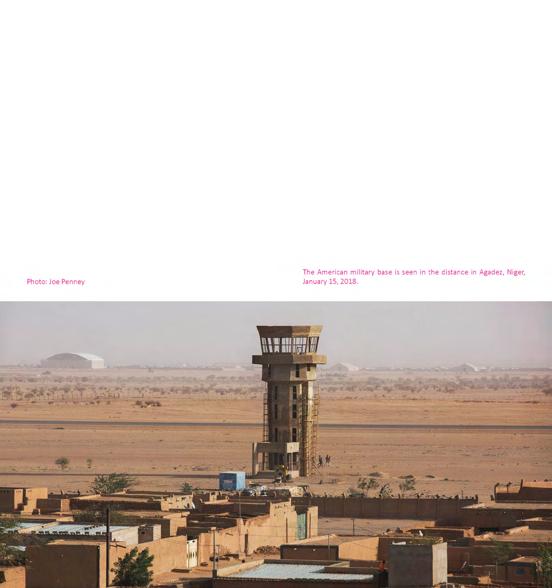

Go back to Agadez itself—historically the principal hub for inter-confederational Tuareg migration and trans-Saharan trade long before colonial rule—has become the site of intensified securitization. In 2019, the United States constructed Nigerien Air Base 201 adjacent to Agadez Airport, ostensibly for counter-terrorism operations. Equipped for drone surveillance and strategic monitoring, the base served American interests until the post-coup withdrawal. It is now operated by the Nigerien military.

[It protects extractive infrastructure (uranium, oil pipelines). It supports EU external border fortification (Frontex deals). It neutralizes “risky” populations, like the Tuareg, they regard THEM AS ‘red bodies’ under the pretext of counterterrorism.]

