on the agenda

contesting identity paintings from Lake Sentani Barkcloth paintings from the Museum’s collections highlight cultural tensions in West Papua, says Yvonne Carrillo-Huffman.

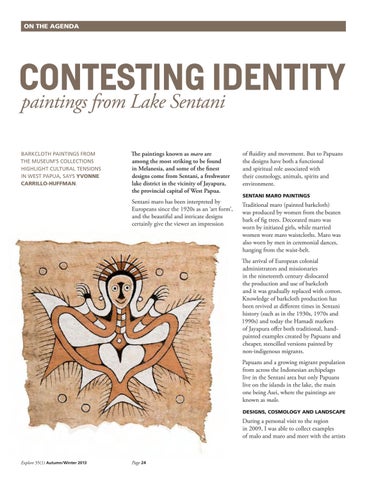

The paintings known as maro are among the most striking to be found in Melanesia, and some of the finest designs come from Sentani, a freshwater lake district in the vicinity of Jayapura, the provincial capital of West Papua. Sentani maro has been interpreted by Europeans since the 1920s as an ‘art form’, and the beautiful and intricate designs certainly give the viewer an impression

of fluidity and movement. But to Papuans the designs have both a functional and spiritual role associated with their cosmology, animals, spirits and environment. Sentani maro paintings

Traditional maro (painted barkcloth) was produced by women from the beaten bark of fig trees. Decorated maro was worn by initiated girls, while married women wore maro waistcloths. Maro was also worn by men in ceremonial dances, hanging from the waist-belt. The arrival of European colonial administrators and missionaries in the nineteenth century dislocated the production and use of barkcloth and it was gradually replaced with cotton. Knowledge of barkcloth production has been revived at different times in Sentani history (such as in the 1930s, 1970s and 1990s) and today the Hamadi markets of Jayapura offer both traditional, handpainted examples created by Papuans and cheaper, stencilled versions painted by non-indigenous migrants. Papuans and a growing migrant population from across the Indonesian archipelago live in the Sentani area but only Papuans live on the islands in the lake, the main one being Asei, where the paintings are known as malo. Designs, cosmology and landscape

During a personal visit to the region in 2009, I was able to collect examples of malo and maro and meet with the artists

Explore 35(1) Autumn/Winter 2013

Page 24