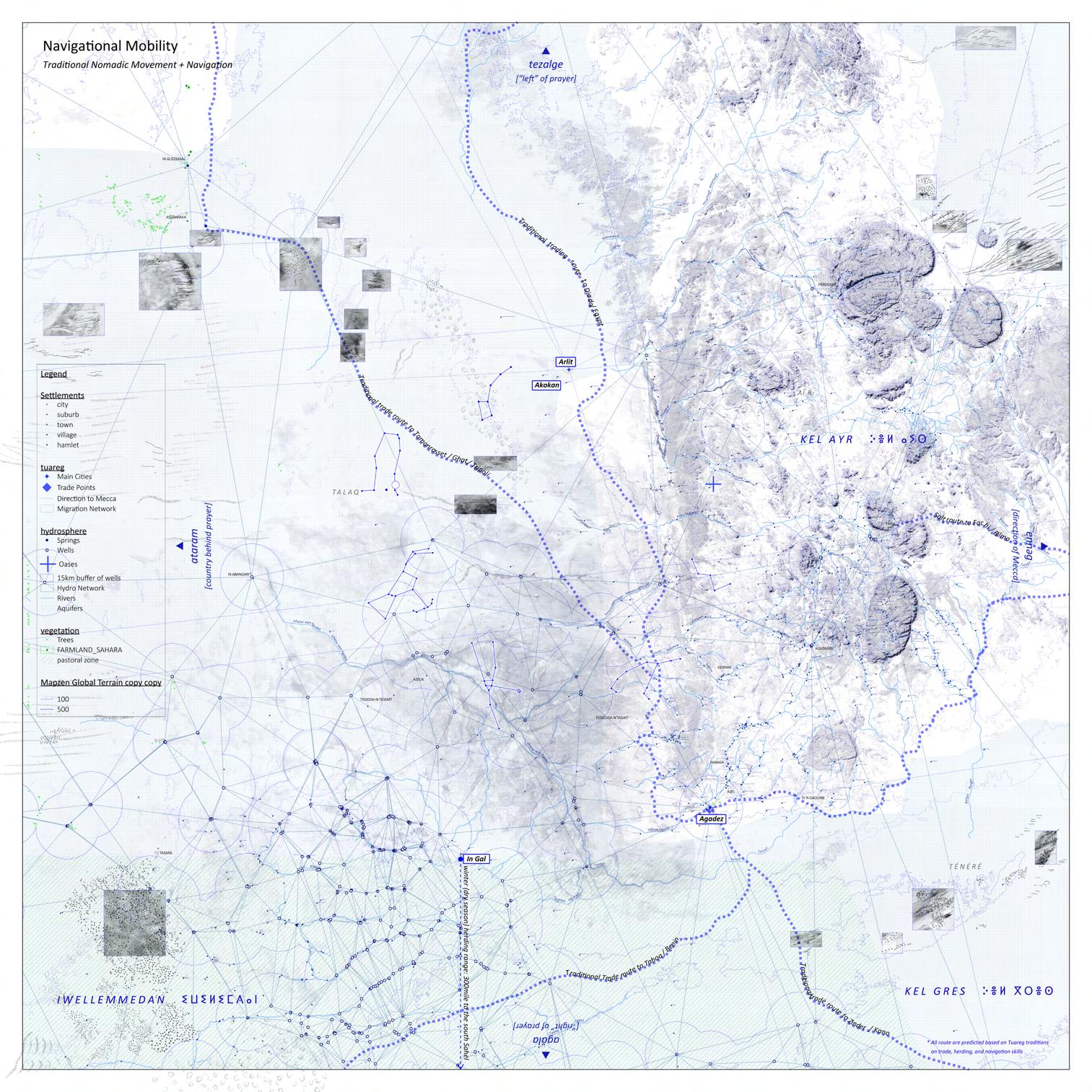

1-1

One of the most enduring internal trade routes of the Tuareg is the salt caravan route that begins in Timia, a semi-permanent nomadic settlement in the Aïr Mountains. Unlike purely pastoral encampments, Timia supports small-scale agriculture and gardening, with families cultivating citrus trees, date palms, and other crops adapted to the mountainous microclimate. Each autumn, following the harvest, caravans set off from Timia carrying grapefruits, lemons, and other valuable goods—renowned for their high barter value—destined for the oases of Fachi and Bilma. The journey spans six months round-trip, traversing the Ténéré desert with 20–30 camels laden with products. Upon reaching Bilma, these goods are exchanged for slabs of salt, a historically vital and symbolic substance in Saharan economies.

2-2

Agadez has long served as a major node of mobility and exchange, connecting various transSaharan trade routes—from the Sahel to the Mediterranean, Egypt to the Atlantic coast of West Africa. These routes, older than colonial borders, carried not only goods, but also cosmologies, rituals, and alliances.

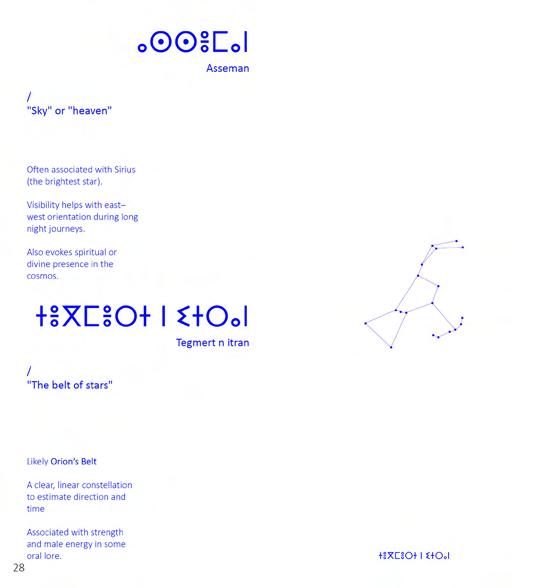

Tuareg travelers navigate the desert using a sophisticated, non-instrumental knowledge system rooted in celestial observation, dune morphology, vegetation patterns, and ancestral landmarks. Each caravan includes an elder guide who walks the route entirely on foot, embodying a lineage of orally transmitted geographical intelligence. This embodied practice, passed down across generations, sustains not just economic life, but also the epistemic sovereignty of nomadic communities.

3

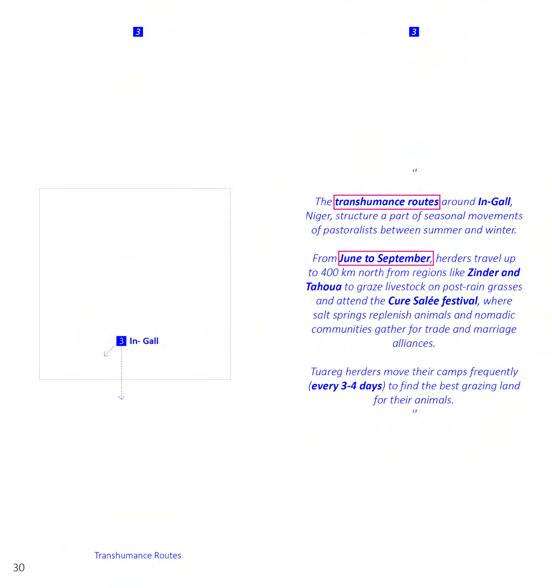

Except caravan movement, pastoral practice throughout the year contributes to the mobile economy as well. The transhumance routes around In-Gall, Niger, structure seasonal movements of pastoralists between summer and winter. From June to September, herders travel up to 400 km north from regions like Zinder and Tahoua to graze livestock on post-rain grasses and attend the Cure Salée festival, where salt springs replenish animals and nomadic communities gather for trade and marriage alliances. After the festival, herds migrate south—goats and sheep first, followed by cattle—staying near wells and greener pastures. Camels often remain in the region. These movements sustain herd health and reflect a cultural system built on generations of environmental knowledge rather than formal maps.

[The enduring internal trade routes and pastoral movements of the Tuareg—such as the salt caravans from Timia to Bilma, the historic trans-Saharan exchanges centered in Agadez, and the seasonal transhumance around In-Gall—are more than economic activities. They embody centuries of environmental knowledge, social relations, and cultural sovereignty intimately tied to the land and skies.

Today, however, these vital practices face existential threats from the imposition of radioactive legacies left by uranium extraction and militarized airspace control. The establishment of foreign military bases equipped with drone surveillance over traditional caravan routes and grazing lands transforms these spaces into zones of exclusion and danger. Restricted airspace and ground operations disrupt the free movement of nomads, fragmenting the mobility that underpins their economy and cultural identity.

Such military and environmental encroachments constitute structural violence and environmental injustice, criminalizing traditional livelihoods under the guise of security and counterterrorism. They sever the flow of goods, knowledge, and people across these ancestral networks, erasing the epistemic and economic sovereignty of the Tuareg while invisibly rendering their bodies and lands as ‘red zones’—excluded, surveilled, and endangered.]

and our old donkeys or camels, but I would also add the knowledge of our country. Oh! At that time, if I had had a new Toyota and held its reins, I would have driven it between Ghat, Agadez, Tamanrasset, and Djanet, and I would have made it gallop connecting the desert and the tents.

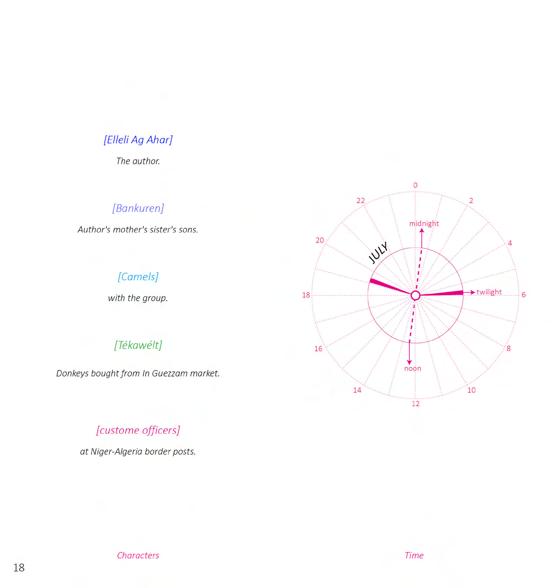

We were in this tangle of escapes and pursuits with the customs officers. Our old worn-out donkey, we ended up calling her Tékawélt because she was as black as the days of our lives. When we had to cross the In Gezzam post to buy cans of olive oil, we returned at sunset. We also bought sugar in a few shops of settled Tuaregs settled in In Guezzam. Once our donkey was loaded, we left the small border town to entrust ourselves to the desert, to the sand mountain and the pebbles that separate the In Guezzam post from that of Assamaka. Kakatcha kakatcha, she walked Tékawélt, dragging her hooves while leaning her head with her load, from time to time she would kick back and shake her head, finally putting it between her knees. Ouch, we hit her, but no, Tékawélt had sworn she would not move an inch. Behind us, we saw the headlights of the Toyotas of the Arab customs officers from Algeria announcing rifles, handcuffs, prison, and fines, punishments they gave to those who violated their border and stole their food, their sugar, their oil, and their semolina... My cousin struck Tékawélt; she stretched, sighed, and curled up like a paralyzed beetle. No spur or whip, nor push would have made Tékawélt move in her stubbornness. She was starving and, in the desert, there was no pasture. But she had also been taught, Tékawélt, the rewards! She refused to leave the rocky plateau overlooking the south of In Guezzam. As long as she didn't get her bakchich, she wouldn't move us from here, us and our luggage. I felt discouraged and then thought: "if I had a white mehari as fast as lightning or a new Toyota drinking gasoline and not diesel"... I stared at my cousin, my gaze hitting his grimace. We looked at each other, frustrated. "What else to do but give her the consolation that makes her move a step every time she stops?" said my cousin, tearing off cardboard, Algerian newspapers, and other papers from the Algerian army from his back. With a grimacing smile, he added: "cardboard or soft paper?". — Hurry up, the Toyotas are heading towards us. Give her her El-Moujahid which is easy to swallow, but save her rations because we still have a long way to extort from her until Assamaka in places where our eyelashes won't brush against a stem or a leaf to appease her refusal of rock.

Holding a handful of greasy and crumpled El-Moujahid, my cousin ran ahead of Tékawélt, far from her snout. He cracked the newspaper and waved it, then Tékawélt came out of her stupor, moved her ears, opened her nostrils, and with her eyes closed, in a staggering gallop under the load, she went straight towards my cousin. Now it was my turn. Stick raised in the air, I ran behind Tékawélt, while my cousin ran backward in front of her following our direction, continuing to crack the newspaper to attract her. And suddenly, Tékawélt, to the rhythm of the oil sloshing in the cans, grabbed her bite by snatching it from the child's hand and gulped it down in one go. Again, she lowered her ears, dug her hooves into the sand, and froze. My cousin, seeing the headlights of the enemy approaching us, drew a new handful of cardboard and greasy papers, waving them in the wind. Tékawélt woke up again and I held the whip, ordering her: "hed!". And the race of Tékawélt chasing the cardboard and the papers started again, with me chasing Tékawélt and being chased by the Toyotas. We raced down a landslide above In Guezzam towards the sandy desert. Far behind us, we saw the headlights of the Arabs struggling with the dunes that Tékawélt had just crossed thanks to the cardboard and greasy papers of El- Moujahid. Thus we did, my cousin and I, the son of my mother's younger sister.

3

Every time we worked for three days, we offered to Tékawélt a rest in a mountain shelter southwest of In Guezzam. There, we found pastures that were always papers, cardboard, and Adam's dung that the wind brought back from In Guezzam. Today, it had been months since one of us with these dirty papers was chased by Tékawélt and the other was chasing her with his stick, following the hairless behind of the old donkey. One twilight, the post of In Guezzam was eclipsed in a whirlwind of sand sent by the east wind that was moving the entire desert. The inhabitants of the city, Tuaregs and Arabs who held the post, were all huddled in their shelters, door closed. The wind stirred the cans, the papers, and the chif fons. Tékawélt was salivating, her eyes fixed on her menu that the wind was shredding in front of her. We were heading towards the post where even the devil would not have walked in this weather and we intended to quickly gather our bundles and our cans of oil as we had come, without seeing or hearing any customs officer because on this day the wind itself was on our side. At the city gate, in front of a solid iron house, we found along stake and tied Tékawélt to prevent her from venturing behind the sandstorm that was swirling with her food. Once Tékawélt was secured to this large iron stake with, in front of her, a pile of El-Moujahid and cartons of Gloria and Lakhda milk packaging held down by stones, we tightened our belts, rolled up our pants to our knees, rubbed our hands, took our ropes over our shoulders and went back into the city. Shack after shack, we roamed the houses of the Taïtoq Tuaregs, the Kel Ghela and their sedentary vassals in In Guezzam, where one could take a can of diverted oil, a small bag of powdered sugar or semolina. Handful by handful we gathered our goods. We filled our motor oil cans with water and stocked up. In our bags, we put semolina and salt to make our bread that we would share with Tékawélt in the evening. Finally, we brought our luggage back to where our mare was waiting for us, under her large iron stake smoothed by hands and grains of sand that slapped her every day above In Guezzam. Then, blowing with half of our load, suddenly, like a slap, our two gazes filled with the tears that the sand and wind made flow from our eyes, collided with Tékawélt's exposed canines that were tearing from the stake a piece of green fabric marked with spots red in the middle. With a dried heart, we looked at each other again and, at the same time, our gazes turned towards the cement and iron buildings, with their stake to which Tékawélt's canines were still hanging. "It's the customs!" shouted my cousin and suddenly I shut his mouth: "be quiet, child, if those are the customs buildings, we are done for! Let's run, flee, quickly!".

Before finishing these words, I brought my gaze back to the jaw of Tékawélt who had already torn and shredded the Algerian flag with its crescent and red star. Quickly we threw our bundles and cans onto the back of the shedonkey, some tied, others simply placed. Before I finished picking up the luggage that remained on the ground, my cousin had untied the rope from the iron stake that was used to hoist the Algerian customs flag and with an unmatched speed we returned to the desert. In the blink of an eye we descended the mountain south of In Guezzam. This time, the march was easy because we had a profusion of papers and cartons but also the storm was pushing Tékawélt who was still dragging her feet while chewing on her flag scraps. We were both joyful and sad. Joyful that we, Tuareg children aged not even sixteen years old, had looted the flag of one of the most powerful Arab armies. Worried because we knew that the customs officers would soon be on our trail. But we were sure that the Arabs of the Tell, on this night of sand wind, would not dare to leave their shelter to face the desert, even if they had some Tuaregs as guides. In short, even though we were sad, that night, our companion, the sand wind, was on our side. My cousin climbed a peak andlooked behind us to see if a beacon was pursuing us. But nothing other than the red storm, which was tearing through the night, came to meet his gaze. Ayiwa!

That night, since Tékawélt had pulled this trick on us, we had left. to change our route. Even if, before lifting our feet, the wind was already erasing every step left behind, we had to obscure our trail. "Let's take the desert to the west of In Guezzam where no one would think that a soul pushing a donkey would dare to venture." As soon as we slipped south of the mountain of In Guezzam, we headed southwest. Every time Tékawélt dragged her feet, we gave her food. As the night progressed, she was hungry and the slightest sound of cardboard pulled her from her stupor. Once we had moved away from the city lights, we realized that one of our supply bags was missing. We were advancing in a desert where we had never walked, and even the few stars that had just twinkled behind us had finished disappearing. Only a yellow veil of sandstorm was tearing and sweeping the desert. Neither in front nor behind, not the slightest landmark to orient ourselves. The only thing guiding us was the will to flee and distance ourselves from the place where we were suspected. That night we had neither eaten nor drunk, we walked and the wind pushed us as we sank deeper into the desert of the Dog Canines (Tirtnas n idi). It was a succession of rocky

[brochure]

[brochure]

1–2

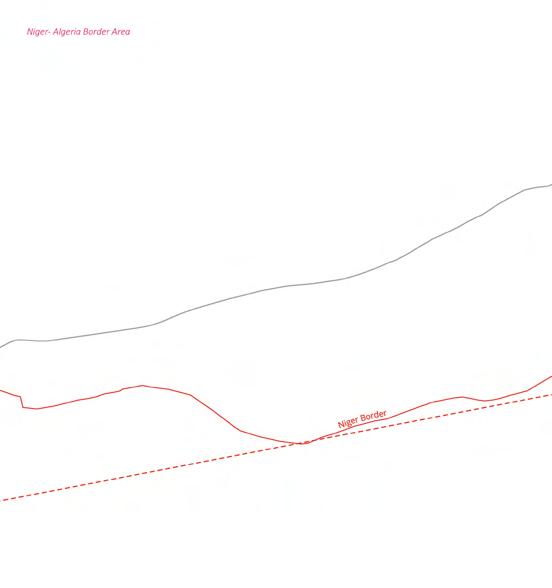

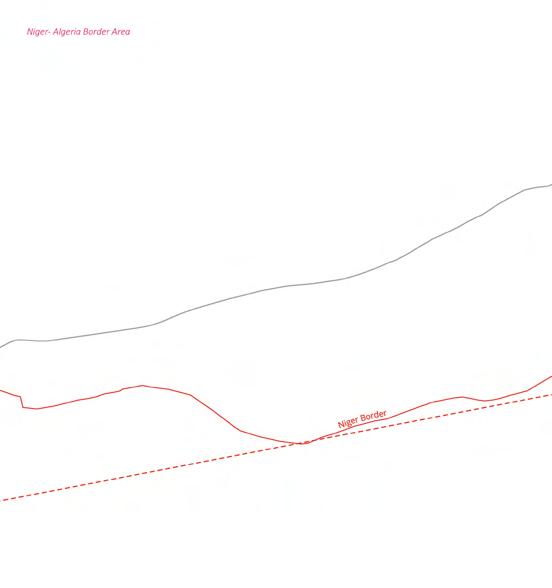

Departing from camp in the Aïr Mountains, they begin their journey northward toward the Niger–Algeria border, heading for the twin towns of Assamaka and In Guezzam.

Along the way, they are intercepted and robbed by customs officers—an encounter that exposes the uneven weight of borders and authority in the Sahara.

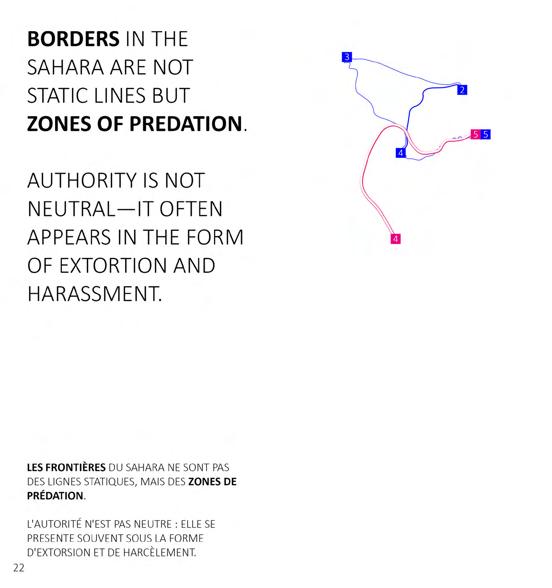

[Insert argument: e.g., This moment foregrounds how borders in the Sahara are not static lines but zones of predation. Authority is not neutral—it often appears in the form of extortion and harassment. Here, the border is a lived experience of dispossession rather than legal delineation, disrupting global assumptions about state protection and sovereignty.]

2–3–4–5

In In Guezzam, they purchase a donkey in the market, preparing to gather goods for trade in Niger. They settle beneath a rocky cliff on the town’s edge, hoping for rest and invisibility. But soldiers notice them. Their stillness is mistaken for suspicion. They flee again.

[Insert argument: e.g., The constant surveillance of nomadic bodies reconfigures rest as risk, and presence as trespass.]

6–7–8–9

Hardship deepens. The land offers nothing for their animals; the donkey and camel nibble at garbage, newspaper, and dust—pasture formed from abandonment.

Just as they adapt, a military Toyota emerges. A chase begins, only to be undone by the desert’s scale—both pursuers and pursued swallowed by disorientation.

[Insert argument: e.g., This sequence shows how both environmental degradation and militarization limit nomadic practices. Wind-scattered trash becomes unintended pasture—a stark image of ecological collapse. Meanwhile, even the soldiers are disoriented in the terrain, revealing the limits of military power in the vastness of the Sahara. The desert resists domination, offering temporary refuge through its opacity.]

10–11

They return to Assamaka, crossing back into Niger. There, they reunite with Ishumar companions. Around firelight, songs echo, stories stretch into the night, and dust becomes dancefloor.

[Insert argument: e.g., These moments of gathering reclaim space from the state, turning survival into ceremony, and exile into kinship.]

11–12

At dawn, the journey resumes. They cross the shifting borders once again, carrying goods and memory. What they trade is not only material—it is knowledge, endurance, and a refusal to be fixed by lines on a map.

[Insert argument: e.g., This act of mobile exchange defies imposed immobility and asserts nomadic sovereignty over ancestral trade routes.]

[drawing resources]

Niger: Ghosts of Uranium ARTE.tv Documentary.

In Gall - Ighazer (Niger), Les Kel Ferwan. 24 décembre 2017. Modified on 21 avril 2025. https://www.ingall-niger.org/hier/les-communautes/ les-kel-ferwan.

Sahara FM.

Aïr-Info Agadez.

Dominique Casajus, Islam et noblesse chez les Touaregs. 1990. p.22.

Hawad, Buveurs de braises 1995, p.9.

Studio Kalango

Flightradar24 aviation database and reports.

Worse Than Chernobyl: Folloig Europe’s Nuclear Pollution to Schools in Niger | Full Documentary, Java Discover.

Esri satellite image remote sensing.

Base 201- The Secret US Base In Niger That You Should Know About. | Today’d Africa.

Hélène Claudot-Hawad Éperonner le monde (2001). Voyager d’un point de vue nomade (2002).

Ag Ahar Elleli. The initiation of an ashamur.

[cassette resources]

Etran de L'Aïr Agadez

Tinariwen

The Radio Tisdas Sessions Kel Tinariwen

Sahara FM

Radio Kalango

Ag Aïr

Documentaire: Amaneï, touareg entre dunes et montagnes Etran de L'Aïr

@SahelSounds Fatou Seidi Ghali (Les Filles de Illighadad) - Telilit

@rikedenimes

LES SUDS À ARLES : Tinariwen (Théâtre Antique 2023)

@OurWorld

The Changing Nomadic Life of the Berber Tribe: Tuareg | Our World

[other documentary review]

@Icietailleursvoyages

Enfants des déserts - Ataer, enfant des sables.

@aljazeeraenglish

Orphans of the Sahara | Return (Episode 1)

Orphans of the Sahara | Rebellion (Episode 2) Orphans of the Sahara | Exile (Episode 3)

Go Wild Tuareg: The Warriors of the Dunes

[litrature review]

Hélène Claudot-Hawad

A Nomadic Fight against Immobility: the Tuareg in the Modern State. D. Chatty. Nomadic Societies in The Middle East and North Africa: Entering the 21st Century, Brill, pp. 654-681, 2006.

Touaregs Voix solitaires sous l'horizon confisqué.

Touaregs. Exil et résistance.

James McDougall and Judith Scheele

SAHARAN FRONTIERS: Space and Mobility in Northwest Africa

Gabriella F. Scelta

The Calligraphy and Architecture of the Geometric Contect of Islam.

Thomas J. Barfield The Nomandic Alternatives.

John Cages Visible Music II

Donna Haraway

Staying with the Trouble: Making Kin in the Cathulucene

A Cyborg Manifesto: Science, Technology, and Socialist-Feminism in the Late Twentieth Century (1985)

Haraway asserts that humans are not separate from the web of life but are integral to a vast, interconnected network that includes animals, plants, ecosystems, and the earth itself.

Susan Schuppli

Material Witness: Media, Forensics, Evidence

Susan’s book introduces a new operative concept: material witness, exploring the material world and its affordances with the aesthetic, the juridical, and the political.

Astrida Gundega Neimanis Bodies of Water

In this book, Astrida introduce hydrofeminism and discuss the material connections between water and bodies. It enphasizes how water cycles through all living beings and ecosystems, dissolving rigid distinctions and fostering a sense of mutual dependency and responsibility.

Ifor Duncan + Stefanos Levidis Weaponizing a River

Ifor’s writing is a compelling examination of how bodies of water, particularly rivers, are used as tools of violence, exploitation, and control. Natural uranium ore, once extracted from the earth, has the potential to not only damage the environment but also be utilized as a geopolitical weapon.

Vhahangwele Masindi + Spyros Foteinis

Groundwater contamination in sub-Saharan Africa: Implications for groundwater protection in developing countries

Robert P. Ambroggi Water under the Sahara

Gwendolyn K. Kirschner + Ting Ting Xiao + Ikram Bililou

Rooting in the Desert: A Developmental Overview on Desert Plants

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

A big thank you to my tutors, Kamil Dalkir and Veronika Varga, for their continuous support and for helping shape my thinking throughout the academic year.

I am also grateful to the RS4 tutors, Christina Leigh Geros and Aslı Uludağ, for their additional guidance and encouragement.

Special thanks to Godofredo Pereira and all the invited guests for their critical feedback.

I deeply appreciate the conversations I've had with Tuareg individuals (including those who preferred to remain anonymous), which have enriched this work. In particular, I thank Maïa Tellit Hawad for her mentorship and Mossa Kidan for his invaluable help with sonic history.

Also, thanks to the music work done by Tinariwen and Etran De L'Aïr, and poems wrote by Mahmoudan Hawad and translate by Hélène Claudot-Hawad.

Finally, thank you to all my peers and friends for your constant support and solidarity.

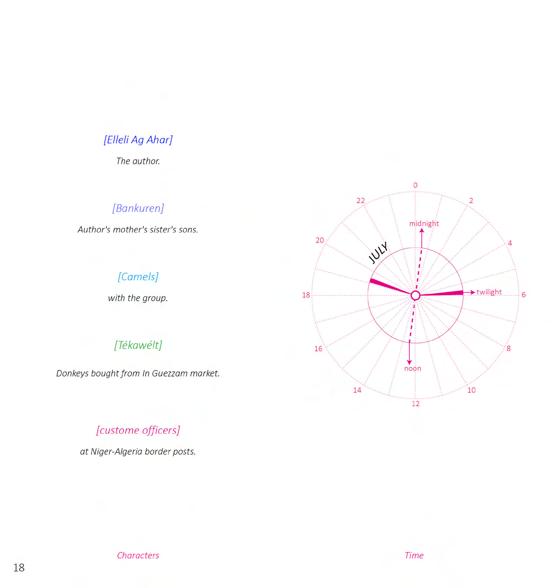

[drawing- legal immobility]

This story was collected in January 1990 and translated into French by Hawad and Hélène Claudot, and access by Ava Xia in 2025.

Thanks to Kamil Dalkir for the suggestion to use personal stories as powerful evidence in crafting counter-cartographies, as the first practice in this project.

[drawing- navigational immobility]

Inspired by chat with Maïa Tellit Hawad about experiencing challenges going back home, both for visiting and research as either a diaspora or scholar.

Inspired by Hélène Claudot-Hawad, who is a French anthropologist and professional Researcher (Directrice de Recherche) at the National Centre for Scientific Research (CNRS).

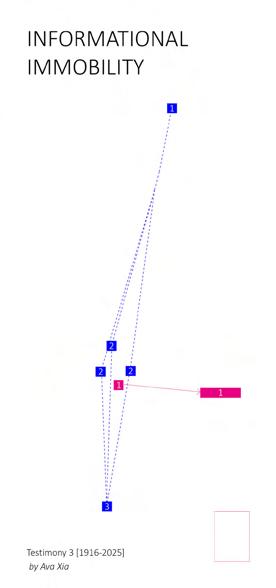

[drawing- informational immobility]

Inspired by a conversation with Assaleck Ag Tita during a field trip in Paris, where oral tradition and encounter emerged as central modes of knowledge and information exchange.

Inspired by semi-structured conversation with Ibrahim Diallo, a half-Tuareg and half-Fulani, and funder of Sahara FM and Air Info, about lack of info accessibility in rural Niger.

Supported by multiple conversations with Mossa, a talented and passionate Tuareg musician.

Inspiered by stories of exiled Tuareg musicians and bands, for example, Bombino and Tinariwen

Thanks to sharings about mines and radio listening from a anonymous Tuared miner in Akokan

Radioactivity. Radio Waves. Resistance. Royal College of Art

Ava Xia

10045091@network.rca.ac.uk avaxia.25@gmail.com

+44(0)7879953762

@ava_la_design